Microbial Proteins in Stomach Biopsies Associated with Gastritis, Ulcer, and Gastric Cancer

Abstract

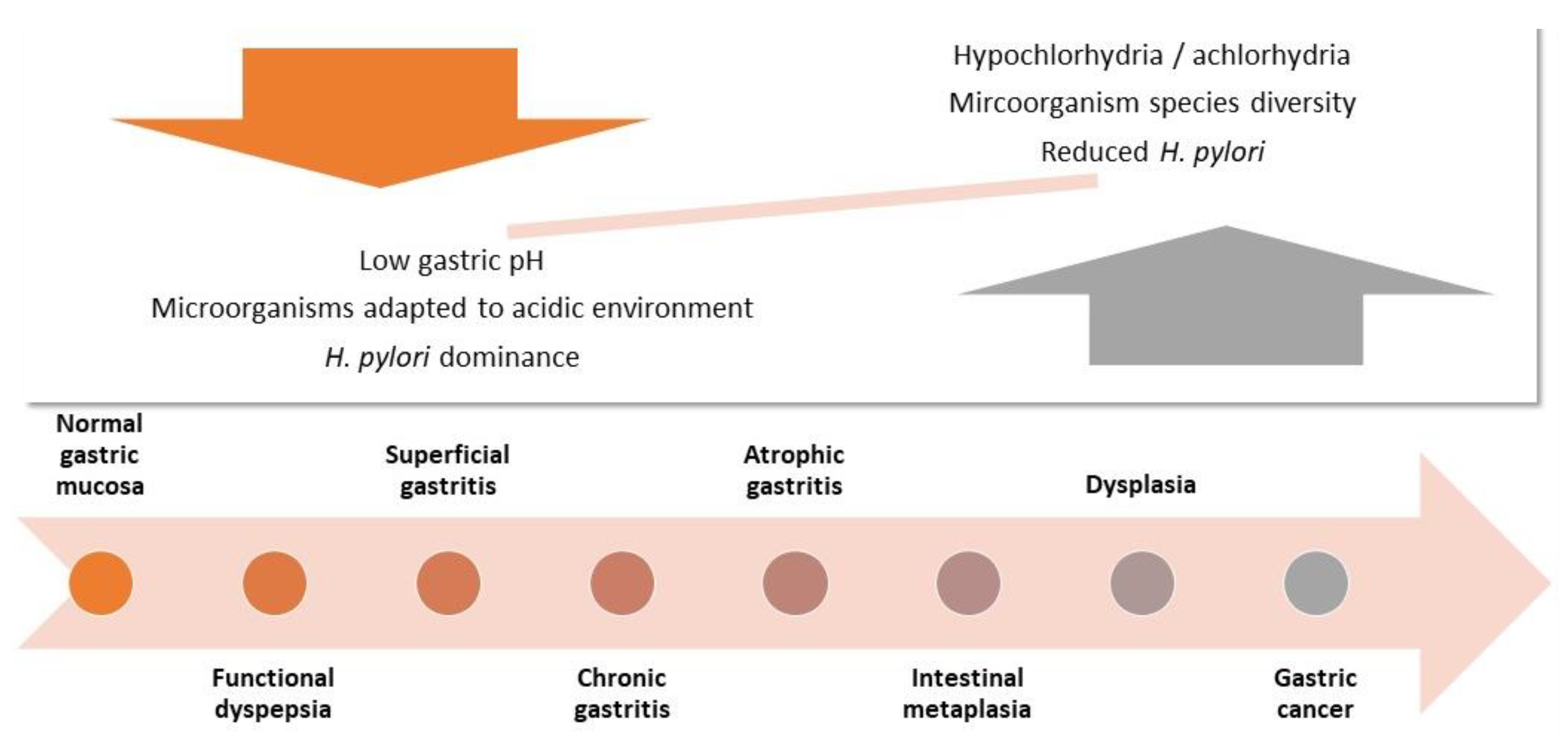

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Patients and Samples

2.2. General Results

2.3. H. pylori

2.4. F. nucleatum

2.5. E. coli

2.6. B. fragilis

2.7. A. baumannii

2.8. Limitations

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Permissions

4.2. Protein Expression Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- American Cancer Society. Available online: www.cancer.org/cancer/stomach-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Poorolajal, J.; Moradi, L.; Mohammadi, Y.; Cheraghi, Z.; Gohari-Ensaf, F. Risk factors for stomach cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Health 2020, 42, e2020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitarz, R.; Skierucha, M.; Mielko, J.; Offerhaus, G.J.A.; Maciejewski, R.; Polkowski, W.P. Gastric cancer: Epidemiology, prevention, classification, and treatment. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferley, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monno, R.; De Laurentiis, V.; Trerotoli, P.; Roselli, A.M.; Ierardi, E.; Portincase, P. Helicobacter pylori infection: Association with dietary habits and socioeconomic conditions. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2019, 43, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn Nam, S.; Park, B.J.; Nam, J.H.; Ryu, K.H.; Kook, M.C.; Kim, J.; Lee, W.K. Association of current Helicobacter pylori infection and metabolic factors with gastric cancer in 35,519 subjects: A cross-sectional study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo Guevara, B.; Cogdill, A.G. Helicobacter pylori: A review of current diagnostic and management strategies. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 1917–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, F.; Campbell, B.J.; Alfizah, H.; Varro, A.; Zahra, R.; Yamaoka, Y.; Pritchard, D.M. Analysis of clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori in Pakistan reveals high degrees of pathogenicity and high frequencies of antibiotic resistance. Helicobacter 2014, 19, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Rasheed, F.; Zahra, R.; König, S. Gastric cancer pre-stage detection and early diagnosis of gastritis using serum protein signatures. Molecules 2022, 27, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; IARC: Lyon, France, 1994; Volume 61, pp. 1–241. [Google Scholar]

- Noto, J.M.; Peek, R.M., Jr. The gastric microbiome, its interaction with Helicobacter pylori, and its potential role in the progression to stomach cancer. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, 1006573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaheed. Helicobacter pylori oncogenicity: Mechanism, prevention, and risk factors. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 3018326.

