Boosted Tetracycline and Cr(VI) Simultaneous Cleanup over Z-Scheme WO3/CoO p-n Heterojunction with 0D/3D Structure under Visible Light

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. XRD Analysis

2.2. Morphology

2.3. XPS

2.4. UV-Vis

2.5. Photocatalytic Activites

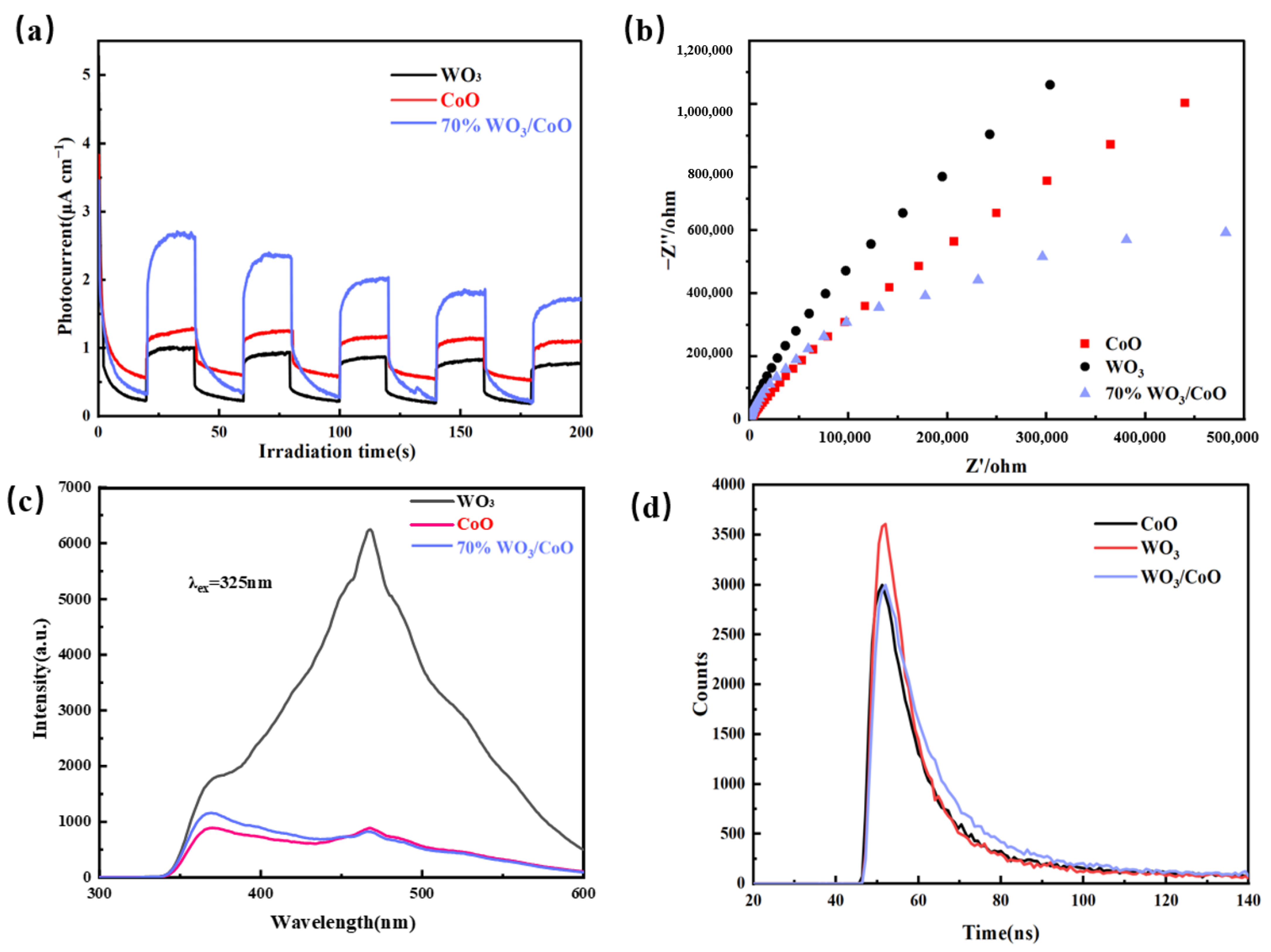

2.6. Electrochemical Test

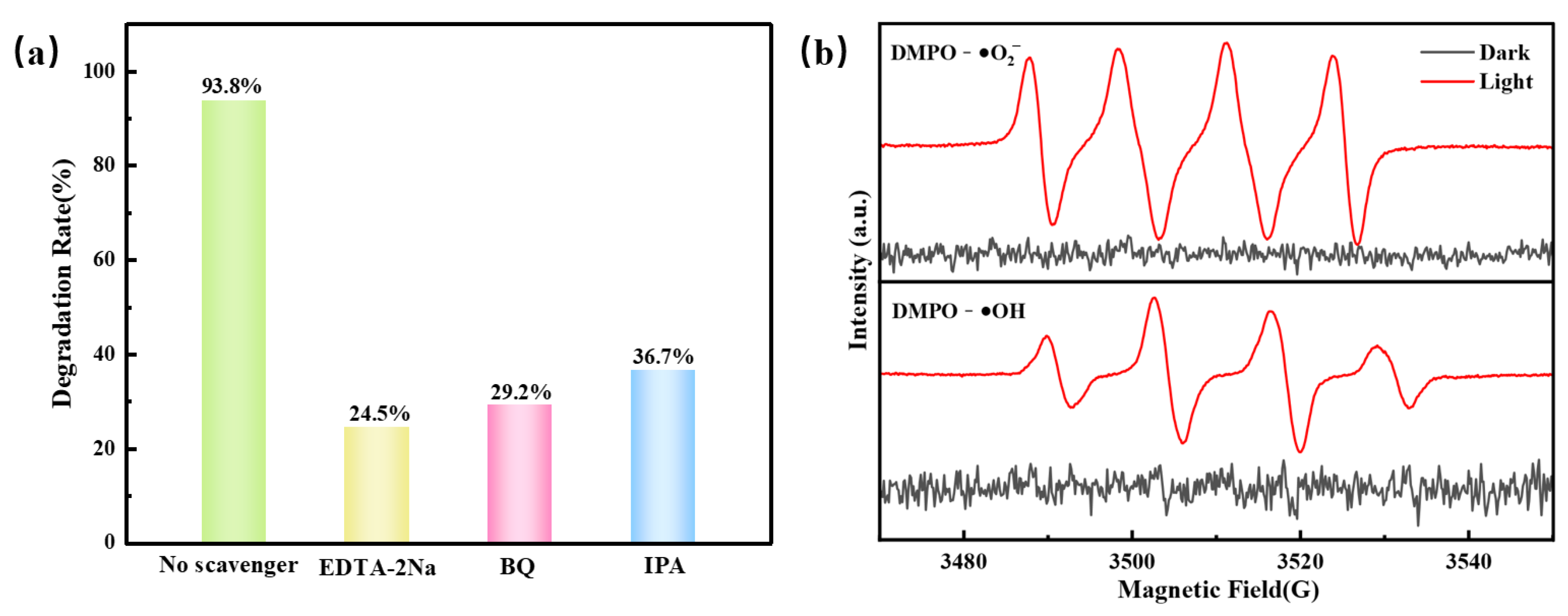

2.7. Radical Trapping and ESR

2.8. LC-MS

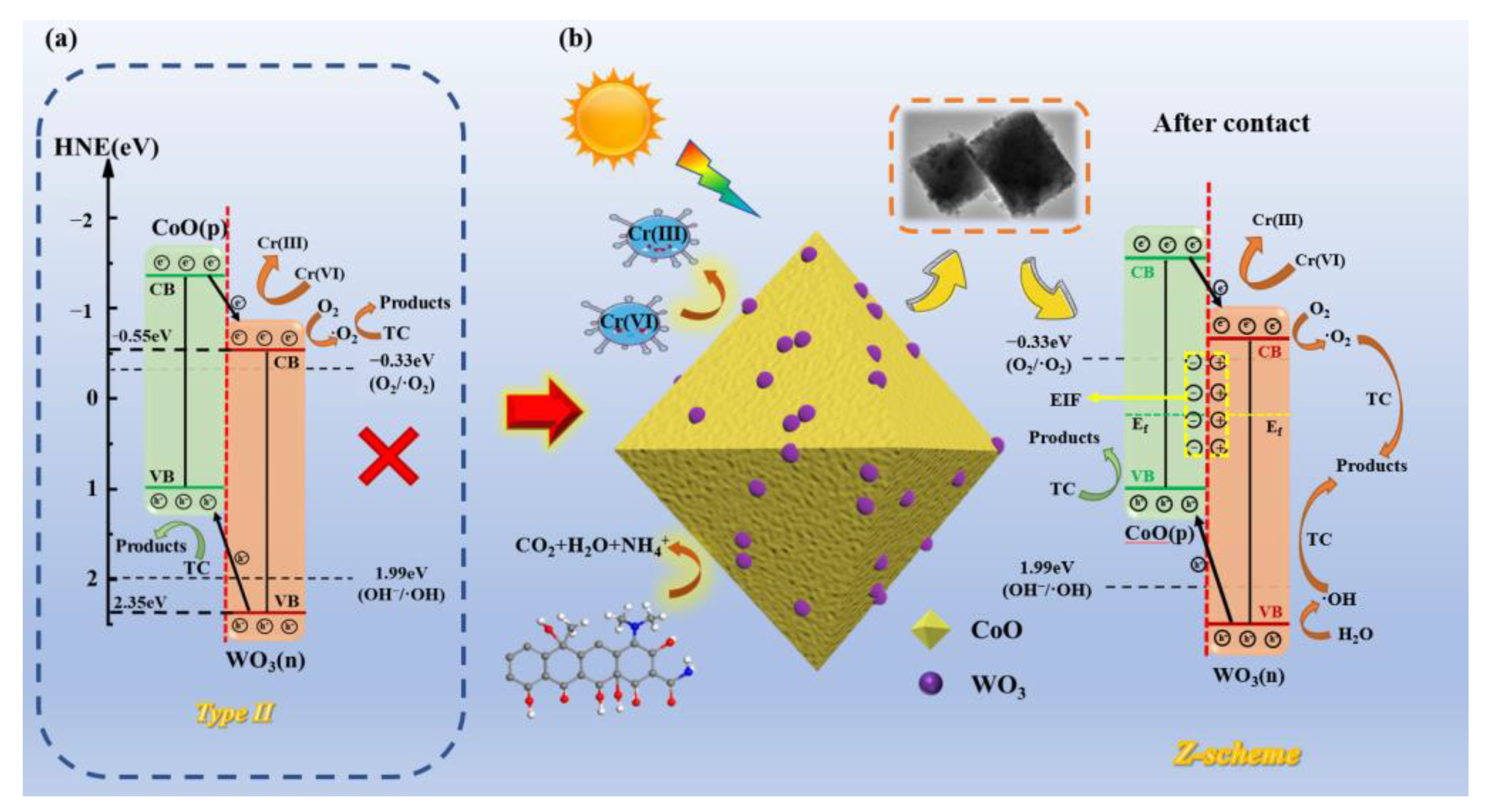

2.9. Photocatalytic Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

3.2. Characterization

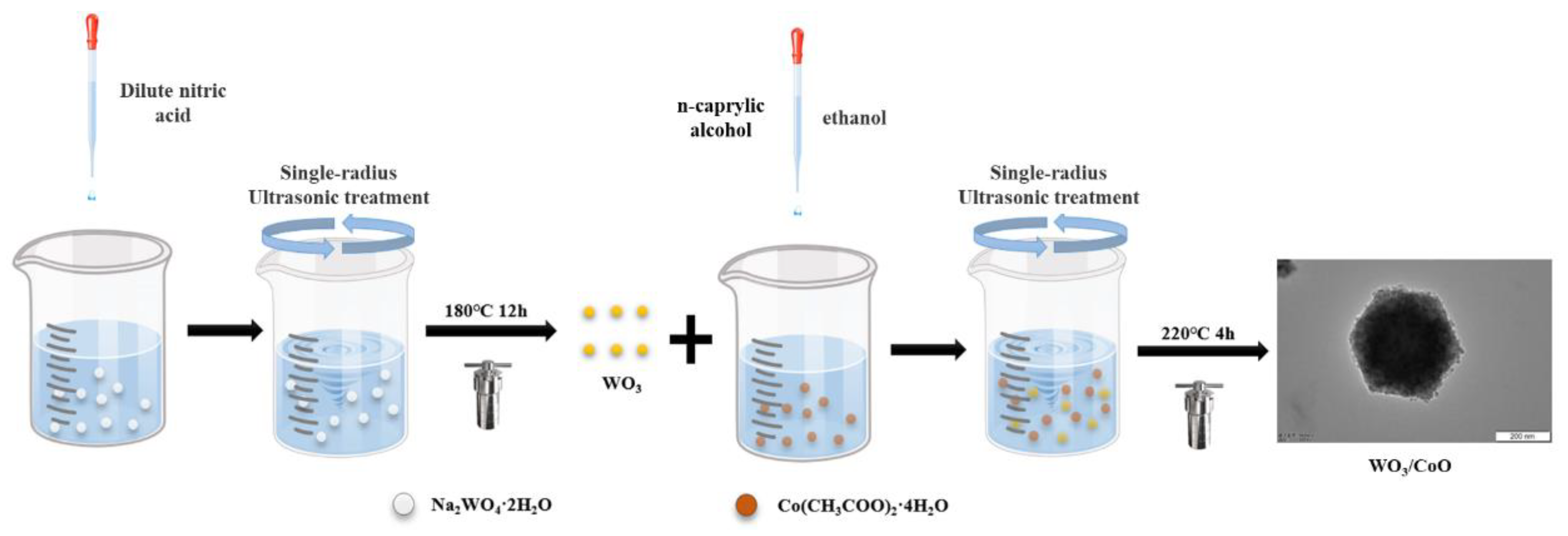

3.3. Synthesis of WO3, CoO, and WO3/CoO Heterojunctions

3.4. Measurement of Photocatalytic Activity

3.5. Reactive Radical Trapping Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Hu, Y.; Chen, D.Z.; Zhang, R.; Ding, Y.; Ren, Z.; Fu, M.S.; Cao, X.K.; Zeng, G.S. Singlet oxygen-dominated activation of peroxymonosulfate by passion fruit shell derived biochar for catalytic degradation of tetracycline through a non-radical oxidation pathway. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.J.; Wang, C.C.; Liu, Y.P.; Cai, M.J.; Wang, Y.N.; Zhang, H.Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.H.; Chen, X.B. Photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline antibiotic by a novel Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6 S-scheme heterojunction: Performance, mechanism insight and toxicity assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Cai, M.J.; Liu, Y.P.; Yang, F.; Zhang, H.Q.; Liu, J.S.; Li, S.J. Facile construction of novel organic-inorganic tetra (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin/Bi2MoO6 heterojunction for tetracycline degradation: Performance, degradation pathways, intermediate toxicity analysis and mechanism insight. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 605, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Lin, P.P.; Zheng, P.L.; Zhou, X.F.; Ning, X.M.; Zhan, L.; Wu, Z.J.; Liu, X.N.; Zhou, X.S. In suit constructing S-scheme FeOOH/MgIn2S4 heterojunction with boosted interfacial charge separation and redox activity for efficiently eliminating antibiotic pollutant. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Chen, J.L.; Hu, S.W.; Wang, H.L.; Jiang, W.; Chen, X.B. Facile construction of novel Bi2WO6/Ta3N5 Z-scheme heterojunction nanofibers for efficient degradation of harmful pharmaceutical pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 402, 126165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Wang, C.C.; Liu, Y.P.; Xue, B.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Mo, L.Y.; Chen, X.B. Photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics using a novel Ag/Ag2S/Bi2MoO6 plasmonic p-n heterojunction photocatalyst: Mineralization activity, degradation pathways and boosted charge separation mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 415, 128991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.X.; Sun, X.F.; Xian, T.; Gao, H.J.; Wang, S.F.; Yi, Z.; Wu, X.W.; Yang, H. Template-free synthesis of Bi2O2CO3 hierarchical nanotubes self-assembled from ordered nanoplates for promising photocatalytic applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 8279–8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sall, M.L.; Diaw, A.K.D.; Gningue-Sall, D.; Aaron, S.E.; Aaron, J.J. Toxic heavy metals: Impact on the environment and human health, and treatment with conducting organic polymers, a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29927–29942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.Q.