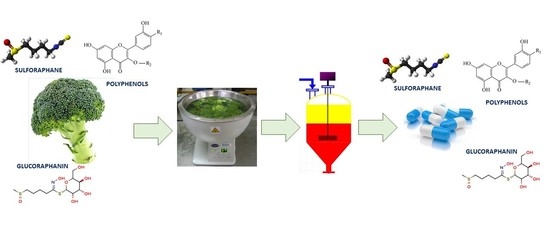

Optimization of an Extraction Process to Obtain a Food-Grade Sulforaphane-Rich Extract from Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

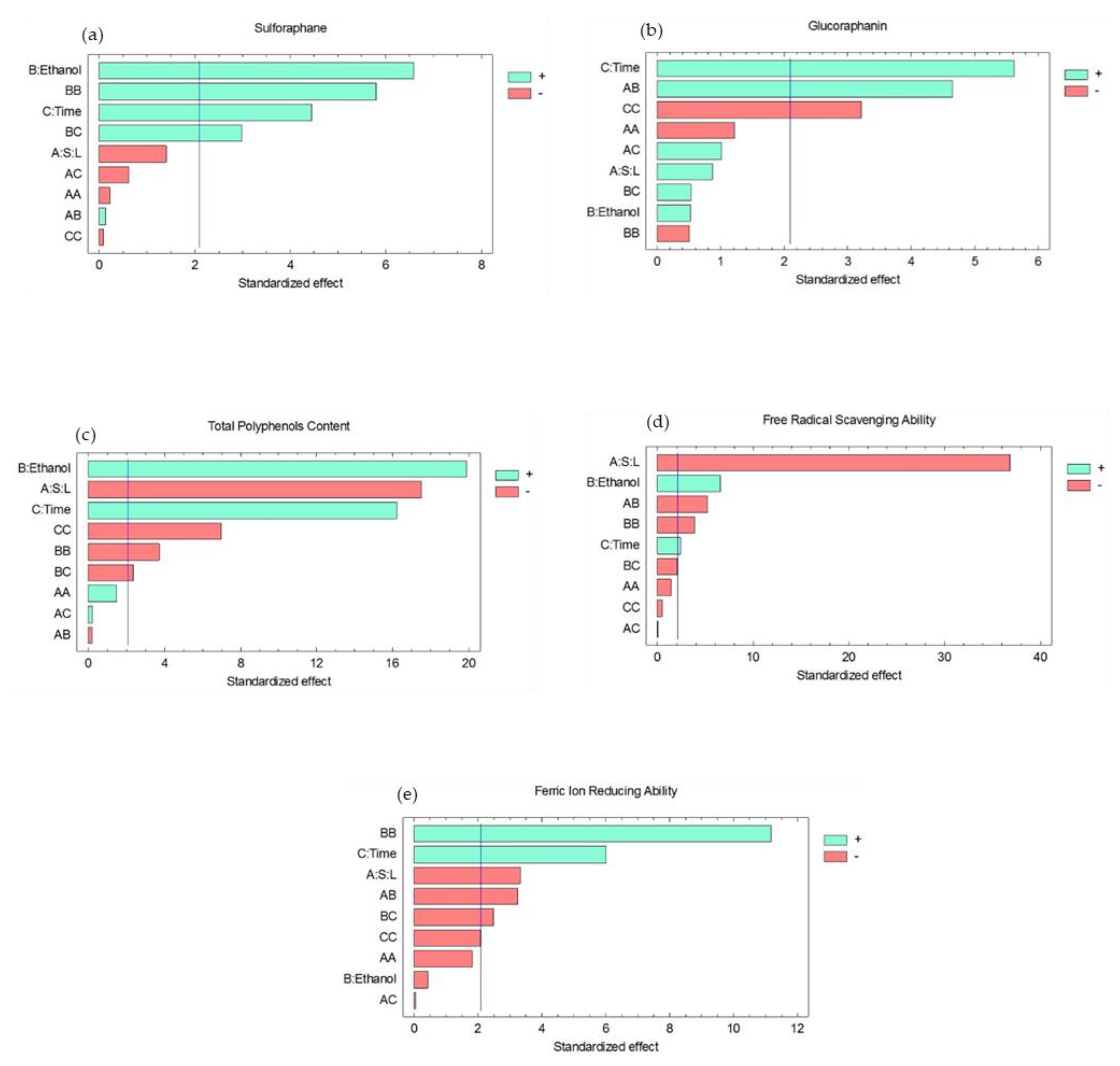

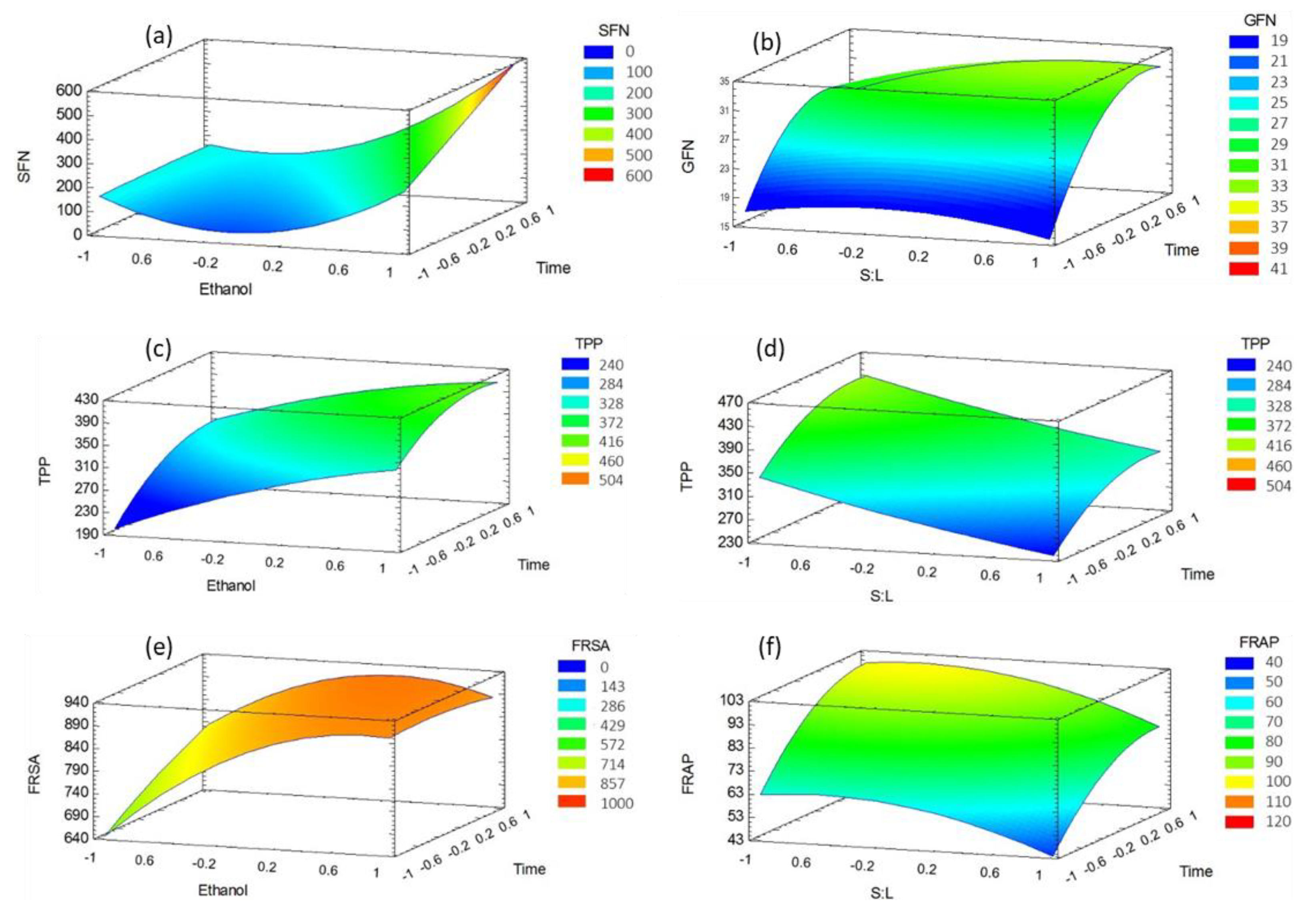

2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of the Experimental Factors on Bioactive Molecules

