An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of Polish Street Food Vendors in Selected Food Trucks and Stands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- −

- What are the hygiene conditions of food production and distribution in Polish street food facilities?

- −

- Do employees of street food facilities use personal hygiene practices in food production and distribution?

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Questionnaire Design

- Sanitary conditions of food production (Q.1.1–Q.1.11). This section included 11 questions about the general hygiene condition of the facility where the production processes were performed.

- Hygiene of food production and distribution processes (Q.2.1–Q.2.13). This section included 13 questions related to hygienic production and distribution processes, visual assessment of the quality of raw materials and finished products, as well as the sanitary condition of equipment used.

- Personal hygiene of staff (Q.3.1–Q.3.22). This section included 22 questions related to staff hygiene.

3.3. Characteristics of Street Food Outlets

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

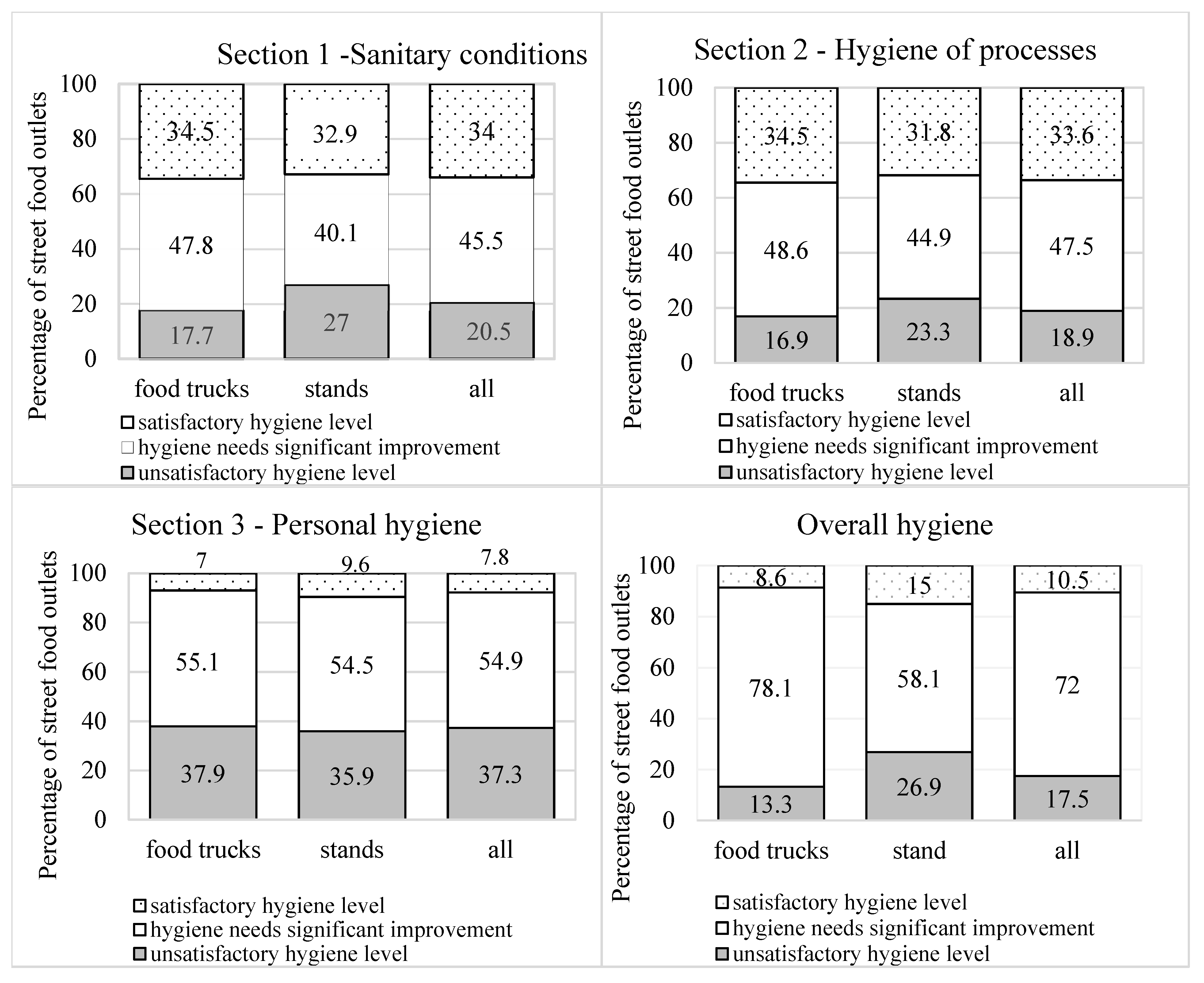

4.1. Sanitary Conditions and Hygiene of Food Production and Distribution in Street Food Outlets

4.2. Personal Hygiene of Staff in Street Food Outlets

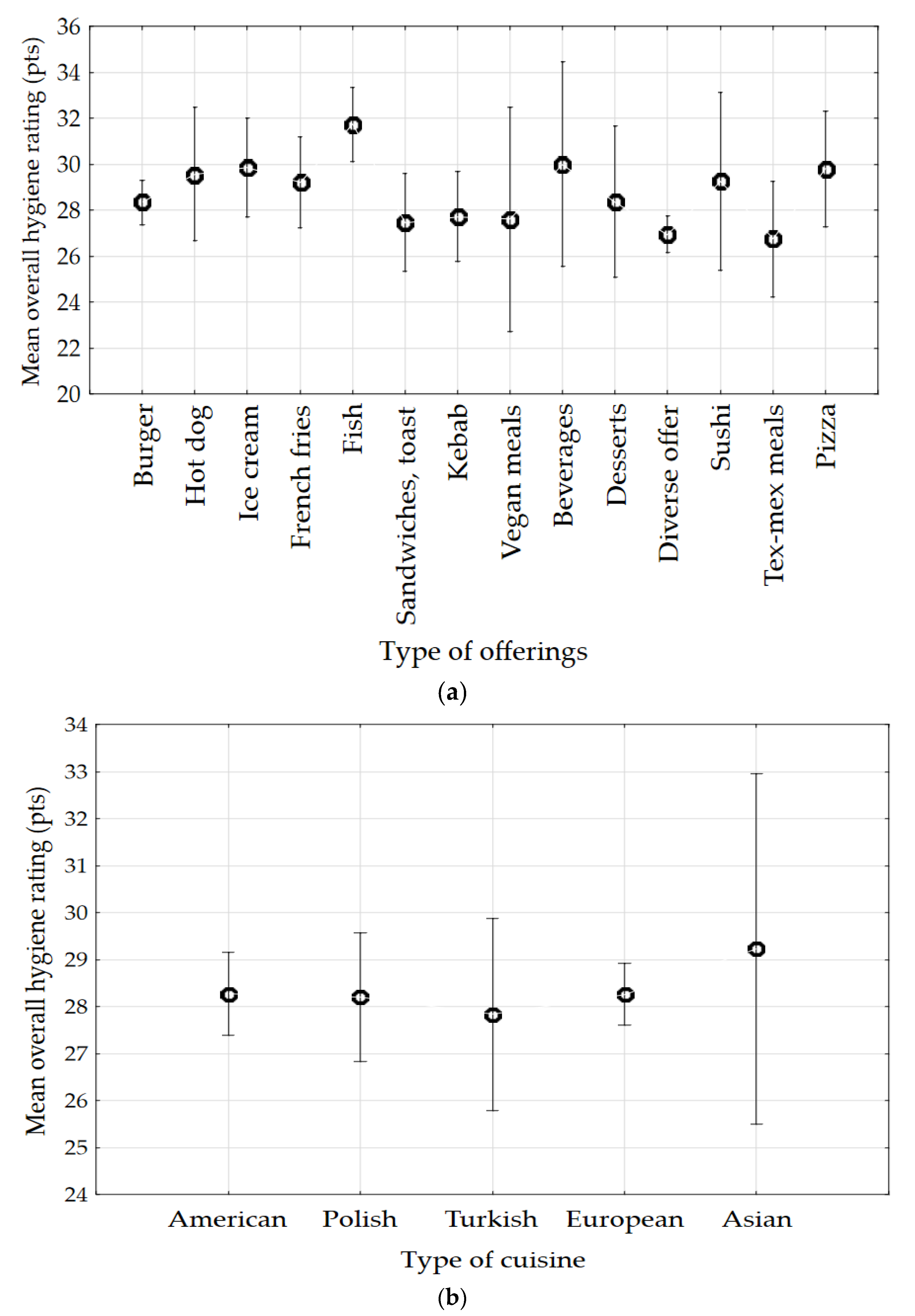

4.3. Overall Assessment of Hygiene of Street Food Vendors in Poland

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mchiza, Z.; Hill, J.; Steyn, N. Foods Currently Sold by Street Food Vendors in the Western Cape, South Africa, Do not foster Good Health. In Fast Foods: Consumption Patterns, Role of Globalization and Health Effects; Sanford, M.G., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2014; Chapter 4; pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Essential Safety Requirements for Street-Vended Foods, Food Safety Unit Division of Food and Nutrition; WHO/ FNU/FOS/96.7; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Street Foods. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper N. 63. Report of an FAO Technical Meeting on Street Foods, Calcutta, India, 6–9 November 1995. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 1997. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/W4128T/W4128T00.htm/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Bromley, R. Street vending and public policy: A global review. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2000, 20, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Good Hygienic Practices in the Preparation and Sale of Street Food in Africa; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2009; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/a0740e/a0740e00.