Abstract

This review focuses on the synthesis of spacer-armed phosphooligosaccharides structurally related to the capsular phosphoglycans of pathogenic bacteria, including the Haemophilus influenzae serotypes a, b, c, and f, Neisseria meningitidis serogroups a and x, the Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 6a, 6b, 6c, 6f, 19a, and 19f, and the Campylobacter jejuni serotype HS:53, strain RM1221, in which the phosphodiester linkage is a structural component of a phosphoglycan backbone. Also, in this review, we summarize the current knowledge on the preparation and immunogenicity of neoglycoconjugates based on synthetic phosphooligosaccharides. The discussed data helps evaluate the prospects for the development of conjugate vaccines on the basis of synthetic phosphooligosaccharide antigens.

1. Introduction

Among many smart tools for the colonization of human organs, pathogenic bacteria use a multilayer cell envelope [1,2], which is largely composed of glycans and their conjugates. The outermost thick layer found in the majority of Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria is called a glycan capsule, the composition and structure of which depend on the particular bacterial species [3]. Most capsular glycans are long-chain linear negatively charged CPSs or phosphoglycans. In the course of infection, this part of the bacterial outer shell first comes into contact with the components of innate and adaptive immunity. The anionic glycans of pathogenic bacteria shield them from the action of the components of the complement system, phagocytes and cationic antimicrobial peptides, which are secreted by immune and epithelial cells and destabilize the membrane of pathogenic bacteria [4,5]. Thus, it was established [6] that the phosphoglycan capsule of Hib prevents phagocyte attachment and the subsequent uptake of these bacteria. Moreover, Hib can survive and multiply after having been engulfed by a phagocyte in the acidic medium of phagolysosomes [7]. On the one hand, these biopolymers act as both protective shields and adhesive agents, enabling the bacterial evasion of host immunity [8], and on the other hand, they represent a target for the host immune system.

It is known that a key step in the adaptive immune response is the production of antigen-specific antibodies, and the presence of IgG indicates the development of immunological memory to surface biopolymers [9]. Immunological memory enables the body to quickly recognize the antigen on the surface of the pathogen during the second and subsequent contact and more effectively activate the body’s defenses. This phenomenon encouraged the development of a whole range of antibacterial prophylactic vaccines. To date, the most effective type of vaccines for the prevention of bacterial infections are conjugate vaccines [10,11,12,13,14,15,16], in which a capsular glycan of the targeted pathogen is covalently linked to a protein carrier. The use of glycoconjugates helps circumvent the problem of the low immunogenicity of CPS and directs immunity along the T-dependent pathway [17,18,19,20].

The majority of commercial conjugate vaccines are currently manufactured on the basis of CPS produced in bacterial cell cultures. This approach has significant disadvantages, which are the laborious and operationally challenging steps of manufacturing, sophisticated quality control, and the high cost of producing pathogenic microbiological material. At present, an advanced approach to glycan conjugate vaccines is being developed, which employs synthetic OS antigens as an alternative to bacterial CPS [21,22,23,24,25,26].

In the first step of conjugate OS vaccine development, it is important to specify the particular bacterial glycoantigen to be mimicked. The probability factor speaks in favor of regular glycans, which have a repeating unit. These include the CPS of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharide O-antigens of Gram-negative bacteria, and the cell-wall teichoic acids and lipoteichoic acids of Gram-positive bacteria. Today, commercial glycoconjugate vaccines incorporate bacterial glycan antigens exclusively.

In the second step, the optimum length of the OS, which is sufficient for the induction of protective immunity, has to be specified. On the one hand, the use of shorter OSs can significantly reduce production costs, and on the other hand, the OS chain has to be long enough to mimic the polymer and minimize the possible influence of the terminal monosaccharide residue. Identification of the minimum length of the OS antigen is performed in laboratory animals, which are immunized with the conjugates of synthetic oligosaccharides of different lengths, and the interaction of induced antibodies with bacterial antigens or directly with bacteria is investigated. It is commonly accepted [27] that the minimum length of an effective glycoantigen is 3–4 repeating units. A reliable algorithm that can predict the optimum length of OS antigens has not yet been developed. Today, the identification of protective glycotopes for conjugate vaccine candidates can be defined by the screening of glycan arrays, which encompass a series of synthetic OSs related to capsular glycans [28,29] in combination with conformational studies [29,30]. Alternatively, the development of the anti-Hib vaccine Quimi-Hib® (Centro de Ingeniería Genética y Biotecnología (CIGB), Republic of Cuba), which is a unique commercial synthetic OS-based conjugate vaccine, circumvented the problem of the choice of the optimum antigen length by the production of a protein-conjugated homologous phosphooligosaccharide obtained by oligomerization, with 7–8 repeating units as the average length of antigens [31]. The choice of the optimum structure of an OS antigen for a glycovaccine is complicated by the possibility of structural changes in a synthetic antigen after the injection of the vaccine into the recipient’s body. Partial lysis or migration of acetyl groups can occur in lymphs (pH 7.4–9.0) or endolysosomes of follicular B-lymphocytes [32,33,34], which are known to have an acidic environment.

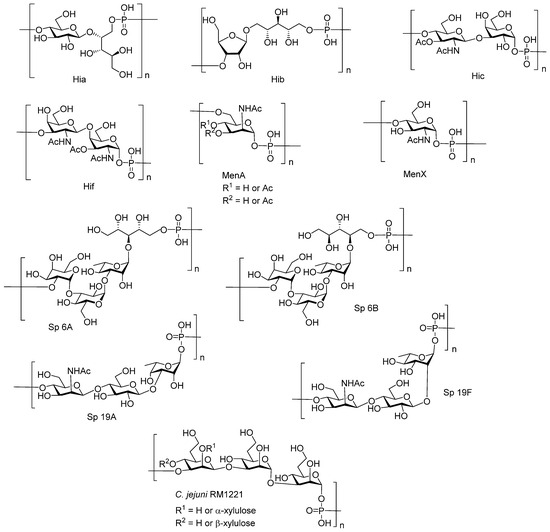

In a number of human pathogens, a phosphodiester bond is involved in the formation of the main polymer chain. Phosphoglycans of this type were found, for example, in the cell wall of the human pathogens Hia, Hib, Hic, and Hif, the S. pneumonia serotypes 6A, 6B, 11A, 17F, 19A, and 19F, the N. meningitidis serogroups A and X, the Campylobacter jejuni serotypes HS53 (strain RM1221) and HS1 (strain ATCC 43429), and Escherichia coli K100 and K2 (Figure 1) [35,36,37,38]. Today, eleven bacterial pathogens of this type (Hib, Men A, and the S. pneumonia serotypes 6A, 6B, 10A, 11A, 15B, 18C, 19A, 19F, and 23F) are targeted by preventive vaccination, with commercial conjugate vaccines based on the corresponding capsular phosphooligosaccharides [21].

Figure 1.

Examples of bacterial capsular phosphoglycans.

In this review, we focus on the synthesis of spacer-armed mono-, di-, and oligomeric antigens structurally related to bacterial capsular phosphoglycans (Figure 1), in which the repeating units are connected via a phosphodiester bond, and consider the preparation and immunogenicity of neoglycoconjugates on the basis of these antigens.

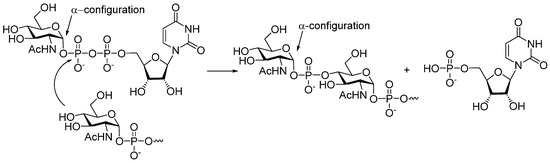

Phosphoglycans are the common glycocalyx components of pathogenic Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [35,36,39], yeast [39], and protozoan parasites [39,40]. In a living cell, phosphodiester-linked carbohydrates are arranged via the transfer of a hexose 1-phosphate to a glycan acceptor. In the presence of enzymes, which belong to the Stealth enzyme family, a hydroxyl group of a glycan acceptor attacks the phosphoester group in the nucleotide donor, and finally, a phosphodiester interglycosidic bridge unit is formed. It was established [41] (Figure 2) that in MenX bacteria, the hydroxyl group of N-acetyl glucosamine acceptor attacks the P-atom of uridine-5′-diphosphate-N-acetyl glucosamine to form an α-glycosyl phosphodiester, and the uridine monophosphate moiety serves as a leaving group.

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis of MenX phosphoglycan involves nucleotide glycosyl donor uridine-5′-diphosphate-N-acetyl glucosamine and is catalyzed by hexose phosphotransferase [41].

A similar method of the establishment of a phosphodiester intersaccharide bridge is used in laboratory practice for the preparation of phosphooligosaccharides related to bacterial phosphoglycans. For the efficient and stereoselective formation of a phosphodiester linkage, a phosphodiester synthon is first introduced into one of the saccharide blocks, and the resulting product is reacted with a free hydroxyl group of another saccharide block.

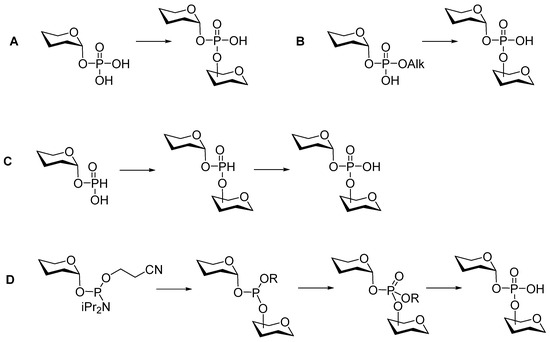

As a rule, phosphodiesters, along with their diverse precursors (mono- and diphosphates, H-phosphonates, and phosphamidites; Figure 3), decompose under the conditions of a glycosylation reaction. Therefore, the retrosynthetic analysis of phosphoglycans suggests the formation of phosphodiester bridges within the latest steps of the synthetic route after the glycosidic linkages are already established. Usually, the preparation of phosphooligosaccharides related to natural biopolymers is a multi-step synthesis, which can be performed following a linear, convergent, or oligomerization pathway via the formation of an O-P-O tether between selectively protected and activated saccharide blocks.

Figure 3.

Three main types of synthetic approaches used in the preparation of glycosyl phosphodiesters.

The conventional synthetic blocks for the preparation of glycosylphosphodiesters are monophosphates (Figure 3A), diphosphates (Figure 3B), H-phosphonates (Figure 3C), and phosphoramidites (Figure 3D). Previously developed methods of condensation involved phosphorus (V) chemistry (Figure 3A,B) and were promoted by N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and 1-(2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl)-3-nitro-1H-1,2,4-triazole. In the late 1980s, methods A and B gave way to fast, efficient, and convenient techniques that employed H-phosphonates (Figure 3C) and phosphoramidites (Figure 3D).

The H-phosphonate condensation general procedure [42,43] was first proposed in the 1950s for oligonucleotide synthesis by Todd et al. [44], and it was further developed [45,46] and adapted for solid-phase synthesis [47] and customized to the needs of phosphoglycan chemistry [39,48]. The phosphoramidite method was first proposed by van Boom [49] and was later successfully applied in the solid-phase preparation of long-chain oligophosphodiesters [50] and the P-modified analogs of glycosylphosphate oligomers [51]. In addition to current methods, novel approaches are being actively developed, which are aimed at the preparation of glycosylphosphates with a predetermined anomeric configuration and the synthesis of the stabilized mimetics of phosphoglycans [52,53,54,55,56,57,58].

One of the key features of bacterial phosphoglycans and synthetic phosphooligosaccharides is their susceptibility to degradation via hydrolytic cleavage, transesterification, and rearrangement. Thus, PRP (Figure 1) was found to degrade spontaneously [59,60] in aqueous media. This molecule is destabilized by a hydroxyl group at C-2 (D-ribose), which is located in close proximity to the phosphodiester moiety and promotes the depolymerization and formation of cyclophosphate and phosphate monoester terminal groups [61]. In vaccine production, the inherent tendency of PRP to autolyze results in the loss of manufactured phosphoglycan and conjugate preparations [60]. Additionally, the low stability of PRP imposes significant limitations on the use of liquid Hib vaccines, especially in view of the acceleration of the degradation process in the presence of an alum adjuvant [62]. Stability studies conducted by Cintra et al. [60] showed that the rate of PRP depolymerization accelerates substantially with an increase in pH in the range 5.41–7.55 and with a rise in temperature in the interval of 28–40 °C. As a result, it may be assumed that in a host organism, PRP intensely degrades into fragments, which neutralize anti-PRP protective antibodies, thus hampering the immune response. In a similar way, partial PRP destruction after immunization with a conjugate Hib vaccine may result in the loss of Hib epitopes and reduce the level of protective anti-Hib antibodies. Two more factors that affect the stability of PRP are the presence of Na+ [60] and Ca2+ [59] cations. Similar to PRP, the capsular phosphoglycan of Hif (Figure 1) was shown to decompose under mild conditions [59].

