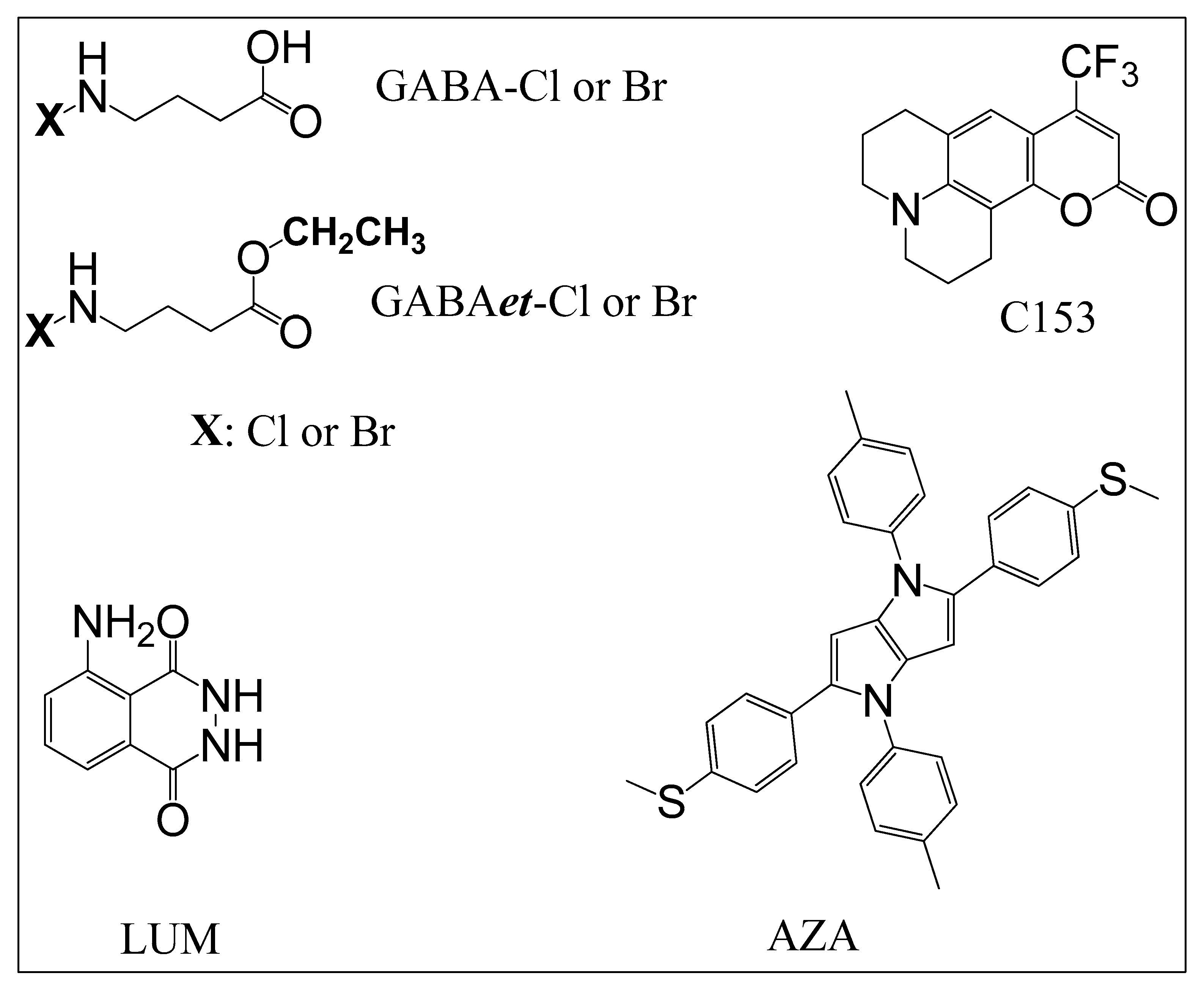

Haloamines of the Neurotransmitter γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Its Ethyl Ester: Mild Oxidants for Reactions in Hydrophobic Microenvironments and Bactericidal Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation and Stability of Solutions of Haloamines

