Abstract

CA (cyclosporine A) is a powerful immunosuppressing agent that is commonly utilized for treating various autoimmune illnesses and in transplantation surgery. However, its usage has been significantly restricted because of its unwanted effects, including nephrotoxicity. The pathophysiology of CA-induced kidney injury involves inflammation, apoptosis, tubular injury, oxidative stress, and vascular injury. Despite the fact that exact mechanism accountable for CA’s effects is inadequately understood, ROS (reactive oxygen species) involvement has been widely proposed. At present, there are no efficient methods or drugs for treating CA-caused kidney damage. It is noteworthy that diverse natural products have been investigated both in vivo and in-vitro for their possible preventive potential in CA-produced nephrotoxicity. Various extracts and natural metabolites have been found to possess a remarkable potential for restoring CA-produced renal damage and oxidative stress alterations via their anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative potentials. The present article reviews the reported studies that assess the protective capacity of natural products, as well as dietary regimens, in relation to CA-induced nephrotoxicity. Thus, the present study presents novel ideas for designing and developing more efficient prophylactic or remedial strategies versus CA passive influences.

1. Introduction

The kidneys are vital organs that play an important role in removing waste and toxic materials from the blood, maintain electrolyte balance, and regulate the homeostasis of blood plasma, blood volume, blood pressure, and red blood cell genesis. The kidneys can be damaged or may become totally inactive due to several factors, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, ischemia/reperfusion injury, diabetes, and nephrotoxic agents, most often various modern drugs that are in use at present [1]. Just as some natural products are a source of substances that protect the kidneys, there are several plants known for their harmful effects on the kidneys, leading to renal dysfunction, ranging from acute to chronic renal failure and death. The herbal medicines mostly associated with nephrotoxicity are: Dioscorea quinqueloba, Lawsonia inermis, Cassia senna L., Artemisia herba-alba, Chenopodium polyspermum, Cape aloes, Euphorbia paralias, Crataegus orientalis, Colchicum autumnale, and Tribulus terrestris [2]. Additionally, in Persian medicine, a total of 64 plants that cause kidney damage have been reported, out of which Allium schoenoprasum and Marrubium vulgare were the most common nephrotoxic plants, but without relevant scientific evidence. Asafetida, garlic, saffron, and wormwood have been reported for their therapeutic effects on the kidneys, in addition to their kidney-damaging potential. Meanwhile, Cymbopogon citratus, Amaranthus spp., and Artemisia absinthium have been known to cause a direct nephrotoxic effect [3]

Nephrotoxicity is the condition in which the kidneys cannot properly detoxify and excrete drugs and toxic chemicals due to their destruction or damage caused by endo- or exogenous toxicants [4]. This is distinguished by increasing serum creatinine and urea and reducing the rate of GFR (glomerular filtration), and may be accompanied by arterial hypertension. Histologically, renal pathological changes occur, such as the swelling of the tubular cells, necrosis, arterial changes, and interstitial fibrosis [5]. Nephrotoxicity is frequently caused by a variety of drugs and chemicals, or environmental pollutants. Drugs cause approximately twenty five percent of nephrotoxicity, which can increase up to 66% in elderly people [6].

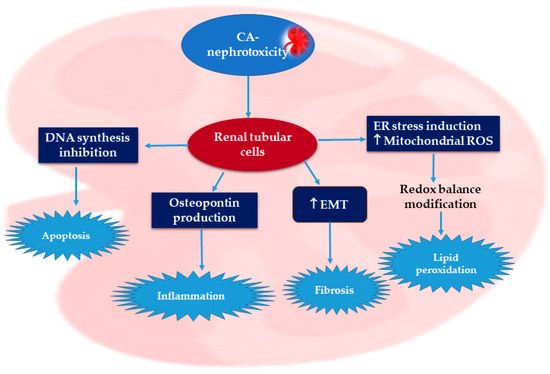

Cyclosporine A (CA), a cyclic peptide consisting of eleven amino acids, is purified from Topocladium inflatum fungus. CA is a potent immuno-suppressive agent that is commonly utilized to prohibit transplanted-organ rejection [7]. In solid-organ transplantation, CA significantly improves long-term survival rates [8]. Moreover, CA is utilized to manage varied autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and nephritic syndrome, as well as dermatological disorders [9]. However, CA has a narrow therapeutic index and its metabolism is performed by hepatic cytochrome (CYP450 3A 4/5) [10]. Nephrotoxicity is one of the serious adverse effects that limit the therapeutic uses of CA. Several reports have discussed the mechanisms by which CA induces nephrotoxicity [11,12]. The CA-nephrotoxicity-involved mechanism has not yet been completely elucidated. In 2017, a report by Lai et al. indicated that CA mediated renal damage through many mechanisms, involving the generation of inflammation, oxidative stress (OS), autophagy, and apoptosis [13] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms of cyclosporine A nephrotoxic effects [13,14,15].

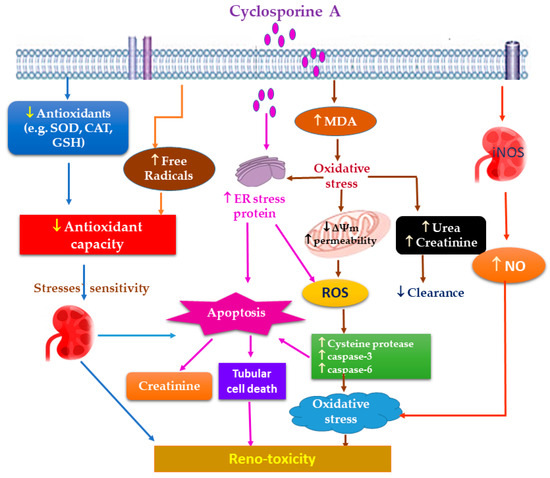

Numerous evidence reveals that ROS overproduction and OS have a definitive role in CA renal pathogenesis [13,14,15]. Briefly, CA promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress and increases the production of mitochondrial ROS (reactive oxygen species), resulting in redox balance alteration, which causes lipid peroxidation (Figure 2) [11].

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanisms of CA oxidative stress-induced reno-toxicity.

It has been reported that diverse signaling pathways take part in CA-nephrotoxicity pathogenesis, such as ERK, p38, and JNK, whereas NF-κB represents a CA-target molecule. Moreover, Nrf2 regulates the cellular oxidative stress induced by CA, while renal fibrosis produced by CA is attributed to TGF-β1 (transforming growth-factor-b1) [11,16]. Generally, CA weakens endothelium-based relaxation and prohibits the synthesis of nitric oxide in the renal artery. The nephrotoxic effect of CA is exerted by targeting the epithelial cells of renal tubules and stimulates the EMT (epithelial–mesenchymal transition) in these cells, leading to inflammation-mediated fibrosis and finally kidney failure [17,18]. Moreover, it suppresses DNA synthesis and induces apoptosis in these cells [19]. Shi et al. stated that CA stimulates the production of vasoconstriction factors, such as ROS, RNS (reactive nitrogen species), TGF-β1, NO, angiotensin II, leukotriene, and thromboxane A2 [20]. Moreover, Wirestam et al. reported that CA can indirectly damage renal tubular cells via stimulating osteopontin production, which leads to injuring the renal cells [21]. Therefore, the strategy used to date for overcoming CA is either reducing its dosage or using a combination of CA and another drug. It is noteworthy that various natural metabolites are reported to have the capacity to ameliorate CA-mediated renal toxicity, such as phenolics, polysaccharides, and terpenoids. Thus, the rational use of natural products could assist in minimizing the toxicity of this drug. The current review mainly focuses on natural products that are capable of reducing CA-induced nephrotoxicity. This review introduces a positive perception of the role of natural products in the amelioration of CA-induced nephrotoxicity, thereby amending the treatment strategies for patients who receive CA and their possible implications for natural supplements or drug combinations. The literature was searched using different databases and publishers: Scopus, PubMed, Springer, Google-Scholar, MDPI, Elsevier, Wiley, Bentham, and JACS. The keywords utilized for the search included natural product + cyclosporine A + nephrotoxicity; reno-protective + natural products + cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxicity; and natural product + nephro-protection + cyclosporine A. No time limit for the publication date was set. A total of 108 articles are reviewed in this study. All the reported studies evaluating the effectiveness of potential natural reno-protective agents on CA-caused nephrotoxicity are summarized.

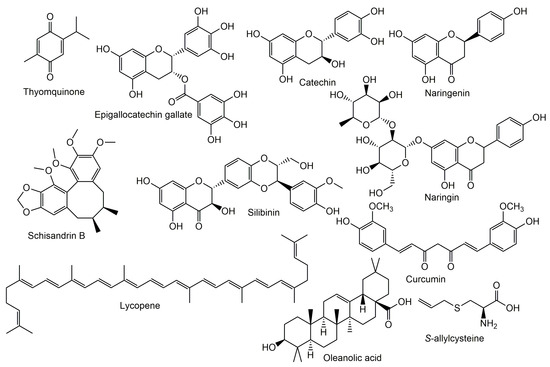

2. Phytoconstituents Prevent CA-Induced Nephrotoxicity

Different classes of phytochemicals were proved to improve the nephrotoxicity accompanying the use of cyclosporins (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of natural metabolites tested for reno-protective potential.

