Effect of Dielectric Constant on the Zeta Potential of Spherical Electric Double Layers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

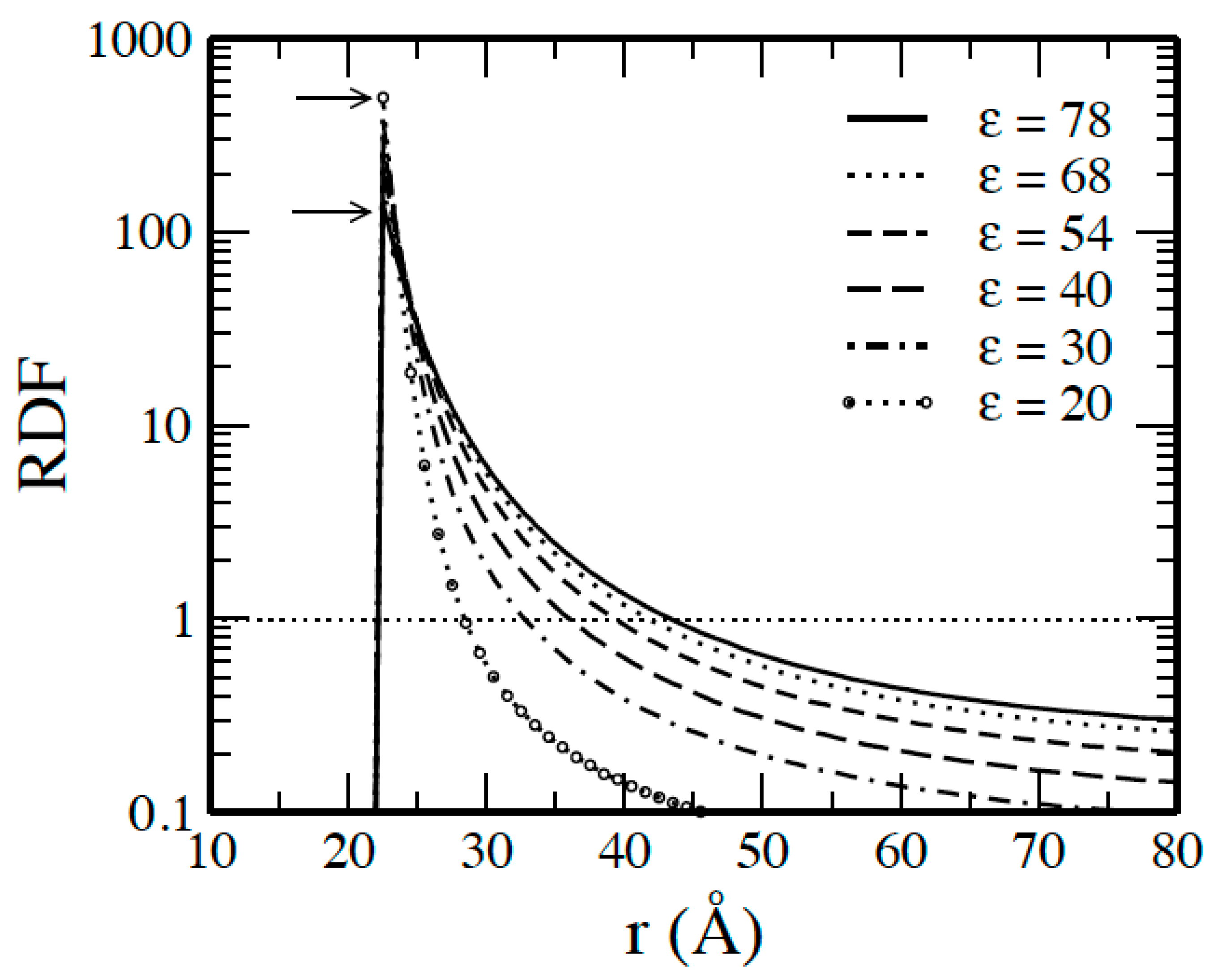

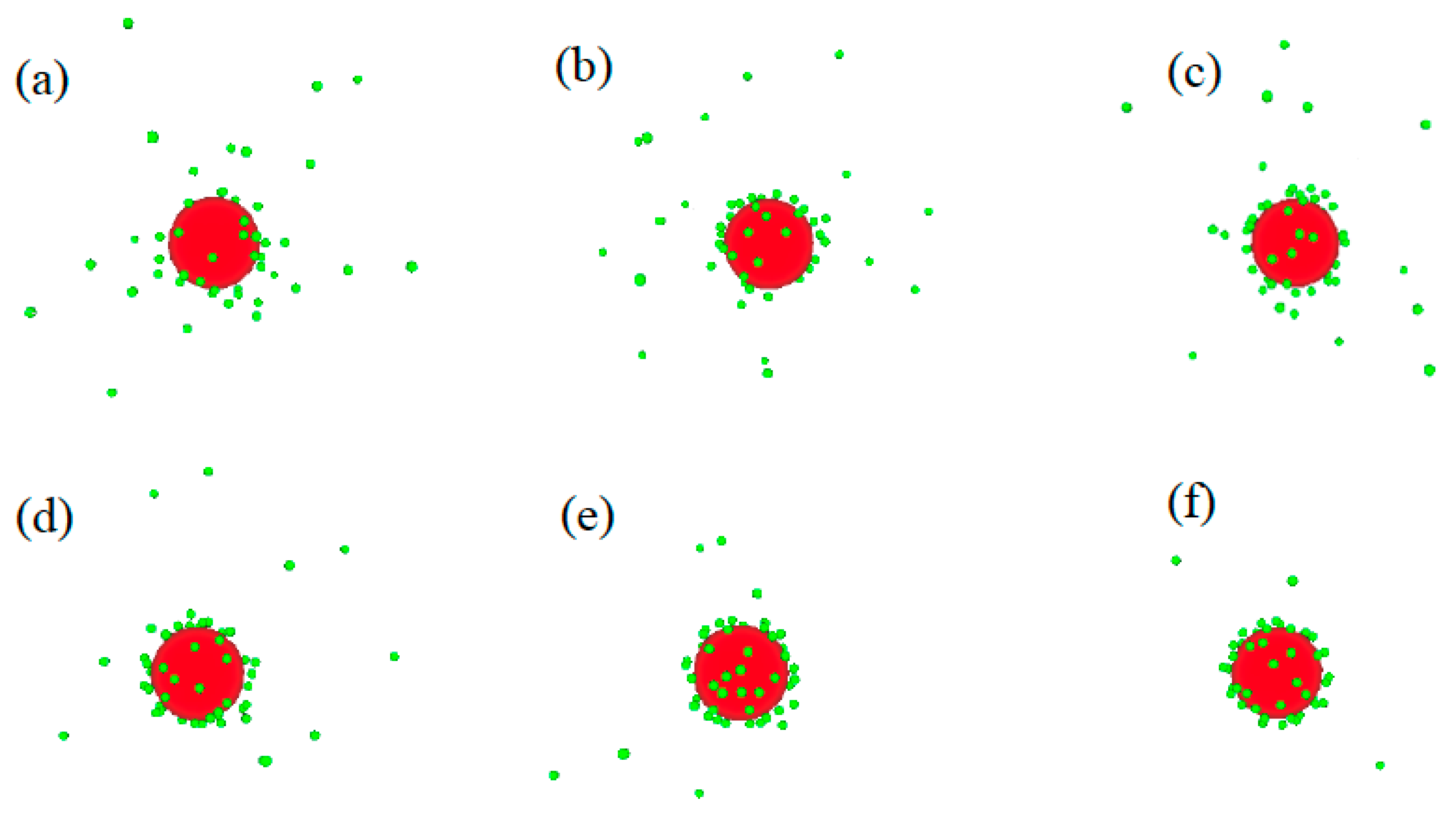

2.1. Systems without Salts

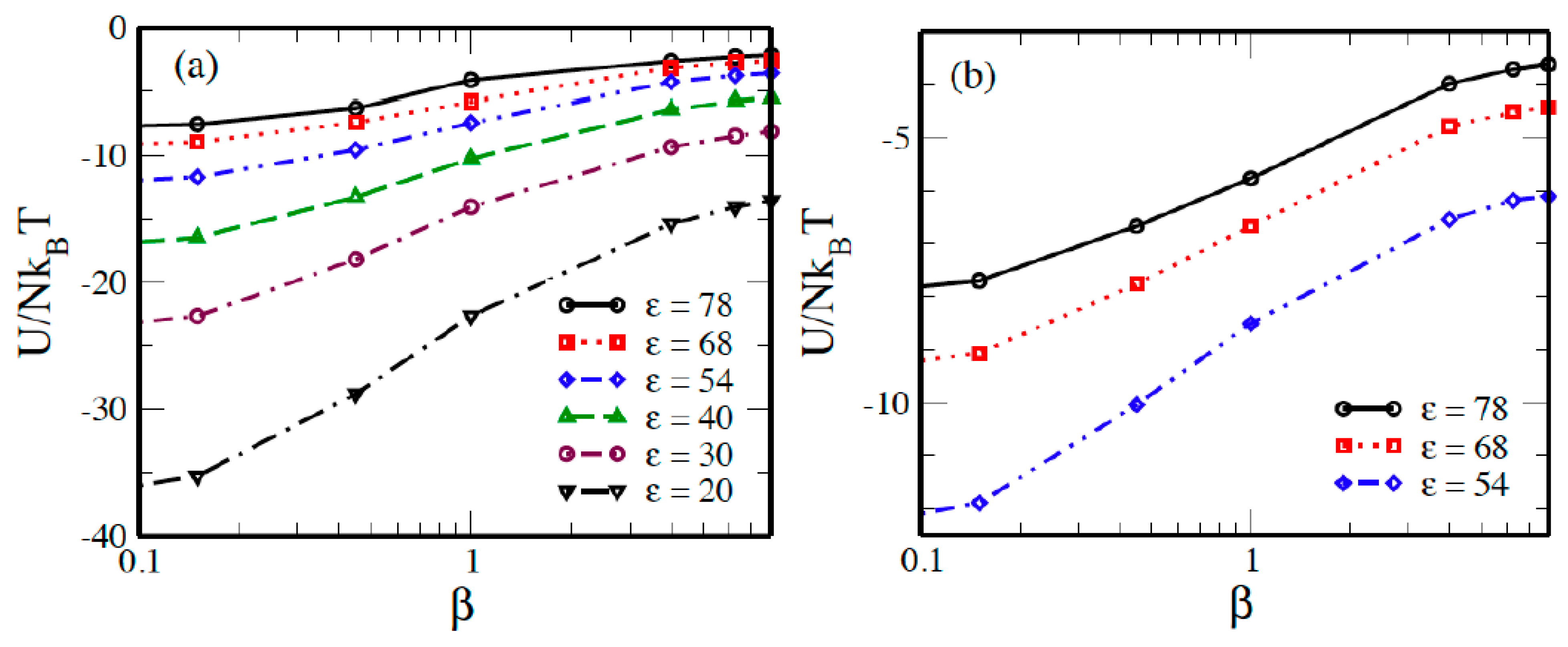

2.2. Systems with Salt

3. Model and Method

3.1. Model

3.2. Method and Simulation Settings

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qamhieh, K.; Linse, P. Effect of Discrete Macroion Charge Distributions in Solutions of Like-Charged Macroions. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 104901–104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzclez-Tovar, E.; Lozada-Cassou, M. The Spherical Double Layer: A Hypernetted Chain Mean Spherical Approximation Calculation for a Model Spherical Colloid Particle. J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 3761–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verway, E.J.; Overbeek, J.T.G. Theory of the Stability of Lyophobic Colloid; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Yiacoumi, S.; Tsouris, C. Monte Carlo Simulations of Electrical Double-Layer Formation in Nanopores. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 8499–8507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K.; Amleh, M.; Khaleel, M. Effect of Discrete Macroion Charge Distributions on Electric Double Layer of a Spherical Macroion. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2013, 34, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulavchenko, A.I.; Batishchev, A.F.; Batishcheva, E.K.; Torgov, V.G. Modeling of the Electrostatic Interaction of Ions in Dry, Isolated Micelles of AOT by the Method of Direct Optimization. ACS Publ. 2002, 106, 6381–6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hesse, M.; Wang, M. Dispersion of Charged Solute in Charged Micro-and Nanochannel with Reversible Sorption. Electrophoresis 2019, 40, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.X.; Guan, W.; Weiner, B.; Reed, M.A. Direct Observation of Charge Inversion in Divalent Nanofluidic Devices. Nano. Lett. 2015, 15, 5046–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Ma, W.; Zhu, D.B.; Guo, W.; Xia, J.; Nie, F.-Q.; Xue, J.; Song, Y.