Miniaturised Extraction Techniques in Personalised Medicine: Analytical Opportunities and Translational Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analytical Requirements in Personalised Medicine

2.1. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

2.2. Bioanalysis in Vulnerable and Special Populations

2.3. Remote and Home-Based Sampling

3. Miniaturised Extraction Techniques and Their Analytical Suitability

3.1. Dried Matrix Spots (DMS)

3.2. Microextraction by Packed Sorbent (MEPS)

3.3. Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME)

3.4. Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction (FPSE)

3.5. Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction (DLLME)

3.6. Emerging Approaches

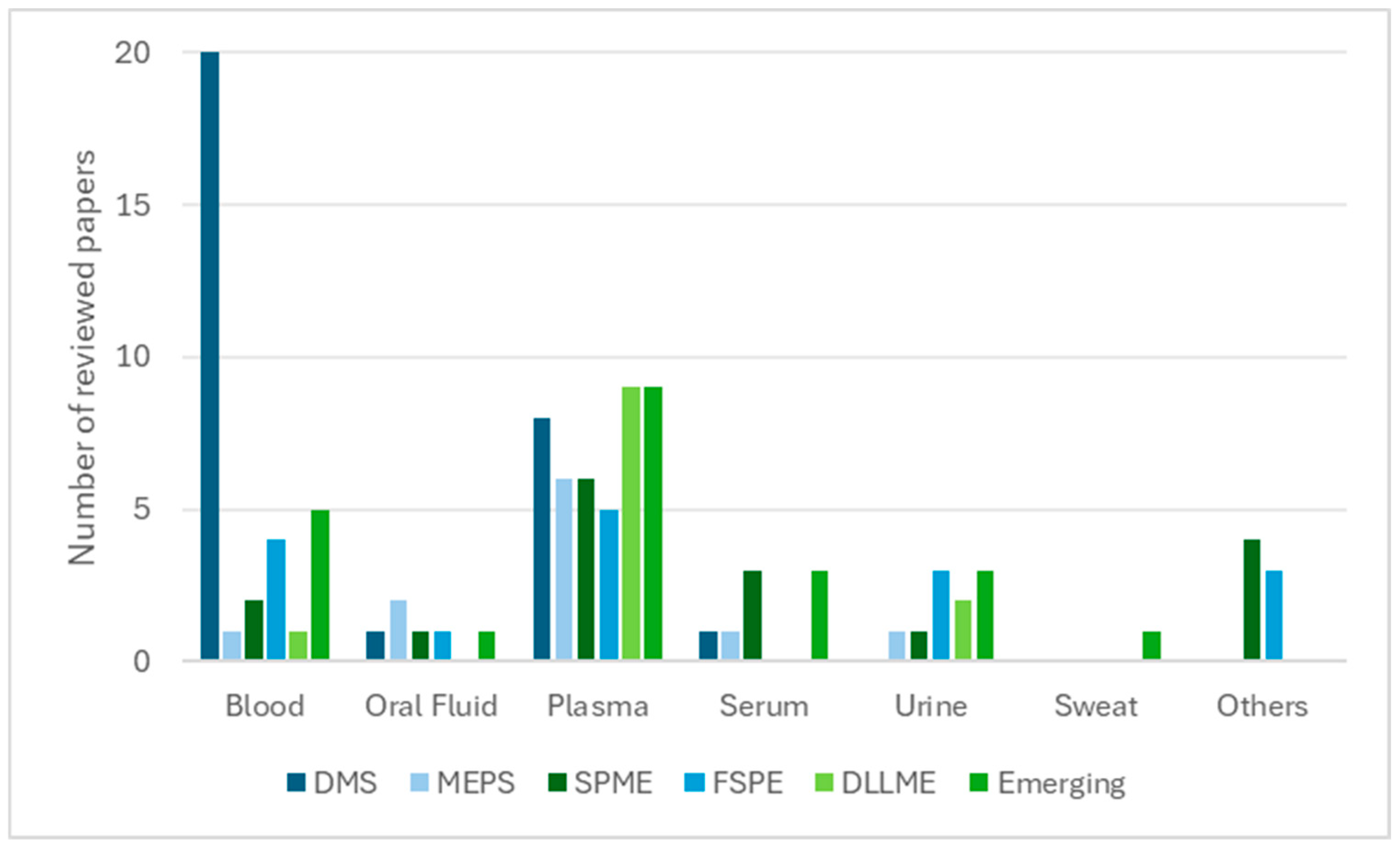

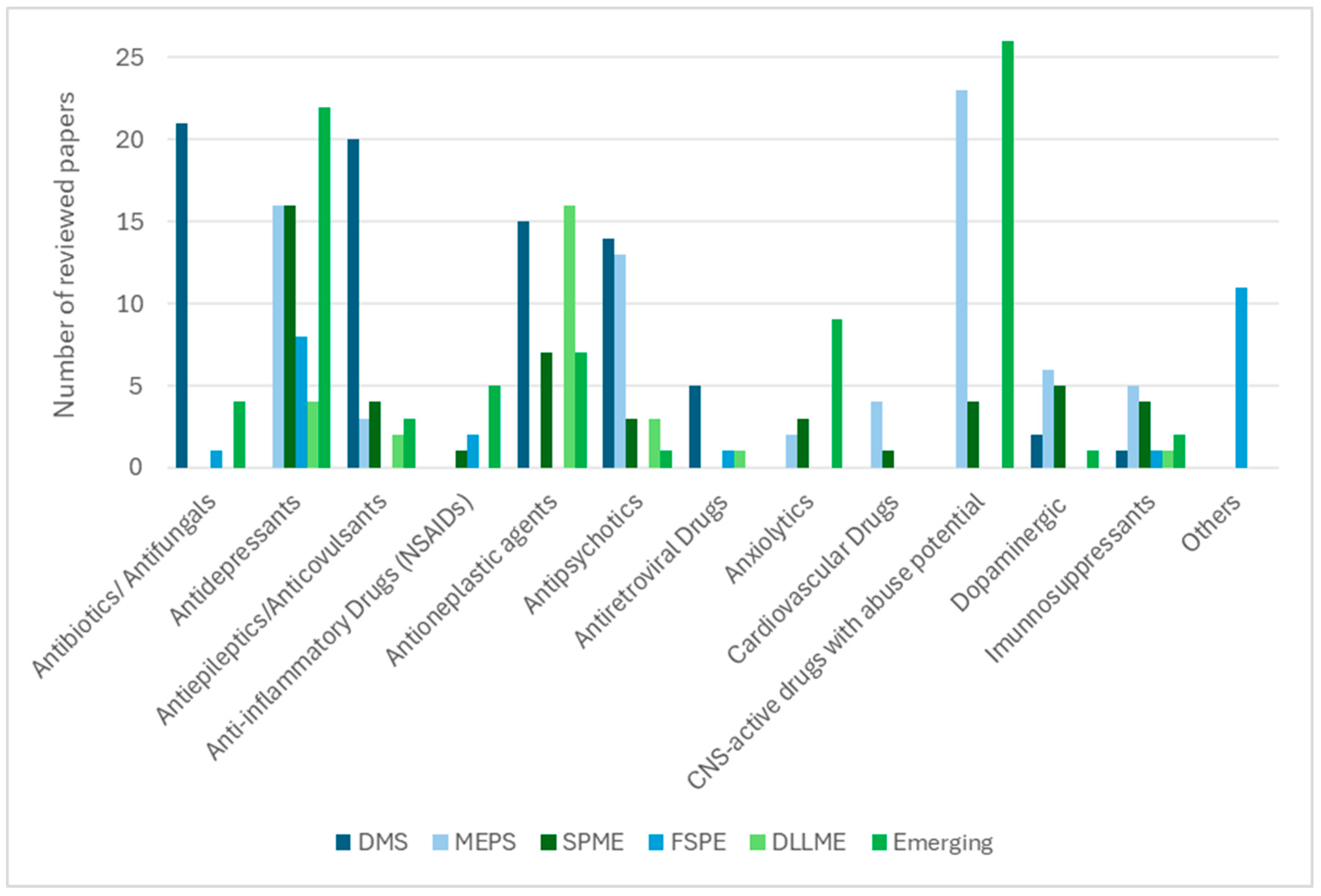

3.7. General Discussion

4. Regulatory Considerations and Validation Challenges

5. Future Gaps and Translational Opportunities

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, W.S.; Beaulieu-Jones, B.; Smalley, S.; Snyder, M.; Goetz, L.H.; Schork, N.J. Emerging therapeutic drug monitoring technologies: Considerations and opportunities in precision medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1348112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xiao, S.; Liu, Y.; Bai, M.; Gong, L.; Zhao, J.; Chen, D. Revolutionizing precision medicine: Exploring wearable sensors for therapeutic drug monitoring and personalized therapy. Biosensors 2023, 13, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, J.M.; Asempa, T.E.; Abdelraouf, K. Therapeutic drug monitoring. In Remington; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.; Pati, R.N.; Mahajan, S.; Yadav, S. The significance of therapeutic drug monitoring: Investigating clinical and forensic toxicology. J. Appl. Bioanal. 2024, 10, 68–95. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, S.; Rosado, T.; Barroso, M.; Gallardo, E. Solid phase-based microextraction techniques in therapeutic drug monitoring. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tey, H.Y.; See, H.H. A review of recent advances in microsampling techniques of biological fluids for therapeutic drug monitoring. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1635, 461731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rehim, M.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S.; Abdel-Rehim, A.; Lucena, R.; Moein, M.M.; Cárdenas, S.; Miró, M. Microextraction approaches for bioanalytical applications: An overview. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1616, 460790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, A.; Conti, M.; Pigliasco, F.; Barco, S.; Bandettini, R.; Cangemi, G. Biological fluid microsampling for therapeutic drug monitoring: A narrative review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avataneo, V.; D’Avolio, A.; Cusato, J.; Cantù, M.; De Nicolò, A. LC–MS application for therapeutic drug monitoring in alternative matrices. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 166, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocur, A.; Pawiński, T. Volumetric absorptive microsampling in therapeutic drug monitoring of immunosuppressive drugs—From sampling and analytical issues to clinical application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rose, D.U.; Cairoli, S.; Dionisi, M.; Santisi, A.; Massenzi, L.; Goffredo, B.M.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Dotta, A.; Auriti, C. Therapeutic drug monitoring is a feasible tool to personalize drug administration in neonates using new techniques: An overview on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in neonatal age. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, M.E.I.; El-Nouby, M.A.M.; Kimani, P.K.; Lim, L.W.; Rabea, E.I. A review of the modern principles and applications of solid-phase extraction techniques in chromatographic analysis. Anal. Sci. 2022, 38, 1457–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H. Solventless microextraction techniques for pharmaceutical analysis: The greener solution. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 785830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, N.N.B.; Ho, P.C.L. Dried blood spots—A platform for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and drug/disease response monitoring (DRM). Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2023, 48, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Concheiro-Guisan, M. Microextraction sample preparation techniques in forensic analytical toxicology. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2019, 33, e4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugheri, S.; Mucci, N.; Cappelli, G.; Trevisani, L.; Bonari, A.; Bucaletti, E.; Squillaci, D.; Arcangeli, G. Advanced solid-phase microextraction techniques and related automation: A review of commercially available technologies. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2022, 2022, 8690569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Aghamohammadhassan, M.; Ghorbani, H.; Zabihi, A. Trends in sorbent development for dispersive micro-solid phase extraction. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perestrelo, R.; Silva, P.; Porto-Figueira, P.; Pereira, J.A.M.; Silva, C.; Medina, S.; Câmara, J.S. QuEChERS—Fundamentals, relevant improvements, applications and future trends. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1070, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, S.H.; Kaykhaii, M. Porous polymer sorbents in micro solid phase extraction: Applications, advantages, and challenges. Top. Curr. Chem. 2024, 382, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Tan, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhan, X.; Yin, J. Mass spectrometry-based personalized drug therapy. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2020, 39, 523–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, R.G.; Zeng, S.; Jiang, H.; Fang, W.J. Current developments of bioanalytical sample preparation techniques in pharmaceuticals. J. Pharm. Anal. 2022, 12, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, V.P.; Ibrahim, S.; Zahedi, R.P.; Borchers, C.H. Utility, promise, and limitations of liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry-based therapeutic drug monitoring in precision medicine. J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 56, e4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use: Guideline on Bioanalytical Method Validation, EMEA/CHMP/EWP/192217/2009 Rev. 1 Corr. 2. Available online: www.ema.europa.eu/contact (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Bioanalytical Method Validation—Guidance for Industry. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). M10—Bioanalytical Method Validation and Study Sample Analysis. Available online: https://www.ich.org (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Cao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. Simultaneous monitoring of seven antiepileptic drugs by dried blood spot and dried plasma spot sampling: Method validation and clinical application of an LC–MS/MS-based technique. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 243, 116099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trontelj, J.; Rozman, A.; Mrhar, A. Determination of remifentanil in neonatal dried blood spots by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Acta Pharm. 2024, 74, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francke, M.I.; Peeters, L.E.J.; Hesselink, D.A.; Kloosterboer, S.M.; Koch, B.C.P.; Veenhof, H.; De Winter, B.C.M. Best practices to implement dried blood spot sampling for therapeutic drug monitoring in clinical practice. Ther. Drug Monit. 2022, 44, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Câmara, J.S.; Perestrelo, R.; Olayanju, B.; Berenguer, C.V.; Kabir, A.; Pereira, J.A.M. Overview of different modes and applications of liquid phase-based microextraction techniques. Processes 2022, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavelu, M.U.; Wouters, B.; Kindt, A.; Reiss, I.K.M.; Hankemeier, T. Blood microsampling technologies: Innovations and applications in 2022. Anal. Sci. Adv. 2023, 4, 154–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyroteo, M.; Ferreira, I.A.; Elvas, L.B.; Ferreira, J.C.; Lapão, L.V. Remote monitoring systems for patients with chronic diseases in primary health care: Systematic review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2021, 9, e28285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, O.; Chiu, S.W.; Nakazawa, T.; Tsuda, S.; Yoshida, M.; Asano, T.; Kokubun, T.; Hashimoto, K.; Takata, M.; Ikeda, S.; et al. Effectiveness of remote risk-based monitoring and potential benefits for combination with direct data capture. Trials 2024, 25, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rashidy, N.; El-Sappagh, S.; Riazul Islam, S.M.; El-Bakry, H.M.; Abdelrazek, S. Mobile health in remote patient monitoring for chronic diseases: Principles, trends, and challenges. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malasinghe, L.P.; Ramzan, N.; Dahal, K. Remote patient monitoring: A comprehensive study. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 10, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianculescu, M.; Nicolau, D.N.; Alexandru, A. Ensuring the completeness and accuracy of data in a customizable remote health monitoring system. In Proceedings of the 2022 14th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI), Bucharest, Romania, 30 June–2 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbl, J.; Eimer, E.; Gigg, C.; Bendzuck, G.; Korinth, M.; Elling-Audersch, C.; Kleyer, A.; Simon, D.; Boeltz, S.; Krusche, M.; et al. Remote self-collection of capillary blood using upper arm devices for autoantibody analysis in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory rheumatic diseases. RMD Open 2022, 8, e002641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilton, R. Trust and ethical data handling in the healthcare context. Health Technol. 2017, 7, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogvold, H.B.; Rootwelt, H.; Reubsaet, L.; Elgstøen, K.B.P.; Wilson, S.R. Dried blood spot analysis with liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry: Trends in clinical chemistry. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, 2300210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaissmaier, T.; Siebenhaar, M.; Todorova, V.; Hüllen, V.; Hopf, C. Therapeutic drug monitoring in dried blood spots using liquid microjunction surface sampling and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Analyst 2016, 141, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaitumu, M.N.; De Sá e Silva, D.M.; Louail, P.; Rainer, J.; Avgerinou, G.; Petridou, A.; Mougios, V.; Theodoridis, G.; Gika, H. LC–MS-based global metabolic profiles of alternative blood specimens collected by microsampling. Metabolites 2025, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Guo, H.; Ren, W.