Abstract

Entropy is a thermodynamic function used in chemistry to determine the disorder and irregularities of molecules in a specific system or process. It does this by calculating the possible configurations for each molecule. It is applicable to numerous issues in biology, inorganic and organic chemistry, and other relevant fields. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are a family of molecules that have piqued the curiosity of scientists in recent years. They are extensively researched due to their prospective applications and the increasing amount of information about them. Scientists are constantly discovering novel MOFs, which results in an increasing number of representations every year. Furthermore, new applications for MOFs continue to arise, illustrating the materials’ adaptability. This article investigates the characterisation of the metal–organic framework of iron(III) tetra-p-tolyl porphyrin (FeTPyP) and CoBHT (CO) lattice. By constructing these structures with degree-based indices such as the K-Banhatti, redefined Zagreb, and the atom-bond sum connectivity indices, we also employ the information function to compute entropies.

1. Introduction

Molecular organic frameworks are compounds composed of a central metal ion or atom surrounded by one or more organic ligands [1]. These ligands are typically organic molecules with a functional group that can bind to the metal center through covalent or coordinate bonds. The resulting structure is a complex in which the metal ion or atom is coordinated to the ligands and surrounded by a coordination sphere [2]. Molecular organic frameworks have many applications [3], including catalysis [4], sensing [5], and molecular recognition [6]. For example, some metalloenzyme active sites are molecular organic frameworks, and the coordination of the metal ion or atom to the ligands plays a critical role in the enzyme’s function. In addition to their practical applications, molecular organic frameworks are also studied for their fundamental chemical properties and as models for more complex systems. The structures of molecular organic frameworks can be determined using techniques such as X-ray crystallography, and their reactivity and stability can be studied through various chemical and spectroscopic methods [7]. Molecular organic frameworks have a wide range of applications due to their unique properties, such as catalytic activity, electronic conductivity [8], and magnetic behavior [9]. Some of the applications of molecular organic frameworks are catalysis. Molecular organic frameworks are widely used as catalysts in various chemical reactions [10]. The ligands surrounding the central metal atom or ion can modify its electronic properties and facilitate the reaction by lowering the activation energy required. For example, the ruthenium-based Grubbs’ catalyst is a molecular organic framework widely used in olefin metathesis reactions [11]. Molecular organic frameworks can be designed to detect specific analytes [12], such as metal ions or small molecules, by incorporating ligands with selective binding properties. The complex undergoes a change in its optical, electronic, or magnetic properties upon binding to the analyte, which can be detected and quantified [13]. Molecular organic frameworks can be designed to recognize and bind specific target molecules, such as biomolecules, by incorporating ligands with complementary binding sites. This can be useful for developing biosensors [14] or drug discovery [15]. Molecular organic frameworks with conductive ligands can be used in organic light emitting diodes [16] and organic photovoltaics [17] due to their ability to transport charge and emit light. Overall, the unique properties of molecular organic frameworks make them versatile materials with applications in various fields, including chemistry, biology, and materials science [18]. The optical properties of the metallic nanoparticles are of interest to scientists and researchers. The nanoparticles’ heat disintegrates malignant tissue while sparing healthy cells. Niobium nanoparticles are ideal for optothermal cancer treatment because of their fast ligand binding [19]. Scientists have been fascinated by chemical graph theory, an emerging discipline of applied chemistry, for the past 20 years [20,21,22,23]. In this field of study, substantial discoveries have been made by scientists, including [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Using combinatorial techniques such as vertex and edge partitions, we look into the interaction between atoms and bonds. In order to provide instructions for treating malignancies or tumours, topological indices are crucial. These indices can be discovered numerically or experimentally. Although expensive, experimental data are valuable; consequently, computer analysis provides a time- and cost-effective option.

A topological index is created by converting a chemical structure into a number [31]. The topological index is a graph invariant that describes the topology of the graph and is true even during graph automorphism. A topological index is a number that can only be expressed in terms of the graph. In chemical graph theory, the eccentricity-based topological indices are essential [32]. By investigating the connection between a specific hydrocarbon compound’s molecular structure and its physical and chemical properties in 1947, a chemist named Wiener developed a topological index for the first time [33]. The second Zagreb index was redefined in 2010, and Damir et al. determined that it was identical to the inverse sum indeg index [34].

