Ammoides pusilla Essential Oil: A Potent Inhibitor of the Growth of Fusarium avenaceum and Its Enniatin Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

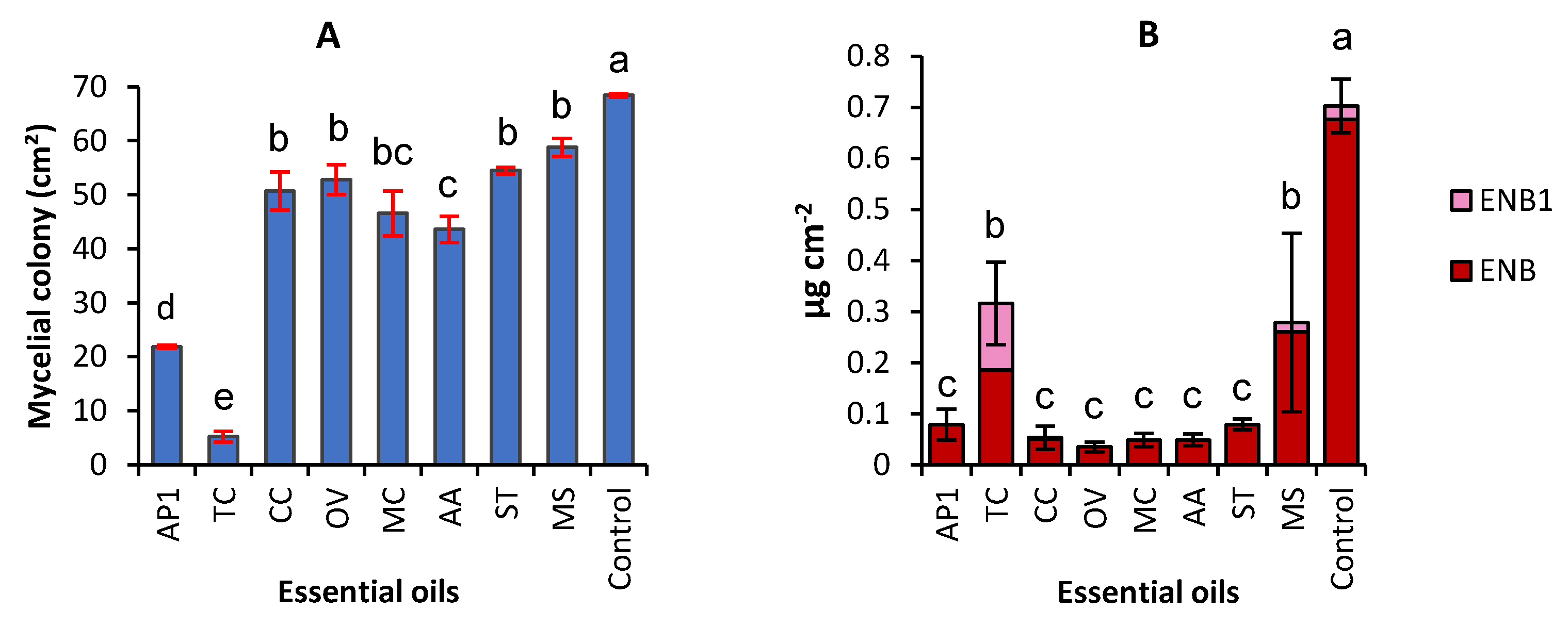

2.1. Effect of Eight EOs on Mycelial Growth and Production of Enniatins by F. avenaceum

2.2. Chemical Composition of A. pusilla EO

2.3. Effect of A. pusilla EOs on Mycelial Growth and Production of Enniatins by F. avenaceum

2.3.1. In Vitro Contact Assays in Agar Media

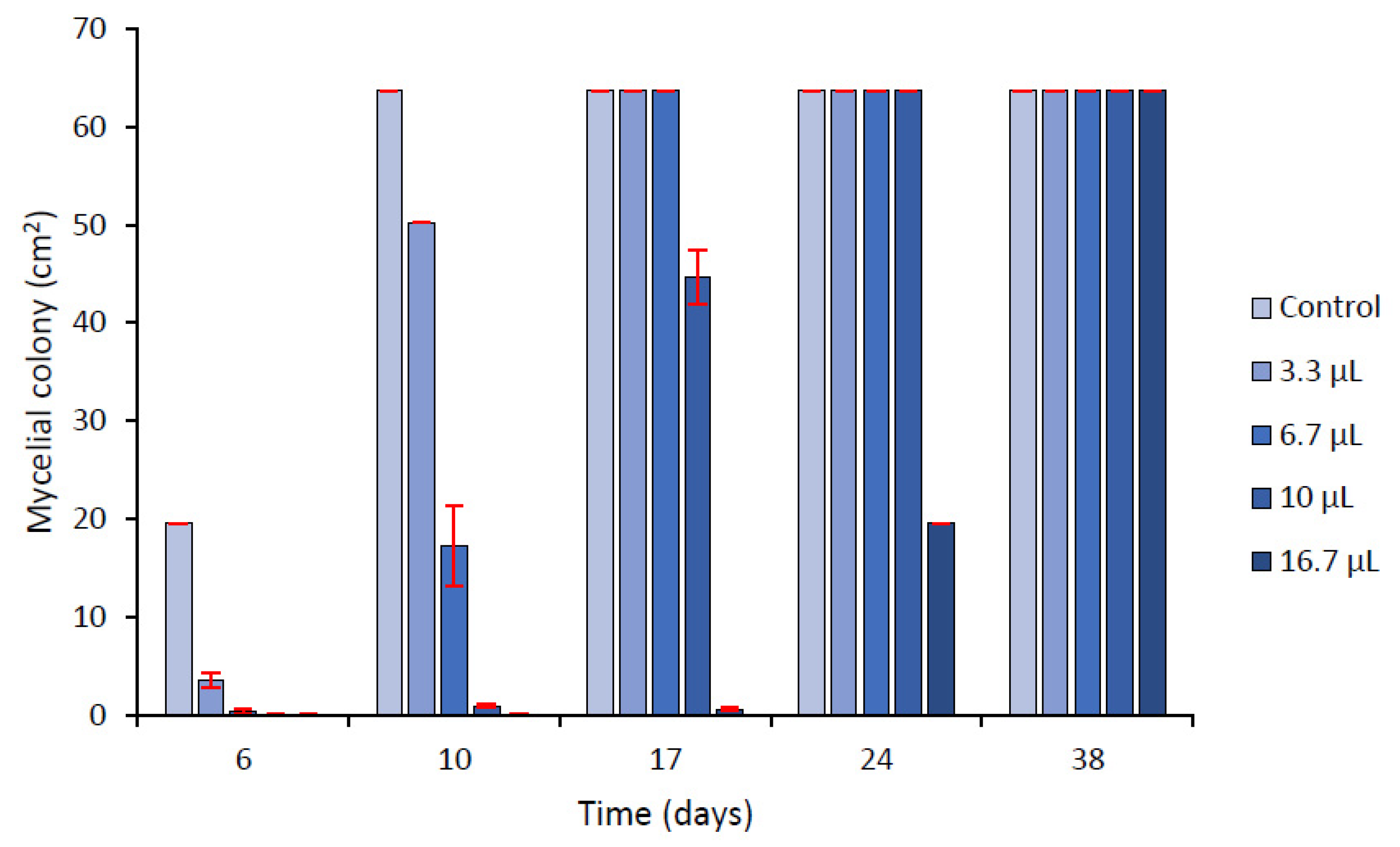

2.3.2. Effect of Volatiles Components

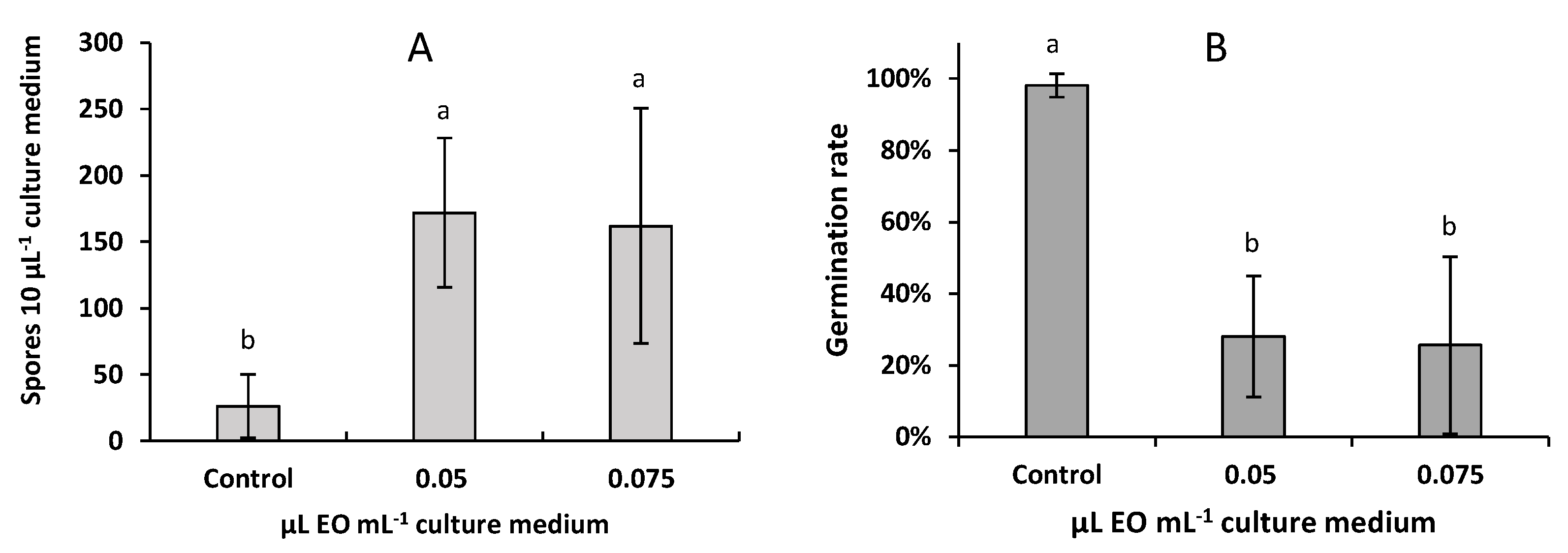

2.4. Effect of A. pusilla EO on the Sporulation and Spore Germination of F. avenaceum

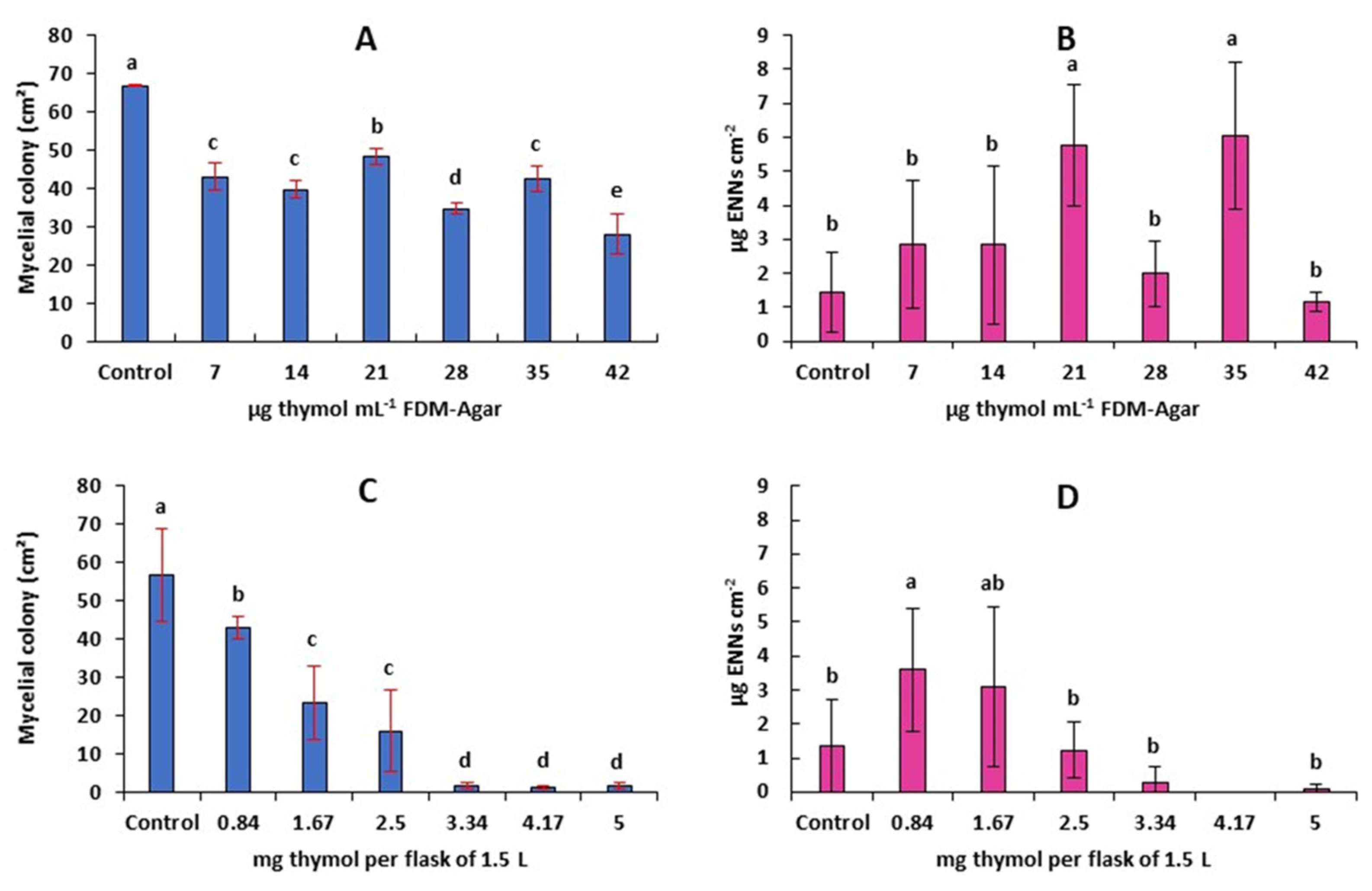

2.5. Antifungal and Antimycotoxigenic Activity of Thymol on F. avenaceum

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and EOs

4.2. Fusarium Strain and Media

4.3. Agar Dilution Assays

4.3.1. Comparison of Eight EOs

4.3.2. Activity of A. pusilla EO on F. avenaceum in Contact Assay

4.4. Effect of Volatile Compounds of A. pusilla EO on F. avenaceum

4.5. Effect A. pusilla EO on Production and Germination of Conidia by F. avenaceum

4.6. Effect of Thymol on F. avenaceum

4.7. Chemical Composition of A. pusilla EO

4.8. Extraction and Quantification of Enniatins

4.9. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Medina, A.; Akbar, A.; Baazeem, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Magan, N. Climate change, food security and mycotoxins: Do we know enough? Fungal Biol. Rev. 2017, 31, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Liang, J.; Yang, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Liang, Z.; Li, F.; Zeng, Q.; Fang, Z.; Liao, B.; et al. Plant diversity enhances the reclamation of degraded lands by stimulating plant–soil feedbacks. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.I.; Taniwaki, M.H.; Cole, M.B. Mycotoxin production in major crops as influenced by growing, harvesting, storage and processing, with emphasis on the achievement of food safety objectives. Food Control 2013, 32, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, S.; Berrada, H.; Juan-García, A.; Mañes, J.; Juan, C. Multiple mycotoxin determination on Tunisian cereals-based food and evaluation of the population exposure. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.W.; Klich, M. Mycotoxins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jestoi, M. Emerging Fusarium-mycotoxins fusaproliferin, beauvericin, enniatins, and moniliformin—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, S.; Ramos, A.J.; Cano-Sancho, G.; Sanchis, V. Mycotoxins: Occurrence, toxicology, and exposure assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Food and Feed. CXS193-1995 Amended in 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/list-standards/en/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- European Commission. European Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006. Setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 364, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cheli, F.; Battaglia, D.; Gallo, R.; Dell’Orto, V. EU legislation on cereal safety: An update with a focus on mycotoxins. Food Control 2014, 37, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, C.; Pinson-Gadais, L.; Richard-Forget, F. Fusarium mycotoxins enniatins. An updated review of their occurrence, the producing fusarium species, and the abiotic determinants of their accumulation in crop harvests. