An Improved Synthesis of Key Intermediate to the Formation of Selected Indolin-2-Ones Derivatives Incorporating Ultrasound and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Blend of Techniques, for Some Biological Activities and Molecular Docking Studies †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

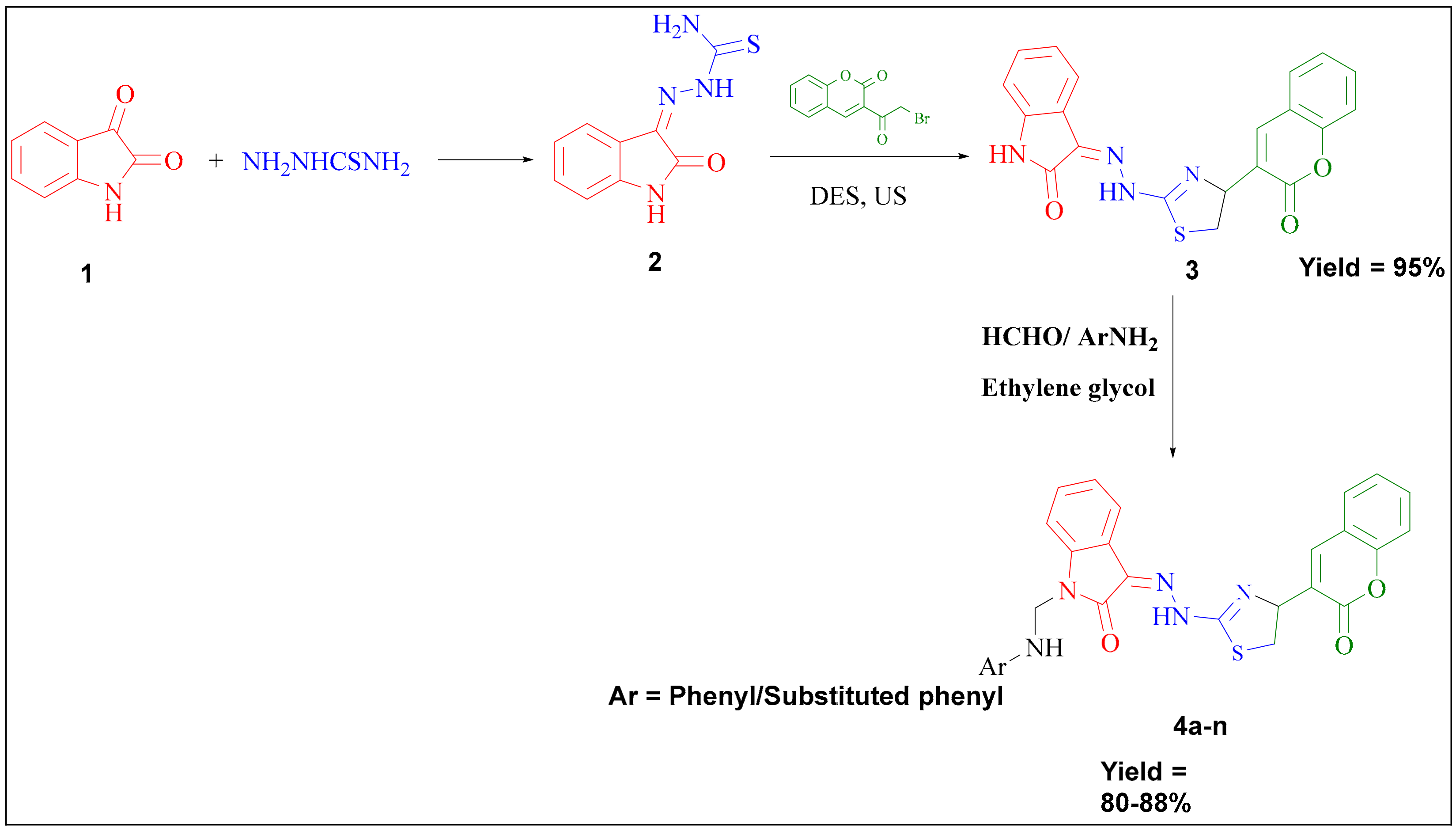

2.1. Chemistry

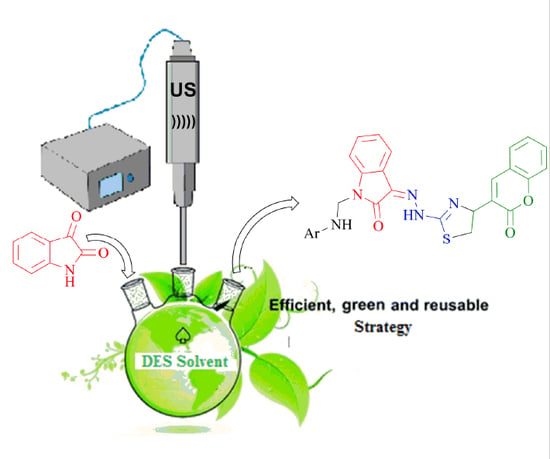

2.1.1. Significance of DES and Ultrasound Blend of Techniques to the Synthesis of Key Intermediate 3-(2-(4-(2-Oxochroman-3-Yl) thiazol-2-yl) Hydrazono) Indolin-2-One

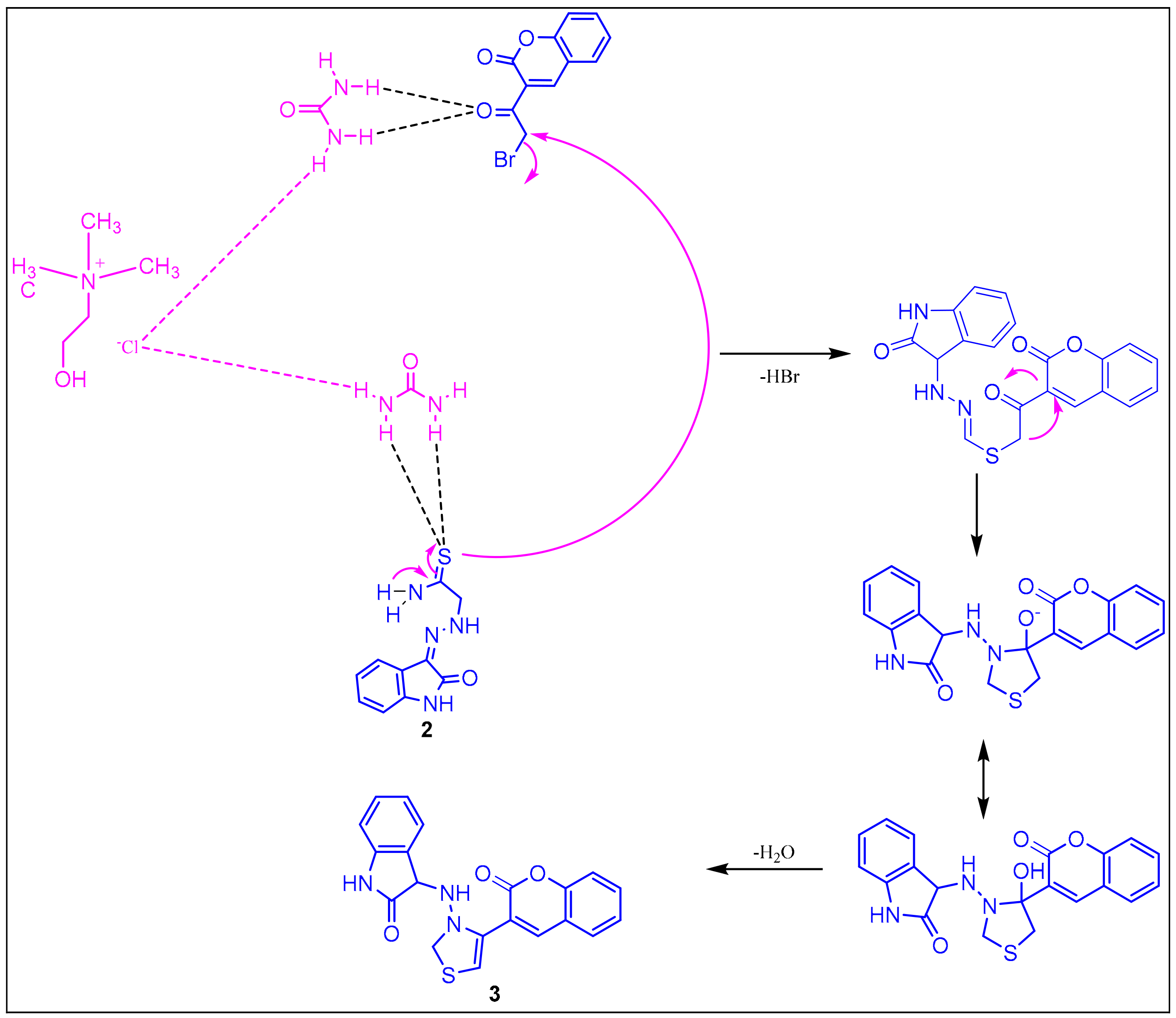

2.1.2. Plausible Mechanism Involved in the Formation of Key Intermediate, 3-(2-(4-(2-Oxochroman-3-Yl) Thiazol-2-yl) Hydrazono) Indolin-2-One

