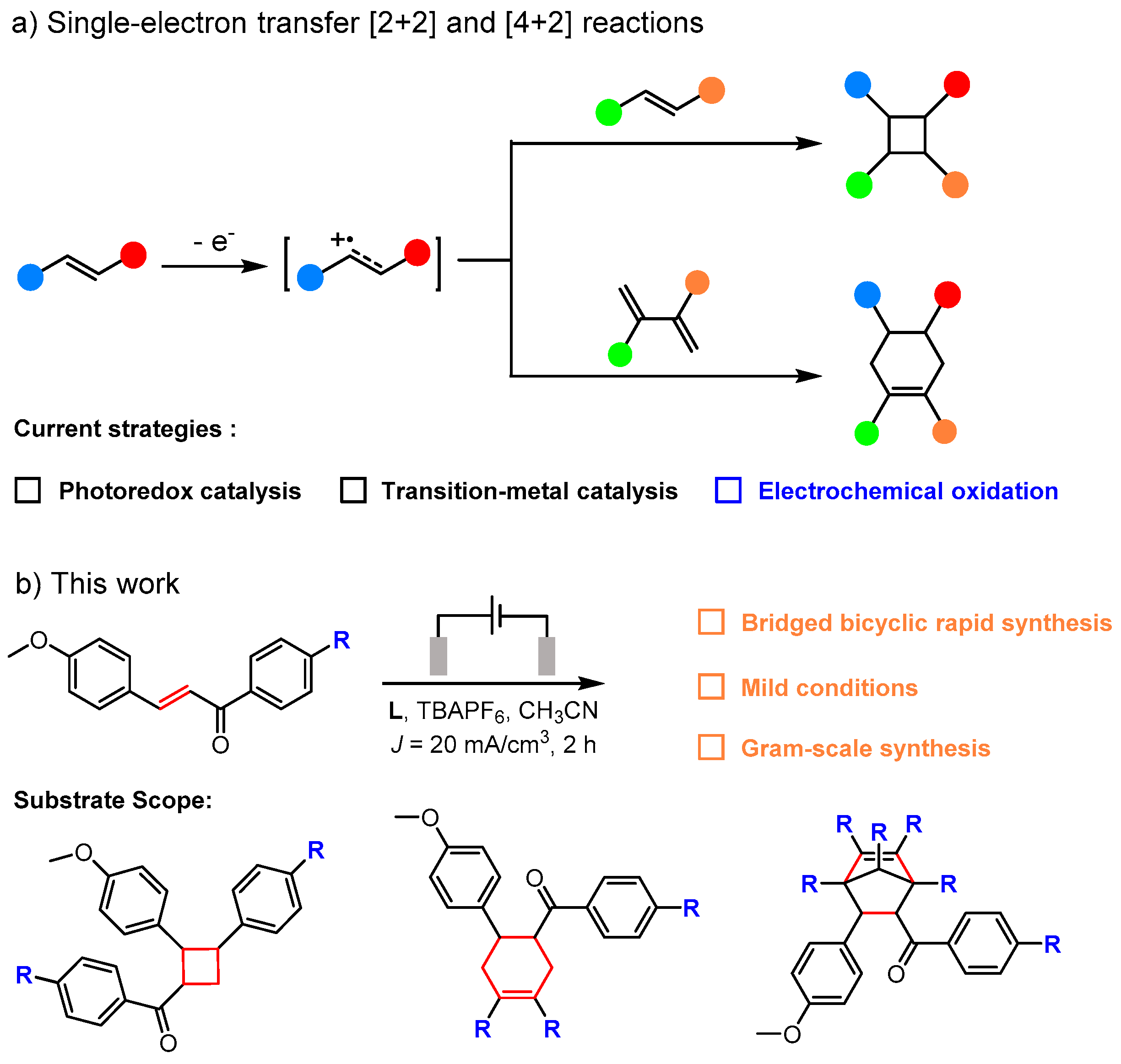

Electrochemical [4+2] and [2+2] Cycloaddition for the Efficient Synthesis of Six- and Four-Membered Carbocycles