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 4788–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Updating techniques on controlling mycotoxins—A review. Food Control. 2018, 89, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuenzel, K.M.; Harrison, M.A. Microbial antagonists of foodborne pathogens on fresh, minimally processed vegetables. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, B.; Kedia, A.; Mishra, P.K.; Dubey, N.K. Plant essential oils as food preservatives to control moulds, mycotoxin contamination and oxidative deterioration of agri-food commodities—Potentials and challenges. Food Control 2015, 47, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, L.; Agindotan, B.O.; Burrows, M.E. Antifungal activity of plant-derived essential oils on pathogens of pulse crops. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paškevičius, A.; Švedienė, J.; Levinskaitė, L.; Repečkienė, J.; Raudonienė, V.; Melvydas, V. The effect of bacteria and essential oils on mycotoxin producers isolated from feed of plant origin. Vet. Med. Zoot. 2014, 65, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Gu, H.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L. Improved method to obtain essential oil, asarinin and sesamin from Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum using microwave-assisted steam distillation followed by solvent extraction and antifungal activity of essential oil against Fusarium spp. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 162, 113295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyśko-Łupicka, T.; Sokół, S.; Piekarska-Stachowiak, A. Evaluation of fungistatic activity of eight selected essential oils on four heterogeneous fusarium isolates obtained from cereal grains in southern Poland. Molecules 2020, 25, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraternale, D.; Ricci, D.; Epifano, F.; Curini, M. Composition and antifungal activity of two essential oils of hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis L.). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2004, 16, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi-Moses, O.B.; Ogidi, C.O.; Akinyele, B.J. Bioactivity of Citrus essential oils (CEOs) against microorganisms associated with spoilage of some fruits. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2019, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanana, M.; Mansour, M.B.; Algabr, M.; Amri, I.; Gargouri, S.; Romane, A.; Jamoussi, B.; Hamrouni, L. Potential use of essential oils from four Tunisian species of Liliaceae: Biological alternative for fungal and weed control. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2017, 11, 258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mughrabi, K.I.; Coleman, W.K.; Vikram, A.; Poirier, R.; Jayasuriya, K.E. Effectiveness of essential oils and their combinations with aluminum starch octenyl succinate on potato storage pathogens. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2013, 16, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkirui, C.; Matasyoh, J.C.; Wagara, I.N.; Nakuvuma, J. Antifungal activity of Monathotaxis littoralis essential oil against mycotoxigenic fungi isolated from maize. Int. J. Microbiol. Res. Rev. 2013, 2, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bounar, R.; Krimat, S.; Boureghda, H.; Dob, T. Chemical analyses, antioxidant and antifungal effects of oregano and thyme essential oils alone or in combination against selected Fusarium species. Int. Food Res. J. 2020, 27, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrouni, L.; Hanana, M.; Amri, I.; Romane, A.E.; Gargouri, S.; Jamoussi, B. Allelopathic effects of essential oils of Pinus halepensis Miller: Chemical composition and study of their antifungal and herbicidal activities. Arch. Phytopath. Plant Protec. 2015, 48, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, I.; Gargouri, S.; Hamrouni, L.; Hanana, M.; Fezzani, T.; Jamoussi, B. Chemical composition, phytotoxic and antifungal activities of Pinus pinea essential oil. J. Pest Sci. 2012, 85, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matasyoh, J.C.; Wagara, I.N.; Nakavuma, J.L.; Chepkorir, R. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of Piper capense oil against mycotoxigenic Aspergillus, Fusarium and Penicillium species. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2013, 7, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Lamia, H.; Mohsen, H.; Samia, G.; Bassem, J. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of three Anacardiaceae species grown in Tunisia. Sci. Int. 2013, 1, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saoud, I.; Hamrouni, L.; Gargouri, S.; Amri, I.; Hanana, M.; Fezzan, T.; Bouzid, S.; Jamoussi, B. Chemical composition, weed killer and antifungal activities of Tunisian thyme (Thymus capitatus Hoff. et Link.) essential oils. Acta Aliment. 2013, 42, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamperi, L.; Bucchini, A.E.A.; Ricci, D.; Tirillini, B.; Nicoletti, M.; Rakotosaona, R.; Maggi, F. Vepris macrophylla (Baker) I. Verd essential oil: An antifungal agent against phytopathogenic fungi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu-Ingok, A.; Devecioglu, D.; Dikmetas, D.N.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Capanoglu, E. Antibacterial, antifungal, antimycotoxigenic, and antioxidant activities of essential oils: An updated review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponts, N. Mycotoxins are a component of Fusarium graminearum stress-response system. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.F.; Bresso, E.; Togowa, R.C.; Urban, M.; Antoniw, J.; Maigret, B.; Hammond-Kosack, K. Searching for novel targets to control wheat Head Blight Disease-I-Protein identification, 3D modelling and virtual screening. Adv. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutigny, A.L.; Barreau, C.; Atanasova-Penichon, V.; Verdal-Bonnin, M.N.; Pinson-Gadais, L.; Richard-Forget, F. Ferulic acid, an efficient inhibitor of type B trichothecene biosynthesis and Tri gene expression in Fusarium liquid cultures. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponts, N.; Pinsons-Gadais, L.; Boutigny, A.L.; Barreau, C.; Richard-Forget, F. Cinnamic-derived acids significantly affect Fusarium graminearum growth and in vitro synthesis of type B trichothecenes. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrochio, L.; Cendoya, E.; Farnochi, M.C.; Massad, W.; Ramírez, M.L. Evaluation of ability of ferulic acid to control growth and fumonisin production of Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium proliferatum on maize based media. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perczak, A.; Gwiazdowsk, D.; Gwiazdowsk, R.; Juś, K.; Marchwińska, K.; Waśkiewicz, A. The inhibitory potential of selected essential oils on Fusarium spp. growth and mycotoxins biosynthesis in maize seeds. Pathogens 2020, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefiani, C.; Riazi, A.; Youcefi, F.; Aazza, S.; Gago, C.; Faleiro, M.L.; Megías, C.; Cortés-Giraldo, I.; Vioque, J.; Miguel, M.G. Ammoides pusilla (Apiaceae) and Thymus munbyanus (Lamiaceae) from Algeria essential oils: Chemical composition, antimicrobial, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2015, 27, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefiani, C.; Riazi, A.; Belbachir, B.; Lahmar, H.; Aazza, S.; Figueiredo, A.C.; Miguel, M.G. Ammoides pusilla (Brot.) Breistr. from Algeria: Effect of harvesting place and plant part (leaves and flowers) on the essential oils chemical composition and antioxidant activity. Open Chem. 2016, 14, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souhaiel, N.; Sifaoui, I.; Ben Hassine, D.; Bleton, J.; Bonose, M.; Moussa, F.; Piñero, J.E.; Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Abderrabba, M. Ammoides pusilla (Apiaceae) essential oil: Activity against Acanthamoeba castellanii Neff. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 183, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcia, C.; Malnati, M.; Terzi, V. In Vitro antifungal activity of terpinen-4-ol, eugenol, carvone, 1, 8-cineole (eucalyptol) and thymol against mycotoxigenic plant pathogens. Food Add. Contam. Part A 2012, 29, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lambert, R.J.W.; Skandamis, P.N.; Coote, P.J.; Nychas, G.J.E. A study of the minimum inhibitory concentration and mode of action of oregano essential oil, thymol and carvacrol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, W.; Hu, L.; Chen, J.; Shi, Z. The fungicidal activity of thymol against Fusarium graminearum via inducing lipid peroxidation and disrupting ergosterol biosynthesis. Molecules 2016, 21, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ge, J.; Yu, X. Transcriptome analysis reveals the mechanism of fungicidal of thymol against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum. Cur. Microbiol. 