2.2. Biology

2.2.1. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.2.2. Analgesic Activity

2.2.3. Acute Ulcerogenicity

2.2.4. Lipid Peroxidation

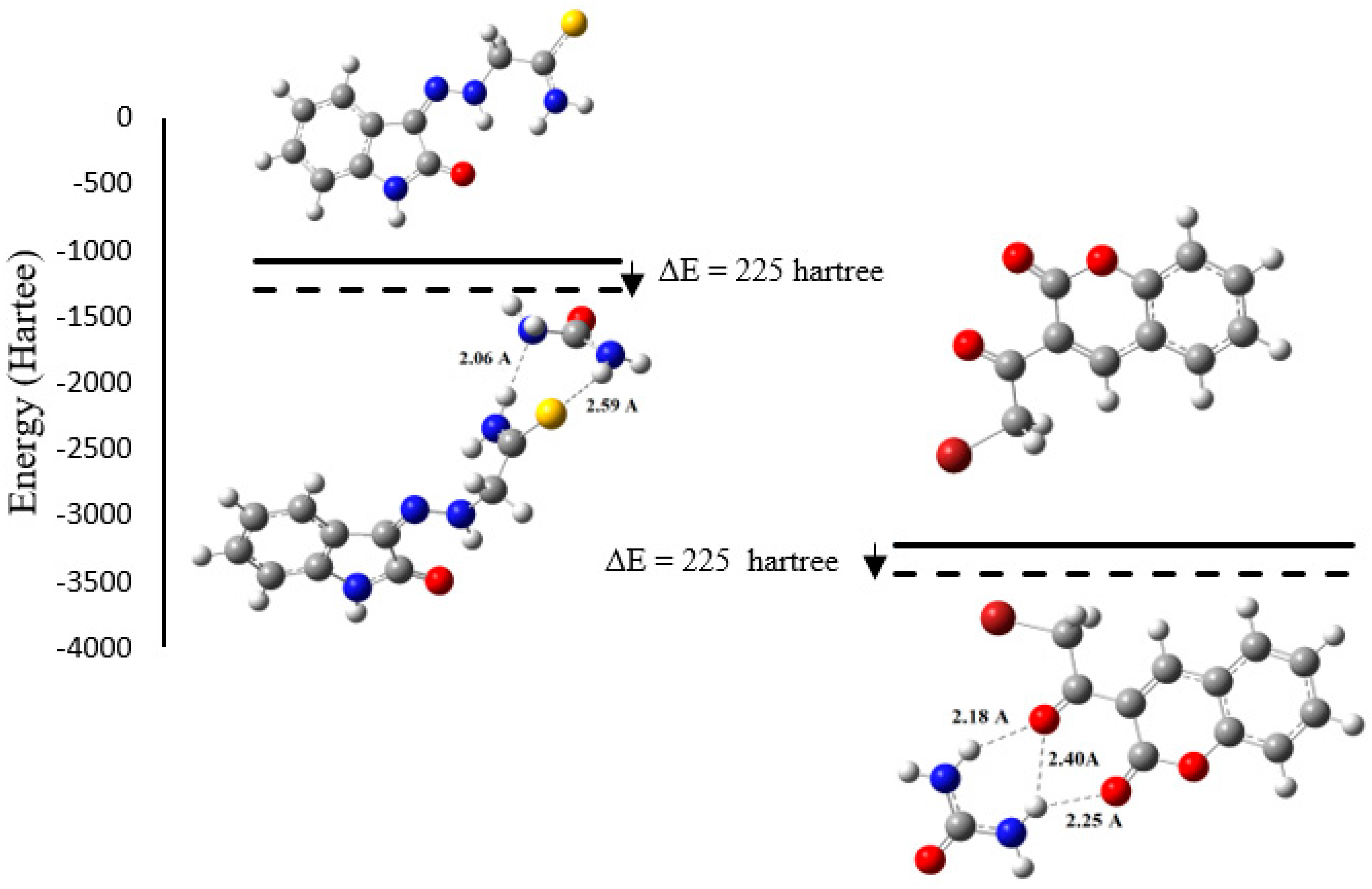

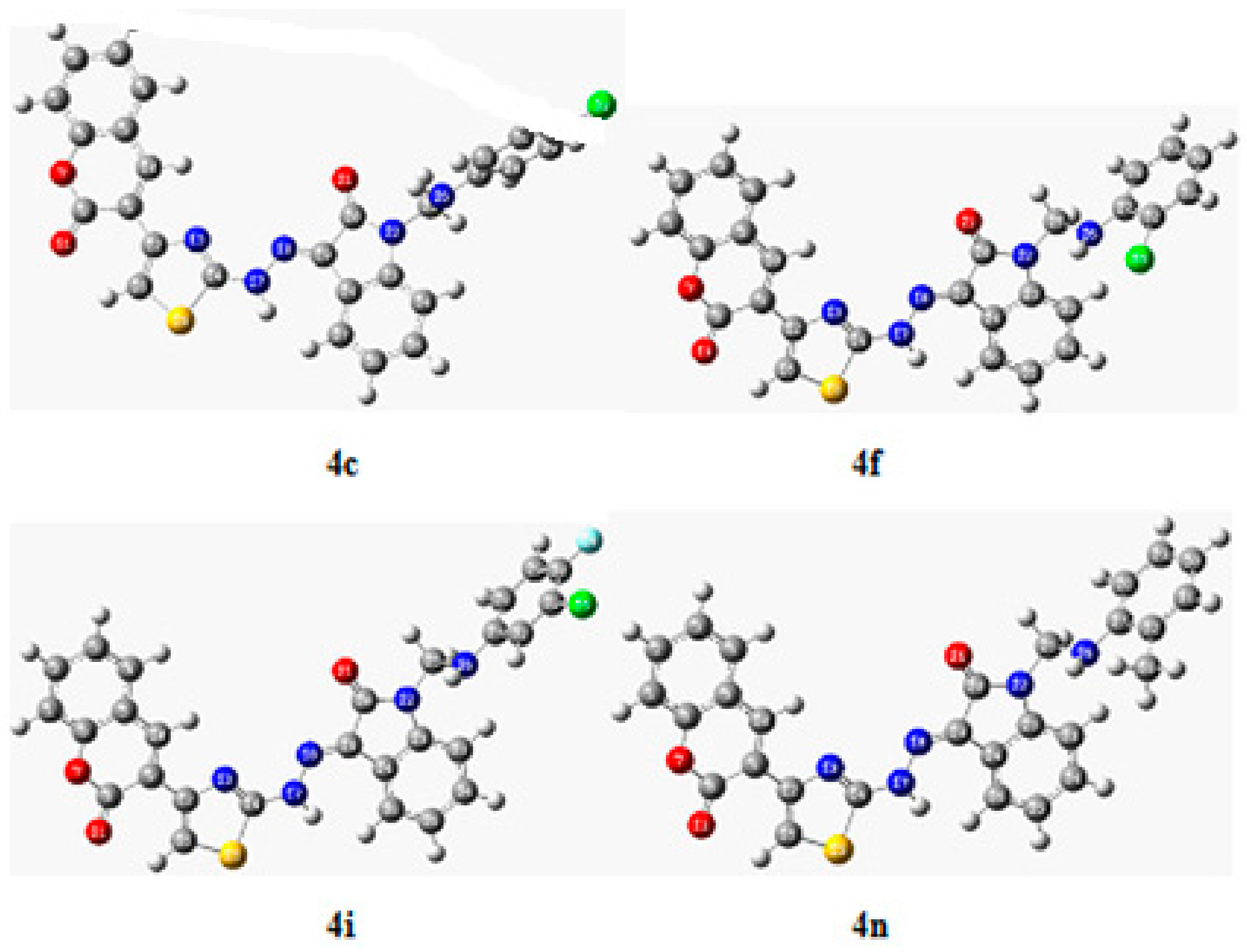

