Glycation and Oxidative Stress Increase Autoantibodies in the Elderly

Abstract

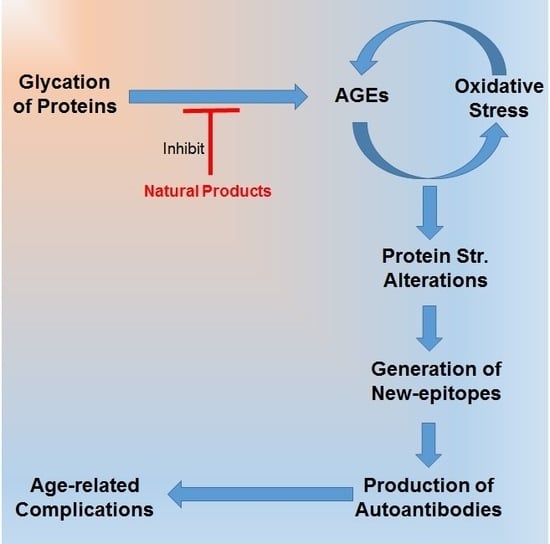

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Glycation of HSA

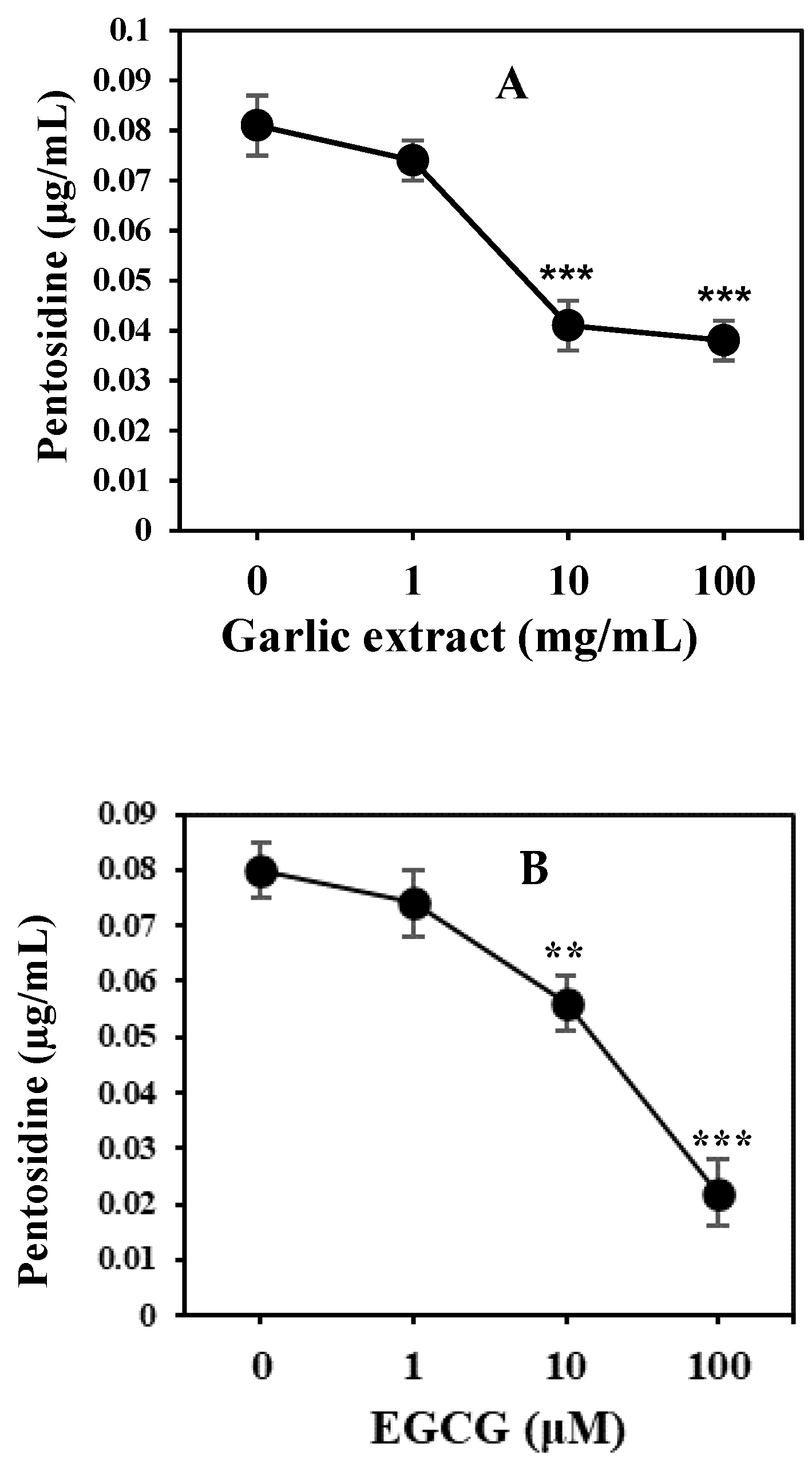

2.2. Natural Product and Their Derivatives Inhibit AGEs

2.3. Estimation of Oxidative Stress in Subjects

2.4. Serum Pentosidine Estimation

2.5. Proinflammatory Cytokines in Serum

