1. Introduction

Diesel engines continue to be indispensable in industrial and transportation systems due to their superior thermal efficiency, high torque output, and excellent fuel economy. These qualities make them particularly wellsuited for heavyduty applications such as freight transport, marine propulsion, and stationary power generation [

1]. Nevertheless, conventional diesel fuels derived from petroleum resources have complex hydrocarbon compositions. These fuels release significant quantities of nitrogen oxides (NO

x) and particulate matter (PM) during combustion. These pollutants pose severe risks to both public health and ecological systems [

2]. NO

x contributes to the formation of photochemical smog and acid deposition, while PM triggers respiratory diseases and degrades air quality. Hence, mitigating these emissions is a critical challenge for sustainable energy development. Furthermore, diesel engines operating at high altitudes encounter exacerbated combustion inefficiencies due to reduced atmospheric oxygen levels. This leads to incomplete fuel oxidation, ignition failures, accelerated component wear, and overall performance deterioration [

3].

Oxygenated fuels have been viewed as promising alternatives or blending components for diesel. Their inherent oxygen content enhances combustion completeness by supplying intramolecular oxygen. This capability effectively suppresses the formation of carbon monoxide (CO), unburned hydrocarbons (UHCs), and soot [

4]. Among oxygenated fuels, polymethoxy dibutyl ether (BTPOM

n)—with a molecular structure of C

4H

9O(CH

2O)

nC

4H

9, where

n denotes the polymerization degree of methoxy groups—exhibits superior fuel properties due to its complete miscibility with hydrocarbons, high oxygen mass fraction, and favorable handling properties. Its advantages include a higher cetane number and an elevated net calorific value [

5]. Additionally, BTPOM

n has a density that closely matches that of commercial diesel fuels. This enhances its compatibility as a diesel blending component and solidifies its status as a promising oxygenated fuel candidate [

6]. However, the synthesis of BTPOM

n relies on a complex multi-step reaction network, encompassing processes such as trioxane depolymerization, formaldehyde oligomerization, and etherification with

n-butanol. The yield of BTPOM

n is highly sensitive to operating conditions, making accurate yield prediction critical for optimizing reaction parameters and reducing experimental costs. Despite this importance, yield prediction remains challenging due to the nonlinearity and coupling of process variables.

Traditional approaches to yield prediction primarily depend on mechanistic models, such as lumped kinetic models and molecular dynamics models [

7]. These models often require an increased number of lumps in order to improve prediction accuracy. This would lead to more complex reaction networks, heavier computational loads, and slower operation speeds. Furthermore, mechanistic models are constrained by the current state of knowledge regarding reaction mechanisms, which hinders their ability to characterize how nonlinear relationships between system features influence yield variations. In contrast, datadriven models based on machine learning can establish relationships between input variables and output variables using historical data. It does not require explicit mechanistic interpretation. This advantage makes datadriven models more flexible for complex chemical processes, especially with the growing availability of real-time data.

In the field of petroleum catalysis, datadriven models have been widely applied for yield prediction. Dash et al. developed a hybrid neural model employing an artificial neural network model in conjunction with genetic algorithms for the prediction of water levels, and the results indicated that the model could effectively simulate waterlevel dynamics [

8]. Sharifi et al. used a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to predict hydrocracking product yield [

9], and Heilemann et al. adopted Lasso regression for crop yield prediction [

10]. Ren et al. further proposed an oil production prediction model leveraging Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) [

11]. Nevertheless, while neural network-based methods are plagued by drawbacks such as inadequate interpretability and prolonged training cycles, AdaBoost is limited by its strong susceptibility to outliers and intrinsic sequential learning paradigm, which renders parallel data processing infeasible [

12].

CatBoost, an advanced variant of the gradient boosting algorithm, addresses these limitations by enabling automatic processing of categorical features and employing an ordered boosting mechanism. This design reduces overfitting and enhances the stability of the ensemble classifier [

13,

14,

15]. However, the performance of CatBoost is highly dependent on the selection of globally optimal hyperparameters, including learning rate, tree depth, and number of iterations. Manual tuning or trial-and-error methods are not only labor-intensive but also likely to miss optimal parameter combinations. This becomes more pronounced under small sample conditions, where model generalization is already limited [

16]. The genetic algorithm (GA), an evolutionary algorithm inspired by Darwin’s theory of natural selection, performs well in global optimization in complex spaces. It does not require the target function to be continuous or differentiable, making it wellsuited for tuning the hyperparameters of machine learning models [

17].

