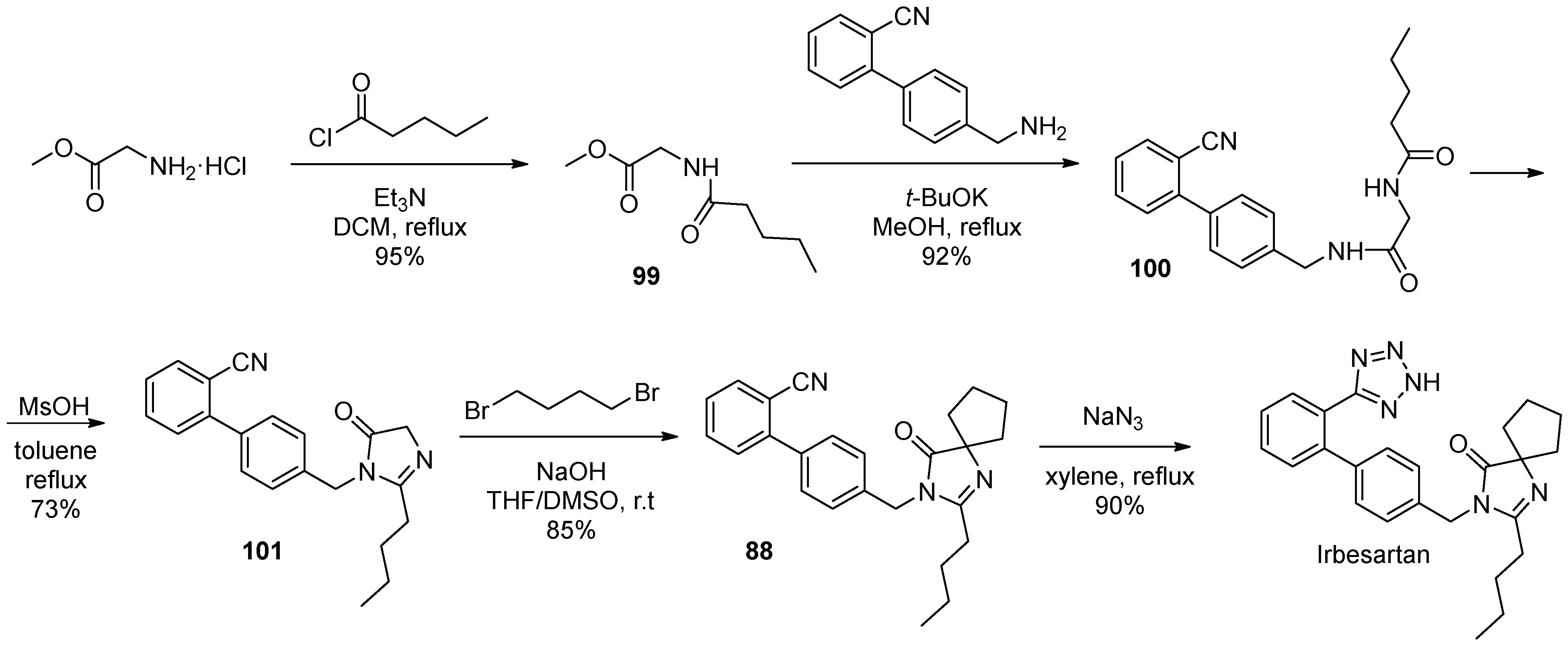

Synthetic Routes to Approved Drugs Containing a Spirocycle †

Abstract

1. Introduction

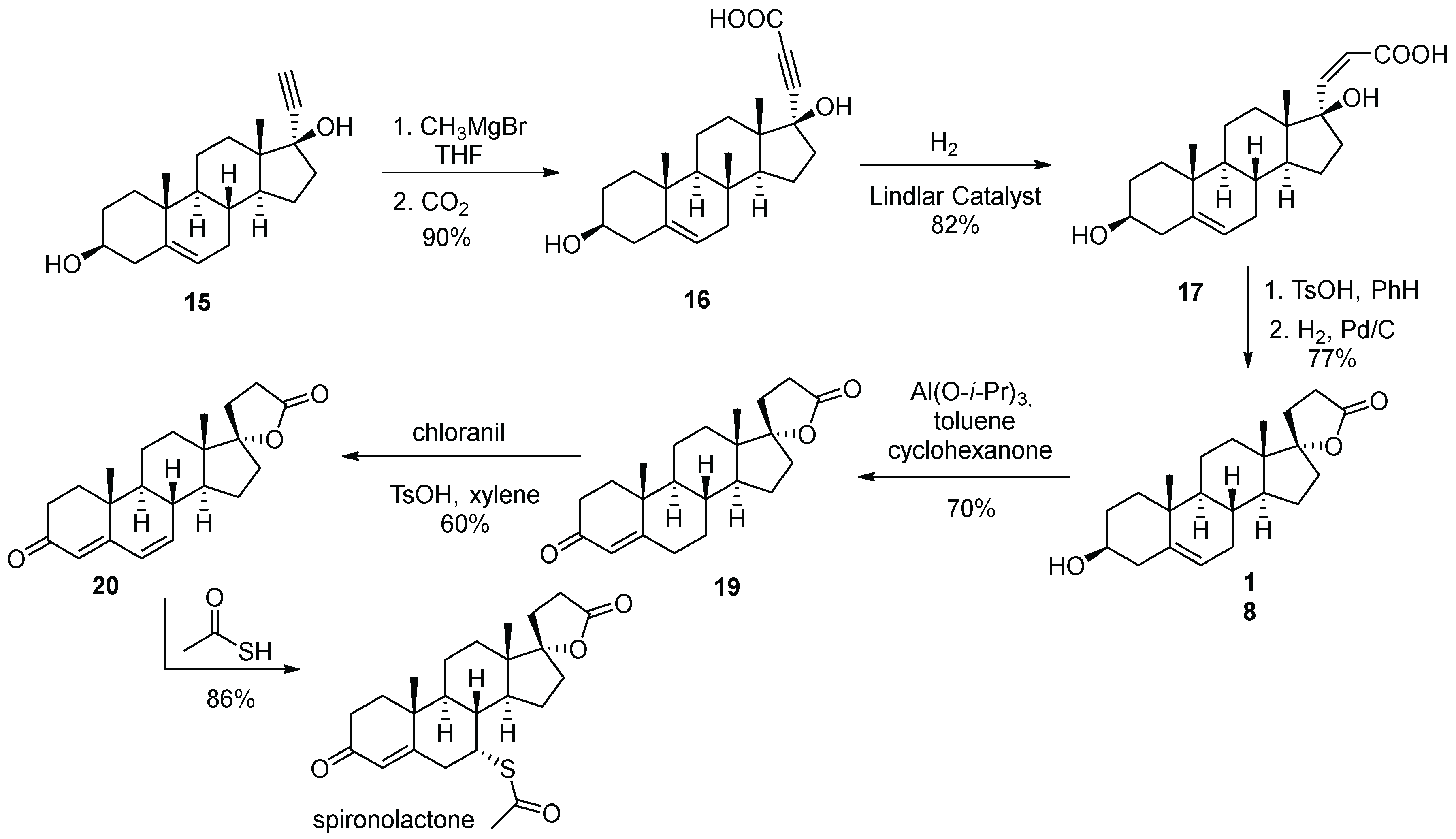

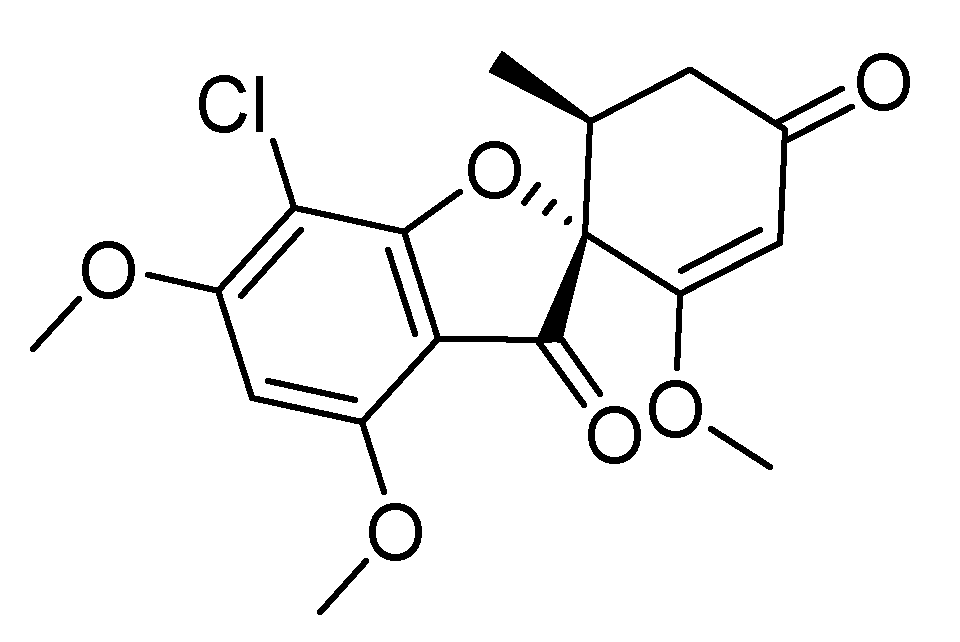

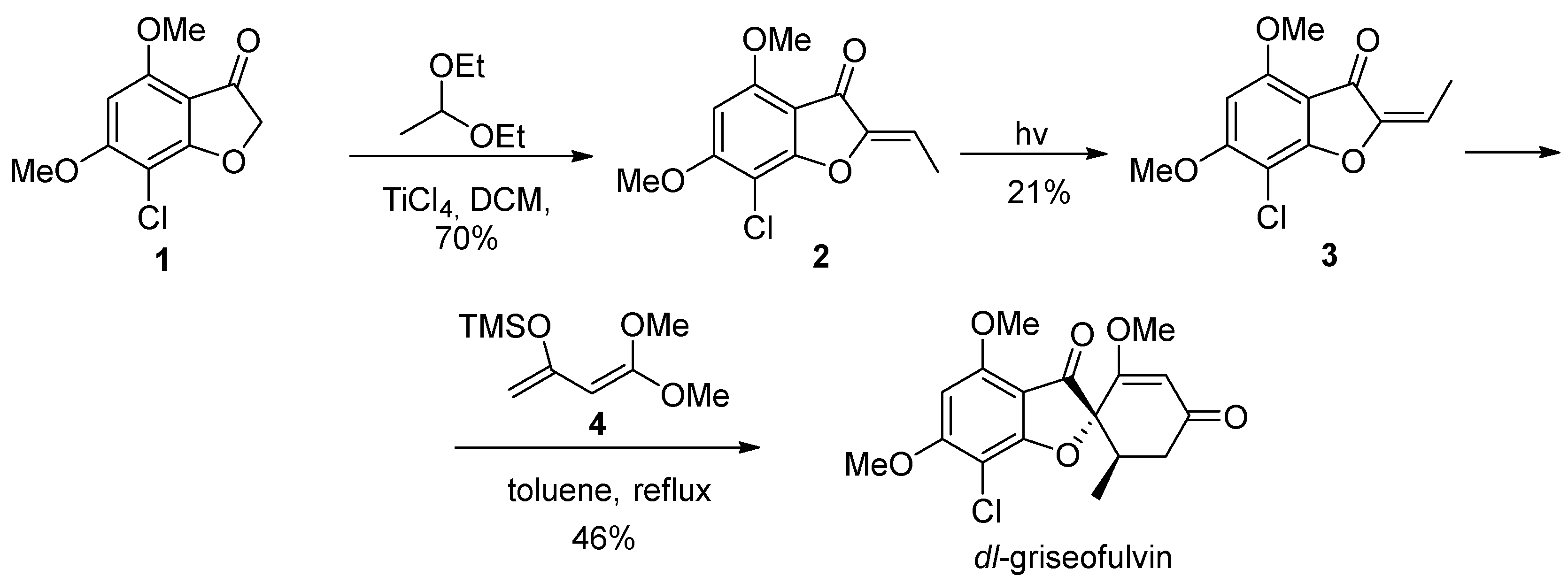

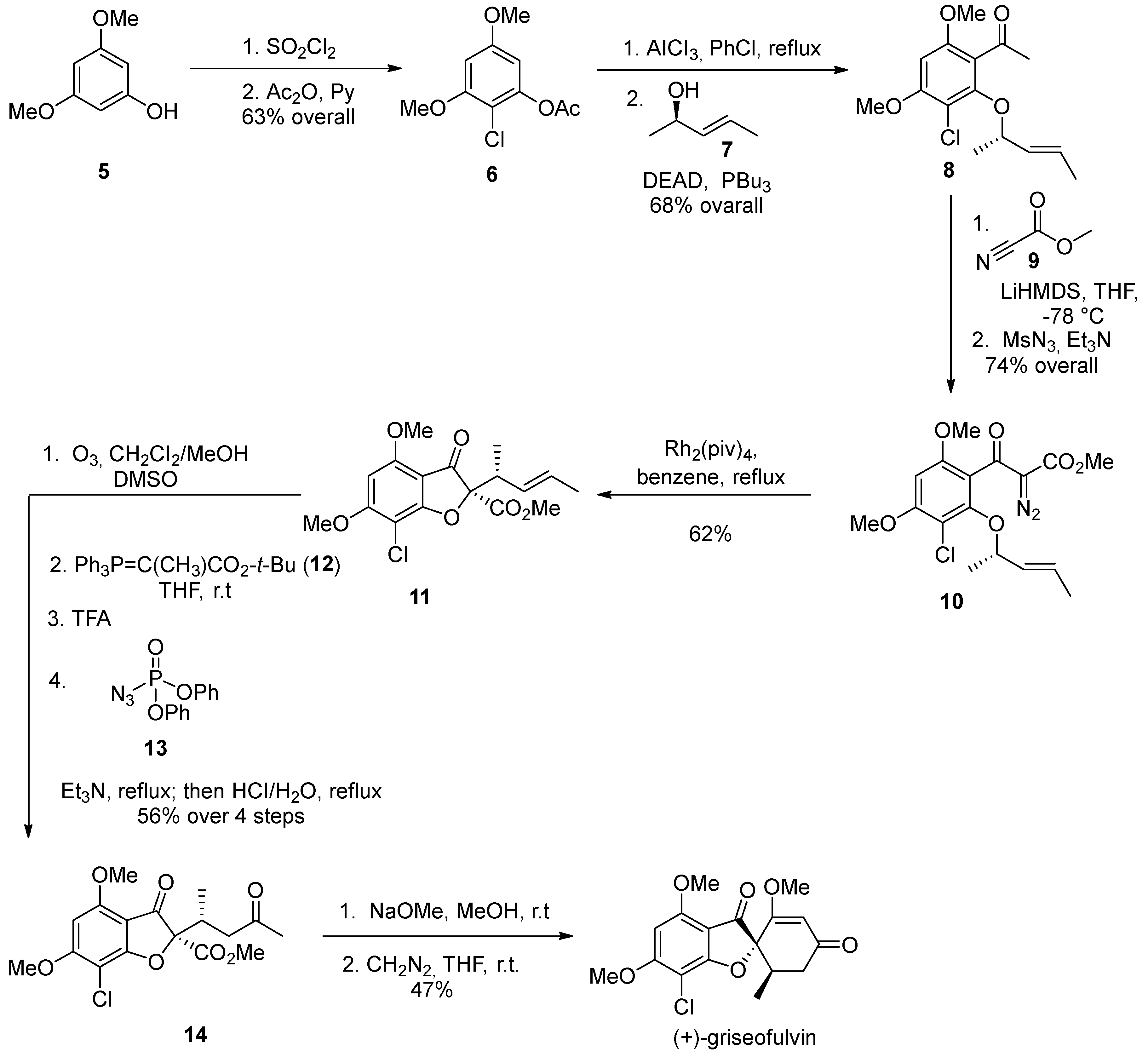

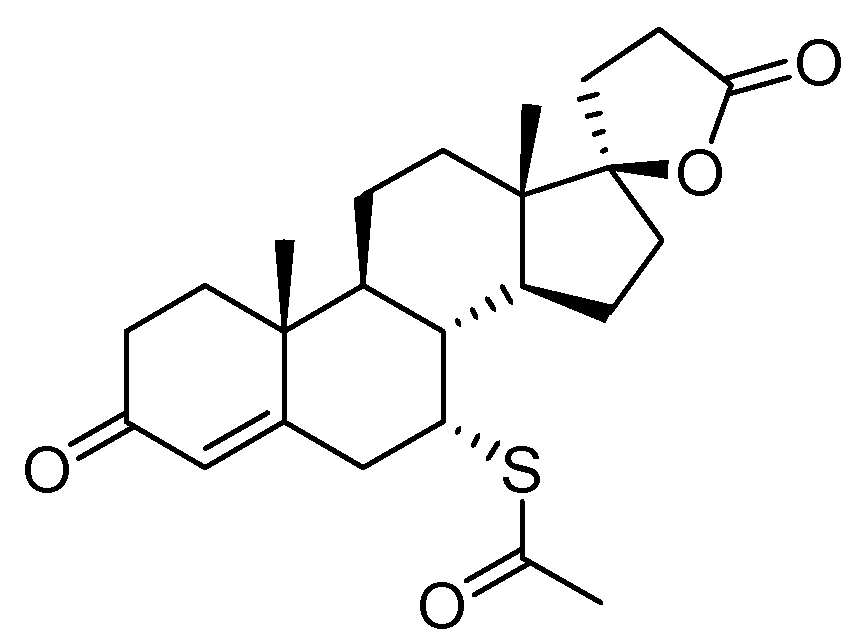

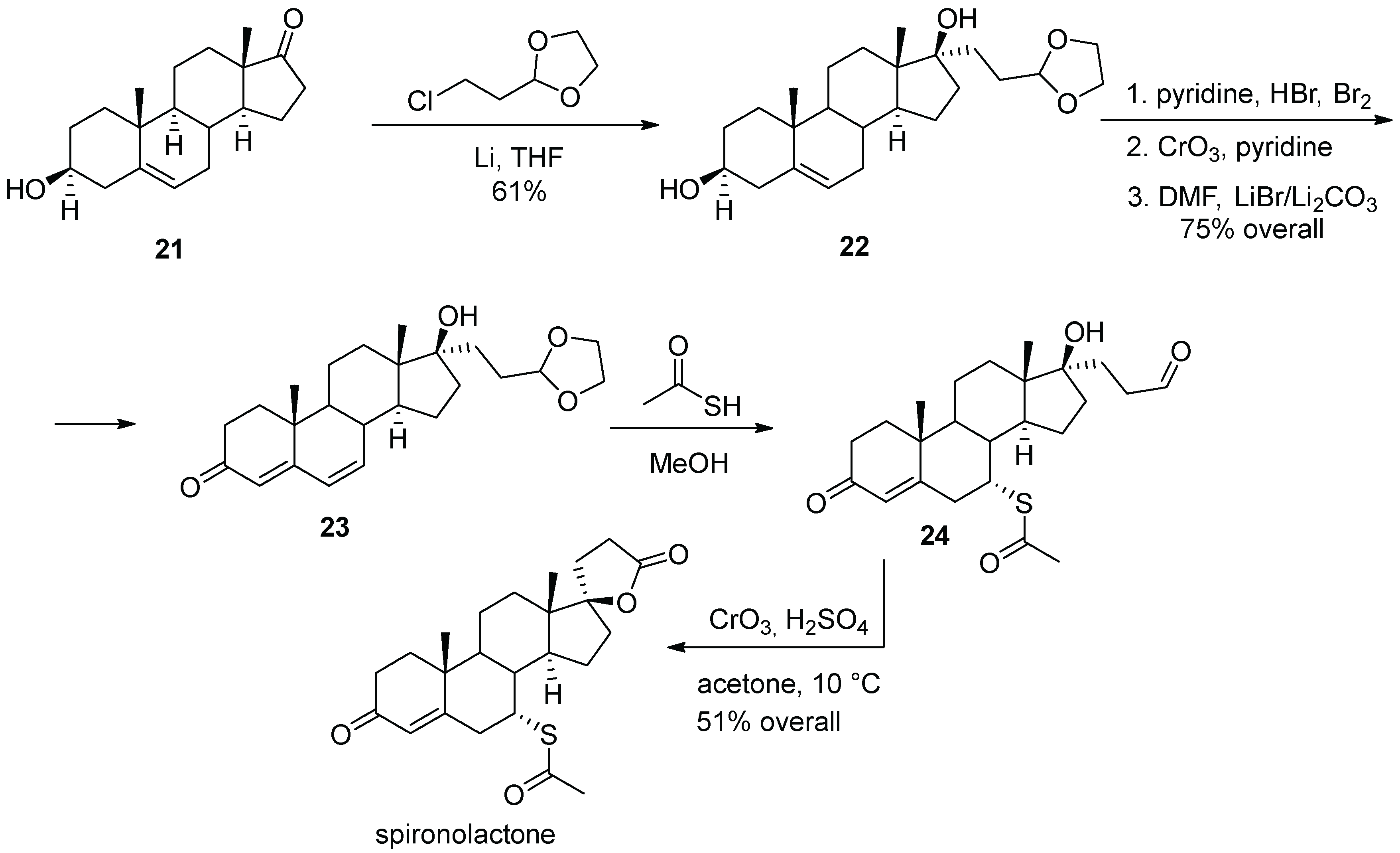

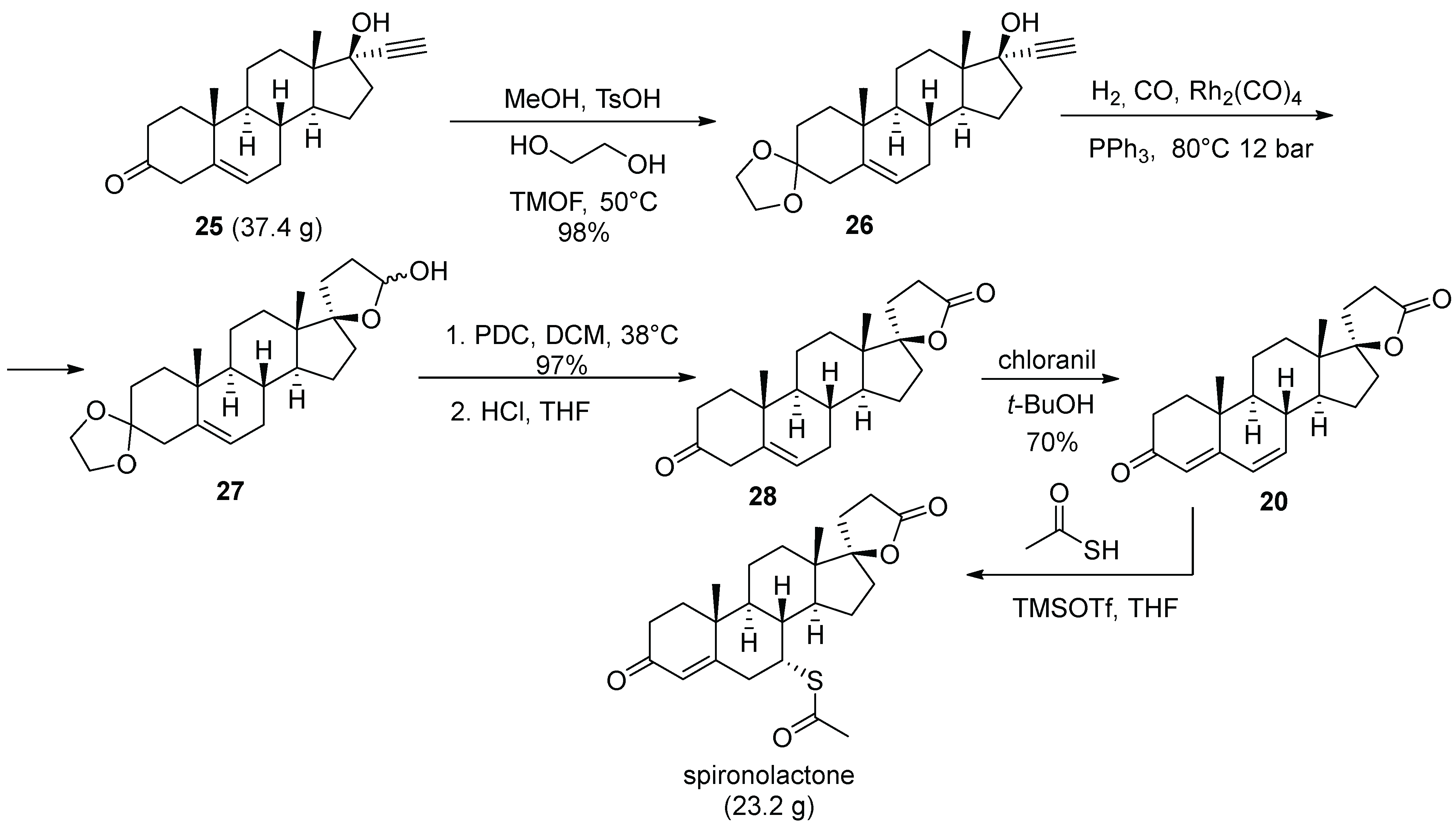

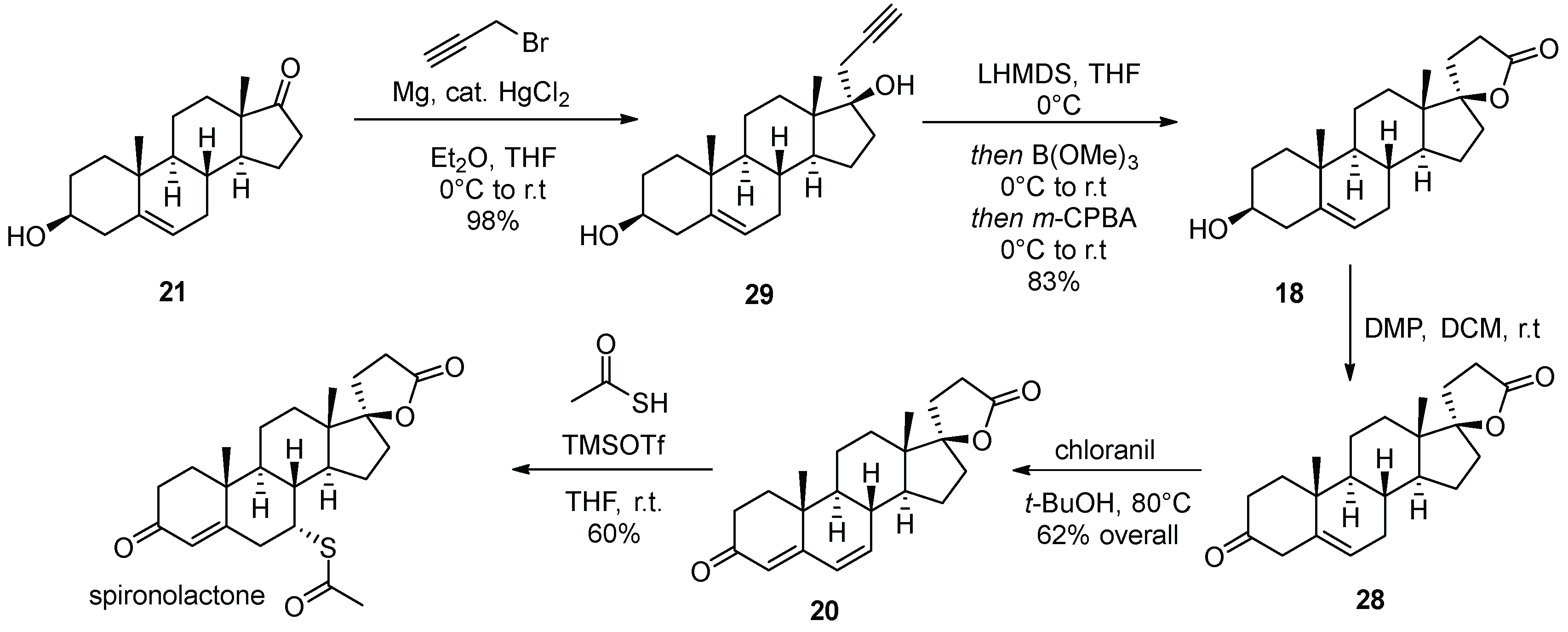

2. Griseofulvin

3. Spironolactone

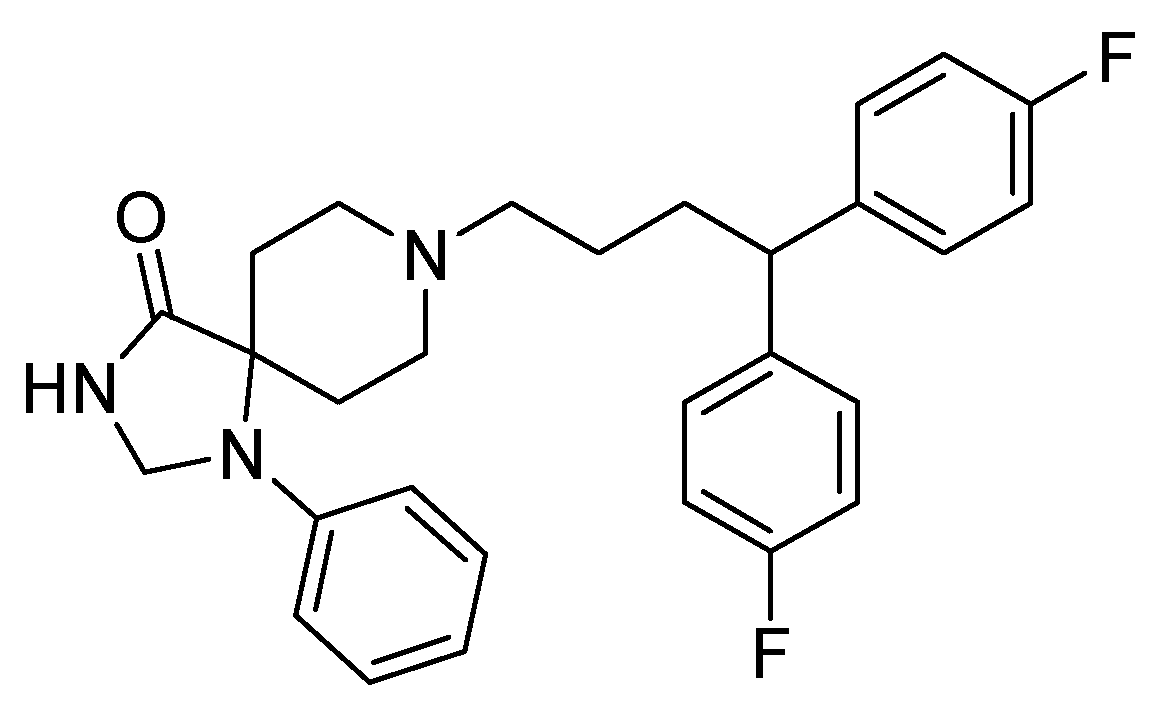

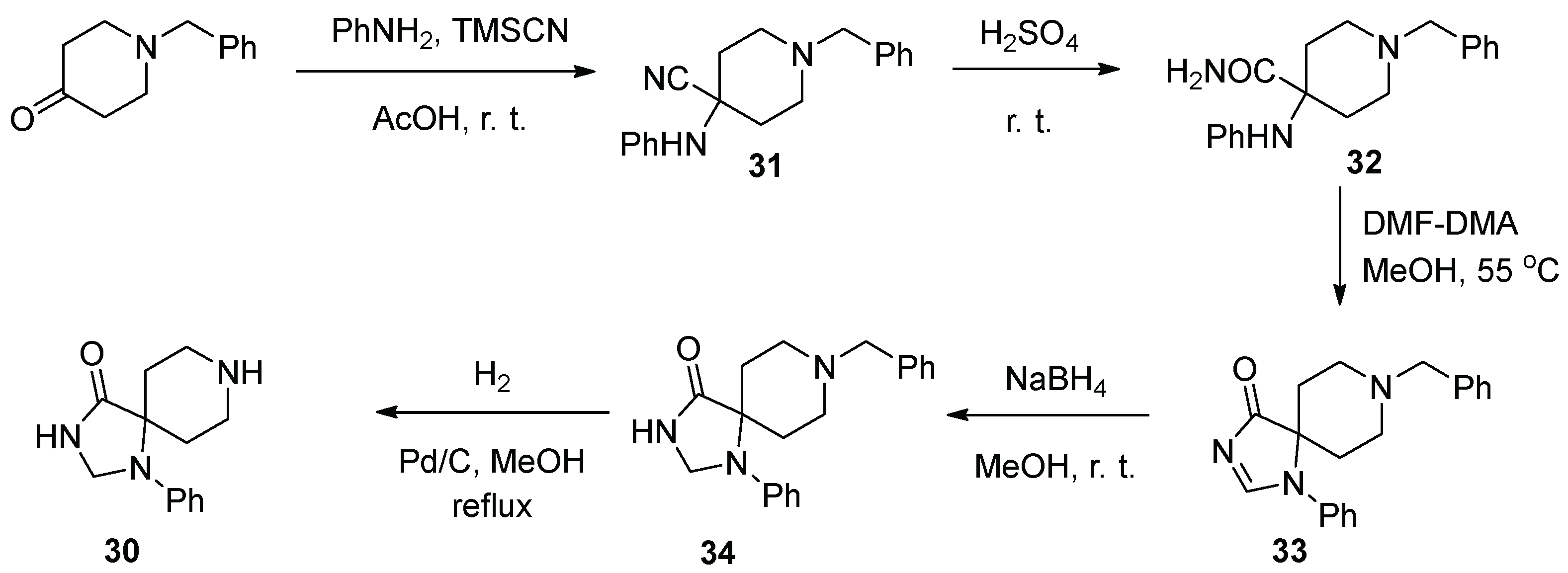

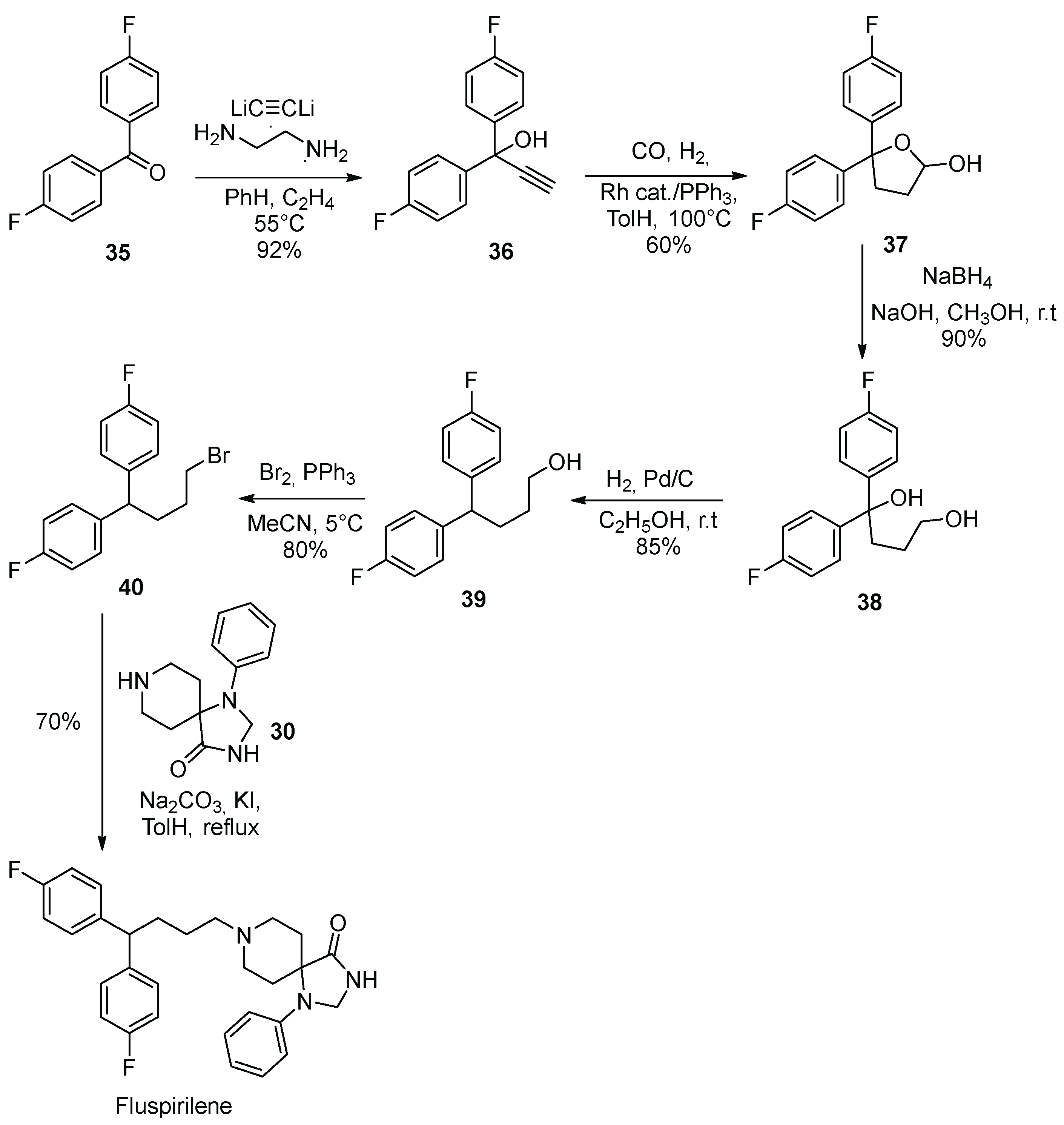

4. Fluspirilene

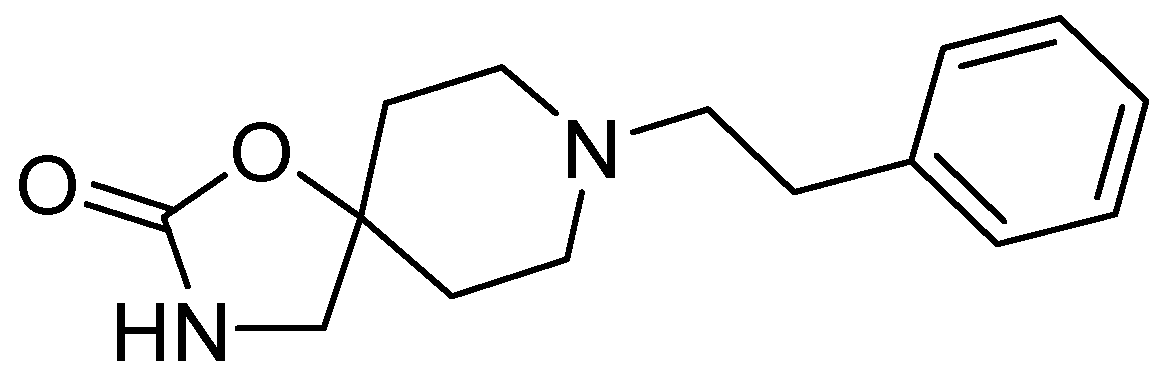

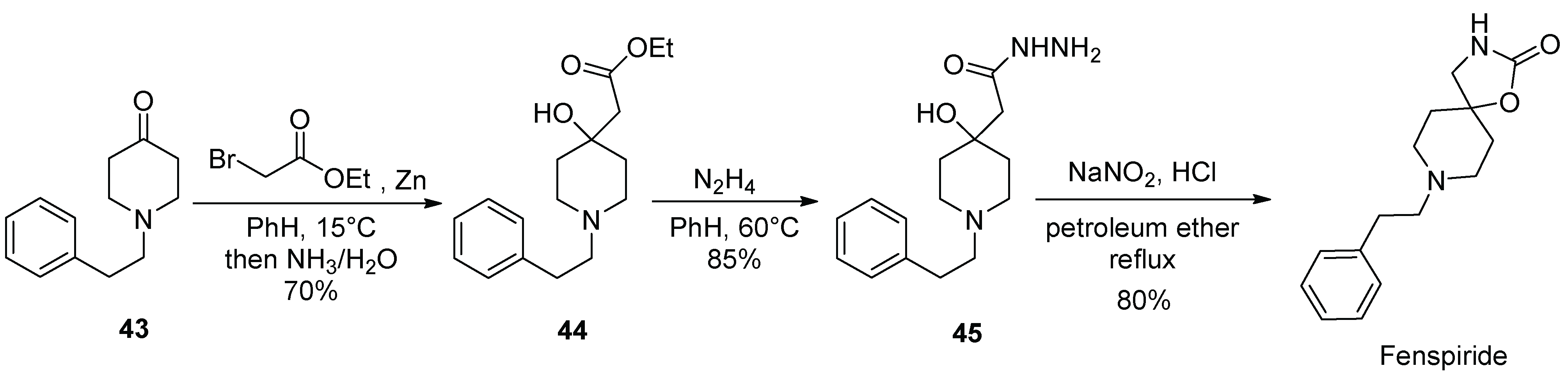

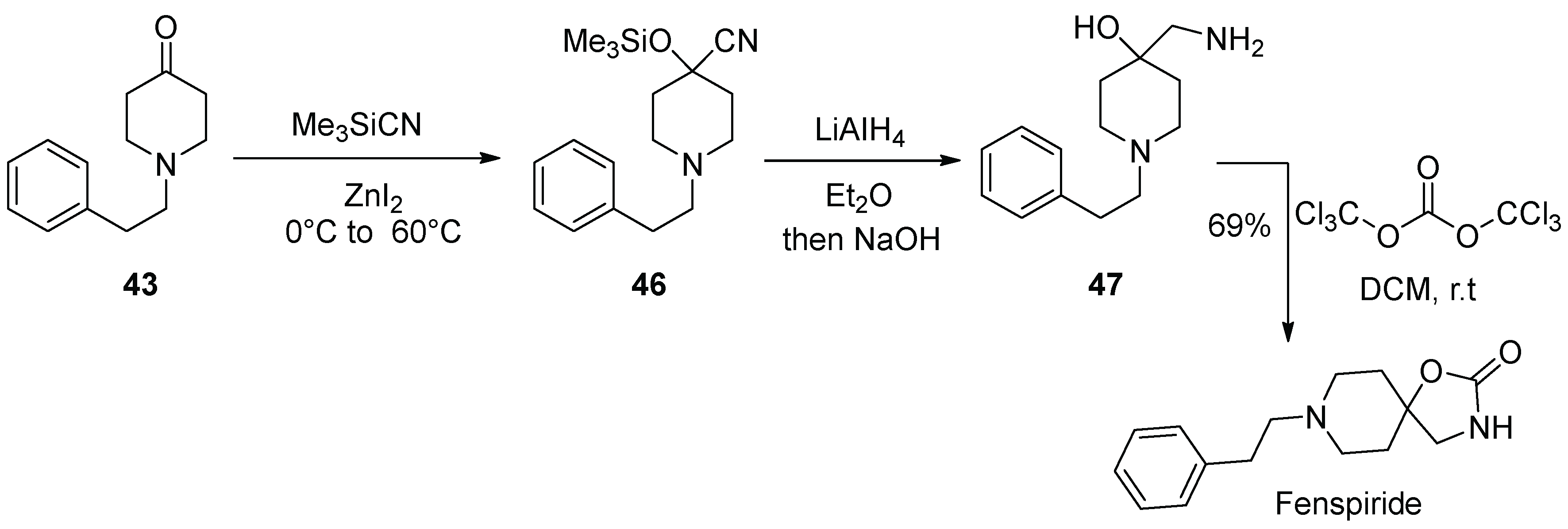

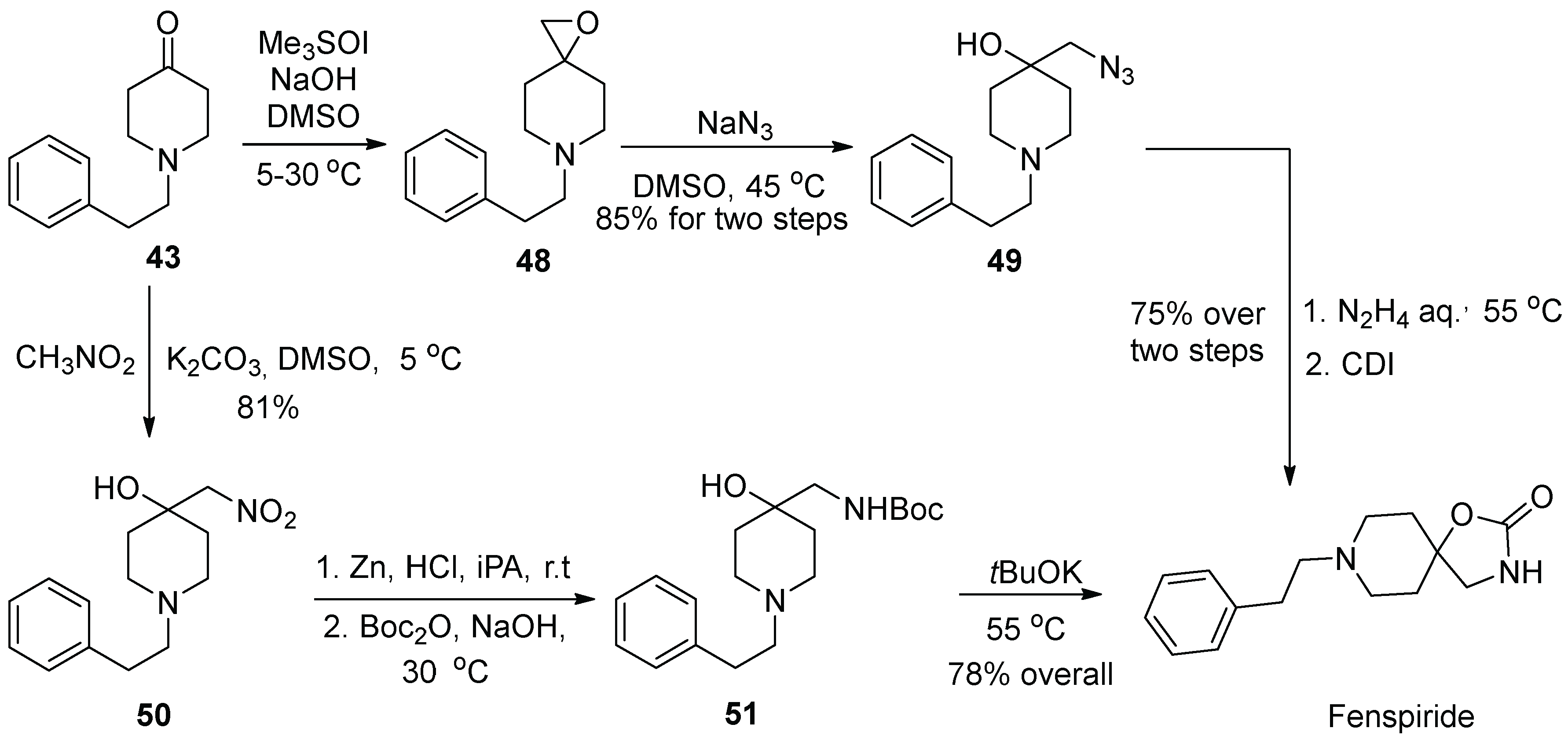

5. Fenspiride

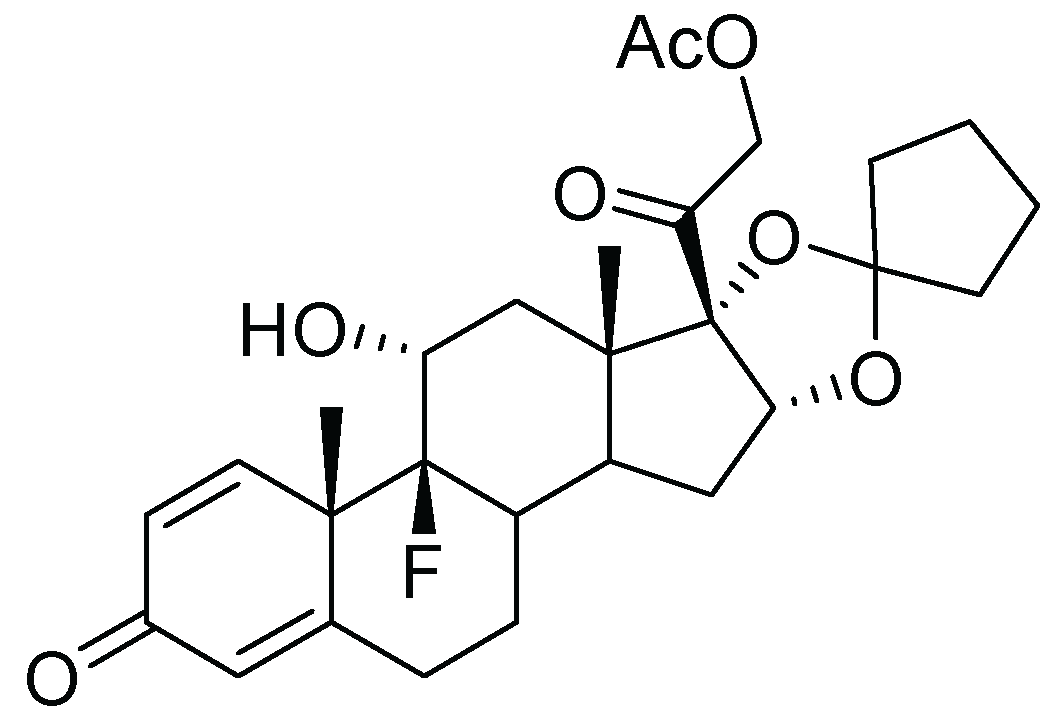

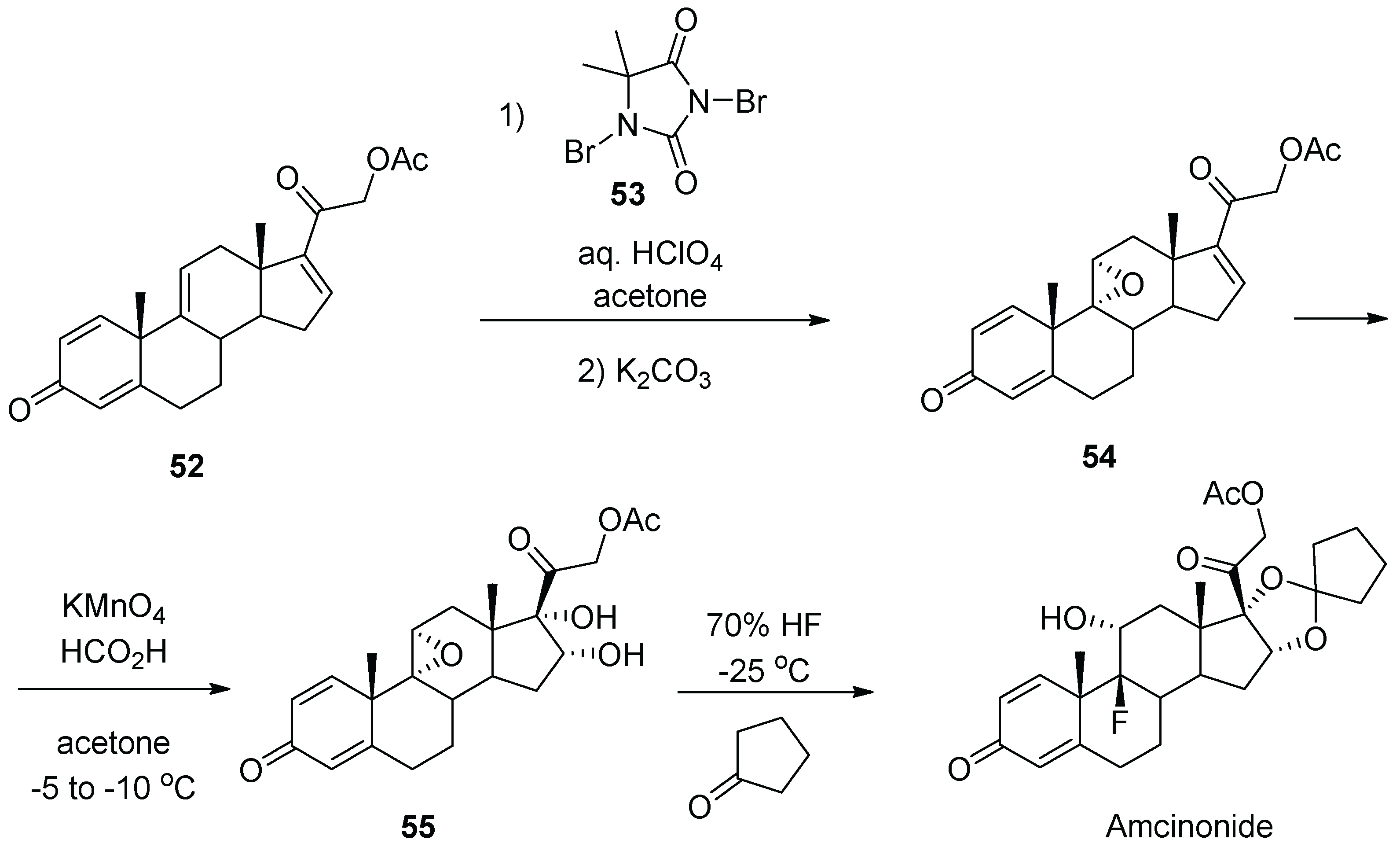

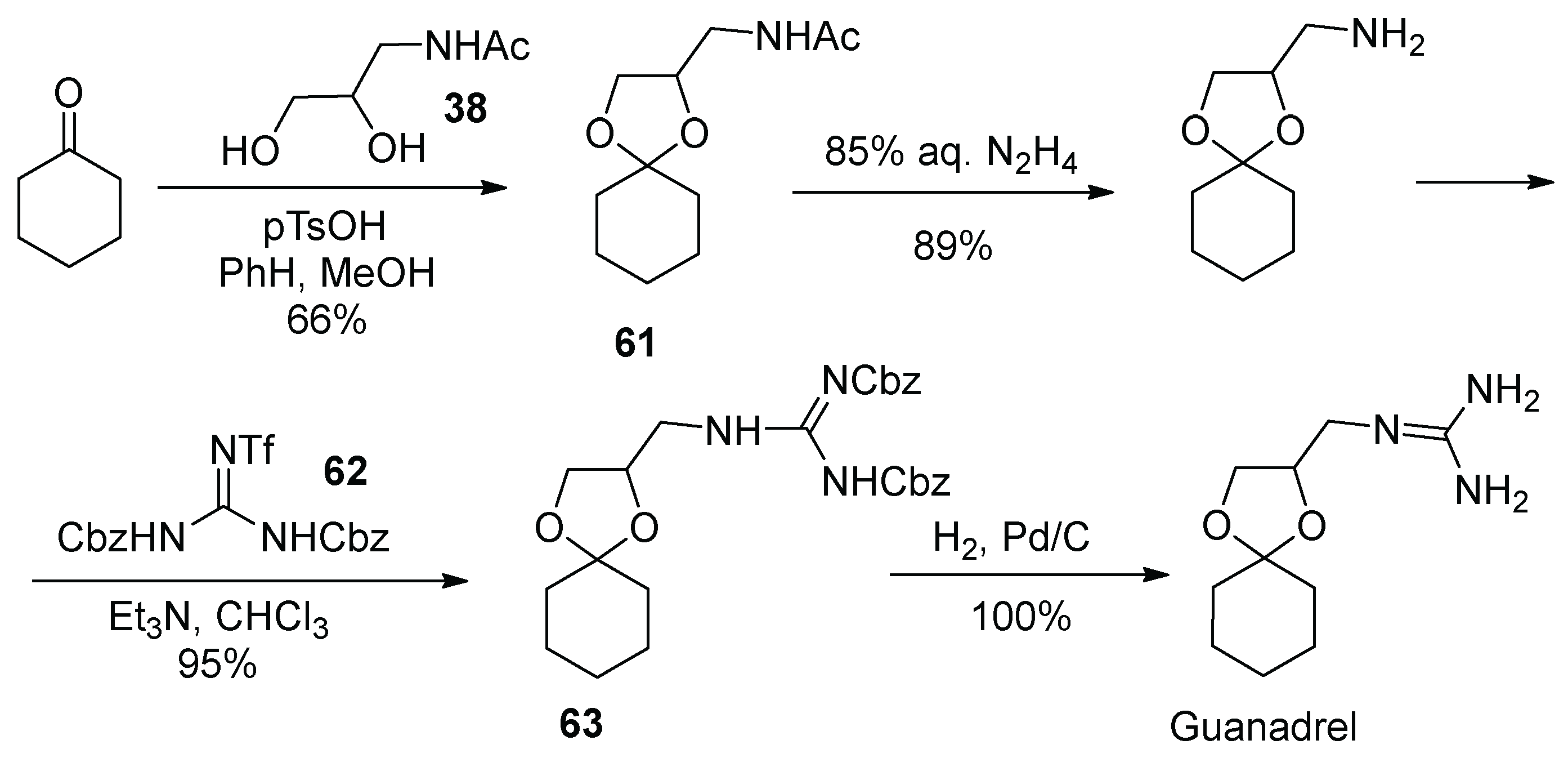

6. Amcinonide

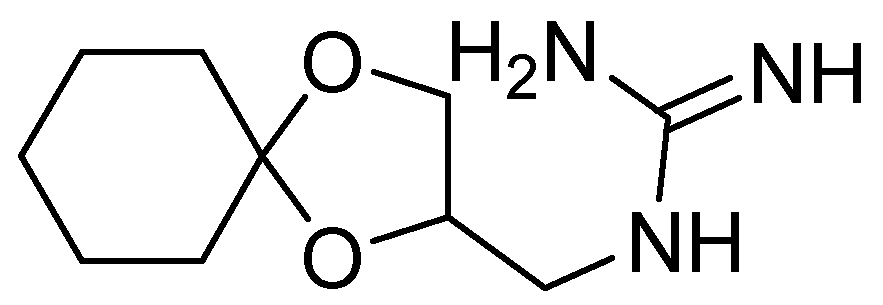

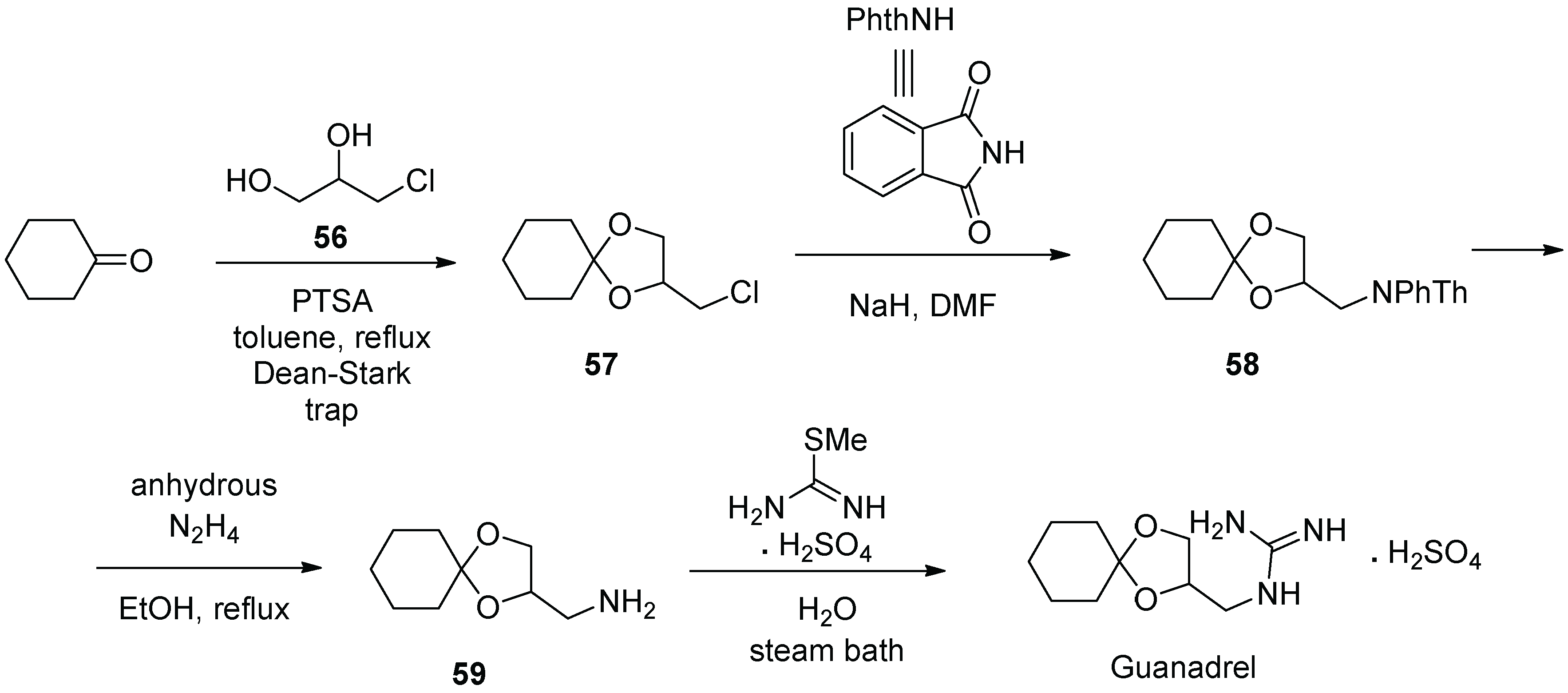

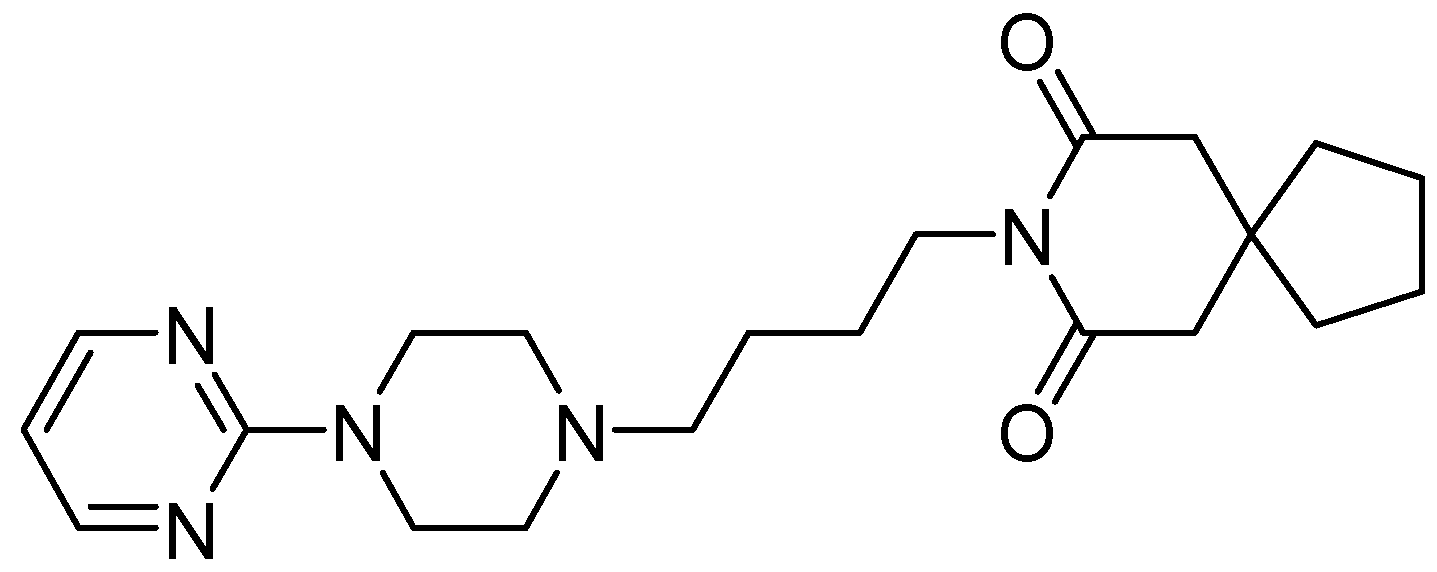

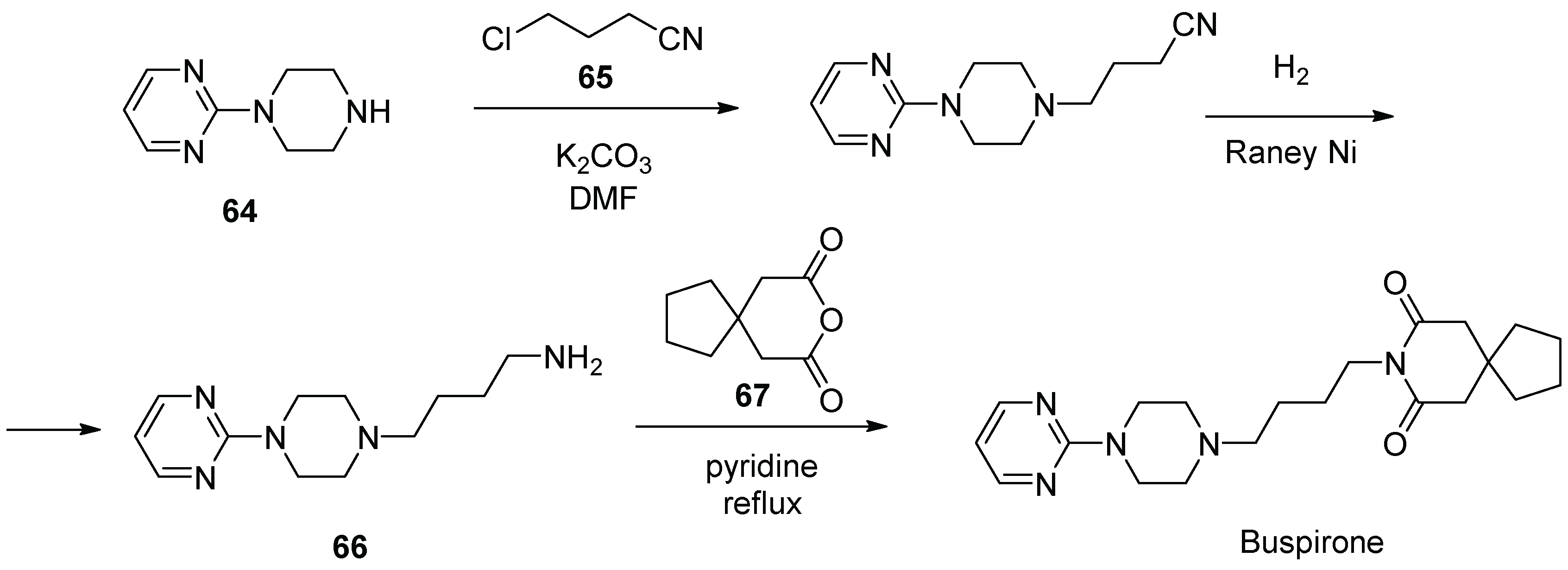

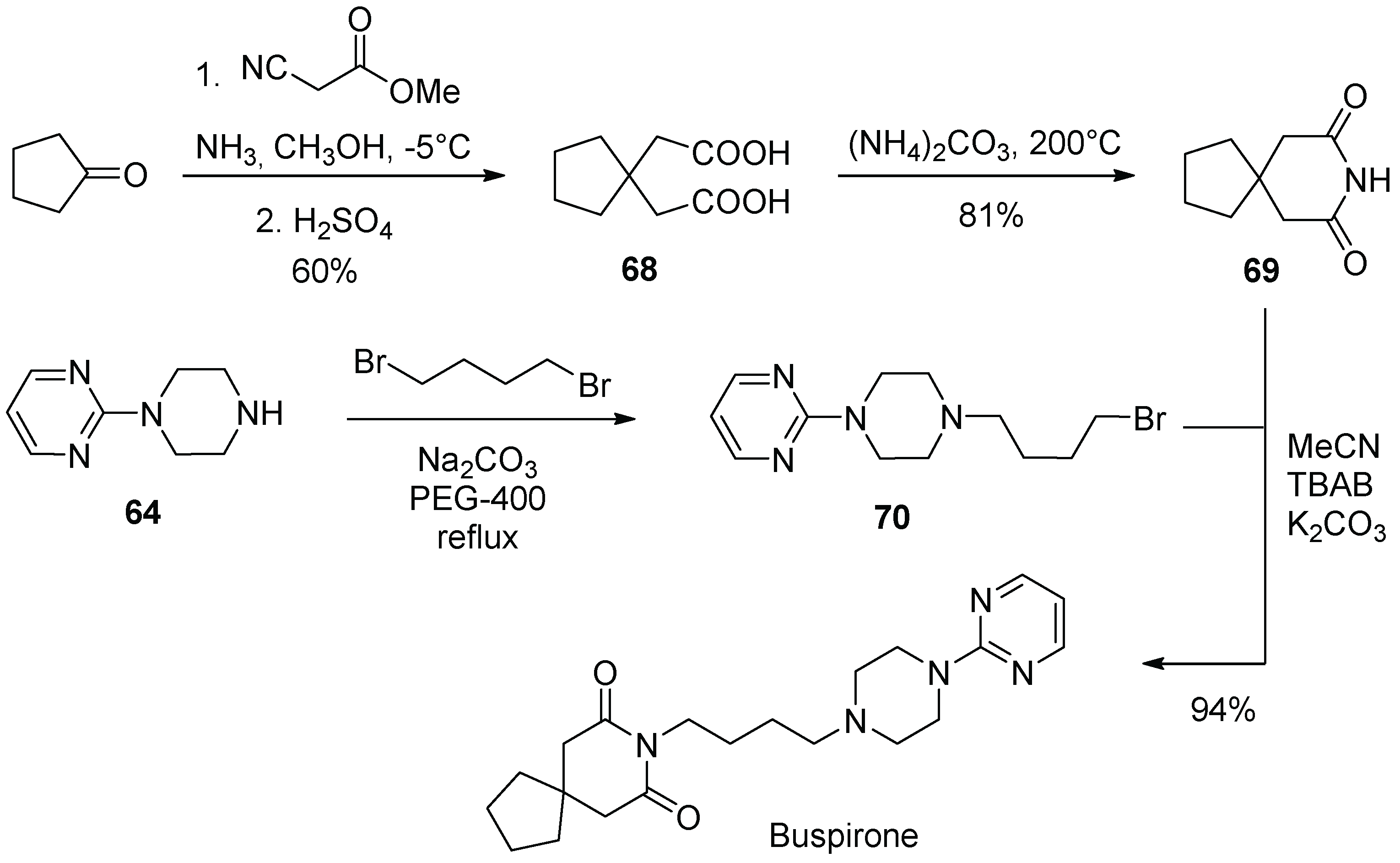

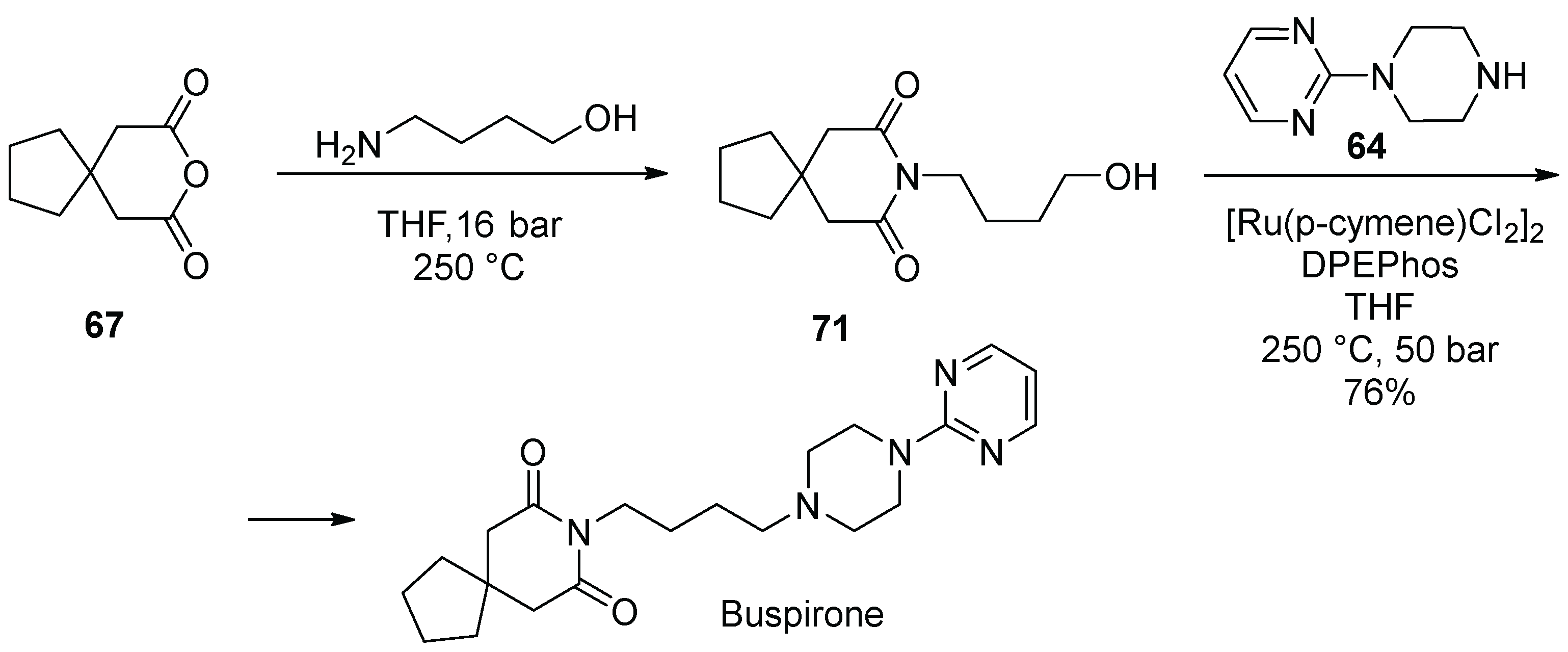

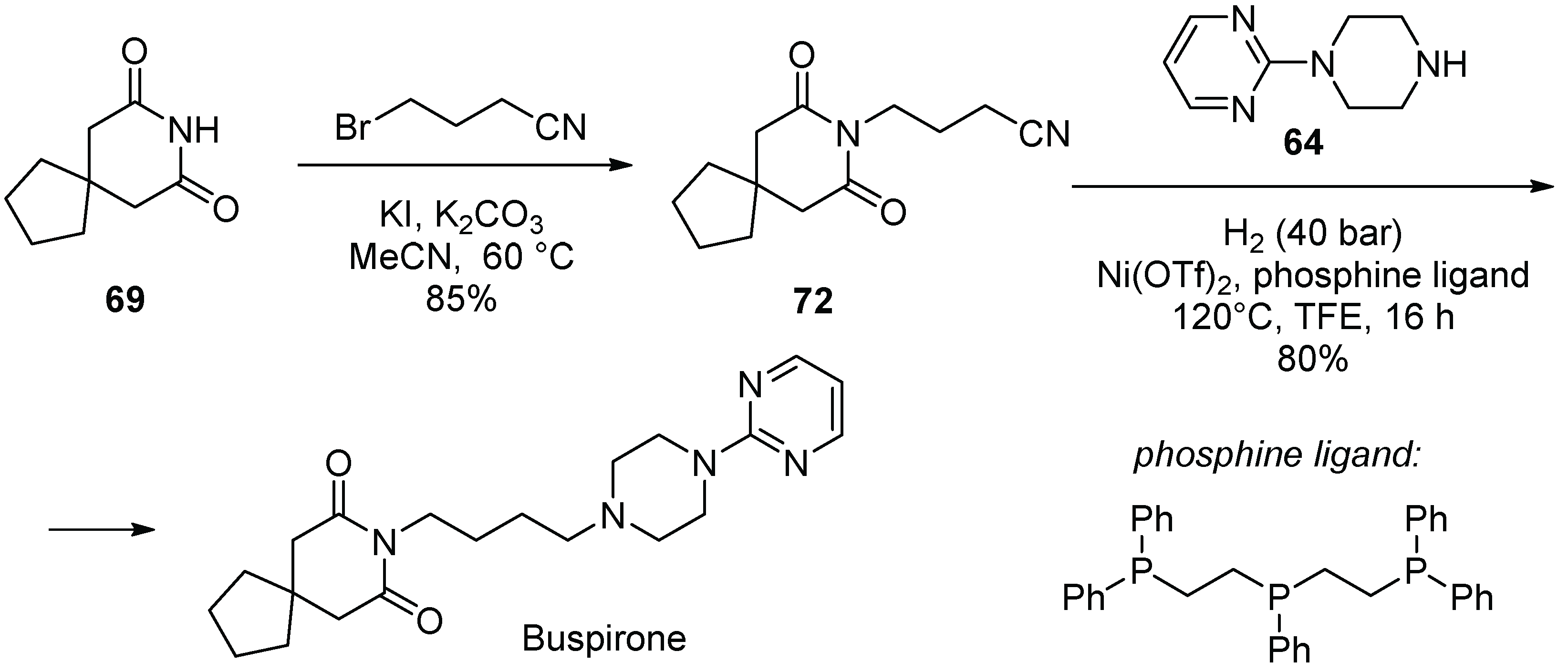

7. Guanadrel

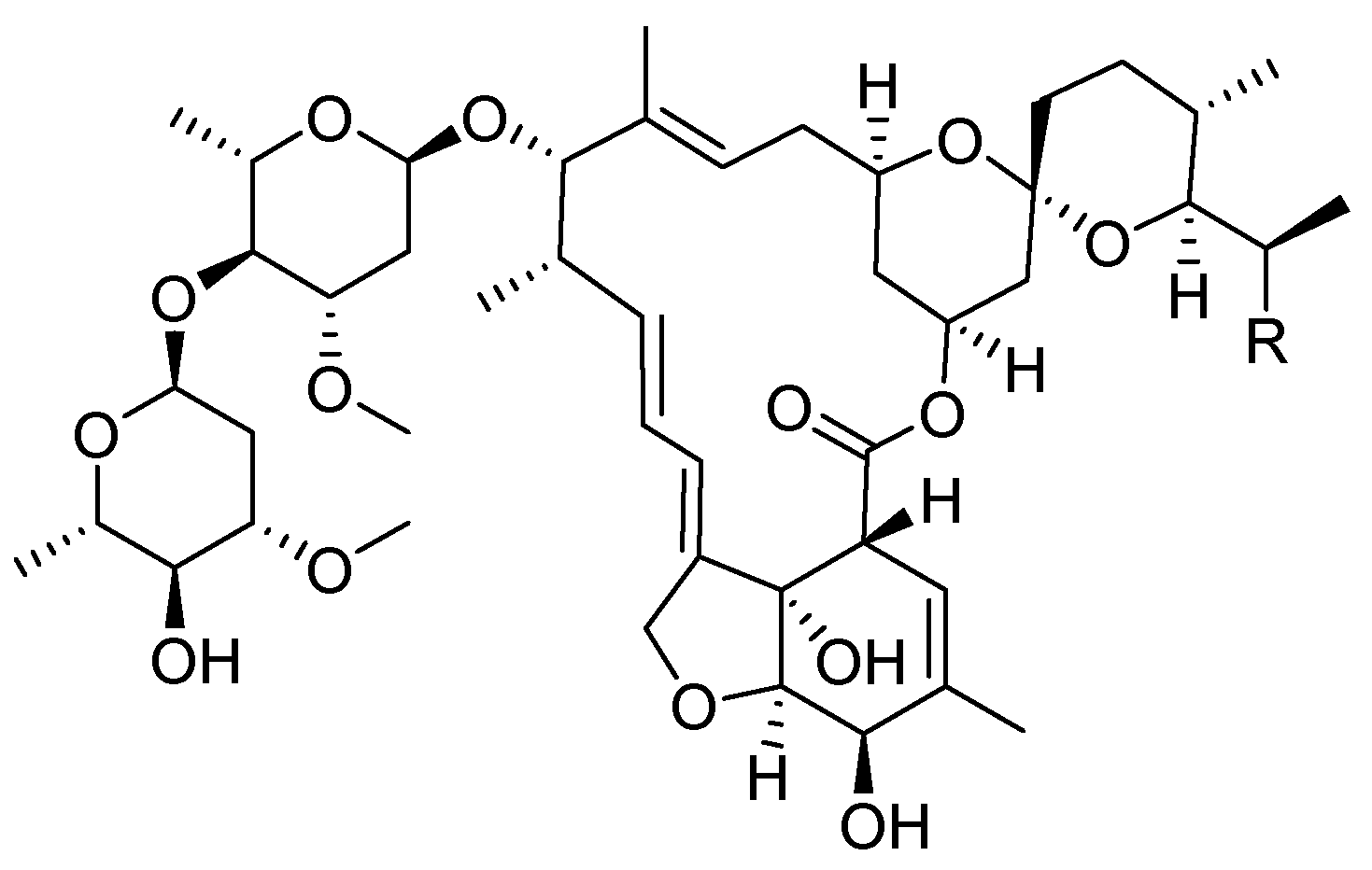

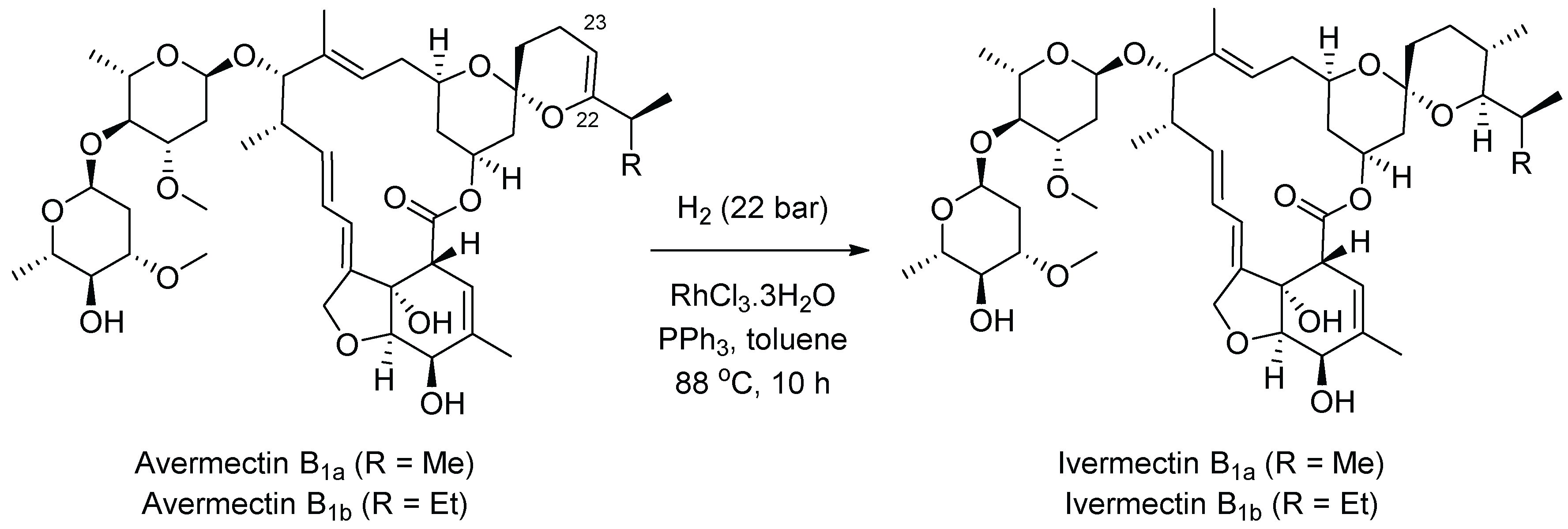

8. Buspirone

9. Ivermectin

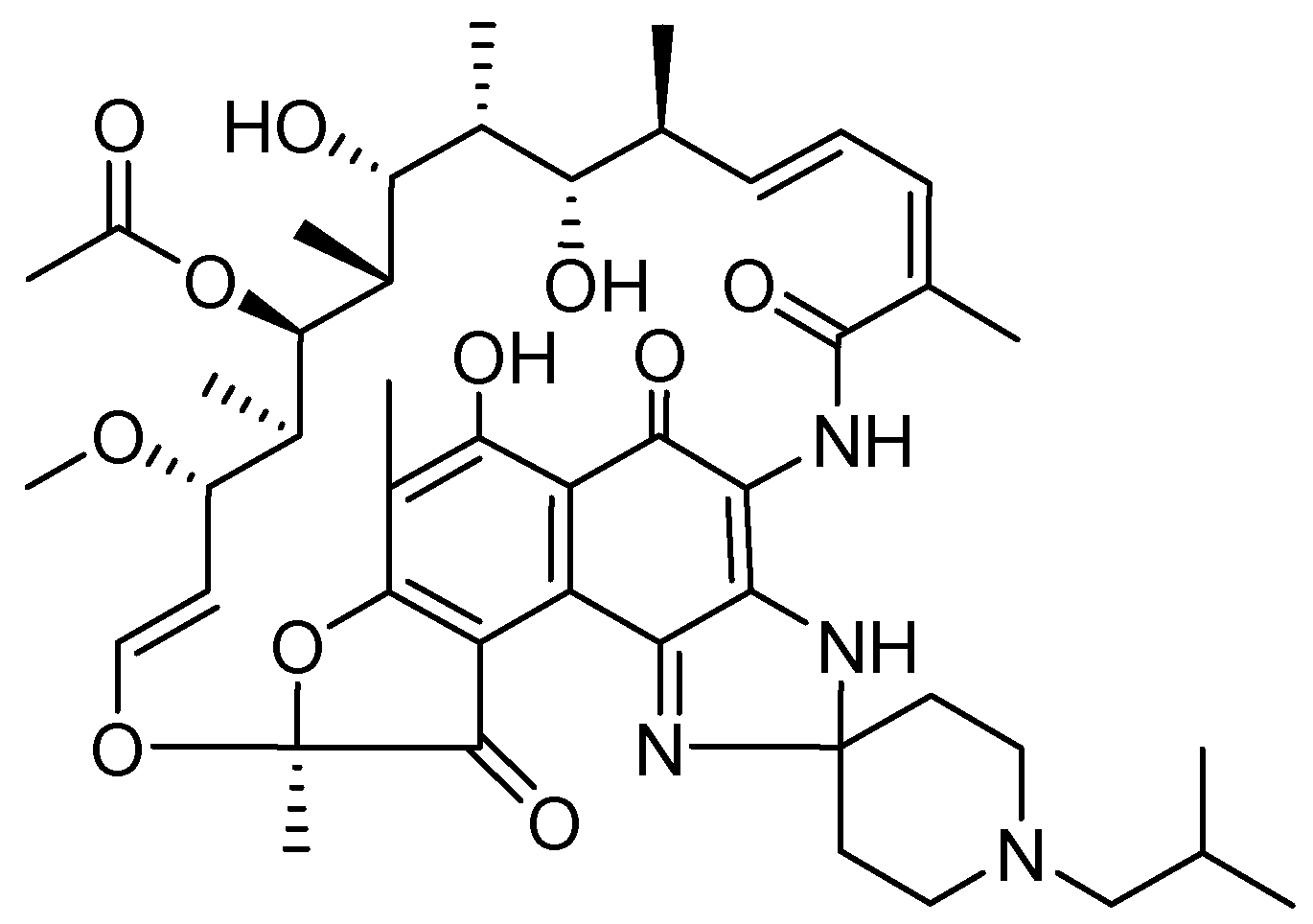

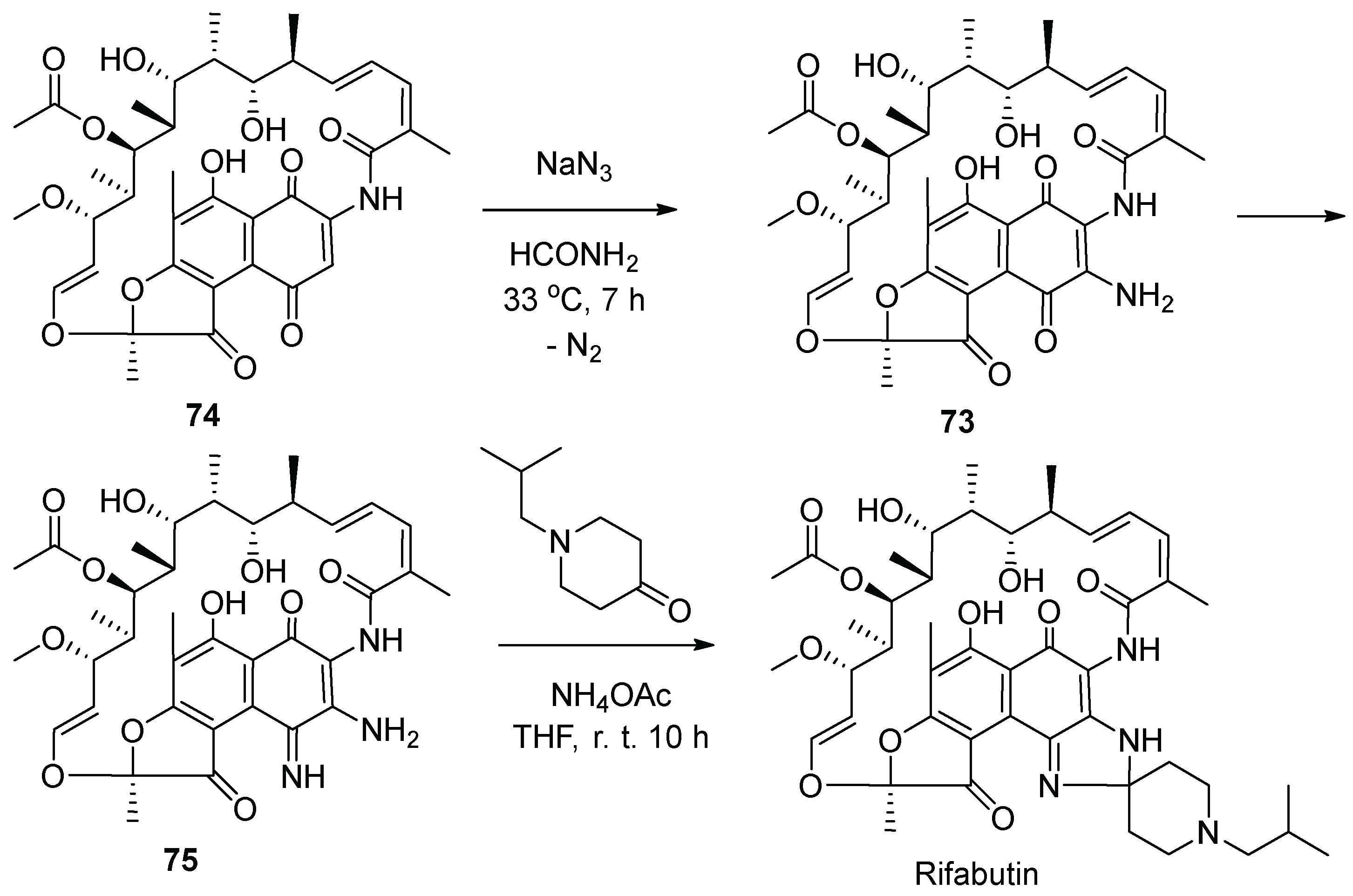

10. Rifabutin

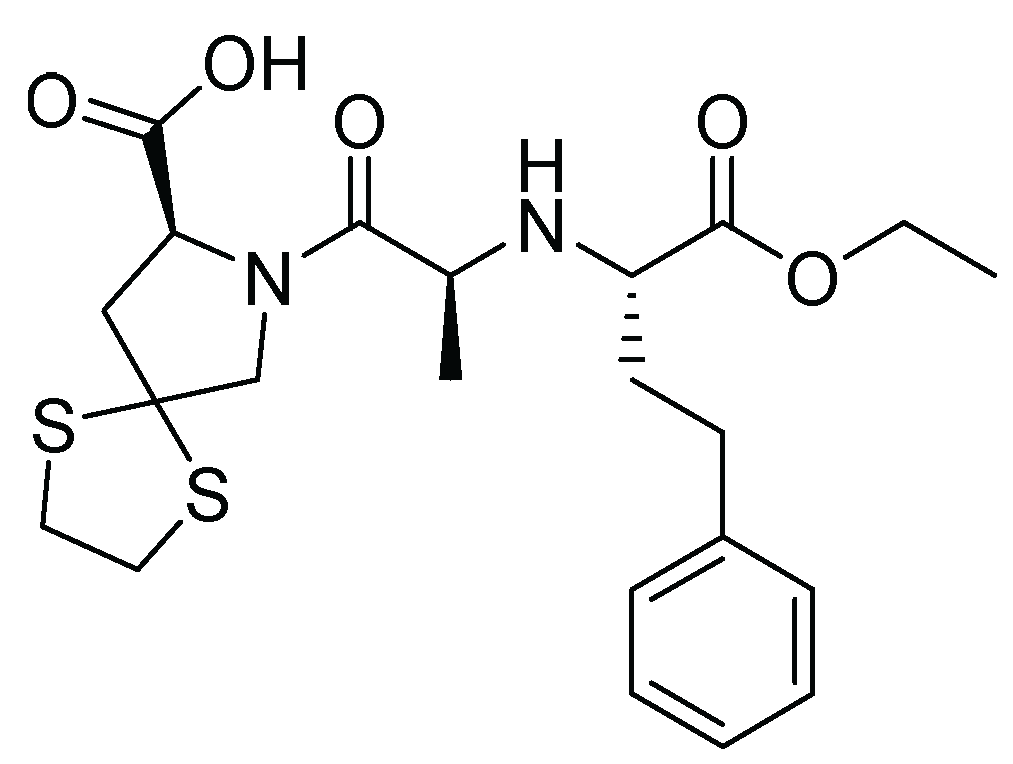

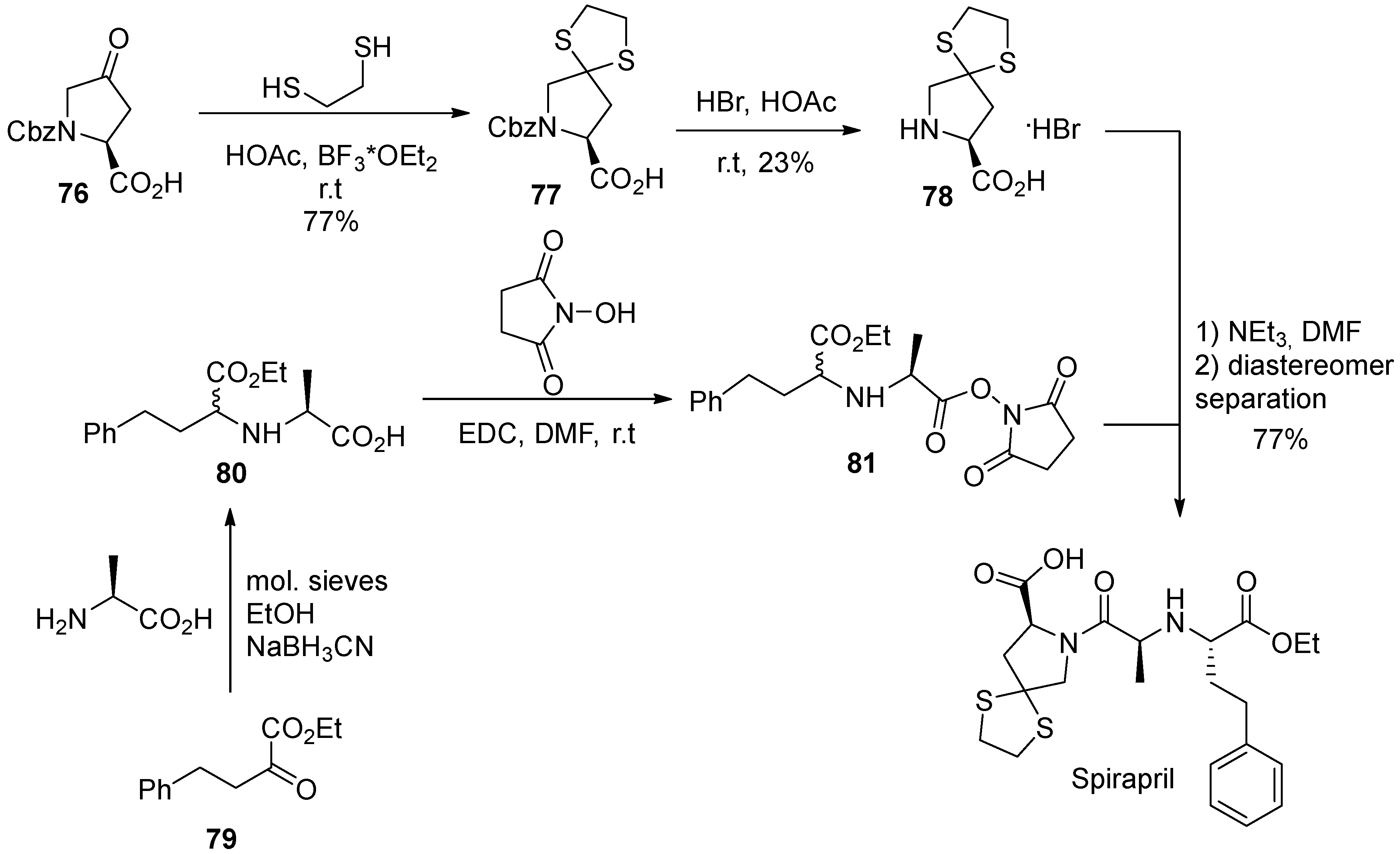

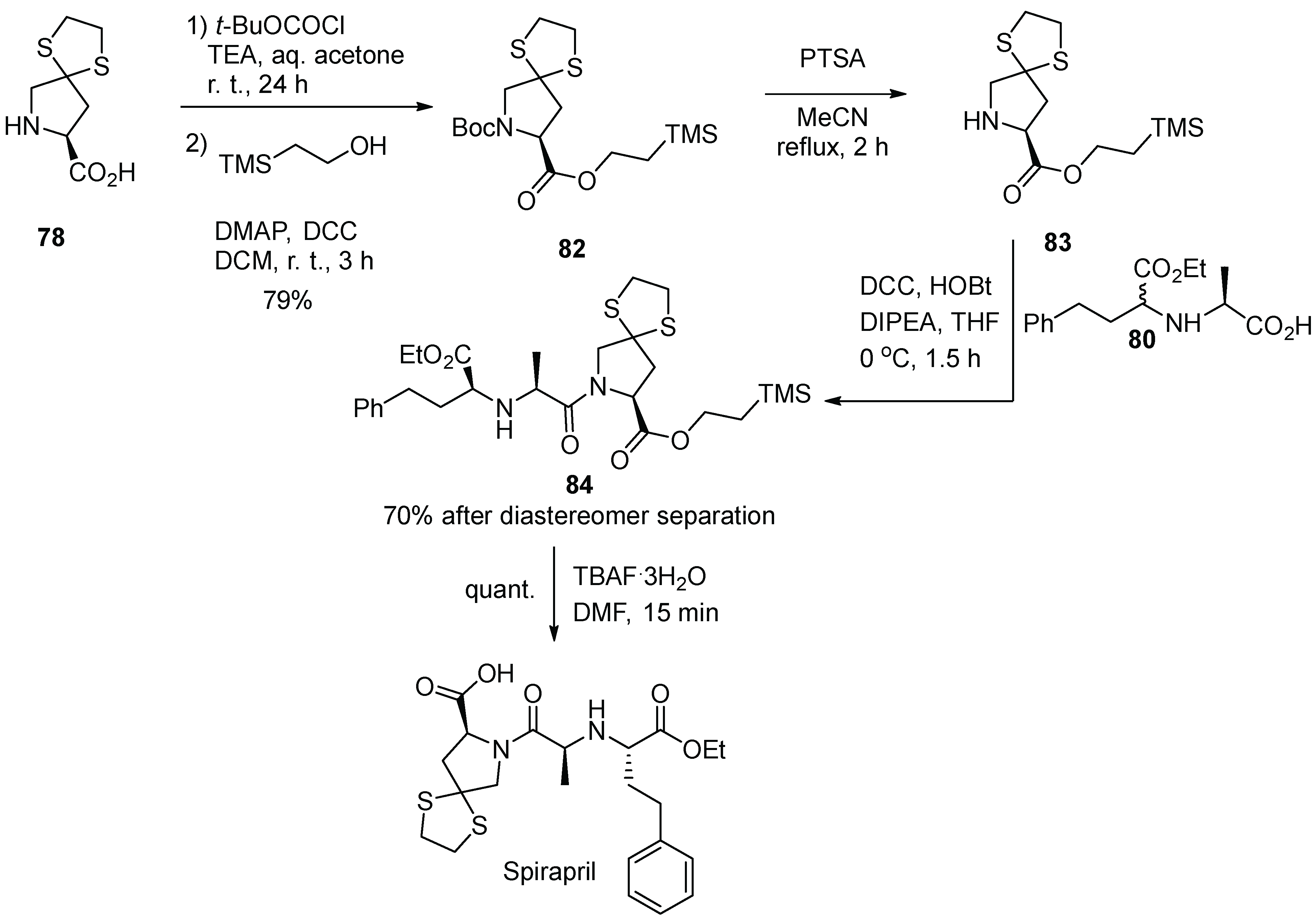

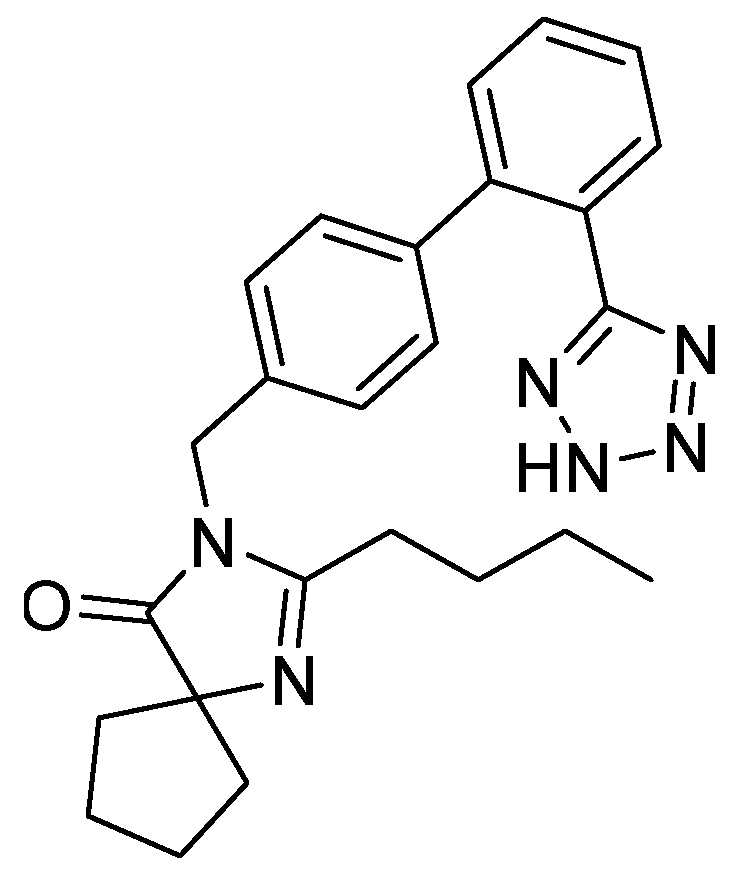

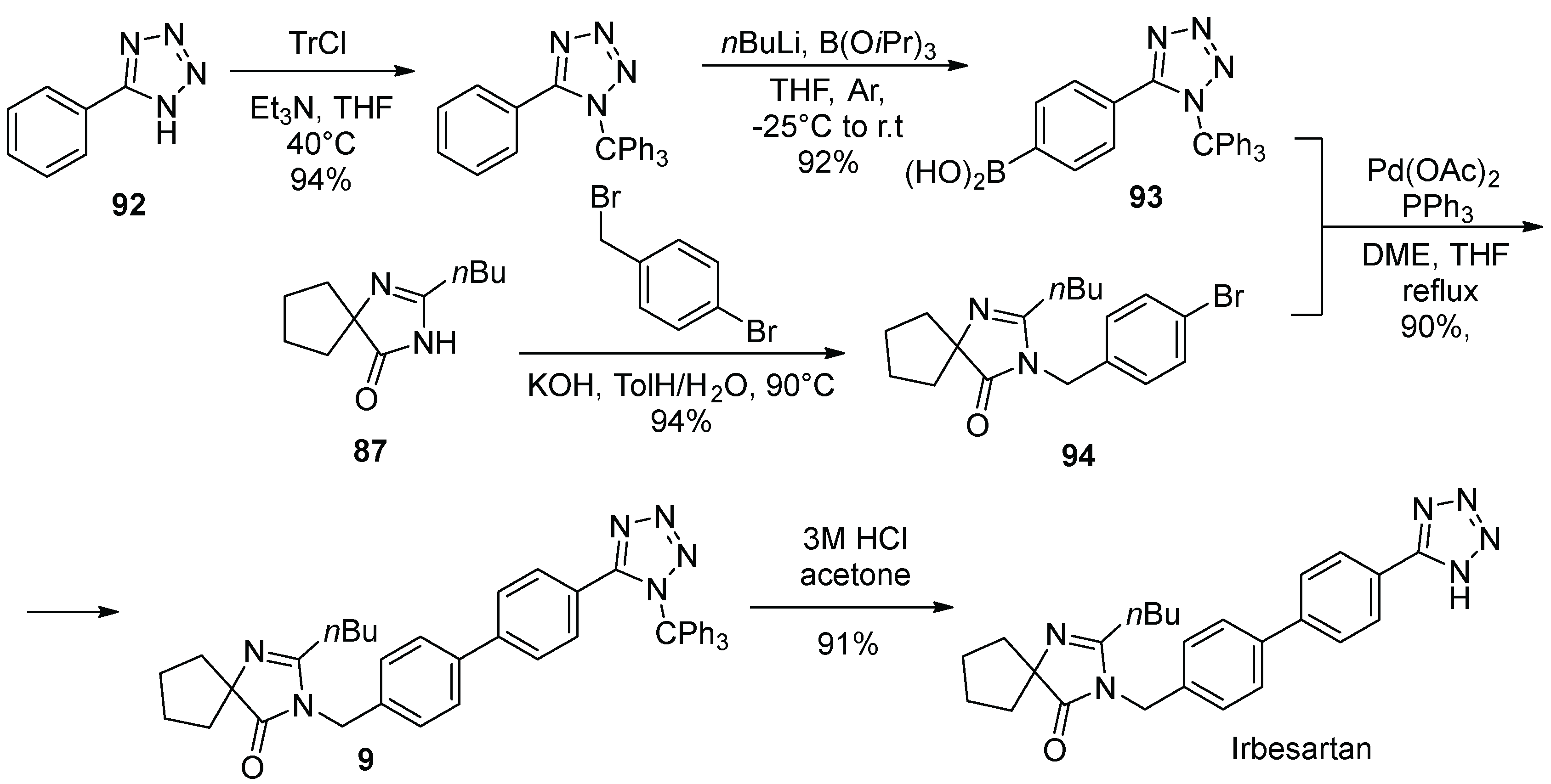

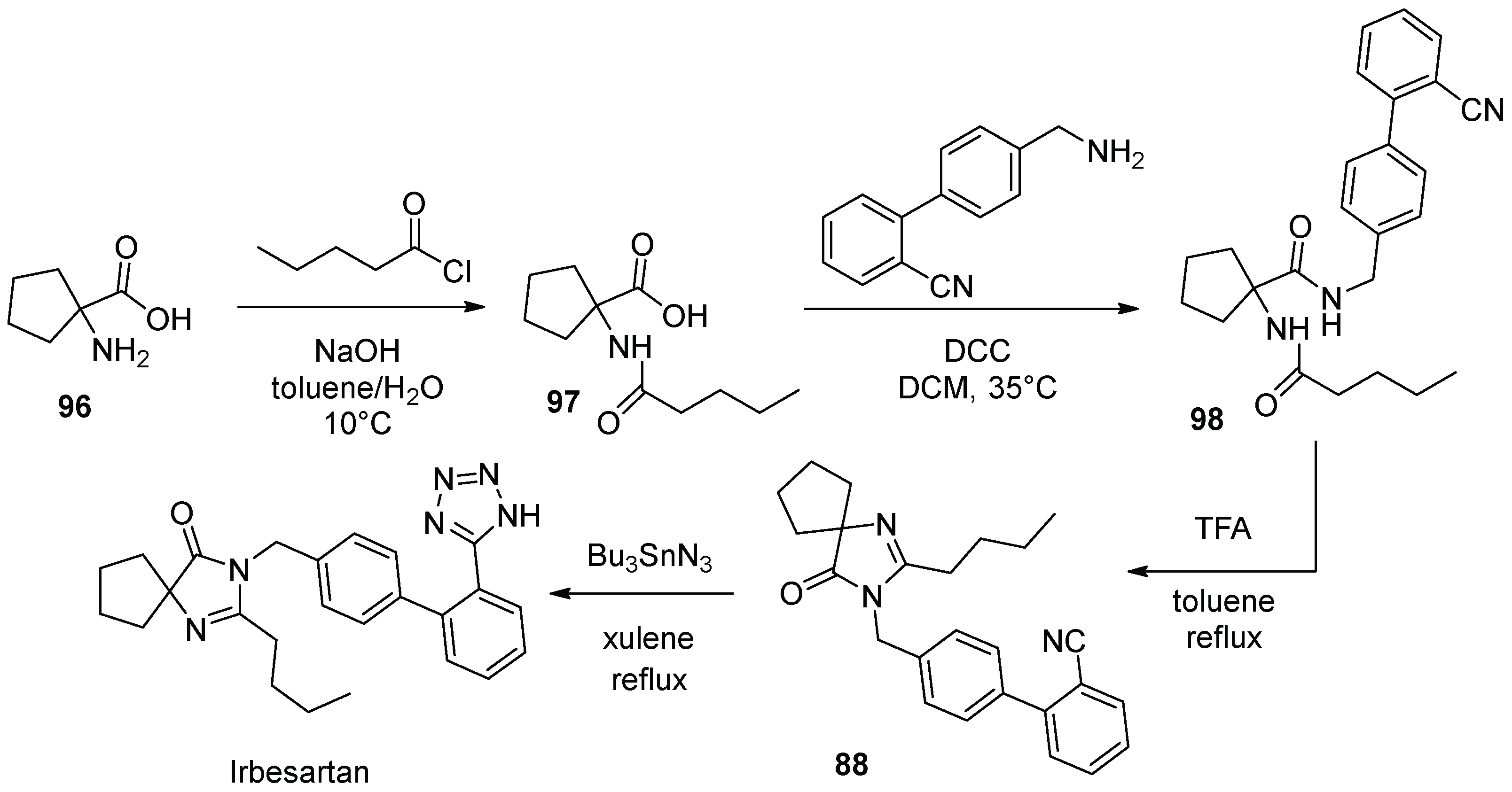

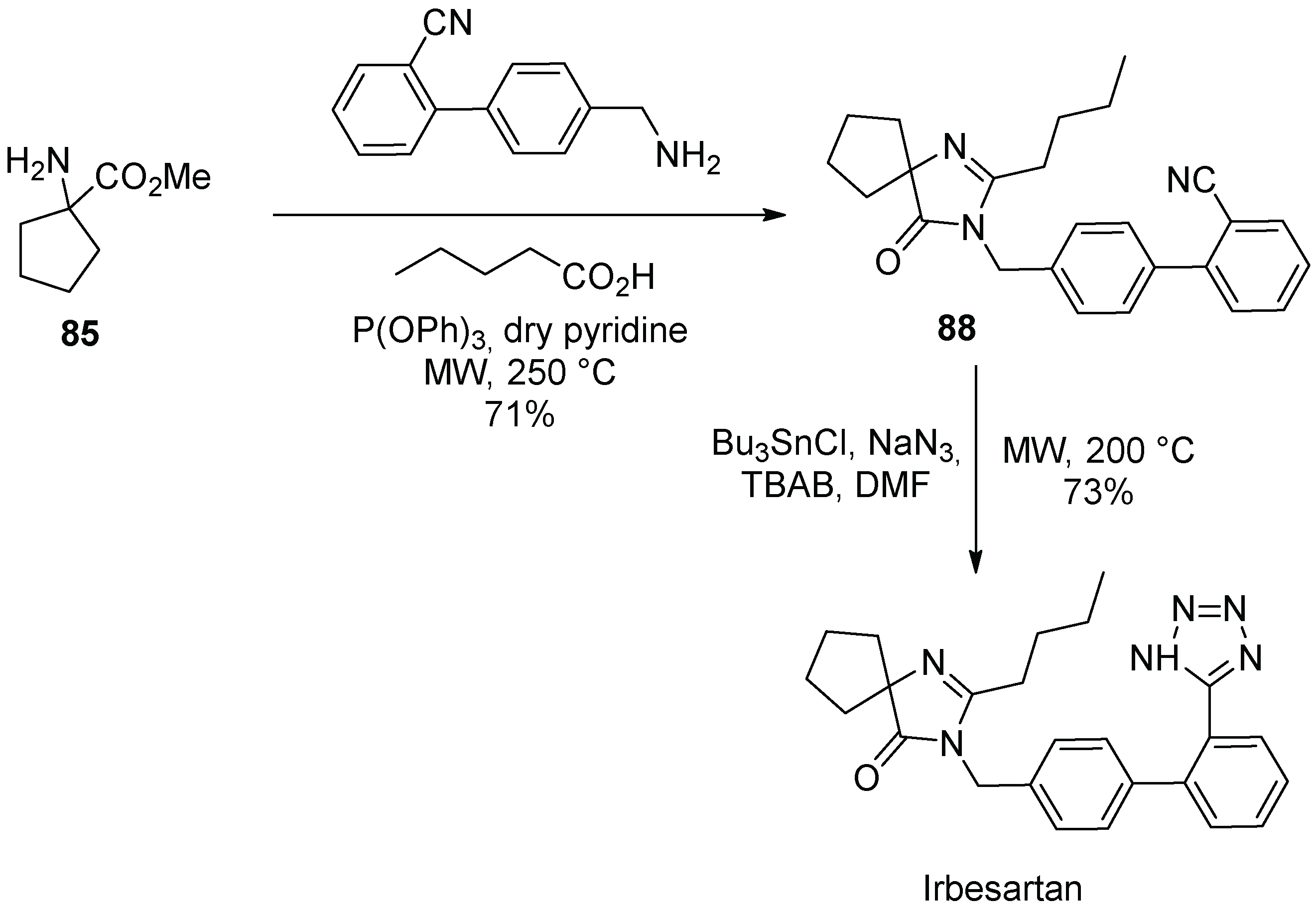

11. Spirapril

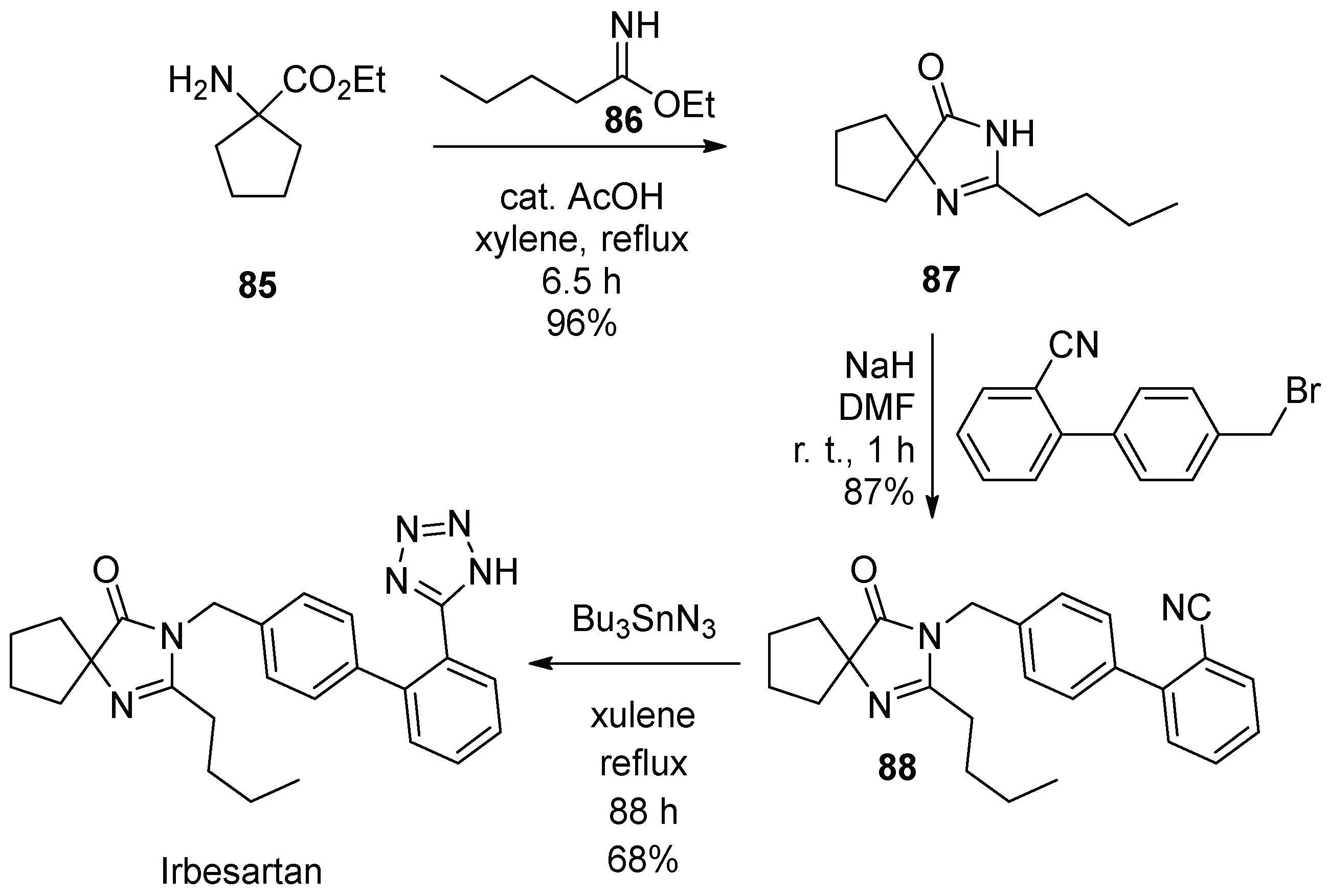

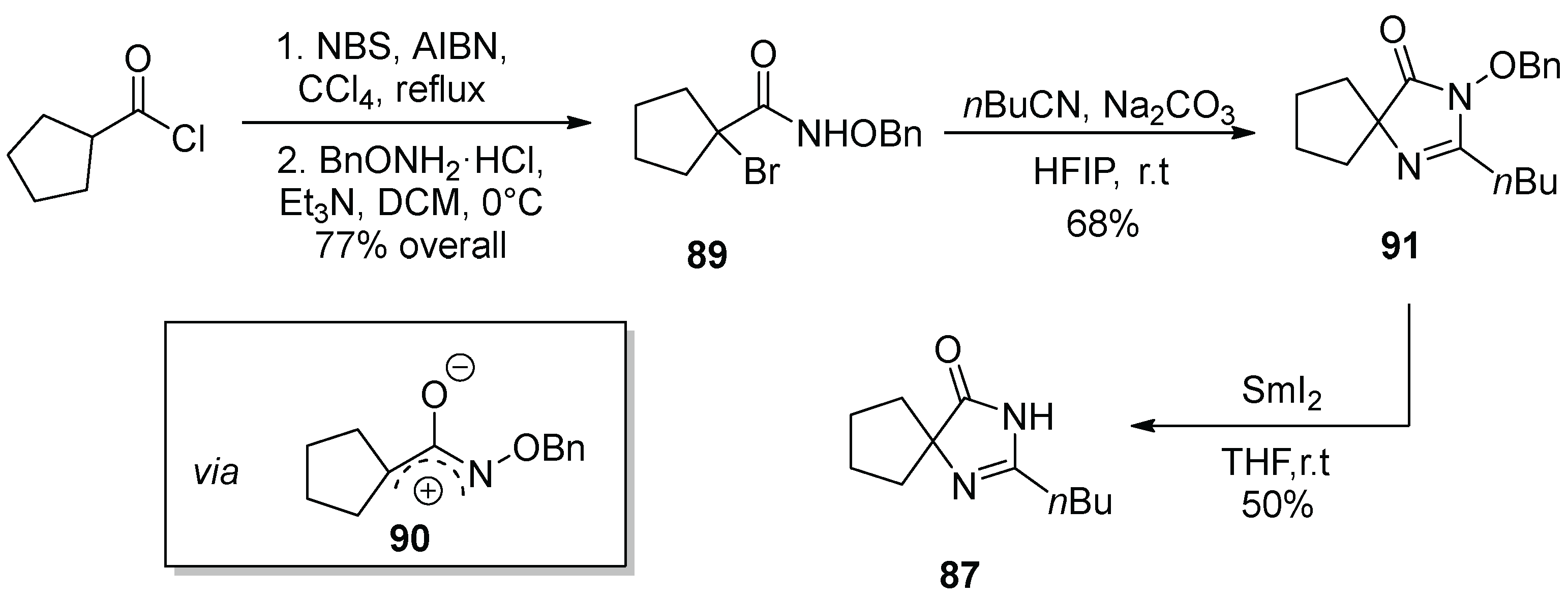

12. Irbesartan

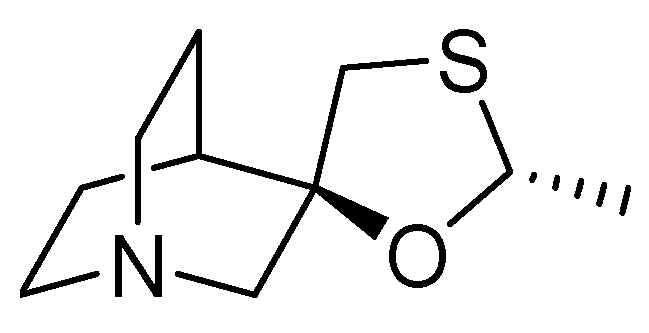

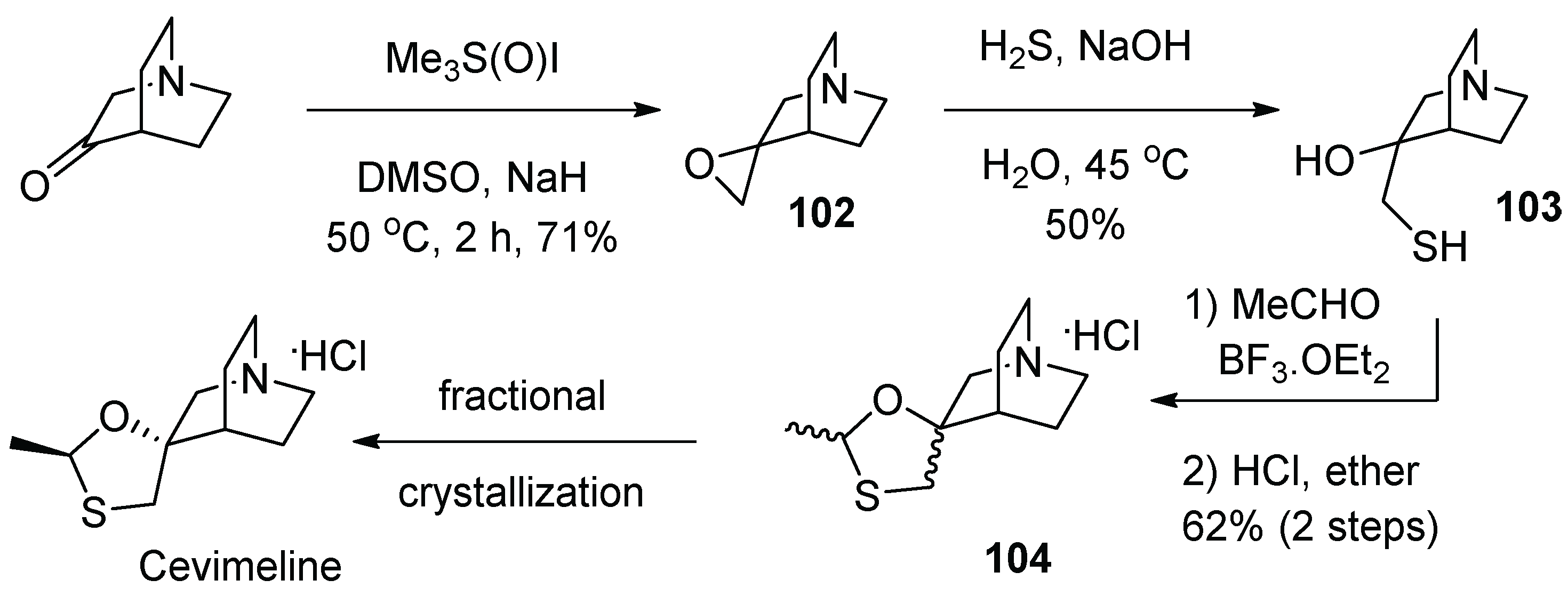

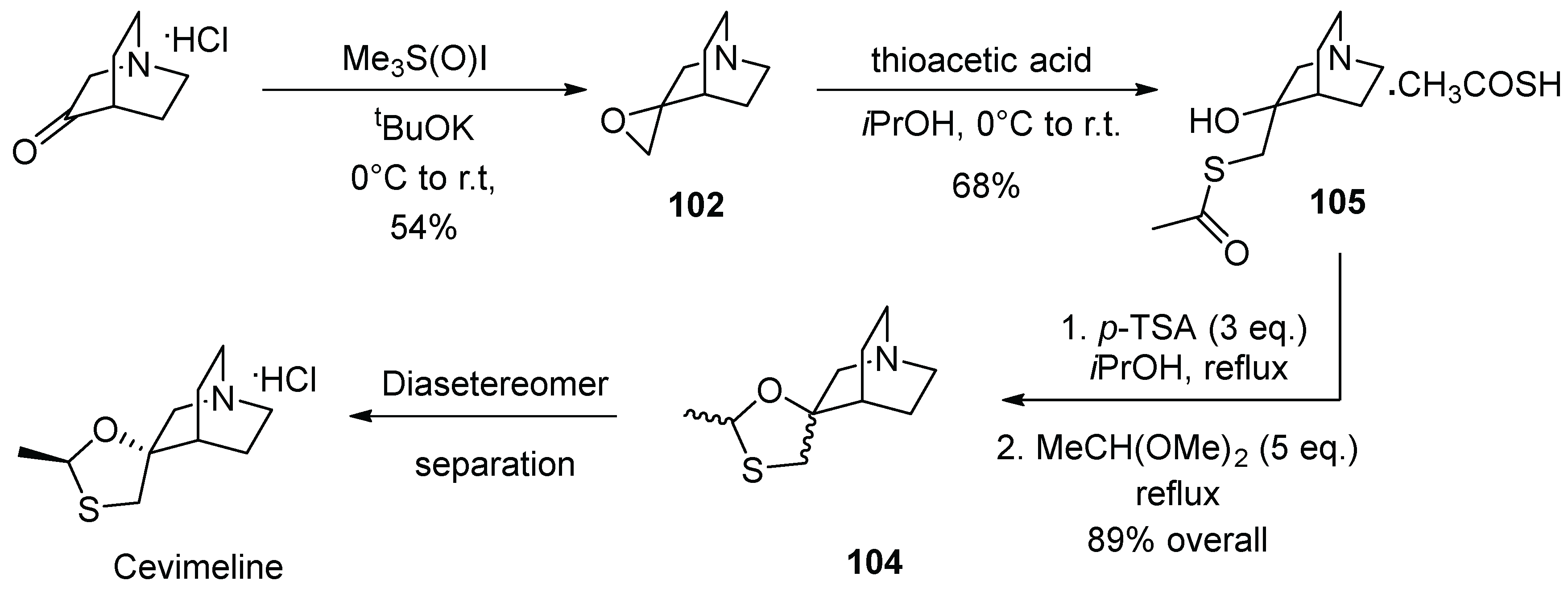

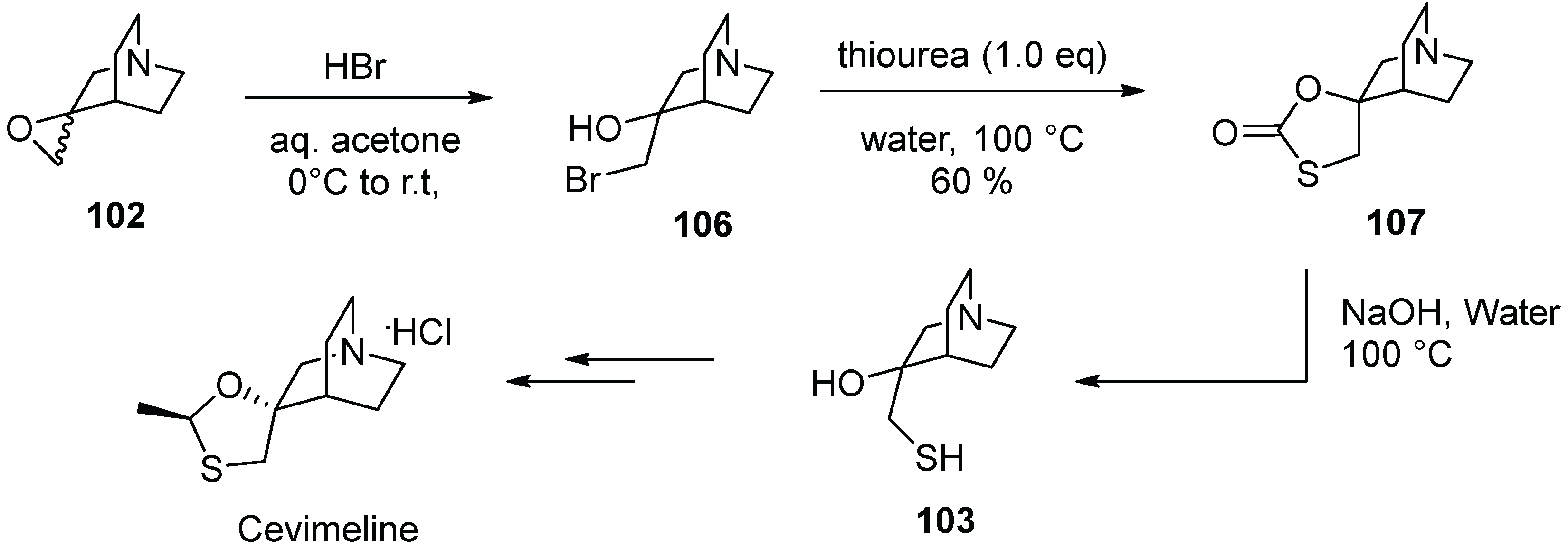

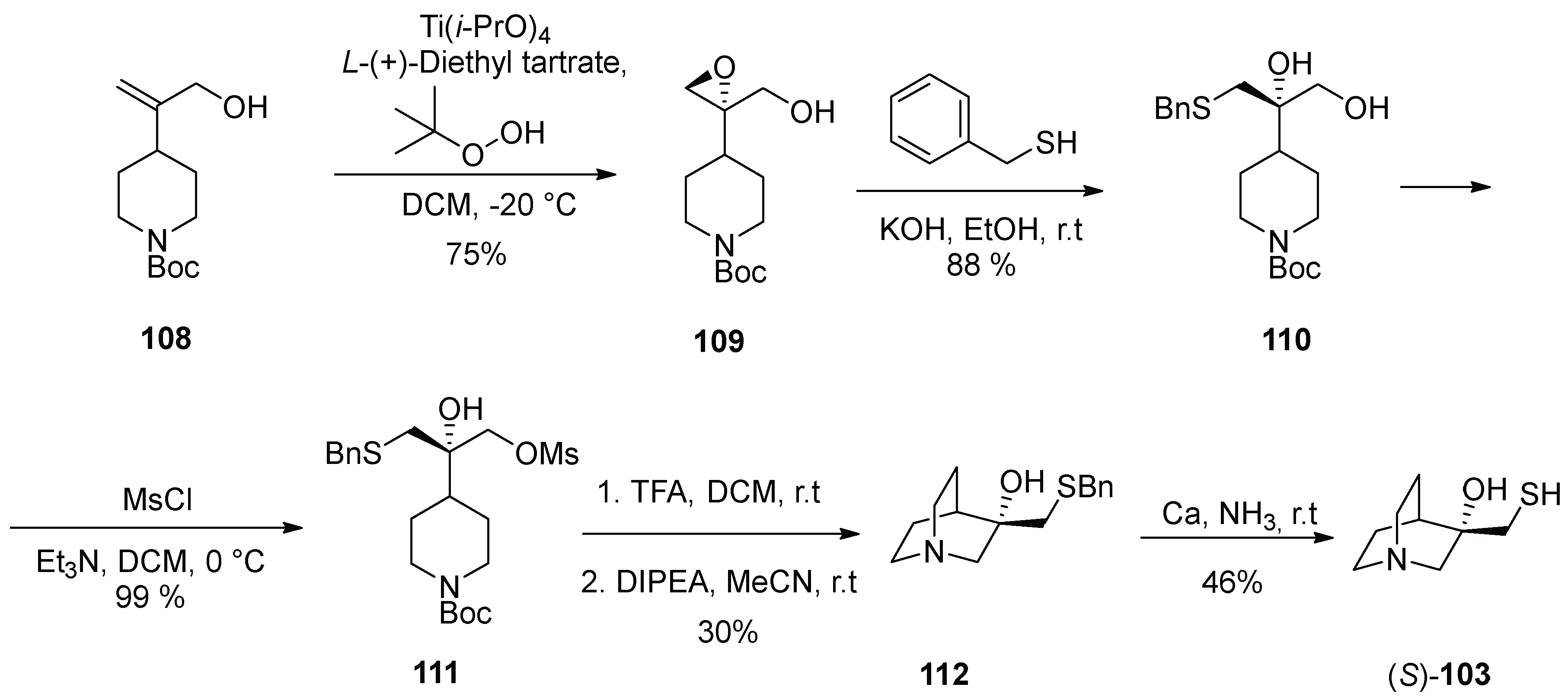

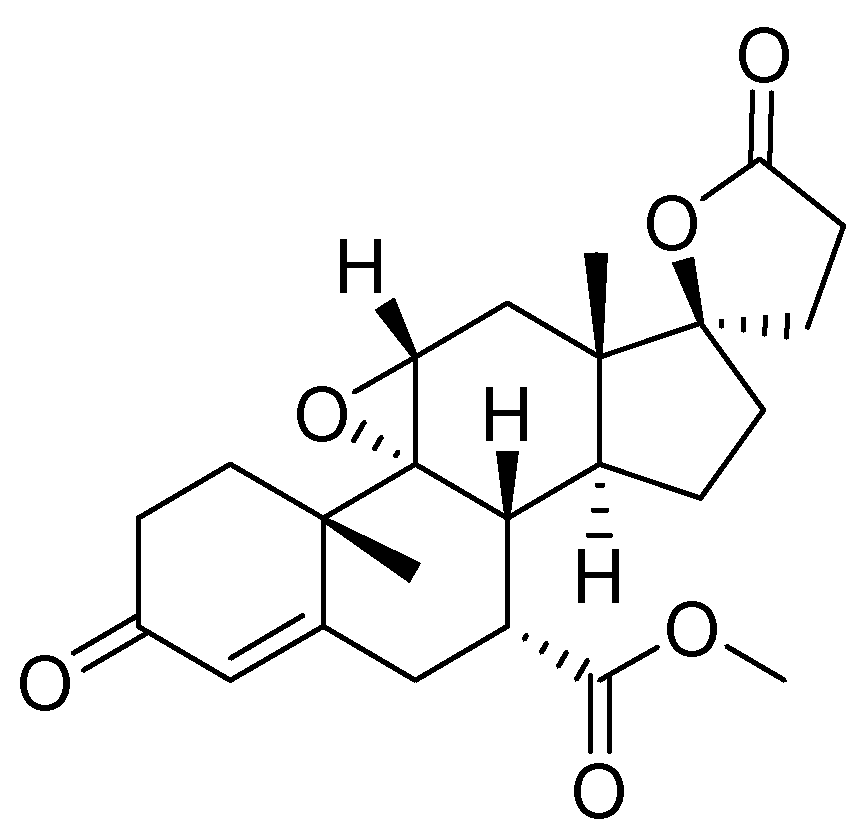

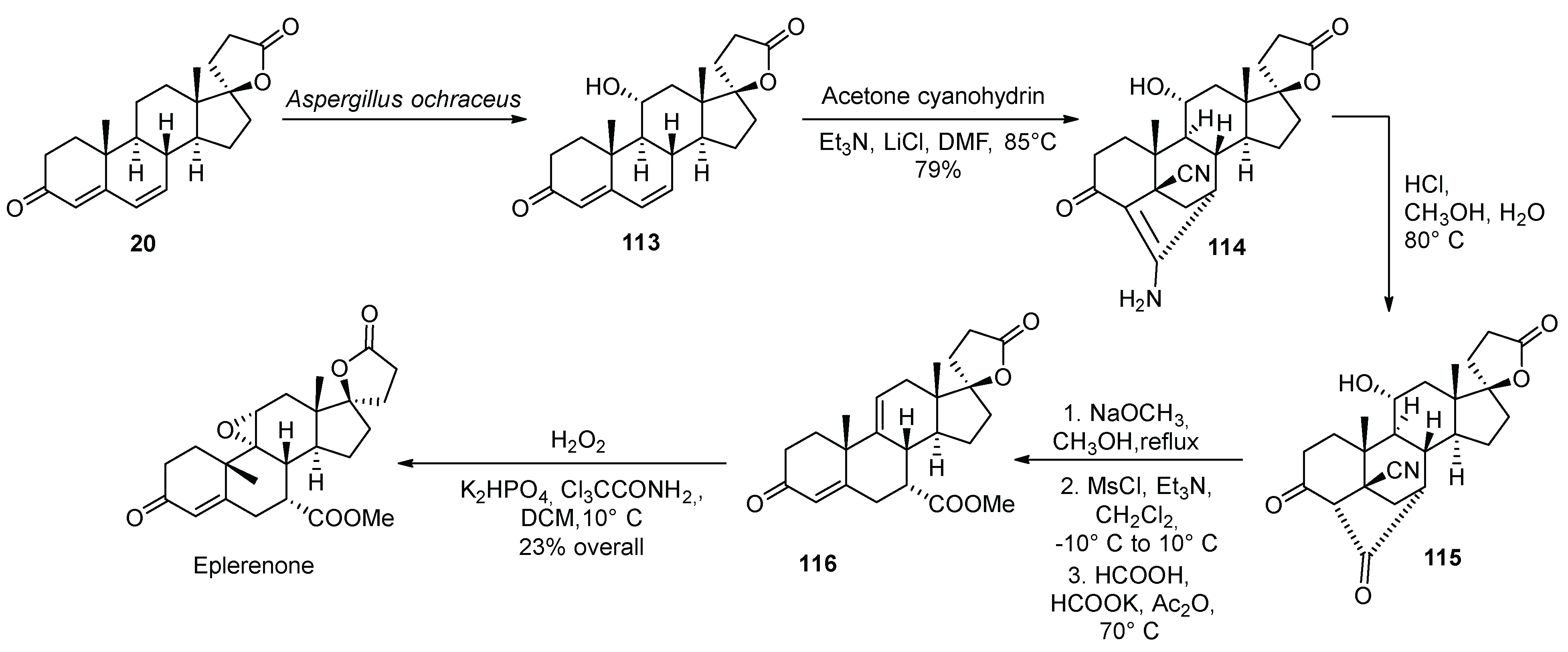

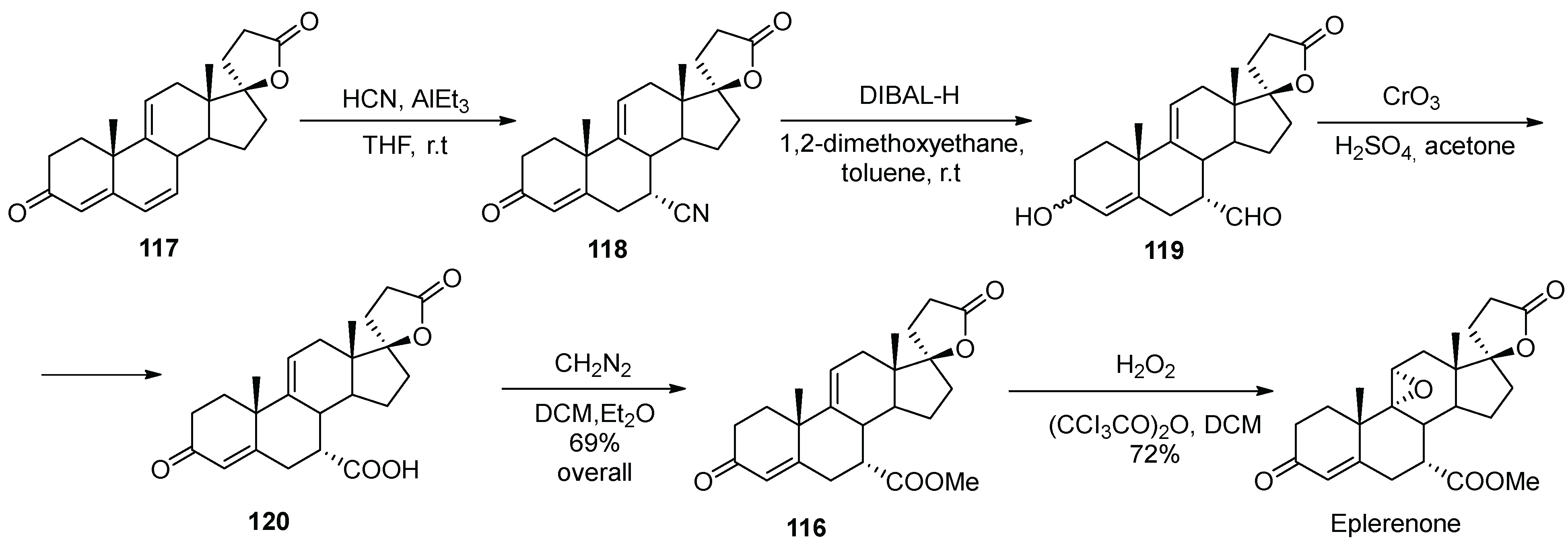

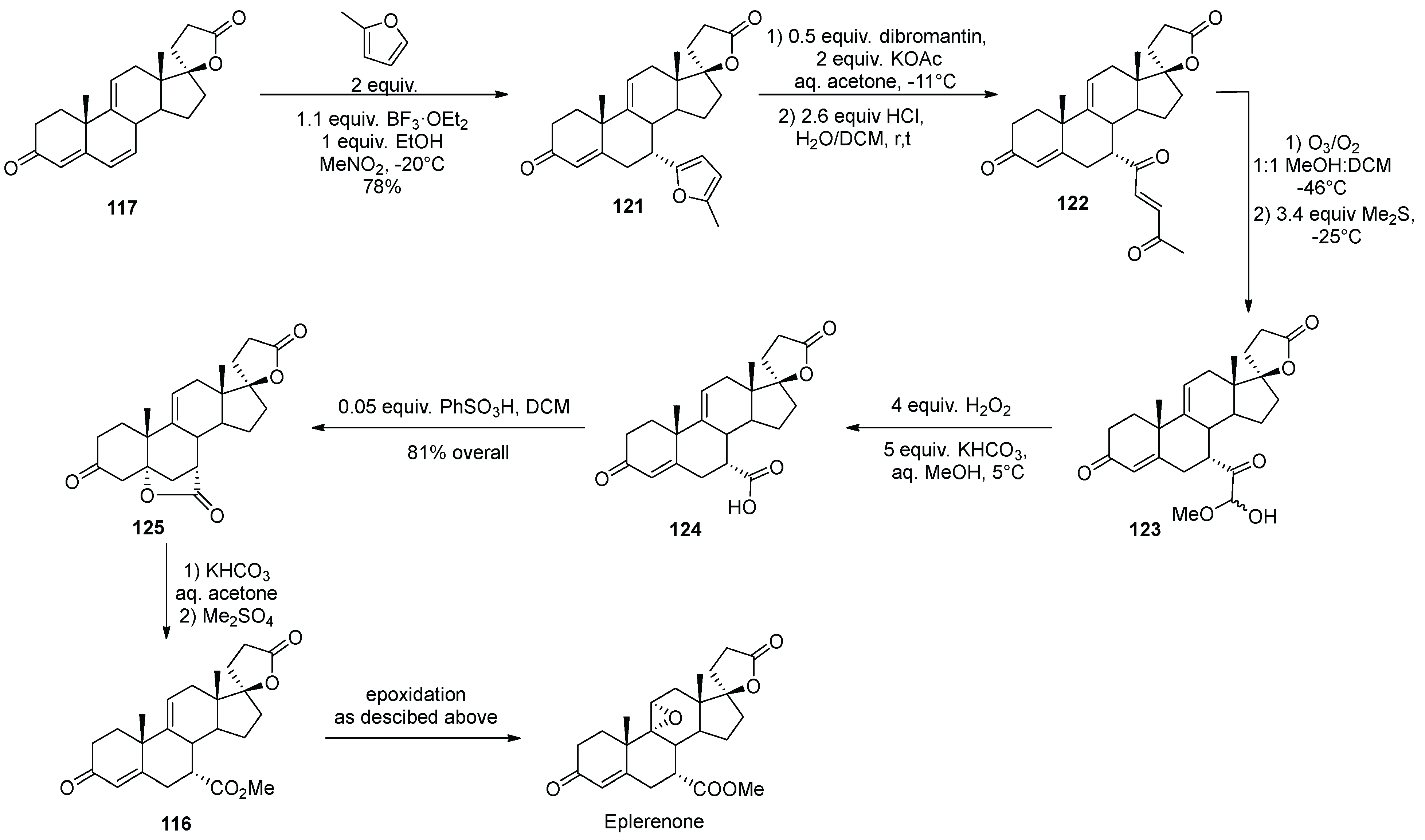

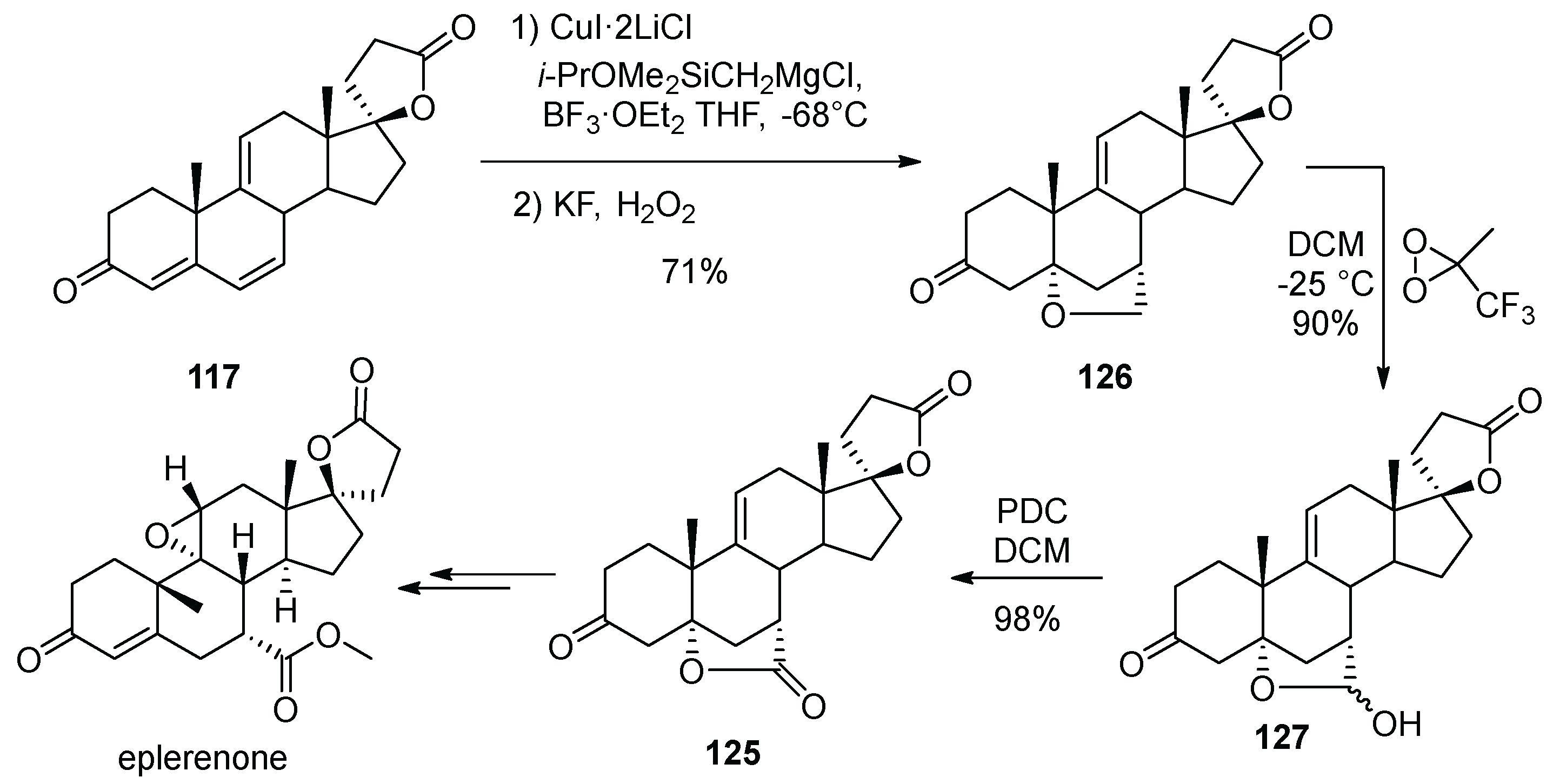

13. Cevimeline

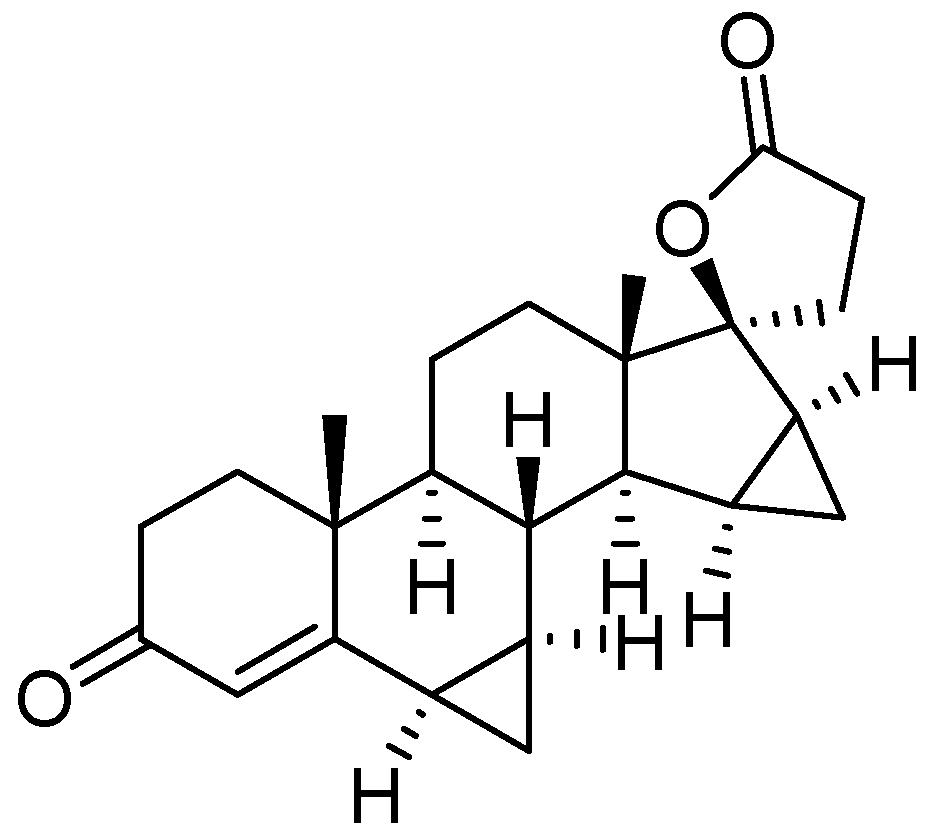

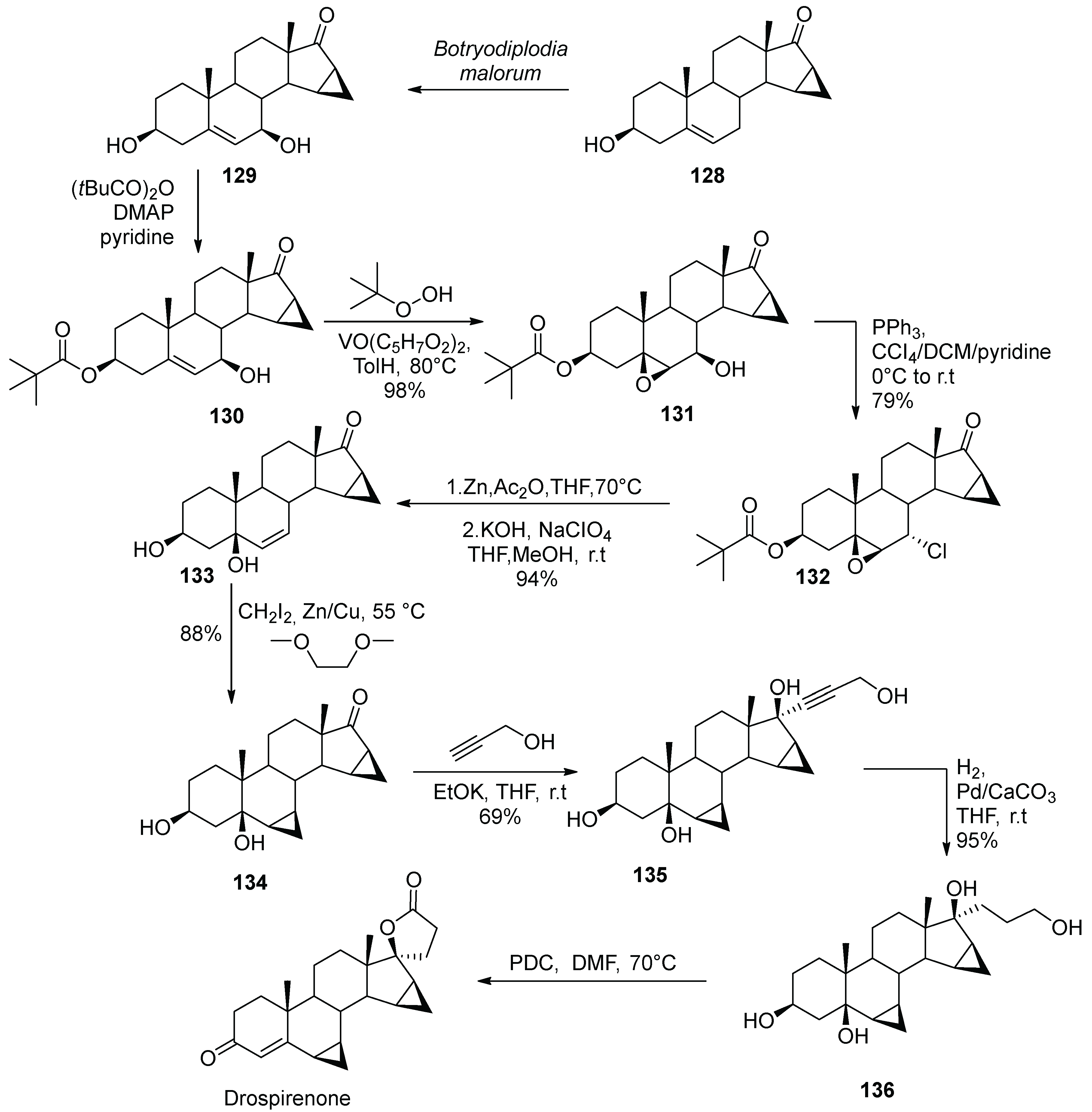

14. Eplerenone

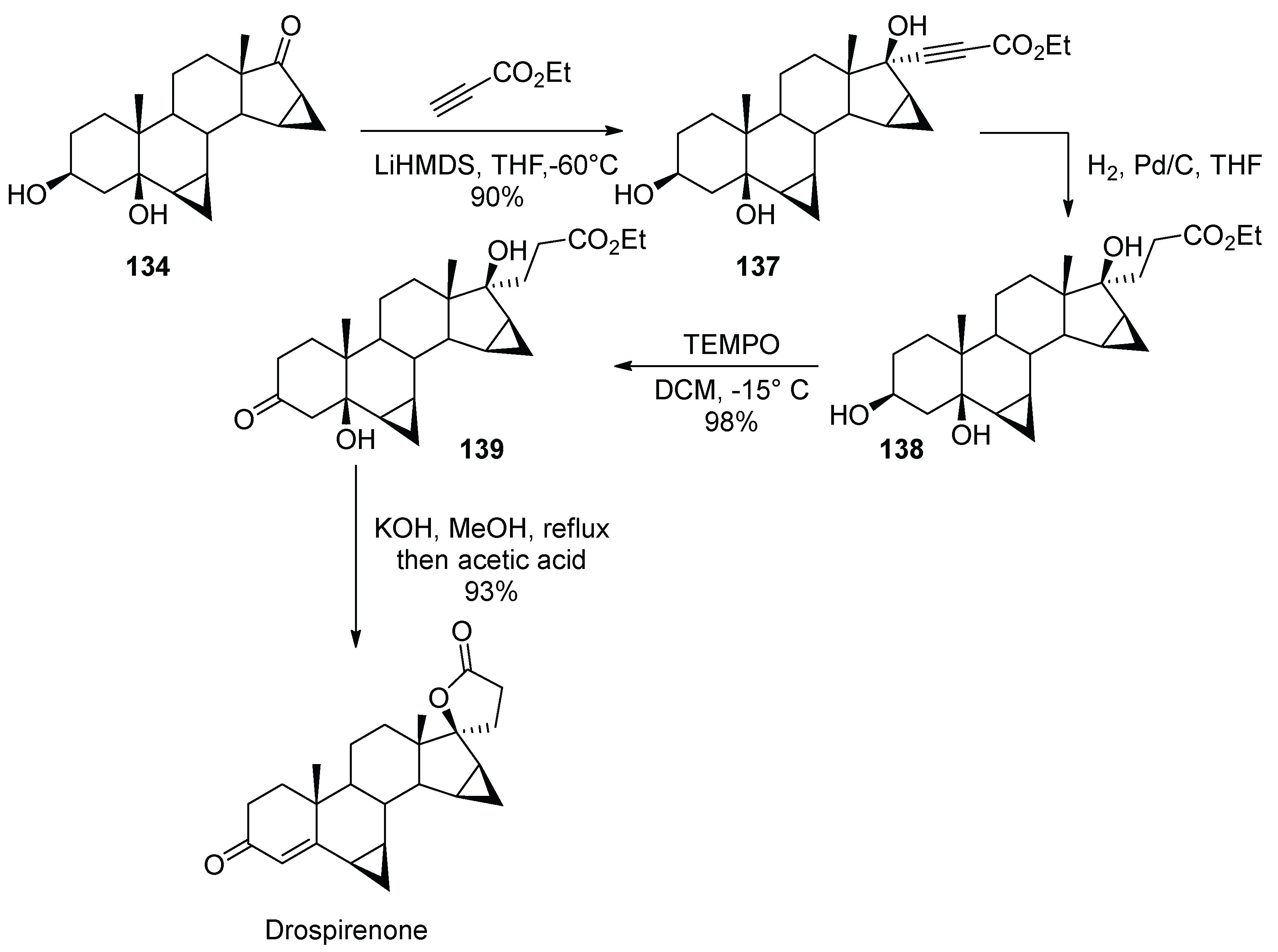

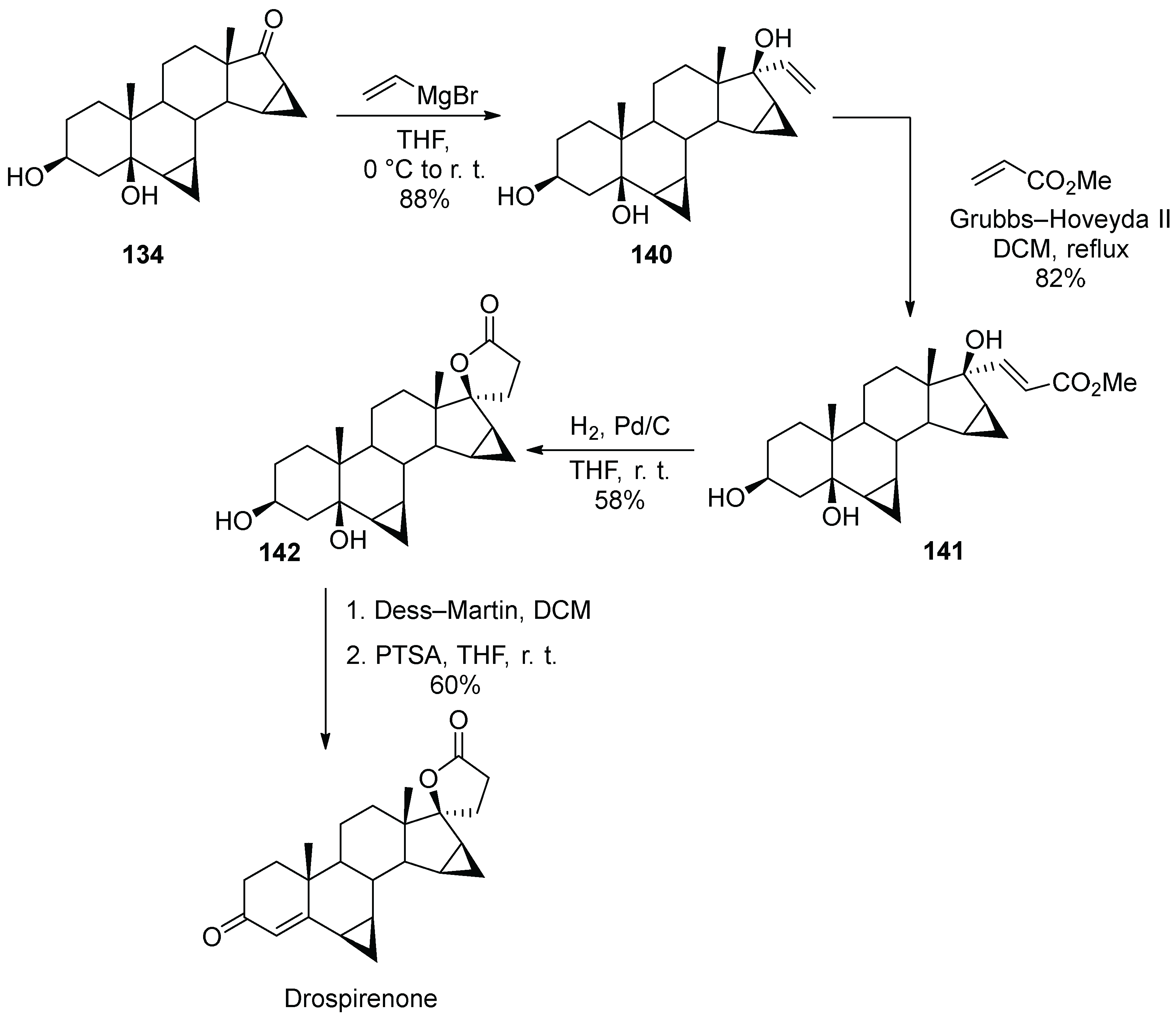

15. Drospirenone

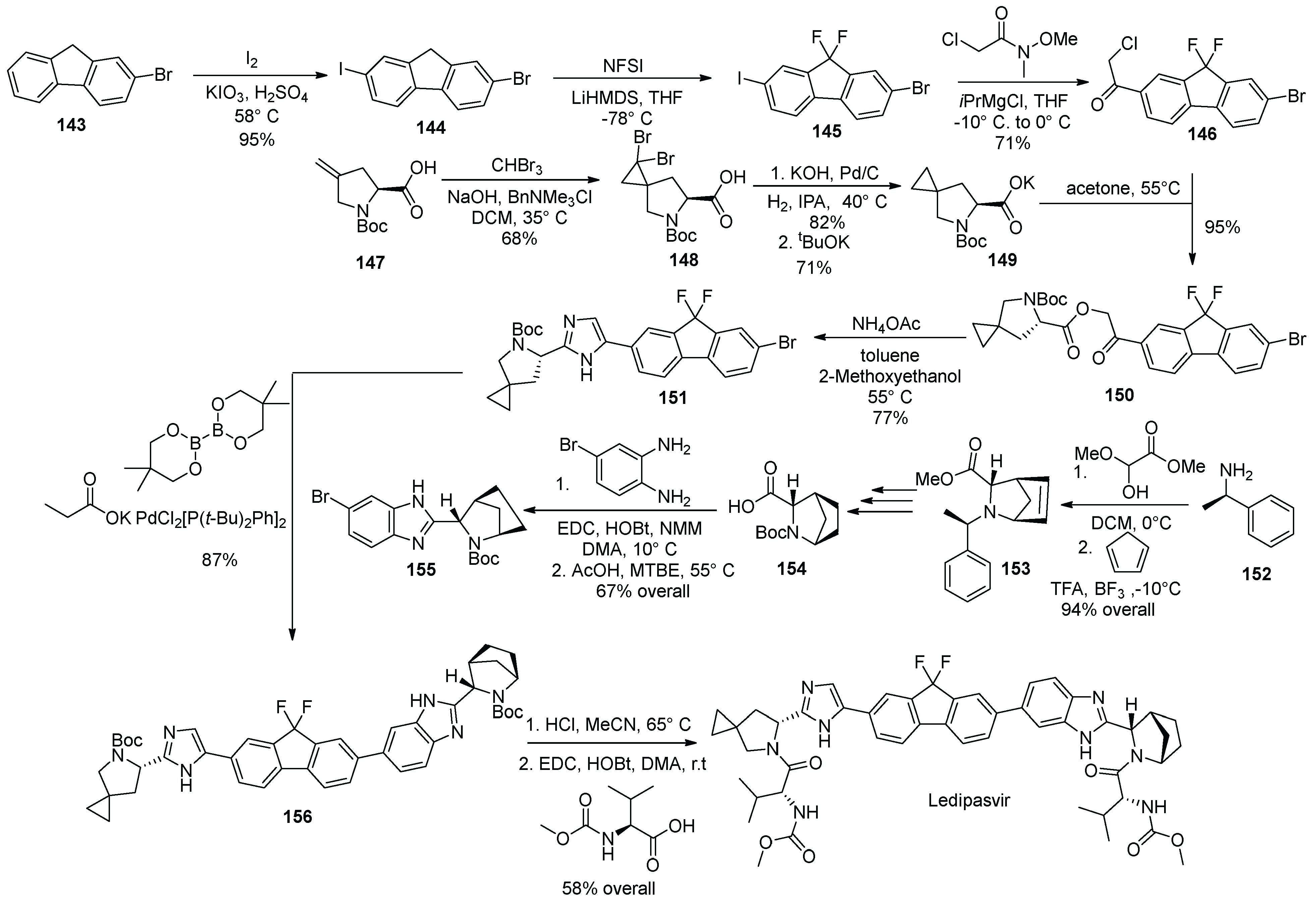

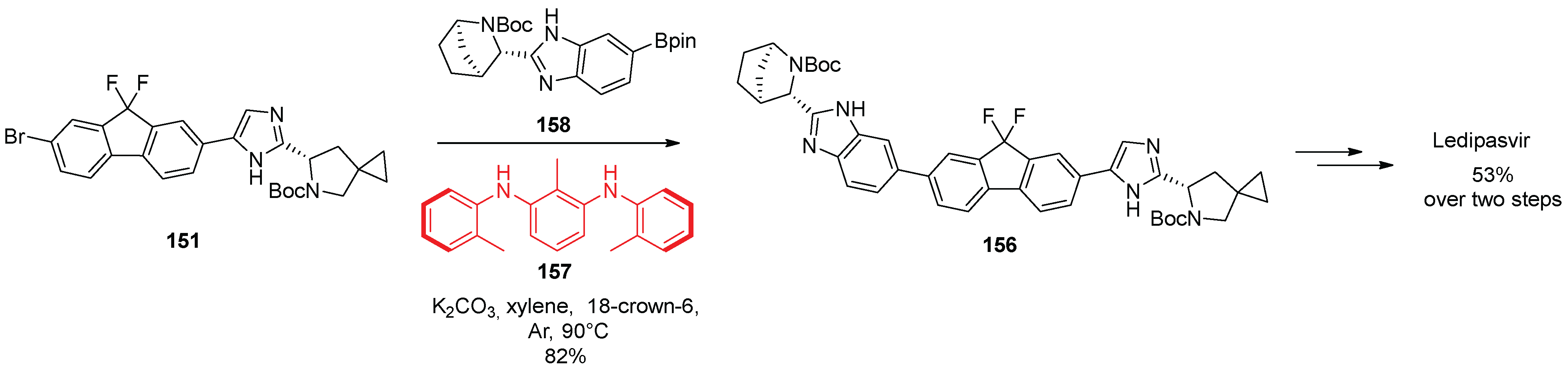

16. Ledipasvir

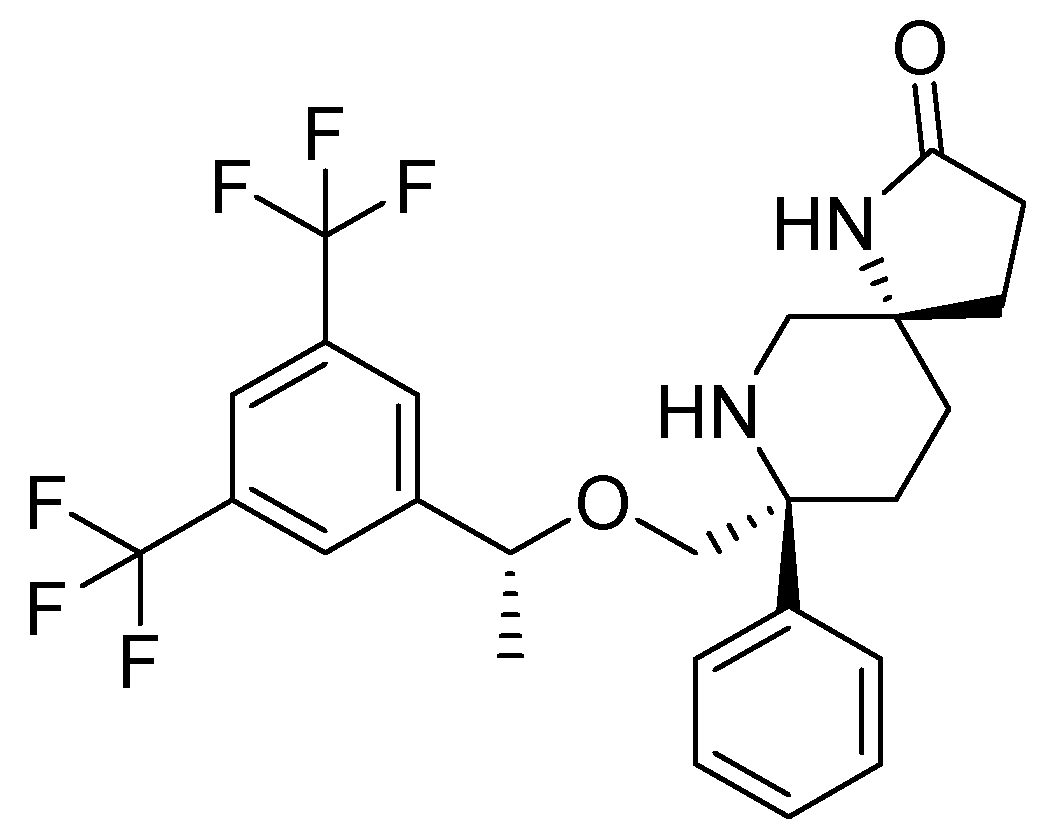

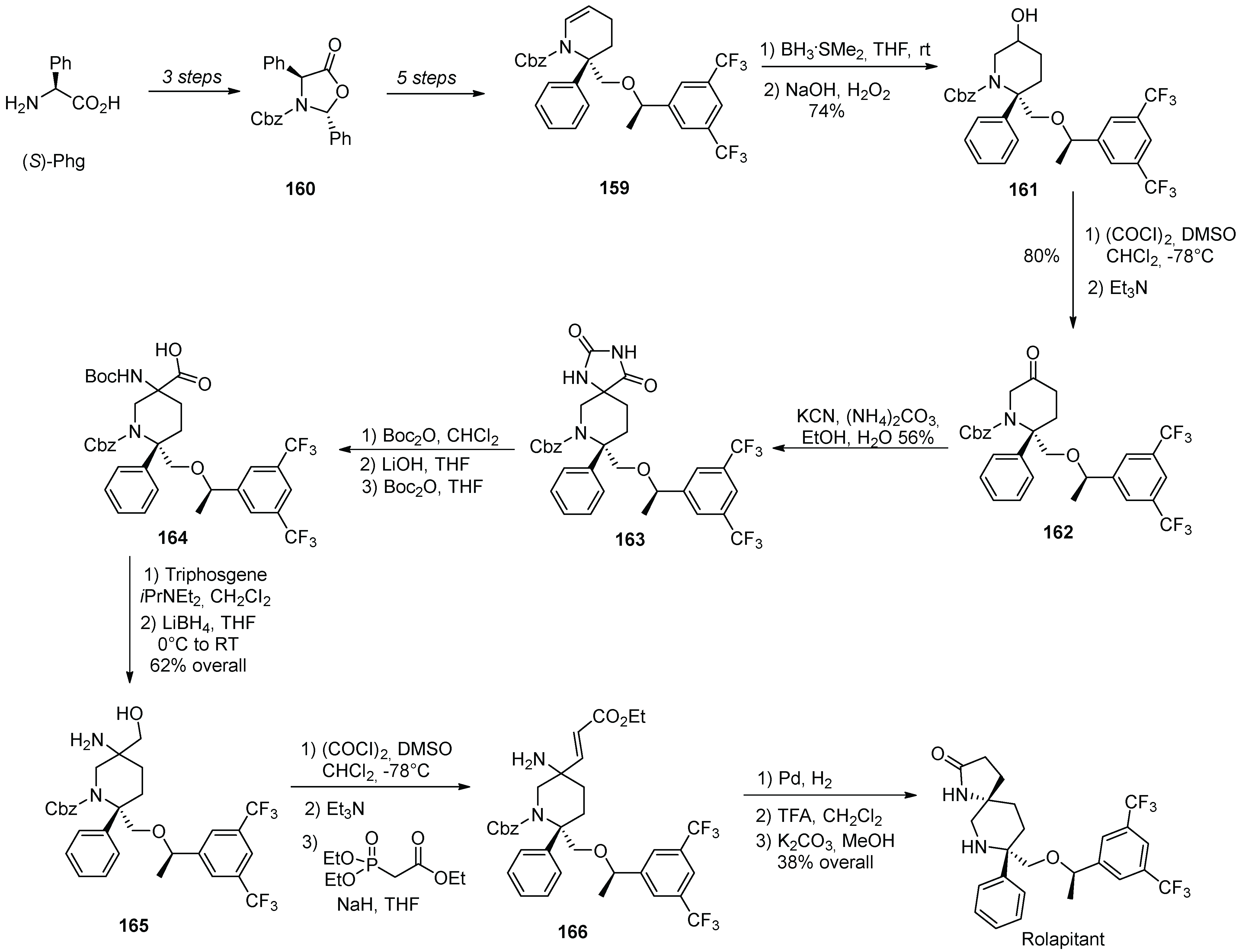

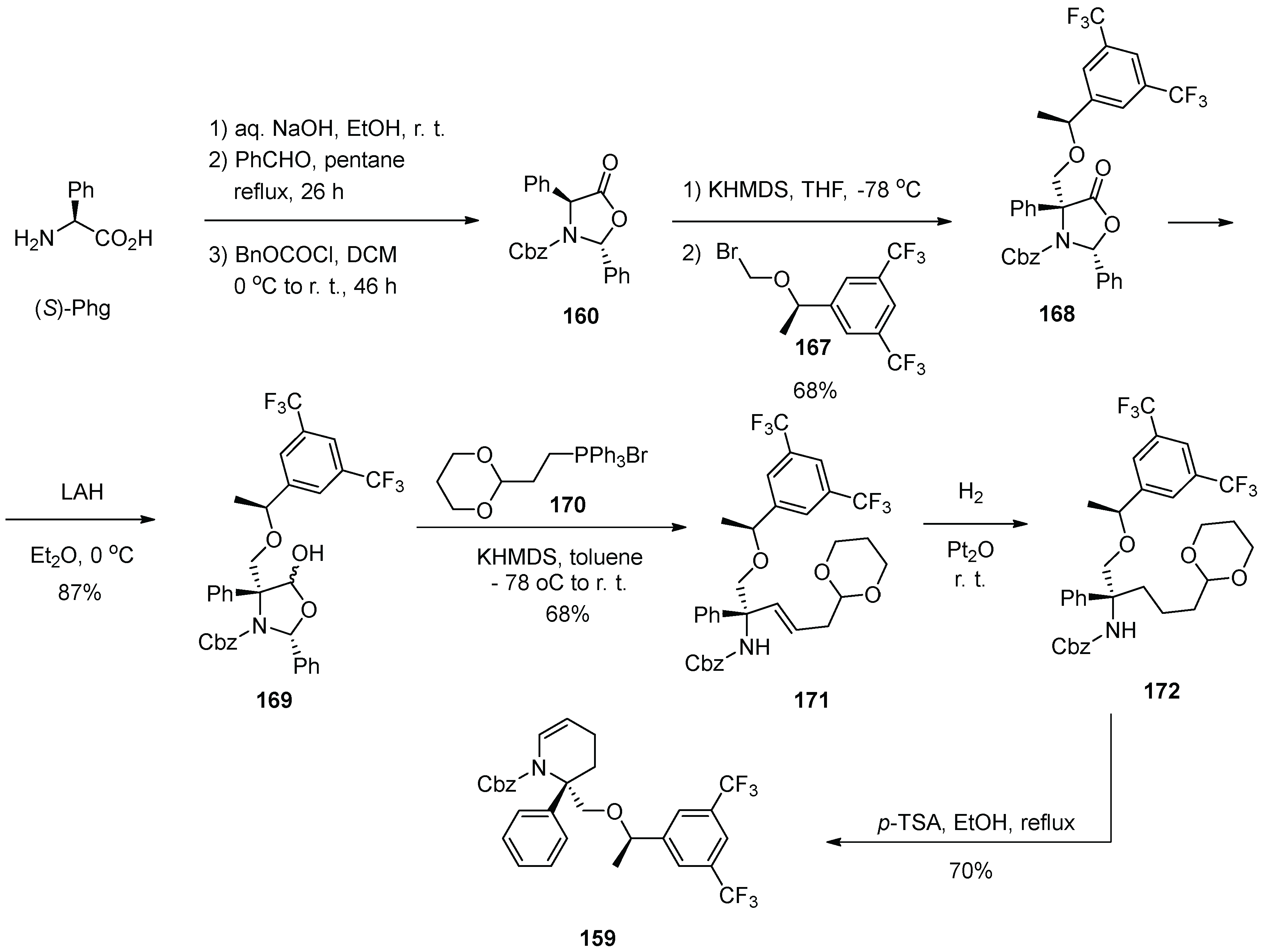

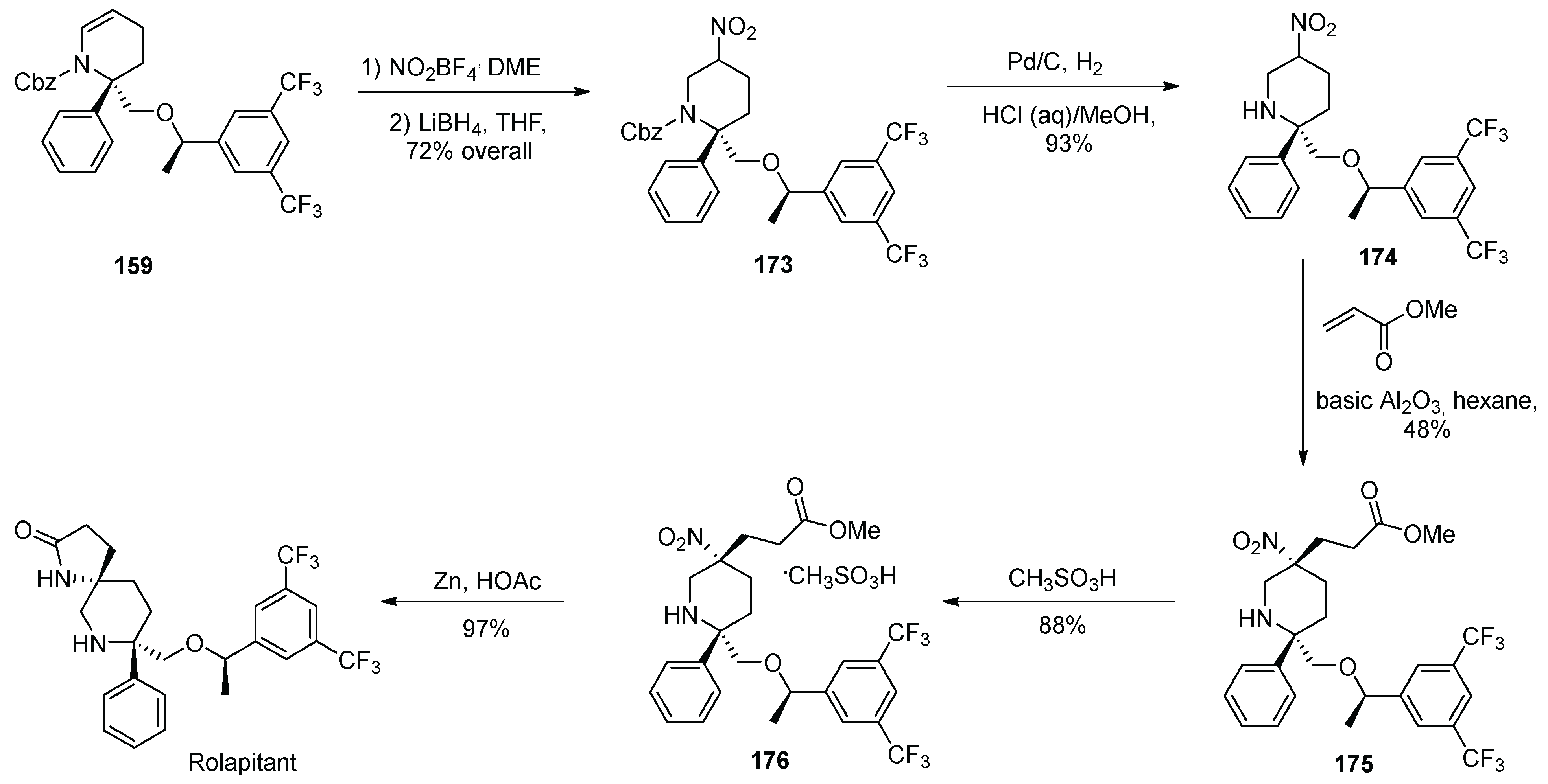

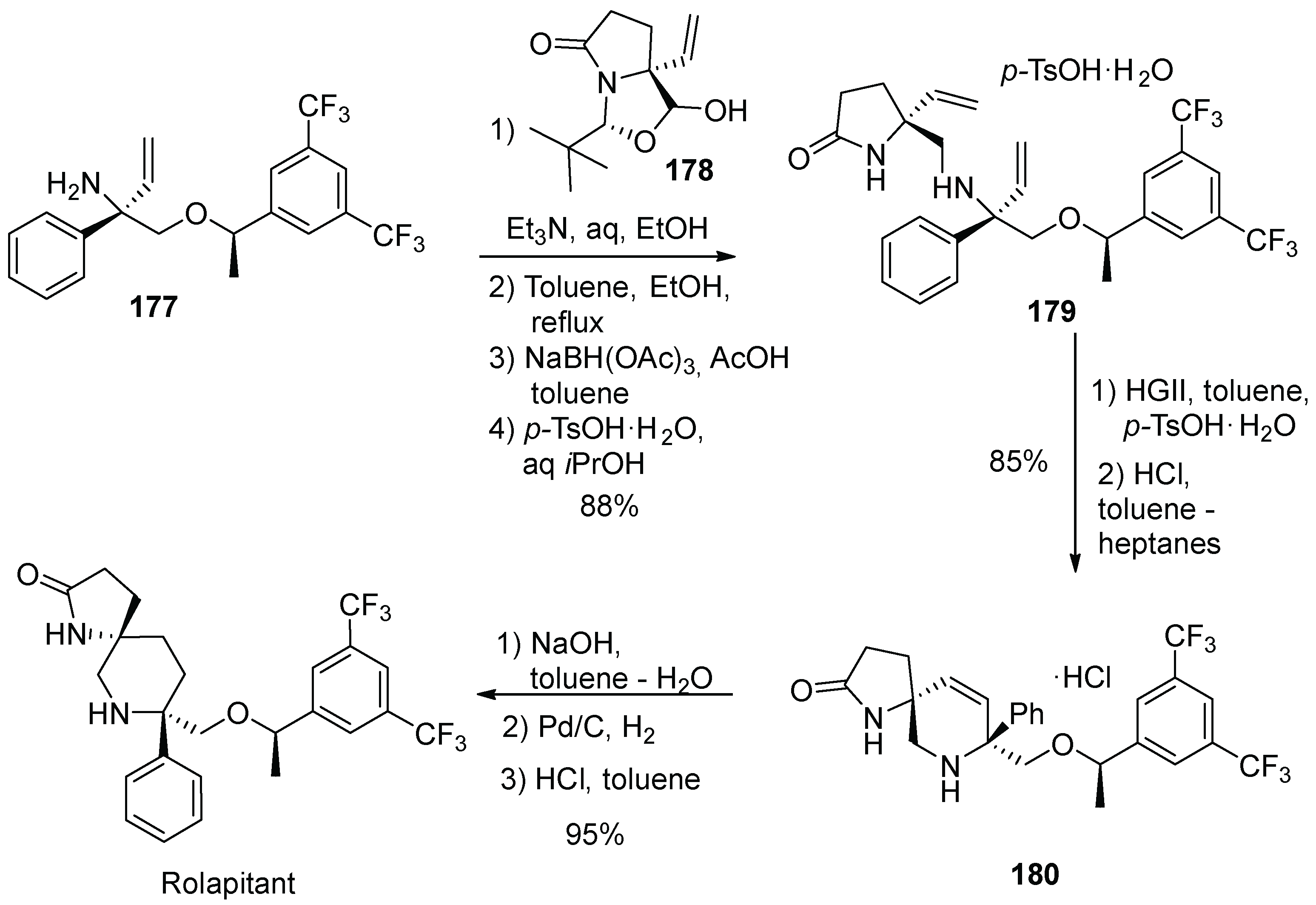

17. Rolapitant

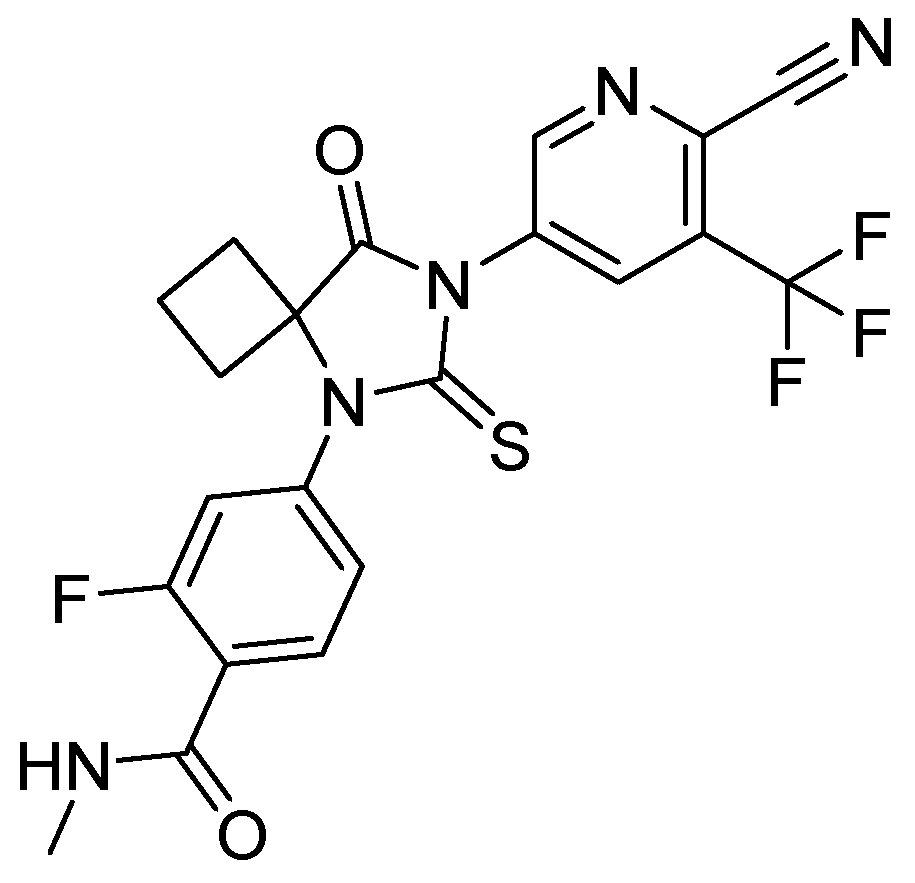

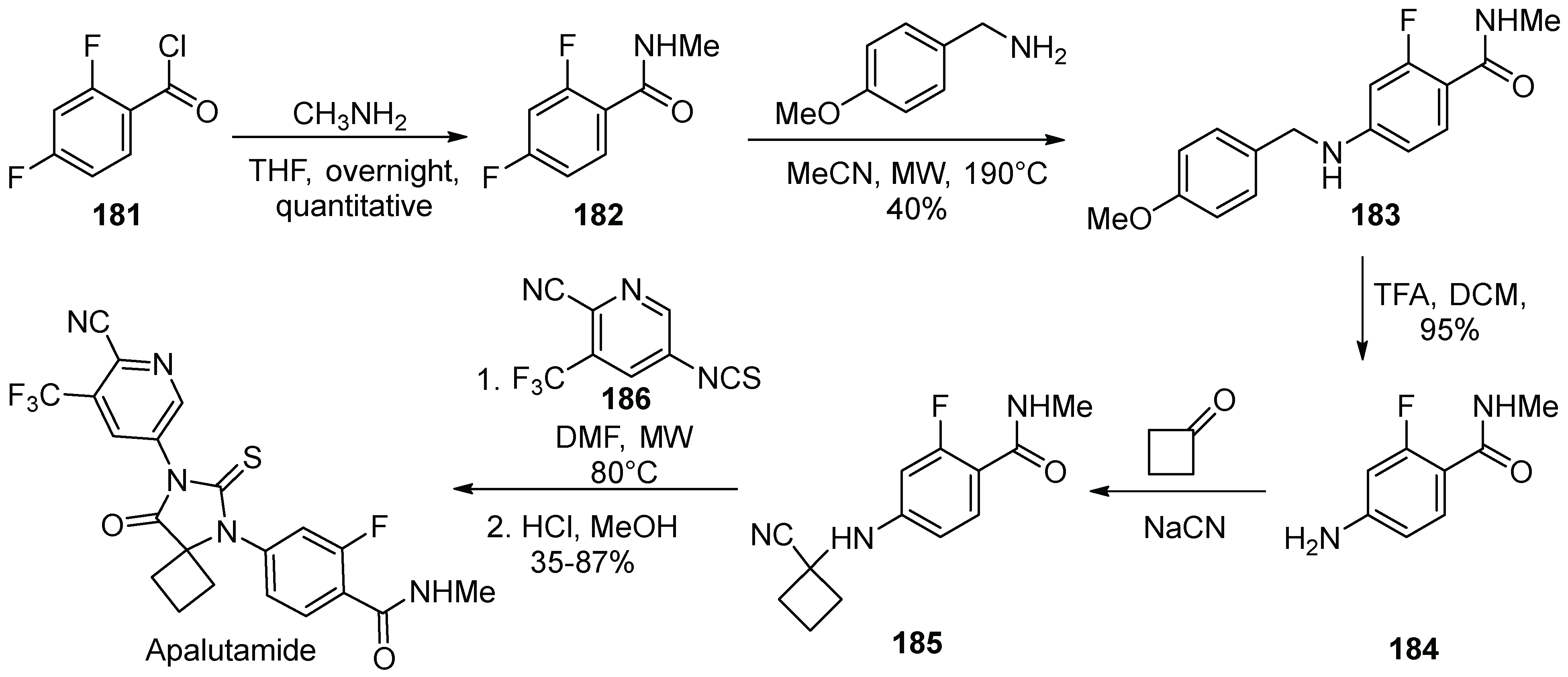

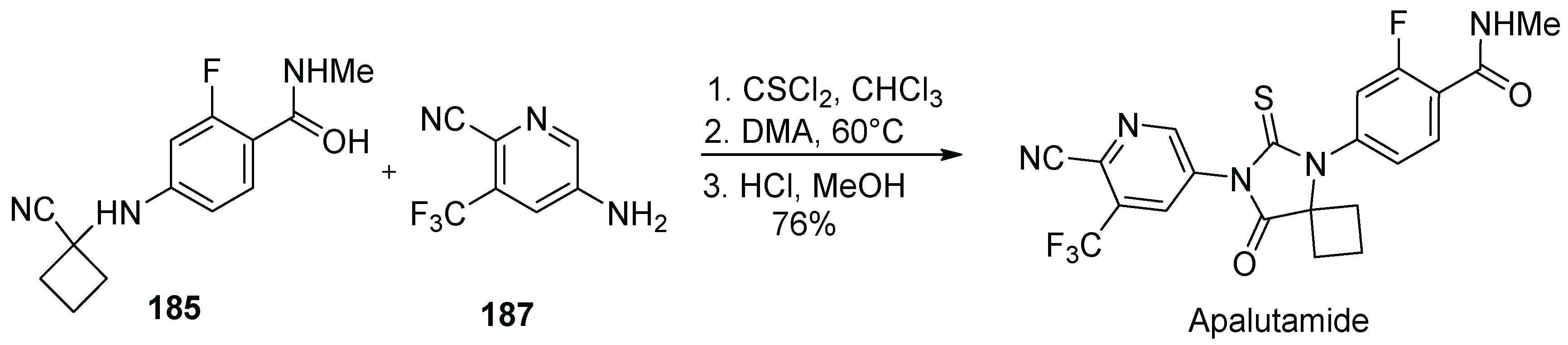

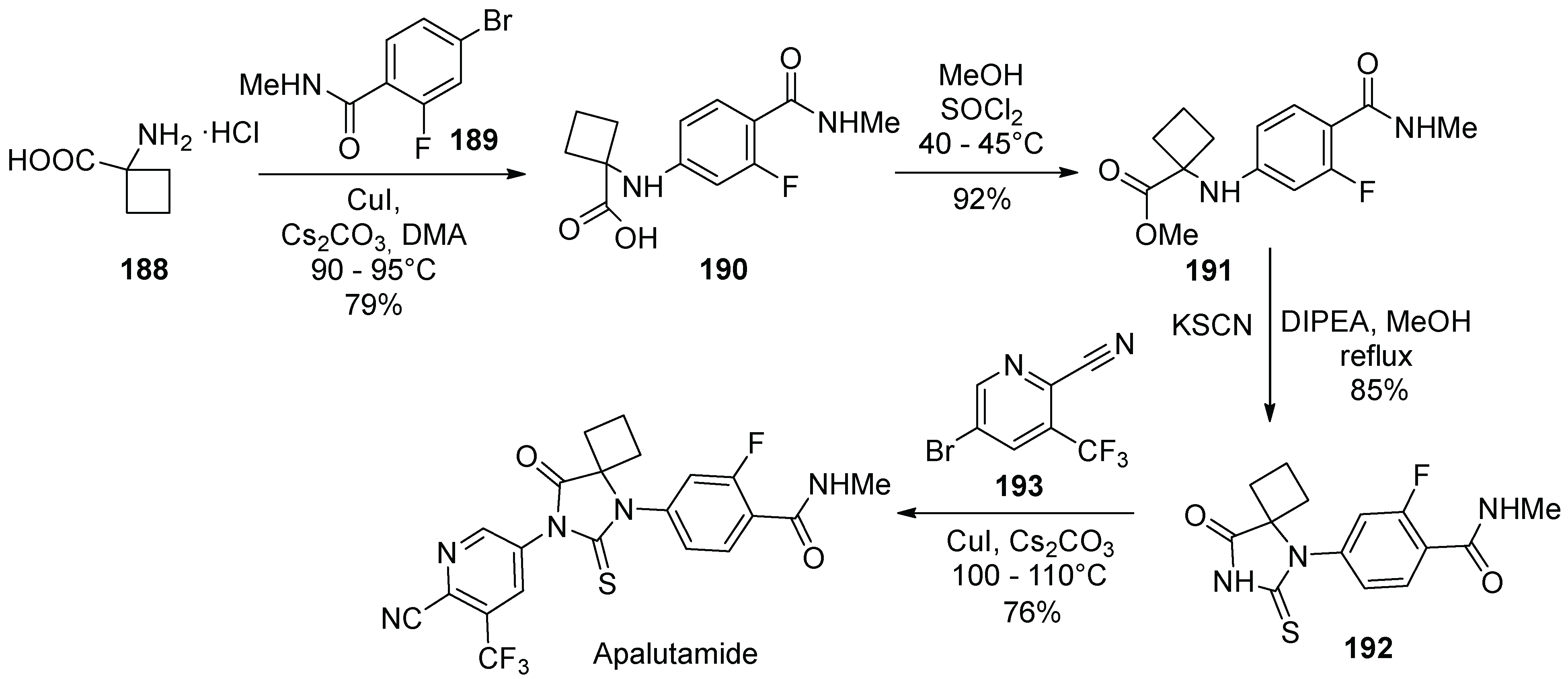

18. Apalutamide

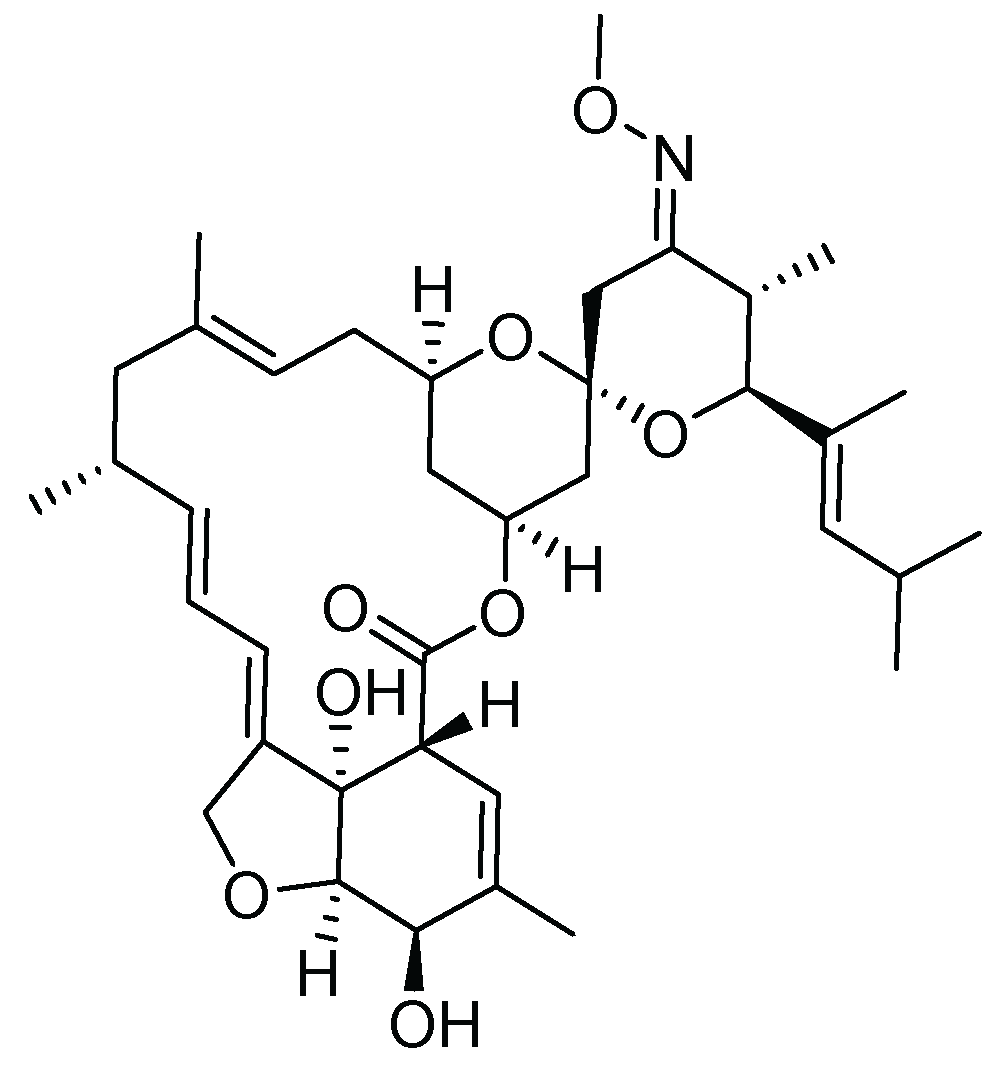

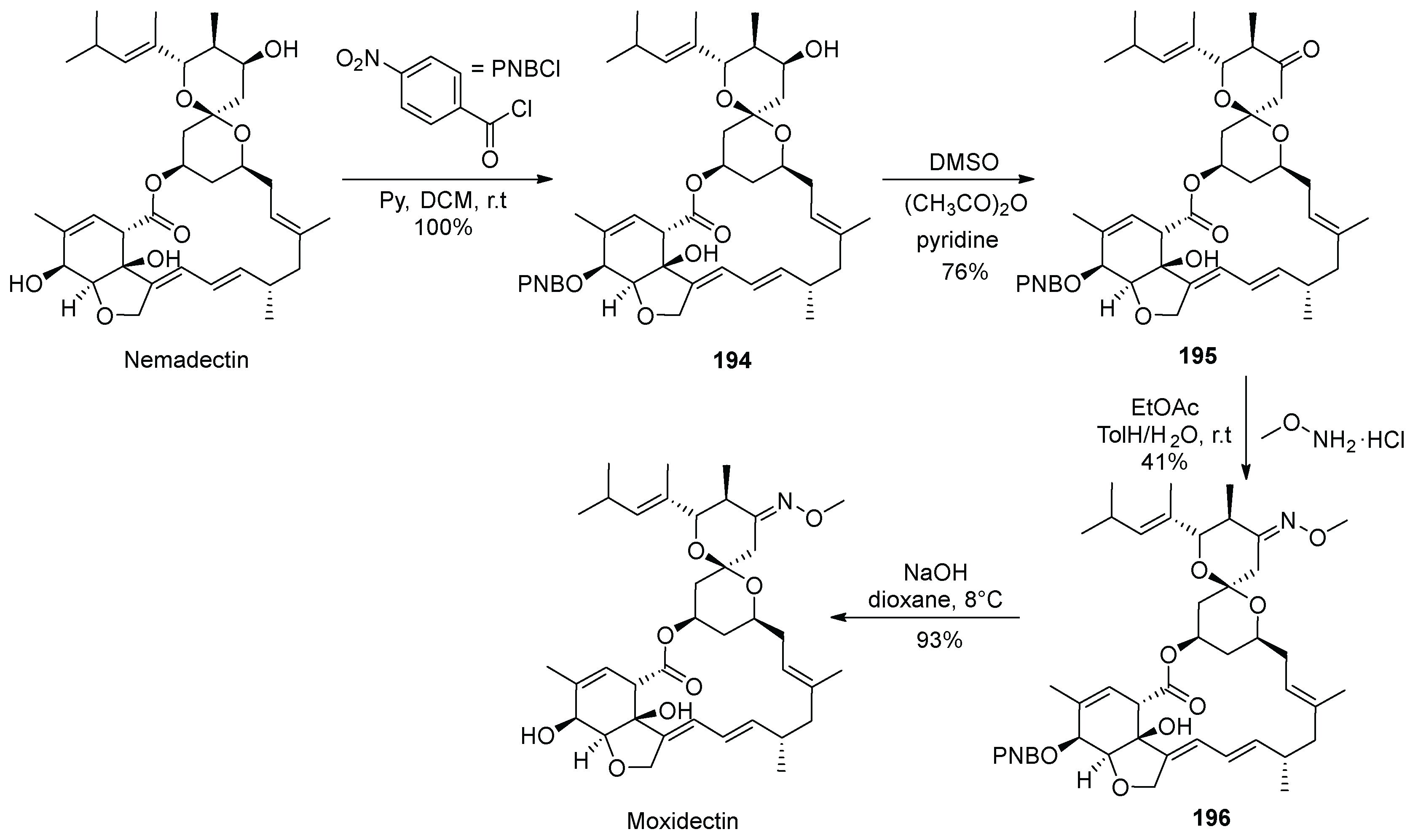

19. Moxidectin

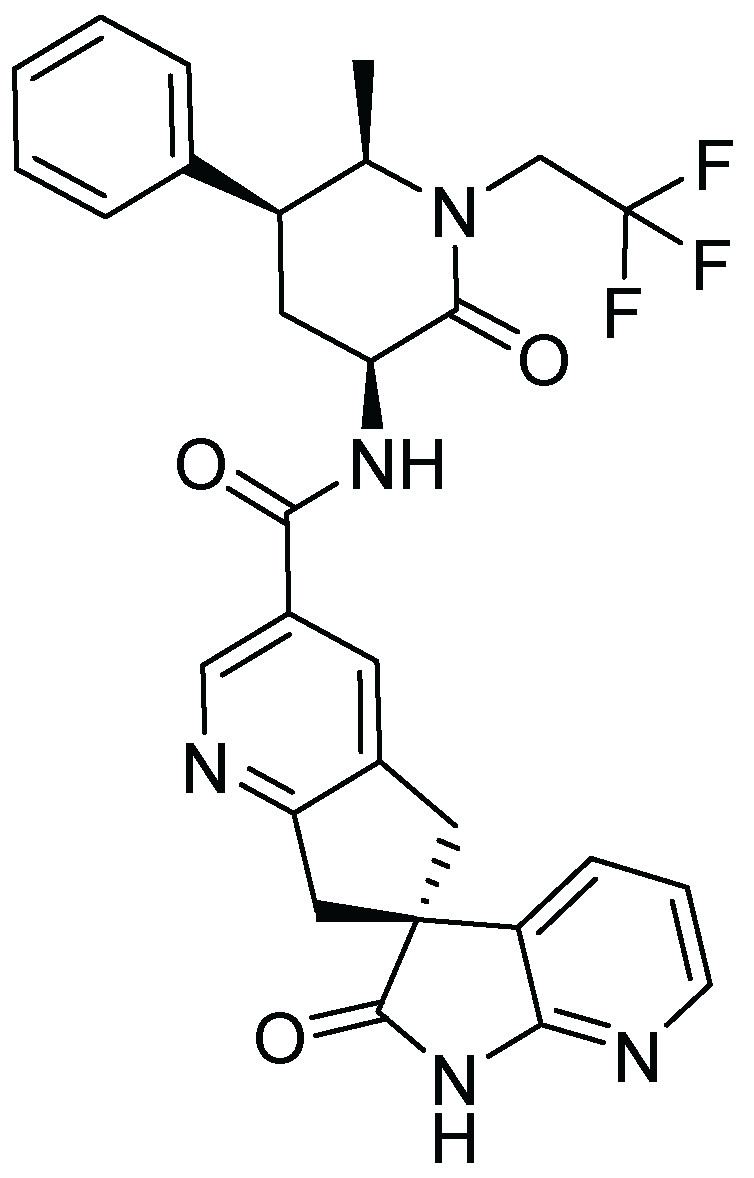

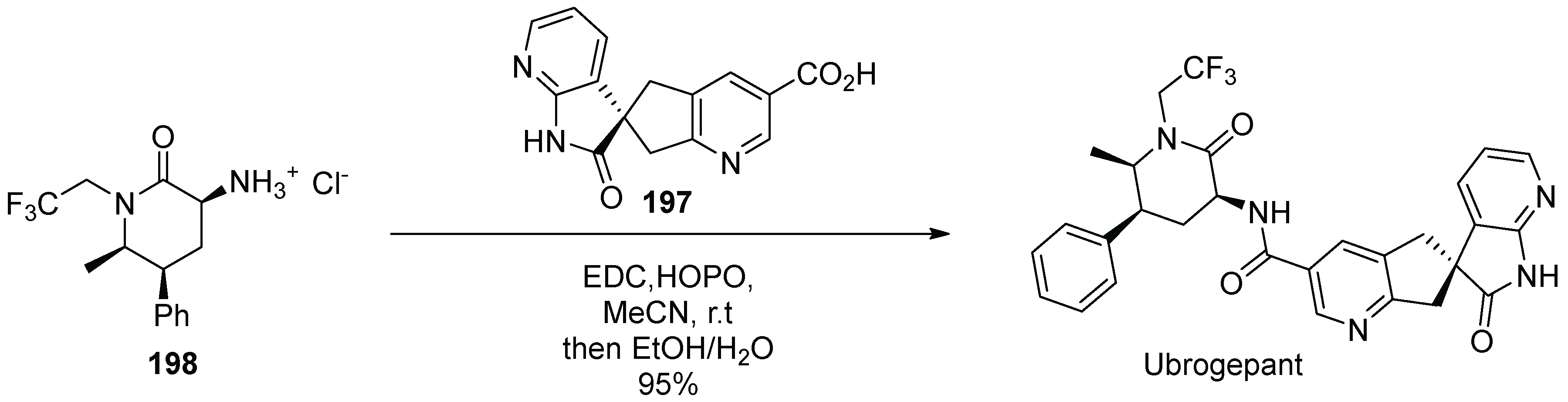

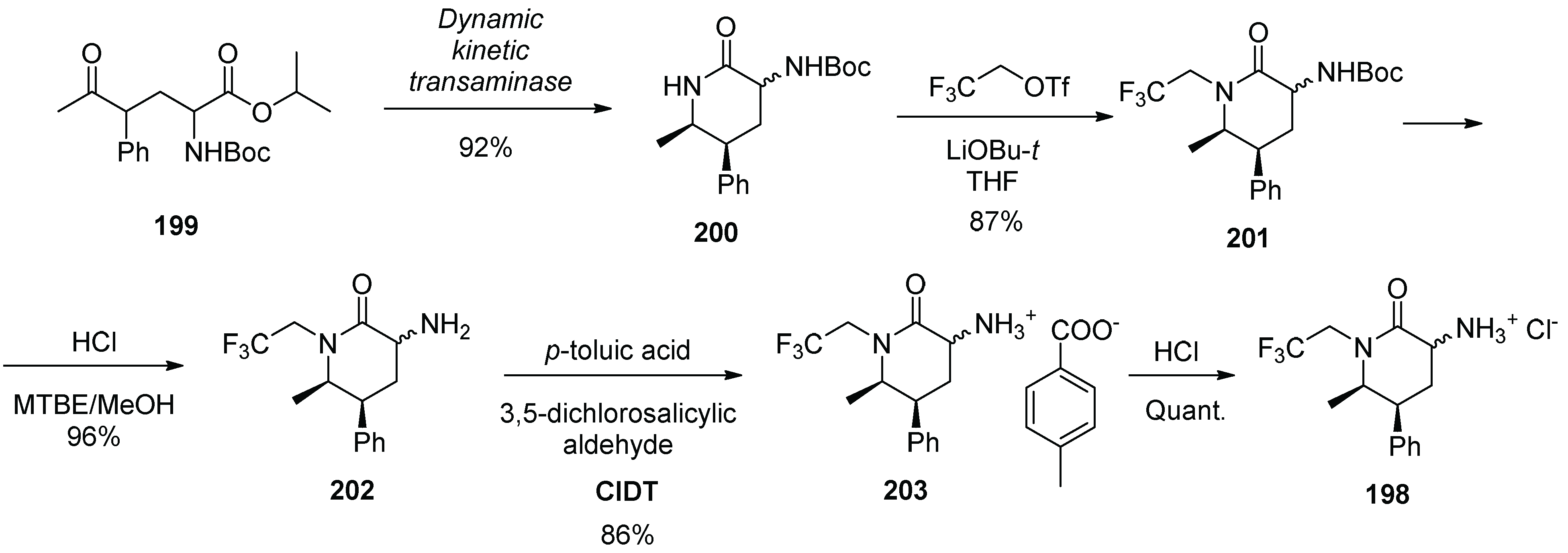

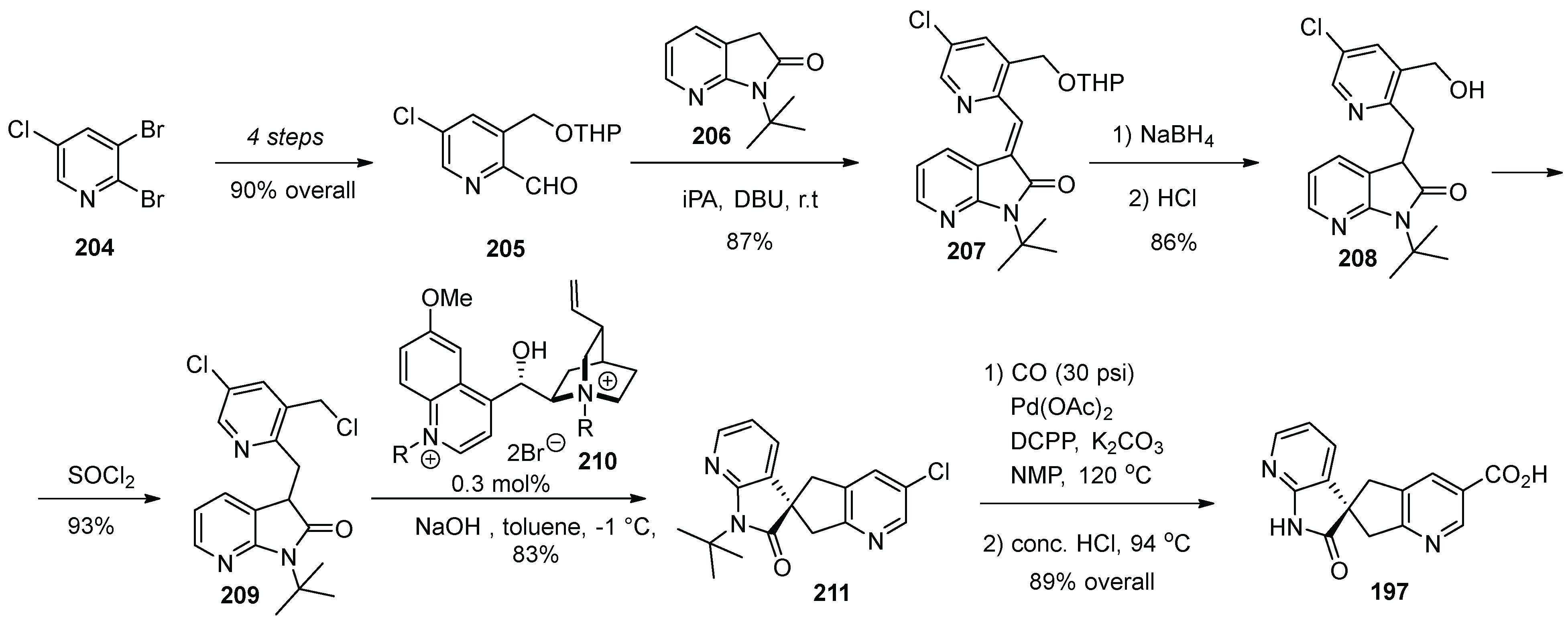

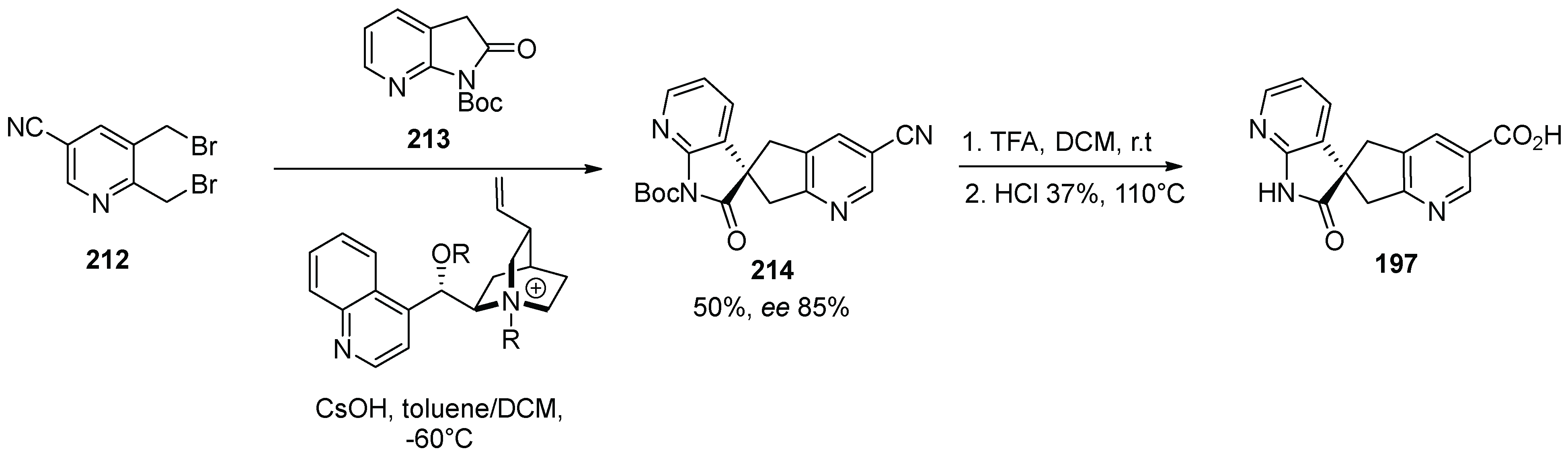

20. Ubrogepant

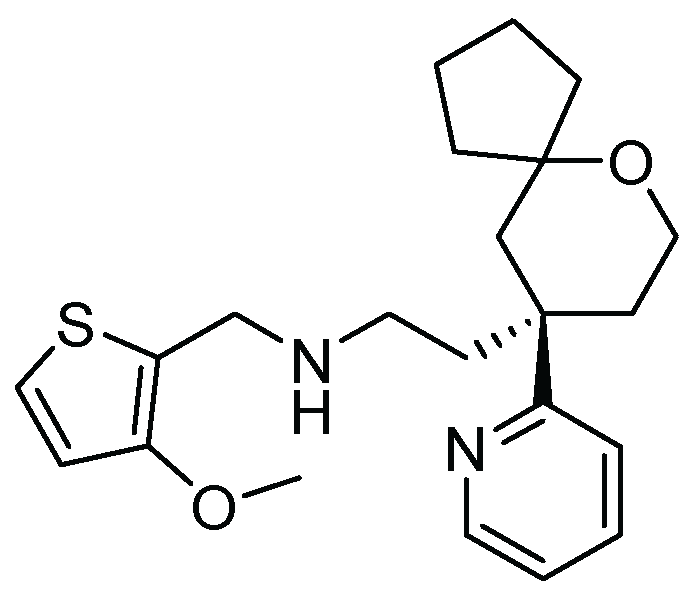

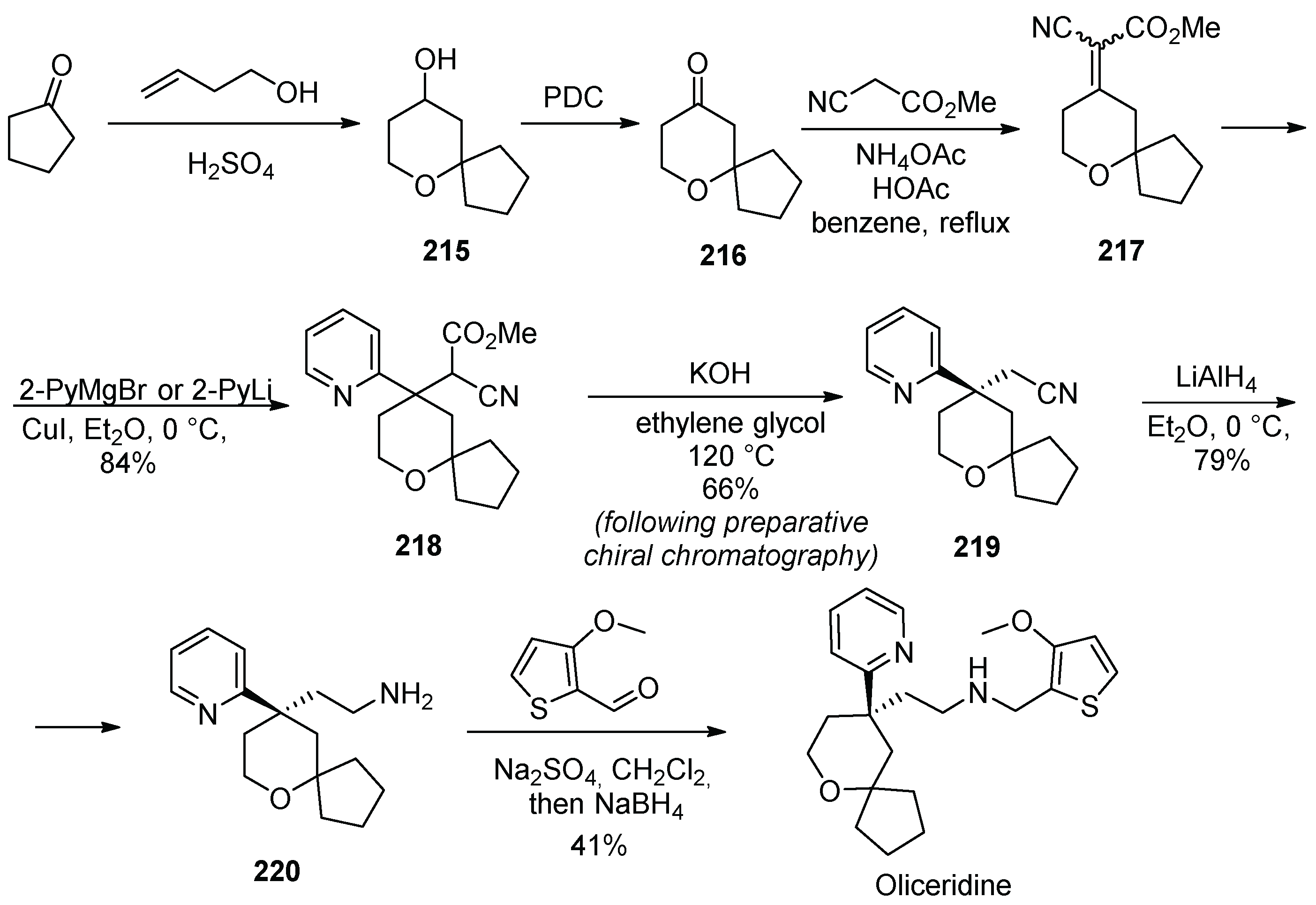

21. Oliceridine

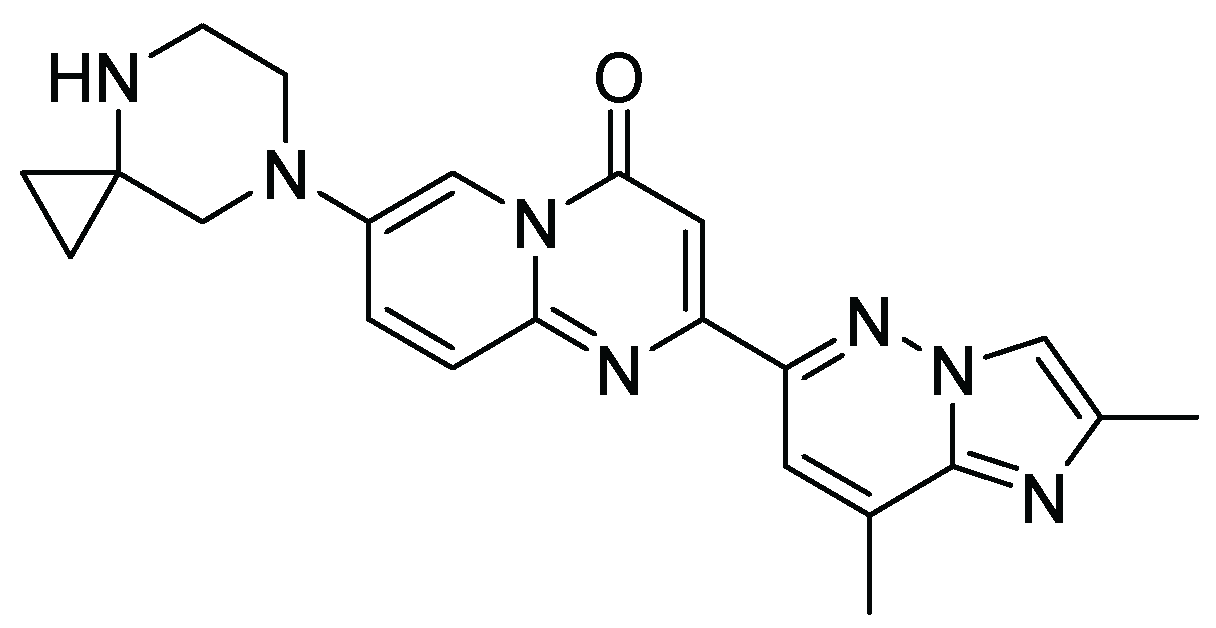

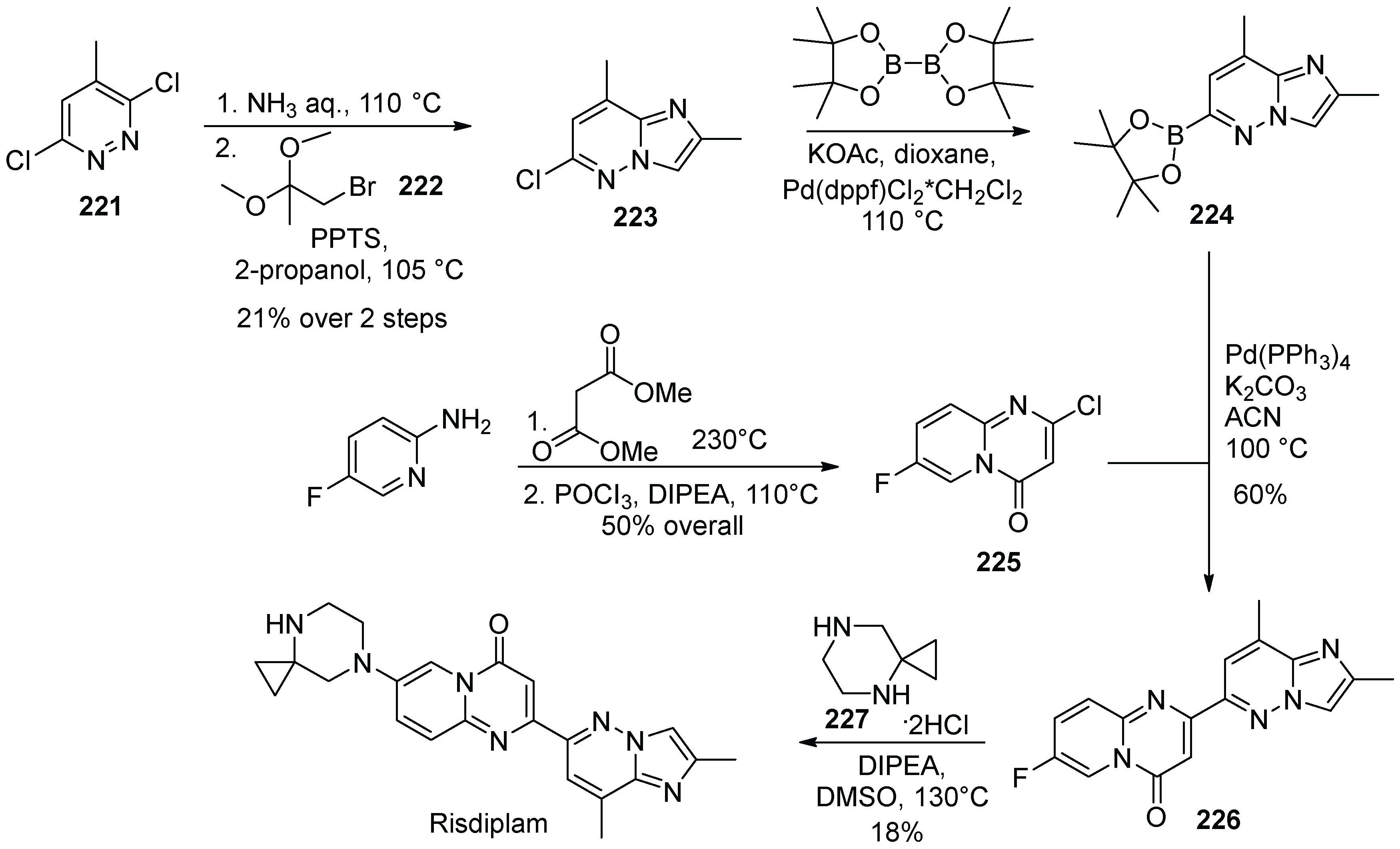

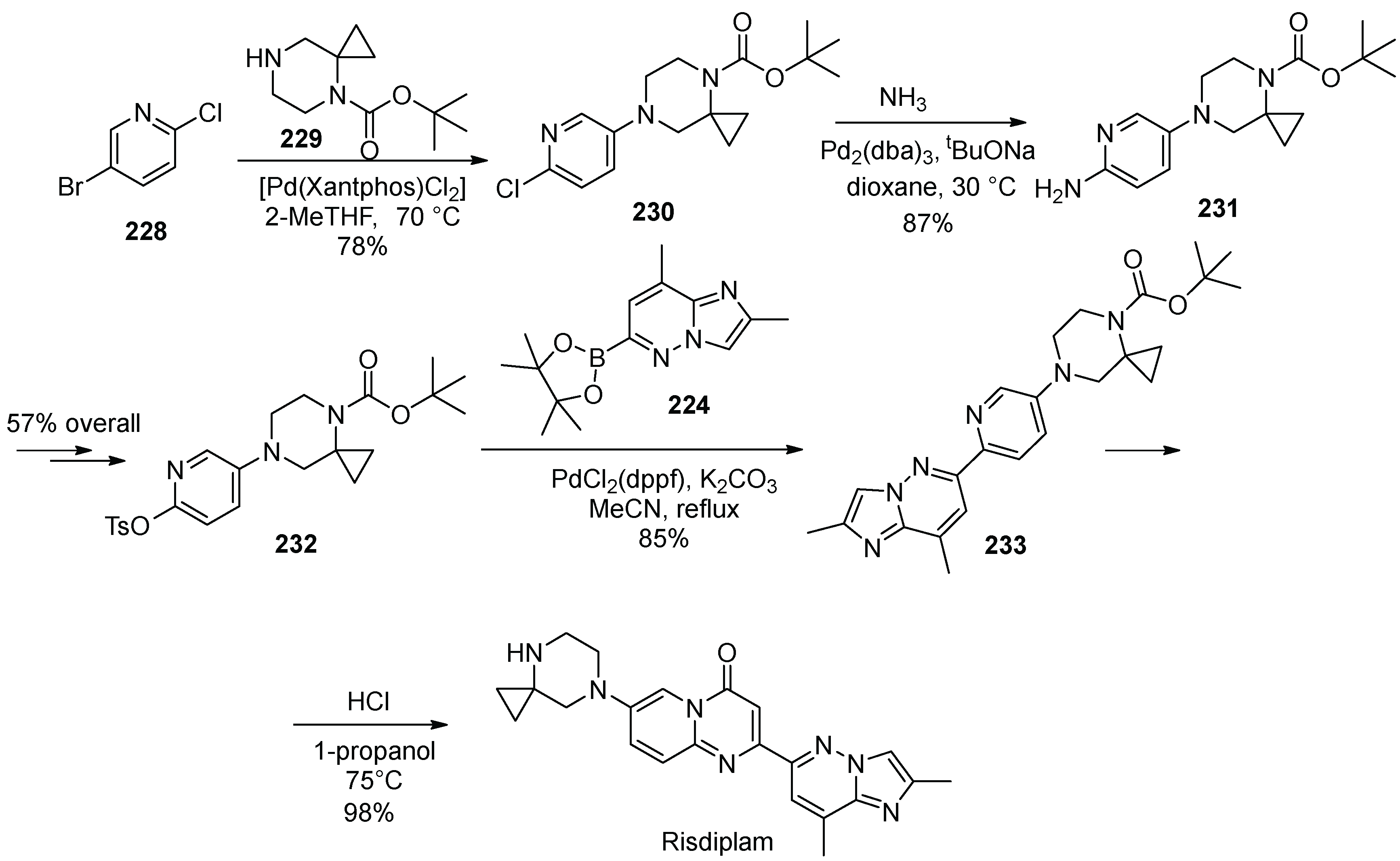

22. Risdiplam

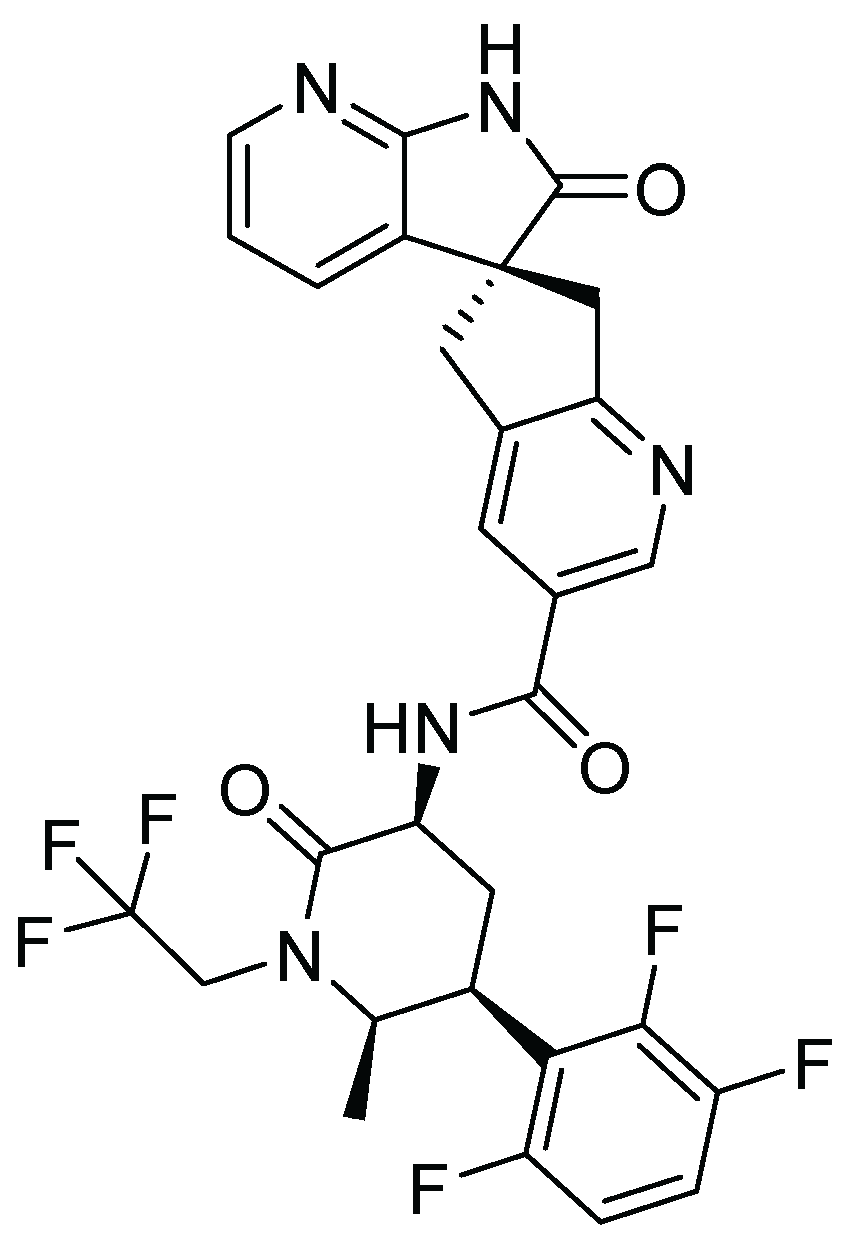

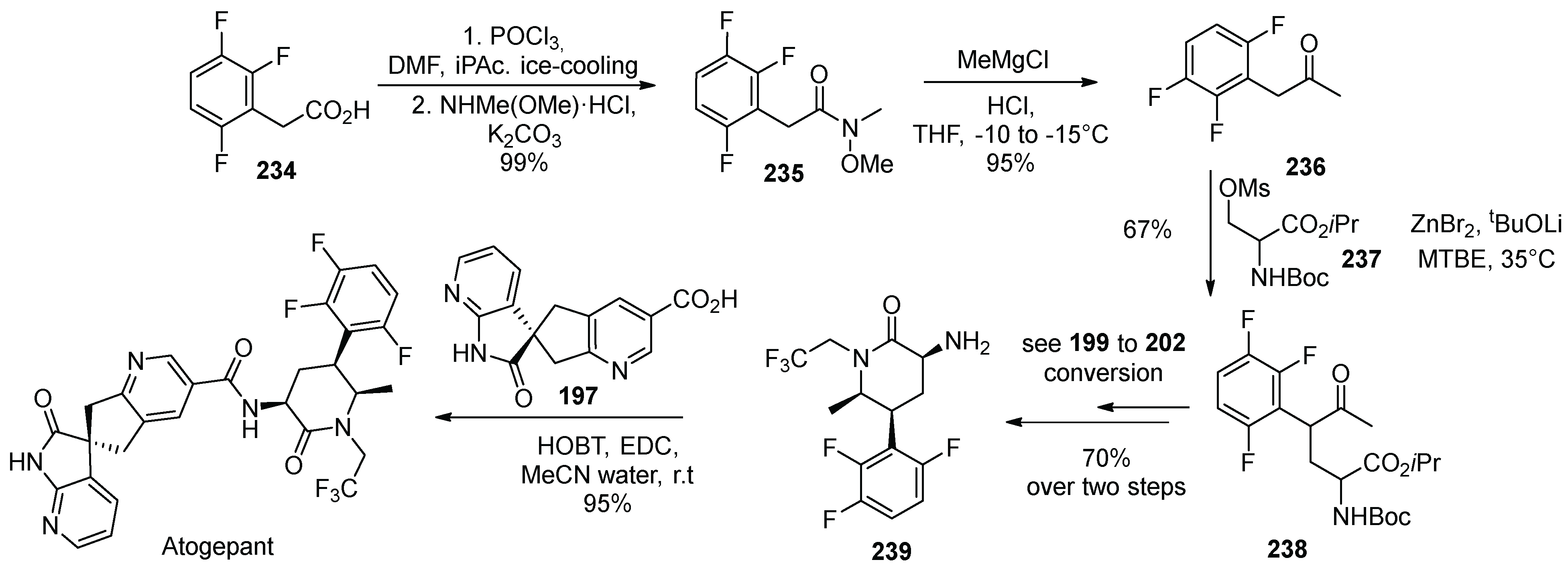

23. Atogepant

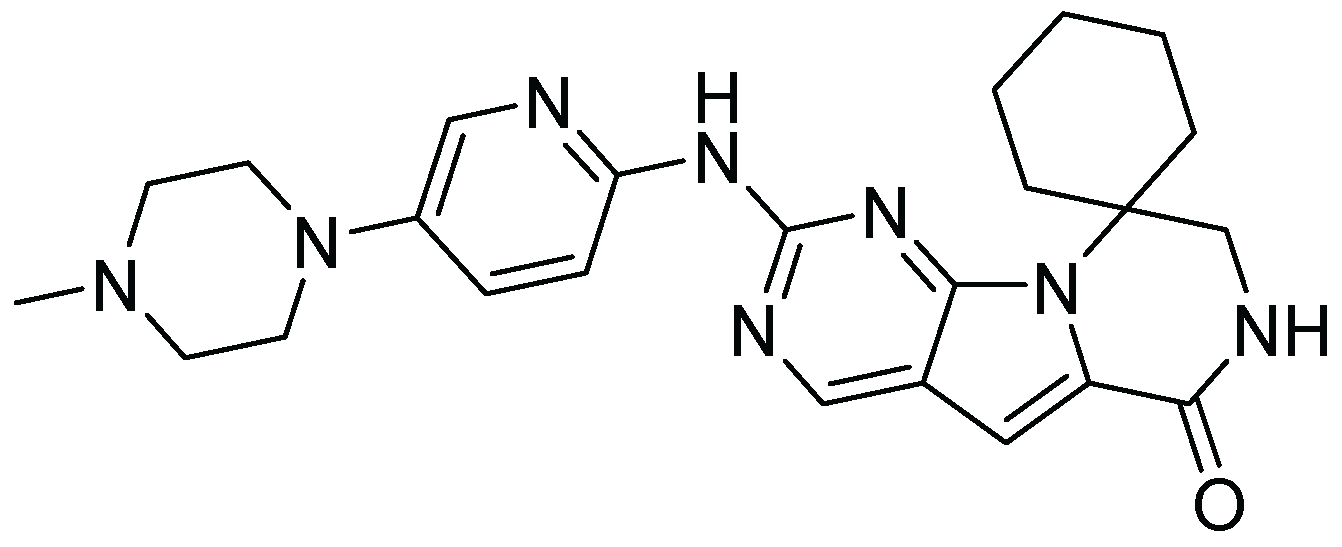

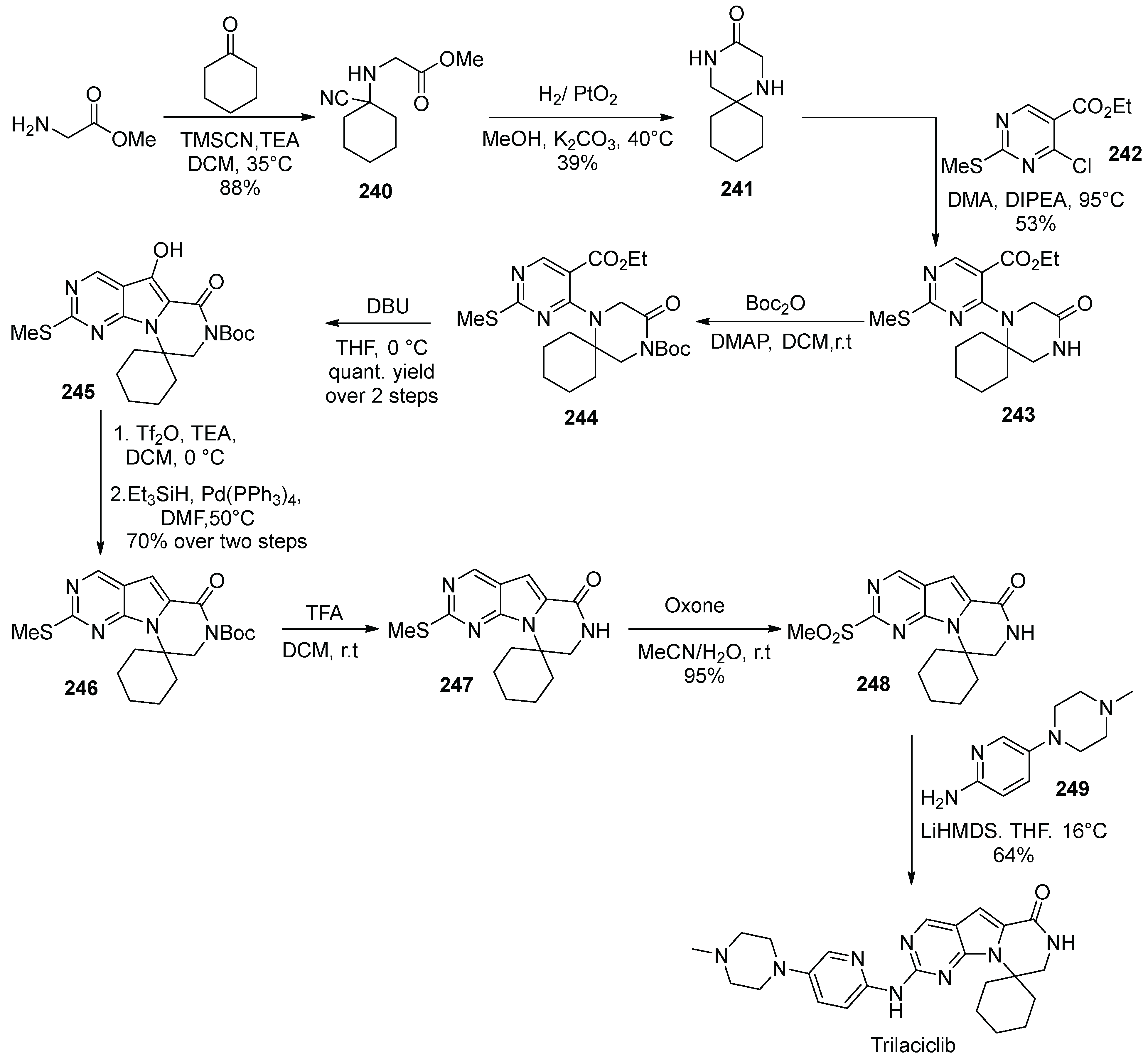

24. Trilaciclib

25. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Lovering, F.; Bikker, J.; Humblet, C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiesinger, K.; Dar’in, D.; Proschak, E.; Krasavin, M. Spirocyclic Scaffolds in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 150–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomozane, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Choshi, T.; Kishida, S.; Yamato, M. Syntheses and Antifungal Activities of dl-Griseofulvin and Its Congeners. I. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1990, 38, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrung, M.C.; Brown, W.L.; Rege, S.; Laughton, P. Total Synthesis of (+)-Griseofulvin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 8561–8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larik, F.A.; Saeed, A.; Shahzad, D.; Faisal, M.; El-Seedi, H.; Mehfooz, H.; Channar, P.A. Synthetic approaches towards the multi target drug spironolactone and its potent analogues/derivatives. Steroids 2017, 118, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, J.A.; Kagawa, C.M. Steroidal Lactones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 4808–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, J.A.; Brown, E.A.; Burtner, R.R. Steroidal Aldosterone Blockers. I. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, J.A.; Tweit, R.C. Steroidal Aldosterone Blockers. II1. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 1109–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anner, G.; Wehrli, H. Process for the Preparation of Steroid Carbolactones. Swiss Patent CH617443A5, 30 May 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wuts, P.G.M.; Ritter, A.R. A Novel Synthesis of Spironolactone. An Application of the Hydroformylation Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 5180–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, D.; Tanaka, H.; Hirata, A.; Tamura, Y.; Takahashi, D.; Takahashi, Y.; Nagamitsu, T.; Ohtawa, M. One-Pot γ-Lactonization of Homopropargyl Alcohols via Intramolecular Ketene Trapping. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 2831–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepnicki, P.; Kondej, M.; Kaczor, A.A. Current Concepts and Treatments of Schizophrenia. Molecules 2018, 23, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, P.A.; Niemegeers, C.J.; Schellekens, K.H.; Lenaerts, F.M.; Verbruggen, F.J.; van Nueten, J.M.; Marsboom, R.H.; Hérin, V.V.; Schaper, W.K. The pharmacology of fluspirilene (R 6218), a potent, long-acting and injectable neuroleptic drug. Arzneimittelroschung 1970, 20, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Morciano, G.; Preti, D.; Pedriali, G.; Aquila, G.; Missiroli, S.; Fantinati, A.; Caroccia, N.; Pacifico, S.; Bonora, M.; Talarico, A.; et al. Discovery of Novel 1,3,8-Triazaspiro[4.5]decane Derivatives That Target the c Subunit of F1/FO-Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Synthase for the Treatment of Reperfusion Damage in Myocardial Infarction. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 7131–7143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botteghi, C.; Marchetti, M.; Paganelli, S.; Persi-Paoli, F. Rhodium catalyzed hydroformylation of 1,1-bis(p-fluorophenyl)allyl or propargyl alcohol: A key step in the synthesis of Fluspirilen and Penfluridol. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xia, H.; Cai, Y.; Ma, D.; Yuan, J.; Yuan, C. Synthesis and SAR study of diphenylbutylpiperidines as cell autophagy inducers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanet, P.; Stewart, A.G. Value of Fenspiride in the Treatment of Inflammation Diseases in Otorhinolaryngology. Eur. Respir. Rev. 1991, 1, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, J.I.; Perozo, E.; Allen, T.W. Towards a structural view of drug binding to hERG K+ channels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniowska, B.; Holbrook, M.; Pollard, C.; Polak, S. Utilization of mechanistic modelling and simulation to analyse fenspiride proarrhythmic potency—Role of physiological and other non-drug related parameters. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2022, 47, 2152–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taccone, I. Method for the Preparation of Derivatives of Spiro[4,5]decane and Derivatives Thus Obtained. US Patent 4,028,351, 7 June 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Somanathan, R.; Rivero, I.A.; Nunez, G.I.; Hellberg, L.H. Convenient synthesis of 1-oxa-3,8-diazaspiro[4,5]decan-2-ones. Synth. Commun. 1994, 24, 1387–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, C.; Bapat, K.; Patil, P.; Kotharkar, S.; More, Y.; Gotrane, D.; Chaskar, M.U.; Tripathy, N.K. Nitro-Aldol Approach for Commercial Manufacturing of Fenspiride Hydrochloride. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2019, 23, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, A.; Talbot, A.; Caillé, F.; Chevalier, A.; Sallustrau, A.; Loreau, O.; Destro, G.; Taran, F.; Audisio, D. Carbon isotope labeling of carbamates by late-stage [11C], [13C] and [14C]carbon dioxide incorporation. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 11677–11680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, R.; Barry, B.W.; Frosch, P.J. Activity and Bioavailability of Amcinonide and Triamcinolone Acetonide in Experimental and Proprietary Topical Preparations. Curr. Ther. Res. 1977, 21, 877–886. [Google Scholar]

- Shultz, W.; Sieger, G.M.; Krieger, C. Novel Triamcinolone Derivative. Brittish Patent GB1442925, 14 July 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Trimathi, V.; Kumar, R.; Bhuwania, R.; Bhuwania, B.K. Novel Process for Preparation of Corticosteroids. PCT Int. Appl. WO2018037423, 1 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty, F.A.; Brogden, R.N. Guanadrel. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in hypertension. Drugs 1985, 30, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardanyan, R.S.; Hruby, V.J. 12—Adrenoblocking Drugs. In Synthesis of Essential Drugs; Vardanyan, R.S., Hruby, V.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hardie, W.R.; Aaron, J.E. 1,3-Dioxolan-4-yl-alkyl Guanidines. US Patent 3,547,951, 15 December 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T.J.; Goodman, M. Synthesis of Biologically Important Guanidine-Containing Molecules Using Triflyl-Diurethane Protected Guanidines. Synthesis 1999, 1999, 1423–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.P.; Moon, S.L. Buspirone and Related Compounds as Alternative anxiolytics. Neuropeptides 1991, 19, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Rayburn, J. N-(Heteroarcyclic)piperazinylalkylazaspiroalkanediones. US Patent 3,717,634, 20 February 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.H.; Rayburn, J.W. N-[(4-Pyridyl-piperazino)alkyl]azaspiroalkanediones. US Patent 3,907,801, 23 September 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.H.; Rayburn, J.W. Tranquilizer Process Employing N-(heteroarcyclic)piperazinylalkylazaspiroalkanediones. US Patent 3,976,776, 24 August 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, J.; Zong, Z.-M.; Wei, X.-Y. Facile synthesis of anxyolytic buspirone. Org. Prep. Proc. Int. 2008, 40, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labes, R.; Mateos, C.; Battilocchio, C.; Chen, Y.; Dingwall, P.; Cumming, G.R.; Rincon, J.A.; Nieves-Remacha, M.J.; Ley, S.V. Fast continous alcohol amination employing a hydrogen borrowing protocol. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekhar, V.G.; Baumann, W.; Beller, M.; Jagadeesh, R.V. Nickel-catalyzed hydrogenative coupling of nitriles and amines for general amine synthesis. Science 2022, 376, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.C. Ivermectin as an antiparasitic agent for use in humans. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 1991, 45, 445–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, A. Ivermectin: Enigmatic multifaceted ߢwonderߣ drug continues to surprise and exceed expectations. J. Antibiotics 2017, 70, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.J.; Robertson, A.P.; Choudhary, S. Ivermectin: An Anthelmintic, an Insecticide, and Much More. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneux, D.H.; Ward, S.A. Reflections on the Nobel Prize for Medicine 2015—The Public Health Legacy and Impact of Avermectin and Artemisinin. Trends Parasitol. 2015, 31, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlt, D.; Bonse, G.; Reisewitz, F. Method for the Preparation of Ivermectin. Eur. Patent EP072997, 4 September 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, S.; Hayashi, D.; Nakano, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Hirama, M. Total synthesis of avermectin B1a revisited. J. Antibiotics 2016, 69, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothstein, D.M. Rifamycins, Alone and in Combination. Cold Spring Harb. Perpect. Med. 2016, 6, a027011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri, M.J.; Ebrahimi, G.; Arefzadeh, S.; Zamani, S.; Nikpor, Z.; Mirsaeidi, M. Antibiotic therapy success rate in pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M.; Nunes, C.; Caio, J.M.; Lucio, M.; Brezesinski, R.S. The Influence of Rifabutin on Human and Bacterial Membrane Models: Implications for Its Mechanism of Action. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 6187–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, L.; Pasqualucci, C.; Vigevani, A.; Gioia, B.; Schioppacassi, G.; Oronzo, G. New rifamycins modified at positions 3 and 4. Synthesis, structure and biological evaluation. J. Antiobiot. 1981, 34, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, L.; Rosetti, V.; Pasqualucci, C. Method of preparing derivatives of rifamycin S. US Patent 4,007,169, 8 December 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S.; Sorkin, E.M. Spirapril: A Preliminary Review of its Pharmacology and Therapeutic Efficacy in the Treatment of Hypertension. Drugs 1995, 49, 750–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein-Nia, M.; Surve, A.H.; Weglein, R.; Gerbeau, C.; Holt, D.W. Radioimmunoassays for spirapril and its active metabolite spiraprilate: Performance and application. Ther. Drug Monit. 1992, 14, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, E.H.; Neustadt, B.R.; Smith, E.M. 7-Carboxyalkylaminoacyl-1,4-dithia-7-azaspiro[4.4]-nonane-8-carboxylic Acids. US Patent 4,470,972, 11 September 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.M.; Swiss, G.F.; Neustadt, B.R.; McNamara, P.; Gold, E.H.; Sybertz, E.J.; Baum, T. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: Spirapril and Related Compounds. J. Med. Chem. 1989, 32, 1600–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapcho, J.; Turk, C.; Cushman, D.W.; Powell, J.R.; DeForrest, J.M.; Spitzmiller, E.R.; Karanewsky, D.S.; Duggan, M.; Rovnyak, G.; Schwartz, J.; et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Mercaptan, Carboxyalkyl Dipeptide, and Phosphinic Acid Inhibitors Incorporating 4-Substituted Prolines. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, 1148–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muszalska, I.; Sobczak, D.A.; Jelinska, A. Analysis of Sartans: A review. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 103, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siragy, H. Angiotensin II receptor blockers: Review of the binding characteristics. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999, 84, 3S–8S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhart, C.A.; Perreaut, P.M.; Ferrari, B.P.; Muneaux, Y.A.; Assens, J.-L.A.; Clement, J.; Haudricourt, F.; Muneaux, C.F.; Taillades, J.E.; Vignal, M.