Navigating the COVID-19 Therapeutic Landscape: Unveiling Novel Perspectives on FDA-Approved Medications, Vaccination Targets, and Emerging Novel Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

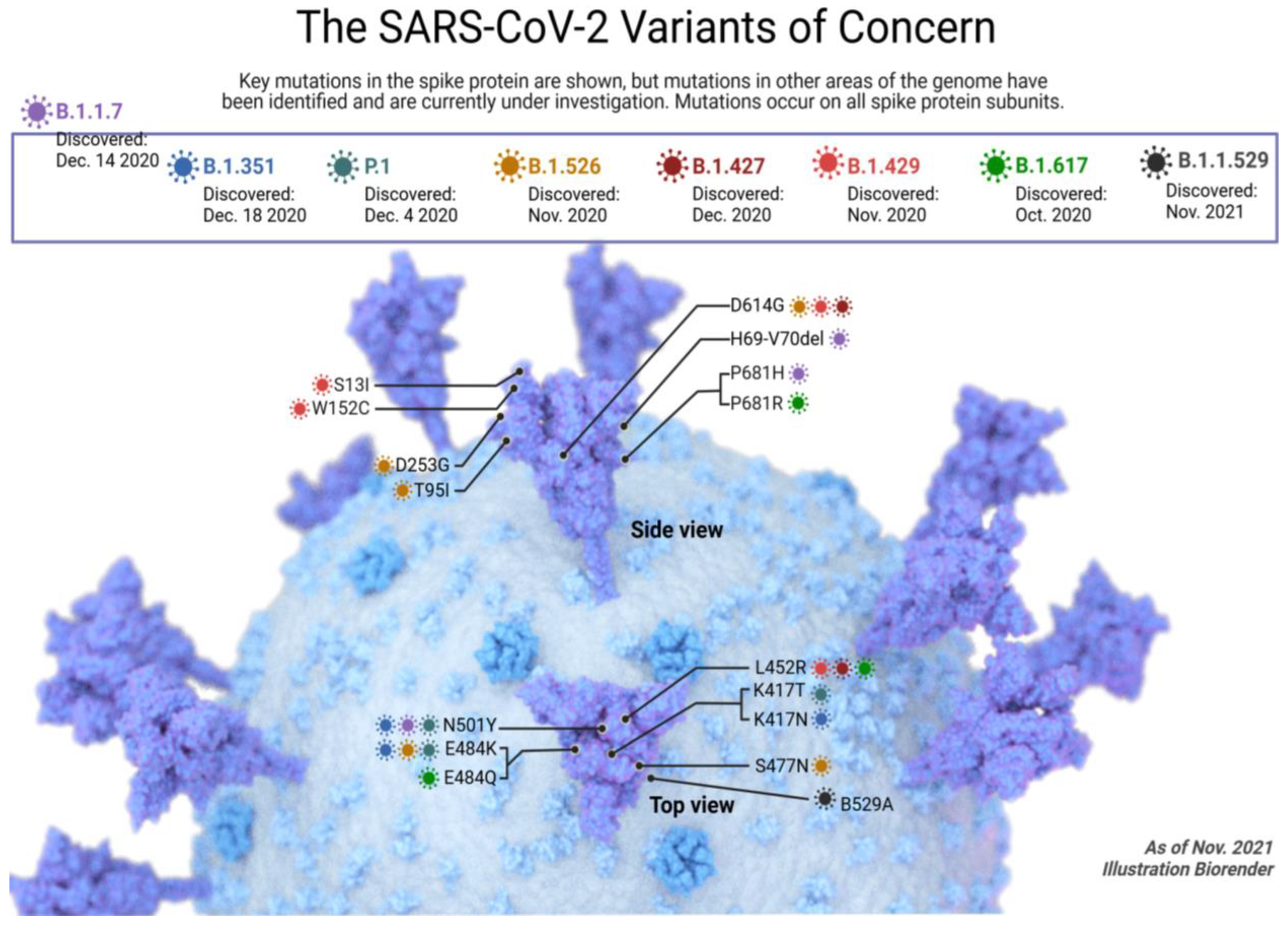

2. Vaccines Targets for SARS-CoV-2

2.1. Alpha SARS-CoV-2 Variant

2.2. Beta SARS-CoV-2 Variant

2.3. Gamma SARS-CoV-2 Variants

2.4. Delta SARS-CoV-2 Variant

2.5. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 Variant

3. Antiviral Drugs Against COVID-19

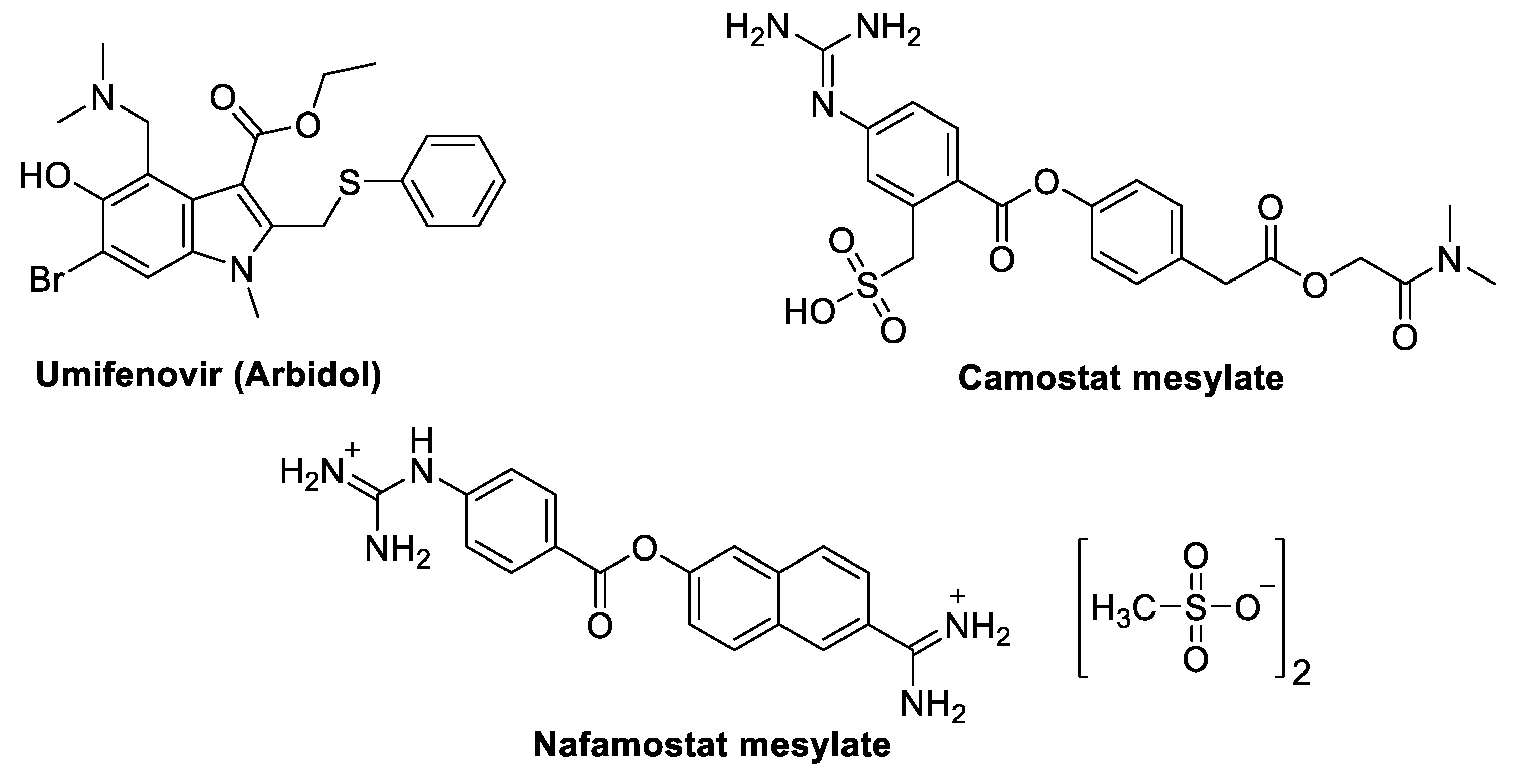

3.1. Fusion Inhibitors Targeting Spike Protein or Viral Entry Inhibition

3.1.1. Umifenovir (Arbidol)

3.1.2. Camostat Mesylate

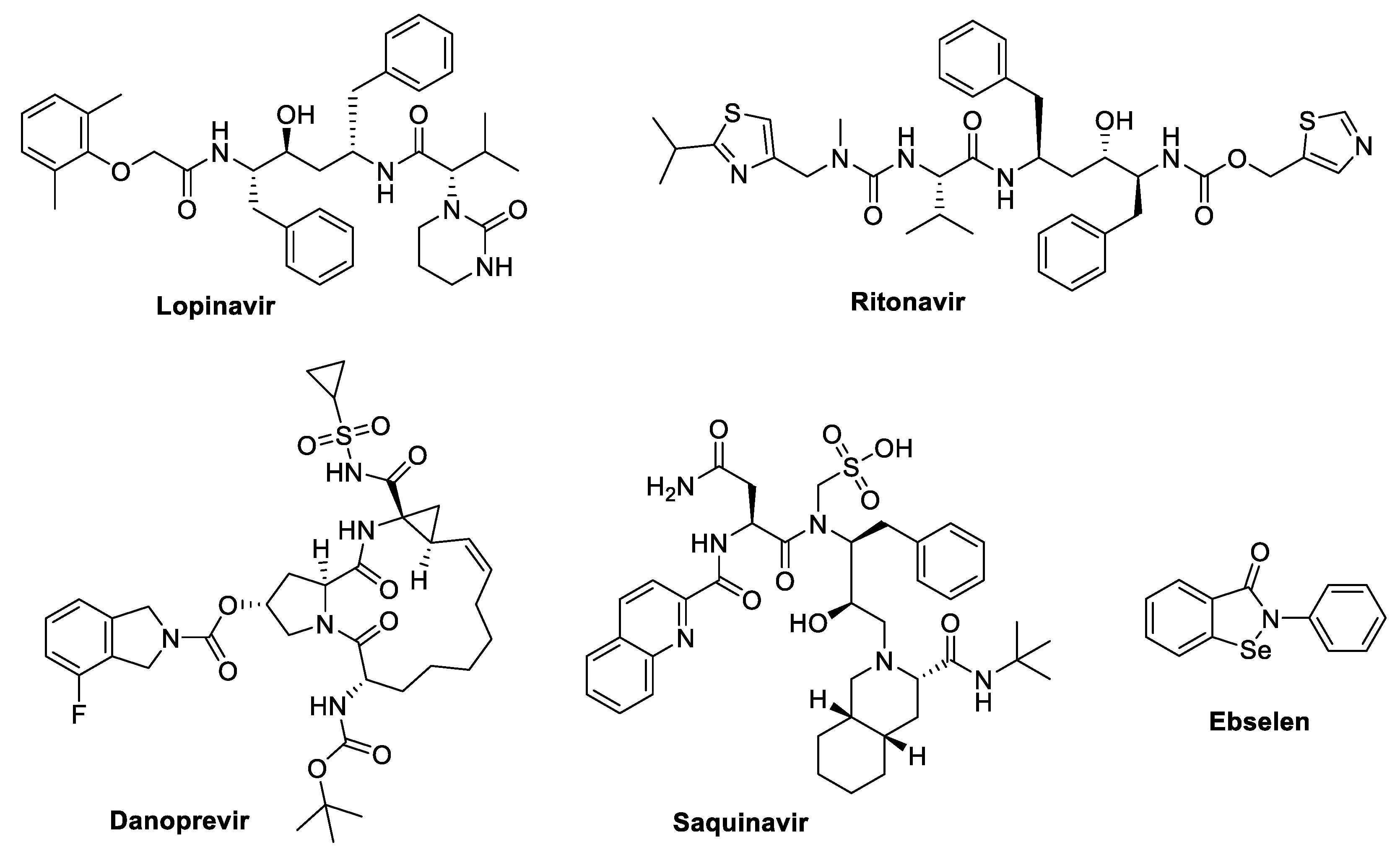

3.2. Protease Inhibitors

3.2.1. Lopinavir

3.2.2. Lopinavir/Ritonavir + Ribavirin

3.2.3. Danoprevir

3.2.4. Darunavir

3.2.5. Atazanavir

3.2.6. Saquinavir and Other Protease Inhibitors

3.2.7. Nelfinavir

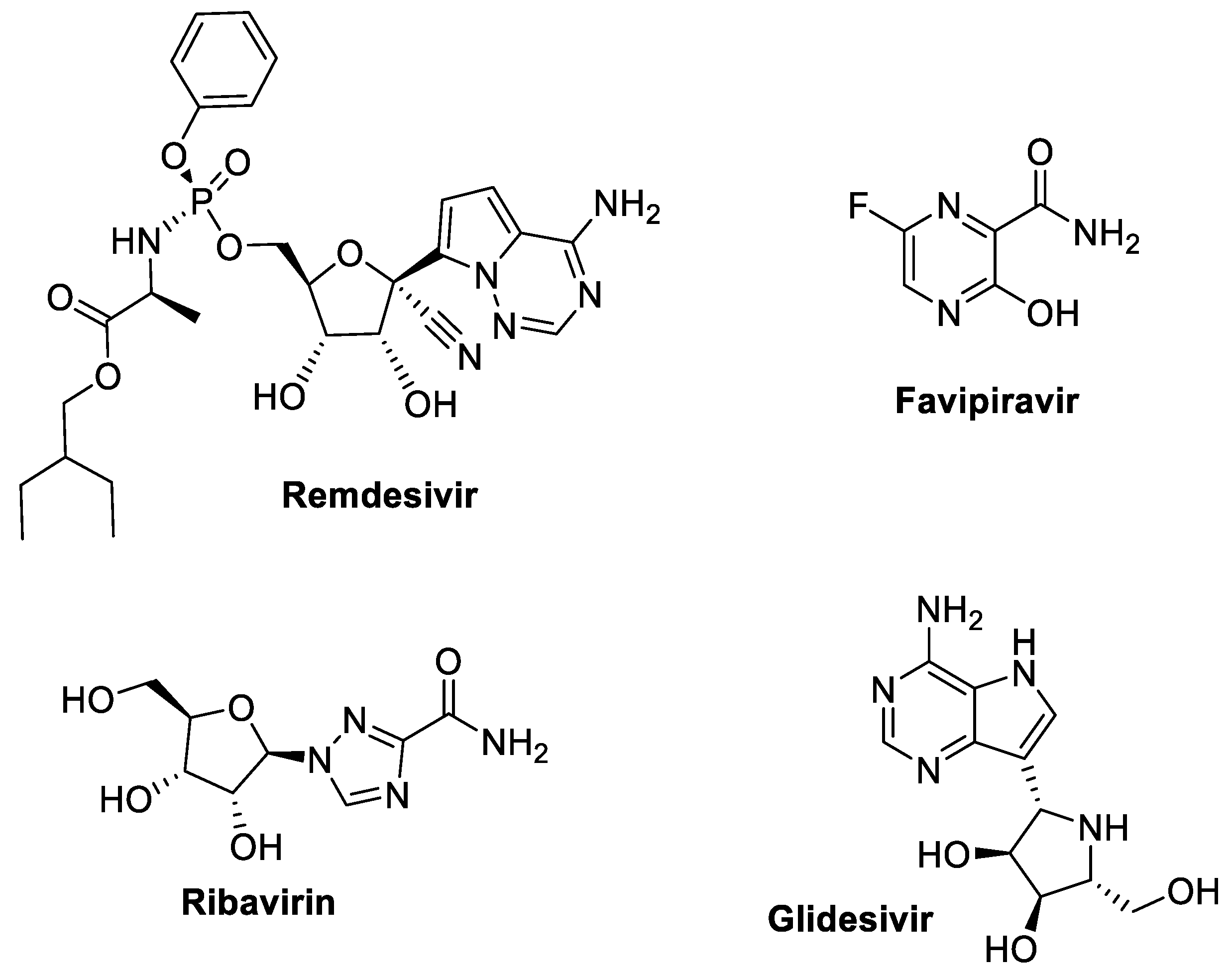

3.3. RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Target, Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

3.3.1. Remdesivir (GS-5734, Veklury) (Gilead Sciences)

3.3.2. Favipiravir

3.3.3. Ribavirin

4. Other Nucleoside/Nucleotide Analogs (Transcription Inhibitors)

5. Neuraminidase Inhibitors

5.1. Oseltamivir

5.2. Zanamivir and Peramivir

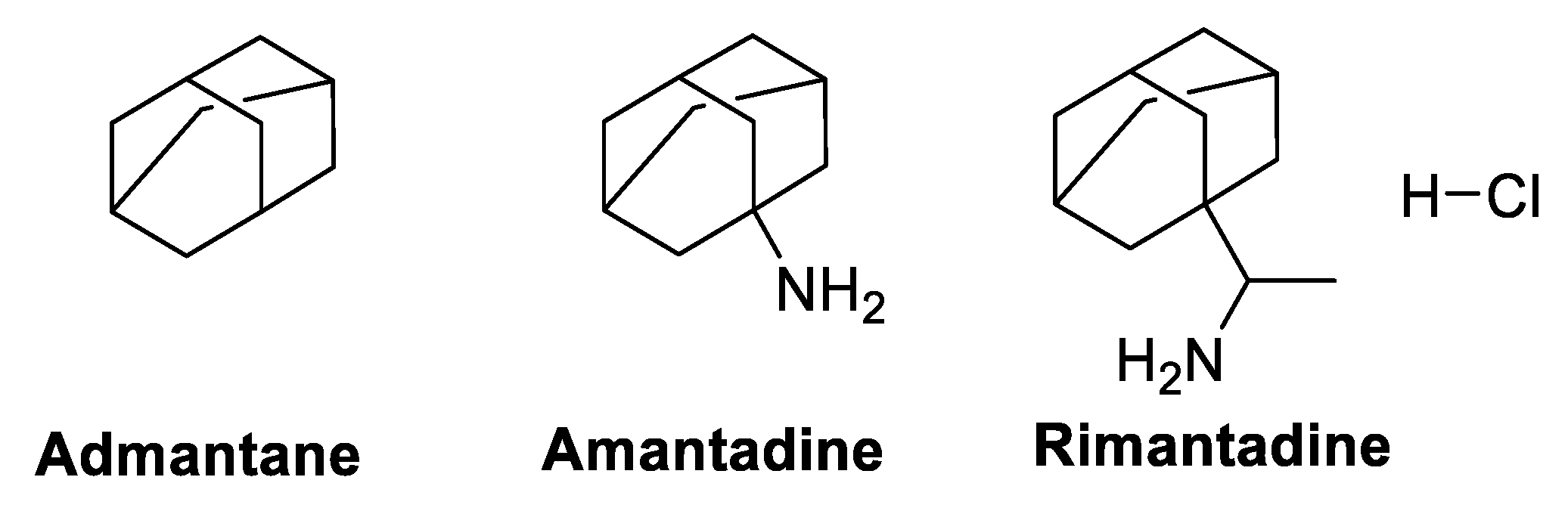

5.3. M2 Ion-Channel Protein Target

Adamantane, Amantadine, and Rimantadine

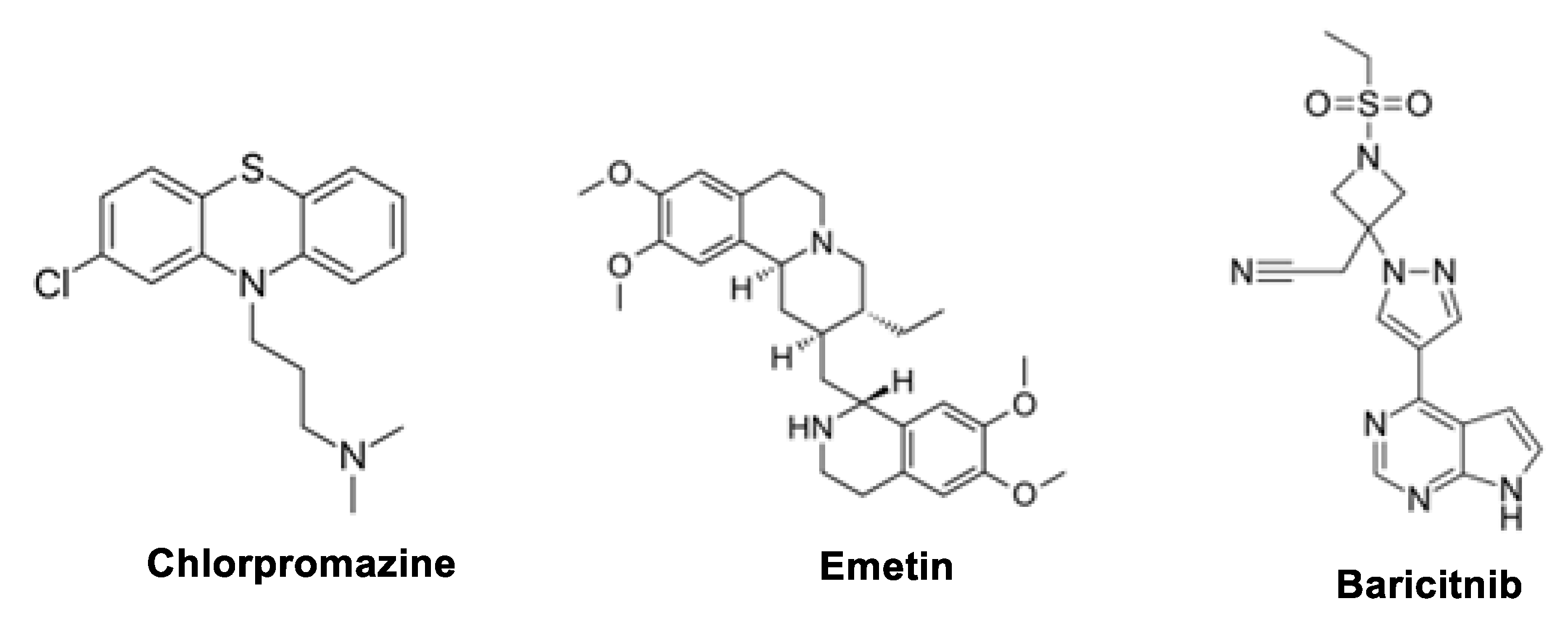

6. Non-Antiviral Drugs Against SARS-CoV-2

6.1. Baricitinib

6.2. Ivermectin; Importin α/β1-Mediated Nuclear Import Inhibitors

6.3. Interferon α and β

6.4. Teicoplanin

6.5. Emetine

6.6. Chlorpromazine

6.7. Aplidin