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Fellows, P.; Hilmi, M. Selling Street and Snack Foods. FAO Diversification Booklet No 18; Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2012; Available online: https://www.fao.org/docrep/015/i2474e/i2474e00.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- da Silva, S.A.; Cardoso, R.C.V.; Góes, J.T.W.; Santos, J.N.; Ramos, F.P.; Bispo de Jesus, R.; Sabá do Vale, R.; Teles da Silva, P.S. Street food on the coast of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil: A study from the socioeconomic and food safety perspectives. Food Control. 2014, 40, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfiero, S.; Lo Giudice, A.; Bonadonna, A. Street food and innovation: The food truck phenomenon. BFJ 2017, 119, 2462–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Privitera, D.; Nesci, F.S. Globalization vs. local. The role of street food in the urban food system. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 22, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khairatun, S.N. International culinary influence on street food: An observatory study. J. Sustain. Tour. Entrepr. 2020, 1, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigüler, F.; Öztürk, B. Street Food as a Gastronomic Tool in Turkey. In Proceedings of the International Gastronomic Tourism Congress Proceedings, Izmir, Turkey, 8–10 December 2016; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kraig, B.; Sen, C.T. Street Food around the World. In An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture; ABC-CLIO, LLC: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, R.D.C.V.; Companion, M.; Marras, S.R. Street Food: Culture, Economy, Health and Governance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A. Od street food do food districts—Usługi gastronomiczne i turystyka kulinarna w przestrzeni miasta. Tur. Kulinarna 2014, 9, 6–31. [Google Scholar]

- Azanza, M.P.V.; Gatchalian, C.F.; Melba, P.O. Food safety knowledge and practices of street food vendors in a Philippines university campus. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2000, 51, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankee, A.; Ali, S.; Chin, A.; Indalsingh, R.; Khan, R.; Mohammed, F.; Rahman, R.; Sooknanan, S.; Tota-Maharaj, R.; Simeon, D.; et al. Bacteriological quality of ‘‘doubles’’ sold by street vendors in Trinidad and the attitudes, knowledge and perceptions of the public about its consumption and health risk. Food Microb. 