Exploring the Prevalence of Protective Measure Adoption in Mosques during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia

Abstract

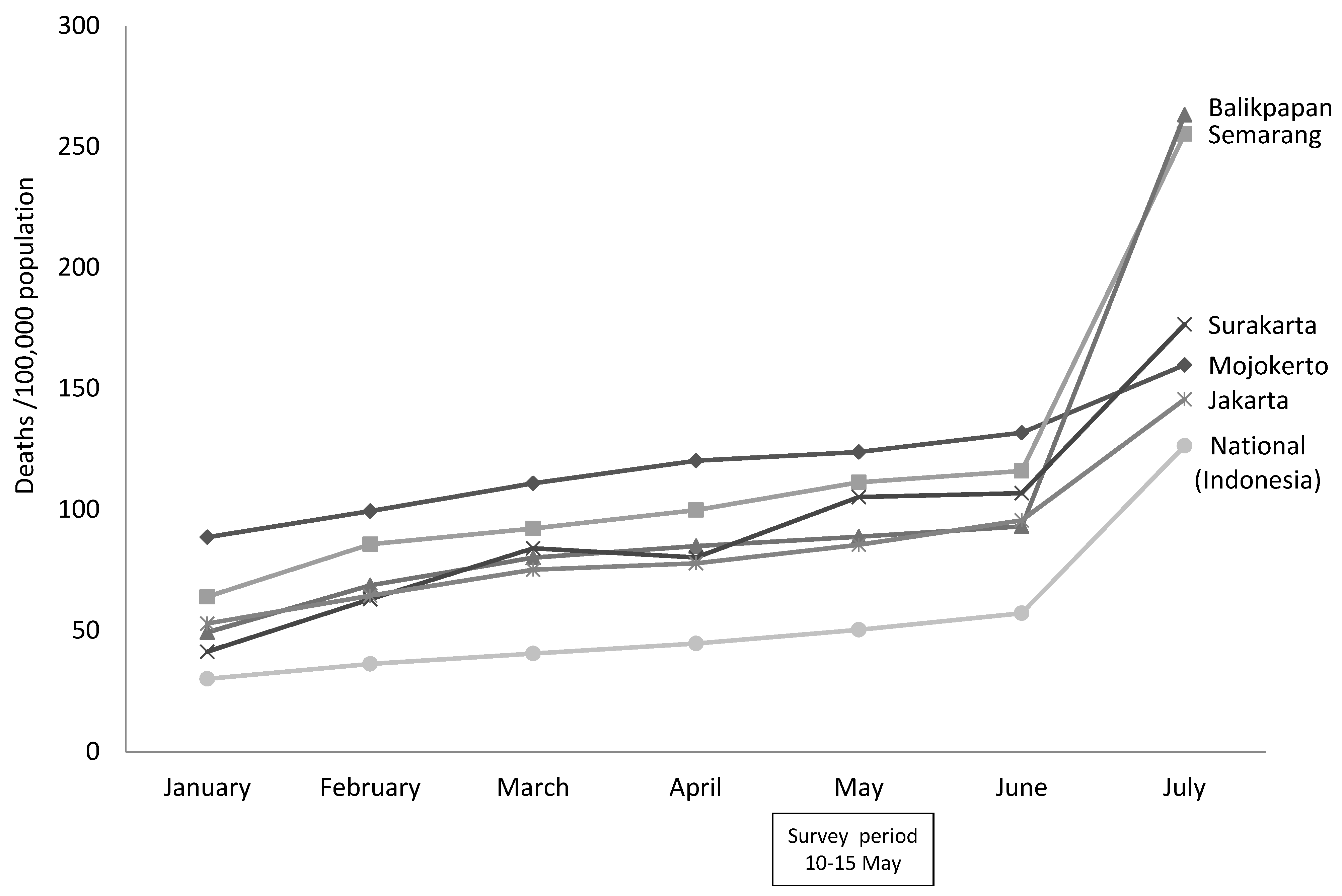

