Application of a Novel Solid Silver Microelectrode Array for Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Thallium(I)

Abstract

1. Introduction

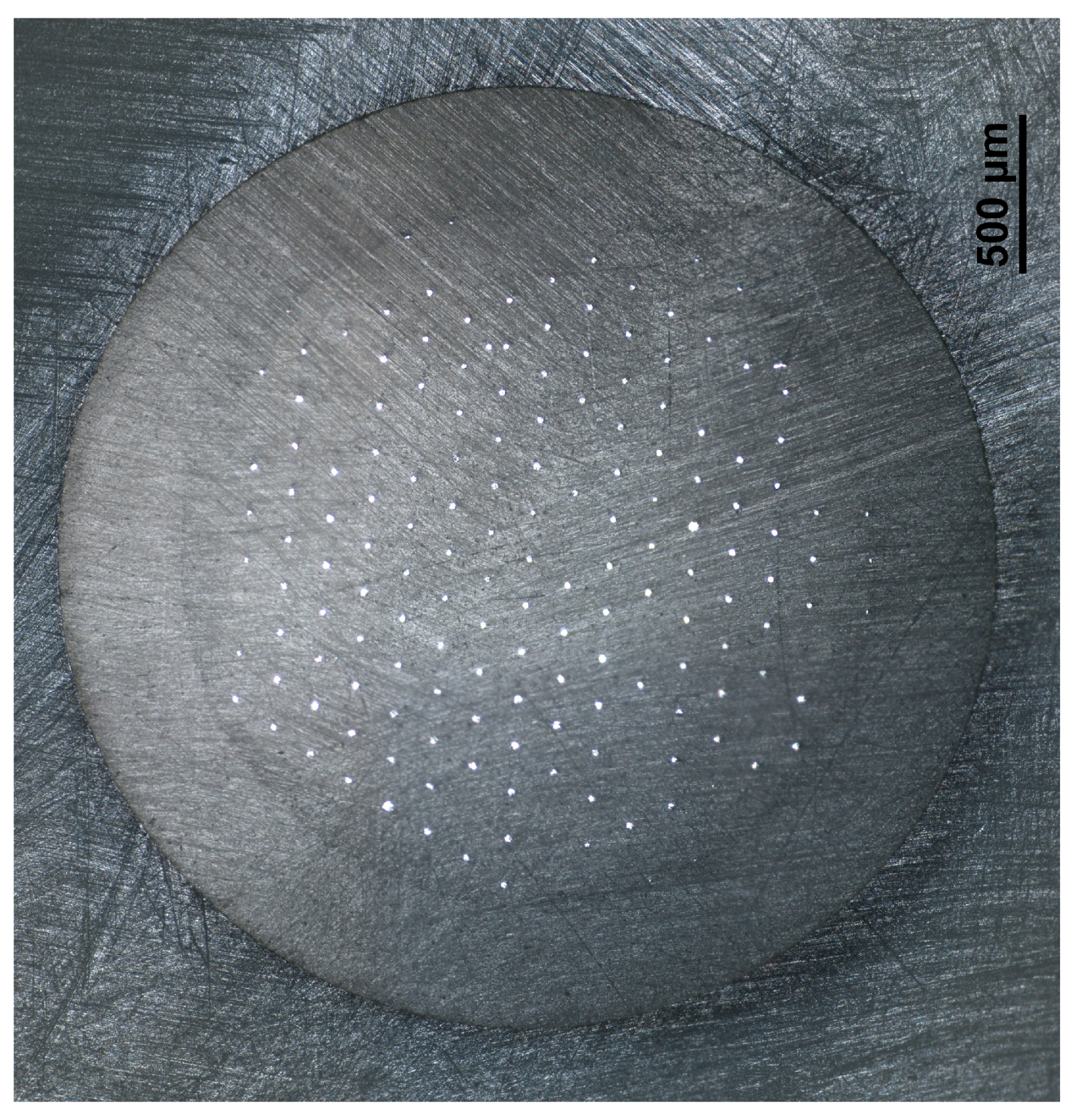

2. Results

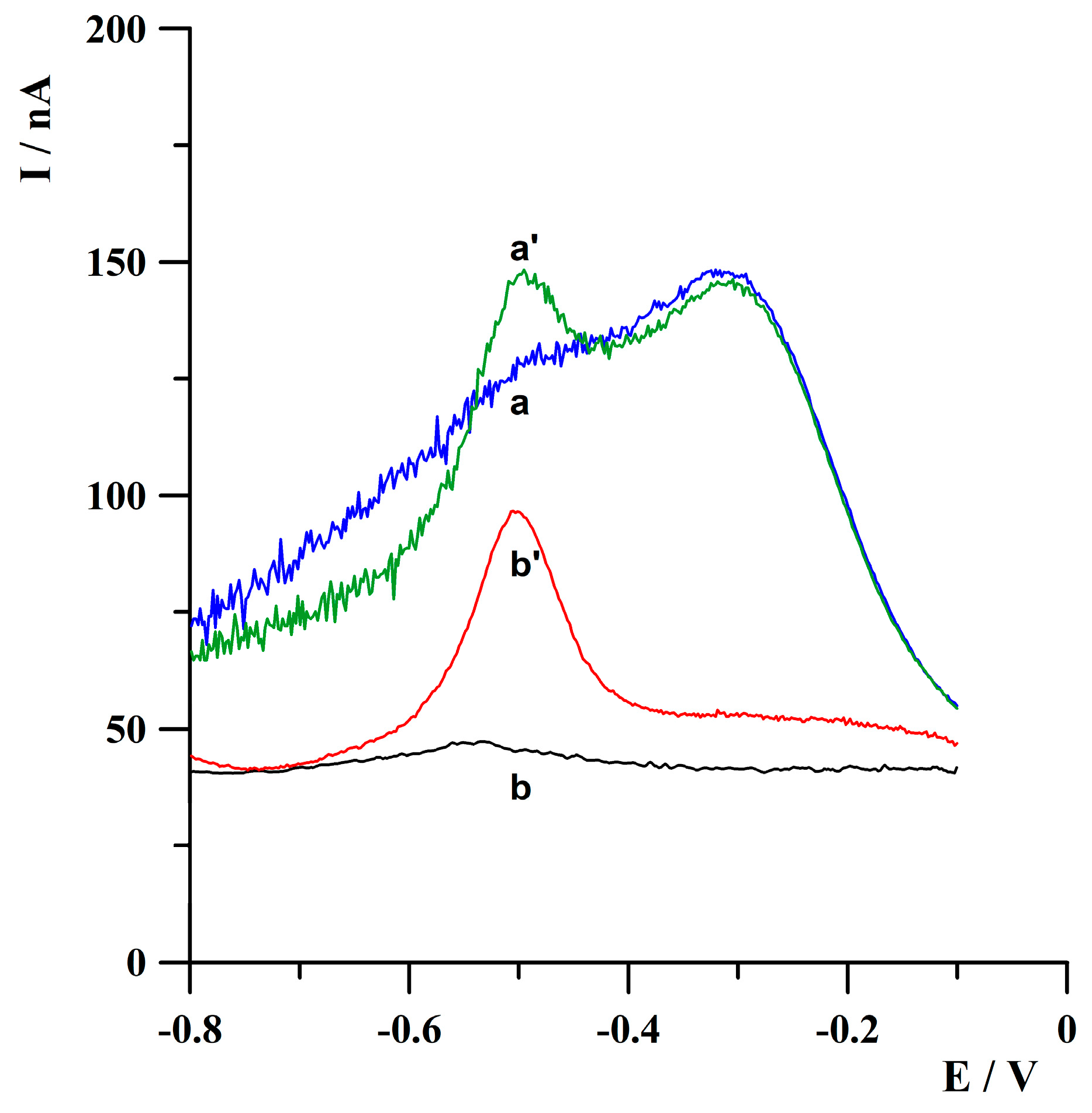

