The Selectivity of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Revisited

Abstract

1. Introduction

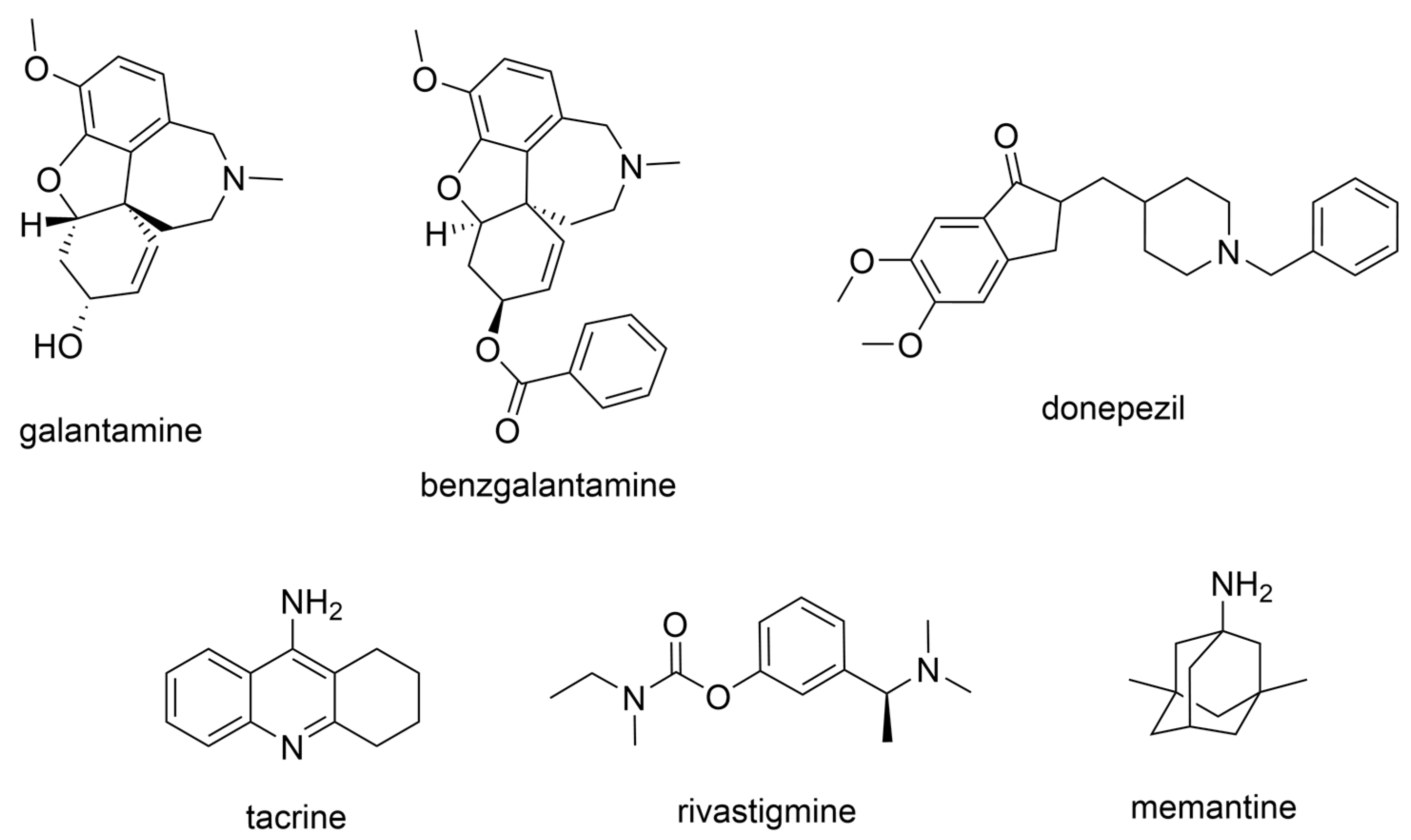

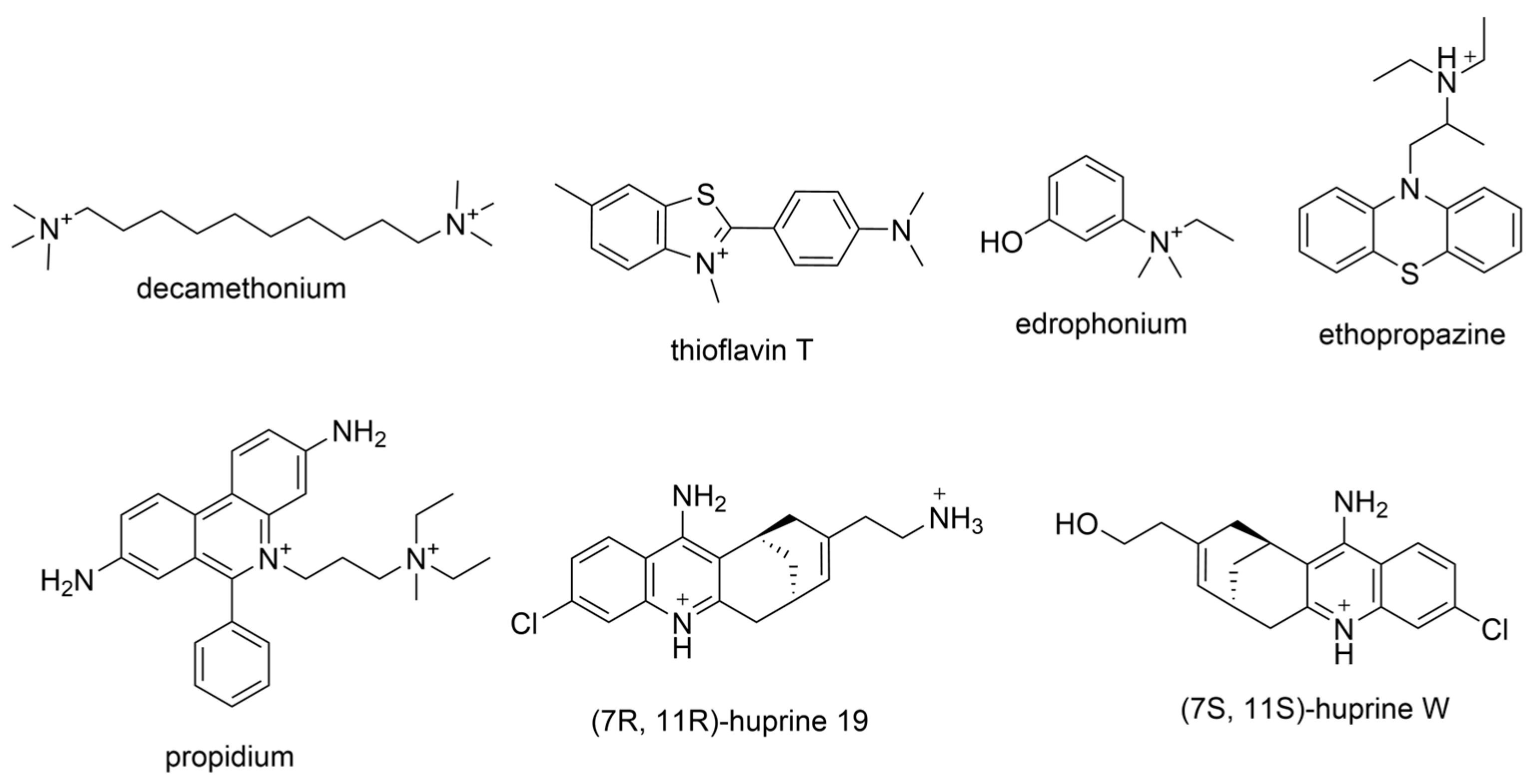

2. Approved Therapeutics and Cholinesterase Selectivity

2.1. FDA-Approved Anti-AD Drugs

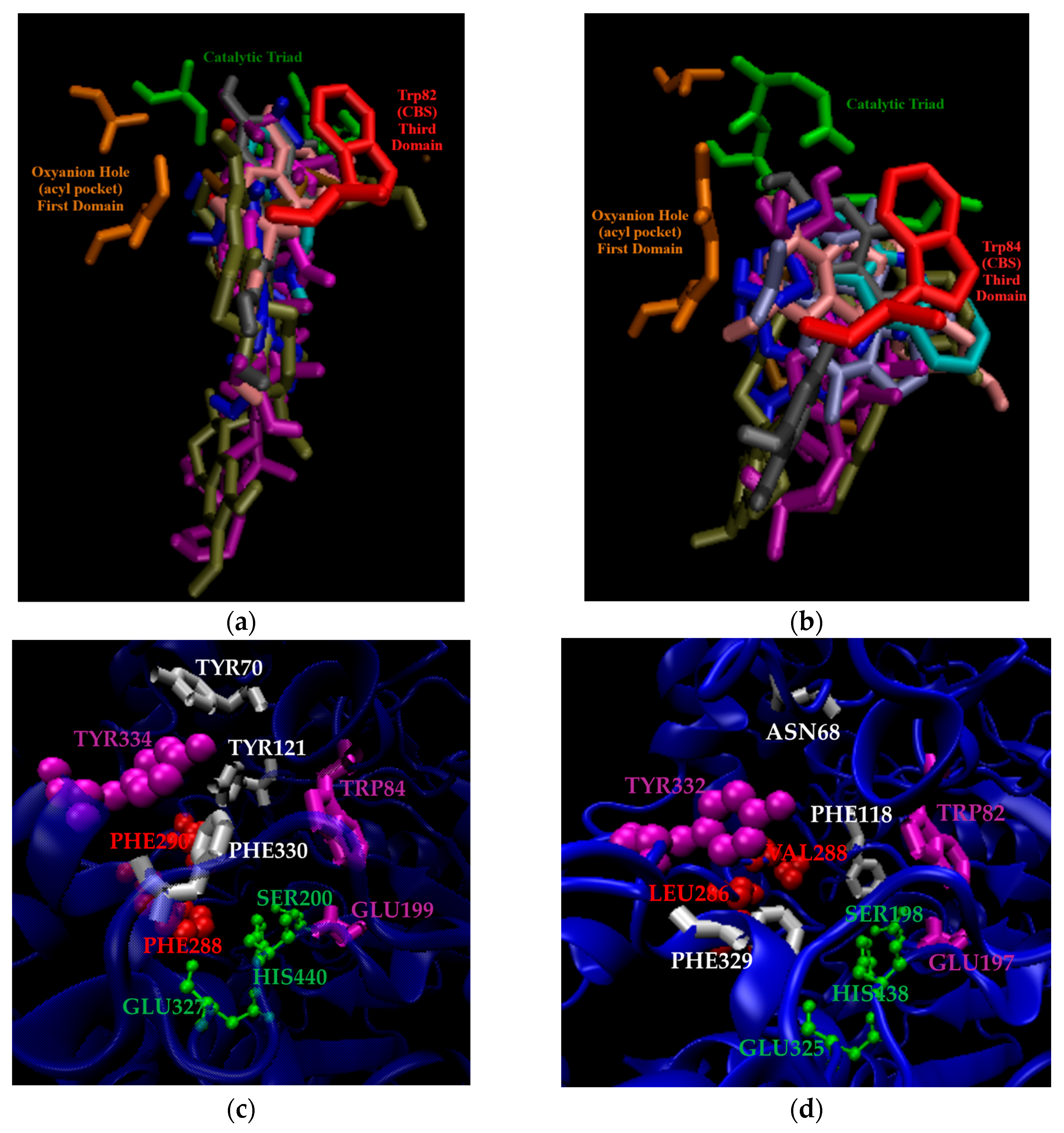