Current research on BTPOMn synthesis has focused primarily on exploring reaction mechanisms and optimizing experimental conditions. Little attention has been paid to data-driven yield prediction. This gap is particularly evident under small sample conditions, which are common in early-stage laboratory research. This study proposes a GACatBoost hybrid model for BTPOMn yield prediction. A datadriven model containing four key operating variables—reactant ratio, reaction temperature, reaction time, and catalyst concentration—was developed to predict the yields of BTPOM1 and total BTPOM1–8. The hyperparameters of CatBoost using GA were optimized to enhance the model’s accuracy and generalization capabilities under small sample conditions. The performance of the GACatBoost model was then compared with that of the GAAdaBoost, SVR, RF, and KNN algorithms. The key factors influencing BTPOMn yields were identified through feature importance analysis, providing practical guidance for optimizing experimental processes.

3. Experiment

3.1. Chemical Reactions

The catalytic synthesis of BTPOMn from n-butanol and trioxane over NKC-9 molecular sieve also proceeds through a complex multi-step reaction network. Trioxane acts as a formaldehyde precursor, undergoing depolymerization to generate reactive oxymethylene intermediates. These key species drive subsequent BTPOMn formation. This study systematically elucidates the reaction mechanism and behavior governing BTPOMn synthesis. These reactions dictate the overall pathway of BTPOMn formation, and understanding their interplay is critical for optimizing yield.

Chromatographic monitoring was employed to track the time-dependent evolution of BTPOM

n speciation following catalyst activation, providing direct insights into reaction progression. Oligomer populations emerged sequentially in correlation with reaction time. This reflected the stepwise nature of chain growth. In contrast, higher polymerization-degree homologues exhibited a monotonic concentration decay inversely proportional to their chain length, likely due to increased steric hindrance. It slows further etherification and promotes chain termination. The kinetic model developed herein formalizes this consecutive chain propagation mechanism, which is governed by a series of elementary reactions. Equations (1)–(3) indicate the reactions in details and describe the stepwise addition of oxymethylene units to

n-butanol-derived intermediates [

18,

19]. The kinetic model employed a pseudo-homogeneous phase approximation, presuming uniform dispersion of catalyst active sites in the liquid phase with unimpeded reactant accessibility. As for BTPOM

n chain propagation kinetics, the forward and reverse rate constants denoted as k

3 and k

−3 were assumed independent of polymer chain length due to structural and mechanistic congruence across oligomerization steps.

The inherent water content in the reaction system introduced a competing catalytic pathway, wherein formaldehyde underwent condensation to form polyoxymethylene glycols (MG) as secondary products, as shown in Equation (4). This side reaction consumes reactive formaldehyde intermediates that would otherwise participate in BTPOM

n synthesis, thereby reducing target product yield. Controlling water content or mitigating MG formation thus represents a potential strategy for improving BTPOM

n production efficiency.

In parallel,

n-butanol underwent nucleophilic addition to formaldehyde, establishing the dominant pathway for generating polyoxymethylene hemiformal (HD

n). This is a critical intermediate in BTPOM

n synthesis. The governing reaction sequence for HD

n generation is detailed in Equations (5) and (6), which describe the successive addition of formaldehyde to

n-butanol to form HD

1 and its subsequent conversion to HD

2.

3.2. Materials

High-purity n-butanol (GC-grade, ≥98 mass%) and trioxane (GC-grade, ≥99 mass%) were procured from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The GC-grade specification ensures minimal impurities, which is critical for avoiding unintended side reactions and ensuring accurate quantification of BTPOMn products via gas chromatography. The macroporous cation-exchange resin catalyst NKC-9 was commercially sourced from Nanjing Guojin New Materials Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). The macroporous structure provides a high specific surface area for catalytic active sites. Its cation-exchange properties facilitate the protonation of reactants. This is an essential step for initiating trioxane depolymerization and formaldehyde oligomerization.

Deionized water was generated in-house using a Millipore Milli-Q water purification system (IQ 7000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), ensuring ultra-low ion content to prevent interference with the catalytic reaction. Reference standards for BTPOM1 (C4H9-O-CH2O-C4H9) and BTPOM2 (C4H9-O-(CH2O)2-C4H9) were provided by the Systems Engineering Institute at the Academy of Military Sciences (Beijing, China). These standards served as critical calibrants for the quantitative chromatographic analysis of BTPOMn oligomers. This enables accurate determination of individual and total BTPOMn yields by establishing calibration curves for peak area-to-concentration conversion.