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

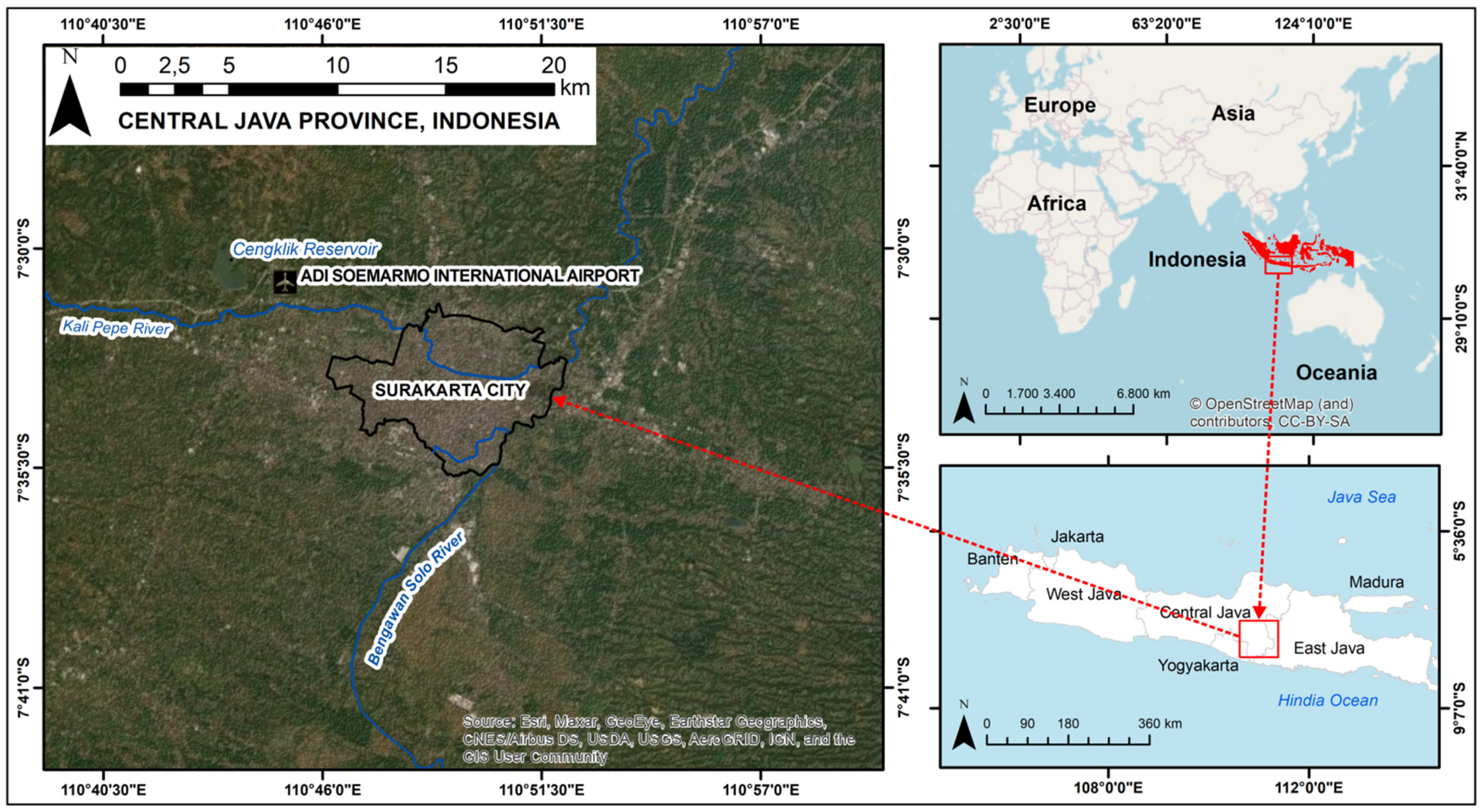

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Calculation and Sample Selection

