Assembling Polyiodides and Iodobismuthates Using a Template Effect of a Cyclic Diammonium Cation and Formation of a Low-Gap Hybrid Iodobismuthate with High Thermal Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

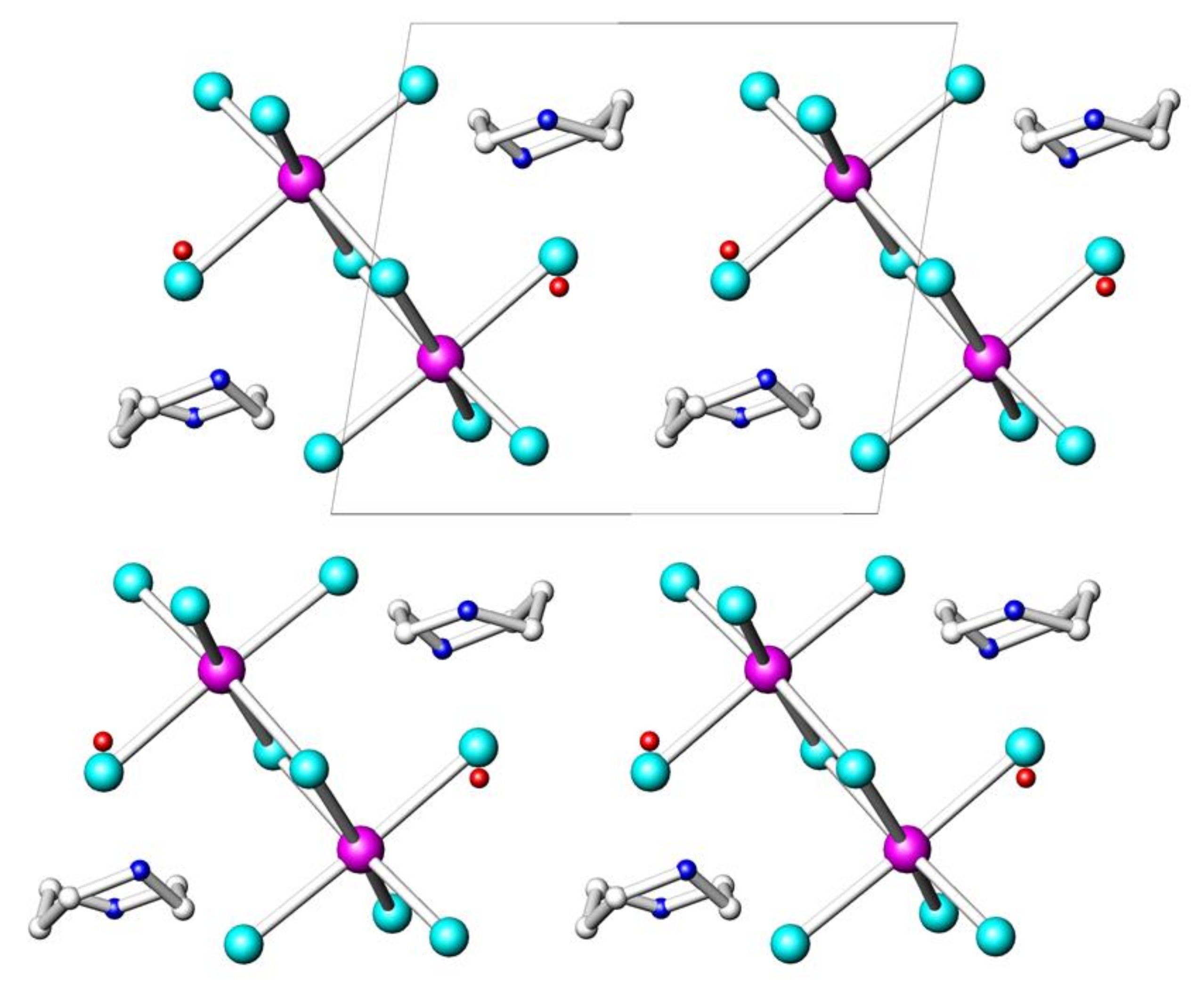

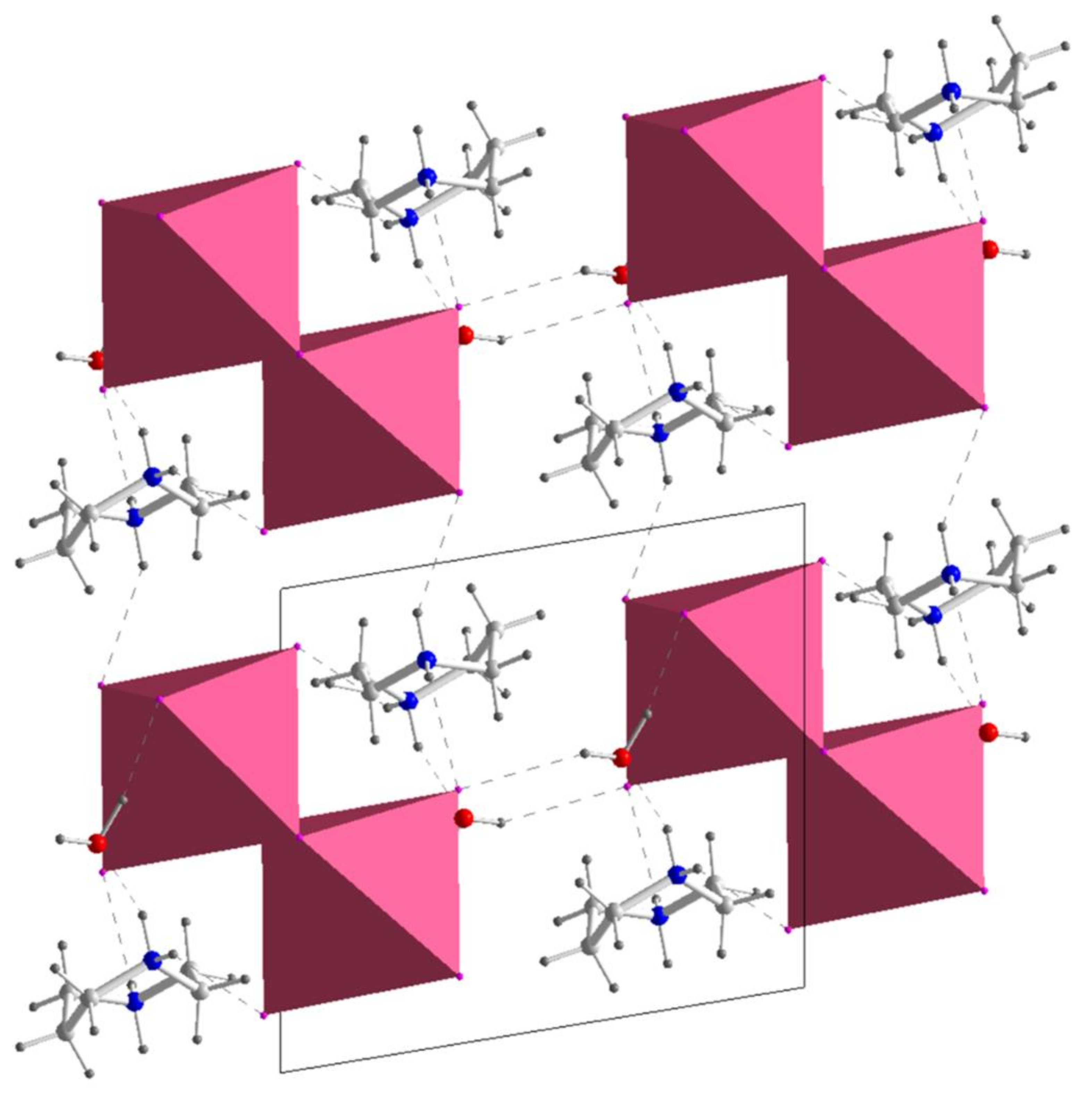

