Association of Oral Health with Multimorbidity among Older Adults: Findings from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, Wave-1, 2017–2019

Abstract

:1. Introduction

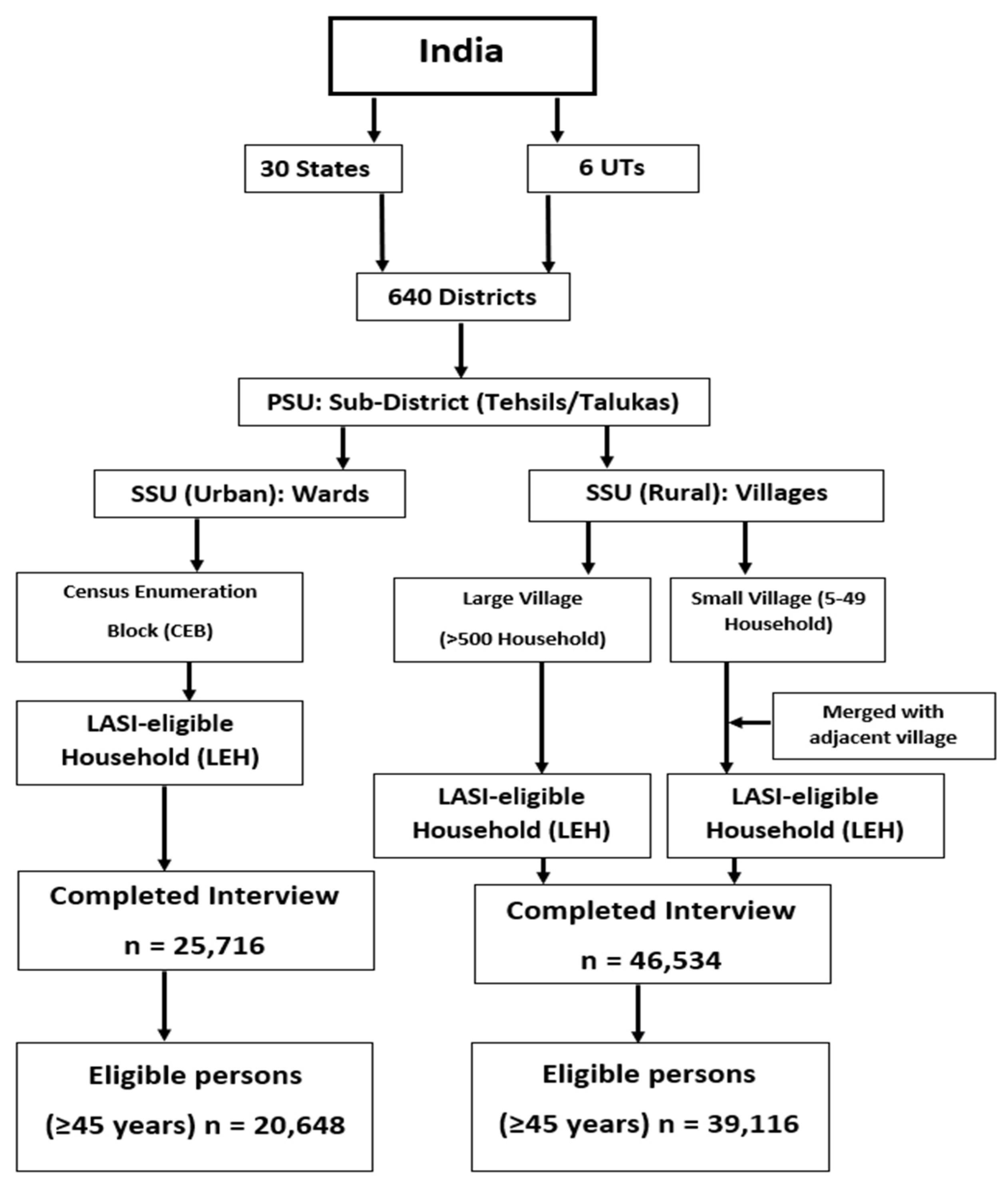

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Participants and Sample Size