6.8. Rapamycin

6.9. Lianhuaqingwen Capsule

6.10. Convalescent Plasma

6.11. Metformin

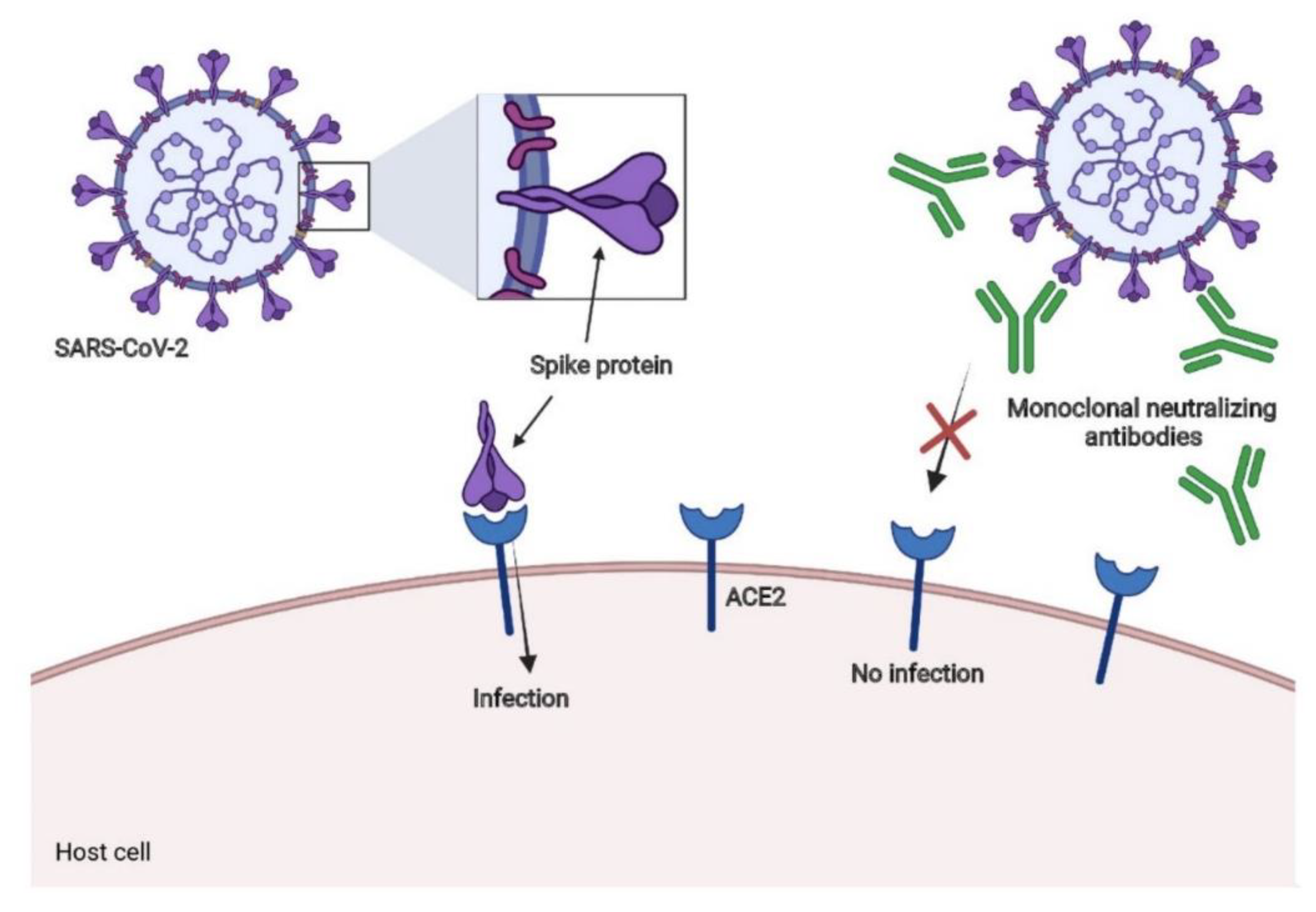

7. Neutralizing Antibodies for SARS-CoV-2

8. Some Recently Synthesized Compounds and Approved for COVID-19 Treatment

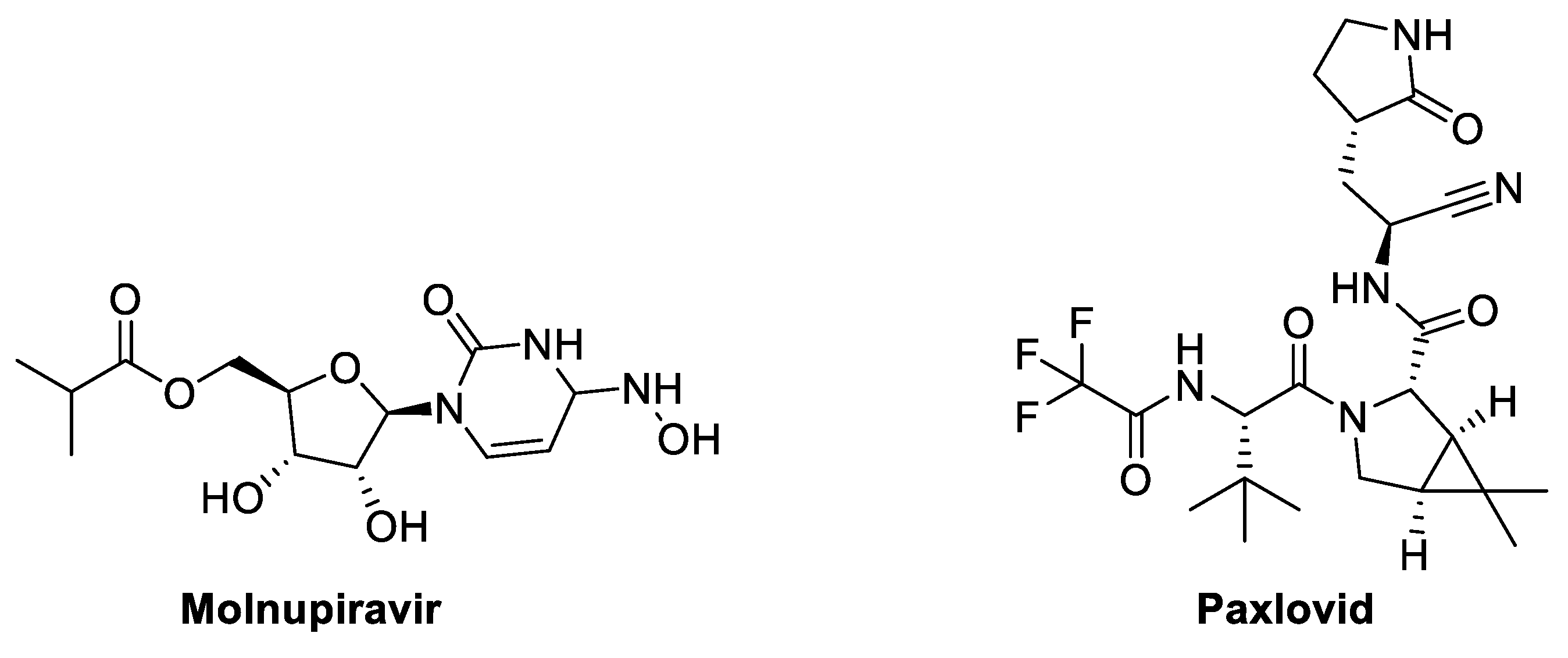

8.1. Molnupiravir (MK-4482, EIDD-2801) (Ridgeback Biotherapeutics/MSD)

8.2. Paxlovid (Pf-07321332)

9. COVID-19 and Cancer

10. Conclusions and Public Health Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weiss, S.R.; Leibowitz, J.L. Chapter 4—Coronavirus Pathogenesis. In Advances in Virus Research; Maramorosch, K., Shatkin, A.J., Murphy, F.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 81, pp. 85–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathy, S.; Dassarma, B.; Roy, S.; Chabalala, H.; Matsabisa, M.G. A review on possible modes of action of chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine: Repurposing against SAR-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufan, A.; GÜLER, A.A.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. COVID-19, immune system response, hyperinflammation and repurposing antirheumatic drugs. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.I.; Ryu, B.-H.; Chong, Y.P.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.C.; Hong, K.-W.; Bae, I.-G.; Cho, O.-H. Five severe COVID-19 pneumonia patients treated with triple combination therapy with lopinavir/ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, and interferon β-1b. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.K.; Bonnier, A.; Chong, W. Antimalarials as Antivirals for COVID-19: Believe it or Not! Am. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 360, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Masry, R.M.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Alnajjar, R.; Mahmoud, S.H.; Mostafa, A.; Kadry, H.H.; Abou-Seri, S.M.; Taher, A.T. Newly synthesized series of oxoindole–oxadiazole conjugates as potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents: In silico and in vitro studies. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 5078–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshdy, W.H.; Khalifa, M.K.; San, J.E.; Tegally, H.; Wilkinson, E.; Showky, S. SARS-CoV-2 Genetic diversity and lineage dynamics of in Egypt. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.S.; Amanlou, M. Anti-HCV and anti-malaria agent, potential candidates to repurpose for coronavirus infection: Virtual screening, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation study. Life Sci. 2020, 258, 118205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, M.; Al-Nazawi, M. Virtual screening and repurposing of FDA approved drugs against COVID-19 main protease. Life Sci. 2020, 251, 117627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.-J. Potential inhibitors against 2019-nCoV coronavirus M protease from clinically approved medicines. J. Genet. Genom. 2020, 47, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfiky, A.A. Anti-HCV, nucleotide inhibitors, repurposing against COVID-19. Life Sci. 2020, 248, 117477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Michelson, A.P.; Foraker, R.; Zhan, M.; Payne, P.R.O. Repurposing drugs for COVID-19 based on transcriptional response of host cells to SARS-CoV-2. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.01226. [Google Scholar]