We applied valency-based entropies in this article, where and denote the valency of atoms, and , within the molecule. With the use of several Banhatti indices and the valency of atom bonds, Kulli began computing valency-based topological indices in 2016 [35,36,37], all of which are defined as follows:

The K-Banhatti polynomial and index are:

The second K-Banhatti polynomial and index are:

The first hyper K-Banhatti polynomial and index are:

The concept of Redefined Zagreb indices was initiated by Ranjini in [38], and Shanmukha in [39] and defined as

The third redefined Zagreb index was defined as

The notion of atom-bond connectivity index and sum connectivity index gathered by Ali et al., and initiated the new molecular descriptor named as the atom-bond sum-connectivity index in [40]:

The idea of entropy was initiated by Shannon in 1948 [41]. The quantity of thermal energy per unit temperature in a system that is not accessible for meaningful work is measured by entropy [42,43]. The system’s molecular disorder is also measured by Entropy [44,45]. In this article, we have computed entropies of metal organic frameworks of [46,47,48].

2. Entropy Measures

The entropy measure of edge-weighted graph was initiated in 2009 [49], for an edge-weighted graph, where is the vertex set, the edge set, and the edge-weight of an edge is represented by . The entropy of a graph T is

- The first -Banhatti entropy

- The second -Banhatti entropy

- The first K-hyper Banhatti entropy

- The second -hyper Banhatti entropy

- The first redefined Zagreb entropyLet . The first redefined Zagreb index (5) isThe first redefined Zagreb entropy is obtained using Equation (9)

- The second redefined Zagreb entropyLet . The second redefined Zagreb index (6) isThe second redefined Zagreb entropy is obtained using Equation (9)

- The third redefined Zagreb entropyLet . The third redefined Zagreb index (7) isThe third redefined Zagreb entropy is obtained by using Equation (9)

- Atom-bond sum connectivity EntropyLet . The atom-bond connectivity index (8) isThe atom-bond sum connectivity entropy is obtained using Equation (9)

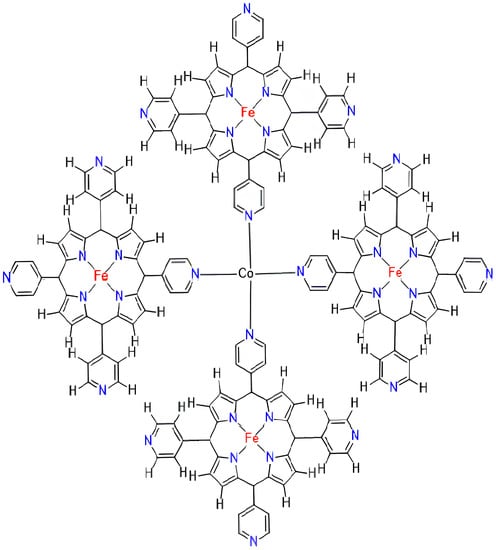

3. Entropy Measure of FeTPyP-Co

The FeTPyP-Co MOFs, also known as iron(III) tetra-p-tolyl porphyrin (FeTPyP) frameworks coordinated with cobalt (Co) ligands, are a type of molecular organic framework. The structure of FeTPyP-Co MOFs consist of a central iron(III)ion coordinated with four p-tolylporphyrin (TPyP) ligands and one Co ligand. The TPyP ligands provide a tetradentate coordination, while the Co ligand provides a monodentate coordination. The properties of FeTPyP-Co MOFs exhibit catalytic activity for a variety of reactions, including oxidation reactions and cyclohexane oxidation. The Co ligand can modulate the redox properties of the iron center, enhancing its ability to oxidize substrates [50]. FeTPyP-Co MOFs have been studied for their magnetic properties, which are influenced by the coordination environment of the iron center. The TPyP ligands can induce antiferromagnetic coupling between the iron centers, while the Co ligand can modulate the magnitude of the coupling. FeTPyP-Co MOFs have also been investigated for their optical properties, which arise from the TPyP ligands. The TPyP ligands can absorb visible light and undergo photoinduced electron transfer, leading to the generation of reactive intermediates with potential applications in photocatalysis. Overall, FeTPyP-Co MOFs are a promising class of molecular organic frameworks with diverse applications in catalysis, electrocatalysis, magnetism, and optics. is a graph of FeTPyP-Co (TPyP ¼ Tetrakis pyridyl porphyrin) metal–organic frameworks, which embodies cells in rows and embodies cells in columns. The molecular graph of FeTPyP-Co is given in Figure 1. There are total vertices and edges. In this article, we tried to explain , with a total atom count of ; as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

FeTPyP-Co MOFs Structure.