2018, 75, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakova, L.; Mikityuk, O.; Arslanova, L.; Stakheev, A.; Erokhin, D.; Zavrie, S.; Dzhavakhiya, V. Studying the ability of thymol to improve fungicidal effects of tebuconazole and difenoconazole against some plant pathogenic fungi in seed or foliar treatments. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Kim, H.; Beuchat, L.R.; Ryu, J.H. Synergistic antimicrobial activities of essential oil vapours against Penicillium corylophilum on a laboratory medium and beef jerky. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 29, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambolena, J.S.; López, A.G.; Meriles, J.M.; Rubinstein, H.R.; Zygadlo, J.A. Inhibitory effect of 10 natural phenolic compounds on Fusarium verticillioides. A structure–property–activity relationship study. Food Control. 2012, 28, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukhouia, M.; Hamdani, H.; Jabeur, I.; Sennouni, C.; Remmal, A. In Vitro study of anti-Fusarium effect of thymol, carvacrol, eugenol and menthol. J. Plant. Pathol. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1000423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, C.; Stintzing, F.C. Stability of essential oils: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, D.M.; Kazan, K.; Praud, S.; Torney, F.J.; Rusu, A.; Manners, J.M. Early activation of wheat polyamine biosynthesis during Fusarium head blight implicates putrescine as an inducer of trichothecene mycotoxin production. BMC Plant. Biol. 2010, 10, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, C.; Pinson-Gadais, L.; Verdal-Bonnin, M.N.; Ducos, C.; Tremblay, J.; Chéreau, S.; Atanasova, V.; Richard-Forget, F. Investigating the efficiency of hydroxycinnamic acids to inhibit the production of enniatins by Fusarium avenaceum and modulate the expression of enniatins biosynthetic genes. Toxins 2020, 12, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeribi, C.; Karoui, I.J.; Hassine, D.B.; Abderrabba, M. Comparative study of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of Schinus terebinthifolius RADDI fruits and leaves essential oils. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, F.; Ferracane, R.; Ritieni, A.; Logrieco, A.F.; Mulè, G. Transcriptional regulation of enniatins production by Fusarium avenaceum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyśko-Łupicka, T.; Walkowiak, W.; Białoń, M. Comparison of the fungistatic activity of selected essential oils relative to Fusarium graminearum isolates. Molecules 2019, 24, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Plants | Origin | Extraction Yield | Major Components ** | Methods *** | Inhibition of Growth | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abies sibirica | Com. */Lithuania | - | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO, (27 °C, 5 d) | 11 mm diameter | [17] |