MenA capsular phosphoglycan is especially susceptible to hydrolysis. It is assumed that the hydrolytic destruction of α-glycosylphosphodiester linkage occurs by two pathways. One of these includes the formation of an oxocarbenium ion, and within another pathway, the phosphodiester bond is cleaved with the assistance of the axial NAc group located at C-2 of the ManNAc, and a thermodynamically stable oxazoline is formed [63].

2. Synthesis of Pseudo-Oligosaccharides Structurally Related to PRP

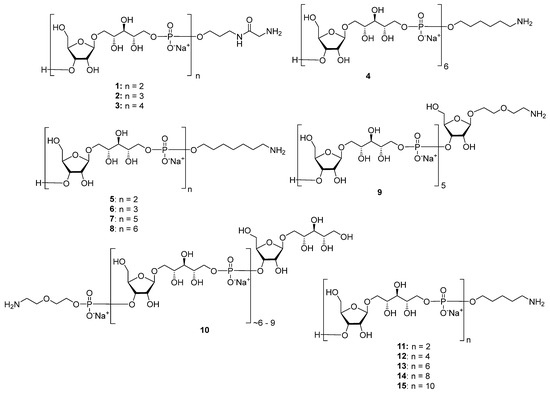

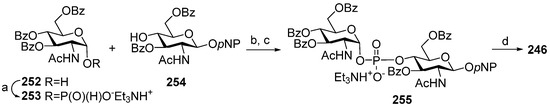

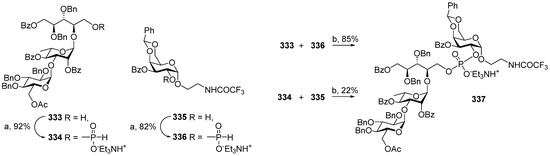

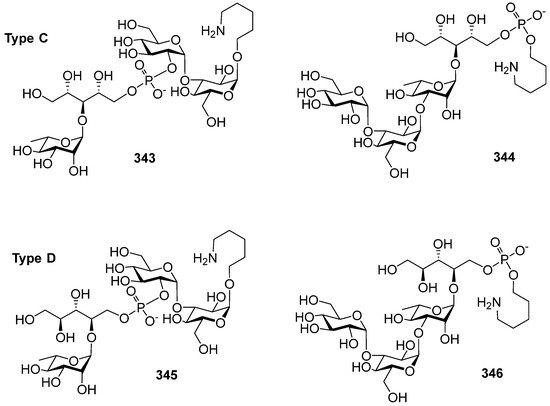

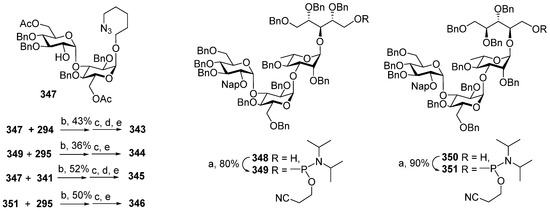

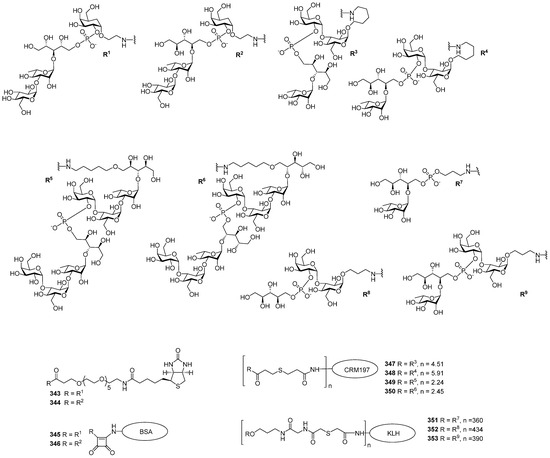

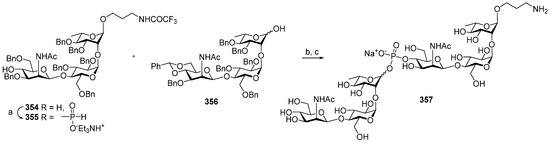

Highly effective infant immunization with conjugate Hib vaccines, which are composed of a partially depolymerized Hib capsular phosphoglycan and a protein carrier (see review [15]), inspired researchers to develop conjugate vaccines using oligomer synthetic PRP fragments (Figure 4). Several series of PRP-related oligomers were synthesized, which were equipped with different types and locations of amino-spacers for convenient attachment to a protein carrier (compounds 1–15, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Synthetic pseudo-oligosaccharides structurally related to PRP.

In pseudo-oligosaccharide 13 with a N-glycyl-aminopropyl spacer, which comprises two, three, or four residues of PRP repeating units [64], as well as in hexamer 4 [65] and oligomers 5–8 [66], the ω-aminospacer is linked to the D-ribose fragment via a phosphodiester bond. In pentamer 9 [67], the spacer is attached immediately to C-1 of a D-ribose residue as an aglycone. In the oligomeric mixture 10 [68] and in most of the representative oligomer series, which comprises the individual compounds 11–15 [69], the spacer is connected to a D-ribose via a phosphodiester bridge. In this review, basic synthetic blocks and strategies used in the preparation of compounds 1–15 are briefly considered, with a focus on the arrangement of a phosphodiester linkage and the introduction of a ω-aminospacer. A more detailed consideration of the syntheses of pseudo-oligosaccharides 1–15 was presented in our earlier review [15].

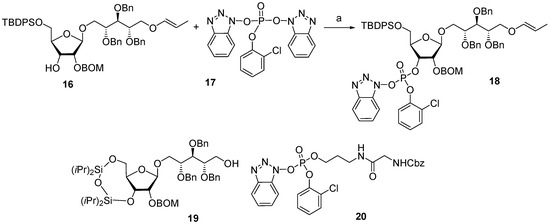

Between 1988 and 1992, van Boom and his research group at Leiden University synthesized spacer-armed PRP-related fragments for the first time. Dimer 1 [64,70], trimer 2 [64,70], and tetramer 3 [71] (Figure 4) were prepared by a sequential elongation of the oligomer chain from the non-reducing end, and the final equipment with an aminospacer. In brief, the phosphorylation of a free 3-OH group in the selectively protected riboside 16 with bis(benzotriazol-1-yl) (2-chlorophenyl) phosphate 17 produced the key activated phosphotriester building block 18 (Scheme 1). The condensation of compound 18 with the selectively protected disaccharide 19 in the presence of N-methylimidazole in Py, followed by the removal of the 1-O-propenyl group, was carried out in a sequential manner, one, two, or three times, followed by the final capping with phosphotriester 20. Total deprotection afforded the series of conjugation-ready compounds 1–3.

Scheme 1.

Key building blocks for the synthesis of spacer-armed PRP-related oligomers (1–3). Reagents and conditions: (a) Py/dioxane, r.t., 30 min [64,70,71].

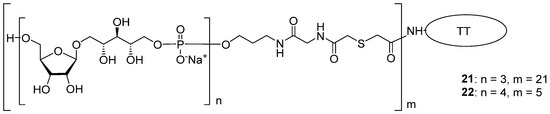

The spacer-armed trimer 2 and tetramer 3 were conjugated to TT (Figure 5) to create the corresponding neoglycoconjugates 21 and 22. The antigenic properties of oligomers 2 and 3 as components of neoglycoconjugates 21 and 22 were examined [71] in competitive inhibition ELISA experiments. A conjugate of bacterial PRP and tyramine was used as a coating antigen, and normal human serum and bacterial PRP were used as positive controls.

Figure 5.

Conjugates 21 and 22 obtained from PRP oligomers 2 and 3 with TT [71].

Total inhibition was observed when bacterial PRP and conjugate 22 (tetramer + TT, Figure 5) at a concentration of 25 μg/mL were used as inhibitors, and conjugate 21 with the trimeric PRP–antigen was less effective. Compared to conjugates, the inhibitory capacity of the unconjugated oligomers 2 and 3 was much lower, and at a concentration of 25 μg/mL, it did not reach 40%.

The immunogenicity of glycoconjugates 21 and 22 was studied [71] in mice at a dose of 1 µg of phosphoglycan per mouse. IgG antibodies in immune sera were analyzed in ELISA using a bacterial PRP–tyramine conjugate as a coating antigen and normal human serum as a positive control. Conjugate 21 with a trimeric antigen was found to be low immunogenic in a mouse model. In IgG ELISA, the mean optical density value for the sera of immunized mice was less than two times that of the corresponding value obtained for the sera of mice that received PBS.

For the immune sera from mice vaccinated with conjugate 22, which comprised tetrameric residues, the mean optical density value was three times that of the negative control, thus unambiguously evidencing the immunogenicity of conjugate 22. Immunization experiments were conducted using preparations formulated with AlPO4 or without an adjuvant. It was shown that the presence of AlPO4 had no effect on the result of immunization [71].

To date, there is no animal model that reliably predicts the immunogenicity of glycoconjugate preparations in humans, and the choice of experimental animals for the examination of the immune activity of Hib preparations is usually at the discretion of the researcher. In the blood sera of immunized mice and guinea pigs, the concentration of antibodies directed against Hib antigens does not reach 1 mg/mL, and these animals are not recommended for laboratory studies of conjugate vaccines [66].

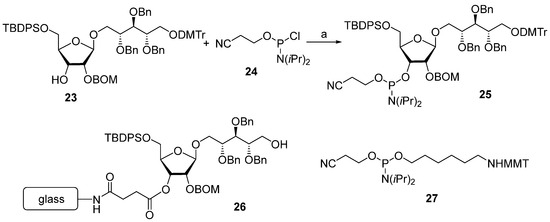

As shown in Scheme 1, the key reaction in the assembly of the synthetic Hib phosphooligosaccharides 1–3 is the arrangement of the O-P-O linkage, which can be applied iteratively. As no new chiral centers or other types of isomerism are created, this reaction sequence can be fulfilled using a solid-phase approach. This approach significantly decreases the number of laborious steps of the chromatographic separation of the product. In 1989, van Boom synthesized the spacer-armed hexamer 4 using controlled-pore glass as a solid support [65]. First, the selectively protected pseudo-disaccharide 23 was phosphitylated with chlorophosphoramidite 24 (Scheme 2), and the resulting phosphoramidite 25 was used for a stepwise extension of the oligomer chain starting from ribosylribitol 26, which was immobilized on a glass support. After each step of chain elongation, the phosphorus atom was oxidized with iodine in an acetonitrile/water/collidine mixture to obtain the corresponding phosphotriester, and the terminal DMTr protective group was removed to provide a free hydroxyl group for the next phosphitylation step. After the sequential attachment of five repeating units and spacer 27 and the removal of the protective groups, the target spacer-armed hexamer 4 was obtained.

Scheme 2.

Key building blocks for the synthesis of hexamer 4. Reagents and conditions: (a) diisopropylethylamide/dichloromethane, 85% yield [65].

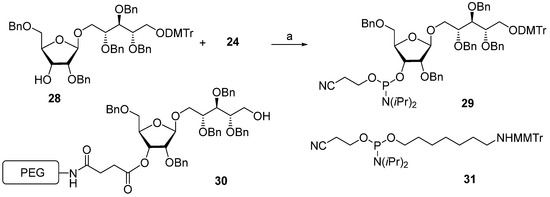

In 1992, Kandil et al. [66] synthesized the series of spacer-armed Hib oligomers 5–8 on a PEG support using a strategy similar to the synthesis of hexamer 4 (Scheme 3). In this synthesis, the tert-butyldiphenylsilyl and benzyloxymethyl protective groups in the starting pseudo-disaccharide 28 were replaced with easily removable benzyl groups. Thus, the sequential condensation of phosphoramidite 29 with PEG-immobilized pseudo-disaccharide 30 and detritylation was repeated five times. Next, the pre-spacer 31 was attached, and finally, total deprotection resulted in the formation of hexamer 6. The latter was conjugated to synthetic peptides structurally related to the Hib outer membrane protein, and one of these preparations showed immunogenicity comparable to that shown by the commercial Hib vaccine [72].

Scheme 3.

Key building blocks used in the synthesis of the spacer-armed oligomers 5–8. Reagents and conditions: (a) 1H-tetrazole/acetonitrile [66].

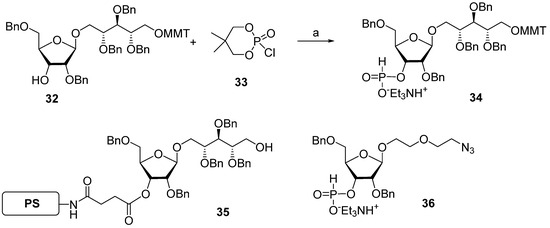

The same year, a group of Swedish researchers under the leadership of Norberg published [67] the synthesis of the Hib pentamer 9 on a polystyrene support (Scheme 4). In this work, the H-phosphonate method was used for the establishment of a phosphodiester bond, which subsequently became the most popular in the preparation of oligophosphoglycans related to the glycocalyx components of bacteria and parasites [39,56]. The selectively protected disaccharide 32 was reacted with 5,5-dimethyl-2-chloro-1,3,2-dioxaphosphorinane 2-oxide (compound 33) in Py and the presence of phosphonic acid to obtain H-phosphonate 34 with an 84% yield.