Abstract

1. Introduction

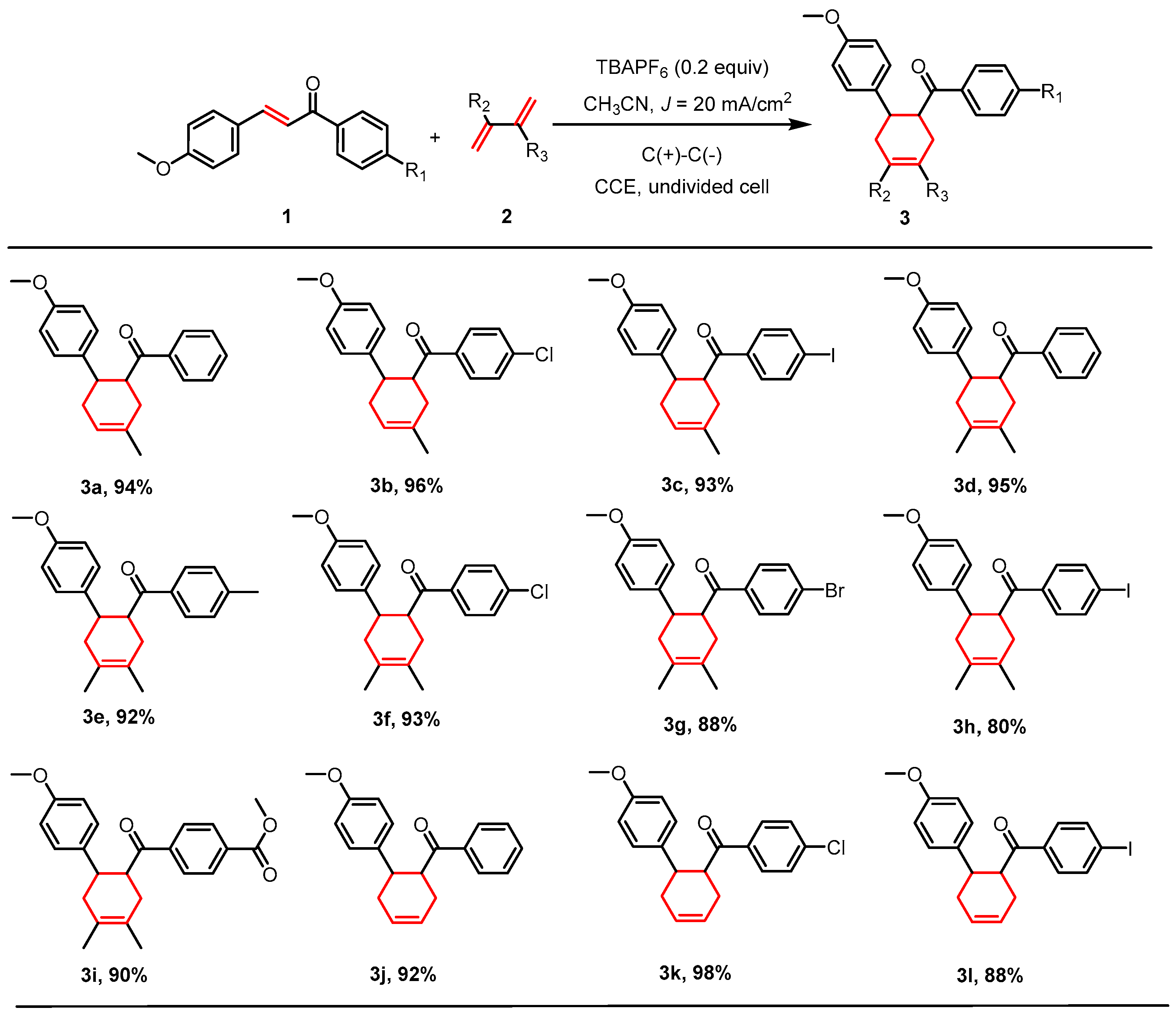

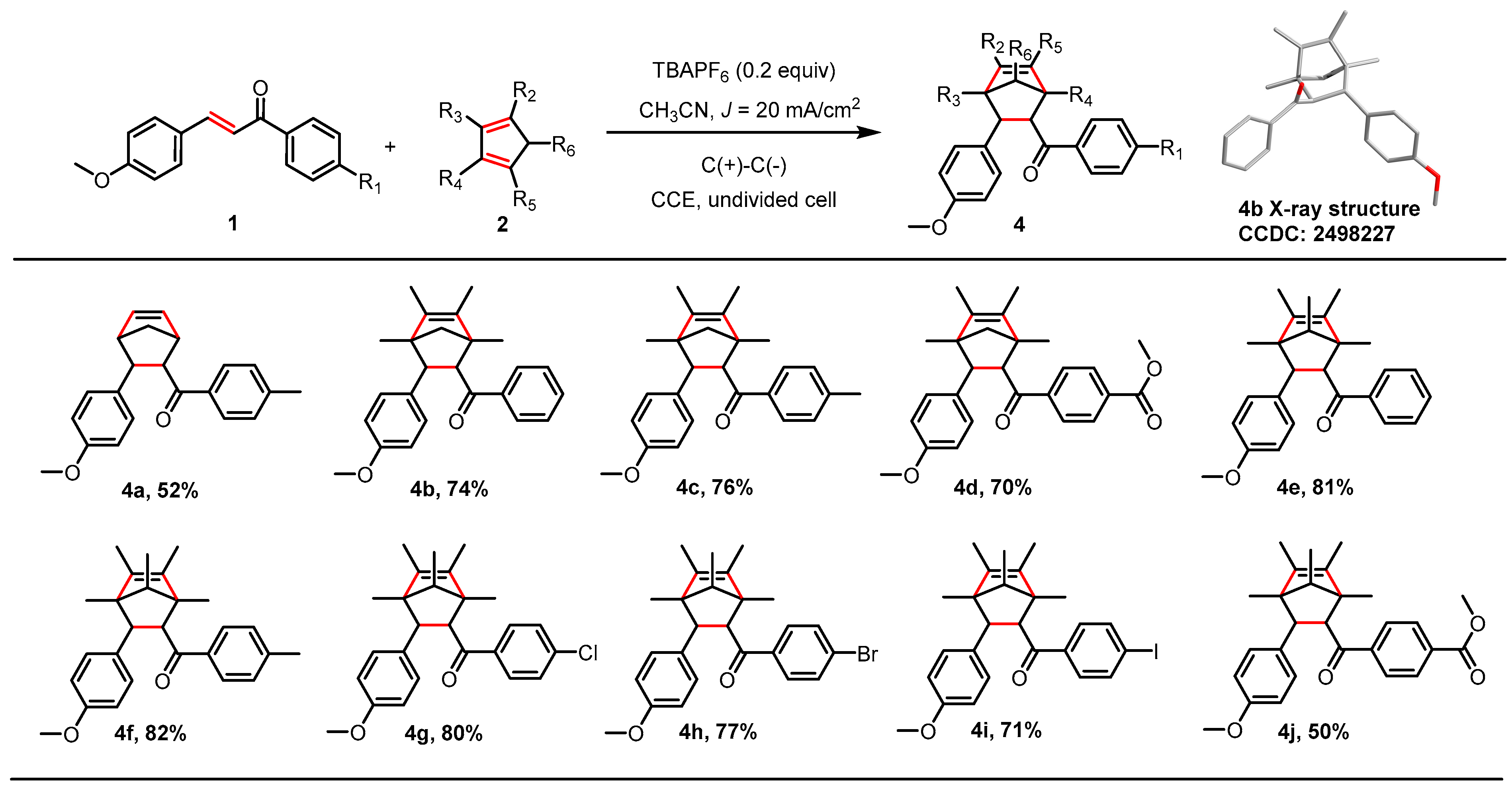

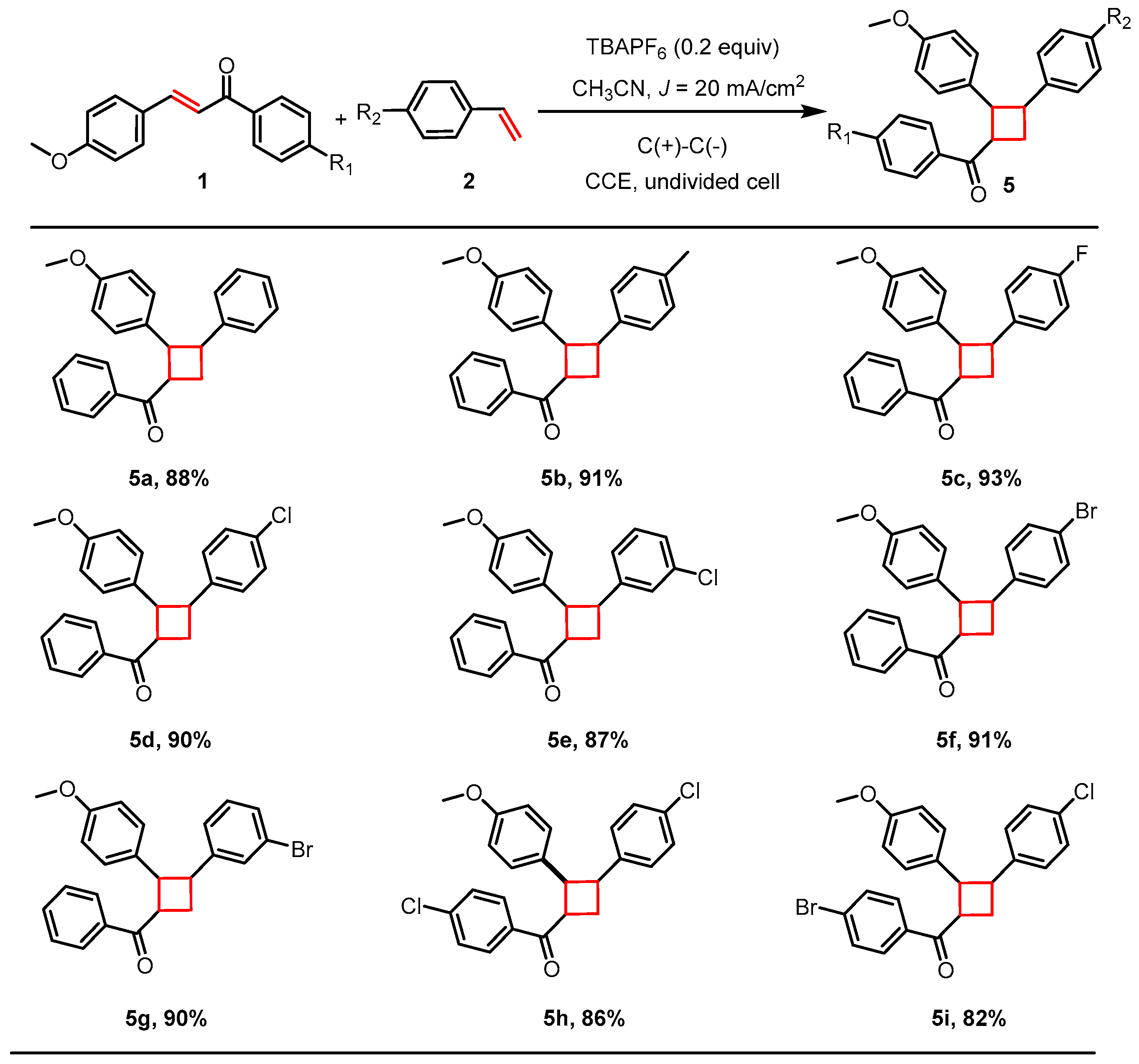