-A.; et al. A New Series of Imidazolones: Highly Specific and Potent Nonpeptide AT1Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 3371–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPoto, M.C.; Wu, J. Synthesis of 2-Aminoimidazolones and Imidazolones by (3 + 2) Annulation of Azaoxyallyl Cations. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisnevich, G.; Rukhman, I.; Pertsikov, B.; Kaftanov, J.; Dolitzky, B.-Z. Novel Synthesis of Irbesartan. US Patent Appl. US2004192713, 30 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, R.B.; Suhakar, S.; Sridhar, C.; Rao, S.N.; Venkataraman, S.; Reddy, P.P.; Satyanarayana, B. Process for Preparing Irbesartan. PCT Int. Appl. WO2005113518, 1 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, P.; Sargent, K.; Stewart, E.; Liu, J.-F.; Yohannes, D.; Yu, L. Novel and Expeditious Microwave-Assisted Three-Component Reactions for the Synthesis of Spiroimidazolin-4-ones. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3137–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Niu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Qiao, R. Development of a New Synthetic Route of the Key Intermediate of Irbesartan. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 2438–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Niki, H. Review of the Pharmacological Properties and Clinical Usefulness of Muscarinic Agonists for Xerostomia in Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome. Clin. Drug Investig. 2002, 22, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Takamura, E.; Shinozaki, K.; Tsumura, T.; Hamano, T.; Yagi, Y.; Tsubota, K. Therapeutic effect of cevimeline on dry eye in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: A randomized, double-blind clinical study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 138, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksak, P.; Novotny, M.; Patocka, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Hort, J.; Pavlik, J.; Klimova, B.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K. Neuropharmacology of Cevimeline and Muscarinic Drugs—Focus on Cognition and Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; Karton, I.; Heldman, E.; Levy, A.; Grunfeld, Y. Derivatives of quinuclidine. US Patent 4,855,290, 8 August 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bratovanov, S.; Bejan, E.; Wang, Z.-X.; Horne, S. Process for the Preparation of 2-Methylspiro(1,3-oxathiolane-5,3߰)quiniclidine. US Patent Appl. US2008249312, 9 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik, C.; Patil, P.; Kotharkar, S.; Tripathy, N.K.; Gurjar, M.K. A new route to cevimeline. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 3043–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bös, M.; Canesso, R. EPC-synthesis of (S)-3-hydroxy-3-mercaptomethylquinucudine, a chiral building block for the synthesis of the muscarinic agonist AF1028. Heterocycles 1994, 38, 1889–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Remme, W.; Zannad, F.; Neaton, J.; Martinez, F.; Roniker, B.; Bittman, R.; Hurley, S.; Kleiman, J.; Gatlin, M. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, J. The 45-year story of the development of an anti-aldosterone more specific than spironolactone. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004, 217, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, J.S.; Liu, C.; Anderson, D.K.; Lawson, J.P.; Wieczorek, J.; Kunda, S.A.; Letendre, L.J.; Pozzo, M.J.; Sing, Y.-L.L.; Wang, P.T.; et al. Processes for Preparation of 9,11-Epoxy Steroids and Intermediates Useful Therein. PCT Int. Appl. WO9825948, 18 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grob, J.; Boillaz, M.; Schmidlin, J.; Wehrli, H.; Wieland, P.; Fuhrer, H.; Rihs, G.; Joss, U.; de Gasparo, M.; Haenni, H.; et al. Steroidal, Aldosterone Antagonists: Increased Selectivity of 9α,11-Epoxy Derivatives. Helv. Chim. Acta 1997, 80, 566–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, B.A.; Padilla, A.G.; Hach, J.T.; Havens, J.L.; Pillai, M.D. A New Approach to the Furan Degradation Problem Involving Ozonolysis of the trans-Enedione and Its Use in a Cost-Effective Synthesis of Eplerenone. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2111–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, H.; Feng, H.; Li, Y. Stereoselective construction of a steroid 5a,7a-oxymethylene derivative and its use in the synthesis of eplerenone. Steroids 2011, 76, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krattenmacher, R. Drospirenone: Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of a unique progestogen. Contraception 2000, 62, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhn, P.; Fuhrmann, U.; Fritzemeier, K.H.; Krattenmacher, R.; Schillinger, E. Drospirenone: A novel progestogen with antimineralocorticoid and antiandrogenic activity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1995, 761, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittler, D.; Hofmeister, H.; Laurent, H.; Nickisch, K.; Nickolson, R.; Petzoldt, K.; Wiechert, R. Synthesis of Spirorenone- A Novel Highly Active Aldosterone Antagonist. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1982, 21, 696–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickisch, K.; Acosta, K.; Santhamma, B. Methods for the Preparation of Drospirenone. US Patent Appl. US2010261896, 14 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bandini, M.; Contento, M.; Garelli, A.; Monari, M.; Tolomelli, A.; Umani-Ronchi, A.; Andriolo, E.; Montorsi, M. A Nonclassical Stereoselective Semi-Synthesis of Drospirenone via Cross-Metathesis Reaction. Synthesis 2008, 2008, 3801–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.J. Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir: A Review in Chronic Hepatitis C. Drugs 2018, 78, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.W.; Vitale, J.P.; Matthews, K.S.; Teresk, M.G.; Formella, A.; Evans, J.W. Synthesis of Antiviral Compound. US Patent Appl. US20130324740, 5 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Liu, F.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, W.-J.; Liu, Z.-L.; Lv, Y.; Yu, H.-Z.; Xu, J.; Dai, J.-J.; Xu, H.-J. The amine-catalysed Suzuki–Miyaura-type coupling of aryl halides and arylboronic acids. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.-A.; Deeks, E.D. Rolapitant: A Review in Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting. Drugs 2017, 77, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliwal, S.; Reichard, G.A.; Wang, C.; Xiao, D.; Tsui, H.-C.; Shih, N.-Y.; Arredondo, J.D.; Wrobleski, M.L.; Palani, A. NK1 Antagonists. US Patent 7,049,320, 23 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, M.; Fang, Z.; Ma, X.; Huffman, J.C. New methodology for the synthesis of α,α--dialkylamino acids using the “self-regeneration of stereocenters” method: α-ethyl-α-phenylglycine. Heterocycles 1997, 46, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergelsberg, I.; Scherer, D.H.; Huttenloch, M.E.; Tsui, H.-C.; Paliwal, S.; Shih, N.-Y. Process and Intermediates for the Synthesis of 8-[{1-(3,5-bis-(thrifluoromethyl)phenyl)ethoxy}methyl]-8-phenyl-1,7-diazadpiro[4,5]decan-2-one Compounds. US Patent 8,552,191, 8 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.G.; Werne, G.; Fu, X.; Orr, R.K.; Chen, F.X.; Cui, J.; Sprague, V.M.; Zhang, F.; Xie, J.; Zeng, L.; et al. Process and Intermediates for the Synthesis of 8-[{1-(3,5-bis-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-ethoxy}-methyl]-8-phenyl-1,7-diaza-spiro[4.5]decan-2-one Compounds. US Patent 9,249,144, 2 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.L. Review of Synthetic Routes and Crystalline Forms of the Antiandrogen Oncology Drugs Enzalutamide, Apalutamide, and Darolutamide. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.E.; Sawyers, C.L.; Ouk, S.; Tran, C.; Wongvipat, J. Androgen Receptor Modulator for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer and Androgen Receptor-Associated Diseases. PCT. Int. Patent Appl. WO 2007126765, 8 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ouerfelli, O.; Dilhas, A.; Yang, G.; Zhao, H. Synthesis of Thiohydantoins. PCT. Int. Patent Appl. WO 2008119015, 2 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y. Synthesis Method of Apalutamide and Its Intermediates. Chinese Patent CN108383749, 10 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Takiguchi, Y.; Mishima, H.; Okuda, M.; Terao, M. Milbemycins, a new family of macrolide antibiotics: Fermentation, isolation and physico-chemical properties. J. Antibiot. 1980, 23, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, R.K.; Geary, T.G. Perspectives on the utility of moxidectin for the control of parasitic nematodes in the face of developing anthelmintic resistance. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2019, 10, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, P.; Hamley, J.I.D.; Walker, M.; Basáñez, M.G. Moxidectin: An oral treatment for human onchocerciasis. Exp. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiguchi, Y.; Ono, M.; Muramatsu, S.; Ide, J.; Mishima, H.; Terao, M. Milbemycins, a new family of macrolide antibiotics. Fermentation, isolation and physico-chemical properties of milbemycins D., E, F, G, and H. J. Antibiot. 1983, 36, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulding, D.R.; Kumar, A. Process for the Preparation of 23-(C1–C6 Alkyloxime)-LL-F28249 Compounds. US Patent 4,988,824, 29 January 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, F.A.; King, R.; Smillie, S.J.; Kodji, X.; Brain, S.D. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: Physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 1099–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.; Fraley, M.E.; Bell, I.M.; Burgey, C.S.; White, R.B.; Li, C.C.; Rega, C.P.; Danziger, A.; Michener, M.S.; Hostetler, E.; et al. Characterization of Ubrogepant: A Potent and Selective Antagonist of the Human Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 373, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, N.; Cleator, E.; Kosjek, B.; Yin, J.; Xiang, B.; Chen, F.; Kuo, S.-C.; Belyk, K.; Mullens, P.R.; Goodyear, A.; et al. Practical Asymmetric Synthesis of a Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Receptor Antagonist Ubrogepant. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2017, 21, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, L. Phase-Transfer-Catalyzed Asymmetric Annulations of Alkyl Dihalides with Oxindoles: Unified Access to Chiral Spirocarbocyclic Oxindoles. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.S.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Rajagopal, S. Biased signalling: From simple switches to allosteric microprocessors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, A. Oliceridine: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 1739–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, D.; Gotchev, D.; Pitis, P.; Chen, X.-T.; Liu, G.; Yuan, C.C.K. Opioid Receptor Ligands and Methods of Using and Making Same. PCT Int. Appl. WO2012129495, 27 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hanschke, E. Zur Kenntnis der Prinsschen Reaktion, III. Mitteil.1: Über die Reaktion von Allylcarbinol mit Aldehyden und Ketonen. Chem. Ber. 1955, 88, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, A.; Mercuri, E.; Tiziano, F.D.; Bertini, E. Spinal muscular atrophy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Risdiplam: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 1853–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratni, H.; Scalco, R.S.; Stephan, A.H. Risdiplam, the First Approved Small Molecule Splicing Modifier Drug as a Blueprint for Future Transformative Medicines. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 874–877. [Google Scholar]

