The Potential Role of Polyphenols in Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics within the Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

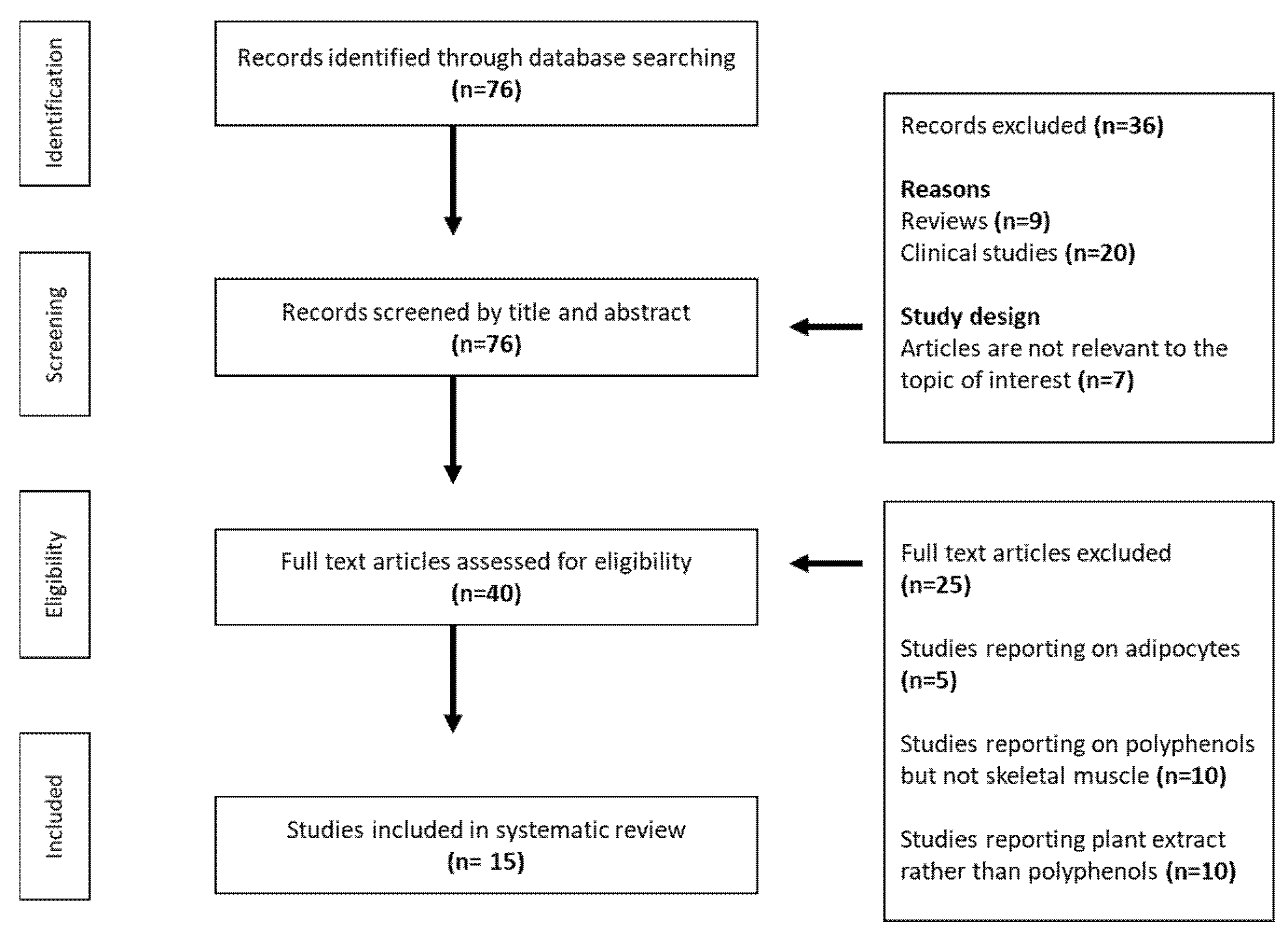

2. Methodology for Study Selection and Inclusion

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Representation

3. Results

3.1. An Overview of Results

3.2. A Brief Overview on Polyphenolic Compounds and Their Impact on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Linked Metabolic Function in Various Preclinical Models

