Abstract

The ability to fabricate bimetallic clusters with atomic precision offers promising prospects for elucidating the correlations between their structures and properties. Nevertheless, achieving precise control at the atomic level in the production of clusters, including the quantity of dopant, characteristic of ligands, charge state of precursors, and structural transformation, have remained a challenge. Herein, we report the synthesis, purification, and characterization of a new bimetallic hydride cluster, [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] (AuCu11H). The hydride position in AuCu11H was determined using DFT calculations. AuCu11H comprises a ligand-stabilized defective fcc Au@Cu11 cuboctahedron. AuCu11H is metastable and undergoes a spontaneous transformation through ligand exchange into the isostructural [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] (AuCu11Cl) and into the complete cuboctahedral [AuCu12{S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+ (AuCu12) through an increase in nuclearity. These structural transformations were tracked by NMR and mass spectrometry.

1. Introduction

Structural transformation in atomically precise metal nanoclusters (NCs) is important not only to investigate their structure–property relationships but also to serve as a unique platform for exploring structural evolution [1,2,3]. In the past decade, research in the field of structural NC transformations has broadened significantly, and many NCs resulting from structural evolutions have been synthesized [4,5,6]. The structural transformation of the metal core process can occur in certain metal NCs under suitable conditions, such as redox treatment [7,8], pH induction [9,10], ligand exchange [11,12], and elevated temperatures [13,14,15,16,17]. It can lead to the formation of structural isomers of various sizes [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. While the structural transformation of pure and alloyed gold and silver clusters has been extensively studied, there has been limited research on their copper homologues [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. A noticeable example, reported by Zhu et al., is the PPh3 addition to [Cu41(SC6H3F2)15(P(PhF)3)6Cl3H25]2− that induces the conversion into [Cu14(SC6H3F2)3(PPh3)8H10]+, while the addition of P(PhF)3 converts it into [Cu13(SC6H3F2)3(P(PhF)3)7H10] [33]. Another remarkable example reported by Zang et al. is the step-by-step controlled preparation of two catalytically active carborane alkynyl-protected copper NCs, namely [Cu13(C4B10H11)10(PPh3)2(CH3CN)2]3+ and [Cu26(C4B10H11)16(C2B9H10C2)2(PPh3)2(CH3CN)4]4+, through external ligand shell modifications and metal-core evolution [34]. We also reported the structural transformation under acidic conditions of the cuboctahedral [Cu12S{S2CNnBu}2(C2Ph)4] into the fused bi-cuboctahedral [Cu21S2{S2CNnBu2}9(C2Ph)6] [35] and the spontaneous transformation in a chlorinated solvent of [Cu15H2{S2CNnBu2}6(C2Ph)4]+ into the [Cu13{S2CNnBu2}6(C2Ph)4]+ two-electron superatom [36].

It is to be noted that research on NC transformation has generally focused on stable species, while the analysis of the structural evolution of metastable NCs has only begun to receive attention in the last few years [37,38,39,40,41]. Capturing metastable clusters with a labile nature provides valuable information for understanding the pathways of metal NC transformations [42]. From this point of view, hydride-stabilized NCs constitute a privileged field of investigations [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Indeed, the coordination diversity and H-dissociation behavior in hydride-ligated NCs make them a dynamic system that can facilitate structural modifications [47]. The relatively weak M-H bond allows for the easy substitution of hydrides by other ligands, which is an effective way to obtain the evolution of intermediates [47,49]. In this context, by introducing a hydride ligand on two-electron superatoms, Au-Cu alloy NCs, the structural transformation pathway is expected to be particularly studied at the simplified hydride-binding site. To the best of our knowledge, no two-electron superatom Au-doped Cu-rich hydride has been reported so far, and hydride ligands are still rarely observed in alloy nanoclusters [50]. This work aims to obtain the isostructural Au-Cu bimetallic cluster and acquire insight into the underlying mechanism of transformation of a two-electron superatom, thereby enhancing its nuclearity.

2. Results and Discussion

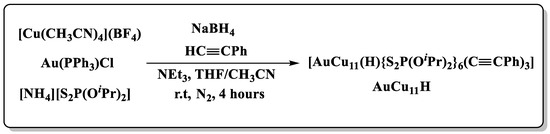

AuCu11H was first prepared by a one-pot procedure with mixed solvent THF-CH3CN (1:1). The synthetic procedure of AuCu11H differs from that reported in AuCu11Cl [25] and AuCu12 [26]. The synthesis protocol involves the reduction of copper and gold precursors with the reducing agent NaBH4 in the presence of alkynyl, trimethylamine, and dithiophosphate (dtp) ligands (Scheme 1). The yellowish-green mixture immediately turned yellow after addition of the reducing agent and finally dark brown after stirring for 4 h at ambient temperature. The resulting mixture was evaporated by a rotavapor to give a dark brown solid. This solid was purified by an aluminum oxide column to afford an orange-red precipitate of AuCu11H in 13% yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis route for AuCu11H.

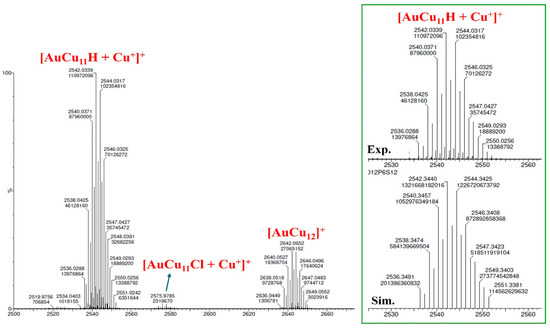

The deuterated derivatives [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] (AuCu11D) were also synthesized to support the existence of the hydride in the clusters. Synthetic details are provided in the supporting information. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in a positive mode was performed to verify the molecular formula of AuCu11H. The ESI-MS spectra of AuCu11H (Figure 1 and Table 1) show two prominent peaks at m/z = 2542.03 and 2642.37 Da, which correspond to the molecular weight of AuCu11H with an adduct of one copper ion, [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+ (m/z calc. = 2542.34 Da), and the molecular ion [AuCu12{S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+ (m/z calc. = 2642.37 Da), respectively. The smaller peak can be ascribed to [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+ at m/z = 2575.96 Da (m/z calc. = 2575.31 Da). The measured isotopic pattern fully matches with the simulated pattern (Figure 1 (inset) and Figure S1). To confirm the number of hydride(s), a controlled preparation with NaBD4 was performed to obtain the deuterated AuCu11D. The ESI-MS analysis of AuCu11D depicts two intense peaks at m/z = 2543.37 Da (m/z calc. = 2543.35 Da) and 2478.43 Da (m/z calc. = 2478.41 Da) (Figure S2), which correspond to the molecular weight of AuCu11D with a copper adduct ion, [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+, and neutral [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3], respectively. The mass spectra also display the molecular ion [AuCu12{S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+ at m/z = 2642.40 Da (m/z calc. = 2642.37 Da) (Figure S2). A distinct shift of m/z = 1.34 is observed between the mass of AuCu11H and AuCu11D, confirming that the total number of hydrides in AuCu11H is one. The theoretically determined isotopic patterns of [AuCu11D + Cu+]+, [AuCu11D], and [AuCu12]+ show excellent agreement with the experiment, as depicted in Figures S2 (inset) and S3, respectively.

