Phytochemical Profiling and Anti-Obesogenic Potential of Scrophularia aestivalis Griseb. (Scrophulariaceae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

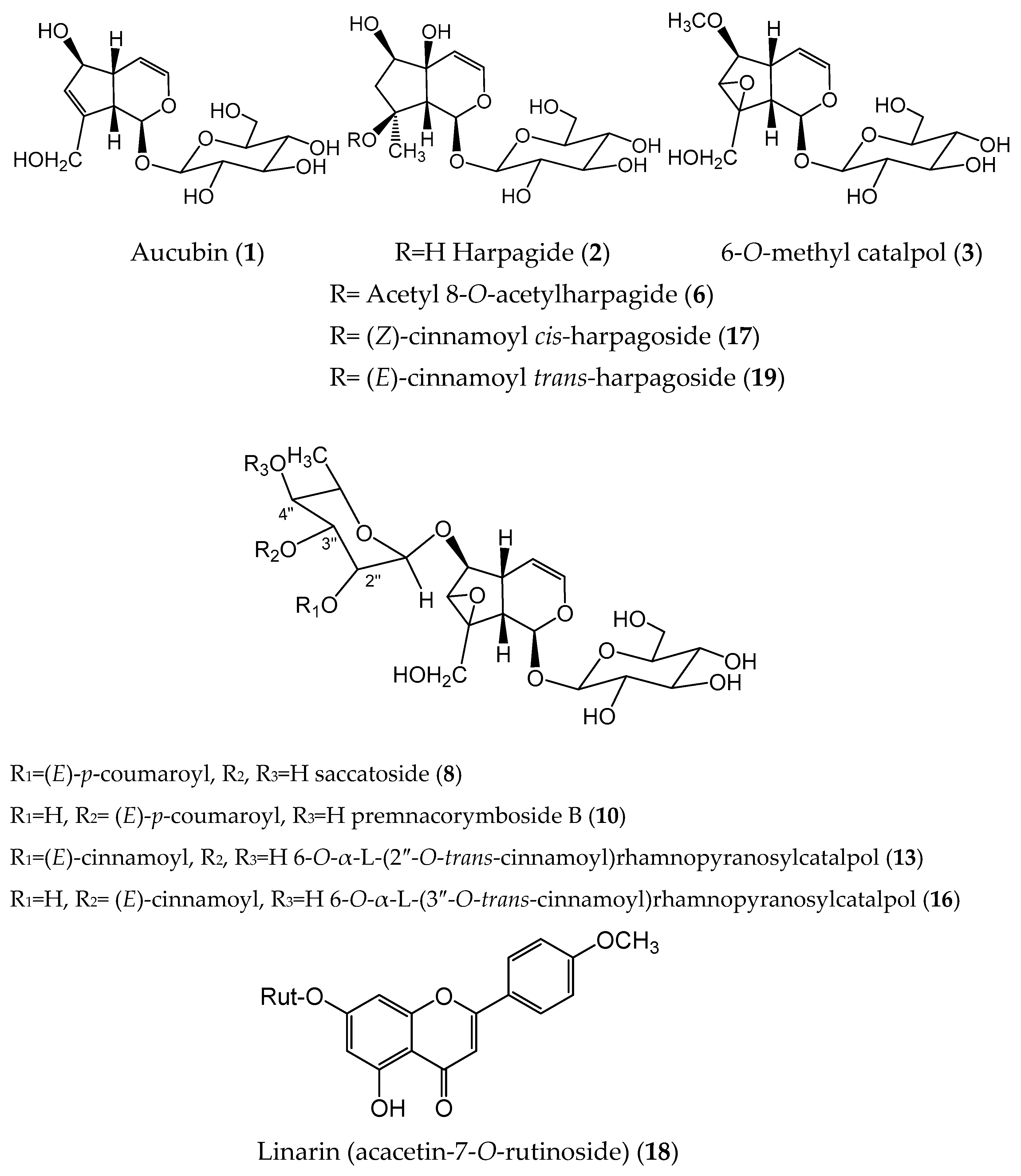

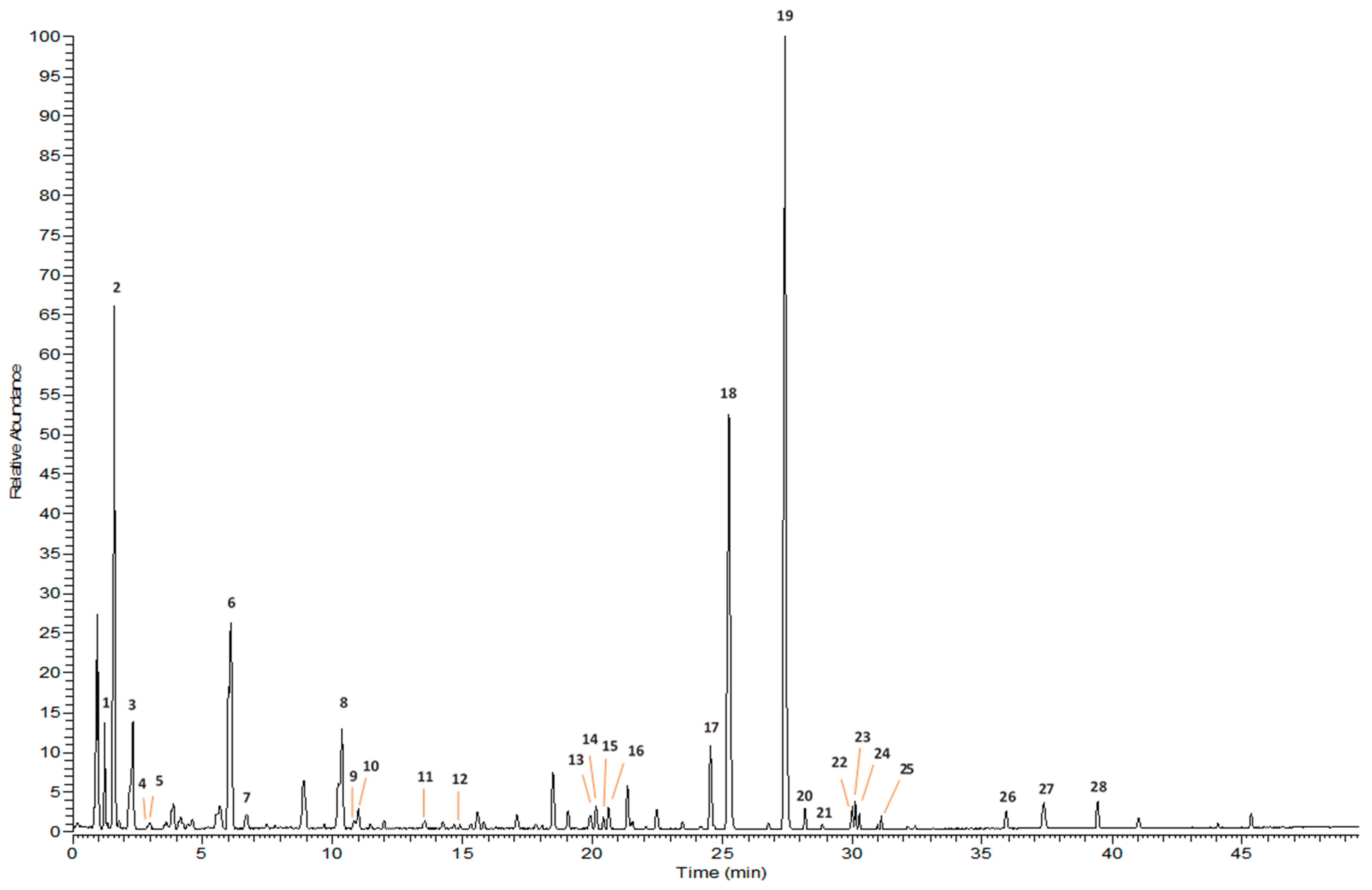

2.1. Isolation and Identification by NMR. UPLC-HRMS/MS Profiling

| No. a | Rt b, min | MF c | Exp. m/z [M-H], [M+HCOO]− | Calculated Mass | Δ Mass, ppm | MS/MS Product Ions [m/z] | Identification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.22 | C15H22O9 | 391.1246 | 346.1246 | 1.76 | 183.0656, 165.0549, 139.0549, 119.0549, 89.0229 | Aucubin | Std. |

| 2 | 1.61 | C15H24O10 | 409.1351 | 364.1369 | 0.76 | 201.0764, 183.0657, 165.0554, 179.0556, 119.0339 | Harpagide | Std. |

| 3 | 2.33 | C16H24O10 | 421.1359 | 376.1369 | 1.70 | 183.0663, 213.0769, 195.0657, 163.0395, 113.0239 | 6-O-Methyl catalpol | Std. |

| 4 | 4.11 | C9H8O4 | 179.0343 | 180.0422 | −4.09 | 134.9868, 90.9968 | cis-Caffeic acid | [13] |

| 5 | 4.17 | C9H8O4 | 179.0342 | 180.0422 | −4.23 | 134.9869, 90.9968 | trans-Caffeic acid | [13] |

| 6 | 6.08 | C17H26O11 | 451.1462 | 406.1475 | 1.03 | 301.6125, 183.0656, 165.0557, 119.0337 | 8-O-acetylharpagide | Std. |

| 7 | 6.71 | C9H8O3 | 163.0392 | 164.0473 | −4.76 | 119.0491 | p-Coumaric acid | [13,25] |

| 8 | 10.37 | C30H38O16 | 653.2102 | 654.2160 | −3.56 | 377.1252, 325.8607, 315.1097, 309.0978, 291.0882, 187.0396, 181.0497, 163.0394, 145.0286, 119.0491 | Saccatoside | Std. |

| 9 | 10.82 | C30H38O16 | 653.2102 | 654.2160 | −3.54 | 377.1250, 325.8607, 315.1096, 309.0977, 291.0883, 187.0394, 181.0498, 163.0394, 145.0286, 119.0492 | p-Coumaroyl rhamnopyranosylcatalopol isomer | |

| 10 | 11.00 | C30H38O16 | 653.2101 | 654.2160 | −4.36 | 377.1250, 325.8607, 315.1096, 309.0977, 291.0883, 187.0394, 181.0498, 163.0394, 145.0286, 119.0492 | Premnacorymboside B | Std. |

| 11 | 13.54 | C30H38O16 | 653.2100 | 654.2160 | −3.89 | 377.1250, 325.8607, 315.1096, 309.0977, 291.0883, 187.0394, 181.0498, 163.0394, 145.0286, 119.0492 | p-Coumaroyl rhamnopyranosylcatalopol isomer | |

| 12 | 14.69 | C29H36O15 | 623.1993 | 624.2054 | 1.92 | 461.1671, 161.0236, 113.0233 | Verbascoside | [24,25] |

| 13 | 19.92 | C30H38O15 | 683.2205 | 638.2211 | 1.46 | 361.1303, 215.0710, 163.0392, 147.0442, 113.0233 | 6-O-α-L-(2”-O-trans-Cinnamoyl) rhamnopyranosylcatalpol | Std. |