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.Z.; Ren, B.; Ding, X.H.; Bian, H.L.; Yao, X. Total concentrations and sources of heavy metal pollution in global river and lake water bodies from 1972 to 2017. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalili, Z. Metal Oxides Nanoparticles: General Structural Description, Chemical, Physical, and Biological Synthesis Methods, Role in Pesticides and Heavy Metal Removal through Wastewater Treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Han, Y.C.; Wang, C.C. Fabrication strategies and Cr(VI) elimination activities of the MOF-derivatives and their composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.J.; Gu, H.Y.; Chen, M.D.; Li, X.P.; Zhao, H.W.; Yang, H.B. Dual Z-scheme Bi3TaO7/Bi2S3/SnS2 photocatalyst with high performance for Cr(VI) reduction and TC degradation under visible light irradiation. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 2417–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komijani, M.; Shamabadi, N.S.; Shahin, K.; Eghbalpour, F.; Tahsili, M.R.; Bahram, M. Heavy metal pollution promotes antibiotic resistance potential in the aquatic environment. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 274, 116569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; So, J.S. Heavy metal and antibiotic resistance of ureolytic bacteria and their immobilization of heavy metals. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 97, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, C.; Berendonk, T.U. Heavy metal driven co-selection of antibiotic resistance in soil and water bodies impacted by agriculture and aquaculture. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Jia, S.Y.; Zhang, T.T.; Zhuo, N.; Dong, Y.Y.; Yang, W.B.; Wang, Y.P. How heavy metals impact on flocculation of combined pollution of heavy metals-antibiotics: A comparative study. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 149, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Rao, L.; Wang, P.F.; Shi, Z.Y.; Zhang, L.X. Photocatalytic activity of N-TiO2/O-doped N vacancy g-C3N4 and the intermediates toxicity evaluation under tetracycline hydrochloride and Cr(VI) coexistence environment. Appl. Catal. B. 2020, 262, 118308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.S.; Lai, C.; Xu, P.A.; Zeng, G.M.; Huang, D.L.; Qin, L.; Yi, H.; Cheng, M.; Wang, L.L.; Huang, F.L.; et al. Facile synthesis of bismuth oxyhalogen-based Z-scheme photocatalyst for visible-light-driven pollutant removal: Kinetics, degradation pathways and mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Jiang, J.; Luo, Z.; Li, D.; Shi, M.; Sun, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Deng, B.; Yu, C. Novel starfish-like inorganic/organic heterojunction for Cr(VI) photocatalytic reduction in neutral solution. Colloids Surf. A 2023, 667, 131357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.E.; Liu, J.H.; Huang, Z.J.; Wu, S.Y.; Dai, X.D.; Zhang, L.; Cui, L.H. Effect of reduced graphene oxide doping on photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) and photocatalytic oxidation of tetracycline by ZnAlTi layered double oxides under visible light. Chemosphere 2019, 227, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, J.; Dai, B.L.; Cheng, Z.P.; Xu, J.M.; Ma, K.R.; Zhang, L.L.; Sheng, N.; Mao, G.X.; Wu, H.W.; et al. Simultaneous removal of tetracycline and Cr(VI) by a novel three-dimensional AgI/BiVO4 p-n junction photocatalyst and insight into the photocatalytic mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 369, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, B.; Wang, D.; Peng, X.; Zeng, L.; Li, Z.; Lei, L.; Qiu, M.; et al. Boosting the hydrogen evolution of layered double hydroxide by optimizing the electronic structure and accelerating the water dissociation kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 453, 139751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Liu, J.X.; Shi, F.; Ran, S.; Liu, S.H. Tm, Yb co-doped urchin-like CsxWO3 nanoclusters with dual functional properties: Transparent heat insulation performance and enhanced photocatalysis. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 8345–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuaid, A.; Almehmadi, M.; Alsaiari, A.A.; Allahyani, M.; Abdulaziz, O.; Alsharif, A.; Alsaiari, J.A.; Saih, M.; Alotaibi, R.T.; Khan, I. g-C3N4 Based Photocatalyst for the Efficient Photodegradation of Toxic Methyl Orange Dye: Recent Modifications and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2023, 28, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.H.; Mohamed, A.R.; Ong, W.J. Z-Scheme Photocatalytic Systems for Carbon Dioxide Reduction: Where Are We Now? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 22894–22915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.J.; Cheng, Y.L.; Zhou, N.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.P.; Li, K.; Huo, S.H.; Cheng, P.F.; Peng, P.; Zhang, R.C.; et al. Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using TiO2-based photocatalysts: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 121725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitre, S.P.; Overman, L.E. Strategic Use of Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1717–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.D.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.L.; Liu, B.Q.; Zheng, Z.Q.; Luo, D.X. Strategies to enhance photocatalytic activity of graphite carbon nitride-based photocatalysts. Mater. Des. 2021, 210, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhtouna, H.; Benzeid, H.; Zari, N.; Qaiss, A.K.; Bouhfid, R. Recent progress on Ag/TiO2 photocatalysts: Photocatalytic and bactericidal behaviors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 44638–44666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.R.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C.X.; Qian, X.X.; Zhang, M.; Wei, G.Y.; Khan, E.; Ng, Y.H.; Ok, Y.S. Recent advances in photodegradation of antibiotic residues in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.Y.; Chen, J.J.; Yang, Y.F.; Wang, D.J.; Bie, L.J.; Fahlman, B.D. Novel g-C3N4/CoO Nanocomposites with Significantly Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity for H-2 Evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017, 9, 12427–12435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraisamy, E.; Das, H.T.; Sharma, A.S.; Elumalai, P. Supercapacitor and photocatalytic performances of hydrothermally-derived Co3O4/CoO@carbon nanocomposite. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 6114–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.M.; Meng, L.J.; Luo, J.; Zhang, M.A.; Wang, Y.T.; Dai, Y.X.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yang, S.G.; He, H.; et al. Self-assembled ultrathin CoO/Bi quantum dots/defective Bi2MoO6 hollow Z-scheme heterojunction for visible light-driven degradation of diazinon in water matrix: Intermediate toxicity and photocatalytic mechanism. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 293, 120231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ma, L.; Ning, L.C.; Zhang, C.J.; Han, G.P.; Pei, C.J.; Zhao, H.; Liu, S.Z.; Yang, H.Q. Charge Separation between Polar {111} Surfaces of CoO Octahedrons and Their Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6109–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Wang, X.; Li, H.Q.; Zhi, C.Y.; Zhai, T.Y.; Bando, Y.; Golberg, D. CoO octahedral nanocages for high-performance lithium ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 4878–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.W.; Liu, M.M.; Lin, H.J.; Che, R.C. Morphology-dominant microwave absorption enhancement and electron tomography characterization of CoO self-assembly 3D nano-flowers. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 5216–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.M.; Ouyang, J.; Tang, A.D. Single step synthesis of high-purity CoO nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 8006–8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Sun, B.J.; Chu, J.Y.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.N.; Han, X.J.; Xu, P. Oxygen Vacancy-Induced Construction of CoO/h-TiO2 Z-Scheme Heterostructures for Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 28945–28955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Guo, S.H.; Xin, X.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, B.L.; Tang, S.W.; Li, X.H. Effective interface contact on the hierarchical 1D/2D CoO/NiCo-LDH heterojunction for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 549, 149108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsharpour, M.; Elyasi, M.; Javadian, H. A Novel N-Doped Nanoporous Bio-Graphene Synthesized from Pistacia lentiscus Gum and Its Nanocomposite with WO3 Nanoparticles: Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Wang, T.T.; Sun, H.G.; Shao, Q.; Zhao, J.K.; Song, K.K.; Hao, L.H.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.H. Two-step hydrothermally synthesized carbon nanodots/WO3 photocatalysts with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 15769–15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.M.; Ling, Y.C.; Wang, H.Y.; Yang, X.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, Y. Hydrogen-treated WO3 nanoflakes show enhanced photostability. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6180–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.S.; Xi, X.L.; Liu, Y.S.; Nie, Z.R.; Zhao, L.Y.; Zhang, Q.H. Regulation of morphology and visible light-driven photocatalysis of WO3 nanostructures by changing pH. Rare Met. 2021, 40, 1738–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Yu, J.G.; Wageh, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Mousavi, M.; Ghasemi, J.B.; Xu, F.Y. H-2-production and electron-transfer mechanism of a noble-metal-free WO3@ZnIn2S4 S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 17174–17184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.H.; Sun, Y.G.; Chen, W.W.; Song, F.G.; Xie, Y.