- Ratni, H.; Green, L.; Naryshkin, N.A.; Weetall, M.L. Compounds for Treating Spinal Muscular Atrophy. PCT Int. Appl. WO2015173181, 19 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, J.-M.; Fantasia, S.M.; Fishlock, D.V.; Hoffmann-Emery, F.; Moine, G.; Pfleger, C.; Moessner, C. Process for the Prepration of 7-(4,7-diazaspiro[2.5]octan-7-yl)-2-(2,8-dimethylimidazo[1,2-b]pyridazin-6-yl)pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one Derivatives. PCT Int. Appl. 2019057740, 28 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ailani, J.; Lipton, R.B.; Goadsby, P.J.; Guo, H.; Miceli, R.; Severt, L.; Finnegan, M.; Trugman, J.M.; ADVANCE Study Group. Atogepant for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Molinaro, C.; Wuelfing, W.P.; Yasuda, N.; Yin, J.; Zhong, Y.-L.; Lynch, J.; Andreani, T. Process for Making CGRP Receptor Antagonists. US Patent Appl. US2016130273, 12 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, S. Trilaciclib: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpless, N.E.; Strum, J.C.; Bisi, J.E.; Roberts, P.J.; Tavares, F.X. Highly Active Anti-Neoplastic and Anti-Proliferative. Agents. Patent No. WO2014144740A2, 18 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; White, H.S.; Tavares, F.X.; Krasutsky, S.; Chen, J.-X.; Dorrow, R.L.; Zhong, H. Synthesis of N-(Heteroaryl)Pyrrolo[3,2-d]Pyrimidin-2-Amines. Patent No. WO2018005865A1, 4 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

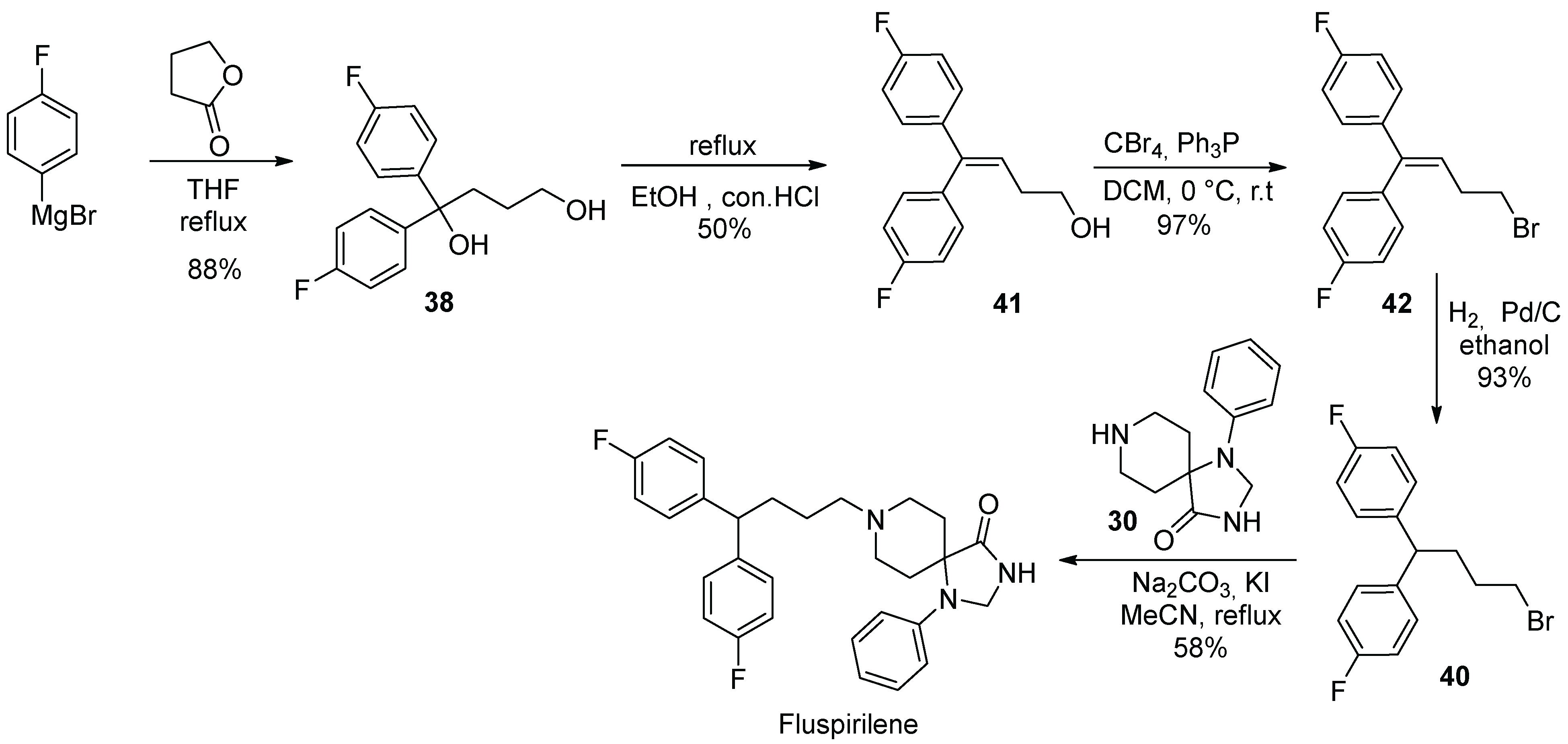

| Entry | Drug Name | Year of Approval | Origin of Spirocycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Griseofulvin | 1959 | Cycloaddition, intramolecular Claisen condensation |

| 2 | Spironolactone | 1960 | Lactonization |

| 3 | Fluspirilene | 1970 | Cyclocondensation |

| 4 | Fenspiride | 1970 | Lactamization |

| 5 | Amcinonide | 1979 | Ketalization |

| 6 | Guanadrel | 1979 | Ketalization |

| 7 | Buspirone | 1986 | Commercially available spiro building block |

| 8 | Ivermectin | 1986 | Biosynthesis |

| 9 | Rifabutin | 1992 | Cyclocondensation |

| 10 | Spirapril | 1995 | Thioketalization |

| 11 | Irbesartan | 1997 | Cyclocondensation |

| 12 | Cevimeline | 2000 | Acetalization |

| 13 | Eplerenone | 2002 | Biosynthesis |

| 14 | Drospirenone | 2000 | Lactonization |

| 15 | Ledipasvir | 2014 | Cyclopropanation |

| 16 | Rolapitant | 2015 | Lactamization, ring-closing metathesis |

| 17 | Apalutamide | 2018 | Lactonization |

| 18 | Moxidectin | 2018 | Biosynthesis |

| 19 | Ubrogepant | 2020 | Intramolecular C-alkylation |

| 20 | Oliceridine | 2020 | Prins reaction |

| 21 | Risdiplam | 2020 | Commercially available spiro building block |

| 22 | Atogepant | 2021 | Intramolecular C-alkylation |

| 23 | Trilaciclib | 2021 | Intramolecular Claisen condensation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moshnenko, N.; Kazantsev, A.; Chupakhin, E.; Bakulina, O.; Dar’in, D. Synthetic Routes to Approved Drugs Containing a Spirocycle. Molecules 2023, 28, 4209. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28104209

Moshnenko N, Kazantsev A, Chupakhin E, Bakulina O, Dar’in D. Synthetic Routes to Approved Drugs Containing a Spirocycle. Molecules. 2023; 28(10):4209. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28104209

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoshnenko, Nazar, Alexander Kazantsev, Evgeny Chupakhin, Olga Bakulina, and Dmitry Dar’in. 2023. "Synthetic Routes to Approved Drugs Containing a Spirocycle" Molecules 28, no. 10: 4209. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28104209

APA StyleMoshnenko, N., Kazantsev, A., Chupakhin, E., Bakulina, O., & Dar’in, D. (2023). Synthetic Routes to Approved Drugs Containing a Spirocycle. Molecules, 28(10), 4209. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28104209