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. Dried plasma spot-based liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for the quantification of methotrexate in human plasma and its application in therapeutic drug monitoring. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, S.; Cao, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. Dried plasma spot-based LC–MS/MS method for monitoring of meropenem in the blood of treated patients. Molecules 2022, 27, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londhe, V.; Rajadhyaksha, M. Opportunities and obstacles for microsampling techniques in bioanalysis: Special focus on DBS and VAMS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 182, 113102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosé, G.; Tafzi, N.; El Balkhi, S.; Rerolle, J.P.; Debette-Gratien, M.; Marquet, P.; Saint-Marcoux, F.; Monchaud, C. New perspectives for the therapeutic drug monitoring of tacrolimus: Quantification in volumetric DBS based on an automated extraction and LC–MS/MS analysis. J. Chromatogr. B 2023, 1223, 123721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abady, M.M.; Jeong, J.S.; Kwon, H.J. Dried blood spot analysis for simultaneous quantification of antiepileptic drugs using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 39, e10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, T.L.D.; Gössling, G.; Venzon Antunes, M.; Schwartsmann, G.; Linden, R.; Verza, S.G. Evaluation of dried blood spots as an alternative matrix for therapeutic drug monitoring of abiraterone and Δ4-abiraterone in prostate cancer patients. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 195, 113861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancellerini, C.; Caravelli, A.; Esposito, E.; Belotti, L.M.B.; Soldà, M.; Derus, N.; Merlotti, A.; Casadei, F.; Mostacci, B.; Vignatelli, L.; et al. Quantitative dried blood spot microsampling for therapeutic drug monitoring of antiseizure medications by design of experiment and UHPLC–MS/MS. Talanta 2025, 293, 128018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, M.; Yang, J.; Yu, X. Automated DBS–online SPE–LC–MS/MS platform with dynamic solvent dilution: Robust quantification of antipsychotic drugs for decentralized therapeutic drug monitoring. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1263, 124704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orleni, M.; Gagno, S.; Cecchin, E.; Montico, M.; Buonadonna, A.; Fumagalli, A.; Guardascione, M.; Puglisi, F.; Toffoli, G.; Posocco, B.; et al. Imatinib and norimatinib therapeutic monitoring using dried blood spots: Analytical and clinical validation, and performance comparison of volumetric collection devices. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1255, 124526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens-Lobenhoffer, J.; Angermair, S.; Bode-Böger, S.M. Quantification of isavuconazole from dried blood spots: Applicability in therapeutic drug monitoring. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1258, 124590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Qian, S.; Song, D.; Ye, X. LC–MS/MS analysis of five antibiotics in dried blood spots for therapeutic drug monitoring of ICU patients. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1263, 124699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abady, M.M.; Jeong, J.S.; Kwon, H.J. Dried blood spot sampling coupled with liquid chromatography–tandem mass for simultaneous quantitative analysis of multiple cardiovascular drugs. J. Chromatogr. B 2024, 1242, 124215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenfack Teponnou, G.A.; Joubert, A.; Spaltman, S.; van der Merwe, M.; Zangenberg, E.; Sawe, S.; Denti, P.; Castel, S.; Conradie, F.; Court, R.; et al. Development and validation of an LC–MS/MS multiplex assay for the quantification of bedaquiline, n-desmethyl bedaquiline, linezolid, levofloxacin, and clofazimine in dried blood spots. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1252, 124470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchin, E.; Orleni, M.; Gagno, S.; Montico, M.; Peruzzi, E.; Roncato, R.; Gerratana, L.; Corsetti, S.; Puglisi, F.; Toffoli, G.; et al. Quantification of letrozole, palbociclib, ribociclib, abemaciclib, and metabolites in volumetric dried blood spots: Development and validation of an LC–MS/MS method for therapeutic drug monitoring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weld, E.D.; Parsons, T.L.; Gollings, R.; McCauley, M.; Grinsztejn, B.; Landovitz, R.J.; Marzinke, M.A. Development and validation of a liquid chromatographic–tandem mass spectrometric assay for the quantification of cabotegravir and rilpivirine from dried blood spots. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 228, 115307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Pérez, I.G.; Rodríguez-Báez, A.S.; Ortiz-Álvarez, A.; Velarde-Salcedo, R.; Arriaga-García, F.J.; Rodríguez-Pinal, C.J.; Romano-Moreno, S.; del Carmen Milán-Segovia, R.; Medellín-Garibay, S.E. Standardization and validation of a novel UPLC–MS/MS method to quantify first line anti-tuberculosis drugs in plasma and dried blood spots. J. Chromatogr. B 2023, 1228, 123801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, D.; Shao, H. Quantitation of meropenem in dried blood spots using microfluidic-based volumetric sampling coupled with LC–MS/MS bioanalysis in preterm neonates. J. Chromatogr. B 2023, 1217, 123625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Determination of polymyxin B in dried blood spots using LC–MS/MS for therapeutic drug monitoring. J. Chromatogr. B 2022, 1192, 123131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carniel, E.; dos Santos, K.A.; de Andrade de Lima, L.; Kohlrausch, R.; Linden, R.; Antunes, M.V. Determination of clozapine and norclozapine in dried plasma spot and dried blood spot by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 210, 114591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.X.; Yang, F.; van den Anker, J.N.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, W. A simplified method for bortezomib determination using dried blood spots in combination with liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2021, 1181, 122905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelcová, M.; Ďurčová, V.; Šmak, P.; Strýček, O.; Štolcová, M.; Peš, O.; Glatz, Z.; Šištík, P.; Juřica, J. Non-invasive therapeutic drug monitoring: LC–MS validation for lamotrigine quantification in dried blood spot and oral fluid/saliva. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 262, 116877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathyanarayanan, A.; Arekal, R.N.; Somashekara, D. A robust and accurate filter paper–based dried plasma spot method for bictegravir monitoring in HIV therapy. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 39, e10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, A.; Stella, M.; Baiardi, G.; Barco, S.; Pigliasco, F.; Bandettini, R.; Nanni, L.; Mattioli, F.; Cangemi, G. Dried plasma spot as an innovative approach to therapeutic drug monitoring of apixaban: Development and validation of a novel liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry method. J. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 59, e5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, B.; Yuile, A.; McKay, M.J.; Narayanan, S.; Wheeler, H.; Itchins, M.; Pavlakis, N.; Clarke, S.J.; Molloy, M.P. A validated assay to quantify osimertinib and its metabolites, AZ5104 and AZ7550, from microsampled dried blood spots and plasma. Ther. Drug Monit. 2024, 46, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeoli, R.; Cairoli, S.; Galaverna, F.; Becilli, M.; Boccieri, E.; Antonetti, G.; Vitale, A.; Mancini, A.; Rossi, C.; Di Vici, C.; et al. Utilization of volumetric absorptive microsampling and dried plasma spot for quantification of anti-fungal triazole agents in pediatric patients by using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 236, 115688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigliasco, F.; Cafaro, A.; Simeoli, R.; Barco, S.; Magnasco, A.; Faraci, M.; Tripodi, G.; Goffredo, B.M.; Cangemi, G. A UHPLC–MS/MS method for therapeutic drug monitoring of aciclovir and ganciclovir in plasma and dried plasma spots. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, C.L.; Ren, G.J.; Elgierari, E.T.M.; Sturmer, L.R.; Shi, R.Z.; Manicke, N.E.; Kirkpatrick, L.M. Simultaneous quantitation of five triazole anti-fungal agents by paper spray–mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020, 58, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, B.; Fan, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. A simple and rapid HPLC–MS/MS method for therapeutic drug monitoring of amikacin in dried matrix spots. J. Chromatogr. B 2023, 1220, 123592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado, T.; Gallardo, E.; Vieira, D.N.; Barroso, M. Microextraction by packed sorbent. In Microextraction Techniques in Analytical Toxicology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 71–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moein, M.M.; Abdel-Rehim, A.; Abdel-Rehim, M. Microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS). TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 67, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, I.D.; Domingues, D.S.; Queiroz, M.E.C. Hybrid silica monolith for microextraction by packed sorbent to determine drugs from plasma samples by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 2015, 140, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniakiewicz, M.; Wietecha-Posłuszny, R.; Moos, A.; Wieczorek, M.; Knihnicki, P.; Kościelniak, P. Development of microextraction by packed sorbent for toxicological analysis of tricyclic antidepressant drugs in human oral fluid. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1337, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Zhang, Y. Simple, rapid, and cost-effective microextraction by the packed sorbent method for quantifying urinary free catecholamines and metanephrines using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry and its application in clinical analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2763–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, A.M.; Fernández, P.; Regenjo, M.; Fernández, A.M.; Carro, A.M.; Lorenzo, R.A. A fast bioanalytical method based on microextraction by packed sorbent and UPLC–MS/MS for determining new psychoactive substances in oral fluid. Talanta 2017, 174, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.A.M.; Gonçalves, J.; Porto-Figueira, P.; Figueira, J.A.; Alves, V.; Perestrelo, R.; Medina, S.; Câmara, J.S. Current trends on microextraction by packed sorbent—Fundamentals, application fields, innovative improvements and future applications. Analyst 2019, 144, 5048–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.C.; de Faria, H.D.; Figueiredo, E.C.; Queiroz, M.E.C. Restricted access carbon nanotube for microextraction by packed sorbent to determine antipsychotics in plasma samples by high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2465–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercolini, L.; Protti, M.; Fulgenzi, G.; Mandrioli, R.; Ghedini, N.; Conca, A.; Raggi, M.A. A fast and feasible microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) procedure for HPLC analysis of the atypical antipsychotic ziprasidone in human plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 88, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, D.; Sarraguça, M.; Alves, G.; Coutinho, P.; Araujo, A.R.T.S.; Rodrigues, M. A novel HPLC method for the determination of zonisamide in human plasma using microextraction by packed sorbent optimised by experimental design. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 5910–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, P.; Alves, G.; Rodrigues, M.; Llerena, A.; Falcão, A. First MEPS/HPLC assay for the simultaneous determination of venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine in human plasma. Bioanalysis 2014, 6, 3025–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Alves, G.; Rocha, M.; Queiroz, J.; Falcão, A. First liquid chromatographic method for the simultaneous determination of amiodarone and desethylamiodarone in human plasma using microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) as sample preparation procedure. J. Chromatogr. B 2013, 913–914, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szultka-Mlynska, M.; Buszewski, B. Electrochemical Oxidation of Selected Immunosuppressants and Identification of Their Oxidation Products by Means of Liquid Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry (EC-HPLC-MS/MS). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 176, 112799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.; Kamel, M.; El-Beqqali, A.; Abdel-Rehim, M. Microextraction by Packed Sorbent for LC–MS/MS Determination of Drugs in Whole Blood Samples. Bioanalysis 2010, 2, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świądro-Piętoń, M.; Dudek, D.; Wietecha-Posłuszny, R. Direct Immersion–Solid Phase Microextraction for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Patients with Mood Disorders. Molecules 2024, 29, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambonin, C.; Aresta, A. Recent Applications of Solid Phase Microextraction Coupled to Liquid Chromatography. Separations 2021, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.D.; Oliveira, I.G.C.; Queiroz, M.E.C. Innovative Extraction Materials for Fiber-in-Tube Solid Phase Microextraction: A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1165, 238110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazdrajić, E.; Tascon, M.; Rickert, D.A.; Gómez-Ríos, G.A.; Kulasingam, V.; Pawliszyn, J.B. Rapid Determination of Tacrolimus and Sirolimus in Whole Human Blood by Direct Coupling of Solid-Phase Microextraction to Mass Spectrometry via Microfluidic Open Interface. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1144, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.C.; de Araújo Lima, L.; Berlinck, D.Z.; Morau, M.V.; Junior, M.W.P.; Moriel, P.; Costa, J.L. Development and Application of Solid Phase Microextraction Tips (SPME LC Tips) Method for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Gefitinib by LC-MS/MS. Green Anal. Chem. 2024, 11, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.C.; Song, M.Y.; Zheng, T.L.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, J.L.; Zhang, Y.Z. Development of a Hollow Fiber Solid Phase Microextraction Method for the Analysis of Unbound Fraction of Imatinib and N-Desmethyl Imatinib in Human Plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 250, 116405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looby, N.T.; Tascon, M.; Acquaro, V.R.; Reyes-Garcés, N.; Vasiljevic, T.; Gomez-Rios, G.A.; Wasowicz, M.; Pawliszyn, J. Solid Phase Microextraction Coupled to Mass Spectrometry via a Microfluidic Open Interface for Rapid Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Analyst 2019, 144, 3721–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecco, C.F.; Miranda, L.F.C.; Queiroz, M.E. Costa. Aminopropyl Hybrid Silica Monolithic Capillary Containing Mesoporous SBA-15 Particles for In-Tube SPME-HILIC-MS/MS to Determine Levodopa, Carbidopa, Benserazide, Dopamine, and 3-O-Methyldopa in Plasma Samples. Microchem. J. 2020, 157, 105106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.S.; Nazdrajić, E.; Shimelis, O.I.; Ross, M.J.; Chen, Y.; Cramer, H.; Pawliszyn, J. Optimizing a High-Throughput Solid-Phase Microextraction System to Determine the Plasma Protein Binding of Drugs in Human Plasma. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 11061–11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looby, N.; Vasiljevic, T.; Reyes-Garcés, N.; Roszkowska, A.; Bojko, B.; Wąsowicz, M.; Jerath, A.; Pawliszyn, J. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Tranexamic Acid in Plasma and Urine of Renally Impaired Patients Using Solid Phase Microextraction. Talanta 2021, 225, 121945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Robles, A.; Solaz-García, Á.; Verdú-Andrés, J.; Andrés, J.L.P.; Cañada-Martínez, A.J.; Pericás, C.C.; Ponce-Rodriguez, H.D.; Vento, M.; González, P.S. The Association of Salivary Caffeine Levels with Serum Concentrations in Premature Infants with Apnea of Prematurity. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 4175–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, V.D.; de Lima Feltraco Lizot, L.; Hahn, R.Z.; Schneider, A.; Antunes, M.V.; Linden, R. Simple Determination of Valproic Acid Serum Concentrations Using BioSPME Followed by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometric Analysis. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2021, 1167, 122574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Huang, W.; Tong, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Lin, Z. In-Situ Growth of Covalent Organic Framework on Stainless Steel Needles as Solid-Phase Microextraction Probe Coupled with Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Rapid and Sensitive Determination of Tricyclic Antidepressants in Biosamples. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1695, 463955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojko, B.; Looby, N.; Olkowicz, M.; Roszkowska, A.; Kupcewicz, B.; Reck dos Santos, P.; Ramadan, K.; Keshavjee, S.; Waddell, T.K.; Gómez-Ríos, G.; et al. Solid Phase Microextraction Chemical Biopsy Tool for Monitoring of Doxorubicin Residue during In Vivo Lung Chemo-Perfusion. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021, 11, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.; Furton, K.G.; Tinari, N.; Grossi, L.; Innosa, D.; Macerola, D.; Tartaglia, A.; Di Donato, V.; D’Ovidio, C.; Locatelli, M. Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction–High Performance Liquid Chromatography–Photodiode Array Detection Method for Simultaneous Monitoring of Three Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment Drugs in Whole Blood, Plasma and Urine. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1084, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, M.; Furton, K.G.; Tartaglia, A.; Sperandio, E.; Ulusoy, H.İ.; Kabir, A. An FPSE-HPLC-PDA Method for Rapid Determination of Solar UV Filters in Human Whole Blood, Plasma and Urine. J. Chromatogr. B 2019, 1118–1119, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, P.; Parla, A.; Kabir, A.; Furton, K.G.; Gennimata, D.; Samanidou, V.; Panderi, I. Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography–Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Combined with Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Pioglitazone, Repaglinide, and Nateglinide in Human Plasma. J. Chromatogr. B 2023, 1217, 123628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazioglu, I.; Evrim Kepekci Tekkeli, S.; Tartaglia, A.; Aslan, C.; Locatelli, M.; Kabir, A. Simultaneous Determination of Febuxostat and Montelukast in Human Plasma Using Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Fluorimetric Detection. J. Chromatogr. B 2022, 1188, 123070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiris, G.; Gazioglu, I.; Furton, K.G.; Kabir, A.; Locatelli, M. Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction Combined with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography for the Determination of Favipiravir in Human Plasma and Breast Milk. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 223, 115131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, A.; Covone, S.; Rosato, E.; Bonelli, M.; Savini, F.; Furton, K.G.; Gazioglu, I.; D’Ovidio, C.; Kabir, A.; Locatelli, M. Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction (FPSE) as an Efficient Sample Preparation Platform for the Extraction of Antidepressant Drugs from Biological Fluids. Adv. Sample Prep. 2022, 3, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgun, E.; Ulusoy, H.İ.; Narin, İ.; Kabir, A.; Locatelli, M. Separation and Enrichment of Fingolimod and Citalopram Active Drug Ingredients by Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction Followed by High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Analysis with Diode Array Detection. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2025, 1264, 124730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, R.V.; Yunivita, V.; Santoso, P.; Hasanah, A.N.; Aarnoutse, R.E.; Ruslami, R. Analytical and Clinical Validation of Assays for Volumetric Absorptive Microsampling (VAMS) of Drugs in Different Blood Matrices: A Literature Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, S.; Taghvimi, A.; Mazouchi, N. Micro Solid Phase Extraction Using Novel Adsorbents. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 51, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.C.; Zhang, H.J.; Chen, J.B.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Liu, Y.W.; Yang, P.; Yuan, D.D.; Chen, D. A Green and Rapid Deep Eutectic Solvent Dispersed Liquid–Liquid Microextraction with Magnetic Particles-Assisted Retrieval Method: Proof-of-Concept for the Determination of Antidepressants in Biofluids. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 395, 123875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masenga, W.; Paganotti, G.M.; Seatla, K.; Gaseitsiwe, S.; Sichilongo, K. A Fast-Screening Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Method Applied to the Determination of Efavirenz in Human Plasma Samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 6401–6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, G.K.S.; Calixto, L.A.; Rocha, B.A.; Júnior, F.B.; de Oliveira, A.R.M.; de Gaitani, C.M. A Fast DLLME-LC-MS/MS Method for Risperidone and Its Metabolite 9-Hydroxyrisperidone Determination in Plasma Samples for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Patients. Microchem. J. 2020, 156, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghcheh, T.; Saber Tehrani, M.; Faraji, H.; Aberoomand Azar, P.; Helalizadeh, M. Analysis of Tamoxifen and Its Main Metabolites in Plasma Samples of Breast Cancer Survivor Female Athletes: Multivariate and Chemometric Optimization. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 1362–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gouveia, G.C.; dos Santos, B.P.; Sates, C.; Sebben, V.C.; Eller, S.; Arbo, M.D.; de Oliveira, T.F. A Simple Approach for Determination of Plasmatic Levels of Carbamazepine and Phenobarbital in Poisoning Cases Using DLLME and Liquid Chromatography. Toxicol. Anal. Clin. 2023, 35, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska, O.; Roszkowska, A.; Lipiński, M.; Treder, N.; Olędzka, I.; Kowalski, P.; Bączek, T.; Bień, E.; Krawczyk, M.A.; Plenis, A. Profiling Docetaxel in Plasma and Urine Samples from a Pediatric Cancer Patient Using Ultrasound-Assisted Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction Combined with LC–MS/MS. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlinarić, Z.; Turković, L.; Sertić, M. Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction Followed by Sweeping Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry for Determination of Six Breast Cancer Drugs in Human Plasma. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1718, 464698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kul, A.; Sagirli, O. A New Method for the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Chlorpromazine in Plasma by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Using Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction. Bioanalysis 2023, 15, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turković, L.; Koraj, N.; Mlinarić, Z.; Silovski, T.; Crnković, S.; Sertić, M. Optimisation of Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction for Plasma Sample Preparation in Bioanalysis of CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Therapeutic Combinations for Breast Cancer Treatment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treder, N.; Plenis, A.; Maliszewska, O.; Kaczmarczyk, N.; Olȩdzka, I.; Kowalski, P.; Bączek, T.; Bień, E.; Krawczyk, M.A.; Roszkowska, A. Monitoring of Sirolimus in the Whole Blood Samples from Pediatric Patients with Lymphatic Anomalies. Open Med. 2023, 18, 20230652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seip, K.F.; Gjelstad, A.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S. The Potential of Electromembrane Extraction for Bioanalytical Applications. Bioanalysis 2015, 7, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, R.R.; Gurrani, S.; Tsai, P.C.; Ponnusamy, V.K. Novel Salt-Assisted Liquid–Liquid Microextraction Technique for Environmental, Food, and Biological Samples Analysis Applications: A Review. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2022, 18, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, L.; Guo, Y.; You, J.; Shi, M.; Xi, Y.; Yin, L. High Throughput Analysis of Vancomycin in Human Plasma by UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 258, 116729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badillo-Ramírez, I.; Janssen, S.A.J.; Soufi, G.; Slipets, R.; Zór, K.; Boisen, A. Label-Free SERS Assay Combined with Multivariate Spectral Data Analysis for Lamotrigine Quantification in Human Serum. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.C.; Miranda, L.F.C.; Queiroz, M.E.C. Pipette Tip Micro–Solid Phase Extraction (Octyl-Functionalized Hybrid Silica Monolith) and Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry to Determine Cannabidiol and Tetrahydrocannabinol in Plasma Samples. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 1621–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Deng, B.; Feng, R.; Chen, D.; Hua, L. Rapid, Green and Semi-Automated PT-μSPE for Antidepressants Analysis in Urine and Plasma Using Melt-Blown Polypropylene from Disposable Face Masks as Sorbent. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 43, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Dong, L.; Zou, B.; Jin, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.; Xu, Y.; Fan, Y.; et al. Rapid On-Site Detection of Illicit Drugs in Urine Using C18 Pipette-Tip Based Solid-Phase Extraction Coupled with a Miniaturized Mass Spectrometer. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1738, 465485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, N.C.; Cabrices, O.G.; De Martinis, B.S. Innovative Disposable Pipette Extraction for Concurrent Analysis of Fourteen Psychoactive Substances in Drug Users’ Sweat. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1730, 465136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourvali Abarbakouh, M.; Faraji, H.; Shahbaazi, H.; Miralinaghi, M. (Deep Eutectic Solvent–Ionic Liquid)-Based Ferrofluid: A New Class of Magnetic Colloids for Determination of Tamoxifen and Its Metabolites in Human Plasma Samples. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treder, N.; Szuszczewicz, N.; Roszkowska, A.; Olędzka, I.; Bączek, T.; Bień, E.; Krawczyk, M.A.; Plenis, A. Magnetic Solid-Phase Microextraction Protocol Based on Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide-Functionalized Nanoparticles for the Quantification of Epirubicin in Biological Matrices. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimbelmann, F.; Groll, A.H.; Hempel, G. Determination of Fluconazole in Children in Small Blood Volumes Using Volumetric Absorptive Microsampling (VAMS) and Isocratic High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Ultraviolet (HPLC–UV) Detection. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocur, A.; Czajkowska, A.; Rębis, K.; Rubik, J.; Moczulski, M.; Kot, B.; Sierakowski, M.; Pawiński, T. Personalization of Pharmacotherapy with Sirolimus Based on Volumetric Absorptive Microsampling (VAMS) in Pediatric Renal Transplant Recipients—From LC-MS/MS Method Validation to Clinical Application. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 76, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasca, C.; Protti, M.; Mandrioli, R.; Atti, A.R.; Armirotti, A.; Cavalli, A.; De Ronchi, D.; Mercolini, L. Whole Blood and Oral Fluid Microsampling for the Monitoring of Patients under Treatment with Antidepressant Drugs. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 188, 113384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, A.; Sagirli, O. A Novel Method for the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Biperiden in Plasma by GC-MS Using Salt-Assisted Liquid–Liquid Microextraction. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 543, 117322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, A.; Al, S.; Dincel, D.; Sagirli, O. Simultaneous Determination of Buspirone, Alprazolam, Clonazepam, Diazepam, and Lorazepam by LC-MS/MS: Evaluation of Greenness Using AGREE Tool. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2025, 39, e70155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, B.; He, M.; Hu, B. Hierarchically Porous Covalent Organic Framework Doped Monolithic Column for On-Line Chip-Based Array Microextraction of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Microlitre Volume of Blood. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1331, 343332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langille, E.; Bottaro, C.S. Development and Application of a Thin-Film Molecularly Imprinted Polymer for the Measurement of Mycophenolic Acid in Human Plasma. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2023, 37, e24864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, H.; Matin, A.A.; Mohammadnejad, M. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Treated 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid Film: Application in Thin Film Solid Phase Microextraction of Anticancer Drugs. Talanta 2024, 266, 125064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarski, R.; Żuchowska, K.; Filipiak, W. Quantitative Determination of Unbound Piperacillin and Imipenem in Biological Material from Critically Ill Patients Using Thin-Film Microextraction–Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2022, 27, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfinejad, B.; Khoubnasabjafari, M.; Ziaei, S.E.; Ozkan, S.A.; Jouyban, A. Electromembrane Extraction as a New Approach for Determination of Free Concentration of Phenytoin in Plasma Using Capillary Electrophoresis. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 28, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isabella Cestaro, B.; Cavalcanti Machado, K.; Batista, M.; José Gonçalves da Silva, B. Hollow-Fiber Liquid Phase Microextraction for Determination of Fluoxetine in Human Serum by Nano-Liquid Chromatography Coupled to High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2024, 1234, 124018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Gao, X.; Guo, H.; Chen, W. Determination of 13 Antidepressants in Blood by UPLC-MS/MS with Supported Liquid Extraction Pretreatment. J. Chromatogr. B 2021, 1171, 122608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, C.P.; Dal Piaz, L.P.P.; Gerbase, F.E.; Müller, V.V.; Dal Piaz, L.P.P.; Antunes, M.V.; Linden, R. Simple Extraction of Toxicologically Relevant Psychotropic Compounds and Metabolites from Whole Blood Using Mini-QuEChERS Followed by UPLC–MS/MS Analysis. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2021, 35, e5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target Drug(s) | Matrix | Type of Paper | Analytical Technique | LOD (ng/mL) | LLOQ/ LOQ (ng/mL) | Linearity (ng/mL) | Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenytoin Lamotrigine Levetiracetam Topiramate Carbamazepine Oxcarbazepine 10,11-dihydro-10-hydroxy carbamazepine | Blood Plasma | Whatman 903® cards Noviplex® plasma prep cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.25 0.25 0.50 µg/mL | 0.50–50 0.50–50 0.50–50 0.50–50 0.25–50 0.25–50 0.50–50 µg/mL | Applied to clinical samples from patients under antiepileptic drug therapy. | [26] |

