Sterepinic Acids A–C, New Carboxylic Acids Produced by a Marine Alga-Derived Fungus

Abstract

1. Introduction

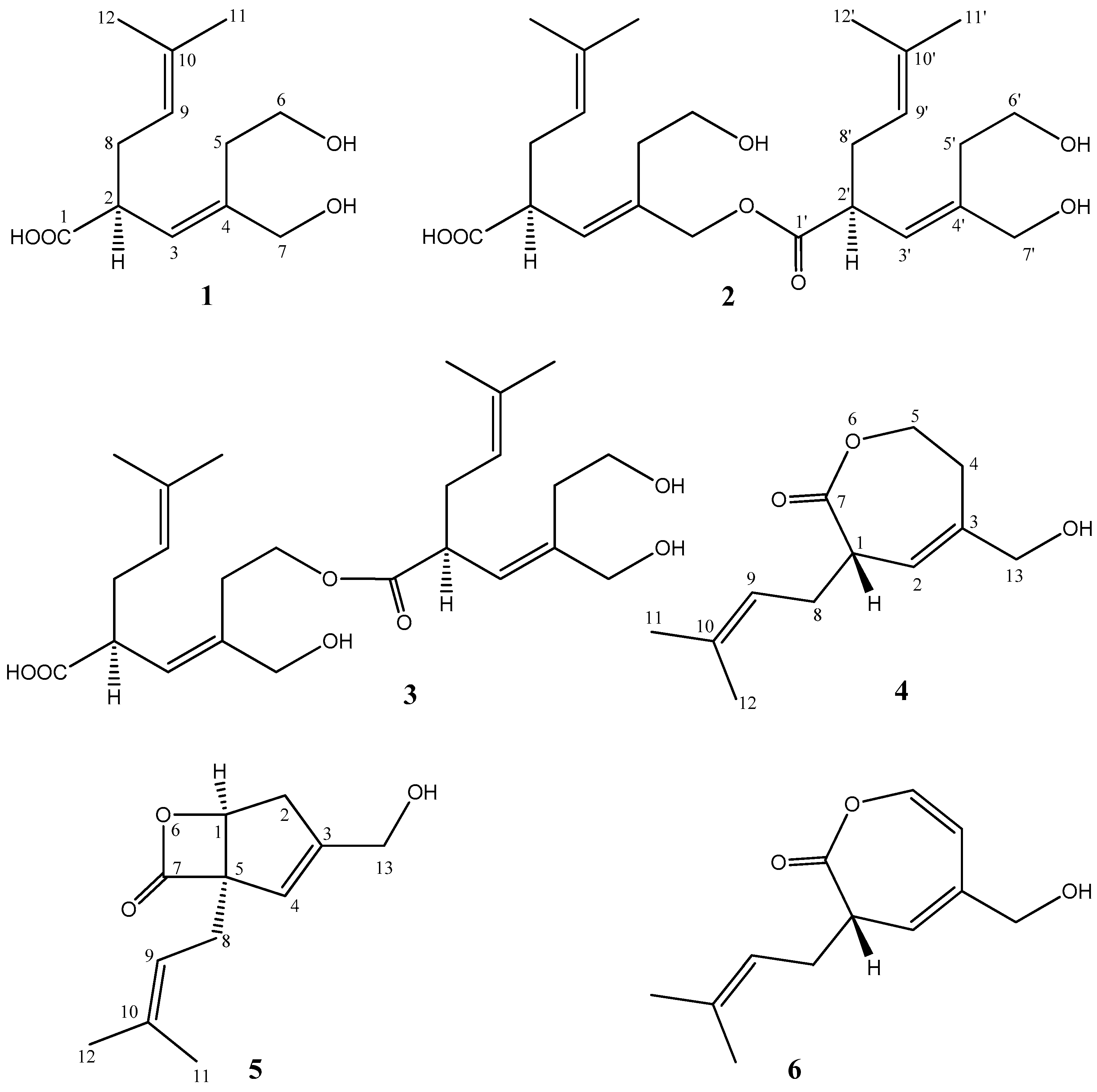

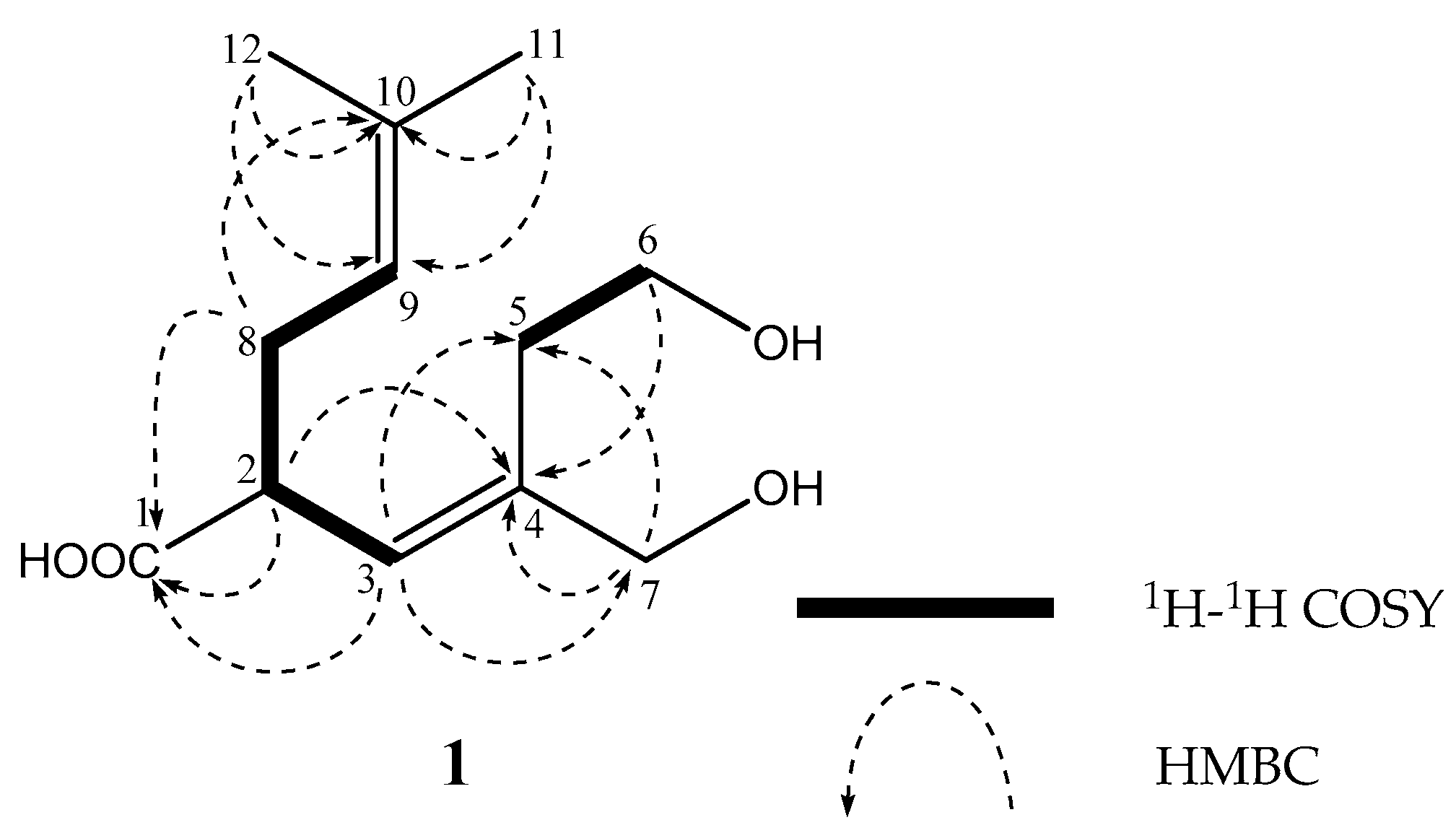

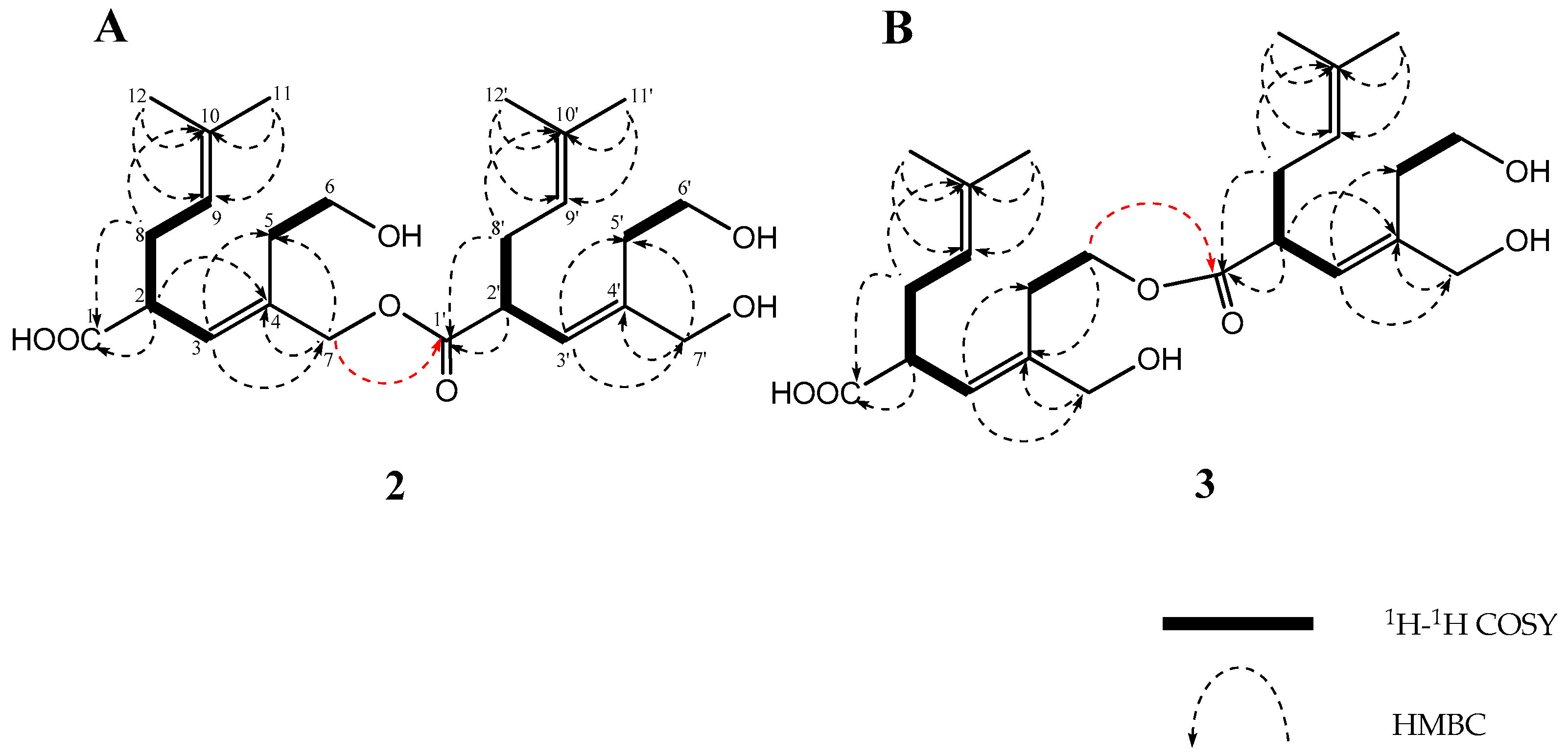

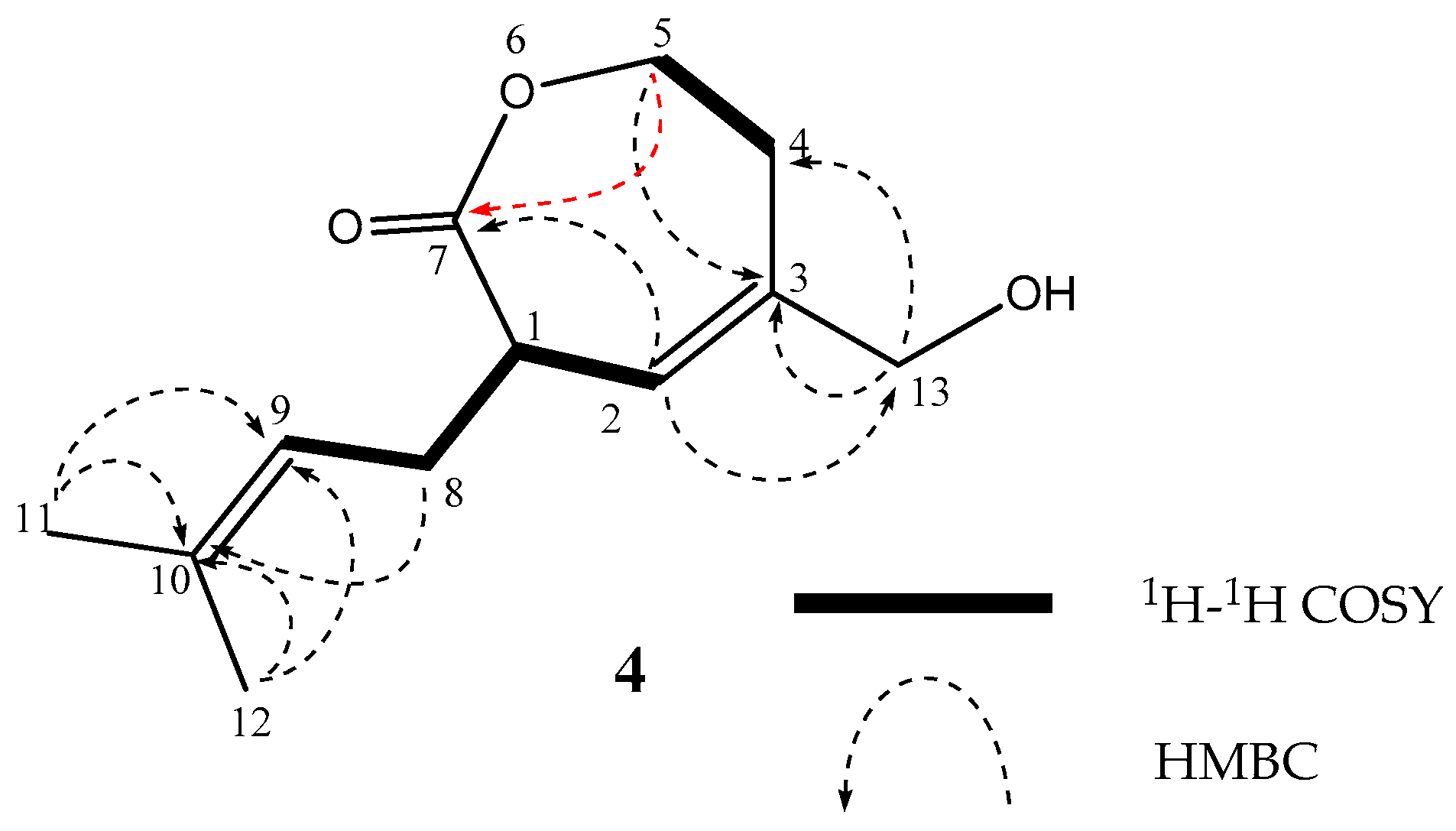

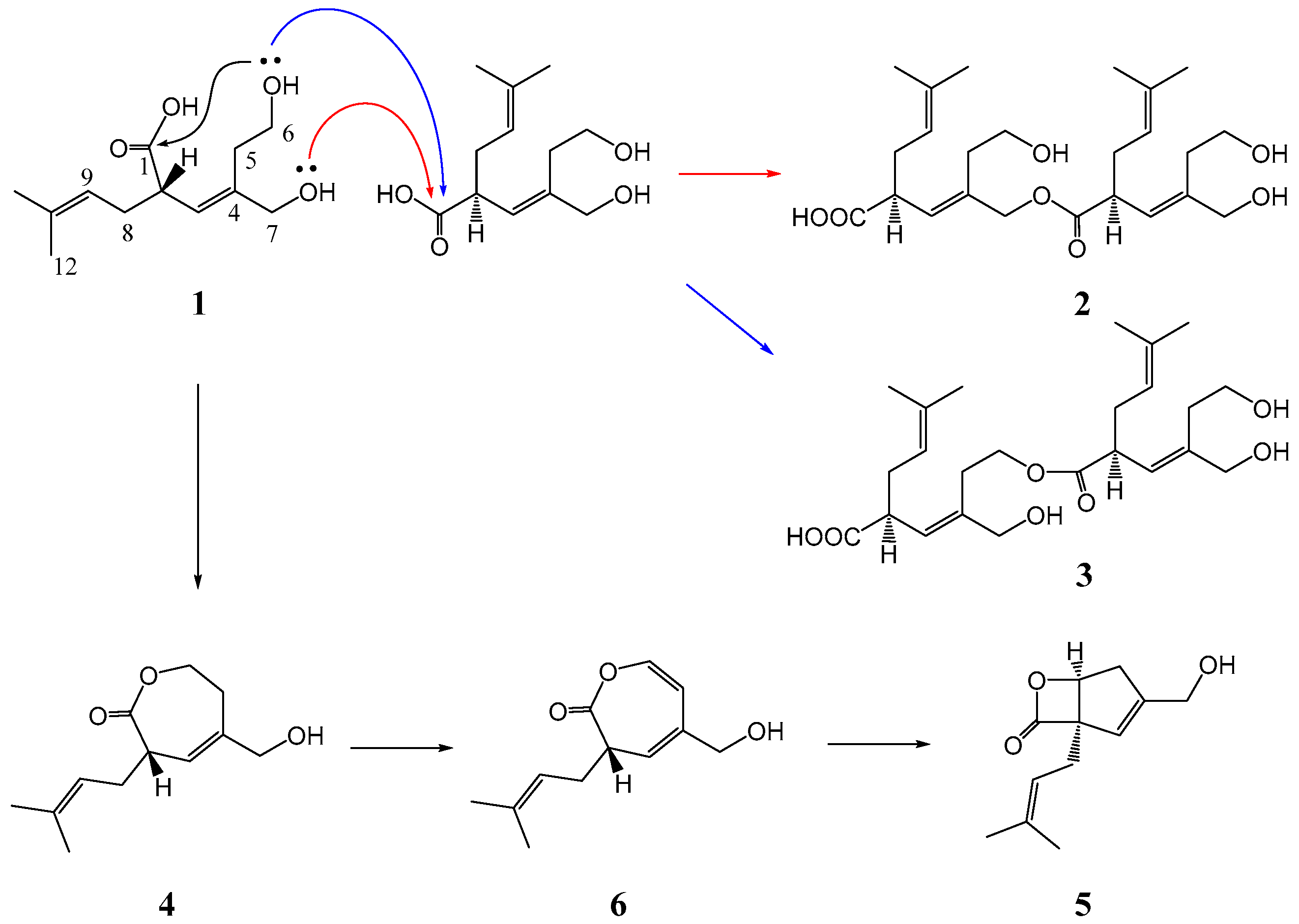

2. Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Fungal Material

3.3. Culturing and Isolation of Metabolites

3.4. Chemical Transformation

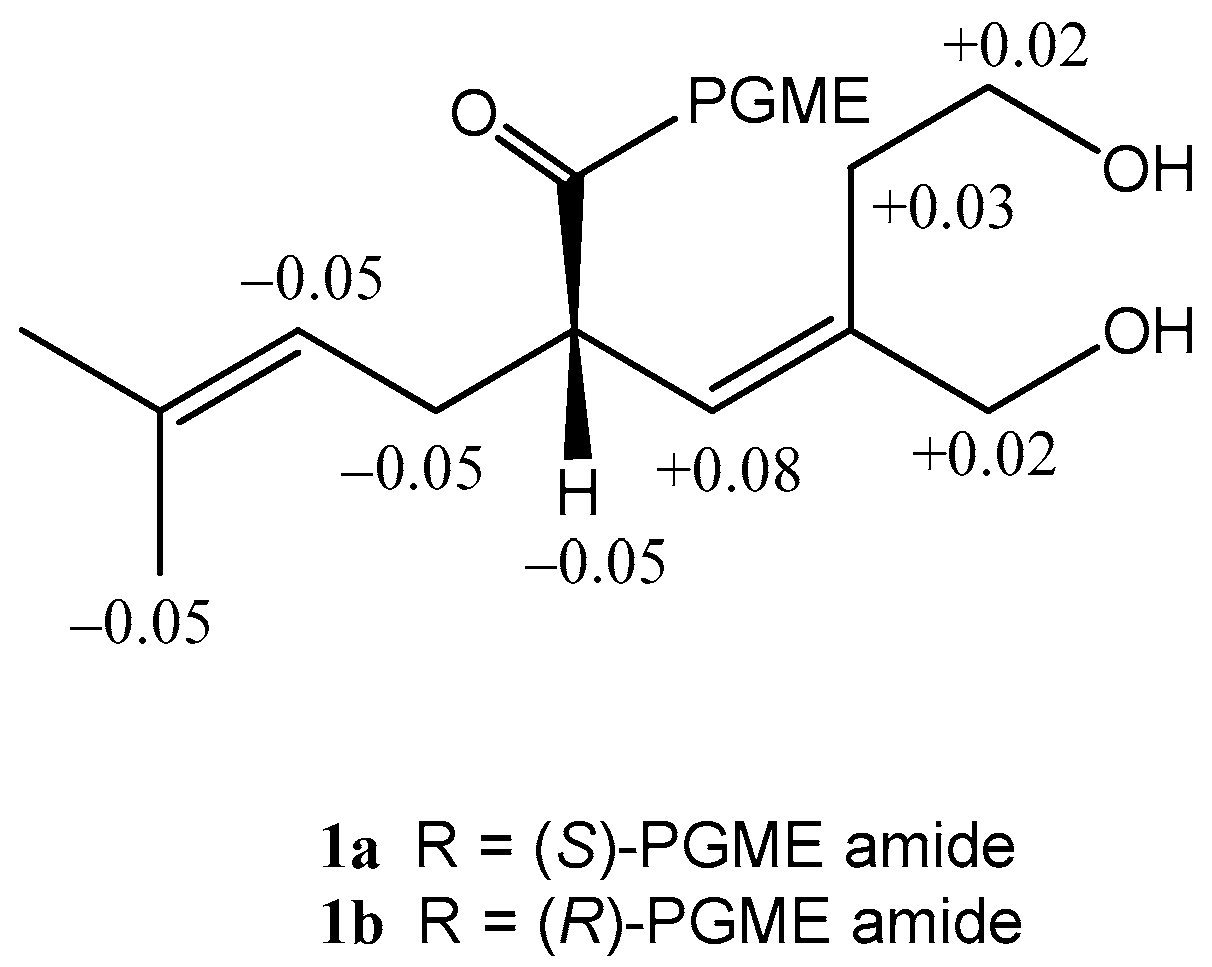

3.4.1. Formation of the (S)- and (R)-PGME Amides

3.4.2. Formation of Methyl Ester of 1

3.4.3. Methanolysis of 2–4

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muroga, Y.; Yamada, T.; Numata, A.; Tanaka, R. Chaetomugilins I–O, new potent cytotoxic metabolites from a marine-fish-derived Chaetomium species. Stereochemistry and biological activities. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 7580–7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Kitada, H.; Kajimoto, T.; Numata, A.; Tanaka, R. The relationship between the CD Cotton effect and the absolute configuration of FD-838 and its seven stereoisomers. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 4146–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Tanaka, R.; Numata, A. Halichoblelides B and C, potent cytotoxic macrolides from a Streptomyces species separated from a marine fish. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 2842–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M.; Yamada, T.; Amagata, T.; Minoura, K.; Tanaka, R.; Numata, A. Novel pyridinopyrone sesquiterpene type pileotin produced by a sea urchin-derived Aspergillus sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 4192–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Mizutani, Y.; Umebayashi, Y.; Inno, N.; Kawashima, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Tanaka, R. A novel ketoaldehyde decalin derivative, produced by a marine sponge-derived Trichoderma harzianum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Umebayashi, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Sugiura, Y.; Kikuchi, T.; Tanaka, R. Determination of the chemical structures of tandyukisins B–D, isolated from a marine sponge-derived fungus. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3231–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzue, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Tanaka, R.; Yamada, T. Tandyukisins E and F, novel cytotoxic decalin derivatives isolated from a marine sponge-derived fungus. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 5070–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Suzue, M.; Arai, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Tanaka, R. Trichodermanins C–E, new diterpenes with a fused 6-5-6-6 ring