2003, 20, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrie, N.; Joseph, A.; Chen, A. An observational study of food safety practices by street vendors and microbiological quality of street-purchased hamburger beef patties in Trinidad, West Indies. Internet J. Food Saf. 2004, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lues, J.F.R.; Rasephei, M.R.; Venter, P.; Theron, M.M. Assessing food safety and associated food handling practices in street food vending. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2006, 16, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukuezi, C.O. Food Safety and Hyienic Practices of Street Food Vendors in Owerri, Nigeria. Stud. Sociol. Sci. 2010, 1, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackah, M.; Gyamfi, E.T.; Anim, A.K.; Osei, J.; Hansen, J.K.; Agyemang, O. Socio-Economic Profile, Knowledge of Hygiene and Food Safety Practices among Street-Food Vendors in some parts of Accra-Ghana. Internet J. Food Saf. 2011, 13, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, M.; Mahanta, L.; Oswami, J.G.; Mazumder, M.; Pegoo, B. Socio-economic profile and food safety knowledge and practice of street food vendors in the city of Guwahati, Assam, India. Food Control. 2011, 22, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.; Mahanta, L.B.; Goswami, J.S.; Mazumder, M.D. Will capacity building training interventions given to street food vendors give us safer food? A cross-sectional study from India. Food Control. 2011, 22, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, S. Street vended food in developing world: Hazard analyses. Indian J. Microb. 2011, 51, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feglo, P.; Sakyi, K. Bacterial contamination of street vending food in Kumasi, Ghana. J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2012, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Taha Arif, M.; Bakar, K.; bt Tambi, Z. Food safety knowledge, attitude and hygiene practices among the street food vendors in Northern Kuching city, Sarawak. Borneo Sci. 2012, 31, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Eshraga Abdallah Ali Elneim. Practice in the Preparation, Handling and Storage of Street Food Vendors Women in Sinja City (Sudan). Inter. J. Sc. Res. 2013, 2, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Monney, I.; Agyei, D.; Owusu, W. Hygienic Practices among Food Vendors in Educational Institutions in Ghana: The Case of Konongo. Foods 2013, 2, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thakur, C.P.; Mehra, R.; Narula, C.; Mahapatra, S.; Kalita, T.J. Food safety and hygiene practices among street food vendors in Delhi, India. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2013, 5, 3531–3534. [Google Scholar]