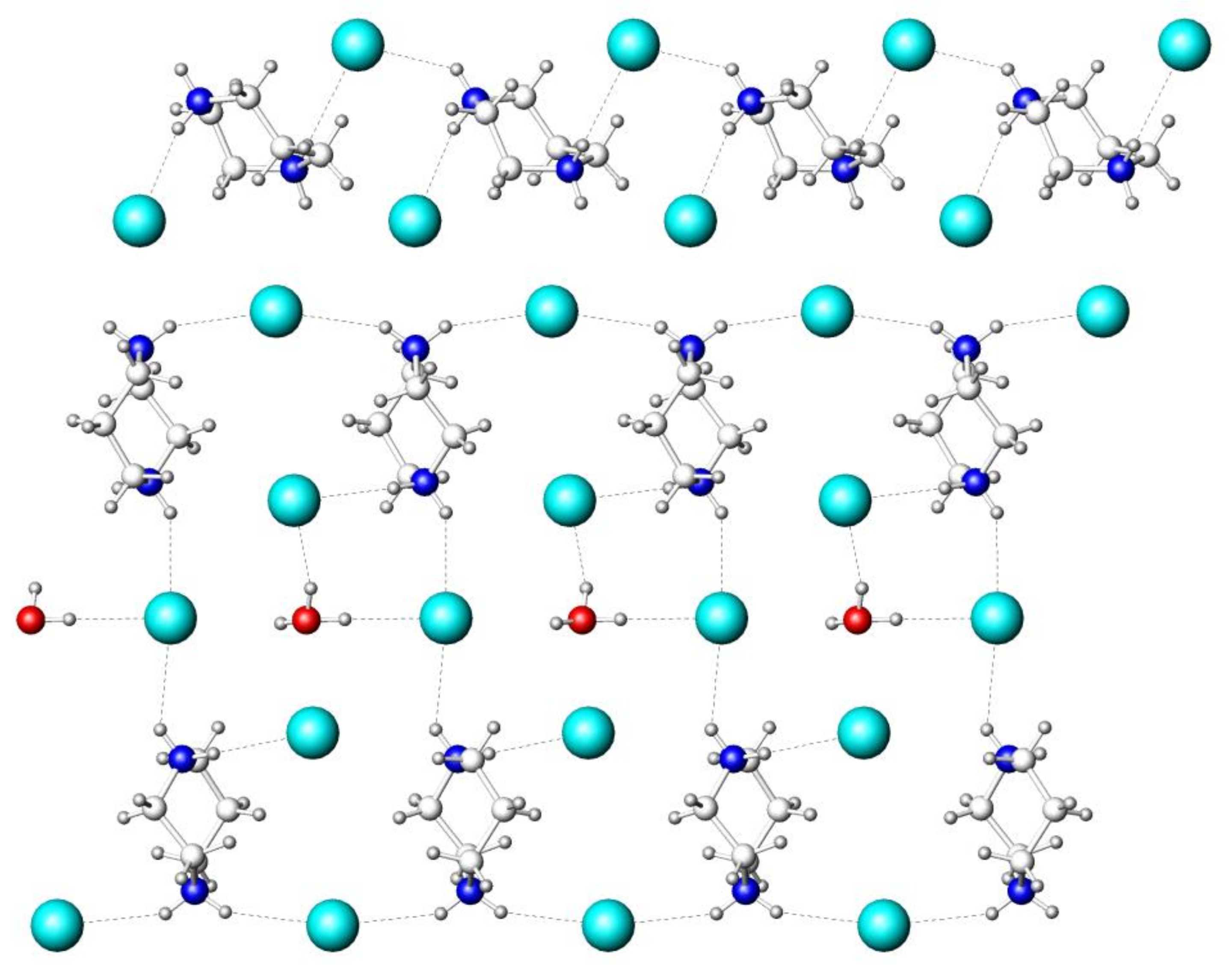

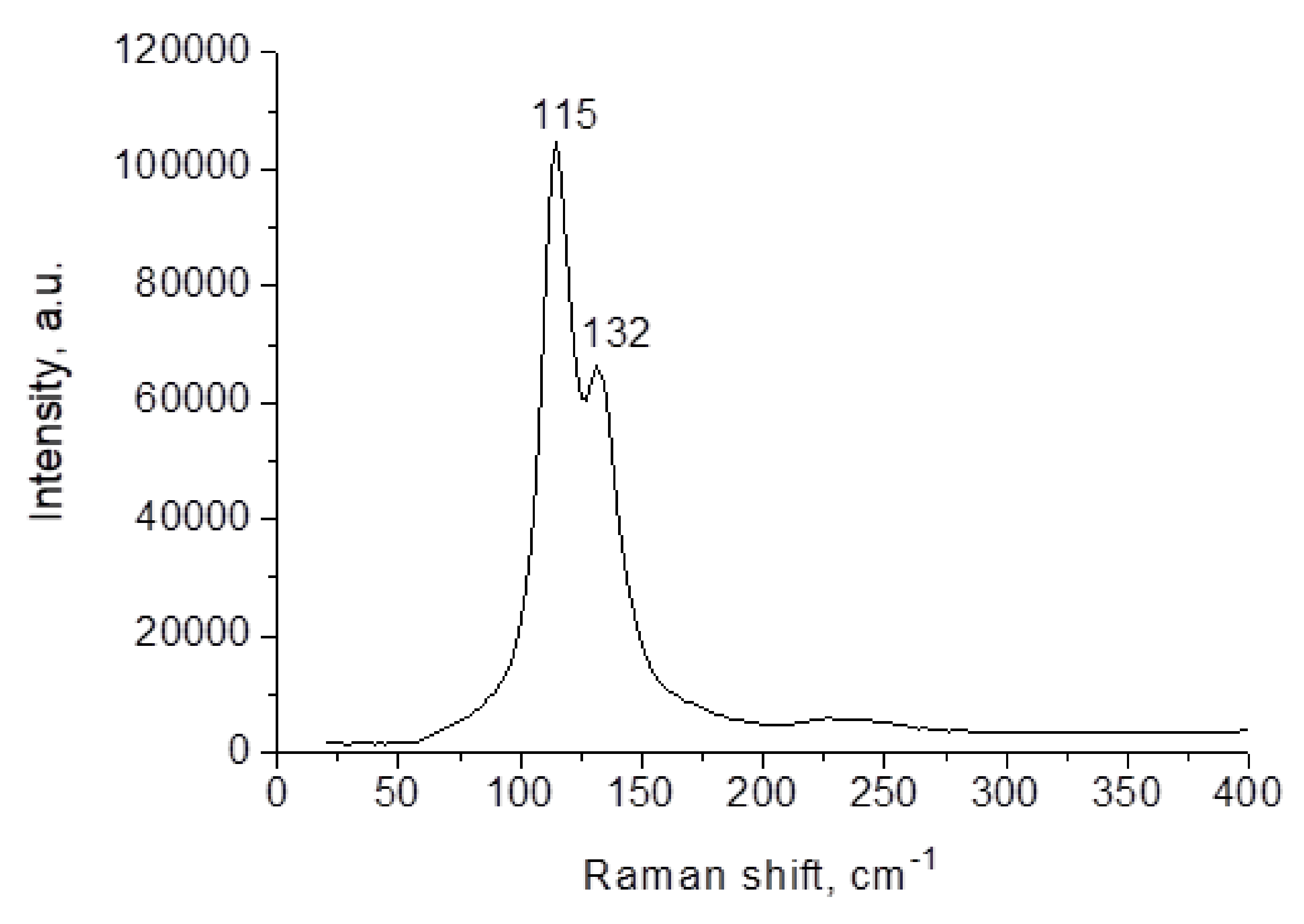

2. Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (PXRD)

