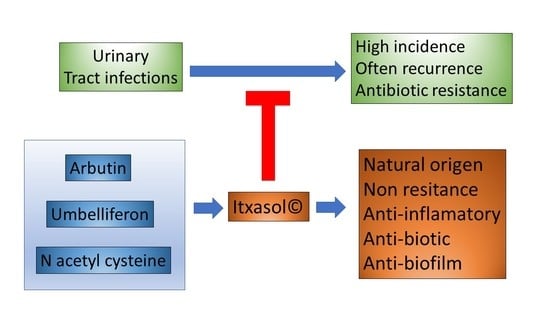

A Natural Alternative Treatment for Urinary Tract Infections: Itxasol©, the Importance of the Formulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

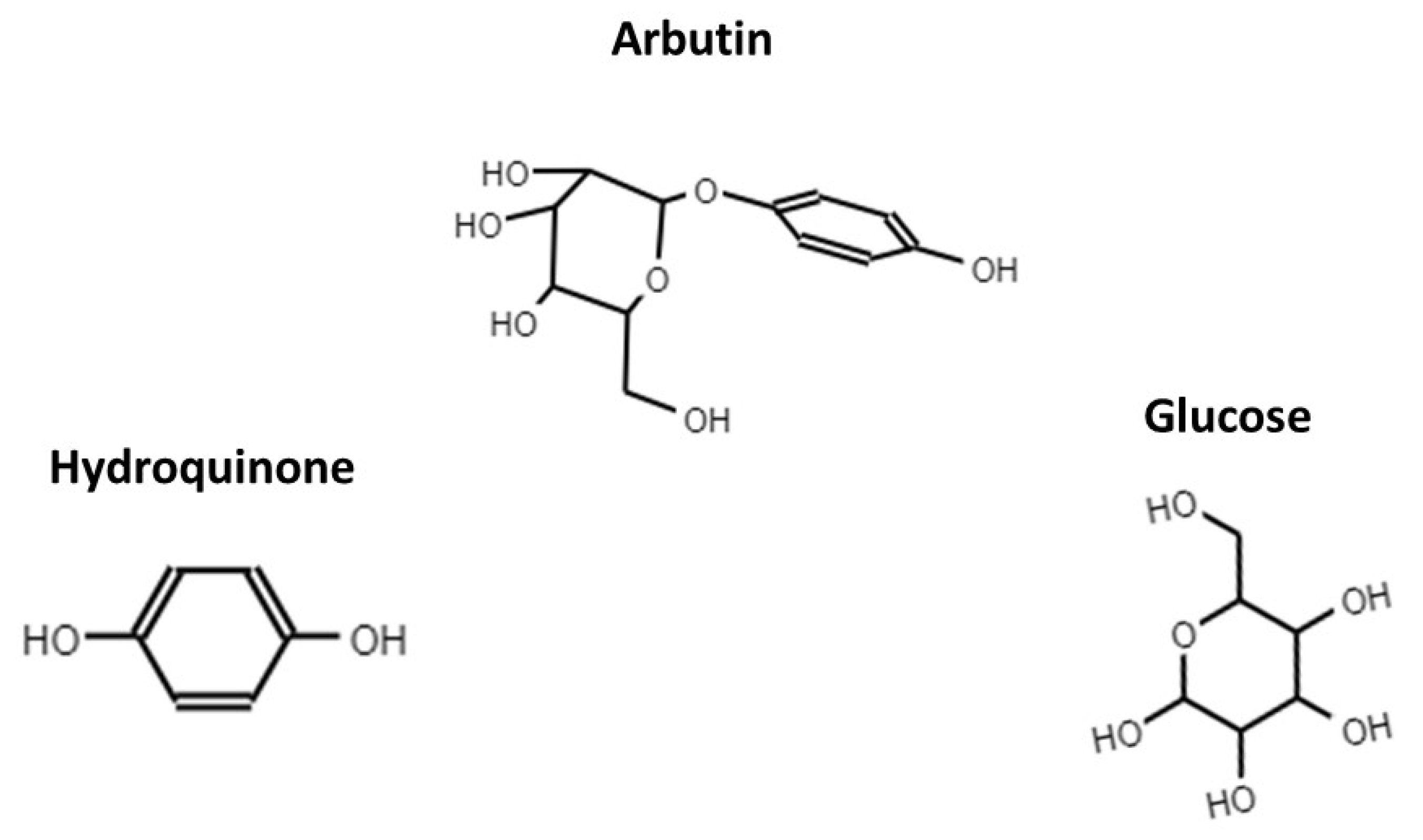

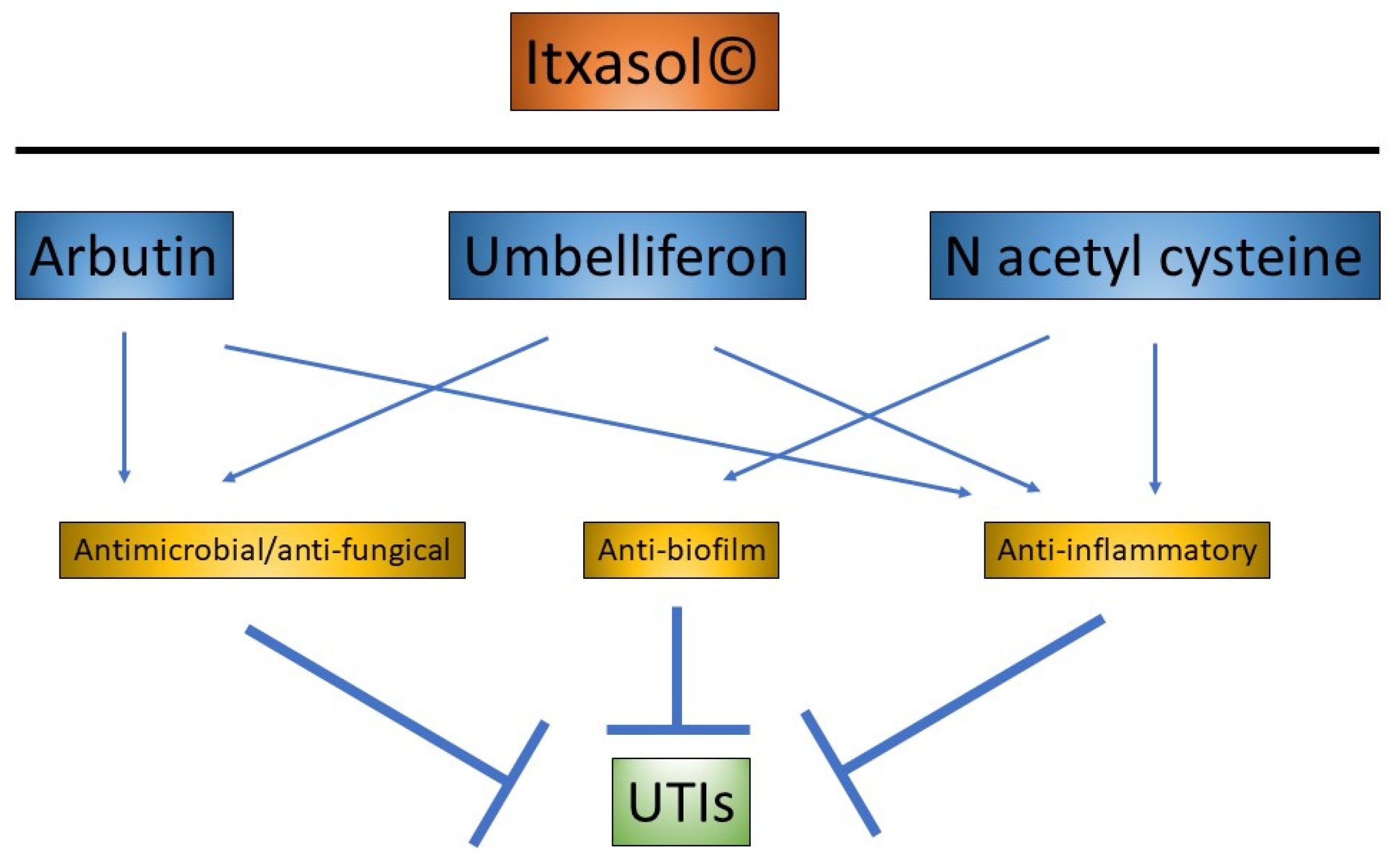

2.1. β-arbutin

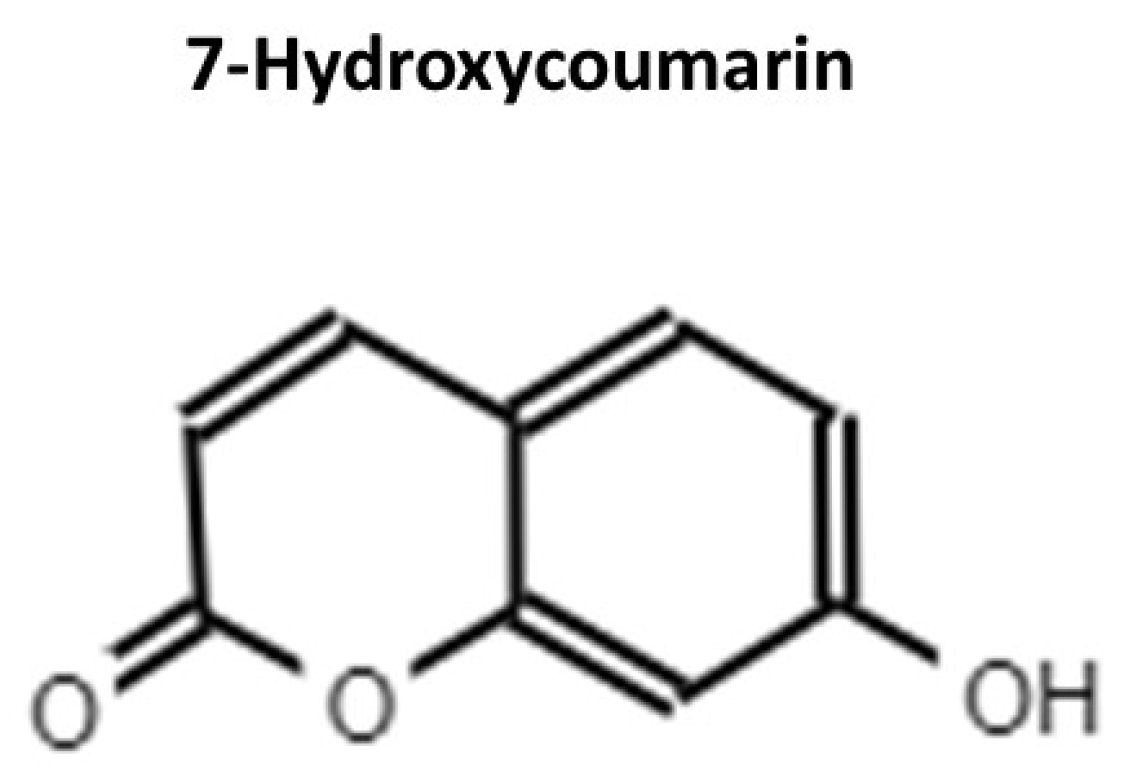

2.2. Umbelliferon (UMB)