- Blaise, N.Y. An Assessment of Hygiene Practices and Health Status of Street-food vendors in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health 2014, 4, 1153–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, D.T.; Stedefeldt, E.; de Rosso, V.V. The role of theoretical food safety training on Brazilian food handlers’ knowledge, attitude and practice. Food Control. 2014, 43, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadaga, T.H.; Ntsike, M.M.; Ntuli, V. Socio-economic and hygienic aspects of street food vending in Maseru City, Lesotho. UNISWA J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2014, 15, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Khairuzzaman, M.; Chowdhury, F.M.; Zaman, S.; Al Mamun, A.; Bari, M.D.L. Food Safety Challenges towards Safe, Healthy, and Nutritious Street Foods in Bangladesh. Int. J. Food Sci. 2014, 2014, 483519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kok, R.; Balkaran, R. Street Food Vending and Hygiene Practices and Implications for Consumers. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2014, 6, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okojie, P.W.; Isah, E.C. Sanitary Conditions of Food Vending Sites and Food Handling Practices of Street Food Vendors in Benin City, Nigeria: Implication for Food Hygiene and Safety. J. Environ. Public Health 2014, 2014, 701316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanschaik, B.; Tuttle, J.L. Mobile food trucks: California EHS-net study on risk factors and inspection challenges. J. Environ. Health 2014, 76, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, J.P.L.; Pedalgo, C.C.; Zafra, A.R.N.; Tuzon, T.P. The perception of local street food vendors of Tanauan city, Batangas on food safety. LPU–Laguna J. Inter. Tour. Hospit. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, J.; Gil, J.; Mourão, J.; Peixe, L.; Antunes, P. Ready-to-eat street-vended food as a potential vehicle of bacterial pathogens and antimicrobial resistance: An exploratory study in Porto region, Portugal. Int. J. Food Microb. 2015, 206, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, D.T.; Braga, A.R.C.; de Camargo, P.E.; Stedefeldt, E.; de Rosso, V.V. The existence of optimistic bias about foodborne disease by food handlers and its association with training participation and food safety performance. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, G.C.; dos Santos, C.T.B.; Andrade, A.A.; Alves, L. Street food: Analysis of hygienic and sanitary conditions of food handlers/Comida de rua: Avaliacao das condicoes higienico-sanitarias de manipuladores de alimentos. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2015, 20, 2329–2333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samapundo, S.; Climat, R.; Xhaferi, R.; Devlieghere, F. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of street food vendors. and consumers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Food Control. 2015, 50, 457.e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, R.D.M.; Veiros, M.B.; Feldman, C.; Cavalli, S.B. Food safety and hygiene practices of vendors during the chain of street food production in Florianopolis, Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Food Control. 2016, 62, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dun-Dery, E.J.; Addo, H.O. Food Hygiene Awareness, Processing and Practice among Street Food Vendors in Ghana. Food Public Health 2016, 6, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, C.I.; Schild, C.H.; Tondo, E.C.; da Silva Malheiros, P. Microbiological contamination and evaluation of sanitary conditions of hot dog street vendors in Southern Brazil. Food Control. 2016, 62, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Dudeja, P.; Kaushal, N.; Mukherji, S. Impact of health education intervention on food safety and hygiene of street vendors: A pilot study. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2016, 72, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calopez, C.G.; Herbalega, C.M.L.; Canonicato, C.J.; Españo, M.F.; Francisco, A.J.M. Food Safety Awareness and Practices of Street Food Vendors in Iloilo City. In Proceedings of the CEBU International Conference on Studies in Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (SASSH-17), Cebu, Philippines, 26–27 January 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, B.; Fenteng, R. An Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Practices of Street Food Vendors at Takoradi Market Circle. Saudi J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, A.C.; Şanlıer, N. Street food consumption in terms of the food safety and health. J. Hum. Sci. 2016, 13, 4072–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ImathIu, S. Street Vended Foods: Potential for Improving Food and Nutrition Security or a Risk Factor for Foodborne Diseases in Developing Countries? Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 5, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, N.P. Food Safety Knowledge and Hygiene Practice of Street Vendors in Mekong River Delta Region. Biotech. Ind J. 2017, 13, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Alamo-Tonelada, P.C.; Silaran, M.F.; Bildan, M.M. Sanitary conditions of food vending sites and food handling practices of street food vendors: Implication for food hygiene and safety. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Trafiałek, J.; Wiatrowski, M.; Głuchowski, A. An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of European Street Food Vendors and a Preliminary Estimation of Food Safety for Consumers, Conducted in Paris. J. Food Protect. 2018, 81, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odundo, A.; Okemo, P.; Chege, P. An Assessment of Food Safety Practices among Street Vendors in Mombasa, Kenya. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2018, 8, 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, N.P.; Chaturvedani, A.K. Food Safety and Hygiene Practices among Street Food Vendors in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2018, 7, 2340–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafialek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Laskowski, W.; Jakubowska-Gawlik, K.; Tzamalis, P.; Leksawasdi, N.; Surawang, S.; Kolanowski, W. Street food vendors’ hygienic practices in some Asian and EU countries—A survey. Food Control. 2018, 85, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyia Evert, N.; Odikpo, L.C.; Ehiemere, I.; Ihudiebube, S.; Chikaodili, N.; Ikeh Uchechukwu, A. ffect of Health Education on Food Hygiene Practices and Personal Hygiene Practices of Food Vendors in Public Secondary Schools at Oshimili South Local Government Area. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2019, 8, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nyoni, T.; Bonga, W.G. Hygienic Practices of Street Food Vendors in Zimbabwe: A Case of Harare. DRJ’s J. Econ. Financ. 2019, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Addo-Tham, R.; Appiah-Brempong, E.; Vampere, H.; Acquah-Gyan, E.; Gyimah Akwasi, A. Knowledge on Food Safety and Food-Handling Practices of Street Food Vendors in Ejisu-Juaben Municipality of Ghana. Adv. Public Health 2020, 2020, 4579573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birgen, B.J.; Njue, L.G.; Kaindi, D.M.; Ogutu, F.O.; Owade, J.O. Determinants of Microbial Contamination of Street-Vended Chicken Products Sold in Nairobi County, Kenya. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 2746492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hassan, J.K.; Fweja, L.W.T. Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Compliance to Hygienic Practices among Street Food Vendors in Zanzibar Urban District. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.K.; Fweja, L.W.T. Food Hygienic Practice.es and Safety Measures among Street Food Vendors in Zanzibar Urban District. eFood 2020, 1, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htway, T.A.S.; Kallawicha, K. Factors associated with food safety knowledge and practice among street food vendors in Taunggyi Township, Myanmar: A cross-sectional study. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2020, 20, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuluse, D.S.; Deen, A. Hygiene and Safety Practices of Food Vendors. Afr. J. Hospit. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutha, K.J.; Chelule, P.K. Safe Food Handling Knowledge and Practices of Street Food Vendors in Polokwane Central Business District. Foods 2020, 9, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letuka, P.; Nkhebenyane, S.; Thekisoe, O. Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices among Street Food Vendors and Consumers’Perceptions of Street Food Vending in Maseru Lesotho. Preprints 2019, 2019050257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwove, J.; Imathiu, S.; Orina, I.; Karanja, P. Food safety knowledge and practices of street food vendors in selected locations within Kiambu County, Kenya. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2020, 14, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.S. Food safety knowledge of street food vendors in downtown Amman—Jordan. Eurasia J. Biosci 2020, 14, 3601–3606. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye, A.; Tegene, Y. Assessment of Food Hygiene and Safety Practices among Street Food Vendors and its Associated Factors in Urban Areas of Shashemane, West Arsi Zone, Oromia Ethiopia, 2019. Sci. J. Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Obinda, D.K.; Njue, L.; Abong, G.O.; Owade, J.O. Food Safety Knowledge and Hygienic Practices among Vendors of Vegetable Salads in Pipeline Ward of Nairobi County, Kenya. E. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2021, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nkosi, N.V.; Tabit, F.T. The food safety knowledge of street food vendors and the sanitary conditions of their street food vending environment in the Zululand District, South Africa. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchigui Manga Maffouo, S.; Tene Mouafo, H.; Simplice Mouokeu, R.; Manet, L.; Kamgain Tchuenchieu, A.; Noutsa Simo, B.; Tchuitcheu Djeuachi, H.; Nama Medoua, G.; Tchoumbougnang, F. Evaluation of sanitary risks associated with the consumption of street food in the city of Yaoundé (Cameroon): Case of braisedfish from Mvog-Ada, Ngoa Ekélé, Simbock, Ahala and Olézoa. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuglo, L.S.; Delali Agordoh, P.D.; Tekpor, D.; Pan, Z.; Agbanyo, G.; Chu, M. Food safety knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices of street-cooked food handlers in North Dayi District, Ghana. Environ. Health Prevent. Med. 2021, 26, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, J.; Asmat, T.M.; Mustafaa, M.Z.; Ishtiaq, H.; Mumtazd, K.; Jalees, M.M.; Samad, A.; Shah, A.A.; Khalid, S.; ur Rehman, H. Contamination of ready-to-eat street food in Pakistan with Salmonella spp.: Implications for consumers and food safety. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamandane, A.; Silva, A.C.; Brito, L.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M. Microbiological assessment of street foods at the point of sale in Maputo (Mozambique). Food Qual. Saf. 2021, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollaard, A.M.; Ali, S.; van Asten, H.A.G.H.; Suhariah Ismid, I.; Widjaja, S.; Visser, L.G.; Surjadi, C.; van Dissel, J.T. Risk factors for transmission of foodborne illness in restaurants and street vendors in Jakarta, Indonesia. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004, 132, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, M.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Turin, T.C. Microbiological quality of selected street food items vended by school based street food vendors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, I.; Mazumdar, J.A. Assessment of bacteriological quality of ready to eat food vended in streets of Silchar city, Assam, India. Indian J. Med. Microb. 2014, 32, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X. Urban street foods in Shiziazhuand City, China: Current status, safety practices and risk mitigating strategies. Food Control. 2014, 41, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Nawawee, N.S.; Abu Bakar, N.F.; Zulfakar, S.S. Microbiological Safety of Street-Vended Beverages in Chow Kit, Kuala Lumpur. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gadaga, T.H.; Samende, B.K.; Musuna, C.; Chibanda, D. The microbiological quality of informally vended foods in Harare, Zimbabwe. Food Control. 2008, 19, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, O.O.; Ojeremi, T.T.; Olakele, D.A.; Ajidagba, E.B. Evaluation of food safety and sanitary practices among food vendors at car parks in Ile Ife, southwestern Nigeria. Food Control. 2014, 40, 165e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annor, G.A.; Baiden, E.A. Evaluation of food hygiene knowledge attitudes and practices of food handlers in food businesses in Accra, Ghana. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 2, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.M.; Wang, S.T.; Huang, K.W. Hygiene knowledge and practices of night market food vendors in Tainan City, Taiwan. Food Control. 2012, 23, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandesso, F.; Allan, M.; Jean-Simon, P.S.J.; Boncy, J.; Blake, A.; Pierre, R.; Alberti, K.P.; Munger, A.; Elder, G.; Olson, D.; et al. Risk factors for cholera transmission in Haiti during inter-peak periods: Insights to improve current control strategies from two case-control studies. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auad, L.I.; Ginani, V.C.; Stedefeldt, E.; Nakano, E.Y.; Santos Nunes, A.C.; Zandonad, R.P. Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Brazilian Food Truck Food Handlers. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Auad, L.I.; Ginani, V.C.; dos Santos Leandro, E.; Nunes, A.C.S.; Junior, L.R.P.D.; Zandonadi, R.P. Who is serving us? Food safety rules compliance among Brazilian food truck vendors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Soares, I.S.; Almeida, R.C.C.; Cerqueira, E.S.; Carvalho, J.S.; Nunes, I.I. Knowledge, attitudes and practices in food safety and the presence of coagulase positive, staphylococci on hands of food handlers in the schools of Camaçari, Brazil. Food Control. 2012, 27, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campos, G.S.; Bandeira, A.C.; Sardi, S.I. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1885–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumus, B.; Sonmez, S. An analysis on current food regulations for and inspection challenges of street food; Case of Florida. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2018, 17, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafiałek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Kolanowski, W. Evaluation of street food vendors’ hygienic practices using fast observation questionnaire. Food Control. 2017, 80, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafiałek, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Pałubicki, B.; Makuszewska, K. Higiena w zakładach gastronomicznych wytwarzających żywność w obecności konsumenta. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2015, 22, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omemu, A.M.; Aderoju, S.T. Food safety knowledge and practices of street food vendors in the city of Abeokuta, Nigeria. Food Control. 2008, 19, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyanja, C.; Nayiga, L.; Brenda, N.; Nasinyama, G. Practices, knowledge and risk factors of street food vendors in Uganda. Food Control. 2011, 22, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjya, H.; Reang, T. Safety of street foods in Agartala, North East India. Public Health 2014, 128, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.A.; Kurien, T.T.; Huppatz, C. Hepatitis A outbreak associated with kava drinking. Comm. Dis. Intell. Q. Rep. 2014, 38, E26–E28. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, D.; Dennis, M.; Suci Hardianti, M.; Sigit-Sedyabuti, F.M.C. Mounting and Effective Response an Outbreak of Viral Disease Involving Street Food Vendors in Indonesia. In Case Studies in Food Safety and Authenticity. Lessons from Real-Life Situations; Hoorfar, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Chapter 18; pp. 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murindamombe, G.Y.; Collison, E.K.; Mpuchane, S.F.; Gashe, B.A. Presence of Bacillus cereus in street foods in Gaborone, Botswana. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheinhälder, T.; Olsen, M.; Bakang, J.K.; Takay, H.; Konradsen, F.; Samuelsen, H. Keeping up appearances: Perceptions of street food safety in Urban Kumasi, Ghana. J. Urban. Health 2008, 85, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FSA–Food Standard Agency. Safer Food, Better Business. 2016. Available online: http://www.food.gov.uk/business-industry/sfbb (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- USDA–United States Department of Agriculture. Food Truck Programs. 2017. Available online: https:// usdaresearch.usda.gov/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&affiliate=usda&query=food+truck+programs&commit=Search (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- CDC-Centers of Disease Control and Prevention-CDC. Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Poona Infections Linked to Imported Cucumbers (Final Update) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/salmonelle/poona-09–15/index.html (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- INFOSAN–International Food Safety Authorities Network. Basic Steps to Improve Safety of Street-Vended Food; Note No 3/2010–Safety of Street-Vended Food; WHO, INFOSAN Information: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, C.P. The impact of food manufacturing practices on food borne diseases. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2008, 51, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ismail, F.H.; Chik, C.T.; Muhammad, R.; Yusoff, N.M. Food safety knowledge and personal hygiene practices amongst mobile food handlers in Shah Alam, Selangor. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 222, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations). Food for the Cities: Street Foods. 2013. Available online: Urlhttp://www.fao.org/fcit/food-processing/street-foods/en/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Aduah, M.; Adzitey, F.; Amoako, D.G.; Abia, A.L.K.; Ekli, R.; Teye, G.A.; Shariff, A.H.M.; Huda, N. Not All Street Food Is Bad: Low Prevalence of Antibiotic-Resistant Salmonella enterica in Ready-to-Eat (RTE) Meats in Ghana Is Associated with Good Vendors’ Knowledge of Meat Safety. Foods 2021, 10, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Hygiene of Foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2004, L139, 1–54. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32004R0852 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- WHO. Codex Alimentarius, 4th ed.; Food Hygiene. Basic Texts; World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van’t Riet, H.; den Hartog, A.P.; Mwangi, A.M.; Mwadime, R.K.; Foeken, D.W.; van Staveren, W.A. The role of street foods in the dietary pattern of two low-income groups in Nairobi. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Namugaya, B.S.; Muyanja, C. Contribution of street foods to the dietary needs of street food vendors in Kampala, Jinja and Masaka districts, Uganda. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steyn, N.P.; Labadarios, D.; Nel, J.H. Factors which influence the consumption of street foods and fast foods in South Africa—A national survey. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.N.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A.; Chang, R.C.Y. An application of the repertory grid method and generalized Procrustes analysis to investigate the motivational factors of tourist food consumption. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2013, 35, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, N.P.; Mchiza, Z.; Hill, J.; Davids, Y.D.; Venter, I.; Hinrichsen, E.; Opperman, M.; Rumboeow, J.; Jacobs, P. Nutritional contribution of street foods to the diet of people in developing countries: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 17, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khongtong, J.; Ab Karim, S.; Othman, M.; Bolong, J. Consumption pattern and consumers’ opinion toward street food in Nakhon Si Thammarat province, Thailand. Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sirigunnaa, J. Food safety in Thailand: A comparison between inbound senior and non-senior tourists. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 197, 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franklyn, S.; Badrie, N. Vendor Hygienic Practices and Consumer Perception of Food Safety during the Carnival festival on the island of Tobago, West Indies. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarria, L.C.T.; Phakdee-auksorn, P. Understanding international tourists’ attitudes towards street food in Phuket, Thailand. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsavuran, Z.; Özdemir, B. Understanding street food consumption: A theoretical model including atmosphere and hedonism. Proceedings Book II. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism Dynamics and Trends, Sevilla, Spain, 26–29 June 2017; pp. 541–553. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulmajid, N.; Bautista, M.K.; Bautista, S.; Chavez, E.; Dimaano, W.; Barcelon, E. Heavy metals assessment and sensory evaluation of street vended foods. Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 2127–2131. [Google Scholar]