Scheme 4.

Key building blocks for the synthesis of pentamer 9 [67]. Reagents and conditions: (a) H3PO3, Py, yield of 84%.

The activation of H-phosphonates for subsequent attachment to alcohols can be achieved in the presence of the acyl chlorides of sterically hindered acids, e.g., PivCl or 1-adamantanecarbonyl chloride. In this reaction, the formation of by-products depends significantly on the order of the addition of reagents. For example, the activation of H-phosphonate by PivCl in Py in the absence of alcohol led to the formation of unwanted bis-acylated phosphites, and the use of a large excess of PivCl in solid-phase synthesis resulted in the pivaloylation of the support [67]. The search for the optimum conditions for the attachment of H-phosphonate 34 to be selectively protected and immobilized on the solid support monomer 35 resulted in the discovery of the most efficient proportion—5 eq. of PivCl and 5 eq. of H-phosphonate 34—that provided the adduct with a 95% yield. The authors noted [67] that the yield decreased with each chain extension step and dropped to 86% in the fourth cycle. The optimum sequence of reagent addition was found as follows: in the first step, H-phosphonate was activated by the addition of PivCl in Py, and then, the mixture was added to the immobilized alcohol. As a result, the yield of the pentamer increased to 96%. In the final step, the chain was capped with 2-(2-azidoethoxy) ethyl riboside 36, H-phosphonate was oxidized with iodine in 2% aqueous Py, and the protective groups were removed to obtain oligomer 9.

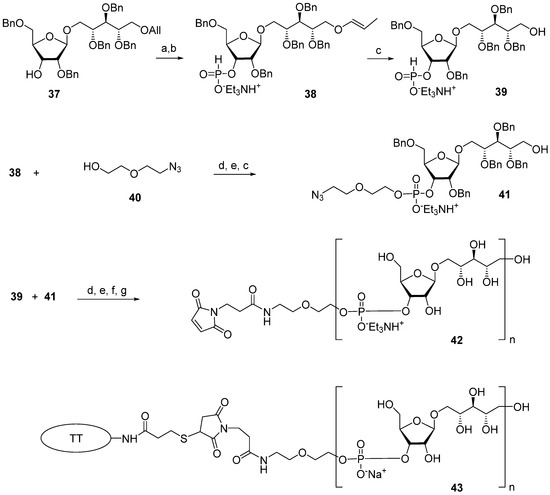

The multistep synthetic pathways discussed above are based on the linear sequential elongation of an oligomeric chain. As a rule, laboratory processes of this type cannot be scaled up to a commercial scale because of the high cost. For profitable manufacturing, a convergent synthetic scheme is needed. Under the leadership of Verez-Bencomo and Roy, a convergent synthesis of a mixture of homologous PRP oligomers (Figure 4, compound 10) was developed and then scaled up to the commercial production of the anti-Hib vaccine Quimi-Hib® (Heber Biotec, S.A., Republic of Cuba). In this synthesis, polycondensation of a bifunctional monomer is employed for the establishment of O-P-O linkages as a key step of oligomer synthesis in the place of stepwise elongation (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Key building blocks for preparation of oligomeric mixture 10 (n= 6–9) [68]. Reagents and conditions: (a) potassium tert-butoxide/DMSO, 100 °C; (b) PCl3, imidazole, Et3N; (c) CH3COOH/H2O, 80 °C; (d) PivCl/Py; (e) I2, Py/H2O; (f) H2, Pd/C, EtOH-H2O-EtOAc-AcOH at 1.5 atm; (g) SMP.

In brief, the allyl group of the selectively protected pseudo-disaccharide 37 is isomerized into the 1-O-propenyl group by the action of potassium tert-butoxide in DMSO. The resulting isomer is converted to H-phosphonate 38 by the action of PCl3 and imidazole, and finally, the 1-O-propenyl group is removed under acidic conditions to obtain the key heterobifunctional monomer 39. The interaction of 38 with the diethylene glycol spacer 40 in the presence of PivCl/Py, followed by oxidation with iodine in aqueous Py, and the further removal of the 1-O-propenyl group, creates alcohol 41, which serves as a terminal unit in the polycondensation. The polycondensation of 39 and 41 is carried out in the presence of PivCl in Py, followed by oxidation of the mixture of H-phosphonates into the corresponding phosphodiester mixture, reduction of the azido groups, N-acetylation, and total deprotection. The obtained mixture of the spacer-equipped oligomer 10 is activated by the action of SMP to obtain a conjugation-ready mixture of maleimide 42. The conjugation of the activated oligophosphodiesters with thiolated TT results in the production of a set of conjugate 43 with the average weight ratio PRP:TT of 1:2.6 [31,68].

On the basis of the mixture of conjugate 43, an anti-Hib vaccine, Quimi-Hib®, was developed, which successfully passed all the required preclinical [73] and clinical trials [31,74]. The antigenicity of synthetic PRP oligomer 10 was compared to the antigenicity of bacterial PRP in ELISA experiments [31]. A conjugate of a mixture of the spacer-equipped oligomer 10 with HSA (10-HSA), prepared similarly to conjugate 43, and a conjugate of partially depolymerized bacterial PRP (PRPDp30) with HSA were used as coating antigens. The PRPDp30-HSA conjugate was obtained by the reductive amination of the mixture of bacterial PRP depolymerized via periodate oxidation to a length of ~30 monomeric units and conjugation with HSA [68]. Standard rabbit anti-PRP antibodies were obtained by the immunization of animals with two licensed commercial conjugate vaccines based on bacterial PRP. These were Hiberix® (PRP-TT), which contains PRP activated by cyanogen bromide and conjugated to TT via an adipic acid dihydrazide linker, and Vaxem-Hib® (PRP-CRM197), which is a product of the conjugation of partially depolymerized bacterial PRP with an avDP10 repeating unit and the protein carrier CRM197 via an adipic acid dihydrazide spacer. The correlation coefficient for the titers obtained in the ELISA experiments with standard rabbit sera and the coating antigens 10-HSA and PRPDp30-HSA was in the high-value range (0.972–0.978), indicating the similarity of the antigenic properties of the synthetic oligosaccharide 10 and Hib CPS [75].

For the preliminary evaluation of the immunological activity of the conjugate 43 in vivo, rats, mice, and rabbits were chosen as experimental animals. Rats were immunized subcutaneously twice at an interval of 4 weeks with a dose of conjugate 43 containing 2 µg of the ligand 10 [75]. Mice were immunized intraperitoneally three times at an interval of 2 weeks with a dose of conjugate 43 containing 2.5 µg of ligand 10. Rabbits were immunized with conjugate 43 using both two-step and three-step regimens at a dose of 5 µg of ligand 10 per animal. The efficiency of immunization was assessed by the evaluation of IgG titers, which were calculated as the logarithm of the highest dilution at which the light absorbance of the diluted serum sample is twice as high as that of the negative control. For the negative control, the animals were injected with PBS. A PRP-HSA conjugate was used as a coating antigen in the ELISA experiments. The study of the PRP-specific antibodies showed that the immune response to conjugate 43 in rodents was weak and inconsistent. In contrast, the immunization of rabbits with conjugate 43 efficiently evoked PRP-specific antibodies, as shown in the inhibition ELISA experiments with bacterial PRP as the inhibitor [75].

In a phase 1 clinical trial [31], more than 100 children aged 4 to 5 years were immunized with a single dose of a vaccine preparation formulated on the basis of conjugate 43 without an adjuvant. Comparative studies of the immunogenicity of synthetic antigens in conjugate 43 and partly depolymerized bacterial PRP in Vaxem-Hib® showed that the average anti-PRP IgG titers were similar. It was found that PRP-specific IgG antibodies induced in children by immunization with conjugate 43 had bactericidal activity comparable to that stimulated by the action of Vaxem-Hib®. In the course of phase 2 clinical trials [31], 1141 infants were immunized three times at 2, 4, and 6 months of age with or without AlPO4, and the positive control group was immunized with Vaxem-Hib®. Antibody tests showed that 99.7% of infants had serum anti-PRP IgG concentrations >1 µg/mL, which is known to provide prolonged protection against Hib infection [76], and the mean concentration of anti-PRP IgG was as high as 27.4 µg/mL.

It is noteworthy that in Quimi-Hib®, different-sized oligomeric antigens were present, thus circumventing the problem of the elucidation of the optimal length of an oligomeric PRP antigen. The success of the development and application of the cost-effective vaccine Quimi-Hib® with a synthetic Hib-antigen inspired scientists to search for the shortest protective Hib-antigen, which is likely to be in the range of chain lengths that are obtained during the polycondensation of 39.

One of the novel and efficient approaches to the preparation of PRP-related oligomeric phosphoglycans suggested by Seeberger et al. [69] involved the elongation of the chain by two PRP repeating units at once (Scheme 6). The applied strategy effectively shortened the task of the oligomer assembly and raised the degree of convergence.

Scheme 6.

Key building blocks for preparation of oligomers 12–15 [69]. Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd(PPh3)4, 1,3-dimethylbarbituric acid, methanol, 75%; (b) DMTCl, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 93%; (c) PCl3, Et3N, imidazole, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 85%; (d) levulinic acid, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 93%; (e) 46, PivCl, Py, 0 °C; (f) I2, Py/H2O, 85%.

For the preparation of a selectively protected and activated bifunctional dimeric key unit, the universal precursor 44 was deallylated, and the resulting diol was regioselectively 4,4′-dimethoxytritylated at the primary hydroxyl group to obtain compound 45, which was then converted to H-phosphonate 46 by the action of PCl3, Et3N, and imidazole. For the preparation of alcohol 47, the universal precursor 44 was levulinoylated and deallylated. Alcohol 47 was reacted with H-phosphonate 46 in PivCl/Py to obtain the key dimeric precursor 48 with readily removable orthogonal levulinoyl and dimethoxytrityl protective groups. The de-4,4′-dimethoxytritylation of pseudo-tetrasaccharide 48 in the presence of trichloroacetic acid afforded alcohol 49 with a free terminal hydroxyl group in the ribitol residue. The delevulinoylation of universal precursor 48 by the action of hydrazinium acetate resulted in the formation of alcohol 50, which was converted into H-phosphonate 51. The combination of H-phosphonate 51 and primary alcohol 49, followed by oxidation, yielded a tetramer, which was, in turn, de-4,4′-dimethoxytritylated and reacted with H-phosphonate 46 for the elongation of the chain or with the 5-azidopentyl derivative 52 for chain termination. Using this elegant strategy, PRP-related tetramer (85%), hexamer (85%), octamer (83%), and decamer (80%) were prepared, which were subjected to sequential detritylation, the attachment of a 5-azidopentyl spacer under the action of H-phosphonate 52, the transformation of the azido group into an amino group, and total deprotection to obtain the spacer-armed oligomers 12–15 (Figure 4). After activation, oligomers 12–15 were reacted with TT to obtain conjugates 53–56 [69].

The antigenicity of oligomers 11–15 (Figure 4) was examined using a glycan microarray. Compounds 11–15 were immobilized on a N-hydroxysuccinimide hydrogel surface on glass slides and reacted with polyclonal anti-Hib hyperimmune rabbit sera or standard human sera, which were mixed with different concentrations of the WHO PRP standard as an inhibitor. The subsequent addition of a fluorescent secondary antibody revealed the dependence of the fluorescence intensity on the PRP concentration, thus proving the presence of antibodies specific to the synthetic PRP-oligomers 11–15. Hexamer 13, octamer 14, and decamer 15 interacted with standard human sera in a similar way, binding with tetramer 12 was weaker, and in the case of dimer 11, the adsorption of the antibodies was even less effective. In contrast, rabbit hyperimmune sera interacted with all five oligomers equally well [69].

The immunogenicity of conjugates 53–56 was studied using an animal model. Rabbits were immunized with these conjugates at a dose of 5 μg of an oligomer without an adjuvant, and the positive control group received ActHib® (PRP-TT). Bacterial PRP was used as a coating antigen. Immunization with conjugates 53 and 55, based on tetramer 12 and octamer 14 ligands, respectively, resulted in a high level of PRP-specific antibodies. Conjugates 54 and 56, which comprised hexamer 13 and decamer 15, induced substantially lower levels of PRP-specific antibodies [69]. Therefore, in a series of conjugates equipped with antigens with an even number of repeating units, the tetramer was the most promising synthetic antigen candidate for the design of an anti-Hib vaccine.