2.1. Phenolics and Polyphenols

2.1.1. Catechin

Catechin is a flavanol widely available in many foods and herbal products, especially in green tea extract (Table 1). Recent studies revealed that catechin has a dose-dependent nephro-protective effect on CA-induced nephrotoxicity [22]. The administration of CA in a dose of 20 mg/kg/day for twenty-one days markedly affected renal function, as indicated by the increase in renal creatinine and urea levels in rats. Catechin (100 mg/kg/day) co-administered with CA significantly ameliorated the nephrotoxic effect of CA as indicated by enhanced renal functions. On the other hand, lower doses of catechin (50 mg/kg/day) presented a milder protective effect than higher doses of the compound [22]. The prophylactic mechanism of catechin on CA-induced renal toxicity may be due to its antioxidant effect. Oxidative parameters, such as increased lipid peroxidation, decreased glutathione and superoxide dismutase levels, and increased catalase levels, were detected in rat kidney homogenate upon a chronic administration of CA. The co-administration of catechin (50 and 100 mg/Kg/day) with CA markedly enhanced all the previously mentioned oxidative stress parameters in a dose-dependent manner [22].

Table 1.

List of natural compounds evaluated for protective effects against CA-induced renal injury.

2.1.2. Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG)

EGCG is the most abundant catechin derivative in green tea with marked antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. It also has a prophylactic effect on neurodegenerative diseases and diabetes [38]. Similar to catechin, EGCG provides a significant protective effect on CA-induced nephrotoxicity mediated by its antioxidative effect [39]. Despite its biological activities, it has a poor pharmacokinetic property upon oral administration due to its unstable alkaline PH, poor intestinal permeability, and extensive pre-systemic metabolism. Italia et al. compared the effect of an EGCG nanoparticulate formulation on CA-induced nephrotoxicity in rats, in both orally and intraperitoneally administered compounds. I.P. (intra-peritoneal)-administered pure EGCG presented a significant protective effect, while the activity was diminished through the oral administration of the compound (Table 2). On the other hand, the oral administration of an EGCG nano-formulation presented a nephro-protective effect similar to that of an I.P.-administered drug due to its improved pharmacokinetic properties [38].

Table 2.

Protective effects of natural compounds on CA-induced renal injury.

2.1.3. Naringin

Naringin is a flavanone glycoside that mainly occurs in citrus fruits (Rutaceae), especially grapefruit. It has been reported that naringin is an effective reno-protective agent against CA-induced nephrotoxicity. Naringin can significantly decrease free-radical levels, including OH and lipid peroxidation, and increase antioxidant enzyme (e.g., SOD, GPx, and catalase) activity in renal tissues. Moreover, it can restore non-enzymatic antioxidants (GSH and vitamins C, E, and A). Additionally, it ameliorates the degeneration damage to kidneys induced by CA. Furthermore, the expression of HO-1 is maintained during naringin treatment, which may be the major reason for reno-protection [29].

2.1.4. Silibinin

Silibinin is one of the major flavonolignans in the hepatoprotective drug silymarin, with reported antioxidant activity and an inhibition of rat microsome lipid peroxidation. The effect of the administration of silibinin with CA on malondialdehyde levels in blood and kidney homogenate, in addition to the level of cytochrome p450, an enzyme that metabolizes CA into inactive metabolites, in microsomal liver suspension were estimated. MDA and creatinine levels were returned to normal by the co-administration of silibinin with CA. Interestingly, silibinin administration did not affect the glomerular filtration rate, but markedly increased cytochrome p450 levels compared to the CA group, suggesting its effect on cyclosporine biotransformation in the liver [47].

2.1.5. Ellagic Acid

Ellagic acid is a known phenolic constituent of many fruits and nuts, such as raspberries, strawberries, grapes, and walnuts [51]. It has been reported to present anti-oxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antimutagenic effects through its potent free-radical scavenging activity. The subcutaneous administration of ellagic acid (10 mg/kg) revealed a marked protective effect on liver and kidney functions compared to the CA group. Ellagic acid normalized MDA, catalase, and glutathione levels when co-administered with CA. These biochemical results were confirmed further through histopathological investigations [46]. This activity seemed to be dependent on the antioxidant activities of ellagic acid.

2.1.6. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is a natural phenolic compound formed by the esterification of caffeic acid with phenethyl alcohol. It represents a major component of propolis obtained from honeybees. CA-induced nephrotoxicity produced lipid peroxidation, MPO, SOD, and CAT activities in renal tissue. CAPE prevented an increase in MDA, but increased CAT and did not affect MPO and SOD. Therefore, CAPE may be an efficient agent to protect the kidneys from CA-induced damage via the inhibition of lipid peroxidation [36].

2.1.7. Resveratrol

Resveratrol is a polyphenolic compound that represents a major constituent in red grapes (Vitis vinifera, Vitaceae) [52]. It is known for its anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-glycation, hepatoprotective, and anti-cancer properties. Moreover, it can improve hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and diabetic complications. A study conducted by Chander et al. revealed that at doses of 5 and 10 mg/kg, resveratrol was able to improve renal dysfunction and renal and tissue nitric oxide levels, as well as renal oxidative stress. This protective effect was proved to be NO-dependent [37].

2.1.8. Provinol

Provinol is a mixture of polyphenolic compounds extracted from French red wine, involving (in mg/g of dry powder) 480 proanthocyanidins, 370 polymeric tannins, 61 total anthocyanins, 19 free anthocyanins, 38 catechins, 18 hydroxycinnamic acids, and 14 flavonols [53]. Provinol was observed to protect against CA-induced renal toxicity due to the antioxidant activity of its phenolic content [49,54]. However, the anti-apoptotic effect of phenolics on renal cells was clarified further in rats treated with CA, provinol, and a combination of both drugs for 21 days. CA markedly increased systolic blood pressure, decreased body weight, and increased serum creatinine and total protein levels. The administration of provinol with CA markedly protected the rats from nephrotoxicity, as indicated by the enhanced biochemical parameters. In addition, the CA group revealed alterations in and the translocation of Bax and cytochrome c levels from cytoplasm to mitochondria that activated the caspase-mediated apoptotic pathway. Provinol markedly inhibited this apoptotic cascade, which was concluded to be the reason for its nephro-protective effect [50]. Provinol could ameliorate a reduction in body weight and increased systolic blood pressure induced by rat treatment with CA. It also exerted a reduction in oxidative stress and iNOS expression via the NF-kB pathway [53].

2.1.9. Curcumin

Curcumin is a diarylheptanoid that represents a major active compound in the rhizomes of Curcuma longa (Zingiberaceae). It is traditionally recommended in the treatment of biliary and hepatic disorders and rheumatism. Previous biological studies proved its powerful antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects. Curcumin proved to present a significant protective effect against CA-induced nephrotoxicity in rats based on its ability to modify all histological changes and antioxidant effects via GST immuno-expression, decreasing TBARS and increasing levels of antioxidant enzymes (GSH, SOD, and CAT) [33,45]. Moreover, it was able to decrease serum creatinine levels and BUN, and improve creatinine clearance [44]. In another study, the treatment of HK-2 human renal cells with CA and different doses of curcumin [44] caused a dose-dependent reduction in ROS and MDA levels, in addition to increasing SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT levels. Moreover, it increased Bcl-2 and decreased Bax protein in HK-2 cells. Moreover, in vitro and in silico studies proved the ability of curcumin to ameliorate genotoxicity as well as DNA damage produced by the long-term use of CA [55]. The mechanism of this effect is based on the ability of curcumin to indirectly induce the expression of different anti-oxidant enzymes. Additionally, curcumin activated Nrf2-Keap1 that is responsible for the free-radical eradication from tissues through the expression of detoxifying enzymes [55].

2.2. Lignan Derivatives

Schisandrin B (ScB), a lignan derivative, was separated from Schisandra chinensis. This plant displayed beneficial values in treating hepatitis and regulating renal function [13]. Its extract had protective potential against nephrotoxicity caused by CA in rats [25]. ScB was reported to have a protective effect against cisplatin, gentamicin, and mercury-mediated nephrotoxicity [56,57,58] in rats. In a study on HK-2, the cyto-protective influence of ScB towards the CA nephrotoxic effect by assessing different parameters, such as LDH, GSH, ROS, and ΔΨm (mitochondrial membrane potential), as well as apoptosis and autophagy, was investigated [13]. It was revealed that the pre-incubation of HK-2 cells with ScB (2.5–10.0 μM) alleviated the cytotoxicity caused CA because of OS, as it reduced ROS and LDH levels and increased ΔΨm and GSH. Furthermore, it stimulated the translocation of Nrf2 into the nucleus and downstream HO-1, NQO1, and GCLM gene expressions, as well as reducing the apoptosis rate and recovering the blocked auto-phagic flux induced by CA. Therefore, ScB has a remarkable role in prohibiting CA-provoked OS, autophagy, and apoptosis by promoting cell survival through ROS scavenging [13]. Another study conducted by Zhu et al. in 2012 to assess the effect of ScB on CA produced renal toxicity both in vivo and in vitro. ScB (20 mg/kg/day, gavage followed by CA 30 mg/kg/day, SC for 28 days) significantly repressed the increase in serum creatinine and BUN levels, and improved the kidney structure alteration caused by CA in mice. ScB also reversed the CA negative effects, as indicated by decreasing renal MDA levels and increasing GSH levels. In vitro, Sch B (2.5, 5, and 10 µM) prominently increased HK-2 cell viability and decreased apoptosis and the release of LDH provoked by CA (10 µM), as well as increased ATP and GSH intracellular levels and attenuated ROS generation induced by CA. It is noteworthy that the reduction in OS and cell death rates was proposed to be the reason for ScB’s protective effect [41].