2.3. Data Collection and Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

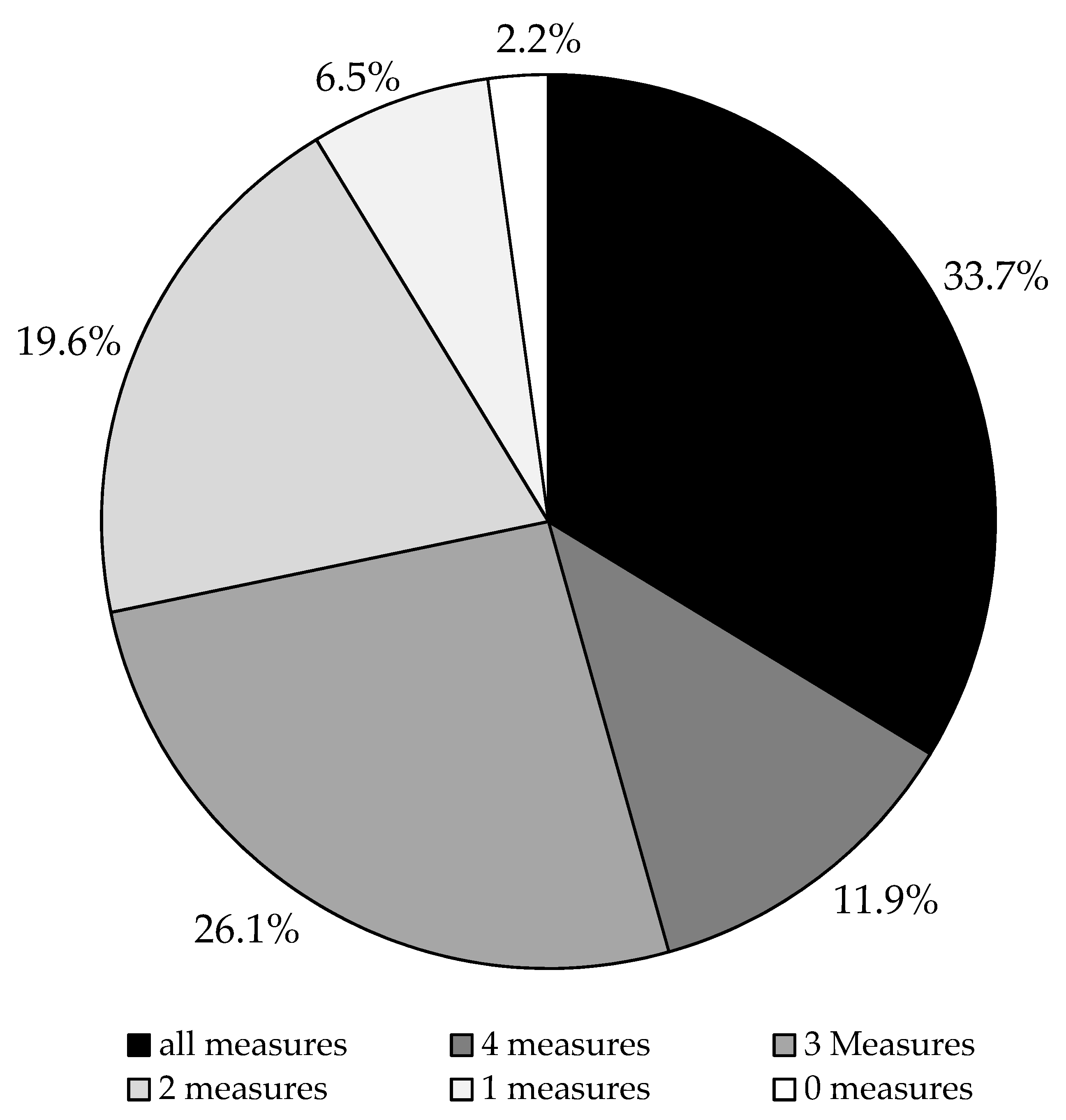

3. Results

Characteristics of Mosque and Mosque Caretaker

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shah, S.G.S. Doctors in Pakistan denounce opening of mosques for congregational prayers during Ramadan amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Correspondence. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 79, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boston, W. More Than 100 in Germany Found to Be Infected with Coronavirus after Church’s Services. Wall Street Journal. 24 May 2020. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/more-than-100-in-germany-found-to-be-infected-with-coronavirus-after-a-churchs-services-11590340102 (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Cline, S. Church Tied to Oregon’s Largest Coronavirus Outbreak. AP News. 17 June 2020. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/health-us-news-virus-outbreak-wa-state-wire-id-state-wire-b2d7a8af05e862dc3e1d1c3d0cf0afd0 (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Jeong, E.; Hagose, M.; Jung, H.; Ki, M. Understanding South Korea’s Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Real-Time Analysis. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, Y.D.; Byun, J.H.; Cho, G.; Park, A.; Jung, J.H.; Roh, Y.; Choi, S.; Muhammad, I.M.; Jung, I.H. Evaluation of COVID-19 epidemic outbreak caused by temporal contact-increase in South Korea. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 96, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadri, S.A. COVID-19 and religious congregations: Implications for spread of novel pathogens. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 96, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.M.; Sam, I.-C.; Chong, J.; Bador, M.K.; Ponnampalavanar, S.; Omar, S.F.S.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Munusamy, V.; Wong, C.K.; Jamaluddin, F.H.; et al. Sars-cov-2 lineage b.6 was the major contributor to early pandemic transmission in malaysia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, N.F.C.; Edinur, H.A.; Razab, M.K.A.A.; Safuan, S. A single mass gathering resulted in massive transmission of COVID-19 infections in Malaysia with further international spread. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.O.; Martí, G.; Braunstein, R.; Whitehead, A.L.; Yukich, G. Religion in the age of social distancing: How COVID-19 presents new directions for research. Sociol. Relig. 2020, 81, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Khan, A. COVID-19 pandemic: It is time to temporarily close places of worship and to suspend religious gatherings. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taaa065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Freedman, D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, O.; Roszkowski, K.; Montane, X.; Pawliszak, W.; Tylkowski, B.; Bajek, A. Religion and Faith Perception in a Pandemic of COVID-19. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirry, M.; Omar, A.R. Muslim prayer and public spheres: An interpretation of the Qur’ānic verse 29:45. Interpret 2014, 68, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Population Review. Indonesia Population. 2021. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/indonesia-population (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Sulkowski, L.; Ignatowski, G. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on organization of religious behaviour in different christian denominations in Poland. Religions 2020, 11, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Actions to Protect Ourselves. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/outbreaks-and-emergencies/covid-19/What-can-we-do-to-keep-safe/protective-measures/protect-ourselves (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- MUI. Fatwa No. 14 of 2020—Organization of Worship in Situations of COVID-19 Outbreak. 2020. Available online: https://mui.or.id/berita/27674/fatwa-penyelenggaraan-ibadah-dalam-situasi-terjadi-wabah-covid-19/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Qualls, N.; Levitt, A.; Kanade, N.; Wright-Jegede, N.; Dopson, S.; Biggerstaff, M.; Reed, C.; Uzicanin, A.; Frank, M.; Holloway, R.; et al. Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2017, 66, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwko, A.M. Islam and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Between Religious Practice and Health Protection. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 3291–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, M.; Nakamura, I.; Saito, R.; Nakaya, T.; Hanibuchi, T.; Takamiya, T.; Odagiri, Y.; Fukushima, N.; Kikuchi, H.; Kojima, T.; et al. Adoption of personal protective measures by ordinary citizens during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 94, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Indonesia Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation. 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/region/searo/country/id (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- National COVID-19 Task Force. Data COVID-19 Indonesia Update 30 Mei 2021. 2021. Available online: https://covid19.go.id/p/berita/analisis-data-covid-19-indonesia-update-30-mei-2021 (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Hari, K. Pak Jokowi, the Coronavirus Has Hit Home, The Jakarta Post. 2020. Available online: https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2020/03/21/pak-jokowi-the-coronavirus-has-hit-home.html (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Central Bureau of Statistics of Surakarta. Population by Religion in Surakarta. 2020. Available online: https://surakartakota.bps.go.id/indicator/12/319/1/jumlah-penduduk-menurut-kelompok-umur-dan-jenis-kelamin.html (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Raosoft. Sample Size Calculator. 2021. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Gravetter, F.J.; Wallnau, L.B. Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. In Statistic for the Behavioral Science, 10th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Istratii, R. Restricting Religious Practice in the Era of COVID-19: A De-Westernised Perspective on Religious Freedom with Reference to the Case of Greece, Polit Theol. 2020. Available online: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32584/1/RestrictingreligiouspracticeintheeraofCOVID-19.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Akhmad, B.A. Disparities in Health Communication of the Groups of Mosques in Responding to the Covid-19 Pandemic in Banjarmasin, South Kalimantan. J. Komun Ikat. Sarj. Komun. Indones. 2020, 5, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, C.; Bowman, L.; Eaton, J.W.; Imai, N.; Redd, R.; Pristera, P.; Vrinten, C.; Ward, H. Public Response to UK Government Recommendations on COVID-19: Population Survey, 17–18 March 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-10-population-survey-covid-19/ (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- FDA. Non-Contact Temperature Assessment Devices During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-covid-19-and-medical-devices/non-contact-temperature-assessment-devices-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Guidelines for the Use of Non-Pharmaceutical Measures to Delay and Mitigate the Impact of 2019- nCoV. 2020. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/covid-19-guidelines-non-pharmaceutical-interventions (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Liu, S.F.; Chang, J.F.; Wang, M.H. Mask design for life in the midst of covid-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Han, S.H.; Rhee, J.-Y. Cluster of Coronavirus Disease Associated with Fitness Dance Classes, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1917–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naunheim, M.R.; Bock, J.; Doucette, P.A.; Hoch, M.; Howell, I.; Johns, M.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Krishna, P.; Meyer, D.; Milstein, C.F.; et al. Safer Singing During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: What We Know and What We Don’t. J. Voice 2021, 35, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-M.; Yi, S.; Lee, S.; Na, B.; Kim, C.B.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, H.S.; Park, Y.; Huh, I.S.; et al. Coronavirus Disease Outbreak in Call Center, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1666–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Public Health Guidance for Community-Related Exposure. Centers for Desease Control and Prevention, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/public-health-recommendations.html#print (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Hashmi, T.; Aldahe, A.; Zidan, M. Muslim congregational prayer and COVID19 transmission. Int. J. Med. Rev. Case Rep. 2020, 4, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, J.; Berglof, E.; Buckee, C.; Farrar, J.; Grenfell, B.; Holmes, E.C.; Metcalf, C.J.E.; Sridhar, D.; Thompson, B. COVID-19 Futures: A Framework for Exploring Medium and Long-Term Impacts. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2020, 1, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 247 | ||

