Regulatory Role of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Wound Healing Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Wound Healing Process

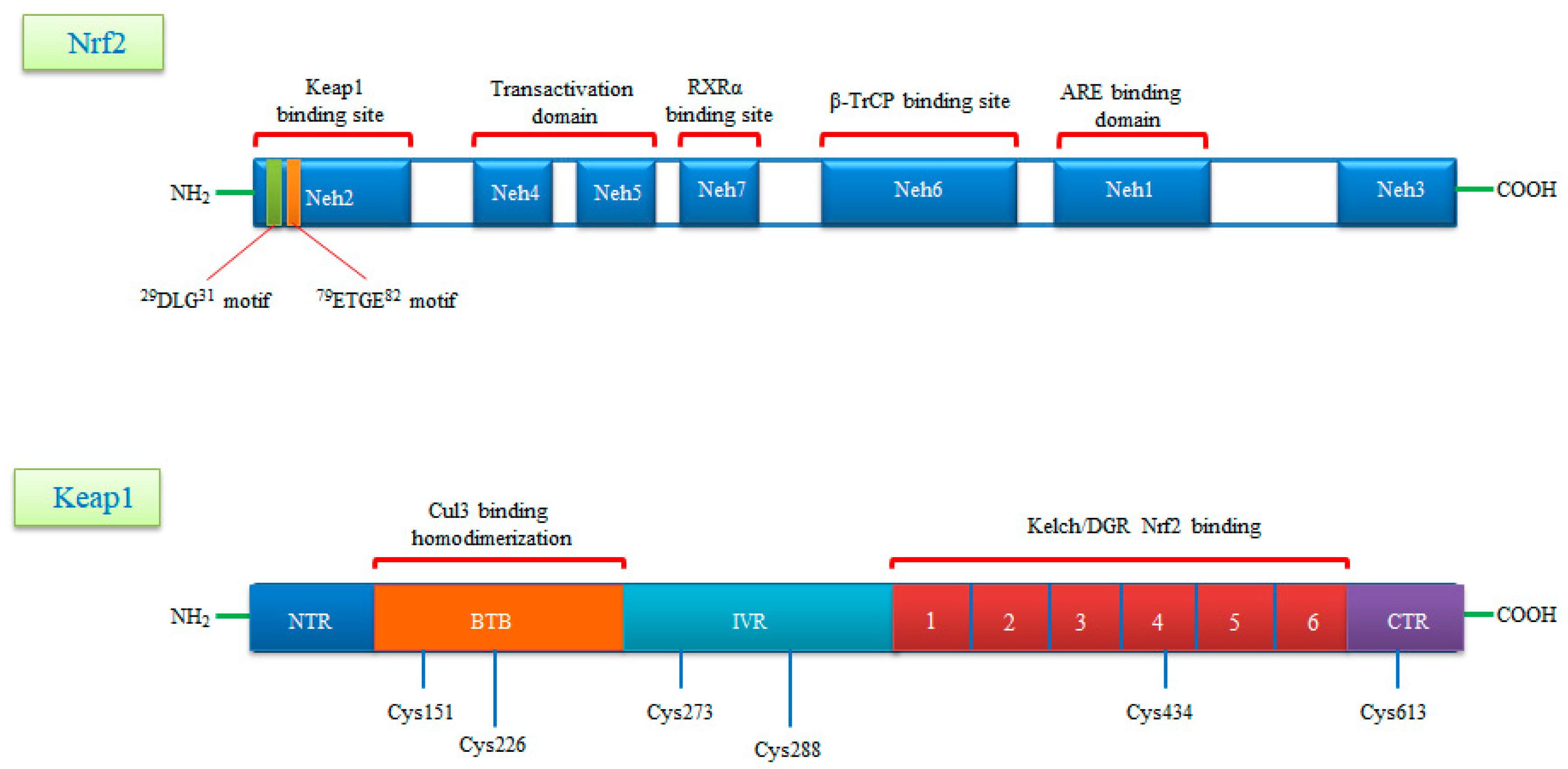

3. Gene Structure of Nrf2 Transcription Factor and Its Repressor Keap1

4. Nrf2 Signaling: Mechanisms of Activation and Suppression

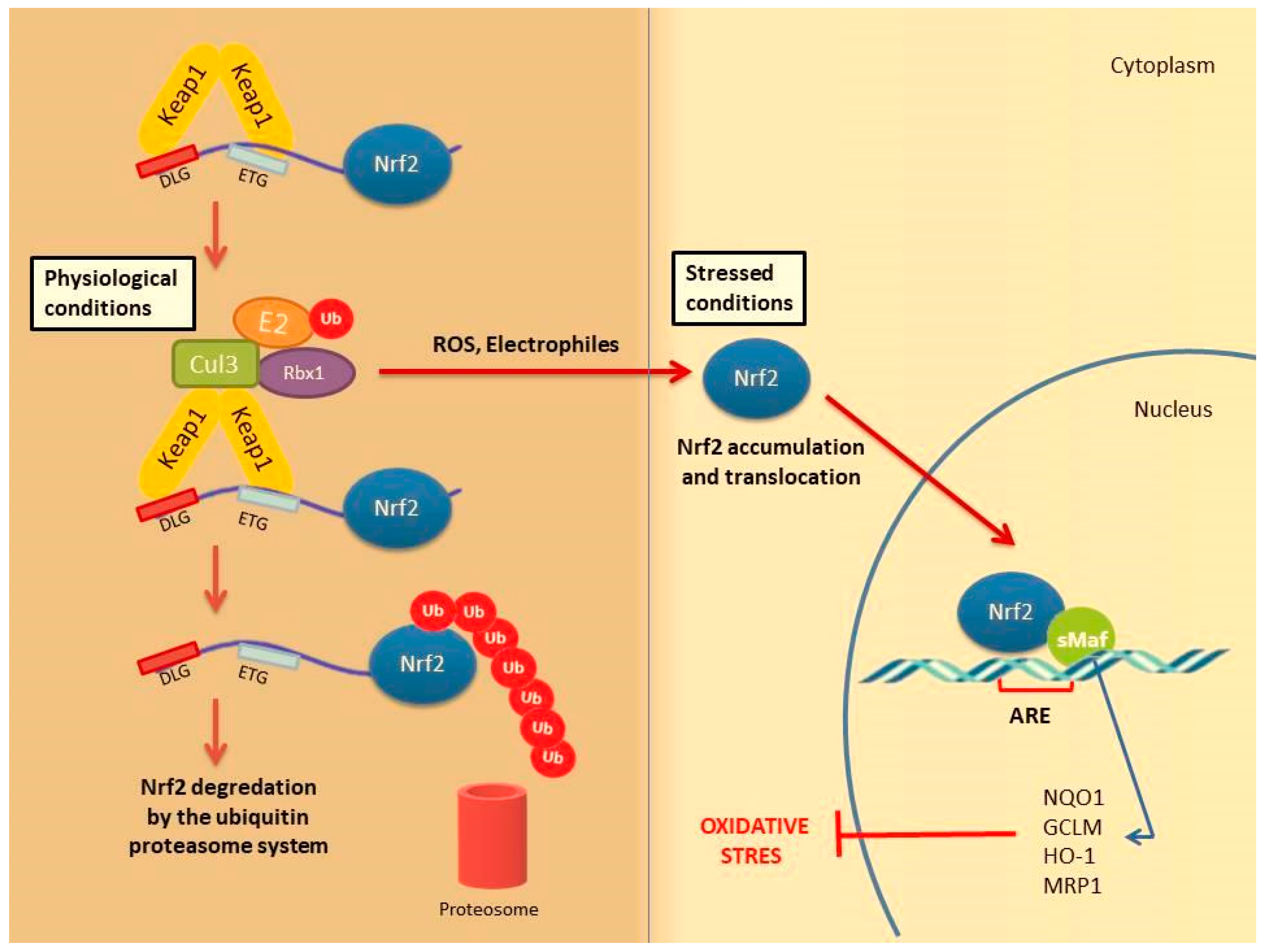

4.1. Canonical Activation of Nrf2

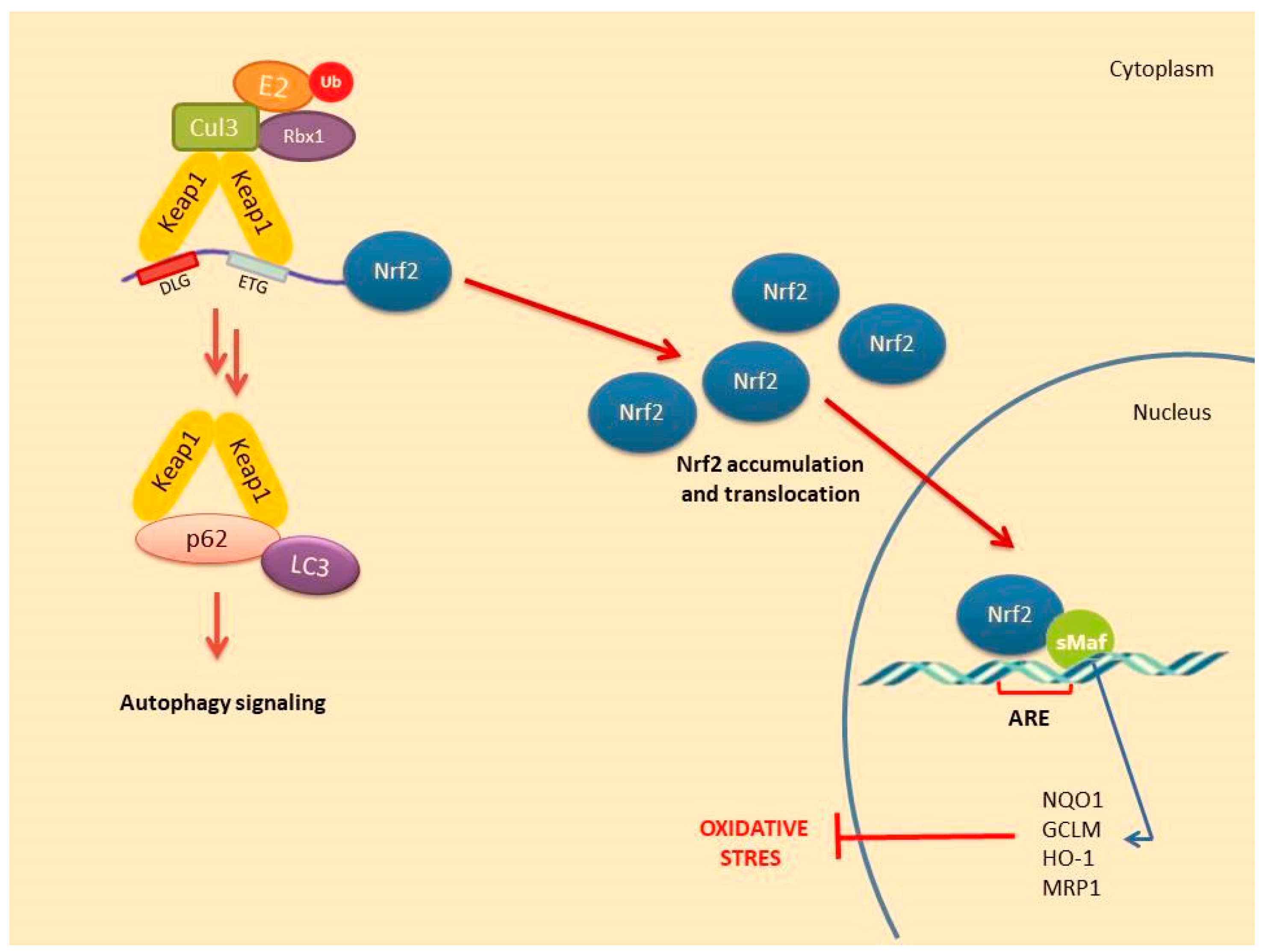

4.2. Non-Canonical Activation of Nrf2: The Role of Autophagy

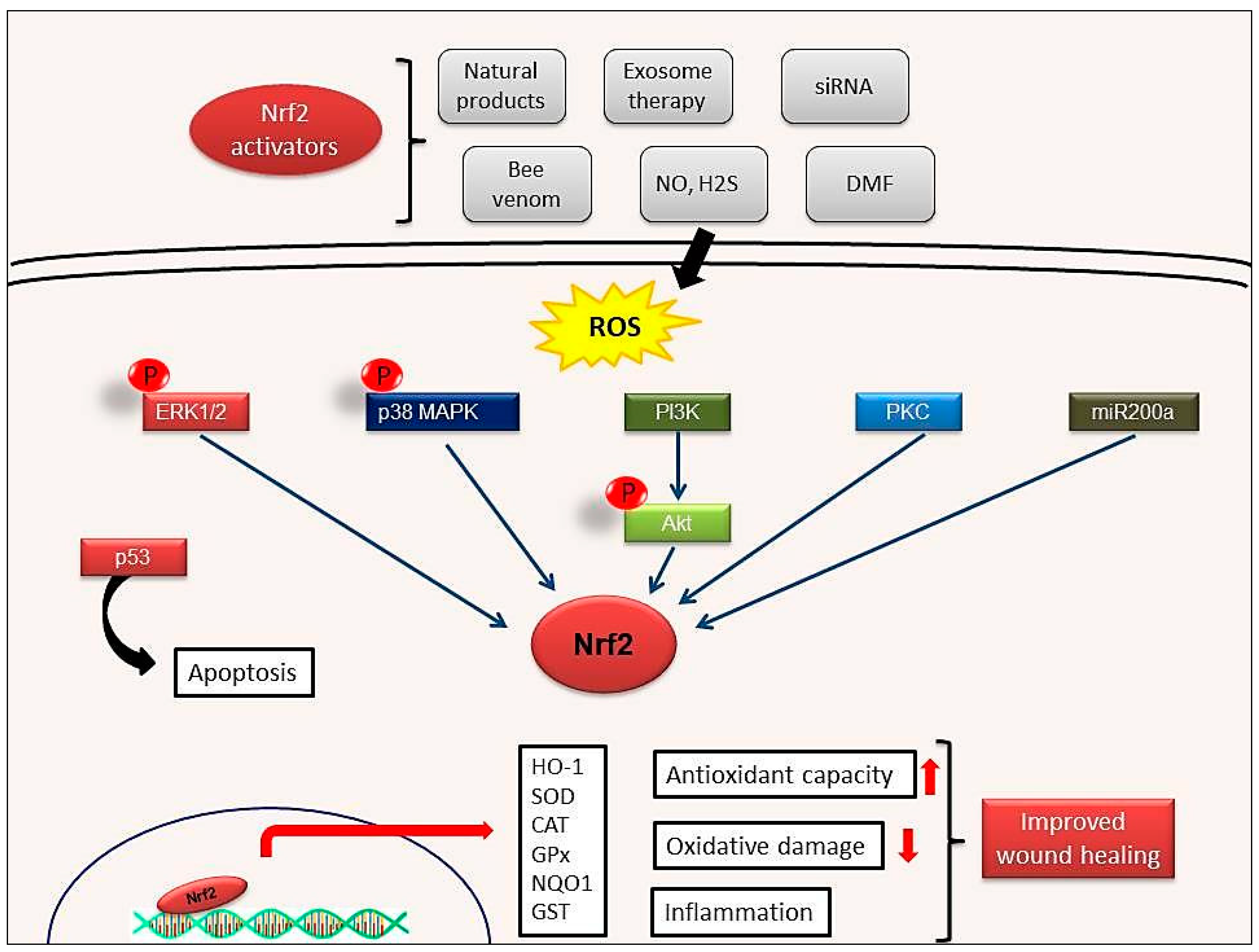

5. Nrf2 Activation during Wound Healing

6. The Role of Nrf2 in Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis and Migration during Wound Repair

| Model | Injury | Method of Application | Treatment | Studied on | Results | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in vivo | BLM-induced skin fibrosis | s.c. injection | - | Nrf2−/− mice generated with Keratin 14-Cre/loxp system | Increased cytokines & chemokines expression (Mep-1, IL-6, IL-8) | [64] |

| in vivo | Corneal epithelial injury | i.m. injection | - | Nrf2−/− mice | Induction of cell migration and inhibition of cell proliferation | [66] |

| in vivo | Endothelial cell injury | skin incision | - | Nrf2−/− C57BL/6 mice | VEGF-induced proliferation ↓ Endothelial cell sprout formation ↓ | [75] |

| in vitro | Retinal pericytes, astrocytes and endothelial cells | - | - | Blood-retinal barrier model | Increased IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, Nox2 expression Activation of Nrf2 and HO-1 | [76] |

| in vivo | Epidermal keratinocyte | i.p. injection (dorsal skin 10 mm) | - | Leprdb/db mice | Increased expression of Nqo1 and Sod2 genes due to impaired Nrf2 activity | [77] |

| in vivo | Nonhealing skin ulcers | i.p. injection | - | Nrf2−/− C57BL/6 mice Perilesional skin tissue samples from diabetic patients | Increasing proliferation and migration, decreasing apoptosis Upregulation of TGF-β1 and downregulation of MMP9 | [78] |