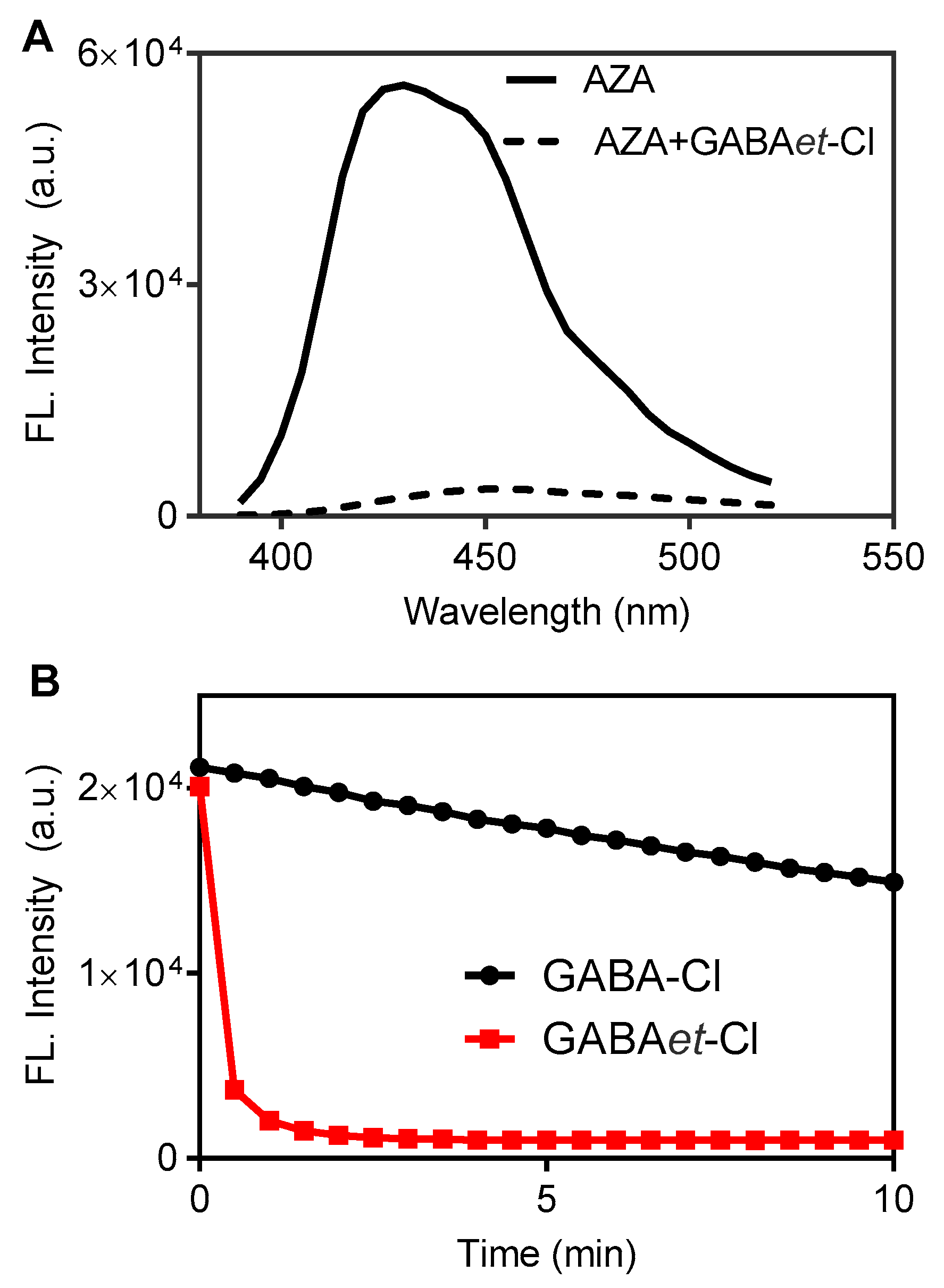

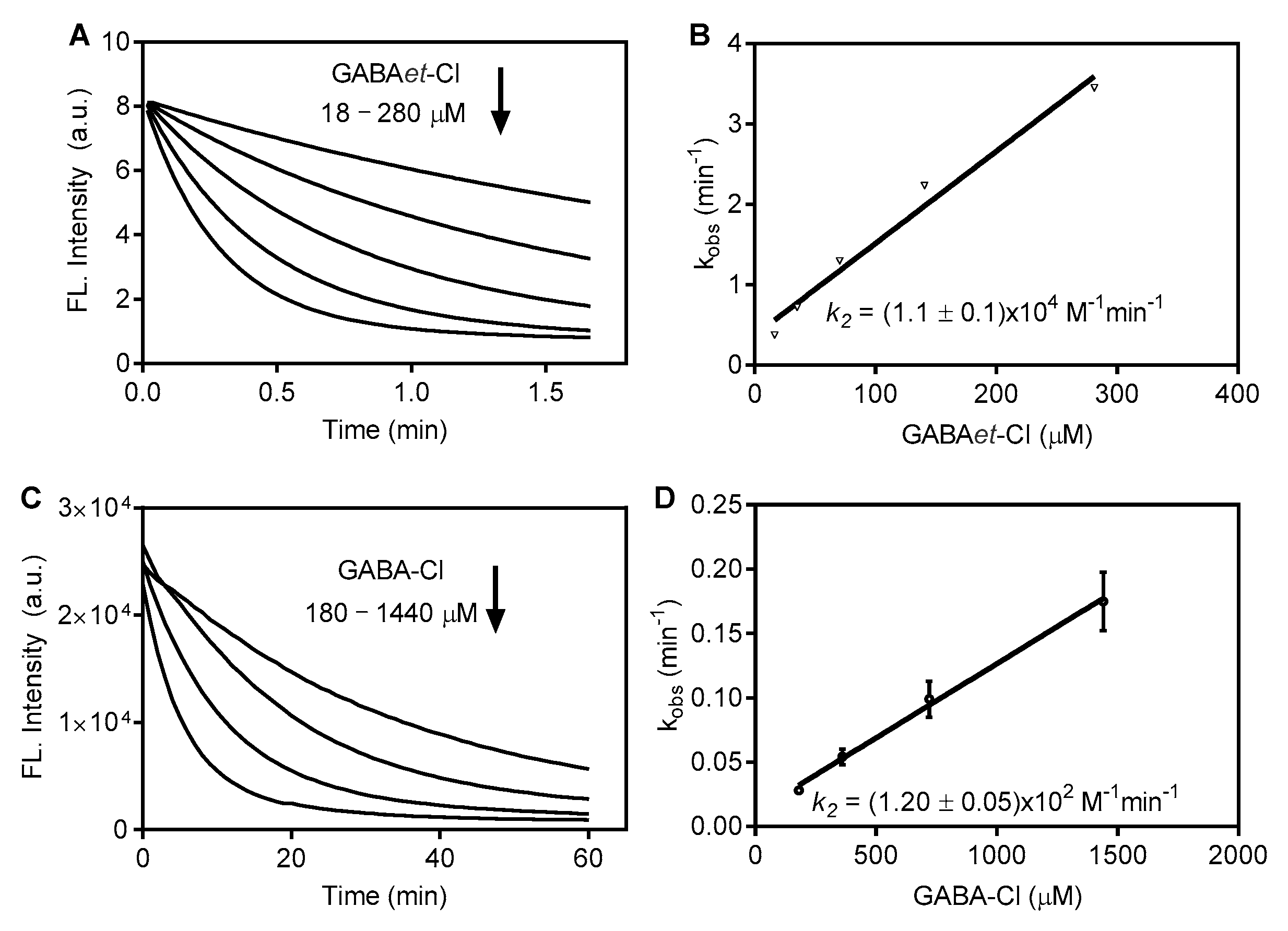

2.2. The Impact of Esterification on the Reactivity of GABA Chloramine in SDS Micelles

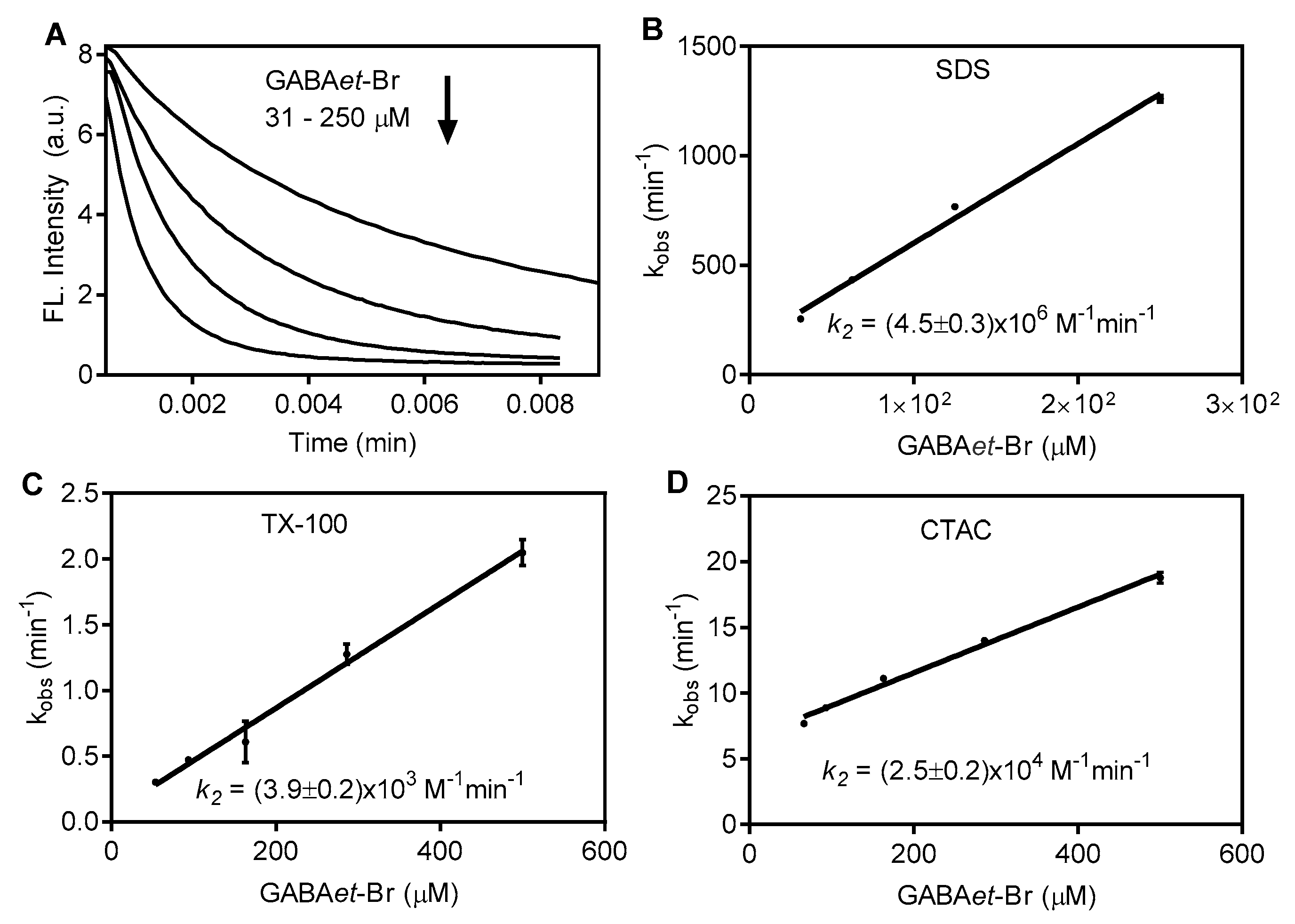

2.3. Increasing Reactivity: GABAet-Cl Versus GABAet-Br in SDS Micelles

2.4. The Nature of the Surfactants

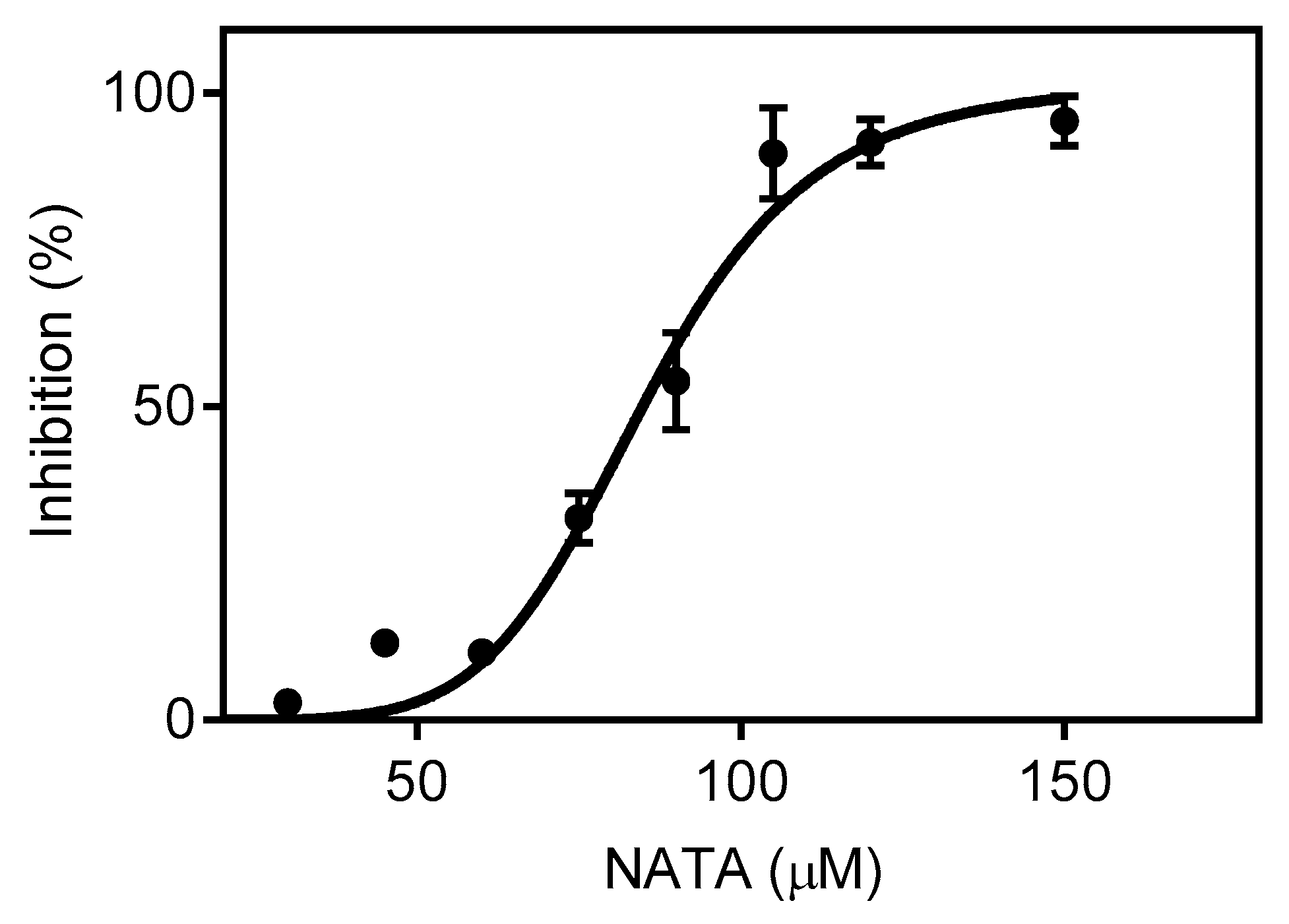

2.5. Competitive Inhibition of C153 Oxidation

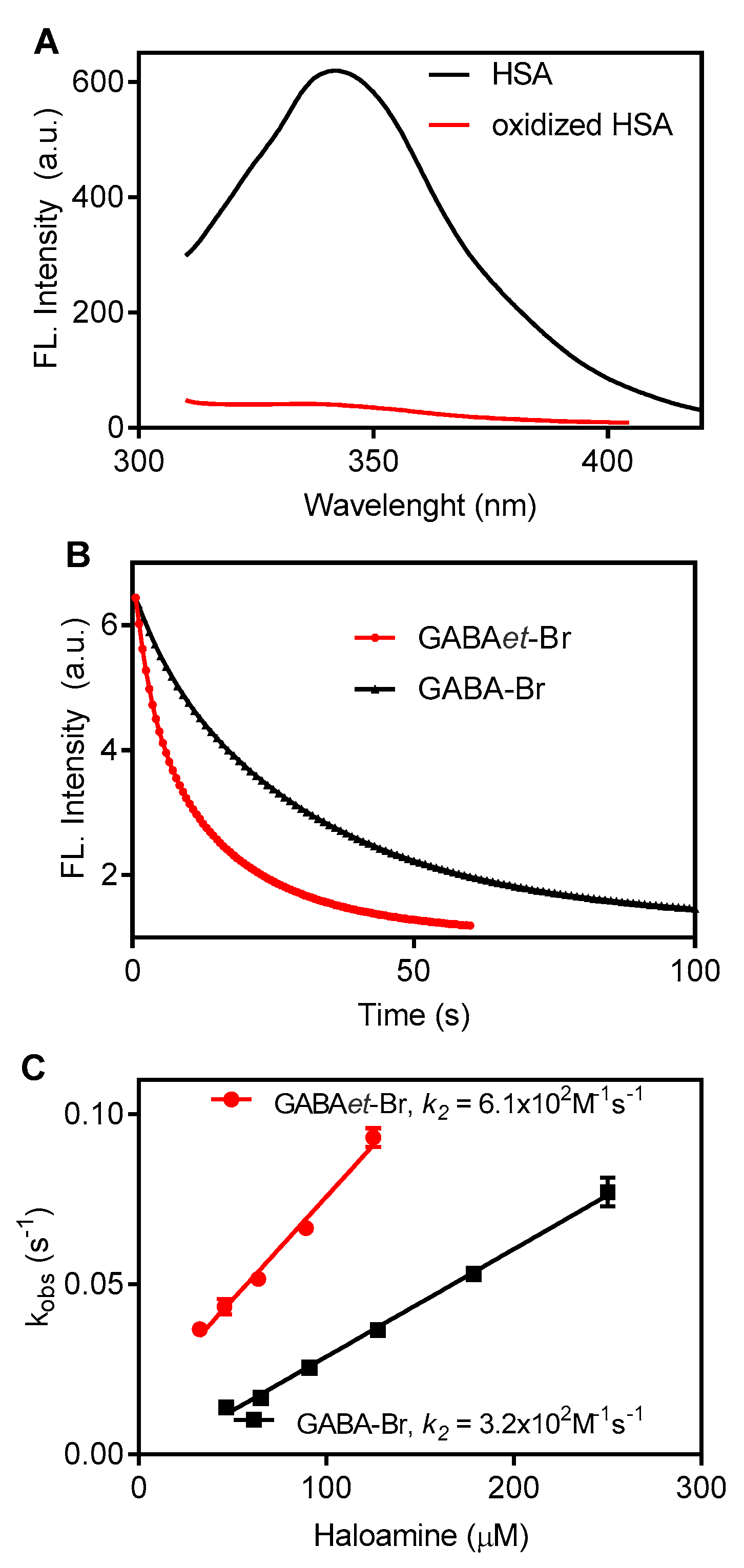

2.6. Oxidation of Tryptophan Residues in Albumin

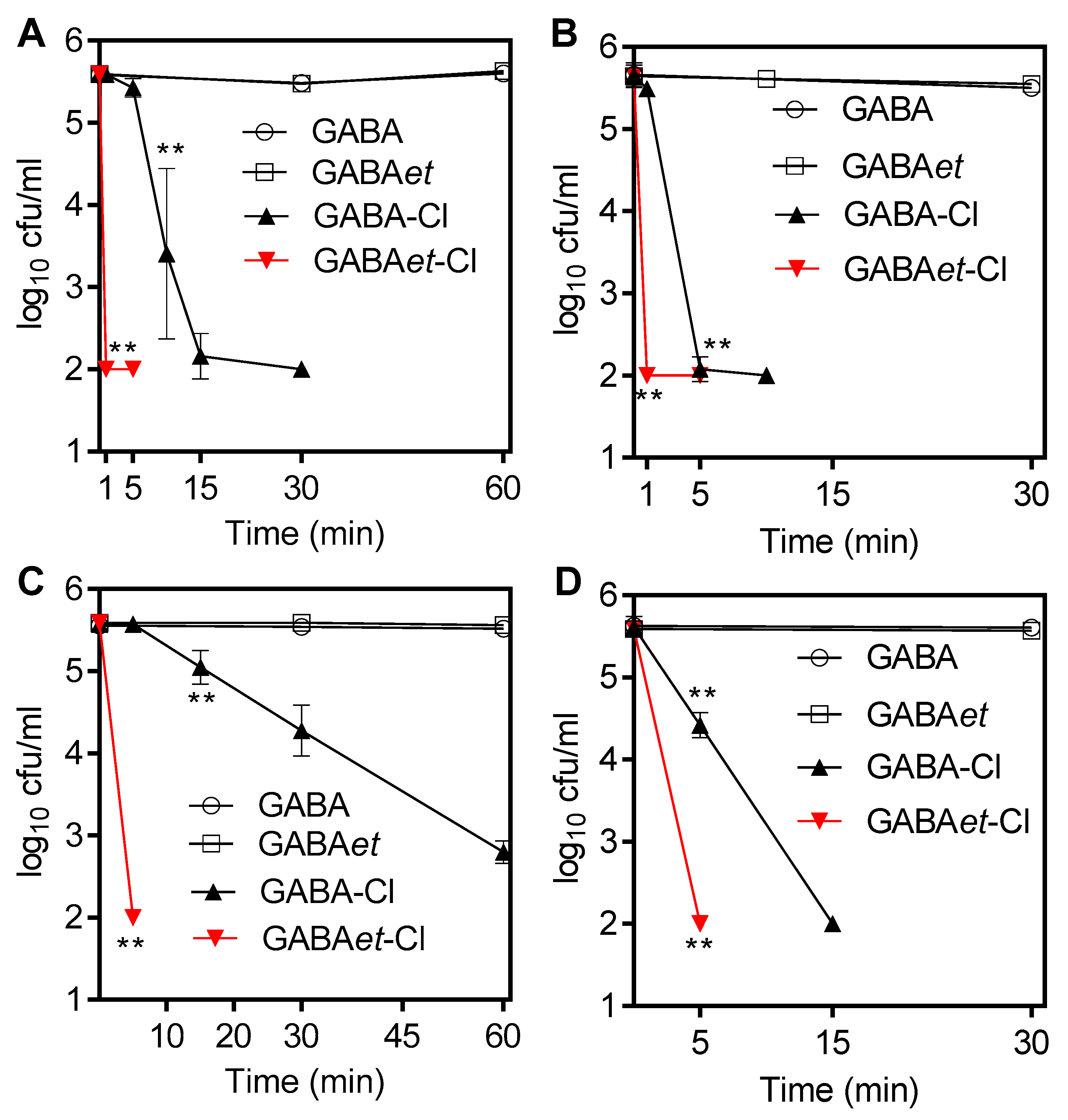

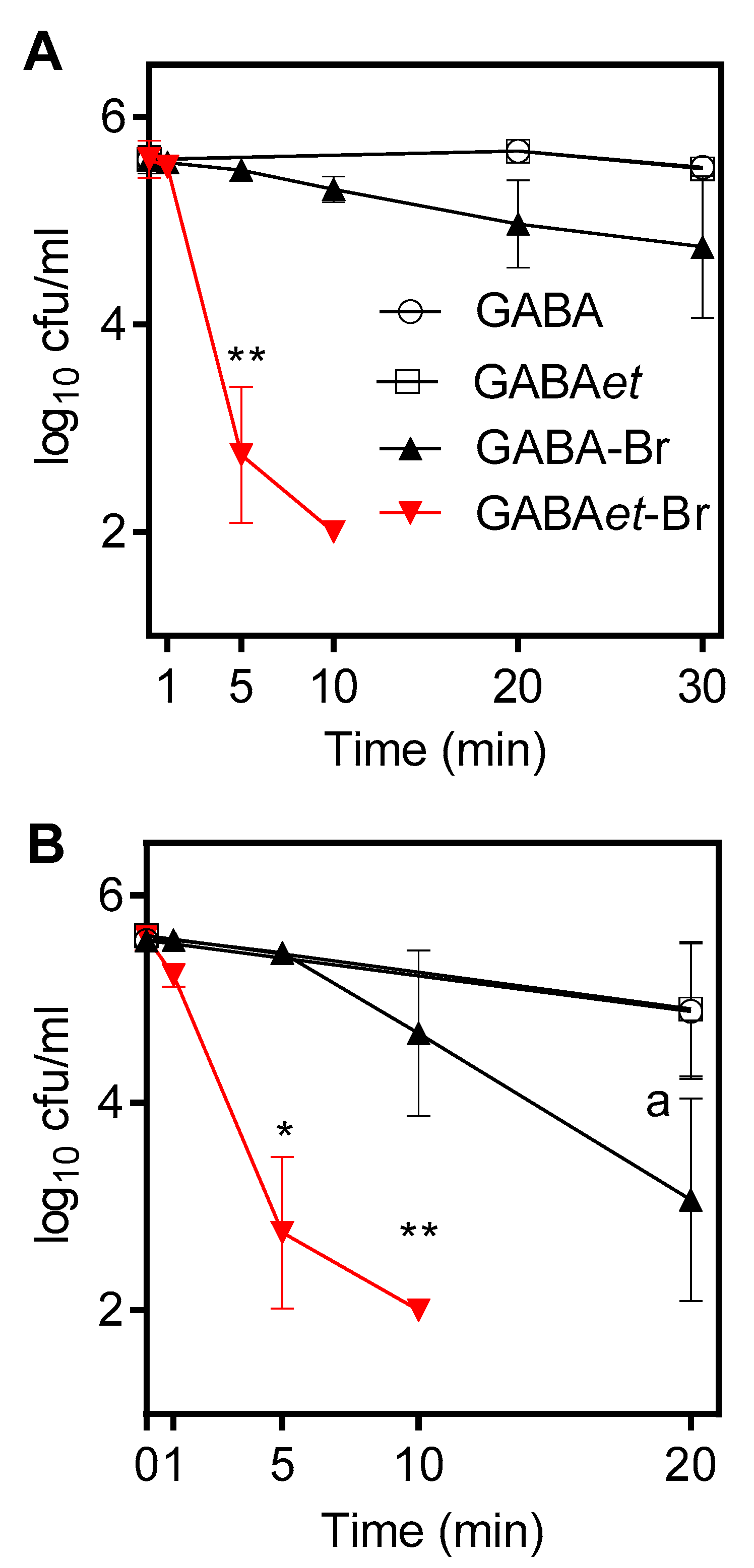

2.7. Application as Bactericidal Agents

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Preparation of Hypohalous Acids and Haloamines Solutions

3.3. Reaction of Haloamines with Molecular Targets: General Procedure

3.4. Determination of Second-Order Rate Constants

3.5. Chemiluminescence Studies

3.6. Oxidation of Human Serum Albumin

3.7. Bacteria Killing Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AZA | 2,5-Bis-(4-methylsulfanyl-phenyl)-1,4-di-p-tolyl-1,4-dihydro-pyrrolo[3,2-b]pyrrole |

