Developing a Behavior Change Framework for Pandemic Prevention and Control in Public Spaces in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Pandemic-Related Behavior Change

2.2. Existing Health Interventions during Pandemics

2.3. The Theory of Planned Behavior

2.4. Research Gap

3. Methodology

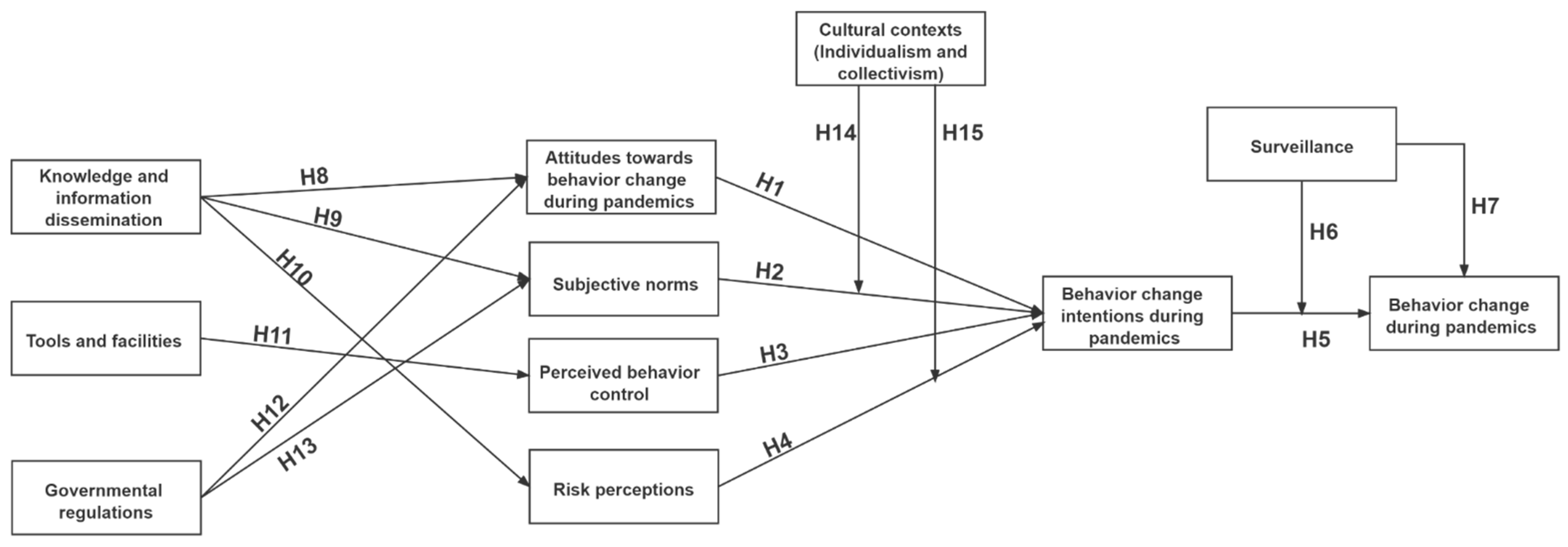

4. Hypotheses Development and Research Framework

4.1. Attitudes towards Behavior Change during Pandemics

4.2. Subjective Norms

4.3. Perceived Behavior Control

4.4. Risk Perceptions

4.5. Intention–Behavior Discrepancy and Surveillance

4.6. Information and Knowledge Dissemination

4.7. Tools and Facilities

4.8. Governmental Regulations

4.9. Cultural Context (Individualism/Collectivism)

5. Empirical Examination

5.1. Measurement Development

5.2. Questionnaire Design and Pilot Test

5.3. Data Collection and Sampling

5.4. Data Analysis

5.5. Results

5.5.1. Participants

5.5.2. Reliability, Validity, and Fit Index of the Measurement Model

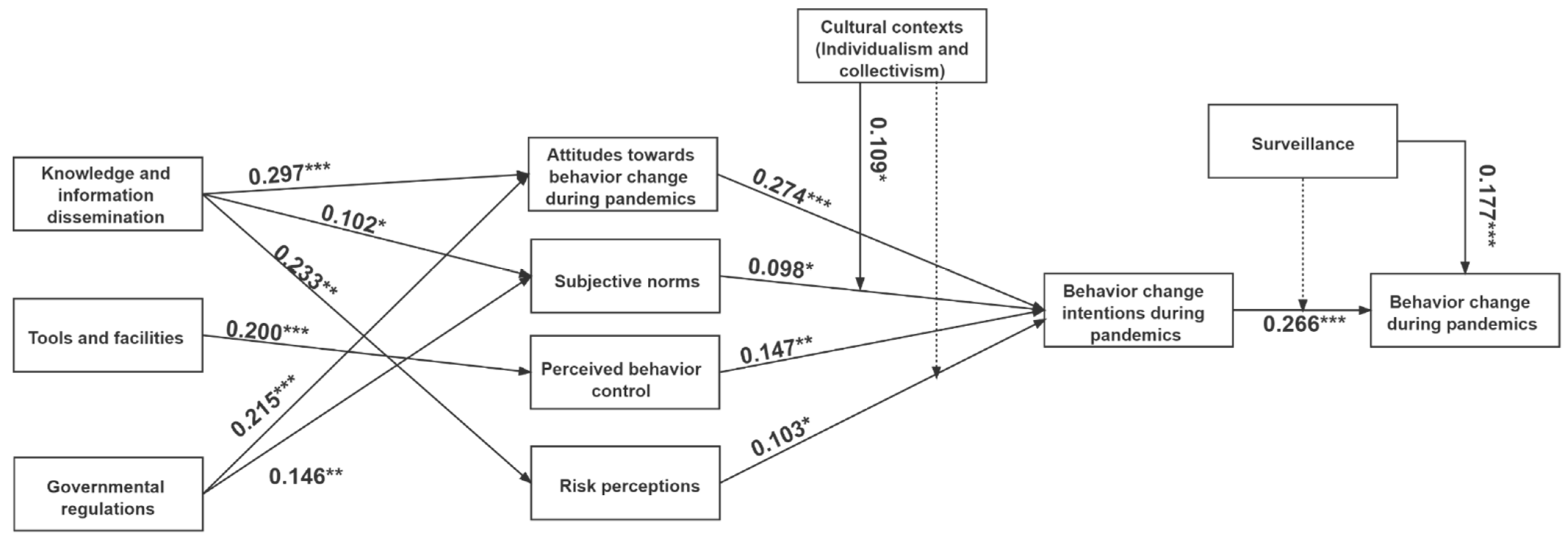

5.5.3. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussions and Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Informant | Age | Gender | Educational Level | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informant 1 | 46 | Male | PhD | Associate professor of design |

| Informant 2 | 43 | Male | PhD | Professor of design |

| Informant 3 | 31 | Male | Master | Senior lecture in design |

| Informant 4 | 31 | Female | Master | Senior lecture in design |