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Rao, P.H. Z-scheme heterojunction based on NiWO4/WO3 microspheres with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 13801–13814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkanad, K.; Hezam, A.; Shekar, G.C.S.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Kala, A.L.A.; Al-Gunaid, M.Q.A.; Lokanath, N.K. Magnetic recyclable alpha-Fe2O3-Fe3O4/Co3O4-CoO nanocomposite with a dual Z-scheme charge transfer pathway for quick photo-Fenton degradation of organic pollutants. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 3084–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yu, J.G.; Guo, D.P.; Cui, C.; Ho, W.K. A Hierarchical Z-Scheme CdS-WO3 Photocatalyst with Enhanced CO2 Reduction Activity. Small 2015, 11, 5262–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.L.; Ao, Y.H.; Wang, P.F.; Wang, C. All-solid-state Z-scheme WO3 nanorod/ZnIn2S4 composite photocatalysts for the effective degradation of nitenpyram under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 121713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.X.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, B.; Wageh, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Yu, J.G. A Review of Direct Z-Scheme Photocatalysts. Small Methods 2017, 1, 1700080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Niu, C.G.; Guo, H.; Huang, D.W.; Wen, X.J.; Yang, S.F.; Zeng, G.M. Combination of efficient charge separation with the assistance of novel dual Z-scheme system: Self-assembly photocatalyst Ag@AgI/BiOI modified oxygen-doped carbon nitride nanosheet with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Wang, X.H.; Huang, J.F.; Li, S.X.; Meng, A.; Li, Z.J. Interfacial chemical bond and internal electric field modulated Z-scheme S-v-ZnIn2S4/MoSe2 photocatalyst for efficient hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, T.; Sambandan, E.; Yamashita, H. Synthesis and VOC degradation ability of a CeO2/WO3 thin-layer visible-light photocatalyst. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 94, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Pu, H.T.; Yin, J.L. Preparation and electrochromic property of covalently bonded WO3/polyvinylimidazole core-shell microspheres. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 292, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.Z.; Zhang, G.L. Synthesis and optical properties of high-purity CoO nanowires prepared by an environmentally friendly molten salt route. J. Cryst. Growth 2009, 311, 4275–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.H.; Zhang, L. Incorporation of CoO nanoparticles in 3D marigold flower-like hierarchical architecture MnCo2O4 for highly boosting solar light photo-oxidation and reduction ability. Appl. Catal. B. 2018, 237, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.L.; Guo, F.; Li, M.Y.; Shi, Y.; Shi, M.J.; Yan, C. Constructing 3D sub-micrometer CoO octahedrons packed with layered MoS2 shell for boosting photocatalytic overall water splitting activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 473, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.X.; Shen, R.C.; Jiang, Z.M.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.J.; Li, X. Integration of 2D layered CdS/WO3 S-scheme heterojunctions and metallic Ti3C2 MXene-based Ohmic junctions for effective photocatalytic H-2 generation. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, G.; Kumari, A.; Guo, C.S.; Naushad, M.; Vo, D.V.N.; Iqbal, J.; Stadler, F.J. Construction of dual Z-scheme g-C3N4/Bi4Ti3O12/Bi4O5I2 heterojunction for visible and solar powered coupled photocatalytic antibiotic degradation and hydrogen production: Boosting via I-/I-3(-) and Bi3+/Bi5+ redox mediators. Appl. Catal. B. 2021, 284, 119808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.Q.; Wang, X.; Pu, Y.; Liu, A.N.; Chen, C.; Zou, W.X.; Zheng, Y.L.; Huang, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.C.; et al. Facile ball-milling synthesis of CeO2/g-C3N4 Z-scheme heterojunction for synergistic adsorption and photodegradation of methylene blue: Characteristics, kinetics, models, and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 127719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, Y.K.; Chen, C.M.; Wang, T.H.; Zhang, M. Octopus tentacles-like WO3/C@CoO as high property and long life-time electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 281, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Yang, Q.; Liu, J.K.; Luo, H.A. Enhanced photoelectrochemical water oxidation of WO3/R-CoO and WO3/B-CoO photoanodes with a type II heterojunction. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 8079–8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Ansari, N.; Yang, Y.H.; Bachagha, K. Superiorly sensitive and selective H-2 sensor based on p-n heterojunction of WO3-CoO nanohybrids and its sensing mechanism. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 28823–28837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Du, J.N.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.Q.; Dai, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Xie, J.H.; Zou, J.L. Microrods-evolved WO3 nanospheres with enriched oxygen-vacancies anchored on dodecahedronal CoO(Co2+)@carbon as durable catalysts for oxygen reduction/evolution reactions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 601, 154195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Shi, W.L.; Zhu, C.; Li, H.; Kang, Z.H. CoO and g-C3N4 complement each other for highly efficient overall water splitting under visible light. Appl. Catal. B. 2018, 226, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.Y.; Yu, Z.H.; Dong, J.B.; Song, M.S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.L.; Ma, Z.F.; Su, H.; Yan, Y.S.; Huo, P.W. Facile microwave synthesis of a Z-scheme imprinted ZnFe2O4/Ag/PEDOT with the specific recognition ability towards improving photocatalytic activity and selectivity for tetracycline. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.X.; Li, L.L.; Xu, Z.; Sun, H.R.; Guo, F.; Shi, W.L. One-step simple green method to prepare carbon-doped graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for boosting visible-light photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 3122–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.J.; Shen, C.H.; Fei, Z.H.; Niu, C.G.; Lu, Q.; Guo, J.; Lu, H.M. Fabrication of a zinc tungstate-based a p-n heterojunction photocatalysts towards refractory pollutants degradation under visible light irradiation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 573, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Huang, X.L.; Chen, Z.H.; Cao, L.W.; Cheng, X.F.; Chen, L.Z.; Shi, W.L. Construction