| 14 | 20.15 | C35H32O12 | 689.1869 | 644.1894 | −0.69 | 309.0985, 187.0394, 163.0392, 145.0285, 119.0491 | p-Coumaroyl glycoside | [13] |

| 15 | 20.43 | C24H30O12 | 509.1671 | 510.1737 | 1.25 | 201.0764, 183.0654, 163.0392, 145.0285, 119.0491 | p-Coumaroyl harpagide | [24] |

| 16 | 20.65 | C30H38O15 | 683.2205 | 638.2211 | 0.87 | 361.1297, 215.0709, 163.0391, 147.0441, 113.0239 | 6-O-α-L-(3”-O-trans-Cinnamoyl) rhamnopyranosylcatalpol | Std. |

| 17 | 24.55 | C24H30O11 | 539.1775 | 494.1788 | −0.88 | 183.0658, 165.0549, 147.0442, 103.0540 | cis-Harpagoside (8-O-(Z)-Cinnamoylharpagide) | Std. |

| 18 | 25.26 | C28H32O14 | 637.1788 | 592.1792 | 1.26 | 283.0616, 162.446 | Linarin (Acacetin-7-O-rutinoside) | Std. |

| 19 | 27.40 | C24H30O11 | 539.1778 | 494.1788 | −1.45 | 207.0663, 183.0656, 165.0580, 147.0443, 139.0391, 113.0233 | trans-Harpagoside (8-O-(E)-Cinnamoylharpagide) | Std. |

| 20 | 28.20 | C30H34O15 | 679.1894 | 634.1897 | −1.45 | 283.0616, 193.5697 | Linarin derivative | |

| 21 | 28.86 | C25H32O12 | 523.1829 | 524.1893 | 1.46 | 274.2028, 174.9554, 154.0627, 147.0442, 130.1828, 119.5446 | unknown | |

| 22 | 29.98 | C30H34O15 | 679.1895 | 634.1897 | −1.37 | 283.0616, 193.5697 | Linarin derivative | |

| 23 | 30.10 | C25H28O11 | 503.1780 | 504.1788 | 2.42 | 323.0932, 209.0969, 175.0397, 147.0443, 131.0492 | Cinnamoyl derivative | [13] |

| 24 | 30.27 | C25H30O11 | 505.1725 | 506.1788 | 1.94 | 299.1295, 195.0658, 147.0443, 133.0649, 113.0233 | Cinnamoyl derivative | [13] |

| 25 | 31.12 | C18H32O5 | 327.2183 | 328.2249 | 1.91 | 174.9924, 125.8304, 98.9845 | unknown | |

| 26 | 35.91 | - | 989.5344 | - | - | 811.4868, 649.4336, 471.3470, 161.0447, 191.0559, 143.0339, 127.9389 | unknown | |

| 27 | 37.38 | C16H12O5 | 283.0613 | 284.0684 | −1.69 | 179.2318, 112.2200, 71.4901 | Acacetin | |

| 28 | 39.45 | - | 957.5082 | - | - | 617.4067, 161.0445, 145.0497, 101.0231 | unknown |