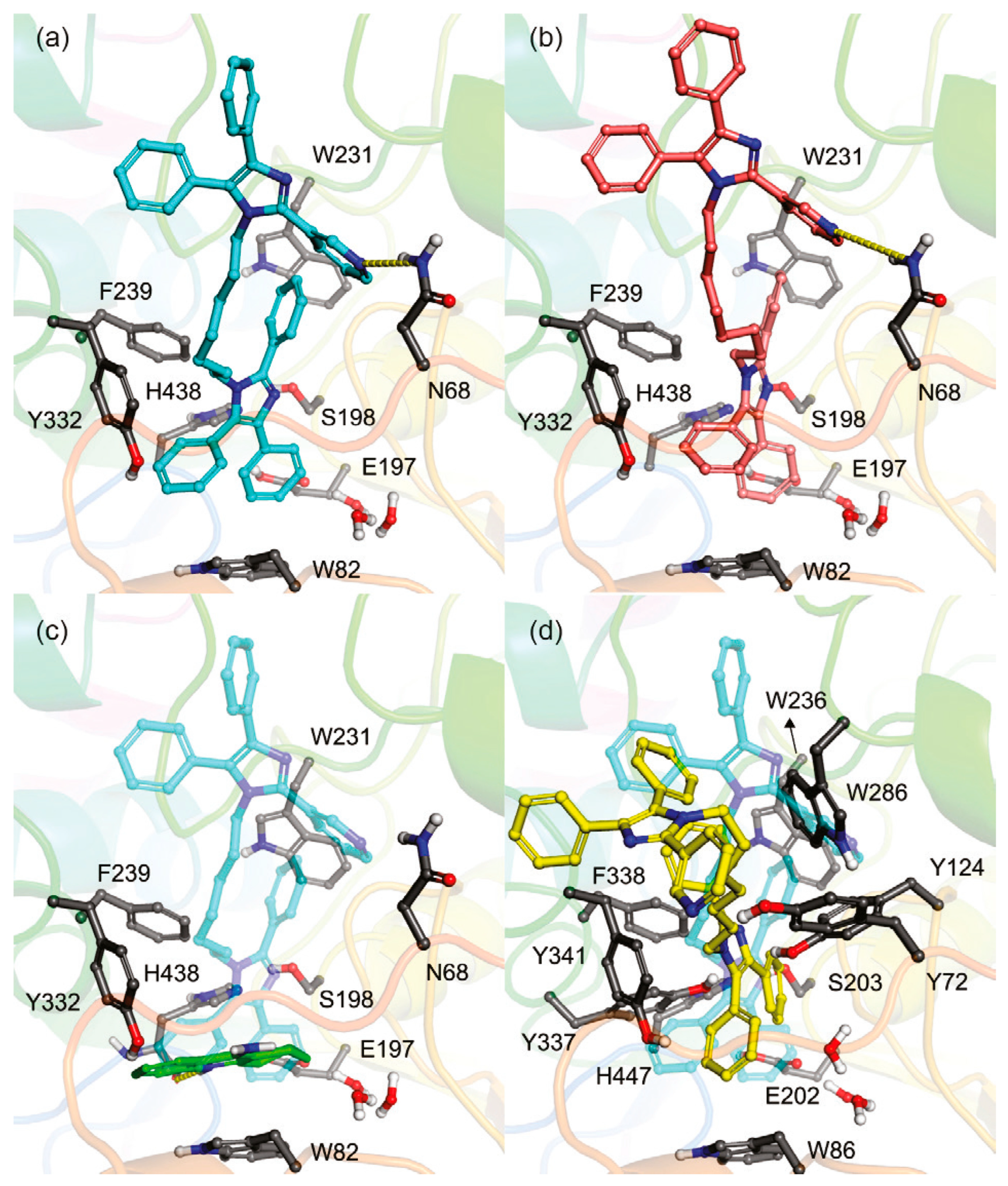

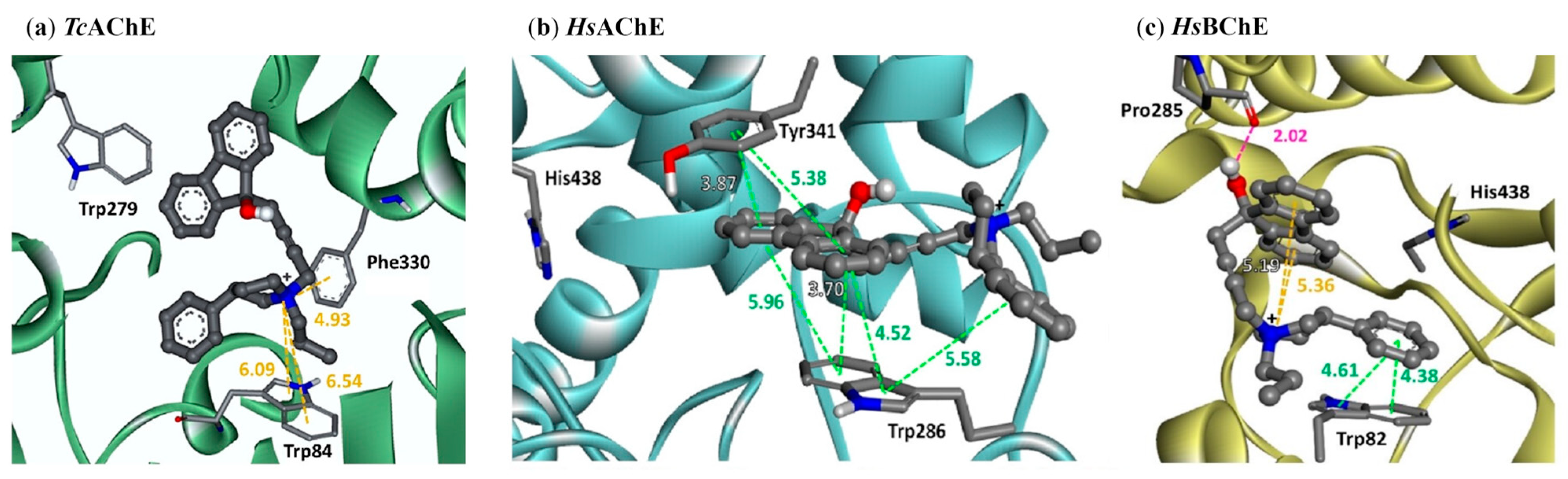

2.2. The Three Domains of ChE Selectivity

2.3. Additional ChE Selectivity Considerations

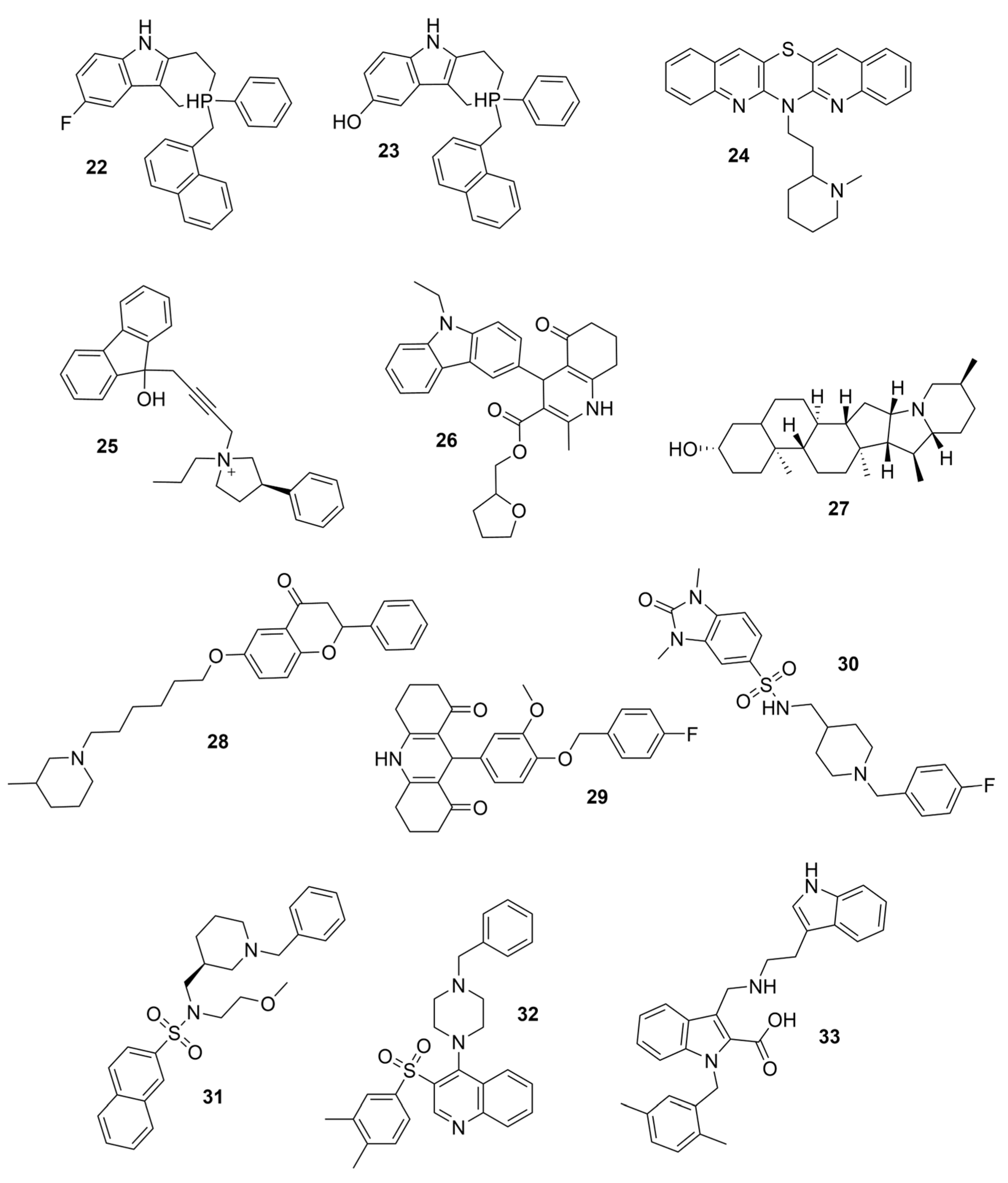

3. Selective BChE Inhibitors from Traditional Methods

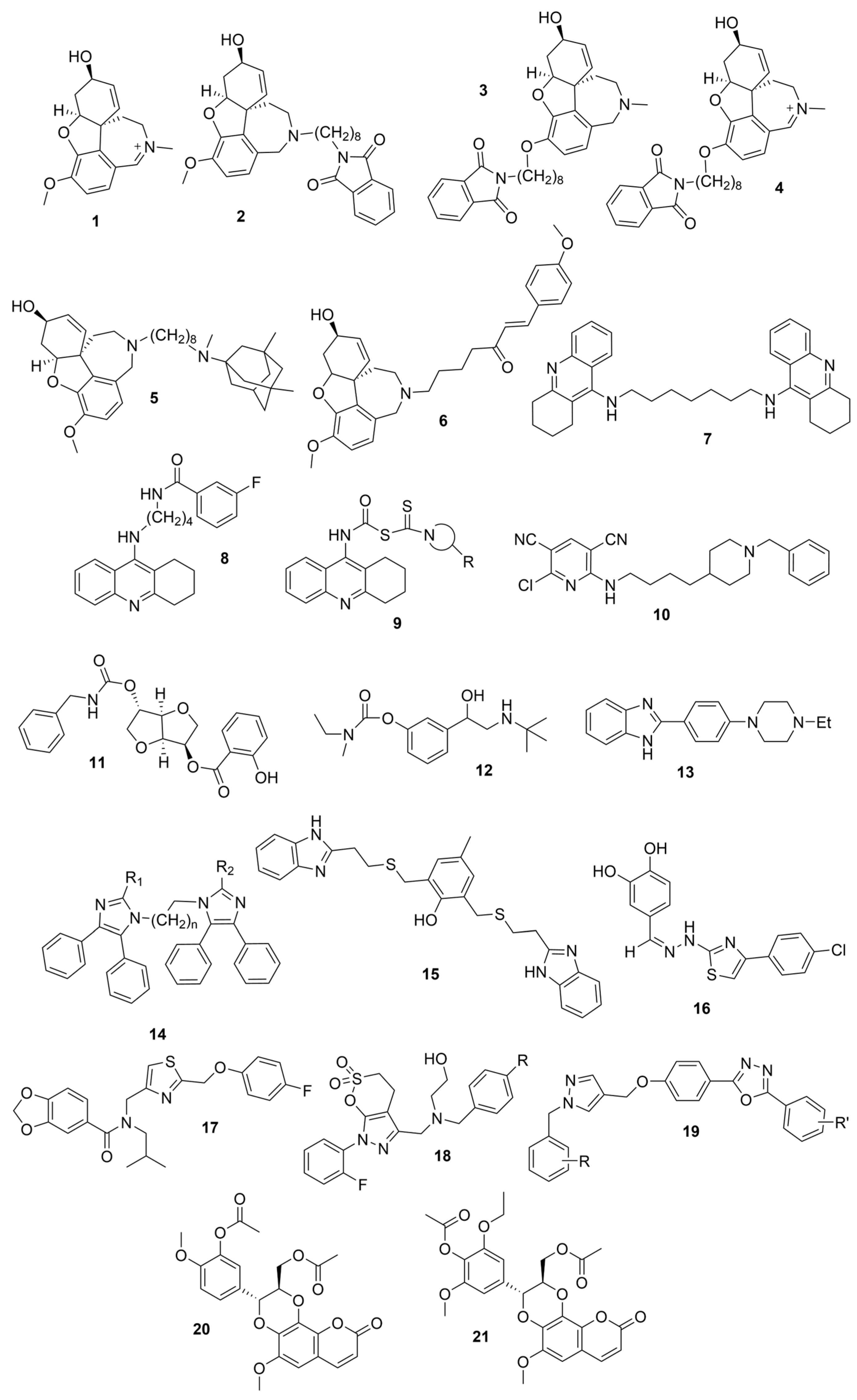

3.1. Derivatives of Galantamine (GNT), Donepezil, Tacrine, and Rivastigmine

3.2. Derivatives from Imidazole, Thiazole, and Other Pharmacophores

4. Selective BChE Inhibitors from Virtual Screening

4.1. Structure-Based Virtual Screening

4.2. Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS)