3.2.1. Resveratrol

3.2.2. Gingerol

3.2.3. Quercetin and Naringenin

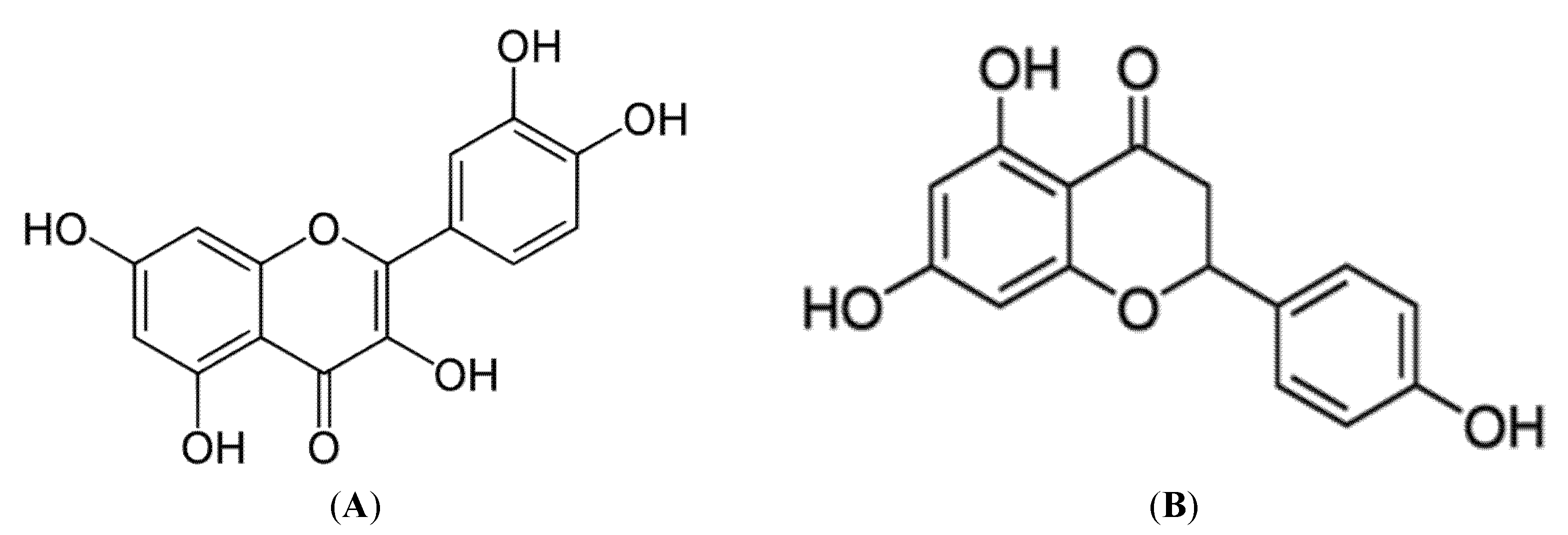

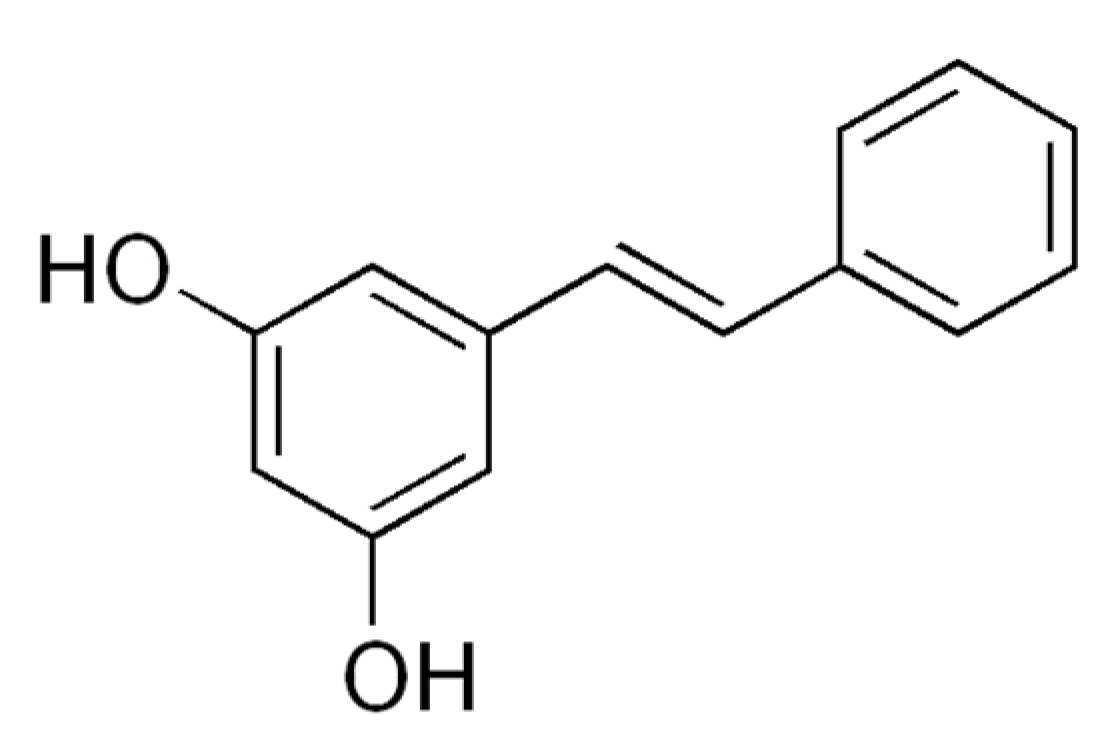

3.2.4. Pinosylvin

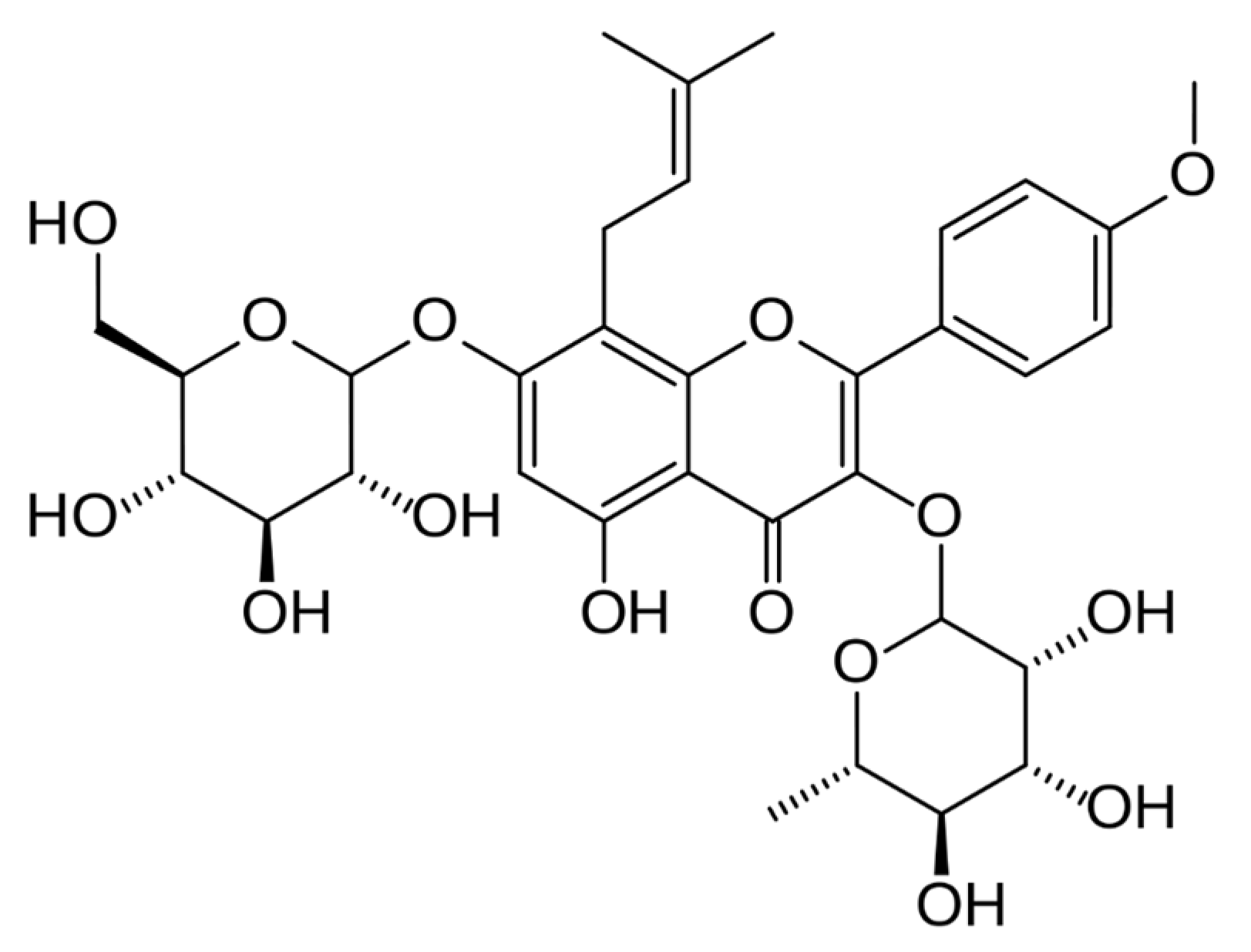

3.2.5. Icariin

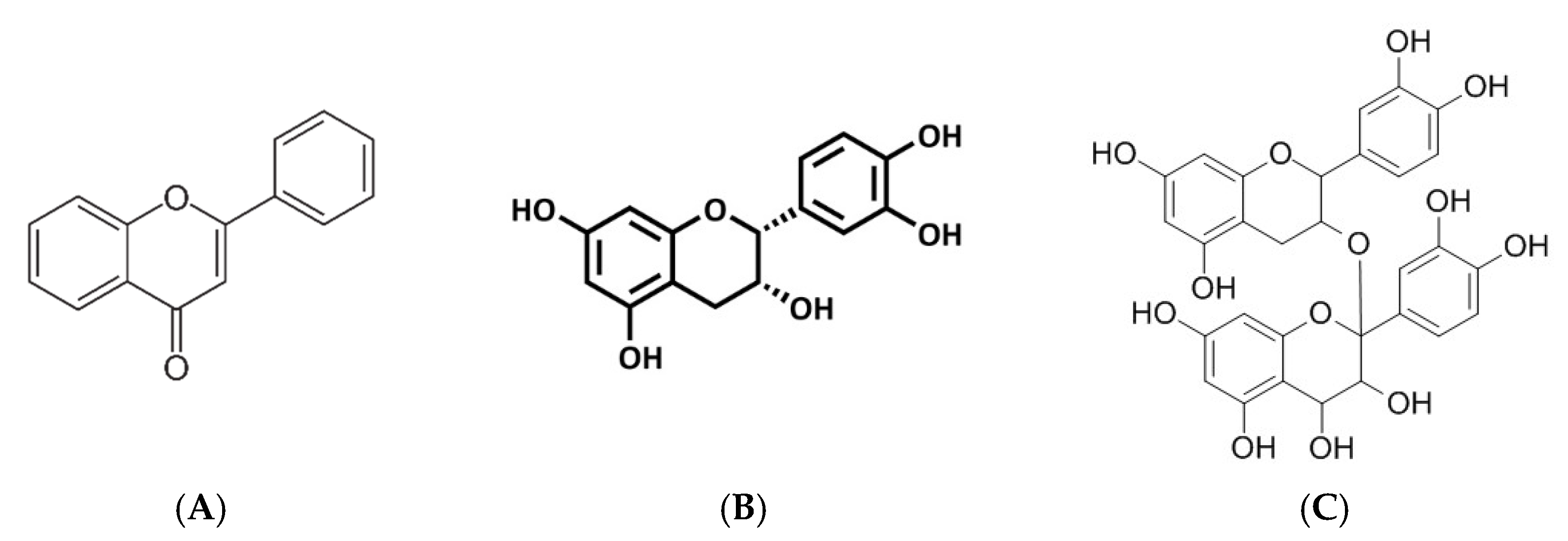

3.2.6. Flavonoids, Flavanols and Proanthocyanidins

4. Summary and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

Abbreviations

References

- Fraga, C.G.; Croft, K.D.; Kennedy, D.O.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. The Effects of Polyphenols and Other Bioactives on Human Health. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant Polyphenols as Dietary Antioxidants in Human Health and Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, 2, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Colombo, F.; Biella, S.; Stockley, C.; Restani, P. Polyphenols and Human Health: The Role of Bioavailability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, C.J.F.; Malherbe, C.J.; Chellan, N.; Yagasaki, K.; Miura, Y.; Joubert, E. Potential of rooibos, its major C-glucosyl flavonoids, and Z-2-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-3-phenylpropenoic acid in prevention of metabolic syndrome. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xiao, J.; Chen, S.; Yu, Y.; Ma, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, R.; Lin, J.; Fu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Metabolite signatures of diverse Camellia sinensis tea populations. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnewick, J.L.; Rautenbach, F.; Venter, I.; Neethling, H.; Blackhurst, D.M.; Wolmarans, P.; MacHaria, M. Effects of rooibos (Aspalathus linearis) on oxidative stress and biochemical parameters in adults at risk for cardiovascular disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, R.A.; Richmond, R.C.; Santos Ferreira, D.L.; Ness, A.R.; May, M.; Smith, G.D.; Vincent, E.E.; Adams, C.; Ala-Korpela, M.; Würtz, P.; et al. Investigating the effects of lycopene and green tea on the metabolome of men at risk of prostate cancer: The ProDiet randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1918–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dludla, P.V.; Johnson, R.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Muller, C.J.F.; Louw, J.; Joubert, E.; Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Chellan, N.; Nkambule, B.B.; et al. Fermented rooibos extract attenuates hyperglycemia-induced myocardial oxidative damage by improving mitochondrial energetics and intracellular antioxidant capacity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 131, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Dludla, P.V.; Johnson, R.; Joubert, E.; Louw, J.; Ziqubu, K.; Tiano, L.; Silvestri, S.; Orlando, P.; Opoku, A.R.; et al. Aspalathin, a natural product with the potential to reverse hepatic insulin resistance by improving energy metabolism and mitochondrial respiration. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Ziqubu, K.; Dludla, P.V.; Tiano, L.; Silvestri, S.; Orlando, P.; Nyawo, T.A.; Louw, J.; Kappo, A.P.; Muller, C.J. Isoorientin ameliorates lipid accumulation by regulating fat browning in palmitate-exposed 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Metab. Open. 2020, 6, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Dludla, P.V.; Roux, C.; Johnson, R.; Ghoor, S.; Joubert, E.; Louw, J.; Opoku, A.R.; Muller, C.J. Aspalathin-enriched green rooibos extract reduces hepatic insulin resistance by modulating PI3K/AKT and AMPK pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Zhang, J.