2.3. Carotenoids

LYC (lycopene), a carotenoid, is accountable for the pink-to-red colors of grapefruits, tomatoes, and other foods. It presents a protective influence against various chronic disorders, such as skin, prostate, and lung cancers, as well as degenerative and cardiovascular diseases [59]. LYC is known to have a potent ROS-quenching power and protects DNA, proteins, and lipids against oxidation in vivo [60,61]. It has a protective effect on gentamicin-induced renal damage in rats [62]. Gado et al. conducted a study that revealed the protective effect of LYC (40 mg/kg/day/p.o. for 5 days before and 10 days concomitant with CA) against nephrotoxicity induced by CA. The results show that LYC significantly reduces creatinine and urea serum levels and restores GSH content, as well as prohibits MDA elevation and increases SOD and GSH-Px activities. A histological investigation revealed the amelioration of nephritis and tubular necrosis in comparison with the CA group. LyC alleviated kidney impairment caused by the CA oxidative stress mechanism due to its antioxidant potential [26]. In another investigation, performed in 2007, Ateșșahin et al. evaluated the renal protective action of LYC (10 mg/kg/day for 21 days) in the renal damage and oxidative stress caused by CA in rats, as indicated by the increase in plasma urea and creatinine levels, as well as increased TBARS and GSH and decreased CAT and GSH-Px activities. Moreover, degeneration, tubular necrosis, dilatation, formation of luminal cast, thickened basement membranes, and inter-tubular fibrosis were observed in CA-intoxicated rats. LYC treatment ameliorated the CA reno-toxic effect via decreased plasma urea and creatinine concentrations and elevated TBARs levels while it increased GSH-Px and CAT activity. Moreover, it restored the pathological alteration produced by CA in the kidneys [42].

2.4. Organo-Sulfur Derivatives

S-allylcysteine (SAC), an organo-sulfur constituent of aged Allium sativum, exhibits antioxidant, anti-cancer, neuro-trophic, hepato-, and cardio-protective properties via its antioxidant potential [63]. It was stated that SAC is able to scavenge H2O2 and O2, thus prohibiting H2O2-induced endothelial cell damage, LPO, and LDL low-density lipoprotein oxidation [27]. In 2008, Magendiramani et al. investigated the protective potential of an SAC (100 mg/kg/day, I.P.) co-injection on AC (25 mg/kg/day, I.P.)-induced nephrotoxicity in a rat. The results indicate a marked elevation in uric acid, urea, and creatinine serum levels and LPO together with abnormal antioxidant (non-enzymatic; vit. E and C and GSH, and enzymatic CAT, GPx, SOD, and GR) levels in the CA group in comparison to the control group. Their results reveal that SAC significantly attenuates peroxidative levels and boosts the antioxidant status along with reducing iNOS, MMP-2, and NF-kB elevated levels because of CA. Moreover, it decreases the observed increase in uric acid, urea, and creatinine levels, as well as inflammation and renal injury in CA-treated rats [27].

2.5. Terpenoids

Thymoquinone (TQ), a component of Nigella sativa oil, has anti-hyperglycemic, nephro- and hepato-protective, anti-inflammatory, hypolipidemic, and anti-neoplastic activities. It prohibits CYP3A that is accountable for metabolizing most drugs [64]. Alrashedia et al., in a study performed in 2018, revealed that TQ (orally, 10 mg/kg, 7 days) reduced the bioavailability of oral CA (10 mg/kg, 5 days) and had no effect on the bioavailability of IP-administered CA (10 mg/kg, 5 days, 1 hr after TQ) in rats because of the induction of intestinal first-pass metabolism by TQ, which in turn reduced its blood concentration, resulting in a marked reduction in its nephrotoxicity. On the other hand, TQ significantly attenuated the CA-produced reno-toxic effect, including a reduction in serum creatinine and cystatin C levels and improving kidney tubular and glomerular renal structures [23]. The TQ protective effect may refer to its antioxidant capacity. Hussein et al. also assessed the reno-protective effect of TQ (10 mg/kg b. wt./orally/day for 7 days) against CA (oral dose 25 mg/kg/b.wt./day)-mediated renal toxicity in rats. It was found to normalize increased levels of L-MDA in renal tissues and creatinine and urea in serum as well as the decreased catalase activity and GSH level. Moreover, it markedly upregulated Bcl-2 and downregulated PAI-1, NF-κB, p53, and caspase-3 gene expressions levels. Furthermore, TQ remarkably improved the renal damage and OS alterations via its anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative properties [65].

Oleanolic acid is a triterpene pentacyclic carboxylic acid separated from Olea europaea that possesses hepato-protective, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory potential [24]. It presents a generalized protective effect against chronic cyclosporine nephropathy through Nrf2/HO-1 pathway upregulation resulting in increased levels of NQO-1, HO-1, GSH, SOD, GCL, and S-transferase via affecting the ARE gene, thereby decreasing apoptosis and degradation. This suggests that oleanolic acid could be a potential therapeutic agent for treating A-induced nephrotoxicity involving ARE/Nrf2/HO-1 [24].

2.6. Polysaccharides

Sulfated polysaccharides are a type of metabolite having ester-linked sulfate groups in their backbone. They are commonly reported in seaweeds and have various therapeutic applications [66,67]. They are glycosaminoglycans that can positively counteract glomerular disorders. It has been stated that they possessed an antioxidant potential and have a remarkable mitochondrial influence via their enhanced antioxidant state, decreased accumulation of ROS, improved mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP status, and prohibited release of cytochromes [68,69,70].

Genus Sargassum seaweed is a rich pool for their bioactivities with remarkable biomedical and pharmaceutical uses [71]. Sargassum wightii-sulphated polysaccharides (SWSPs) possess hypolipidemic effects, thus reducing the risk of glomerular dysfunction-associated hyperlipidemia [72].

A study conducted by [69] revealed that SWSPs (5 mg/kg/b.w., SC., for 21 days) possess a protective potential against CA-mediated nephrotoxicity (orally 25 mg/kg/b.w.), as indicated by improved body weight, normalized lysosomal enzymes and creatinine clearance, and attenuated morphological alterations in renal tissues caused by CA in rats [69]. Another study conducted by the same authors demonstrated that SWSPs modulate CA-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and tubular injuries via its powerful antioxidant effect, notably prohibiting mitochondrial oxidative stress through scavenging free radicals, boosting GPx and SOD, and improving the GSH levels. It also suppresses LPO and mitochondrial swelling [68].

3. Herbal Extracts Prevent CA-Induced Nephrotoxicity

Natural products, especially herbal extracts, have a marked role in folk medicine as protecting the kidneys due to their significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Recently, several in vitro and in vivo models were implemented to discover the kidney-protective components of plants [1].

3.1. Zingiber officinale

Zingiber officinale, commonly named ginger, is a perennial plant that belongs to the Zingiberaceae family. The rhizome of the plant has a wide range of medical applications in the treatment of motion sickness, inflammation, and cancer [73]. The activity of ginger rhizomes could be attributed to their polyphenol contents that may be responsible for the antidiabetic, cardio-protective, and hepato-protective activities of the plant [74,75]. In addition, the polyphenol-rich extract (prepared using 80% acetone) could attenuate CA-induced disturbances in kidney function. The prepared extract reversed all alterations produced in the kidneys by CA through a significant improvement in the plasma and urine levels of creatinine, urea, Na+ and K+ electrolyte balance, as well as creatinine clearance. Moreover, it improved feeding patterns, relative kidney weight, and oxidative stress (GSH and SOD). These improvements were also confirmed by a histopathological study [76].

3.2. Phoenix dactylifera

The fruits of Phoenix dactylifera or date palm are widely used as food in many Middle-Eastern countries. Date pits, a byproduct of date palm, were found to be rich in polyphenolic compounds and exert antioxidant, antibacterial, and chemoprotective activities [77]. The protective effect of date pit aqueous extract (DPE) on CA-induced nephrotoxicity was studied. DPE enhanced kidney function after CA administration and increased glutathione levels. A marked decrease in LPO and increase in CAT levels were observed. These results were further confirmed through histopathological investigations of kidney tissues. It was proposed that DPE restored kidney functions in CA-induced nephrotoxicity in rats through antioxidant mechanisms [77].