Table 1 represents the atom-bond partitions of derived from these results.

Table 1.

Atom-bond partition of FeTPyP-Co.

- The first -Banhatti entropy measure of

- The second K-Banhatti entropy measure of

- The first K-hyper Banhatti entropy measure of

- The second -hyper Banhatti entropy measure of

- The first redefined Zagreb entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (26) at , we obtain

- The second redefined Zagreb entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (28) at , we obtain

- The third redefined Zagreb entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (30) at , we get

- Atom-bond sum connectivity entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (32) at , we have

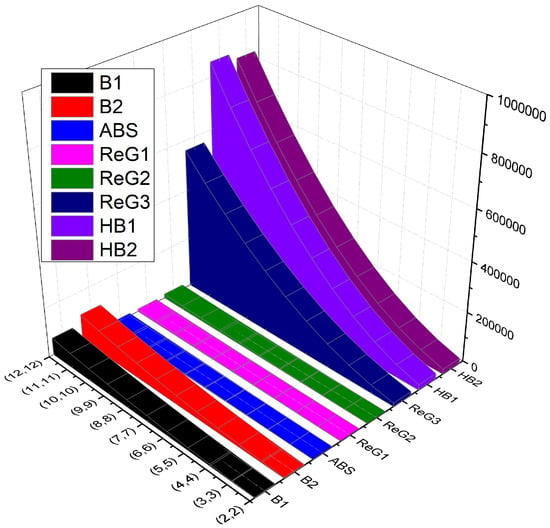

Comparison

In this section, comparison (numerical in Table 2 and graphical in Figure 2) of various computed K-Banhatti and the redefined Zagreb indices is presented.

Table 2.

Numerical comparison of the computed indices of .

Figure 2.

Graphical comparison of indices of .

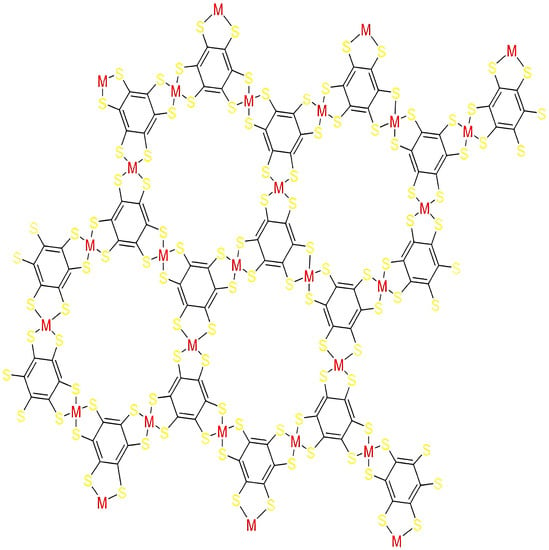

4. Entropy Measure of CoBHT (CO) Lattice

The CoBHT (CO) lattice refers to a type of molecular organic framework in which cobalt (Co) is coordinated with 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) ligands and carbon monoxide (CO) ligands. The structure of the CoBHT (CO) lattice consists of a one-dimensional array of Co atoms coordinated with TCNQ and CO ligands. Each Co atom is coordinated with four TCNQ ligands and two CO ligands, forming an octahedral coordination geometry. The TCNQ ligands stack along the one-dimensional axis, forming a charge transfer complex with the Co atoms, and the properties of the CoBHT (CO) lattice exhibits interesting magnetic properties, including spin-crossover behavior and long-range magnetic ordering. The TCNQ ligands provide a highly anisotropic electronic structure, which can result in highly directional exchange interactions between the Co atoms. The CO ligands can modulate the magnetic properties of the Co atoms by influencing their coordination environment and electronic structure. The CoBHT (CO) lattice has potential applications in magnetic data storage, spintronics, and molecular electronics. Overall, the CoBHT (CO) lattice is a promising molecular organic framework with unique magnetic properties and potential applications in various fields.

The , a graph of CoBHT (CO) lattice, denotes the unit cell in the column and g denotes the unit cell in a row. The structure of the molecular graph of CoBHT (CO) lattice is shown in Figure 3, where the portion in a square shows the unit structure of CoBHT (CO) lattice. The has vertices and edges. In Figure 3 two-dimensional lattice structure is shown.