system produced by a marine sponge-derived fungus. Marine Drugs 2017, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.Z.; Wang, F.; Liao, T.G.; Tang, J.G.; Steglich, W.; Zhu, H.J.; Liu, J.K. Vibralactone: A lipase inhibitor with an unusual fused β-lactone produced by cultures of the basidiomycete. Boreostereum vibrans. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5749–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.L.; Fang, L.Z.; Dong, Z.J.; Zhu, H.J.; Liu, J.K. Derivatives of vibralactone from cultures of the basidiomycete Boreostereum vibrans. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 1286–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.J.; Yang, Z.L.; Leng, Y.; Liu, J.K. Vibralactones D–F from cultures of the basidiomycete Boreostereum vibrans. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.H.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.H.; Li, L.; Liu, J.K. Twelve new compounds from the basidiomycete Boreostereum vibrans. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2012, 2, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Q.; Wei, K.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.A.; Liu, J.K. Vibralactones G-J from cultures of the basidiomycete Boreostereum vibrans. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 14, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.Q.; Wei, K.; Li, Z.H.; Feng, T.; Ding, J.H.; Wang, Q.A.; Liu, J.K. Three new compounds from the cultures of basidiomycete Boreostereum vibrans. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 15, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.P.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Yin, R.H.; Yin, X.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.H.; Wei, K.; Liu, J.K. Six new vibralactone derivatives from cultures of the fungus Boreostereum vibrans. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2014, 4, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yabuuchi, T.; Kusumi, T. Phenylglycine Methyl Ester, a Useful Tool for Absolute Configuration Determination of various chiral carboxylic acids. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.J.; Yang, Y.L.; Du, L.; Liu, J.K.; Zeng, Y. Elucidating the biosynthetic pathway for vibralactone: A pancreatic lipase inhibitor with a fused bicyclic β-lactone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2298–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors. |

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δHa | δC | δHa | δC | δHa | δC | ||||||||

| 1 | 177.5 | (s) | 173.5 | (s) | 174.3 | (s) | |||||||

| 2 | 3.27 | m | 44.9 | (d) | 3.28 | m | 45.4 | (d) | 3.28 | m | 44.9 | (d) | |

| 3 | 5.50 | d (10.2) | 127.0 | (d) | 5.49 | d (10.8) | 129.3 | (d) | 5.55 | d (9.6) | 129.3 | (d) | |

| 4 | 138.7 | (s) | 133.9 | (s) | 137.9 | (s) | |||||||

| 5A | 2.25 | m | 31.9 | (t) | 2.18 | m | 32.3 | (t) | 2.30 | ddd (14.4, 5.4, 5.4) | 27.7 | (t) | |

| 5B | 2.49 | m | 2.54 | m | 2.54 | ddd (14.4, 5.4, 5.4) | |||||||

| 6A | 3.68 | br s | 61.0 | (t) | 3.65 | br s | 61.4 | (t) | 4.20 | m | 63.5 | (t) | |

| 6B | 66.8 | (t) | 3.72 | br s | |||||||||

| 7A | 4.03 | br s | 4.05 | d (13.2) | 67.9 | (t) | 4.07 | m | 66.5 | (t) | |||

| 7B | d (13.2) | ||||||||||||

| 8A | 2.20 | m | 30.9 | (t) | 2.20 | m | 30.8 b5 | (t) | 2.20 | m | 31.4 | (t) | |

| 8B | 2.44 | m | 2.46 | m | 2.44 | m | |||||||

| 9 | 5.04 | dd | 120.2 | (d) | 5.03 | m | 120.2 b6 | (d) | 5.02 b1 | dd (7.2, 7.2) | 120.2 b2 | (d) | |

| 10 | 134.1 | (s) | 134.2 b7 | (s) | 134.3 | (s) | |||||||

| 11 | 1.67 | s | 25.7 | (q) | 1.67 | s | 25.7 | (q) | 1.67 | s | 25.7 | (q) | |

| 12 | 1.60 | s | 17.8 | (q) | 1.60 | s | 17.8 | (q) | 1.59 b3 | s | 17.8 b4 | (q) | |