2.1. The Effect of a Solution Deoxygenation

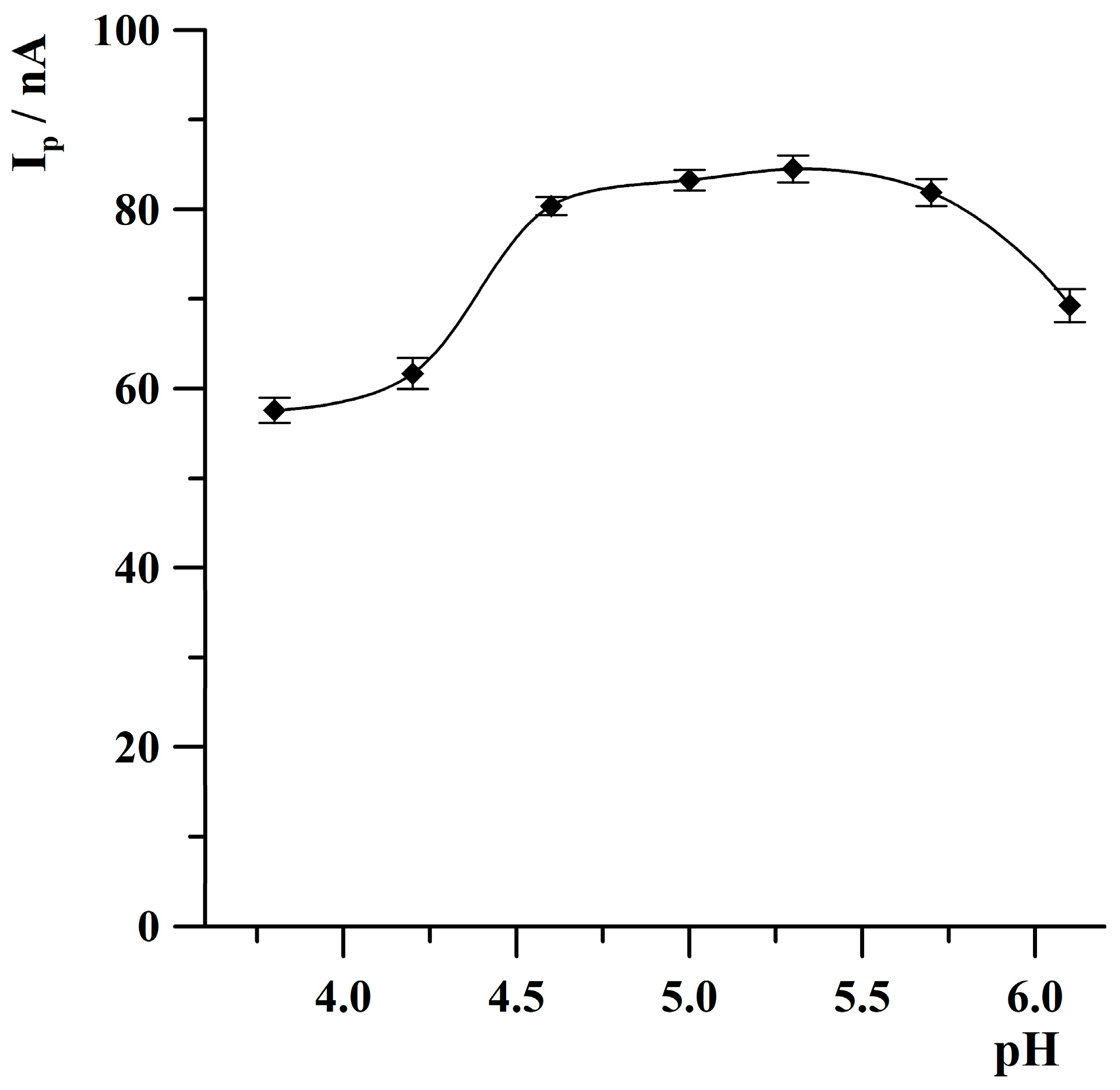

2.2. The Effect of pH and Concentration of Acetate Buffer and Na2EDTA

2.2.1. pH Optimization Study

2.2.2. Optimization of the Concentration of an Acetate Buffer