3.3. Spinacea oleracea

Spinacea oleracea (spinach) is a green, leafy plant used as a food in many countries all over the world. It possesses antioxidant properties, and inhibits lipid peroxidation and hepatoprotective effects in CCl4-induced liver toxicity [78]. N-Hexane extract from spinach leaves was administered with CA for 14 days, and the results of the histopathological investigation of kidney tissues were compared to both CA and spinach-only groups. CA-treated groups presented marked kidney toxicity through vacuolation, necrosis, and loss of brush border in tubular cells. The co-administration of spinach with CA revealed a significant amelioration of all these histopathological lesions, suggesting that spinach hexane extract has a protective effect on CA-induced nephrotoxicity [78].

3.4. Ginseng

Ginseng is widely used in many countries due to its well-known biological activities. The antioxidant activity of ginseng constituents has been discussed and documented in many reports. The protective effect of Korean red ginseng extract (KRG) on CA-induced nephrotoxicity in a mouse model was investigated by measuring renal function, inflammatory mediators, and tubular fibrosis and apoptosis [79]. In addition, the effect of KRG on CA-treated proximal tubular cells (HK-2) was investigated in vitro. 8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OhdG) in urine and tissues was used as a measure of oxidative stress. KRG treatment decreased creatinine levels and proinflammatory mediators, such as NO synthase and cytokines. Induced cellular apoptosis was also decreased by KRG treatment. Moreover, 8-OhdG levels were markedly decreased in urine and tissue samples following KRG administration (Table 3). It was concluded that KRG exerts its nephro-protective effect through antioxidant activity and the prevention of apoptosis [79].

Table 3.

Plants extracts and/or faction effects on CA-induced renal injury.

3.5. Grape and Garlic

Black grapes and garlic are well-known antioxidant foods due to their allicin, alline, and resveratrol contents, respectively. The protective effect of dried black grapes and garlic aqueous extracts on CA-induced nephrotoxicity was investigated in rats by Durak et al. [81]. The grapes and garlic extract were given three days before CA administration for 10 days, and oxidative stress parameters in addition to histopathological investigations were performed. The administration of both plants reduced MDA levels in kidney tissues through the prevention of oxidative stress. Moreover, in a different study, the ingestion of 25 g/kg of dried black grapes with CA by rats significantly decreased MDA levels in the kidney tissues of rats. However, no significant difference was observed in SOD and catalase levels [91]. In the same context, Hussein et al. studied the protective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidin-rich extract (GSPE) on CA-induced nephrotoxicity. GPSE was standardized to contain 66.7 mg/g of total phenolics with an oligomeric proanthocyanidin ratio of 95%. GSPE extracts (200 mg/kg) was administered 7 days before and 21 during CA administration in rats [92]. GSPE treatment decreased serum creatinine, urea, and tissue MDA levels, and reduced glutathione levels. In addition, GSPE treatment retained Bcl-2, NF-κB, caspase-3, and P53 to their normal levels. Thus, grape seed extracts exerted their effect through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and the inhibition of apoptosis. Similar to other studies, GPSE ameliorated impaired kidney function upon co-administration with CA through its antioxidant properties and inhibition of apoptosis. In addition, GPSE did not affect CA plasma levels after administration [93].

Aged garlic extract (AGE) is an odorless material produced by the extraction of garlic for a long period of time (20 months) [93]. AGE was proved to be the most potent antioxidant among all garlic preparations. AGE in 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 g/kg was administered 3 days prior to CA treatment, followed by 10 days of co-administration. AGE in doses of 0.5–2 g/kg decreased renal creatinine and increased creatinine clearance, and ameliorated histopathological changes, such as vacuolation and tubular necrosis [94].

3.6. Green Tea

Tea is the most commonly consumed beverage worldwide, with a known abundance of polyphenol contents. The most abundant compounds in green tea are EGCG and catechin, which are known for their well-reported antioxidant activities. Green tea extract (GTE) with a concentration of 3% W/V was orally administered 21 days before CA and administered for 21 days with CA followed by 21 days alone. GTE was found to alleviate all kidney toxicity parameters, such as increasing GSH and catalase levels and decreasing MDA, creatinine, and urea levels. In addition, it ameliorated the lipid profile and serum glucose, LDH, and GGT levels affected by CA administration [82]. In another study by Mohamadin et al. [83], a 0.5, 1, and 1.5 % W/V solution prepared from instant lyophilized green tea powder was consumed by rats in the experiment 4 days before CA and concurrent with it for 21 days. In addition to the usual enhancement of kidney function and oxidative parameters, GTE inhibited the activity of lysosomal enzymes NAG, β-GU, and AP [83].

3.7. Ipomoea batatas

An aqueous leaf extract of Ipomoea batatas was orally administered in 200 and 400 mg/kg in rats concurrently with CA. It alleviated the CA-induced increase in serum inflammatory cytokines and kidney functions. Moreover, it retained the normal ionic sodium and potassium levels compared to the CA group, in addition to enhancing the impaired histopathological status of kidney tissues by CA [88].

3.8. Schisandra chinensis

In China, patients treated with CA are advised to consume pharmaceutical preparations containing Schisandra chinensis for protection from its side effects [95]. The plant is reported to contain several triterpenoids, such as schisandrol A, schisantherin A, schizandrin A, and schizandrin B. The administration of Schisandara extract (SCE) alleviated hepatorenal injuries induced by CA through the activation of the Nrf2 pathway and the inhibition of apoptosis [90].

3.9. Nigella sativa

Black seed (Nigella sativa) is widely used for culinary and medicinal purposes. Several reports confirmed the protective effects of Nigella sativa extract and its main constituent, thymoquinone, on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity [96,97]. Nigella sativa oil (NSO) in a dose of 2 mL/kg was co-administered with CA to rats, and their kidney function and oxidative stress parameters were investigated. NSO significantly improved renal functions as deduced from lowering serum creatinine and urea levels. In addition, oxidative parameters were markedly improved, such as tissue MDA, CAT, glutathione, and SOD levels. Moreover, the biochemical effects of NSO were confirmed further through the histopathological improvement of kidney tissues. Therefore, NSO ameliorated CA-induced nephrotoxicity through its possible antioxidant effect.

3.10. Cordyceps sinensis

C. sinensis is a plant widely used in Chinese folk medicine as a kidney tonic. The effect of the plant’s administration on the protection of kidneys from the toxic effects of CA in patients with transplantations was studied. The concurrent administration of C. sinensis and CA resulted in significantly reduced nephrotoxicity compared to the CA group of patients, as indicated by decreased serum creatinine, urea, and NAG levels. Moreover, CA plasma levels were the same in both groups [86].

3.11. Doum, Carob, and Fennel

Doum, carob, and fennel are edible plants widely used in Egypt for their culinary and medicinal properties. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) is widely cultivated in the Mediterranean region and used for its aroma and flavor in salad and many dishes, and for its antioxidant, antispasmodic, and antiflatulence properties in folk medicine [98]. Carob (Ceratonia siliqua), which belongs to the Fabaceae family, is widely used in the Mediterranean region as a beverage and food due to its carbohydrate, fiber, and phenolic contents [99]. Doum (Hyphaene thebaica) is a desert palm native to Egypt, Africa, and India. Its fruit pulp is widely used due to its minerals, phenolics, and linoleic acid content [100]. A recent study focused on its possible antihypertensive effects [101]. After the initial injection of rats with CA for 7 days, hey were allowed to consume food containing the three plants. The use of fennel, doum, and carob decreased serum creatinine levels; urinary levels of β2 microglobulin; and serum levels of ammonia, TGF-β1, and TNF-α; and decreased creatinine clearance. Furthermore, a histopathological assessment confirmed the protective effects of these plants through their possible anti-inflammatory effects [87].

4. Miscellaneous Natural Products

4.1. Propolis

Propolis is a bee product rich in a variety of natural constituents, mainly phenolics. Propolis gained popularity as an antioxidant and food additive that is used for treating several diseases. The 60% hydroalcoholic extract of propolis was studied for its nephro-protective effect against CA-induced kidney dysfunction in rats. Propolis extract was administered with CA in a dose of 100 mg/kg orally. It was found that serum cortisol, AST, ALT, and urea levels were markedly decreased upon propolis administration. Moreover, propolis decreased kidney and liver MDA levels, and increased catalase and reduced GSH levels [84].

4.2. Spirulina

Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) is a filamentous blue–green microalgae that acquired its name from its spiral-shaped filaments. It contains carbohydrates, proteins, vitamin B, minerals, and carotenoids, such as beta carotene. It has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and nephro- and radioprotective activities. Spirulina at 1 g/kg was administered 15 days before irradiation or 5 days before and 10 days with CA. Gamma radiation and CA induced a marked elevation in serum creatinine, urea, lipids, and glucose levels, which was reversed by spirulina intake. In addition, spirulina increased kidney SOD and decreased MDA and nitrile levels. Biochemical parameters were confirmed further through histopathological studies. Moreover, kidney caspase-3 levels in the CA-treated group were significantly decreased by using spirulina [85].