3.3. Crystal Structure Determination

3.4. Thermal Analysis

3.5. Raman Spectroscopy

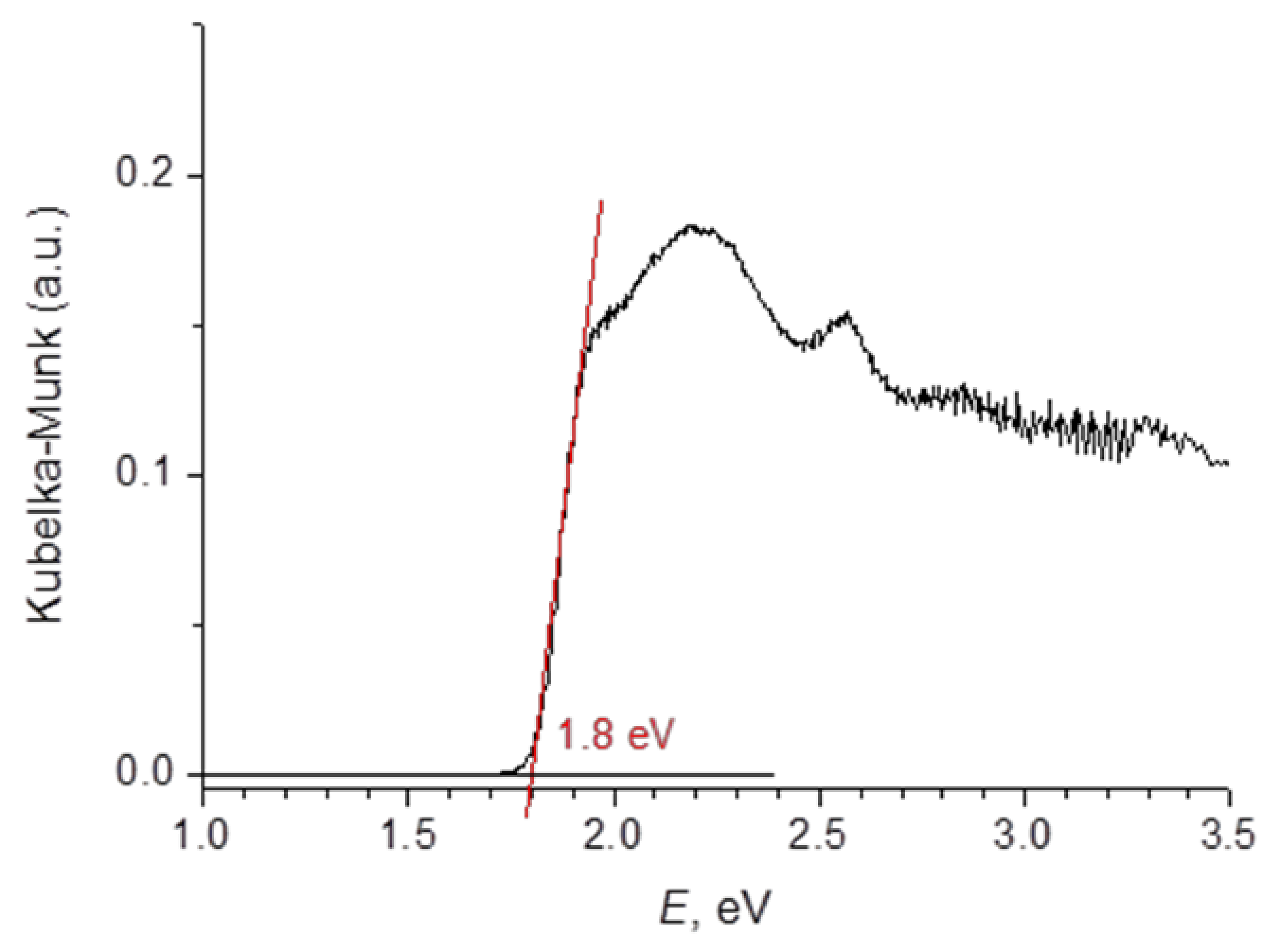

3.6. Optical Spectroscopy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruck, M. In My Element: Bismuth. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberger, N.; Massa, W.; Dehnen, S. Polybismuthide Anions as Ligands: The Homoleptic Complex [(Bi7)Cd(Bi7)]4− and the Ternary Cluster [(Bi6)Zn3(TlBi5)]4−. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3222–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiz, A.; Lê Anh, M.; Kaiser, M.; Rasche, B.; Herrmannsdorfer, T.; Doert, T.; Ruck, M. Optimized Synthesis of the Bismuth Subiodides BimI4 (m = 4, 14, 16, 18) and the Electronic Properties of Bi14I4 and Bi18I4. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 47, 5609–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, M.F.; Isaeva, A.; Frey, C.; Ruck, M. [Ru(Bi8)2]6+–A Cluster in a Highly Disordered Crystal Structure is the Key to the Understanding of the Coordination Chemistry of Bismuth Polycations. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2013, 639, 2401–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranov, A.I.; Kloo, L.; Olenev, A.V.; Popovkin, B.A.; Romanenko, A.I.; Shevelkov, A.V. Unique Metallic Wires ∞1Ni8Bi8S in a Novel Quasi-1D Compound. Synthesis, Crystal and Electronic Structure, and Properties of Ni8Bi8SI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 12375–12379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikarev, E.V.; Popovkin, B.A.; Shevelkov, A.V. The crystal structure of Bi14I4 condensed bismuth clusters. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1992, 612, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schnering, H.-G.; Benda, H.V.; Kalveram, C. Wismutmonojodid BiJ, eine Verbindung mit Bi(O) und Bi(II). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1978, 438, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.M.; Corbett, J.D. Bismuth(I) in the solid state. The crystal structure of (Bi+)(Bi95+)(HfCl62–)3. J. Chem. Soc. D Chem. Commun. 1971, 9, 422–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Y.; Huang, W. Lead-Free Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Perovskites for Photovoltaic Applications: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganose, A.M.; Savory, C.N.; Scanlon, D.O. Beyond methylammonium lead iodide: Prospects for the emergent field of ns2 containing solar absorbers. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroyuk, O. Lead-free hybrid perovskites for photovoltaics. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 2209–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Kim, M.; Jung, S.; Kim, C.S.; Park, J.; Song, A.; Chung, K.-B.; Jin, S.-H.; Lee, J.H.; Song, M. Enhanced efficiency in lead-free bismuth iodide with post treatment based on a hole-conductor-free perovskite solar cell. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 6283–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-Q.; Hui, H.-Y.; Lin, W.-Q.; Wen, H.-Q.; Yang, D.-S.; Feng, G.-D. Crystal and Band-Gap Engineering of One-Dimensional Antimony/Bismuth-Based Organic–Inorganic Hybrids. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 16346–16353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyfantis, G.C.; Ioannou, A.; Barkaoui, H.; Abid, Y.; Psycharis, V.; Raptopoulou, C.P.; Mousdis, G.A. Hybrid halobismuthates as prospective light-harvesting materials: Synthesis, crystal, optical properties and electronic structure. Polyhedron 2020, 175, 114180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Zou, B. Bismuth Halide Perovskite-Like Materials: Current Opportunities and Challenges. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1612–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, N.; Louvain, N.; Bi, W. Structural diversity and retro-crystal engineering analysis of iodometalate hybrids. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adonin, S.A.; Sokolov, M.N.; Fedin, V.P. Polynuclear halide complexes of Bi(III): From structural diversity to new properties. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 312, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, M.; Kohler, D.; Ruck, M. A Water Sensitive Hydrate: The Bis-Catena Complex Salt [Mn(H2O)6][BiI4]2·2H2O. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2010, 636, 1513–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelovik, N.A.; Mironov, A.V.; Bykov, M.A.; Kuznetsov, A.N.; Grigorieva, A.V.; Wei, Z.; Dikarev, E.V.; Shevelkov, A.V. Iodobismuthates Containing One-Dimensional BiI4– Anions as Prospective Light-Harvesting Materials: Synthesis, Crystal and Electronic Structure, and Optical Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 4132–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelovik, N.A.; Shestimerova, T.A.; Bykov, M.A.; Wei, Z.; Dikarev, E.V.; Shevelkov, A.V. Synthesis, structure, and properties of LnBiI6·13H2O (Ln = La, Nd). Russ. Chem. Bull. Int. Ed. 2017, 66, 1196–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Pan, M.; Johansson, M.B.; Johansson, E.M.J. High Photon-to-Current Conversion in Solar Cells Based on Light-Absorbing Silver Bismuth Iodide. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 2592–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.M.; Phuyal, D.; Davies, M.L.; Li, M.; Philipp, B.; De Castro, C.; Qiu, Z.; Kim, J.; Watson, T.; Tsoi, W.C.; et al. An effective approach of vapour assisted morphological tailoring for reducing metal defect sites in lead-free, (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 bismuth-based perovskite solar cells for improved performance and long-term stability. Nano Energy 2018, 49, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Le Mercier, T.; Madec, M.B.; Pauporté, T. AgBi2I7 layers with controlled surface morphology for solar cells with improved charge collection. Mater. Lett. 2018, 221, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashadieva, L.F.; Aliev, Z.S.; Shevelkov, A.V.; Babanly, M.B. Experimental investigation of the Ag–Bi–I ternary system and thermodynamic properties of the ternary phases. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 551, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Xia, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Lei, B.; Gao, Y. High-Quality (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 Film-Based Solar Cells: Pushing Efficiency up to 1.64%. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 4300–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazoki, M.; Edvinsson, T. Metal replacement in perovskite solar cell materials: Chemical bonding effects and optoelectronic properties. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2018, 2, 1430–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, H.C.; Whitehead, G.F.S.; Dyer, M.S.; Zanella, M.; Manning, T.D.; Pitcher, M.J.; Whittles, T.J.; Dhanak, V.R.; Alaria, J.; Claridge, J.B.; et al. AgBiI4 as a Lead-Free Solar Absorber with Potential Application in Photovoltaics. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 1538–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestimerova, T.A.; Yelavik, N.A.; Mironov, A.V.; Kuznetsov, A.N.; Bykov, M.A.; Grigorieva, A.V.; Shevelkov, A.V. From Isolated Anions to Polymer Structures through Linking with I2: Synthesis, Structure, and Properties of Two Complex Bismuth(III) Iodine Iodides. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4077–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, A.J.; Fabini, D.H.; Evans, H.A.; Hébert, C.-A.; Smock, S.R.; Hu, J.; Wang, H.; Zwanziger, J.W.; Chabinyc, M.L.; Seshadri, R. Crystal and Electronic Structures of Complex Bismuth Iodides A3Bi2I9 (A = K, Rb, Cs) Related to Perovskite: Aiding the Rational Design of Photovoltaics. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 7137–7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Han, S.; Wu, Z.; Luo, J. Triiodide-induced band-edge reconstruction of a lead-free perovskite-derivative hybrid for strong light absorption. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 4081–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Kou, B.; Peng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yao, Y.; Dey, D.; Lia, L.; Luo, J. Rational design of a triiodide-intercalated dielectric-switching hybrid for visible-light absorption. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 12170–12174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, V.Y.; Ilyukhin, A.B.; Sadovnikov, A.A.; Birin, K.P.; Simonenko, N.P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Kozyukhin, S.A. Bis (4-cyano-1-pyridino) pentane halobismuthates. Light-harvesting material with an optical band gap of 1.59 eV. Mendeleev Commun. 2017, 27, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, V.Y.; Ilyukhin, A.B.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Smol’yakov, A.F.; Kozyukhin, S.A. Black hybrid iodobismuthate containing linear anionic chains. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 6354–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Nichol, G.S.; Morrison, C.A.; Han, H.; Hu, Y.; Robertson, N. Extending lead-free hybrid photovoltaic materials to new structures: Thiazolium, aminothiazolium and imidazolium iodobismuthates. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 7050–7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Weng, Y.-G.; Tang, Z.-Z.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Dai, J. Intracation and interanion–cation charge-transfer properties of tetrathiafulvalene-bismuth-halide hybrids. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 11113–11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnhardt, N.; Luy, J.-N.; Szabo, M.; Wende, M.; Tonner, R.; Heine, J. Synthesis of a two-dimensional organic–inorganic bismuth iodide metalate through in situ formation of iminium cations. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 14725–14728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shestimerova, T.A.; Mironov, A.V.; Bykov, M.A.; Starichenkova, E.D.; Kuznetsov, A.N.; Grigorieva, A.V.; Shevelkov, A.V. Reversal Topotactic Removal of Acetone from (HMTH)2BiI5·(CH3)2C=O. Accompanied by Rearrangement of Weak Bonds, from 1D to 3D Patterns. Cryst. Growth Design 2020, 20, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestimerova, T.A.; Golubev, N.A.; Yelavik, N.A.; Bykov, M.A.; Grigorieva, A.V.; Wei, Z.; Dikarev, E.V.; Shevelkov, A.V. Role of I2 Molecules and Weak Interactions in Supramolecular Assembling of Pseudo-Three-Dimensional Hybrid Bismuth Polyiodides: Synthesis, Structure, and Optical Properties of Phenylenediammonium Polyiodobismuthate(III). Cryst. Growth Design 2018, 18, 2572–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Hu, Y.; Morrison, C.A.; Wu, W.; Hana, H.; Robertson, N. Lead-free pseudo-three-dimensional organic–inorganic iodobismuthates for photovoltaic applications. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2017, 1, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebing, P.; Stein, F.; Hilfert, L.; Lorenz, V.; Oliynyk, K.; Edelmann, F.T. Synthesis and structural investigation of brightly colored organoammonium violurates. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2019, 645, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennington, A.J.; Weller, M.T. Synthesis and structure of pseudo-three-dimensional hybrid iodobismuthate semiconductors. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 17974–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adonin, S.A.; Gorokh, I.D.; Novikov, A.S.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Yushina, I.V.; Sokolov, M.N.; Fedin, V.P. Halobismuthates with halopyridinium cations: Appearance or non-appearance of unusual colouring. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 7766–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterova, O.V.; Petrusenko, S.R.; Dyakonenko, V.V.; Shishkin, O.V.; Linert, W. A three-dimensional framework of bis [tris(ethylenediamine)zinc] tetraiodocadmate diiodide assisted by N—H⋯I hydrogen bonds. Acta Crystallogr. C 2006, 62, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigui, A.; Boughzala, H.; Driss, A.; Abid, Y. The one-dimensional organic-inorganic hybrid: catena-poly[bis[1-(3-ammoniopropyl)-1H-imidazolium] [[iodidoplumbate(II)]-tri-μ-iodido-plumbate(II)-tri-μ-iodido-[iodidoplumbate(II)]-di-μ-iodido]]. Acta Crystallogr. E 2011, 67, 458–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, S. A cartography of the van der Waals territories. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 8617–8636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-H.; Albrecht, R.; Doert, T.; Ruck, M. The Water-Rich Iodidobismuthate (H3O)Rb3BiI7·4H2O. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2019, 645, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, P.H.; Kloo, L. Synthesis, Structure, and Bonding in Polyiodide and Metal Iodide–Iodine Systems. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1649–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinkina, E.V.; Mavrin, B.N.; Albov, D.V.; Kravchenko, V.V.; Zaitseva, M.G. Polyiodide amide complexes of transition metals: Structures and Raman spectra. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2009, 35, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestimerova, T.A.; Bykov, M.A.; Wei, Z.; Dikarev, E.V.; Shevelkov, A.V. Crystal structure and two-level supramolecular organization of glycinium triiodide. Russ. Chem. Bull. Int. Ed. 2019, 68, 520–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yushina, I.; Tarasova, N.; Kim, D.; Sharutin, V.; Bartashevich, E. Noncovalent Bonds, Spectral and Thermal Properties of Substituted Thiazolo[2,3-b][1,3]thiazinium Triiodides. Crystals 2019, 9, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, W.H.; Mozur, E.M.; Moseley, I.P.; Ahn, H.; Neilson, J.R. Hybrid Charge-Transfer Semiconductors: (C7H7)SbI4, (C7H7)BiI4, and Their Halide Congeners. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 5818–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-P.; Feng, Q.-Y.; Wei, Y.-L.; Gao, Z.-Y.; Wang, Z.-W.; Wang, Y.-M. Three Iodobismuthates Hybrids Displaying Mono-nuclear, Dimer and 1-D Arrangements Templated by 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane Derivatives: Semiconductor and Photocurrent Response Properties. J. Clust. Sci. 2018, 29, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-G. Organic/Bismuth Iodides Hybrids: Structural Perturbation of Substitutes and Their Photocurrent Response Properties. J. Clust. Sci. 2017, 28, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefler, S.F.; Rath, T.; Fischer, R.; Latal, C.; Hippler, D.; Koliogiorgos, A.; Galanakis, I.; Bruno, A.; Fian, A.; Dimopoulos, T.; et al. A zero-dimensional mixed-anion hybrid halogenobismuthate (III) semiconductor: Structural, optical, and photovoltaic properties. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 10576–10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, M.C.; Camalli, M.; Carrozzini, B.; Cascarano, G.; Giacovazzo, C.; Polidori, G.; Spagna, R. SIR2002: The program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2003, 36, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petricek, V.; Dusek, M.; Palatinus, L. Jana2000. In Structure Determination Software Programs; Institute of Physics: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELX97. In Program for the Solution and Refinement of Crystal Structures; University of Gottingen: Gottingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- SAINT, Version 8.38A; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2019.

