Abstract

Many of the medicinally active molecules in the flavonoid class of phytochemicals are being researched for their potential antiviral activity against various DNA and RNA viruses. Quercetin is a flavonoid that can be found in a variety of foods, including fruits and vegetables. It has been reported to be effective against a variety of viruses. This review, therefore, deciphered the mechanistic of how Quercetin works against some of the deadliest viruses, such as influenza A, Hepatitis C, Dengue type 2 and Ebola virus, which cause frequent outbreaks worldwide and result in significant morbidity and mortality in humans through epidemics or pandemics. All those have an alarming impact on both human health and the global and national economies. The review extended computing the Quercetin-contained natural recourse and its modes of action in different experimental approaches leading to antiviral actions. The gap in effective treatment emphasizes the necessity of a search for new effective antiviral compounds. Quercetin shows potential antiviral activity and inhibits it by targeting viral infections at multiple stages. The suppression of viral neuraminidase, proteases and DNA/RNA polymerases and the alteration of many viral proteins as well as their immunomodulation are the main molecular mechanisms of Quercetin’s antiviral activities. Nonetheless, the huge potential of Quercetin and its extensive use is inadequately approached as a therapeutic for emerging and re-emerging viral infections. Therefore, this review enumerated the food-functioned Quercetin source, the modes of action of Quercetin for antiviral effects and made insights on the mechanism-based antiviral action of Quercetin.

Keywords:

quercetin; antiviral action; flavonoid; SARS-CoV-2; Dengue; Ebola; influenza; hepatitis C virus; mechanisms; medicinal plant 1. Introduction

Viral infection has now become the biggest global concern for healthcare professionals because of the increasing incidence of morbidity and mortality. Viral infectious illnesses are becoming a severe hazard to human health in both developing and developed countries [1], killing 1 million people each year. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis virus subtypes A, B, and C (HAV, HBV, and HCV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), influenza virus, Dengue virus, Ebola virus, and other viruses such as monkeypox/mpox virus have been affecting human health for decades [2]. Along with these pre-existing viruses, corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) became a global burden beginning in 2019. Coronavirus infection, commonly known as “new coronavirus disease” (COVID-19), is characterized by severe acute respiratory illness with a significant mortality rate [3]. Unfortunately, many of the viral diseases are not yet curable, such as corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis virus, human papillomavirus, and others. The emergence of new diseases, such as the Zika virus, Chikungunya virus, and Dengue virus, is creating new health challenges and significant concerns in healthcare.

The pathogenesis of viral infections has also been reported to provoke various types of complications that target different organs and the immune system and sometimes can even promote tumor progression. Due to the lack of safe, as well as effective, antiviral drugs against these viruses, the substantial health burden with direct and indirect costs, including hospitalization and loss of productivity [4], is increasing. Additionally, the toxicity and ineffectiveness of synthetic antiviral drug responses to resistant strains have fueled the hunt for effective and alternative treatment options, such as plant-derived antiviral medicinal molecules. Furthermore, vaccines and antiviral drugs are frequently and prohibitively expensive, making them inaccessible to most of the world’s population. As a result, the current review, as part of an effort to find natural treatments for viral infections, attempts to investigate the possibility, probable source, and mechanistic insights of a plant-based natural flavonoid Quercetin against SARS-CoV-2, HIV, and HBV, Dengue and Ebola virus.

Plant-based natural molecules are producing huge interest for the stakeholders, including the researchers, due to their effectiveness, less or no harmful effects, affordability and greater compliance of patience. Therefore, natural biometabolites are thought to be the best option for producing new medications. During the last few years, many researchers have been attempting to develop novel antiviral medications [5]. Natural compounds have grown in popularity in recent decades due to their diverse biological roles and direct application as treatments [5,6]. Quercetin is a distinct flavonoid component renowned for its antiviral effects. It has fewer or no negative effects than synthetic drugs and could be a viable therapeutic option for certain viral infections [6].

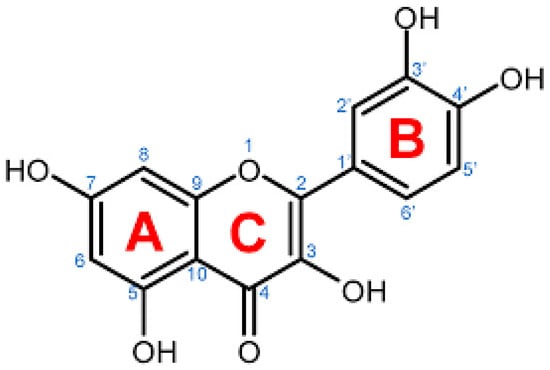

Quercetin (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one) (Figure 1), the major representative of the flavonoid subclass of flavonols [7], is derived from the Latin word “Quercetum,” meaning “Oak Forest” [8]. Quercetin, yellow in appearance, is availably found in a variety of vegetables and fruits, including lovage, capers, berries, cilantro, dill, apples, and onions [9]. Quercetin is entirely soluble in lipids and alcohol, slightly soluble in hot water but insoluble in cold water [8].

Figure 1.

Chemical illustration of Quercetin taken from pubChem.