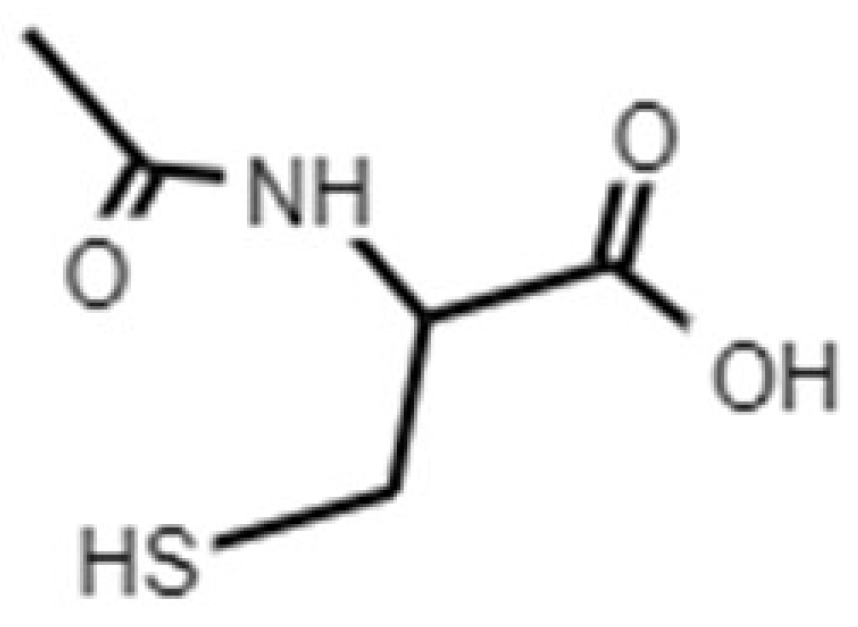

2.3. N-Acetyl L-Cysteine (NAC)

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| UTIs | urinary tract infections |