-R.; Li, H.-B.; Wu, D.-T.; Geng, F.; Corke, H.; Wei, X.-L.; Gan, R.-Y. Green Extraction of Antioxidant Polyphenols from Green Tea (Camellia sinensis). Antioxidants 2020, 9, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.L.; Zhang, H.H.; Zheng, J.; Hu, X.; Kong, W.; Hu, D.; Wang, S.X.; Zhang, P. Resveratrol attenuates high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance by influencing skeletal muscle lipid transport and subsarcolemmal mitochondrial β-oxidation. Metabolism 2011, 60, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainampetch, J.; Panprathip, P.; Phosat, C.; Chumpathat, N.; Prangthip, P.; Soonthornworasiri, N.; Puduang, S.; Wechjakwen, N.; Kwanbunjan, K. Association of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha, Interleukin 6, and C-Reactive Protein with the Risk of Developing Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Cohort Study of Rural Thais. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, V.-L.; Jun, M.; Jeong, W.-S. Role of resveratrol in regulation of cellular defense systems against oxidative stress. BioFactors 2018, 44, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, K.; Lang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, P.; Ran, L.; Zhou, M.; Zheng, J.; Yi, L.; et al. Resveratrol prevents sarcopenic obesity by reversing mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress via the PKA/LKB1/AMPK pathway. Aging 2019, 11, 2217–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Meo, S.; Iossa, S.; Venditti, P. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance: Role of mitochondria and other ROS sources. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 233, R15–R42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coudray, C.; Fouret, G.; Lambert, K.; Ferreri, C.; Rieusset, J.; Blachnio-Zabielska, A.; Lecomte, J.; Ebabe Elle, R.; Badia, E.; Murphy, M.P.; et al. A mitochondrial-targeted ubiquinone modulates muscle lipid profile and improves mitochondrial respiration in obesogenic diet-fed rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, W.; Rud, K.A.; Mortensen, O.H.; Frandsen, L.; Grunnet, N.; Quistorff, B. Your mitochondria are what you eat: A high-fat or a high-sucrose diet eliminates metabolic flexibility in isolated mitochondria from rat skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.L.; Gomes, A.P.; Ling, A.J.Y.; Duarte, F.V.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; North, B.J.; Agarwal, B.; Ye, L.; Ramadori, G.; Teodoro, J.S.; et al. SIRT1 is required for AMPK activation and the beneficial effects of resveratrol on mitochondrial function. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Tripathi, P.; Sharma, J.; Dixit, A. Flavonoids modulate tight junction barrier functions in hyperglycemic human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Nutrition 2020, 78, 110792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashida, K.; Kim, S.H.; Jung, S.R.; Asaka, M.; Holloszy, J.O.; Han, D.H. Effects of Resveratrol and SIRT1 on PGC-1α Activity and Mitochondrial Biogenesis: A Reevaluation. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zuo, S.; Xin, W. miR-27b overexpression improves mitochondrial function in a Sirt1-dependent manner. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 71, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tran, V.H.; Kota, B.P.; Nammi, S.; Duke, C.C.; Roufogalis, B.D. Preventative effect of zingiber officinale on insulin resistance in a high-fat high-carbohydrate diet-fed rat model and its mechanism of action. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 115, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlur Krishnamoorthy, R.; Carani Venkatraman, A. Polyphenols activate energy sensing network in insulin resistant models. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 275, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Yaluri, N.; Kokkola, T.; Laakso, M. Plant-derived compounds strigolactone GR24 and pinosylvin activate SIRT1 and enhance glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.Q.; Ding, L.N.; Zeng, N.X.; Liu, H.M.; Zheng, S.H.; Xu, J.W.; Li, R.M. Icariin induces irisin/FNDC5 expression in C2C12 cells via the AMPK pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Qi, X.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, P.; Yu, X.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Flavonoids extracted from mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaf improve skeletal muscle mitochondrial function by activating AMPK in type 2 diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248, 112326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol Improves Mitochondrial Function and Protects against Metabolic Disease by Activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, L.L.; Zhang, H.H.; Hu, X.; Kong, W.; Hu, D. Resveratrol improves insulin resistance of catch-up growth by increasing mitochondrial complexes and antioxidant function in skeletal muscle. Metabolism 2012, 61, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haohao, Z.; Guijun, Q.; Juan, Z.; Wen, K.; Lulu, C. Resveratrol improves high-fat diet induced insulin resistance by rebalancing subsarcolemmal mitochondrial oxidation and antioxidantion. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 71, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajuelo, D.; Fernández-Iglesias, A.; Díaz, S.; Quesada, H.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Bladé, C.; Salvadó, J.; Arola, L. Improvement of mitochondrial function in muscle of genetically obese rats after chronic supplementation with proanthocyanidins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8491–8498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, E.; Baselga-Escudero, L.; Ribas-Latre, A.; Cedó, L.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Pinent, M.; Bladé, C.; Arola, L.; Salvadó, M.J. Chronic intake of proanthocyanidins and docosahexaenoic acid improves skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in diet-obese rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, N.; Inagawa, K.; Shibata, M.; Osakabe, N. Flavan-3-Ol Fraction from Cocoa Powder Promotes Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle in Mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shrikanta, A.; Kumar, A.; Govindaswamy, V. Resveratrol content and antioxidant properties of underutilized fruits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marier, J.F.; Vachon, P.; Gritsas, A.; Zhang, J.; Moreau, J.P.; Ducharme, M.P. Metabolism and disposition of resveratrol in rats: Extent of absorption, glucuronidation, and enterohepatic recirculation evidenced by a linked-rat model. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 302, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resveratrol|CAS:501-36-0|Price: $30/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Resveratrol-CFN98791.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Wang, Q.; Wei, Q.; Yang, Q.; Cao, X.; Li, Q.; Shi, F.; Tong, S.S.; Feng, C.; Yu, Q.; Yu, J.; et al. A novel formulation of [6]-gingerol: Proliposomes with enhanced oral bioavailability and antitumor effect. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Firempong, C.K.; Zhu, Y.; Omari-Siaw, E.; Zheng, Y.; Pu, Z.; Xu, X.; Yu, J. Enhanced oral bioavailability of [6]-Gingerol-SMEDDS: Preparation, in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 27, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkor, H.R.; Mansour, S.W.; Ramadan, G. Modulatory effects of garlic, ginger, turmeric and their mixture on hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-nicotinamide diabetic rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 105, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.B.; Lin, C.C.; Tsay, G.J. 6-gingerol inhibits growth of colon cancer cell LoVo via induction of G2/M arrest. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugasani, S.; Rao Pichika, M.; Nadarajah, V.D.; Katyayani Balijepalli, M.; Tandra, S.; Narsimha Korlakunta, J. Comparative antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of [6]-gingerol, [8]-gingerol, [10]-gingerol and [6]-shogaol. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Yadav, A. Gingerol Derivatives as 14α-demethylase Inhibitors: Design and Development of Natural, Safe Antifungals for Immune-compromised Patients. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2020, 17, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tran, V.; Duke, C.; Roufogalis, B. Gingerols of Zingiber officinale Enhance Glucose Uptake by Increasing Cell Surface GLUT4 in Cultured L6 Myotubes. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samad, M.B.; Mohsin, M.N.A.B.; Razu, B.A.; Hossain, M.T.; Mahzabeen, S.; Unnoor, N.; Muna, I.A.; Akhter, F.; Kabir, A.U.; Hannan, J.M.A. [6]-Gingerol, from Zingiber officinale, potentiates GLP-1 mediated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion pathway in pancreatic β-cells and increases RAB8/RAB10-regulated membrane presentation of GLUT4 transporters in skeletal muscle to improve hyperglycemia in Leprdb/db type 2 diabetic mice. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 6-Gingerol|CAS:23513-14-6|Price: $80/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/6-Gingerol-CFN99931.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Alrawaiq, N.S.; Abdullah, A. A review of flavonoid quercetin: Metabolism, bioactivity and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Pharm Tech Res. 2014, 6, 933–941. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, O.M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Fahim, H.I.; Zaky, M.Y. Quercetin and naringenin abate diethylnitrosamine/acetylaminofluorene-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in Wistar rats: The roles of oxidative stress, inflammation and cell apoptosis. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, B.; Liu, Z.J.; Chen, Z.F.; Ouyang, Y.; Hu, Y.J. Understanding the structure-activity relationship between quercetin and naringenin: In vitro. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 106171–106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.Y.; Banh, T.; Hsiao, Y.H.; Cole, R.M.; Straka, S.R.; Yee, L.D.; Belury, M.A. Citrus flavonoid naringenin reduces mammary tumor cell viability, adipose mass, and adipose inflammation in obese ovariectomized mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Kauter, K.; Brown, L. Naringin Improves Diet-Induced Cardiovascular Dysfunction and Obesity in High Carbohydrate, High Fat Diet-Fed Rats. Nutrients 2013, 5, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quercetin|CAS:117-39-5|Price: $40/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Quercetin-CFN99272.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Naringenin|CAS:480-41-1|Price: $30/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Naringenin-CFN98742.html (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Eräsalo, H.; Hämäläinen, M.; Leppänen, T.; Mäki-Opas, I.; Laavola, M.; Haavikko, R.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Moilanen, E. Natural Stilbenoids Have Anti-Inflammatory Properties in Vivo and Down-Regulate the Production of Inflammatory Mediators NO, IL6, and MCP1 Possibly in a PI3K/Akt-Dependent Manner. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahedi, H.M.; Ahmad, S.; Abbasi, S.W. Stilbene-based natural compounds as promising drug candidates against COVID-19. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinosylvin|CAS:22139-77-1|Price: $288/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Pinosylvin-CFN98203.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Pecyna, P.; Wargula, J.; Murias, M.; Kucinska, M. More Than Resveratrol: New Insights into Stilbene-Based Compounds. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.S.; Song, S.L.; Liang, H.; Ji, A.G. Icariin inhibits atherosclerosis progress in Apoe null mice by downregulating CX3CR1 in macrophage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 470, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Sun, B.; Liu, K.; Yan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, C.; Ren, L. Icariin Attenuates High-cholesterol Diet Induced Atherosclerosis in Rats by Inhibition of Inflammatory Response and p38 MAPK Signaling Pathway. Inflammation 2016, 39, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Jung, H.W.; Park, Y.K. Effects of Icariin on insulin resistance via the activation of AMPK pathway in C2C12 mouse muscle cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 758, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Icariin|CAS:489-32-7|Price: $30/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Icariin-CFN99554.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Han, L.Y.; Wu, Y.L.; Zhu, C.Y.; Wu, C.S.; Yang, C.R. Improved pharmacokinetics of icariin (ica) within formulation of peg-plla/pdla-pnipam polymeric micelles. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, G.; Shams-White, M.; Avendano, E.E.; Chen, F.; Novotny, J.A.; Cassidy, A. Dietary intakes of flavan-3-ols and cardiovascular health: A field synopsis using evidence mapping of randomized trials and prospective cohort studies. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Asamenew, G.; Choi, J.; Lee, J.W.; Jung, H.A.; Yoo, S.M.; Kim, J.B. Characterization of catechins, theaflavins, and flavonols by leaf processing step in green and black teas (Camellia sinensis) using UPLC-DAD-QToF/MS. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Flavanols: Catechins and proanthocyanidins. In Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1753–1801. ISBN 9783642221446. [Google Scholar]