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.3.1. Variables

Oral Morbidity

2.4. Exposure Characteristics

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

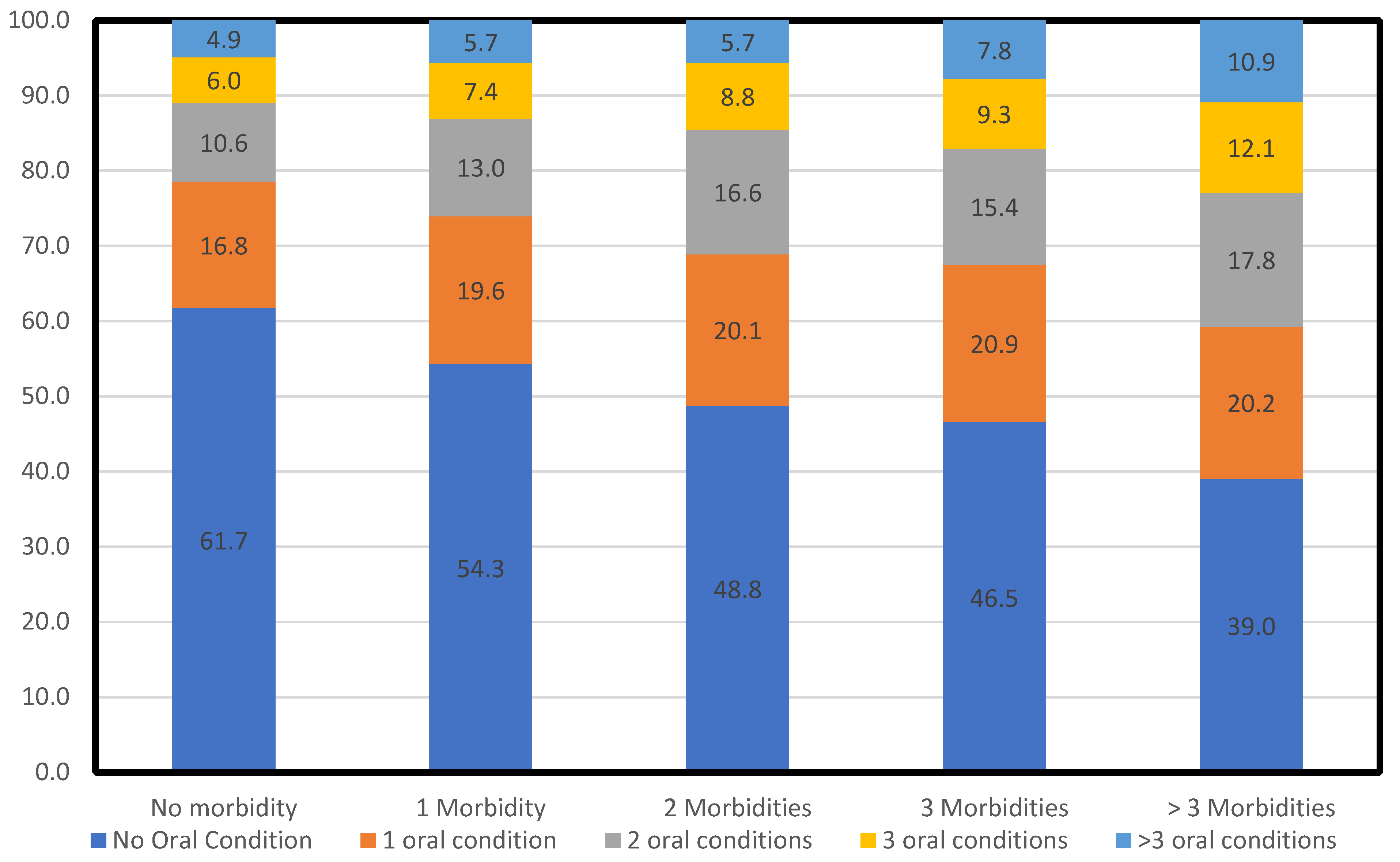

2.5. Multimorbidity

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Considerations

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Number of Oral Morbidities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributes | Categories | None | One Oral Morbidity | Two Oral Morbidities | >Two Oral Morbidities |