| Remifentanil | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.30 | 0.30–40 | Sensitive method for monitoring remifentanil in neonates via non-invasive umbilical cord blood sampling to support efficacy and safety trials. | [27] |

| Methotrexate | Plasma | Noviplex® plasma prep cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 30.00 | 30–2000 | Quantification of methotrexate in plasma for potential TDM application. | [41] |

| Meropenem | Plasma | Noviplex® plasma prep cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.50 µg/mL | 0.50–50 µg/mL | DPS method developed for routine TDM of meropenem in clinical laboratory settings. | [42] |

| Tacrolimus | Blood | hemaPEN® device | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 1.00 | 1.00–100 | Adapted for simplified and faster TDM of tacrolimus in transplant patients. | [44] |

| Vigabatrin Levetiracetam Pregabalin Gabapentin Lamotrigine Lacosamide Zonisamide Rufinamide Topiramate Oxcarbazepine Carbamazepine | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | 0.9 0.3 1.4 4.6 1.00 1.4 8.1 0.76 1.00 0.75 0.46 | 4.80 0.90 4.50 13.90 3.00 4.40 25.00 2.30 4.50 2.30 1.40 | 5–25,000 1–25,000 5–25,000 14–10,000 3–10,000 5–10,000 25–25,000 2.3–25,000 4.5–10,000 2.3–25,000 1.4–25,000 | Demonstrated to be a promising and advanced method for TDM of antiepileptic drugs. | [45] |

| Abiraterone delta(4)-abiraterone | Blood | Whatman 903® paper cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | LLOQ: 1 LLOQ: 0.2 | 1–320 0.2–16 | Quantification of Abiraterone and delta(4)-abiraterone in DBS and evaluation of its clinical applicability in patients treated with abiraterone acetate. | [46] |

| Carbamazepine Lacosamide Lamotrigine Levetiracetam Valproic acid | Blood | Capitainer® | UHPLC-MS/MS | 0.38 0.48 0.46 0.94 9.67 | 0.50 0.60 0.60 1.20 120 | n.r | Clinically validated using samples from patients with epilepsy. | [47] |

| Olanzapine Clozapine N-desmethyl clozapine Quetiapine Norquetiapine Aripiprazole Dehydro aripiprazole Chlorpromazine Risperidone 9-hydroxyrisperidone Ziprasidone Perhenazine Fluphenazine Haloperidol Perospirone Amisulpride Sulpiride Memantine Donepezil | Blood | AutoCollect™ DBS cards | LC-MS/MS | 0.33 0.71 0.34 0.05 0.04 0.38 0.46 0.16 0.04 0.06 0.25 0.03 0.06 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.19 0.03 0.08 | 1.11 2.38 1.14 0.17 0.14 1.27 1.53 0.54 0.14 0.22 0.85 0.11 0.20 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.63 0.11 0.27 | 4–200 40–2000 20–1000 40–2000 20–1000 40–2000 20–1000 16–800 5–250 5–250 16–800 0.2–10 0.6–30 0.6–30 0.6–30 24–1200 40–2000 12–600 4–200 | Applied in a fully automated DBS–Online SPE–LC–MS/MS system for the therapeutic drug monitoring of antipsychotic drugs. | [48] |

| Imatinib Norimatinib | Blood | Ahlstrom 222 discs sheets Capitainer® B device. Whatman 903® cards HemaXis® DB10 device | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 240.00 48.00 | 240–6000 48–1200 | Successfully applied to clinical TDM samples using the DMS approach. Supports the use of both devices as practical alternatives for TDM in patients undergoing IMA-based cancer therapy. | [49] |

| Isavuconazole | Blood | QIAcard FTP DMPK-C cards | HPLC-FLD | n.r | 0.10 µg/mL | 0.10–20 µg/mL | Demonstrated the viability of DBS as a matrix for TDM of isavuconazole in patients treated with Cresemba®. | [50] |

| Imipenem Meropenem Tigecycline Teclopidine Vancomycin | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.25 0.20 0.016 0.65 0.40 µg/mL | 0.25–25 0.2–20 16–1600 0.65–65 0.4–40 µg/mL | Validated as a tool for guiding individualised antimicrobial therapy in ICU patients, suggesting DBS as a complement or alternative to traditional methods. | [51] |

| Procainamide Lidocaine Quinidine Deslanoside Digoxin Atorvastatin Digitoxin Amiodarone | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | 100.00 50.00 100.00 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.50 100.00 | 500.00 250.00 500.00 0.50 0.50 0.50 1.00 250.00 | 500–8000 500–5000 2000–6000 0.8–2.4 0.5–2 3–150 10–30 1500–2500 | Provides a valuable tool for monitoring cardiovascular therapy in multi-dose regimens. | [52] |

| Bedaquiline N-Desmethylbedaquiline Linezolid Levofloxacin Clofazimine | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.0181 0.00905 0.113 0.0741 0.00814 µg/mL | 0.0181–4.94 0.00905–2.47 0.113–30.9 0.0741–20.2 0.00814–2.22 µg/mL | Proposed as a suitable alternative to traditional methods for TDM in remote or resource-limited settings. | [53] |

| Letrozole Palbociclib Ribociclib Abemaciclib M2 M20 | Blood | HemaXis® DB10 device | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 6.00 6.00 120.00 40.00 20.00 20.00 | 6–300 6–300 120–6000 40–800 20–400 20–400 | Offers a reliable approach for TDM implementation in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, with potential benefits for adherence and outcomes. | [54] |