3.2. Effect of the Experimental Factors on Antioxidant Activity

3.3. Optimization of the Extraction Conditions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Statistical Analysis

4.4. Analytical Determinations

4.4.1. Sulforaphane

4.4.2. Glucoraphanin Content

4.4.3. Total Polyphenols Content

4.4.4. Ferric-Ion-Reducing Ability

4.4.5. Free Radical Scavenging Ability

4.4.6. Moisture Content

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Favela-González, K.M.; Hernández-Almanza, A.Y.; De la Fuente-Salcido, N.M. The value of bioactive compounds of cruciferous vegetables (Brassica) as antimicrobials and antioxidants: A review. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganai, S.A. Histone deacetylase inhibitor sulforaphane: The phytochemical with vibrant activity against prostate cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 81, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, A. Modeling of the effect of selenium fertilization on the content of bioactive compounds in broccoli heads. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahn, A.; Rubio, M. Evolution of total polyphenols content and antioxidant activity in broccoli florets during storage at different temperatures. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez, C.; Barrientos, H.; Román, J.; Mahn, A. Optimization of a blanching step to maximize sulforaphane synthesis in broccoli florets. Food Chem. 2014, 145, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahn, A.; Pérez, C. Optimization of an incubation step to maximize sulforaphane content in pre-processed broccoli. J. Food Sci. Tech. Mys. 2016, 53, 4110–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahn, A.; Román, J.; Reyes, A. Effect of Freeze-Drying of Pre-Processed Broccoli on Drying Kinetics and Sulforaphane Content. Inf. Tecnol. 2016, 27, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fusari, M.; Locatelli, D.; Altamirano, J.; Camargo, A. UAE-HPLC-UV: New Contribution for Fast Determination of Total Isothiocyanates in Brassicaceae Vegetables. J. Chem. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, H.; Yuan, Q.P.; Dong, H.R.; Liu, Y.M. Determination of sulforaphane in broccoli and cabbage by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Mao, J.; Mei, L.; Liu, S. Studies on statistical optimization of sulforaphane production from broccoli seed. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Saldaña, J.; Campas-Baypoli, O.; Sánchez-Machado, D.; López-Cervantes, J. Separation and purification of sulforaphane (1-isothiocyanato-4-(methylsulfinyl) butane) from broccoli seeds by consecutive steps of adsorption-desorption-bleaching. J. Food Eng. 2018, 237, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, P.; Shane, L.; Ruan, R.; Li, D.; Wang, L. Effect of high-pressure homogenization on the extraction of sulforaphane from broccoli (Brassica oleracea) seeds. Powder Technol. 2019, 358, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirilli, R.; Gallo, F.R.; Multari, G.; Palazzino, G.; Mustazza, C.; Panusa, A. Study of solvent effect on the stability of isothiocyanate iberin, a breakdown product of glucoiberin. J. Food Comps. Anal. 2020, 92, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K.; Abu-Ghannam, N.; Gupta, S. A comparative study on the polyphenolic content, antibacterial activity and antioxidant capacity of different solvent extracts of Brassica oleracea vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, X.; Ma, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, P. Extraction and Quantification of Sulforaphane and Indole-3-Carbinol from Rapeseed Tissues Using QuEChERS Coupled with UHPLC-MS/MS. Molecules 2020, 25, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, N.T.T. Process for extraction of glucosinolates from by-products of white cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. alba). Vietnam J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 14, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.P.T.; Stewart, J.; Lopez, M.; Ioannou, I.; Allais, F. Glucosinolates: Natural Occurrence, Biosynthesis, Accessibility, Isolation, Structures, and Biological Activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, Q.D.; Angkawijaya, A.E.; Tran-Nguyen, P.L.; Huynh, L.H.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Ismadji, S.; Ju, Y. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of Limnophila aromatica. J. Food Drug. Anal. 2014, 22, 296–02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hutzler, P.; Fischbach, R.; Heller, W.; Jungblut, T.P.; Reuber, S.; Schmitz, R.; Veit, M.; Weissenböck, G.; Schnitzler, J. Tissue localization of phenolic compounds in plants by confocal laser scanning microscopy. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, A.; Castillo, A. Potential of Sulforaphane as a Natural Immune System Enhancer: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.R.; Kwak, J.H. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity in different tissues of Brassica vegetables. Molecules 2015, 20, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Francisco, M.; Moreno, D.A.; Cartea, M.E.; Ferreres, F.; García-Viguera, C.; Velasco, P. Simultaneous identification of glucosinolates and phenolic compounds in a representative collection of vegetable Brassica rapa. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 6611–6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faller, A.L.K.; Fialho, E. The antioxidant capacity and polyphenol content of organic and conventional retail vegetables after domestic cooking. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cao, Z.; Bi, J.; Yi, J.; Chen, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhou, M. Degradation kinetics of total phenolic compounds, capsaicinoids and antioxidant activity in red pepper during hot air and infrared drying process. Int. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, M.E. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