- Barra, W.F.; Sarquis, D.P.; Khayat, A.S.; Khayat, B.C.M.; Demachki, S.; Anaissi, A.K.M.; Ishak, G.; Santos, N.P.C.; dos Santos, S.E.B.; Burbano, R.R.; et al. Gastric cancer microbiome. Pathobiology 2021, 88, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Yu, H. The role of non-H. pylori bacteria in the development of gastric cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 2271–2281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.; Nell, S.; Suerbaum, S. Survival in hostile territory: The microbiota of the stomach. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 736–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, P.; Piazuelo, M.B. The gastric precancerous cascade. J. Dig. Dis. 2012, 13, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, J.M.; Martens, L. The challenge of metaproteomic analysis in human samples. Exp. Rev. Proteom. 2016, 13, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassignani, A.; Plancade, S.; Berland, M.; Blein-Nicolas, M.; Guillot, A.; Chevret, D.; Moritz, C.; Huet, S.; Rizkalla, S.; Clément, K.; et al. Benefits of iterative searches of large databases to interpret large human gut metaproteomic data sets. J. Proteome Res. 2021, 20, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Tan, Z.; Ding, C.; Zhang, C.; Song, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, M.; Jia, R.; Zhao, C.; Song, L.; et al. A region-resolved mucosa proteome of the human stomach. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, P.G.; Wong, J.; Loo, D.; Zipris, D.; Hill, M.M.; Hamilton-Williams, E.E. Metaproteomic sample preparation methods bias the recovery of host and microbial proteins according to taxa and cellular compartment. J. Proteom. 2021, 240, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruschke, H.; Schori, C.; Canzler, S.; Riesbeck, S.; Poehlein, A.; Daniel, R.; Frei, D.; Segessemann, T.; Zimmermann, J.; Marinos, G.; et al. Discovery of novel community-relevant small proteins in a simplified human intestinal microbiome. Microbiome 2021, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Sterzenbach, R.; Guo, X. Deep learning for peptide identification from metaproteomics datasets. J. Proteom. 2021, 247, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, M. Molecular mechanism of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2021, 52, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.C.; Liou, J.M.; Lee, Y.C.; Hong, T.C.; El-Omar, E.M.; Wu, M.S. The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1909459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Chen, X.Z. Prevalence of atrophic gastritis in southwest China and predictive strength of serum gastrin-17: A cross-sectional study (SIGES). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetz, G.; Tetz, V. Draft genome sequence of Acinetobacter sp. Strain VT-511 isolated from the stomach of a patient with gastric cancer. Prokaryotes 2015, 3, e01202-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, E.T.; Thon, C.; Kupcinskas, J.; Steponaitiene, R.; Skieceviciene, J.; Canbay, A.; Malfertheiner, P.; Link, A. Fusobacterium nucleatum is associated with worse prognosis in Lauren’s diffuse type gastric cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Razavi, S.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E.; Jahanbin, B.; Akbari, A.; Norzaee, S.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Association between colorectal cancer and Fusobacterium nucleatum and Bacteroides fragilis bacteria in Iranian patients: A preliminary study. Infect. Agent Cancer 2021, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Xin, Y.; Geng, C.; Tian, Z.; Yu, X.; Dong, Q. Bacterial overgrowth and diversification of microbiota in gastric cancer. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.T.; Kantilal, H.K.; Davamani, F. The mechanism of Bacteroides fragilis toxin contributes to colon cancer formation. Malays. J. Med. Sci. MJMS 2020, 27, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, M.N.; Sales, R.O.; Silva, K.E.; Maciel, W.G.; Simionatto, S. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreaks: A global problem in healthcare settings. Rev. Da Soc. Bras. De Med. Trop. 2020, 53, e20200248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Riordan, S.M.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L. Escherichia coli K12 upregulates programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in gamma interferon-sensitized intestinal epithelial cells via the NF-κB pathway. Infect. Immun. 2020, 89, e00618-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cell Biology by the Numbers. Available online: http://book.bionumbers.org/what-are-the-most-abundant-proteins-in-a-cell (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Ishihama, Y.; Schmidt, T.; Rappsilber, J.; Mann, M.; Hartl, F.U.; Kerner, M.J.; Frishman, D. Protein abundance profiling of the Escherichia coli cytosol. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, S. Spectral quality overrides software score—A brief tutorial on the analysis of peptide fragmentation data for mass spectrometry laymen. J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 56, e4616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eckburg, P.B.; Bik, E.M.; Bernstein, C.N.; Purdom, E.; Dethlefsen, L.; Sargent, M.; Gill, S.R.; Nelson, K.E.; Relman, D.A. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 2005, 308, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobley, H.L. Urease. In Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics; Mobley, H.L., Mendz, G.L., Hazell, S.L., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y.; Forman, D.; Waskito, L.A.; Yamaoka, Y.; Crabtree, J.E. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and CagA-positive infections and global variations in gastric cancer. Toxins 2018, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.A.; Pernitzsch, S.R.; Haange, S.-B.; Uetz, P.; von Bergen, M.; Sharma, C.M.; Kalkhof, S. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture based proteomics reveals differences in protein abundances between spiral and coccoid forms of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter Pylori. J. Proteom. 2015, 126, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehlke, S.; Yu, J.; Schuppler, M.; Frings, C.; Kirsch, C.; Negraszus, N.; Morgner, A.; Stolte, M.; Ehninger, G.; Bayerdörffer, E. Helicobacter pylori vacA, iceA, and cagA status and pattern of gastritis in patients with malignant and benign gastroduodenal disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudault, S.; Guignot, J.; Servin, A.L. Escherichia coli strains colonising the gastrointestinal tract protect germfree mice against Salmonella typhimurium infection. Gut 2001, 49, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramis, I.B.; Vianna, J.S.; da Silva Junior, L.V.; Von Groll, A.; da Silva, P.E.A. cagE as a biomarker of the pathogenicity of Helicobacter Pylori. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2013, 46, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Day, A.S.; Jones, N.L.; Lynett, J.T.; Jennings, H.A.; Fallone, C.A.; Beech, R.; Sherman, P.M. cagE is a virulence factor associated with Helicobacter pylori-induced duodenal ulceration in children. J. Inf. Dis. 2000, 181, 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Pereira, E.; Magalhães Albuquerque, L.; de Queiroz Balbino, V.; da Silva Junior, W.J.; Rodriguez Burbano, R.M.; Pordeus Gomes, J.P.; Barem Rabenhorst, S.H. Helicobacter pylori cagE, cagG, and cagM can be a prognostic marker for intestinal and diffuse gastric cancer. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 84, 104477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Huang, C.-Y. Structural insight into the DNA-binding mode of the primosomal proteins PriA, PriB, and DnaT. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 195162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondekar, S.M.; Gunjal, G.V.; Radicella, J.P.; Rao, D.N. Molecular dissection of Helicobacter pylori topoisomerase I reveals an additional active site in the carboxyl terminus of the enzyme. DNA Repair 2020, 91–92, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homuth, G.; Domm, S.; Kleiner, D.; Schumann, W. Transcriptional analysis of major heat shock genes of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bact. 2000, 182, 4257–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckers, L.; Tatu, U. Molecular chaperones in pathogen virulence: Emerging new targets for therapy. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, B.J.; Altman, R.B.; Ferrao, R.; Alejo, J.L.; Kaur, N.; Kanji, J.; Blanchard, S.C. Elongation factor Ts directly facilitates the formation and disassembly of the Escherichia coli elongation factor Tu-GTP-aminoacyl-tRNA ternary complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 13917–13928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, M.; Karim, Z.; Yamamoto, H.; Nierhaus, K.H. Elongation factor 4 (EF4/LepA) accelerates protein synthesis at increased Mg2+ concentrations. Proc. Natl. Aacd. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1012994108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hong, Y.; Luan, G.; Mosel, M.; Malik, M.; Drlica, K.; Zhao, X. Ribosomal elongation factor 4 promotes cell death associated with lethal stress. mBio 2014, 5, e01708-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, K.-H.; Wang, L.-H.; Tsai, T.-T.; Lei, H.-Y.; Liao, P.-C. Secretomic analysis of host-pathogen interactions reveals that elongation factor-Tu is a potential adherence factor of Helicobacter pylori during pathogenesis. J. Prot Res. 2017, 16, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, K.L.; Jarocki, V.M. The diverse functional roles of elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) in microbial pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Taylor, D.E. Helicobacter pylori genes hpcopA and hpcopP constitute a cop operon involved in copper export. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1996, 145, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuwahara, T.; Yamashita, A.; Hirakawa, H.; Nakayama, H.; Toh, H.; Okada, N.; Kuhara, S.; Hattori, M.; Hayashi, T.; Ohnishi, Y. Genomic analysis of Bacteroides fragilis reveals extensive DNA inversions regulating cell surface adaptation. Proc. Natl. Aacd. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14919–14924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, H.M. The Genus Bacteroides. In The Prokaryotes: Other Major Lineages of Bacteria and the Archaea; Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 459–484. [Google Scholar]