| UMB | umbelliferon |

| NAC | N-acetyl L-cysteine |

| TMP-SMX | trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

References

- Garud, M.S.; Kulkarni, Y.A. Attenuation of renal damage in type I diabetic rats by umbelliferone—A coumarin derivative. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 69, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandaglia, G.; Varda, B.; Sood, A.; Pucheril, D.; Konijeti, R.; Sammon, J.D.; Sukumar, S.; Menon, M.; Sun, M.; Chang, S.L.; et al. Short-term perioperative outcomes of patients treated with radical cystectomy for bladder cancer included in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. J. Can. Urol. Assoc. 2014, 8, E681–E687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010, 7, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajkowski, K.; Broś-Konopielko, M.; Teliga-Czajkowska, J. Urinary tract infection in women. Prz. Menopauzalny 2021, 20, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geerlings, S.E. Clinical Presentations and Epidemiology of Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, X.; Huertas, I.; Pereiro, I.; Sanfélix, J.; Gosalbes, V.; Perrotta, C. Antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004, 2004, CD001209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, D. Risk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection in young women. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 182, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiyalagen, P.; Peramasamy, B.; Vasudevan, K.; Basu, M.; Cherian, J.; Sundar, B. A descriptive cross-sectional study on menstrual hygiene and perceived reproductive morbidity among adolescent girls in a union territory, India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2017, 6, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, I.; Othman, J.; Hansson, M.; Ekelund, A.C.; Svanberg, T.; Strandell, A. New types of diaphragms and cervical caps versus older types of diaphragms and different gels for contraception: A systematic review. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2020, 47, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, P.; Behzadi, E.; Pawlak-Adamska, E.A. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) or genital tract infections (GTIs)? It’s the diagnostics that count. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2019, 14, Doc14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Brubaker, L. The etiology and management of recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Climacteric 2019, 22, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooton, T.M.; Scholes, D.; Hughes, J.P.; Winter, C.; Roberts, P.L.; Stapleton, A.E.; Stergachis, A.; Stamm, W.E. A Prospective Study of Risk Factors for Symptomatic Urinary Tract Infection in Young Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etienne, M.; Galperine, T.; Caron, F. Urinary Tract Infections in Older Men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2191–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenis, A.T.; Lec, P.M.; Chamie, K. Bladder cancer a review. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 324, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, B. Urinary tract infection syndromes. Occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germoush, M.O.; Othman, S.I.; Al-Qaraawi, M.A.; Al-Harbi, H.M.; Hussein, O.E.; Al-Basher, G.; Alotaibi, M.F.; Elgebaly, H.A.; Sandhu, M.A.; Allam, A.A.; et al. Umbelliferone prevents oxidative stress, inflammation and hematological alterations, and modulates glutamate-nitric oxide-cGMP signaling in hyperammonemic rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 102, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, L.E.; Harding, G.K.M.; Preiksaitis, J.; Ronald, A.R. The association of urinary tract infection with sexual intercourse. J. Infect. Dis. 1982, 146, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detweiler, K.; Mayers, D.; Fletcher, S.G. Bacteruria and Urinary Tract Infections in the Elderly. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 42, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anger, J.T.; Saigal, C.S.; Wang, M.M.; Yano, E.M. Urologic Disease Burden in the United States: Veteran Users of Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare. Urology 2008, 72, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsenmeyer, T.A. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in persons with neurogenic bladders. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2018, 41, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreifi, A.; Van Horn, C.M.; Xu, W.; Cai, J.; Miranda, G.; Bhanvadia, S.; Schuckman, A.K.; Daneshmand, S.; Djaladat, H. Urinary tract infections following radical cystectomy with enhanced recovery protocol: A prospective study. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2020, 38, 75.e9–75.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, P.E.; Agarwal, N.; Biagioli, M.C.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Greenberg, R.E.; Herr, H.W.; Inman, B.A.; Kuban, D.A.; Kuzel, T.M.; Lele, S.M.; et al. Bladder cancer: Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2013, 11, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigemura, K.; Tanaka, K.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakano, Y.; Shirakawa, T.; Miyata, M.; Yamashita, M.; Arakawa, S.; Fujisawa, M. Post-operative infection and prophylactic antibiotic administration after radical cystectomy with orthotopic neobladderurinary diversion. J. Infect. Chemother. 2012, 18, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griebling, T.L. Urologic diseases in America project: Trends in resource use for urinary tract infections in women. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C.L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: Causes and threats. Pharm. Ther. J. 2015, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kakoullis, L.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Chra, P.; Panos, G. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in important gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens and novel antibiotic solutions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Alvarez, M.C. Nephrotoxicity of Antimicrobials and Antibiotics. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020, 27, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A.E.; Norton, J.P.; Spivak, A.M.; Mulvey, M.A. Urinary tract infections: Current and emerging management strategies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, T.A.; Pantin, S.A.L.; Yenior, A.L.; Pujalte, G.G.A. Urinary Tract Infection Antibiotic Resistance in the United States. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2018, 45, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, B.; Gillespie, B.; Koopman, J.; Zhang, L.; Palin, K.; Tallman, P.; Marsh, J.V.; Spear, S.; Sobel, J.D.; Marty, M.J.; et al. Risk factors for second urinary tract infection among college women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salo, J.; Uhari, M.; Helminen, M.; Korppi, M.; Nieminen, T.; Pokka, T.; Kontiokari, T. Cranberry juice for the prevention of recurrences of urinary tract infections in children: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Hooton, T.M.; Naber, K.G.; Wullt, B.; Colgan, R.; Miller, L.G.; Moran, G.J.; Nicolle, L.E.; Raz, R.; Schaeffer, A.J.; et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e103–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrucha-Dilanchian, P.; Hooton, T.M. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Urinary Tract Infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunston, M.A.; Yonovitz, A.; Woodahl, E.L.; Smolensky, M.H. Gentamicin-induced ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity vary with circadian time of treatment and entail separate mechanisms. Chronobiol. Int. 2015, 32, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitout, J.D.D. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: A combination of virulence with antibiotic resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi Karam, M.R.; Habibi, M.; Bouzari, S. Urinary tract infection: Pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance and development of effective vaccines against Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 108, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.M.; Kichenadasse, G.; Karapetis, C.S.; Rowland, A.; Sorich, M.J. Concomitant Antibiotic Use and Survival in Urothelial Carcinoma Treated with Atezolizumab. Eur. Urol. 2020, 78, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberberg, M.D.; Shorr, A.F.; Micek, S.T.; Vazquez-Guillamet, C.; Kollef, M.H. Multi-drug resistance, inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy and mortality in Gram-negative severe sepsis and septic shock: A retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teillant, A.; Gandra, S.; Barter, D.; Morgan, D.J.; Laxminarayan, R. Potential burden of antibiotic resistance on surgery and cancer chemotherapy antibiotic prophylaxis in the USA: A literature review and modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, N.; Zheng, Y.; Opoku-Temeng, C.; Du, Y.; Bonsu, E.; Sintim, H.O. Biofilm formation mechanisms and targets for developing antibiofilm agents. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.W.; Mah, T.F. Molecular mechanisms of biofilm-based antibiotic resistance and tolerance in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Fatima, S.W.; Kumar, S.; Sinha, R.; Khare, S.K. Antimicrobial resistance in biofilms: Exploring marine actinobacteria as a potential source of antibiotics and biofilm inhibitors. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atriwal, T.; Azeem, K.; Husain, F.M.; Hussain, A.; Khan, M.N.; Alajmi, M.F.; Abid, M. Mechanistic Understanding of Candida albicans Biofilm Formation and Approaches for Its Inhibition. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shi, H.; Yu, H.; Yan, S.; Luan, S. The recent advances in surface antibacterial strategies for biomedical catheters. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 4074–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cal, P.M.S.D.; Matos, M.J.; Bernardes, G.J.L. Trends in therapeutic drug conjugates for bacterial diseases: A patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Panda, S.S.; Birs, A.S.; Serrano, J.C.; Gonzalez, C.F.; Alamry, K.A.; Katritzky, A.R. Synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of amino acid-antibiotic conjugates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 1856–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.M.; da Silva, B.N.M.; Barbosa, G.; Barreiro, E.J. β-lactam antibiotics: An overview from a medicinal chemistry perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 208, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piddock, L.J.V. The crisis of no new antibiotics-what is the way forward? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Chattopadhyay, M.K.; Grossart, H.P. The multifaceted roles of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, J.F.V.; Bogatyreva, O.A.; Bogatyrev, N.R.; Bowyer, A.; Pahl, A.K. Biomimetics: Its practice and theory. J. R. Soc. Interface 2006, 3, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sticher, O.; Soldati, F.; Lehmann, D. High-performance liquid chromatographic separation and quantitative determination of arbutin, methylarbutin, hydroquinone and hydroquinone-monomethylether in Arctostaphylos, Bergenia, Calluna and Vaccinium species (author’s transl). Planta Med. 1979, 35, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; He, N.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, D.; Wei, J.; Kang, W. Antimicrobial Mechanism of Hydroquinone. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 189, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, G.; Patzak, U.; Brinkhaus, B.; Von Nieciecki, A.; Wittig, J.; Krähmer, N.; Glöckl, I.; Veit, M. Urinary excretion and metabolism of arbutin after oral administration of Arctostaphylos uvae ursi extract as film-coated tablets and aqueous solution in healthy humans. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żbikowska, B.; Franiczek, R.; Sowa, A.; Połukord, G.; Krzyzanowska, B.; Sroka, Z. Antimicrobial and Antiradical Activity of Extracts Obtained from Leaves of Five Species of the Genus Bergenia: Identification of Antimicrobial Compounds. Microb. Drug Resist. 2017, 23, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.B.; Ling, J.M.L.; Wang, Z.T.; Cai, J.N.; Xu, G.J. Examination of coumarins, flavonoids and polysaccharopeptide for antibacterial activity. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996, 27, 1237–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Jo, S.H.; Ha, K.S.; Song, J.H.; Jang, H.D.; Kwon, Y.I. Antimicrobial activities of 1,4-benzoquinones and wheat germ extract. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyanthi, V.; Velusamy, P.; Kumar, G.V.; Kiruba, K. Effect of naturally isolated hydroquinone in disturbing the cell membrane integrity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 741 and Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 740. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rúa, J.; Fernández-Álvarez, L.; De Castro, C.; Del Valle, P.; De Arriaga, D.; García-Armesto, M.R. Antibacterial activity against foodborne Staphylococcus aureus and antioxidant capacity of various pure phenolic compounds. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2011, 8, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyoti, A.; Nam, K.-W.; Jang, W.S.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; Lee, B.-E.; Song, H.-Y. Antimycobacterial activity of methanolic plant extract of Artemisia capillaris containing ursolic acid and hydroquinone against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 22, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, C.; Davinelli, S.; Mangano, K.; Tempera, G.; Nicolosi, D.; Corsello, S.; Vergalito, F.; Tartaglia, E.; Scapagnini, G.; Di Marco, R. Effects of a new combination of plant extracts plus d-mannose for the management of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections. J. Chemother. 