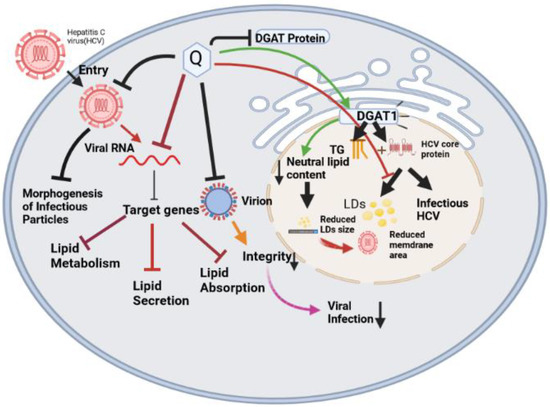

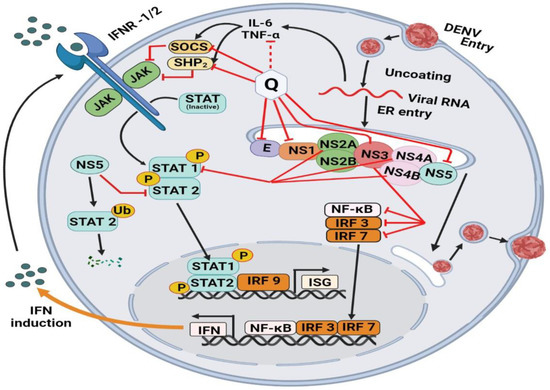

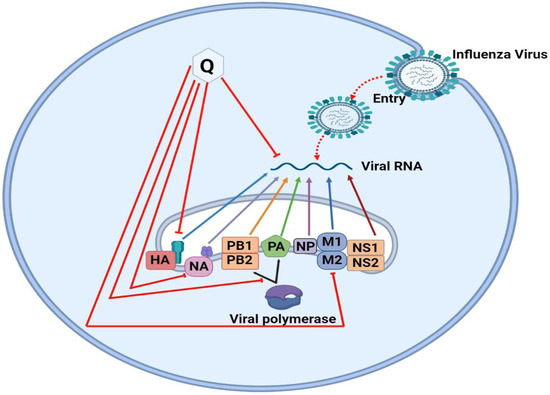

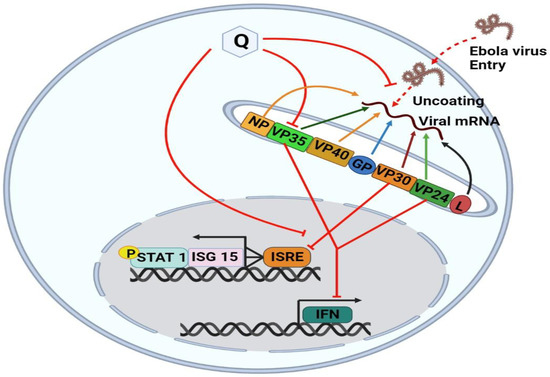

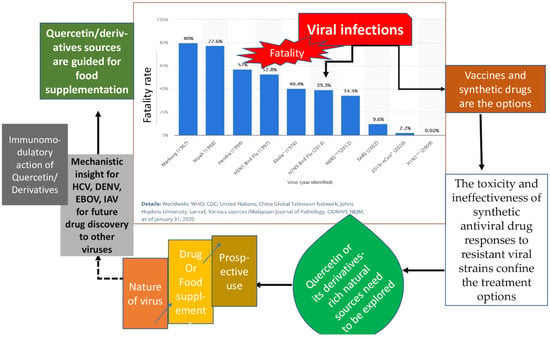

Quercetin is an active medicinal drug that has antiviral activity and suppresses viruses by targeting viral infections at various stages. Several studies have emphasized the potential utility of Quercetin as an antiviral due to its capacity to suppress the early phases of virus infection, interact with viral replication proteases, and diminish infection-induced inflammation [10]. Quercetin may also be effective in combination with other medications to potentially boost their efficacy or interact synergistically with them to lessen their side effects and associated toxicity. The main molecular mechanisms of Quercetin’s antiviral effects are the inhibition of viral neuraminidase, proteases, DNA/RNA polymerases, and the modification of several viral proteins. Quercetin has been reported to have an antiviral effect against several viruses, including the hepatitis C virus (HCV) [11], the Mayaro virus [12], the influenza A virus (IAV) [13], the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) [14,15]. It has also been documented to suppress HCV by binding to and inactivating the viral NS3 protease [16]. It is literally cited to inhibit viral RNA polymerase, preventing DENV-2 replication [17] and suppressing Ebola virus infection via VP24 Interferon-Inhibitory Function [18]. Our recent studies, using computer models, have shown the effectiveness of Quercetin against the Hepatitis C virus, Dengue type 2 virus, Ebola virus, and Influenza A. To discover the optimal binding sites between Quercetin and PubChem-based receptors, molecular docking research was conducted using the web program PockDrug. A strong binding affinity of Quercetin was demonstrated for the HCV NS5A protein (docking score of—6.268 kcal/mol), the DENV-2 NS5 protein (docking score of—5.393 kcal/mol), the EBOV VP35 protein (docking score of—4.524 kcal/mol) and the IAV NP protein (docking score of—6.954 kcal/mol). The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING), the search tool for interactions of chemicals (STITCH), Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA,) and the Cytoscape plugin cytoHubba network-pharmacological tools were used to confirm function-specific, gene-compound interactions demonstrating the 38 genes that interacted with Quercetin. The top interconnected nodes in the protein–protein network was AKT1 (Serine/threonine protein kinase), Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase SRC (SRC), Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), matrix-metalloproteinase (MMP9), kinase insert domain receptor (KDR), MMP2, insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R), protein tyrosine kinase 2 (PTK2), breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) and MET [19]. However, the differences in their mechanistic insights, use of Quercetin-rich plants for future antiviral drug discovery and immunomodulatory actions of Quercetin to defend against viral infections are yet to be fully enumerated. Therefore, this review discusses the mechanistic insights of Quercetin against influenza A, Hepatitis C, Dengue type-2, and Ebola virus; the direction of using the observed effects (Figure 2) for advanced antiviral drug discovery; and the association of antiviral actions with immunomodulatory performances to further suggest the therapeutic prospects of Quercetin/its derivatives as antiviral agent/food supplements.

Figure 2.

Schematic design aiming the approach and objective of this review.

2. Methodology and Resources

An extensive literature search was conducted to gather all relevant information. Publicly accessible databases and primary sources, including CNKI, PubMed, SciFinder, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect were searched. Many relevant published articles were critically reviewed. All figures were drawn with MS PowerPoint and drawing instruments. The keywords flavonoids, Quercetin, antiviral compounds, phytocompounds for antiviral action, and antiviral mechanism of natural compounds were chosen for the comprehensive search of materials.

3. Research Question and Hypothesis

Many plant-based flavonoids are used as antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antiaging agents. Several different mechanisms are also proposed for how those functions are achieved by Quercetin. Quercetin is also used as a reference agent in some of the in vitro radical scavenging activities eventually leading to showing antioxidant effects. Antioxidant agents have been reported to be effective as antiviral in some of the in vivo and cellular studies. Thus, the antiviral action of the well-known strong antioxidant agent Quercetin is inevitable to be resurgenced for its greater therapeutic benefit. Quercetin is a polyphenolic that belongs to the flavonol class of flavonoids found widely among vegetables and fruits and is a regular component of a normal diet, which is not found in the human body [8]. This biological function of Quercetin is thought to be contributed by the pentahydroxy flavone with five hydroxy groups at positions 3, 3’, 4’, 5, and 7 [20]. It is a Quercetin-7-olate conjugate acid. Glycosides and ethers are the most common groups of Quercetin derivatives, and sulfate and phenyl substituents are the less common [20]. Rutin (Quercetin-3rutinoside) is the most common source of Quercetin [21]. As a nutritional supplement, Quercetin is well-tolerated. Quercetin has shown many pharmacological activities, which include anti-inflammatory [22], antiproliferative [23], antioxidative [24], antibacterial [25], anticancer [26], neuroprotective, hepatoprotective [27,28], and antiviral [29,30,31] activities. Quercetin also increases mitochondrial biogenesis while inhibiting platelet aggregation, capillary permeability, and lipid peroxidation [8]. The current review aims to understand the mechanistic insights of four different types of viruses and the role of Quercetin in protecting against their infections; natural sources of Quercetin and its derivative; and the immunomodulatory contribution of Quercetin in controlling viral infections.

4. Natural Sources of Quercetin and Its Isolation from Plants

Quercetin is one of the most consumed and important bioflavonoid components and is widely found in different varieties of fruits and vegetables. Plant species, growing conditions, harvest conditions, and storage methods can influence the polyphenolic composition of fruits and vegetables. Quercetin is found in abundance in onions, apples, and wine. According to several studies, Quercetin is also found in tea, pepper, coriander, fennel, radish, and dill [32]. More than 20 plants species produce Quercetin: Foeniculum vulgare, Curcuma domestica valeton, Santalum album, Cuscuta reflexa, Withania somnifera, Emblica officinalis, Mangifera indica, Daucus carota, Momordica charantia, Ocimum sanctum, Psoralea corylifolia, Swertia chirayita, Solanum nigrum, and Glycyrrhiza glabra, Morua alba, Camellia sinensis [33], Allium fistulosum, A. cepa, Calamus scipionum, Moringa oleifera, Centella asiatica, Hypericum hircinum, H. perforatum, Apium graveolens, Brassica oleracea var. Italica, B. oleracea var. sabellica, Coriandrum sativum, Lactuca sativa, Nasturtium officinale, Asparagus officinalis, Capparis spinosa, Prunus domestica, P. avium, Malus domestica, Vaccinium oxycoccus, and Solanum lycopersicum [9]. Quercetin is available in capsule and powder form as a dietary supplement. The plasma Quercetin concentration rises when Quercetin is consumed in the form of foods or supplements (Table 1). As a result, everyday consumption of Quercetin-rich foods increases Quercetin bioavailability and contributes to the prevention of lifestyle-related disorders [32].

Quercetin was isolated from a fractionated extract of Rubus fruticosus by using an optimized column in HPLC and increasing its concentration by using a nanofiltration membrane [34]. Extraction of Quercetin from different plant sources can be followed by effective sample preparation techniques known as the sea sand disruption method (SSDM). The SSDM is used due to its recovery efficiency [35]. During the isolation of Quercetin and its derivatives in plants’ source, SSDM is used to eliminate errors in the study [36]. Flavonoids are isolated from the crude extract of plants by using various organic solutions followed by HPLC analysis, which is further characterized by FTIR, NMR, and mass spectroscopy [37]. Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside was isolated from P. thonningii leaves by using different organic solvents [38]. According to one study, dihydroQuercetin, one of the Quercetin derivates, was isolated from Larix gmelinii using ultrasound-assisted and microwave-assisted alternate digestion methods because they required less extraction time, less energy, and were more cost-effective than conventional solvent extraction methods [39]. Another derivative known as Isorhamnetin was isolated from the crude extract of Stigma maydis through two-stage high-speed countercurrent chromatography processes, where two-phase solvent systems composed of n-hexane-ethyl acetate-methanol-water are used at volume ratios of 5:5:5:5 and 5:5:6:4 to ensure the purity [40].

Table 1.

Quercetin and its derivatives from different plant sources and their biological effects in various experimental models.

Table 1.

Quercetin and its derivatives from different plant sources and their biological effects in various experimental models.