| in vitro | Endothelial dysfunction | - | - | Primary human coronary arterial endothelial cells (CAECs) | Impaired angiogenic processes (including proliferation, adhesion, migration and ability to form capillary-like structures) | [79] |

| in vivo | Chronic venous insufficiency-related wound injury | i.p. injection | RTA 408 (Omaveloxolone) | C57BL/6 mice | Expression of antioxidant mediators | [80] |

| in vivo | Bed wounds | s.c. injection (dorsal skin 12 mm) | ESC-Exos treatment | C57BL/6 mice skin aging model | Nrf2 activation, improved skin aging and downregulation of Keap1 by miR-200a | [81] |

| in vivo | Retina injury | intravitreally injection | MIND4-17 | BALB/C mice | Activation of Nrf2 and reduced disfunction of retina Preventing apoptosis caused by high glucose | [82] |

| in vivo | Atherosclerotic lesions | i.p. injection | tBHQ | apoE−/− mice | Increased expression of HMOX1, SOD1 and CAT Upregulation of autophagy-related genes (BECN1, SQSTM1/p2, ATG5/7) | [83] |

| in vivo | Impaired wound healing | i.p. injection | DMF | Wistar rats | Upregulation of Nqo1 and HO-1 expression Downregulation of IL1β, IL-6 and MCP1 | [84] |

| in vivo | Impaired wound healing | i.p. injection (1.5 mm dorsal skin) | LPS-Exos (500 µg/mL –1 mg/mL, 21 day) | Sprague Dawley rats | Increased expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and Nqo1 genes Decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) and MMP9 | [85] |

| in vivo | Impaired wound healing | i.p. injection (8 mm dorsal skin) | PCB2 treatment (10 mg/kg daily) | C57BL/6 mice | Promoting cell survival and migration Decreased oxidative stress | [86] |

| in vitro in vivo | Cutaneous wound | i.p. injection (10 mm dorsal skin) | siKeap1 | 3T3 cells (added siRNA-liposomal complex) Leprdb/db mice | Redox homeostasis | [87] |