2.2.5. DFT Results

2.2.6. In Silico Study

Target Protein Selection and Retrieval

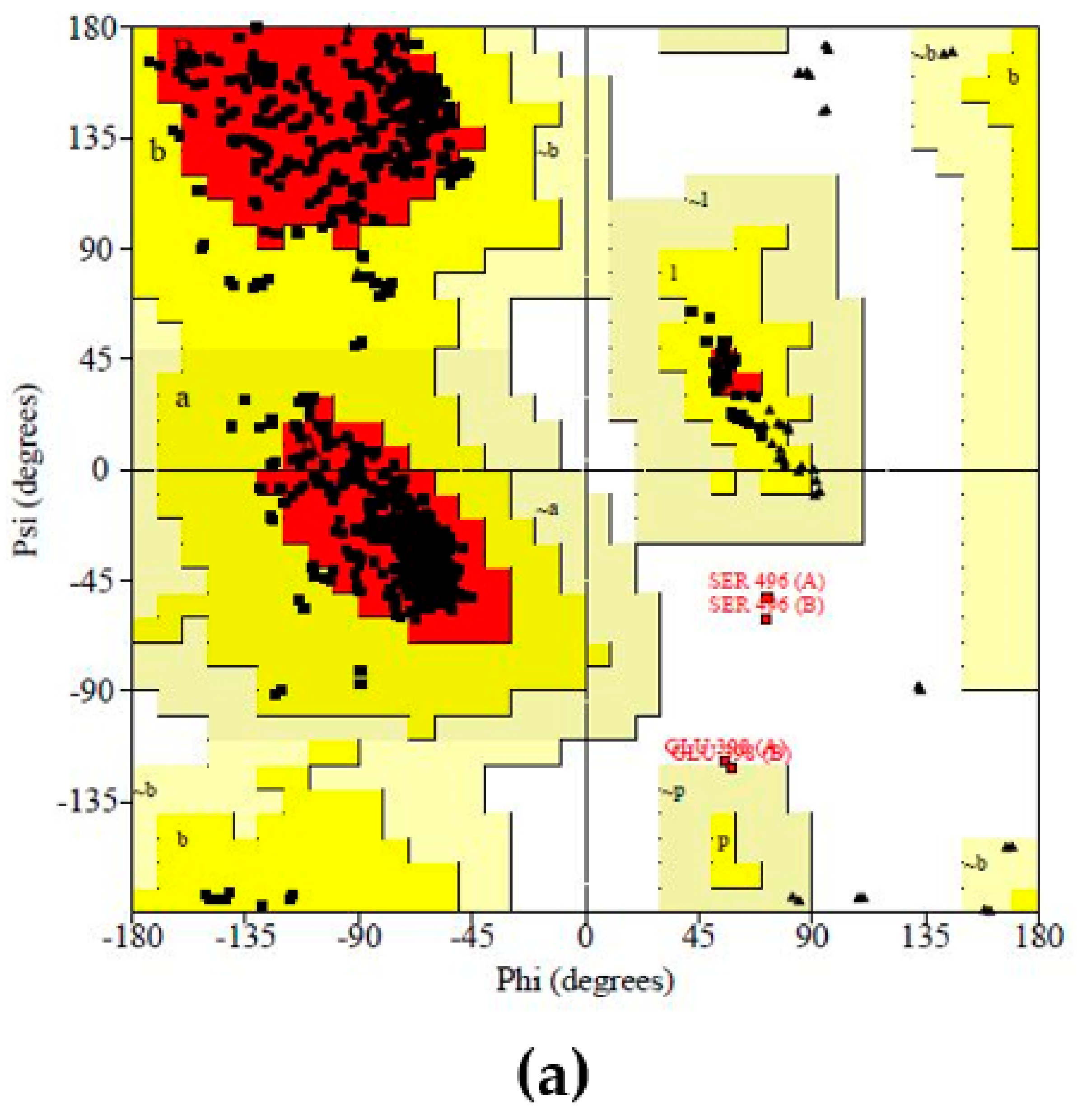

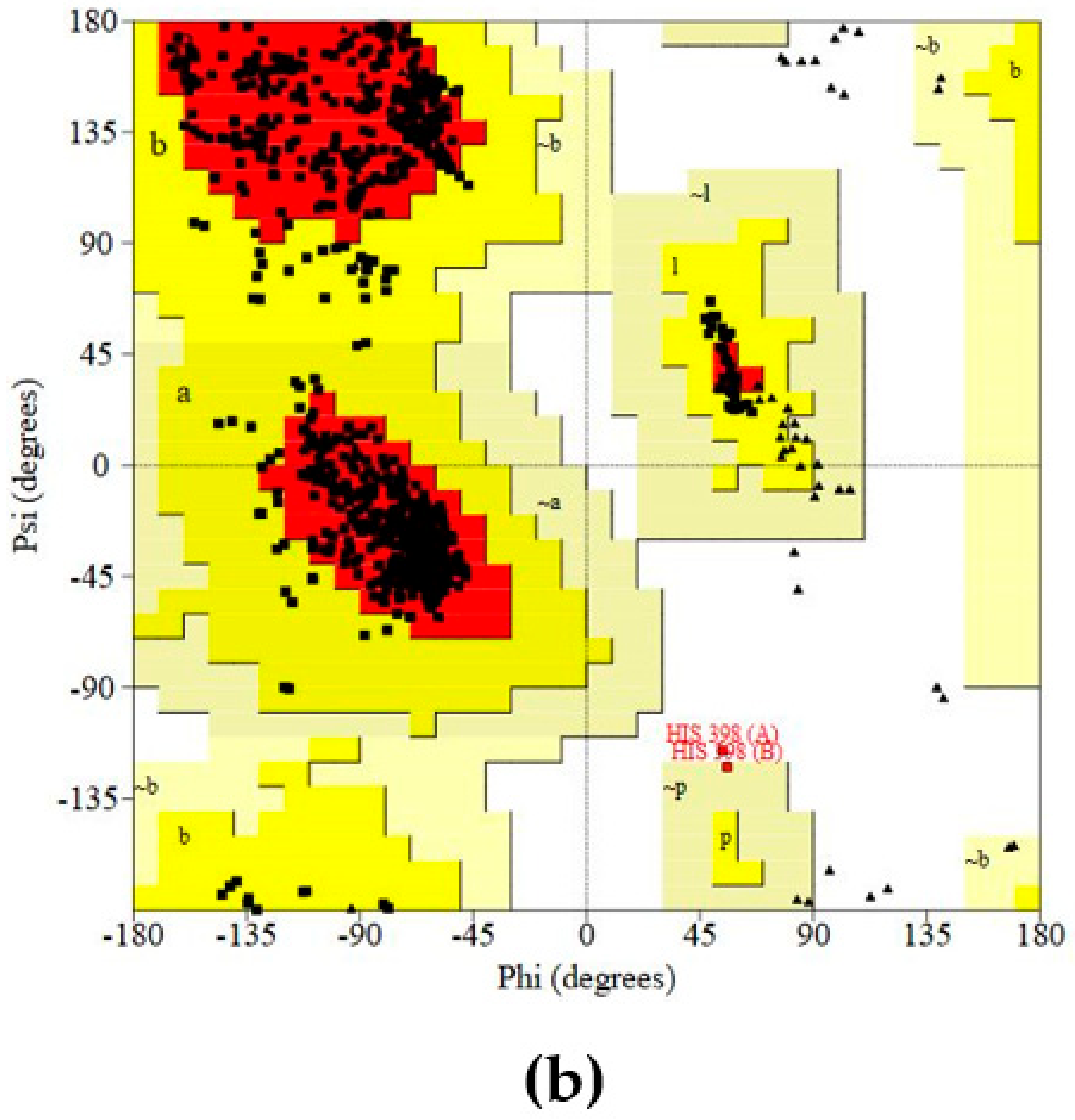

Protein (COX-2) Preparation and Validation