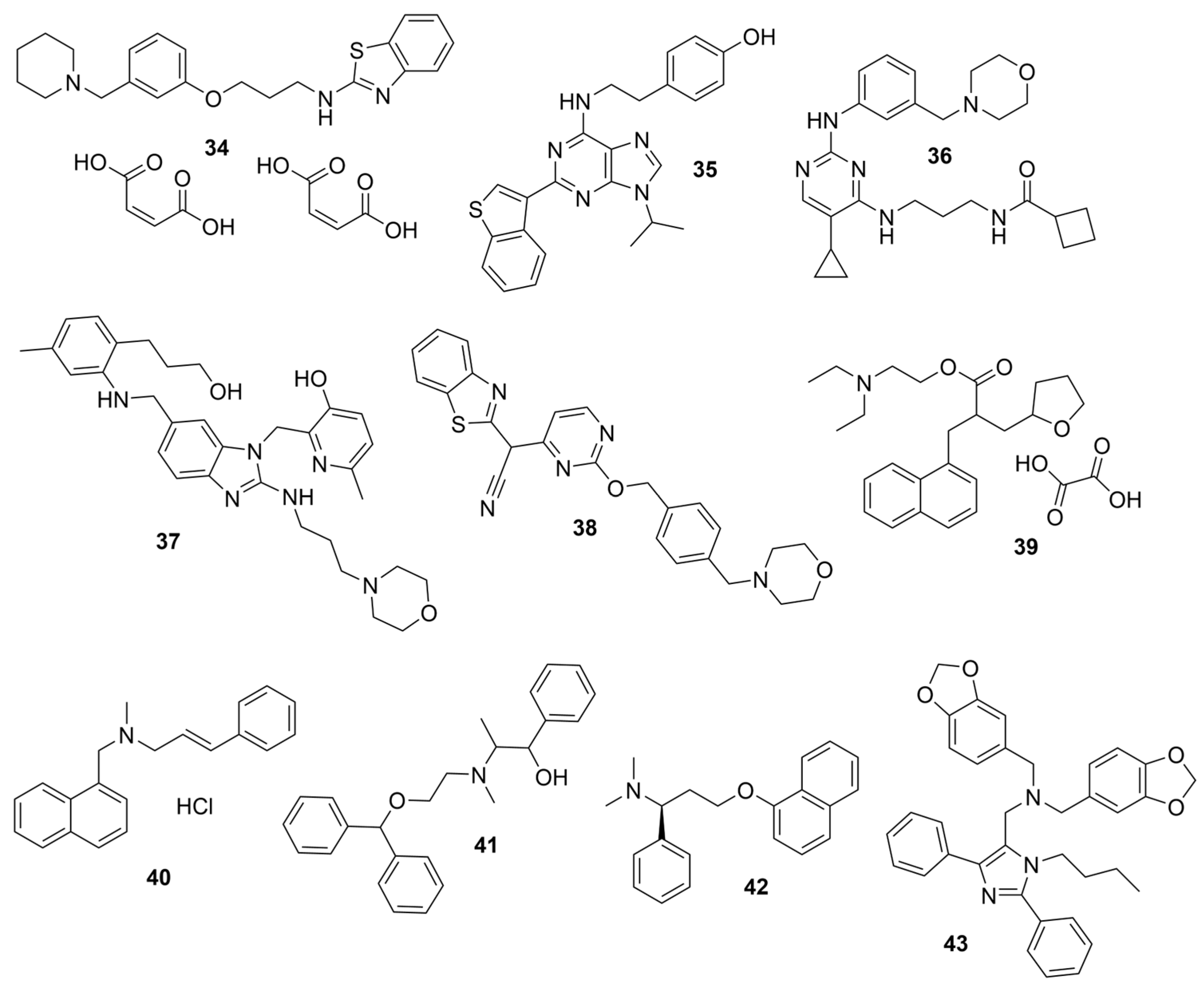

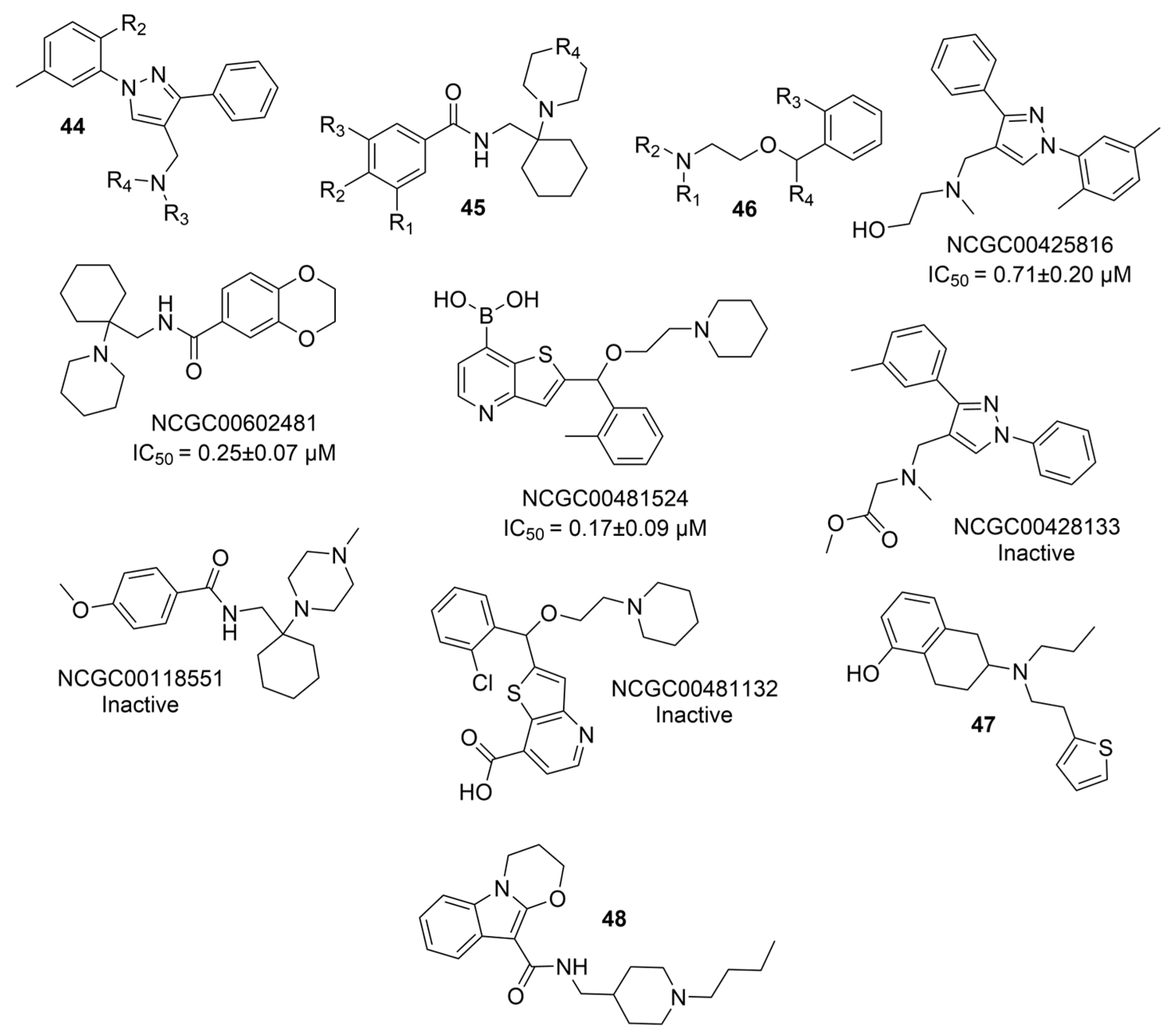

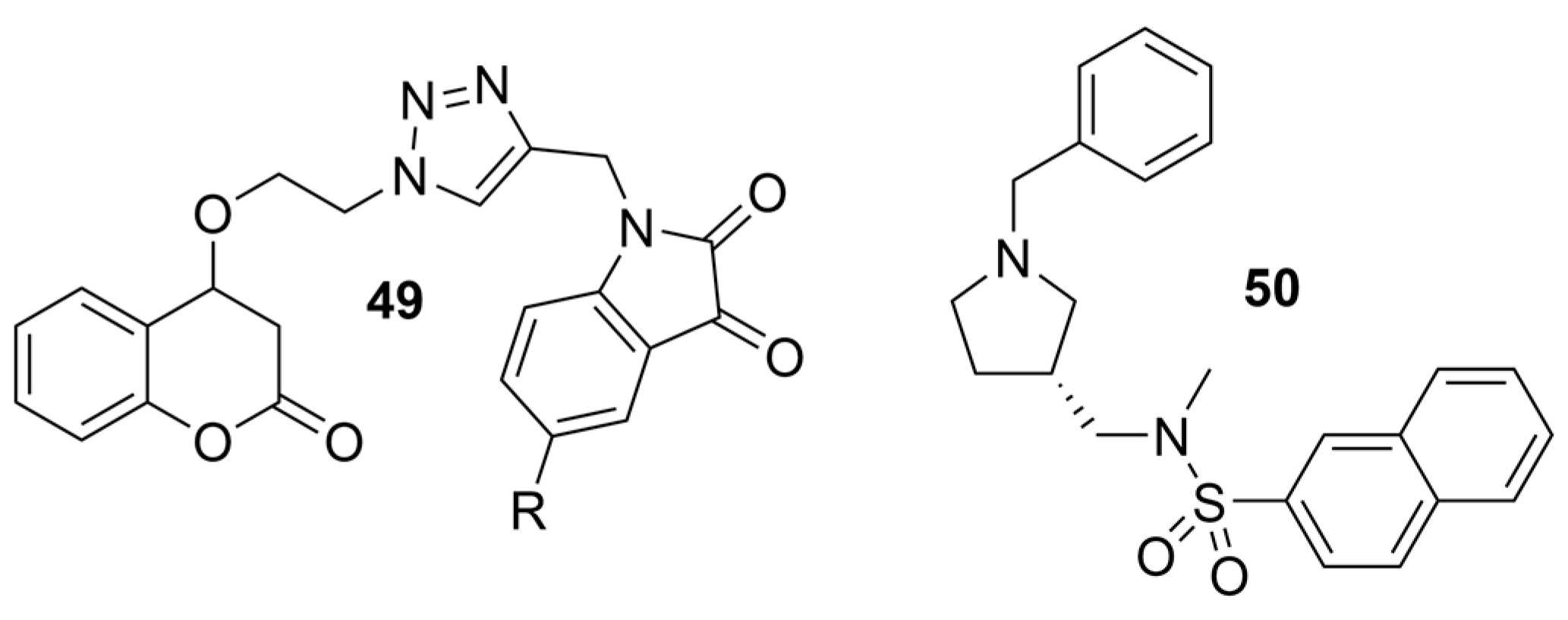

5. Selective BChE Inhibitors from qHTS and ML

5.1. Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS)

5.2. Machine Learning Models

6. Discussion

6.1. Hits from Traditional Methods

6.2. Hits from In Silico VS Methods

6.3. Hits from qHTS and ML Models

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colović, M.B.; Krstić, D.Z.; Lazarević-Pašti, T.D.; Bondžić, A.M.; Vasić, V.M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Pharmacology and toxicology. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 11, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeri, E.; Elkhoury, K.; Morsink, M.; Broersen, K.; Linder, M.; Tamayol, A.; Malaplate, C.; Yen, F.T.; Arab-Tehrany, E. Alzheimer’s Disease: Treatment Strategies and Their Limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Sivaprakasam, P.; Vijendra, P.; Waseem, M.; Pandurangan, A.K. A Recent Update on Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Interventions of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 3428–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, G.R.; Lakshmi, G. Emerging Significance of Butyrylcholinesterase. World J. Exp. Med. 2024, 14, 87202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarpia, L.; Grandone, I.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F. Butyrylcholinesterase as a Prognostic Marker: A Review of the Literature. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2012, 4, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanka, M. Butyrylcholinesterase as a Biochemical Marker. Bratisl. Med. J. 2013, 114, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.Y.; Zhen, T.F.; Harakandi, C.H.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.C.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H.P. New Insights into Butyrylcholinesterase: Pharmaceutical Applications, Selective Inhibitors and Multitarget-Directed Ligands. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 275, 116569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greig, N.H.; Utsuki, T.; Ingram, D.K.; Wang, Y.; Pepeu, G.; Scali, C.; Yu, Q.S.; Mamczarz, J.; Holloway, H.W.; Giordano, T.; et al. Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibition elevates brain acetylcholine, augments learning and lowers Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide in rodent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 17213–17218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Available online: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/medications-for-memory (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Lilley, L.L.; Harrington, S.; Snyder, J.S. Pharmacology and the Nursing Process, 5th ed.; Mosby Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2007; pp. 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.-R.; Huang, J.-B.; Yang, S.-L.; Hong, F.-F. Role of Cholinergic Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.M.; Lounsbery, J.L. Benzgalantamine (Zunveyl) for the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Alzheimer Disease. Am. Fam. Physician 2025, 112, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, H.; Silman, I.; Harel, M.; Rosenberry, T.L.; Sussman, J.L. Acetylcholinesterase: From 3D Structure to Function. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2010, 187, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, J.; Harel, M.; Frolow, F.; Oefner, C.; Goldman, A.; Toker, L.; Silman, I. Atomic Structure of Acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo Californica: A Prototypic Acetylcholine-Binding Protein. Science 1991, 253, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, Z.; Pickering, N.A.; Vellom, D.C.; Camp, S.; Taylor, P. Three distinct domains in the cholinesterase molecule confer selectivity for acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 12074–12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H. Recent progress in the identification of selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 132, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.A.; Ross, B.P. Recent Advances in Virtual Screening for Cholinesterase Inhibitors. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewari, D.; Stankiewicz, A.M.; Mocan, A.; Sah, A.N.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Huminiecki, L.; Horbanczuk, J.O.; Atanasov, A.G. Ethnopharmacological Approaches for Dementia Therapy and Significance of Natural Products and Herbal Drugs. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvesh, S.; Walsh, R.; Kumar, R.; Caines, A.; Roberts, S.; Magee, D.; Rockwood, K.; Martin, E. Inhibition of human cholinesterases by drugs used to treat Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2003, 17, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolucci, C.; Perola, E.; Pilger, C.; Fels, G.; Lamba, D. Three-dimensional structure of a complex of galanthamine (Nivalin®) with acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: Implications for the design of new anti-Alzheimer drugs. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2001, 42, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, E.; Daniele, S.; Bottegoni, G.; Pizzirani, D.; Trincavelli, M.L.; Goldoni, L.; Tarozzo, G.; Reggiani, A.; Martini, C.; Piomelli, D.; et al. Combining Galantamine and Memantine in Multitargeted, New Chemical Entities Potentially Useful in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 9708–9721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonova, R.; Atanasova, M.; Stavrakov, G.; Philipova, I.; Doytchinova, I. Ex Vivo Antioxidant and Cholinesterase-Inhibiting Effects of a Novel Galantamine–Curcumin Hybrid on Scopolamine-Induced Neurotoxicity in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, P.R.; Han, Y.F.; Chow, E.S.H.; Li, C.P.L.; Wang, H.; Xuan Lieu, T.; Sum Wong, H.; Pang, Y.-P. Evaluation of short-tether Bis-THA AChE inhibitors. A further test of the dual binding site hypothesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, K.; Szymanski, P.; Girek, M.; Mikiciuk-Olasik, E.; Skibinski, R.; Kabziński, J.; Majsterek, I.; Malawska, B.; Jonczyk, J.; Bajda, M. Tetrahydroacridine derivatives with fluorobenzoic acid moiety as multifunctional agents for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Bioorg. Chem. 2017, 72, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, W.; Sağlık, B.N.; Levent, S.; Korkut, B.; Ilgın, S.; Özkay, Y.; Kaplancıklı, Z.A. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of New Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2018, 23, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, C.G.; Dillon, G.P.; Khan, D.; Ryder, S.A.; Gaynor, J.M.; Reidy, S.; Marquez, J.F.; Jones, M.; Holland, V.; Gilmer, J.F. Isosorbide-2-benzyl carbamate-5-salicylate, a peripheral anionic site binding subnanomolar selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Tan, Z.; Pistolozzi, M.; Tan, W. Rivastigmine–Bambuterol Hybrids as Selective Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors. Molecules 2024, 29, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, A.; de la Fuente Revenga, M.; Perez, C.; Iriepa, I.; Moraleda, I.; Rodríguez-Franco, M.I.; Marco-Contelles, J. Synthesis, pharmacological assessment, and molecular modeling of 6 chloro-pyridonepezils: New dual AChE inhibitors as potential drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 67, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozadali-Sari, K.; Küçükkýlýnç, T.T.; Ayazgok, B.; Balkan, A.; Unsal-Tan, O. Novel multi-targeted agents for Alzheimer’s disease: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling of novel 2-[4-(4- substitutedpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl] benzimidazoles. Bioorg. Chem. 2017, 72, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