7. Nrf2 Induction of Cytoprotective Genes and Nrf2 Dependent Therapeutic Regimens in Wound Healing

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADSCs | adipose-derived stem cells |

| ARE | antioxidant response element |

| BTB | broad-complex, tramtrack and bric a brac |

| bZIP | basic leucine zipper |

| CAT | catalase |

| CK10 | cytokeratin 10 |

| CNC | cap ‘n’ collar |

| COX2 | cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CREBP | cAMP response element binding protein |

| Cul3 | cullin3 |

| DGR | double glycine repeat |

| DMF | dimethyl fumarate |

| EGCG | epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FGF | fibroblast growth factor |

| GCLC | glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GSR | glutathione reductase |

| GST | glutathione S-transferase |

| H2S | hydrogen sulfide |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase 1 |

| IL-10 | interleukin 10 |

| IL1β | interleukin 1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| IVR | intervening region |

| Keap1 | kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| KGF | keratinocyte growth factor |

| Maf | musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinases |

| Neh | Nrf2-ECh homology |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NQO-1 | NAD(P)H:quinone Oxidoreductase 1 |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor E2 p45-related factor 2 |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| ROS | reactive oxygene species |

| RXRα | retinoid X receptor α |

| SA | syringic acid |

| SFN | sulforaphane |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| SOD1-3 | superoxide dismutase1-3 |

| STZ | streptozotocin |

| tBHQ | tertiary butylhydroquinone |

| TF | transcription factor |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-β |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor α |