| Age groups (n = 59,764) | 45–59 | 16,272, 54.69 (54.12–55.25) | 5437, 18.27 (17.83–18.72) | 3998, 13.44 (13.05–13.83) | 4048, 13.60 (13.22–14.00) |

| 60–74 | 11,149, 47.36 (46.72–48.00) | 4780, 20.31 (19.79–20.83) | 3610, 15.34 (14.88–15.80) | 4000, 16.99 (16.52–17.48) | |

| ≥75 | 3321, 51.34 (50.10–52.55) | 1362, 21.05 (20.06–22.07) | 925, 14.29 (13.45–15.17) | 862, 13.32 (12.50–14.18) | |

| Gender (n = 59,764) | Male | 14,958, 54.58 (53.99–55.17) | 5114, 18.66 (18.20–19.13) | 3783, 13.80 (13.40–14.22) | 3550, 12.95 (12.56–13.36) |

| Female | 15,785, 48.78 (48.23–49.33) | 6465, 19.98 (19.54–20.42) | 4750, 14.68 (14.30–15.07) | 5359, 16.56 (16.16–16.97) | |

| Residence (n = 59,764) | Rural | 21,427, 51.31 (50.83–51.79) | 8091, 19.38 (19.00–19.76) | 5771, 13.82 (13.49–14.15) | 6470, 15.49 (15.15–15.84) |

| Urban | 9315, 51.74 (51.00–52.47) | 3488, 19.37 (18.80–19.96) | 2763, 15.34 (14.82–15.88) | 2439, 13.55 (13.05–14.05) | |

| Regions of India (n = 59,764) | North | 2328, 50.08 (48.63–51.52) | 956, 20.56 (19.41–21.75) | 695, 14.94 (13.94–16.01) | 670, 14.41 (13.41–15.45) |

| Central | 8803, 56.94 (56.15–57.72) | 2369, 15.32 (14.76–15.90) | 1823, 11.79 (11.29–12.31) | 2466, 15.95 (15.38–16.54) | |

| East | 7015, 49.47 (48.64–50.30) | 2496, 17.60 (16.98–18.24) | 1870, 13.19 (12.63–13.76) | 2799, 19.74 (19.09–20.40) | |

| Northeast | 1162, 56.57 (54.40–58.73) | 332, 16.16 (14.60–17.83) | 344, 16.73 (15.16–18.43) | 216, 10.54 (9.22–11.92) | |

| West | 5587, 59.10 (58.11–60.10) | 1502, 15.90 (15.16–16.64) | 1264, 13.38 (12.69–14.08) | 1099, 11.62 (10.99–12.29) | |

| South | 5847, 41.86 (41.04–42.68) | 3924, 28.09 (27.35–28.84) | 2538, 18.17 (17.53–18.82) | 1659, 11.88 (11.35–12.43) | |

| Caste (n = 59,275) | SC | 6021, 52.15 (51.23–53.06) | 2185, 18.92 (18.21–19.65) | 1516, 13.13 (12.52–13.76) | 1825, 15.81 (15.14–16.48) |

| ST | 2813, 55.03 (53.64–56.39) | 878, 17.17 (16.15–18.23) | 677, 13.24 (12.32–14.20) | 745, 14.57 (13.61–15.57) | |

| OBC | 13,437, 49.47 (48.87–50.06) | 5581, 20.55 (20.06–21.03) | 4177, 15.38 (14.95–15.81) | 3968, 14.61 (14.19–15.03) | |

| Others | 8247, 53.37 (52.58–54.16) | 2809, 18.18 (17.57–18.80) | 2103, 13.61 (13.07–14.16) | 2293, 14.48 (14.28–15.41) | |

| Educational Qualification (n = 59,763) | No Formal Education | 15,045, 49.53 (48.97–50.10) | 5939, 19.55 (19.11–20.00) | 4384, 14.43 (14.04–14.83) | 5006, 16.48 (16.07–16.90) |

| Up to Primary School | 7096, 50.96 (50.12–51.79) | 2801, 20.11 (19.45–20.79) | 2020, 14.51 (13.93–15.10) | 2008, 14.42 (13.84–15.01) | |