Figure 1.

ESI-MS spectra of [AuCu11H + Cu+]+. The inset shows the comparison between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope patterns for [AuCu11H + Cu+]+.

Table 1.

The positive-mode ESI-MS of [AuCu11H+Cu+]+.

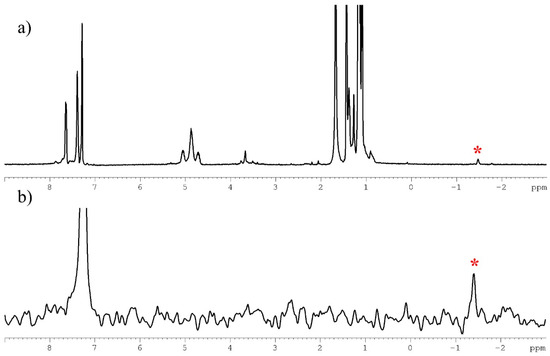

The 1H NMR spectrum of AuCu11H is shown in Figure 2. The presence of the hydride is confirmed with a chemical shift at –1.49 ppm (Figure 2a). The peak integration ratios indicate six dtp and three alkynyl ligands to one hydride. The signals at 4.69–5.06 and 1.07–1.43 ppm in a 1:6 intensity ratio are attributed to the -OCH and CH3 protons of the dtp isopropyl groups, respectively (Figure 2a). In addition to the isopropyl peaks, the spectrum also shows the two peaks of the alkynyl protons at 7.39–7.64 ppm. The corresponding deuterated resonance in the 2H NMR spectra of AuCu11D confirms the position of the hydride with relatively similar resonances observed at −1.41 ppm. (Figure 2b and Figure S4). The 31P{1H} spectrum of AuCu11H displays three signals at 104.4, 100.5, and 99.9 ppm attributed to three types of di-isopropyl dithiophosphate ligands in a symmetrical structure AuCu11H (Figures S5 and S6). In the 13C NMR spectrum, the peaks at 23.2 and 77.2 ppm are assigned to the isopropyl group of dithiophosphates, followed by the peaks at 125.2, 128.9, 132.3, 134.1, and 77.2 and 137.4 ppm corresponding to the aromatic carbons of the phenyl rings and the carbon atoms of the C≡C functional groups, respectively (Figure S7). A similar synthetic procedure was conducted to obtain two derivatives of AuCu11H by using di-n-propyl and di-isobutyl dithiophosphate ligands and 4-ethylanisole. All their spectroscopic data are consistent with the proposed formula (see Materials and Methods section, Figures S8–S20).

Figure 2.

(a) The 1H NMR spectrum of AuCu11H in CDCl3. (b) The 2H NMR spectrum of AuCu11H in CHCl3. The asterisk symbol signifies the hydride peak.

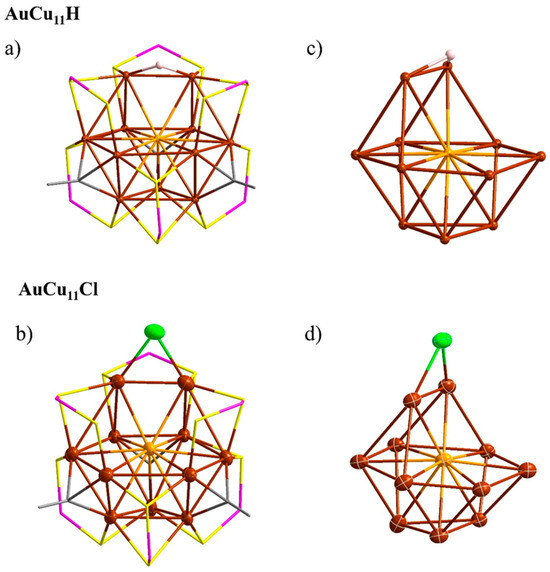

Due to the inherent instability of AuCu11H in solution, it was not possible to obtain a single crystal of AuCu11H. Nevertheless, a comparison of the NMR data collected for this compound with those of the isoelectronic AuCu11Cl [25] suggests strongly that both NCs have a similar structure. This hypothesis is also supported by the fact that the composition of the two compounds differs only by the nature of one ligand (H vs. Cl). Then, a geometry optimization of AuCu11H by means of density functional theory (DFT) at the PBE0/Def2-TZVP was performed (see computational details), starting from that of the AuCu11Cl parent, and indeed the converged structure presented similar features as its chloride homologue. Other structural arrangements were also tested, including several with different hydride positions on different metal atoms (including Au) and in different coordination modes, but the global minimum was found to remain definitely the same, i.e., both AuCu11H and AuCu11Cl are isostructural, including with respect to the location of the H vs. Cl ligand (see Figure 3). The secondary minimum of lowest energy was found to be at a much higher energy (ΔE = 1.40 eV) to allow considering any equilibrium in solution. In this isomer, the hydride is shifted on the opposite side of the vacancy and bridges an AuCu2 triangle (see SI). The AuCu11 core describes an Au-centered cuboctahedron of which one vertex is missing. This defective fcc Au@Cu11 core is decorated with four (µ2, µ2) and two (µ2, µ1) dtp ligands and three (µ3-η1) alkynyl ligands (Figure 3a,b). The hydride bridges one of the Cu-Cu edges, which borders the core vacancy. This location makes sense in the way that the hydride (or chloride in the case of AuCu11Cl) is linked to the two copper atoms that would be the least connected metals if this ligand was missing. It is noteworthy that the hydride ligand in AuCu11H becomes closer to the central gold atom than the chloride in AuCu11Cl (Figure 3c,d). Nevertheless, the Au…H distance (2.851 Å) is of the order of magnitude of a van der Waals contact, whereas the corresponding Cu-H distances of AuCu11H (1.633 Å) correspond to standard Cu-(µ2-H) bonds. Other average computed metrical data are provided in Table 2. They are comparable to those previously calculated for AuCu11Cl [25], also reported in Table 2 for comparison.