3.3. Apparatus and Experimental Procedure

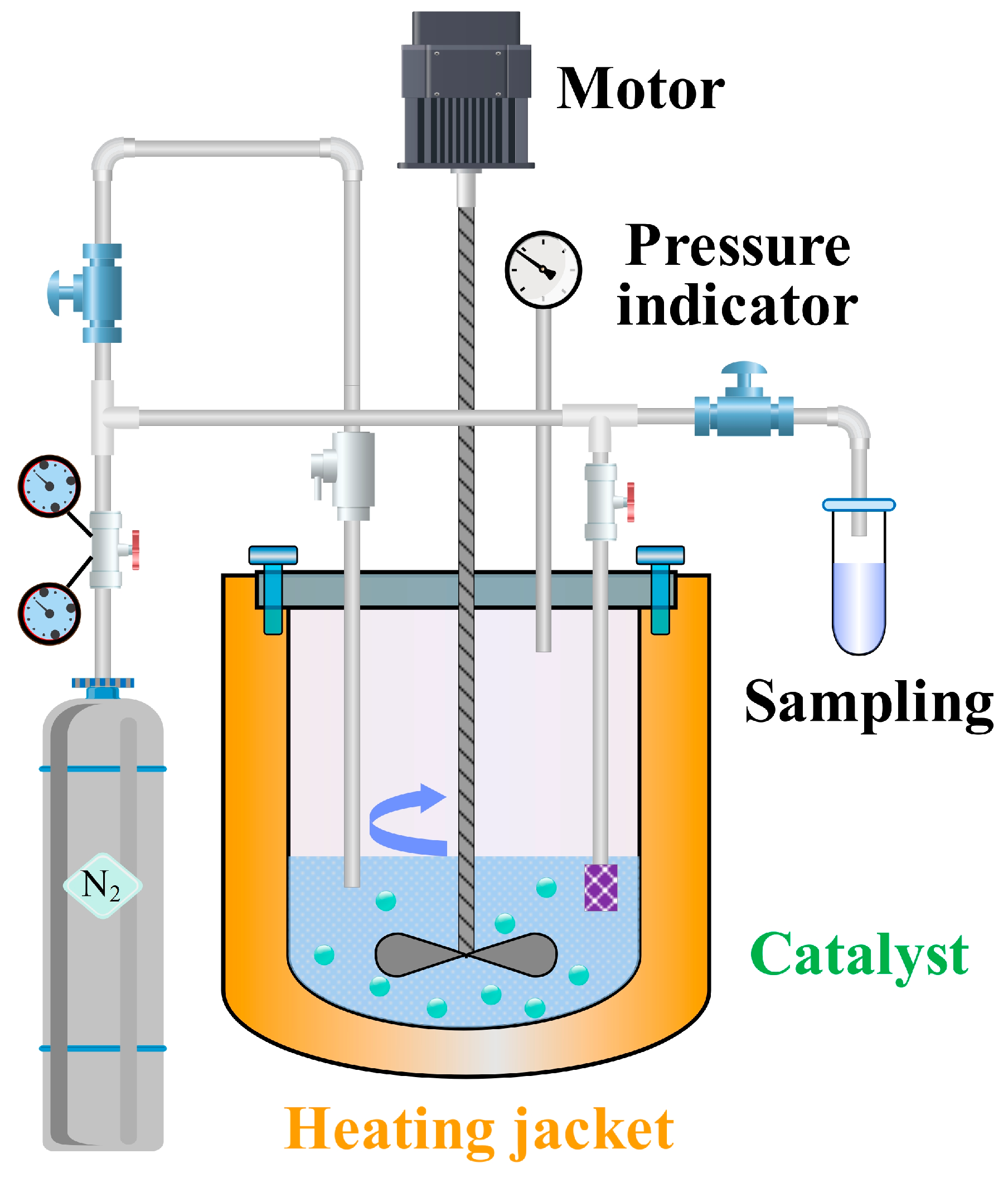

The apparatus for BTPOMn synthesis was a 500 mL titanium alloy high-pressure autoclave (Model YZMR-4100D, Weihai Yantai Chemical Machinery Co., Ltd., Weihai, China). Titanium alloy was selected for the autoclave material due to its excellent corrosion resistance and its high thermal conductivity, which ensures uniform heat distribution during reaction. The autoclave was equipped with a dual-impeller mechanical stirrer featuring a 45° blade tilt angle and an impeller-to-reactor diameter ratio of 1:3. This stirrer design optimizes mixing efficiency, ensuring homogeneous contact between reactants and catalyst particles. The 45° blade tilt promotes axial and radial flow, preventing catalyst sedimentation and minimizing concentration gradients within the reaction mixture.