In a continuation of this work, Seeberger et al. synthesized [77] a series of mimetics of synthetic PRP-related dimer, tetramer, hexamer, and octamer compounds (11–14), which comprised 2-deoxy-, 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-, 2-deoxy-2-(N,N-dimethyl)-carbamoyloxy-, and 2-O-methylated ribose residues in different combinations. This research was aimed at the preparation of analogs of PRP antigens with higher hydrolytic stability. The study of the conjugates of these antigens with the protein carrier CRM197 showed that the most promising are mimetics, in which ribose residues are methylated at the position O-2. Conjugates of these mimetics with CRM197 stimulated Hib-specific immune responses in both animals and humans, which confirms the possibility of their commercial use in anti-Hib vaccines. The replacement of the 2-OH group, which promotes the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond, with a methoxy group allowed for a significant increase in the integrity of the antigen [77].

3. Synthesis of Oligomers Structurally Related to Capsular Phosphoglycans of Hia, Hic, and Hif

Hib bacteria are the common and most dangerous serotype of the H. influenzae species, which comprises at least five more encapsulated serotypes and numerous non-capsulated (non-typeable) variants. The introduction of anti-Hib conjugate vaccines [13,15,21,23] in national immunization schedules in a number of European countries, North and South America countries, Australia, and the South African Republic significantly contributed to a reduction in invasive diseases caused by Hib-infection [78,79]. At the same time, along with the expansion of anti-Hib vaccination programs, the spread of other serotypes of H. influenzae was reported [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. As a consequence, after more than thirty years’ use of anti-Hib conjugate vaccines, an “antigenic shift” is observed, which is expressed in the increased incidence of invasive diseases, including meningitis, meningoencephalitis, and septicemia caused by encapsulated H. influenzae serotypes different from b [82,90].

In European countries, the number of invasive diseases caused by Hia is also growing. For example, in England, in 2022, Hia was responsible for 19% of all invasive disease cases caused by encapsulated H. influenzae. Before 2017, only sporadic cases occurred [80], and the contribution of Hif and Hie is also growing [90]. In South Africa, the rise of Hie is observed [82]. In American countries, H. influenzae diseases are often caused by Hif [82,91]. Also, an increase in invasive diseases caused by Hia [85,89,92,93] and Hic [91] was reported.

In the early 1990s, in the northern regions of Canada and Alaska, a routine anti-Hib immunization schedule was introduced, and in the late 1990s, a growing number of cases of Hia infection were registered. The majority of cases (more than 60%) were reported in children under five years of age. As a result, special research is being conducted in Canada aimed at the development of a vaccine for the prevention of diseases caused by Hia [84]. Considering that invasive diseases caused by encapsulated H. influenzae serotypes different from serotype b remain relatively rare and are often localized in specific areas, corresponding vaccines will have limited use according to epidemic indications. In this situation, conjugate vaccines with synthetic antigens structurally related to H. influenzae capsular glycans may be considered as a drug of choice.

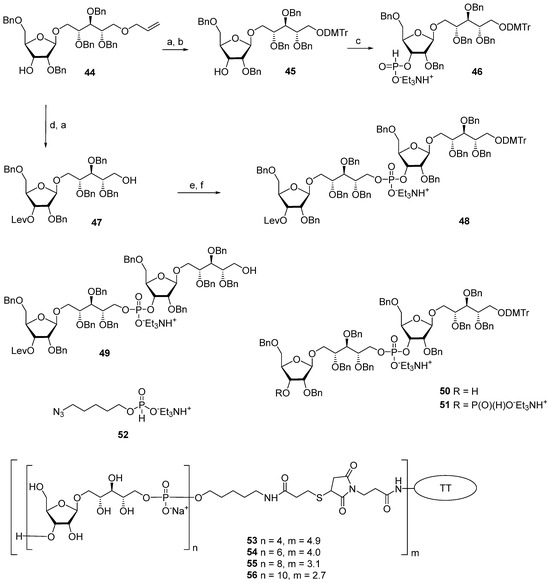

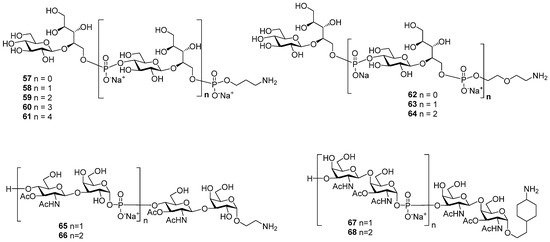

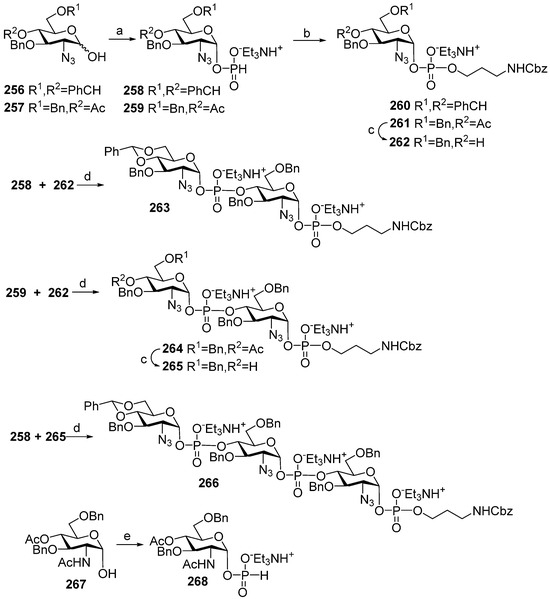

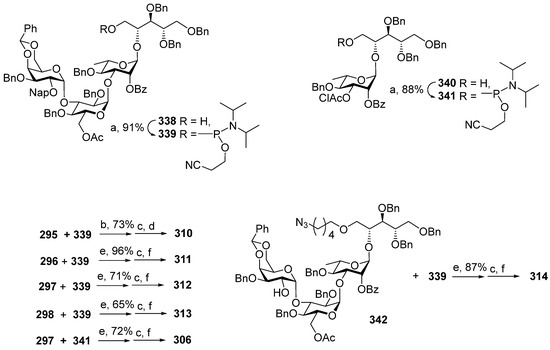

Inspired by the success of the Quimi-Hib® vaccine, which comprises synthetic oligomeric phosphoglycans structurally related to Hib capsular phosphoglycan, researchers synthesized [94,95] the series of oligomers 57–61 with one, two, three, four, and five repeating units of Hia capsular phosphoglycans and 3-aminopropyl linkers (Figure 6). In another recent study, the series of fragments of Hia capsular phosphoglycans 62–64 equipped with a 66 diethyleneglycol linker was obtained [96] (Figure 6). Syntheses of aminoalkyl glycosides related to the Hic phosphoglycan (compounds 65 and 66) and related to the Hif phosphoglycan (compounds 67 and 68) were performed by Oscarson et al. [97].

Figure 6.

Synthetic oligomers 57–61 [94] and 62–64 related to Hia capsular phosphoglycans [96], oligomers 65 and 66 related to Hic capsular phosphoglycans, and oligomers 67 and 68 related to Hif capsular phosphoglycans [97].

In the two series of the spacer-armed oligomers 57–61 [94] and 62–64 [96] structurally related to Hia capsular phosphoglycans, the linker is connected to the glycan antigen via a phosphodiester bridge. Compounds in both series were prepared using a convergent synthetic strategy with iterative elongation of the linear structure starting from the non-reducing end, and finally, the spacer was added (Scheme 7 and Scheme 8). The major difference between the syntheses of these two series is the type of universal, selectively protected bifunctional synthon. In the preparation of oligomers 58–61 [94], a monomer block with a phosphoramide group at C-4 (Glc) was used, and for compounds 63–64 [96], the synthetic pathway involved the use of a non-phosphorus monomer.

Scheme 7.

Key building blocks for the synthesis [94] of oligomers structurally related to Hia capsular phosphoglycans. Reagents and conditions: (a) CH2Cl2, r.t., 98% for compound 71 and 95% for compound 73; (b) DCI, CH2Cl2, 4Å molecular sieves; (c) CSO; (d) 0.18M TCA in CH2Cl2, 79% over 3 steps.

Scheme 8.

Key blocks for synthesis of oligomers structurally related to Hia phosphoglycans [96]. Reagents and conditions: (a) acetic anhydride, DMAP, Py; (b) HF (aq.), Py, 60 °C, 97% for two stages; (c) H3PO3, PivCl, Py, 74%; (d) ZNH(CH2)2O(CH2)2OH, PivCl, Py; (e) I2, Py/H2O.

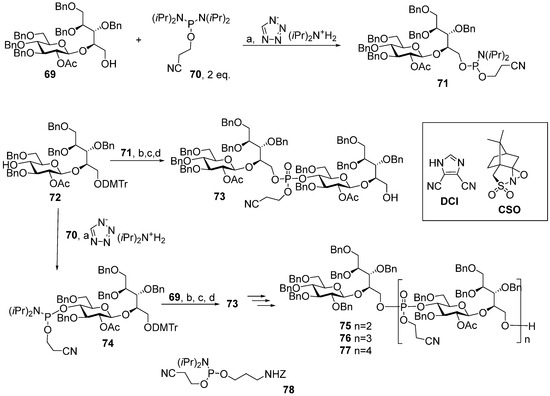

For the choice of the optimum strategy for the assembly of oligomers 57–61 (Scheme 7) [95], two alternative ways were considered. The first strategy involved pseudo-disaccharide 69 with a free hydroxyl group in the ribitol residue, which was reacted with 2-cyanoethyl N,N,N′,N′-tetraisopropylphosphordiamidite (compound 70) in the presence of diispropylammonium tetrazolide to obtain the selectively protected phosphoramidite 71 as a universal precursor with a 95% yield. The following condensation of phosphoramidite 71 and glycoside 72 with a free hydroxyl group at C-4 (Glc), oxidation of a phosphite into a phosphodiester, and detritylation created the conjugation-ready dimer 73 with a 73% yield over three steps.

Another way of preparing phosphotriester 73 (Scheme 7) employed phosphoramidite 74 with a pro-phosphodiester group located at C-4 (Glc). The sequential combination of phosphoramidite 74 with alcohol 69, oxidation, and detritylation resulted in the formation of the phosphodiester block 73 with a 79% yield over three steps [94,95]. Therefore, both assembly strategies were equally effective. Starting with phosphoramidite 74, protected pseudo-oligosaccharides 75–77 were obtained and then converted to ligands 58–61 by interaction with the pre-spacer phosphoramidite 78 and total deprotection. The authors pointed out that in comparison to the H-phosphonate approach, the phosphoramidite protocol was more efficient for the construction of longer phosphodiester-linked chains. Oligomers 57–61 were N-acylated with a di(N-hydroxysuccinimidyl) adipate linker, and the activated esters were conjugated to CRM197. The resulting conjugates contained 13–25 copies of the oligomeric antigen per CRM197 unit. Rats were immunized with three doses, which contained 2 μg of the glycan antigen, and the IgG antibodies were analyzed in the sera using ELISA. Conjugates of trimer 59 and pentamer 61 with HSA were used as coating antigens. All the conjugates were immunogenic and induced similar levels of IgG antibodies, which recognized immobilized synthetic antigens. The researchers noted that the immunogenicity data for the CRM197-based conjugates of oligomers 57–61 was independent of the length of the oligomeric antigen [95].

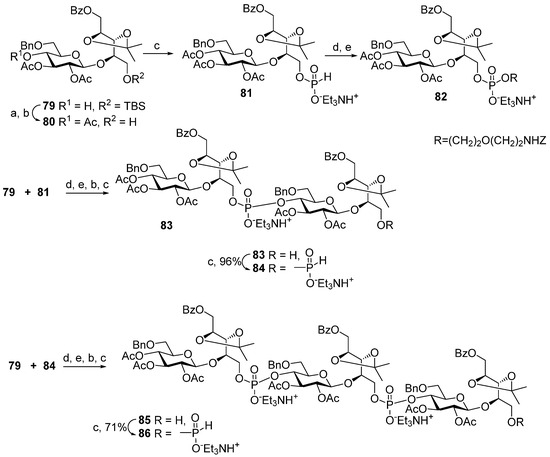

Compounds 62–64 [96] were prepared (Scheme 8) starting from the universal precursor pseudo-disaccharide 79. The acetylation of compound 79 resulted in acetate 80, which was phosphitylated to obtain key monomeric H-phosphonate 81 with a 97% yield. The condensation of H-phosphonate 81 with a pre-spacer N-carbamoyl aminopropanol, as shown in Scheme 8, created phosphodiester 82 (yield: 34%), which, after the removal of the protective groups, was transformed into the spacer-armed target monomer 62 (Figure 6). To obtain dimer 83, alcohol 79 was condensed with H-phosphonate 81 with a 77% yield and then oxidized. Phosphodiester 83 was, in turn, converted into H-phosphonate 84. The interaction of H-phosphonate 84 with alcohol 79 produced phosphodiester 85, which was converted into H-phosphonate 86. Spacer-armed derivatives were obtained by the interaction of H-phosphonates 84 and 86 with N-carbamoyl aminopropanol to obtain, after total deprotection, the spacer-armed dimer 63 and trimer 64, respectively (Figure 6). It is interesting to note that the efficiency of condensation with N-protected aminopropanol increased in the series 81 > 84 > 86 with the rise in the number of phosphodiester fragments present in these H-phosphonates, whereas numerous experimental data suggest the opposite [39].