2018, 30, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshar, K.; Fleischmann, N.; Schmiemann, G.; Bleidorn, J.; Hummers-Pradier, E.; Friede, T.; Wegscheider, K.; Moore, M.; Gágyor, I. Reducing antibiotic use for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in general practice by treatment with uva-ursi (REGATTA)—A double-blind, randomized, controlled comparative effectiveness trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesunloye, B.A. Acute renal failure due to the herbal remedy CKLS. Am. J. Med. 2003, 115, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.K.; Shilkin, K.B.; Jeffrey, G.P. Darkroom hepatitis after exposure to hydroquinone. Lancet 1995, 345, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurica, K.; Benković, V.; Sikirić, S.; Brčić Karačonji, I.; Kopjar, N. The effects of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) water leaf extract and arbutin upon kidney function and primary DNA damage in renal cells of rats. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2354–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurica, K.; Brčić Karačonji, I.; Mikolić, A.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Benković, V.; Kopjar, N. In vitro safety assessment of the strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) water leaf extract and arbutin in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Cytotechnology 2018, 70, 1261–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zeng, M.; Li, B.; Kan, Y.; Wang, S.; Cao, B.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Feng, W. Arbutin attenuates LPS-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway. Phytomedicine 2021, 82, 153466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madić, V.; Petrović, A.; Jušković, M.; Jugović, D.; Djordjević, L.; Stojanović, G.; Vasiljević, P. Polyherbal mixture ameliorates hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and histopathological changes of pancreas, kidney and liver in a rat model of type 1 diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265, 113210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoult, J.R.S.; Payá, M. Pharmacological and biochemical actions of simple coumarins: Natural products with therapeutic potential. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996, 27, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Anwar, F.; Verma, A.; Mujeeb, M. Therapeutic effect of umbelliferon-α-D-glucopyranosyl-(2I→1II)-α-D-glucopyranoside on adjuvant-induced arthritic rats. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 3402–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Ahmed, D.; Verma, A.; Anwar, F.; Ali, M.; Mujeeb, M. Umbelliferone β-D-galactopyranoside from Aegle marmelos (L.) corr. An ethnomedicinal plant with antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic and antioxidative activity. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, L. Coumarins as potential antidiabetic agents. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Gonzalez, J.S.; Prado-Garcia, H.; Aguilar-Cazares, D.; Molina-Guarneros, J.A.; Morales-Fuentes, J.; Mandoki, J.J. Apoptosis and cell cycle disturbances induced by coumarin and 7-hydroxycoumarin on human lung carcinoma cell lines. Lung Cancer 2004, 43, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-García, V.M.; Rojas, G.; Avilés, M.; Fuentes, M.; Zepeda, G. In vitro antifungal activity of coumarin extracted from Loeselia mexicana Brand. Mycoses 2011, 54, e569–e571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, A.; Sindhu, G. Umbelliferone arrest cell cycle at G0/G1 phase and induces apoptosis in human oral carcinoma (KB) cells possibly via oxidative DNA damage. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 92, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Hanif, M.; Abbas, K.; Ramzan, M.; Rasheed, A.; Zaman, A.; Pieters, L. Studies on effects of umbelliferon derivatives against periodontal bacteria; antibiofilm, inhibition of quorum sensing and molecular docking analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 144, 104184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetha, T.K.; Pooranachithra, M.; Subramenium, G.A.; Divya, V.; Balamurugan, K.; Pandian, S.K. Umbelliferone Impedes Biofilm Formation and Virulence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis via Impairment of Initial Attachment and Intercellular Adhesion. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.F.; de Figueiredo, G.F.; Pedro, L.P.; Amorin, Y.M.; Andrade, J.T.; Passos, T.F.; Rodrigues, F.F.; Souza, I.L.A.; Gonçalves, T.P.R.; Lima, L.A.R.D.S.; et al. Umbelliferone (7-hydroxycoumarin): A non-toxic antidiarrheal and antiulcerogenic coumarin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, J.; Abreu, A.C.; Borges, A.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Selected Phytochemicals against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and Their Biofilms. Pathogens 2014, 3, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.-L.; Xu, Z.; Liu, M.-L.; Feng, L.-S.; Zhang, G.-D. Recent Developments of Coumarin Hybrids as Anti-fungal Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 3219–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Saha, A.; Saha, D. A new antifungal coumarin from Clausena excavata. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Rong, X.; Xu, K.; Chu, M. Antifungal activity of coumarin against Candida albicans is related to apoptosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Wang, J.L.; Chu, M.P.; Jia, C. Activity of coumarin against Candida albicans biofilms. J. Mycol. Med. 2019, 29, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Cho, H.S.; Ryu, S.Y.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, J. Coumarins reduce biofilm formation and the virulence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSweeney, K.R.; Gadanec, L.K.; Qaradakhi, T.; Ali, B.A.; Zulli, A.; Apostolopoulos, V. Mechanisms of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury: Pathological mechanisms, pharmacological interventions, and genetic mitigations. Cancers 2021, 13, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, E.H.M.; Ali, F.E.M.; Kozman, M.R.; Abd El-Ghafar, O.A.M. Umbelliferone attenuates gentamicin-induced renal toxicity by suppression of TLR-4/NF-κB-p65/NLRP-3 and JAK1/STAT-3 signaling pathways. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 11558–11571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Wang, S.S.; Chiufai, K.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, X.L. Umbelliferone ameliorates renal function in diabetic nephropathy rats through regulating inflammation and TLR/NF-κB pathway. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 17, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.M.; Hozayen, W.G.; Hasan, I.H.; Shaban, E.; Bin-Jumah, M. Umbelliferone Ameliorates CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats by Upregulating PPARγ and Attenuating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and TGF-β1/Smad3 Signaling. Inflammation 2019, 42, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ahmed, D.; Anwar, F.; Ali, M.; Mujeeb, M. Enhanced glycemic control, pancreas protective, antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects by umbelliferon-α-D-glucopyranosyl-(2I→1II)-α-Dglucopyranoside in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldini, G.; Altomare, A.; Baron, G.; Vistoli, G.; Carini, M.; Borsani, L.; Sergio, F. N-Acetylcysteine as an antioxidant and disulphide breaking agent: The reasons why. Free Radic. Res. 2018, 52, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardiolo, G.