2.2.3. Optimization of the Concentration of Na2EDTA

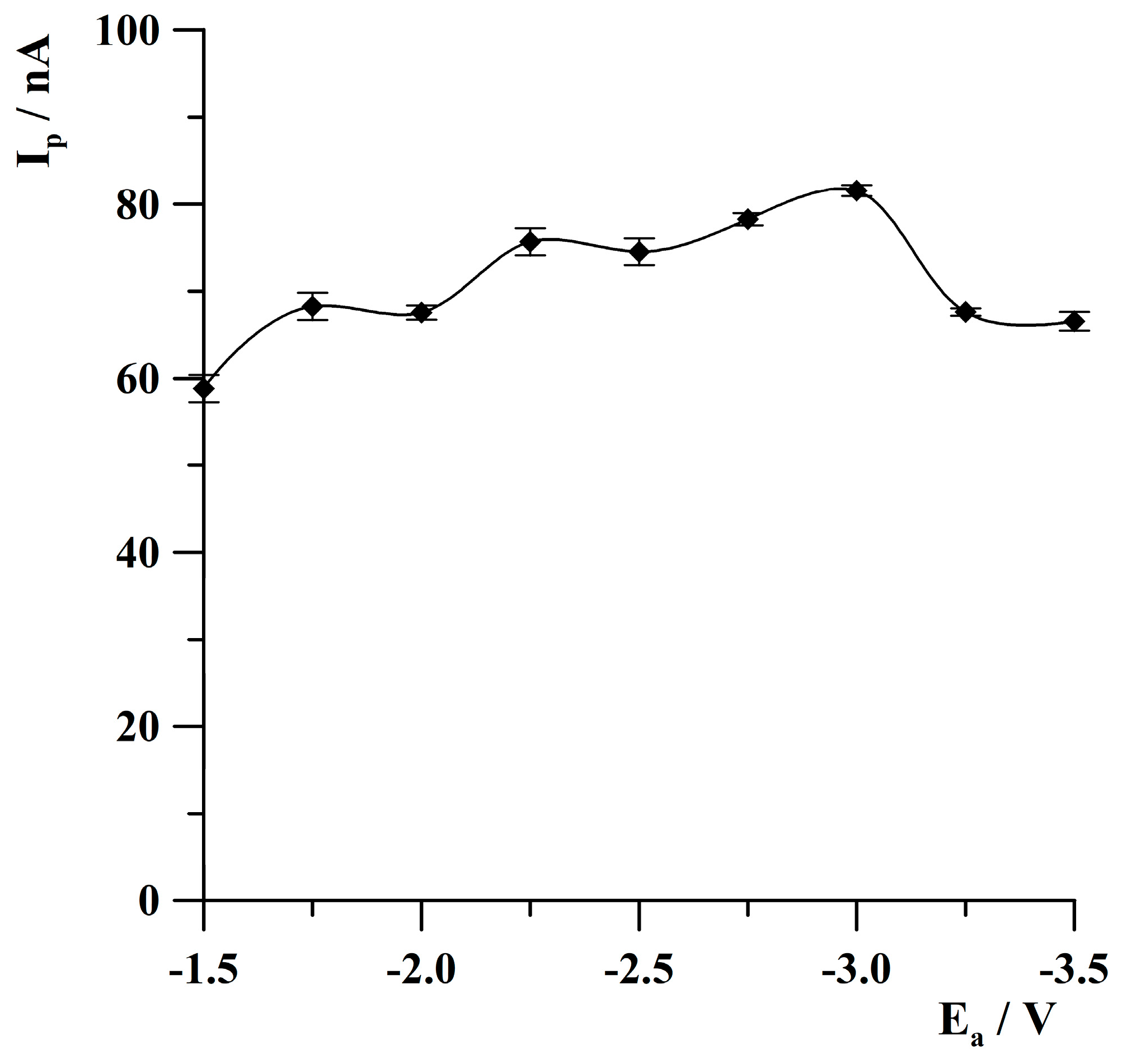

2.3. Optimization of Activation Conditions

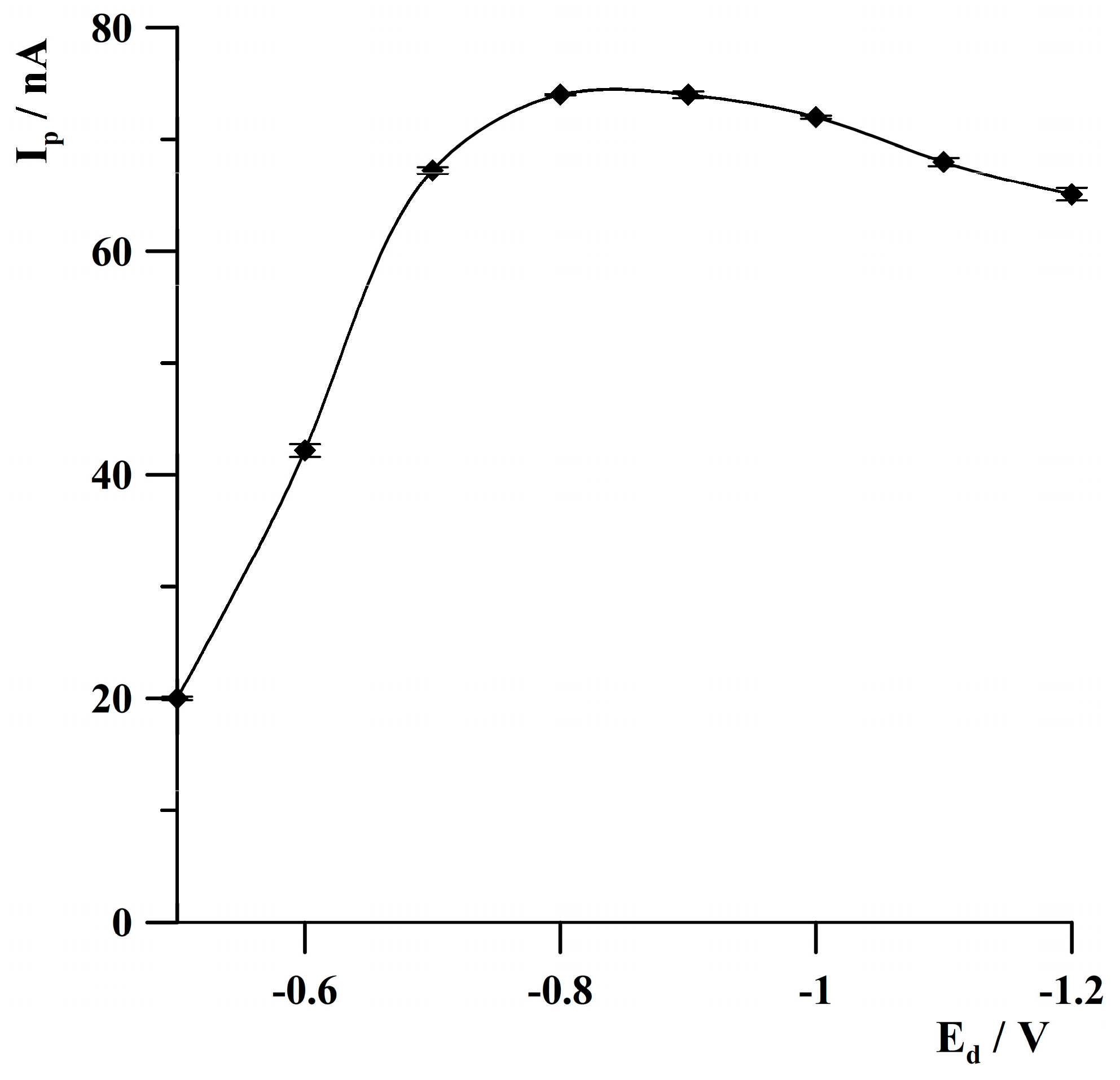

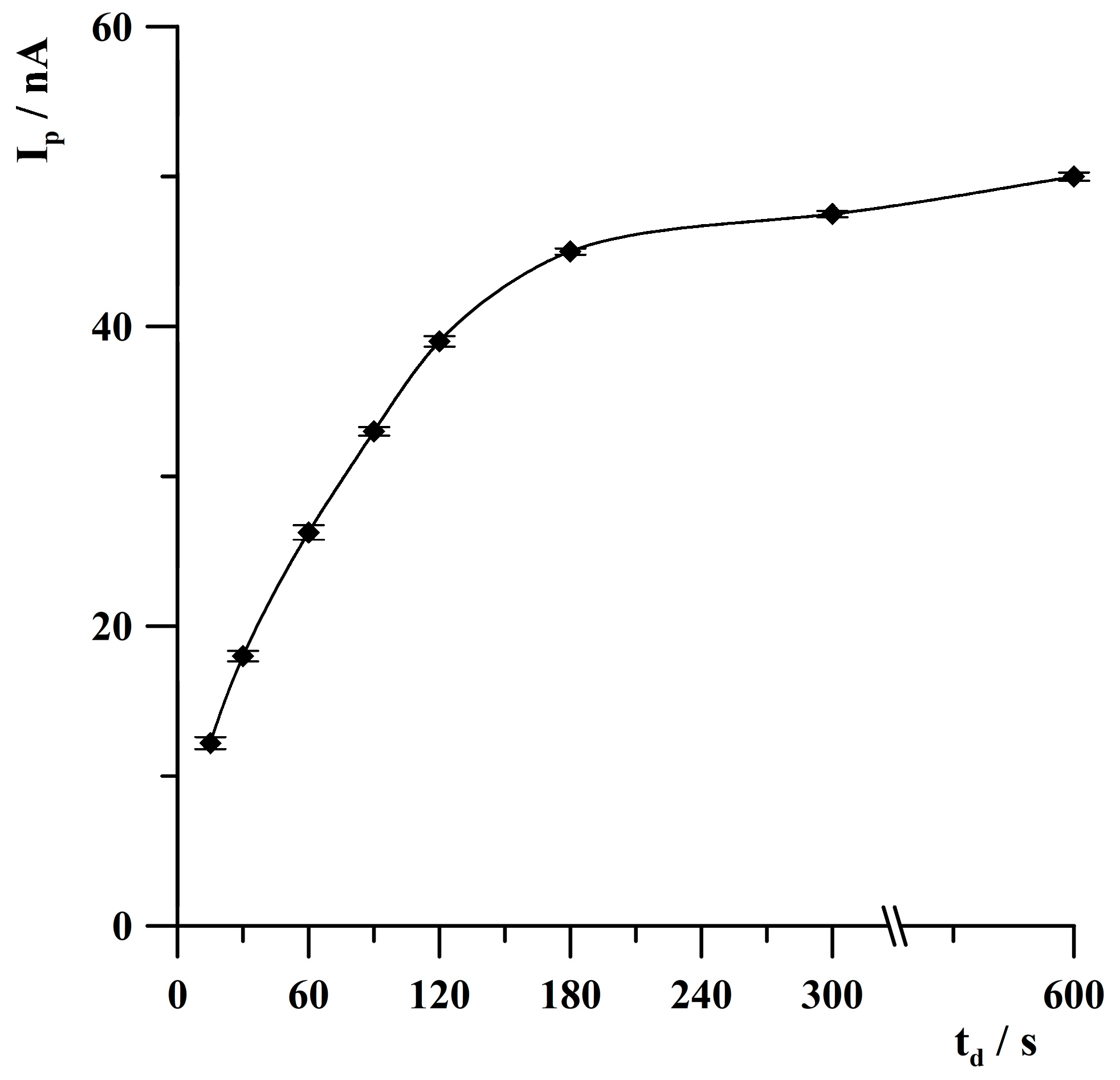

2.4. Optimization of Deposition Conditions