- Schinzel, R.; Nidetzky, B. Bacterial α-glucan phosphorylases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 171, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, L.; Nodwell, J.R. The TetR family of regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 440–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohl, H.O.; Shi, K.; Lee, J.K.; Aihara, H. Crystal structure of lipid A disaccharide synthase LPXB from Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, G.; Howard, J.; Gan, B.S. Can bacterial interference prevent infection? Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukjancenko, O.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Ussery, D.W. Comparison of 61 sequenced Escherichia coli genomes. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaxybayeva, O.; Doolittle, W.F. Lateral gene transfer. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R242–R246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.J.; Lee, S.Y. The Escherichia coli proteome: Past, present, and future prospects. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006, 70, 362–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signat, S.; Roques, C.; Poulet, P.; Duffaut, D. Fusobacterium nucleatum in periodontal health and disease. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2011, 13, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dorer, M.S.; Fero, J.; Salama, N.R. DNA damage triggers genetic exchange in Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, M.H.; Perrakis, A.; Enzlin, J.H.; Winterwerp, H.H.K.; de Wind, N.; Sixma, T.K. The crystal structure of DNA mismatch repair protein MutS binding to a G-T mismatch. Nature 2000, 407, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, A.W.; Ponkratz, C.; Raleigh, E.A. Rpn (YhgA-like) proteins of Escherichia coli K-12 and their contribution to RecA-independent horizontal transfer. J. Bact. 2017, 199, e00787-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneburg, G.T.; Thanassi, D.G. Pili assembled by the chaperone/usher pathway in Escherichia coli and Salmonella. EcoSal Plus 2018, 8, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lujan, S.A.; Guogas, L.M.; Ragonese, H.; Matson, S.W.; Redinbo, M.R. Disrupting antiobiotic resistance propagation by inhibiting the conjugative DNA relaxase. Proc. Natl. Aacd. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12282–12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speciale, G.; Jin, Y.; Davies, G.J.; Williams, S.J.; Goddard-Borger, E.D. YihQ is a sulfoquinovosidase that cleaves sulfoquinovosyl diacylglyceride sulfolipids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, H.M. Bacteroides: The good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snydman, D.R.; Jacobus, N.V.; McDermott, L.A.; Golan, Y.; Hecht, D.W.; Goldstein, E.J.; Harrell, L.; Jenkins, S.; Newton, D.; Pierson, C.; et al. Lessons learned from the anaerobe survey: Historical perspective and review of the most recent data (2005–2007). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50 (Suppl. 1), S26–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, L.C.S.; Visca, P.; Towner, K.J. Acinetobacter baumannii: Evolution of a global pathogen. Pathog. Dis. 2014, 71, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.B. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: No ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funnell, B.E. ParB partition proteins: Complex formation and spreading at bacterial and plasmid centromeres. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gytz, H.; Liang, J.; Liang, Y.; Gorelik, A.; Illes, K.; Nagar, B. The structure of mammalian β-mannosidase provides insight into β-mannosidosis and nystagmus. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodionov, D.A.; Vitreschak, A.G.; Mirinov, A.A.; Gelfand, M.S. Comparative genomics of the vitamin B12 metabolism and regulation in prokyryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 41148–41159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, N.E. Type I restriction systems: Sophisticated molecular machines. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, H.; Fushinobu, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Kumasaka, T.; Jeon, B.-S.; Wakagi, T.; Matsuzawa, H. Crystal structures of 4-α-glucanotransferase from Thermococcus litoralis and its complex with an inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 19378–19386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinal, P.; Martí, S.; Vila, J. Effect of biofilm formation on the survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 80, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, Y. Prevention of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori eradication: A review from Japan. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3992–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, J.; Mo, L.; Shi, J.; Qin, M.; Huang, X. Efficacy and safety of probiotics in eradicating Helicobacter pylori: A network meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e15180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcaid, M.; Bergeron, A.; Poisson, G. The evolution of the tape measure protein: Units, duplications and losses. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, L.; Bleriot, I.; González de Aledo, M.; Fernández-García, L.; Pacios, O.; Oliveira, H.; López, M.; Ortiz-Cartagena, C.; Fernández-Cuenca, F.; Pascual, A.; et al. Development of an anti-Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm phage cocktail: Genomic adaptation to the host. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e01923-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, P.C.M.; Colloms, S.; Rosser, S.; Stark, M.; Smith, M.C.M. New applications for phage integrases. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 2703–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandi, A.; Piersimoni, L.; Feto, N.A.; Spurio, R.; Alix, J.-H.; Schmidt, F.; Gualerzi, C.O. Translation initiation factor IF2 contributes to ribosome assembly and maturation during cold adaptation. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019, 47, 4652–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Tetu, S.G.; Harrop, S.J.; Paulsen, I.T.; Mabbutt, B.C. Structure of a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) within a genomic island from a clinical strain of Acinetobacter baumannii. Acta Cryst. 2014, F70, 1218–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Sgrignani, J.; Chen, J.J.; Alimonti, A.; Cavalli, A. How phosphorylation influences E1 subunit pyruvate dehydrogenase: A computational study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, M.; Inohara, N.; Nuñez, G. Mechanisms of inflammation-driven bacterial dysbiosis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrouzi, A.; Nafari, A.H.; Siadat, S.D. The significance of microbiome in personalized medicine. Clin. Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Accession | Peptide Count | Unique Peptides | Confidence Score | Max Fold Change | Highest Mean Condition | Lowest Mean Condition | Mass | Description | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. pylori | |||||||||