| Middle School to Higher Secondary | 6663, 53.99 (53.10–54.87) | 2332, 18.89 (18.21–19.60) | 1683, 13.64 (13.04–14.25) | 1664, 13.48 (12.88–14.10) | |

| Diploma, Graduate, and Above | 1937, 62.04 (60.31–63.75) | 508, 16.26 (14.99–17.61) | 445, 14.26 (13.05–15.53) | 232, 7.43 (6.54–8.41) | |

| Employment Status (n = 59,760) | Currently Working | 15,304, 54.80 (54.22–55.39) | 5098, 18.25 (17.80–18.71) | 3859, 13.82 (13.42–14.23) | 3665, 13.12 (12.73–13.53) |

| Currently not Working | 15,435, 48.49 (47.94–49.04) | 6481, 20.36 (19.92–20.81) | 4674, 14.68 (14.30–15.08) | 5244, 16.47 (16.07–16.89) | |

| Life Partner (n = 59,762) | Have a Partner | 23,133, 52.19 (51.72–52.65) | 8437, 19.04 (18.67–19.40) | 6363, 14.35 (14.03–14.68) | 6393, 14.42 (14.10–14.75) |

| Do not Have a Partner | 7608, 49.29 (48.50–50.08) | 3141, 20.34 (19.72–20.99) | 2171, 14.07 (13.52–14.62) | 2516, 16.30 (15.72–16.89) | |

| Wealth Index (n = 59,764) | The most deprived quantile | 6906, 54.73 (53.87–55.62) | 2354, 18.66 (17.98–19.35) | 1523, 12.07 (11.51–12.65) | 1832, 14.52 (13.91–15.15) |

| 2nd quantile | 6622, 52.09 (51.21–52.95) | 2359, 18.55 (17.88–19.24) | 1784, 14.03 (13.43–14.65) | 1950, 15.33 (14.71–15.97) | |

| 3rd quantile | 6205, 50.82 (49.93–51.71) | 2539, 20.79 (20.08–21.53) | 1661, 13.61 (13.00–14.22) | 1805, 14.78 (14.16–15.43) | |

| 4th quantile | 5952, 50.76 (49.85–51.67) | 2290, 19.54 (18.82–20.26) | 1745, 14.88 (14.24–15.54) | 1738, 14.82 (14.18–15.48) | |

| The most affluent quantile | 5056, 48.16 (47.20–49.12) | 2036, 19.40 (18.64–20.16) | 1821, 17.34 (16.62–18.08) | 1586, 15.10 (14.43–15.81) | |

Appendix A.3

| Chronic Conditions | Male | Female | Total (n, 100%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 95% CI | n (%) | 95% CI | ||

| Hypertension (n = 59,745) | 6242 (38.47) | (37.72–39.22) | 9984 (61.53) | (60.78–62.28) | 16,226 |

| Diabetes (n = 59,744) | 3285 (45.90) | (44.75–47.07) | 3871 (54.10) | (52.93–55.25) | 7156 |

| Cancer (n = 59,752) | 130 (34.66) | (29.85–39.72) | 245 (65.34) | (60.28–70.14) | 375 |

| Chronic Lung Diseases (n = 59,753) | 1997 (50.31) | (48.75–51.88) | 1972 (49.69) | (48.12–51.25) | 3969 |

| Chronic Heart Diseases (n = 59,753) | 1143 (49.82) | (47.76–51.89) | 1151 (50.18) | (48.11–52.24) | 2294 |

| Stroke (n = 59,752) | 655 (59.86) | (56.90–62.79) | 439 (40.14) | (37.21–43.10) | 1094 |

| Arthritis and Other Bone/Joint Diseases (n = 59,754) | 3581 (36.54) | (35.59–37.51) | 6218 (63.46) | (62.49–64.41) | 9799 |

| Neurological and Psychological Problems (n = 59,745) | 637 (45.83) | (43.18–48.49) | 753 (54.17) | (51.51–56.82) | 1390 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (n = 59,752) | 631 (45.49) | (42.82–48.12) | 757 (54.51) | (51.88–57.18) | 1388 |

| Chronic Renal Failure (n = 59,764) | 224 (56.46) | (51.39–61.36) | 173 (43.54) | (38.64–48.61) | 397 |