| Cabotegravir Rilpivirine | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 25.00 2.00 | 25–20,000 2–2500 | Applied to quantify analytes from DBS collected during a clinical trial, including post hoc evaluation of paired samples. | [55] |

| Rifampicin Ethambutol Isoniazid Pyrazinamide | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | UHPLC-MS/MS | 0.035 0.021 0.118 0.639 µg/mL | 0.42 0.36 0.36 1.98 µg/mL | 0.37–24 0.37–24 0.37–24 2.03–130 µg/mL | Demonstrated clinical applicability of bioanalytical methods for TDM purposes. | [56] |

| Meropenem | Blood | FTA DMPK-B cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.30 µg/mL | 0.3–80 µg/mL | Proposed as an alternative strategy for meropenem TDM in preterm neonates, offering adequate performance and logistical benefits. | [57] |

| Polymyxin B1 Polymyxin B2 | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.10 0.0340 µg/mL | 0.1–10 0.0110–1.10 µg/mL | Successfully applied in clinical TDM of polymyxin B, representing a feasible alternative for hospital use. | [58] |

| Clozapine Norclozapine | Plasma Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 50.00 | 50–1500 | Applied to evaluate clozapine therapy in a cohort of schizophrenic patients. | [59] |

| Bortezomib | Blood | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.20 | 0.2–20 | Shows potential for future TDM and pharmacokinetic studies of bortezomib, particularly in paediatric populations. | [60] |

| Lamotrigine | Blood Oral Fluid | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | Blood: 0.01 OF: 0.02 µg/mL | Blood: 1.00 OF:0.50 µg/mL | Blood: 1–30 OF: 0.5–20 µg/mL | Developed to establish a robust protocol for TDM using alternative matrices such as DBS and oral fluid, promoting less invasive sampling. | [61] |

| Bictegravir | Plasma | Whatman filter paper | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 20.00 | 20–1200 | Successfully applied in routine pharmaceutical and industrial studies for sample collection and pharmacokinetic analysis. | [62] |

| Apixaban | Plasma | n.r | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 31.25 | 31.25–500 | Developed to facilitate apixaban TDM, enabling accessibility in peripheral hospitals via DPS shipment. | [63] |

| Osimertinib AZ5104 AZ7550 | Plasma | HemaPEN® device | UHPLC-MS/MS | n.r | 1.00 | 1–729 | Useful for managing drug-related toxicity and supporting pharmacokinetic studies in clinical settings. | [64] |

| Voriconazole Posaconazole Isavuconazole | Plasma | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.065 0.22 0.22 µg/mL | 0.37–7.74 0.24–496 0.51–20.40 µg/mL | Demonstrated the suitability of DPS for routine TDM of voriconazole and isavuconazole. | [65] |

| Aciclovir Ganciclovir | Plasma | n.r | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.013 µg/mL | 0.013–20 µg/mL | Adapted for TDM application of antiviral drugs, facilitating dose-concentration assessments, particularly in paediatric patients. | [66] |

| Fluconazole Posaconazole Itraconazole Hydroxyitraconazole Voriconazole | Plasma | DBS (Whatman grade 31ET chromatography paper) | PS-MS/MS | n.r | 0.50 0.10 0.10 0.10 µg/mL | 0.5–50 0.1–10 0.1–10 0.1–10 µg/mL | Simultaneous quantitation of five triazole antifungal agents in plasma. The method represents a powerful tool for near-point-of-care TDM, with the potential to improve patient care by reducing turnaround time and supporting clinical research applications. | [67] |

| Amikacin | Serum | Whatman 903® cards | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.50 µg/mL | 0.5–100 µg/mL | DMS method has been successfully applied in TDM samples | [68] |

| Target Drug(s) | Matrix | Type of Sorbent | Analytical technique | LOD (ng/mL) | LLOQ/LOQ (ng/mL) | Linearity (ng/mL) | Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haloperidol Olanzapine Clonazepam Mirtazapine Paroxetine Citalopram Sertraline Chlorpromazine Imipramine Clomipramine Quetiapine Diazepam Fluoxetine Clozapine Carbamazepine Lamotrigine | Plasma | Organic–inorganic hybrid silica monolith | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.05 0.05 0.10 0.05 0.05 1.00 0.05 0.10 0.05 0.10 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.10 1.00 | 0.5–40.5 0.5–40.5 5–155 5–155 5–155 5–325 5–325 10–290 10–290 10–510 10–410 50–850 50–850 50–1550 500–10,500 500–10,500 | Used for the quantification of antipsychotic drugs in plasma from schizophrenic patients. | [71] |

| Nordoxepin Doxepin Desipramine Nortriptyline Imipramine Amitriptyline | Oral fluid | M1 | UHPLC-MS | 0.04 0.01 0.04 0.01 0.03 0.02 | 0.13 0.03 0.14 0.03 0.09 0.08 | 2.0–10.0 | Useful tool in clinical and forensic laboratories to quantify TCADs and their metabolites at therapeutic levels. | [72] |

| Epinephrine Norepinephrine Dopamine Metanephrine Normetanephrine 3-Methoxytyramine | Urine | C18 | LC-MS/MS | 0.08 0.30 0.530 0.176 0.440 0.176 | 0.167 0.650 1.53 0.440 1.10 0.880 | 0.167–33.4 0.650–130 1.53–306 1.34–268 3.43–686 1.33–265 | Used in routine clinical laboratories for the screening of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL). | [73] |

| Morphine 6-MAM Cocaine Cocaethylene Benzoylecgonine Methadone EDDP MDPV Mephedrone Methylone Buprenorphine Naloxone Pentedrone Butylone Ethylcathinone Ethylcathinone ephedrine Methylephedrine Pyrovalerone Flephedrone Scopolamine | Oral fluid | M1 | UHPLC-MS/MS | 2.50 1.00 0.25 0.25 0.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 1.00 | 10.00 2.50 0.50 0.50 1.00 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 1.00 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 0.50 2.50 | LOQ—250 | Applied to patients under substitution therapy programmes and for drug monitoring in traffic safety contexts. | [74] |

| Chlorpromazine Clozapine Olanzapine Quetiapine | Plasma | RACNT | UHPLC-MS/MS | n.r | 10.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 | 10–700 10–700 10–200 10–700 | Applied to the therapeutic drug monitoring of antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia. | [76] |

| Ziprasidone | Plasma | C2 | HPLC-UV | 0.30 | 1.00 | 1–500 | Applied to the therapeutic drug monitoring of psychiatric patients treated with ziprasidone. | [77] |

| Zonisamide | Plasma | C18 | HPLC-DAD | n.r | 0.20 µg/mL | 0.2–80 µg/mL | Applied to plasma samples from epilepsy patients treated with zonisamide to support therapeutic drug monitoring. | [78] |

| Venlafaxine O-desmethylvenlafaxine | Plasma | C18 | UHPLC-FLD | 2.00 5.00 | 10.00 20.00 | 10–1000 20–1000 | Developed for therapeutic drug monitoring and to support pharmacokinetic studies in humans. | [79] |

| Amiodarone Desethylamiodarone | Plasma | C18 | HPLC-DAD | 0.02 µg/mL | 0.10 µg/mL | 0.1–10 µg/mL | Used in patients treated with amiodarone to support TDM and pharmacokinetic studies, such as bioavailability and bioequivalence. | [80] |

| Cyclosporine A Everolimus Mycophenolic acid Sirolimus Tacrolimus | Serum | C18 | EC-LC-MS/MS | 0.021 0.023 0.027 0.029 0.031 | 0.063 0.068 0.092 0.098 0.113 | 1–50 | Applied to study the generation of metabolites from selected immunosuppressive drugs. | [81] |

| Lidocaine Ropivacaine Bupivacaine | Blood | C18 | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 10.00 nmol/L | 10–10,000 nmol/L | Used for the therapeutic drug monitoring of target analytes in whole blood. | [82] |

| Target Drug(s) | Matrix | Type of Fiber | Analytical Technique | LOD (ng/mL) | LLOQ/LOQ (ng/mL) | Linearity (ng/mL) | Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline Aripiprazole Carbamazepine Citalopram Clomipramine Desipramine Flunitrazepam Fluoxetine Fluvoxamine Imipramine Ketamine Paroxetine Sertraline Trazodone Duloxetine Mirtazapine Nortriptyline Venlafaxine Lamotrigine Quetiapine Olanzapine | Blood | C-18 SPME-LC silica | LC-TOF-MS | 0.18 n.r n.r 0.97 n.r n.r n.r 0.46 n.r n.r n.r 0.52 1.69 0.54 4.29 0.14 n.r 0.58 0.37 0.92 1.52 | 0.92 n.r n.r 4.87 n.r n.r n.r 2.32 n.r n.r n.r 2.60 8.43 2.69 21.47 0.70 n.r 2.91 5.73 54.58 7.62 | LLOQ—300 | DI-SPME applied to 38 blood samples from patients with mood disorders; enabled rapid screening of drug concentrations within therapeutic and toxic dose ranges. | [83] |

| Tacrolimus Sirolimus Everolimus Cyclosporine A | Blood | Bio-SPME fibers coated with HLB particles | MOI-MS/MS | 0.3 0.2 0.3 0.3 | 0.80 0.70 1.00 0.80 | 1–50 1–50 1–50 2.5–500 | Applied for the determination of immunosuppressive drug levels in whole blood samples. | [86] |

| Gefitinib O-desmethyl-gefitinib | Plasma | SPMELC C18 tips | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 20.00 20.00 | 20–800 | Applied for proof-of-concept analysis of plasma samples from individuals receiving gefitinib treatment. | [87] |