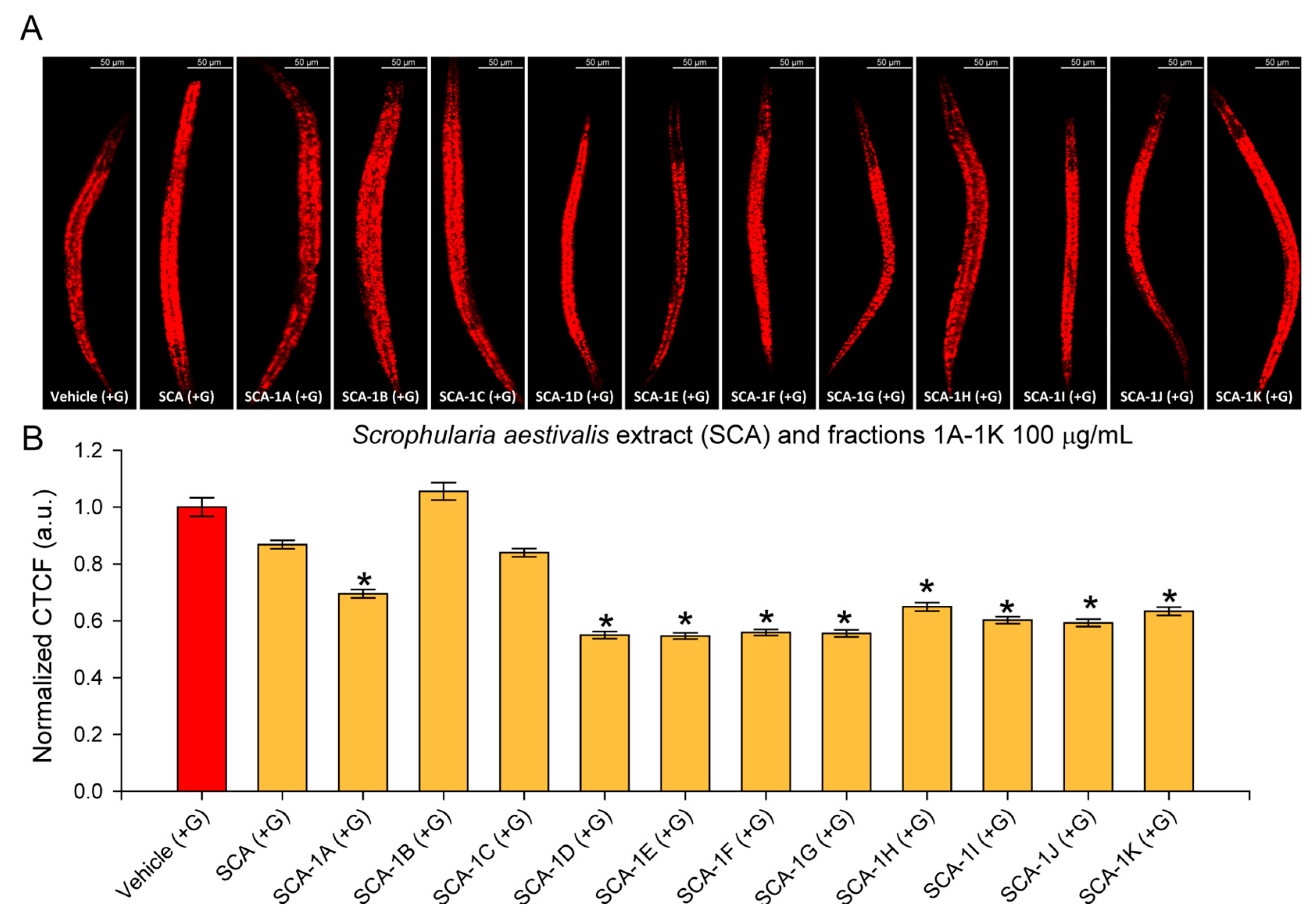

2.2. The SCA Fractions Modulate Lipid Accumulation in a Glucose-Induced Obesity Model

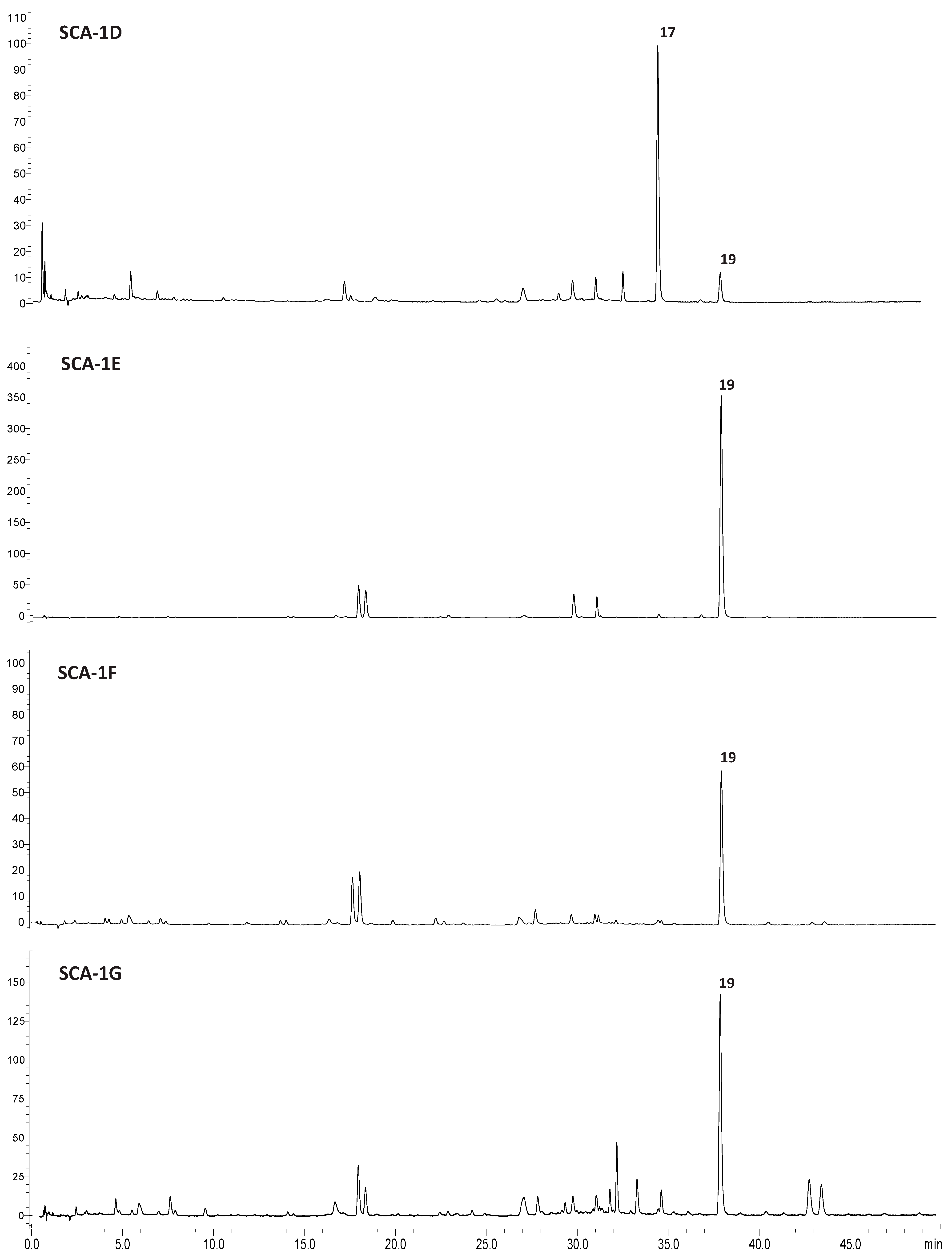

2.3. Qualitative Analysis by UPLC-HRMS/MS of SCA Active Fractions

2.4. Quantitative Analysis by HPLC-UV of SCA Extract and Active Fractions

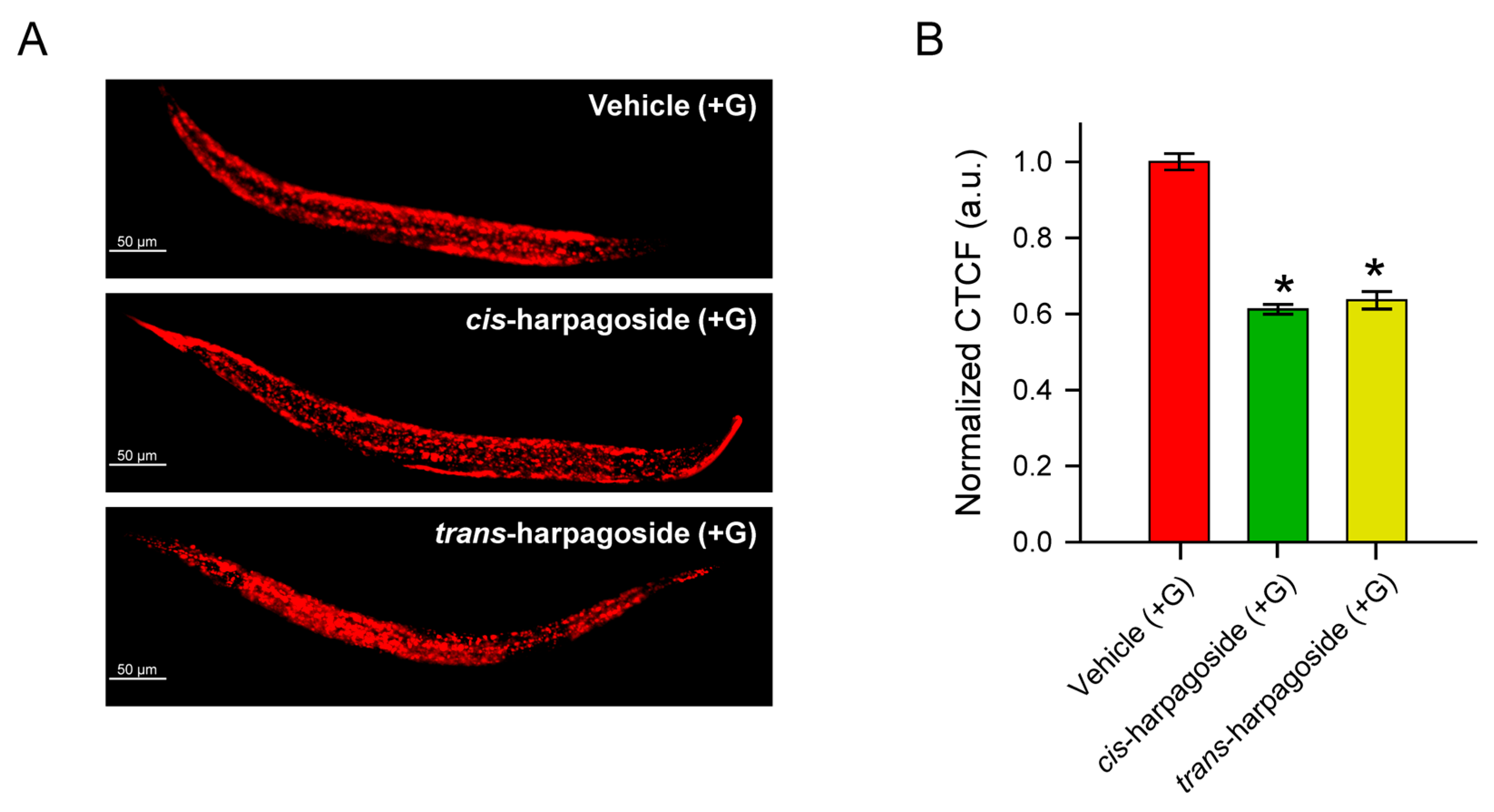

2.5. Anti-Obesogenic Effect of Isolated cis- and trans-Harpagoside in C. elegans

2.6. Harpagoside Isomers Alleviate Glucose-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction in C. elegans