A nitrogen pressurization system equipped with a digital pressure regulator was used to create an inert atmosphere, preventing oxidative degradation of reactants or intermediates. A temperature control system incorporating a Pt100 resistance temperature detector (WZPT-035, Jiangsu Ming Cable Technology Co., Ltd., Taizhou, China) and a proportional-integral-derivative algorithm maintained temperature uniformity within ±0.5 °C. Precise temperature control is essential for BTPOMn synthesis, as reaction rates and catalyst activity are highly temperature-dependent.

A pressure stabilization unit consisting of a piezoelectric transducer and a fast-response solenoid valve limited pressure fluctuation to ±0.02 MPa. Stable pressure suppresses vaporization of low-boiling components, ensuring consistent reactant concentrations throughout the reaction. A sampling system featuring a 5 μm sintered metal filter retained catalyst particles during sampling, preventing contamination of collected samples. Nitrogen backfilling was employed post-sampling to maintain isobaric conditions, avoiding pressure-driven changes in reaction kinetics. A 2 kW heating jacket with a heating rate of 5 °C/min enabled controlled temperature ramps, reducing thermal shock to the reaction mixture and ensuring reproducible reaction initiation.

Figure 6 presents the schematic of the experimental setup, illustrating the integration of these subsystems with the autoclave to enable precise control and monitoring of the BTPOM

n synthesis process.

3.4. Experimental Procedure

The experimental procedure for BTPOMn synthesis was designed to ensure reproducibility and precise control of the four key input variables, including reactant ratio, reaction temperature, reaction time, and catalyst concentration. The n-butanol and formaldehyde were added to the autoclave at a molar ratio ranging from 1:2 to 2:1. The variable was selected to explore the impact of formaldehyde availability on BTPOMn chain length and yield. The stirrer was activated at 300 r/min to ensure homogeneous mixing of reactants, preventing localized concentration gradients that could skew reaction kinetics.

NKC-9 catalyst was added to the mixture at a concentration of 1 wt.% to 8 wt.%. The autoclave was hermetically sealed. The autoclave was then purged with high-purity nitrogen (99.99% purity) three times to remove residual oxygen. Oxygen would otherwise oxidize reactants or deactivate the catalyst and lead to reduced yield and inconsistent results. The autoclave was pressurized to 0.25 MPa with nitrogen to initiate the inert atmosphere following purging.

The heating jacket was activated to raise the reaction temperature from ambient to the target range, from 80 °C to 130 °C, at a constant rate of 5 °C/min. The stirrer speed was increased to 600 r/min to enhance mass transfer between reactants and catalyst once reaching the set temperature. This is critical for accelerating reaction rates while maintaining homogeneity. The pressure was simultaneously adjusted to 1.0–1.1 MPa to suppress vaporization of low-boiling components, ensuring that reactants remained in the liquid phase and available for reaction. Reaction time was recorded from this point, with a variable range of 1 h to 6 h to capture the full progression of BTPOMn formation and potential yield decline due to side reactions.

Samples of 5 mL were collected at 5 min intervals after the first hour and at 30 min intervals for the rest time using the autoclave’s sampling valve to track yield evolution over time. Collected samples were filtered through a 0.22 μm organic phase filter to remove any remaining catalyst fines, preventing interference with chromatographic analysis. Filtrates were then analyzed via gas chromatography (Model 7890A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a DB-WAX capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) and a flame ionization detector (FID)—a configuration optimized for separating and quantifying oxygenated organic compounds like BTPOMn. The GC operating conditions were carefully calibrated. Inlet temperature was set to 250 °C to ensure complete vaporization of samples, and detector temperature was set at 280 °C for maximum sensitivity. A column temperature program with an initial temperature of 60 °C held for 2 min, then ramped at 10 °C/min to 220 °C and held for 5 min was employed to achieve baseline separation of the BTPOM1 to BTPOM8. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min with a split ratio of 10:1, balancing sensitivity and peak resolution.