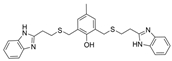

- Camara, V.S.; Soares, A.J.; Biscussi, B.; Murray, A.P.; Guedes, I.A.; Dardenne, L.E.; Ruaro, T.C.; Zimmer, A.R.; Ceschi, M.A. Expedient microwave-assisted synthesis of bis(n)-lophine analogues as selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors: Cytotoxicity evaluation and molecular modelling. J. Brazil. Chem. Soc. 2021, 32, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Zhou, S.; Zhan, C.-G. Discovery of potent and selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors through the use of pharmacophore-based screening. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 126754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

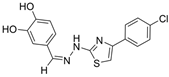

- Rahim, F.; Javed, M.T.; Ullah, H.; Wadood, A.; Taha, M.; Ashraf, M.; Aine, Q.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, F.; Mirza, S.; et al. Synthesis, molecular docking, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory potential of thiazole analogs as new inhibitors for Alzheimer disease. Bioorg. Chem. 2015, 62, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

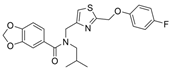

- Xi, M.; Feng, C.; Du, K.; Lv, W.; Du, C.; Shen, R.; Sun, H. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular modeling of N-isobutyl-N-((2-(p-tolyloxymethyl)thiazol-4yl)methyl)benzo[d][1,3] dioxole-5-carboxamides as selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 61, 128602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

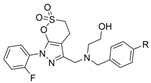

- Zhang, Z.; Min, J.; Chen, M.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Y.; Qin, H.; Tang, W. The structure-based optimization of δ-sultone-fused pyrazoles as selective BuChE inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 201, 112273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

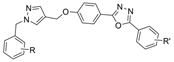

- Iraji, A.; Hariri, R.; Hashempur, M.H.; Ghasemi, M.; Pourtaher, H.; Saeedi, M.; Akbarzadeh, T. Design and synthesis of new 1,2,3-triazole-methoxyphenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives: Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors against Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

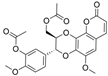

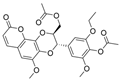

- Okpala, E.O.; Yeye, O.E.; Ogunlakin, A.D.; Eneogwe, G.O.; Gyebi, G.A.; Ojo, O.A.; Odeja, O.O.; Ibok, M.G.; Ajiboye, C.O.; Onocha, P.A.; et al. Derivatization and Anti-Butyrylcholinesterase Activity of Coumarinolignans: Experimental and Computational Approaches. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