2. Results

2.1. Optimization Studies

2.2. [4+2] Cycloaddition

2.3. [2+2] Cycloaddition

2.4. Mechanism

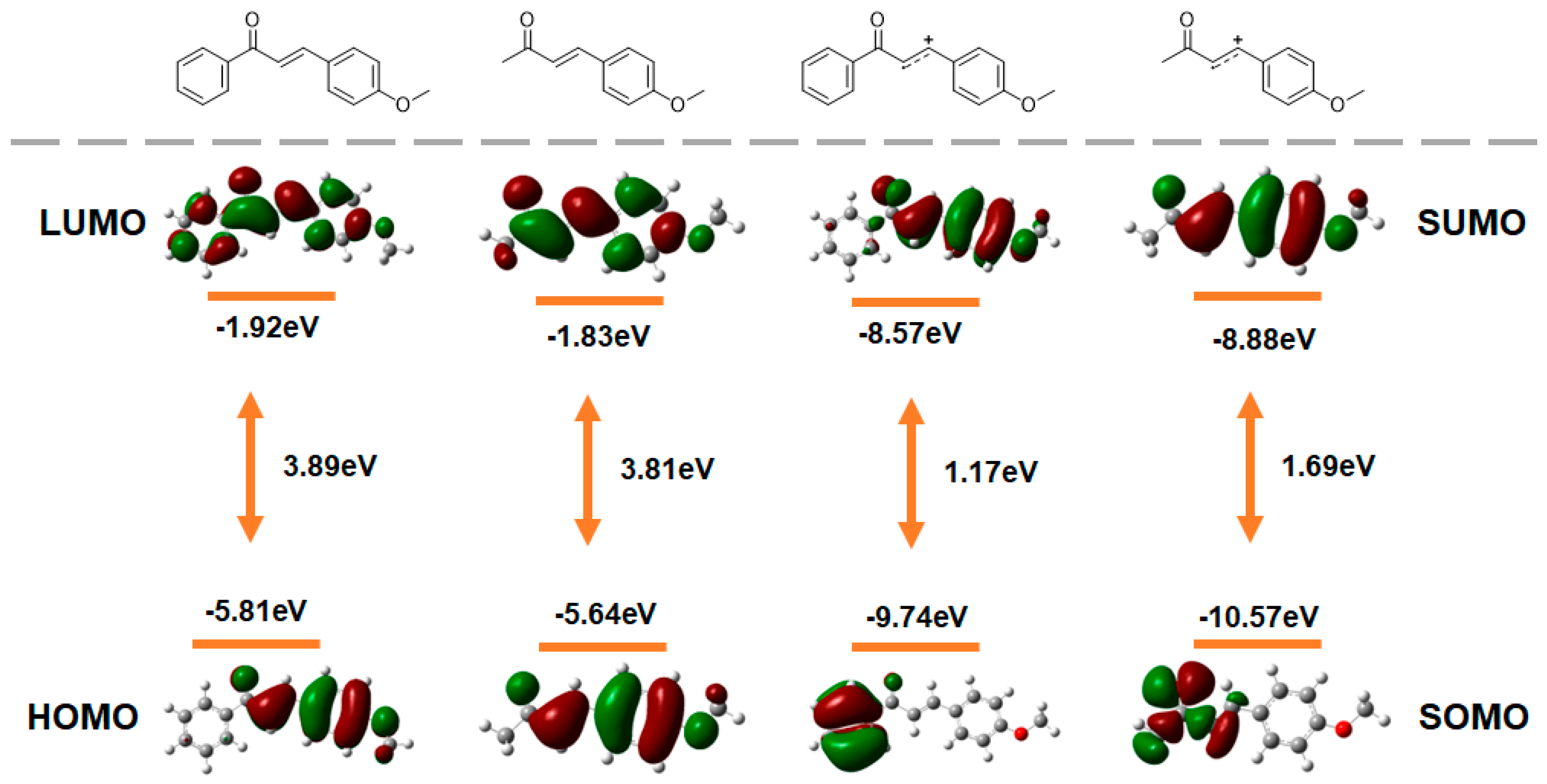

2.5. DFT Calculations

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBAPF6 | Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate |

| TBAC | Tetrabutylammonium chloride |

| TBAB | Tetrabutylammonium bromide |

| TBAI | Tetrabutylammonium iodide |

| NR | No reaction |

References

- Leech, M.C.; Lam, K. A practical guide to electrosynthesis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Zhu, J.; Kong, X.; Geng, Z. Recent development and future perspectives for the electrosynthesis of hydroxylamine and its derivatives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 10140–10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heravi, M.M.; Zadsirjan, V.; Kouhestanian, E.; AlimadadiJani, B. Electrochemically Induced Diels-Alder Reaction: An Overview. Chem. Rec. 2019, 19, 273–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Ibrar, A.; Shehzadi, S.A. Building molecular complexity through transition-metal-catalyzed oxidative annulations/cyclizations: Harnessing the utility of phenols, naphthols and 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 380, 440–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strieth-Kalthoff, F.; James, M.J.; Teders, M.; Pitzer, L.; Glorius, F. Energy transfer catalysis mediated by visible light: Principles, applications, directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7190–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H.H.; Pecoraro, M.V.; Chirik, P.J. Pyridine(diimine) Chromium η1η3-Metallacycles as Precatalysts for Alkene-Diene [2+2] Cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 13688–13698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.L.; An, Y.Y.; Sun, L.Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Hahn, F.E.; Han, Y.F. Supramolecular Control of Photocycloadditions in Solution: In Situ Stereoselective Synthesis and Release of Cyclobutanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3986–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Bai, S.; Zhu, Q.W.; Wei, Z.H.; Han, Y.F. Supramolecular Template-Assisted Catalytic [2+2] Photocycloaddition in Homogeneous Solution. CCS Chem. 2023, 5, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffieux, D.; Fabre, I.; Titz, A.; Léger, J.-M.; Quideau, S. Electrochemical Synthesis of Dimerizing and Nondimerizing Orthoquinone Monoketals. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 8731–8738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reymond, S.; Cossy, J. Copper-Catalyzed Diels−Alder Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 5359–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratwani, C.R.; Kamali, A.R.; Abdelkader, A.M. Self-healing by Diels-Alder cycloaddition in advanced functional polymers: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 131, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, K.; Kim, S. Anodic Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation in Lithium Perchlorate/Nitromethane Electrolyte Solution. Electrochemistry 2009, 77, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, K.; Tada, M. Diels-Alder Reaction of Quinones generated in situ by Electrochemical Oxidation in Lithium Perchlorate-Nitromethane. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 21, 2485–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quideau, S.; Fabre, I.; Deffieux, D. First Asymmetric Synthesis of Orthoquinone Monoketal Enantiomers via Anodic Oxidation. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4571–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, D.; Pakravan, N.; Nematollahi, D. The green and convergent paired Diels-Alder electro-synthetic reaction of 1,4-hydroquinone with 1,2-bis(bromomethyl)benzene. Electrochem. Commun. 2014, 49, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, D.; Pakravan, N.; Nematollahi, D. Green and efficient one-pot Diels-Alder electro-organic cyclization reaction of 1,2-bis(bromomethyl)benzene with naphthoquinone derivatives. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2015, 759, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utley, J.H.P.; Oguntoye, E.; Smith, C.Z.; Wyatt, P.B. Electro-organic reactions. Part 52: Diels-Alder reactions in aqueous solution via electrogenerated quinodimethanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 7249–7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imada, Y.; Okada, Y.; Chiba, K. Investigating radical cation chain processes in the electrocatalytic Diels-Alder reaction. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, R.; Okada, Y.; Chiba, K. Stepwise radical cation Diels-Alder reaction via multiple pathways. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, X.; Lu, L.; Song, X.-R.; Luo, M.-J.; Xiao, Q. Recent Advances in Electrocatalytic Generation of Indole-Derived Radical Cations and Their Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Okada, Y.; Chiba, K. Bidirectional Access to Radical Cation Diels-Alder Reactions by Electrocatalysis. ChemElectroChem 2017, 4, 1852–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zheng, C.; Lin, J.; Huang, W.; Song, D.; Zhong, W.; Ling, F. Asymmetric Counteranion-Directed Electrocatalysis for Enantioselective Control of Radical Cation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 64, e202413601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.