| Asarum heterotropoides | Roots and rhizomes/China | 1.6% | Methyleugenol (38.7–43.8%), Safrol (12.9–15.3%) | BD, (26 °C, 72 h) | MIC50 = 0.61 mg·mL−1 | [18] |

| Carum carvi | Com./Lithuania | - | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO, (26 °C, 72 h) | 89 mm diameter | [17] |

| Cinnanom | Com./Pakistan | - | Eugenol (75.5%) | AD, (20 °C, 10 d) | MIC = 0.5 µL·mL−1 | [16] |

| Cinnanom | Com./Pakistan | - | Eugenol (75.5%) | Volatiles, 10 µL EO, Agar medium, (20 °C, 6 d) | 84% Inhibition | [16] |

| Citronella | Com./Pakistan | - | Geraniol (53.6%) | AD, (20 °C, 10 d) | MIC = 0.5 µL·mL−1 | [16] |

| Citronella | Com./Pakistan | - | Geraniol (53.6%) | Volatiles, 10 µL EO, Agar medium, (20 °C, 6 d) | 84% Inhibition | [16] |

| Citrus paradis Grapefruit | Com./Germany | - | Linalyl acetate (1.87%), α-Terpineol (1.83%), Nootkatone (1.37%) | AD, 2% EO, (25 °C, until control covered plates) | 12% Inhibition | [19] |

| Clove | Com./Pakistan | - | Eugenol (80.9%) | AD, (20 °C, 10 d) | MIC = 0.5 µL·mL−1 | [16] |

| Clove | Com./Pakistan | - | Eugenol (80.9%) | Volatiles, 10 µL EO, Agar medium, (20 °C, 6 d) | 86% Inhibition | [16] |

| Cymbopogon citratus (Lemongrass) | Com./Germany | - | α and β-Citral (68.9%) | AD, 2% EO, (25 °C, until control covered plates) | MIC = 0.12 µL·mL−1 | [19] |

| Eucalyptus globus | Com./Lithuania | - | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO, (27 °C, 5 d) | 28 mm diameter | [17] |

| Hyssopus officinalis | Fresh flowering tops/Italy | 2.3 mL·kg−1 | Pinocamphone (34%), β-Pinene (10.5%), α-phellandrene (7.4%) | AD, (22 °C, 7 d) | MIC = 1.5 mg·mL−1 | [20] |

| Hyssopus officinalis | Fresh flowering tops/Italy | 3.1 mL·kg−1 | Isopinocamphone (29%), Pinocamphone (18.5%), β-Pinene (10.8%) | AD, (22 °C, 7 d) | MIC = 1.2 mg·mL−1 | [20] |

| Lavandula hybrida | Com./Lithuania | - | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO, (27 °C, 5 d) | 12 mm diameter | [17] |

| Lemon | Citrus rind/Nigeria | - | α-Terpineol (31.2%), l-Limonene (14.4%), β-Pinene (12.4%) | AWD, (25 °C, 48 h) | MIC = 100 mg·mL−1 | [21] |

| Lime | Citrus rind/Nigeria | - | d-Limonene (27.8%), β-Pinene (25.2%), | AWD, (25 °C, 48 h) | MIC = 100 mg·mL−1 | [21] |

| Lemongrass | Com./Pakistan | - | Geranial (40.8%) | AD, (20 °C, 10 d) | MIC = 0.5 µL·mL−1 | [16] |

| Lemongrass | Com./Pakistan | - | Geranial (40.8%) | Volatiles, 10 µL EO, Agar medium, (20 °C, 6 d) | 84% Inhibition | [16] |

| Luppia javanica | Com./USA | - | α and β-Citral (36.0%), α-Terpineol (18.3%) | AD, 2% EO, (25 °C, until control covered plates) | MIC = 0.12 µL·mL−1 | [19] |

| Litsea cubeba | Com./Germany | - | α and β-Citral (68.9%) | AD, 2% EO, (25 °C, until control covered plates) | MIC = 0.12 µL·mL−1 | [19] |

| Melaleuca alternifolia | Com./Germany | - | α-Terpineol (6.88%), Cadinene (3.86%), β-Gurjunene (1.23%) | AD, 2% EO, (25 °C, until control covered plates) | MIC = 0.5 µL·mL−1 | [19] |

| Melaleuca alternifolia | Com./Lithuania | - | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO, (27 °C, 5 d | 22 mm diameter | [17] |