In 2001, Oscarson et al. synthesized the amino spacer-armed oligomeric fragments of Hic (compounds 65 and 66) and Hif (compounds 67 and 68) phosphoglycans [97] (Figure 6), in which the repeating disaccharide units are linked via a phosphodiester bridge. Similar to the block syntheses of Hib and Hia fragments described above, the establishment of a phosphodiester linkage between selectively protected oligosaccharide blocks was used for the chain elongation. However, unlike Hib and Hia, in Hic and Hif capsular phosphoglycans, the anomeric carbons in hexoses are involved in the formation of a phosphodiester bridge. Therefore, the development of a synthetic strategy for the preparation of Hic and Hif fragments has to be developed with respect to the possibility of the formation of an unwanted anomer. At the step of chain assembly, it can be particularly difficult to provide stereocontrol in the formation of a C-1-O-P bond. Instability of the anomeric phosphodiester linkage also has to be considered, which makes it possible to use anomeric phosphodiesters as glycosyl donors in the glycosylation reaction. A convenient strategy for the preparation of the desired anomer includes the initial stereocontrolled glycosylation of a phosphodiester synthon, which provides an intermediate product with the target anomeric configuration, and the subsequent coupling of this compound in mild conditions for the prevention of anomerization. These conditions are met in the H-phosphonate protocol, as hexose hemiacetals retain the anomeric configuration, while they are transformed into H-phosphonates upon the action of triimidazolyl phosphine prepared in situ from PCl3 and imidazole in the presence of Et3N [39].

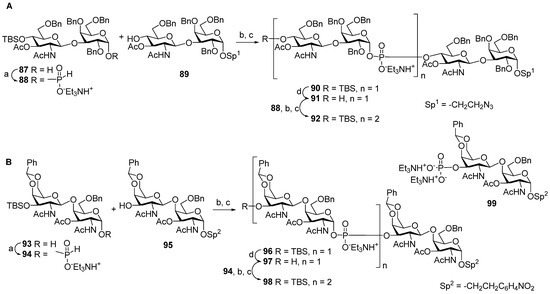

For the preparation of the spacer-armed oligomers 65 and 66 (Figure 6) [97], which are structurally related to Hic phosphoglycans, hemiacetal 87 with an axial hydroxyl group at C-1 was converted into the key α-H-phosphonate 88 (yield: 89%), which was condensed with the selectively protected alcohol 89 and oxidized with I2 (Scheme 9A) to provide phosphodiester 90 (yield: 71%). The desilylation of phosphodiester 90 produced alcohol 91, which was readily condensed with α-H-phosphonate 88, and the phosphite group was oxidized to produce phosphate 92 in a moderate yield (36%). After total deprotection, the reduction of the azido group, and the N-acetylation of compounds 91 and 92, the target spacer-armed phosphooligosaccharides 65 and 66 were obtained.

Scheme 9.

(A) Key blocks 87–92 for the synthesis of oligomers [97] 65 and 66 related to Hic phosphoglycans; (B) key blocks 93–98 for the synthesis of oligomers 67 and 68 related to Hif phosphoglycans. Reagents and conditions: (a) PivCl, Py; (b) PCl3, imidazole, Et3N, 85%; (c) I2, Py/H2O, -40 °C; (d) Et3N(HF)3.

Analogously, the favorable α-configuration of the GalNAc hemiacetal residue in disaccharide 93 (Scheme 9B) paved the way to the preparation of the spacer-armed phosphooligosaccharides 67 and 68 related to Hif phosphoglycans [97]. Upon action with PCl3 and imidazole, hemiacetal 93 was transformed into α-H-phosphonate 94 with a retention of configuration (yield: 87%). The condensation of α-H-phosphonate 94 with disaccharide 95 and the subsequent oxidation resulted in the efficient formation of phosphodiester 96 (yield: 81%), which was desilylated to obtain alcohol 97. Similar to the condensation of compounds 91 and 88, the interaction of 97 and 94 was less efficient, and phosphodiester 98 was obtained with a 37% yield. Most likely, low yield in this reaction is associated with the high lability of the phosphodiester group in acceptors 91 and 97 in the conditions of oxidation with I2 [39]. The authors [97] observed the formation of a significant amount (up to 40%) of 3′-O-phosphate 99, which indicates the lability of a glycosyl-O-phosphodiester tether under oxidation conditions. The low yields of attachment of the second glycosyl-phosphodiester residue for variants A and B, shown in Scheme 9, suggest that the stability of a phosphodiester bond is largely determined by the condensation and oxidation conditions and is less dependent on the structure of disaccharide residues. The target spacer-armed phosphooligosaccharides 67 and 68 were obtained after complete deblocking of the compounds and the reduction of the nitrophenyl residue into an aniline residue.

In view of the development of an anti-Hia vaccine, two aspects have to be addressed. Similar immunogenic properties of synthetic Hia antigens from monomer to pentamer can be connected with the low stability of phosphodiester linkages in aqueous solutions. In this case, the design of a vaccine may require a mimetic structure for the antigen. Also, it is advisable to use a phosphoramidite-based strategy for the preparation of phosphooligosaccharide antigens for industrial production, as the considered examples demonstrate the advantage of the phosphoramidite-based method over the H-phosphonate procedure. Meanwhile, anti-Hic and anti-Hif conjugate vaccines are not considered to be of high importance in contemporary glycoscience, as researchers have not referred to this topic for more than 20 years.

4. Synthesis of Phosphooligomers Related to Capsular Phosphoglycan of MenA

In 2010, a conjugate polysaccharide meningococcal monovalent vaccine, MenAfriVac® (MenA-TT), was licensed [98,99]. In contrast to meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines, the conjugate preparation was found to be highly effective. For example, the results of mass vaccination campaigns in African meningitis belt countries that were carried out in 2010–2015 showed more than a 99% decrease in the incidence of MenA-associated meningitis [100]. Today, MenA phosphoglycan is a component of a number of polyvalent conjugate meningococcal vaccines, including Menactra® (A-meningococcal component MenA-diphtheria toxoid), Menveo® (A-meningococcal component MenA-CRM197), and Nimerix® (A-meningococcal component MenA-TT) [14].

Polymer chains of MenA phosphoglycan are highly labile in aqueous media [63]. This intrinsic property of MenA phosphoglycan creates the need for the cold-chain transport of conjugate anti-MenA vaccines [101], which significantly increases the cost per dose and, in some cases, is an insurmountable obstacle to the use of this type of preparation [102]. Also, this feature imposes additional requirements on the production of both monovalent vaccines and polyvalent vaccines in a convenient liquid form. In this regard, considerable research efforts have been directed towards the synthesis of oligomeric antigens structurally related to MenA CPS fragments or corresponding mimetics with a view to preparing commercial conjugate vaccines. The use of anti-MenA conjugate preparations with a synthetic oligoside antigen, the structure of which fully corresponds to MenA CPS fragments, could allow the monitoring of the structural integrity of this preparation during storage and transportation, and the design of an antigen using ManNAc phosphate mimetics obtained by replacing the oxygen atom with the methylene group in the pyranose ring with (carba-analogs) or by replacing the anomeric oxygen atom with a methylene group (C-phosphonates) will make the antigen structure resistant to hydrolysis.

It is important to emphasize that in MenA bacterial phosphoglycans, ~80% of 3-OH groups and ~10% of 4-OH groups in ManNAc residues are acetylated [103]. A study of phosphoglycan structures present on the surface of a living MenA bacterial cell [104], which was conducted using high-resolution magic-angle spinning, showed the presence of acetyl substituents at 50–60% of 3-OH groups and 25–30% of 4-OH groups. The acetylation of MenA phosphoglycans is known to be an important antigenicity factor [105,106].

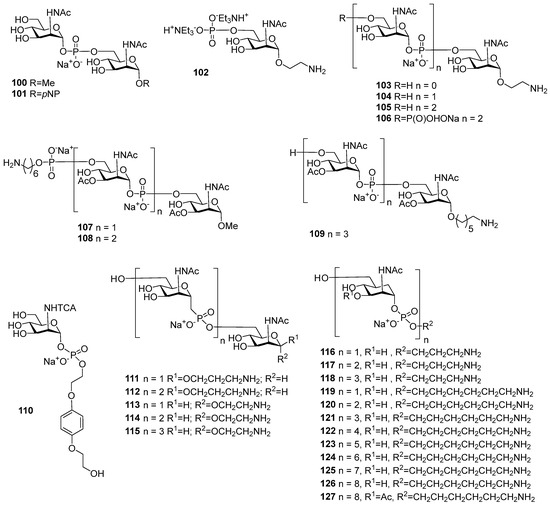

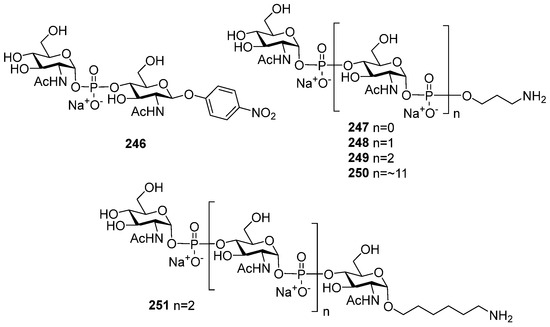

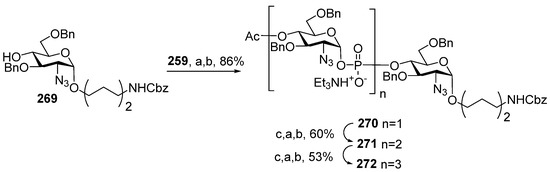

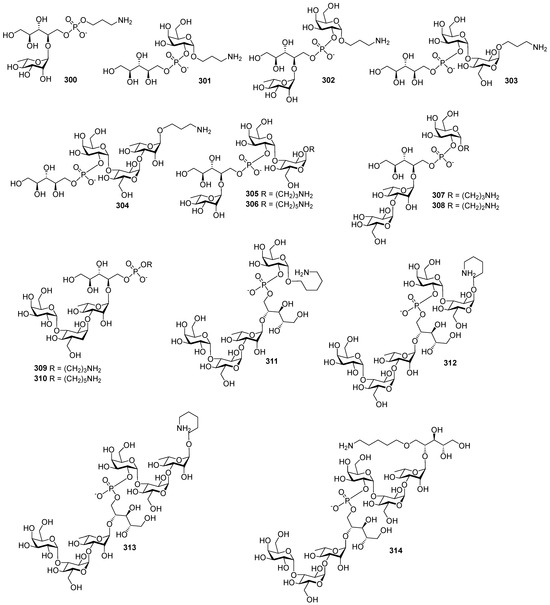

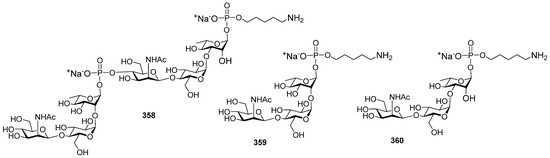

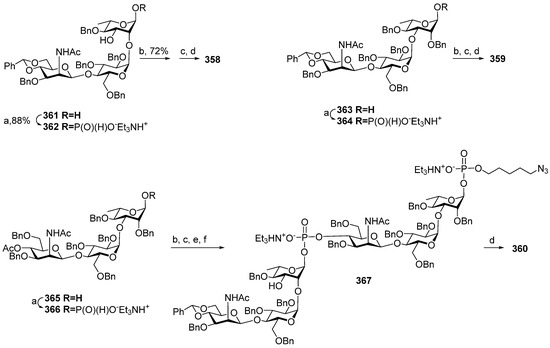

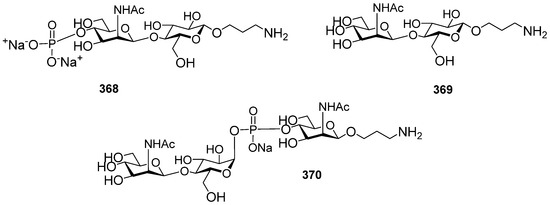

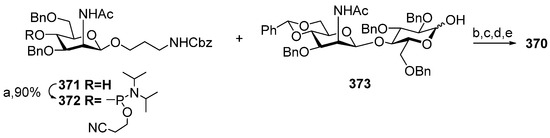

Spacer-armed synthetic antigens structurally related to the MenA capsular phosphoglycan and the corresponding phosphono- and carba-analogs are attractive synthetic compounds considering their potential use as ligands in marketed meningococcal vaccines. Since the first time a phosphodiester bridge was arranged between two αManNAc residues (Figure 7, compounds 100 and 101) in 1993 by the Shibaev group [107], a vast number of MenA-related mono-, di-, and oligosaccharides 102–109 (Figure 7) have been synthesized [108,109,110,111,112]. However, the preparation of αManNAc anomeric phosphodiesters remains a challenge, as these compounds comprise a highly labile linkage between C-1 and O-1 of αManNAc, which is, in addition, destabilized by the presence of the NHAc group at C-2 of αManNAc. As a result, researchers have focused significant efforts on the design of hydrolytically stable phosphono-mimetics (compounds 111–115) [113,114,115] and carba-mimetics (compounds 116–127) [116,117,118]. However, new challenges are emerging, which are associated with the establishment of C-C bonds and the stereoselective formation of new chiral centers. The majority of publications that describe the preparation of oligomeric antigens related to MenA phosphoglycans concern nonacetylated molecules, whereas bacterial MenA phosphoglycans comprise the acetyl groups at O-3/O-4 (Figure 6), which are important for the antigenic properties of the polymer [105,106]. Additionally, a number of synthetic MenA-related antigens were reported (compounds 107–109 and 127), which are totally or partially acetylated at O-3 of αManNAc, with a view to bringing their antigenic properties closer to those of the bacterial antigen. Synthetic fragments of MenA phosphoglycans with 3,4-di-O-acetylated αGManNAc residues are not considered in this review.