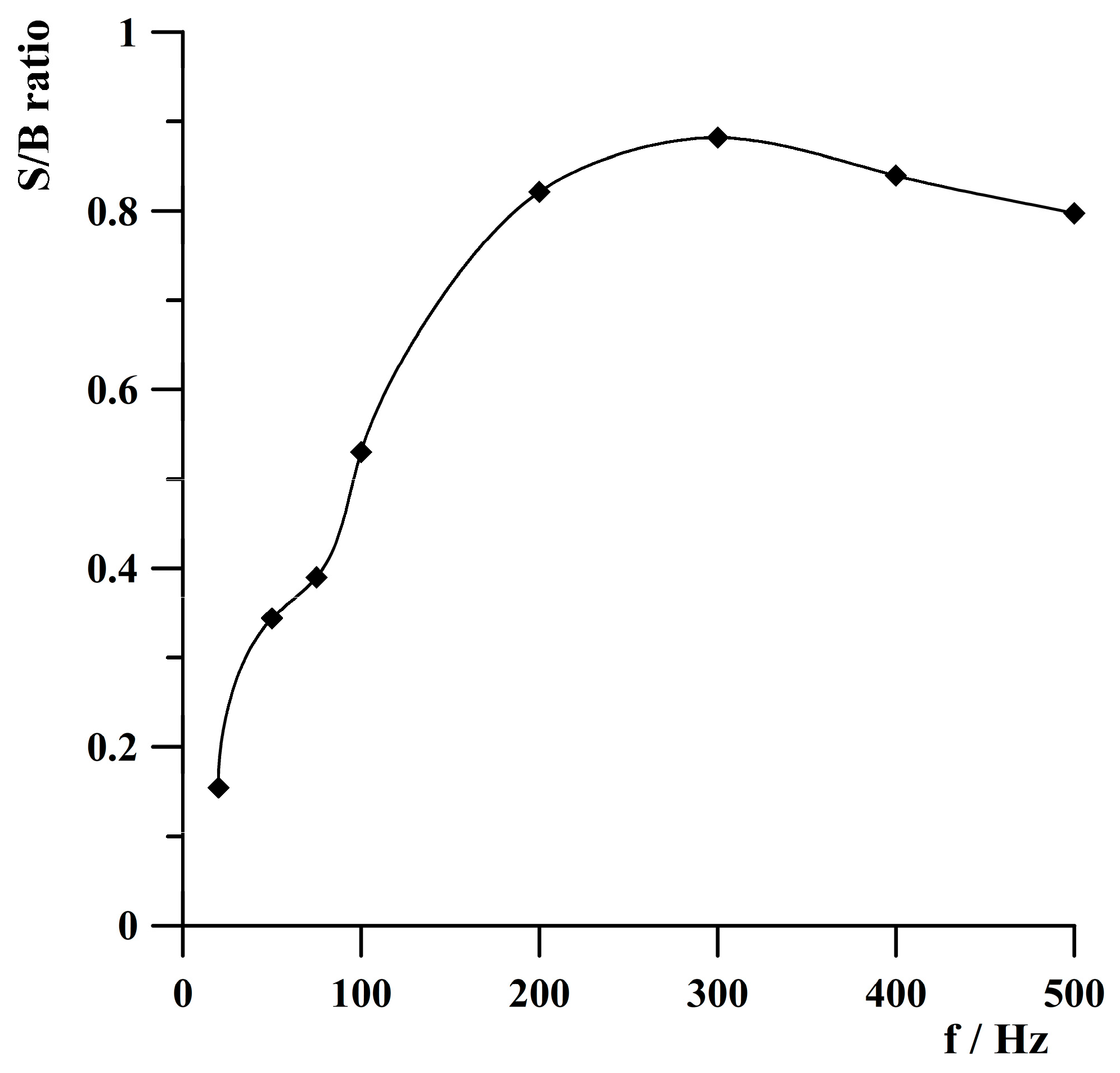

2.5. Optimization of Frequency

2.6. Calibration Data

2.7. Studies of Repeatability

2.8. Studies of Interference Effects

2.9. Analysis of Environmental Water Samples

3. Materials and Methods