-J.; Xiao, Q.; Li, J.-H. Electro-/photocatalytic Alkene-Derived Radical Cation Chemistry: Recent Advances in Synthetic Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 7206–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Chiba, K. Aromatic ‘Redox Tag’-assisted Diels-Alder reactions by electrocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 6387–6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Nie, L.; Zhang, G.; Lei, A. Electrochemical Oxidative [4+2] Annulation for the π-Extension of Unfunctionalized Hetero-biaryl Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15238–15243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Do, T.-N. Electrosynthesis of Four-Membered Ring Systems. Tetrahedron 2025, 185, 134786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, I.; Shaabanzadeh, S. Migration from Photochemistry to Electrochemistry for [2+2] Cycloaddition Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 9257–9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, K.; Jiang, X.; Dong, X.; Weng, Y.; Chiang, C.-W.; Lei, A. Electrooxidation Enables Selective Dehydrogenative [4+2] Annulation between Indole Derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7193–7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xu, C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Song, D.; Zhong, W.; Ling, F. Ligand Promoted and Cobalt Catalyzed Electrochemical C−H Annulation of Arylphosphinamide and Alkyne. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 1877–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupka, J. Kinetics of Diels-Alder reactions between 1,3-cyclopentadiene and isoprene. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2015, 116, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, S.M.; Higgins, R.F.; Shores, M.P.; Ferreira, E.M. Chromium photocatalysis: Accessing structural complements to Diels-Alder adducts with electron-deficient dienophiles. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horibe, T.; Katagiri, K.; Ishihara, K. Radical-Cation-Induced Crossed[2+2] Cycloaddition of Electron-Deficient Anetholes Initiated by Iron(III) Salt. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 960–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisada, T.; Maeda, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Triarylmethyl Cations as Photocatalysts for Radical-Mediated Cycloaddition Reactions. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 4366–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhong, F. Benign catalysis with iron: Facile assembly of cyclobutanes and cyclohexenes via intermolecular radical cation cycloadditions. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1743–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaseelan, R.; Liu, W.; Zuo, J.; Naesborg, L. Methyl viologen as a catalytic acceptor for electron donor-acceptor photoinduced cyclization reactions. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 1969–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horibe, T.; Ohmura, S.; Ishihara, K. Structure and Reactivity of Aromatic Radical Cations Generated by FeCl3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1877–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Li, C.-C. Total Synthesis of Natural Products Containing a Bridgehead Double Bond. Chem 2020, 6, 579–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.; Hu, Y.-J.; Fan, J.-H.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.-C. Synthetic applications of type II intramolecular cycloadditions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7015–7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontana-Uribe, B.A.; Little, R.D.; Ibanez, J.G.; Palma, A.; Vasquez-Medrano, R. Organic electrosynthesis: A promising green methodology in organic chemistry. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 2099–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, J.B.; Wright, D.L. The application of cathodic reductions and anodic oxidations in the synthesis of complex molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K.A.; Boydston, A.J. Recent Developments in Organocatalyzed Electroorganic Chemistry. Chem. Lett. 2015, 44, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, P.; Shridhar, G.; Ladage, S.; Ravishankar, L. An Eco-Friendly Synthesis of 2-Pyrazoline Derivatives Catalysed by CeCl3·7H2O. J. Chem. Sci. 2017, 129, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palleros, D.R. Solvent-Free Synthesis of Chalcones. J. Chem. Educ. 2004, 81, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpani, C.G.; Mishra, S. Lewis Acid Catalyst System for Claisen-Schmidt Reaction Under Solvent Free Condition. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 152175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision E.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2013.