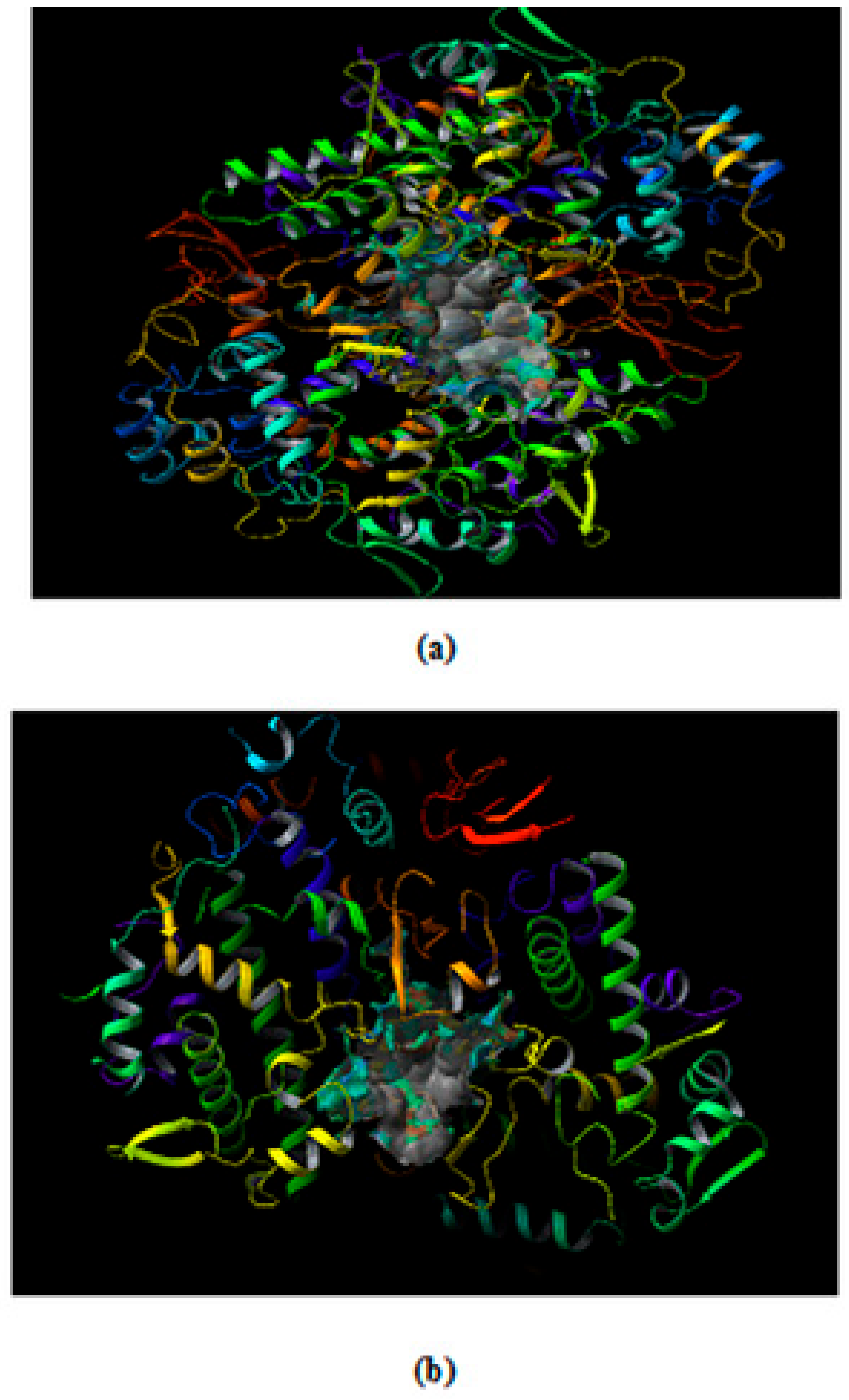

Prediction and Evaluation of the Binding Site in COX-2

Ligand Preparation

Grid Generation in the Target Protein COX-2

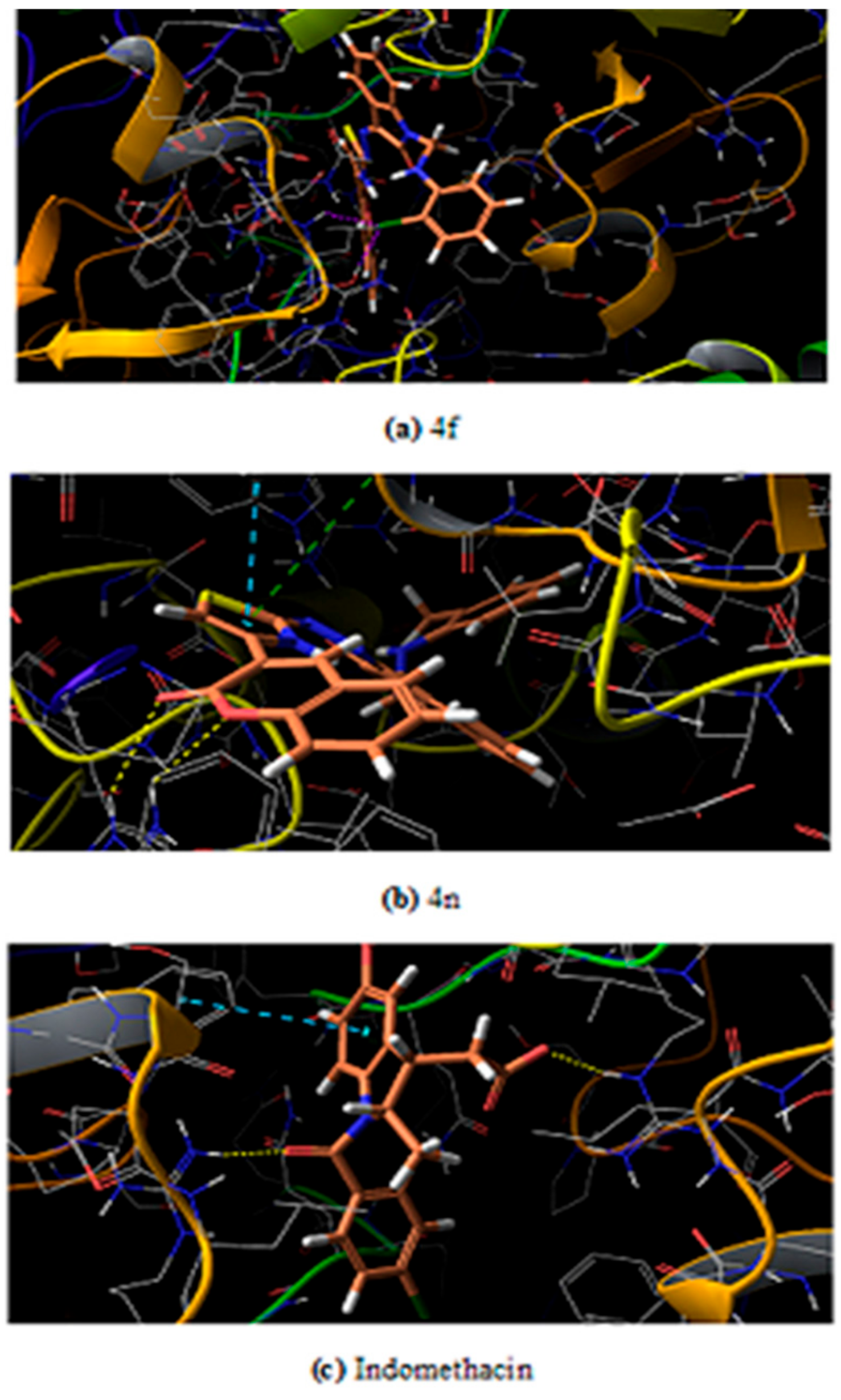

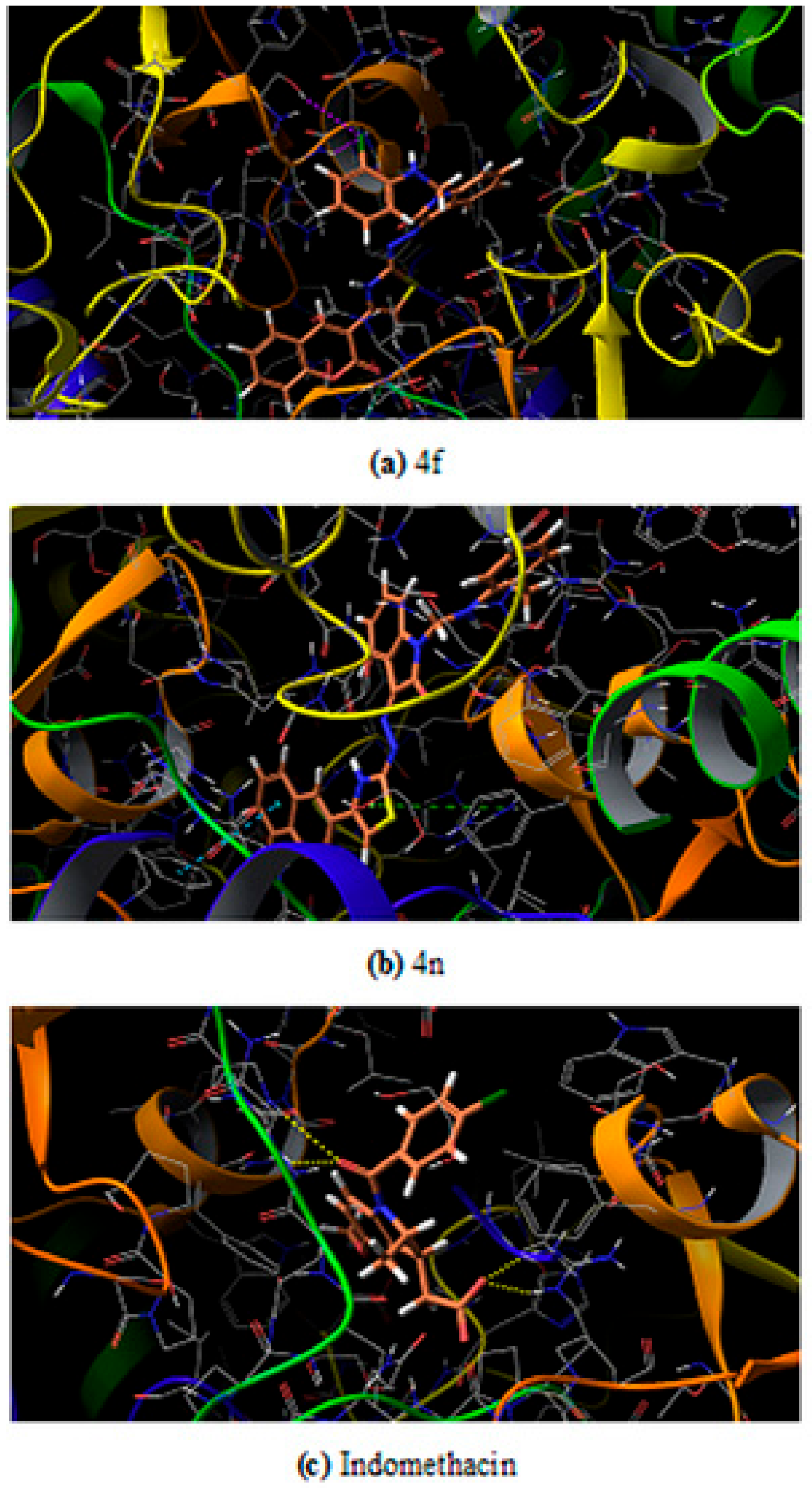