- Legeay, S.; Rodier, M.; Fillon, L.; Faure, S.; Clere, N. Epigallocatechin Gallate: A Review of Its Beneficial Properties to Prevent Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5443–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flavone|CAS:525-82-6|Price: $30/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Flavone-CFN70130.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Proanthocyanidins|CAS:4852-22-6|Price: $70/20 mg|Manufacturer ChemFaces. Available online: http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Proanthocyanidins-CFN99556.html (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Nair, H.B.; Sung, B.; Yadav, V.R.; Kannappan, R.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Delivery of antiinflammatory nutraceuticals by nanoparticles for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, W. Dietary polyphenols-important non-nutrients in the prevention of chronic noncommunicable diseases. A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, A.; Paoletta, M.; Liguori, S.; Bertone, M.; Toro, G.; Iolascon, G. Choline: An Essential Nutrient for Skeletal Muscle. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Polyphenols | Experimental Model | Effective Dose and Duration | Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resveratrol | C2C12 myoblast | 25 µM resveratrol for 24 h | Enhanced mitochondrial function and biogenesis in a NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1 (SIRT1)-dependent manner. This included increasing ATP content and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC1α) protein expression | [21] |

| C2C12 myotubes | 20 or 50 µM resveratrol for 6 or 24 h, respectively | High dose reduced ATP production and activated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation. Resveratrol induced overexpression of SIRT1 decreased PGC1α acetylation and PGC1α coactivator activity | [23] | |

| C2C12 myoblast | 20, 40, 60 μM resveratrol for 24 h | Increased miR-27b expression and mtDNA, which improved mitochondrial function and glucose uptake in a Sirt1-dependent manner | [24] | |

| Palmitate-induced mitochondrial dysfunction C2C12 myotubes | 25 μM resveratrol for 24 h | Ameliorated mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress as evident by improved mtDNA content and increased expression of mitochondrial biogenesis-r elated protein including PGC1α, mitochondrial transcription factor (TFAM), mitofusin 2 (mfn2), and drosophila melanogaster (drp1), as well as reduced ROS production | [17] | |

| (S)-[6]-gingerol | L6 rat myotubes | 50, 100 and 150 µM (S)-[6]-gingerol for 24 h | Activated AMPKα, which was accompanied by an increased mitochondrial content number, as well as an improved gene expression of PGC-1α | [25] |

| Naringenin and quercetin | Palmitate-induced insulin resistance L6 myotubes | 75 µM naringenin or 750 mM quercetin for 16 h | Increased glucose transporter (GLUT)4 translocation, AMPK phosphorylation, and SIRT1 and PGC1α expression | [26] |

| Pinosylvin | Rats L6 myotubes | 20 or 60 µM pinosylvin for 24 h | Pinosylvin activated SIRT1 in vitro and stimulated glucose uptake through the activation of AMPK | [27] |

| Icariin | C2C12 myocytes | 20, 40, 80 μg/mL icariin for 24 h | Increased irisin/fibronectin type lll domain containing 5 (FNDC5), PGC1α gene expression, and dose-dependently increased AMPK phosphorylation | [28] |

| Flavonoids (mulberry.) | Palmitate-induced insulin resistance L6 myotubes | 100 nmol/L insulin, 0.75 mmol/L Palmitic acid (PA) and MLF (5,10, 20, 40 and 80μg/mL) for 24 h | MLF and metformin significantly ameliorated glucose uptake by activating AMPK and reduced ROS production in L6 cells. Furthermore, MLF improved mitochondrial function by increasing the expression of PGC1α | [29] |

| Polyphenols | Experimental Model | Effective Dose and Duration | Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resveratrol | High-fat diet (HFD) induced obese C57BL/6J mice | 400 mg/kg/day resveratrol for 15 weeks | Increased oxygen consumption was accompanied by regulation of the genes for mitochondrial biogenesis such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α (PGC1α) acetylation and activity | [30] |

| HFD-fed Sprague Dawley rats | 100 mg/kg b.w./day resveratrol for 8 weeks | Reduced intramuscular lipid accumulation and ameliorated insulin resistance, in part by enhancing NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activity, increasing mitochondrial biogenesis and β-oxidation | [14] | |

| Catch-up growth-induced insulin resistance Sprague Dawley rats | 100 mg/kg b.w./day resveratrol treatment for 4 and 8 weeks | Enhanced SIRT1 activity and improved mitochondrial number and insulin sensitivity, as well as decreased levels of reactive oxygen species and restored antioxidant enzyme activities, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) | [31] | |