| Runs | Solid/Liquid Ratio | Ethanol (%) | Extraction Time (min) | SFN (µg/g dw) | GFN (µg/g dw) | TPP (GAE/100 g dw) | FRAP (TE/100 g dw) | FRSA (TE/100 g dw) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preprocessed broccoli | - | - | - | 983.3 ± 3.8 | 70.9 ± 6.3 | 458.0 ± 33.9 | 174.5 ± 12.1 | 1383.6 ± 23.5 |

| 1 | −1(1:50) | −1(0) | 0(40) | 249.1 ± 4.5 | 31.3 ± 5.2 | 342.0 ± 7.4 | 132.7 ± 0.4 | 1018.5 ± 53.2 |

| 2 | +1(1:10) | −1(0) | 0(40) | 136.8 ± 8.6 | 20.4 ± 4.3 | 240.6 ± 6.8 | 120.3 ± 1.1 | 316.1 ± 5.6 |

| 3 | −1(1:50) | +1(80) | 0(40) | 429.5 ± 31.9 | 19.4 ± 8.3 | 460.5 ± 9.6 * | 164.5 ± 0.1 * | 1451.4 ± 9.5 |

| 4 | +1(1:10) | +1(80) | 0(40) | 332.2 ± 14.9 | 40.1 ± 3.3 | 355.9 ± 5.2 | 97.5 ± 0.3 | 351.2 ± 2.4 |

| 5 | 0(1:30) | −1(0) | −1(10) | 58.8 ± 4.9 | 19.4 ± 1.2 | 198.0 ±8.4 | 98.1 ± 1.1 | 657.8 ± 10.4 |

| 6 | 0(1:30) | +1(80) | −1(10) | 213.1 ± 44.3 | 15.2 ± 5.2 | 330.5 ± 3.6 | 109.2 ± 0.2 | 853.8 ± 26.7 |

| 7 | 0(1:30) | −1(0) | +1(70) | 207.3 ± 21.6 | 27.4 ± 1.1 | 316.4 ± 0.4 | 167.0 ± 4.5 * | 832.3 ± 35.8 |

| 8 | 0(1:30) | +1(80) | +1(70) | 682.9 ± 46.1 | 30.1 ± 6.1 | 410.2 ± 0.1 | 136.3 ± 2.2 | 872.2 ± 25.6 |

| 9 | −1(1:50) | 0(40) | −1(10) | 91.4 ± 5.8 | 18.1 ± 0.1 | 342.5 ± 2.1 | 58.6 ± 3.9 | 1373.5 ± 3.6 * |

| 10 | +1(1:10) | 0(40) | −1(10) | 121.8 ± 8.9 | 14.9 ± 3.3 | 240.8 ± 0.7 | 59.4 ± 0.9 | 294.5 ± 2.3 |