| TrCP | transducin repeat-containing protein |

| TRX | thioredoxin |

| UPS | ubiquitin proteasome system |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Ambrozova, N.; Ulrichova, J.; Galandakova, A. Models for the study of skin wound healing. The role of Nrf2 and NF-κB. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky. Olomouc. Czech. Repub. 2017, 161, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozzein, W.N.; Badr, G.; Badr, B.M.; Allam, A.; Ghamdi, A.A.; Al-Wadaan, M.A.; Al-Waili, N.S. Bee venom improves diabetic wound healing by protecting functional macrophages from apoptosis and enhancing Nrf2, Ang-1 and Tie-2 signaling. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 103, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasuya, A.; Tokura, Y. Attempts to accelerate wound healing. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 76, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; von Woedtke, T.; Vollmar, B.; Hasse, S.; Bekeschus, S. Nrf2 signaling and inflammation are key events in physical plasma-spurred wound healing. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1066–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzl, E.J.; Banda, M.J.; Leppert, D. Matrix metalloproteinases in immunity. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hunninghake, G.W.; Davidson, J.M.; Rennard, S.; Szapiel, S.; Gadek, J.E.; Crystal, R.G. Elastin fragments attract macrophage precursors to diseased sites in pulmonary emphysema. Science 1981, 212, 925–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, J.; Coodly, L.; Vollmer, P.; Kishimoto, T.K.; Rose-John, S.; Massague, J. Diverse cell surface protein ectodomains are shed by a system sensitive to metalloprotease inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 11276–11282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A. Mukaiyama, A.; Itoh, Y.; Nagase, H.; Thøgersen, I.B.; Enghild, J.; Sasaguri, Y.; Moti, Y. Degradation of interleukin 1β by matrix metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 14657–14660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, N.M.; Karran, E.H.; Turner, J. Membrane protein secretases. Biochem. J. 1997, 321, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caley, M.P.; Martins, V.L.C.; O’Toole, E.A. Metalloproteinases and Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Yang, M.; Xu, F.; Chen, J.; Ma, S. Acceleration of wound healing activity with syringic acid in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2019, 233, 116728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, P.; Werner, S. Regulation of wound healing by the NRF2 transcription factor—More than cytoprotection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzumdar, S.; Hiebert, H.; Haertel, E.; Ben-Yehuda Greenwald, M.; Bloch, W.; Werner, S.; Schäfer, M. Nrf2-mediated expansion of pilosebaceous cells accelerates cutaneous wound healing. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, I.; Köhler, Y.; Aglan, A.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Beck, K.F.; Frank, S. Increase of cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) during late wound repair: Hydrogen sulfide triggers cytokeratin 10 expression in keratinocytes. Nitric. Oxide 2019, 87, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruno, A.; Yagishita, Y.; Yamamoto, M. The Keap1-Nrf2 system and diabetes mellitus. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 566, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, D.; Portales-Casamar, E.; Singh, A.; Srivastava, S.; Arenillas, D.; Happel, C.; Shyr, C.; Wakabayashi, N.; Kensler, T.W.; Wasserman, W.W.; et al. Global mapping of binding sites for Nrf2 identifies novel targets in cell survival response through ChIP-Seq profiling and network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 5718–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, C.; Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Luo, L.; Namani, A.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo de la Vega, M.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. Nrf2 and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J. The role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress-induced endothelial injuries. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 225, R83–R99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, C.K.; Jena, G. Nrf2, a novel molecular target to reduce type 1 diabetes associated secondary complications: The basic considerations. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 843, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniades, H.N.; Galanopoulos, T.; Neville-Golden, J.; Kiritsy, C.P.; Lynch, S.E. p53 expression during normal tissue regeneration in response to acute cutaneous injury in swine. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 93, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmar, B.; El-Gibaly, A.M.; Scheuer, C.; Strik, M.W.; Bruch, H.P.; Menger, M.D. Acceleration of cutaneous wound healing by transient p53 inhibition. Lab. Investig. 2002, 82, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Krieg, T.; Davidson, J.M. Inflammation in wound repair: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.C.; Costa, T.F.; Andrade, Z.A.; Medrado, A.R. Wound healing—A literature review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, P.; Sarada, D.; Ramkumar, K.M. Pharmacological activation of Nrf2 promotes wound healing. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 886, 173395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; Cole, R.N.; Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Talalay, P. Direct evidence that sulfhydryl groups of Keap1 are the sensors regulating induction of phase 2 enzymes that protect against carcinogens and oxidants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11908–11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes. Dev. 1999, 13, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Motohashi, H. The KEAP1-NRF2 system: A thiol-based sensor-effector apparatus for maintaining redox homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Panieri, E.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. An overview of Nrf2 signaling pathway and its role in inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Hannink, M. Distinct cysteine residues in Keap1 are required for Keap1-dependent ubiquitination of Nrf2 and for stabilization of Nrf2 by chemopreventive agents and oxidative stress. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 23, 8137–8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, N.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; Kang, M.-I.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Talalay, P. Protection against electrophile and oxidant stress by induction of the phase 2 response: Fate of cysteines of the Keap1 sensor modified by inducers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2040–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.-K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Itoh, K.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W. Modulation of gene expression by cancer chemopreventive dithiolethiones through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Identification of novel gene clusters for cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 8135–8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, D.R.; Cao, S. Diabetic wound healing and activation of Nrf2 by herbal medicine. J. Nat. Sci. 2016, 2, e247. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kostov, R.V.; Canning, P. Keap1, the cysteine-based mammalian intracellular sensor for electrophiles and oxidants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 617, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Muramatsu, A.; Saito, R.; Iso, T.; Shibata, T.; Kuwata, K.; Kawaguchi, S.; Iwawaki, T.; Adachi, S.; Suda, H.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of Cellular Oxidative Stress Sensing by Keap1. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 746–758.