Figure 3.

Supercell of 3 × 3 CoBHT (CO) lattice.

- The 1st -Banhatti entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (34) at , we obtain

Table 3. Atom-bonds partition of .Table 3. Atom-bonds partition of .

Table 3. Atom-bonds partition of .Table 3. Atom-bonds partition of .Types of Atom Bonds Cardinality of Atom bonds - The second -Banhatti entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (36) at , we have

- The first -hyper Banhatti entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (38) at , we get

- The second -hyper Banhatti entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (40) at , we haveThe second K-hyper Banhatti entropy measure of is obtained in view of Equation (41) Table 3 and Equation (13):This gives

- The first redefined Zagreb entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (43) at , we obtain the first redefined Zagreb index

- The second redefined Zagreb entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (45) at , we obtain

- The third redefined Zagreb entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (47) at , we obtain the third redefined Zagreb index

- Atom-bond sum connectivity entropy measure ofAfter differentiating Equation (49) at , we have

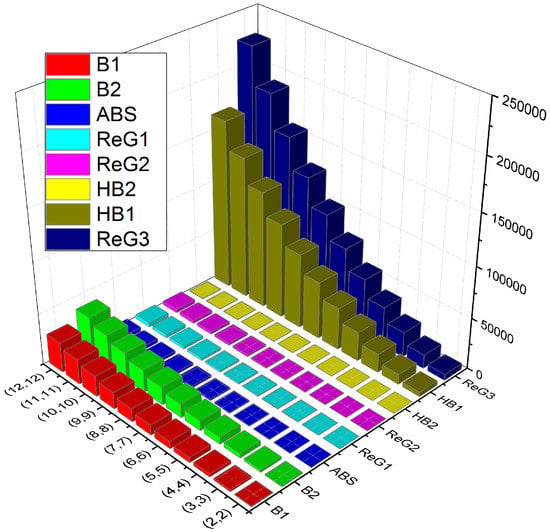

Comparison

In this section, we present a comparison (numerical in Table 4 and graphical in Figure 4) of various K-Banhatti and redefined Zagreb indices for .

Table 4.

Numerical comparison of the topological indices of .

Figure 4.

Graphical comparison of TIs of .

5. Conclusions

MOFs’ allure stems from their distinct qualities, which can be predicted and modified. MOF synthesis and analysis employ a diverse set of current scientific methodologies and procedures. Because of the amazing structural diversity observed in MOFs, these methods allow scientists to predict and regulate the properties of synthesised materials. The ability to tailor the structure of MOFs enables the development of materials with specialised properties for certain applications. The amazing optical attributes of metallic nanoparticles have piqued the curiosity of researchers and scientists of this era. In this study, the CoBHT (CO) lattice and the iron(III) tetra-p-tolyl porphyrin (FeTPyP), two significant metal–organic frameworks, have been investigated and using the atom-bond partitioning strategy, the precise formulas of numerous significant valency-based topological indices have been determined. The CoBHT (CO) lattice has potential applications in magnetic data storage, spintronics, and molecular electronics. Overall, the CoBHT (CO) lattice is a promising molecular organic framework with unique magnetic properties and potential applications in various fields. In this study, we also looked at the distance-based entropies related to a novel information function and evaluated the association between degree-based topological indices and degree-based entropies in light of Shannon’s entropy and Chen et al.’s entropy. This has been utilized to determine the complexity of molecules and molecular ensembles as well as their electrical structure, signal processing, physicochemical reactions, and complexity. The K-Banhatti entropy may be utilized in combination with thermodynamic entropy, chemical structure, energy, and mathematics to fill in gaps across various fields of study and build the foundation for new interdisciplinary research. This will open up new avenues for research in this field, as we plan to apply this concept to diverse metal organic frameworks in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I., A.R.K., M.N.H., F.T., M.U.G. and S.H.; Methodology, M.I., A.R.K., M.N.H., F.T. and S.H.; Software, A.R.K. and S.H.; Validation, M.I., A.R.K., M.N.H. and F.T.; Formal analysis, M.I., A.R.K., M.N.H., F.T., M.U.G. and S.H.; Investigation, M.I., A.R.K., M.U.G. and S.H.; Writing—original draft, M.I. and S.H.; Writing—review & editing, A.R.K. and M.N.H.; Visualization, A.R.K.; Funding acquisition, M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thanks Universiti Malaysia Terengganu for providing funding support for this project (UMT/TAPE-RG/2021/55330). This research was supported by the researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2023R401), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Not applicable.