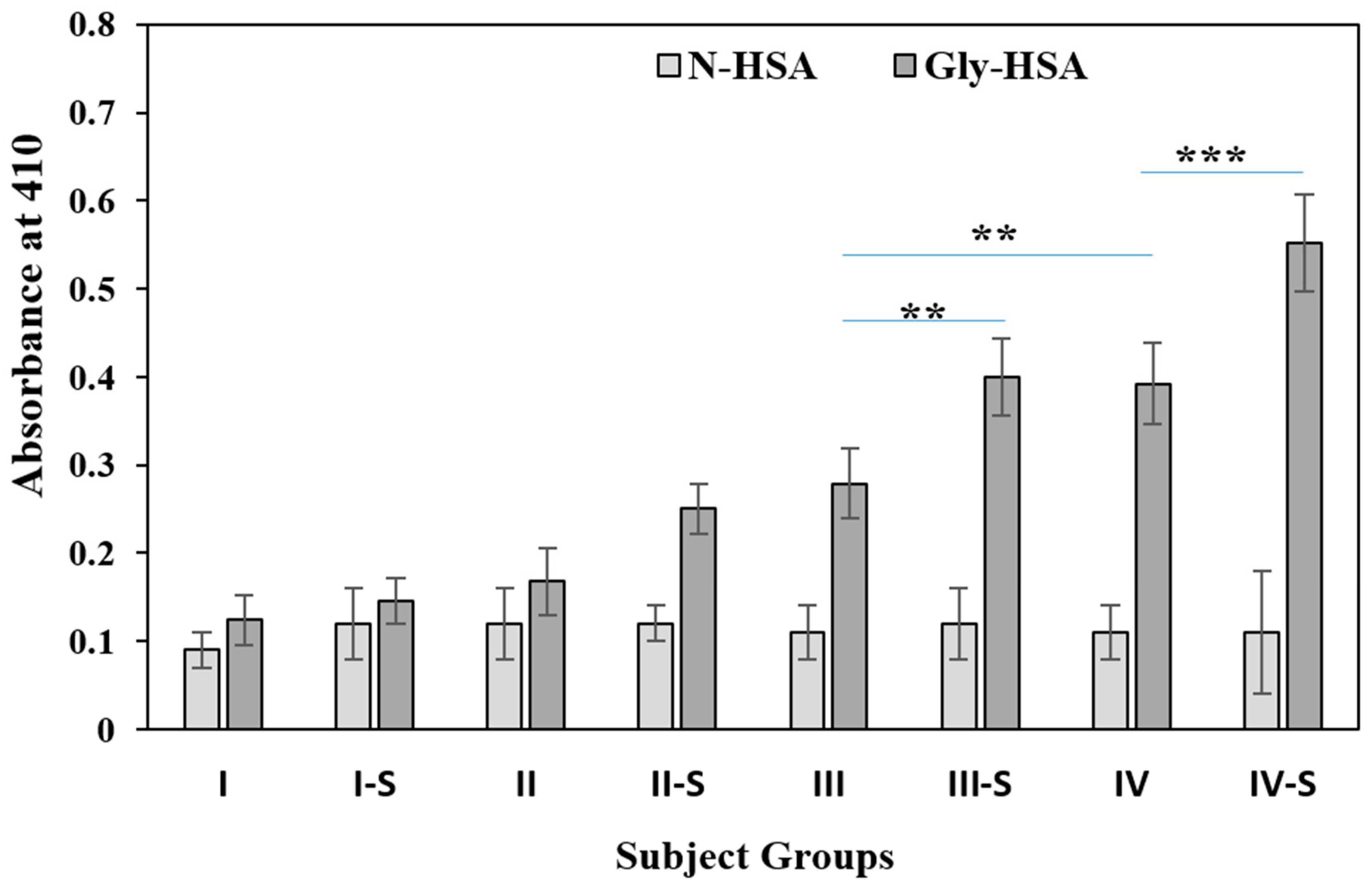

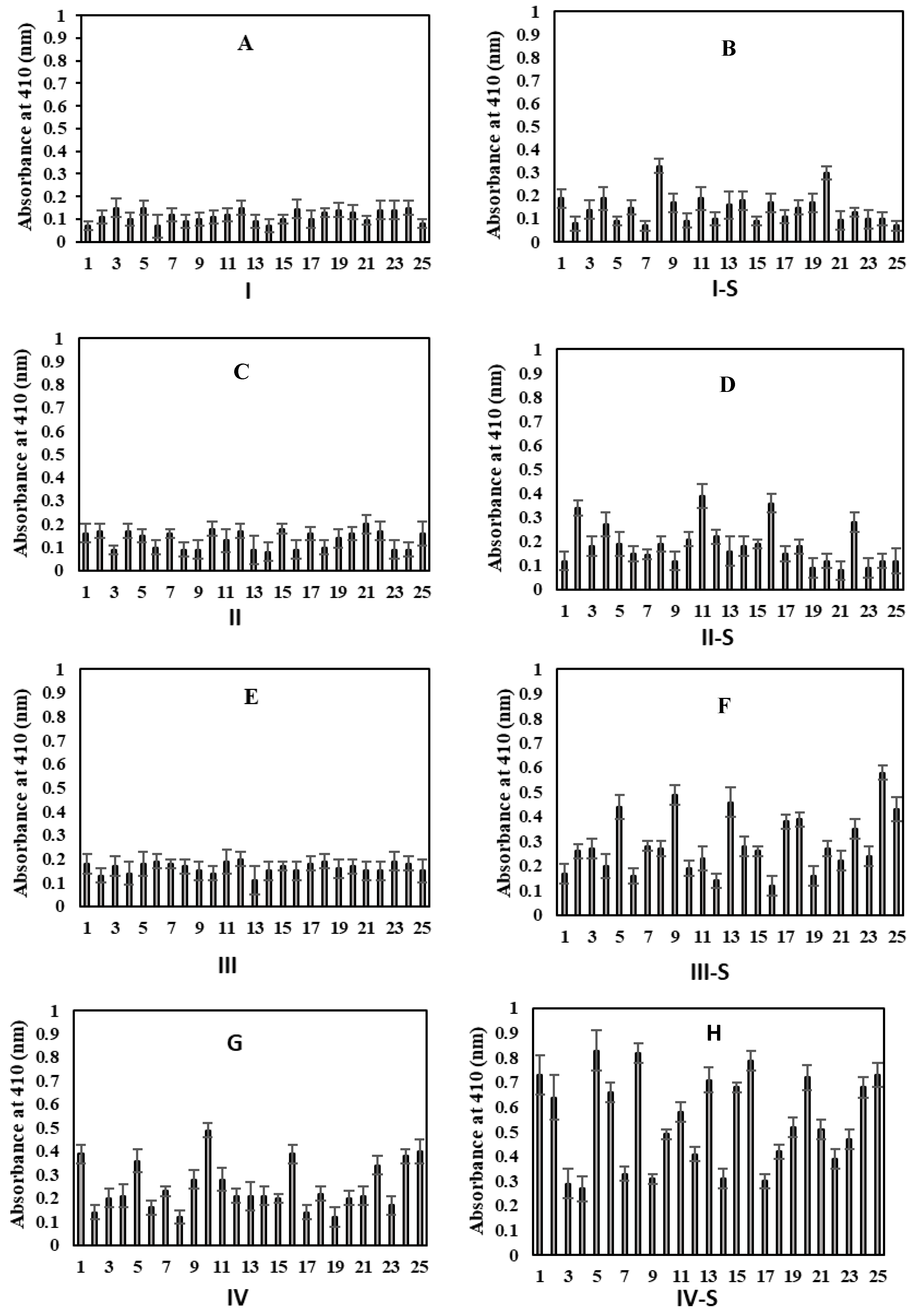

2.6. Detection of Circulating Gly-HSA-Abs by Direct ELISA

2.7. Inhibition ELISA of Serum Autoantibodies Against Gly-HSA

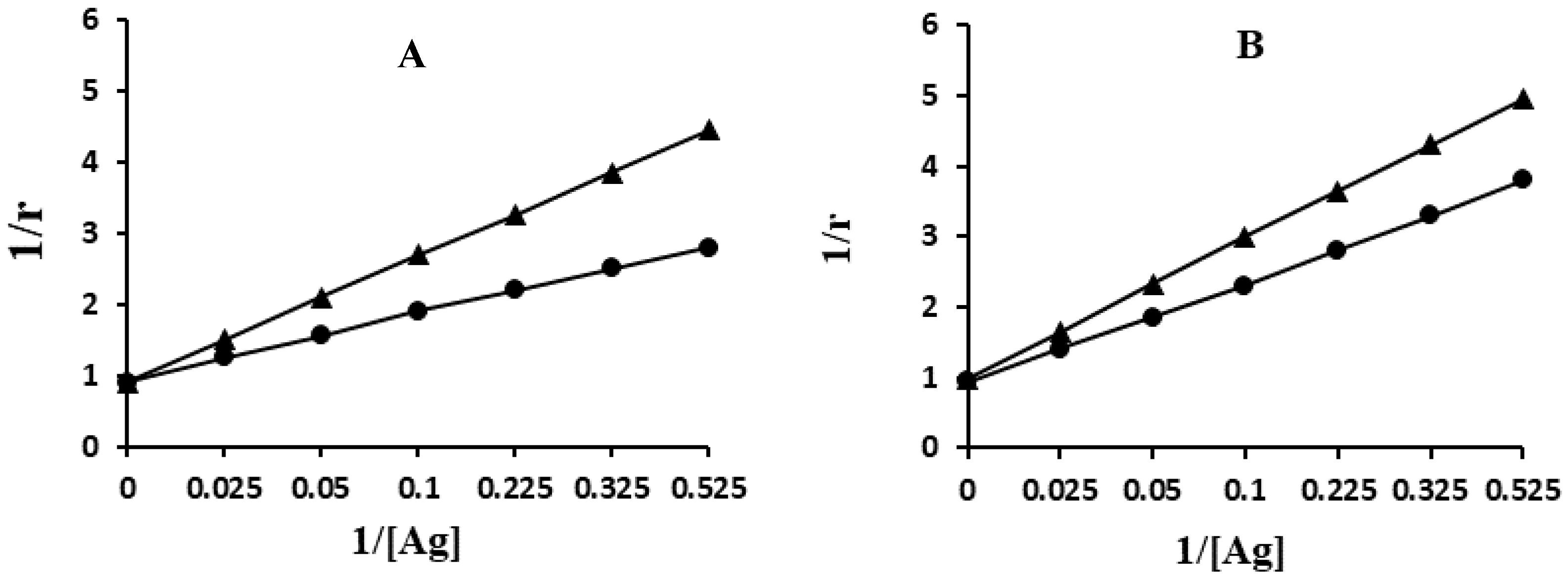

2.8. Quantification of Apparent Association Constant

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Subjects

4.2. Glycation

4.3. Detection of Ketoamines by NBT Reagent

4.4. Determination of Protein-Bound Carbonyl Contents

4.5. Assay of AGE-Fluorophores

4.6. Serum Pentosidine Detection by ELISA

4.7. Inhibition in AGE Formation by Natural Products

4.8. Cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 Estimation

4.9. Direct ELISA

4.10. Competition ELISA

4.11. Quantitation of Affinity of Antibodies from Elderly Individuals

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oeppen, J.; Vaupel, J.W. Demography: Broken limits to life expectancy. Science 2002, 296, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrucci, L.; Giallauria, F.; Guralnik, J.M. Epidemiology of aging. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 2008, 46, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics—Large Gains in Life Expectancy. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/world-health-statistics-2014/en/ (accessed on 15 May 2014).