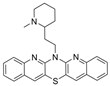

- Lodarski, K.; Jonczyk, J.; Guzior, N.; Bajda, M.; Gladysz, J.; Walczyk, J.; Jelen, M.; Morak-Mlodawska, B.; Pluta, K.; Malawska, B. Discovery of butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors among derivatives of azaphenothiazines. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2015, 30, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nogara, P.A.; Saraiva, R.d.A.; Caeran Bueno, D.; Lissner, L.J.; Lenz Dalla Corte, C.; Braga, M.M.; Rosemberg, D.B.; Rocha, J.B.T. Virtual Screening of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors Using the Lipinski’s Rule of Five and ZINC Databank. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 870389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dighe, S.N.; Deora, G.S.; De la Mora, E.; Nachon, F.; Chan, S.; Parat, M.-O.; Brazzolotto, X.; Ross, B.P. Discovery and Structure−Activity Relationships of a Highly Selective Butyrylcholi nesterase Inhibitor by Structure-Based Virtual Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 7683–7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, F.; Zhan, C.-G. Structure-based virtual screening leading to discovery of highly selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors with solanaceous alkaloid scaffolds. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2019, 308, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajda, M.; Łazewska, D.; Godyn, J.; Zaręba, P.; Kuder, K.; Hagenow, S.; Łątka, K.; Stawarska, E.; Stark, H.; Kiec-Kononowicz, K.; et al. Search for new multi-target compounds against Alzheimer’s disease among histamine H3 receptor ligands. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 185, 111785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, J.; Kapp, E. Discovery of 9-phenyl acridinediones as highly selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors through structure-based virtual screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, H.; Yang, H.; Tan, R.; Bian, Y.; Fu, T.; Li, W.; Wu, L.; Pei, Y.; Sun, H. Discovery of new acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors through structure-based virtual screening. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 3429–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yang, H.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, F.; Liu, W.; Guo, Q.; Sun, H. Expansion of the scaffold diversity for the development of highly selective butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) inhibitors: Discovery of new hits through the pharmacophore model generation, virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 85, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Du, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, T.; Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Feng, F.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, H. Discovery, molecular dynamic simulation and biological evaluation of structurally diverse cholinesterase inhibitors with new scaffold through shape-based pharmacophore virtual screening. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 92, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Z.; Li, A.J.; Travers, J.; Xu, T.; Sakamuru, S.; Klumpp-Thomas, C.; Huang, R.L.; Xia, M.H. Identification of Compounds for Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibition. SLAS Discov. 2021, 26, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Li, S.Z.; Li, A.J.; Zhao, J.H.; Sakamuru, S.; Huang, W.W.; Xia, M.H.; Huang, R.L. Identification of Potent and SelectiveAcetylcholinesterase/Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors by Virtual Screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 2321–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, P.; Yang, C.; Yin, Q.; Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Discovery, Biological Evaluation and Binding Mode Investigation of Novel Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Through Hybrid Virtual Screening. Molecules 2025, 30, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkovski, A.; Dobričić, V.; Simić, M.R.; Jurhar Pavlova, M.; Mihajloska, E.; Sterjev, Z.; Poceva Panovska, A. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Molecular Docking Studies of Novel Coumarin–Triazole–Isatin Hybrids as Selective Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors. Molecules 2025, 30, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košak, U.; Strašek Benedik, N.; Knez, D.; Žakelj, S.; Trontelj, J.; Pišlar, A.; Horvat, S.; Bolje, A.; Žnidaršič, N.; Grgurevič, N.; et al. Lead Optimization of a Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 11693–11723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutho, B.; Yanarojana, S.; Supavilai, P. Structural Dynamics and Susceptibility of Anti-Alzheimer’s Drugs Donepezil and Galantamine against Human Acetylcholinesterase. Trends Sci. 2022, 19, 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafferman, A.; Velan, B.; Ordentlich, A.; Kronman, C.; Grosfeld, H.; Leitner, M.; Flashner, Y.; Cohen, S.; Barak, D.; Ariel, N. Substrate Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase: Residues Affecting Signal Transduction from the Surface to the Catalytic Center. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3561–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, L.F.; Gnatt, A.; Loewenstein, Y.; Seidman, S.; Ehrlich, G.; Soreq, H. Intramolecular Relationships in Cholinesterases Revealed by Oocyte Expression of Site-Directed and Natural Variants of Human BCHE. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel, M.; Sussman, J.L.; Krejci, E.; Bon, S.; Chanal, P.; Massoulie, J.; Silman, I. Conversion of Acetylcholinesterase to Butyrylcholinesterase: Modeling and Mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10827–10831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Schalk, I.; Ehret-Sabatier, L.; Bouet, F.; Goeldner, M.; Hirth, C.; Axelsen, P.H.; Silman, I.; Sussman, J.L. Quaternary Ligand Binding to Aromatic Residues in the Active-Site Gorge of Acetylcholinesterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 9031–9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberry, T.L.; Brazzolotto, X.; Macdonald, I.R.; Wandhammer, M.; Trovaslet-Leroy, M.; Darvesh, S.; Nachon, F. Comparison of the Binding of Reversible Inhibitors to Human Butyrylcholinesterase and Acetylcholinesterase: A Crystallographic, Kinetic and Calorimetric Study. Molecules 2017, 22, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, M.D.; Wang, Y.; Pang, J. The Cholinergic Selectivity of FDA-Approved and Metabolite Compounds Examined with Molecular-Docking-Based Virtual Screening. Molecules 2024, 29, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, M.D.; Wang, Y.; Pang, J. Molecular Dynamics Studies on the Inhibition of Cholinesterases by Secondary Metabolites. Catalysts 2025, 15, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt, H.M.; Guillou, C.; Guénard, D.; Argaman, A.; Botti, S.; Badet, B.; Thal, C.; Silman, I.; Sussman, J.L. The Complex of a Bivalent Derivative of Galanthamine with Torpedo Acetylcholinesterase Displays Drastic Deformation of the Active-Site Gorge: Implications for Structure-Based Drug Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15405–15411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanova, E.; Atanasova, M.; Doytchinova, I. A Novel Galantamine–Curcumin Hybrid Inhibits Butyrylcholinesterase: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Chemistry 2024, 6, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dileep, K.V.; Ihara, K.; Mishima-Tsumagari, C.; Kukimoto-Niino, M.; Yonemochi, M.; Hanada, K.; Shirouzu, M.; Zhang, K.Y.J. Crystal structure of human acetylcholinesterase in complex with tacrine: Implications for drug discovery. Int. J. Bio. Macromol. 2022, 210, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachon, F.; Carletti, E.; Ronco, C.; Trovaslet, M.; Nicolet, Y.; Jean, L.; Renard, P.-Y. Crystal structures of human cholinesterases in complex with huprine W and tacrine: Elements of specificity for anti-Alzheimer’s drugs targeting acetyl- and butyryl-cholinesterase. Biochem. J. 2013, 453, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajda, M.; Jonczyk, J.; Malawska, B.; Czarnecka, K.; Girek, M.; Olszewska, P.; Sikora, J.; Mikiciuk-Olasik, E.; Skibi’nski, R.; Gumieniczek, A.; et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular modeling of new tetrahydroacridine derivatives as potential multifunctional agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 5610–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, R.; Okamura, N.; Furumoto, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Arai, H.; Yanai, K.; Kudo, Y. Use of a benzimidazole derivative BF-188 in fluorescence multispectralimaging for selective visualization of tau protein fibrils in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2014, 16, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Huang, G.L. The biological activities of butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.-S.; Ge, Y.-X.; Cheng, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Tao, H.-R.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, H. Discovery of New Selective Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) Inhibitors with Anti-Aβ Aggregation Activity: Structure-Based Virtual Screening, Hit Optimization and Biological Evaluation. Molecules 2019, 24, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.A.; Kapure, J.S.; Girdhar Singh, D.; Courageux, C.; Alexandre, I.; Dias, J.; McGeary, R.P.; Brazzolotto, X.; Ross, B.P. Rapid Discovery of a Selective Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitor Using Structure-Based Virtual Screening. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lu, X.; Yang, H.; Li, Q.; Du, C.; Chen, Y.; Hong, K.H.; Sun, H. Discovery of a Selective 6-Hydroxy-1, 4-Diazepan-2-One Containing Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitor by Virtual Screening and MM-GBSA Rescoring. Dose-Response 2020, 18, 155932582093852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Tang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; et al. Discovery of Selective Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) Inhibitors through a Combination of Computational Studies and Biological Evaluations. Molecules 2019, 24, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lešnik, S.; Štular, T.; Brus, B.; Knez, D.; Gobec, S.; Janežič, D.; Konc, J. LiSiCA: A Software for Ligand-Based Virtual Screening and Its Application for the Discovery of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Han, C.; Feng, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y. Discovery, Biological Evaluation and Molecular Dynamic Simulations of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors through Structure-Based Pharmacophore Virtual Screening. Future Med. Chem. 2021, 13, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglese, J.; Auld, D.S.; Jadhav, A.; Johnson, R.L.; Simeonov, A.; Yasgar, A.; Zheng, W.; Austin, C.P. Quantitative High-Throughput Screening: A Titration-Based Approach That Efficiently Identifies Biological Activities in Large Chemical Libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11473–11478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnecke, V.; Boström, J. Computational Chemistry-Driven Decision Making in Lead Generation. Drug Discov. Today 2006, 11, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Akotkar, L.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, D.; Ganeshpurkar, A. Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening and Molecular Modelling Studies for Identification of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors as Anti-Alzheimer’s Agent. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 42, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Singh, R.; Kumar, D.; Gutti, G.; Gore, P.; Sahu, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.K. Identification of Sulfonamide-Based Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Using Machine Learning. Future Med. Chem. 2022, 14, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.K.; Bhardwaj, B.; Waiker, D.K.; Tripathi, A.; Shrivastava, S.K. Discovery of Novel Dual Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Using Machine Learning and Structure-Based Drug Design. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1286, 135517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozalp, M.K.; Vignaux, P.A.; Puhl, A.C.; Lane, T.R.; Urbina, F.; Ekins, S. Sequential Contrastive and Deep Learning Models to Identify Selective Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 3161–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, H.; Abchir, O.; Mounadi, N.; Samadi, A.; Salah, B.; Chtita, S. Exploration of natural products for the development of promising cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyebi, G.A.; Ejoh, J.C.; Ogunyemi, O.M.; Afolabi, S.O.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Anyanwu, G.O.; Olorundare, O.E.; Adebayo, J.O.; Koketsu, M. Cholinergic Inhibition and Antioxidant Potential of Gongronema latifolium Benth Leaf in Neurodegeneration: Experimental and In Silico Study. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güçlü, G; Tüzün, B. ; Uçar, E.; Eruygur, N.; Ataş, M.; İnanır, M.; Uskutoğlu, T.; Şenkal, B.C. Phytochemical and Biological Activity Evaluation of Globularia orientalis L. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 42, 2479–2495. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, R.; Paliwal, D.; Thakur, A.; Kaushik, N. An Insight into the Recent Advancement in Anti-Alzheimer’s Potential of Indole Derivatives and their SAR Study. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 2848–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.; Singh, R.; Mehta, V.; Paliwal, D. Role of Pyrazole Moiety in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Various Synthetic Routes and Probable Mechanisms of Action. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202500130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, F. Recent Studies on Heterocyclic Cholinesterase Inhibitors Against Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Biodivers 2025, 22, e202402837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, A.; Kaya, B.; Yıldız, M.T.; Erçetin, T.; Acar Çevik, U. Design, synthesis and evaluation of thiazole derivatives as cholinesterase inhibitors and antioxidant agents. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2025, 200, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Shamim, S.; Salar, U.; Taslimi, P.; Saad, S.M.; Taskin-Tok, T.; Taha, M.; Khan, K.M. 2-amino-6-ethoxy-4-arylpyridine-3, 5-dicarbonitrile Scaffolds as potential acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321, 139863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulkhair, H.S.; El-Adl, K. A decade of research effort in synthesis, biological activity assessments, and mechanistic investigations of sulfamethazine-incorporating molecules. Arch. Pharm. 2025, 358, e2500033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baidya, A.T.; Dante, D.; Das, B.; Wang, L.; Darreh-Shori, T.; Kumar, R. Discovery and characterization of novel pyridone and furan substituted ligands of choline acetyltransferase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 998, 177638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandy, A.T.; Venkatesan, R.; Mohan, D.; Chadapullykolumbu Ismail, S.; Jupudi, S.; Selvaraj, D. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors from Carbamate and Benzo-fused Heterocyclic Scaffolds: Promising Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease. Med. Chem. Res. 2025, 34, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mołdoch, J.; Agacka-Mołdoch, M.; Jóźwiak, G.; Wojtunik-Kulesza, K. Biological Activity of Monoterpene-Based Scaffolds: A Natural Toolbox for Drug Discovery. Molecules 2025, 30, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Cuadrado, E.; Rojas-Pena, C.; Acosta-Quiroga, K.; Camargo-Ayala, L.; Rodríguez-Núnez, Y.A.; Osorio, E.; López, J.J.; Brid-Cuadrado, R.; Gutierrez, M. Exploring Pyridinium-Based Inhibitors of Cholinesterases: A Review of Synthesis, Efficacy, and Structural Insights. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2025, 14, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Yu, H.; Xian, M.; Qu, C.; Guo, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, Z.; Xiao, J. Preparation of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Peptides from Yellowfin Tuna Pancreas Using Moderate Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzu, B.; Alagoz, M.A.; Demir, Y.; Gulcin, I.; Burmaoglu, S.; Algul, O. Structure-based inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase with 2-Aryl-6-carboxamide benzoxazole derivatives: Synthesis, enzymatic assay, and in silico studies. Mol. Divers. 2025, 29, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunç, T.; Kılınç, N.; Demirel, N.; Alım, Z. Chiral Anthranilic Amides as Potential Cholinesterase Inhibitors: Synthesis, Bioactivity Assessment, and Molecular Modeling. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, e00974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takomthong, P.; Waiwut, P.; Boonyarat, C. Targeting multiple pathways with virtual screening to identify the multi-target agent for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des. 2025, 39, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldahshan, O.A.; El Hassab, M.A.; Zengin, G.; Aly, S.H. GC/MS analysis, in vitro antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory activities of the n-hexane extract of Gmelina philippensis CHAM and in silico molecular docking of its major bioactive compounds. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumontri, S.; Eiamart, W.; Tadtong, S.; Samee, W. Utilizing ADMET Analysis and Molecular Docking to Elucidate the Neuroprotective Mechanisms of a Cannabis-Containing Herbal Remedy (Suk-Saiyasna) in Inhibiting Acetylcholinesterase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukyildirim, T.; Senol Deniz, F.S.; Tugay, O.; Salmas, R.E.; Ulutas, O.K.; Aysal, I.A.; Orhan, I.E. Chromatographic Analysis and Enzyme Inhibition Potential of Reynoutria japonica Houtt.: Computational Docking, ADME, Pharmacokinetic, and Toxicokinetic Analyses of the Major Compounds. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedraoui, M.; Guerguer, F.Z.; Errougui, A.; Chtita, S. In silico exploration of Aloe vera leaf compounds as dual AChE and BChE inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 21, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, S.A.; Rashid, U.; Fatima, N.; Ejaz, S.A.; Fayyaz, A.; Ullah, M.Z.; Saeed, A.; Khan, A.; Al Harrasi, A.; Mumtaz, A. Exploration of novel triazolo-thiadiazine hybrids of deferasirox as multi-target-directed anti-neuroinflammatory agents with structure–activity relationship (SAR): A new treatment opportunity for Alzheimer’s disease. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaif, M.S.; Sh El-Sharief, A.M.; Mohamed, Y.A.; Ammar, Y.A.; Ismail, M.A.; Aboulthana, W.M.; El-Gaby, M.S.; Ragab, A. Exploring novel of 1, 2, 4-triazolo [4, 3-a] quinoxaline sulfonamide regioisomers as anti-diabetic and anti-Alzheimer agents with in-silico molecular docking simulation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Devi, B.; Jangid, K.; Kumar, V. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening of the chromone derivatives as potential therapeutic for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2025, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmistha, D.; Prabha, M.; Siva Kiran, R.R.; Ashoka, H. Enhanced in silico QSAR-based screening of butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors using multi-feature selection and machine learning. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2025, 36, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEneny-King, A.; Osman, W.; Edginton, A.N.; Rao, P.P.N. Cytochrome P450 Binding Studies of Novel Tacrine Derivatives: Predicting the Risk of Hepatotoxicity. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 2443–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