| Informant 5 | 37 | Female | Master | Senior lecture in design |

| Informant 6 | 29 | Female | PhD | PhD candidate in design |

| Informant 7 | 28 | Male | Master | Interactive designer |

| Informant 8 | 30 | Male | Master | Urban designer |

| Informant 9 | 29 | Male | Master | Design manager |

| Informant 10 | 29 | Female | Master | Industrial designer |

| Informant 11 | 28 | Male | Bachelor | Government servant in pandemic prevention and control sector |

| Informant 12 | 28 | Male | Bachelor | Government servant |

| Informant 13 | 28 | Female | Master | Health worker |

| Informant 14 | 29 | Female | Bachelor | Health worker |

| Informant 15 | 23 | Female | Bachelor | Health worker |

| Informant 16 | 30 | Male | Master | Health worker |

| Informant 17 | 29 | Male | Master | Health worker |

| Informant 18 | 53 | Female | Middle school | Community worker |

| Informant 19 | 22 | Female | Diploma | Hotel worker |

| Informant 20 | 29 | Female | Master | Administrative assistant at university |

| Informant 21 | 29 | Female | Bachelor | Kindergarten manager |

| Informant 22 | 34 | Male | PhD | Computer Engineer |

| Latent Variables | Measurement Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Attitudes (ATT) | ATT1: I think behavior change is significant during pandemics. ATT2: I think behavior change is an effective solution during pandemics. ATT3: I think behavior change can curb the spread of viruses during pandemics. ATT4: I think behavior change can improve public security and health during pandemics. | [37] |