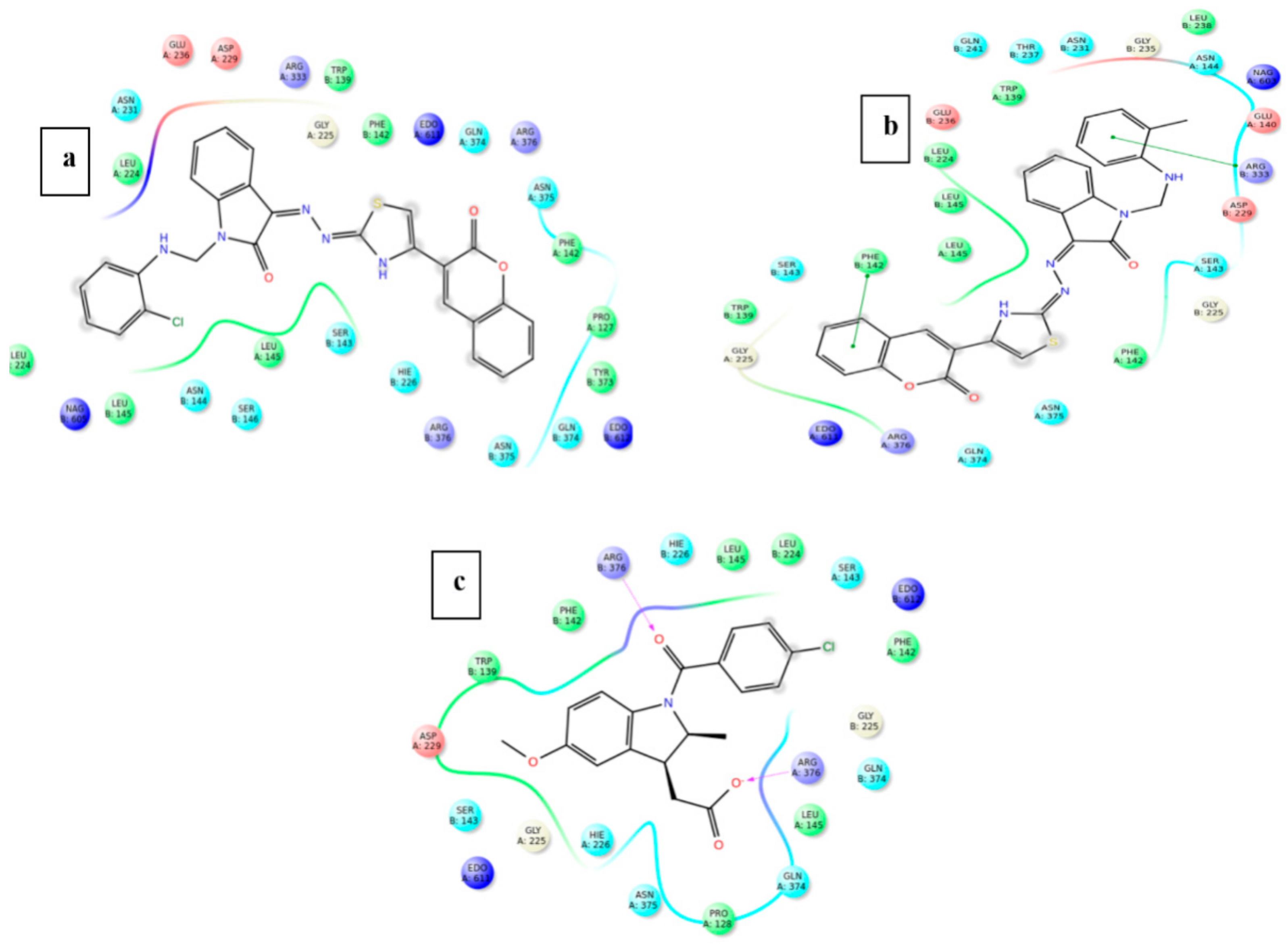

Molecular Docking Studies

ADME Profiling

Statistical Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. Preparation of 2-(2-Oxoindolin-3-Ylidene)Hydrazine Carbothioamide (2)