| n | % | |

| Mosque characteristics | ||

| The mosque’s affiliation to an Islamic organization | ||

| No affiliation | 126 | 51.1 |

| Majelis Tafsir Alquran | 16 | 6.5 |

| Nahdlatul Ulama | 40 | 16.3 |

| Muhammadiyah | 64 | 26.1 |

| The mosque’s age (years) | ||

| <10 | 38 | 15.2 |

| 10–50 | 175 | 70.7 |

| >50 | 35 | 14.1 |

| The mosque’s floor area (square meters) * | ||

| <250 | 142 | 57.6 |

| 250–500 | 54 | 21.7 |

| >500 | 51 | 20.7 |

| The number of worshippers in each congregational prayer | ||

| <20 | 83 | 33.7 |

| 20–50 | 110 | 44.6 |

| >50 | 54 | 21.7 |

| Mosque caretaker’s characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 247 | 100.0 |

| Female | 0 | 0.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 240 | 97.2 |

| Widowed | 7 | 2.8 |

| Age (Years) | ||

| <30 | 46 | 18.5 |

| 30–39 | 64 | 26.1 |

| 40–49 | 107 | 43.5 |

| 50–59 | 21 | 8.7 |

| >60 | 8 | 3.3 |

| Education attainment | ||

| Primary | 27 | 10.8 |

| Junior high school | 50 | 20.4 |

| Senior high school | 146 | 59.1 |

| University graduate or above | 24 | 9.7 |

| Length of time as mosque caretaker (years) | ||

| <5 | 13 | 5.3 |

| 5–10 | 153 | 61.8 |

| >10 | 81 | 32.9 |

| N | 1. Always | 2. Sometimes | 3. Rarely | 4. Never | |

| n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | ||

| Checking body temperature before entering the mosque | 247 | 48 (19.6) | 62 (25.0) | 32 (13.0) | 105 (42.4) |

| Prayer distancing | 247 | 153 (62.0) | 46 (18.5) | 27 (10.8) | 21 (8.7) |

| 1. All of the pray-ers | 2. Most of the pray-ers | 3. A few pray-ers | 4. None of the pray-ers | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Carrying own prayer mat | 247 | 30 (12.0) | 102 (41.3) | 73 (29.3) | 43 (17.4) |

| Wearing a mask when praying | 247 | 89 (35.9) | 86 (34.8) | 51 (20.7) | 21 (8.7) |

| No handshaking after pray | 247 | 78 (31.5) | 150 (60.9) | 13 (5.4) | 5 (2.2) |

| Variable | n | p-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| The mosque’s affiliation to an Islamic organization | |||||

| No affiliation | 126 | 0.778 | 0.897 | 0.420 | 1.913 |

| Majelis Tafsir Alquran | 16 | 0.102 | 0.302 | 0.072 | 1.268 |

| Nahdlatul Ulama | 40 | 0.016 | 0.510 | 0.073 | 1.240 |

| Muhammadiyah | 64 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| The mosque’s age (years) | |||||

| <10 | 38 | <0.001 | 9.304 | 2.826 | 30.633 |

| 10–50 | 175 | 0.263 | 1.775 | 0.650 | 4.844 |

| >50 | 35 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| The mosque’s floor area (square meters) | |||||

| <250 | 142 | 0.039 | 0.470 | 0.084 | 1.573 |

| 250–500 | 54 | 0.194 | 0.485 | 0.162 | 1.447 |

| >500 | 51 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| The number of worshipers in each congregational prayer (person) | |||||

| <20 | 83 | <0.001 | 1.590 | 0.702 | 3.615 |

| 20–50 | 110 | <0.001 | 1.271 | 0.576 | 2.841 |

| >50 | 54 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amin, C.; Priyono, P.; Umrotun, U.; Fatkhiyah, M.; Sufahani, S.F. Exploring the Prevalence of Protective Measure Adoption in Mosques during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413927

Amin C, Priyono P, Umrotun U, Fatkhiyah M, Sufahani SF. Exploring the Prevalence of Protective Measure Adoption in Mosques during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413927

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmin, Choirul, Priyono Priyono, Umrotun Umrotun, Maulida Fatkhiyah, and Suliadi Firdaus Sufahani. 2021. "Exploring the Prevalence of Protective Measure Adoption in Mosques during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413927