| Subjective norms (SN) | SN1: I will perform the recommended behaviors during pandemics if my family members think I should do so. SN2: I will perform the recommended behaviors during pandemics if my close friends think I should do so. SN3: I will perform the recommended behaviors during pandemics if the people I value think I should do so. SN4: I will perform the recommended behaviors during pandemics if the general public around me performs them. | [37,59] |

| Perceived behavior control (PBC) | PBC1: I have the skills and abilities to perform the recommended behavior for pandemic prevention and control. PBC2: It is up to me to perform the recommended behavior for pandemic prevention and control. PBC3: It is easy and convenient for me to perform the recommended behavior for pandemic prevention and control. | [37,61] |

| Risk perception (RP) | RP1: I am vulnerable if exposed to pandemic circumstances. RP2: If I am infected by viruses during pandemics, I will not be unable to manage my daily activities. RP3: If I am infected by viruses during pandemics, it will be risky. RP4: I could easily develop severe symptoms if infected during pandemics. | [68] |

| Behavior change intentions (BCI) | BCI1: I have intentions to wear facemasks when visiting public places or taking public transport during pandemics. BCI2: I have intentions to keep a certain physical distance from others and avoid crowded public places during pandemics. BCI3: I have intentions to keep hands clean and correctly wash hands during pandemics. BCI4: I have intentions to reduce contact with objects in public places during pandemics. | [106] |

| Behavior change implementations (BCIP) | BCIP1: I always wear facemasks when visiting public places or taking public transport during pandemics. BCIP2: I always keep a certain physical distance from others and avoid crowded public places during pandemics. BCIP3: I always keep my hands clean and correctly wash my hands during pandemics. BCIP4: I always reduce contact with objects in public places. | [68,106] |

| Knowledge and information dissemination (KID) | KID1: I have sufficient knowledge about the virus transmission method during pandemics. KID2: I know how to adopt correct preventive measures for pandemic prevention and control. KID3: I can receive real-time information about pandemic situations. KID4: I can distinguish fake news and misinformation during pandemics. | [39] |

| Cultural context (individualism/collectivism) (CC) | CC1: I think being accepted as a member of a group is more important than having autonomy and independence. CC2: I think group success is more important than individual success. CC3: I think being loyal to a group is more important than individual gain. CC4: Individuals should stick with the group even through difficulties. | [77] |

| Tools and facilities (TF) | TF1: I have access to tools and facilities (e.g., wash basins, face coverings, hand sanitizers, wearable devices, mobile applications) during pandemics. TF2: The tools and facilities are well-designed. TF3: The tools and facilities are useful for behavior change during pandemics. TF4: The tools and facilities can assist me in performing the recommended behavior during pandemics. | [107] |

| Governmental regulations (GR) | GR1: The incentive regulations from governments encourage me to perform the recommended behavior during pandemics. GR2: The punitive regulations from governments encourage me to perform the recommended behavior during pandemics. GR3: The epidemic prevention regulations from governments encourage me to perform the recommended behavior during pandemics. | [108,109] |

| Surveillance (SV) | SV1: Wearable devices can monitor whether I perform the recommended behavior during pandemics. SV2: Mobile applications can monitor whether I perform the recommended behavior during pandemics. SV3: Smart facilities can monitor whether I perform the recommended behavior during pandemics. SV4: Workers in public spaces can monitor whether I perform the recommended behavior during pandemics. | [29,30,69] |

| Attribute | Value | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 288 | 52.5% |

| Female | 261 | 47.5% | |

| Age | Under 20 | 58 | 10.4% |

| 21–30 | 138 | 24.8% | |

| 31–40 | 173 | 31.1% | |

| 41–50 | 141 | 25.4% | |

| Above 50 | 39 | 7.0% | |

| Educational level | Under Junior high school | 93 | 16.9% |

| High school | 94 | 17.1% | |

| Diploma | 124 | 22.6% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 173 | 31.5% | |

| Master’s degree and above | 65 | 11.8% | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | <2500 | 34 | 6.2% |