- Samaee, H.; Mohsenzadegan, M.; Ala, S.; Maroufi, S.S.; Moradimajd, P. Tocilizumab for treatment patients with COVID-19: Recommended medication for novel disease. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 89 Pt A, 107018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kantar, S.; Nehmeh, B.; Saad, P.; Mitri, G.; Estephan, C.; Mroueh, M.; Akoury, E.; Taleb, R.I. Derivatization and combination therapy of current COVID-19 therapeutic agents: A review of mechanistic pathways, adverse effects, and binding sites. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1822–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretto, G.; Sala, S.; Caforio, A.L.P. Acute myocardial injury, MINOCA, or myocarditis? Improving characterization of coronavirus-associated myocardial involvement. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2124–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Wang, Y.; Molina, M.J. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14857–14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falahi, S.; Kenarkoohi, A. Transmission routes for SARS-CoV-2 infection: Review of evidence. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 38, 100778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquès, M.; Domingo, J.L. Contamination of inert surfaces by SARS-CoV-2: Persistence, stability and infectivity. A review. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farne, H.; Kumar, K.; Ritchie, A.I.; Finney, L.J.; Johnston, S.L.; Singanayagam, A. Repurposing Existing Drugs for the Treatment of COVID-19. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, D.B.; Bakr, M.M.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Moatasim, Y.; El Taweel, A.; Mostafa, A. Scrutinizing the Feasibility of Nonionic Surfactants to Form Isotropic Bicelles of Curcumin: A Potential Antiviral Candidate Against COVID-19. Aaps Pharmscitech 2022, 23, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CR, V.; Sharma, R.; Jayashree, M.; Nallasamy, K.; Bansal, A.; Angurana, S.K.; Mathew, J.L.; Sankhyan, N.; Dutta, S.; Verma, S.; et al. Epidemiology, Clinical Profile, Intensive Care Needs and Outcome in Children with SARS-CoV-2 Infection Admitted to a Tertiary Hospital During the First and Second Waves of the COVID-19 Pandemic in India. Indian J. Pediatr. 2022, 90, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.M.; Mahmoud, S.H.; Tarek, M.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Mahmoud, A.; Mostafa, A.; Elhefnawi, M.M.; Ali, M.A. In Silico and In Vivo Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 Predicted Epitopes-Based Candidate Vaccine. Molecules 2021, 26, 6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, W.T.; Carabelli, A.M.; Jackson, B.; Gupta, R.K.; Thomson, E.C.; Harrison, E.M.; Ludden, C.; Reeve, R.; Rambaut, A.; Consortium, C.-G.U.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.M.; Hong, W.Q.; Pan, X.Y.; Lu, G.W.; Wei, X.W. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Characteristics and prevention. MedComm 2021, 2, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, U.; Acharya, K.; Mondal, R.; Singh, A.; Saso, L.; Chakrabarti, S.S. Should ACE2 be given a chance in COVID-19 therapeutics: A semi-systematic review of strategies enhancing ACE2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 887, 173545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, V.; Angeli, A.; Nocentini, A.; Gratteri, P.; Pratesi, S.; Tanini, D. Leveraging SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) for COVID-19 Mitigation with Selenium-Based Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barghash, R.F.; Fawzy, I.M.; Chandrasekar, V.; Singh, A.V.; Katha, U.; Mandour, A.A. In Silico Modeling as a Perspective in Developing Potential Vaccine Candidates and Therapeutics for COVID-19. Coatings 2021, 11, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.M.; Hansen, K.; Del Rio, D.; Flores, D.; Barghash, R.F.; Kakkola, L.; Julkunen, I.; Awad, K. Insights into COVID-19: Perspectives on Drug Remedies and Host Cell Responses. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccines—COVID19 Vaccine Tracker. Available online: https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/vaccines/approved/ (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Fiolet, T.; Kherabi, Y.; MacDonald, C.-J.; Ghosn, J.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: A narrative review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Ye, B.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Tian, J.; Guo, Y.; Gao, G.F.; et al. Heterologous BBIBP-CorV/ZF2001 vaccination augments neutralization against SARS-CoV-2 variants: A preliminary observation. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 21, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enjuanes, L.; Zuñiga, S.; Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Gutierrez-Alvarez, J.; Canton, J.; Sola, I. Molecular Basis of Coronavirus Virulence and Vaccine Development. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 245–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinz, F.X.; Stiasny, K. Distinguishing features of current COVID-19 vaccines: Knowns and unknowns of antigen presentation and modes of action. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asthana, A.; Gaughan, C.; Dong, B.; Weiss, S.R.; Silverman, R.H. Specificity and Mechanism of Coronavirus, Rotavirus, and Mammalian Two-Histidine Phosphoesterases That Antagonize Antiviral Innate Immunity. mBio 2021, 12, e0178121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakidis, N.C.; López-Cortés, A.; González, E.V.; Grimaldos, A.B.; Prado, E.O. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines strategies: A comprehensive review of phase 3 candidates. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Riveron, J.T.; Aquino-Jarquin, G. Engineering of the current nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, N.; Barda, N.; Kepten, E.; Miron, O.; Perchik, S.; Katz, M.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Reis, B.; Balicer, R.D. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feikin, D.R.; Feikin, D.R.; Higdon, M.M.; Higdon, M.M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Andrews, N.; Andrews, N.; Araos, R.; Araos, R.; et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: Results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet 2022, 399, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, B.L.; Cheng, M.T.K.; Csiba, K.; Meng, B.; Gupta, R.K. SARS-CoV-2 and innate immunity: The good, the bad, and the “goldilocks”. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 21, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogando, N.S.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; van der Meer, Y.; Bredenbeek, P.J.; Posthuma, C.C.; Snijder, E.J. The Enzymatic Activity of the nsp14 Exoribonuclease Is Critical for Replication of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01246-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogando, N.S.; Ferron, F.; Decroly, E.; Canard, B.; Posthuma, C.C.; Snijder, E.J. The Curious Case of the Nidovirus Exoribonuclease: Its Role in RNA Synthesis and Replication Fidelity. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.J.R.; de Lima, S.C.; da Silva, R.C.; Kohl, A.; Pena, L. Viral Load in COVID-19 Patients: Implications for Prognosis and Vaccine Efficacy in the Context of Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 836826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, S.J.R.; Pena, L. Collapse of the public health system and the emergence of new variants during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. One Health 2021, 13, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Variants of SARS-CoV-2. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-%28covid-19%29-variants-of-sars-cov-2?gclid=Cj0KCQjwuLShBhC_ARIsAFod4fLdWjJ8BikZQ0qmz2DOJQKwubFkJlr5AhL_G2uztbEgVUxJyhXpJrwaAkS7EALw_wcB (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Plante, J.A.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Johnson, B.A.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Zhang, X.; Muruato, A.E.; Zou, J.; Fontes-Garfias, C.R.; et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature 2021, 592, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemo, M.K.M.; Islam, A. JN.1 as a new variant of COVID-19—editorial. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 1833–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, F.; Abadi, A.T.B. Implications of the Emergence of a New Variant of SARS-CoV-2, VUI-202012/01. Arch. Med. Res. 2021, 52, 569–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsumi, T.; Lusida, M.I.; Dinana, Z.; Wahyuni, R.M.; Yamani, L.N.; Juniastuti; Soetjipto; Matsui, C.; Deng, L.; Abe, T.; et al. Occurrence of norovirus infection in an asymptomatic population in Indonesia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 55, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.G.; Abbott, S.; Barnard, R.C.; Jarvis, C.I.; Kucharski, A.J.; Munday, J.D.; Pearson, C.A.B.; Russell, T.W.; Tully, D.C.; Washburne, A.D.; et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science 2021, 372, eabg3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.G.; Jarvis, C.I.; Edmunds, W.J. Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, T.; Pharris, A.; Spiteri, G.; Bundle, N.; Melidou, A.; Carr, M. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern B.1.1.7, B.1.351 or P.1: Data from seven EU/EEA countries, weeks 38/2020 to 10/2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, A.; Destras, G.; Gaymard, A.; Stefic, K.; Marlet, J.; Eymieux, S. Two-step strategy for the identification of SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/01 and other variants with spike deletion H69–V70, France, August to December 2020. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees-Spear, C.; Muir, L.; Griffith, S.A.; Heaney, J.; Aldon, Y.; Snitselaar, J.L.; Thomas, P.; Graham, C.; Seow, J.; Lee, N.; et al. The effect of spike mutations on SARS-CoV-2 neutralization. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Nair, M.S.; Liu, L.; Iketani, S.; Luo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Kwong, P.D.; et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature 2021, 593, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Chemaitelly, H.; Butt, A.A. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 Variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muik, A.; Wallisch, A.-K.; Sänger, B.; Swanson, K.A.; Mühl, J.; Chen, W.; Cai, H.; Maurus, D.; Sarkar, R.; Türeci, Ö.; et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 pseudovirus by BNT162b2 vaccine–elicited human sera. Science 2021, 371, 1152–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkal, G.N.; Yadav, P.D.; Ella, R.; Deshpande, G.R.; Sahay, R.R.; Gupta, N.; Vadrevu, K.M.; Abraham, P.; Panda, S.; Bhargava, B. Inactivated COVID-19 vaccine BBV152/COVAXIN effectively neutralizes recently emerged B.1.1.7 variant of SARS-CoV-2. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taab051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Duan, L.J.; Meng, Q.C.; Jiang, M.D.; Cao, J. Susceptibility of Circulating SARS-CoV-2 Variants to Neutralization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2354–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emary, K.R.W.; Golubchik, T.; Aley, P.K.; Ariani, C.V.; Angus, B.; Bibi, S.; Blane, B.; Bonsall, D.; Cicconi, P.; Charlton, S.; et al. Efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/01 (B.1.1.7): An exploratory analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegame, S.; Siddiquey, M.N.A.; Hung, C.