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. B. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||

| Entry | electrolyte (0.2 M) | current (mA/cm2) | anode/cathode | Yield (%) b |

| 1 | TBAC | 20 | C(+)|C(−) | trace |

| 2 | TBAB | 20 | C(+)|C(−) | NR |

| 3 | TBAI | 20 | C(+)|C(−) | NR |

| 4 | TBAClO4 | 20 | C(+)|C(−) | 88 |

| 5 | TBAPF6 | 5 | C(+)|C(−) | 45 |

| 6 | TBAPF6 | 10 | C(+)|C(−) | 68 |

| 7 | TBAPF6 | 20 | C(+)|C(−) | 94 |

| 8 | TBAPF6 | 0 | C(+)|C(−) | NR |

| 9 | TBAPF6 | 20 | Pt(+)|C(−) | trace |

| 10 | TBAPF6 | 20 | C(+)|Pt(−) | 90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, R.; Wang, F.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Gao, Z. Electrochemical [4+2] and [2+2] Cycloaddition for the Efficient Synthesis of Six- and Four-Membered Carbocycles. Molecules 2025, 30, 4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234604

Xu R, Wang F, Shen Y, Wang Z, Zhen Y, Gao Z. Electrochemical [4+2] and [2+2] Cycloaddition for the Efficient Synthesis of Six- and Four-Membered Carbocycles. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234604

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Runsen, Fang Wang, Yifan Shen, Zhenhua Wang, Yanzhong Zhen, and Ziwei Gao. 2025. "Electrochemical [4+2] and [2+2] Cycloaddition for the Efficient Synthesis of Six- and Four-Membered Carbocycles" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234604

APA StyleXu, R., Wang, F., Shen, Y., Wang, Z., Zhen, Y., & Gao, Z. (2025). Electrochemical [4+2] and [2+2] Cycloaddition for the Efficient Synthesis of Six- and Four-Membered Carbocycles. Molecules, 30(23), 4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234604