Figure 3.

The DFT-optimized structure of AuCu11H and the X-ray structure of AuCu11Cl [41]: (a,b) overall structures; (c,d) the Au@Cu11 cuboctahedral core with the bridging hydride–chloride ligand. All the phenyl rings of alkynyls and the alkyl group of dtp ligands are omitted for clarity. Color labels: dark red = Cu; orange = Au; yellow = S; magenta = P; pink = H; green = Cl, gray = C.

Table 2.

Selected DFT-computed data for AuCu11H and AuCu11Cl a.

The calculated 1H NMR chemical shift (see SI for computational details) of the hydride (1.3 ppm) is in a satisfying agreement with the experimental value (−1.49 ppm), owing to the fact that a discrepancy of ~3 ppm is not uncommon for metal-bound hydrides in these types of clusters [51]. The computed chemical shifts of the ligand protons match well with the experiment, with averaged value of 7.3, 7.4, and 7.8 ppm (aromatic protons), 4.8 ppm (-OCH), and 0.8 ppm (CH3), as well as the 13C chemical shifts (88.4 and 140.4 (C≡C), 135.6, 128.4, 127.6, and 126.5 (aromatic carbons), and 70.3 and 20.2 (isopropyl carbons)).

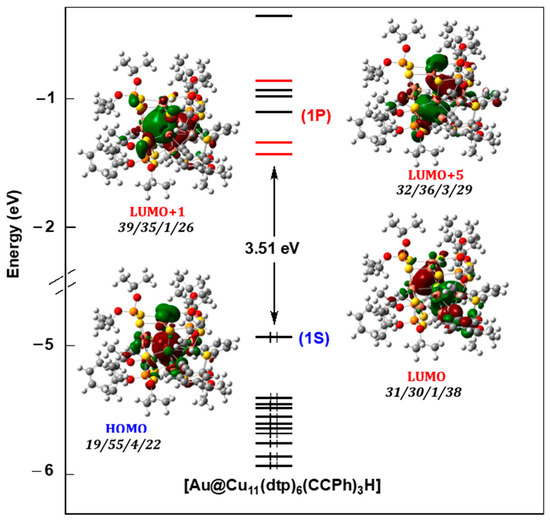

The KohnSham orbital diagram of AuCu11H (Figure 4) is typical of the two-electron superatoms based on a centered complete (closo-type) [52] or defective (nido-type) [25] cuboctahedron. It is characterized by a 1S HOMO with a dominant Au character. A peculiarity of this diagram is the fact that only two among the 1P orbitals are the lowest unoccupied levels, the third one being the LUMO+5. The somewhat higher energy of the latter could be due to some antibonding (weak) hydride admixture.

Figure 4.

The Kohn-Sham frontier orbital diagram of AuCu11H. The orbital contribution (in %) is given in the order Au/Cu11/H/ligands.

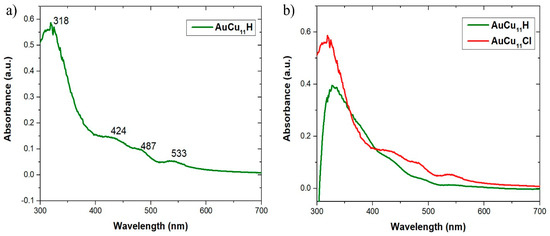

The UV-vis spectrum of AuCu11H is shown in Figure 5a. There are three weak bands at 424, 487, and 533 nm, and another highly structured one at 318 nm. Figure 5b compares the UV-vis absorption spectra of AuCu11H and AuCu11Cl. AuCu11Cl also displays four absorption peaks at 328, 432, 485, and 540 nm [25]. These similarities in the UV-vis spectra also support the fact that both NCs are isostructural. Their multiband absorption profiles are typical of superatom-type clusters (Figure S21) [25,26,29]. The TD-DFT-simulated spectrum of AuCu11H is shown in Figure S22. Owing to the shapeless nature of its experimental counterpart, the agreement is satisfying. A similar agreement was found for AuCu11Cl [25]. The broad band of lowest energy results from a combination of HOMO→LUMO and HOMO→LUMO+1 transitions; hence, it is of superatomic 1S→1P nature, whereas the high-intensity peak at high energy (322 nm) is found to be of MLCT character, resulting from transitions between Cu(3d) levels and π*(phenyl) combinations.

Figure 5.

(a) The experimental UV–vis absorption spectrum of AuCu11H in MeTHF. (b) Comparison of UV-vis absorption spectra of AuCu11H and AuCu11Cl in MeTHF.

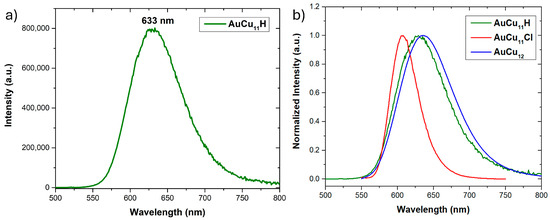

The photoluminescence (PL) properties of the twoelectron superatomic AuCu11H and AuCu11Cl relatives were analyzed and compared (Figure 6). Both NCs are emissive at ambient temperatures in MeTHF. The excitation spectrum of AuCu11H, shown in Figure S23, is closely related to its absorption UV-vis spectrum. Upon exciting at 437 nm, AuCu11H (in MeTHF) emits at 633 nm, with a PL quantum yield (QY) of 32.7%. On the other hand, AuCu11Cl emits at 606 nm, with a ten times lower PL QY of 3.3% [25]. Interestingly, the emission band of AuCu11H is close to that of AuCu12 at 637 nm, with a QY of 32% [26]. Thus, the PL QY for the two-electron Au-doped Cu-rich alloy clusters follows the order AuCu12 > AuCu11H > AuCu11Cl. The PL lifetime of AuCu11H is 1.71 μs (Figure S24), whereas that of AuCu11Cl and AuCu12 were determined to be 3.75 and 3.20 μs. Such a PL lifetime quenching is attributed to the hydride-chloride exchange and reveals the instability of AuCu11H in solution. Nevertheless, the high QY of AuCu11H (krad = 0.19 μs−1) might originate from a similar value of the radiative rate constant as AuCu12 (krad = 0.10 μs−1) (Table S1) [25,26].