Figure 7.

Synthetic oligosaccharides structurally related to MenA phosphoglycans.

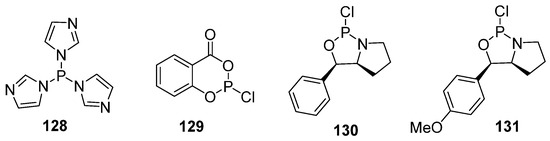

As the capsular MenA glycan is an αManNAc(1→(-PO3)→6) polymer, the H-phosphonate method is applicable, provided that 1-OH has the axial orientation in the selectively protected H-phosphonate ManNAc or 2-deoxy-2-azido mannose precursor, as described above for oligomers related to Hic and Hif phosphoglycans (Scheme 9). A number of convenient and efficient procedures have been developed for the preparation of this type of compound. The common protocol suggests phosphitylation with tri(1-imidazolyl) phosphine (Figure 8, compound 128), which is obtained in situ by the interaction of PCl3 and imidazole in the presence of Et3N and salicylchlorophosphite 129 (2-chloro-4H-1,3,2-benzodioxaphosphin-4-one; Figure 8). Alternatively, within a phosphoramidite protocol, chloroanhydrides 130 and 131 (Figure 8) were especially designed for automated synthesis to produce stable phosphoramidites as synthons of α-mannosamine phosphodiesters [108].

Figure 8.

Reagents used for synthesis of H-phosphonates.

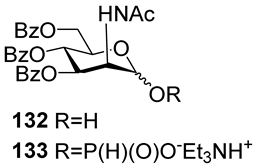

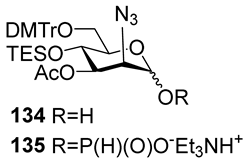

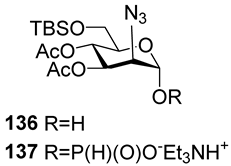

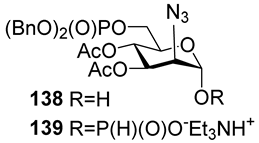

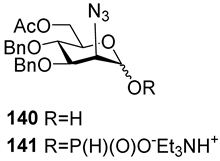

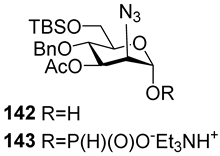

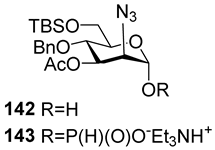

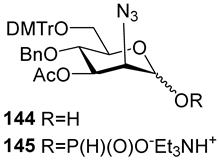

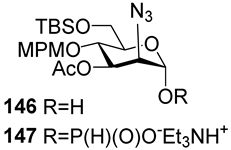

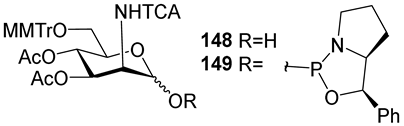

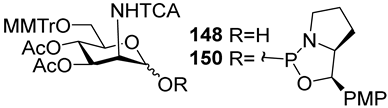

For the PCl3/imidazole protocol, the key prerequisite for the preparation of ManNAc or 2-deoxy-2-azido mannose α-H-phosphonates is the α-configuration of the 1-OH group in the corresponding selectively protected hemiacetal. This feature imposes certain restrictions on the use of the H-phosphonate protocol. Hemiacetal 132 (Table 1) with a 5:1 ratio of α/β anomers was quantitatively converted into the 5:1 mixture of α- and β-isomeric H-phosphonate 133 upon the action of PCl3 and imidazole in acetonitrile at 0 °C, followed by hydrolysis with an aqueous solution of Et3NH∙HCO3 at 20 °C (Table 1, entry 1) [107]. In a similar way, phosphitylation of the mixture of hemiacetal 134 with a 3.5:1 ratio of α/β anomers in analogous conditions proceeded with the retention of the configuration of the anomeric center and resulted in the formation of the mixture of H-phosphonate 135, with the α:β ratio 3.5:1 and an 88% yield (Table 1, entry 2) [110]. In similar conditions, the interaction of the α-anomer of hemiacetal 136 (Table 1, entry 3) [111] afforded α-H-phosphonate 137 with a 97% yield, and hemiacetal 138 with a dibenzyl phosphate group at C-6 was converted into α-H-phosphonate 139 (Table 1, entry 4) [111]. The phosphitylation of hemiacetal 140 (Table 1) with an α-configuration of the anomeric center upon the action of (PhO)2P(O)H in Py, followed by hydrolysis, resulted in a mixture of α- and β-isomer 141 in a ratio of 93:3 (Table 1, entry 5) [112]. Similarly, the phosphitylation of α-hemiacetal 142 in these conditions formed α-H-phosphonate 143 with a 78% yield (Table 1, entry 6) [109]. Anomeric mixtures of hemiacetals, which contain considerable quantities of β-isomers, can be efficiently converted into α-H-phosphonates with chlorophosphite 129 (Figure 8) [110,119]. For example, the phosphitylation of the anomeric mixture 144, with a ratio of α- and β-anomers of 4.5:1, was transformed into α-H-phosphonate 145 by the action of chlorophosphite 129 in a mixture of dioxane and triethylamine with an 88% yield (Table 1, entry 8) [110]. Similarly, in these conditions, hemiacetals 142 and 146 were converted into the corresponding α-H-phosphonates 143 and 147 at 91 and 90% yields, respectively (Table 1, entries 7 and 9) [110,119]. Unlike H-phosphonates, phosphoramidites are rarely used as synthetic blocks for the establishment of phosphodiester bonds between α-ManNAc residues because of their utmost lability. Two successful examples of ManNAc phosphoramidites are compounds 149 and 150, which are stabilized by rigid oxazaphospholidine substituents. These compounds were obtained from the anomeric mixture of hemiacetal 148 by the action of tricyclic chlorophosphoroamidites 130 and 131 at yields of 36 and 39% (Table 1, entries 10 and 11), respectively [108]. The generation of α-H-phosphonates and the anomerization of the α/β mixtures of hemiacetals or the stereoselective cleavage of the unwanted β-isomer in the presence of H3PO3 [107] or AgOTf [110] were ineffective.

Table 1.

Synthesis of H-phosphonates and phosphoramidites from selectively protected 2-deoxy-2-azido-D-mannose and ManNAc hemiacetals.

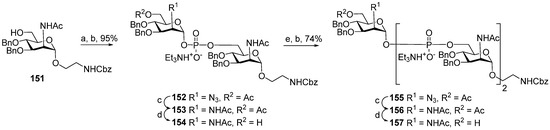

The majority of syntheses of the spacer-armed oligomers related to MenA phosphoglycans (Figure 7) were performed using a straightforward and efficient protocol suggested by Van Boom [120], which constitutes the condensation of H-phosphonates with alcohols, with the subsequent oxidation of phosphites into phosphodiesters. In the first step, the dissolved alcohol is activated by the addition of sterically hindered chloroanhydride, e.g., PivCl, followed by the addition of H-phosphonate in Py and stirring for 5–30 min. In the second step, the intermediate products are subjected to oxidation with a 0.5 M solution of I2 in a Py:H2O mixture within the temperature interval from −40 °C to 0 °C for 30 min. The first syntheses of the non-acetylated fragments of MenA phosphoglycans as methyl glycoside 100 and nitrophenyl ether 101 were accomplished by the Shibaev group [107] using the H-phosphonate protocol (Figure 7). Then, monomers 102 and 103, dimer 104, and trimer 105 (Figure 7), related to MenA phosphoglycans and equipped with a spacer carrying a primary amino group for conjugation with protein carriers, were synthesized by Pozsgay et al. [112]. The condensation of H-phosphonate 141 with alcohol 151, with subsequent oxidation, resulted in the formation of phosphodiester 152 with a yield of 95% over two steps (Scheme 10). The successive reduction of an azido group into the amino group and N-acetylation yielded mannosaminyl phosphodiester 153, which was converted into alcohol 154 by chemoselective 6-O′-deacetylation. The condensation of H-phosphonate 141 and alcohol 154 was less effective (a yield of 74% over two steps) in connection with the destruction of the phosphodiester bond in the reaction conditions. The authors noted that attempts at further elongation of the chain were unsuccessful. Phosphoester 102 and phosphodiesters 103, 104, and 105 were converted into conjugates with HSA. The antigenic properties of the conjugates were confirmed by a double immunodiffusion assay with the MenA phosphoglycan as a positive reference and chemically modified HSA as a negative reference, and anti-MenA horse serum [112].

Scheme 10.

Key building blocks for the synthesis of oligomers 103, 104, and 105 related to MenA phosphoglycans [112]. Reagents and conditions: (a) 141 (0.8 eq.), PivCl (2.2 eq.), 23 °C, 30 min. Py; (b) I2 (2.2 eq.), Py:H2O 95:1, 0 °C, 30 min, 95% yield over 2 steps; (c) NiCl2∙6H2O (4.8 eq.), NaBH4 (8.0 eq.), methanol, 0 °C → 10 °C, 30 min; (d) NaOMe/MeOH; (e) 141 (1 eq.), PivCl (1.5 eq.), Py, 23 °C, 5 min.

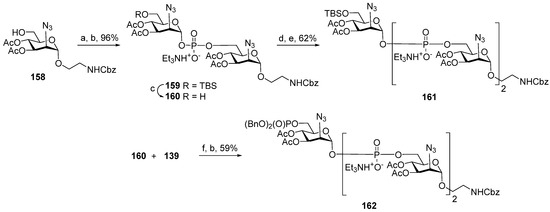

In 2005, the non-acetylated spacer-armed MenA phosphoglycan-related oligomer 105 (Figure 7), which comprises three ManNAc residues connected by phosphodiester bridges and trimer 106 (Figure 7), composed of three non-acetylated MenA repeating units, was synthesized by the Oscarson group [111]. In contrast to the abovementioned synthetic strategy designed by the Pozsgay group, which suggested the reduction of the azido group and N-acetylation after each chain elongation step (Scheme 10), 2-azido glycoside 158 was used as a starting unit for further chain elongation, and 2-azido H-phosphonate 137 (Table 1, entry 3) was applied as a repeating unit synthon without intermediate N3→NHAc transformation (Scheme 11). The condensation of H-phosphonate 137 and acceptor 158 with a free hydroxyl group at C-6, followed by oxidation, resulted in the efficient formation of phosphodiester 159 (yield: 96%), which was then 6′-O-desilylated to create a new active site in acceptor 160. However, the attachment of the next monomer unit 137 to phosphodiester 160 was less effective and, after oxidation, formed the corresponding phosphodiester 161 with a 62% yield. With a view to synthesizing trimer 106 with a phosphoester substituent at C-6, acceptor 160 was reacted with phosphodiester 139 (Table 1, entry 4) and a dibenzylphosphate group at C-6 to obtain the trimeric precursor 162 with a 59% yield. A reduction in all azido groups, total N-acetylation, and deprotection in compounds 161 and 162 afforded the spacer-armed conjugation-ready antigens 105 and 106 [111].

Scheme 11.