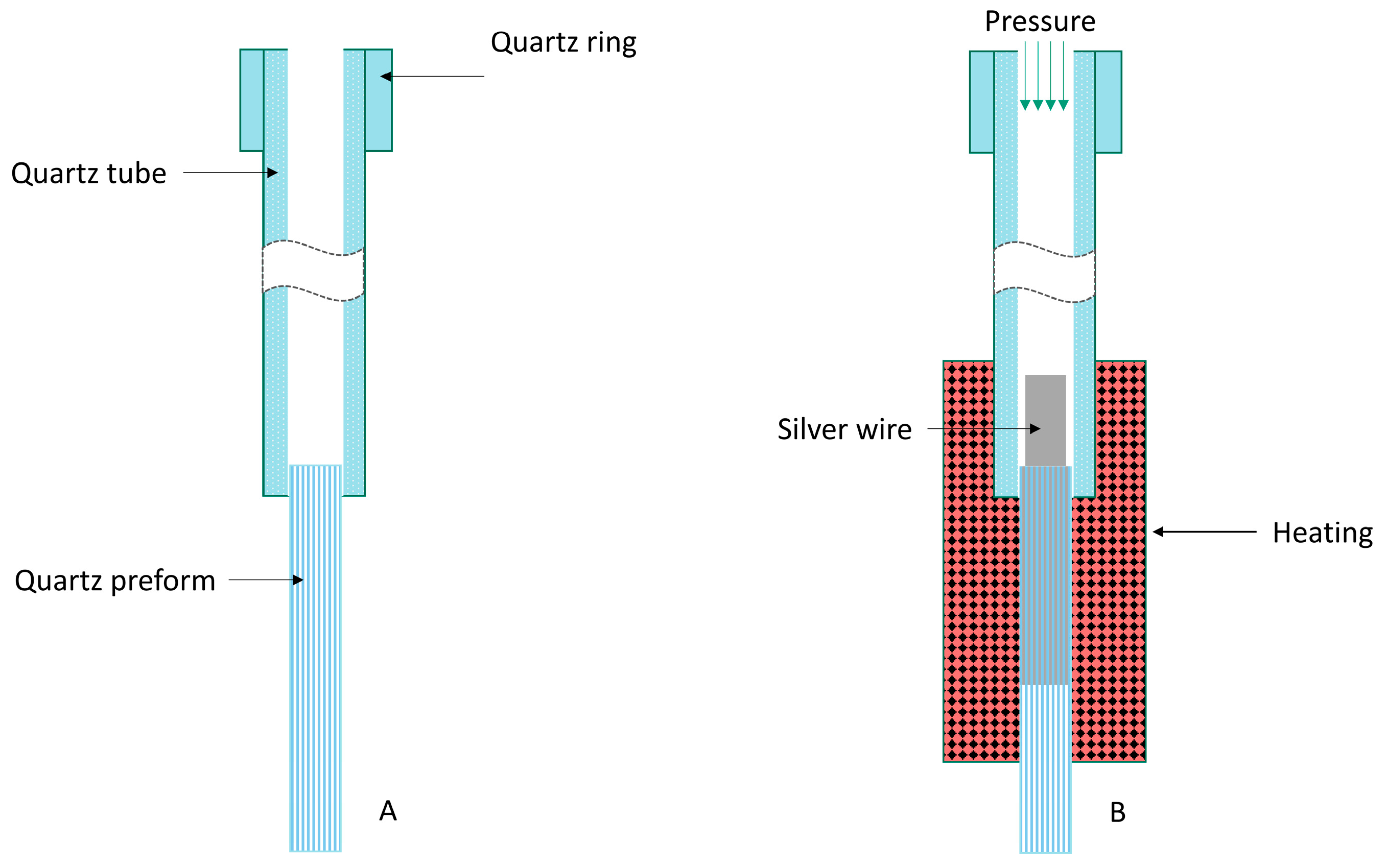

3.1. Apparatus

3.2. Reagents

3.3. Preparation of the Real Water Sample

3.4. Standard Procedure of the Measurements

- The activation step, needed for the working electrode’s surface preparation, was performed by applying a short potential pulse of −3.0 V within 1 s;

- The deposition time step, within which thallium ions underwent reduction to the metallic state on the surface of the microelectrode array, was conducted at a potential of −0.8 V within 120 s;