5. Diet Prevents CA-Induced Nephrotoxicity

Less research has been conducted to assess the effect of dietary regimen on CA-induced reno-toxicity. We presented the results of these studies in the present paper.

Fish oil-derived omega-3 fatty acids have a protective potential against various metabolic disorders and diseases, such as MetS, cancer, neuro-degenerative and autoimmune disorders, diabetes, and CVD [102]. They play a significant role in anti-inflammatory processes and improve the antioxidant defense system [103]. Priyamvada et al. reported that dietary fish oil (DFO) alleviated gentamicin-produced oxidative damage and metabolic alterations because of its intrinsic antioxidant/biochemical properties [104,105]. In 2014, Hussein et al. demonstrated that CA remarkably increased the renal function tests, serum glucose, lipid profiles, haptoglobin, and serum (GGT and LDH) enzymes with a considerable lowering of serum albumin, electrolytes, and total protein. Co-treatment with DFO and CA remarkably reduced these parameters as compared with the CA-received group. Moreover, CA induced a considerable increase in MDA, along with a noticeable reduction in enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, TOC, and NO levels in the rat kidneys. Meanwhile, DFO improved renal function through a significant increase in the antioxidant status and decrease in peroxidative levels. These results reveal the usefulness and reno-protective capacity of DFO as a rich source of antioxidants in modulating CA-induced nephrotoxicity [40]. Moreover, it was reported that the antioxidant nutrients, such as vitamins C and E, ameliorate the toxic effects produced CA in kidneys, whereas vitamin E prohibits ROS and TX synthesis as well as lipid peroxidation caused by CA. Furthermore, they can improve renal function and CA-produced histological damage [106]. A study by Klawitter et al. in 2012 demonstrated that low-salt-diet-fed rats are more sensitive to CA (10 mg/kg/day CA for 28 days on low-salt diet) renal injuries than normal-salt-diet-fed rats (10 mg/kg/day CA for 28 days on low-salt diet). Their results show that micro- and macro-vesicular tubular epithelial vacuolizations and a reduced energy charge are more prominent in low-salt-fed rats. CA increased phospho-JAK2 and -STAT3 levels and reduced p65 and phospho-IKKγ proteins, leading to NF-κB signaling activation. Moreover, reduced lactate transport regulator CD147 and phospho-AKT expression were noted after the exposure of low-salt-fed rats to CA, revealing a decrease in glycolysis. Collectively, AKT, CD147, and JAK/STAT signaling displayed a remarkable role in CA reno-toxicity [107].

A protein-rich diet’s potential for several drugs producing renal toxicity was investigated. Protein feeding was reported to increase GFR and RPF levels in rats [108]. Therefore, it may counteract the vasoconstriction produced by CA and reduce its nephrotoxicity. A study performed by Pons et al. in 2003 demonstrated the protective effect of a casein-rich diet against in proximal tubule damage induced by CA. In CA (25 mg/kg/24h, I.P. for 7 days)-challenge rats, there were no significant differences in caloric consumption, bodyweight, urine output, and water intake among standard Rat Chow and high-protein fed (casein-rich diet for 2 weeks before CA) animals. However, β-GAL and NAG urine excretion and renal post-necrotic cellular regeneration were remarkably lower for the high-protein diet CA-treated rats than in those fed with standard Rat Chow, and no gold particle was observed over proximal tubule lysosomes in rich-protein-diet-fed rats [109]. Venkateswarlu et al. evaluated the LOBUN probiotic formulation’s (500 mg/kg/b.w. for twice or thrice a day from the 15th to 28th day) nephro-protective effect on CA (20 mg/kg SC, 15 days)-induced renal impairment in Wistar rats. In this study, CA-induced renal toxicity was indicated by increased BUN, serum creatinine, uric acid, and total protein levels, as well as urine potassium, proteins, and sodium. LOBUN (500 mg/kg b.w. thrice a day) provided appreciable reno-protection and alleviated the CKD symptoms against CA that was evidenced by biochemical and histological findings [80].

Olive oil is regarded as a superfood with numerous health benefits that are attributed to its unique contents, including high percent of MUFA (monounsaturated fatty acids) as well as other bioactive constituents. Its phenolics are reputed to have the potential as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobials, and antioxidants [110]. Elshama et al. investigated the protective potential of VOO (virgin olive oil, 1.25 mL/kg/day, GL) or naringenin (100 mg/kg/day, GL) co-administration on CA (25 mg/kg/day, GL)-induced renal damage in rats. The results reveal that VOO modulates CA-induced ultra-structure and morphologic changes, improves antioxidant status, and decreases urea and creatinine levels to the same extent as naringenin [28].

6. Natural Products’ Stability and Adverse Effects

The stability of herbal products as extracts or purified compounds represents an important issue in using natural products to combat ailments. The stability of herbal products includes its ability to preserve its identity, strength, and purity. However, during the process of extraction and preparation of natural products, the active constituents are subjected to oxidation, hydrolysis, microbial attack, and other environmental deterioration effects, which affect its stability [111]. The quality, effectiveness, and shelf life of natural medicines are all impacted by the presence and concentration of bioactive ingredients; therefore, monitoring their presence and concentration is crucial. The factors that may affect the stability of herbal products include: its presence in a complex mixture of different components, drug interaction, or decomposition during storage; physical and chemical stability; and finally the environmental factors. Different techniques could be used to overcome the instability of natural preparations, including nanoparticle coating to enhance shelf life, semisolid preparations based on supercritical carbon dioxide, liquid preparation coated with water-soluble cellulose, derivatives using polymeric plant-derived excipients in drug delivery, micro-encapsulation for active constituents, and adding antioxidants to prevent the oxidation of active compounds. A detailed discussion of the different methods for increasing stability have been previously published [111].

Many people think that pharmaceutical agents are too expensive and have unwanted side-effects; on the other hand, they believe that medicinal herbs must be efficient and safe. However, this prevalent faith that herbs are safe is shown to be faulty. Unfortunately, the contamination by mycotoxins, microbes, pesticides, and even heavy metals, such as arsenic, lead, or mercury, has been reported, especially among Internet-sold herbs [112]. Indeed, several studies reported the hepato-toxic potential of natural products. For example, black cohosh mediated liver injury through mitochondrial damage. EGCG (epigallocatechin gallate), the main phenolic in green tea, was reported to be the most potentially hepatotoxic constituent; in addition, green tea extract’s high doses may cause acute intensive liver injury. Additionally, several potentially dangerous interactions between herbs and drugs have been described [113]. Kava, valerian, St. John’s wort, and ginkgo, which are used for supporting mental health, interact with commonly utilized medications, e.g., the use of St. John’s wort with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors could result in serotonin syndrome [114]. The CA’s bioavailability was found to be affected by many herbal extracts and traditional drugs that influence CA’s blood concentration. In a case report, St John’s wort and in vivo animal studies, liquorice, ginger, quercetin, and scutellariae radix were shown to decrease CA blood concentration. However, an increased CA concentration was noted with berberine, resveratrol, grapefruit juice, chamomile, or cannabidiol in animal studies [9]. On the other hand, it was stated that the concomitant use of Serenoa repens and Echinacea with CA should be avoided. Thus, the knowledge of a patient’s usage of natural products before CA administration is crucial to overcome the possible interactions between CA and herbal preparations.

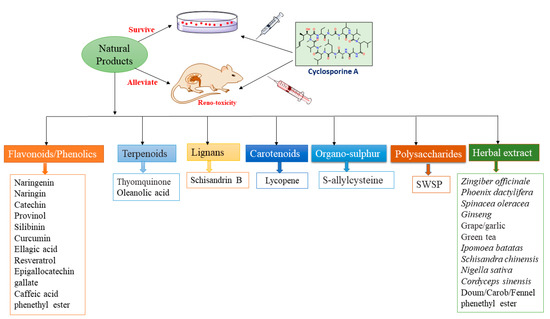

7. Conclusions

Kidneys have an essential role in maintaining homeostasis. Kidney illnesses are serious health concerns that cause an economic burden and worrisome morbidity. They can occur following certain medications’ usage, such as CA that mediates its destructive effect through various cascades. Unfortunately, the pathogenesis of CA-induced reno-toxicity is complicated; its earlier diagnosis is difficult and effective treatment options are lacking. This has encouraged researchers to search for natural metabolites with fewer side effects. It was observed that several natural biomolecules have been reported to reduce or mitigate the severity of CA-induced renal toxicity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Different classes of natural products protect against CA-induced nephrotoxicity.

These metabolites appear to have a crucial role in protecting and detoxifying renal tissues against CA-induced damage through their anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative properties. The presented data in this work provided a scientific bases for the rational utilization development and discovery of phytoconstituents for treating practices. In this literature survey, it was observed that the reno-protection of the most-studied plants or their phytoconstituents was explained as related to oxidative stress. Meanwhile, there are other mechanisms of reno-protection that may be responsible for the protective effect on the kidneys, which need further study. Additionally, some studies revealed that dietary regimen has a marked effect on CA-induced reno-toxicity. Most of the reported studies were conducted on animal models. Understanding how natural products act through various signaling pathways will produce a better insight into the potential prevention and treatment of CA-induced renal toxicity. However, further clinical studies are warranted to amend the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic understanding of these metabolites. Additionally, a further evaluation of other classes of natural metabolites reported by various sources is required.