3.1.2. Preparation of Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES)

3.1.3. Preparation of 3-(2-(4-(2-Oxochroman-3-Yl) Thiazol-2-yl) Hydrazono) Indolin-2-One Using Deep Eutectic Solvent and Ultrasound (3)

3.1.4. Preparation of 1-(substitutedphenylaminomethyl)-3-(2-(4-(2-Oxochroman-3-yl) Thiazol-2-yl)ydrazono)Indolin-One (4a–n)

3.2. Biology

3.2.1. Preparation of 2-(2-Oxoindolin-3-Ylidene) Hydrazine Carbothioamide (2)

3.2.2. Analgesic Activity

3.2.3. Acute Ulcerogenic Activity

3.2.4. Lipid Peroxidation Study

3.2.5. Theoretical Details

3.2.6. In Silico Study

Software

Target Protein Selection and Retrieval

Protein (COX-2) Preparation and Validation of Prepared Structure

Prediction and Evaluation of the Binding Site in COX-2

Ligand Preparation

Grid Generation in the Target Protein COX-2

Docking of Ligands and COX-2

ADME Profiling

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, N.; Sharma, C.S.; Ranawat, M.S.; Singh, H.P.; Chauhan, L.S.; Dashora, N. Synthesis, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of novel mannich bases of benzimidazoles. J. Pharm. Invest. 2015, 45, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasirad, A.; Mousavi, Z.; Tajik, M.; Assarzadeh, M.J.; Shafiee, A. Synthesis, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of new methyl-imidazolyl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles and 1,2,4-triazoles. Daru. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgın-Gökşen, U.; Gökhan-Kelekçi, N.; Göktaş, Ö.; Köysal, Y.; Kılıç, E.; Işık, S.; Aktay, G.; Özalp, M. 1-Acylthiosemicarbazides, 1,2,4-triazole-5(4H)-thiones, 1,3,4-thiadiazoles and hydrazones containing 5-methyl-2-benzoxazolinones: Synthesis, analgesic anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 5738–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, H.; Javed, S.A.; Khan, S.A.; Amir, M. 1,3,4-Oxadiazole/thiadiazole and 1,2,4-triazole derivatives of biphenyl-4yloxy acetic acid: Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of biological properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 2688–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marnett, L.J.; Kalgutkar, A.S. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors: Discovery, selectivity and the future. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999, 20, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnett, L.J.; Kalgutkar, A.S. Design of selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2 as nonulcerogenic anti-inflammatory agents. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998, 2, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsit, P.; Reindeau, D. Selective Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 1997, 32, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Almansa, C.; Alfon, J.; Cavalcanti, F.L. Synthesis and Structure–Activity Relationship of a New Series of COX-2 Selective Inhibitors: 1,5-Diarylimidazoles. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 3463–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafeefy, A.M.; Bakht, M.A.; Ganaie, M.A.; Ansarie, M.N.; NEl-Sayed, N.N.; Awaad, A.S. Synthesis, analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcerogenic activities of certain novel Schiff’s bases as fenamate isosteres. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujubu, D.A.; Fletcher, B.S.; Varnuzu, B.; Lim, R.W.; Herschmann, H.R. TIS10, a phorbol ester tumor promotor-inducible mRNA from Swiss 3T3 cells, encodes a novel prostaglandin synthase/cyclooxygenase homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 12866–12872. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.A.; Akarasereenont, P.; Thiemermann, C.; Flower, R.J.; Vane, J.R. Selectivity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as inhibitors of constitutive and inducible cyclooxygenase. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 11693–11697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 1996, 6, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, J.F.; Williams, C.A.; Bloch, D.A. The relative toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arthr. Rhem. 1991, 34, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, M.; Singh, D.; Singh, S.; Sharma, V.; Gaba, P. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel 5-substituted-1-(phenylsulfonyl)-2-methylbenzimidazole derivatives as anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 2245–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghi, A.; Arfaei, S. Selective COX-2 inhibitors: A review of their structure-activity relationships. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 10, 655–683. [Google Scholar]

- Sujatha, K.; Perumal, P.T.; Muralidharan, D.; Rajendran, M. Synthesis, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of bis(indolyl)methanes. Ind. J. Chem. 2009, 48B, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nirmal, R.; Prakash, C.R.; Meenakshi, K.; Shanmugapandiyan, P. Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Novel SchiffBase Analogues of 3-(4-amino)Phenylimino)5-fluoroindolin-2-one. J. Young. Pharm. 2010, 2, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, R.S.; More, H.N.; Bhosale, A.V. Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation of Analgesic and Anti-inflammatory Activities of Some Novel Indoles. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 10, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.K.; Kumar, T.V. Synthesis of [2-(3-oxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[1,4]oxazin-6-carbonyl)-1-1H-indol-3-yl]acetic acids as potential COX-2 inhibitors. Ind. J. Chem. 2006, 45B, 2128–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, A.; Pandey, P. A facile synthesis of N-phenyl-6-hydroxy-3-bromo-4-arylazo under phase transfer catalytic conditions and studies on their antimicrobial activities. Ind. J. Chem. 2006, 45B, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, R.; Ignatova, M.; Manolova, N.; Petrova, T.; Rashkov, I. Preparation, characterization and biological activity of Schiffbase compounds derived from 8-hydroxyquinoline-2-carboxaldehyde and Jeffamines ED. Eur. Polym. J. 2002, 38, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, D.; Akram, M.; Kaur, H. Synthesis and evaluation of some newer indole derivatives as anticonvulsant agents. Int. J. Pharm. Bio. Arch. 2011, 2, 744–750. [Google Scholar]

- Jayashree, B.S.; Nigam, S.; Pai, A.; Chowdary, P.V.R. Overview on the recently developed coumarinyl heterocycles as useful therapeutic agents. Arabian J. Chem. 2014, 7, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin-Mei, P.; Guri, L.V.D.; Cheng, H.Z. Current developments of coumarin compounds in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Pharm. 2013, 19, 3884–3930. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopala, K.N.; Rashmi, V.; Odhav, B. Review on natural coumarin lead compounds for their pharmacological activity. BioMed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhi, M.G.; Khaled, D.K. A convenient ultrasound-promoted synthesis of some new thiazole derivatives bearing a coumarin nucleus and their cytotoxic activity. Molecules 2012, 17, 9335–9347. [Google Scholar]

- Thoraya, A.F.; Maghda, A.A.; Ghada, S.M.; Zeinab, A.M. New and efficient approach for synthesis of novel bioactive [1,3,4] thiadiazoles incorporated with 1,3-thiazole moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 320–333. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.S.; Lobo, H.R.; Pinjari, D.V.; Jaraq, K.J.; Pandit, A.B.; Shankarling, G.S. Ultrasound and deep eutectic solvent (DES): A novel blend of techniques for rapid and energy efficient synthesis of oxazoles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013, 1, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakht, M.A.; Ansari, M.J.; Riaydi, Y.; Ajmal, N.; Ahsan, M.J.; ShaharYar, M. Physicochemical characterization of benzalkonium chloride and urea based deep eutectic solvent (DES): A novel catalyst for the efficient synthesis of isoxazolines under ultrasonic irradiation. Mol. Liquid. 2016, 224, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Su, X.M. A meldrum’s acid catalyzed synthesis of Bis(Indolyl) methanes in water under ultrasonic condition. Chin. J. Chem. 2008, 26, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, B.W. An efficient ultrasound-promoted method for the one-pot synthesis of 7,10,11,12-tetrahydrobenzo [C] acridin-8(9)–one derivatives. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010, 17, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Khan, S.A. Anti-inflammatory activity of some new 3-(2H-1-benzopyran-2-one-3-yl)-5-substituted ary lisoxazolines. Asian J. Chem. 2004, 16, 543–545. [Google Scholar]

