Development and Validation of HPLC-DAD/FLD Methods for the Determination of Vitamins B1, B2, and B6 in Pharmaceutical Gummies and Gastrointestinal Fluids—In Vitro Digestion Studies in Different Nutritional Habits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chromatographic Method Development

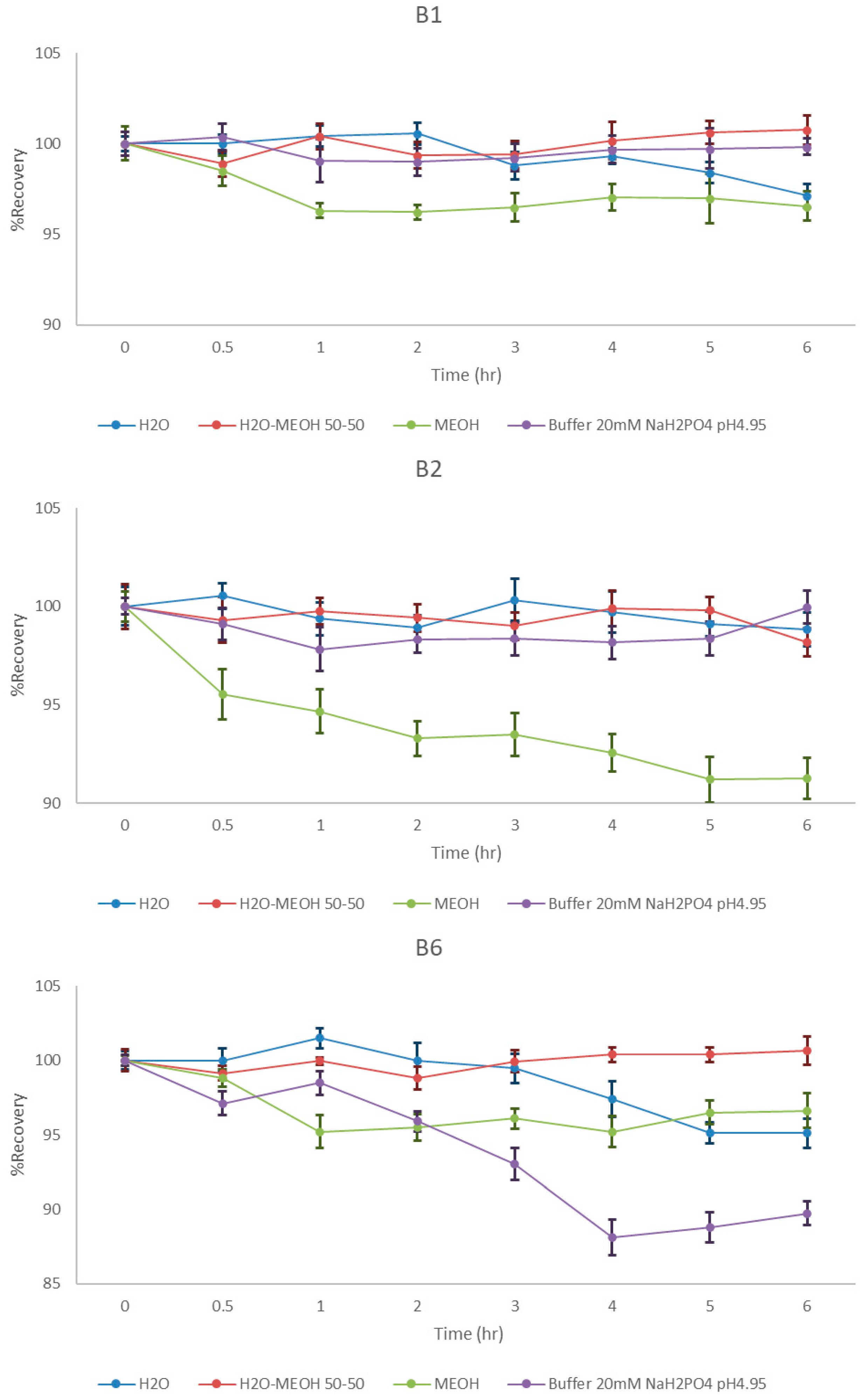

2.2. Stability Study of B1, B2, and B6 in Different Solvents

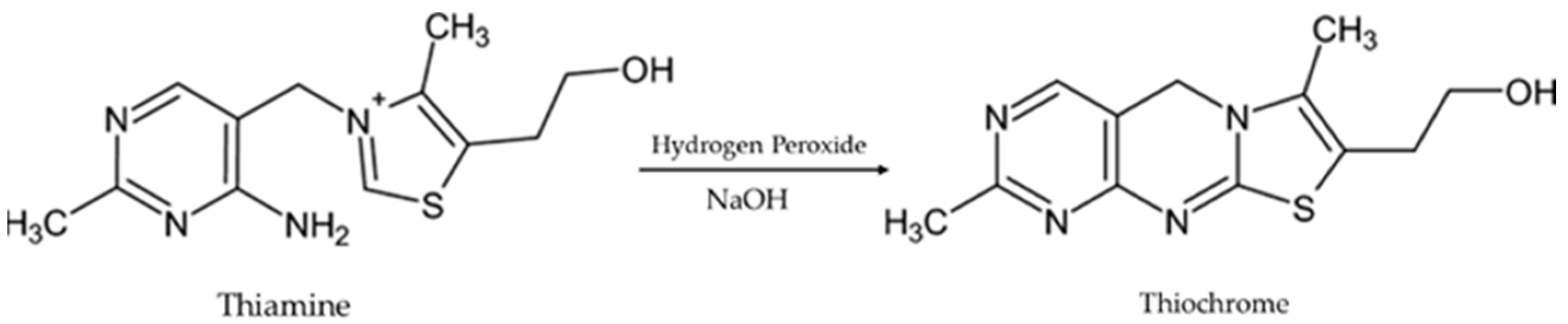

2.3. Derivatization Procedure

2.3.1. Temperature

2.3.2. Diluents

2.3.3. Effect of pH on the Oxidation Reaction

2.4. Method Validation

2.4.1. System Suitability

2.4.2. Selectivity

2.4.3. Linearity and LOD-LOQ

2.4.4. Precision-Repeatability

2.4.5. Accuracy

2.4.6. Robustness

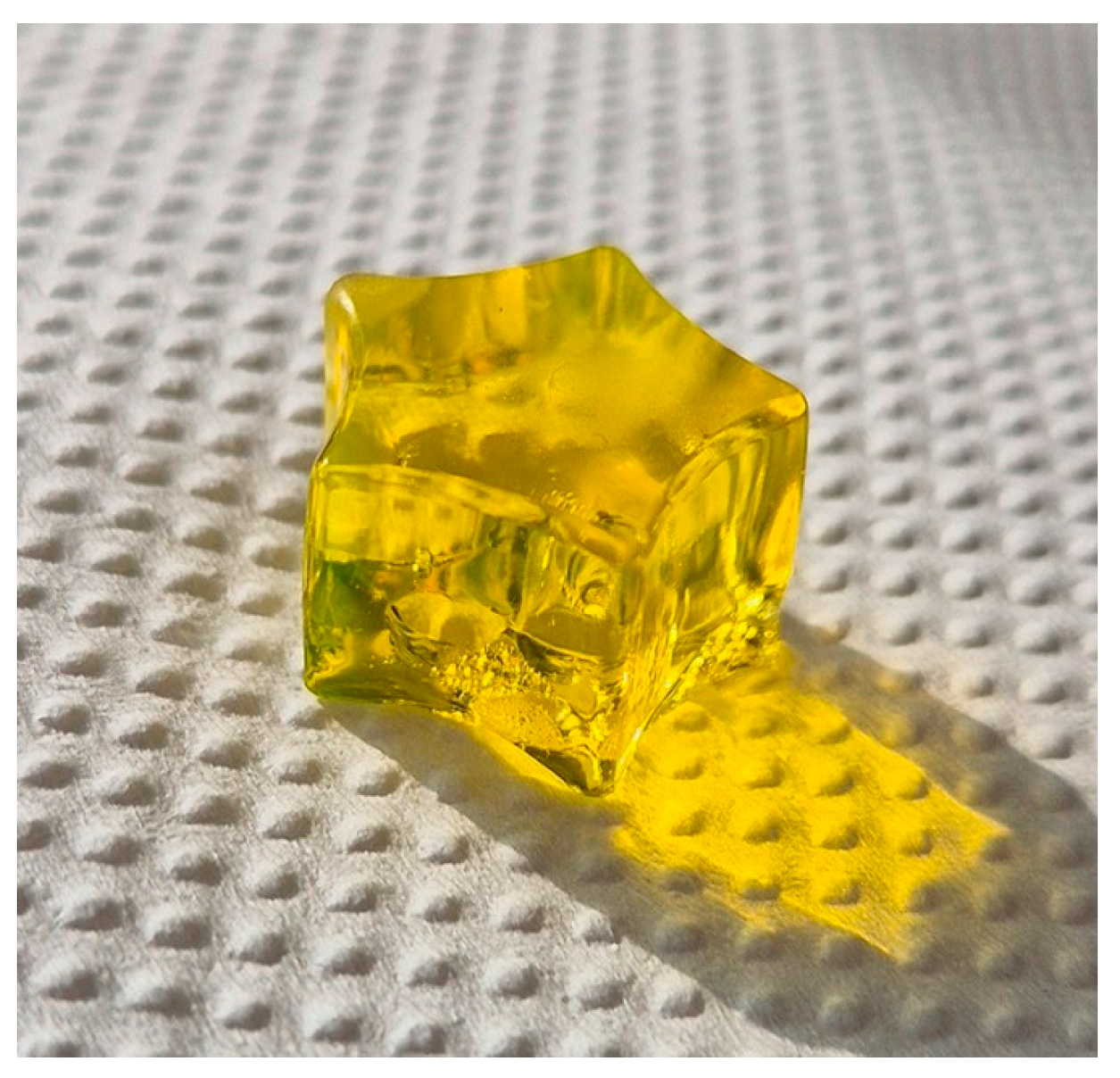

2.5. Formulation Studies

2.5.1. Sample Pretreatment

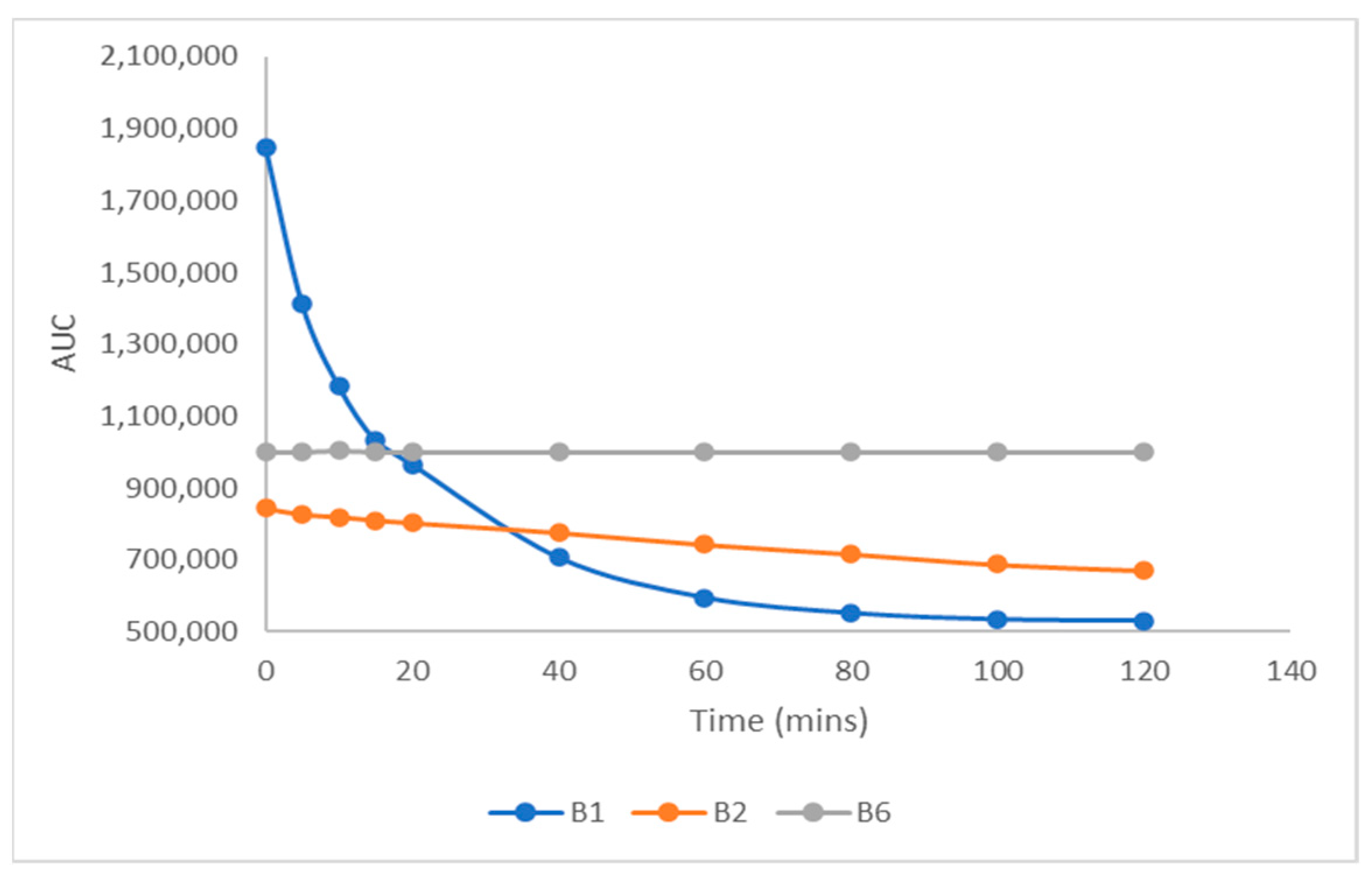

2.5.2. Formulation Stability Study

2.6. In Vitro Digestion Protocol

2.6.1. Samples Pretreatment

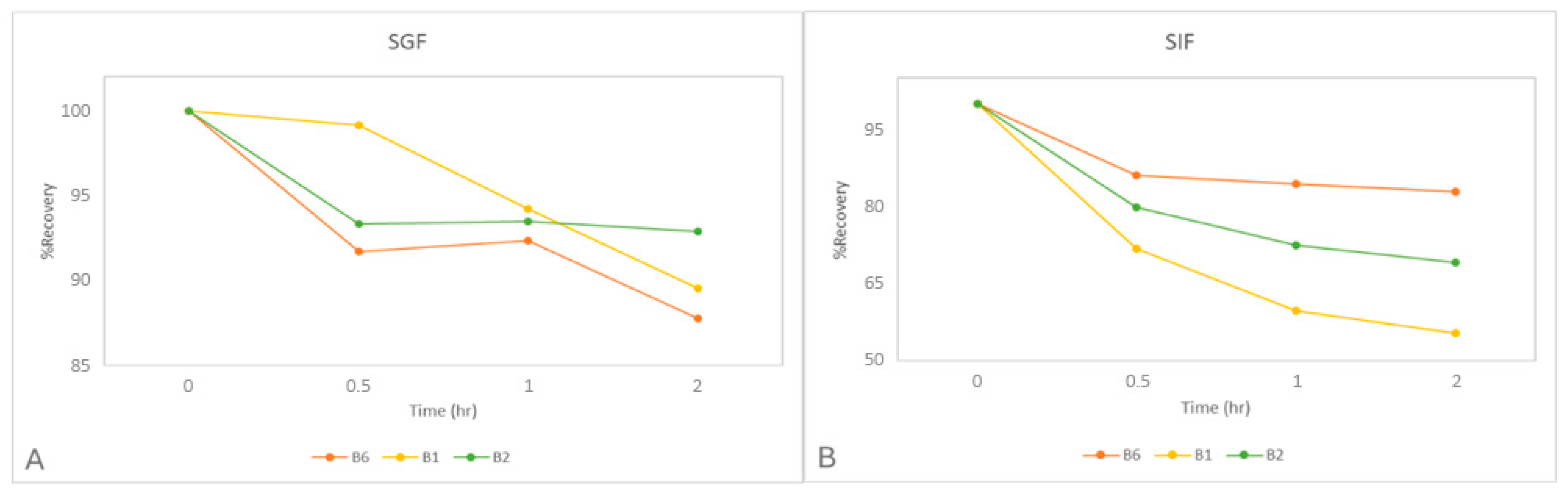

2.6.2. Stability Study of B1, B2, and B6 in Digestive Fluids

2.6.3. Digestion Protocol Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instruments and Equipment

3.2. Reagents and Solvents

3.3. Solutions

3.3.1. Stock Solutions

3.3.2. Derivatization Solutions

3.3.3. Stimulated Fluids

3.4. Gummies Preparation

3.5. Pretreatment of the Formulation Before Analysis

3.6. In Vitro Digestion Protocol

3.6.1. SPE Procedure

3.6.2. Sediment Reconstitution

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sivaprasad, M.; Shalini, T.; Reddy, P.Y.; Seshacharyulu, M.; Madhavi, G.; Kumar, B.N.; Reddy, G.B. Prevalence of vitamin deficiencies in an apparently healthy urban adult population: Assessed by subclinical status and dietary intakes. Nutrition 2019, 63–64, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollbracht, C.; Gündling, P.W.; Kraft, K.; Friesecke, I. Blood concentrations of vitamins B1, B6, B12, C and D and folate in palliative care patients: Results of a cross-sectional study. J. Int. Med Res. 2019, 47, 6192–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, O.; Almubark, R.; Almarshad, A.; Alqahtani, A.S. The Prevalence of Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies and High Levels of Non-Essential Heavy Metals in Saudi Arabian Adults. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churuangsuk, C.; Catchpole, A.; Talwar, D.; Welsh, P.; Sattar, N.; Lean, M.E.; Combet, E. Low thiamine status in adults following low-carbohydrate/ketogenic diets: A cross-sectional comparative study of micronutrient intake and status. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 2667–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, E.; Guzel, O.; Arslan, N. Analysis of hematological parameters in patients treated with ketogenic diet due to drug-resistant epilepsy. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.; Davis, B.; Joshi, S.; Jardine, M.; Paul, J.; Neola, M.; Barnard, N.D. Ketogenic Diets and Chronic Disease: Weighing the Benefits Against the Risks. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 702802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levran, N.; Levek, N.; Sher, B.; Gruber, N.; Afek, A.; Monsonego-Ornan, E.; Pinhas-Hamiel, O. The Impact of a Low-Carbohydrate Diet on Micronutrient Intake and Status in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, S.; Tarasenko, M.; Napoli, E.; Giulivi, C. Neurological, Psychiatric, and Biochemical Aspects of Thiamine Deficiency in Children and Adults. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambon, M.; Wins, P.; Bettendorff, L. Neuroprotective Effects of Thiamine and Precursors with Higher Bioavailability: Focus on Benfotiamine and Dibenzoylthiamine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, M.; Mollace, R.; Ritorto, G.; Ussia, S.; Altomare, C.; Tavernese, A.; Preianò, M.; Palma, E.; Muscoli, C.; Mollace, V.; et al. A Systematic Review of Thiamine Supplementation in Improving Diabetes and Its Related Cardiovascular Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dricot, C.E.M.K.; Erreygers, I.; Cauwenberghs, E.; De Paz, J.; Spacova, I.; Verhoeven, V.; Ahannach, S.; Lebeer, S. Riboflavin for women’s health and emerging microbiome strategies. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva-Araújo, E.R.; Toscano, A.E.; Silva, P.B.P.; Junior, J.P.d.S.; Gouveia, H.J.C.B.; da Silva, M.M.; Souza, V.d.S.; Silva, S.R.d.F.; Manhães-De-Castro, R. Effects of deficiency or supplementation of riboflavin on energy metabolism: A systematic review with preclinical studies. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e332–e342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, M. Regulation and function of pyridoxal phosphate in CNS. Neurochem. Int. 1981, 3, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaris, G.; Mitsiou, V.-P.M.; Chachlioutaki, K.; Almpani, S.; Markopoulou, C.K. Development and Validation of an HPLC-FLD Method for the Determination of Pyridoxine and Melatonin in Chocolate Formulations—Digestion Simulation Study. Chemistry 2025, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafeshani, M.; Feizi, A.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Keshteli, A.H.; Afshar, H.; Roohafza, H.; Adibi, P. Higher vitamin B6 intake is associated with lower depression and anxiety risk in women but not in men: A large cross-sectional study. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2020, 90, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Raje, V.; Maczko, P.; Patel, K. Application of 3D printing technology for the development of dose adjustable geriatric and pediatric formulation of celecoxib. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 655, 123941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebanso, T.; Shimohata, T.; Mawatari, K.; Takahashi, A. Functional Roles of B-Vitamins in the Gut and Gut Microbiome. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 2000426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsson, B.; Albery, T.; Eriksson, A.; Gustafsson, I.; Sjöberg, M. Food effects on tablet disintegration. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 22, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, S.A. Effect of beverages on the disintegration time of drugs in the tablet dosage form. Mediterr. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 4, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Almukainzi, M.; Alobaid, R.; Aldosary, M.; Aldalbahi, Y.; Bashiri, M. Investigation of the effects of different beverages on the disintegration time of over-the-counter medications in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabian, E.; Majchrzak, D.; Dieminger, B.; Meyer, E.; Elmadfa, I. Influence of Probiotic and Conventional Yoghurt on the Status of Vitamins B1, B2 and B6 in Young Healthy Women. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 52, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.W.; Burgin, C.W.; Cerda, J.J. Characterization of Food Binding of Vitamin B-6 in Orange Juice. J. Nutr. 1977, 107, 2128–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albawarshi, Y.; Amr, A.; Al-Ismail, K.; Shahein, M.; Majdalawi, M.; Saleh, M.; Khamaiseh, A.; El-Eswed, B. Simultaneous Determination of B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, and B12 Vitamins in Premix and Fortified Flour Using HPLC/DAD: Effect of Detection Wavelength. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R.P.; Rose, W.P.; Tabor, R.; Pattison, T.S. Simultaneous Determination of Vitamins B1, B2, B6, and Niacinamide in Multivitamin Pharmaceutical Preparations by Paired-ion Reversed-phase High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography. J. Pharm. Sci. 1981, 70, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohora, F.-T.; Sarwar, S.; Khatun, O.; Begum, P.; Khatun, M.; Ahsan, M.; Islam, S.N. Estimation of B-vitamins (B1, B2, B3 and B6) by HPLC in vegetables including ethnic selected varieties of Bangladesh. Pharm. Pharmacol. Int. J. 2020, 8, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presoto, A.E.F.; Rios, M.D.G.; Almeida-Muradian, L.B. Simultaneous high performance liquid chromatographic analysis of vitamins B1, B2 and B6 in royal jelly. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2004, 15, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Shao, L.; Xie, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Pei, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhai, Y.; et al. A novel LC-MS/MS assay for vitamin B1, B2 and B6 determination in dried blood spots and its application in children. J. Chromatogr. B 2019, 1112, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, A.; Caretti, F.; D’AScenzo, G.; Marchese, S.; Perret, D.; Di Corcia, D.; Rocca, L.M. Simultaneous determination of water-soluble vitamins in selected food matrices by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 22, 2029–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, K.R.; Carlson, L.T.; Devol, A.H.; Armbrust, E.V.; Moffett, J.W.; Stahl, D.A.; Ingalls, A.E. Determination of four forms of vitamin B12 and other B vitamins in seawater by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 28, 2398–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cellar, N.A.; McClure, S.C.; Salvati, L.M.; Reddy, T.M. A new sample preparation and separation combination for precise, accurate, rapid, and simultaneous determination of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, and B9 in infant formula and related nutritionals by LC-MS/MS. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 934, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antakli, S.; Sarkees, N.; Sarraf, T. Determination of water-soluble vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, B12 and c on C18 column with particle size 3 µM in some manufactured food products by hplc with UV-DAD/FLD detection. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 7, 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zafra-Gómez, A.; Garballo, A.; Morales, J.C.; García-Ayuso, L.E. Simultaneous Determination of Eight Water-Soluble Vitamins in Supplemented Foods by Liquid Chromatography. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4531–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliszczyńska-Świgło, A.; Rybicka, I. Simultaneous Determination of Caffeine and Water-Soluble Vitamins in Energy Drinks by HPLC with Photodiode Array and Fluorescence Detection. Food Anal. Methods 2015, 8, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simultaneous Analysis of Vitamins B1, B2, B3 and B6 in Protein Powders and Supplements. Available online: https://www.pickeringlabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Analysis-of-mixed-B-vitamins-MA239.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—an international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Wilson, M.; Klinger, C.M.; Franklin, M.; Oler, E.; Wilson, A.; Pon, A.; Cox, J.; Chin, N.E.; A Strawbridge, S.; et al. DrugBank 6.0: The DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1265–D1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; E Bolton, E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Connor, R.; Feldgarden, M.; Fine, A.M.; Funk, K.; Hoffman, J.