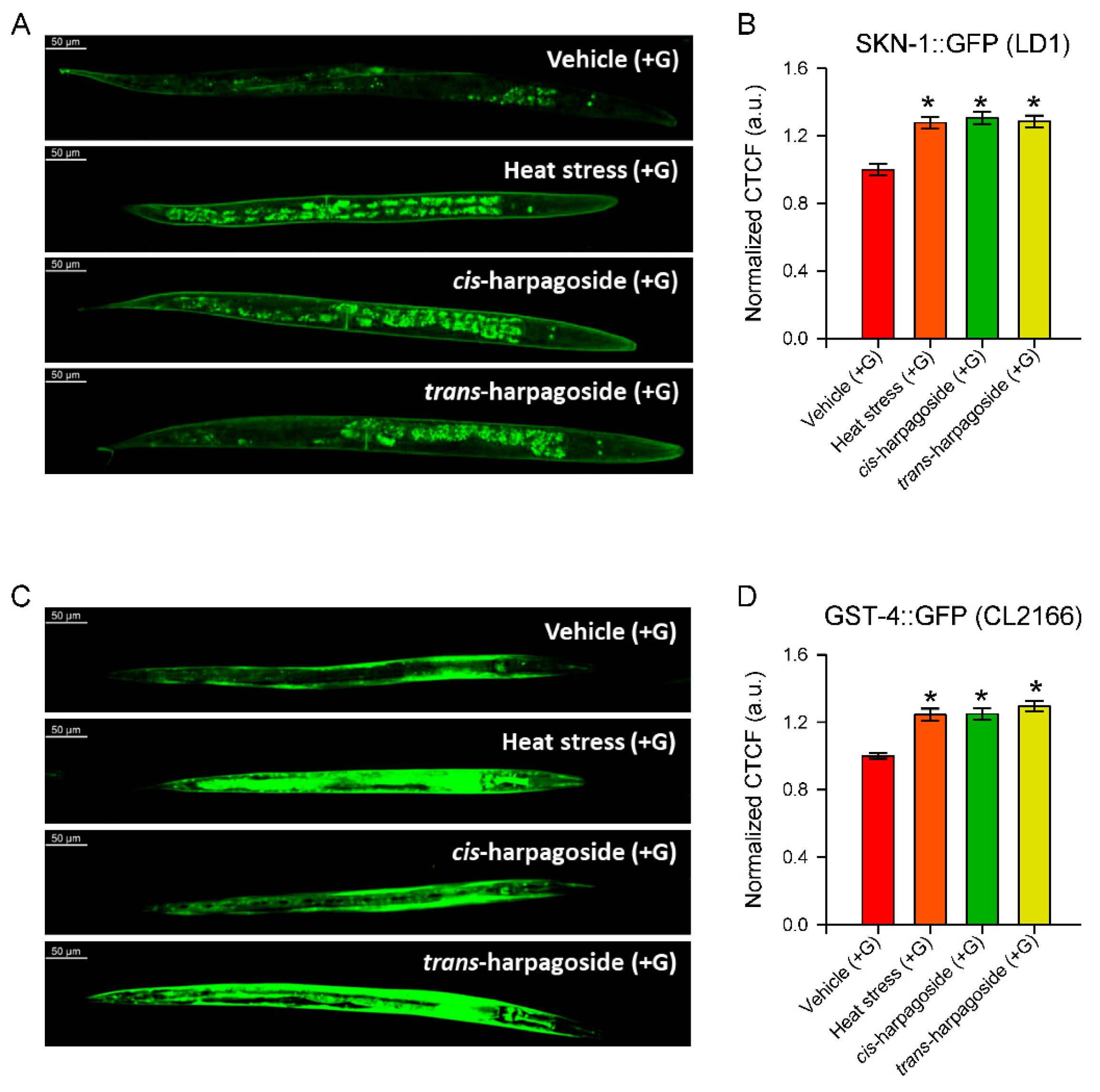

2.7. The Transcription Factor SKN-1 and Its Downstream Target gst-4 Are Upregulated upon cis- and trans-Harpagoside Treatment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Experimental Procedures

4.2. Caenorhabditis Elegans Maintenance and Treatment

4.3. Chemicals and Reagents

4.4. Plant Material

4.5. Extraction Procedure and Isolation

4.6. Qualitative Analysis by UPLC-HRMS/MS

4.7. Quantitative Analysis by HPLC-UV

4.8. LC Sample Preparation

4.9. Nile Red Triglyceride Staining

4.10. Mitochondrial Mass and Potential Assay

4.11. Detection of GFP-Fluorescence of SJ4143, CL2166, and LD1 Strains

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTCF | Correlated total cell fluorescence |

| gst-4 | Glutathione S-transferase 4 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| SCA | Scrophularia aestivalis |

| SKN-1 | Protein skinhead-1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| UPLC-HRMS/MS | ultra-high liquid chromatography with high-resolution mass spectrometry |