| Imatinib N-desmethylimatinib | Plasma | hollow fiber (polysulfone, polyvinyl chloride, polyacrylonitrile) | LC-MS/MS | 0.50 1.00 | 2.50 2.50 | 2.5–250 | Successfully implemented in clinical TDM for imatinib and norimatinib; both total and unbound concentrations were evaluated in clinical samples. | [88] |

| Tranexamic acid | Plasma | Nitinol coated with HLB particles | MOI-MS/MS | n.r | 25.00 µg/mL | 25–2000 µg/mL | Enabled near real-time monitoring of tranexamic acid concentrations in plasma during surgical procedures. | [89] |

| Levodopa Carbidopa Benserazide Dopamine 3-O-methyldopa | Plasma | aminopropyl hybrid silica monolith containing SBA-15 | HILIC-MS/MS | n.r | 22.00 33.00 170.00 1.20 10.00 | 22–2000 33–2000 170–2000 1.2–2000 10–2000 | Applied to plasma samples from patients with Parkinson’s disease for routine TDM. | [90] |

| Atenolol Morphine Acetaminophen Lorazepam Carbamazepine Diazepam Buprenorphine | Plasma | BioSPME (C18-bonded silica particles in combination with biocompatible polyacrylonitrile (PAN) polymeric adhesive) | LC-MS/MS | n.r | n.r | n.r | Used in high-throughput platforms to determine free plasma concentrations and protein binding of drugs with diverse physicochemical profiles. | [91] |

| Tranexamic acid | Urine Plasma | PAN and HLB particles | LC-MS/MS | n.r | Urine: 25.00 Plasma: 10.00 µg/mL | Urine: 25–1000 µg/mL Plasma: 10–1000 µg/mL | Developed an improved SPME-based sampling protocol for TDM of tranexamic acid in plasma and urine from patients with chronic renal dysfunction, aiming to optimise dosing regimens. | [92] |

| Caffeine | Serum Oral Fluid | ZB-FFAP, with 100% nitroterephthalic modified polyethylene glycol | HPLC-DAD | n.r | n.r | n.r | Enabled OF-based quantification of caffeine in preterm infants; showed strong correlation with serum levels during treatment for apnoea of prematurity. | [93] |

| Valproic acid | Serum | BioSPME (LC Tips C18) | GC-MS | n.r | 10.00 µg/mL | 10–150 µg/mL | Developed and validated a GC–MS assay using BioSPME for the quantification of valproic acid in serum, supporting routine TDM applications. | [94] |

| Amitriptyline Doxepin Nortriptyline | Serum Liver Kidney Brain | COF | ESI-MS | 0.10 0.50 0.10 | 0.30 1.50 0.30 | 0.8–100 1.0–100 0.8–100 | Demonstrated as a powerful analytical tool for therapeutic drug monitoring in clinical settings. | [95] |

| Doxorubicin Doxorubicinol Doxorubicinone Doxorubicinolone | Lung | BioSPME (mixed-mode fibres with C8+benzenesulfonic acid particle) | LC-MS/MS | n.r | n.r | 10–1000 1–100 1–100 1–100 µg/mL | Enabled simultaneous monitoring of drug levels and biodistribution in lung tissue alongside relevant metabolites, providing insights into drug activity and therapeutic optimisation. | [96] |

| Target Drug(s) | Matrix | Type of Membrane | Analytical Technique | LOD (ng/mL) | LLOQ/LOQ (ng/mL) | Linearity (ng/mL) | Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin Sulfasalazine Cortisone | Blood Plasma Urine | sol–gel Carbowax® 20 M | HPLC-DAD | Blood: 0.02 Plasma: 0.10 Urine: 0.03 µg/mL | Blood: 0.05 Plasma: 0.25 Urine: 0.10 µg/mL | Blood:0.05–10 Plasma: 0.25–10 Urine: 0.10–10 µg/mL | Quantification of therapeutic agents used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. | [97] |

| BP-4 4-DHB DHMB BP-1 BP-2 benzophenone | Blood Plasma Urine | sol–gel Carbowax® 20 M coating on cellulose | HPLC-PDA | 0.03 µg/mL | 0.10 µg/mL | 0.1–10 µg/mL | Demonstrates utility as a valuable tool for assessing bioaccumulation in humans. | [98] |

| Pioglitazone Repaglinide Nateglinide | Plasma | sol–gel Carbowax® 20 M with cellulose | HILIC-MS | 7.00 2.00 30.00 | 25.00 6.00 125.00 | 25–200 6.25–500 125–10,000 | Bioanalytical method for monitoring the therapeutic levels of antidiabetic drugs. | [99] |

| Febuxostat Montelukast | Plasma | sol–gel PCAP-PDMS-PCAP | HPLC-FLD | 0.10 1.50 | 0.30 5.00 | 0.3–10 5–100 | Evaluation of the pharmacokinetic profiles of febuxostat and montelukast in human plasma. | [100] |

| Favipiravir | Plasma Breast milk | sol–gel PCAP-PDMS-PCAP | HPLC-UV | Plasma: 0.06 Breast milk: 0.15 µg/mL | Plasma: 0.20 Breast milk: 0.50 µg/mL | Plasma: 0.2–50 Breast milk: 0.5–25 µg/mL | Quantification of favipiravir in plasma and breast milk to assess exposure and safety, particularly in the context of limited data in infants. | [101] |

| Venlafaxine Citalopram Paroxetine Fluoxetine Sertraline Amitriptyline Clomipramine | Blood Urine Oral fluid | sol–gel Carbowax® 20 M coated with cellulose | HPLC-PDA | 0.06 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 mg/mL | 0.20 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 0.10 mg/mL | 0.2–20 0.1–20 0.1–20 0.1–20 0.1–20 0.1–20 0.1–20 mg/mL | Method developed to optimise pharmacotherapy and enable TDM. | [102] |

| Fingolimod Citalopram | Artificial oral fluid; Artificial urine | Sol–Gel-PCAP-PDMS-PCAP | HPLC-DAD | 7.46 5.97 | 24.38 19.78 | 25–1000 20–1000 | Determination of two drugs commonly prescribed for the management of multiple sclerosis. | [103] |

| Target Drug(s) | Matrix | Type of Solvents | Analytical Technique | LOD (ng/mL) | LLOQ/LOQ (ng/mL) | Linearity (ng/mL) | Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline hydrochloride Imipramine hydrochloride Sertraline hydrochloride Fluoxetine hydrochloride | Plasma Urine | DES-DDLME-MPAR (Methyltrioctylammonium bromide: capryl alcohol (1:3, v/v) | HPLC-UV | 0.027 0.028 0.025 0.020 µg/mL | 0.075 0.092 0.080 0.068 µg/mL | 0.1–10 µg/mL | Enabled the simultaneous quantification of selected antidepressants in plasma and urine, supporting pharmacotherapy control and drug toxicity prevention. | [106] |

| Efavirenz | Plasma | DLLME (acetonitrile: chloroform) | GC-MS | 0.008 µg/mL | 0.027 µg/mL | 0.10–2.0 µg/mL | Applied to human plasma samples from patients undergoing treatment with efavirenz. | [107] |

| Risperidone 9-hydroxyrisperidone | Plasma | DLLME (chlorobenzene: acetone) | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 5.00 | 5.0–80 | Successfully used in plasma analysis of a schizophrenic patient under therapy. | [108] |

| Tamoxifen N-desmethyltamoxifen 4-hydroxytamoxifen Endoxifen | Plasma | DLLME (DES: thymol-nonanoic acid) | HPLC-DAD | 1.70 3.20 0.30 0.70 | 5.00 10.00 0.80 2.00 | 5–300 10–500 0.8–25 2–50 | Effective for pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and therapeutic drug monitoring studies of tamoxifen and its main metabolites in biological fluids. | [109] |

| Carbamazepine Phenobarbital | Plasma | DLLME (n.r) | HPLC-UV | n.r | 2.00 10.00 µg/mL | n.r | Demonstrates clinical value of plasma-level monitoring for optimising treatment selection and staging intoxication cases. | [110] |

| Docetaxel | Plasma Urine | UA-DLLME (chloroform: ethanol) | LC-MS/MS | Plasma: 1.00 Urine: 2.50 µg/mL | Plasma: 2.50 Urine: 5.00~ µg/mL | Plasma: 2.5–2000 Urine: 5–2000 µg/mL | Contributed to improved oncological strategies, particularly in paediatric oncology units, by supporting individualised TDM. | [111] |

| Letrozole Anastrozole Palbociclib Ribociclib Abemaciclib Fulvestrant | Plasma | DLLME (isopropanol, chloroform (1:2, v/v)) | MECK-MS/MS | n.r | 30.00 20.00 30.00 500.00 50.00 10.00 | 30–300 20–200 30–300 500–5000 50–500 10–100 | Applied to plasma samples from breast cancer patients; determined concentrations were consistent with clinical data, confirming its suitability for TDM. | [112] |

| Chlorpromazine | Plasma | DLLME (n.a) | GC-MS | n.r | 30.00 | 30–600 | Applied to plasma samples from real patients receiving clinical treatment. | [113] |

| Abemaciclib Palbociclib Ribociclib Anastrozole Letrozole Fulvestrant | Plasma | DLLME (isopropanol, chloroform) | HPLC-FLD HPLC-DAD | n.r | 0.11 0.08 0.25 2.51 0.04 0.50 µg/mL | 0.11–2.61 0.08–1.92 0.25–5.95 2.51–60.30 0.04–1.01 0.50–12.04 µg/mL | Successfully used for drug monitoring in breast cancer patient plasma samples. | [114] |

| Sirolimus | Blood | DLLME (ethanol: chloroform) | LC-MS/MS | 0.20 | 0.60 | 1–50 | Applied for the therapeutic drug monitoring of sirolimus in whole blood samples to assess its pharmacokinetic profile in paediatric patients with lymphatic anomalies at hourly intervals | [115] |