| Phytochemical | Plant Name | Family | Plant Parts | Virus Target | Cell | Bioassay | Viral Step or MOA | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin-3-o-α-L-rhamnopyranoside (Q3R) | Rapanea melanophloeos | Myrsinaceae | Whole plant | IAV | MDCK cell | In vitro | Inhibit viral entry and virus replication | [41] |

| Quercetin 3-glucoside | Dianthus superbus L. | Caryophyllaceae | Whole plant | IAV | MDCK cell | In vitro and in silico | Inhibit viral replication | [42] |

| Quercitrin (Quercetin-3-L-rhamnoside) | Houttuynia cordata Thunb. | Saururaceae | Leaf (Aerial parts) | IAV (Anti-influenza A/WS/33 virus) | Mammalian kidney (BHK) | In vitro | Inhibit replication in the initial stage of virus infection by indirect interaction with virus particles | [43] |

| Rutin (Quercetin-3-rutinoside) | Prunus domestica | Rosaceae | Fruit | HCV | Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells Huh 7 and Huh 7.5 | In vitro and ex vivo | Inhibit the early stage of viral entry | [44] |

| Quercetin | Psidium guajava | Myrtaceae | Bark | DENV | Epithelial VERO cells (Cercopithecus aethiops) | In vitro and in silico | Directly inhibit the viral NS3 protein and could interrupt virus entry by inhibiting fusion | [45] |

| Quercetin | Embelia ribes | Myrsinaceae | Seeds | HCV | Huh-7 cells | In vitro | Inhibit NS3 protease activity and HCV replication. | [16] |

| Quercetin 7-rhamnoside | Houttuynia cordata | Saururaceae | Aerial Parts | Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV CV 777) | Vero (african green monkey kidney cell line; ATCC CCR-81) ST (pig testis cell line; ATCC CRL-1746) | In vitro and In vivo | Inhibit at an early stage of viral replication after infection | [29] |

| Quercetin and its glycoside derivatives | Bauhinia longifolia (Bong.) | Fabaceae | Leaves | Mayaro viruses (ATCC VR-66, lineage TR 4675) | Vero cells (African green monkey kidney, ATCC CCL-81) | In vitro | glycosilation re duces the antiviral activity of Quercetin against | [12] |

| DihydroQuercetin (DHQ) | Larix sibirica (larch wood) | Pinaceae | Wood | Coxsackie virus B4 Powers strain | Vero cells Inbred, female mice | In vivo | Decrease the replication of viral protein by reducing ROS generation | [46] |

| Quercetin-7-o-glucoside | Dianthus superbus | Caryophyllaceae | Leaves | Influenz viruses A/Vic/3/75 (H3N2, VR-822), A/PR/8/34 (H1N1, VR-1469), B/Maryland/1/59 (VR-296) and B/Lee/40 (VR-1535D) | Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cell | In Vitro | Inhibit influenza viral RNA polymerase PB2 | [24] |

| Quercetin and Isoquercitrin | Houttuynia cordata | Saururaceae | Whole plant | Herpes simplex virus (HSV) | African green monkey kidney cells (Vero, ATCC CCL-81) and human epithelial carcinoma cells | In vitro | Quercetin and isoquercitrin inhibit NF-κB activation in HSV viral replication | [47] |

| Kaempferol | Rhodioila rosea | Crassulaceae | Roots | The influenza strains A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (ATCC VR-1469) | Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were obtained | In vitro | Inhibit viral replication by blocking neuraminidases | [48] |

| Myricetin | Marcetia taxifolia | Melastomataceae | Aerial parts | HIV-1 (HTLV-IIIB/H9) | MT4 cells | In silico | May Bind to NNRTI pocket of NNRTI resistant HIV-1 | [49] |

| Apigein | Gentiana veitchiorum | Gentianaceae | Flower | Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) | BHK-21 cells | In vitro | Block the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) mediate translational activity | [50,51] |

| Quercetin 3-o-β-glucopyranoside | Morus Alba | Moraceae | Leaf | Herpes simplex Virus type 1 | Vero cell line no ATCC CCL-81) | In vitro | Inhibit DNA chair termination | [52] |

| Quercetin 3-o-β-(6”-o-galloyl)-glucopyranoside | Morus Alba | Moraceae | Leaf | Herpes simplex Virus type 1 | Vero cell line no ATCC CCL-81) | In vitro | Inhibit DNA chair termination | [52] |

| Quercetin-3-o-β-L-rhamnopyranosyl | Acacia albdai | Fabaceae | Leaf | Herpes simplex Virus type 1 | Vero cell line no ATCC CCL-81) | In vitro | Inhibit DNA chain termination | [52] |

| Quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside | Acacia albdai | Fabaceae | Leaf | Herpes simplex Virus type 1 | Vero cell line no ATCC CCL-81) | In vitro | Inhibit DNA chain termination | [52] |

| 6-o-methoxy Quercetin-7-o-β-D-glucopyranoside | Centaurea glomerata | Asteraceae | Aerial parts | Herpes simplex Virus type 1 | Vero cell line no ATCC CCL-81) | In vitro | Inhibit DNA chain termination | [52] |

| 4’,6-o-dimethoxy Quercetin-7-o-β-D-glucopyranoside | Centaurea glomerata | Asteraceae | Areal Parts | Herpes simplex Virus type 1 | Vero cell line no ATCC CCL-81) | In vitro | Inhibit DNA chain termination | [52] |

| Quercetin-3-β-o-D-glucoside | Allium cepa | Amaryllidaceae | Root | Ebolaviruses (EBOV-Kikwit-GFP, EBOV Makona, SUDV-Boniface, mouse-adapted EBOV) | Vero E6 cells | In vitro | Block glycoprotein mediated step during viral entry | [53,54] |

| Isorhamnetin | Ginkgo biloba | Ginkgoaceae | Leaf | Influenza A virus Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) | Madin Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells | In vitro and In vivo | Inhibit neuraminidase and hemagglutination, suppress ROS generation and ERK phosphorylation | [55,56] |

| Luteolin | Elsholtzia rugulosa | Lamiaceae | Whole Plant | Influenza viruses A/PR/8/34(H1N1), A/Jinan/15/90(H3N2) and B/ Jiangsu/10/2003 | MDCK cells | In vitro | Inhibit the neuraminidase | [57] |

| Luteolin | Cynodon dactylon | Poaceae | Whole Plant | Chikungunya virus | Vero cells | In vitro | Inhibit intracellular viral replication | [58] |

| Quercetin | Illicium verum | Schisandraceae | Singapore grouper iridovirus (SGIV) | Grouper spleen (GS) cells | In vitro | Interrupt SGIV binding to host cell by blocking membrane receptor on host cell which | [59] | |

| Naringenin | Citrus sinensis | Rutaceae | Fruit | Zika Virus | Human A549 cells | In vitro | Inhibit NS2B-NS3 protease | [60,61] |

| Hesperidin | Citrus sinensis (sweet orange) | Rutaceae | Fruit Peel | SARS-CoV-2 virus | In silico | Binds to main protease and angiotensin converting enzyme 2 | [62] | |

| Hesperidin | Citrus sinensis | Rutaceae | Fruit Peel | Sindbis virus | BHK-2 | In vitro | Inhibitory activity on viral replication | [63,64] |

| Naringenin | Citrus paradisi | Rutaceae | Fruit Peel | Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | Huh7.5.1 human hepatoma cell | In vitro and In vivo | inhibits ApoB lipoprotein reduce secretion of HCV | [65,66] |

| Luteolin | Achyrocline satureioides | Asteraceae | Whole Plant | Influenza virus A/Fort Monmouth/1/1947 (H1N1) | Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells and Vero cells | In vitro | Block absorption to the cell surface or receptor binding site leads to the suppress of the expression of coat protein I | [67,68] |

| Naringenin | Citrus paradisi | Rutaceae | Fruit Peel | Dengue virus (DENV) | Huh7.5 cells | In vitro | Act as antiviral cytokine during DENV replication | [66,69] |

5. Absorption, Metabolism, Distribution, and Excretion of Quercetin

Quercetin is taken as glycosides, with glycosyl groups released during chewing, digestion, and absorption. In humans, only a small percentage of Quercetin is absorbed in the stomach, and the primary site of absorption is the small intestine [70]. Two methods allow Quercetin glycosides to be absorbed in the intestine. One method is lactose polarizing hydrolase (LPH) in the brush border membrane, and another method is the interaction with the sodium-dependent glucose transporter (SGLT1) [33]. The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the absorption of Quercetin by enzymatic hydrolysis. After absorption, the metabolism of Quercetin takes place in various organs, including the small intestine, colon, liver, and kidney. Biotransformation enzymes in the small intestine and liver create methylated, sulfated, and glucuronate forms of Quercetin metabolites due to phase II metabolism [32]. After that, these are released into the bloodstream via the portal vein of the liver. In the small intestine and colon, Quercetin metabolism leads to the generation of phenolic acids. The metabolites of Quercetin are found in human plasma as methylated glucuronide or unmethylated sulfate. The major metabolite of Quercetin, Quercetin-3-o-b-D-glucuronide, is delivered to target tissues via plasma to exert biological activity [32]. Quercetin had a short half-life and rapid clearance in the blood, and its metabolites appeared in the plasma 30 min after ingestion; however, considerable amounts were excreted over 24 h [71]. In comparison to other phytochemicals, Quercetin has a high bioavailability. The bioavailability of Quercetin decreases when consumed as a supplement rather than food. Quercetin is excreted from the human body in the feces and urine, and in high doses, it can be discharged through the lungs. 3-hydroxy phenylacetic acid, hippuric acid, and benzoic acid are the excretory products of Quercetin [32].