- Blann, A. Blood tests and age-related changes in older people. Nurs. Times 2014, 110, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kutty, V.R.; Soman, C.R.; Joseph, A.; Kumar, K.V.; Pisharody, R. Random capillary blood sugar and coronary risk factors in a south Kerala population. J. Cardiovasc. Risk 2002, 9, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, L.N.; Korenda, L.; Meigs, J.B.; Driver, C.; Chamany, S.; Fox, C.S.; Sullivan, L.; D’agostino, R.B.; Nathan, D.M. Effect of aging on a1c levels in individuals without diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1991–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Liew, W.P.P.; Rahman, H.S. Antioxidant and oxidative stress: A mutual interplay in age-related diseases. Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction linked neurodegenerative disorders. Neurol. Res. 2017, 39, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baynes, J.W. The role of AGEs in aging: Causation or correlation. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, D.G.; Dunn, J.A.; Thorpe, S.R.; Lyons, T.J.; McCance, D.R.; Baynes, J.W. Accumulation of Maillard reaction products in skin collagen in diabetes and aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992, 663, 421–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verzijl, N.; DeGroot, J.; Oldehinkel, E.; Bank, R.A.; Thorpe, S.R.; Baynes, J.W.; Bayliss, M.T.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Lafeber, F.P.; Tekoppele, J.M. Age-related accumulation of Maillard reaction products in human articular cartilage collagen. Biochem. J. 2000, 350, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, J.; Bains, Y.; Guha, S.; Kahn, A.; Hall, D.; Bose, N.; Gugliucci, A.; Kapahi, P. The role of advanced glycation end products in aging and metabolic diseases. bridging association and causality. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simm, A.; Wagner, J.; Gursinsky, T.; Nass, N.; Friedrich, I.; Schinzel, R.; Czeslik, E.; Silber, R.E.; Scheubel, R.J. Advanced glycation endproducts: A biomarker for age as an outcome predictor after cardiac surgery? Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nass, N.; Bartling, B.; Santos, A.N.; Scheubel, R.J.; Börgermann, J.; Silber, R.E.; Simm, A. Advanced glycation end products, diabetes and aging. Z. Gerontol. Geriat. 2007, 40, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liggins, J.; Furth, A.J. Role of protein-bound carbonyl groups in the formation of advanced glycation end products. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1361, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Koppal, T.; Howard, B.; Subramaniam, R.; Hall, N.; Hensley, K.; Yatin, S.; Allen, K.; Aksenov, M.; Carney, J. Structural and functional changes in proteins induced by free radical-mediated oxidative stress and protective action of the antioxidants N-tert-butylalpha-phenylnitrone and vitamin E. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 854, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, Z.; Ljubica, S.; Turk, N.; Benko, B. Detection of autoantibodies against advanced glycation end products and AGE-immune complexes in serum of patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chim. Acta 2001, 303, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, H.; Shikata, K.; Hironaka, K.; Kushiro, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sugimoto, H.; Ota, Z.; Araki, N.; Horiuchi, S. Ultrastructure of nonenzymatically glycated mesangial matrix in diabetic nephropathy. Kid. Int. 1995, 48, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoussakis, M.N.; Tzioufas, A.G.; Silis, M.P.; Pange, P.J.; Goudevenos, J.; Moutsopoulos, H.M. High prevalence of anti-cardiolipin and other autoantibodies in a healthy elderly population. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1987, 69, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ansari, N.A.; Moinuddin; Alam., K.; Ali, A. Preferential recognition of Amadoririch lysine residues by serum antibodies in diabetes mellitus: Role of protein glycation in the disease process. Hum. Immunol. 2009, 70, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.D.; Schmidt, A.M.; Anderson, G.M.; Zhang, J.; Brett, J.; Zou, Y.S.; Pinsky, D.; Stern, D. Enhanced cellular oxidant stress by the interaction of advanced glycation end products with their receptors/binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 9889–9897. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Bartosz, G. Prevention of protein glycation by natural compounds. Molecules 2015, 20, 3309–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaratnarajah, A.; Jackson, A.H.D. The physiology of aging. Medicine 2017, 45, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.; Adams, R.J.; Brown, T.M.; Carnethon, M.; Dai, S.; De-Simone, G.; Ferguson, T.B.; Ford, E.; Furie, K.; Gillespie, C.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2010 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, e46–e215. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.W.A.; Rasheed, Z.; Khan, W.A.; Ali, R. Biochemical, biophysical and thermodynamic analysis of in vitro glycated human serum albumin. Biochemistry 2007, 72, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Curcio, F.; Bulli, G.; Aran, L.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, K.; Jung, T.; Grune, T.; Höhn, A. Accumulation of modified proteins and aggregate formation in aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 57C, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Ma, J.; Chen, F.; Wang, M. Naturally occurring inhibitors against the formation of advanced glycation end-products. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakata, Y.; Fujimaki, T.; Yamada, Y. Age related changes in clinical parameters and their associations with common complex diseases. Biomed. Rep. 2015, 3, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watad, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Adawi, M.; Amital, H.; Toubi, E.; Porat, B.S.; Shoenfeld, Y. Autoimmunity in the elderly: Insights from basic science and clinics—A mini-review. Gerontology 2017, 63, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wick, G.; Grubeck-Loebenstein, B. Primary and secondary alterations of immune reactivity in the elderly: Impact of dietary factors and disease. Immunol. Rev. 1997, 160, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinodan, T.; Kay, M.M.B. Age influence on the immune system. Adv. Immunol. 1980, 29, 287–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orosz, Z.; Csiszar, A.; Labinskyy, N.; Smith, K.; Kaminski, P.M.; Ferdinandy, P.; Wolin, M.S.; Rivera, A.; Ungvari, Z. Cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory alterations in the endothelial phenotype: Role of NAD(P)H oxidase activation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 292, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starke, R.M.; Thompson, J.W.; Ali, M.S.; Pascale, C.L.; Lege, A.M.; Ding, D.; Chalouhi, N.; Hasan, D.M.; Jabbour, P.; Owens, G.K.; et al. Cigarette smoke initiates oxidative stress-induced cellular phenotypic modulation leading to cerebral aneurysm pathogenesis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of micrograms quantity of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Furth, J.A. A microassay for protein glycation based on the periodate method. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 192, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.L.; Williams, J.; Stadtman, E.R.; Shacter, E. Carbonyl assays for determination of oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzym. 1994, 233, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Sanaka, T.; Funaki, T.; Tanaka, T.; Hoshi, S.; Niwayama, J.; Taitoh, T.; Nishimura, H.; Higuchi, C. Plasma pentosidine levels measured by a newly developed method using ELISA in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephron 2002, 91, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yamauchi, M.; Yano, S.; Sugimoto, T. Serum pentosidine levels are positively associated with the presence of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elista, A.; Slevin, M.; Rahman, K.; Ahmed, N. Aged garlic has more potent antiglycation and antioxidant properties compared to fresh garlic extract in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, C.; Raihan, M.; Sang, S.; Ahmedna, M. Green tea epigallocatechin 3-gallate alleviates hyperglycemia and reduces advanced glycation end products via nrf2 pathway in mice with high fat diet-induced obesity. Biomed. Pharm. 2017, 87, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, Z.; Anbazhagan, A.N.; Akhtar, N.; Ramamurthy, S.; Voss, F.R.; Haqqi, T.M. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits advanced glycation end product-induced expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and matrix metalloproteinase-13 in human chondrocytes. Arthritis Res. 2009, 11, R71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.W.A.; Qadrie, Z.L.; Khan, W.A. Antibodies against gluco-oxidatively modified human serum albumin detected in diabetes-associated complications. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 153, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alouffi, S.; Sherwani, S.; Al-Mogbel, M.S.; Sherwani, M.K.A.; Khan, M.W.A. Depression and smoking augment the production of circulating autoantibodies against glycated HSA in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 177, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.W.A.; Banga, K.; Mashal, S.N.; Khan, W.A. Detection of autoantibodies against reactive oxygen species modified glutamic acid decarboxylase-65 in type 1 diabetes associated complications. BMC Immunol. 2011, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surface glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors. |