Figure 6.

(a) The emission spectrum of AuCu11H. (b) Comparison emission spectra of AuCu11H, AuCu11Cl, and AuCu12 in MeTHF at ambient temperature.

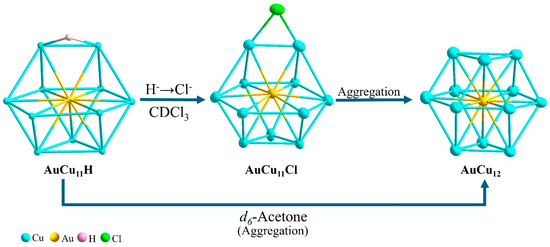

AuCu11H is metastable in solution, spontaneously converting into AuCu11Cl and AuCu12 (Scheme 2). The transformation process was monitored by both time-dependent NMR spectroscopy in different types of solvents and ESI-MS analysis. A non-chlorinated solvent was first employed for the investigation. As shown in Scheme 2, a direct conversion of AuCu11H into AuCu12 occurs in acetone. The 1H NMR chemical shift of the isopropyl groups in AuCu11H gradually merges with time and shows good agreement with the chemical shift of the isopropyl group in AuCu12 (Figures S25 and S26). No hydride peak can be identified in the 1H NMR spectrum after 24 h. Moreover, whereas the time-dependent 31P{1H} NMR spectra of AuCu11H exhibited single sharp peaks at 104.4, 100.5, and 99.9 ppm, respectively, the sharp resonances at 104.4 and 99.9 coalesced into a single sharp peak of 100.5 ppm, which correlates to the 31P{1H} chemical shift of AuCu12 (Figures S27 and S28). This is also supported by the ESI-MS spectrometry, as depicted in Figures S29 and S30. Thus, during the conversion, AuCu11H undergoes aggregation and is accompanied by the rearrangement of the core structure from a vacancy defect Au@Cu11 cuboctahedron to a full Au@Cu12 cuboctahedron after the successive addition of one copper acetylide unit.

Scheme 2.

Structural transformation of AuCu11H to AuCu12 via AuCu11Cl in solution.

In contrast, the conversion of AuCu11H in a chlorinated solvent leads to the formation of AuCu12 via AuCu11Cl (Scheme 2). The 1H NMR spectra identified that the hydride peak gradually vanished after 48 h (Figure S31). As shown in Figure S32, the intensity of the 31P{1H} peaks of AuCu11H at 104.4 and 99.9 ppm decreases with time, followed by a new peak at 97.8 ppm, which corresponds to the 31P{1H} chemical shift of AuCu11Cl (Figure S33). These time-dependent spectra suggest that the presence of the chloride ion from the chlorinated solvent triggered the hydride-chloride exchange, and the hydride tends to dissociate, releasing H+ and being replaced by the chloride ion [25]. Hydride and chloride exchange slowly, giving rise to a weak AuCu11Cl signal at m/z = 2578.32 Da (m/z calc = 2578.30 Da) in the mass spectrum (Figures S34 and S35). Furthermore, this transformation is followed by the degradation of AuCu11Cl to AuCu12 through a partial aggregation process [25]. These results are supported by the 31P{1H} NMR resonance at 97.8 ppm, which shifts to 100.7 ppm within 96 h, i.e., to the chemical shift of AuCu12. We thus propose that transformation in the chlorinated solvent allows the metastable AuCu11H to be the key precursor in the formation of AuCu12 through AuCu11Cl. The time-dependent 1H NMR of AuCu11H in the chlorinated solvent shows the characteristic of a hydride ligand, indicating less stability of AuCu11H in the solution. Based on this result, the hydride in AuCu11H acts as an electron-withdrawing hydride, as shown by the dissociation of H− and subsequently followed by the replacement of the chloride ligand to generate AuCu11Cl. In addition, AuCu11Cl grows via partial aggregation to form AuCu12 following the sequential addition of one copper acetylide unit (Scheme S1). This study shows that Au-Cu bimetallic NCs grow by creating a hydride bimetallic complex and then exchanging ligands with H− dissociation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Remarks

All chemicals were used without further purification and purchased from commercial sources as follows: phenylacetylene, sodium borohydride, sodium borodeuteride, and all the required anhydrous solvents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. All reactions were conducted in a N2 atmosphere utilizing typical Schlenk procedures. [Cu(CH3CN)4](PF6) [53], Au(PPh3)Cl [54], and [NH4][S2P(OR)2] (R = iPr, nPr, and iBu) [55] were synthesized according to the methodology documented in the literature and then described. NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker Advance DPX300 FT-NMR spectrometer running at 400 MHz for 1H, 121.5 MHz for 31P{1H}, 100.61 MHz for 13C{1H}, and 46.1 MHz for 2H. The 1H NMR chemical shift was referenced to residual CDCl3 (δ = 7.26 ppm) and deuterated acetone (δ = 2.04 ppm). The 13C{1H} NMR spectra were referenced to deuterated acetone (δ = 29.8 and 206.3 ppm). The 31P{1H} NMR spectra were referenced to external 85% H3PO4 at δ = 0 ppm. The chemical shift (δ) is expressed in ppm, and processing was carried out with Bruker’s Topspin 2.1 software. The ESI-mass spectrometry was obtained using a Fison Quattro Bio-Q (Fisons Instruments, VG Biotech, U.K.). The UV–visible absorption spectra were acquired using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 750 spectrophotometer with quartz cells featuring a 1 cm path length. An Edinburgh FLS920 spectrophotometer captured the photoluminescence excitation and emission spectra using the Xe900 lamp as the excitation source. The PL decays were assessed utilizing an Edinburgh FLS920 spectrometer equipped with a gated hydrogen arc lamp and a scattering solution to characterize the instrument response function.

3.2. General Synthesis

The clusters [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3], [AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3], and [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPh)3] can be prepared by following general procedures, and a detailed preparation method is given for cluster [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] (AuCu11H).