| DTNB | 5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid |

| C153 | Coumarin 153 |

| CMC | Critical micellar concentration |

| CTAC | Cetyltrimethylammonium chloride |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GABA-Cl | Chloramine of GABA |

| GABA-Br | Bromamine of GABA |

| GABAet-Cl | Chloramine of the ethyl ester of GABA |

| GABA-et-Br | Bromamine of the ethyl ester of GABA |

| HSA | Human serum albumin |

| NATA | N-acetyl-L-tryptophanamide |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| Tau-Cl | Chloramine of taurine |

| Tau-Br | Bromamine of taurine |

| TX-100 | Triton X-100 |

References

- Weiss, S.; Klein, R.; Slivka, A.; Wei, M. Chlorination of Taurine by Human-Neutrophils—Evidence for Hypochlorous Acid Generation. J. Clin. Investig. 1982, 70, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learn, D.B.; Fried, V.A.; Thomas, E.L. Taurine and Hypotaurine Content of Human Leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1990, 48, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, L.A.; Dunford, H.B. Chlorination of Taurine by Myeloperoxidase. Kinetic Evidence for an Enzyme-Bound Intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 7950–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, C. The Roles of Neutrophil-Derived Myeloperoxidase (MPO) in Diseases: The New Progress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokumsen, K.V.; Huhle, V.H.; Hagglund, P.M.; Davies, M.J.; Gamon, L.F. Elevated Levels of Iodide Promote Peroxidase-Mediated Protein Iodination and Inhibit Protein Chlorination. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 220, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangie, C.; Daher, J. Role of Myeloperoxidase in Inflammation and Atherosclerosis (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2022, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.O.; Shapiro, J.P.; Cottrill, K.A.; Collins, G.L.; Shanthikumar, S.; Rao, P.; Ranganathan, S.; Stick, S.M.; Orr, M.L.; Fitzpatrick, A.M.; et al. Substrate-Dependent Metabolomic Signatures of Myeloperoxidase Activity in Airway Epithelial Cells: Implications for Early Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 206, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagl, M.; Arnitz, R.; Lackner, M. N-Chlorotaurine, a