References

- Blüher, M. The past and future of obesity research. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.D.; Blüher, M.; Tschöp, M.H.; DiMarchi, R.D. Anti-obesity drug discovery: Advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 21, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savova, M.S.; Todorova, M.N.; Binev, B.K.; Georgiev, M.I.; Mihaylova, L.V. Curcumin enhances the anti-obesogenic activity of orlistat through SKN-1/NRF2-dependent regulation of nutrient metabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, J. Engineering yeast to produce plant-derived anti-obesity agent. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 1204–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, M.N.; Savova, M.S.; Mihaylova, L.V.; Georgiev, M.I. Punica granatum L. leaf extract enhances stress tolerance and promotes healthy longevity through HLH-30/TFEB, DAF16/FOXO, and SKN1/NRF2 crosstalk in Caenorhabditis elegans. Phytomedicine 2024, 134, 155971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheunert, A.; Heubl, G. Against all odds: Reconstructing the evolutionary history of Scrophularia (Scrophulariaceae) despite high levels of incongruence and reticulate evolution. Org. Divers. Evol. 2017, 17, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFO. World Flora Online. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15704590 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Pasdaran, A.; Hamedi, A. The genus Scrophularia: A source of iridoids and terpenoids with a diverse biological activity. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 2211–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, T.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Melzig, M.F. Pancreatic lipase and a-amylase inhibitory activities of plants used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Pharmazie 2016, 71, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaibeddra, Z.; Akkal, S.; Ouled-Haddar, H.; Silva, A.M.S.; Zellagui, A.; Sebti, M.; Cardoso, S.M. Scrophularia tenuipes Coss and Durieu: Phytochemical composition and biological activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, P.; Mehta, L.; Malhotra, A.; Kapoor, G.; Nagarajan, K.; Kumar, P.; Chawla, V.; Chawla, P.A. Exploring the multitarget potential of iridoids: Advances and applications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 23, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, A.A.; Ayoub, I.M.; Youssef, F.S.; Al-Sayed, E.; Efferth, T.; Singab, A.N.B. Phytochemistry, structural diversity, biological activities and pharmacokinetics of iridoids isolated from various genera of the family Scrophulariaceae Juss. Phytomed. Plus 2022, 2, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tan, Y.; Xia, Y.; Tang, H.; Li, J.; Tan, N. Targeted characterization and guided isolation of chemical components in Scrophulariae Radix based on LC-MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 235, 115569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, Z.; Calis, I.; Junior, P. Iridoid and phenylpropanoid glycosides from Pedicularis condensate. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 2401–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-M.; Jiang, S.-H.; Gao, W.-Y.; Zhu, D.-Y. Iridoid glycosides from Scrophularia ningpoensis. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.M.P.; Solis, R.V.; Baez, E.G.; Martinez, F.M. Effect on capillary permeability in rabbits of iridoids from Buddleia scordioides. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuria, K.M.; Chepkwony, H.; Govaerts, C.; Roets, E.; Busson, R.; De Witte, P.; Zupko, I.; Hoornaert, G.; Quirynen, L.; Maes, L.; et al. The antiplasmodial activity of isolates from Ajuga remota. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Yamasaki, K.; Takeda, Y.; Seki, T. Iridoid Diglycoside monoacyl esters from the leaves of Premna japonica. J. Nat. Prod. 1990, 53, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, N.T.B.; Ky, P.T.; Van Minh, C.; Cuong, N.X.; Thao, N.P.; Van Kiem, P. Study on the chemical constituents of Premna integrifolia L. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, E.; Rimpler, H. Iridoid glycosides and phenolic glycosides from Holmskioldia sanguinea. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potterat, O.; Saadou, M.; Hostettmann, K. Iridoid glucosides from Rogeria adenophylla. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhu, A.; Kuai, X.; Luo, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, K. Purification process and in vitro and in vivo bioactivity evaluation of pectolinarin and linarin from Cirsium japonicum. Molecules 2022, 27, 8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaghipisheh, J.; Taghrir, H.; Dehsheikh, A.B.; Zomorodian, K.; Irajie, C.; Sourestani, M.M.; Iraji, A. Linarin, a glycosylated flavonoid, with potential therapeutic attributes: A comprehensive review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, G.; Qin, M. Dynamic analysis of secondary metabolites in various parts of Scrophularia ningpoensis by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 186, 113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You-Hua, C.; Jin, Q.; Jing, H.; Bo-Yang, Y. Structural characterization and identification of major constituents in Radix Scrophulariae by HPLC coupled with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2014, 12, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, S.; Iranpanah, A.; Gravandi, M.M.; Moradi, S.Z.; Ranjbari, M.; Majnooni, M.B.; Echeverría, J.; Qi, Y.; Wang, M.; Liao, P.; et al. Natural products attenuate PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway: A promising strategy in regulating neurodegeneration. Phytomedicine 2021, 91, 153664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiev, M.I.; Ivanovska, N.; Alipieva, K.; Dimitrova, P.; Verpoorte, R. Harpagoside: From Kalahari Desert to pharmacy shelf. Phytochemistry 2013, 92, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, A.; Ansari, M.Y.; Haqqi, T.M. Harpagoside suppresses IL-6 expression in primary human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. J. Orthop. Res. 2017, 35, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Cheon, Y.H.; Ahn, S.J.; Kwak, S.C.; Chung, C.H.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, M.S. Harpagoside attenuates local bone erosion and systemic osteoporosis in collagen-induced arthritis in mice. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Harpagoside protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via P53-Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 813370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauzá-Thorbrügge, M.; Peris, E.; Zamani, S.; Micallef, P.; Paul, A.; Bartesaghi, S.; Benrick, A.; Wernstedt Asterholm, I. NRF2 is essential for adaptative browning of white adipocytes. Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumeni, S.; Papanagnou, E.D.; Manola, M.S.; Trougakos, I.P. Nrf2 activation induces mitophagy and reverses Parkin/Pink1 knock down-mediated neuronal and muscle degeneration phenotypes. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, J.A.; Caruso, M.; Brandes, M.S.; Gray, N.E. Loss of NRF2 leads to impaired mitochondrial function, decreased synaptic density and exacerbated age-related cognitive deficits. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 131, 110767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenova, S.G.; Todorova, M.N.; Savova, M.S.; Georgiev, M.I.; Mihaylova, L.V. Maackiain mimics caloric restriction through aak-2-mediated lipid reduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savova, M.S.; Mihaylova, L.V.; Tews, D.; Wabitsch, M.; Georgiev, M.I. Targeting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in obesity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 159, 114244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gong, X.; Gong, H.; Cheng, R.; Qiu, F.; Zhong, X.; Huang, Z. Iridoid glycosides from Radix Scrophulariae attenuates focal cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated neuronal apoptosis in rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, I.E.; Baghtchedjian, L.; Cordon, M.E.; Dumont, E. Phytochemistry, medicinal properties, bioactive compounds, and therapeutic potential of the genus Eremophila (Scrophulariaceae). Molecules 2022, 27, 7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renda, G.; Kadıoğlu, M.; Kılıç, M.; Korkmaz, B.; Kırmızıbekmez, H. Anti-inflammatory secondary metabolites from Scrophularia kotschyana. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2021, 40, S676–S683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.T.H.; Tang, H.K.; Nguyen, A.T.H.; Le, L.B. Survey on the herbal combinations in traditional Vietnamese medicine formulas for obesity treatment based on literature. Obes. Med. 2025, 51, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Miao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, W. Effect and mechanism of Qing Gan Zi Shen decoction on heart damage induced by obesity and hypertension. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 319, 117163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, J.J.; Zhang, X.X.; Yan, Y.; Yin, X.W.; Ping, G.; Jiang, W.M. Qing Gan Zi Shen Tang alleviates adipose tissue dysfunction with up-regulation of SIRT1 in spontaneously hypertensive rat. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 105, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, R.; Elincheva, V.; Gevrenova, R.; Zheleva-Dimitrova, D.; Momekov, G.; Simeonova, R. Targeting inflammation with natural products: A mechanistic review of iridoids from Bulgarian medicinal plants. Molecules 2025, 30, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Lee, D.; Park, S.; Jang, Y.; Ahn, J.; Ha, T.; Jung, C.H. Antiobesity effects of the combination of Patrinia scabiosifolia root and Hippophae rhamnoides leaf extracts. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Luan, X.; Zheng, M.; Tian, X.-H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.-D.; Ma, B.-L. Synergistic mechanisms of constituents in herbal extracts during intestinal absorption: Focus on natural occurring nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gxaba, N.; Manganyi, M.C. The fight against infection and pain: Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) a rich source of anti-inflammatory activity: 2011–2022. Molecules 2022, 27, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.-J.; Kim, W.K.; Oh, J.; Kim, M.-R.; Shin, J.-S.; Lee, J.; Ha, I.-H.; Lee, S.K. Correction to Antiosteoporotic activity of harpagoside by upregulation of the BMP2 and WNT signaling pathways in osteoblasts and suppression of differentiation in osteoclasts. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.K.; Park, K.S. Inhibitory effects of harpagoside on TNF-α-induced pro-inflammatory adipokine expression through PPAR-γ activation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Cytokine 2015, 76, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lou, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhong, X.; Huang, Z. Harpagide from Scrophularia protects rat cortical neurons from oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation-induced injury by decreasing endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 253, 112614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.K.; Cech, N.B. Synergy and antagonism in natural product extracts: When 1 + 1 does not equal 2. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fuentes, C.; Theeuwes, W.F.; McMullen, M.K.; McMullen, A.K.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Schellekens, H. Devil’s Claw to suppress appetite—Ghrelin receptor modulation potential of a Harpagophytum rocumbens root extract. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Xiong, Z. Protective effects of harpagoside on mitochondrial functions in rotenone-induced cell models of Parkinson’s disease. Biomed. Rep. 2025, 22, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin-Chabot, C.; Wang, L.; Celik, C.; Abdul Khalid, A.T.; Thalappilly, S.; Xu, S.; Koh, J.H.; Lim, V.W.X.; Low, A.D.; Thibault, G. The unfolded protein response reverses the effects of glucose on lifespan in chemically-sterilized C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Pang, S.; Tang, H. The impact of glucose on mitochondria and life span is determined by the integrity of proline catabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, K.; Ji, F.; Breen, P.; Sewell, A.; Han, M.; Sadreyev, R.; Ruvkun, G. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in C. elegans Activates Mitochondrial Relocalization and Nuclear Hormone Receptor-Dependent Detoxification Genes. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Jeon, W.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Ha, I.H. Harpagophytum procumbens inhibits iron overload-induced oxidative stress through activation of Nrf2 signaling in a rat model of lumbar spinal stenosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 3472443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalaki, I.; Markaki, M.; Gkikas, I.; Tavernarakis, N. Local coordination of mRNA storage and degradation near mitochondria modulates C. elegans ageing. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Iridoid Glycosides (mg/g d. Extr. ± RSD) | SCA | SCA-1D | SCA-1E | SCA-1F | SCA-1G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-Harpagoside (17) | 85.35 ± 0.42 | 58.25 ± 0.53 | - | - | - |