| Thyroid Disorder (n = 59,764) | 338 (20.31) | (18.39–22.31) | 1327 (79.69) | (77.69–81.61) | 1665 |

| Gastrointestinal Problems (n = 59,764) | 5103 (46.80) | (45.85–47.74) | 5802 (53.20) | (52.26–54.15) | 10,905 |

| Skin Diseases (n = 59,764) | 1527 (49.27) | (47.50–51.05) | 1572 (50.73) | (48.95–52.50) | 3099 |

| Vision Defect (n = 59,756) | 13,084 (45.59) | (45.01–46.17) | 15,614 (54.41) | (53.83–54.99) | 28,698 |

| Hearing Defect (n = 59,757) | 1831 (45.73) | (44.17–47.28) | 2174 (54.27) | (52.72–55.83) | 4005 |

| Obesity (n = 59,073) | 5783 (36.14) | (35.40–36.89) | 10,219 (63.86) | (63.11–64.61) | 16,001 |

| Oral Problems (n = 59,764) | 12,448 (42.89) | (42.32–43.46) | 16,574 (57.11) | (56.54–57.68) | 29,022 |

Appendix A.4

| Disease Groups | Soft Tissue n (%) | Hard Tissue n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Neoplasms | 163 (43.52) | 189 (50.23) |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic | 7280 (35.36) | 8250 (40.08) |

| Mental and behavioural | 667 (47.97) | 666 (47.91) |

| Diseases of the eye and adnexa | 10,852 (37.81) | 11,608 (40.45) |

| Ear | 1878 (46.90) | 2022 (50.47) |

| Circulatory system | 6961 (39.98) | 7288 (41.86) |

| Respiratory system | 1695 (42.70) | 1893 (47.70) |

| Digestive system | 4986 (45.72) | 5336 (48.94) |

| Skin | 1303 (42.05) | 1453 (46.88) |

| Musculoskeletal | 4704 (48.01) | 4838 (49.38) |

| Genitourinary | 191 (48.13) | 192 (48.39) |

References

- Panchbhai, A.S. Oral health care needs in the dependant elderly in India. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2012, 18, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects—Population Division. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Petersen, P.E.; Yamamoto, T. Improving the oral health of older people: The approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2005, 33, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcenes, W.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabé, E.; Flaxman, A.; Naghavi, M.; Lopez, A.; Murray, C.J.L. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: A systematic analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sisson, K.L. Theoretical explanations for social inequalities in oral health. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, S.O.; Barker, L.K.; Griffin, P.M.; Cleveland, J.L.; Kohn, W. Oral health needs among adults in the United States with chronic diseases. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2009, 140, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, V.M.; Kennedy, A.D.; Panagakos, F.; Devizio, W.; Trivedi, H.M.; Jönsson, T.; Guo, L.; Cervi, S.; Scannapieco, F.A. Global metabolomic analysis of human saliva and plasma from healthy and diabetic subjects, with and without periodontal disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scannapieco, F.A.; Bush, R.B.; Paju, S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for nosocomial bacterial pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review. Ann. Periodontol. 2003, 8, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacMahon, S. Multimorbidity: A Priority for Global Health Research; The Academy of Medical Sciences: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R.; Chahande, J.; Banerjee, S.; Radke, U. Evaluation of relationship between nutritional status and oral health related quality of life in complete denture wearers. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Swain, S.; Hussain, M.A.; Kadam, S.; Salisbury, C. Prevalence, correlates, and outcomes of multimorbidity among patients attending primary care in Odisha, India. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gambhir, R.; Gupta, T. Need for Oral Health Policy in India. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2016, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI). Available online: https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/lasi (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Arokiasamy, P. India’s escalating burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1262–e1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhawan, D.; Sharma, S. Abdominal Obesity, Adipokines and Non-communicable Diseases. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 203, 105737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, B.; Ravi Kumar, B.; Goswami, A.; Mathur, V.; Nongkynrih, B. Prevalence of dental caries among adults and elderly in an urban resettlement colony of New Delhi. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2008, 19, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, M.; Bhat, S.; Brondani, M.; Mejia, G.C.; Pradhan, A.; Roberts-Thomson, K.; Do, L.G. Prevalence, Extent, and Severity of Oral Health Impacts Among Adults in Rural Karnataka, India. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2021, 6, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Ferrucci, L.; Mercer, S.W.; Marengoni, A.; Onder, G.; Eriksdotter, M.; Fratiglioni, L. Multimorbidity and functional impairment—bidirectional interplay, synergistic effects and common pathways. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Putten, G.J.; de Baat, C.; De Visschere, L.; Schols, J. Poor oral health, a potential new geriatric syndrome. Gerodontology 2014, 31, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pati, S.; Swain, S.; Hussain, M.A.; Van Den Akker, M.; Metsemakers, J.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Salisbury, C. Prevalence and outcomes of multimorbidity in South Asia: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Veronese, N.; Schofield, P.; Lin, P.Y.; Tseng, P.T.; Solmi, M.; Thompson, T.; Carvalho, A.F.; Koyanagi, A. Multimorbidity and perceived stress: A population-based cross-sectional study among older adults across six low- and middle-income countries. Maturitas 2018, 107, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, R.G.; Serban, S. Multimorbidity: A challenge and opportunity for the dental profession. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 229, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islas-Granillo, H.; Borges-Yañez, S.A.; de Jesús Navarrete-Hernández, J.; Veras-Hernández, M.A.; Casanova-Rosado, J.F.; Minaya-Sánchez, M.; Casanova-Rosado, A.J.; Fernández-Barrera, M.Á.; Medina-Solís, C.E. Indicators of oral health in older adults with and without the presence of multimorbidity: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hilmer, S.N.; Gnjidic, D. Prescribing for frail older people. Aust. Prescr. 2017, 40, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jacob, L.; López-Sánchez, G.F.; Carvalho, A.F.; Shin, J.I.; Oh, H.; Yang, L.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P.; Grabovac, I.; Koyanagi, A.; et al. Associations between mental and oral health in Spain: A cross-sectional study of more than 23,000 people aged 15 years and over. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Attributes | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (n = 59,764) | |