3.5. Yield Calculation

The yield of BTPOM

1 and the total yield of BTPOM

1–8 were calculated using the internal standard method, with n-hexadecane selected as the internal standard. This method was chosen for its robustness against variations in sample injection volume and chromatographic conditions, ensuring accurate and reproducible yield quantification. The calculation is expressed in Equation (7):

Here,

Yi represents the yield of either BTPOM

1 or BTPOM

1–8.

mi,prod denotes the actual mass of BTPOM

1 or BTPOM

1–8 in the product. It was determined via GC analysis by comparing the peak area of the target BTPOM

n species to that of the internal standard using pre-established calibration curves [

20].

mi,theo is the theoretical mass of BTPOM

1 or BTPOM

1–8. It was calculated based on the initial amount of trioxane. Trioxane is the sole source of formaldehyde; its initial mass dictates the maximum possible yield of BTPOM

n species. This theoretical mass calculation accounts for the stoichiometry of trioxane depolymerization and the subsequent etherification with

n-butanol, ensuring a direct link between reactant input and expected product output.

4. Methodology

A data-driven modeling framework was established to address the challenge of BTPOM1 and BTPOM1–8 yield prediction under small sample conditions with 88 experimental sets. This framework defines a mapping relationship between input features and output yields. The input feature vector involves reactant ratio, reaction temperature, reaction time, and catalyst concentration. The output consists of BTPOM1 yield and total BTPOM1–8 yield. The methodology focuses on integrating the CatBoost algorithm with the genetic algorithm (GA) for hyperparameter optimization to address the limitations of manual tuning and traditional models.

4.1. CatBoost Algorithm

CatBoost is an advanced variant of the Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithm, specifically designed to overcome the reliance on manual categorical feature encoding and high susceptibility to overfitting [

21]. Target encoding of categorical features and an ordered boosting mechanism were applied to enhance model stability and prediction accuracy for complex chemical process data.

(1) Target Encoding of Categorical Features.

CatBoost employs target encoding that maps categorical values to numerical representations using the target variable’s statistical properties for categorical features. The target encoding of category

cm is calculated via Equation (8) for a categorical feature C with distinct values {

c1,

c2,

…,

ck}:

Here, ∅(cm) is the encoded value of category cm. α is a smoothing coefficient that balances category-specific statistics from the sum of target values yj for samples in cm and the global mean of the target variable μ. This balance is critical for small sample conditions, as it prevents bias from categories with few samples. The term count (cm) represents the number of samples in category cm. One-hot encoding expands categorical features into high-dimensional binary vectors and risks overfitting with limited data. In contrast, target encoding reduces dimensionality while preserving the statistical relevance of categorical features, making it far more suitable for the small sample size here.

(2) Objective Function

The objective function of CatBoost in the

t-

th iteration incorporates a loss term and two regularization terms. They work together to minimize prediction error and suppress overfitting. It is defined in Equation (9):

In this equation, L(·) is the loss function. It was set to mean squared error (MSE) for regression tasks to penalize large prediction deviations. Ft−1(xi) is the predicted yield of sample xi using the first t − 1 decision trees, and ht(xi) is the output of the t-th decision tree for xi. λ is the regularization coefficient for leaf node values (vj). It smooths these values to prevent extreme predictions that contribute to overfitting. γ is the regularization coefficient for the number of leaf nodes (Nleaf) in the t-th tree. It penalizes excessive leaf nodes to control tree complexity and avoid overfitting to noise in small samples.

4.2. Genetic Algorithm (GA)

The genetic algorithm (GA) is an evolutionary optimization technique inspired by natural selection and genetic variation. It shines in global optimization for complex, non-differentiable solution spaces. It is ideal for tuning the hyperparameters of CatBoost, which lack a clear mathematical relationship to model performance [

22,

23,

24]. The workflow of GA consists of population initialization, fitness calculation, and three genetic operations, including selection, crossover, and mutation. All these are designed to iteratively refine solutions toward the global optimum.

4.2.1. Key Parameters of GA

In the genetic algorithm adopted in this study, the settings of key parameters were determined to balance algorithm performance and practical application requirements. The population size was set to 50 to achieve a balance between computational efficiency and search diversity. The iteration number was specified as 100, and the algorithm terminated when the fitness converged. The crossover probability (Pc) was set to 0.8, which was sufficiently high to effectively promote gene recombination. The mutation probability (Pm) was set to 0.01. It was low enough to avoid excessive randomness interference while being high enough to help the algorithm escape local optima. The encoding method adopted real-number encoding, which can directly map hyperparameters to GA individuals and thus avoid errors that may be introduced by binary encoding.

4.2.2. Genetic Operations

Roulette wheel selection was used in selection. The probability of an individual being selected for reproduction is proportional to its fitness. The selection probability (

Psel(

xi)) for individual

xi is defined in Equation (10):

Here, f(xi) is the fitness of individual xi, and N is the population size. This method prioritizes individuals with better fitness to ensure that favorable hyperparameter combinations are passed to subsequent generations.