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. Overview on the effects of N-acetylcysteine in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2018, 23, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuni, Y.; Goldstein, S.; Dean, O.M.; Berk, M. The chemistry and biological activities of N-acetylcysteine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 4117–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, F.; Page, C.; Rossolini, G.M.; Pallecchi, L.; Matera, M.G.; Rogliani, P.; Cazzola, M. The effect of N-acetylcysteine on biofilms: Implications for the treatment of respiratory tract infections. Respir. Med. 2016, 117, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinicola, S.; De Grazia, S.; Carlomagno, C.; Pintucci, J.P. N-acetylcysteine as powerful molecule to destroy bacterial biofilms. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 2942–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Kim, J.; Wu, J.; Ahamed, A.I.; Wang, Y.; Martins-Green, M. N-Acetyl-cysteine and Mechanisms Involved in Resolution of Chronic Wound Biofilm. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 9589507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.M.; Dwamena, B.; Cronin, P.; Bernstein, S.J.; Carlos, R.C. Meta-analysis: Effectiveness of drugs for preventing contrast-induced nephropathy. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 148, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, A.; Sunay, M.M.; Karakan, T.; Özcan, S.; Hasçiçek, A.M.; Yardimci, İ.; Surer, H.; Korkmaz, M.; Hücümenoğlu, S.; Huri, E. The examination of the nephroprotective effect of montelukast sodium and N-acetylcysteine ın renal ıschemia with dimercaptosuccinic acid imaging in a placebo-controlled rat model. Acta Cir. Bras. 2020, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerini, M.; Grisoli, P.; Pane, C.; Perugini, P. Microstructured lipid carriers (MLC) based on N-acetylcysteine and chitosan preventing Pseudomonas Aeruginosa biofilm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundukad, B.; Udayakumar, G.; Grela, E.; Kaur, D.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Doyle, P.S. Weak acids as an alternative anti-microbial therapy. Biofilm 2020, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lababidi, N.; Montefusco-Pereira, C.V.; de Souza Carvalho-Wodarz, C.; Lehr, C.M.; Schneider, M. Spray-dried multidrug particles for pulmonary co-delivery of antibiotics with N-acetylcysteine and curcumin-loaded PLGA-nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 157, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, T.S.B.S.; Rosa, L.M.; Vega-Chacón, Y.; de Oliveira Mima, E.G. Fungistatic action of N-acetylcysteine on Candida albicans biofilms and its interaction with antifungal agents. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pijls, B.G.; Sanders, I.M.J.G.; Kuijper, E.J.; Nelissen, R.G.H.H. Synergy between induction heating, antibiotics, and N-acetylcysteine eradicates Staphylococcus aureus from biofilm. Int. J. Hyperth. 2020, 37, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollini, S.; Di Pilato, V.; Landini, G.; Di Maggi, T.; Cannatelli, A.; Sottotetti, S.; Cariani, L.; Aliberti, S.; Blasi, F.; Sergio, F.; et al. In vitro activity of N-acetylcysteine against Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Burkholderia cepacia complex grown in planktonic phase and biofilm. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Liu, B.; Xu, J.; Wang, Q.; Huang, L.; Ou, W.; Gu, J.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Zhuo, C.; et al. In vitro effects of N-acetylcysteine alone and combined with tigecycline on planktonic cells and biofilms of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Rivero, M.E.; Del Pozo, J.L.; Valentín, A.; de Diego, A.M.; Pemán, J.; Cantón, E. Activity of amphotericin B and anidulafungin combined with rifampicin, clarithromycin, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, N-acetylcysteine, and farnesol against Candida tropicalis biofilms. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kim, C.; Moon, J.H.; Lee, J.Y. Removal and killing of multispecies endodontic biofilms by N-acetylcysteine. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundukad, B.; Schussman, M.; Yang, K.; Seviour, T.; Yang, L.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Doyle, P.S. Mechanistic action of weak acid drugs on biofilms. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, E.R.; Conklin, K.A.; Bemis, D.A. Antibacterial effect of N-acetylcysteine on common canine otitis externa isolates. Vet. Dermatol. 2016, 27, 188-e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, H.W.; Heo, J.S.; Chang, S.W.; Lee, J.Y. Antibacterial effects of N-acetylcysteine against endodontic pathogens. J. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolle, L.E. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: Review and discussion of the IDSA guidelines. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2006, 28 (Suppl. S1), 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T. Recurrent uncomplicated urinary tract infections: Definitions and risk factors. GMS Infect. Dis. 2021, 9, Doc03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouckaert, J.; Berglund, J.; Schembri, M.; De Genst, E.; Cools, L.; Wuhrer, M.; Hung, C.S.; Pinkner, J.; Slättegård, R.; Zavialov, A.; et al. Receptor binding studies disclose a novel class of high-affinity inhibitors of the Escherichia coli FimH adhesin. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scribano, D.; Sarshar, M.; Prezioso, C.; Lucarelli, M.; Angeloni, A.; Zagaglia, C.; Palamara, A.T.; Ambrosi, C. D-Mannose treatment neither affects uropathogenic Escherichia coli properties nor induces stable fimh modifications. Molecules 2020, 25, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranjčec, B.; Papeš, D.; Altarac, S. D-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: A randomized clinical trial. World J. Urol. 2014, 32, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nunzio, C.; Bartoletti, R.; Tubaro, A.; Simonato, A.; Ficarra, V. Role of d-mannose in the prevention of recurrent uncomplicated cystitis: State of the art and future perspectives. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlizzi, M.E.; Gribaudo, G.; Maffei, M.E. UroPathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) infections: Virulence factors, bladder responses, antibiotic, and non-antibiotic antimicrobial strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Gallelli, L.; Meacci, F.; Brugnolli, A.; Prosperi, L.; Roberta, S.; Eccher, C.; Mazzoli, S.; Lanzafame, P.; Caciagli, P.; et al. The Efficacy of Umbelliferone, Arbutin, and N-Acetylcysteine to Prevent Microbial Colonization and Biofilm Development on Urinary Catheter Surface: Results from a Preliminary Study. J. Pathog. 2016, 2016, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Term | PubMed | Web of Science |