| 1′ | 173.5 | (s) | 174.3 | (s) | |||||||||

| 2′ | 3.28 | m | 45.4 | (d) | 3.28 | m | 44.9 | (d) | |||||

| 3′ | 5.52 | d (10.8) | 127.2 | (d) | 5.51 | d (9.6) | 127.2 | (d) | |||||

| 4′ | 139.6 | (s) | 138.7 | (s) | |||||||||

| 5′A | 2.29 | m | 32.3 | (t) | 2.25 | m | 32.2 | (t) | |||||

| 5′B | 2.54 | m | 2.51 | m | |||||||||

| 6′A | 3.72 | br s | 60.5 | (t) | 3.65 | br s | 61.1 | (t) | |||||

| 6′B | 3.71 | br s | |||||||||||

| 7′ | 4.05 | br s | 67.5 | (t) | 4.02 | m | 67.4 | (t) | |||||

| 8′A | 2.20 | m | 30.6 b5 | (t) | 2.20 | m | 31.4 | (t) | |||||

| 8′B | 2.46 | m | 2.44 | m | |||||||||

| 9′ | 5.03 | m | 120.3 b6 | (d) | 5.06 b1 | dd (7.2, 7.2) | 120.3 b2 | (d) | |||||

| 10′ | 134.3 b7 | (s) | 134.3 | (s) | |||||||||

| 11′ | 1.67 | s | 25.7 | (q) | 1.67 | s | 25.7 | (q) | |||||

| 12′ | 1.60 | s | 17.8 | (q) | 1.61 b3 | s | 17.9 b4 | (q) | |||||

| Position | 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δHa | δC | |||

| 1 | 3.68 | m | 40.2 | (d) |

| 2 | 5.36 | br s | 121.2 | (d) |

| 3 | 139.2 | (s) | ||

| 4A | 2.45 | br d (19.2) | 30.3 | (t) |

| 4B | 2.59 | m | ||

| 5α | 4.68 | ddd (12.6, 12.6, 1.8) | 64.4 | (t) |

| 5β | 4.33 | ddd (12.6, 4.8, 2.4) | ||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | 174.3 | (s) | ||

| 8A | 2.33 | ddd (14.4, 6.6, 6.6) | 30.1 | (t) |

| 8B | 2.52 | ddd (14.4, 6.6, 6.6) | ||

| 9 | 5.14 | dd (6.6, 6.6) | 120.9 | (d) |

| 10 | 134.6 | (s) | ||

| 11 | 1.72 | s | 25.8 | (q) |

| 12 | 1.67 | s | 18.0 | (q) |

| 13A | 3.99 | d (13.8) | 67.4 | (t) |

| 13B | 4.01 | d (13.8) | ||

| Compounds | Cell Line P388 | Cell Line HL-60 | Cell Line L1210 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) a | IC50 (μM) a | IC50 (μM) a | |

| 1 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 2 | >500 | 236.7 | >500 |

| 3 | >500 | 60.2 | 480.9 |

| 4 | >500 | 189.5 | >500 |

| 5-fluorouracil b | 6 | 4.9 | 4.5 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamada, T.; Matsuda, M.; Seki, M.; Hirose, M.; Kikuchi, T. Sterepinic Acids A–C, New Carboxylic Acids Produced by a Marine Alga-Derived Fungus. Molecules 2018, 23, 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23061336

Yamada T, Matsuda M, Seki M, Hirose M, Kikuchi T. Sterepinic Acids A–C, New Carboxylic Acids Produced by a Marine Alga-Derived Fungus. Molecules. 2018; 23(6):1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23061336

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamada, Takeshi, Miwa Matsuda, Mayuko Seki, Megumi Hirose, and Takashi Kikuchi. 2018. "Sterepinic Acids A–C, New Carboxylic Acids Produced by a Marine Alga-Derived Fungus" Molecules 23, no. 6: 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23061336

APA StyleYamada, T., Matsuda, M., Seki, M., Hirose, M., & Kikuchi, T. (2018). Sterepinic Acids A–C, New Carboxylic Acids Produced by a Marine Alga-Derived Fungus. Molecules, 23(6), 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23061336