of Cu3P-ZnSnO3-g-C3N4 p-n-n heterojunction with multiple built-in electric fields for effectively boosting visible-light photocatalytic degradation of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 265, 118477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Saidu, U.; Adam, F.; Sreekantan, S.; Yahaya, N.; Ahmad, M.N.; Ramalingam, R.J.; Wilson, L.D. Floating ZnO QDs-Modified TiO2/LLDPE Hybrid Polymer Film for the Effective Photodegradation of Tetracycline under Fluorescent Light Irradiation: Synthesis and Characterisation. Molecules 2021, 26, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.X.; Tan, Y.; Sun, Z.M.; Zheng, S.L. Synthesis of BiOCl/TiO2 heterostructure composites and their enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Liang, H.; Li, C.P.; Bai, J. The synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic activity of heterostructure BiOCl/TiO(2)nanofibers composite for tetracycline degradation in visible light. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 2000–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Qiu, P.; Xiong, J.Y.; Zhu, X.T.; Cheng, G. Facilely anchoring Cu2O nanoparticles on mesoporous TiO2 nanorods for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction through efficient charge transfer. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 3709–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Yang, Y.; Long, L.Z.; Yang, L.; Yan, L.J.; Kong, W.J.; Liu, F.C.; Lv, F.; Liu, J. Fully-depleted dual P-N heterojunction with type-II band alignment and matched build-in electric field for high-efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 36069–36079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, R.; Manna, G.; Jana, S.; Pradhan, N. Ag2S-AgInS2: P-n junction heteronanostructures with quasi type-II band alignment. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 3074–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.T.; Liu, H.J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, D.Q.; Zhang, M.Z.; Gao, L.N.; Zhou, Y.H.; Lu, C.Y. Facile synthesis of Z-scheme NiO/alpha-MoO3 p-n heterojunction for improved photocatalytic activity towards degradation of methylene blue. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavani, T.; Madhavan, J.; Preeyanghaa, M.; Neppolian, B.; Murugesan, S. Construction of direct Z-scheme g-C3N4/Bi2WO6 heterojunction photocatalyst with enhanced visible light activity towards the degradation of methylene blue. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 10179–10190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, K.; Moniruddin, M.; Bakranov, N.; Kudaibergenov, S.; Nuraje, N. A heterojunction strategy to improve the visible light sensitive water splitting performance of photocatalytic materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 21696–21718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.M.; Wang, Y.Q.; Dong, C.L.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, J.; Xue, F.; Shen, S.H.; Guo, L.J. Boron-doped nitrogen-deficient carbon nitride-based Z-scheme heterostructures for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.J.; Wang, J.; Chai, Y.Q.; Zhang, Z.J.; Zhu, Y.F. Efficient Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting Induced by the Giant Internal Electric Field of a g-C3N4/rGO/PDIP Z-Scheme Heterojunction. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, S.; Hussain, S.Z.; Waseem, S.; Arshad, S.N. Photo-reduction of heavy metal ions and photo-disinfection of pathogenic bacteria under simulated solar light using photosensitized TiO2 nanofibers. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 20354–20362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.B.; Luo, Z.Z.; Tang, Z.Y.; Yu, C.L. Controllable construction of ZnWO4 nanostructure with enhanced performance for photosensitized Cr(VI) reduction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 490, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Guo, F.; Wang, H.; Han, M.; Li, H.; Yuan, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. Carbon dots decorated the exposing high-reactive (111) facets CoO octahedrons with enhanced photocatalytic activity and stability for tetracycline degradation under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 219, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Huang, W.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Cai, Q.; Jiang, X.; Lu, C.; Shi, W. Solvothermal synthesis of CoO/BiVO4 p-n heterojunction with micro-nano spherical structure for enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity towards degradation of tetracycline. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 135, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.Y.; Chen, Y.G.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Huang, G.B. Step-scheme WO3/CdIn2S4 hybrid system with high visible light activity for tetracycline hydrochloride photodegradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 535, 147682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.Y.; Yang, D.Q.; Wang, L.T.; Wen, S.J.; Cao, D.L.; Tu, C.Q.; Gao, L.N.; Li, Y.L.; Zhou, Y.H.; Huang, W. Facile construction of CoO/Bi2WO6 p-n heterojunction with following Z-Scheme pathways for simultaneous elimination of tetracycline and Cr(VI) under visible light irradiation. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 904, 164046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, C.; Cao, D.; Zhang, H.; Gao, L.; Shi, W.; Guo, F.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. Boosted Tetracycline and Cr(VI) Simultaneous Cleanup over Z-Scheme WO3/CoO p-n Heterojunction with 0D/3D Structure under Visible Light. Molecules 2023, 28, 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28124727

Lu C, Cao D, Zhang H, Gao L, Shi W, Guo F, Zhou Y, Liu J. Boosted Tetracycline and Cr(VI) Simultaneous Cleanup over Z-Scheme WO3/CoO p-n Heterojunction with 0D/3D Structure under Visible Light. Molecules. 2023; 28(12):4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28124727

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Changyu, Delu Cao, Hefan Zhang, Luning Gao, Weilong Shi, Feng Guo, Yahong Zhou, and Jiahao Liu. 2023. "Boosted Tetracycline and Cr(VI) Simultaneous Cleanup over Z-Scheme WO3/CoO p-n Heterojunction with 0D/3D Structure under Visible Light" Molecules 28, no. 12: 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28124727

APA StyleLu, C., Cao, D., Zhang, H., Gao, L., Shi, W., Guo, F., Zhou, Y., & Liu, J. (2023). Boosted Tetracycline and Cr(VI) Simultaneous Cleanup over Z-Scheme WO3/CoO p-n Heterojunction with 0D/3D Structure under Visible Light. Molecules, 28(12), 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28124727