| Melaleuca leucadendron | Com./Germany | - | α-Terpineol (36.57%), Caryophyllene (2.60%), α-Caryophyllene (1.70%) | AD, 2% EO, (25 °C, until control covered plates,) | MIC = 0.1 µL·mL−1 | [19] |

| Mentha pulegium | Fresh aerial parts/Tunisia | 1.84% | Menthol (39.2%), 1,8-Cineole (17.1%), | AD, 0.5 mg EO mL−1, (24 °C, 7 d) | 32.5% Inhibition | [22] |

| Mentha spicata | Com./USA | - | - | AWD, 100 µL pure EO, (18 °C, 7 d) | 100% Inhibition | [23] |

| Monathotaxis littoralis | Fresh leaves/Uganda | 1.97% | - | APD, 10 µL EO, (25 °C, 7–10 d): | MIC = 103 mg·mL−1 | [24] |

| Oregano | Dried leaves/Algeria | - | Carvacrol (59.03%) | AD, (25 °C, 72 h) | MIC = 0.078 µL·mL−1 | [25] |

| Oregano | Com./Pakistan | - | Carvacrol (63.8%) | AD, (20 °C, 10 d) | MIC = 0.125–0.25 µL·mL−1 | [16] |

| Oregano | Com./Pakistan | - | Carvacrol (63.8%) | Volatiles, 10 µL EO, Agar medium, (20 °C, 6 d) | 100% Inhibition | [16] |

| Origanum vulgare | Air-dried leaves, 21 accessions/Lithuania | - | Sabinene (0.3–25.1%), β-Caryophyllene (4.7–20.1%), Germacrene D (2.1–20.1%), Caryophyllene oxide (0.7–24.4%) | AWD, 100 µL 0.5% EO, (18 °C, 7 d) | 3.8–19.5 mm diameter | [25] |

| Origanum vulgare | Air-dried inflorescences, 21 accessions/Lithuania | - | Sabinene (0.9–18.3%), β-Caryophyllene (5.4–24.5%), Germacrene D (1.5–12.2%), Caryophyllene oxide (0.7–24.4%) | AWD, 100 µL 0.5% EO, (18 °C, 7 d) | 9.9–22 mm diameter | [25] |

| Origanum vulgare | Fresh aerial parts/Tunisia | 0.90% | Thymol (29.6%), p-Cymene (29.4%) | AD, 0.5 mg EO mL−1, (24 °C, 7 d) | 77.4% Inhibition | [22] |

| Palmarosa | Com./Pakistan | - | Geraniol (72.26%) | AD, (20 °C, 10 d) | MIC = 1.0 µL·mL−1 | [16] |

| Palmarosa | Com./Pakistan | - | Geraniol (72.26%) | Volatiles, 10 µL EO, Agar medium (20 °C, 6 d) | 87% Inhibition | [16] |

| Pimpinella anisum | Com./Lithuania | - | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO, (27 °C, 5 d) | 30 mm diameter | [17] |

| Pinus halepensis | Fresh needles/Tunisia | 0.30–0.87% | (Z)-Caryophyllene (16–28.9%), β-Myrcene (8.5–22.9%), α-Pinene (11.7–13.14%) | AD, 4 µL EO mL−1, (25 °C, 7 d) | 41.9–51.8% Inhibition | [26] |

| Pinus pinea | Fresh needles/Tunisia | 0.40% | Limonene (54.1%), | AD, 4 µL EO mL−1, (25 °C, 7 d) | 61.1% Inhibition | [27] |

| Piper capense | Fresh whole plant/Kenya | 0.20% | δ-Cadinene (16.82), β-Pinene (7.24%), β-Bisabolene (5.65%), | APD, 10 µL EO, (25 °C, 7–10 d) | MIC = 66.3 mg·mL−1 | [28] |

| Pistacia lentiscus | Fresh leaves/Tunisia | 0.14% | α-Pinene (20.6%), Limonene (15.3%), β-Pinene (9.6%) | AD, 4 µL EO mL−1 (25 °C, 7 d) | 44.4% Inhibition | [29] |

| Pistacia terebintus | Fresh leaves/Tunisia | 0.24% | α-Terpinene (41.3%), α-Pinene (19.2%) | AD, 4 µL EO mL−1, (25 °C, 7 d) | 68.0% Inhibition | [29] |

| Pistacia vera | Fresh leaves/Tunisia | 0.27% | α-Terpinene (32.4%), Limonene (25.1%) | AD, 4 µL EO mL−1, (25 °C, 7 d) | 63.2% Inhibition | [29] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis | Fresh aerial parts/Tunisia | 0.60% | 1,8-Cineole (40.9%),α-Pinene (24.2%), | AD, 0.5 mg EO mL−1, (25 °C, 7 d) | 21.8% Inhibition | [22] |

| Syzygium aromaticum | Com./Lithuania | - | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO (27 °C, 5 d) | 90 mm diameter | [17] |

| Thyme | Dried leaves/Algeria | 0.85% | Thymol (46.97%), Linalool (3.94%) | AD, (25 °C, 72 h) | MIC = 0.156 µL·mL−1 | [25] |

| Thyme | Com./Pakistan | - | Linalool (64.0%) | AD, (20 °C, 10 d) | MIC = 0.5 µL·mL−1 | [16] |