6. Major Pharmacological Actions of Quercetin

Flavonoids, particularly Quercetin, which has well-known antioxidant effects, are gaining popularity these days. Quercetin has been identified as a potential anticancer drug with activity both in in vitro and in vivo models. Quercetin is used to inhibit the spread of various cancers, such as lung, prostate, liver, breast, colon, and cervical cancers, by modifying oxidative stress factors and antioxidant enzymes [8]. Because of its chemoprotective action against tumor cell lines through metastasis and apoptosis, Quercetin is thought to be a promising anticancer option [72]. Furthermore, another study revealed the powerful efficiency of combined Quercetin-doxorubicin treatment in maintaining T-cell tumor-specific responses, resulting in better immune responses against breast tumor growth [73]. Antioxidants work against asthma pathogenesis by avoiding oxidative damage through a variety of methods. Quercetin plays a role in scavenging free radicals that can lead to cell death by damaging DNA and cell membranes. In addition, it has been noted that Quercetin decreases the production and release of histamine and other mediators involved in the development of allergic reactions in mast cells, suggesting that it could be effective against asthma [74]. In in vitro and in vivo studies, Quercetin has been shown to protect neurons from oxidative and neurotoxic chemicals, saving the central nervous system from oxidative stress-induced neurodegenerative diseases, especially Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Quercetin has been shown as anti-Alzheimer’s because it improves mitochondrial morphology, improves memory impairments, protects cognitive deficits, and reduces neurodegeneration [32].

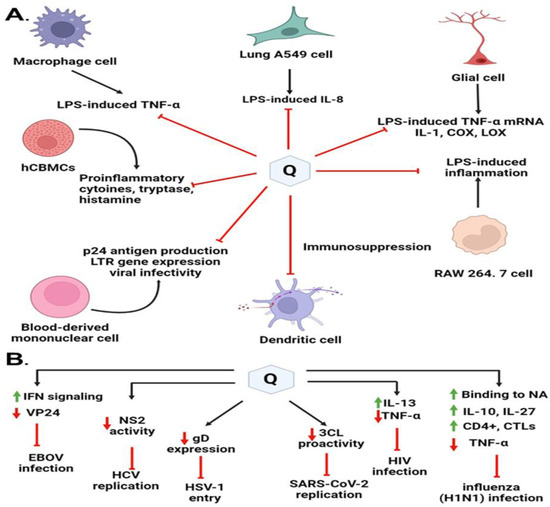

8. Quercetin in Preventing Viral Infection through Immunomodulation

Quercetin functions as a powerful immunomodulatory molecule due to its direct modulatory actions on several immune cells, cytokines, and other immune chemicals, and indirect actions modulated through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant modes [9,134] (Figure 7). Quercetin has been highly recommended as an immunomodulatory antiviral drug in various studies due to its capacity to prevent the first phases of viral infection as an immunosuppressor or immunostimulator. It interacts with proteases required for viral replication and reduces infection-related inflammation. One possibility for reducing the occurrence of infections could be to improve people’s antiviral immune response through a nutritious diet that includes pure Quercetin taken from natural extracts. There are several mechanisms and studies focusing on the immunomodulatory actions of Quercetin on the major human viruses, such as HCV, HSV-1, H1N1, HBV, SARS-CoV2, and HIV-1, summarized in Table 2.

Figure 7.

Immunomodulatory highlights on different antiviral mechanisms of action of Quercetin and its derivates. (A) Quercetin blocks virus entry or virus replication through interaction with viral proteins. (B) Immunomodulatory factors interleukins, tumor necrosis factor, and nonstructural viral proteins regulated by Quercetin play a key role in protecting the viral infections.

Table 2.

Different mechanisms of Quercetin to function as immunomodulatory agent.

During the influenza course, Quercetin was found to affect the state of cytokine production. Quercetin is known to possess mast cell stabilizing, modulating, and regulatory action on immunity and inflammation [137]. Additionally, Quercetin has an immunosuppressive effect on dendritic cell function [138]. It limits LPS-induced inflammation via inhibition of Src- and Syk-mediated phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase (PI3K)-(p85) tyrosine phosphorylation and subsequent Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)/MyD88/PI3K complex formation that limits activation of downstream signaling pathways in RAW 264.7 cells [139]. It can also inhibit the FcεRI-mediated release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, tryptase, and histamine from human umbilical cord blood-derived cultured mast cells (hCBMCs). The fatal consequence of influenza is eminently found to be associated with a massive viral load along with high cytokine storm or hypercytokinemia, which recruits a variety of innate immune cells [125]. TNF-α and IL-27 were tested from two categories of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, respectively. One of the cytokines that was altered was IL-27, which can boost the production of IL-10 by antiviral CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), which can effectively modulate excessive immune response injuries [140]. Quercetin may boost IL-27 synthesis while decreasing TNF production.

Nair et al. (2009) found that Quercetin significantly downregulated p24 antigen production, LTR gene expression, and viral infectivity in a dose-dependent manner in Normal Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells [141]. Quercetin was reported to significantly downregulate the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α with concomitant upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-13 as measured by the gene expression and protein production. They concluded that significant downregulation of TNF-α by Quercetin could probably be attributed to increased levels of IL-13. A higher level of IL-13 is known to inhibit TNF-α production and HIV-1 infection [141]. These findings suggest that in addition to the downregulation of HIV entry co-receptors by Quercetin, differential modulation of pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines expression could be the potential mechanism for the anti-HIV activity of Quercetin.

The antioxidant, anti-allergy, and immunostimulatory effects of Quercetin are achieved by its capacity to inhibit histamine release and thereby antiviral effects by reducing the release of proinflammatory cytokines [142]. As we said earlier, Quercetin can inhibit the secretion of TNFα, which avoids triggering NF-κB [143] pathways and subsequently disrupts the production of IL1β, TNFα, and IL6. Furthermore, Quercetin greatly lowers the production of CCL-2, a key chemokine that governs monocyte and macrophage movement and infiltration throughout the inflammatory process [144]. Quercetin suppresses CXCL8, which induces neutrophil chemoattraction in a concentration-dependent manner, as well as RELA activity and recruitment [145]. All mechanisms mentioned contribute to the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating properties of Quercetin, and the targets mentioned above are important for the infection of SARS-CoV-2 and DENV, especially DENV because the level of IL-1β, TNF, CCL2, CXCL8, and IL-6 would be upregulated after Dengue infection.

Quercetin was identified as the first identified inhibitor of the Ebola virus protein (EBOV VP24) anti-interferon (anti-IFN) function. High EBOV virulence and its potential to suppress the type I interferon (IFN-I) system is a promising novel anti-EBOV therapy approach that identifies the molecules targeting viral protein VP24 which is one of the main virulence determinants blocking the IFN response. Hence, Fanunza et al. (2020) in their experiment showed that Quercetin was able to suppress the VP24 effect on IFN-I signaling inhibition [18]. The mechanism of action lies with the Quercetin’s significant restoring capacity of IFN-I signaling cascade, blocked by VP24, by directly interfering with the VP24 binding to karyopherin-α and thus restoring Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (P-STAT1) nuclear transport and IFN gene transcription [146].

Quercetin has been found to suppress lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) production in macrophages and LPS-induced IL-8 production in lung A549 cells [147]. It has been found to inhibit LPS-induced mRNA levels of TNF-α and interleukin (IL-)1α glial cells. Inflammatory cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) are also reported to be suppressed by Quercetin [148]. Interestingly, recent improvements in the pathophysiologic understanding of COVID-19 revealed that the severity of COVID-19 is strongly associated with cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which is characterized by elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, IL-2, IL-7, and IL-10. TNF-α is often upregulated in acute lung injury, trigger CR, S, and facilitates SARS-CoV-2 interaction with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). As a result, TNF-α inhibitors are thought to be a useful therapeutic strategy for slowing illness progression in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [129,149].

All these studies show how Quercetin and its derivates impact immunomodulatory effects and eventually show a wide spectrum of antiviral activities, and a better understanding of Quercetin’s mechanistic properties could help in the rational design of more potent flavonol-type drugs to defend the emerging and reemerging viral infections.

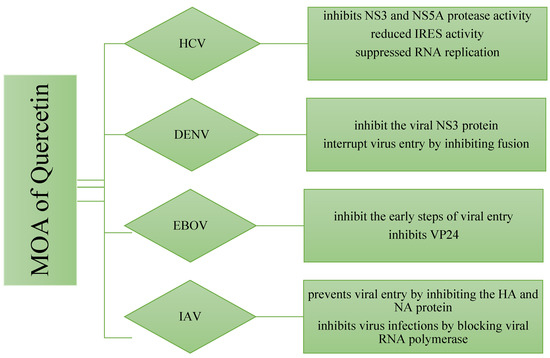

9. Research Insights and Future Use of Quercetin

The molecular mechanisms behind Quercetin’s antiviral effects are the suppression of viral enzyme activity such as neuraminidases, DNA/RNA polymerases, and proteases as well as the immunomodulatory TNF-α (a distinguishing mechanistic diagram presented in Figure 8). As a result, its efficacy in inhibiting certain viral enzymes could be linked to increased immune response, making it a promising antiviral treatment option. Because of the lack of proofreading activity of most viral polymerases, the viral genome regularly mutates. These mutations could hamper the efficacy of antiviral synthetic drugs. By addressing the many signaling pathways, other than those we mentioned, involved in viral infections, the combination of synthetic antiviral medicines and Quercetin would improve therapeutic techniques [6] while dietary use of Quercetin should equally be focused to get the utmost benefit from plant-based natural sources enriched with Quercetin or its derivatives. The dietary consumption of total flavonoids has been estimated to be more than 200 mg/day, whereas the intake of flavonols is about 20 mg/day, with Quercetin accounting for more than 50%, with a daily intake of about 10 mg/day [150]. A Japanese investigation supported these figures since the daily consumption of Quercetin was determined to be 16 mg/day [151]. More advanced research is still demanded to claim the specific-mechanisms oriented development of antiviral drugs or formulation of antiviral supplements of Quercetin or its derivatives to affirm the utmost use of it.