3.2.1. Synthesis of [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] (AuCu11H)

In a Flame-dried Schlenk tube [NH4][S2P{OiPr}2] (30 mg, 0.15 mmol), Cu(CH3CN)4](BF4) (130 mg, 0.30 mmol) and Au(PPh3)Cl (4 mg, 0.1 mmol) were suspended in a mixture of THF (15 cm3) and CH3CN (15 cm3) followed by the continuous addition of phenylacetylene (40 µL, 0.3 mmol) and triethylamine (40 µL, 0.3 mmol). After stirring for 5 min, NaBH4 (6 mg, 0.15 mmol) was added to the mixture. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. The solvent was evaporated under vacuum, and the residue was dissolved in DCM and washed with water (3 × 15 mL). After separation, the organic layer was passed through aluminum oxide, and the orange-red residue was washed with ether and ethyl acetate to get rid of the impurities. The precipitate was then dissolved in methanol (3 × 15 mL) to collect the orange-red solution. Finally, the solvent was evaporated to dryness under vacuum to obtain a pure orange-red powder of AuCu11H. The yield was 13% based on Cu.

Similarly, the deuterium analog [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] was synthesized by reacting NaBD4 (0.0042, 0.15 mmol), resulting in the formation of [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] (15%, based on Cu).

[AuCu11H]: ESI-MS: m/z 2542.37 Da (calcd. m/z 2542.34 Da) for [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.39 (8H, d, C6H5), 7.64 (7H, d, C6H5), 4.69–5.06 (12H, m, OCH), 1.07–1.43 (72H, dd, CH3), and −1.49 (1H, s, μ2-H) ppm. 31P NMR (121.5 MHz, CDCl3): 104.45, 100.49, and 99.90 ppm. 13C NMR (100.61 MHz, d6-acetone): 205.33 (CH3COCH3), 29.84 (CH3COCH3), 134.08 (o-C6H6), 132.27 (o-C6H6), 128.85 (p-C6H6), 125.17 (p-C6H6), 77.80 (C≡C), 76.18 (C≡C), 34.13 (-OCH(CH3)2), and 23.22 (-OCH(CH3)2).

[AuCu11D]: ESI-MS: m/z 2543.37 Da (calcd. m/z 2543.35 Da) for [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.35 (8H, d, C6H5), 7.63 (7H, d, C6H5), 4.67–5.05 (12H, m, OCH), and 1.05–1.42 (72H, dd, CH3). 31P NMR (121.5 MHz, CDCl3): 104.45, 100.50, and 99.91 ppm. 2H NMR (400 MHz, CHCl3): −1.41 (1D, s, μ2-D) ppm.

3.2.2. [AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3]

[AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3]: ESI-MS: m/z 2542.37 Da (calcd. m/z 2542.34 Da) for [AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+; m/z 2578.32 Da (cacld. m/z 2578.30 Da) for [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+; m/z 2642.39 Da (calcd. m/z 2642.37 Da) for [AuCu12{S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.48–7.70 (15H, C6H5), 3.94–4.26 (24H, OCH2), 1.27–1.73 (24H, CH2), 0.72–1.01 (36H, CH3), and −1.48 (1H, μ2-H) ppm. 31P NMR (121.5 MHz, CDCl3): 109.7, 106.2, and 105.9 ppm.

[AuCu11(D){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3]: ESI-MS: m/z 2543.44 Da (calcd. m/z 2543.35 Da) for [AuCu11(D){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3 + Cu+]+; m/z 2642.46 Da (calcd. m/z 2642.37 Da) for [AuCu12{S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.37–7.59 (15H, C6H5), 3.99–4.26 (24H, OCH2), 1.34–1.76 (24H, CH2), and 0.75-.0.98 (36H, CH3). 31P NMR (121.5 MHz, CDCl3): 110.1 106.3, and 105.4 ppm. 2H NMR (400 MHz, CHCl3): −1.40 (1D, s, D) ppm.

3.2.3. [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3]

[AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3]: ESI-MS: m/z 2800.59 Da (calcd. m/z 2800.56 Da) for [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+; m/z 2834.52 Da (cacld. m/z 2834.52 Da) for [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+; m/z 2932.64 Da (calcd. m/z 2932.66 Da) for [AuCu12{S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)4]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 6.86–7.57 (12H, C6H5OCH3), 3.71–4.00 (24H, OCH), 3.81 (3H, C6H5OCH3), 1.55–1.72 (12H, CH2), 0.76–1.00 (36H, CH3), and −1.63 (1H, μ2-H) ppm. 31P NMR (121.5 MHz, CDCl3): 109.6, 105.6, and 104.9 ppm.

[AuCu11(D){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3]: ESI-MS: m/z 2801.55 Da (calcd. m/z 2801.57 Da) for [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+; m/z 2672.52 Da (calcd. m/z 2671.70 Da) for [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3]. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 6.86–7.57 (12H, C6H5OCH3), 3.71–4.00 (24H, OCH), 3.81 (3H, C6H5OCH3), 1.55–1.72 (12H, CH2), and 0.76–1.00 (36H, CH3). 31P NMR (121.5 MHz, CDCl3): 109.6, 105.6, and 104.9 ppm. 2H NMR (400 MHz, CHCl3): −1.74 (1D, s, D) ppm.

3.3. Computational Details

Geometry optimizations were performed by DFT calculations with the Gaussian 16 package [56] using the PBE0 functional [57] and the all-electron Def2-TZVP basis set from the EMSL Basis Set Exchange Library [58]. All the optimized geometries were characterized as true minima on their potential energy surface by harmonic vibrational analysis. The Wiberg bond indices were computed with the NBO 6.0 program [59]. The UV–visible transitions were calculated by means of TD-DFT calculations [60]. Only singlet–singlet, i.e., spin-allowed, transitions were computed. The UV–visible spectra were simulated from the computed TD-DFT transitions and their oscillator strengths by using the SWizard program [61], each transition being associated with a Gaussian function of half-height width equal to 2000 cm−1. The compositions of the molecular orbitals were calculated using the AOMix program [62], and the NMR chemical shifts were calculated by using the gauge-including atomic orbital (GIAO) method [63]. All calculations correspond to the molecule in vacuum.