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. J. Appl. Cryst. 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, P.; Munk, F. Ein Beitrag zur Optik der Farbanstriche (Contribution to the optic of paint). Z. Tech. Phys. (Leipzig) 1931, 12, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Fedeli, P.; Gazza, F.; Calestani, D.; Ferro, P.; Besagni, T.; Zappettini, A.; Calestani, G.; Marchi, E.; Ceroni, P.; Mosca, R. Influence of the synthetic procedures on the structural and optical properties of mixed-halide (Br, I) perovskite films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 21304–21313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available. |

| Parameters | (HpipeH2)2Bi2I10·2H2O | (HpipeH2)I(I3) | (HpipeH2)3I6·H2O | (HpipeH2)3(H3O)I7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum Formula | C5H16BiI5N2O | C5H14I4N2 | C15H44I6N6O | C15H45I7N6O |

| Crystal system | triclinic | orthorhombic | orthorhombic | monoclinic |

| Space Group | P-1 (№ 2) | Pbca (№ 61) | P212121 (№ 19) | P21/c (№ 14) |

| a, Å | 8.3972 (17) | 10.5196 (3) | 10.3687 (4) | 24.3883 (14) |

| b, Å | 10.4764 (16) | 12.5020 (4) | 12.1510 (3) | 10.0774 (6) |

| c, Å | 11.0662 (18) | 21.5362 (5) | 25.3425 (6) | 13.6539 (8) |

| α,° | 95.928 (13) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β,° | 98.804 (15) | 90 | 90 | 99.6360 (10) |

| γ,° | 108.262 (14) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| V, Å3 | 901.7 (3) | 2832.36 (14) | 3192.90 (16) | 3308.4 (3) |

| Z | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| dcalc | 3.549 | 2.860 | 2.259 | 2.437 |

| Radiation/wavelength | AgKα/0.56083 | CuKα/1.54186 | CuKα/1.54186 | MoKα/0.71073 |

| Temperature, K | 295 (2) | 293 (2) | 293 (2) | 100 (2) |

| Crystal form | block | block | plate | plate |

| Crystal size, mm | 0.38 × 0.26 × 0.18 | 0.25 × 0.2 × 0.15 | 0.1 × 0.05 × 0.03 | 0.16 × 0.09 × 0.02 |

| Absorption correction | psi-scan | multi-scan | multi-scan | multi-scan |

| θ range (data collection) | 2.03–24.96 | 4.106–72.703 | 3.49–72.93 | 2.743–29.414 |

| Range of h, k, l | –11→h→11; –15→k→15; 0→l→16 | –12→h→13; –7→k→12; –25→l→26 | –12→h→12; 0→k→15; 0→l→31 | –33→h→33; –13→k→13; –18→l→18 |

| Rint | 0.0157 | 0.1176 | 0.1467 | 0.0459 |

| R/Rw | 0.0310/0.0607 1 | 0.0399/0.1150 1 | 0.0475/0.1203 1 | 0.0299/0.0531 2 |

| GoF | 1.09 | 0.992 | 0.899 | 1.079 |

| No. of params./reflections | 126/4987 | 116/2806 | 260/6313 | 271/9143 |

| Δρmax (e/Å-3) positive/negative | 0.89/–0.72 | 0.93/–1.48 | 1.19/–0.68 | 1.132/–1.477 |

| Atoms | Distance, Å | Atoms | Angle, ° |

|---|---|---|---|

| (HpipeH2)2Bi2I10·2H2O | |||

| Bi1–I1 –I1 –I2 –I3 –I4 –I5 | 3.1459 (10) 3.1947 (17) 3.1227 (10) 3.0345 (9) 3.0342 (10) 2.9750 (16) | I1—Bi1—I1 I1—Bi1—I2 I1—Bi1—I3 I1—Bi1—I4 I1—Bi1—I5 I1—Bi1—I5 I2—Bi1—I3 I2—Bi1—I4 I2—Bi1—I5 I3—Bi1—I4 I3—Bi1—I5 I4—Bi1—I5 | 86.23 (2) 88.96 (2) 87.03 (2) 92.07 (2) 87.57 (2) 175.912 (18) 91.10 (2) 85.07 (2) 171.09 (2) 174.427 (19) 87.81 (2) 94.69 (2) 90.90 (2) × 2 90.86 (2) 97.70 (2) |