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covas, G.; Marinho, H.S.; Cyrne, L.; Antunes, F. Activation of Nrf2 by H2O2. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-Q.; Kim, M.Y.; Godoy, L.C.; Thiantanawat, A.; Trudel, L.J.; Wogan, G.N. Nitric oxide activation of Keap1/Nrf2 signaling in human colon carcinoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14547–14551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; McDonald, P.; Liu, J.; Klaassen, C. Screening of natural compounds as activators of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Planta Med. 2014 80, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Muri, J.; Wolleb, H.; Broz, P.; Carreira, E.M.; Kopf, M. Electrophilic Nrf2 activators and itaconate inhibit inflammation at low dose and promote IL-1β production and inflammatory apoptosis at high dose. Redox. Biol. 2020, 36, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, C.A.; Fassett, R.G.; Coombes, J.S. Sulforaphane and other nutrigenomic nrf2 activators: Can the clinician’s expectation be matched by the reality? Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers Heerspink, H.J.; Fioretto, P.; de Zeeuw, D. Pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and treatment of diabetic nephropathy. In National Kidney Foundation Primer on Kidney Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, H.D.; Gassmann, M.G.; Munz, B.; Steiling, H.; Engelhardt, F.; Bleuel, K.; Werner, S. Expression and function of keratinocyte growth factor and activin in skin morphogenesis and cutaneous wound repair. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2000, 5, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S.; Hanselmann, C.; Gassmann, M.G.; auf dem Keller, U.; Born-Berclaz, C.; Chan, K.; Kan, Y.W.; Werner, S. Nrf2 transcription factor, a novel target of keratinocyte growth factor action which regulates gene expression and inflammation in the healing skin wound. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 22, 5492–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pan, L.; Xu, R.; Si, L.; Zhang, X. The molecular mechanism of Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in the antioxidant defense response induced by BaP in the scallop Chlamys farreri. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wruck, C.J.; Götz, M.E.; Herdegen, T.; Varoga, D.; Brandenburg, L.-O.; Pufe, T. Kavalactones protect neural cells against amyloid β peptide-induced neurotoxicity via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-dependent nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 73, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Islas, C.A.; Maldonado, P.D. Canonical and non-canonical mechanisms of Nrf2 activation. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.; Redmann, M.; Rajasekaran, N.S.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Zhang, J. KEAP1–NRF2 signalling and autophagy in protection against oxidative and reductive proteotoxicity. Biochem. J. 2015, 469, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolini, D.; Dallaglio, K.; Torquato, P.; Piroddi, M.; Galli, F. Nrf2-p62 autophagy pathway and its response to oxidative stress in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl. Res. 2018, 193, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Wang, X.-J.; Zhao, F.; Villeneuve, N.F.; Wu, T.; Jiang, T.; Sun, Z.; White, E.; Zhang, D.D. A noncanonical mechanism of nrf2 activation by autophagy deficiency: Direct interaction between Keap1 and p62. MCB 2010, 30, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimura, Y.; Waguri, S.; Sou, Y.; Kageyama, S.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishimura, R.; Saito, T.; Yang, Y.; Kouno, T.; Fukutomi, T.; et al. Phosphorylation of p62 Activates the Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway during Selective Autophagy. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Simmons, A.N.; Kajino-Sakamoto, R.; Tsuji, Y.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J. TAK1 Regulates the Nrf2 Antioxidant System Through Modulating p62/SQSTM1. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016, 25, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, Y.; Wruck, C.J.; Fragoulis, A.; Drescher, W.; Pape, H.C.; Lichte, P.; Fischer, H.; Tohidnezhad, M.; Hildebrand, F.; Pufe, T.; et al. Role of Nrf2 in fracture healing: Clinical aspects of oxidative stress. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2019, 105, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano Sanchez, M.; Lancel, S.; Boulanger, E.; Neviere, R. Targeting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the treatment of impaired wound healing: A systematic review. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Bekeschus, S. Redox for repair: Cold physical plasmas and Nrf2 signaling promoting wound healing. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippross, S.; Beckmann, R.; Streubesand, N.; Ayub, F.; Tohidnezhad, M.; Campbell, G.; Kan, Y.W.; Horst, F.; Sönmez, T.T.; Varoga, D.; et al. Nrf2 deficiency impairs fracture healing in mice. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2014, 95, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-X.; Li, L.; Corry, K.A.; Zhang, P.; Yang, Y.; Himes, E.; Mihuti, C.L.; Nelson, C.; Dai, G.; Li, J. Deletion of Nrf2 reduces skeletal mechanical properties and decreases load-driven bone formation. Bone 2015, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Olsen, B.R. The roles of vascular endothelial growth factor in bone repair and regeneration. Bone 2016, 91, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweider, N.; Fragoulis, A.; Rosen, C.; Pecks, U.; Rath, W.; Pufe, T.; Wruck, C.J. Interplay between vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2): Implications for preeclampsia. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 42863–42872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou-Siafis, S.K.; Tsiftsoglou, A.S. Activation of KEAP1/NRF2 stress signaling involved in the molecular basis of hemin-induced cytotoxicity in human pro-erythroid K562 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 175, 113900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panich, U.; Sittithumcharee, G.; Rathviboon, N.; Jirawatnotai, S. Ultraviolet radiation-induced skin aging: The role of DNA damage and oxidative stress in epidermal stem cell damage mediated skin aging. Stem. Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 7370642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M.; Dutsch, S.; auf dem Keller, U.; Navid, F.; Schwarz, A.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A.; Werner, S. Nrf2 establishes a glutathione-mediated gradient of UVB cytoprotection in the epidermis. Genes. Dev. 2010, 24, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Fu, J.; Pi, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y. Nrf2 in keratinocytes protects against skin fibrosis via regulating epidermal lesion and inflammatory response. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 174, 113846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, P.S.; Ellison, T.; Waqas, B.; Sultan, D.; Abdou, S.; David, J.A.; Cohen, J.M.; Gomez-Viso, A.; Lam, G.; Kim, C.; et al. Targeted Nrf2 activation therapy with RTA 408 enhances regenerative capacity of diabetic wounds. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 139, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, R.; Himori, N.; Taguchi, K.; Ishikawa, Y.; Uesugi, K.; Ito, M.; Duncan, T.; Tsujikawa, M.; Nakazawa, T.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. The role of the Nrf2-mediated defense system in corneal epithelial wound healing. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuk, S.M.; Abrahamse, H.; Houreld, N.N. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Diabetic Wound Healing in relation to Photobiomodulation. J Diabetes Res. 2016, 2897656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahara, T.; Murohara, T.; Sullivan, A.; Silver, M.; van der Zee, R.; Li, T.; Witzenbichler, B.; Schatteman, G.; Isner, J.M. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 1997, 275, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetaki, A.; Kirton, J.P.; Xu, Q. Vascular repair by endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 78, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- António, N.; Fernandes, R.; Soares, A.; Soares, F.; Lopes, A.; Carvalheiro, T.; Paiva, A.; Pêgo, G.M.; Providência, L.A.; Gonçalves, L.; et al. Reduced levels of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: Accompanying the glycemic continuum. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 1012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, S.; Masuda, H.; Jung, S.Y.; Yun, J.; Kang, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Park, J.H.; Ji, S.T.; Kwon, S.M.; Asahara, T. Impaired development and dysfunction of endothelial progenitor cells in type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab. 2017, 43, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadini, G.P.; Sartore, S.; Schiavon, M.; Albiero, M.; Baesso, I.; Cabrelle, A.; Agostini, C.; Avogaro, A. Diabetes impairs progenitor cell mobilisation after hindlimb ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 3075–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.A.; Lien, I.Z.; Mead, L.E.; Estes, M.; Prater, D.N.; Derr-Yellin, E.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Haneline, L.S. In vitro hyperglycemia or a diabetic intrauterine environment reduces neonatal endothelial colony-forming cell numbers and function. Diabetes 2008, 57, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Liu, L.H.; Liu, H.; Wu, K.F.; An, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Bai, L.J.; Qi, B.M.; Qi, B.L.; et al. Nrf2 protects against diabetic dysfunction of endothelial progenitor cells via regulating cell senescence. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 1327–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florczyk, U.; Jazwa, A.; Maleszewska, M.; Mendel, M.; Szade, K.; Kozakowska, M.; Grochot-Przeczek, A.; Viscardi, M.; Czauderna, S.; Bukowska-Strakova, K.; et al. Nrf2 regulates angiogenesis: Effect on endothelial cells, bone marrow-derived proangiogenic cells and hind limb ischemia. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1693–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresta, C.G.; Fidilio, A.; Caruso, G.; Caraci, F.; Giblin, F.J.; Leggio, G.M.; Salomone, S.; Drago, F.; Bucolo, C. A New Human Blood-Retinal Barrier Model Based on Endothelial Cells, Pericytes, and Astrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal-Ponce, A.; Tiruneh, M.W.; Lee, J.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Kuhn, J.; David, J.A.; Dammeyer, K.; Mc Kell, R.; Kwong, J.; Rabbani, P.S.; et al. Keratinocyte-Macrophage Crosstalk by the Nrf2/Ccl2/EGF Signaling Axis Orchestrates Tissue Repair. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.; Rojo de la Vega, M.; Wen, Q.; Bharara, M.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, S.; Wong, P.K.; Wondrak, G.T.; Zheng, H.; et al. An Essential Role of NRF2 in Diabetic Wound Healing. Diabetes 2016, 65, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcarcel-Ares, M.N.; Gautam, T.; Warrington, J.P.; Bailey-Downs, L.; Sosnowska, D.; de Cabo, R.; Losonczy, G.; Sonntag, W.E.; Ungvari, Z.; Csiszar, A. Disruption of Nrf2 signaling impairs angiogenic capacity of endothelial cells: Implications for microvascular aging. J. Gerontol. Series A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, J.; Sultan, D.L.; Waqas, B.; Ellison, T.; Kwong, J.; Kim, C.; Hassan, A.; Rabbani, P.S.; Ceradini, D.J. Nrf2-activating Therapy Accelerates Wound Healing in a Model of Cutaneous Chronic Venous Insufficiency. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 8, e3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Niu, X.; Deng, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. Human embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes promote pressure ulcer healing in aged mice by rejuvenating senescent endothelial cells. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, Y.; Huang, N.; Yao, J.; Luo, W.F.; Jiang, Q. The Nrf2 activator MIND4-17 protects retinal ganglion cells from high glucose-induced oxidative injury. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 7204–7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Sun, X.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Xu, L.; Tian, A.; Sun, X.; Meng, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, W.; et al. Protective role of NRF2 in Macrovascular Complications of Diabetes. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 16, 8903–8917. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, X. Protective effects of sulforaphane on diabetic retinopathy: Activation of the Nrf2 pathway and inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome formation. Exp. Anim. 2019, 68, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wu, C.; Mao, L.; Gao, Z.; Xia, N.; Liu, C.; Mei, X. LPS-stimulated Macrophage Exosomes Inhibit Inflammation by Activating the Nrf2/HO-1 Defense Pathway and Promote Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, P.; Yang, Z.; et al. Procyanidin B2 improves endothelial progenitor cell function and promotes wound healing in diabetic mice via activating Nrf2. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.A.; Cohen, O.D.; Low, Y.C.; Sartor, R.A.; Ellison, T.; Anil, U.; Anzai, L.; Chang, J.B.; Saadeh, P.B.; Rabbani, P.S.; et al. Restoration of Nrf2 Signaling Normalizes the Regenerative Niche. Diabetes 2016, 65, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yu, H.; Pan, H.; Zhou, X.; Ruan, Q.; Kong, D.; Chu, Z.; Li, H.; Huang, J.; Huang, X.; et al. Nrf2 suppression delays diabetic wound healing through sustained oxidative stress and inflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.R.; Gao, Z.H.; Qu, X.J. Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway and natural products for cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010, 34, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Bai, Y.; Miao, X.; Luo, P.; Chen, Q.; Tan, Y.; Rane, M.J.; Miao, L.; Cai, L. Prevention of diabetic nephropathy by sulforaphane: Possible role of Nrf2 upregulation and activation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magesh, S.; Chen, Y.; Hu, L. Small molecule modulators of Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway as potential preventive and therapeutic agents: Small molecule modulators of Keap1-Nrf2-are pathway. Med. Res. Rev. 2012, 32, 687–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, I.; Lopez-Sanz, L.; Bernal, S.; Oguiza, A.; Recio, C.; Melgar, A.; Jimenez-Castilla, L.; Egido, J.; Madrigal-Matute, J.; Gomez-Guerrero, C. Nrf2 Activation provides atheroprotection in diabetic mice through concerted upregulation of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and autophagy mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, M.; Aras, A.B.; Topaloğlu, N.; Özkan, A.; Şen, H.M.; Kalkan, Y.; Okuyucu, A.; Akbal, A.; Gökmen, F.; Coşar, M. The protective effect of syringic acid on ischemia injury in rat brain. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 45, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xie, X.; Lian, W.; Shi, R.; Han, S.; Zhang, H.; Lu, L.; Li, M. Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells overexpressing Nrf2 accelerate cutaneous wound healing by promoting vascularization in a diabetic foot ulcer rat model. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, J.; Chang, X.; Wang, J.; Luo, M.; Wintergerst, K.A.; Miao, L.; Cai, L. Genetic variants of nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2 associated with the complications in Han descents with type 2 diabetes mellitus of Northeast China. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 2078–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Dang, M.; Lin, Y.; Xue, F. Evaluation of wound healing activity of plumbagin in diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2019, 231, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chou, H.