4. Conclusions

We report here the synthesis and characterization of the bimetallic hydride cluster AuCu11H. The combination of spectroscopic methods and DFT calculations allowed establishing that AuCu11H has a similar structure as its AuCu11Cl relative. Its ligand-protected metallic core is composed of a defective Au@Cu11 cuboctahedron. AuCu11H is metastable and, in a chlorinated solvent, undergoes a spontaneous ligand-exchange transformation into AuCu11Cl and aggregates into the AuCu12 NC of increased nuclearity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules29184427/s1, Figure S1. Comparison between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope patterns of peaks (a) [AuCu11Cl+Cu+]+ and (b) [AuCu12]+; Figure S2. ESI-MS spectra [AuCu11D+Cu+]+. The insets show the comparisons between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope patterns for [AuCu11D+Cu+]+; Figure S3. Comparisons between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope patterns of peaks (a) [AuCu11D] and (b) [AuCu12]+; Figure S4. 1H NMR spectrum of AuCu11D in CDCl3; Figure S5. 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of AuCu11H in CDCl3; Figure S6. 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of AuCu11D in CDCl3; Figure S7. 13C NMR spectrum of AuCu11H in d6-acetone; Figure S8. The ESI-MS spectrum of [AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3+Cu+]+ (I), [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3+Cu+]+ (II), and [AuCu12{S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+ (III); Figure S9. Comparisons between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope patterns of peaks (a) [AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3+Cu+]+ (I), (b) [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3+Cu+]+ (II), and (c) [AuCu12{S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+ (III); Figure S10. The ESI-MS spectrum of [AuCu11(D){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3+Cu+]+ (I) and [AuCu12{S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+ (II); Figure S11. Comparisons between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope patterns of peaks (a) [AuCu11(D){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3+Cu+]+ (I) and (b) [AuCu12{S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)4]+ (II); Figure S12. The ESI-MS spectrum of [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+ (I), [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+ (II), and [AuCu12{S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)4]+ (III); Figure S13. Comparisons between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope patterns of peaks (a) [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+ (I), (b) [AuCu11(Cl){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+ (II), and (c) [AuCu12{S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)4]+ (II); Figure S14. The ESI-MS spectrum of [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+ (I) and [AuCu10{S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3]+ (II). Inset: Comparisons between the experimental data (top) and the simulated (bottom) isotope pattern of peak (a) [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3+Cu+]+ (I); Figure S15. 1H NMR spectrum of [AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] in CDCl3; Figure S16. 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of [AuCu11(H){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] in CDCl3; Figure S17. 2H NMR spectrum of [AuCu11(D){S2P(OnPr)2}6(C≡CPh)3] in CHCl3; Figure S18. 1H NMR spectrum of [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3] in CDCl3; Figure S19. 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of [AuCu11(H){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3] in CDCl3; Figure S20. 2H NMR spectrum of [AuCu11(D){S2P(OiBu)2}6(C≡CPhOCH3)3] in CHCl3; Figure S21. Comparison of the UV–vis absorption spectra of AuCu11H, AuCu11Cl, and AuCu12 in 2-MeTHF solution; Figure S22. The TD-DFT-simulated UV–vis spectrum of AuCu11H, with individual transitions as vertical bars of lengths proportional to their oscillator strengths; Figure S23. (a) The UV–vis absorption spectrum of AuCu11H. (b) The excitation spectrum of AuCu11H in 2-MeTHF solution at ambient temperature; Figure S24. The emission lifetime of cluster AuCu11H at ambient temperature; Figure S25. Structural transformation of AuCu11H into AuCu12 in d6-acetone monitored by time-dependent 1H NMR spectroscopy; Figure S26. 1H NMR spectrum of AuCu12 in d6-acetone; Figure S27. Structural transformation of AuCu11H into AuCu12 in d6-acetone monitored by time-dependent 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy; Figure S28. 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of AuCu12 in d6-acetone; Figure S29. Positive-mode ESI-MS spectra of structural transformation of AuCu11H in acetone; Figure S30. Isotope pattern of (a) AuCu11H and (b) AuCu12 in structural transformation; inset shows experimental (black) and simulated (red) isotopic distribution pattern; Figure S31. Structural transformation of AuCu11H into AuCu12 via AuCu11Cl in CDCl3 monitored by time-dependent 1H NMR spectroscopy; Figure S32. Structural transformation of AuCu11H into AuCu12 via AuCu11Cl in CDCl3 monitored by time-dependent 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy; Figure S33. 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of AuCu11Cl in CDCl3; Figure S34. Positive-mode ESI-MS spectra of structural transformation of AuCu11H in CH2Cl2; Figure S35. Isotope patten of (a) AuCu11H, (b) AuCu11Cl, and (c) AuCu12 in structural transformation; inset shows experimental (black) and simulated (red) isotopic distribution pattern; Figure S36. 1H NMR spectrum of AuCu11Cl in d6-acetone; Table S1. The 298 K absorption, emission, and lifetime of AuCu11H, AuCu11Cl, and AuCu12; Scheme S1. A proposed mechanism of chloride–hydride ligand exchange, and aggregation within the transformation core of AuCu11H to AuCu12 via AuCu11Cl in chloride-containing solvent; Table S2. Cartesian coordinates of the DFT-optimized structure of AuCu11H and its high-energy isomer.

Author Contributions

Synthesis, R.P.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.B.S.; conceptualization, J.-Y.S. and C.W.L.; software, S.K. and J.-Y.S.; validation, S.K. and J.-Y.S.; formal analysis, S.K. and J.-Y.S.; investigation, S.K. and J.-Y.S.; data curation, S.K. and J.-Y.S.; writing—review and editing, J.-Y.S. and C.W.L.; supervision, C.W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (113-2123-M-259-001) and the GENCI computing resource (grant A0090807367).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Dong Hwa University and the University of Rennes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jin, R.; Zeng, M.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Y. Atomically Precise Colloidal Metal Nanoclusters and Nanoparticles: Fundamentals and Opportunities. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10346–10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, I.; Pradeep, T. Atomically Precise Clusters of Noble Metals: Emerging Link between Atoms and Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8208–8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonacchi, S.; Antonello, S.; Dainese, T.; Maran, F. Atomically Precise Metal Nanoclusters: Novel Building Blocks. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, X.; Zhu, M. Transformation of Atomically Precise Nanoclusters by Ligand-Exchange. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 9939–9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Teo, B.K.; Zheng, N. Surface Chemistry of Atomically Precise Coinage–Metal Nanoclusters: From Structural Control to Surface Reactivity and Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 3084–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Chai, J.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Higaki, T.; Li, S.; Jin, R. Fusion growth patterns in atomically precise metal nanoclusters. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 19158–19165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lv, Y.; Jin, S.; Yu, H.; Zhu, M. Size Growth of Au4Cu4: From Increased Nucleation to Surface Capping. ACS Nano. 2023, 17, 8613–8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tan, Y.; Li, T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, P.; Yang, S.; Yu, H.; Zhu, M. Insight into the Role of Copper in the Transformation of a [Ag25(2,5-DMBT)16(DPPF)3]+ Nanocluster: Doping or Oxidation. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 18450–18457. [Google Scholar]