Single-point crossover was implemented. A random crossover point k was selected for two parent individuals x1 = [a1, a2, …, ak, …, al] and x2 = [b1, b2, …, bk, …, bl]. L is the encoding length, equal to the number of CatBoost hyperparameters. Two offspring x1′ = [a1, …, ak, bk+1, …, bl] and x2′ = [b1, …, bk, ak+1, …, al] were generated by swapping segments of the parents. This operation efficiently combined beneficial traits from both parents to explore new hyperparameter combinations.

Mutation involved introducing small random perturbations to individual hyperparameter values for real-number encoding. The mutation probability (Pm = 0.01) ensured that changes were infrequent enough to preserve good solutions but frequent enough to avoid stagnation in local optima.

The GA operated in a cycle by initializing a population of hyperparameter combinations, calculating the fitness of each individual, and applying selection/crossover/mutation to generate a new population. It repeated until the maximum number of iterations was reached or fitness converged. This cycle ensured that the algorithm efficiently searched for the global optimum in CatBoost’s hyperparameter space.

4.3. GA-CatBoost Hybrid Model

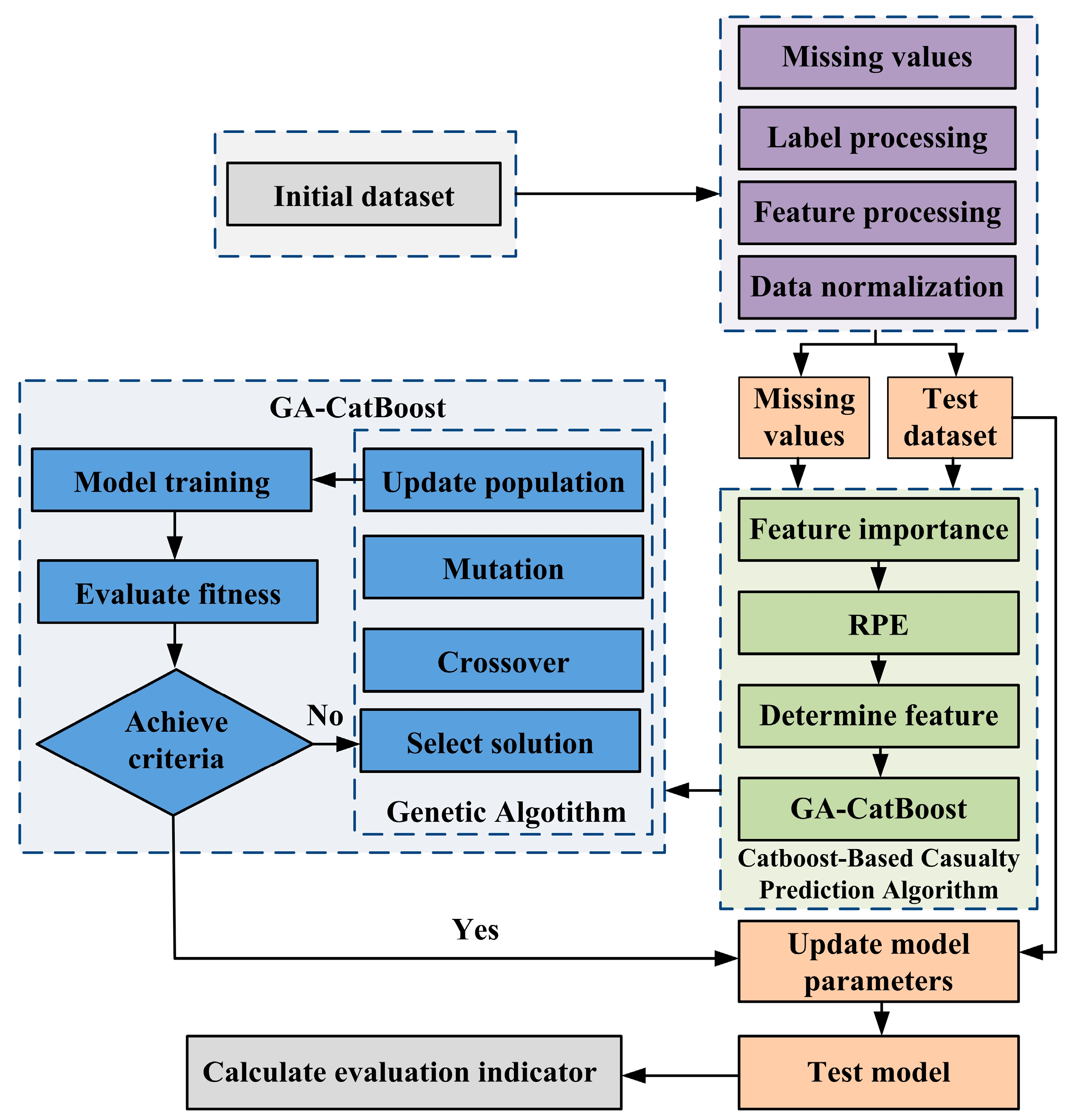

The GA-CatBoost hybrid model addresses the inefficiency of manual CatBoost hyperparameter tuning by leveraging GA’s global optimization capabilities. The workflow illustrated in

Figure 2 integrates data preprocessing, GA-driven hyperparameter optimization, and CatBoost model training/evaluation to ensure accurate yield prediction under small samples.

4.3.1. Hyperparameter Optimization Scope

The key CatBoost hyperparameters and their search ranges shown in

Table 4 were determined via literature review and preliminary experiments to ensure coverage of values that balance model accuracy and complexity [

14,

25].

The learning rate range [0.01, 0.3] prevents excessively slow training or unstable convergence, while the tree depth range [3, 10] avoids underfitting and overfitting in small samples.

4.3.2. Fitness Function

The fitness function in this genetic algorithm optimization framework is designed as a multi-objective evaluation criterion that balances prediction accuracy against model complexity. The function is defined in Equation (11):

where

MAEmean represents the mean absolute error averaged across both output targets through 5-fold cross-validation,

Ntotal denotes the total available features and is 4 in this study.