Figure 8.

Differences in the mechanism of action of Quercetin for inhibiting four different types of viruses. The viral strains are denoted as hepatitis C virus (HCV), Dengue virus (DENV), Ebola virus (EBOV), and Influenzae virus (IAV).

Regarding the importance and efficacy of Quercetin against various virus infections, it is gaining attraction among researchers as a potential therapy for recent SARS-CoV-2 (Family: Coronavirus) that has caused a global pandemic situation. There has been little research into the effectiveness of Quercetin on COVID-19. According to one study, Quercetin is the most effective chemical for binding to the virus’s Spike Protein (S) receptor, as well as it binds to the COVID-19 major protease active site more strongly than hydroxyl chloroquine [122]. Climate change, epigenetic factors, abuse of drugs and so many other issues are provoking microorganisms, especially viruses and bacteria to cause multiple types of diseases while viral infections are pondered to be emerging and remerging issues. Therefore, the mechanistic insights of this review will no doubt make a way to suggest the protection of newer viral infections and explore an effective and safer antiviral drug. Nonetheless, Quercetin-and its derivatives-rich food supplements may also be helpful against severe to acute viral infections.

10. Conclusions

Quercetin is mechanically evident to have a wider range of antiviral properties. Unmet therapeutic demand for several viral infections needs to be investigated to affirm the therapeutic benefit of Quercetin. This is because, compared to synthetic medicines, Quercetin exhibits antiviral action without affecting cell viability at higher concentrations and has no negative effects on patients. Several in vivo, in vitro, and in silico investigations also confirmed Quercetin’s effective antiviral properties, which were like those of commercially available antiviral medications. Clinical trials should be included in future studies, so Quercetin and its conjugated products can be used safely. This review includes the most recent developments of Quercetin against some viral diseases, which may highlight the mechanisms of Quercetin on a molecular level. Understanding the mechanisms behind the antiviral effects of Quercetin could lead to new insights into filovirus entry pathways and potential targets for viral treatments. The exact mechanism of Quercetin in virus-host interactions with other viral infections is worthy of future investigation.

Author Contributions

M.A.R.: conceptualization, project administration, and supervision; F.M.S.: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, and Draft preparation; F.Y.N., S.S. and M.A.H.C.: Methodology, Software, Art-Work, and Draft revision; M.A.H.C. and M.S.: Methodology, Data Curation; K.H.H.: Visualization, Validation, and Funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Walailak University, Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data will be available upon request to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

HCV: Hepatitis C virus, DENV: Dengue virus; EBOV: Ebola virus; IAV: Influenzae virus; AD: Alzheimer’s disease, DAA: direct-acting antivirals, GSEA Gene set enrichment analysis. HA-hemagglutinin PD: Parkinson’s disease, Quercetin: Q, JAKs: Janus kinases, STATs: signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins, CHIKV: Chikungunya virus, MPoX: Monkey Pox, STRING: Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins, STITCH: Search tool for interactions of chemicals, SGLT1: Sodium dependent glucose transporter 1; ErbB: Epidermal growth factor receptor family.