Promising Future Candidate for Topical Therapy of Fungal Infections. Mycopathologia 2018, 183, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, C.; Rambach, G.; Windisch, A.; Neurauter, M.; Maier, H.; Nagl, M. Efficacy of Inhaled N-Chlorotaurine in a Mouse Model of Lichtheimia Corymbifera and Aspergillus Fumigatus Pneumonia. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczewska, M.; Peruń, A.; Białecka, A.; Śróttek, M.; Jamróz, W.; Dorożyński, P.; Jachowicz, R.; Kulinowski, P.; Nagl, M.; Gottardi, W.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Microbicidal and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Novel Taurine Bromamine Derivatives and Bromamine T. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 975 Pt 1, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashevych, B.; Girenko, D.; Koshova, I.; Maslak, G.; Burmistrov, K.; Stepanskyi, D. Broad-Purpose Solutions of N-Chlorotaurine: A Convenient Synthetic Approach and Comparative Evaluation of Stability and Antimicrobial Activity. J. Chem. 2024, 2024, 8959915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnitz, R.; Stein, M.; Bauer, P.; Lanthaler, B.; Jamnig, H.; Scholl-Bürgi, S.; Stempfl-Al-Jazrawi, K.; Ulmer, H.; Baumgartner, B.; Embacher, S.; et al. Tolerability of Inhaled N-Chlorotaurine in Humans: A Double-Blind Randomized Phase I Clinical Study. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2018, 12, 1753466618778955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuchner, B.; Nagl, M.; Schidlbauer, A.; Ishiko, H.; Dragosits, E.; Ulmer, H.; Aoki, K.; Ohno, S.; Mizuki, N.; Gottardi, W.; et al. Tolerability and Efficacy of N-Chlorotaurine in Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis--a Double-Blind, Randomized, Phase-2 Clinical Trial. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 21, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Nagl, M.; Gupta, R.C.; Marcinkiewicz, J. Taurine and N-Bromotaurine in Topical Treatment of Psoriasis. In Taurine 12: A Conditionally Essential Amino Acid; Schaffer, S.W., El Idrissi, A., Murakami, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 99–111. ISBN 978-3-030-93337-1. [Google Scholar]