Nselected indicates the number of features actively used.

λ serves as a regularization coefficient and is set to 0.01. This formulation addresses two competing objectives simultaneously: the primary component (−

MAEmean) drives the optimization toward higher prediction accuracy by minimizing the cross-validated error across both output targets, while the secondary penalty term (−0.01 × (4 −

Nselected)) encourages feature sparsity and model simplicity by penalizing unused features.

4.3.3. Implementation Steps

First, data preprocessing was conducted. The 88 experimental samples were split into a training set of 70 samples (accounting for 80%) and a test set of 18 samples (representing 20%) using stratified sampling. A GA population consisting of 50 individuals was randomly generated within the hyperparameter search range for GA initialization. Each individual was used to train a CatBoost model with the training set for fitness calculation. The model’s mean squared error (MSE) on the validation set was calculated to determine the individual’s fitness. Subsequently, the genetic operations, including selection, crossover, and mutation were performed to generate a new population. These two steps with fitness calculation and genetic operations were repeated for 100 iterations. The individual with the highest fitness was selected as the optimal hyperparameter combination Θ* after the iterations. Finally, a CatBoost model shown in

Figure 7 was trained using the optimal hyperparameter combination Θ* and the training set. Its performance was evaluated on the test set.

4.4. Implementation Details

All codes for the GA-CatBoost model and comparative algorithm simulations were developed in-house using Python 3.9, with the programming environment built on Anaconda 2022.10 (64-bit, Windows 10) to ensure consistent package management. Core open-source libraries and their versions include catboost 1.1.1 for CatBoost model implementation and categorical feature processing; scikit-learn 1.2.2 for data preprocessing, cross-validation, performance metric calculation, and comparative algorithm implementation with grid search tuning; numpy 1.24.3 and pandas 1.5.3 for data loading, cleaning and numerical operations; and deap 1.3.3 for custom genetic algorithm design for CatBoost hyperparameter optimization. All codes follow standard Python practices, with detailed documentation for key steps to facilitate reproducibility.