List of abbreviations: 2-DG: 2-Deoxy-D-glucose; 8-iso-PGF2α: 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; AP: acid phosphatase; 8-OHdG: 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; AREs: antioxidant-response elements; b.w.: body weight; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; CA: cyclosporine A; CAT: catalase; c-GT; c-Glutamyl transferase; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CMC: carboxy methyl cellulose; Cr: creatinine; CYP3A: cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily A; EGCG: epigallocatechin gallate; EMT: epithelial–mesenchymal transition; GCLM: glutamate-cysteine ligase-modifier subunit; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; GGT: gamma glutamyl transferase; GL: gastric lavage; GSH-Px: glutathione peroxidase; GR: glutathione reductase; GSH: reduced glutathione; GST: glutathione-S-transferase; HK-2: human proximal tubular epithelial cell line; HO-1: heme oxygenase-1; HSP-70: heat shock protein-70; I.P.: intra-peritoneal; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; c-GT: c-Glutamyl transferase; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LPO: lipid peroxidation; MMP-2: matrix metalloproteinase-2; MetS: metabolic syndrome; MUFAs: monounsaturated fatty acids; NAG: N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase; NF-kB: nuclear factor kappa B; NO: nitric oxide; NPs: nanoparticles; NQO1 NAD(P) H: quinone oxidoreductase 1; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; OHdG: 8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; OS: oxidative stress; p.o.: perorally; PC: plasma creatinine; PLs: phospholipids; PLGA: poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; Px: peroxidase; ROS: reactive oxygen species; RPF: renal plasma flow; SC: subcutaneously; SBP: systolic blood pressure; ScB: Schisandrin B; SWSPs: Sargassum wightii-sulphated polysaccharides; TAO: total antioxidant capacity; TBARS: thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances; TC: total cholesterol; TAGs: triacylglycerols; TP: total protein; TX: thromboxane; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; TQ: thymoquinone; UA: uric acid; VOO: virgin olive oil; XO: xanthine oxidase; β2MG: β2-microglobulin; β-GAL: β-galactosidase; ΔΨm: mitochondrial transmembrane potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.M.I., H.M.A., A.M.E.-H., G.A.M. and R.S.E.-D.; methodology, S.R.M.I., H.M.A., A.M.E.-H., G.A.M. and R.S.E.-D.; software, A.A.A. (Ali A. Alqarni), W.A.S., A.A.A. (Aisha A. Alhaddad), A.T.R., K.F.G. and R.S.E.-D.; resources, A.A.A. (Ali A. Alqarni), W.A.S., A.A.A. (Aisha A. Alhaddad), A.T.R., R.S.E.-D. and K.F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.M.I., H.M.A., A.M.E.-H., G.A.M. and R.S.E.-D.; writing—review and editing, S.R.M.I., H.M.A., A.M.E.-H., G.A.M., A.A.A. (Ali A. Alqarni), W.A.S., A.A.A. (Aisha A. Alhaddad), A.T.R. and R.S.E.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

2-DG: 2-Deoxy-D-glucose; 8-iso-PGF2α: 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; AP: acid phosphatase; 8-OHdG: 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; AREs: antioxidant-response elements; b.w.: body weight; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; CA: cyclosporine A; CAT: catalase; c-GT; c-Glutamyl transferase; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CMC: carboxy methyl cellulose; Cr: creatinine; CYP3A: cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily A; EGCG: epigallocatechin gallate; EMT: epithelial–mesenchymal transition; GCLM: glutamate-cysteine ligase-modifier subunit; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; GGT: gamma glutamyl transferase; GL: gastric lavage; GSH-Px: glutathione peroxidase; GR: glutathione reductase; GSH: reduced glutathione; GST: glutathione-S-transferase; HK-2: human proximal tubular epithelial cell line; HO-1: heme oxygenase-1; HSP-70: heat shock protein-70; I.P.: intra-peritoneal; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; c-GT: c-Glutamyl transferase; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LPO: lipid peroxidation; MMP-2: matrix metalloproteinase-2; MetS: metabolic syndrome; MUFAs: monounsaturated fatty acids; NAG: N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase; NF-kB: nuclear factor kappa B; NO: nitric oxide; NPs: nanoparticles; NQO1 NAD(P) H: quinone oxidoreductase 1; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; OHdG: 8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; OS: oxidative stress; p.o.: perorally; PC: plasma creatinine; PLs: phospholipids; PLGA: poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; Px: peroxidase; ROS: reactive oxygen species; RPF: renal plasma flow; SC: subcutaneously; SBP: systolic blood pressure; ScB: Schisandrin B; SWSPs: Sargassum wightii-sulphated polysaccharides; TAO: total antioxidant capacity; TBARS: thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances; TC: total cholesterol; TAGs: triacylglycerols; TP: total protein; TX: thromboxane; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; TQ: thymoquinone; UA: uric acid; VOO: virgin olive oil; XO: xanthine oxidase; β2MG: β2-microglobulin; β-GAL: β-galactosidase; ΔΨm: mitochondrial transmembrane potential.

References

- Jivishov, E.; Nahar, L.; Sarker, S.D. Nephroprotective natural products. In Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 55, pp. 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Touiti, N.; Houssaini, T.S.; Achour, S. Overview on pharmacovigilance of nephrotoxic herbal medicines used worldwide. Clin. Phytoscience 2021, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolangi, F.; Memariani, Z.; Bozorgi, M.; Mozaffarpur, S.A.; Mirzapour, M. Herbs with potential nephrotoxic effects according to the traditional Persian medicine: Review and assessment of scientific evidence. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huang, J. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity: Pathogenic mechanisms, biomarkers and prevention strategies. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.; Ahmed, S.; Gerritsen, K.G.; Mihaila, S.M.; Masereeuw, R. Kidney-based in vitro models for drug-induced toxicity testing. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 3397–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Moon, A. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity and its biomarkers. Biomol. Ther. 2012, 20, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafavi-Pour, Z.; Khademi, F.; Zal, F.; Sardarian, A.R.; Amini, F. In vitro analysis of CsA-induced hepatotoxicity in HepG2 cell line: Oxidative stress and α2 and β1 integrin subunits expression. Hepat. Mon. 2013, 13, e11447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciresi, D.L.; Lloyd, M.A.; Sandberg, S.M.; Heublein, D.M.; Edwards, B.S. The sodium retaining effects of cyclosporine. Kidney Int. 1992, 41, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, D.; Lunardon, L.; Bellia, G. Cyclosporine and herbal supplement interactions. J. Toxicol. 2014, 2014, 145325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.D.; Perego, R.; Bellia, G. Drug interaction and potential side effects of cyclosporine. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 74, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Nepovimova, E.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Kuca, K. Mechanism of cyclosporine A nephrotoxicity: Oxidative stress, autophagy, and signalings. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, D.; Haragsim, L. Cyclosporine: A Review. J. Transplant. 2012, 2012, 230386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Q.; Luo, Z.; Wu, C.; Lai, S.; Wei, H.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Y. Attenuation of cyclosporine A induced nephrotoxicity by schisandrin B through suppression of oxidative stress, apoptosis and autophagy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 52, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiano, S.; Ciarcia, R.; Montagnaro, S.; Pagnini, U.; Garofano, T.; Capasso, G.; Florio, S.; Giordano, A. Prevention of nephrotoxicity induced by cyclosporine-A: Role of antioxidants. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciarcia, R.; Damiano, S.; Florio, A.; Spagnuolo, M.; Zacchia, E.; Squillacioti, C.; Mirabella, N.; Florio, S.; Pagnini, U.; Garofano, T. The protective effect of apocynin on cyclosporine A-induced hypertension and nephrotoxicity in rats. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamon, J.; Jennings, P.; Bois, F.Y. Systems biology modeling of omics data: Effect of cyclosporine a on the Nrf2 pathway in human renal cells. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.-f.; Ye, J.-m.; Yu, L.-x.; Dong, X.-h.; Feng, J.-h.; Xiong, Y.; Gu, X.-x.; Li, S.-s. Klotho mitigates cyclosporine A (CsA)-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and renal fibrosis in rats. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorrow, T.; Gaffney, M.M.; Slattery, C.; Campbell, E.; Ryan, M.P. Cyclosporine A induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2005, 20, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Choi, S.-I.; Jeung, E.-B.; Yoo, Y.-M. Cyclosporine A induces apoptotic and autophagic cell death in rat pituitary GH3 cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.-H.; Zheng, S.-S.; Jia, C.-K.; Zhu, Y.-F.; Xie, H.-Y. Inhibitory effect of tea polyphenols on transforming growth factor-beta1 expression in rat with cyclosporine A-induced chronic nephrotoxicity. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2004, 25, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wirestam, L.; Frodlund, M.; Enocsson, H.; Skogh, T.; Wetterö, J.; Sjöwall, C. Osteopontin is associated with disease severity and antiphospholipid syndrome in well characterised Swedish cases of SLE. Lupus Sci. Med. 2017, 4, e000225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaneyulu, M.; Tirkey, N.; Chopra, K. Attenuation of cyclosporine-induced renal dysfunction by catechin: Possible antioxidant mechanism. Ren. Fail. 2003, 25, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrashedi, M.G.; Ali, A.S.; Ali, S.S.; Khan, L.M. Impact of thymoquinone on cyclosporine A pharmacokinetics and toxicity in rodents. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 70, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.A.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, E.N.; Koh, E.S.; Shin, S.J.; Choi, B.S.; Park, C.W.; Chang, Y.S.; Chung, S. Delayed treatment with oleanolic acid attenuates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in chronic cyclosporine nephropathy through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Wei, J.; Mahmoodurrahman, M.; Zhang, C.; Quan, S.; Li, T.; Yu, Y. Pharmacokinetic and nephroprotective benefits of using Schisandra chinensis extracts in a cyclosporine A-based immune-suppressive regime. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 4997–5018. [Google Scholar]