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D20–D29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.A.; Randall, E.A.; Wolfe, P.C.; Kraft, C.E.; Angert, E.R. Pre-analytical challenges from adsorptive losses associated with thiamine analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ahmary, K.M. A simple spectrophotometric method for determination of thiamine (vitamin B1) in pharmaceuticals. Eur. J. Chem. 2014, 5, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.A.; Tu-Maung, N.; Cheng, K.; Wang, B.; Baeumner, A.J.; Kraft, C.E. Thiamine Assays-Advances, Challenges, and Caveats. ChemistryOpen 2017, 6, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L.-Y.; Dai, Z.; Di, B.; Xu, L.-L. Advances in Cryochemistry: Mechanisms, Reactions and Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaris, G.; Tsami, M.; Lotca, G.-R.; Almpani, S.; Markopoulou, C.K. A Pre-Column Derivatization Method for the HPLC-FLD Determination of Dimethyl and Diethyl Amine in Pharmaceuticals. Molecules 2024, 29, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, E.N. Biological systems. In Lipid Oxidation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 391–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH. ICH Q2 (R2) Guideline on Validation of Analytical Procedures. Available online: www.ema.europa.eu/contact (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Alampanos, V.; Kabir, A.; Furton, K.G.; Roje, Ž.; Vrček, I.V.; Samanidou, V. Fabric phase sorptive extraction combined with high-performance-liquid chromatography-photodiode array analysis for the determination of seven parabens in human breast tissues: Application to cancerous and non-cancerous samples. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1630, 461530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, A.; Halkjær, J.; van Gils, C.H.; Buijsse, B.; Verhagen, H.; Jenab, M.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Ericson, U.; Ocké, M.C.; Peeters, P.H.M.; et al. Dietary intake of the water-soluble vitamins B1, B2, B6, B12 and C in 10 countries in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, S122–S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shasho, R.; Shasho, M. Diagnostic Approach Common Cases of Vitamins Toxicity in Children. Sch. J. Appl. Med Sci. 2022, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhale, M.; Singh, R.; Sharma, R.; Arora, S.; Bothra, R. Analytical approaches for estimation of B vitamins in food: A review on the shift from single to multi-vitamin analysis. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025, 19, 5242–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqueous Solution of Riboflavin. Available online: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/c7/f4/fd/cc0a396e32d522/US2407624.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Karaiskou, S.G.; Kouskoura, M.G.; Markopoulou, C.K. Modern pediatric formulations of the soft candies in the form of a jelly: Determination of metoclopramide content and dissolution. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2020, 25, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Lemos, E.; Almeida, A.R.; Vouga, B.; Morais, C.; Correia, I.; Pereira, P.; Guiné, R.P.F. Development and characterization of healthy gummy jellies containing natural fruits. Open Agric. 2021, 6, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Gawai, N.M.; Shivhare, B.; Vijapur, L.S.; Tiwari, G. Development and Evaluation of Herbal-Enriched Nutraceutical Gummies for Pediatric Health. Pharmacogn. Res. 2024, 16, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszewski, B.; Szultka, M. Past, Present, and Future of Solid Phase Extraction: A Review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2012, 42, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimichalakis, P.F.; Samanidou, V.F.; Verpoorte, R.; Papadoyannis, I.N. Development of a validated HPLC method for the determination of B-complex vitamins in pharmaceuticals and biological fluids after solid phase extraction. J. Sep. Sci. 2004, 27, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamkouri, N.; Khodadoust, S.; Ghalavandi, F. Solid-Phase Extraction Coupled with HPLC-DAD for Determination of B Vitamin Concentrations in Halophytes. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, bmv080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelker, A.L.; Taylor, L.S.; Mauer, L.J. Effect of pH and concentration on the chemical stability and reaction kinetics of thiamine mononitrate and thiamine chloride hydrochloride in solution. BMC Chem. 2021, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, W.; Anwar, Z.; Qadeer, K.; Perveen, S.; Ahmad, I. Methods of analysis of riboflavin (vitamin B2): A review. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 2, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, C.Y. Stability of three forms of vitamin B6 to laboratory light conditions. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1979, 62, 1170–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigelmo-Miguel, N.; Martı, O. Characterization of dietary fiber from orange juice extraction. Food Res. Int. 1998, 31, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, G.K.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Fenelon, M.; Huppertz, T. A Review on the Effect of Calcium Sequestering Salts on Casein Micelles: From Model Milk Protein Systems to Processed Cheese. Molecules 2023, 28, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples (Reference) | Method | Stationary-Mobile Phase | Sample Preparation/Extraction Method | LOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dried blood spots (DBSs) [27] | LC-MS/MS | ACE® C8 Column, 4.6 × 100 mm, 5 μm (Wrotham, UK) Gradient: (A) H2O/formic acid 0.1% (v/v) and (B) acetonitrile | hydration (trichloroacetic acid), sonication, centrifugation | B1: 0.5 ng/mL B2: 0.2 ng/mL B6: 0.5 ng/mL |