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Cui, Z. Wound healing activity of neferine in experimental diabetic rats through the inhibition of inflammatory cytokines and nrf-2 pathway. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2020, 48, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, P.S.; Zhou, A.; Borab, Z.M.; Frezzo, J.A.; Srivastava, N.; More, H.T.; Rifkin, W.J.; David, J.A.; Berens, S.J.; Chen, R.; et al. Novel lipoproteoplex delivers Keap1 siRNA based gene therapy to accelerate diabetic wound healing. Biomaterials 2017, 132, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, M.; Willrodt, A.; Kurinna, S.; Link, A.S.; Farwanah, H.; Geusau, A.; Gruber, F.; Sorg, O.; Huebner, A.J.; Roop, D.R.; et al. Activation of Nrf2 in keratinocytes causes chloracne (MADISH)-like skin disease in mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namani, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Modulation of NRF2 signaling pathway by nuclear receptors: Implications for cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 2014, 1843, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, F.; Li, H.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, H. Dimethyl fumarate accelerates wound healing under diabetic condition. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 61, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Cai, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Guo, S.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. DPP-4 Inhibitors improve diabetic wound healing via direct and indirect promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and reduction of scarring. Diabetes 2018, 67, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, G.; Takahara, M.; Uchi, H.; Matsuda, T.; Chiba, T.; Takeuchi, S.; Yasukawa, F.; Moroi, Y.; Furue, M. Identification of ketoconazole as an AhR-Nrf2 activator in cultured human keratinocytes: The basis of its anti-inflammatory effect. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Li, M.; Chen, W.; Yu, H.; Yang, Y.; Hang, L. Apigenin Attenuates Oxidative Injury in ARPE-19 Cells thorough Activation of Nrf2 Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 4378461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidlin, C.J.; Rojo de la Vega, M.; Perer, J.; Zhang, D.D.; Wondrak, G.T. Activation of NRF2 by topical apocarotenoid treatment mitigates radiation-induced dermatitis. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buommino, E.; D’Abrosca, B.; Donnarumma, G.; Parisi, A.; Scognamiglio, M.; Fiorentino, A.; De Luca, A. Evaluation of the antioxidant properties of carexanes in AGS cells transfected with the Helicobacter pylori’s protein HspB. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 108, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresti, R.; Bucolo, C.; Platania, C.M.; Drago, F.; Dubois-Randé, J.L.; Motterlini, R. Nrf2 activators modulate oxidative stress responses and bioenergetic profiles of human retinal epithelial cells cultured in normal or high glucose conditions. Pharmacol Res. Commun. 2015, 99, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, E.; Hoque, M.; Gong, P.; Killeen, E.; Green, C.J.; Foresti, R.; Alam, J.; Motterlini, R. Curcumin activates the haem oxygenase-1 gene via regulation of Nrf2 and the antioxidant-responsive element. J. Biochem. 2003, 371, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lu, S.; Dong, X.; Xu, L.; Sun, G.; Sun, X. Dihydromyricetin protects human umbilical vein endothelial cells from injury through ERK and Akt mediated Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Apoptosis 2017, 22, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Hsu, M.C.; Hsieh, C.W.; Lin, J.B.; Lai, P.H.; Wung, B.S. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 by Epigallocatechin-3-gallate via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and ERK pathways. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 2889–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiu, C.; Liu, W.; Tao, Y.; Wang, J.; Qu, Y.I. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract protects the retina against early diabetic injury by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 11, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Feng, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wertz, K.; Weber, P.; Fu, Y.; Liu, J. Stimulation of GSH synthesis to prevent oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by hydroxytyrosol in human retinal pigment epithelial cells: Activation of Nrf2 and JNK-p62/SQSTM1 pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Pan, H.; Chang, R.C.; So, K.F.; Brecha, N.C.; Pu, M. Activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway contributes to the protective effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides in the rodent retina after ischemia-reperfusion-induced damage. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Ma, X.; Cui, Y.; Song, Y.; Yao, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, S. Methyleugenol protects against t-BHP-triggered oxidative injury by induction of Nrf2 dependent on AMPK/GSK3β and ERK activation. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 135, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanuel, F.S.; Saguie, B.O.; Monte-Alto-Costa, A. Olive oil promotes wound healing of mice pressure injuries through NOS-2 and Nrf2. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, Z.; Bagi, Z.; Feher, A.; Recchia, F.A.; Sonntag, W.E.; Pearson, K.; de Cabo, R.; Csiszar, A. Resveratrol confers endothelial protection via activation of the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2. American journal of physiology. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H18–H24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Yang, W.; Xue, Q.; Gao, L.; Huo, J.; Ren, D.; Chen, X. Rutin ameliorates diabetic neuropathy by lowering plasma glucose and decreasing oxidative stress via Nrf2 signaling pathway in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 771, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Jia, H.; Sun, L.; Tian, C.; Jia, L.; Liu, J. α-Tocopherol is an effective Phase II enzyme inducer: Protective effects on acrolein-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyninck, K.; Sabbe, L.; Chirumamilla, C.S.; Szarc Vel Szic, K.; Vander Veken, P.; Lemmens, K.; Lahtela-Kakkonen, M.; Naulaerts, S.; Op de Beeck, K.; Laukens, K.; et al. Withaferin A induces heme oxygenase (HO-1) expression in endothelial cells via activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 109, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gegotek, A.; Skrzydlewska, E. The role of transcription factor Nrf2 in skin cells metabolism. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2015, 307, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, V.; Gopal, A.; Pathak, N.N.; Kumar, P.; Tandan, S.K.; Kumar, D. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of curcumin accelerated the cutaneous wound healing in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 20, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, R.; Xiang, C.; Jia, Q.; Wu, H.; Yang, H. Huangbai liniment accelerated wound healing by activating Nrf2 signaling in diabetes. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 4951820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Xiang, C.; Cao, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J. Berberine accelerated wound healing by restoring TrxR1/JNK in diabetes. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2021, 135, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound/Extract/Material | Injury | Model | Studied on | Site of Action | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apigenin | Age-related macular degeneration | in vitro | Human retinal epithelial cell line (ARPE-19) | Antioxidant properties depending on Nrf2 activation Upregulation of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, T-AOC Downregulation of ROS | [104] |