- Gado, A.M.; Adam, A.N.I.; Aldahmash, B.A. Protective effect of lycopene against nephrotoxicity induced by cyclosporine in rats. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10, 1850–1856. [Google Scholar]

- Magendiramani, V.; Umesalma, S.; Kalayarasan, S.; Nagendraprabhu, P.; Arunkumar, J.; Sudhandiran, G. S-allylcysteine attenuates renal injury by altering the expressions of iNOS and matrix metallo proteinase-2 during cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in Wistar rats. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009, 29, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said Elshama, S.; Osman, H.-E.H.; El-Kenawy, A.E.-M. Renoprotective effects of naringenin and olive oil against cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Iranian J. Toxicol. 2016, 10, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramohan, Y.; Parameswari, C.S. Therapeutic efficacy of naringin on cyclosporine (A) induced nephrotoxicity in rats: Involvement of hemeoxygenase-1. Pharmacol. Rep. 2013, 65, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.-Y.; Sang, L.-X.; Jiang, M. Catechins and their therapeutic benefits to inflammatory bowel disease. Molecules 2017, 22, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatroodi, S.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Khan, A.A.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Potential therapeutic targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), the most abundant catechin in green tea, and its role in the therapy of various types of cancer. Molecules 2020, 25, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.-L.; Tay, V.; Guo, S.-Z.; Ren, J.; Shu, M.-G. Silibinin induced human glioblastoma cell apoptosis concomitant with autophagy through simultaneous inhibition of mTOR and YAP. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 6165192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattah, E.A.; Hashem, H.E.; Ahmed, F.A.; Ghallab, M.A.; Varga, I.; Polak, S. Prophylactic role of curcumin against cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity: Histological and immunohistological study. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2010, 29, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- BenSaad, L.A.; Kim, K.H.; Quah, C.C.; Kim, W.R.; Shahimi, M. Anti-inflammatory potential of ellagic acid, gallic acid and punicalagin A&B isolated from Punica granatum. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Hamid, M.; Abdella, E.M.; Galaly, S.R.; Ahmed, R.H. Protective effect of ellagic acid against cyclosporine A-induced histopathological, ultrastructural changes, oxidative stress, and cytogenotoxicity in albino rats. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2016, 40, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gökçe, A.; Oktar, S.; Yönden, Z.; Aydın, M.; İlhan, S.; Özkan, O.V.; Davarcı, M.; Yalçınkaya, F.R. Protective effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Ren. Fail. 2009, 31, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, V.; Tirkey, N.; Chopra, K. Resveratrol, a polyphenolic phytoalexin protects against cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity through nitric oxide dependent mechanism. Toxicology 2005, 210, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italia, J.; Datta, P.; Ankola, D.; Kumar, M. Nanoparticles enhance per oral bioavailability of poorly available molecules: Epigallocatechin gallate nanoparticles ameliorates cyclosporine induced nephrotoxicity in rats at three times lower dose than oral solution. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2008, 4, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, K. Effect of epigallocatechin gallate on renal function in cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity. Transplant. Proc. 2004, 36, 2133–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.A.; Ragab, O.A.; El-Eshmawy, M.A. Renoprotective effect of dietary fish oil on cyclosporine A: Induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Asian J. Biochem. 2014, 9, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Jin, J.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, M.; Huang, Z. Protective effect of schisandrin B against cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2012, 40, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateşşahin, A.; Çeribaşı, A.O.; Yılmaz, S. Lycopene, a carotenoid, attenuates cyclosporine-induced renal dysfunction and oxidative stress in rats. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 100, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiman, A.-Q.; Nesrin, M.; Amal, A.; Said, A.-D. The possible Ameliorating and Antioxidant Effects of Curcumin against Cyclosporine-Induced renal Impairment in Rats Kidney. Bull. Environ. Pharmacol. Life Sci. 2020, 9, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Yao, X.; Weng, G.; Qi, H.; Ye, X. Protective effect of curcumin against cyclosporine A-induced rat nephrotoxicity. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 6038–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkey, N.; Pilkhwal, S.; Kuhad, A.; Chopra, K. Hesperidin, a citrus bioflavonoid, decreases the oxidative stress produced by carbon tetrachloride in rat liver and kidney. BMC Pharmacol. 2005, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yüce, A.; Ateşşahin, A.; Çeribaşı, A.O. Amelioration of cyclosporine A-induced renal, hepatic and cardiac damages by ellagic acid in rats. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008, 103, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zima, T.; Kamenikova, L.; Janebova, M.; Buchar, E.; Crkovska, J.; Tesar, V. The effect of silibinin on experimental cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Ren. Fail. 1998, 20, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffoli, B.; Pechánová, O.; Kojšová, S.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Giugno, L.; Bianchi, R.; Rezzani, R. Provinol prevents CsA-induced nephrotoxicity by reducing reactive oxygen species, iNOS, and NF-kB expression. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2005, 53, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzani, R.; Rodella, L.F.; Tengattini, S.; Bonomini, F.; Pechanova, O.; Kojšová, S.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Bianchi, R. Protective role of polyphenols in cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxicity during rat pregnancy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2006, 54, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzani, R.; Tengattini, S.; Bonomini, F.; Filippini, F.; Pechánová, O.; Bianchi, R.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Red wine polyphenols prevent cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity at the level of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Physiol. Res. 2009, 58, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Mukhtar, H. Cancer chemoprevention through dietary antioxidants: Progress and promise. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 475–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingul, I.; Olgac, V.; Bekpinar, S.; Uysal, M. The protective effect of resveratrol against cyclosporine A-induced oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 127, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Seo, Y.-S.; Lim, D.-Y. Provinol inhibits catecholamine secretion from the rat adrenal medulla. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009, 13, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechanova, O.; Rezzani, R.; Babál, P.; Bernatova, I.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Beneficial effects of Provinols: Cardiovascular system and kidney. Physiol. Res. 2006, 55, S17–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.J.; Prasanth Kumar, S.; Rao, M.V.; Pandya, H.A. Ameliorative effects of curcumin towards cyclosporine-induced genotoxic potential: An in vitro and in silico study. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 41, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunel, V.; Antoine, M.H.; Nortier, J.; Duez, P.; Stévigny, C. Protective effects of schizandrin and schizandrin B towards cisplatin nephrotoxicity in vitro. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 34, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacchiotti, A.; Volti, G.L.; Lavazza, A.; Schena, I.; Aleo, M.F.; Rodella, L.F.; Rezzani, R. Different role of Schisandrin B on mercury-induced renal damage in vivo and in vitro. Toxicology 2011, 286, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, P.Y.; Leung, H.Y.; Ko, K.M. Schisandrin B enhances renal mitochondrial antioxidant status, functional and structural integrity, and protects against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.G.; Souza, J.M.; Santos, R.C.; Gullon, B.; Oliveira, A.; Santos, L.F.; Virgino, A.L.; Mafud, A.C.; Petrilli, H.M.; Mascarenhas, Y.P. HPLC-DAD, ESI–MS/MS, and NMR of Lycopene Isolated From P. guajava L. and Its Biotechnological Applications. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2018, 120, 1700330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapiero, H.; Townsend, D.M.; Tew, K.D. The role of carotenoids in the prevention of human pathologies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2004, 58, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, H.R.; Di Mascio, P.; Medeiros, M.H. Protective effect of lycopene on lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage in cell culture. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 383, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, İ.; Ateşşahin, A.; Yılmaz, S.; Çeribaşı, A.; Sakin, F. Protective effect of lycopene on gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity in rats. Toxicology 2005, 215, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avula, P.R.; Asdaq, S.M.; Asad, M. Effect of aged garlic extract and s-allyl cysteine and their interaction with atenolol during isoproterenol induced myocardial toxicity in rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2014, 46, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farag, M.M.; Ahmed, G.O.; Shehata, R.R.; Kazem, A.H. Thymoquinone improves the kidney and liver changes induced by chronic cyclosporine A treatment and acute renal ischaemia/reperfusion in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, S.A.; Elsenosi, Y.; Esmael, T.E.A.; Amin, A.; Sarhan, E.A.M. Thymoquinone suppressed Cyclosporine A-induced Nephrotoxicity in rats via antioxidant activation and inhibition of inflammatory and apoptotic signaling pathway. Benha Vet. Med. J. 2020, 39, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zaporozhets, T.; Besednova, N. Prospects for the therapeutic application of sulfated polysaccharides of brown algae in diseases of the cardiovascular system. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 3126–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. Therapeutic importance of sulfated polysaccharides from seaweeds: Updating the recent findings. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephine, A.; Amudha, G.; Veena, C.K.; Preetha, S.P.; Rajeswari, A.; Varalakshmi, P. Beneficial effects of sulfated polysaccharides from Sargassum wightii against mitochondrial alterations induced by Cyclosporine A in rat kidney. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephine, A.; Veena, C.K.; Amudha, G.; Preetha, S.P.; Sundarapandian, R.; Varalakshmi, P. Sulphated Polysaccharides: New Insight in the Prevention of Cyclosporine A-Induced Glomerular Injury. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 101, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, B.; Li, J.; Fu, X.; Gan, L.; Xin, X.; Geng, M. Sulfated polymannuroguluronate, a novel anti-AIDS drug candidate, inhibits T cell apoptosis by combating oxidative damage of mitochondria. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 1716–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneesh, A.; Chakraborty, K.; Makkar, F. Pharmacological activities of brown seaweed Sargassum wightii (Family Sargassaceae) using different in vitro models. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephine, A.; Veena, C.K.; Amudha, G.; Preetha, S.P.; Varalakshmi, P. Protective role of sulphated polysaccharides in abating the hyperlipidemic nephropathy provoked by cyclosporine A. Arch. Toxicol. 2007, 81, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, E.; Pittler, M. Efficacy of ginger for nausea and vomiting: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000, 84, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazeem, M.I.; Akanji, M.A.; Yakubu, M.T.; Ashafa, A.O.T. Protective effect of free and bound polyphenol extracts from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) on the hepatic antioxidant and some carbohydrate metabolizing enzymes of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 935486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laight, D.; Carrier, M.; Änggård, E. Antioxidants, diabetes and endothelial dysfunction. CardiovaSC Res. 2000, 47, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, I.A.; Imafidon, C.E.; Oladele, A.A.; Ayoka, A.O. Ginger polyphenols attenuate cyclosporine-induced disturbances in kidney function: Potential application in adjuvant transplant therapy. Pathophysiology 2018, 25, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljawad, E.A. Potential Antioxidant Effect of Date Pits Extract on Nephrotoxicity induced by Cyclosporine-A in Male Rats. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharmacol. Res. 2019, 9, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lone, K.P. Protective Effect of Sponacea Oleracea Extract on cyclosporine-A induced nephrotoxixicty in male albino rats. Biomedica 2016, 32, 935486. [Google Scholar]