| Foods [28] | LC/ESI-MS/MS | Avantor® Alltima C18, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 mm (Chadds Ford, PA, USA) Gradient: (A) acetonitrile with 5 mmol/L formic acid and (B) water with 5 mmol/L formic acid | SPE-0.5 g, C18, elution with 14 mL of EtOH/H2O 1:1 | B1: 2.0–12.9 ng/g B2: 4.0–6.2 ng/g B6: 0.9–11.0 ng/g |

| Seawater [29] | UPLC/ESI-MS | UPLC HSS Cyano Column Waters Acquity®, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm (Milford, MA, USA) Gradient: (A) 20 mM ammonium formate with 0.1% formic acid in water (B) and acetonitrile | C18 SPE (Waters, 35 mL, 10 g resin), samples: at pH 5.5–6.5 with HCl, adjusted to pH 6.5, elution with 40 mL MeOH | B1: 0.059 pM B2: 0.124 pM B6: 0.149 pM |

| Infant formula and related nutritionals [30] | LC-MS/ MS-ESI | Waters Acquity® BEH C18 Column, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 mm (Milford, MA, USA) Gradient: (A) 20 mM ammonium formate and (B) methanol | 1% glacial acid in methanol, centrifugation, 50 mM ammonium formate, filtration | - |

| Food products (cacao and milk powder, infant food, orange juice powder) [31] | HPLC UV-DAD/FLD | C18 BDS, Thermo Fisher® 100 × 4.6 mm, 3 µm (Waltham, MA, USA) Gradient: (A): 5.84 mM of hexane-1-sulfonic acid sodium: acetonitrile (95:5) with 0.1% triethylamine at pH 2.5 and (B): similar to (A) in 50:50. | Step 1: centrifugation, sonication, evaporation of MeOH, addition 0.1 mL NaOH 0.17 M, Step 2: 0.1 mL H3PO4 5 M, sonication, centrifugation Step 1 + Step 2 filtration | B1: 16.5 ng/mL B2: 1.9 ng/mL B6: 1.3 ng/mL |

| Royal Jelly [26] | HPLC UV-DAD/FLD | Vydac® C18 reversed phase Column, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm (Hesperia, CA, USA) Isocratic: hexanesulfonic acid, ammonium hydroxide, acetonitrile and water (0.09:0.05:9.02:90.84) with pH adjusted to 3.6 | 1 mL 8% trichloroacetic acid, centrifugation, filtration | B1: 66.90 ng/mL B2: 6.47 ng/mL B6: 7.80 ng/mL |

| Milk Products [32] | HPLC UV-Vis/FLD | C18 Waters Spherisorb® ODS-2 Column, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 3 µm (Milford, MA, USA) Gradient: (A) phosphate buffer, pH 2.95 (6.8 g KH2PO4, 1.1 g of 1-octanesulfonic acid, Na salt, and 5 mL of triethylamine in 1 L of H2O) and (B) MeOH | sonication, centrifugation, filtration | B1: 0.02 μg/mL B2: 0.005 μg/mL B6: 0.04 μg/mL |

| Energy drinks [33] | HPLC PDA/FLD | Nova-Pak C18 Column Waters Spherisorb®, 150 mm × 3.9 mm, 5 μm (Milford, MA, USA) fitted with μBondapak C18 cartridge guard column Gradient: (A) methanol and (B) 0.05M NaH2PO4 containing 0.005 M hexanesulfonic acid, pH 3.0 | ultrasonic degassing | B1: 25 ng/mL B2: 8 ng/mL B6: 19 ng/mL |

| Protein Powders [34] | HPLC-FLD | Thermo® Hypersil, Aquasil C18 Column, 4.6 × 150 mm (Waltham, MA, USA) Post-Column Derivatization System: Onyx PCX, Pinnacle PCX Gradient: (A) 4.77 g of Potassium Phosphate Monobasic in 1 L of DI water (pH to 5.9 with KOH) and (B) acetonitrile Post-Column Conditions: 10 g of Sodium Hydroxide in 500 mL of water and add 2 g of Sodium Sulfite | extraction buffer (0.1 N NaOH: pH 2 with H3PO4), heat at 100 °C, cool, filtration | B1: 0.03–10 μg/mL B2: 0.03–10 μg/mL B6: 0.125–10 μg/mL |

| Multi-Vitamins Supplements Tablets [34] | blend the tablets, dissolve with water acidified to pH 2.6 with 0.1 N HCl, magnetic stirring, filtration |

| (a) | ||||||

| Analytes | Tr * | Tf * | K′* | Rs * | N * | HETP * ×103 USP |

| B1 | 6.2 | 2.7 | 2.647 | 3.35 | 2090.0 | 119.616 |

| B2 | 10.0 | 1.3 | 4.889 | 5.97 | 8036.6 | 31.108 |

| B6 | 4.4 | 2.0 | 1.605 | - | 4073.3 | 61.367 |

| (b) | ||||||

| Analytes | Tr * | Tf * | K′ * | Rs * | N * | HETP * ×103 USP |

| B1 | 14.4 | 2.6 | 7.525 | 7.28 | 12155.0 | 20.567 |

| B2 | 10.0 | 1.2 | 4.920 | 15.87 | 9433.0 | 26.502 |

| B6 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 1.487 | - | 3721.1 | 67.184 |

| APIs | Concentration | Equation | %y Intercept | (R2) | LOD | LOQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/mL | HPLC-UV * | |||||

| B1 | 1.6–40 | y = (63,009 ± 553.4)x − 28,095 ± 10,134.4 | 1.13 | 0.999 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| B2 | 0.8–20 | y = (201,686 ± 1214.0)x − 10,894 ± 11,116.3 | 0.27 | 0.999 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| B6 | 0.8–20 | y = (130,165 ± 1097.3)x + 1292 ± 10,047.3 | 0.05 | 0.999 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| ng/mL | HPLC-FLD * | |||||

| B1 | 60–1600 | y = (19,058 ± 305.1)x + 254,796 ± 229,991 | 0.73 | 0.999 | 7.9 | 24.1 |

| B2 | 4–160 | y = (198,712 ± 2208.6)x − 243,031 ± 166,541 | 0.77 | 1 | 0.9 | 2.8 |

| B6 | 4–160 | y = (67,295 ± 965.8)x + 195,017 ± 72,827 | 1.61 | 0.999 | 1.2 | 3.6 |