|---|---|---|

| Umbelliferon and urinary tract | 86 | 2 |

| Umbelliferon and biofilm | 9 | 1 |

| 7-Hydroxycoumarin and urinary tract | 20 | 2 |

| 7-Hydroxycoumarin and biofilm | 4 | 5 |

| Arbutin and urinary tract | 15 | 14 |

| Arbutin and biofilm | 2 | 3 |

| N-acetylcysteine and urinary tract | 807 | 54 |

| N-acetylcysteine and biofilm | 121 | 154 |

| Pathogen | MIC (μg/mL) | Gram | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 256 | Negative | [57] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 7.8 | Negative | [58] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 15.6 | Positive | [58] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 103 | Positive | [59] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | 512 | Negative | [57] |

| Bacillus cereus | 512 | Positive | [57] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 12.5 | Positive | [60] |

| Action | Main Findings/Use | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial action | Inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth at 128 mg/mL | [56] |

| Demonstration of antibacterial activity | [55] | |

| Arbutin destroys bacteria through wall cellular disruption (Gram + and Gram −) | [53] | |

| Reduction in bacterial load in prevention of UTI recurrence | [61] | |

| Clinical trial to reduce the use of antibiotics administering b-arbutin (results not yet published) | [62] | |

| Anti-inflammatory | Attenuated damage induced by lipopolysaccharide in rat | [67] |

| Anti-diabetic | Ameliorates hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and histopathological changes in pancreas, kidney and liver in a diabetes rat model | [68] |

| Pathogen | MIC (μg/mL) | Gram | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 1000 | Negative | [78] |

| Escherichia coli | 800 | negative | [79] |

| Shigella sonnei | 1000 | Negative | [78] |

| Salmonella typhimurium | 500 | Negative | [78] |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 1000 | Positive | [78] |

| Bacillus cereus | 62.5 | Positive | [78] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 200 | Positive | [79] |

| Action | Main Findings/Use | References |

|---|---|---|

| Antifungicidal/antibiotic | Antifungicidal activity | [74,82,83] |

| Decreases virulence and biofilm formation of E.coli O157:H7 | [84] | |

| Impedes biofilm formation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis | [77] | |

| Destroys periodontal bacteria and inhibits biofilm formation | [76] | |

| Antibiofilm properties (Staphylococcus epidermidis) | [77] | |

| Antitumoral | Inhibits cell growth in lung carcinoma cell lines | [73] |

| Induces cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 in human cell carcinoma | [75] | |

| Anti-inflammatory | Reduction in inflammation in a model of brain damage in rats | [17] |

| Antihyperglycemic | Anti-diabetic effect in a diabetic mouse model induced with streptozotocin | [89] |

| Nephron protection | Reduction in the nephrotoxicity associated to cisplatin use | [85] |

| UMB attenuates renal toxicity induced by gentamicin | [1,86] | |

| Enhances renal function in diabetic mouse model | [87] | |

| Antifibrotic | Ameliorates the liver fibrosis signs induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) in rats | [88] |

| Organism | NAC Concentration | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans C. parapsilosis C. guilliermondii C. tropicalis C. glabrata | 10–50 mg/mL | [96] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0.15–0.23 mg/mL | [98] |

| P. aeruginosa | 3–10 mg/mL | [99] |

| P. aeruginosa | 32 mg/mL | [100] |

| Candida albicans | 25 mg/mL | [101] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0.5 mg/mL | [102] |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 16–32 mg/mL | [103] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 16–128 mg/mL | [104] |

| Candida tropicalis | 1000 mg/mL | [105] |

| Actinomyces naeslundii, Lactobacillus salivarius, Streptococcus mutans, Enterococcus faecalis | 25–100 mg/mL | [106] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 10 mg/mL | [107] |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Pseudomonas aeruginosa Corynebacterium spp. and β-hemolytic Streptococcus spp. | 0.115–80 mg/mL | [108] |

| Actinomyces naeslundii, Lactobacillus salivarius, Streptococcus mutans, Enterococcus faecalis | 0.78–1.56 mg/mL | [109] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cela-López, J.M.; Camacho Roldán, C.J.; Gómez-Lizarraga, G.; Martínez, V. A Natural Alternative Treatment for Urinary Tract Infections: Itxasol©, the Importance of the Formulation. Molecules 2021, 26, 4564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26154564

Cela-López JM, Camacho Roldán CJ, Gómez-Lizarraga G, Martínez V. A Natural Alternative Treatment for Urinary Tract Infections: Itxasol©, the Importance of the Formulation. Molecules. 2021; 26(15):4564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26154564

Chicago/Turabian StyleCela-López, José M., Claudio J. Camacho Roldán, Gorka Gómez-Lizarraga, and Vicente Martínez. 2021. "A Natural Alternative Treatment for Urinary Tract Infections: Itxasol©, the Importance of the Formulation" Molecules 26, no. 15: 4564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26154564

APA StyleCela-López, J. M., Camacho Roldán, C. J., Gómez-Lizarraga, G., & Martínez, V. (2021). A Natural Alternative Treatment for Urinary Tract Infections: Itxasol©, the Importance of the Formulation. Molecules, 26(15), 4564. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26154564