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Energy Harvesting with Single-ion-selective Nanopores: A Concentration-gradient-driven Nanofluidic Power Source. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K.; Nylander, T.; Black, C.F.; Attard, G.S.; Dias, R.S.; Ainalem, M.L. Complexes Formed between DNA and Poly(Amido Amine) Dendrimers of Different Generations-Modelling DNA Wrapping and Penetration. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 13112–13122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K.; Khaleel, A.A. Analytical Model Study of Complexation of Dendrimer as an Ion Penetrable Sphere with DNA. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 442, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamhieh, K.; Nylander, T.; Ainalem, M.L. Analytical Model Study of Dendrimer/DNA Complexes. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1720–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobaskin, V.; Qamhieh, K. Effective Macroion Charge and Stability of Highly Asymmetric Electrolytes at Various Salt Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 8022–8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Qiang, X.; Dong, H.L.; Huo, J.; Tan, Z.J. Multivalent Ion-Mediated Attraction between Like-Charged Colloidal Particles: Nonmonotonic Dependence on the Particle Charge. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9876–9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linse, P.; Lobaskin, V. Electrostatic Attraction and Phase Separation in Solutions of Like-Charged Colloidal Particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 4208–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shklovskii, B.I. Wigner Crystal Model of Counterion Induced Bundle Formation of Rodlike Polyelectrolytes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 3268–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linse, P. Mean Force between Like-Charged Macroions at High Electrostatic Coupling. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 13449–13467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, F.; Malmsten, M.; Linse, P. Protein-Polyelectrolyte Cluster Formation and Redissolution: A Monte Carlo Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 3140–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skepö, M.; Linse, P. Complexation, Phase Separation, and Redissolution in Polyelectrolyte-Macroion Solutions. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Molina, A.; Quesada-Pérez, M.; Galisteo-González, F.; Hidalgo-Alvarez, R. Probing Charge Inversion in Model Colloids: Electrolyte Mixtures of Multi-and Monovalent Counterions. J. Phys. Condence. Matter 2003, 15, S3475–S3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, R.; Holm, C.; Kremer, K. Effect of Colloidal Charge Discretization in the Primitive Model. Eur. Phys. J. E 2001, 4, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besteman, K.; Zevenbergen, M.A.G.; Lemay, S.G. Charge Inversion by Multivalent Ions: Dependence on Dielectric Constant and Surface-Charge Density. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft. Matter Phys. 2005, 72, 061501–061509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-García, G.I.; González-Tovar, E.; Lozada-Cassou, M.; Guevara-Rodríguez, F.D.J. The Electrical Double Layer for a Fully Asymmetric Electrolyte around a Spherical Colloid: An Integral Equation Study. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 034703–034723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwer, C.; Kenndler, E. Electrophoresis in Fused-Silica Capillaries: The Influence of Organic Solvents on the Electroosmotic Velocity and the ζ Potential. Anal. Chem. 1991, 63, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, A.; Levin, Y. Smoluchowski Equation and the Colloidal Charge Reversal. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 054902–054906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patila, S.; Sandberg, A.; Heckert, E.; Self, W.; Sea, S. Protein adsorption and cellular uptake of cerium oxide nanoparticles as a function of zeta potential. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4600–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Tsai, T.H.; Huang, Z.R.; Fang, J.Y. Effects of lipophilic emulsifiers on the oral administration of lovastatin from nanostructured lipid carriers: Physicochemical characterization and pharmacokinetics. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2010, 74, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagigit, T.; Abdulrazik, M.; Orucov, F.; Valamanesh, F.; Lambert, M.; Lambert, G.; Behar-Cohen, F.; Benita, S. Topical and intravitreous administration of cationic nanoemulsions to deliver antisense oligonucleotides directed towards VEGF KDR receptors to the eye. J. Control. Release 2010, 145, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wissinga, S.A.; Kayserb, O.; Muller, R.H. Solid lipid nanoparticles for parenteral drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2004, 56, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, F.; Ostacolo, L.; Mazzaglia, A.; Villari, V.; Zaccaria, D.; Sciortino, M.T. The intracellular effects of nonionic amphiphilic cyclodextrin nanoparticles in the delivery of anticancer drugs. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzina, I.; Bloomfield, V.A. Macroion Attraction Due to Electrostatic Correlation between Screening Counterions. 1. Mobile Surface-Adsorbed Ions and Diffuse Ion Cloud. Artic. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 9977–9989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobaskin, V.; Linse, P. Simulation of an Asymmetric Electrolyte with Charge Asymmetry 60:1 Using Hard-Sphere and Soft-Sphere Models. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 4300–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Solvent | Water | (75% Water, 25% Ethanol) | Methyl Alcohol | Glycerin | Methanol | Ethanol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dielectric constant () | 78 | 68 | 54 | 40 | 30 | 20 |

| (Å) | 7.1 | 8.2 | 10.4 | 14.0 | 18.7 | 28.0 |

| 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 7.8 | 10.4 | 15.6 | |

| 8.9 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 16.8 | 22.4 | 33.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qamhieh, K. Effect of Dielectric Constant on the Zeta Potential of Spherical Electric Double Layers. Molecules 2024, 29, 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112484

Qamhieh K. Effect of Dielectric Constant on the Zeta Potential of Spherical Electric Double Layers. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112484

Chicago/Turabian StyleQamhieh, Khawla. 2024. "Effect of Dielectric Constant on the Zeta Potential of Spherical Electric Double Layers" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112484

APA StyleQamhieh, K. (2024). Effect of Dielectric Constant on the Zeta Potential of Spherical Electric Double Layers. Molecules, 29(11), 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112484