| 2500–5000 | 222 | 40.4% | |

| 5000–7500 | 137 | 25.0% | |

| 7500–10,000 | 107 | 19.5% | |

| >10,000 | 49 | 8.9% | |

| Subjective health condition | Very poor | 34 | 6.2% |

| Poor | 48 | 8.7% | |

| Moderate | 108 | 19.7% | |

| Good | 207 | 37.7% | |

| Very good | 152 | 27.7% | |

| Vaccination status | Not vaccinated | 19 | 3.5% |

| Vaccinated but not fully | 131 | 23.9% | |

| Fully vaccinated | 399 | 72.7% |

References

- Pike, J.; Bogich, T.; Elwood, S.; Finnoff, D.C.; Daszak, P. Economic optimization of a global strategy to address the pandemic threat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 18519–18523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, A.; Tiwari, S.; Deb, M.K.; Marty, J.L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): A global pandemic and treatment strategies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Leung, G.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Matsoso, M.P.; Ihekweazu, C.; Abbasi, K. COVID-19: How a Virus Is Turning the World Upside Down. Bmj 2020, 369, m1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grundy-Warr, C.; Lin, S. COVID-19 geopolitics: Silence and erasure in Cambodia and Myanmar in times of pandemic. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez EP, A.; Negi, D.P.; Rani, A.; AP, S.K. The impact of COVID-19 on migrant women workers in India. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2021, 62, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Light, D. COVID-19 in Romania: Transnational labour, geopolitics, and the Roma’ outsiders’. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiciar, C.; Creţan, R. Pandemic populism: COVID-19 and the rise of the nationalist AUR party in Romania. Geogr. Pannonica 2021, 25, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.; Moseley, W.G. This food crisis is different: COVID-19 and the fragility of the neoliberal food security order. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 1393–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simula, G.; Bum, T.; Farinella, D.; Maru, N.; Mohamed, T.S.; Taye, M.; Tsering, P. COVID-19 and pastoralism: Reflections from three continents. J. Peasant Stud. 2021, 48, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piret, J.; Boivin, G. Pandemics throughout history. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamran, A.; Naeim, M. Behavioural change theories: A necessity for managing COVID-19. Public Health 2021, 197, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betsch, C. How behavioural science data helps mitigate the COVID-19 crisis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Freedman, D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Kamarudin, K.M.; Liu, Y.; Zou, J. Developing Pandemic Prevention and Control by ANP-QFD Approach: A Case Study on Urban Furniture Design in China Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shen, F. Exploring the impacts of media use and media trust on health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J. Health Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perra, N. Non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Phys. Rep. 2021, 913, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardoulakis, S.; Sheel, M.; Lal, A.; Gray, D. COVID-19 environmental transmission and preventive public health measures. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arden, M.A.; Chilcot, J. Health psychology and the coronavirus (COVID-19) global pandemic: A call for research. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soper, G.A. The lessons of the pandemic. Science 1919, 49, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Wu, J.; Cao, L. COVID-19 pandemic in China: Context, experience and lessons. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olufadewa, I.I.; Adesina, M.A.; Ekpo, M.D.; Akinloye, S.J.; Iyanda, T.O.; Nwachukwu, P.; Kodzo, L.D. Lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic response in China, Italy, and the US: A guide for Africa and low-and-middle-income countries. Glob. Health J. 2021, 5, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Weman-Josefsson, K. Why people failed to adhere to COVID-19 preventive behaviors? Perspectives from an integrated behavior change model. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 42, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller, A.C.; Merchant, G.; Conroy, D.E.; West, R.; Hekler, E.; Kugler, K.C.; Michie, S. Applying and advancing behavior change theories and techniques in the context of a digital health revolution: Proposals for more effectively realizing untapped potential. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 40, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brownson, R.C.; Seiler, R.; Eyler, A.A. Peer Reviewed: Measuring the Impact of Public Health Policys. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A77. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jul/09_0249.htm (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Rowe, F.; Ngwenyama, O.; Richet, J.-L. Contact-tracing apps and alienation in the age of COVID-19. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Heemsbergen, L.; Fordyce, R. Comparative analysis of China’s Health Code, Australia’s COVIDSafe and New Zealand’s COVID Tracer Surveillance Apps: A new corona of public health governmentality? Media Int. Aust. 2021, 178, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, P.B.; Hense, S.; Kopparty, S.; Kalapala, G.R.; Haloi, B. How Indians responded to the Arogya Setu app? Indian J. Public Health 2020, 64, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.J.; Lal, V.; Baby, A.K.; James, A.; Raj, A.K. Can technological advancements help to alleviate COVID-19 pandemic? a review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 117, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathyamoorthy, A.J.; Patel, U.; Savle, Y.A.; Paul, M.; Manocha, D. COVID-robot: Monitoring social distancing constraints in crowded scenarios. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.06585. [Google Scholar]