References

- Cook, T.R.; Zheng, Y.-R.; Stang, P.J. Metal–Organic Frameworks and Self-Assembled Supramolecular Coordination Complexes: Comparing and Contrasting the Design, Synthesis, and Functionality of Metal–Organic Materials. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 734–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.-C.; Long, J.R.; Yaghi, O.M. Introduction to Metal–Organic Frameworks; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 112, pp. 673–674. [Google Scholar]

- Yasin, G.; Ibrahim, S.; Ajmal, S.; Ibraheem, S.; Ali, S.; Nadda, A.K.; Zhang, G.; Kaur, J.; Maiyalagan, T.; Gupta, R.K. Tailoring of electrocatalyst interactions at interfacial level to benchmark the oxygen reduction reaction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 469, 214669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Gates, B.C. Catalysis by Metal Organic Frameworks: Perspective and Suggestions for Future Research. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 1779–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Deep, A.; Kim, K.-H. Metal organic frameworks for sensing applications. Trac. Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 73, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.; Husain, A.; Bhasin, K.K.; Kumar, G. Metal–Organic Framework-Based Selective Molecular Recognition of Organic Amines and Fixation of CO2 into Cyclic Carbonates. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 6977–6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazaj, M.; Kaučič, V.; Zabukovec Logar, N. Chemistry of Metal-organic Frameworks Monitored by Advanced X-ray Diffraction and Scattering Techniques. Acta Chim. Slov. 2016, 63, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgopolova, E.A.; Brandt, A.J.; Ejegbavwo, O.A.; Duke, A.S.; Maddumapatabandi, T.D.; Galhenage, R.P.; Larson, B.W.; Reid, O.G.; Ammal, S.C.; Heyden, A.; et al. Electronic Properties of Bimetallic Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Tailoring the Density of Electronic States through MOF Modularity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5201–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Park, J.; Song, I.; Yoon, S.M. The Magnetism of Metal–Organic Frameworks for Spintronics. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2021, 42, 1170–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Navalon, S.; Asiri, A.M.; Garcia, H. Metal organic frameworks as solid catalysts for liquid-phase continuous flow reactions. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, M.S.; Love, J.A.; Grubbs, R.H. Mechanism and Activity of Ruthenium Olefin Metathesis Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6543–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.-L.; Razavi, S.A.A.; Piroozzadeh, M.; Morsali, A. Sensing organic analytes by metal–organic frameworks: A new way of considering the topic. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 1598–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, N.; Uemura, T. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Macromolecular Recognition and Separation. Matter 2020, 3, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lou, Y.; Guo, C.; Jia, Q.; Song, Y.; Tian, J.-Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; He, L.; Du, M. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) based chemosensors/biosensors for analysis of food contaminants. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, H.D.; Walton, S.P.; Chan, C. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Drug Delivery: A Design Perspective. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7004–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.; Shrestha, S.; Vilá, R.A.; Huang, W.; Liu, C.; Hou, C.-H.; Huang, H.-H.; Wen, X.; Li, M.; Wiederrecht, G.; et al. Bright and stable light-emitting diodes made with perovskite nanocrystals stabilized in metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Photonics 2021, 15, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, Z.; Li, M.-Q.; Diao, Y.; Lin, F.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Tieu, P.; Gao, W.; Qi, F.; et al. 2D metal–organic framework for stable perovskite solar cells with minimized lead leakage. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamaki, Y.; Tsuji, M.; Heidrick, Z.; Watson, O.; Durchman, J.; Salmon, C.; Burgin, S.R.; Beyzavi, H. Preparation and Applications of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs): A Laboratory Activity and Demonstration for High School and/or Undergraduate Students. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, M.U.; Sultan, F.; Tag El Din, E.S.M.; Khan, A.R.; Liu, J.B.; Cancan, M. A Paradigmatic Approach to Find the Valency-Based K-Banhatti and Redefined Zagreb Entropy for Niobium Oxide and a Metal–Organic Framework. Molecules 2022, 27, 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacGillivray, L.R. (Ed.) Metal-Organic Frameworks: Design and Application; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- James, S.L. Metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003, 32, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, H.; Cordova, K.E.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, S. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5415–5418. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.B.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Lin, W. The Kirchhoff index and spanning trees of Möbius/cylinder octagonal chain. Discret. Appl. Math. 2022, 307, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Bao, Y.; Zheng, W.T.; Hayat, S. Network coherence analysis on a family of nested weighted n-polygon networks. Fractals 2021, 29, 2150260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Zhao, J.; He, H.; Shao, Z. Valency-based topological descriptors and structural property of the generalized sierpiński networks. J. Stat. Phys. 2019, 177, 1131–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-B.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Wei, B. Zagreb indices and multiplicative zagreb indices of eulerian graphs. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2019, 42, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Zhao, J.; Min, J.; Cao, J. The Hosoya index of graphs formed by a fractal graph. Fractals 2019, 27, 1950135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Pan, X.F. Minimizing Kirchhoff index among graphs with a given vertex bipartiteness. Appl. Math. Comput. 2016, 291, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Pan, X.F.; Yu, L.; Li, D. Complete characterization of bicyclic graphs with minimal Kirchhoff index. Discret. Appl. Math. 2016, 200, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Ghani, M.U.; Ghaffar, A.; Asif, H.M.; Inc, M. Characterization of temperature indices of silicates. Silicon 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.M.; Khan, A.R.; Ghani, M.U.; Ghaffar, A.; Inc, M. Computation of Zagreb Polynomials and Zagreb Indices for Benzenoid Triangular & Hourglass System. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, H. Structural determination of paraffin boiling points. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukičević, D.; Gašperov, M. Bond additive modeling 1. Adriatic indices. Croat. Chem. Acta 2010, 83, 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kulli, V.R. On K Banhatti indices of graphs. J. Comput. Math. Sci. 2016, 7, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kulli, V.R.; On, K. On K hyper-Banhatti indices and coindices of graphs. Int. Res. J. Pure Algebra 2016, 6, 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kulli, V.R. On multiplicative K Banhatti and multiplicative K hyper-Banhatti indices of V-Phenylenic nanotubes and nanotorus. Ann. Pure Appl. Math. 2016, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjini, P.S.; Lokesha, V.; Usha, A. Relation between phenylene and hexagonal squeeze using harmonic index. Int. J. Graph Theory 2013, 1, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, N.; Long, K.; Mufti, Z.S.; Sajid, H.; Rehman, A. Degree-based topological indices of boron b12. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5563218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Furtula, B.; Redžepović, I.; Gutman, I. Atom-bond sum-connectivity index. J. Math. Chem. 2022, 60, 2081–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Ghani, M.U.; Kamran, M.; Shazib Hameed, M.; Hussain Khan, R.; Baig, A.Q. Degree-Based Entropy for a Non-Kekulean Benzenoid Graph. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 2288207. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, T.; Faizi, S.; Zafar, S. Distance based entropy measure of interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy sets and its application in multicriteria decision making. Adv. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 2018, 3637897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S. Computing distance-based topological descriptors of complex chemical networks: New theoretical techniques. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 688, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Ali, H.; Binyamin, M.A.; Ali, B.; Liu, J.B.; Fan, C. On distance-based topological descriptors of chemical interconnection networks. J. Math. 2021, 2021, 5520619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.S.; Safdar, M.U. K Banhatti and K hyper-Banhatti indices of nanotubes. Eng. Appl. Sci. Lett. 2019, 2, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.; Rafaqat, M.; Nazeer, W.; Gao, W. K Banhatti and K hyper Banhatti indices of circulant graphs. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulli, V.R.; Chaluvaraju, B.; Boregowda, H.S. Connectivity Banhatti indices for certain families of benzenoid systems. J. Ultra Chem. 2017, 13, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yang, N.; Ding, X.; Ma, L. An unsupervised feature selection algorithm: Laplacian score combined with distance-based entropy measure. In Proceedings of the 2009 Third International Symposium on Intelligent Information Technology Application, Nanchang, China, 21–22 November 2009; IEEE: Picataway, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Ray, K.; Collins, M.J.; Farquhar, E.R.; Frisch, J.R.; Gómez, L.; Jackson, T.A.; Kerscher, M.; Waleska, A.; Comba, P.; et al. Nonheme oxoiron (IV) complexes of pentadentate N5 ligands: Spectroscopy, electrochemistry, and oxidative reactivity. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).