| Parameters | N-HSA | Gly-HSA |

|---|---|---|

| Ketoamine (mol/mol of HSA) | 0.25 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.3 ** |

| Carbonyl content (mol/mg of HSA) | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 3.11 ± 0.4 *** |

| Pentosidine Fluorescence (AU) Exc. at 275 nm | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 247.5 ± 8.7 *** |

| Serum Pentosidine (µg/mL) ELISA method | 0.0092 ± 0.0004 | 0.0863 ± 0.012 ** |

| Groups (Age in Years) n = Subjects | Sex M/F | Fasting Blood Glucose (mg/dL) | HbA1C (%) | Smoking Duration (years ± SD) | Serum Pentosidine (µg/mL ± SD) | Carbonyl Content (nmol/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (21–40) n = 25 | 16/09 | 83.0 ± 7.1 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | ― | 0.0259 ± 0.0021 | 0.78 ± 0.15 |

| I-S (21–40) n = 25 | 15/10 | 85.1 ± 7.1 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 5.1 | 0.0264 ± 0.0024 | 0.93 ± 0.14 |

| II (41–60) n = 25 | 16/09 | 90.3 ± 8.5 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | ― | 0.0262 ± 0.0030 | 0.84 ± 0.14 |

| II-S (41–60) n = 25 | 16/09 | 94.2 ± 8.5 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 16.9 ± 7.7 | 0.0269 ± 0.0029 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| III (61–80) n = 25 | 15/10 | 94.8 ± 7.3 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | ― | 0.0265 ± 0.0022 | 0.92 ± 0.22 |

| III-S (61–80) n = 25 | 15/10 | 98.8 ± 8.3 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 19.9 ± 9.7 | 0.0285 ± 0.0031 * | 1.64 ± 0.4 ** |

| IV (> 80) n = 25 | 25/25 | 106 ± 8.5 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | ― | 0.0271 ± 0.0027 | 1.21 ± 0.3 |

| IV-S (> 80) n = 25 | 25/25 | 118 ± 9.5 | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 29.9 ± 11.7 | 0.0321 ± 0.0029 * | 2.42 ± 0.5 *** |

| Groups | IL-6 (pg/mL) | IL-1β (pg/mL) | Maximum Percent Inhibition at 20 µg/mL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-HSA-Ab | Gly-HSA-Ab | |||

| I | 4.9 ± 0.66 | 1.1 ± 0.26 | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 7.8 ± 2.3 |

| I-S | 4.7 ± 0.56 | 0.99 ± 0.19 | 7.9 ± 2.6 | 9.4 ± 2.4 |

| II | 5.2 ± 0.67 | 1.16 ± 0.21 | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 12.4 ± 3.1 |

| II-S | 5.1 ± 0.61 | 1.21 ± 0.23 | 7.9 ± 2.2 | 19.4 ± 4.1 |

| III | 5.3 ± 0.65 | 1.18 ± 0.25 | 8.8 ± 1.8 | 21.1 ± 3.3 |

| III-S | 6.4 ± 0.69 * | 1.28 ± 0.28 | 8.9 ± 1.8 | 33.1 ± 4.0 * |

| IV | 5.2 ± 0.54 | 1.20 ± 0.19 | 9.3 ± 2.1 | 29.3 ± 4.3 |

| IV-S | 7.2 ± 0.65 ** | 1.62 ± 0.21 * | 9.1 ± 2.1 | 51.3 ± 4.1 *** |

| I | I-S | II | II-S | III | III-S | IV | IV-S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient (r) | |||||||||

| Gly-HSA-Abs | FBG | −0.12 | 0.20 | 0.92 *** | 0.99 *** | 0.90 *** | 0.98 *** | 0.95 *** | 0.98 *** |

| Pentosidine | 0.79 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.90 *** | 0.99 *** | 0.96 *** | 0.99 *** | 0.96 *** | 0.99 *** | |

| Carbonyl content | 0.72 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.93 *** | 0.93 *** | 0.98 *** | 0.99 *** | 0.97 *** | 0.97 *** | |

| IL-6 | 0.56 * | 0.48 * | 0.92 *** | 0.98 *** | 0.96 *** | 0.82 ** | 0.94 *** | 0.90 *** | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.W.A.; Al Otaibi, A.; Sherwani, S.; Khan, W.A.; Alshammari, E.M.; Al-Zahrani, S.A.; Saleem, M.; Khan, S.N.; Alouffi, S. Glycation and Oxidative Stress Increase Autoantibodies in the Elderly. Molecules 2020, 25, 3675. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163675

Khan MWA, Al Otaibi A, Sherwani S, Khan WA, Alshammari EM, Al-Zahrani SA, Saleem M, Khan SN, Alouffi S. Glycation and Oxidative Stress Increase Autoantibodies in the Elderly. Molecules. 2020; 25(16):3675. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163675

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Mohd W.A., Ahmed Al Otaibi, Subuhi Sherwani, Wahid A. Khan, Eida M. Alshammari, Salma A. Al-Zahrani, Mohd Saleem, Shahper N. Khan, and Sultan Alouffi. 2020. "Glycation and Oxidative Stress Increase Autoantibodies in the Elderly" Molecules 25, no. 16: 3675. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163675

APA StyleKhan, M. W. A., Al Otaibi, A., Sherwani, S., Khan, W. A., Alshammari, E. M., Al-Zahrani, S. A., Saleem, M., Khan, S. N., & Alouffi, S. (2020). Glycation and Oxidative Stress Increase Autoantibodies in the Elderly. Molecules, 25(16), 3675. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163675