References

- Campos, F.S.; de Arruda, L.B.; da Fonseca, F.G. Special Issue “Viral Infections in Developing Countries”. Viruses 2022, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachar, S.C.; Mazumder, K.; Bachar, R.; Aktar, A.; Al Mahtab, M. A Review of Medicinal Plants with Antiviral Activity Available in Bangladesh and Mechanistic Insight Into Their Bioactive Metabolites on SARS-CoV-2, HIV and HBV. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 732891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisondi, P.; Piaserico, S.; Bordin, C.; Alaibac, M.; Girolomoni, G.; Naldi, L. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A clinical update. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2499–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, M.; Berhanu, G.; Desalegn, C.; Kandi, V. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): An Update. Cureus 2020, 12, e7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badshah, S.L.; Faisal, S.; Muhammad, A.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M. Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninfali, P.; Mea, G.; Giorgini, S.; Rocchi, M.; Bacchiocca, M. Antioxidant capacity of vegetables, spices and dressings relevant to nutrition. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Petrillo, A.; Orrù, G.; Fais, A.; Fantini, M.C. Quercetin and its derivates as antiviral potentials: A comprehensive review. Phytother. Res. 2021, 36, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Ikram, M.; Mulla, Z.S.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Taha, A.E.; Algammal, A.M.; Elewa, Y.H.A. The Pharmacological Activity, Biochemical Properties, and Pharmacokinetics of the Major Natural Polyphenolic Flavonoid: Quercetin. Foods 2020, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.V.A.; Arulmoli, R.; Parasuraman, S. Overviews of biological importance of quercetin: A bioactive flavonoid. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2016, 10, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, F.; Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Bertuccioli, A.; Togni, S.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, B.A.; et al. Possible Therapeutic Effects of Adjuvant Quercetin Supplementation Against Early-Stage COVID-19 Infection: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, and Open-Label Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 2359–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatoorian, R.; Arumugaswami, V.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Yeh, G.K.; Maloney, E.M.; Wang, J.; Dasgupta, A.; French, S.W. Divergent antiviral effects of bioflavonoids on the hepatitis C virus life cycle. Virology 2012, 433, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, A.E.; Kuster, R.M.; Yamamoto, K.A.; Salles, T.S.; Campos, R.; de Meneses, M.D.; Ferreira, D. Quercetin and quercetin 3-O-glycosides from Bauhinia longifolia (Bong.) Steud. show anti-Mayaro virus activity. Parasit Vectors 2014, 7, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Narayanan, S.; Chang, K.-O. Inhibition of influenza virus replication by plant-derived isoquercetin. Antivir. Res. 2010, 88, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lani, R.; Hassandarvish, P.; Chiam, C.W.; Moghaddam, E.; Chu, J.J.H.; Rausalu, K.; Merits, A.; Higgs, S.; VanLandingham, D.L.; Abu Bakar, S.; et al. Antiviral activity of silymarin against chikungunya virus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Son, M.; Ryu, E.; Shin, Y.S.; Kim, J.G.; Kang, B.W.; Sung, G.-H.; Cho, H.; Kang, H. Quercetin-induced apoptosis prevents EBV infection. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 12603–12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmetov, L.; Gal-Tanamy, M.; Shapira, A.; Vorobeychik, M.; Giterman-Galam, T.; Sathiyamoorthy, P.; Golan-Goldhirsh, A.; Benhar, I.; Zemel, R. Suppression of hepatitis C virus by the flavonoid quercetin is mediated by inhibition of NS3 protease activity. J. Viral. Hepat. 2012, 19, e81–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, K.; Teoh, B.-T.; Sam, S.-S.; Wong, P.-F.; Mustafa, M.R.; AbuBakar, S. Antiviral activity of four types of bioflavonoid against dengue virus type-2. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanunza, E.; Iampietro, M.; Distinto, S.; Corona, A.; Quartu, M.; Maccioni, E.; Horvat, B.; Tramontano, E. Quercetin Blocks Ebola Virus Infection by Counteracting the VP24 Interferon-Inhibitory Function. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Shorobi, F.M.; Uddin, N.; Saha, S.; Hossain, A. Quercetin attenuates viral infections by interacting with target proteins and linked genes in chemicobiological models. Silico Pharmacol. 2022, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.; Sahu, S.; Saha, S.; Bahadur, S.; Bhardwaj, S. Review on quercetin and their beneficial properties. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 7, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, K. Flavonols and flavones in food plants: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1976, 11, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F.; Leu, Y.-L.; Al-Suwayeh, S.A.; Ku, M.-C.; Hwang, T.-L.; Fang, J.-Y. Anti-inflammatory activity and percutaneous absorption of quercetin and its polymethoxylated compound and glycosides: The relationships to chemical structures. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 47, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, L.; Fernandes, I.; González-Manzano, S.; de Freitas, V.; Mateus, N.; Santos-Buelga, C. Anti-proliferative effects of quercetin and catechin metabolites. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansukh, E.; Kazibwe, Z.; Pandurangan, M.; Judy, G.; Kim, D.H. Probing the impact of quercetin-7-O-glucoside on influenza virus replication influence. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, Z. Quercetin in a lotus leaves extract may be responsible for antibacterial activity. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2008, 31, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atashpour, S.; Fouladdel, S.; Movahhed, T.K.; Barzegar, E.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Ostad, S.N.; Azizi, E. Quercetin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in CD133+ cancer stem cells of human colorectal HT29 cancer cell line and enhances anticancer effects of doxorubicin. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2015, 18, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajas, F. Life or death: Neuroprotective and anticancer effects of quercetin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.-Z.; Liu, Y.-H.; Yu, B.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Zang, J.-N.; Yu, C.-H. Dietary quercetin ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis induced by a high-fat diet in gerbils. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 52, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Song, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Kwon, D.H. Inhibitory effects of quercetin 3-rhamnoside on influenza A virus replication. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 37, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, O.K.; Chung, S.-J.; Claycombe, K.J.; Song, W.O. Serum C-Reactive Protein Concentrations Are Inversely Associated with Dietary Flavonoid Intake in U.S. Adults. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrbod, P.; Ebrahimi, S.N.; Fotouhi, F.; Eskandari, F.; Eloff, J.N.; McGaw, L.J.; Fasina, F.O. Experimental validation and computational modeling of anti-influenza effects of quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside from indigenous south African medicinal plant Rapanea melanophloeos. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulusoy, H.G.; Sanlier, N. A minireview of quercetin: From its metabolism to possible mechanisms of its biological activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 3290–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakya, A.; Correspondence, A. Medicinal plants: Future source of new drugs. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2016, 4, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, M.; Shah, A.B.; Naz, S.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A.; Mahmood, H.M. Isolation of Quercetin from Rubus fruticosus, Their Concentration through NF/RO Membranes, and Recovery through Carbon Nanocomposite. A Pilot Plant Study. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8216435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wianowska, D. Application of Sea Sand Disruption Method for HPLC Determination of Quercetin in Plants. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2015, 38, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wianowska, D.; Dawidowicz, A.L.; Bernacik, K.; Typek, R. Determining the true content of quercetin and its derivatives in plants employing SSDM and LC–MS analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathi, V.S.; Saravanan, D.; Santhakumar, K. Isolation of quercetin from the methanolic extract of Lagerstroemia speciosa by HPLC technique, its cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells and photocatalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 171, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsague, R.K.T.; Kenmogne, S.B.; Tchienou, G.E.D.; Parra, K.; Ngassoum, M.B. Sequential extraction of quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside from Piliostigma thonningii Schum. leaves using microwave technology. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, X.; Ji, H.; Deng, J.; Lu, P.; Jiang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; et al. Quercetin synergistically reactivates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 latency by activating nuclear factor-κB. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 17, 2501–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wei, Y.; Ito, Y. Preparative Isolation of Isorhamnetin from Stigma Maydis using High Speed Countercurrent Chromatography. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2009, 32, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrbod, P.; Abdalla, M.A.; Fotouhi, F.; Heidarzadeh, M.; Aro, A.O.; Eloff, J.N.; McGaw, L.J.; Fasina, F.O. Immunomodulatory properties of quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside from Rapanea melanophloeos against influenza a virus. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nile, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Nile, A.; Park, G.S.; Gansukh, E.; Kai, G. Probing the effect of quercetin 3-glucoside from Dianthus superbus L against influenza virus infection- In vitro and in silico biochemical and toxicological screening. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 135, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiow, K.; Phoon, M.; Putti, T.; Tan, B.K.; Chow, V.T. Evaluation of antiviral activities of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. extract, quercetin, quercetrin and cinanserin on murine coronavirus and dengue virus infection. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, M.; Kamra, M.; Mullick, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Das, S.; Karande, A.A. Identification of a flavonoid isolated from plum (Prunus domestica) as a potent inhibitor of Hepatitis C virus entry. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Correa, A.I.; Quintero-Gil, D.C.; Diaz-Castillo, F.; Quiñones, W.; Robledo, S.M.; Martinez-Gutierrez, M. In vitro and in silico anti-dengue activity of compounds obtained from Psidium guajava through bioprospecting. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galochkina, A.V.; Anikin, V.B.; Babkin, V.A.; Ostrouhova, L.A.; Zarubaev, V.V. Virus-inhibiting activity of dihydroquercetin, a flavonoid from Larix sibirica, against coxsackievirus B4 in a model of viral pancreatitis. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.-Y.; Ho, B.-C.; Lee, S.-Y.; Chang, S.-Y.; Kao, C.-L.; Lee, S.-S.; Lee, C.-N. Houttuynia cordata Targets the Beginning Stage of Herpes Simplex Virus Infection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.J.; Ryu, Y.B.; Park, S.-J.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, H.-J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, K.H.; Rho, M.-C.; Lee, W.S. Neuraminidase inhibitory activities of flavonols isolated from Rhodiola rosea roots and their in vitro anti-influenza viral activities. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6816–6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, J.T.; Suárez, A.I.; Serrano, M.L.; Baptista, J.; Pujol, F.H.; Rangel, H.R. The role of the glycosyl moiety of myricetin derivatives in anti-HIV-1 activity in vitro. AIDS Res. Ther. 2017, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, R.; Xu, M. Apigenin, flavonoid component isolated from Gentiana veitchiorum flower suppresses the oxidative stress through LDLR-LCAT signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Fan, W.; Qian, P.; Zhang, D.; Wei, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, X. Apigenin Restricts FMDV Infection and Inhibits Viral IRES Driven Translational Activity. Viruses 2015, 7, 1613–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Toumy, S.A.; Salib, J.Y.; El Kashak, W.A.; Marty, C.; Bedoux, G.; Bourgougnon, N. Antiviral effect of polyphenol rich plant extracts on herpes simplex virus type 1. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2018, 7, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Kroeker, A.; He, S.; Kozak, R.; Audet, J.; Mbikay, M.; Chrétien, M. Prophylactic Efficacy of Quercetin 3-β- O-d-Glucoside against Ebola Virus Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5182–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quecan, B.X.V.; Santos, J.T.C.; Rivera, M.L.C.; Hassimotto, N.M.A.; Almeida, F.A.; Pinto, U.M. Effect of Quercetin Rich Onion Extracts on Bacterial Quorum Sensing. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, P.; Dhyani, P.; Bhatt, I.D.; Pandey, A. Ginkgo biloba flavonoid glycosides in antimicrobial perspective with reference to extraction method. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2019, 9, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayem, A.A.; Choi, H.Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Cho, S.-G. Antiviral Effect of Methylated Flavonol Isorhamnetin against Influenza. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Shen, L.; Huang, S.; Tang, J.; Duan, J.; Fang, F.; Huang, Y.; Chang, H.; et al. Computational screen and experimental validation of anti-influenza effects of quercetin and chlorogenic acid from traditional Chinese medicine. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.S.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Vincent, S.; Murugan, S.B.; Giridaran, B.; Dinesh, S.; Gunasekaran, P.; Krishnasamy, K.; Sathishkumar, R. Anti—Chikungunya activity of luteolin and apigenin rich fraction from Cynodon dactylon. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2015, 8, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.-L.; Liu, B.; Qin, H.-L.; Lee, S.; Wang, Y.-T.; Du, G.-H. Anti-Influenza Virus Activities of Flavonoids from the Medicinal Plant Elsholtzia rugulosa. Planta Med. 2008, 74, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.M.; Fahim, H.I.; Ahmed, H.Y.; Almuzafar, H.; Ahmed, R.R.; Amin, K.A.; El-Nahass, E.-S.; Abdelazeem, W.H. The Preventive Effects and the Mechanisms of Action of Navel Orange Peel Hydroethanolic Extract, Naringin, and Naringenin in N-Acetyl-p-aminophenol-Induced Liver Injury in Wistar Rats. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 2745352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataneo, A.H.D.; Kuczera, D.; Koishi, A.C.; Zanluca, C.; Silveira, G.F.; de Arruda, T.B.; Suzukawa, A.A.; Bortot, L.O.; Dias-Baruffi, M.; Verri, W.A.V., Jr.; et al. The citrus flavonoid naringenin impairs the in vitro infection of human cells by Zika virus. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellavite, P.; Donzelli, A. Hesperidin and SARS-CoV-2: New Light on the Healthy Function of Citrus Fruits. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, A.; Alzuru, M.; Mendez, J.; Rodríguez-Ortega, M. Anti-Sindbis Activity of Flavanones Hesperetin and Naringenin. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ashaal, H.A.; El-Sheltawy, S.T. Antioxidant capacity of hesperidin from Citrus peel using electron spin resonance and cytotoxic activity against human carcinoma cell lines. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahmias, Y.; Goldwasser, J.; Casali, M.; van Poll, D.; Wakita, T.; Chung, R.T.; Yarmush, M.L. Apolipoprotein B-dependent hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin. Hepatology 2008, 47, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si-Si, W.; Liao, L.; Ling, Z.; Yun-Xia, Y. Inhibition of TNF-α/IFN-γ induced RANTES expression in HaCaT cell by naringin. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Huang, H.; Gu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y. Luteolin decreases the yield of influenza A virus in vitro by interfering with the coat protein I complex expression. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 73, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, L.R.F.; Wu, H.; Nebo, L.; Fernandes, J.B.; das Graças Fernandes da Silva, M.F.; Kiefer, W.; Kanitz, M.; Bodem, J.; Diederich, W.E.; Schirmeister, T.; et al. Flavonoids as noncompetitive inhibitors of Dengue virus NS2B-NS3 protease: Inhibition kinetics and docking studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frabasile, S.; Koishi, A.C.; Kuczera, D.; Silveira, G.F.; Verri, W.A., Jr.; Duarte Dos Santos, C.N.; Bordignon, J. The citrus flavanone naringenin impairs dengue virus replication in human cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.F.; Borge, G.I.A.; Piskula, M.; Tudose, A.; Tudoreanu, L.; Valentová, K.; Williamson, G.; Santos, C.N. Bioavailability of Quercetin in Humans with a Focus on Interindividual Variation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Nakata, R.; Oshima, S.; Inakuma, T.; Terao, J. Accumulation of quercetin conjugates in blood plasma after the short-term ingestion of onion by women. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000, 279, R461–R467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibellini, L.; Pinti, M.; Nasi, M.; Montagna, J.P.; De Biasi, S.; Roat, E.; Bertoncelli, L.; Cooper, E.L.; Cossarizza, A. Quercetin and Cancer Chemoprevention. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 591356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, G.; Lin, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, M.; Ji, L.; Lu, L.; Yu, L.; Han, G. Dietary quercetin combining intratumoral doxorubicin injection synergistically induces rejection of established breast cancer in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2010, 10, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai-Kashiwabara, M.; Asano, K. Inhibitory Action of Quercetin on Eosinophil Activation In Vitro. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 127105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, K.E.; Rice, C.M. Overview of hepatitis C virus genome structure, polyprotein processing, and protein properties. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2000, 242, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.B.; Bukh, J.; Kuiken, C.; Muerhoff, A.S.; Rice, C.M.; Stapleton, J.T.; Simmonds, P. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: Updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology 2013, 59, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.L.; Thio, C.L.; Martin, M.P.; Qi, Y.; Ge, D.; O’Huigin, C.; Kidd, J.; Kidd, K.; Khakoo, S.I.; Alexander, G.; et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature 2009, 461, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoofnagle, J.H. Course and outcome of hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002, 36, s21–s29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck-Ytter, Y.; Kale, H.; Mullen, K.D.; Sarbah, S.A.; Sorescu, L.; McCullough, A.J. Surprisingly small effect of antiviral treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 136, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afdhal, N.; Reddy, K.R.; Nelson, D.R.; Lawitz, E.; Gordon, S.C.; Schiff, E.; Nahass, R.; Ghalib, R.; Gitlin, N.; Herring, R.; et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for Previously Treated HCV Genotype 1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afdhal, N.; Zeuzem, S.; Kwo, P.; Chojkier, M.; Gitlin, N.; Puoti, M.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zarski, J.-P.; Agarwal, K.; Buggisch, P.; et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for Untreated HCV Genotype 1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Park, H.; Saab, S.; Ahmed, A.; Dieterich, D.; Gordon, S.C. Cost-effectiveness of all-oral ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 544–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstow, N.J.; Mohamed, Z.; Gomaa, A.; Sonderup, M.W.; A Cook, N.; Waked, I.; Spearman, C.W.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D. Hepatitis C treatment: Where are we now? Int. J. Gen. Med. 2017, 10, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhatwal, J.; He, T.; Lopez-Olivo, M. Systematic Review of Modelling Approaches for the Cost Effectiveness of Hepatitis C Treatment with Direct-Acting Antivirals. Pharmacoeconomics 2016, 34, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, N.T.; Crespi, C.M.; Liu, N.M.; Vu, J.Q.; Ahmadieh, Y.; Wu, S.; Lin, S.; McClune, A.; Durazo, F.; Saab, S.; et al. A Phase I Dose Escalation Study Demonstrates Quercetin Safety and Explores Potential for Bioflavonoid Antivirals in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. Phytother. Res. 2015, 30, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, O.; Fontanes, V.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Loo, R.; Loo, J.; Arumugaswami, V.; Sun, R.; Dasgupta, A.; French, S.W. The heat shock protein inhibitor Quercetin attenuates hepatitis C virus production. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Ansari, I.H.; Mehle, A.; Striker, R. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer-Based Intracellular Assay for the Conformation of Hepatitis C Virus Drug Target NS5A. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8277–8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lulu, S.S.; Thabitha, A.; Vino, S.; Priya, A.M.; Rout, M. Naringenin and quercetin—potential anti-HCV agents for NS2 protease targets. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 30, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formica, J.; Regelson, W. Review of the biology of quercetin and related bioflavonoids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1995, 33, 1061–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaschi, A.; Wang, Q.; Richards, A.; Theriault, A. Intestinal apolipoprotein B secretion is inhibited by the flavonoid quercetin: Potential role of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and diacylglycerol acyltransferase. Lipids 2002, 37, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoni, G.V.; Paglialonga, G.; Siculella, L. Quercetin inhibits fatty acid and triacylglycerol synthesis in rat-liver cells. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 39, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herker, E.; Harris, C.; Hernandez, C.; Carpentier, A.; Kaehlcke, K.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Ott, M. Efficient hepatitis C virus particle formation requires diacylglycerol acyltransferase-1. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prussia, A.; Thepchatri, P.; Snyder, J.P.; Plemper, R.K. Systematic Approaches towards the Development of Host-Directed Antiviral Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4027–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Á.; Del Campo, J.A.; Clement, S.; Lemasson, M.; García-Valdecasas, M.; Gil-Gómez, A.; Ranchal, I.; Bartosch, B.; Bautista, J.D.; Rosenberg, A.R.; et al. Effect of Quercetin on Hepatitis C Virus Life Cycle: From Viral to Host Targets. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Wilschut, J.; Smit, J.M. Dengue virus life cycle: Viral and host factors modulating infectivity. Cell Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2010, 67, 2773–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.A.; Jusoh, S.A. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies to Predict Flavonoid Binding on the Surface of DENV2 E Protein. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2016, 9, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control: New Edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Fried, J.R.; Gibbons, R.V.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Thomas, S.J.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Yoon, I.-K.; Jarman, R.G.; Green, S.; Rothman, A.L.; Cummings, D.A.T. Serotype-Specific Differences in the Risk of Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: An Analysis of Data Collected in Bangkok, Thailand from 1994 to 2006. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 4, e617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, S.; Rodrigo, C.; Rajapakse, A. Treatment of dengue fever. Infect. Drug Resist. 2012, 5, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.G.H.; Ooi, E.E.; Vasudevan, S. Current Status of Dengue Therapeutics Research and Development. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, S96–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehorn, J.; Yacoub, S.; Anders, K.L.; Macareo, L.R.; Cassetti, M.C.; Van, V.C.N.; Shi, P.