- Toppenberg-Pejcic, D.; Noyes, J.; Allen, T.; Alexander, N.; Vanderford, M.; Gamhewage, G. Emergency risk communication: Lessons learned from a rapid review of recent gray literature on Ebola, Zika, and Yellow Fever. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-H.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, C. The effects of social media use on preventive behaviors during infectious disease outbreaks: The mediating role of self-relevant emotions and public risk perception. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazard, A.J.; Scheinfeld, E.; Bernhardt, J.M.; Wilcox, G.B.; Suran, M. Detecting themes of public concern: A text mining analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Ebola live Twitter chat. Am. J. Infect. Control 2015, 43, 1109–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzenkova, G.; Golovátina-Mora, P.; Ramirez, P.A.Z.; Sarmiento, J.M.H. Gamification Design for Behavior Change of Indigenous Communities in Choco, Colombia, During COVID-19 Pandemic. In Transforming Society and Organizations through Gamification: From the Sustainable Development Goals to Inclusive Workplaces; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021; pp. 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 70, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J.L.; Householder, B.J.; Greene, K.L. The theory of reasoned action. In The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 14, pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; Volume 26, pp. 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, K. From intention to behavior: Comprehending residents’ waste sorting intention and behavior formation process. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmmadi, P.; Rahimian, M.; Movahed, R.G. Theory of planned behavior to predict consumer behavior in using products irrigated with purified wastewater in Iran consumer. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.J.; Lai, H.R.; Lin, P.-C.; Kuo, S.Y.; Chen, S.R.; Lee, P.-H. Predicting exercise behaviors and intentions of Taiwanese urban high school students using the theory of planned behavior. J. Pediatric Nurs. 2022, 69, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, Y. The Coronavirus Pandemic: How Can Design Help? Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 31, pp. 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumari, M.C.; Sagar, B. Global pandemic and rapid new product development of medical products. Digit. Gov. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Sierra, I.; Catapan, M.F. Designing for the pandemic: Individual and collective safety devices. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2021, 14, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, A.; Michie, S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coifman, K.G.; Disabato, D.J.; Aurora, P.; Seah, T.S.; Mitchell, B.; Simonovic, N.; Foust, J.L.; Sidney, P.G.; Thompson, C.A.; Taber, J.M. What drives preventive health behavior during a global pandemic? Emotion and worry. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Cowling, B.J.; Lam, W.W.T.; Fielding, R. Factors affecting intention to receive and self-reported receipt of 2009 pandemic (H1N1) vaccine in Hong Kong: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wollast, R.; Schmitz, M.; Bigot, A.; Luminet, O. The Theory of Planned Behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison of health behaviors between Belgian and French residents. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goh, E.; Ritchie, B.; Wang, J. Non-compliance in national parks: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour model with pro-environmental values. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, L.; Goodwin, R. Using a theoretical framework to determine adults’ intention to vaccinate against pandemic swine flu 900 in priority groups in the UK. Public Health 2012, 126, S53–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, T.; Wei, S.; Arli, D. Social distancing behavior during COVID-19: A TPB perspective. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmeyer, S.; Wirtz, B.W.; Langer, P.F. Determinants of mHealth success: An empirical investigation of the user perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Wetherell, M.; Cochrane, S.; Hogg, M.A.; Turner, J.C. Knowing what to think by knowing who you are: Self-categorization and the nature of norm formation, conformity and group polarization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 29, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, R.M.; Fariss, C.J.; Jones, J.J.; Kramer, A.D.; Marlow, C.; Settle, J.E.; Fowler, J.H. A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature 2012, 489, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Christakis, N.A.; Fowler, J.H. Social contagion theory: Examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat. Med. 2013, 32, 556–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Gan, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. What Influences the Perceived Trust of a Voice-Enabled Smart Home System: An Empirical Study. Sensors 2021, 21, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M.; Cappella, J.N. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. J. Commun. 2006, 56 (Suppl. 1), S1–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luximon, Y.; Song, Y. The role of consumers’ perceived security, perceived control, interface design features, and conscientiousness in continuous use of mobile payment services. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, V. A/H1N1 vaccine intentions in college students: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lau, J.T.F.; Lau, M.M. Levels and factors of social and physical distancing based on the Theory of Planned Behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic among Chinese adults. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. The health belief model. Health Behav. Health Educ. Theory Res. Pract. 2008, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T.R. Impact of directly and indirectly experienced events: The origin of crime-related judgments and behaviors. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, G.M.; Lam, T.H.; Ho, L.M.; Ho, S.; Chan, B.; Wong, I.; Hedley, A.J. The impact of community psychological responses on outbreak control for severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, L.; Xie, J.; Li, K.; Ji, S. Exploring how media influence preventive behavior and excessive preventive intention during the 935 COVID-19 pandemic in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, N.; Gray, D. Mass surveillance in the age of COVID-19. J. Law Biosci. 2020, 7, lsaa023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.Y.; Bhatti, R. COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Pandemic: Information Sources Channels for the Public Health Awareness. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 32, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Kuang, Y.; Ben-Arieh, D. Information dissemination and human behaviors in epidemics. In Proceedings of the 2015 Industrial and Systems Engineering Research Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 30 May–2 June 2015; Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE): Nashville, TN, USA, 2015; p. 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; McCloud, R.F.; Bigman, C.A.; Viswanath, K. Tuning in and catching on? Examining the relationship between pandemic communication and awareness and knowledge of MERS in the USA. J. Public Health 2017, 39, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, K.; Fisher, C.; Rising, C.; Burke-Garcia, A.; Afanaseva, D.; Cai, X. Partnering with mommy bloggers to disseminate breast cancer risk information: Social media intervention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B.; W. SEEGER, M.A.T.T.H.E.W. Crisis and emergency risk, communication as an integrative model. J. Health Commun. 2005, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Motta Zanin, G.; Gentile, E.; Parisi, A.; Spasiano, D. A preliminary evaluation of the public risk perception related to the COVID-19 health emergency in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; Ren, H. What keeps Chinese from recycling: Accessibility of recycling facilities and the behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, P.-P. What Things Do: Philosophical Reflections on Technology, Agency, and Design, Trans; Pennsylvania State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lockton, D.; Harrison, D.; Stanton, N.A. The Design with Intent Method: A design tool for influencing user behaviour. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ibuka, Y.; Chapman, G.B.; Meyers, L.A.; Li, M.; Galvani, A.P. The dynamics of risk perceptions and precautionary behavior in response to 2009 (H1N1) pandemic influenza. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Forman, E.A.; Kraker, M.J. The social origins of logic: The contributions of Piaget and Vygotsky. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1985, 1985, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, E.; Greenhalgh, T.; Fahy, N. How are health-related behaviours influenced by a diagnosis of pre-diabetes? A meta-narrative review. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupton, D. Risk and emotion: Towards an alternative theoretical perspective. Health Risk Soc. 2013, 15, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organisations across nations. Aust. J. Manag. 2002, 27, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarhini, A.; Hone, K.; Liu, X.; Tarhini, T. Examining the moderating effect of individual-level cultural values on users’ acceptance of E-learning in developing countries: A structural equation modeling of an extended technology acceptance model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2017, 25, 306–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinev, T.; Goo, J.; Hu, Q.; Nam, K. User behaviour towards protective information technologies: The role of national cultural differences. Inf. Syst. J. 2009, 19, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, A.I.; Masoner, M.M. Sample Size Requirements in Structural Equation Models under Standard Conditions. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2013, 14, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.; Moosbrugger, H. Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika 2000, 65, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Tay, L. Modeling congruence in organizational research with latent moderated structural equations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.P.; Magnan, R.E.; Kramer, E.B.; Bryan, A.D. Theory of Planned Behavior Analysis of Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Focusing on the Intention–Behavior Gap. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M.S.; Smith, S.R.; Keech, J.J.; Moyers, S.A.; Hamilton, K. Predicting social distancing intention and behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrated social cognition model. Ann. Behav. Med. 2020, 54, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasneh, R.; Al-Azzam, S.; Muflih, S.; Soudah, O.; Hawamdeh, S.; Khader, Y. Media’s effect on shaping knowledge, awareness risk perceptions and communication practices of pandemic COVID-19 among pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1897–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weerd, W.; Timmermans, D.R.; Beaujean, D.J.; Oudhoff, J.; Van Steenbergen, J.E. Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception and intention of the general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stosic, M.D.; Helwig, S.; Ruben, M.A. Greater belief in science predicts mask-wearing behavior during COVID-19. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 176, 110769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, D.A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Pandemic Fatigue: Reinvigorating the Public to Prevent COVID-19: Policy Considerations for Member States in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/33582.htm (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Reicher, S.; Drury, J. Pandemic fatigue? How adherence to COVID-19 regulations has been misrepresented and why it matters. BMJ 2021, 372, n137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W. Does compact land use trigger a rise in crime and a fall in ridership? A role for crime in the land use–travel connection. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 3007–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, X.J.; Lu, D.; Chai, Y. Nonlinear effect of accessibility on car ownership in Beijing: Pedestrian-scale neighborhood planning. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 86, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L. COVID-19 information on social media and preventive behaviors: Managing the pandemic through personal 945 responsibility. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Long, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Ding, X.; Cai, S. Extending theory of planned behavior in household waste sorting in China: The moderating effect of knowledge, personal involvement, and moral responsibility. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7230–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, X.; Yin, J. Antecedents of urban residents’ separate collection intentions for household solid waste and their willingness to pay: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variable | Cronbach’s Alpha | Observable Variable | Standardized Factor Loading | AVE | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KID | 0.895 | KID1 | 0.818 | 0.681 | 0.895 |