| trans-Harpagoside (19) | 45.17 ± 0.44 | 25.72 ± 0.28 | 501.06 ± 0.33 | 69.18 ± 0.48 | 121.45 ± 0.16 |

| total | 130.52 | 83.97 | 501.06 | 69.18 | 121.45 |

| Iridoid Glycosides Concentrations (μg/mL; μM) | SCA | SCA-1D | SCA-1E | SCA-1F | SCA-1G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-Harpagoside (17) | 8.54; 17.26 | 5.83; 11.78 | - | - | - |

| trans-Harpagoside (19) | 4.52; 9.13 | 2.57; 5.20 | 50.11; 101.33 | 6.92; 13.99 | 12.15; 24.56 |

| total | 13.06; 26.39 | 8.40; 16.98 | 50.11; 101.33 | 6.92; 13.99 | 12.15; 24.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Priboyska, K.; Todorova, M.N.; Gerasimova, V.I.; Savova, M.S.; Krustanova, S.; Petkova, Z.; Stoyanov, S.; Popova, M.P.; Georgiev, M.I.; Alipieva, K. Phytochemical Profiling and Anti-Obesogenic Potential of Scrophularia aestivalis Griseb. (Scrophulariaceae). Molecules 2025, 30, 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214202

Priboyska K, Todorova MN, Gerasimova VI, Savova MS, Krustanova S, Petkova Z, Stoyanov S, Popova MP, Georgiev MI, Alipieva K. Phytochemical Profiling and Anti-Obesogenic Potential of Scrophularia aestivalis Griseb. (Scrophulariaceae). Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214202

Chicago/Turabian StylePriboyska, Konstantina, Monika N. Todorova, Vanya I. Gerasimova, Martina S. Savova, Slaveya Krustanova, Zhanina Petkova, Stoyan Stoyanov, Milena P. Popova, Milen I. Georgiev, and Kalina Alipieva. 2025. "Phytochemical Profiling and Anti-Obesogenic Potential of Scrophularia aestivalis Griseb. (Scrophulariaceae)" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214202

APA StylePriboyska, K., Todorova, M. N., Gerasimova, V. I., Savova, M. S., Krustanova, S., Petkova, Z., Stoyanov, S., Popova, M. P., Georgiev, M. I., & Alipieva, K. (2025). Phytochemical Profiling and Anti-Obesogenic Potential of Scrophularia aestivalis Griseb. (Scrophulariaceae). Molecules, 30(21), 4202. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214202