- Arnhold, J.; Malle, E. Halogenation Activity of Mammalian Heme Peroxidases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, D.I.; Davies, M.J. Kinetic Analysis of the Reactions of Hypobromous Acid with Protein Components: Implications for Cellular Damage and Use of 3-Bromotyrosine as a Marker of Oxidative Stress. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 4799–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximenes, V.F.; da Fonseca, L.M.; de Almeida, A.C. Taurine Bromamine: A Potent Oxidant of Tryptophan Residues in Albumin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 507, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, C.L.; Malejka-Giganti, D. Oxidations of the Carcinogen N-Hydroxy-N-(2-Fluorenyl)Acetamide by Enzymatically or Chemically Generated Oxidants of Chloride and Bromide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1989, 2, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho Bertozo, L.; Morgon, N.H.; De Souza, A.R.; Ximenes, V.F. Taurine Bromamine: Reactivity of an Endogenous and Exogenous Anti-Inflammatory and Antimicrobial Amino Acid Derivative. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliou, S.; Sofopoulos, M.; Goulielmaki, M.; Spandidos, D.A.; Ioannou, P.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Zoumpourlis, V. Bromamine T, a Stable Active Bromine Compound, Prevents the LPS-induced Inflammatory Response. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 47, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasich, E.; Walczewska, M.; Białecka, A.; Peruń, A.; Kasprowicz, A.; Marcinkiewicz, J. Taurine Haloamines and Biofilm: II. Efficacy of Taurine Bromamine and Chlorhexidine Against Selected Microorganisms of Oral Biofilm. In Taurine 9; Marcinkiewicz, J., Schaffer, S.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkiewicz, J. Taurine Bromamine (TauBr)—Its Role in Immunity and New Perspectives for Clinical Use. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010, 17 (Suppl. S1), S3. Available online: https://jbiomedsci.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1423-0127-17-S1-S3 (accessed on 9 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.; Tipton, F.K.; Dixon, B.F.H. Conversion of Taurine into N-Chlorotaurine (Taurine Chloramine) and Sulphoacetaldehyde in Response to Oxidative Stress. Biochem. J. 1998, 330, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.L.; Grisham, M.B.; Jefferson, M.M. Preparation and Characterization of Chloramines. Methods Enzymol. 1986, 132, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, N.M.; Martins, L.M.; Augusto, L.C.; da Silva-Filho, L.C.; Ximenes, V.F. Development of Fluorescent Azapentalenes to Study the Reactivity of Hypochlorous Acid and Chloramines in Micellar Systems. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 365, 120137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, M.; Staats, K.; Assadian, O.; Windhager, R.; Holinka, J. Tolerability of N-Chlorotaurine in Comparison with Routinely Used Antiseptics: An in Vitro Study on Chondrocytes. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 76, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskina, A.V.; Midwinter, R.G.; Harwood, D.T.; Winterbourn, C.C. Chlorine Transfer between Glycine, Taurine, and Histamine: Reaction Rates and Impact on Cellular Reactivity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 38, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.L.; Bozeman, P.M.; Jefferson, M.M.; King, C.C. Oxidation of Bromide by the Human Leukocyte Enzymes Myeloperoxidase and Eosinophil Peroxidase. Formation of Bromamines. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 2906–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kettle, A.J.; Albrett, A.M.; Chapman, A.L.; Dickerhof, N.; Forbes, L.V.; Khalilova, I.; Turner, R. Measuring Chlorine Bleach in Biology and Medicine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ximenes, V.F.; Padovan, C.Z.; Carvalho, D.A.; Fernandes, J.R. Oxidation of Melatonin by Taurine Chloramine. J. Pineal Res. 2010, 49, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkiewicz, J.; Mak, M.; Bobek, M.; Biedroń, R.; Białecka, A.; Koprowski, M.; Kontny, E.; Maśliński, W. Is There a Role of Taurine Bromamine in Inflammation? Interactive Effects with Nitrite and Hydrogen Peroxide. Inflamm. Res. 2005, 54, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciążek-Jurczyk, M.; Sułkowska, A. Spectroscopic Analysis of the Impact of Oxidative Stress on the Structure of Human Serum Albumin (HSA) in Terms of Its Binding Properties. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 136 Pt B, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dypbukt, J.M.; Bishop, C.; Brooks, W.M.; Thong, B.; Eriksson, H.; Kettle, A.J. A Sensitive and Selective Assay for Chloramine Production by Myeloperoxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 39, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Hawkins, C.L.; Thomas, S.R.; Stocker, R.; Frei, B. Relative Reactivities of N-Chloramines and Hypochlorous Acid with Human Plasma Constituents. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 30, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, A.V.; Winterbourn, C.C. Kinetics of the Reactions of Hypochlorous Acid and Amino Acid Chloramines with Thiols, Methionine, and Ascorbate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 30, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdeldaim, D.T.; Mansour, F.R. Micelle-Enhanced Flow Injection Analysis. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018, 37, 20170009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, C. Long-Lasting Chemiluminescence by Aggregation-Induced Emission Surfactant with Ultralow Critical Micelle Concentration. Aggregate 2023, 4, e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaff, O.; Pattison, D.I.; Davies, M.J. Kinetics of Hypobromous Acid-Mediated Oxidation of Lipid Components and Antioxidants. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; Fu, J.; Du, Y.; Lin, L.; Bai, L.; Wang, D. Role of Hypobromous Acid in the Transformation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons during Chlorination. Water Res. 2021, 207, 117787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeb, M.B.; Kristiana, I.; Trogolo, D.; Arey, J.S.; von Gunten, U. Formation and Reactivity of Inorganic and Organic Chloramines and Bromamines during Oxidative Water Treatment. Water Res. 2017, 110, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplâtre, G.; Ferreira Marques, M.F.; da Graça Miguel, M. Size of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Micelles in Aqueous Solutions as Studied by Positron Annihilation Lifetime Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 16608–16612. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jp960644m (accessed on 10 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Dharaiya, N.; Ray, D.; Aswal, V.K.; Bahadur, P. pH Controlled Size/Shape in CTAB Micelles with Solubilized Polar Additives: A Viscometry, Scattering and Spectral Evaluation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 455, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chai, X.; Sun, P.; Yuan, B.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M. The Study of the Aggregated Pattern of TX100 Micelle by Using Solvent Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancements. Molecules 2019, 24, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelepouris, L.; Blanchard, G.J. Dynamics of 7-Azatryptophan and Tryptophan Derivatives in Micellar Media. The Role of Ionic Charge and Substituent Structure. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, G.; di Masi, A.; Trezza, V.; Marino, M.; Fasano, M.; Ascenzi, P. Human Serum Albumin: From Bench to Bedside. Mol. Asp. Med. 2012, 33, 209–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Qaiser, H.; Tariq, S.; Khalid, A.; Makeen, H.A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Ul-Haq, Z. Unraveling the Versatility of Human Serum Albumin—A Comprehensive Review of Its Biological Significance and Therapeutic Potential. Curr. Res. Struct. Biol. 2023, 6, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, K.; Yamasaki, K.; Otagiri, M. Serum Albumin, Lipid and Drug Binding. In Vertebrate and Invertebrate Respiratory Proteins, Lipoproteins and other Body Fluid Proteins; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 94, pp. 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Bertozo, L.; Fernandes, A.J.F.C.; Yoguim, M.I.; Bolean, M.; Ciancaglini, P.; Ximenes, V.F. Entropy-Driven Binding of Octyl Gallate in Albumin: Failure in the Application of Temperature Effect to Distinguish Dynamic and Static Fluorescence Quenching. J. Mol. Recognit. 2020, 33, e2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorudko, I.V.; Grigorieva, D.V.; Shamova, E.V.; Kostevich, V.A.; Sokolov, A.V.; Mikhalchik, E.V.; Cherenkevich, S.N.; Arnhold, J.; Panasenko, O.M. Hypohalous Acid-Modified Human Serum Albumin Induces Neutrophil NADPH Oxidase Activation, Degranulation, and Shape Change. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 68, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova, I.I.; Sokolov, A.V.; Kostevich, V.A.; Mikhalchik, E.V.; Vasilyev, V.B. Myeloperoxidase-Induced Oxidation of Albumin and Ceruloplasmin: Role of Tyrosines. Biochem. Mosc. 2019, 84, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prazeres, T.J.V.; Beija, M.; Fernandes, F.V.; Marcelino, P.G.A.; Farinha, J.P.S.; Martinho, J.M.G. Determination of the Critical Micelle Concentration of Surfactants and Amphiphilic Block Copolymers Using Coumarin 153. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2012, 381, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.A.; Mozaheb, M.A.; Hatefi-Mehrjardi, A.; Tavallali, H.; Attaran, A.M.; Shamsi, R. A New Simple Method for Determining the Critical Micelle Concentration of Surfactants Using Surface Plasmon Resonance of Silver Nanoparticles. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkiewicz, J.; Strus, M.; Walczewska, M.; Machul, A.; Mikołajczyk, D. Influence of Taurine Haloamines auCl and TauBr) on the Development of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm: A Preliminary Study. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 775, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, N. State of the Art of UV/Chlorine Advanced Oxidation Processes: Their Mechanism, Byproducts Formation, Process Variation, and Applications. J. Water Environ. Technol. 2019, 17, 302–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, S.; Kanayama, A.; Miyamoto, Y. Modification of IkappaBalpha by Taurine Bromamine Inhibits Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-Induced NF-kappaB Activation. Inflamm. Res. 2007, 56, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, B.; Sarg, B.; Lindner, H.H.; Nagl, M. Inactivation of Microbicidal Active Halogen Compounds by Sodium Thiosulphate and Histidine/Methionine for Time-Kill Assays. J. Microbiol. Methods 2017, 141, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bertozo, L.d.C.; Nagl, M.; Ximenes, V.F. Haloamines of the Neurotransmitter γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Its Ethyl Ester: Mild Oxidants for Reactions in Hydrophobic Microenvironments and Bactericidal Activity. Molecules 2025, 30, 4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214227

Bertozo LdC, Nagl M, Ximenes VF. Haloamines of the Neurotransmitter γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Its Ethyl Ester: Mild Oxidants for Reactions in Hydrophobic Microenvironments and Bactericidal Activity. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214227

Chicago/Turabian StyleBertozo, Luiza de Carvalho, Markus Nagl, and Valdecir Farias Ximenes. 2025. "Haloamines of the Neurotransmitter γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Its Ethyl Ester: Mild Oxidants for Reactions in Hydrophobic Microenvironments and Bactericidal Activity" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214227

APA StyleBertozo, L. d. C., Nagl, M., & Ximenes, V. F. (2025). Haloamines of the Neurotransmitter γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Its Ethyl Ester: Mild Oxidants for Reactions in Hydrophobic Microenvironments and Bactericidal Activity. Molecules, 30(21), 4227. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214227