| Q48252 | 32 | 30 | 201 | 3.5 | PanG | GC | 112,648 | Type IV secretion system protein CagE | cagE |

| P55991 | 30 | 10 | 195 | 2.4 | MaG | MiG | 84,222 | DNA topoisomerase 1 | topA |

| Q9ZMM2 | 11 | 2 | 84 | 2.3 | PanG | GC | 71,311 | Chaperone protein HtpG | htpG |

| B2USI5 | 13 | 4 | 77 | 2.8 | MoG | GC | 67,412 | Elongation factor 4 | lepA |

| Q9ZKE4 | 12 | 3 | 74 | 4.4 | U | NGM | 71,164 | Primosomal protein N’ | priA |

| B5Z9I6 | 11 | 3 | 64 | 2.7 | PanG | NGM | 39,970 | Elongation factor Ts | tsf |

| Q9ZKF6 | 8 | 7 | 52 | 2.3 | MaG | MiG | 62,699 | 30S ribosomal protein S1 | rpsA |

| F. nucleatum | |||||||||

| Q8RGE2 | 46 | 40 | 372 | 2.8 | MaG | NGM | 50,219 | ATP synthase subunit beta | atpD |

| Q8RF61 | 18 | 14 | 109 | 3.5 | MaG | GC | 91,782 | Alpha-1_4 glucan phosphorylase | FN0857 |

| Q8R5Z3 | 13 | 12 | 85 | 2.1 | PanG | NGM | 11,0809 | DNA/RNA helicase (DEAD/DEAH BOX family) | FN1974 |

| Q8RFA3 | 10 | 8 | 75 | 3.1 | PanG | NGM | 44,947 | Transcriptional regulator_TetR family | FN0813 |

| Q8RHQ8 | 12 | 8 | 75 | 2.9 | PanG | GC | 97,405 | Chaperone protein ClpB | clpB |

| Q8RIF1 | 10 | 8 | 73 | 2.3 | PanG | MiG | 30,287 | Oligopeptide transport ATP-binding protein oppD | FN1649 |

| Q8R604 | 11 | 8 | 60 | 2.1 | PanG | MiG | 78,086 | Protein translation elongation factor G (EF-G) | FN1546 |

| E. coli | |||||||||

| P33341 | 17 | 15 | 99 | 2.9 | MoG | GC | 92,510 | Outer membrane usher protein YehB | yehB |

| P23909 | 17 | 3 | 99 | 2.7 | PanG | NGM | 95,589 | DNA mismatch repair protein MutS | mutS |

| P32138 | 13 | 1 | 79 | 2.2 | MaG | GC | 77,902 | Sulfoquinovosidase | yihQ |

| A0A6D2W465 | 14 | 13 | 75 | 4.6 | PanG | NGM | 69,172 | Chaperone protein DnaK | dnaK |