-T.; Haas, G.; Brambilla, L.; Oguntuyo, K.Y.; Kowdle, S.; Chiu, H.-P.; Stevens, C.S.; Vilardo, A.E.; et al. Neutralizing activity of Sputnik V vaccine sera against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegally, H.; Wilkinson, E.; Giovanetti, M.; Iranzadeh, A.; Fonseca, V.; Giandhari, J.; Doolabh, D.; Pillay, S.; San, E.J.; Msomi, N.; et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 2021, 592, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi-Vaziri, M.; Fazlalipour, M.; Khorrami, S.M.S.; Azadmanesh, K.; Pouriayevali, M.H.; Jalali, T.; Shoja, Z.; Maleki, A. The ins and outs of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs). Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planas, D.; Bruel, T.; Grzelak, L.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Staropoli, I.; Porrot, F.; Planchais, C.; Buchrieser, J.; Rajah, M.M.; Bishop, E.; et al. Sensitivity of infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants to neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edara, V.V.; Norwood, C.; Floyd, K.; Lai, L.; Davis-Gardner, M.E.; Hudson, W.H. Infection- and vaccine-induced antibody binding and neutralization of the B.1.351 SARS-CoV-2 variant. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 516–521.e3. Available online: http://www.cell.com/article/S1931312821001372/fulltext (accessed on 5 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Beltran, W.F.; Lam, E.C.; St Denis, K.; Nitido, A.D.; Garcia, Z.H.; Hauser, B.M.; Feldman, J.; Pavlovic, M.N.; Gregory, D.J.; Poznansky, M.C.; et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell 2021, 184, 2372–2383.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, A.; Khalaila, Y.; Voloshin, O.; Keren-Naus, A.; Boehm-Cohen, L.; Raviv, Y.; Shemer-Avni, Y.; Rosenberg, E.; Taube, R. SARS-CoV-2 spike variants exhibit differential infectivity and neutralization resistance to convalescent or post-vaccination sera. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 522–528.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Dejnirattisai, W.; Supasa, P.; Liu, C.; Mentzer, A.J.; Ginn, H.M.; Zhao, Y.; Duyvesteyn, H.M.; Tuekprakhon, A.; Nutalai, R.; et al. Evidence of escape of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.351 from natural and vaccine-induced sera. Cell 2021, 184, 2348–2361.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhi, S.A.; Baillie, V.; Cutland, C.L.; Voysey, M.; Koen, A.L.; Fairlie, L.; Padayachee, S.D.; Dheda, K.; Barnabas, S.L.; Bhorat, Q.E.; et al. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 COVID-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1885–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturriza-Gomara, M.; O’brien, S.J. Foodborne viral infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 29, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, N.R.; Mellan, T.A.; Whittaker, C.; Claro, I.M.; Candido, D.D.S.; Mishra, S.; Crispim, M.A.E.; Sales, F.C.S.; Hawryluk, I.; McCrone, J.T.; et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 2021, 372, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveca, F.G.; Nascimento, V.; de Souza, V.C.; Corado, A.d.L.; Nascimento, F.; Silva, G.; Costa, Á.; Duarte, D.; Pessoa, K.; Mejía, M.; et al. COVID-19 in Amazonas, Brazil, was driven by the persistence of endemic lineages and P.1 emergence. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, C.M.; Felix, A.C.; de Paula, A.V.; de Jesus, J.G.; Andrade, P.S.; Cândido, D.; de Oliveira, F.M.; Ribeiro, A.C.; da Silva, F.C.; Inemami, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection caused by the P.1 lineage in Araraquara city, Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2021, 63, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levidiotou, S.; Gartzonika, C.; Papaventsis, D.; Christaki, C.; Priavali, E.; Zotos, N.; Kapsali, E.; Vrioni, G. Viral agents of acute gastroenteritis in hospitalized children in Greece. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 596–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, E.C.; Buss, L.F.; Carvalho, M.P.S.; Prete, C.A., Jr.; Crispim, M.A.E.; Fraiji, N.A.; Pereira, R.H.M.; Parag, K.V.; da Silva Peixoto, P.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; et al. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. Lancet 2021, 397, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.E.; Zhang, X.; Case, J.B.; Winkler, E.S.; Liu, Y.; VanBlargan, L.A.; Liu, J.; Errico, J.M.; Xie, X.; Suryadevara, N.; et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Casner, R.G.; Nair, M.S.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Cerutti, G.; Liu, L.; Kwong, P.D.; Huang, Y.; Shapiro, L.; et al. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variant P.1 to antibody neutralization. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 747–751.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejnirattisai, W.; Zhou, D.; Supasa, P.; Liu, C.; Mentzer, A.J.; Ginn, H.M.; Zhao, Y.; Duyvesteyn, H.M.; Tuekprakhon, A.; Nutalai, R.; et al. Antibody evasion by the P.1 strain of SARS-CoV-2. Cell 2021, 184, 2939–2954.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, M.; Margiotti, K.; Viola, A.; Mesoraca, A.; Giorlandino, C. Mild Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 P.1 (B.1.1.28) Infection in a Fully Vaccinated 83-Year-Old Man. Pathogens 2021, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Fawaz, M.A.M.; Aisha, A. A comparative overview of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants of concern. Le Infez. Med. 2022, 30, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.; Archer, B.; Laurenson-Schafer, H.; Jinnai, Y.; Konings, F.; Batra, N.; Pavlin, B.; Vandemaele, K.; Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Jombart, T.; et al. Increased transmissibility and global spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as at June 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, S.W.X.; Chiew, C.J.; Ang, L.W.; Mak, T.M.; Cui, L.; Toh, M.P.H.S.; Lim, Y.D.; Lee, P.H.; Lee, T.H.; Chia, P.Y.; et al. Clinical and Virological Features of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Variants of Concern: A Retrospective Cohort Study Comparing B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e1128–e1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.H.; Llewelyn, A.; Brandao, R.; Chowdhary, K.; Hardisty, K.-M.; Loddo, M. SARS-CoV-2 testing and sequencing for international arrivals reveals significant cross border transmission of high risk variants into the United Kingdom. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Wintersdorff, C.; Dingemans, J.; Lv, A.; Wolffs, P.; Bvd, V.; Hoebe, C.; Savelkoul, P. Infections caused by the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2 are associated with increased viral loads compared to infections with the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7) or non-Variants of Concern. Eur. PMC, 2021; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.; McMenamin, J.; Taylor, B.; Robertson, C. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: Demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet 2021, 397, 2461–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ginn, H.M.; Dejnirattisai, W.; Supasa, P.; Wang, B.; Tuekprakhon, A.; Nutalai, R.; Zhou, D.; Mentzer, A.J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Reduced neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617 by vaccine and convalescent serum. Cell 2021, 184, 4220–4236.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xia, H.; Zou, J.; Weaver, S.C.; Swanson, K.A.; Cai, H.; Cutler, M.; Cooper, D.; Muik, A.; et al. BNT162b2-elicited neutralization of B.1.617 and other SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nature 2021, 596, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.C.; Wu, M.; Harvey, R.; Kelly, G.; Warchal, S.; Sawyer, C.; Daniels, R.; Hobson, P.; Hatipoglu, E.; Ngai, Y.; et al. Neutralising antibody activity against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs B.1.617.2 and B.1.351 by BNT162b2 vaccination. Lancet 2021, 397, 2331–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, Y.; Zuckerman, N.; Nemet, I.; Atari, N.; Kliker, L.; Regev-Yochay, G.; Sapir, E.; Mor, O.; Alroy-Preis, S.; Mendelson, E.; et al. Neutralising capacity against Delta (B.1.617.2) and other variants of concern following Comirnaty (BNT162b2, BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccination in health care workers, Israel. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, P.Y.; Ong, S.W.X.; Chiew, C.J.; Ang, L.W.; Chavatte, J.-M.; Mak, T.-M.; Cui, L.; Kalimuddin, S.; Ni Chia, W.; Tan, C.W.; et al. Virological and serological kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant vaccine breakthrough infections: A multicentre cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 612.e1–612.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, M.; Jalkanen, P.; Lundberg, R.; Reinholm, A.; Laine, L.; Väisänen, E.; Skön, M.; Tähtinen, P.A.; Ivaska, L.; Pakkanen, S.H.; et al. Comparative analysis of COVID-19 vaccine responses and third booster dose-induced neutralizing antibodies against Delta and Omicron variants. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosi, E.; Bassignana, G.; Barrat, A.; Lina, B.; Vanhems, P.; Bielicki, J.; Colizza, V. Minimising school disruption under high incidence conditions due to the Omicron variant in France, Switzerland, Italy, in January 2022. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28, 2200192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. An overview of the safety, clinical application and antiviral research of the COVID-19 therapeutics. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, R.U.; Wilson, I.A. Structural basis of influenza virus fusion inhibition by the antiviral drug Arbidol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, G.; Sohail, M.; Bilal, M.; Rasool, N.; Qamar, M.U.; Ciurea, C.; Marceanu, L.G.; Misarca, C. N-Heterocycles as Promising Antiviral Agents: A Comprehensive Overview. Molecules 2024, 29, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Parkar, J.; Ansari, A.; Vora, A.; Talwar, D.; Tiwaskar, M.; Patil, S.; Barkate, H. Role of Favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Xu, T.; Chen, C.; Yang, G.; Zha, T.; Lu, J.; Xue, Y. Arbidol monotherapy is superior to lopinavir/ritonavir in treating COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e21–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, S.; Einav, S. Old Drugs for a New Virus: Repurposed Approaches for Combating COVID-19. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 2304–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderlinden, E.; Vrancken, B.; Van Houdt, J.; Rajwanshi, V.K.; Gillemot, S.; Andrei, G.; Lemey, P.; Naesens, L. Distinct Effects of T-705 (Favipiravir) and Ribavirin on Influenza Virus Replication and Viral RNA Synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6679–6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.V.; Kayal, A.; Malik, A.; Maharjan, R.S.; Dietrich, P.; Thissen, A.; Siewert, K.; Curato, C.; Pande, K.; Prahlad, D.; et al. Interfacial Water in the SARS Spike Protein: Investigating the Interaction with Human ACE2 Receptor and In Vitro Uptake in A549 Cells. Langmuir 2022, 38, 7976–7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, Y. Camostat mesilate therapy for COVID-19. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 15, 1577–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Noor, S.; Tippairote, T.; Dadar, M.; Menzel, A.; Bjørklund, G. Individual risk management strategy and potential therapeutic options for the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 215, 108409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawase, M.; Shirato, K.; van der Hoek, L.; Taguchi, F.; Matsuyama, S. Simultaneous Treatment of Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells with Serine and Cysteine Protease Inhibitors Prevents Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Entry. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 6537–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frediansyah, A.; Tiwari, R.; Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Harapan, H. Antivirals for COVID-19: A critical review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?adgroupsurvey=%7Badgroupsurvey%7D&gclid=CjwKCAjwrdmhBhBBEiwA4Hx5g9O5Y7R6aPcyQ1vf3hDXZbPngqCgh4fqTeZQUld0SFNjMATRWOIK7xoC-boQAvD_BwE (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Liu, F.; Xu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xuan, W.; Yan, T.; Pan, K.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J. Patients of COVID-19 may benefit from sustained Lopinavir-combined regimen and the increase of Eosinophil may predict the outcome of COVID-19 progression. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 95, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.M.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Hung, I.F.N.; Wong, M.M.L.; Chan, K.H.; Chan, K.S.; Kao, R.Y.T.; Poon, L.L.M.; Wong, C.L.P.; Guan, Y.; et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax 2004, 59, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, G.; Ruan, L.; Song, B.; Cai, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. A Trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, M.; Saunik, S. COVID-19 treatment by repurposing drugs until the vaccine is in sight. Drug Dev. Res. 2020, 81, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bege, M.; Borbás, A. The Design, Synthesis and Mechanism of Action of Paxlovid, a Protease Inhibitor Drug Combination for the Treatment of COVID-19. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Leist, S.R.; Schäfer, A.; Won, J.; Brown, A.J.; Montgomery, S.A.; Hogg, A.; Babusis, D.; Clarke, M.O.; et al. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, R.T.; Roth, J.S.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Simeonov, A.; Shen, M.; Patnaik, S.; Hall, M.D. Remdesivir: A Review of Its Discovery and Development Leading to Emergency Use Authorization for Treatment of COVID-19. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiwert, S.D.; Andrews, S.W.; Jiang, Y.; Serebryany, V.; Tan, H.; Kossen, K.; Rajagopalan, P.T.R.; Misialek, S.; Stevens, S.K.; Stoycheva, A.; et al. Preclinical Characteristics of the Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4A Protease Inhibitor ITMN-191 (R7227). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 4432–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, O.; Mohammadi, E.; Lam, S.; Turkez, H.; Boren, J.; Nielsen, J.; Uhlen, M.; Mardinoglu, A. Current Status of COVID-19 Therapies and Drug Repositioning Applications. iScience 2020, 23, 101303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Shang, J.; Ma, Y.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of 12-week Interferon-based Danoprevir Regimen in Patients with Genotype 1 Chronic Hepatitis C. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2019, 7, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Feng, B.; Guan, Y.; Zheng, S.; Sheng, J.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Y.; Kang, Y.; Wen, X.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of All-oral, 12-week Ravidasvir Plus Ritonavir-boosted Danoprevir and Ribavirin in Treatment-naïve Noncirrhotic HCV Genotype 1 Patients: Results from a Phase 2/3 Clinical Trial in China. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2019, 7, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicastri, E.; Petrosillo, N.; Ascoli Bartoli, T.; Lepore, L.; Mondi, A.; Palmieri, F.; D’Offizi, G.; Marchioni, L.; Murachelli, S.; Ippolito, G.; et al. National Institute for the Infectious Diseases “L. Spallanzani” IRCCS. Recommendations for COVID-19 Clinical Management. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2020, 12, 8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Lima, C.R.; da Silva, F.S.; Ferreira, A.C.; Mattos, M.; de Freitas, C.S.; Soares, V.C.; Dias, S.d.S.G.; Temerozo, J.R.; et al. Atazanavir, Alone or in Combination with Ritonavir, Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Replication and Proinflammatory Cytokine Production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020; 64, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T.L.; Joy, T.; Hadigan, C.M.; Liebau, J.G.; Makimura, H.; Chen, C.Y.; Thomas, B.J.; Weise, S.B.; Robbins, G.K.; Grinspoon, S.K. Effects of switching from lopinavir/ritonavir to atazanavir/ritonavir on muscle glucose uptake and visceral fat in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2009, 23, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, E.C.; Yang, K.S.; Drelich, A.K.; Kratch, K.C.; Cho, C.-C.; Kempaiah, K.R.; Hsu, J.C.; Mellott, D.M.; Xu, S.; Tseng, C.-T.K.; et al. Bepridil is potent against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2012201118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.C.; Ji, H.-F. A search for medications to treat COVID-19 via in silico molecular docking models of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and 3CL protease. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 35, 101646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Matsuyama, S.; Hoshino, T.; Yamamoto, N. Nelfinavir inhibits replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in vitro. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Qamar, M.T.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Alamri, M.A.; Chen, L.-L. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and anti-COVID-19 drug discovery from medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020, 10, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.J.; Jha, R.K.; Amera, G.M.; Jain, M.; Singh, E.; Pathak, A.; Singh, R.P.; Muthukumaran, J.; Singh, A.K. Targeting SARS-CoV-2: A systematic drug repurposing approach to identify promising inhibitors against 3C-like proteinase and 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 2679–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.T.; Pandey, I.; Zamboni, P.; Gemmati, D.; Kanase, A.; Singh, A.V.; Singh, M.P. Traditional Herbal Remedies with a Multifunctional Therapeutic Approach as an Implication in COVID-19 Associated Co-Infections. Coatings 2020, 10, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockman, L.J.; Bellamy, R.; Garner, P. SARS: Systematic Review of Treatment Effects. PLOS Med. 2006, 3, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns-Naas, L.A.; Zorbas, M.; Jessen, B.; Evering, W.; Stevens, G.; Ivett, J.L.; Ryan, T.E.; Cook, J.C.; Capen, C.C.; Chen, M.; et al. Increase in thyroid follicular cell tumors in nelfinavir-treated rats observed in a 2-year carcinogenicity study is consistent with a rat-specific mechanism of thyroid neoplasia. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2005, 24, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliq, Y.; Gallicano, K.; Tisdale, C.; Carignan, G.; Cooper, C.; McCarthy, A. Pharmacokinetic interaction between mefloquine and ritonavir in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 51, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapé, M.; Barnosky, S. Nelfinavir in Expanded Postexposure Prophylaxis Causing Acute Hepatitis with Cholestatic Features TWo Case Reports. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2001, 22, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.A. Compounds with Therapeutic Potential against Novel Respiratory 2019 Coronavirus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00399-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfiky, A.A. Ribavirin, Remdesivir, Sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and Tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): A molecular docking study. Life Sci. 2020, 253, 117592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, E.S.; Levy, J.K. Current knowledge about the antivirals remdesivir (GS-5734) and GS-441524 as therapeutic options for coronaviruses. One Health 2020, 9, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.-C.; Deng, Q.-X.; Dai, S.-X. Remdesivir for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 causing COVID-19: An evaluation of the evidence. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 35, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzotti, D.; Sguilla, M.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Astolfi, A.; Barreca, M.L. Small Molecule Drugs Targeting Viral Polymerases. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.A. Efficacy of repurposed antiviral drugs: Lessons from COVID-19. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 1954–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, M.L.; Andres, E.L.; Sims, A.C.; Graham, R.L.; Sheahan, T.P.; Lu, X.; Smith, E.C.; Case, J.B.; Feng, J.Y.; Jordan, R.; et al. Coronavirus Susceptibility to the Antiviral Remdesivir (GS-5734) Is Mediated by the Viral Polymerase and the Proofreading Exoribonuclease. mBio 2018, 9, e00221-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Product Alert N°4/2021: Falsified Remdesivir. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-08-2021-medical-product-alert-n-4-2021-falsified-remdesivir (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Cho, A.; Saunders, O.L.; Butler, T.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Vela, J.E.; Feng, J.Y.; Ray, A.S.; Kim, C.U. Synthesis and antiviral activity of a series of 1′-substituted 4-aza-7,9-dideazaadenosine C-nucleosides. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2705–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Graham, R.L.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Case, J.B.; Leist, S.R.; Pyrc, K.; Feng, J.Y.; Trantcheva, I.; et al. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinone, V.; Pace, L.; Fasanella, A.; Manzulli, V.; Parisi, A.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Ostuni, A.; Chironna, M.; Caprioli, E.; Labonia, M.; et al. VOC 202012/01 Variant Is Effectively Neutralized by Antibodies Produced by Patients Infected before Its Diffusion in Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holshue, M.L.; DeBolt, C.; Lindquist, S.; Lofy, K.H.; Wiesman, J.; Bruce, H.; Spitters, C.; Ericson, K.; Wilkerson, S.; Tural, A.; et al. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinner, C.D.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Criner, G.J.; López, J.R.A.; Cattelan, A.M.; Viladomiu, A.S.; Ogbuagu, O.; Malhotra, P.; Mullane, K.M.; Castagna, A.; et al. Effect of Remdesivir vs Standard Care on Clinical Status at 11 Days in Patients with Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrie, J.D. Remdesivir for COVID-19: Challenges of underpowered studies. Lancet 2020, 395, 1525–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, J.J.; Suárez, I.; Priesner, V.; Fätkenheuer, G.; Rybniker, J. Remdesivir against COVID-19 and Other Viral Diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020; 34, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvetkov, N.T.; Peeva, M.I.; Georgieva, M.G.; Deneva, V.; Balacheva, A.A.; Bogdanov, I.P.; Ponticelli, M.; Milella, L.; Kirilov, K.; Matin, M.; et al. Favipiravir vs. Deferiprone: Tautomeric, photophysical, in vitro biological studies, and binding interactions with SARS-Cov-2-MPro/ACE2. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2024, 7, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, Y.; Gowen, B.B.; Takahashi, K.; Shiraki, K.; Smee, D.F.; Barnard, D.L. Favipiravir (T-705), a novel viral RNA polymerase inhibitor. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Smith, L.K.; Rajwanshi, V.K.; Kim, B.; Deval, J. The Ambiguous Base-Pairing and High Substrate Efficiency of T-705 (Favipiravir) Ribofuranosyl 5′-Triphosphate towards Influenza A Virus Polymerase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, U.; Raju, R.; Udwadia, Z.F. Favipiravir: A new and emerging antiviral option in COVID-19. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2020, 76, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, S.-S.; Lee, P.-I.; Hsueh, P.-R. Treatment options for COVID-19: The reality and challenges. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.M. Clinical Features and Short-term Outcomes of 144 Patients with SARS in the Greater Toronto Area. JAMA 2003, 289, 2801–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.J.Y.; Wu, A.; Joynt, G.M.; Yuen, K.Y.; Lee, N.; Chan, P.K.S.; Cockram, C.S.; Ahuja, A.T.; Yu, L.M.; Wong, V.W.; et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: Report of treatment and outcome after a major outbreak. Thorax 2004, 59, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Nikam, A.N.; Shreya, A.B.; Mutalik, S.P.; Gopalan, D.; Kulkarni, S.; Padya, B.S.; Fernandes, G.; Mutalik, S.; Prassl, R. Potential therapeutic targets for combating SARS-CoV-2: Drug repurposing, clinical trials and recent advancements. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.-L.; Chen, C.-P.; Lin, Y.-C.; Liu, C.-E.; Liao, C.-H.; Cheng, S.-H. Lopinavir/ritonavir did not shorten the duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding in patients with mild pneumonia in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakou, G.; Barakat, M.; Israel, R.J.; Bacci, M.R. Virazole Collaborator Group for COVID-19 Respiratory Distress Ribavirin aerosol in hospitalized adults with respiratory distress and COVID-19: An open-label trial. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 16, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, R.; García-Albéniz, X.; Terán, C.; Morales, M.; Rial-Crestelo, D.; Garcinuño, M.A.; del Toro, M.G.; Hita, C.; Gómez-Sirvent, J.L.; Buzón, L.; et al. Daily tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine and hydroxychloroquine for pre-exposure prophylaxis of COVID-19: A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial in healthcare workers. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novel Coronavirus Information Center. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-center (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Welliver, R.; Monto, A.S.; Carewicz, O.; Schatteman, E.; Hassman, M.; Hedrick, J.; Jackson, H.C.; Huson, L.; Ward, P.; Oxford, J.S. Effectiveness of Oseltamivir in Preventing Influenza in Household ContactsA Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2001, 285, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, B.; Valizadeh, S.; Ghaffari, H.; Vahedi, A.; Karbalaei, M.; Eslami, M. A global treatments for coronaviruses including COVID-19. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 9133–9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; De Clercq, E. Therapeutic Options for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, S.D.C.; Beales, L.P.; Clarke, D.S.; Worsfold, O.; Evans, S.D.; Jaeger, J.; Harris, M.P.G.; Rowlands, D.J. The p7 protein of hepatitis C virus forms an ion channel that is blocked by the antiviral drug, Amantadine. FEBS Lett. 2003, 535, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Maheswari, U.; Parthasarathy, K.; Ng, L.; Liu, D.X.; Gong, X. Conductance and amantadine binding of a pore formed by a lysine-flanked transmembrane domain of SARS coronavirus envelope protein. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieszek, S.P.; Przychodzen, B.P.; Polymeropoulos, M.H. Amantadine disrupts lysosomal gene expression: A hypothesis for COVID19 treatment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.; Moss, C.; George, G.; Santaolalla, A.; Cope, A.; Papa, S.; Van Hemelrijck, M. Associations between immune-suppressive and stimulating drugs and novel COVID-19—A systematic review of current evidence. ecancermedicalscience 2020, 14, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, A.; Ferrara, F. Perspectives of association Baricitinib/Remdesivir for adults with COVID-19 infection. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 49, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, V.; Singh, A.V.; Maharjan, R.S.; Dakua, S.P.; Balakrishnan, S.; Dash, S.; Laux, P.; Luch, A.; Singh, S.; Pradhan, M. Perspectives on the Technological Aspects and Biomedical Applications of Virus-like Particles/Nanoparticles in Reproductive Biology: Insights on the Medicinal and Toxicological Outlook. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2022, 2, 2200010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, W.; Zhang, J.; Qi, Z. Baricitinib, a drug with potential effect to prevent SARS-CoV-2 from entering target cells and control cytokine storm induced by COVID-19. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 86, 106749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagstaff, K.M.; Sivakumaran, H.; Heaton, S.M.; Harrich, D.; Jans, D.A. Ivermectin is a specific inhibitor of importin α/β-mediated nuclear import able to inhibit replication of HIV-1 and dengue virus. Biochem. J. 2012, 443, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caly, L.; Wagstaff, K.M.; Jans, D.A. Nuclear trafficking of proteins from RNA viruses: Potential target for antivirals? Antivir. Res. 2012, 95, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.N.Y.; Atkinson, S.C.; Wang, C.; Lee, A.; Bogoyevitch, M.A.; Borg, N.A.; Jans, D.A. The broad spectrum antiviral ivermectin targets the host nuclear transport importin α/β1 heterodimer. Antivir. Res. 2020, 177, 104760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, A.; Le, N.T.-T.; Selisko, B.; Eydoux, C.; Alvarez, K.; Guillemot, J.-C.; Decroly, E.; Peersen, O.; Ferron, F.; Canard, B. Remdesivir and SARS-CoV-2: Structural requirements at both nsp12 RdRp and nsp14 Exonuclease active-sites. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-F.; Chien, C.-S.; Yarmishyn, A.A.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Luo, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-T.; Lai, W.-Y.; Yang, D.-M.; Chou, S.-J.; Yang, Y.-P.; et al. A Review of SARS-CoV-2 and the Ongoing Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.J.; Haider, M.A.; Ahmed, M.U.; Sundas, F.; Hirani, A.; Khan, I.A.; Anis, K.; Karim, A.H. Treatment Options for COVID-19: A Review. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, F.; Subissi, L.; De Morais, A.T.S.; Le, N.T.T.; Sevajol, M.; Gluais, L.; Decroly, E.; Vonrhein, C.; Bricogne, G.; Canard, B.; et al. Structural and molecular basis of mismatch correction and ribavirin excision from coronavirus RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E162–E171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrì, A.; Fabbrocini, G. Hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin: A synergistic combination for COVID-19 chemoprophylaxis and treatment? J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momekov, G.; Momekova, D. Ivermectin as a potential COVID-19 treatment from the pharmacokinetic point of view: Antiviral levels are not likely attainable with known dosing regimens. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2020, 34, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Iwasaki, A. Type I and Type III Interferons—Induction, Signaling, Evasion, and Application to Combat COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuplein, V.A.; Seifried, J.; Malczyk, A.H.; Miller, L.; Höcker, L.; Vergara-Alert, J.; Dolnik, O.; Zielecki, F.; Becker, B.; Spreitzer, I.; et al. High Secretion of Interferons by Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells upon Recognition of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 3859–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazear, H.M.; Schoggins, J.W.; Diamond, M.S. Shared and Distinct Functions of Type I and Type III Interferons. Immunity 2019, 50, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Hill, T.E.; Yoshikawa, N.; Popov, V.L.; Galindo, C.L.; Garner, H.R.; Peters, C.J.; Tseng, C.-T. Dynamic Innate Immune Responses of Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Associated Coronavirus Infection. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzé, G.; Tavernier, J. High efficiency targeting of IFN-α activity: Possible applications in fighting tumours and infections. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015, 26, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raad, I.; Darouiche, R.; Vazquez, J.; Lentnek, A.; Hachem, R.; Hanna, H.; Goldstein, B.; Henkel, T.; Seltzer, E. Efficacy and Safety of Weekly Dalbavancin Therapy for Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection Caused by Gram-Positive Pathogens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouya, M.A.; Afshani, S.M.; Maghsoudi, A.S.; Hassani, S.; Mirnia, K. Classification of the present pharmaceutical agents based on the possible effective mechanism on the COVID-19 infection. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 28, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.I.; Krpina, K.; Ianevski, A.; Shtaida, N.; Jo, E.; Yang, J.; Koit, S.; Tenson, T.; Hukkanen, V.; Anthonsen, M.W.; et al. Novel Antiviral Activities of Obatoclax, Emetine, Niclosamide, Brequinar, and Homoharringtonine. Viruses 2019, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaze, M.; Attali, D.; Prot, M.; Petit, A.-C.; Blatzer, M.; Vinckier, F.; Levillayer, L.; Chiaravalli, J.; Perin-Dureau, F.; Cachia, A.; et al. Inhibition of the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in human cells by the FDA-approved drug chlorpromazine. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 57, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdżal, S.; Rosik, J.; Lechowicz, K.; Machaj, F.; Kotfis, K.; Ghavami, S.; Łos, M.J. FDA approved drugs with pharmacotherapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) therapy. Drug Resist. Updat. 2020, 53, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancey, J. mTOR signaling and drug development in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patocka, J.; Kuca, K.; Oleksak, P.; Nepovimova, E.; Valis, M.; Novotny, M.; Klimova, B. Rapamycin: Drug Repurposing in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Hou, Y.; Shen, J.; Huang, Y.; Martin, W.; Cheng, F. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, A.; Byrareddy, S.N. Rapamycin as a potential repurpose drug candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 331, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, A.; Harun, N.; Dilling, D.F.; Merchant, K.; McMahan, S.; Ingledue, R.; French, A.; Corral, J.A.; Korbee, L.; Kopras, E.J.; et al. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Respir. Investig. 2024, 62, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Guan, Y.M. Efficacy and safety of Lianhua Qingwen as an adjuvant treatment for influenza in Chinese patients: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2024, 103, e36986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runfeng, L.; Yunlong, H.; Jicheng, H.; Weiqi, P.; Qinhai, M.; Yongxia, S.; Chufang, L.; Jin, Z.; Zhenhua, J.; Haiming, J.; et al. Lianhuaqingwen exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory activity against novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 156, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Guan, W.