| Mean (± SD): 60.22 (±10.64) years, Range: 45 to 116 years. | |

| 45–59 | 29,756 (49.79) |

| 60–74 | 23,539 (39.39) |

| ≥75 | 6469 (10.82) |

| Gender (n = 59,764) | |

| Male | 27,405 (45.86) |

| Female | 32,359 (54.14) |

| Residence (n = 59,764) | |

| Rural | 41,759 (69.87) |

| Urban | 18,005 (30.13) |

| Regions of India (n = 59,764) | |

| North | 4649 (7.78) |

| Central | 15,461 (25.87) |

| East | 14,180 (23.73) |

| Northeast | 2054 (3.44) |

| West | 9452 (15.82) |

| South | 13,968 (23.37) |

| Caste (n = 59,275) | |

| SC | 11,547 (19.48) |

| ST | 5113 (8.63) |

| OBC | 27,162 (45.83) |

| Others | 15,452 (26.07) |

| Educational Qualification (n = 59,763) | |

| No formal Education | 30,375 (50.82) |

| Up to Primary school | 13,925 (23.30) |

| Middle school to Higher Secondary | 12,342 (20.65) |

| Diploma, Graduate, and Above | 3122 (5.22) |

| Employment Status (n = 59,760) | |

| Currently working | 27,926 (46.73) |

| Currently not working | 31,834 (53.27) |

| Life Partner (n = 59,762) | |

| Have a partner | 44,326 (74.17) |

| Does not have a partner | 15,436 (25.83) |

| Wealth Index (n = 59,764) | |

| The most deprived quantile | 12,615 (21.11) |

| 2nd quantile | 12,715 (21.27) |

| 3rd quantile | 12,210 (20.43) |

| 4th quantile | 11,725 (19.62) |

| The most affluent quantile | 10,499 (17.57) |

| Correlates | Oral Morbidity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Morbidity | Categories | AOR (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value |

| Age (n = 59,764) | 45–59 | Reference | |

| 60–74 | 1.27 (1.18–1.37) | <0.001 | |

| ≥75 | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) | 0.701 | |

| Gender (n = 59,764) | Male | Reference | |

| Female | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | <0.001 | |

| Residence (n = 59,764) | Rural | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 0.216 |