Key building blocks for synthesis of spacer-armed antigens 105 and 106 related to MenA phosphoglycans [111]. Reagents and conditions: (a) 137 (1.3 eq.), PivCl (3.8 eq.), Py, r.t., 60 min; (b) I2 (1.2 eq.), Py:H2O 49:1, −40 °C → 0 °C, 30 min, 96% yield over 2 steps; (c) Et3N∙3HF (5 eq.), THF, 91% yield; (d) 137 (1.3 eq.), PivCl (2.5 eq.), r.t., 120 min. Py; (e) I2 (1.2 eq.), Py:H2O 49:1, −40 °C → −10 °C., 62% yield over 2 steps; (f) PivCl, Py.

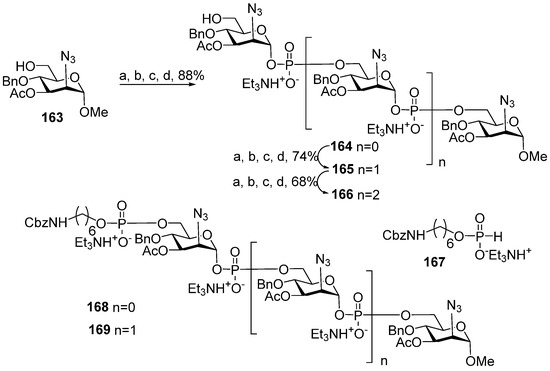

3-O-Acetylated dimer 107 and trimer 108 related to MenA capsular phosphoglycans were synthesized as methyl glycosides (Figure 7) [110]. The phosphitylation of acceptors 163, 164, and 165, which comprised one, two, or three 2-deoxy-2-azido mannose residues with H-phosphonate 145, followed by oxidation and detritylation, afforded phosphodiesters 164, 165, and 166 with 88%, 74%, and 68% yields, respectively. The alcohols obtained were subjected to phosphitylation with H-phosphonate 167 and subsequent oxidation (Scheme 12). The connection of H-phosphonate 167 to the 6-OH of the terminal monosaccharide was effective only for the shorter alcohols 164 and 165 (88% over two steps) and resulted in the preparation of protected di- and trimers 168 and 169 (Scheme 12). The transformation of azido groups into amino groups and the total N-acetylation and debenzylation of compounds 168 and 169 formed the spacer-armed dimer 107 and trimer 108, which carry acetyl groups at O-3 of each ManNAc residue, as they do in bacterial MenA phosphoglycans. In the homologous series 164–166, attempts to phosphitylate the longest alcohol 166 with H-phosphonate 145 in order to obtain a tetramer or with the pre-spacer H-phosphonate 167 were not successful, in contrast to compounds 164 and 165.

Scheme 12.

Key building blocks for synthesis of spacer-armed oligomers 107 and 108 [110] related to MenA capsular phosphoglycans. Reagents and conditions: (a) 145 (1.2 eq.), PivCl (1.8 eq.), Py, 20 °C, 30 min; (b) Et3N (4.8 eq.), −40 °C, Py:H2O 95:5; (c) −40 °C, I2 (2.4 eq.), 30 min; (d) 10 °C, 1% TFA in dichloromethane.

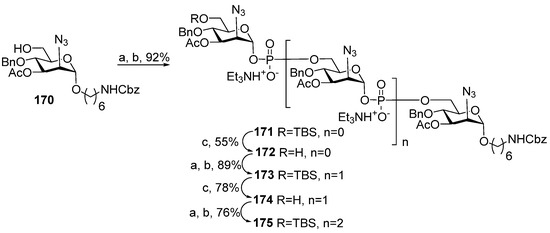

In general, the examples of the synthesis of oligomers related to MenA capsular phosphoglycans discussed above are in line with the tendency outlined in an earlier review [39], which discussed the decrease in the efficiency of phosphitylation with H-phosphonates with the increase in the number of already formed phosphodiester bonds and suggested the lability of phosphodiester fragments in the conditions of the H-phosphonate protocol. However, in 2017, a group of Indian researchers synthesized an aminohexyl glycoside of oligomer 109 related to capsular phosphoglycans, which contained four 3-O-acetylated ManNAc residues, using a linear, synthetic strategy (Scheme 13) [109]. In a sequence of phosphitylation steps, H-phosphonate 143 was used as a universal monomer (Table 1, entry 6). The establishment of the first phosphodiester linkage between alcohol 170 and H-phosphonate 143 afforded compound 171 (yield: 92%), which was, in turn, desilylated to form acceptor 172. The phosphitylation of alcohol 172 with H-phosphonate 143, followed by oxidation, resulted in the formation of compound 173 with two phosphodiester bridges (yield: 89%). The desilylation of compound 173 formed acceptor 174, which was phosphitylated with H-phosphonate 143 and, after oxidation, compound 175 with three phosphodiester bridges was obtained with a 76% yield.

Scheme 13.

Key building blocks for the synthesis of oligomer 109 structurally related to MenA phosphoglycans [109]. Reagents and conditions: (a) 143 (2 eq.), PivCl (3 eq.), Py, 20 °C, 90 min; (b) −40 °C, solution of I2 (5 eq.) in Py/H2O 20:1, 150 min, −40 °C → −10 °C, 30 min; (c) Et3N∙3HF (5 eq.), THF.

After the transformation of azido groups into NHAc groups and the desilylation, debenzylation, and deprotection of the spacer amino group, the spacer-armed ligand 109 was conjugated to TT. The antigenic properties of oligomer 109 were evaluated in a competitive ELISA experiment. Both oligomer 109 and its conjugate with TT in the concentration range 12.5–400 μg glycan/mL were found to neutralize anti-MenA rabbit antiserum and inhibit the binding of antibodies to the bacterial MenA phosphoglycan used as a coating antigen. In comparison to the conjugate, oligomer 109 showed lower inhibition [109]. It can be concluded that the improvement of synthetic protocols made it possible to obtain oligomeric antigens related to MenA capsular phosphoglycans, which contain up to four ManNAc residues. However, for the efficient application of antigens of this type in immunodiagnostic tests and vaccine production, the hydrolytic lability issue has to be addressed.

5. Synthesis of Glycomimetics of MenA Capsular Phosphoglycans

Today, all anti-MenA conjugate vaccines include a lyophilized bacterial MenA component except for the fully liquid commercial vaccine preparation Menactra®. The presence of the MenA antigen in the dissolved form substantially shortens the shelf life for Menactra® to 18 months at 2–8 °C compared to the 4-year shelf life of MenQuadfi® and the 3-year shelf life of Menjugate® and MenAfriVac® in these conditions. With a view to preparing hydrolytically stable MenA antigens, a number of oligomeric analogs were designed, in which NHAc groups were replaced with trichloroacetamide groups as they are not likely to undergo transformation into oxazolines. Another type of mimetics is compounds with the isosteric replacement of one of the hemiacetal oxygens with a methylene group (phosphono- and carba-analogs).

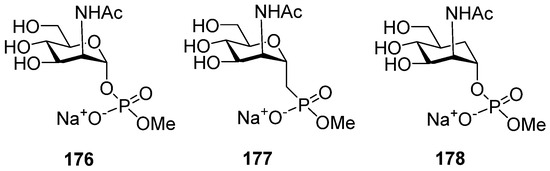

A comparative conformational analysis of a hexapyranose ring in 2-deoxy-2-acetamido mannohexapyranosyl phosphate 176 and its phosphono-analog 177 and carba-analog 178 (Figure 9) in a study of conformations in combination with NMR experiments showed that for compound 176, 4C1 was almost the only populated conformer, whereas for phosphonate 177, the proportion of pyranose ring conformers other than 4C1 was 4%, and for the carba-analog 178, this proportion rose to 7% [121]. The most populated 4C1 conformer for compound 178 was confirmed by quantum mechanics and molecular dynamics calculations [122]. The molecular dynamics calculations performed for a decamer of a MenA capsular phosphoglycan repeating unit and its carba-analog showed that, despite a number of conformational and dynamic variations, the carba-mimetics of the fragments of MenA capsular phosphoglycans can be considered candidate antigens for the construction of anti-MenA vaccine preparations [123].

Figure 9.

Sodium salt phosphodiesters of α-ManNAc (176) and its phosphono-analog (177) and carba-analog (178) as model compounds for comparative conformational analysis.

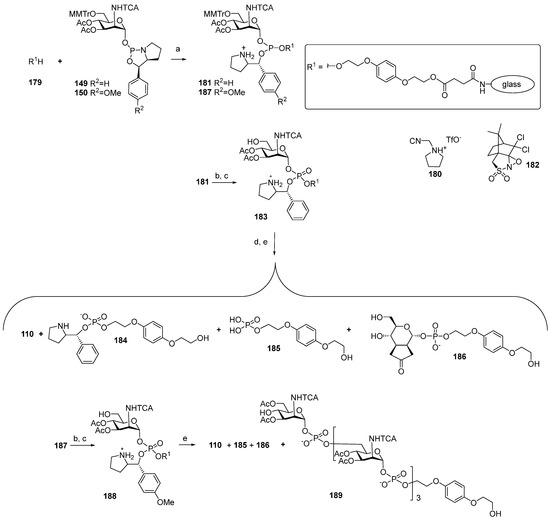

As mentioned previously, the axial NHAc group at C-2 of the ManNAc residue contributes largely to the lability of MenA capsular phosphoglycans and their fragments via neighboring group participation. One of the possible ways to circumvent this obstacle is the replacement [55] of the acetamide group at C-2 with the trichloroacetamide group, which is not likely to form oxazolines. To study the possibility of the preparation of the N-trichloroacetamide mimetics of ManNHAc, oxazaphospholidines 149 and 150 (Table 1) were obtained in a solid-phase synthesis. Bis(2-hydroxyethyl) hydroquinone 179 (Scheme 14) [108] was immobilized on a glass support and phosphitylated with phosphoramidites 149 and 150. The phosphitylation of hydroquinone 179 with phosphoramidite 149 in the presence of 1-(cyanomethyl) pyrrolidinium trifluoromethanesulfonate (compound 180) resulted in the formation of phosphite 181, which carried a 2-phenylpyrrolydine residue as a result of the cycle opening. Phosphotriester 181 was subjected to mild oxidation with DCSO (compound 182) and desilylated with TFA/TES to produce phosphotriester 183, with a free 6-OH group for the following elongation of the oligomeric chain. Finally, the cleavage of the 2-phenylpyrrolydine ether was fulfilled in the presence of a base, followed by deacetylation and removal of the solid support by the action of MeONa/MeOH.

Scheme 14.

Key building blocks for the solid-phase synthesis of a monomer of MenA capsular phosphoglycans, 110, in which the NHAc moiety has been substituted for trichloroacetamide [108]. Reagents and conditions: (a) 180, r.t., acetonitrile; (b) 182, acetonitrile; (c) 1% THF, CH2Cl2, TES, r.t., 1 min., 1 min.; (d) 2,6-lutidine, acetonitrile; (e) NaOMe/MeOH.

However, researchers faced considerable difficulties at the step of the cleavage of the 2-phenylpyrrolydine ether. After the support was removed, analysis of the products showed that the use of DBU for the cleavage of the ether did not provide target phosphodiester 110, and the identified products 184–186 did not contain a ManNAc residue. When the weaker bases of Et3N or 2,6-lutidine were used as basic catalysts, the target product 110 was obtained with a moderate yield (17%) and low conversion.

In order to replace the step of the basic hydrolysis of the O(P)-protective group for acidic hydrolysis, phosphoramidite 150 with a p-MeO-Ph residue in the place of the Ph residue, as in compound 149, was used. Phosphoramidite 150 was attached to a solid support, and phosphite 187 was oxidized with DCSO (compound 182) to yield phosphotriester 188, followed by the simultaneous acid hydrolysis of the trityl group and removal of the 2-(p-methoxybenzyl) pyrrolidine moiety. However, after deacetylation and removal of the solid support with 50 mM NaOMe/MeOH, the unwanted products 186 and 187 were detected. Without taking into account inefficient deprotection, this method provided the preparation of tetramer 189, which was O-acetylated and N-trichloroacetylated. The authors noted that the developed method in the current state is not suitable for the synthesis of oligomers [108].

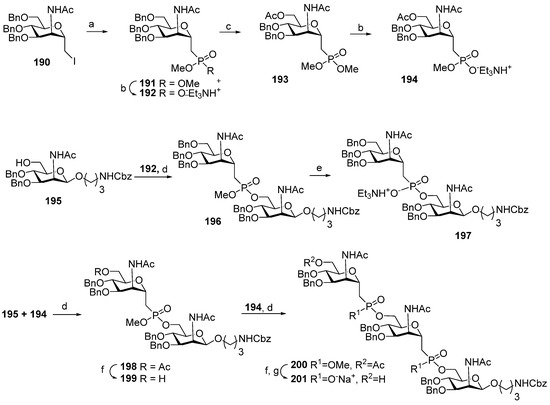

In 2005, the preparation of the first isosteric hydrolysis-resistant phosphono-analog 111 structurally related to MenA phosphoglycans was published by Lay et al. [115]. The interaction of iodide 190, in which the iodomethylene group is arranged axially, with trimethylphosphite (Scheme 15) afforded phosphonodiester 191, which was further converted to ester 192 by the action of triethylamine and thiophenol.