- Wiatrowski, M.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Trafiałek, J. Consumer Eating Behavior and Opinions about the Food Safety of Street Food in Poland. Nutrients 2021, 13, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polska na Talerzu 2015. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2015. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/294746/co-gdzie-za-ile-jadamy-na-miescie-raport-polska-na-talerzu-2015 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Polska na Talerzu 2016. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2016. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/313540/jak-ksztaltuja-sie-preferencje-kulinarne-polakow-raport-polska-na-talerzu-2016 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Polska na Talerzu 2017. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2017. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/369536/pizzerie-food-trucki-czy-targi-sniadaniowe-najnowsze-trendy-w-raporcie (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Polska na Talerzu 2018. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2018. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/394477/jak-polacy-zamawiaja-jedzenie-w-jakich-mediach-spolecznosciowych-szuka (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Polska na Talerzu 2019. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2019. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/460369/tradycyjna-polska-kuchnia-wciaz-kroluje-na-naszych-talerzach-najnowsze (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Nonato, I.L.; Minussi, L.O.A.; Pascoal, G.B.; De-Souza, D.A. Nutritional issue concerning street foods. J. Clin. Nutr Diet. 2016, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trafialek, J.; Kołozyn-Krajewska, D. Implementation of Safety Assurance System in Food Production in Poland. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 61, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trafiałek, J.; Zwoliński, M.; Kolanowski, W. Assessing hygiene practices during fish selling in retail stores. BFJ 2016, 118, 2053–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muinde, O.K.; Kuria, E. Hygienic and sanitary practices of vendors of street foods in Nairobi, Kenya. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Develop. 2005, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gbigbi, T.M.; Okonkwo, G.E.; Chuks-Okonta, V.A. Identification of Food Safety Practices among Street Food Vendors in Delta State Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2021, VIII, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, B.M.; Volel, C.; Finkel, M. Safety of vendor- prepared foods: Evaluation of 10 Processing mobile food vendors in Manhattan. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Question | Areas of Food Production * | Compliance | Noncompliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| with Hygienic Rules (% of Outlets) | ||||