- Doh, K.C.; Lim, S.W.; Piao, S.G.; Jin, L.; Heo, S.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Bae, S.K.; Hwang, G.H.; Min, K.I.; Chung, B.H. Ginseng treatment attenuates chronic cyclosporine nephropathy via reducing oxidative stress in an experimental mouse model. Am. J. Nephrol. 2013, 37, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswarlu, K.; Heerasingh, T.; Babu, C.N.; Triveni, S.; Manasa, S.; Babu, T.N.B. Preclinical evaluation of nephroprotective potential of a probiotic formulation LOBUN on Cyclosporine-A induced renal dysfunction in Wistar rats. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 53, e16042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, I.; Çetin, R.; Çandır, Ö.; Devrim, E.; Kılıçoğlu, B.; Avcı, A. Black grape and garlic extracts protect against cyclosporine a nephrotoxicity. Immunol. Investig. 2007, 36, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.A.; Ragab, O.A.; El-Eshmawy, M.A. Protective effect of green tea extract on cyclosporine A: Induced nephrotoxicity in rats. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 14, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadin, A.; El-Beshbishy, H.; El-Mahdy, M. Green tea extract attenuates cyclosporine A-induced oxidative stress in rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2005, 51, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seven, I.; Baykalir, B.G.; Seven, P.T.; Dağoğlu, G. The ameliorative effects of propolis against cyclosporine A induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in rats. System 2014, 10, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.M.; Eid, N.I.; Nada, A.S.; Amin, N.E.-D.; Ain-Shoka, A.A. Possible protective effect of the algae spirulina against nephrotoxicity induced by cyclosporine A and/or gamma radiation in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 9060–9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Huang, J.; Jiang, L.; Xu, J.; Mi, J. Amelioration of cyclosporin nephrotoxicity by Cordyceps sinensis in kidney-transplanted recipients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1995, 10, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shalby, A.; Hamza, A.; Ahmed, H. New insight on the anti-inflammatory effect of some Egyptian plants against renal dysfunction induced by cyclosporine. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 16, 455–461. [Google Scholar]

- Shatwan, I.M. Renoprotective Effect Of Ipomoea Batatas Aqueous Leaf Extract On Cyclosporine-Induced Renal Toxicity In Male Rats. Pharmacophores 2019, 10, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Uz, E.; Bayrak, O.; Uz, E.; Kaya, A.; Bayrak, R.; Uz, B.; Turgut, F.H.; Bavbek, N.; Kanbay, M.; Akcay, A. Nigella sativa oil for prevention of chronic cyclosporine nephrotoxicity: An experimental model. Am. J. Nephrol. 2008, 28, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, K.; Wu, Q.; Xiao, W.; Yu, Y.; Li, T. Schisandrae chinensis fructus extract protects against hepatorenal toxicity and changes metabolic ions in cyclosporine A rats. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 35, 2915–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergüder, İ.B.; Çetin, R.; Devrim, E.; Kılıçoğlu, B.; Avcı, A.; Durak, İ. Effects of cyclosporine on oxidant/antioxidant status in rat ovary tissues: Protective role of black grape extract. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2005, 5, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.A.; Elsenosi, Y.; Esmael, T.E.A.; Amin, A.; Sarhan, E.A.M. Evaluation of renoprotective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on Cyclosporine A-induced Nephrotoxicity by mitigating inflammatory response, oxidative stress and apoptosis in rats. Benha Vet. Med. J. 2020, 39, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, S.; Ozkan, G.; Yucesan, F.B.; Ersöz, Ş.; Orem, A.; Alkanat, M.; Yuluğ, E.; Kaynar, K.; Al, S. Anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidant effects of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract in preventing cyclosporine A-induced nephropathy. Nephrology 2012, 17, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongmekiat, O.; Thamprasert, K. Investigating the protective effects of aged garlic extract on cyclosporin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 19, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Gao, S.; Liu, J.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, B.; Liu, M.; Sun, X.; Guo, P. Extracts and lignans of Schisandra chinensis fruit alter lipid and glucose metabolism in vivo and in vitro. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Daly, E.S. Protective effect of cysteine and vitamin E, Crocus sativus and Nigella sativa extracts on cisplatin-induced toxicity in rats. J. Pharm. Belg. 1998, 53, 87–93, discussion 93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Badary, O.A.; Nagi, M.N.; Al-Shabanah, O.A.; Al-Sawaf, H.A.; Al-Sohaibani, M.O.; Al-Bekairi, A.M. Thymoquinone ameliorates the nephrotoxicity induced by cisplatin in rodents and potentiates its antitumor activity. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997, 75, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckensturm, B.; Foechterlen, D.; Reduron, J.-P.; Danton, P.; Hildenbrand, M. Phytochemical and chemotaxonomic studies of Foeniculum vulgare. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1997, 25, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Haubner, R.; Hull, W.; Erben, G.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Bartsch, H.; Haber, B. Isolation and structure elucidation of the major individual polyphenols in carob fibre. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.A.; VanderJagt, D.J.; Pastuszyn, A.; Mounkaila, G.; Glew, R.S.; Millson, M.; Glew, R.H. Nutrient and chemical composition of 13 wild plant foods of Niger. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 13, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, B.; Coupar, I.M.; Ng, K. Antioxidant activity of hot water extract from the fruit of the Doum palm, Hyphaene thebaica. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: From molecules to man. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, L.; Medina, I. Polyphenols and fish oils for improving metabolic health: A revision of the recent evidence for their combined nutraceutical effects. Molecules 2021, 26, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyamvada, S.; Priyadarshini, M.; Arivarasu, N.; Farooq, N.; Khan, S.; Khan, S.A.; Khan, M.W.; Yusufi, A. Studies on the protective effect of dietary fish oil on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative damage in rat kidney. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2008, 78, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, B.; Bashir, A. Effect of fish oil treatment on gentamicin nephrotoxicity in rats. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 1994, 38, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, T.P.; Garcıa, J.C.; Alvarez, F.C.; De Arriba, G. Antioxidant nutrients protect against cyclosporine A nephrotoxicity. Toxicology 2003, 189, 99–111. [Google Scholar]