| Target Drug(s) | Matrix | Extraction | Analytical Technique | LOD (ng/mL) | LLOQ/LOQ (ng/mL) | Linearity (ng/mL) | Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | Plasma | µ-SPE (Oasis® MAX μElution Plate) | UHPLC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.50 | 0.50–100 | Successfully applied to the TDM of vancomycin in clinical samples. | [118] |

| Lamotrigine | Serum | µ-SPE (HLB) | SERS | 3.20 µM | 9.50 µM | 9.5–75 µM | Demonstrates high potential for automation in a compact device suitable for routine clinical settings, as an alternative analytical TDM method for lamotrigine. | [119] |

| Cannabidiol Tetrahydrocannabinol | Plasma | PT-µSPE (octyl-functionalized hybrid silica monolith) | UHPLC-MS/MS | n.r | 10.00 | 10–150 | Demonstrated to be suitable for the simultaneous quantification of cannabidiol and tetrahydrocannabinol in plasma for TDM in patients undergoing cannabinoid-based therapy. | [120] |

| Venlafaxine Citalopram Imipramine Amitriptyline Sertraline Fluoxetine | Urine; Plasma | PT-µSPE (melt-blown polypropylene nonwoven material) | HPLC-UV | 5.70 5.50 4.20 4.20 3.10 3.00 | 19.10 18.30 14.30 14.10 10.30 10.00 | 20–200 | Offers a practical, scalable, and environmentally friendly approach for therapeutic drug monitoring in clinical settings. | [121] |

| 6-MAM Methamphetamine MDMA Ketamine Norketamine Cocaine | Urine | PT-SPE (C18) | miniMS | 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.50 1.00 0.25 | 5.00 5.00 5.00 1.00 5.00 1.00 | 5–250 5–250 5–250 1–250 5–250 1–250 | Enables rapid on-site detection with improved portability and lower cost, supporting its potential use in forensic analysis and drug crime investigation. | [122] |

| Amphetamine Methamphetamine MDMA MDA MDEA Cocaine Cocaethylene AEME Dibutylone N-ethylpentylone 25E-NBOMe 25C-NBOMe 2C-E 2C-C Fentanyl Carfentanil | Sweat | DPX (SCX) | GC-MS | 1.00 2.00 1.00 1.00 3.00 5.00 5.00 5.00 1.00 1.00 5.00 3.00 15.00 15.00 3.00 3.00 | 2.00 3.00 2.00 2.00 5.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 2.00 2.00 10.00 5.00 30.00 30.00 5.00 5.00 | LOQ—1100 | Demonstrated the utility of sweat as a versatile biofluid for toxicological and forensic applications across clinical, occupational, and legal settings. | [123] |

| Tamoxifen N-desmethyltamoxifen 4-hydroxytamoxifenendoxifen | Plasma | dSPE (Fe3O4@SiO2) | HPLC-DAD | 1.50 1.90 0.10 0.30 | 5.00 5.00 0.20 1.00 | 5–100 5–200 0.2–25 1–50 | Enabled TDM and pharmacodynamic assessment of tamoxifen and metabolites in biological fluids, supporting clinical drug research and therapeutic individualisation. | [124] |

| Epirubicin | Plasma Urine | m-µSPE (Fe3O4-based nanoparticles coated with silica and a double-chain surfactant—namely, didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB)) | LC-FLD | 0.50 µg/mL | 1.00 µg/mL | Plasma: 0.001–1 Urine: 0.001–10 µg/mL | Validated for routine monitoring in clinical practice, enhancing precision medicine approaches. | [125] |

| Fluconazole | Blood, plasma, serum | VAMS (Mitra® devices) | HPLC-UV | n.r | 5.00 µg/mL | 5–160 µg/mL | Validated for the monitoring of fluconazole exposure in immunocompromised paediatric patients, with potential applicability to pharmacokinetic studies. | [126] |

| Sirolimus | Blood | VAMS (Mitra™ device) | LC-MS/MS | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.25–60 | Implemented in routine clinical practice in paediatric transplant centres, particularly for renal transplant recipients, demonstrating its utility in real-world scenarios. | [127] |

| Sertraline Fluoxetine Citalopram Vortioxetine Norsertraline Norfluoxetine N-desmethylcitalopram N, N-didesmethylcitalopram | Blood Oral Fluid | VAMS (Mitra® device) | HPLC-UV-FLD | OF, Blood: 1.50; 2.50 2.50; 3.00 0.30; 0.30 1.00; 1.50 1.50; 2.50 2.50; 3.00 0.30; 0.30 0.30; 0.30 | OF, Blood: 5.00; 7.00 7.00; 10.00 1.00; 1.00 3.00; 5.00 5.00; 7.00 7.00; 10.00 1.00; 1.00 1.00;1.00 | LOQ—500 LOQ—750 LOQ—200 LOQ—500 LOQ—500 LOQ—750 LOQ—200 LOQ—200 | Demonstrates clinical applicability via VAMS-based TDM of antidepressants in blood and oral fluid from psychiatric patients. | [128] |

| Biperiden | Plasma | SALLME (sodium chloride) | GC-MS | n.r | 0.50 | 0.5–15 | Successfully applied to the therapeutic drug monitoring of biperiden in plasma samples from real patients | [129] |

| Buspirone Alprazolam Clonazepam Diazepam Lorazepam | Plasma | SALLME (zinc sulphate) | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 1.00 5.00 4.00 100.00 30.00 | 1–30 5–100 4–100 100–3000 30–300 | Demonstrated suitability for therapeutic drug monitoring through the determination of drug concentrations in real patient samples. | [130] |

| Ketoprofen Fenbufen Carprofen Diclofenac Ibuprofen | Serum | Chip-based capillary array | HPLC-UV | 4.39 8.06 5.40 7.96 15.5 | 20.00 20.00 20.00 20.00 50.00 | 20–1000 20–1000 20–1000 20–1000 50–1000 | Demonstrated potential for use in TDM, forensic toxicology, and clinical pharmacokinetic investigations. | [131] |

| Mycophenolic acid | Plasma | TFME (MIP) | UPLC-MS/MS | 0.30 | 1.00 | 5–250 | Demonstrated suitability for therapeutic drug monitoring applications. | [132] |

| Dasatinib Erlotinib | Plasma | TFME (PLA) | HPLC-DAD | 0.03 0.30 | 0.10 1.00 | 0.1–20 1–500 | Utilised for the quantification of anticancer drugs in human plasma; supports TDM due to the toxicity profile of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). | [133] |

| Piperacilin Imipenem | Blood | TFME (DVB) | LC-MS/MS | n.r | 0.02 0.05 µg/mL | 0.01–1 µg/mL | Provided a high-throughput analytical platform demonstrating low antibiotic bioavailability at infection sites, enabling personalised dosing strategies through future TDM studies. | [134] |

| Phenytoin | Plasma | EME (PP Q3/2 polypropylene hollow fiber) | CE-DAD | 0.005 µg/mL | 0.03 µg/mL | 0.03–4 µg/mL | Determination of free phenytoin concentration offers a viable alternative to conventional methods for therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacokinetic studies. | [135] |

| Fluoxetine | Serum | HF-LPME (polypropylene) | nanoLC-HRMS | n.r | 0.2 µg/mL | 0.2–2.5 µg/mL | Demonstrated potential for therapeutic drug monitoring using a lab-fabricated chromatographic nanocolumn. | [136] |

| Imipramine Desipramine Fluoxetine Norfluoxetine Paroxetine Maprotiline Sertraline Citalopram Clomipramine Trazodone Doxepin Clozapine Amitriptyline | Blood | SLE (Isolute SLE + cartridge) | UPLC-MS/MS | 0.03 0.0003 0.0003 0.003 0.003 0.0003 0.0003 0.0003 0.0003 0.0003 0.003 0.0003 0.0003 | 0.01 0.001 0.001 0.01 0.01 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.01 0.001 0.001 | 0.01–200 0.001–200 0.001–200 0.01–200 0.01–200 0.001–200 0.001–200 0.001–200 0.001–200 0.001–200 0.01–200 0.001–200 0.001–200 | Applied to real-case analysis of antidepressants, demonstrating potential for broad use in both biomedical and forensic contexts. | [137] |

| Amitriptyline Carbamazepine Citalopram Clomipramine Clonazepam Codeine Diazepam Flunitrazepam Fluoxetine Flurazepam Norfluoxetine Nortriptyline Paroxetine Sertraline Venlafaxine | Blood | mini-QuEchERS (magnesium sulphate, sodium chloride and sodium citrate dihydrate (4:1:1, w/w/w)) | UPLC-MS/MS | n.r | 25.00 | 25–1000 | Demonstrates capability for the determination of target psychotropic drugs and metabolites in forensic and clinical toxicology. | [138] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosendo, L.M.; Rosado, T.; Barroso, M.; Gallardo, E. Miniaturised Extraction Techniques in Personalised Medicine: Analytical Opportunities and Translational Perspectives. Molecules 2025, 30, 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214263

Rosendo LM, Rosado T, Barroso M, Gallardo E. Miniaturised Extraction Techniques in Personalised Medicine: Analytical Opportunities and Translational Perspectives. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214263

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosendo, Luana M., Tiago Rosado, Mário Barroso, and Eugenia Gallardo. 2025. "Miniaturised Extraction Techniques in Personalised Medicine: Analytical Opportunities and Translational Perspectives" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214263

APA StyleRosendo, L. M., Rosado, T., Barroso, M., & Gallardo, E. (2025). Miniaturised Extraction Techniques in Personalised Medicine: Analytical Opportunities and Translational Perspectives. Molecules, 30(21), 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214263