5. Conclusions

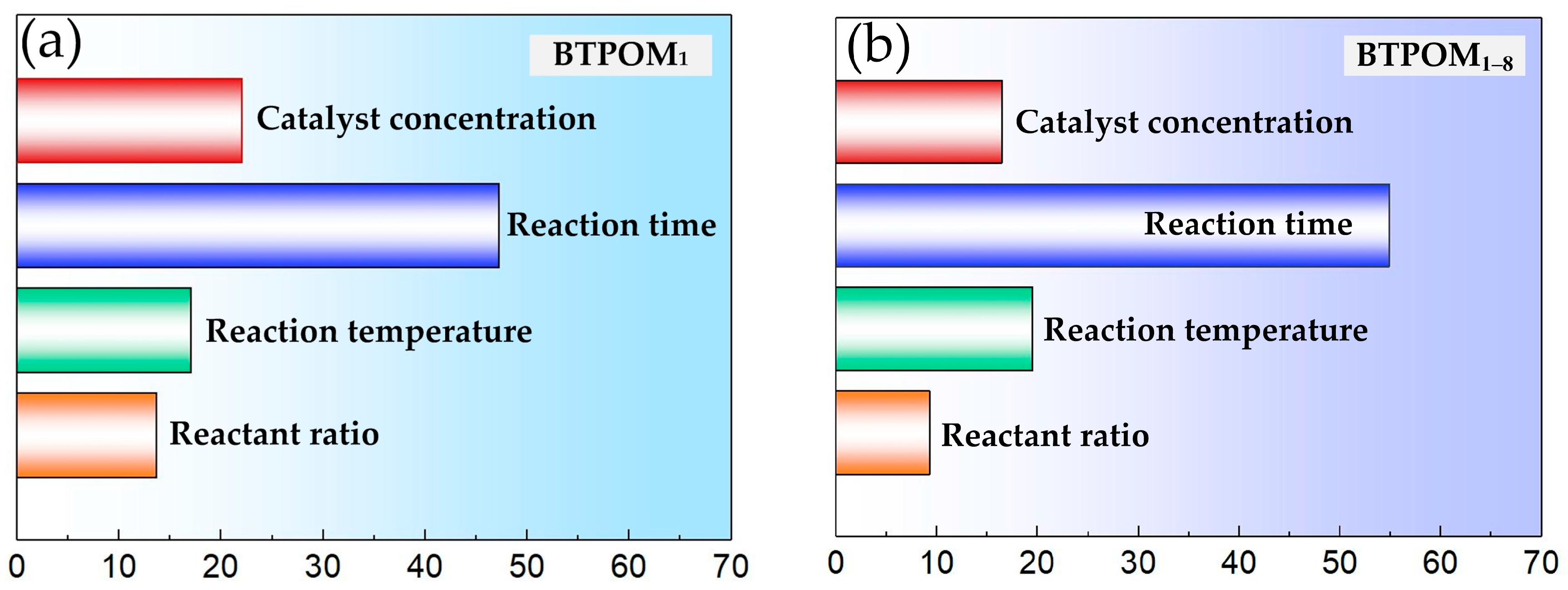

This study addressed the challenge of BTPOMn yield prediction under small sample conditions with 88 experimental sets by developing a GA-CatBoost hybrid model. The main conclusions are the following. The GA-CatBoost model effectively predicts BTPOM1 and BTPOM1–8 yields using four input variables, including reactant ratio, reaction temperature, reaction time, and catalyst concentration. The model overcomes the limitations of traditional mechanistic models and manually tuned machine learning models by integrating GA-driven hyperparameter optimization with CatBoost’s robust ensemble structure. GA optimization significantly enhanced CatBoost’s performance. Relative to the GA-AdaBoost model, GA-CatBoost reduced MSE by 50.1 to 54.0%, MAE by 40.6 to 45.0%, and MAPE by 17.8 to 33.8%. Meanwhile, the coefficient of determination increased by 10% (from 0.80 to 0.90) for BTPOM1 and 8% (from 0.84 to 0.92) for BTPOM1–8, confirming a stronger input–output relationship. It exhibits larger improvements for the more complex BTPOM1–8 target. It also outperformed SVR, RF, and KNN, confirming its superiority in accuracy and generalization for small sample data. Feature importance analysis identified the reaction time with an F-score of about 54.9 and reaction temperature with an F-score of about 19.4 as the dominant factors influencing BTPOMn yields. However, catalyst concentration with the F-score of about 6 had minimal impact. Based on these insights, the following optimal operating conditions are recommended: 2–4 h reaction time, 100–120 °C reaction temperature, 2:1–1:1 reactant ratio, and 5–7 wt.% catalyst concentration.

Future work should extend this research by expanding the sample size to 200–300 sets. Additionally, more efficient optimization algorithms, such as PSO and gray wolf optimizer, can be explored to reduce training time. The experimental parameter range in subsequent research should be extended to further enhance the generalizability and practical applicability of the GA-CatBoost model, thereby broadening the model’s yield prediction scope to cover more diverse scenarios from low to high yields. This expansion will enable the model to provide more comprehensive guidance for the optimization of BTPOMn synthesis processes under different operating conditions. Additional variables, including stirring speed and reaction pressure, can be incorporated to build a more comprehensive prediction model. This would further enhance the model’s utility for BTPOMn synthesis optimization and broader oxygenated fuel research.