| Thyme | Com./Pakistan | - | Linalool (64.0%) | Volatiles, 10 µL EO, Agar medium (20 °C, 6 d) | 100% Inhibition | [16] |

| Thymus capitatus | Fresh aerial parts/Tunisia | 2.85% | Carvacrol (69.15%) | AD, 0.5 mg EO mL−1, (24 °C, 7 d) | 89.9% Inhibition | [22] |

| Thymus capitatus | Fresh aerial parts/Tunisia | 1.9 to 3.15% | Carvacrol (69.69 to 83.86%) | AD, 0.4 µL EO mL−1, (25 °C, 7 d) | 4 to 93% Inhibition | [30] |

| Thymus pilegioides | Com./Lithuania | - | APD, 10 µL pure EO, (27 °C, 5 d) | 33 mm diameter | [17] | |

| Thymus vulgaris | Com. Austria | - | Thymol (45.75%), Limonene (15.15%), | AD, 2% EO, (25 °C, until control covered plates) | MIC = 0.025 µL·mL−1 | [19] |

| Vepris macrophylla | Leaves/Madagascar | - | Citral (56.3%) | AD, (22 °C, 6 d) | MIC = 130.4 µg·mL−1 | [31] |

| Plant | EO Extraction Yield (%) |

|---|---|

| Ammoides pusilla (AP2) | 1.64 |

| Thymus capitatus (TC) | 2.45 |

| Carum carvi (CC) | 1.57 |

| Origanum vulgare (OV) | 0.46 |

| Myrtus communis (MC) | 0.45 |

| Artemisia absintum (AA) | 0.96 |

| Schinus terbentofonius (ST) | 2.50 |

| Mentha spicata (MS) | 1.10 |

| Compounds | RT 1 | % in AP1 | % in AP2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | |||

| α-thujene | 5.69 | 0.37% | 0.24% |

| α-pinene | 5.86 | 0.21% | 0.36% |

| Sabinene | 6.76 | 0.57% | ---- |

| β-myrcene | 7.12 | 0.48% | 0.30% |

| α-terpinene | 7.80 | ---- | 0.19% |

| p-Cymene | 8.00 | 19.89% | 14.59% |

| α-thujene | 5.69 | 0.37% | 0.24% |

| γ-terpinene | 8.89 | 27.03% | 16.82% |

| o-Allyltoluene | 9.72 | 0.25% | ---- |

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | |||

| Borneol | 11.86 | 0.18% | ---- |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 12.17 | 0.67% | 0.58% |

| Thymol methyl ether | 13.56 | 9.18% | 8.07% |

| Benzene, 2-methoxy-4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl) | 13.69 | 0.73% | 0.52% |

| Thymol (isomere) | 15.08 | 1.70% | 2.88% |

| Thymol | 15.26 | 34.70% | 53.55% |

| NI | 15.36 | 0.25% | 0.29% |

| Carvacrol | 15.59 | 0.41% | 0.68% |

| 2-(t-butyl)-5,6-dihydro-4H-cyclopenta[b]thiophene | 17.74 | 0.61% | 0.53% |

| 1-Methoxy-2-tert-butyl-6-methylbenzene | 18.87 | 2.48% | 0.20% |

| Identified compounds | 97.27% | 99.51% | |

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 48.83% | 32.70% | |

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 47.82% | 66.58% | |

| Extraction yield | 1.6% | 1.64% |

| Concentrations of Essential Oil (mL·L−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Control) | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | |

| Linear growth index | 16.22 | 10.65 | 3.34 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| µg enniatins/cm2 mycelium | 2.06 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| µL EO L−1 Air | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (control) | 3.3 | 6.7 | 10 | 16.7 | |

| Linear growth index | 16.02 | 15.68 | 12.11 | 10.10 | 2.97 |

| % growth inhibition at 10 d | 0 | 21.97 | 72.83 | 98.40 | 100 |

| µg ENNs cm−2 mycelium (10 d) | 1.34 | 0.44 | 0.26 | <LOQ * | <LOQ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakroun, Y.; Oueslati, S.; Atanasova, V.; Richard-Forget, F.; Abderrabba, M.; Savoie, J.-M. Ammoides pusilla Essential Oil: A Potent Inhibitor of the Growth of Fusarium avenaceum and Its Enniatin Production. Molecules 2021, 26, 6906. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226906

Chakroun Y, Oueslati S, Atanasova V, Richard-Forget F, Abderrabba M, Savoie J-M. Ammoides pusilla Essential Oil: A Potent Inhibitor of the Growth of Fusarium avenaceum and Its Enniatin Production. Molecules. 2021; 26(22):6906. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226906

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakroun, Yasmine, Souheib Oueslati, Vessela Atanasova, Florence Richard-Forget, Manef Abderrabba, and Jean-Michel Savoie. 2021. "Ammoides pusilla Essential Oil: A Potent Inhibitor of the Growth of Fusarium avenaceum and Its Enniatin Production" Molecules 26, no. 22: 6906. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226906

APA StyleChakroun, Y., Oueslati, S., Atanasova, V., Richard-Forget, F., Abderrabba, M., & Savoie, J.-M. (2021). Ammoides pusilla Essential Oil: A Potent Inhibitor of the Growth of Fusarium avenaceum and Its Enniatin Production. Molecules, 26(22), 6906. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226906