Scheme 15.

Key blocks for the synthesis of spacer-armed phosphono-analogs of MenA phosphoglycans, 111 and 112 (Figure 6) [113,115]. Reagents and conditions: (a) P(OMe)3, 100 °C, vacuum; (b) Et3N, PhSH, THF, r.t., 62%; (c) ZnCl2, Ac2O:AcOH 2:1, r.t., 16 h, 92%; (d) Ph3P, DIAD, THF, 0 °C, 24 h, yield 97% for 197, 90% for 198, 83% for 200; (e) Et3N, PhSH, toluene, 110 °C, 36 h, Amberlite IR120 (Na+) 95%; (f) NaOMe/MeOH; (g) DBU, PhSH, THF, r.t., 8 h, Amberlite IR120 (Na+), 95%.

Similarly, 6-O-acetylated phosphonodiester 193 was converted to the corresponding ester 194 by partial hydrolysis. Mitsunobu reaction conditions were used for the condensation of ester 192 with the selectively protected ManNAc 195, which formed phosphonodiester 196 (yield: 97%) [113]. Partial hydrolysis of phosphonodiester 196 into phosphonoester 197 was also efficient. 6′-O-Acetylated phosphonodiester 198 was synthesized by the condensation of 195 with phosphonoester 194, with a 90% yield. By deacetylation, phosphonodiester 198 was converted into alcohol 199 and condensed with phosphonoester 194 to form compound 200 with two phosphonodiester bridges and an 83% yield. Chemoselective hydrolysis of the methyl phosphonate moieties in compound 200 formed phosphonoester 201. Total deprotection of phosphonoester 197 with two ManNAc residues and 201 with three ManNAc residues resulted in phosphono-analogs 111 and 112 (Figure 6) [113].

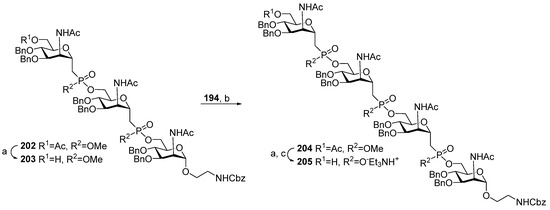

A similar strategy in combination with Mitsunobu reaction modification, where Ph3P is replaced with tris(4-chlorophenyl) phosphine, was used for the synthesis of the series of phosphono-analogs 113–115 of MenA phosphoglycans (Scheme 16) [114]. The 6″-O-deacetylation of phosphonodiester 202 resulted in alcohol 203, which was then reacted with universal monosaccharide block 194 in modified Mitsunobu conditions to obtain the phosphono-analog 204 of MenA phosphoglycans with three phosphonodiester-bridged fragments (yield: 87%). Partial hydrolysis of diester moieties afforded compound 205 (yield: 75%), and after total deprotection, phosphono-analog 115 was obtained with three pseudo-ManNAc residues.

Scheme 16.

Key blocks for the synthesis of phospho-analog 115 (Figure 6) related to MenA phosphoglycans [114]. Reagents and conditions: (a) 1 M KOH/MeOH, 84%; (b) (p-ClC6H4)3P, DIAD, THF, 0 °C, 30 min, 87%; (c) DBU, PhSH, acetonitrile, r.t., 75%.

The antigenic properties of ligands 111 and 112 [113] were studied in competitive ELISA experiments with anti-MenA human antisera. Native MenA phosphoglycans were used as a coating antigen and positive control, and MenY phosphoglycans were used as a negative control. For both ligands, the EC50 was about 10−3 mg/mL, which is three orders higher than the EC50 of 6.6 × 10−6 mg/mL for MenA phosphoglycans.

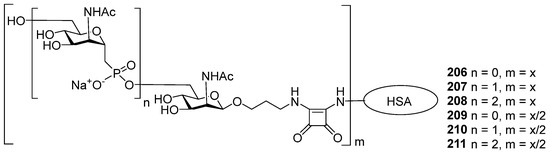

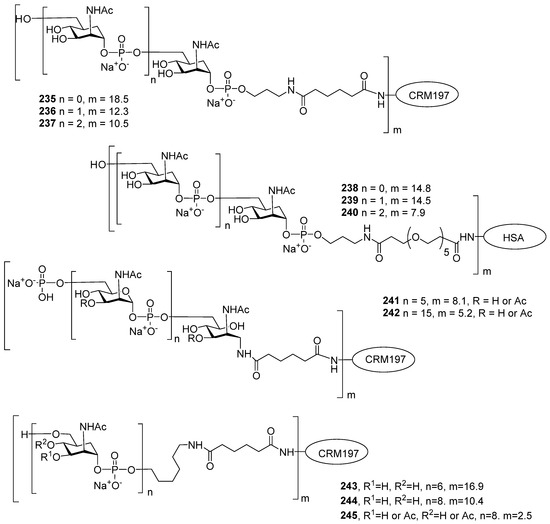

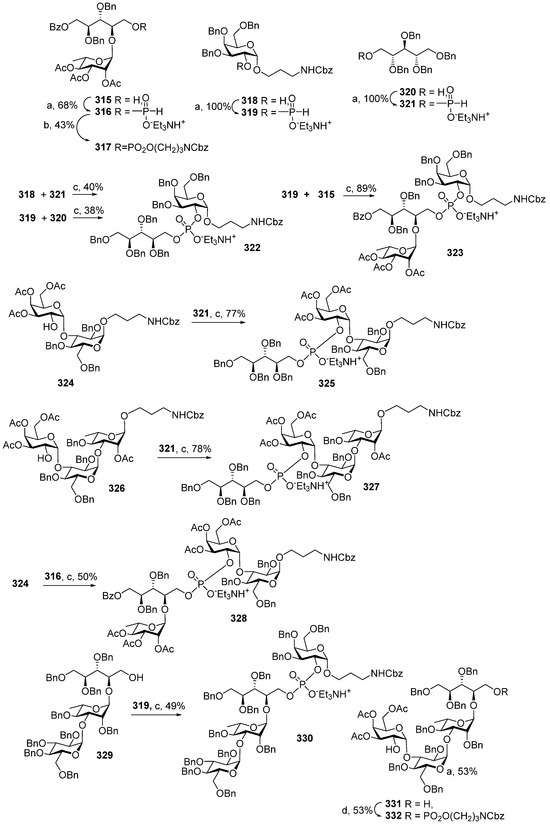

Aminopropyl glycosides 111 and 112 and 3-aminopropyl β-D-ManNAc were transformed into conjugates with HSA using the squarate procedure [124] (Figure 10). One series consisted of conjugates 206–208 (Figure 10) with the maximum saccharide/protein molar ratio, and another series of conjugates was composed of compounds 209–211 (Figure 10) with the saccharide/protein molar ratio being half of the value achieved for conjugates 206–208. Competitive ELISA experiments with the mouse polyclonal anti-MenA antisera and MenA capsular phosphoglycans as a coating antigen showed that at an inhibitor concentration of 1 mg/mL, inhibition using the fully loaded conjugate 206 was 55%. For conjugates 207 and 208, it reached 65%, whereas MenA capsular phosphoglycans provided 100% inhibition. Inhibition with the half-loaded conjugates 209–211 was 5–15% lower than for the fully loaded conjugates with the same antigen type [124]. Conjugates 206–211 were used for the immunization of mice at a dose of 2 μg/mouse and efficiently evoked IgG antibodies, which is a reliable marker of the induction of thymus-dependent immune responses. Quantitative elucidation of the level of anti-MenA IgG antibodies developed against conjugates 206–211 showed that immunization with the half-loaded conjugates 209–211 was more efficient compared to the fully loaded conjugates 206–208. It is important to note that the level of induced anti-MenA antibodies was similar for the half-loaded conjugates 209–211, regardless of the length of the pseudo-oligosaccharide antigen. The authors concluded that this result indicated the antibodies’ recognition of the ManNAc epitope [124].

Figure 10.

Conjugates of amino-spacered C-phosphono analogs of MenA capsular phosphoglycans [124].

In contrast to C-phosphono mimetics, in which the methylene group stands in the place of anomeric oxygen, in carba-analogs, the decrease in electrophilicity of the carbonyl carbon, along with the increase in the stability of the phosphodiester linkage, is achieved by the replacement of the ring hemiacetal oxygen of ManNAc with a methylene group [125].

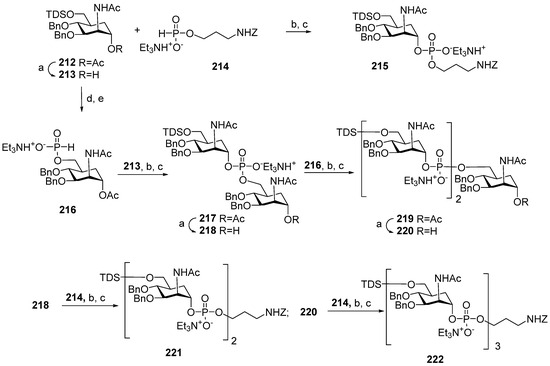

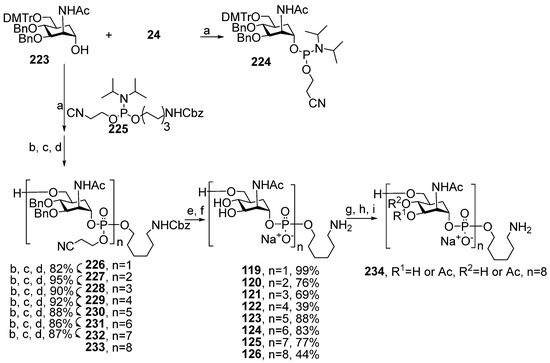

Synthesis of the series of carba-analogs 116–118 (Figure 7) of aminopropyl glycosides of a monomer, a dimer, and a trimer of MenA capsular phosphoglycans, and the advanced series of carba-analogs 119–126, from monomers to octamers, as aminohexyl glycosides, was performed by the Lay group [116,117,118]. Carba-analogs 116–118 [118] were obtained by the sequential elongation of a pseudo-oligosaccharide chain, starting from the spacer-equipped monomer (Scheme 17). For the preparation of monomer 116, the universal orthogonally protected precursor 212 was transformed into alcohol 213, which was phosphitylated with H-phosphonate 214 and oxidized to obtain the spacer-armed phosphodiester 215 with an 81% yield.

Scheme 17.

Key blocks for preparation of spacer-armed carba-analogs of oligomers 116–118 related to MenA CPS [118]. Reagents and conditions: (a) NaOMe/MeOH, r.t., 4 h, yield of compound 213—84%, 218—87%, 220—70%; (b) Py, PivCl, r.t., 45 min; (c) I2, Py -H2O 19:1, r.t., 15 min, yield for compound 215—81%, 217—82%, 219—81%, 221—85%, 222—57%; (d) Bu4NF, THF, r.t., 3 h; (e)–129, CH3CN-Py 3:1, r.t., 45 min, yield 82%.

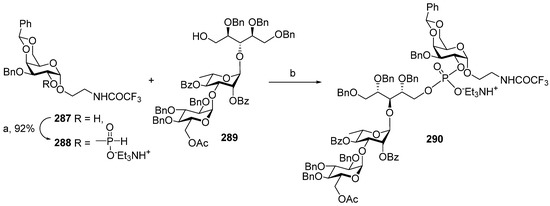

For the preparation of oligomers 117 and 118, the universal precursor 212 was desilylated and converted into H-phosphonate 216, which was used as a universal monomer block for chain elongation. The interaction of H-phosphonate 216 with alcohol 213 and the subsequent oxidation formed phosphodiester 217 (yield: 82%), which was deacetylated to obtain alcohol 218. The condensation of alcohol 218 with H-phosphonate 216 resulted in pseudo-trisaccharide 219 (yield: 81%), which was deacetylated to produce alcohol 220. Finally, pre-spacer 214 was introduced into alcohols 218 and 220 to obtain the spacer-armed, protected dimers 221 and 222 with yields of 85% and 57%, respectively. The high efficiency of the phosphitylation of alcohol 218, which already includes a phosphodiester bridge with H-phosphonates 214 and 216, evidences the increase in stability of the phosphodiester linkage in protected carba-analogs compared to phosphodiester-linked oligosaccharides. However, the phosphitylation of 220, which already comprised two phosphodiester moieties, was less efficient, indicating the limitations of the application of the H-phosphonate procedure to the linear synthesis of longer oligomers. The target carba-analogs 116–118 of monomers, dimers, and trimers related to MenA phosphoglycans were obtained after the total deprotection of compounds 215, 221, and 222 [118].