- After a ten-second equilibration step, a square wave anodic stripping voltammogram was recorded while the potential was changed from −0.8 to −0.1 V. Frequency, amplitude and step potential were 300 Hz, 25 mV and 5 mV, respectively. The research was conducted after a 5-minute solution deoxygenation with nitrogen as an inert gas.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kemnic, T.R.; Coleman, M. Thallium Toxicity; StatPearls Publishing: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Galván-Arzate, S.; Santamaría, A. Thallium Toxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 1998, 99, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, T.; Mizui, C.; Shimada, T.; Kubota, M. Determination of Thallium in Soils by Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry. Fresenius. J. Anal. Chem. 1996, 356, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tışlı, B.; Gösterişli, T.U.; Bakırdere, S. Determination of Thallium in Tea with Preconcentration by Microwave-Assisted Synthesized Molybdenum Disulfide Nanoparticles and Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (FAAS) Analysis. Anal. Lett. 2024, 57, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.A.; Santos, J.L.O.; Teixeira, L.S.G. Determination of Thallium in Water Samples via Solid Sampling HR-CS GF AAS after Preconcentration on Chromatographic Paper. Talanta 2024, 266, 124945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Ra, W.J.; Cho, S.; Choi, S.; Soh, B.; Joo, Y.; Lee, K.W. Method Validation for Determination of Thallium by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry and Monitoring of Various Foods in South Korea. Molecules 2021, 26, 6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, J.M.; Poitras, E.P.; Weber, F.X.; Fernando, R.A.; Liyanapatirana, C.; Robinson, V.G.; Levine, K.E.; Waidyanatha, S. Validation of Analytical Method for Determination of Thallium in Rodent Plasma and Tissues by Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Anal. Lett. 2022, 55, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, F.; Men, B.; He, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, D. Simultaneous Separation and Determination of Thallium in Water Samples by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2019, 42, 3311–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasnodȩbska-Ostrȩga, B.; Asztemborska, M.; Golimowski, J.; Strusińska, K. Determination of Thallium Forms in Plant Extracts by Anion Exchange Chromatography with Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry Detection (IC-ICP-MS). J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2008, 23, 1632–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Deng, L.; Li, H.; Lin, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, R.; Zou, J.; Niu, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Determination of Trace Heavy Metal Ion Tl(I) in Water by Energy Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry Using Prussian Blue Dispersed on Solid Sepiolite. Talanta 2025, 284, 127295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Dong, L.; Ji, J.; Zhao, P.; Song, G.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Simultaneous Detection of Trace As, Hg, Tl, and Pb in Biological Tissues Using Monochromatic Excitation X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2023, 38, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnodebska-Ostrega, B.; Pałdyna, J.; Wawrzyńska, M.; Stryjewska, E. Indirect Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Tl(I) and Tl(III) in the Baltic Seawater Samples Enriched in Thallium Species. Electroanalysis 2011, 23, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, S.A. Stripping Voltammetry of Thallium at a Film Mercury Electrode. J. Anal. Chem. 2003, 58, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, E.O.; Neto, M.M.M.; Rocha, M.M. A Mercury-Free Electrochemical Sensor for the Determination of Thallium(I) Based on the Rotating-Disc Bismuth Film Electrode. Talanta 2007, 72, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C.; Raptis, I.; Economou, A.; Speliotis, T. Determination of Trace Tl(I) by Anodic Stripping Voltammetry on Novel Disposable Microfabricated Bismuth-Film Sensors. Electroanalysis 2010, 22, 2359–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegiel, K.; Jedlińska, K.; Baś, B. Application of Bismuth Bulk Annular Band Electrode for Determination of Ultratrace Concentrations of Thallium(I) Using Stripping Voltammetry. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 310, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasova, V.A. Voltammetric Determination of Thallium(I) at a Mechanically Renewed Bi-Graphite Electrode. J. Anal. Chem. 2007, 62, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gęca, I.; Ochab, M.; Korolczuk, M. Anodic Stripping Voltammetry of Tl(I) Determination with the Use of a Solid Bismuth Microelectrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 086506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrowski, A.; Putek, M.; Zarebski, J. Antimony Film Electrode Prepared In Situ in Hydrogen Potassium Tartrate in Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Trace Detection of Cd(II), Pb(II), Zn(II), Tl(I), In(III) and Cu(II). Electroanalysis 2012, 24, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spano, N.; Panzanelli, A.; Piu, P.C.; Pilo, M.I.; Sanna, G.; Seeber, R.; Tapparo, A. Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Traces and Ultratraces of Thallium at a Graphite Microelectrode: Method Development and Application to Environmental Waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 553, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri-Majd, M.; Taher, M.A.; Fazelirad, H. Synthesis and Application of Nano-Sized Ionic Imprinted Polymer for the Selective Voltammetric Determination of Thallium. Talanta 2015, 144, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, S.; Taher, M.A.; Fazelirad, H. Voltammetric Sensing of Thallium at a Carbon Paste Electrode Modified with a Crown Ether. Microchim. Acta 2013, 180, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezi, N.; Kokkinos, C.; Economou, A.; Prodromidis, M.I. Voltammetric Determination of Trace Tl(I) at Disposable Screen-Printed Electrodes Modified with Bismuth Precursor Compounds. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 182, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domańska, K.; Tyszczuk-Rotko, K. Integrated Three-Electrode Screen-Printed Sensor Modified with Bismuth Film for Voltammetric Determination of Thallium(I) at the Ultratrace Level. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1036, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenthaler, H.; Jüttner, K.; Schmidt, E.; Lorenz, W.J. Voltammetric Investigation of Thallium Adsorption on Silver Single Crystal Electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 1978, 23, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfil, Y.; Brand, M.; Kirowa-Eisner, E. Characteristics of Subtractive Anodic Stripping Voltammetry of Lead, Cadmium and Thallium at Silver-Gold Alloy Electrodes. Electroanalysis 2003, 15, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnodȩbska-Ostrȩga, B.; Pałdyna, J.; Golimowski, J. Determination of Thallium at A Silver-Gold Alloy Electrode by Voltammetric Methods in Plant Material and Bottom Sediment Containing Cd and Pb. Electroanalysis 2007, 19, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolczuk, M.; Ochab, M.; Gęca, I. Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Procedure of Thallium(I) Determination by Means of a Bismuth-Plated Gold-Based Microelectrode Array. Sensors 2024, 24, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrzejewska-Sikorska, A.; Konował, E.; Karbowska, B.; Szatkowska, D. New Electrode Material GCE/AgNPs-D3 as an Electrochemical Sensor Used for the Detection of Thallium Ions. Electroanalysis 2023, 35, e202200281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochab, A.; Saxena, M.; Jindal, K.; Tomar, M.; Gupta, V.; Saxena, R. Thiol-Functionalized Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes for Electrochemical Sensing of Thallium. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 259, 124068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Stueben, D.; Berner, Z. The Application of Microelectrodes for the Measurements of Trace Metals in Water. Anal. Lett. 2005, 38, 2281–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, G.M.S.; Magalhães, J.M.C.S.; Soares, H.M.V.M. Simultaneous Determination of Nickel and Cobalt Using a Solid Bismuth Vibrating Electrode by Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry. Electroanalysis 2013, 25, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gęca, I.; Ochab, M.; Robak, A.; Mergo, P.; Korolczuk, M. Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Se(IV) by Means of a Novel Reusable Gold Microelectrodes Array. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 286, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Schmidt, M.A.; Russell, R.F.; Joly, N.Y.; Tyagi, H.K.; Uebel, P.; Russell, P.S.J. Pressure-Assisted Melt-Filling and Optical Characterization of Au Nano-Wires in Microstructured Fibers. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 12189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacanovska, A.; Rong, Z.; Schmidt, M.; Russell, P.S.J.; Vadgama, P. Bio-Sensing Using Recessed Gold-Filled Capillary Amperometric Electrodes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.A.; Prill Sempere, L.N.; Tyagi, H.K.; Poulton, C.G.; Russell, P.S.J. Waveguiding and Plasmon Resonances in Two-Dimensional Photonic Lattices of Gold and Silver Nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 033417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewket, K.; Janphuang, P.; Laohana, P.; Tanapongpisit, N.; Saenrang, W.; Ngamchuea, K. Silver Microelectrode Arrays for Direct Analysis of Hydrogen Peroxide in Low Ionic Strength Samples. Electroanalysis 2023, 35, e202200200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, D.; Lee, Y. Highly Conductive and Flexible Silver Nanowire-Based Microelectrodes on Biocompatible Hydrogel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 18401–18407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Gu, Z.; Si, W. Silver Nanoparticle-Decorated Carbon Fiber Microelectrode for Imidacloprid Insecticide Analysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 047506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; Wei, Y.; Liau, W.J.; Yang, H.; Du, H. Preparing of Interdigitated Microelectrode Arrays for AC Electrokinetic Devices Using Inkjet Printing of Silver Nanoparticles Ink. Micromachines 2017, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Working Electrode | Deposition Time [s] | Linear Range [nmol L−1] | Detection Limit [nmol L−1] | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFE | 600 | 1–500 | 0.5 | - | [13] |