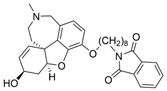

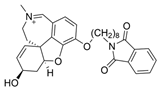

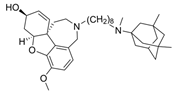

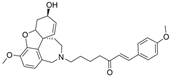

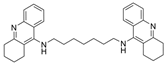

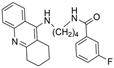

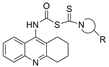

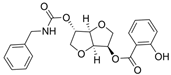

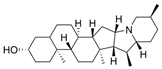

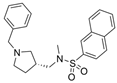

| Compounds | Structure | AChE | BChE | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| benzgalantamine |  | [12] | ||

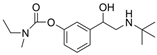

| donepezil |  | 5.7 nM a | 7.1 µM b | [17] |

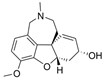

| galantamine |  | 0.36 µM a | 19 µM b | [17] |

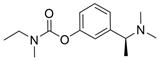

| rivastigmine |  | 48 µM a | 54 µM b | [17] |

| tacrine |  | 190 nM a | 47 nM b | [17] |

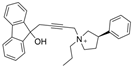

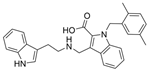

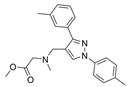

| 1 |  | 0.14 µM c | [20] | |

| 2 |  | 0.28 µM c | [20] | |

| 3 |  | 2.50 µM c | [20] | |

| 4 |  | 0.07 µM c | [20] | |

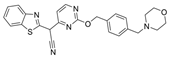

| 5 |  | 0.52 nM d | [21] | |

| 6 |  | n.a. e | n.a. e | [22] |

| 7 |  | 0.4 nM d | [23] | |

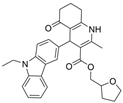

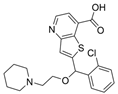

| 8 |  | 41.37 ± 5.94 nM | 1.39 ± 0.17 nM | [24] |

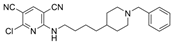

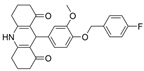

| 9 |  | 68.39 µM a | 0.014 µM a | [25] |

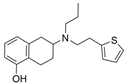

| 11 |  | >100 µM a | 0.15 nM a | [26] |

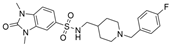

| 12 |  | >100 µM c | 0.37 ± 0.02 µM f | [27] |

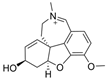

| 10 |  | 13 ± 2 nM a | 8.1 µM a | [28] |

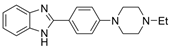

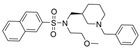

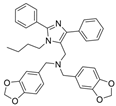

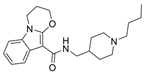

| 13 |  | 34.83 ± 1.17 µM | 5.18 ± 1.22 µM | [29] |

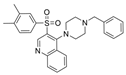

| 14 |  | Inactive c | 0.03–33.25 µM f | [30] |

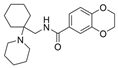

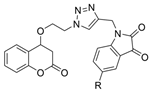

| 15 |  | >5000 nM | 32 nM | [31] |

| 22 |  | 2111 nM | 10 nM | [31] |

| 23 |  | 2604 nM | 40 nM | [31] |

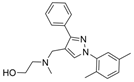

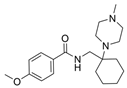

| 16 |  | 21.3 ± 0.05 µM | 1.59 ± 0.01 µM | [32] |

| 17 |  | g | 0.13 µM | [33] |

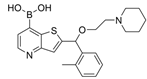

| 18 |  | >20 µM | 7.7 nM | [34] |

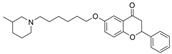

| 19 |  | >100 µM c | 11.01 µM f | [35] |

| 20 |  | 40.1 ± 0.11 µM b | [36] | |

| 21 |  | 55.4 ± 0.17 µM b | [36] | |

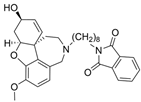

| 24 |  | h | 11.78 ± 1.31 nM | [37] |

| 25 |  | 92–762 µM | 0.75 ± 0.18 µM c | [38] |

| 26 |  | Inactive a,i | 0.443 ± 0.038 µM b | [39] |

| 27 |  | >10 µM a | 16.8 nM b | [40] |

| 28 |  | 0.36 µM a | 0.76 µM f | [41] |

| 29 |  | 125 µM a | 98 nM b | [42] |

| 30 |  | 2.05 µM | 0.031 ± 0.006 µM | [43] |

| 31 |  | >10 µM | 0.049 µM | [44] |

| 32 |  | 1.3 µM | [44] | |

| 33 |  | 10.17 µM | [45] | |

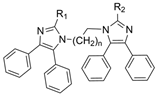

| 38 |  | Inactive | 0.33 ± 0.02 µM | [46] |

| 43 |  | Inactive | 0.21 ± 0.01 µM | [46] |

| 44a |  | 0.71 ± 0.20 µM | [47] | |

| 44b |  | Inactive | [47] | |

| 45a |  | 0.25 ± 0.07 µM | [47] | |

| 45b |  | Inactive | [47] | |

| 46a |  | 0.17 ± 0.09 µM | [47] | |

| 46b |  | Inactive | [47] | |

| 47 |  | 15.33 ± 3.83 µM f | [48] | |

| 48 |  | 12.76 ± 4.22 µM f | [48] | |

| 49 |  | 15.28 ± 1.22 µM | 1.74 ± 0.29 µM | [49] |

| 50 |  | 8.24 ± 2.31 µM a | 0.013 ± 0.002 µM b | [50] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gambardella, M.D.; Wang, Y.; Pang, J. The Selectivity of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Revisited. Molecules 2025, 30, 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214201

Gambardella MD, Wang Y, Pang J. The Selectivity of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Revisited. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214201

Chicago/Turabian StyleGambardella, Michael D., Yigui Wang, and Jiongdong Pang. 2025. "The Selectivity of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Revisited" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214201

APA StyleGambardella, M. D., Wang, Y., & Pang, J. (2025). The Selectivity of Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors Revisited. Molecules, 30(21), 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214201