- El-Feky, H.A.S.; Imran, M.; Osman, A.N. Guanidine-annellated heterocycles: Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 2-aminopyridoimidazotriazines, pyridoimidazopyrimidines, pyridoimidazotriazoles and pyridoimidazoles. BAOJ Pharm. Sci. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.K.; Imran, M.; Rehman, Z.U.; Khan, S.A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of some 2-substituted benzimidazoles. Asian J. Chem. 2005, 17, 2741–2747. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, O.; Gupta, S.K.; Imran, M.; Khan, S.A. Synthesis and biological activity of some 2,5-disubstituted 1,3,4-oxadiazoles. Asian J. Chem. 2005, 17, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, M.A. Synthesis of Sulfonyl 2-(prop-2-yn-1-ylthio) benzo [d] thiazole derivatives. Al-Nahrain J. Sci. 2015, 18, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Fatima, A.; Rout, C.; Sing, R. An efficient one-pot synthesis of 2-aminothiazole derivatives. Der. Chem. Sin. 2015, 6, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelriheem, N.A.; Mohamed, A.M.M.; Abdelhamid, A.O. Synthesis of some new 1,3,4-Thiadiazole, Thiazole and pyridine derivatives containing 1,2,3-Triazole moiety. Molecules 2017, 22, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakht, M.A. Synthesis of some oxadiazole derivatives using conventional solvent and deep eutectic solvent (DES) under ultrasonic irradiation: A comparative study. Adv. Biores. 2016, 7, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bakht, M.A. Ultrasound mediated synthesis of some pyrazoline derivatives using biocompatible deep eutectic solvent (DES). Der. Pharm. Chem. 2015, 7, 274–278. [Google Scholar]

- Pohle, T.; Brzozowski, T.; Becker, J.C.; VanderVoort, I.R.; Markmann, A.; Konturek, S.J.; Moniczewski, A.; Domschke, W.; Konturek, J.W. Role of reactive oxygen metabolites in aspirin-induced gastric damage in humans: Gastroprotection by vitamin C. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, K.C.; Walters, M.J.; Musee, J.; Harp, J.M.; Kiefer, J.R.; Oates, J.A.; Marnett, L.J. Molecular basis for cyclooxygenase inhibition by the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 34950–34959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucido, M.J.; Orlando, B.J.; Vecchio, A.J.; Malkowski, M.G. Crystal Structure of Aspirin-Acetylated Human Cyclooxygenase-2: Insight into the Formation of Products with Reversed Stereochemistry. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.J.; Zhang, W.; Xia, K.; Qiao, X.B.; Xu, X.J. ADME evaluation in drug discovery. 5.Correlation of caco-2 permeation with simple molecular properties. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1585–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J. Carrageenan-induced paw edema in the rat and mouse. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003, 225, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Cioli, V.; Putzolu, S.; Rossi, V.; ScorzaBarcellona, P.; Corradino, C. The role of direct tissue contact in the production of gastrointestinal ulcers byanti-inflammatory drugs in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1979, 50, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anouar, E.; Calliste, C.; Kosinova, P.; DiMeo, F.; Duroux, J.; Champavier, Y.; Marakchi, K.; Trouillas, P. Free radical scavenging properties of guaiacol oligomers: A combined experimental and quantum study of the guaiacyl-moiety role. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 13881–13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anouar, E.H. A quantum chemical and statistical study of phenolic schiff bases with antioxidant activity against DPPH free radical. Antioxidants 2014, 3, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anouar, E.H.; Shah, S.A.A.; Hassan, B.; Moussaoui, N.E.; Ahmad, R.; Zulkefeli, M.; Weber, J.F.F. Antioxidant activity of hispidin oligomers from medicinal fungi: A DFT study. Molecules 2014, 19, 3489–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucks, G.W.; Frisch, M.J.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09 Revision, A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Friesner, R.A.; Xiang, Z.; Honig, B. On the role of thecrystal environment in determining protein side-chain conformations. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 3220, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Pincus, D.L.; Rapp, C.S.; Day, T.J.; Honig, B.; Shaw, D.E.; Friesner, R.A. A hierarchical approach to all–atom protein loop prediction. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2004, 367, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sastry, G.M.; Adzhigirey, M.; Sherman, W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters protocols and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repask, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra precision glide: Docking and scoring incorporationa model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein–ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halgren, T.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Friesner, R.A.; Beard, H.S.; Frye, L.L.; Pollard, W.T.; Banks, J.L. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring.2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1750–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Sample Availability: Samples of the synthesized compounds are available from the authors. |

| Compound | % Age Inhibition of Rat Paw Edema (Dose = 10 mgkg−1) | Potency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 H | 4 H | ||

| Indomethacin | 66.34 ± 0.051 | 82.05 ± 0.08 | 1.00 |

| 4a | 38.29 ± 0.016 | 5.57 ± 0.041 | 0.06 |

| 4b | 59.29 ± 0.73 * | 45.81 ± 0.069 | 0.55 |

| 4c | 59.29 ± 0.143 * | 30.17 ± 0.294 | 0.36 |

| 4d | 51.92 ± 0.337 | 6.98 ± 0.315 | 0.08 |

| 4e | 62.24 ± 0.080 ** | 48.60 ± 0.090 ** | 0.59 |

| 4f | 48.377 ± 0.219 * | 72.42 ± 0.183 * | 0.88 |

| 4g | 53.57 ± 0.160 * | 77.94 ± 0.184 *** | 0.94 |

| 4h | 35.39 ± 0.273 | 64.69 ± 0.245 | 0.78 |

| 4i | 31.268 ± 0.188 | 63.95 ±0.218 | 0.77 |

| 4j | 53.81 ± 0.120 ** | 77.906 ± 0.171 ** | 0.94 |

| 4k | 38.095 ± 0.214 | 70.75 ± 0.165 | 0.86 |

| 4l | 54.76 ± 0.228 ** | 80.94 ± 0.149 *** | 0.98 |

| 4m | 53.27 ± 0.183 * | 78.42 ±0.183 ** | 0.95 |

| 4n | 42.57 ± 0.213 | 69.58 ± 0.133 | 0.84 |

| Compound | Mean with ± SEM | % Analgesic Activity (Dose = 10 mgkg−1) | Potency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indomethacin | 8.55 ± 0.394 | 73.61 ± 0.315 * | 1.00 |

| 4a | 17.00 ± 0.2582 | 47.54 ± 0.7071 * | 0.64 |

| 4b | 24.00 ± 0.3651 | 25.94 ± 0.5802 ** | 0.35 |

| 4c | 13.00 ± 0.2582 | 59.88 ± 0.8458 * | 0.81 |

| 4d | 18.50 ± 0.4282 | 42.91 ± 0.710 *** | 0.58 |

| 4e | 16.88 ± 0.222 | 47.91 ± 1.0049 * | 0.65 |

| 4f | 9.93 ± 0.386 | 69.36 ± 0.5845 * | 0.94 |

| 4g | 20.09 ± 0.3561 | 38.01 ± 1.0035 ** | 0.51 |

| 4h | 23.83 ± 0.3073 | 26.47 ± 0.3165 * | 0.35 |

| 4i | 10.93 ± 0.3128 | 66.27 ± 1.0072 * | 0.90 |

| 4j | 17.13 ± 0.539 | 47.14 ± 0.4018 *** | 0.64 |

| 4k | 29.83 ± 0.3073 | 7.96 ± 0.4318 * | 0.10 |

| 4l | 17.83 ± 0.3079 | 44.98 ± 0.3361 * | 0.61 |

| 4m | 21.83 ± 0.2051 | 32.64 ± 0.8454 ** | 0.44 |

| 4n | 10.00 ± 0.3651 | 69.14 ± 0.6892 * | 0.93 |

| Compound | Severity Index | Nanomoles of MDA Content ± SEM/ 100 mg Tissue |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.0 | 3.16 ± 0.12 * |

| Indomethacin | 4.500 ± 0.316 | 6.71 ± 0.18 * |

| 4c | 0.666 ± 0.105 * | 4.26 ± 0.12 * |

| 4f | 0.666 ± 0.105 * | 4.08 ± 0.22 * |

| 4i | 0.500 ± 0.129 | 3.89 ± 0.17 * |

| 4n | 0.833 ± 0.210 * | 4.81 ± 0.13 * |

| Compound | IP (eV) | 17-NH | 26-NH | Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4c | −5.96 | 62.03 | 72.58 | 4.08 ± 0.22 |