-Y.; Wills, B.; Simmons, C.P. Dengue Therapeutics, Chemoprophylaxis, and Allied Tools: State of the Art and Future Directions. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kuhn, R.J.; Rossmann, M.G. A structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, M.T.U.; Mumtaz, A.; Naseem, R.; Ali, A.; Fatima, T.; Jabbar, T.; Ahmad, Z.; Ashfaq, U.A. Molecular Docking Based Screening of Plant Flavonoids as Dengue NS1 Inhibitors. Bioinformation 2014, 10, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, R.-F.; Zhang, L.; Chi, C.-W. Biological characteristics of dengue virus and potential targets for drug design. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2008, 40, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthilvel, P.; Lavanya, P.; Kumar, K.M.; Swetha, R.; Anitha, P.; Bag, S.; Sarveswari, S.; Vijayakumar, V.; Ramaiah, S.; Anbarasu, A. Flavonoid from Carica papaya inhibits NS2B-NS3 protease and prevents Dengue 2 viral assembly. Bioinformation 2013, 9, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igbe, I.; Shen, X.-F.; Jiao, W.; Qiang, Z.; Deng, T.; Li, S.; Liu, W.-L.; Liu, H.-W.; Zhang, G.-L.; Wang, F. Dietary quercetin potentiates the antiproliferative effect of interferon-α in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through activation of JAK/STAT pathway signaling by inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 113734–113748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashour, J.; Laurent-Rolle, M.; Shi, P.-Y.; García-Sastre, A. NS5 of Dengue Virus Mediates STAT2 Binding and Degradation. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 5408–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Jiménez, T.; Peña, L.M.-P.; Flores-Mendoza, L.; Sedeño-Monge, V.; Santos-López, G.; Rosas-Murrieta, N.; Reyes-Carmona, S.; Terán-Cabanillas, E.; Hernández, J.; Herrera-Camacho, I.; et al. Upregulation of the Suppressors of Cytokine Signaling 1 and 3 Is Associated with Arrest of Phosphorylated-STAT1 Nuclear Importation and Reduced Innate Response in Denguevirus-Infected Macrophages. Viral Immunol. 2016, 29, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Mendoza, L.K.; Estrada-Jiménez, T.; Sedeño-Monge, V.; Moreno, M.; Manjarrez, M.D.C.; González-Ochoa, G.; Peña, L.M.-P.; Reyes-Leyva, J. IL-10 and socs3 Are Predictive Biomarkers of Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 5197592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Ocampo, H.K.; Flores-Alonso, J.C.; Vallejo-Ruiz, V.; Reyes-Leyva, J.; Flores-Mendoza, L.; Herrera-Camacho, I.; Rosas-Murrieta, N.H.; Santos-López, G. Interferon lambda inhibits dengue virus replication in epithelial cells. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubol, S.; Phuklia, W.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Modhiran, N. Mechanisms of Immune Evasion Induced by a Complex of Dengue Virus and Preexisting Enhancing Antibodies. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiejak, J.; Dunlop, J.; Mackay, S.P.; Yarwood, S.J. Flavanoids induce expression of the suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3) gene and suppress IL-6-activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) activation in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. J. 2013, 454, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasso-Miranda, C.; Herrera-Camacho, I.; Flores-Mendoza, L.K.; Dominguez, F.; Vallejo-Ruiz, V.; Sanchez-Burgos, G.G.; Pando-Robles, V.; Santos-Lopez, G.; Reyes-Leyva, J. Antiviral and immunomodulatory effects of polyphenols on macrophages infected with dengue virus serotypes 2 and 3 enhanced or not with antibodies. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 1833–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.; Rothman, A. Immunopathological mechanisms in dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 19, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, B.E.E.; Koraka, P.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. Dengue Virus Pathogenesis: An Integrated View. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masood, K.I.; Jamil, B.; Rahim, M.; Islam, M.; Farhan, M.; Hasan, Z. Role of TNF α, IL-6 and CXCL10 in Dengue disease severity. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2018, 10, 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, J.H.; Becker, S.; Ebihara, H.; Geisbert, T.W.; Johnson, K.M.; Kawaoka, Y.; Lipkin, W.I.; Negredo, A.I.; Netesov, S.V.; Nichol, S.T.; et al. Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations. Arch. Virol. 2010, 155, 2083–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanbo, A.; Watanabe, S.; Halfmann, P.; Kawaoka, Y. The spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of Ebola virus proteins and RNA in infected cells. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapiaggi, F.; Pieraccini, S.; Potenza, D.; Vasile, F.; Podlipnik, Č. Designing Antiviral Substances Targeting the Ebola Virus Viral Protein 24. In Emerging and Reemerging Viral Pathogens; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanunza, E.; Frau, A.; Corona, A.; Tramontano, E. Antiviral Agents Against Ebola Virus Infection: Repositioning Old Drugs and Finding Novel Small Molecules. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2018, 51, 135–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baseler, L.; Chertow, D.S.; Johnson, K.M.; Feldmann, H.; Morens, D.M. The Pathogenesis of Ebola Virus Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2017, 12, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Petrillo, A.; Fais, A.; Pintus, F.; Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Piras, V.; Orrù, G.; Mameli, A.; Tramontano, E.; Frau, A. Broad-range potential of Asphodelus microcarpus leaves extract for drug development. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, G. Quercetin: A flavonol with multifaceted therapeutic applications? Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvier, N.M.; Palese, P. The biology of influenza viruses. Vaccine 2008, 26 (Suppl. 4), D49–D53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrbod, P.; Hudy, D.; Shyntum, D.; Markowski, J.; Łos, M.J.; Ghavami, S. Quercetin as a Natural Therapeutic Candidate for the Treatment of Influenza Virus. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansukh, E.; Muthu, M.; Paul, D.; Ethiraj, G.; Chun, S.; Gopal, J. Nature nominee quercetin’s anti-influenza combat strategy-Demonstrations and remonstrations. Rev. Med. Virol. 2017, 27, e1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansukh, E.; Nile, A.; Kim, D.H.; Oh, J.W.; Nile, S.H. New insights into antiviral and cytotoxic potential of quercetin and its derivatives—A biochemical perspective. Food Chem. 2020, 334, 127508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; von Itzstein, M. Recent Strategies in the Search for New Anti-Influenza Therapies. Curr. Drug Targets 2003, 4, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Hashem, A.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Doyle, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, Y.; Farnsworth, A.; Xu, K.; Li, Z.; et al. Targeting the HA2 subunit of influenza A virus hemagglutinin via CD40L provides universal protection against diverse subtypes. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, R.; Li, X.; He, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, J. Quercetin as an Antiviral Agent Inhibits Influenza A Virus (IAV) Entry. Viruses 2015, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.G.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Chung, H.S. Antiviral activity of ethanol extract of Geranii Herba and its components against influenza viruses via neuraminidase inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Velthuis, A.J.; Fodor, E. Influenza virus RNA polymerase: Insights into the mechanisms of viral RNA synthesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizky, W.C.; Jihwaprani, M.C.; Kindi, A.A.; Ansori, A.N.M.; Mushtaq, M. The pharmacological mechanism of quercetin as adjuvant therapy of COVID-19. Life Res. 2022, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.K.; Rehman, T.; Alam, P.; Al-Dosari, M.S.; Alqasoumi, S.I.; Alajmi, M.F. Plant-derived antiviral drugs as novel hepatitis B virus inhibitors: Cell culture and molecular docking study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 27, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, K.; Mathew, S.; Suhail, M.; Ali, A.; Damanhouri, G.; Azhar, E.; Qadri, I. Docking studies of Pakistani HCV NS3 helicase: A possible antiviral drug target. PLoS One 2014, 9, e106339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumbolo, S. The Role of Quercetin, Flavonols and Flavones in Modulating Inflammatory Cell Function. Inflamm. Allergy-Drug Targets 2010, 9, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.-Y.; Yu, Y.-L.; Cheng, W.-C.; OuYang, C.-N.; Fu, E.; Chu, C.-L. Immunosuppressive Effect of Quercetin on Dendritic Cell Activation and Function. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 6815–6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endale, M.; Park, S.-C.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Yang, Y.; Cho, J.Y.; Rhee, M.H. Quercetin disrupts tyrosine-phosphorylated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and myeloid differentiation factor-88 association, and inhibits MAPK/AP-1 and IKK/NF-κB-induced inflammatory mediators production in RAW 264.7 cells. Immunobiology 2013, 218, 1452–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Dodd, H.; Moser, E.; Sharma, R.; Braciale, T.J. CD4+ T cell help and innate-derived IL-27 induce Blimp-1-dependent IL-10 production by antiviral CTLs. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.P.; Saiyed, Z.M.; Gandhi, N.H.; Ramchand, C.N. The Flavonoid, Quercetin, Inhibits HIV-1 Infection in Normal Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Am. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 5, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Skrovankova, S.; Sochor, J. Quercetin and Its Anti-Allergic Immune Response. Molecules 2016, 21, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yao, J.; Han, C.; Yang, J.; Chaudhry, M.T.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Yin, Y. Quercetin, Inflammation and Immunity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleagrahara, N.; Hodgson, K.; Miranda-Hernandez, S.; Hughes, S.; Kulur, A.B.; Ketheesan, N. Flavonoid quercetin–methotrexate combination inhibits inflammatory mediators and matrix metalloproteinase expression, providing protection to joints in collagen-induced arthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 26, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, F.O.; Zarpelon, A.C.; Staurengo-Ferrari, L.; Fattori, V.; Casagrande, R.; Fonseca, M.J.V.; Cunha, T.M.; Ferreira, S.H.; Cunha, F.Q.; Verri, J.W.A. Quercetin Reduces Neutrophil Recruitment Induced by CXCL8, LTB4, and fMLP: Inhibition of Actin Polymerization. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Kasahara, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Takumi, O.; Kasai, T.; Onodera, K.; Kuwahara, M.; Oka, M.; Yoneda, Y.; Obika, S. Development of oligonucleotide-based antagonists of Ebola virus protein 24 inhibiting its interaction with karyopherin alpha 1. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4456–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraets, L.; Moonen, H.J.J.; Brauers, K.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Bast, A.; Hageman, G.J. Dietary Flavones and Flavonoles Are Inhibitors of Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 in Pulmonary Epithelial Cells. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2190–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieman, D.C.; Henson, D.A.; Maxwell, K.R.; Williams, A.S.; Mcanulty, S.R.; Jin, F.; Shanely, R.A.; Lines, T.C. Effects of Quercetin and EGCG on Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Immunity. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2009, 41, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, R.; Sharma, B.R.; Tuladhar, S.; Williams, E.P.; Zalduondo, L.; Samir, P.; Zheng, M.; Sundaram, B.; Banoth, B.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ Triggers Inflammatory Cell Death, Tissue Damage, and Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cytokine Shock Syndromes. Cell 2021, 184, 149–168.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, K.; Mukai, R.; Ishisaka, A. Quercetin and related polyphenols: New insights and implications for their bioactivity and bioavailability. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bruno, R.S. Endogenous and exogenous mediators of quercetin bioavailability. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).