| 11 | −1(1:50) | 0(40) | +1(70) | 154.1 ± 2.0 | 31.9 ± 0.4 | 429.1 ± 7.5* | 82.7 ± 3.1 | 1409.0 ± 17.1 |

| 12 | +1(1:10) | 0(40) | +1(70) | 118.9 ± 11.2 | 32.3 ± 1.6 | 331.2 ± 0.4 | 82.5 ± 0.1 | 327.6 ± 1.7 |

| 13 | 0(1:30) | 0(40) | 0(40) | 172.8 ± 5.1 | 26.3 ± 3.2 | 343.3 ± 5.1 | 80.9 ± 0.7 | 860.1 ± 8.2 |

| 14 | 0(1:30) | 0(40) | 0(40) | 103.6 ± 12.9 | 37.3 ± 3.3 | 384.9 ± 11.2 | 98.8 ± 3.2 | 905.7 ± 2.5 |

| 15 | 0(1:30) | 0(40) | 0(40) | 114.4 ± 2.1 | 28.9 ± 1.9 | 349.7 ± 4.5 | 83.8 ± 0.4 | 903.4 ±1.1 |

| Regression Model | R2 (%) | R2 adj (%) | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFN°= 125.3 + 125.7° × B + 84.7° × C + 163.4° × B2 + 80.3° × B° × C | 82.5 | 79.8 | (1) |

| GFN = 29.1 + 7.9° × A + 6.8° × C + 15.8° × A° × B° − 5.5° × C2 | 73.3 | 70.2 | (2) |

| TTP = 363.2 + 50.7 × A + 57.5 × B + 46.9 × C − 16.3 × B2° − 9.7 × B × C° − 30.2 × °C2 | 97.9 | 97.3 | (3) |

| FRAP = 78.1 + 0.9 × A + 17.9 × C − 13.6 × A × B + 50.1B2 − 10.4 × B × C | 87.8 | 85.3 | (4) |

| FRSA = 867.7 − 495.4 × A + 88.0 × B + 32.7 × C − 99.4 × A × C − 73.5 × B2 − 39.1 × B × C | 98.5 | 98.1 | (5) |

| Response | Optimal Conditions | Predicted by Regression Model | Measured Experimentally at the Optimal Conditions | Deviation (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid/Liquid Ratio | Ethanol (%) | Time (min) | ||||

| SFN (µg/g dw) | 1:50 (−1) | 80 (+1) | 70 (+1) | 579.5 | 565.9 ± 8.6 | 0.9–3.8 |

| GFN (µg/g dw) | 1:50 (−1) | 40 (0) | 58 (+0.60) | 39.1 | 46.8 ± 3.1 | 11.8–27.6 |

| TPP (GAE/100 g dw) | 1:50 (−1) | 80 (+1) | 58 (+0.6) | 466.3 | 405.4 ± 19.9 | 8.8–17.3 |

| FRAP (TE/100 g dw) | 1:10 (+1) | 0 (−1) | 70 (+1) | 156.9 | 127.2 ± 0.1 | 18.8–19.0 |

| FRSA (TE/100 g dw) | 1:50 (−1) | 80 (+1) | 10 (−1) | 1483.3 | 1405.3 ± 28.0 | 3.4–7.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González, F.; Quintero, J.; Del Río, R.; Mahn, A. Optimization of an Extraction Process to Obtain a Food-Grade Sulforaphane-Rich Extract from Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica). Molecules 2021, 26, 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26134042

González F, Quintero J, Del Río R, Mahn A. Optimization of an Extraction Process to Obtain a Food-Grade Sulforaphane-Rich Extract from Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica). Molecules. 2021; 26(13):4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26134042

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález, Francis, Julián Quintero, Rodrigo Del Río, and Andrea Mahn. 2021. "Optimization of an Extraction Process to Obtain a Food-Grade Sulforaphane-Rich Extract from Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica)" Molecules 26, no. 13: 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26134042

APA StyleGonzález, F., Quintero, J., Del Río, R., & Mahn, A. (2021). Optimization of an Extraction Process to Obtain a Food-Grade Sulforaphane-Rich Extract from Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica). Molecules, 26(13), 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26134042