| 4f | −5.97 | 62.08 | 75.60 | 4.26 ± 0.12 |

| 4i | −6.04 | 62.05 | 72.84 | 3.89 ± 0.17 |

| 4n | −5.80 | 62.05 | 72.02 | 4.81 ± 0.13 |

| S. No | Ligand | Docking Score (kcal/mol) | E-Model Score (kcal/mol) | Energy (kcal/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Human | Mouse | Human | Mouse | Human | ||

| 1 | 4a | −7.050 | −6.834 | −84.018 | −85.694 | −59.395 | −60.236 |

| 2 | 4b | −8.552 | −7.398 | −93.570 | −91.718 | −61.736 | −63.562 |

| 3 | 4c | −6.847 | −7.368 | −89.139 | −90.888 | −65.402 | −63.532 |

| 4 | 4d | −6.271 | −7.419 | −86.746 | −90.209 | −64.531 | −63.856 |

| 5 | 4e | −6.995 | −7.200 | −88.939 | −90.453 | −63.810 | −64.065 |

| 6 | 4f | −6.071 | −6.859 | −78.327 | −79.342 | −58.256 | −59.290 |

| 7 | 4g | −7.247 | −7.426 | −92.213 | −92.642 | −65.665 | −64.682 |

| 8 | 4h | −8.422 | −7.760 | −99.511 | −97.487 | −65.199 | −66.691 |

| 9 | 4i | −7.242 | −7.446 | −92.293 | −93.023 | −64.084 | −64.835 |

| 10 | 4j | −8.120 | −7.250 | −97.069 | −89.953 | −64.452 | −62.022 |

| 11 | 4k | −7.887 | −7.261 | −94.176 | −90.861 | −63.958 | −63.245 |

| 12 | 4l | −8.447 | −7.544 | −95.832 | −81.672 | −65.289 | −56.454 |

| 13 | 4m | −7.898 | −6.803 | −85.845 | −84.328 | −59.419 | −60.257 |

| 14 | 4n | −6.693 | −7.077 | −85.842 | −87.991 | −62.568 | −61.802 |

| 15 | Indomethacin | −6.324 | −6.109 | −57.309 | −58.132 | −39.727 | −40.695 |

| S. No | Ligand | Types of Interaction | Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4a | Solvation effect | - |

| 2 | 4b | 1 H-bond, 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Asn 37 |

| 3 | 4c | 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142 |

| 4 | 4d | 1 H-bond, 1 pi–pi stacking | Trp, 139, Phe, 142 |

| 5 | 4e | 2 H-bond | Leu 145, Ser 146 |

| 6 | 4f | Solvation effect | - |

| 7 | 4g | 2 H-bond | Leu 145, Ser 146 |

| 8 | 4h | 1 H-bond, 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Gly 225 |

| 9 | 4i | 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 133 |

| 10 | 4j | 3 H-bond | Glu 142, Arg 376 |

| 11 | 4k | 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142 |

| 12 | 4l | 3 H-bond, 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Val 228, Asn 375, Asn 537 |

| 13 | 4m | 1 H-bond, 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Asn 375 |

| 14 | 4n | 2 H-bond | Arg 376 |

| 15 | Indomethacin | 2 H-bond, 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 376 |

| S. No | Ligand | Types of Interaction | Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4a | 1 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142 |

| 2 | 4b | 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 333 |

| 3 | 4c | 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 333 |

| 4 | 4d | 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 333 |

| 5 | 4e | 2 H-bond | Leu 145, Ser 146 |

| 6 | 4f | Solvation effect | - |

| 7 | 4g | 3 H-bonds | Leu 145, Ser 146, Nag 605 |

| 8 | 4h | 2 H-bond, 1 pi–pi stacking | Arg 333, Arg 376 |

| 9 | 4i | 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 333 |

| 10 | 4j | 2 H-bond | Glu140, Arg 376 |

| 11 | 4k | 1 H-bond, pi–pi stacking | Trp 139, Phe 142, Arg 333 |

| 12 | 4l | 2 H-bond, 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Gln 241, Arg 333 |

| 13 | 4m | 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 333 |

| 14 | 4n | 2 pi–pi stacking | Phe 142, Arg 333 |

| 15 | Indomethacin | 2 H-bonds | Arg 376 |

| S. No | Ligand | Mol. Wt. | QPlogPo/w (Octanol/ Water) | Apparent Caco-2 Permeability (QPP Caco) | Brain/Blood Partition Coefficient (QPlogBB) | Apparent MDCK Permeability (QppMDCK) | Human Oral Absorption % (QP%) | Lipinski Rule of 5 Violations (Rule of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4a | 493.539 | 5.757 | 574.519 | −1.128 | 540.552 | 100 | 1 |

| 2 | 4b | 511.529 | 5.966 | 521.054 | −1.100 | 880.621 | 84.589 | 2 |

| 3 | 4c | 527.984 | 6.226 | 521.126 | −1.051 | 1201.640 | 86.113 | 2 |

| 4 | 4d | 572.435 | 6.306 | 521.273 | −1.043 | 1292.410 | 86.581 | 2 |

| 5 | 4e | 538.536 | 4.878 | 85.123 | −2.223 | 59.380 | 64.132 | 2 |

| 6 | 4f | 527.984 | 6.047 | 479.473 | −1.121 | 809.359 | 84.417 | 2 |

| 7 | 4g | 583.534 | 4.121 | 10.166 | −3.511 | 5.971 | 43.182 | 2 |

| 8 | 4h | 484.491 | 2.102 | 23.583 | −1.616 | 18.982 | 50.863 | 1 |

| 9 | 4i | 545.974 | 6.468 | 578.335 | −0.889 | 2174.980 | 88.336 | 2 |

| 10 | 4j | 494.927 | 4.735 | 329.574 | −1.421 | 3.000 | 100 | 0 |

| 11 | 4k | 494.927 | 4.703 | 313.043 | −1.444 | 296.440 | 100 | 0 |

| 12 | 4l | 538.536 | 5.003 | 68.904 | −2.393 | 54.611 | 50.266 | 3 |

| 13 | 4m | 507.566 | 6.083 | 574.067 | −1.164 | 540.037 | 86.024 | 2 |

| 14 | 4n | 507.566 | 6.027 | 619.284 | −1.085 | 586.303 | 86.288 | 2 |

| 15 | Indomethacin | 373.835 | 3.679 | 185.783 | −0.614 | 251.855 | 89.095 | 0 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Imran, M.; Bakht, M.A.; Khan, A.; Alam, M.T.; Anouar, E.H.; Alshammari, M.B.; Ajmal, N.; Vimal, A.; Kumar, A.; Riadi, Y. An Improved Synthesis of Key Intermediate to the Formation of Selected Indolin-2-Ones Derivatives Incorporating Ultrasound and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Blend of Techniques, for Some Biological Activities and Molecular Docking Studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25051118

Imran M, Bakht MA, Khan A, Alam MT, Anouar EH, Alshammari MB, Ajmal N, Vimal A, Kumar A, Riadi Y. An Improved Synthesis of Key Intermediate to the Formation of Selected Indolin-2-Ones Derivatives Incorporating Ultrasound and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Blend of Techniques, for Some Biological Activities and Molecular Docking Studies. Molecules. 2020; 25(5):1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25051118

Chicago/Turabian StyleImran, Mohd, Md. Afroz Bakht, Abida Khan, Md. Tauquir Alam, El Hassane Anouar, Mohammed B. Alshammari, Noushin Ajmal, Archana Vimal, Awanish Kumar, and Yassine Riadi. 2020. "An Improved Synthesis of Key Intermediate to the Formation of Selected Indolin-2-Ones Derivatives Incorporating Ultrasound and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Blend of Techniques, for Some Biological Activities and Molecular Docking Studies" Molecules 25, no. 5: 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25051118

APA StyleImran, M., Bakht, M. A., Khan, A., Alam, M. T., Anouar, E. H., Alshammari, M. B., Ajmal, N., Vimal, A., Kumar, A., & Riadi, Y. (2020). An Improved Synthesis of Key Intermediate to the Formation of Selected Indolin-2-Ones Derivatives Incorporating Ultrasound and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Blend of Techniques, for Some Biological Activities and Molecular Docking Studies. Molecules, 25(5), 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25051118