| Urban | Reference | ||

| Regions of India (n = 59,764) | North | 1.38 (1.26–1.52) | <0.001 |

| Central | 1.19 (1.09–1.30) | <0.001 | |

| East | 1.52 (1.39–1.67) | <0.001 | |

| Northeast | 1.21 (1.09–1.34) | <0.001 | |

| South | 2.00 (1.77–2.26) | <0.001 | |

| West | Reference | ||

| Caste (n = 59,275) | SC | Reference | |

| ST | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) | 0.298 | |

| OBC | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | 0.192 | |

| Others | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 0.980 | |

| Educational Qualification (n = 59,763) | No formal Education | 1.84 (1.44–2.36) | <0.001 |

| Up to Primary school | 1.71 (1.33–2.20) | <0.001 | |

| Middle school to Higher Secondary | 1.49 (1.14–1.94) | 0.004 | |

| Diploma, Graduate, and Above | Reference | ||

| Employment Status (n = 59,760) | Currently working | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) | 0.052 |

| Currently not working | Reference | ||

| Life Partner (n = 59,762) | Have a Partner | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 0.185 |

| Do not have a Partner | Reference | ||

| Wealth Index (n = 59,764) | The most deprived quantile | Reference | |

| 2nd quantile | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 0.038 | |

| 3rd quantile | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) | 0.017 | |

| 4th quantile | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 0.036 | |

| The most affluent quantile | 1.22 (1.09–1.38) | 0.001 | |

| Multimorbidity (n = 59,764) | Absent | Reference | |

| Present | 1.60 (1.48–1.73) | <0.001 | |

| Self-Rated Health | Oral Morbidity (n = 59,745) | Mantel Haenszel Chi-Square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||||

| Multimorbidity Present n, % (CI) | Multimorbidity Absent n, % (CI) | Multimorbidity Present n, % (CI) | Multimorbidity Absent n, % (CI) | p-Value | |

| Excellent | 382, 2.32 (2.10–2.56) | 486, 3.87 (3.53–4.22) | 549, 4.03 (3.70–4.37) | 1058, 6.20 (5.84–6.57) | <0.001 |

| Very Good | 1912, 11.62 (11.14–12.12) | 2312, 18.38 (17.71–19.07) | 2269, 16.64 (16.01–17.27) | 3974, 23.27 (22.64–23.92) | |

| Good | 5425, 32.98 (32.26–33.71) | 5138, 40.84 (39.99–41.71) | 4592, 33.66 (32.87–34.46) | 7295, 42.72 (41.98–43.47) | |

| Fair | 5960, 36.23 (35.50–36.98) | 3636, 28.90 (28.12–29.71) | 4354, 31.92 (31.13–32.71) | 3794, 22.22 (21.60–22.85) | |

| Poor | 2770, 16.84 (16.27–17.42) | 1007, 8.01 (7.54–8.49) | 1878, 13.76 (13.19–14.36) | 955, 5.59 (5.25–5.95) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanungo, S.; Ghosal, S.; Kerketta, S.; Sinha, A.; Mercer, S.W.; Lee, J.T.; Pati, S. Association of Oral Health with Multimorbidity among Older Adults: Findings from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, Wave-1, 2017–2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312853

Kanungo S, Ghosal S, Kerketta S, Sinha A, Mercer SW, Lee JT, Pati S. Association of Oral Health with Multimorbidity among Older Adults: Findings from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, Wave-1, 2017–2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312853

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanungo, Srikanta, Shishirendu Ghosal, Sushmita Kerketta, Abhinav Sinha, Stewart W Mercer, John Tayu Lee, and Sanghamitra Pati. 2021. "Association of Oral Health with Multimorbidity among Older Adults: Findings from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, Wave-1, 2017–2019" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312853

APA StyleKanungo, S., Ghosal, S., Kerketta, S., Sinha, A., Mercer, S. W., Lee, J. T., & Pati, S. (2021). Association of Oral Health with Multimorbidity among Older Adults: Findings from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, Wave-1, 2017–2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312853