| Apocarotenoid (bixin) | Radiation-induced dermatitis | in vivo | SHK1 mice (Dorsal skin exposed to UV radiation) | Prevention of DNA damage and oxidative stress | [105] |

| Bee venom | - | in vivo | BALB/c mice | Enhanced wound by increasing collagen and BD-2 expression Enhanced Ang-1/Tie-2 downstream signaling | [2] |

| Catexanes | Oxidative stress | in vitro | Human gastric epithelial cells (AGS) | Reduced Keap-1 expression and induced NQO1 expression | [106] |

| Topical application of carnosol | Corneal epithelial injury | in vivo | Sprague-Dawley rats | Oxidative stress responses | [107] |

| Curcumin | - | in vitro | Porcine renal epithelial proximal tubule cells (LLC-PK1) and rat kidney epithelial cells (NRK-52E) | Increased HO-1 protein expression and heme oxygenase activity Activation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway Phosphorylation by p38 MAPK | [108] |

| Dihydromyricetin | Vascular endothelial cell injury | in vitro | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) | Activation of the Akt and ERK1/2 pathways | [109] |

| EGCG | Oxidative stress | in vitro | Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) | Upregulation of HO-1 Activation of Akt and ERK1/2 signaling | [110] |

| Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract | Diabetic retinal function | in vivo | Wistar rats | Increased SOD and GSH-Px activity levels | [111] |

| Hydroxytyrosol | - | in vitro | Human retinal pigment epithelial cells (ARPE-19) | Overexpression of Nrf2 and increased GSH content Activation of the PI3/Akt and mTOR/p70S6-kinase pathways Upregulation of p62/autophagy | [112] |

| Lycium barbarum polysaccharides | Retina injury | in vivo | i.p. injection of ZnPP | Accumulation of Nrf2 and HO-1 expression | [113] |

| Methyleugenol | Oxidative stress | in vitro | Murine macrophage cells (RAW 264.7 and J774A.1) | Activation of the AMPK/GSK3β and ERK-Nrf2 signaling pathways | [114] |

| Olive oil-based diet | IR injury | in vivo | External application of magnet disks (dorsal skin) | Decreased COX-2 and increased NO synthase-2, Nrf2 and collagen type 1 protein expression | [115] |

| Resveratrol | Endothelial dysfunction | in vitro | Primary human coronary arterial endothelial cells (CAECs) | Upregulation of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1, γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, and HO-1 | [116] |

| Rutin | Diabetic neuropathy | in vivo | Sprague–Dawley rats | Decreased caspase-3 expression increased hydrogen sulfide (H2S) level | [117] |

| α-Tocopherol | Retina injury | in vitro | Human retinal pigment epithelial cells (ARPE-19) | Activation of Keap1/Nrf2 signaling Expression of HO-1, GST, SOD enzymes | [118] |

| Withaferin A | - | in vitro | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and endothelial cell line (EA.hy926) | Increased expression of HO-1 Direct interaction with Keap1 | [119] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Süntar, I.; Çetinkaya, S.; Panieri, E.; Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. Regulatory Role of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Wound Healing Process. Molecules 2021, 26, 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092424

Süntar I, Çetinkaya S, Panieri E, Saha S, Buttari B, Profumo E, Saso L. Regulatory Role of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Wound Healing Process. Molecules. 2021; 26(9):2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092424

Chicago/Turabian StyleSüntar, Ipek, Sümeyra Çetinkaya, Emiliano Panieri, Sarmistha Saha, Brigitta Buttari, Elisabetta Profumo, and Luciano Saso. 2021. "Regulatory Role of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Wound Healing Process" Molecules 26, no. 9: 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092424

APA StyleSüntar, I., Çetinkaya, S., Panieri, E., Saha, S., Buttari, B., Profumo, E., & Saso, L. (2021). Regulatory Role of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Wound Healing Process. Molecules, 26(9), 2424. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092424