| C57/BL6J mice | 25–30 mg/kg b.w/day (low dose) and 215–230 mg/kg b.w/day (high dose) resveratrol for 8 months | 50 μM dose significantly decreased ATP levels early as 1 h after treatment and activated AMPK independently of SIRT1. At 25 µM resveratrol increased mitochondrial function by increased expression of PGC1α, PGC1β, and TFAM including the transcription factor B2 (TFB2M) in a SIRT1-dependent manner. This was also supported by an increase on mtDNA content. Furthermore, resveratrol AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and increased NAD+ levels | [21] | |

| HFD-induced insulin resistance Sprague Dawley rats | 100 mg/kg/day resveratrol for 8 weeks | Ameliorated insulin resistance through increased SIRT1 and SIRT3 expressions and elevated mtDNA and mitochondrial biogenesis. This included enhancing mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes including SOD, CAT, and GPx | [32] | |

| HFD-fed C57BL/6J mice | 0.02, 0.04, and 0.06% resveratrol for 12 weeks | Reduced the plasma insulin and glucose concentrations, which were accompanied by an increased miR-27b overexpression, which improved mitochondrial function in a Sirt1-dependent manner | [24] | |

| HFD-induced sarcopenic obesity Sprague Dawley rats | 0.4% resveratrol for 20 weeks | Ameliorated mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress via the serine–threonine kinase LKB1 (PKA/LKB1)/AMPK pathway. This was evident by increased activity of complexes I, II, and IV, and raised PGC1α, TFAM, and mfn2, as well as decreased drp1 expression. Moreover, there was an increase in the total antioxidative capability (T-AOC), SOD, GPx, MDA, and carbonyl protein | [17] | |

| Proanthocyanidins | Obese Zucker fatty rats (fa/fa) | 35 mg/kg b.w./day proanthocyanidins 68 days | Decreased citrate synthase activity and oxidative phosphorylation complexes I and II levels and Nrf1 gene expression, which in turn reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production | [33] |

| Diet-induced obese Wistar rats | 25 mg/kg b.w./day proanthocyanidins for 21 days | Reduced insulin resistance, improved mitochondrial respiration, mitochondrial oxidative capacity, and fatty acid oxidation as evident by increased mitochondrial enzymatic activities, AMPK phosphorylation, and the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (Pparα) and UCP2 | [34] | |

| Flavan 3-ols fraction derived from cocoa powder | C57BL/J mice | 50 mg/kg b.w./day flavan-3-ols for 2 weeks | Enhanced lipolysis and promoted mitochondrial biogenesis marked by increased carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2) expression and mitochondria copy number | [35] |

| Naringenin and quercetin | High-fructose diet-induced insulin resistance Wistar rats | 50 mg/kg b.w./day naringenin and quercetin for 6 weeks | Both naringenin and quercetin reduced the plasma glucose and insulin levels accompanied by a significant increase in SIRT1 and PGC1α expression, AMPK phosphorylation, and glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation | [26] |

| Icariin | C57BL/6 mice | 10 or 40 mg/kg/day icariin for 14 days | Decrease in body weight gain by increasing FNDC5, PGC-1α, and p-AMPK expression levels | [28] |

| Flavonoids | Type 2 diabetic (db/db) mice | 180 mg/kg flavonoids for 7 weeks | Ameliorated insulin resistance and symptoms associated with diabetes through increased p-AMPK and PGC1α, raised m-GLUT4 and T-GLUT4 protein expression, and improved mitochondrial function | [29] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mthembu, S.X.H.; Dludla, P.V.; Ziqubu, K.; Nyambuya, T.M.; Kappo, A.P.; Madoroba, E.; Nyawo, T.A.; Nkambule, B.B.; Silvestri, S.; Muller, C.J.F.; et al. The Potential Role of Polyphenols in Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics within the Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Models. Molecules 2021, 26, 2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092791

Mthembu SXH, Dludla PV, Ziqubu K, Nyambuya TM, Kappo AP, Madoroba E, Nyawo TA, Nkambule BB, Silvestri S, Muller CJF, et al. The Potential Role of Polyphenols in Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics within the Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Models. Molecules. 2021; 26(9):2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092791

Chicago/Turabian StyleMthembu, Sinenhlanhla X. H., Phiwayinkosi V. Dludla, Khanyisani Ziqubu, Tawanda M. Nyambuya, Abidemi P. Kappo, Evelyn Madoroba, Thembeka A. Nyawo, Bongani B. Nkambule, Sonia Silvestri, Christo J. F. Muller, and et al. 2021. "The Potential Role of Polyphenols in Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics within the Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Models" Molecules 26, no. 9: 2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092791

APA StyleMthembu, S. X. H., Dludla, P. V., Ziqubu, K., Nyambuya, T. M., Kappo, A. P., Madoroba, E., Nyawo, T. A., Nkambule, B. B., Silvestri, S., Muller, C. J. F., & Mazibuko-Mbeje, S. E. (2021). The Potential Role of Polyphenols in Modulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics within the Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Models. Molecules, 26(9), 2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092791