- Waszkielewicz, M.; Olesiak-Banska, J.; Comby-Zerbino, C.; Bertorelle, F.; Dagany, X.; Bansal, A.K.; Sajjad, M.T.; Samuel, I.D.W.; Sanader, Z.; Rozycka, M.; et al. pH-induced transformation of captopril-capped Au25 to brighter Au23 nanoclusters. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 11335–11341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Bai, Y.; Li, Q.; Yao, X.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; Meng, X.; Yu, H.; Zhu, M. Steric and Electrostatic Control of the pH-Regulated Interconversion of Au16(SR)12 and Au18(SR)14 (SR: Deprotonated Captopril). Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 5394–5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Sundar, A.; Nair, A.S.; Maman, M.P.; Pathak, B.; Ramanan, N.; Mandal, S. Identification of Intermediate Au22(SR)4(SR′)14 Cluster on Ligand-Induced Transformation of Au25(SR)18 Nanocluster. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 4571–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.-H.; Zeng, H.-M.; Yu, Z.-N.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Z.-G.; Zhan, C.-H. Unusual structural transformation and luminescence response of magic-size silver(i) chalcogenide clusters via ligand-exchange. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 13337–13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dass, A.; Jones, T.C.; Theivendran, J.; Sementa, L.; Fortunelli, A. Core Size Interconversions of Au30(S-tBu)18 and Au36(SPhX)24. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 14914–14919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Liu, C.; Pei, Y.; Jin, R. Thiol Ligand-Induced Transformation of Au38(SC2H4Ph)24 to Au36(SPh-t-Bu)24. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 6138–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Kang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M. Light-Induced Size-Growth of Atomically Precise Nanoclusters. Langmuir 2019, 35, 12350–12355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-M.; Liao, J.-H.; Chiu, T.-H.; Liang, H.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Superatom Pruning by Diphosphine Ligands as a Chemical Scissor. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 3866–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.-J.; Liao, J.-H.; Chiu, T.-H.; Wen, Y.-S.; Liu, C.W. A New Synthetic Methodology in the Preparation of Bimetallic Chalcogenide Clusters via Cluster-to-Cluster Transformations. Molecules 2021, 26, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, N.-N.; Dong, X.-Y.; Zang, S.-Q.; Mak, T.C.W. Chemical Flexibility of Atomically Precise Metal Clusters. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 7262–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouchoune, B.; Saillard, J.-Y. Atom-Precise Ligated Copper and Copper-Rich Nanoclusters with Mixed-Valent Cu(I)/Cu(0) Character: Structure–Electron Count Relationships. Molecules 2024, 29, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdasaryan, A.; Burgi, T. Copper nanoclusters: Designed synthesis, structural diversity, and multiplatform applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 6283–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hu, D.; Xiong, L.; Li, Y.; Kang, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M. Isomer Structural Transformation in Au–Cu Alloy Nanoclusters: Water Ripple-Like Transfer of Thiol Ligands. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2019, 36, 1800494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.K.; Yang, H.; Luo, D.; Xie, M.; Tang, W.J.; Ning, G.H.; Li, D. Enhancing Photoluminescence Efficiency of Atomically Precise Copper(I) Nanoclusters Through a Solvent-Induced Structural Transformation. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 5327–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Yuan, S.-F.; Wang, S.; Guan, Z.-J.; Jiang, D.-E.; Wang, Q.-M. Structural transformation and catalytic hydrogenation activity of amidinate-protected copper hydride clusters. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Wu, X.; Yin, B.; Kang, X.; Lin, Z.; Deng, H.; Yu, H.; Jin, S.; Chen, S.; Zhu, M. Structured copper-hydride nanoclusters provide insight into the surface-vacancy-defect to non-defect structural evolution. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 14357–14365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, R.P.B.; Wang, Q.; Liao, J.-H.; Chiu, T.-H.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Wang, X.; Khalal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Reactivities of Interstitial Hydrides in a Cu11 Template: En Route to Bimetallic Clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 134, e202113266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, R.P.B.; Chiu, T.-H.; Kao, J.-J.; Wu, C.-Y.; Yin, C.W.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.J.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Chiang, M.-H.; Liu, C.W. Synthesis and Luminescence Properties of Two-Electron Bimetallic Cu–Ag and Cu–Au Nanoclusters via Copper Hydride Precursor. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 10799–10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.K.; Huo, S.-C.; Wu, C.-Y.; Chiu, T.-H.; Liao, J.-H.; Wang, X.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Polyhydrido Copper Nanoclusters with a Hollow Icosahedral Core: [Cu30H18{E2P(OR)2}12] (E = S or Se; R = nPr, iPr or iBu). Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 10471–10479. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrahari, K.K.; Silalahi, R.P.B.; Chiu, T.-H.; Wang, X.; Azrou, N.; Kahlal, S.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chiang, M.-H.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Synthesis of Bimetallic Copper-Rich Nanoclusters Encapsulating a Linear Palladium Dihydride Unit. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4943–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, R.P.B.; Chakrahari, K.K.; Liao, J.-H.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chiang, M.-H.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Synthesis of Two-Electron Bimetallic Cu-Ag and Cu-Au Clusters by using [Cu13(S2CNnBu2)6(C≡CPh)4]+ as a Template. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 500–504. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrahari, K.K.; Liao, J.-H.; Kahlal, S.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chiang, M.-H.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. [Cu13{S2CNnBu2}6(acetylide)4]+: A Two-Electron Superatom. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14704–14708. [Google Scholar]