| P14565 | 10 | 9 | 66 | 2.7 | MaG | NGM | 19,2016 | Multifunctional conjugation protein TraI | traI |

| A0A6D2XSN2 | 12 | 9 | 65 | 2.1 | U | MiG | 36,025 | Rpn family recombination-promoting nuclease/putative transposase | FAZ83_12895 |

| A0A4S5B3J9 | 11 | 10 | 62 | 5.0 | MoG | GC | 42,787 | Lipid-A-disaccharide synthase | lpxB |

| A0A6D2XN30 | 8 | 7 | 58 | 2.5 | PanG | MiG | 12,295 | 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 | rplL |

| B. fragilis | |||||||||

| A0A380YYU9 | 77 | 69 | 452 | 2.5 | MaG | GC | 55,261 | ATP synthase subunit beta | atpD |

| Q5LEE2 | 31 | 29 | 182 | 3.8 | MaG | GC | 99,598 | Beta-mannosidase | bmnA |

| A0A380YZS6 | 27 | 25 | 166 | 3.0 | PanG | GC | 148,490 | Putative cobalamin biosynthesis-related membrane protein | cobN_1 |

| Q5LEB7 | 23 | 20 | 143 | 2.6 | MiG | GC | 107,262 | Type I restriction enzyme R Protein | hsdR |

| Q5L9C7 | 19 | 16 | 113 | 2.1 | PanG | GC | 106,621 | 4-alpha-glucanotransferase | malQ |

| Q5L8N9 | 10 | 7 | 57 | 5.6 | MoG | NGM | 73,150 | ParB-like partition proteins | parB_1 |

| A0A380YS49 | 11 | 9 | 56 | 3.5 | PanG | GC | 43,808 | Elongation factor Tu | tuf |

| Q5L7x1 | 8 | 6 | 50 | 2.5 | MoG | NGM | 69,190 | Metal-dependent hydrolase | BF9343_4047 |

| A. baumannii | |||||||||

| A0A009HW70 | 29 | 25 | 152 | 4.1 | PanG | MiG | 144,320 | Tape measure domain protein | J512_0646 |

| A0A009IJB7 | 20 | 16 | 121 | 2.0 | PanG | NGM | 127,978 | Phage integrase family protein | J512_2803 |

| A0A009IU53 | 16 | 9 | 88 | 2.4 | PanG | NGM | 97,429 | Translation initiation factor IF-2 | infB |

| A0A009ILQ7 | 12 | 10 | 66 | 2.9 | PanG | GC | 123,032 | DEAD/DEAH box helicase family protein | J512_2067 |

| A0A009HXA1 | 12 | 8 | 61 | 3.1 | U | NGM | 102,148 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component | aceE |

| A0A009IT43 | 7 | 6 | 50 | 3.9 | U | MiG | 27,161 | Short chain dehydrogenase family protein | J512_0848 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aziz, S.; Rasheed, F.; Akhter, T.S.; Zahra, R.; König, S. Microbial Proteins in Stomach Biopsies Associated with Gastritis, Ulcer, and Gastric Cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175410

Aziz S, Rasheed F, Akhter TS, Zahra R, König S. Microbial Proteins in Stomach Biopsies Associated with Gastritis, Ulcer, and Gastric Cancer. Molecules. 2022; 27(17):5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175410

Chicago/Turabian StyleAziz, Shahid, Faisal Rasheed, Tayyab Saeed Akhter, Rabaab Zahra, and Simone König. 2022. "Microbial Proteins in Stomach Biopsies Associated with Gastritis, Ulcer, and Gastric Cancer" Molecules 27, no. 17: 5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175410

APA StyleAziz, S., Rasheed, F., Akhter, T. S., Zahra, R., & König, S. (2022). Microbial Proteins in Stomach Biopsies Associated with Gastritis, Ulcer, and Gastric Cancer. Molecules, 27(17), 5410. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27175410