| (HpipeH2)I(I3) | |||

| I1–I3 | 2.8679 (8) | I3—I1—I4 | 178.82 (2) |

| I1–I4 | 2.9651 (8) | ||

| D–H···A | d(H···A), Å | d(D···A), Å | angle (D–H···A), ° |

|---|---|---|---|

| (HpipeH2)2Bi2I10 | |||

| N1–H12···I2 | 2.79 | 3.543 (8) | 139.5 |

| N5–H52···I3 | 2.83 | 3.577 (6) | 139.5 |

| N1–H12···I4 | 2.78 | 3.612 (7) | 150.3 |

| N5–H51···O1 | 1.95 | 2.840 (10) | 161.2 |

| O1–H1···I5 | 2.79 (9) | 3.725 (8) | 165 (8) |

| (HpipeH2)I(I3) | |||

| N2–H20···I2 | 2.50 (10) | 3.532 (7) | 165 (10) |

| N2–H22···I4 | 2.56 (19) | 3.551 (7) | 149 (11) |

| N1–H11···I2 | 2.80 (11) | 3.570 (6) | 124 (5) |

| N1–H12···I2 | 2.44 (10) | 3.504 (7) | 168 (8) |

| (HpipeH2)3I6·H2O | |||

| N1–H1A···I3 | 2.637 | 3.520 (11) | 167.3 |

| N1–H1B···I1 | 2.720 | 3.480 (10) | 142.9 |

| N2–H2A···I2 | 2.783 | 3.533 (10) | 141.7 |

| N2–H2B···I1 | 2.711 | 3.517 (10) | 149.5 |

| N3–H3A···I6 | 2.863 | 3.606 (11) | 140.9 |

| N3–H3B···O1 | 1.880 | 2.772 (14) | 170.8 |

| N4–H4A···I1 | 2.832 | 3.577 (10) | 141.0 |

| N4–H4B···I2 | 2.733 | 3.510 (10) | 145.1 |

| N5–H5A···I4 | 2.739 | 3.547 (11) | 150.0 |

| N5–H5B···I4 | 2.835 | 3.607 (12) | 144.7 |

| N6–H6A···I5 | 2.653 | 3.539 (13) | 168.3 |

| N6–H6B···I2 | 2.718 | 3.540 (13) | 152.3 |

| O1–H1···I3 | 2.65 (9) | 3.515 (10) | 144 (12) |

| O1–H2···I5 | 2.70 (7) | 3.630 (11) | 155 (11) |

| (HpipeH2)3(H3O)I7 | |||

| N0AA–H0AA···I7 | 2.689 | 3.508 (3) | 150.2 |

| N0AA–H0AB···I7 | 2.744 | 3.586 (3) | 149.1 |

| N5–H5A···I3 | 2.649 | 3.542 (3) | 167.2 |

| N5–H5B···I2 | 2.822 | 3.542 (3) | 136.9 |

| N2–H2C···I6 | 2.706 | 3.515 (3) | 148.7 |

| N2–H2D···I6 | 2.718 | 3.539 (3) | 150.5 |

| N3–H3C···I5 | 2.656 | 3.545 (3) | 165.9 |

| N3–H3D···I2 | 2.831 | 3.521 (3) | 133.6 |

| N4–H4C···I1 | 2.726 | 3.612 (3) | 165.0 |

| N4–H4D···I4 | 2.870 | 3.532 (3) | 130.8 |

| N6–H6C···I1 | 2.933 | 3.491 (3) | 121.1 |

| N6–H6D···I4 | 2.866 | 3.677 (4) | 149.2 |

| O1–H1D···I2 | 2.609 | 3.467 (4) | 170.8 |

| O1–H1E···I3 | 2.796 | 3.605 (4) | 156.7 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shestimerova, T.A.; Mironov, A.V.; Bykov, M.A.; Grigorieva, A.V.; Wei, Z.; Dikarev, E.V.; Shevelkov, A.V. Assembling Polyiodides and Iodobismuthates Using a Template Effect of a Cyclic Diammonium Cation and Formation of a Low-Gap Hybrid Iodobismuthate with High Thermal Stability. Molecules 2020, 25, 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25122765

Shestimerova TA, Mironov AV, Bykov MA, Grigorieva AV, Wei Z, Dikarev EV, Shevelkov AV. Assembling Polyiodides and Iodobismuthates Using a Template Effect of a Cyclic Diammonium Cation and Formation of a Low-Gap Hybrid Iodobismuthate with High Thermal Stability. Molecules. 2020; 25(12):2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25122765

Chicago/Turabian StyleShestimerova, Tatiana A., Andrei V. Mironov, Mikhail A. Bykov, Anastasia V. Grigorieva, Zheng Wei, Evgeny V. Dikarev, and Andrei V. Shevelkov. 2020. "Assembling Polyiodides and Iodobismuthates Using a Template Effect of a Cyclic Diammonium Cation and Formation of a Low-Gap Hybrid Iodobismuthate with High Thermal Stability" Molecules 25, no. 12: 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25122765

APA StyleShestimerova, T. A., Mironov, A. V., Bykov, M. A., Grigorieva, A. V., Wei, Z., Dikarev, E. V., & Shevelkov, A. V. (2020). Assembling Polyiodides and Iodobismuthates Using a Template Effect of a Cyclic Diammonium Cation and Formation of a Low-Gap Hybrid Iodobismuthate with High Thermal Stability. Molecules, 25(12), 2765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25122765