| KID2 | 0.834 | ||||

| KID3 | 0.817 | ||||

| KID4 | 0.832 | ||||

| TF | 0.861 | TF1 | 0.78 | 0.607 | 0.861 |

| TF2 | 0.782 | ||||

| TF3 | 0.792 | ||||

| TF4 | 0.763 | ||||

| GR | 0.842 | GR1 | 0.805 | 0.643 | 0.843 |

| GR2 | 0.854 | ||||

| GR3 | 0.743 | ||||

| ATT | 0.848 | ATT1 | 0.777 | 0.584 | 0.849 |

| ATT2 | 0.796 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.736 | ||||

| ATT4 | 0.746 | ||||

| SN | 0.876 | SN1 | 0.819 | 0.639 | 0.876 |

| SN2 | 0.825 | ||||

| SN3 | 0.768 | ||||

| SN4 | 0.783 | ||||

| PBC | 0.845 | PBC1 | 0.828 | 0.647 | 0.846 |

| PBC2 | 0.834 | ||||

| PBC3 | 0.749 | ||||

| RP | 0.877 | RP1 | 0.808 | 0.642 | 0.877 |

| RP2 | 0.843 | ||||

| RP3 | 0.784 | ||||

| RP4 | 0.767 | ||||

| BCI | 0.898 | BCI1 | 0.829 | 0.689 | 0.899 |

| BCI2 | 0.855 | ||||

| BCI3 | 0.837 | ||||

| BCI4 | 0.798 | ||||

| BCIP | 0.872 | BCIP1 | 0.818 | 0.631 | 0.872 |

| BCIP2 | 0.787 | ||||

| BCIP3 | 0.776 | ||||

| BCIP4 | 0.795 | ||||

| CC | 0.859 | CC1 | 0.728 | 0.607 | 0.860 |

| CC2 | 0.859 | ||||

| CC3 | 0.777 | ||||

| CC4 | 0.746 | ||||

| SV | 0.881 | SV1 | 0.798 | 0.650 | 0.881 |

| SV2 | 0.842 | ||||

| SV3 | 0.786 | ||||

| SV4 | 0.798 |

| Construct | AVE | KID | TF | GR | ATT | SN | PBC | RP | BCI | CC | SV | BCIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KID | 0.681 | (0.825) | ||||||||||