| HPLC-UV * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APIs | Repeatability | Intermediate Precision | |||||

| Concentration | RSD% | Concentration | 1st Day | 2nd Day | 3rd Day | RSD% | |

| 1.6 (n = 3) | 0.22 | 1.6 (n = 3) | 0.22 | 1.67 | 1.77 | 1.41 | |

| B1 | 8 (n = 3) | 0.36 | 8 (n = 3) | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.12 | 0.74 |

| 40 (n = 3) | 0.09 | 40 (n = 3) | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.54 | |

| 0.8 (n = 3) | 0.42 | 0.8 (n = 3) | 0.42 | 1.02 | 0.7 | 0.75 | |

| B2 | 4 (n = 3) | 0.14 | 4 (n = 3) | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.52 |

| 20 (n = 3) | 0.3 | 20 (n = 3) | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.32 | |

| 0.8 (n = 3) | 0.48 | 0.8 (n = 3) | 0.48 | 0.65 | 0.34 | 0.7 | |

| B6 | 4 (n = 3) | 0.50 | 4 (n = 3) | 0.50 | 1.09 | 0.36 | 0.81 |

| 20 (n = 3) | 0.07 | 20 (n = 3) | 0.07 | 0.53 | 0.08 | 0.34 | |

| HPLC-FLD * | |||||||

| B1 | 60 (n = 3) | 1.02 | 60 (n = 3) | 1.02 | 1.76 | 3.05 | 3.23 |

| 400 (n = 3) | 2.01 | 400 (n = 3) | 2.01 | 2.93 | 0.48 | 2.81 | |

| 1600 (n = 3) | 1.1 | 1600 (n = 3) | 1.1 | 1.67 | 1.61 | 1.39 | |

| B2 | 4 (n = 3) | 0.87 | 4 (n = 3) | 0.87 | 1.41 | 1.82 | 1.11 |

| 40 (n = 3) | 1.3 | 40 (n = 3) | 1.3 | 0.84 | 1.24 | 1.77 | |

| 160 (n = 3) | 0.46 | 160 (n = 3) | 0.46 | 1.48 | 0.98 | 1.81 | |

| 4 (n = 3) | 1.11 | 4 (n = 3) | 1.11 | 0.57 | 1.76 | 1.69 | |

| B6 | 40 (n = 3) | 1.96 | 40 (n = 3) | 1.96 | 1.38 | 1.12 | 1.79 |

| 160 (n = 3) | 0.6 | 160 (n = 3) | 0.6 | 1.71 | 0.39 | 1.21 | |

| Parameters | %RSD (UV/FLD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B2 | B6 | ||||

| AUC | Tf | AUC | Tf | AUC | Tf | |

| Flow rate (±0.1 mL/min) | 7.59/4.91 | 6.11/9.14 | 11.76/6.88 | 6.56/13.81 | 10.22/10.11 | 4.7/9.51 |

| Temperature (±2 °C) | 2.53/0.33 | 1.97/0.42 | 0.26/1.2 | 0.35/0.79 | 0.78/1.22 | 0.86/0.85 |

| Mobile phase (±1%) A:B | 2.16/1.91 | 0.72/0.79 | 0.31/0.22 | 0.58/0.79 | 2.61/2.33 | 3.88/3.91 |

| λmax (±1 nm) | 0.58/0.34 | 0.55/0.29 | 0.46/0.51 | 0.1/0.38 | 0.46/0.77 | 0.04/0.81 |

| Vitamins | Water | Orange Juice | Milk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %Found | ||||||

| Intestinal | Sediment | Intestinal | Sediment | Intestinal | Sediment | |

| B1 | 79 | 21 | 91 | 9 | 85 | 15 |

| B2 | 73 | 17 | 68 | 22 | 63 | 27 |

| B6 | 80 | 10 | 79 | 11 | 77 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamaris, G.; Pantoudi, N.; Markopoulou, C.K. Development and Validation of HPLC-DAD/FLD Methods for the Determination of Vitamins B1, B2, and B6 in Pharmaceutical Gummies and Gastrointestinal Fluids—In Vitro Digestion Studies in Different Nutritional Habits. Molecules 2025, 30, 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30193902

Kamaris G, Pantoudi N, Markopoulou CK. Development and Validation of HPLC-DAD/FLD Methods for the Determination of Vitamins B1, B2, and B6 in Pharmaceutical Gummies and Gastrointestinal Fluids—In Vitro Digestion Studies in Different Nutritional Habits. Molecules. 2025; 30(19):3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30193902

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamaris, Georgios, Nikoletta Pantoudi, and Catherine K. Markopoulou. 2025. "Development and Validation of HPLC-DAD/FLD Methods for the Determination of Vitamins B1, B2, and B6 in Pharmaceutical Gummies and Gastrointestinal Fluids—In Vitro Digestion Studies in Different Nutritional Habits" Molecules 30, no. 19: 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30193902

APA StyleKamaris, G., Pantoudi, N., & Markopoulou, C. K. (2025). Development and Validation of HPLC-DAD/FLD Methods for the Determination of Vitamins B1, B2, and B6 in Pharmaceutical Gummies and Gastrointestinal Fluids—In Vitro Digestion Studies in Different Nutritional Habits. Molecules, 30(19), 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30193902