| BiFE | 120 | 12–150 | 10.8 | rotating disc | [14] |

| BiFE | 240 | 49–391 | 2.9 | disposability, microfabrication | [15] |

| BiABE | 60 | 0.5–49 | 0.005 | - | [16] |

| Bi-graphite electrode | 600 | 49–4900 | 4.9 | mechanically renewed electrode | [17] |

| BiµE | 120 | 2–200 | 0.83 | solid metal microelectrode | [18] |

| SbFE | 120 | 9.8–489 | 4.9 | - | [19] |

| Graphite µE | 300 | 24–1712 | 0.049 | - | [20] |

| Modified CPE | 300 | 15–1220 | 4.2 | modified with crown ether | [22] |

| BiF/SPE | 60 | 5–1000 | 0.847 | integrated three-electrode sensor | [24] |

| BiF/AuµE | 120 | 0.5–500 | 0.22 | - | [28] |

| GCE/AgNPs-D3 | 120 | 49–490 | 35 | modified GCE | [29] |

| AgµE | 120 | 0.5–100 | 0.135 | unmodified electrode | [this work] |

| Foreign Ion | Molar Excess of Foreign Ion | Relative Tl Signal [I/I0] 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Ga(III) | 100 | 1.03 |

| Mn(II) | 100 | 0.99 |

| Co(II) | 100 | 1.02 |

| Ni(II) | 100 | 1.04 |

| Cd(II) | 100 | 0.95 |

| Pb(II) | 50 | 0.92 |

| 100 | 0.72 | |

| Cu(II) | 20 | 0.93 |

| 50 | 0.69 | |

| Zn(II) | 100 | 0.94 |

| Fe(III) | 100 | 0.95 |

| In(III) | 100 | 1.04 |

| Certified Reference Material | Determined Value ± SD [µg·L−1] | Certified Value ± SD [µg·L−1] | Recovery [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| TM 25.5 | 29.1 ± 1.1 | 30.0 ± 2.8 | 97.0 |

| TM 26.5 | 5.7 ± 0.45 | 5.41 ± 0.42 | 105.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korolczuk, M.; Ochab, M.; Gęca, I. Application of a Novel Solid Silver Microelectrode Array for Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Thallium(I). Molecules 2025, 30, 4220. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214220

Korolczuk M, Ochab M, Gęca I. Application of a Novel Solid Silver Microelectrode Array for Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Thallium(I). Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4220. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214220

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorolczuk, Mieczyslaw, Mateusz Ochab, and Iwona Gęca. 2025. "Application of a Novel Solid Silver Microelectrode Array for Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Thallium(I)" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4220. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214220

APA StyleKorolczuk, M., Ochab, M., & Gęca, I. (2025). Application of a Novel Solid Silver Microelectrode Array for Anodic Stripping Voltammetric Determination of Thallium(I). Molecules, 30(21), 4220. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214220