| TF | 0.607 | 0.279 *** | (0.779) | |||||||||

| GR | 0.643 | 0.206 *** | 0.27 *** | (0.802) | ||||||||

| ATT | 0.584 | 0.33 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.264 *** | (0.764) | |||||||

| SN | 0.639 | 0.134 ** | 0.205 *** | 0.229 *** | 0.246 *** | (0.799) | ||||||

| PBC | 0.647 | 0.208 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.098 * | 0.218 *** | 0.110 * | (0.804) | |||||

| RP | 0.642 | 0.217 ** | 0.230 *** | 0.174 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.222 *** | 0.117 * | (0.801) | ||||

| BCI | 0.689 | 0.194 *** | 0.173 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.195 *** | (0.830) | |||

| CC | 0.607 | 0.109 * | 0.07 | 0.114 * | 0.099 * | 0.104 * | −0.054 | 0.127 ** | 0.13 ** | (0.779) | ||

| SV | 0.650 | 0.016 | −0.039 | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.094 | 0.019 | 0.032 | −0.034 | 0.045 | (0.806) | |

| BCIP | 0.631 | 0.147 ** | 0.244 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.167 *** | 0.146 ** | 0.241 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.004 | 0.170 *** | (0.794) |

| Research Model | Chi-Square | df | Chi-Square/df | TFI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark value | / | / | 1–5 | >0.9 | >0.9 | <0.08 | <0.08 |

| Measurement model | 901.798 | 764 | 1.180 | 0.987 | 0.988 | 0.018 | 0.028 |

| Structural model | 1047.779 | 797 | 1.315 | 0.979 | 0.977 | 0.024 | 0.062 |

| Hypothesis | Path Direction | Standardized Coefficient | Standard Error | CR (t Value) | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ATT → BCI | 0.274 | 0.048 | 5.707 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | SN → BCI | 0.098 | 0.047 | 2.067 | 0.039 | Accepted |

| H3 | PBC → BCI | 0.147 | 0.047 | 3.114 | 0.002 | Accepted |

| H4 | RP → BCI | 0.103 | 0.048 | 2.168 | 0.030 | Accepted |

| H5 | BCI → BCIP | 0.266 | 0.044 | 6.059 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H7 | SV → BCIP | 0.177 | 0.046 | 3.848 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H8 | KID → ATT | 0.297 | 0.045 | 6.542 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H9 | KID → SN | 0.102 | 0.048 | 2.123 | 0.034 | Accepted |

| H10 | KID → RP | 0.233 | 0.046 | 5.086 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H11 | TF → PBC | 0.200 | 0.048 | 4.160 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H12 | GR → ATT | 0.215 | 0.047 | 4.531 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H13 | GR → SN | 0.221 | 0.049 | 4.553 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Hypothesis | Path Direction | Standardized Coefficient | Standard Error | CR (t Value) | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6 | BCI × SV → BCIP | −0.155 | 0.087 | −1.785 | 0.074 | Rejected |

| H14 | CC × SN → BCI | 0.109 | 0.049 | 2.247 | 0.025 | Accepted |

| H15 | CC × RP → BCI | 0.101 | 0.060 | 1.680 | 0.093 | Rejected |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Kamarudin, K.M.; Liu, Y.; Zou, J.; Zhang, J. Developing a Behavior Change Framework for Pandemic Prevention and Control in Public Spaces in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042452

Liu J, Kamarudin KM, Liu Y, Zou J, Zhang J. Developing a Behavior Change Framework for Pandemic Prevention and Control in Public Spaces in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042452

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jing, Khairul Manami Kamarudin, Yuqi Liu, Jinzhi Zou, and Jiaqi Zhang. 2022. "Developing a Behavior Change Framework for Pandemic Prevention and Control in Public Spaces in China" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042452

APA StyleLiu, J., Kamarudin, K. M., Liu, Y., Zou, J., & Zhang, J. (2022). Developing a Behavior Change Framework for Pandemic Prevention and Control in Public Spaces in China. Sustainability, 14(4), 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042452