- Latouche, C.; Kahlal, S.; Furet, E.; Liao, P.K.; Lin, Y.R.; Fang, C.S.; Cuny, J.; Liu, C.W.; Saillard, J.Y. Shape Modulation of Octanuclear Cu(I) or Ag(I) Dichalcogeno Template Clusters with Respect to the Nature of Their Encapsulated Anions: A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Investigation. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 7752–7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.-A.D.; Jones, Z.R.; Leto, D.F.; Wu, G.; Scott, S.L.; Hayton, T.W. Ligand-Exchange-Induced Growth of an Atomically Precise Cu29 Nanocluster from a Smaller Cluster. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 8385–8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Duan, T.; Lin, Z.; Yang, T.; Deng, H.; Jin, S.; Pei, Y.; Zhu, M. Total Structure, Structural Transformation and Catalytic Hydrogenation of [Cu41(SC6H3F2)15Cl3(P(PhF)3)6(H)25]2− Constructed from Twisted Cu13 Units. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307085. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cai, J.; Ren, K.-X.; Liu, L.; Zheng, S.-J.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Zang, S.-Q. Stepwise structural evolution toward robust carboranealkynyl-protected copper nanocluster catalysts for nitrate electroreduction. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, T.-H.; Chiu, T.-H.; Liang, H.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. A heteroleptic fused bi-cuboctahedral Cu21S2 cluster. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 9638–9641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrahari, K.K.; Liao, J.P.; Silalahi, R.P.B.; Chiu, T.-H.; Liao, J.-H.; Wang, X.; Khalal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Isolation and Structural Elucidation of 15-Nuclear Copper Dihydride Clusters: An Intermediate in the Formation of a Two-Electron Copper Superatom. Small 2021, 17, 2002544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.-J.; Liao, J.-H.; Chiu, T.-H.; Kahlal, S.; Lin, C.-J.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.-W. A Two-Electron Silver Superatom Isolated from Thermally Induced Internal Redox Reactions of a Silver(I) Hydride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 12712–12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, S.; Chen, T.; Jin, S.; Chai, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, M. Structure Determination of a Metastable Au22(SAdm)16 Nanocluster and its Spontaneous Transformation into Au21(SAdm)15. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 23694–23699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Li, S.-J.; Zang, S.-Q.; Mak, T.C.W. Carboranealkynyl-Protected Gold Nanoclusters: Size Conversion and UV/Vis-NIR Optical Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 5959–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Duan, T.; Li, H.; Wei, X.; Kang, X.; Pei, Y.; Zhu, M. Structural determination of a metastable Ag27 nanocluster and its transformations into Ag8 and Ag29 nanoclusters. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 4407–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wei, X.; Xu, C.; Jin, S.; Wang, S.; Kang, X.; Zhu, M. Cocrystallization-driven stabilization of metastable nanoclusters: A case study of Pd1Au9. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 7694–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Selenius, E.; Ruan, P.; Li, X.; Yuan, P.; Lopez-Estrada, O.; Malola, S.; Lin, S.; Teo, B.K.; Hakkinen, H.; et al. Solubility-Driven Isolation of a Metastable Nonagold Cluster with Body-Centered Cubic Structure. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 48, 8465–8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasaruddin, R.R.; Yao, Q.; Chen, T.; Hulsey, M.J.; Yan, N.; Xie, J. Hydride-induced ligand dynamic and structural transformation of gold nanoclusters during a catalytic reaction. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 23113–23121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Gao, Z.-H.; Wang, L.-S. The synthesis and characterization of a new diphosphine protected gold hydride nanocluster. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 155, 034307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Luo, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, B.; Ding, M.; Wang, R.; Wang, P.; Pei, Y.; Wang, S. Poly-Hydride [AuI7(PPh3)7H5](SbF6)2 cluster complex: Structure, Transformation, and Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202300553. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Ma, W.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y. The structure–activity relationship of copper hydride nanoclusters in hydrogenation and reduction reactions. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1374–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tan, Y.; Huang, B.; Yang, S.; Chai, J.; Wang, X.; Pei, Y.; Zhu, M. Mechanistic Study of the Hydride Migration-Induced Reversible Isomerization in Au22(SR)15H Isomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15859–15868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.-N.; He, M.-W.; Wang, J.; Li, H.-Y.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Zang, S.-Q.; Mak, T.C.W. Thiacalix[4]arene Etching of an Anisotropic Cu70H22 Intermediate for Accessing Robust Modularly Assembled Copper Nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 3545–3552. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Kang, X.; Duan, T.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Pei, Y.; Zhu, M. [Au16Ag43H12(SPhCl2)34]5−: An Au−Ag Alloy Nanocluster with 12 Hydrides and Its Enlightenment on Nanocluster Structural Evolution. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 11640–11647. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, T.-H.; Liao, J.-H.; Silalahi, R.P.B.; Pillay, M.N.; Liu, C.W. Hydride-doped coinage metal superatoms and their catalytic applications. Nanoscale Horiz. 2024, 9, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.J.; Dhayal, R.S.; Liao, P.-K.; Liao, J.-H.; Chiang, M.-H.; Piltz, R.O.; Khalal, S.; Saillars, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Chinese Puzzle Molecule: A 15 Hydride, 28 Copper Atom Nanoball. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7214–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingos, D.M.P.; Wales, D.J. Introduction to Cluster Chemistry; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kubas, G.J. Tetrakis(Acetonitrile)Copper(I) Hexafluorophosphate. Inorg. Synth. 1979, 19, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister, J.L.; DeStefano, N. Cooperative electronic ligand effects in pseudohalide complexes of rhodium(I), iridium(I), gold(I), and gold(III) Inorganic Chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 1971, 10, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wystrach, P.; Hook, E.O.; Christopher, G.L.M. Perfluoroalkanes: Conformational Analysis and Liquid-State Properties from ab Initio and Monte Carlo Calculations. J. Org. Chem. 1956, 21, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16; Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–32305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D.; Badenhoop, J.K.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Bohmann, J.A.; Morales, C.M.; Landis, C.R.; Weinhold, F. NBO 6.0; Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2013; Available online: https://nbo6.chem.wisc.edu (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Ullrich, C. Time-Dependent Density-Functional Theory, Concepts and Applications; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelsky, S.I. Wizard Program. Revision 4.5. Available online: https://www.sg-chem.net (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Gorelsky, S.I. AOMix Program. Available online: https://www.sg-chem.net (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Wolinski, K.; Hilton, J.F.; Pulay, P. Efficient Implementation of the Gauge-Independent Atomic Orbital Method for NMR Chemical Shift Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8251–8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).