-J.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Q.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Duan, Z.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Lianhuaqingwen capsules, a repurposed Chinese herb, in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial. Phytomedicine 2020, 85, 153242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Zhi, K.; Mukherji, A.; Gerth, K. Repurposing Antiviral Protease Inhibitors Using Extracellular Vesicles for Potential Therapy of COVID-19. Viruses 2020, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, F.; Li, D.; Yang, M.; Xing, L.; et al. Treatment of 5 Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 with Convalescent Plasma. JAMA 2020, 323, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiong, J.; Bao, L.; Shi, Y. Convalescent plasma as a potential therapy for COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, K.; Kakkola, L.; Julkunen, I. High Glucose Increases Lactate and Induces the Transforming Growth Factor Beta-Smad 1/5 Atherogenic Pathway in Primary Human Macrophages. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Jiao, B.; Qu, L.; Yang, D.; Liu, R. The development of COVID-19 treatment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1125246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.E.; Brown-Augsburger, P.L.; Corbett, K.S.; Westendorf, K.; Davies, J.; Cujec, T.P. The neutralizing antibody, LY-CoV555, protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Núñez, J.J.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Torres-Hernández, P.C.; Hernández-Bello, J. Overview of Neutralizing Antibodies and Their Potential in COVID-19. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougan, M.; Nirula, A.; Azizad, M.; Mocherla, B.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Chen, P.; Hebert, C.; Perry, R.; Boscia, J.; Heller, B.; et al. Bamlanivimab plus Etesevimab in Mild or Moderate COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Phoon, Y.P.; Karlinsey, K.; Tian, Y.F.; Thapaliya, S.; Thongkum, A.; Qu, L.; Matz, A.J.; Cameron, M.; Cameron, C.; et al. A high OXPHOS CD8 T cell subset is predictive of immunotherapy resistance in melanoma patients. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 219, e20202084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanBlargan, L.A.; Errico, J.M.; Halfmann, P.J.; Zost, S.J.; Crowe, J.E.; Purcell, L.A.; Kawaoka, Y.; Corti, D.; Fremont, D.H.; Diamond, M.S. An infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron virus escapes neutralization by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, M.N.Y.; Kua, K.P.; Lee, S.W.H.; Wong, K.K. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody bebtelovimab—A systematic scoping review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qu, L.; Matz, A.J.; Murphy, P.A.; Liu, Y.; Manichaikul, A.W.; Aguiar, D.; Rich, S.S.; Herrington, D.M.; Vu, D.; et al. AtheroSpectrum Reveals Novel Macrophage Foam Cell Gene Signatures Associated with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Circulation 2022, 145, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iketani, S.; Iketani, S.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Chan, J.F.-W.; et al. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 2022, 604, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toots, M.; Yoon, J.-J.; Cox, R.M.; Hart, M.; Sticher, Z.M.; Makhsous, N.; Plesker, R.; Barrena, A.H.; Reddy, P.G.; Mitchell, D.G.; et al. Characterization of orally efficacious influenza drug with high resistance barrier in ferrets and human airway epithelia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaax5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenke, K.; Hansen, F.; Schwarz, B.; Feldmann, F.; Haddock, E.; Rosenke, R.; Barbian, K.; Meade-White, K.; Okumura, A.; Leventhal, S.; et al. Orally delivered MK-4482 inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication in the Syrian hamster model. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Zhou, S.; Graham, R.L.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Agostini, M.L.; Leist, S.R.; Schäfer, A.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd; Stevens, L.J.; et al. An orally bioavailable broad-spectrum antiviral inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial cell cultures and multiple coronaviruses in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eabb5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Schinazi, R.F.; Götte, M. Molnupiravir promotes SARS-CoV-2 mutagenesis via the RNA template. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Fang, W.; Yuan, L.; Wang, X. An update on inhibitors targeting RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for COVID-19 treatment: Promises and challenges. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 205, 115279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, L. Current understanding of nucleoside analogs inhibiting the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 4385–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabinger, F.; Stiller, C.; Schmitzová, J.; Dienemann, C.; Kokic, G.; Hillen, H.S.; Höbartner, C.; Cramer, P. Mechanism of molnupiravir-induced SARS-CoV-2 mutagenesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, A.; Gralinski, L.E.; Johnson, C.E.; Yao, W.; Kovarova, M.; Dinnon, K.H.; Liu, H.; Madden, V.J.; Krzystek, H.M.; De, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection is effectively treated and prevented by EIDD-2801. Nature 2021, 591, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, W.P.; Holman, W.; Bush, J.A.; Almazedi, F.; Malik, H.; Eraut, N.C.J.E.; Morin, M.J.; Szewczyk, L.J.; Painter, G.R. Human Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Molnupiravir, a Novel Broad-Spectrum Oral Antiviral Agent with Activity against SARS-CoV-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021; 65, e02428-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. Molnupiravir: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, A.; Singh, R.; Misra, A. Molnupiravir in COVID-19: A systematic review of literature. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussi, S.S.; Hammond, J.L.; Gerstenberger, B.S.; Anderson, A.S. Therapeutics for COVID-19. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Cadenas, E.; Graf, P.; Sies, H. A novel biologically active seleno-organic compound—I. Glutathione peroxidase-like activity in vitro and antioxidant capacity of PZ 51 (Ebselen). Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984, 33, 3235–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Ma, Q.; Kuzmič, P.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Jiang, H.; et al. Preclinical evaluation of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor RAY1216 shows improved pharmacokinetics compared with nirmatrelvir. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimuro, M. The Interactions between Cells and Viruses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiama-Roig, A.; Pérez-Martínez, L.; Ledo, P.R.; Verdugo-Sivianes, E.M.; Blanco, J.-R. Should We Expect an Increase in the Number of Cancer Cases in People with Long COVID? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprinca, G.C.; Mohor, C.-I.; Bereanu, A.-S.; Oprinca-Muja, L.-A.; Bogdan-Duică, I.; Fleacă, S.R.; Hașegan, A.; Diter, A.; Boeraș, I.; Cristian, A.N.; et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Genome and Viral Nucleocapsid in Various Organs and Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.C.L.; Goh, D.; Lim, X.; Tien, T.Z.; Lim, J.C.T.; Lee, J.N.; Tan, B.; Tay, Z.E.A.; Wan, W.Y.; Chen, E.X.; et al. Residual SARS-CoV-2 viral antigens detected in GI and hepatic tissues from five recovered patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 71, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Hirata, H.; Tokuhira, N.; Motooka, D.; Nakamura, S.; Ueda, A.; Tachino, J.; Koide, M.; Uchiyama, A.; Ogura, H.; et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in patients with severe COVID-19. Acute Med. Surg. 2024, 11, e923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanduc, D. From Anti-Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Immune Response to Cancer Onset via Molecular Mimicry and Cross-Reactivity. Glob. Med. Genet. 2021, 08, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, A.E.G.; Silva, G.R.; Gimba, E.R.P.; Matos, A.d.R. Susceptibility of lung cancer patients to COVID-19: A review of the pandemic data from multiple nationalities. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 2637–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesulu, B.P.; Chandrasekar, V.T.; Girdhar, P.; Advani, P.; Sharma, A.; Elumalai, T.; Hsieh, C.E.; Elghazawy, H.I.; Verma, V.; Krishnan, S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cancer patients affected by a novel coronavirus. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peravali, M.; Joshi, I.; Ahn, J.; Kim, C. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes in Patients with Lung Cancer with Coronavirus Disease 2019. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-Y.; Nam, J.-S. The force awakens: Metastatic dormant cancer cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkan, D.; El Touny, L.H.; Michalowski, A.M.; Smith, J.A.; Chu, I.; Davis, A.S.; Webster, J.D.; Hoover, S.; Simpson, R.M.; Gauldie, J.; et al. Metastatic Growth from Dormant Cells Induced by a Col-I–Enriched Fibrotic Environment. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 5706–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfo, C.; Meshulami, N.; Russo, A.; Krammer, F.; García-Sastre, A.; Mack, P.C.; Gomez, J.E.; Bhardwaj, N.; Benyounes, A.; Sirera, R.; et al. Lung Cancer and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection: Identifying Important Knowledge Gaps for Investigation. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Rizvi, H.; Preeshagul, I.; Egger, J.; Hoyos, D.; Bandlamudi, C.; McCarthy, C.; Falcon, C.; Schoenfeld, A.; Arbour, K.; et al. COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, V.R.; Patel, B.M. The Deadly Duo of COVID-19 and Cancer! Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 643004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barghash, R.F.; Gemmati, D.; Awad, A.M.; Elbakry, M.M.M.; Tisato, V.; Awad, K.; Singh, A.V. Navigating the COVID-19 Therapeutic Landscape: Unveiling Novel Perspectives on FDA-Approved Medications, Vaccination Targets, and Emerging Novel Strategies. Molecules 2024, 29, 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29235564

Barghash RF, Gemmati D, Awad AM, Elbakry MMM, Tisato V, Awad K, Singh AV. Navigating the COVID-19 Therapeutic Landscape: Unveiling Novel Perspectives on FDA-Approved Medications, Vaccination Targets, and Emerging Novel Strategies. Molecules. 2024; 29(23):5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29235564

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarghash, Reham F., Donato Gemmati, Ahmed M. Awad, Mustafa M. M. Elbakry, Veronica Tisato, Kareem Awad, and Ajay Vikram Singh. 2024. "Navigating the COVID-19 Therapeutic Landscape: Unveiling Novel Perspectives on FDA-Approved Medications, Vaccination Targets, and Emerging Novel Strategies" Molecules 29, no. 23: 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29235564

APA StyleBarghash, R. F., Gemmati, D., Awad, A. M., Elbakry, M. M. M., Tisato, V., Awad, K., & Singh, A. V. (2024). Navigating the COVID-19 Therapeutic Landscape: Unveiling Novel Perspectives on FDA-Approved Medications, Vaccination Targets, and Emerging Novel Strategies. Molecules, 29(23), 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29235564