| Section 1 | 1.1 | Hygiene of production area | 73.2 | 26.8 |

| 1.2 | Functionality of production process | 70.3 | 29.7 | |

| 1.3 | Condition and cleanliness of waste bin | 71.9 | 28.1 | |

| 1.4 | Condition and cleanliness of floor | 66.5 | 33.5 | |

| 1.5 | Condition and cleanliness of production tops | 71.2 | 28.8 | |

| 1.6 | Condition and cleanliness of facility walls | 63.6 | 36.4 | |

| 1.7 | System of air ventilation | 62.1 | 37.9 | |

| 1.8 | Food pests in the production area | 76.7 | 23.3 | |

| 1.9 | GHP ** at the facility | 60.7 | 39.3 | |

| 1.10 | Possibility to clean/disinfect the equipment | 65.9 | 34.1 | |

| 1.11 | Personal items in the production area | 50.6 | 49.4 | |

| Average level of compliance in Section 1 | 66.6 | 33.4 | ||

| Section 2 | 2.1 | Condition of working places | 67.6 | 32.4 |

| 2.2 | Separation of food from the consumer | 71.4 | 28.6 | |

| 2.3 | Correctly using and storing the packaging and tableware | 64.1 | 35.9 | |

| 2.4 | Proper raw material storage | 73.6 | 26.4 | |

| 2.5 | Separation of raw material and final products | 54.1 | 45.9 | |

| 2.6 | Separation of ready-to-eat products and waste | 66.3 | 33.7 | |

| 2.7 | Use of separate equipment during meal preparation and distribution | 61.2 | 38.8 | |

| 2.8 | Condition and cleanliness of catering equipment | 69.8 | 30.2 | |

| 2.9 | Proper handling of tableware | 62.8 | 37.2 | |

| 2.10 | Unauthorized people in the production areas | 60.1 | 39.9 | |

| 2.11 | Quality of semi-finished and ready-to-eat products | 72.7 | 27.3 | |

| 2.12 | Possibility for cross contamination activities | 60.5 | 39.5 | |

| 2.13 | Hygienically handling packaging and tableware | 63.6 | 36.4 | |

| Average level of compliance in Section 2 | 65.2 | 34.8 | ||

| Question | Aspects of Personal Hygiene of Staff * | Compliances | Non Compliances |

|---|---|---|---|

| with Hygienic Rules (% of Outlets) | |||

| 3 | Section 3 | ||

| 3.1 | Cleanliness of employee’s hands | 72.9 | 27.1 |

| 3.2 | Cleanliness of employee’s nails | 64.5 | 35.5 |

| 3.3 | Hand jewelry wearing by workers | 59.2 | 40.8 |

| 3.4 | Correct protection from hand injuries | 68.1 | 31.9 |

| 3.5 | Compliance with no-drinking and no-eating rules in the production area | 55.9 | 44.1 |

| 3.6 | Correct working attire of employees | 62.5 | 37.5 |

| 3.7 | Workers’ personal attire covering | 44.8 | 55.2 |

| 3.8 | Correct hand-washing by workers | 50.1 | 49.9 |

| 3.9 | Correct hand-drying after washing by workers | 46.6 | 53.4 |

| 3.10 | Sink for washing hands with instructions in the production area | 57.9 | 42.1 |

| 3.11 | Proper accessories to wash hands in facilities | 57.7 | 42.3 |

| 3.12 | Separation of handling money from handling food | 57.6 | 42.4 |

| 3.13 | Proper use of disposable gloves by workers | 57.7 | 42.3 |

| 3.14 | Cleanliness of staff hair | 69.0 | 31.0 |

| 3.15 | Correct hair covering of workers during food handling | 50.1 | 49.9 |

| 3.16 | Long hair protection by workers | 55.4 | 44.6 |

| 3.17 | Private clothing items used by workers | 56.3 | 43.7 |

| 3.18 | Presence of earrings or other facial accessories on staff during work | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| 3.19 | Head or skin problems of workers | 71.2 | 28.8 |

| 3.20 | Illness of workers | 66.7 | 33.3 |

| 3.21 | Excessive make-up on workers | 61.0 | 39.0 |

| 3.22 | Touching face, hair, nose, or ears during food production by workers | 60.7 | 39.3 |

| Average level of compliance in Section 3 | 59.3 | 40.7 | |

| Assessed Area | Type of Outlet | Maximum Points | Grade (Points) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average ± SD | Median | ||||

| Sanitary conditions of food production | All outlets Food trucks Stands | 11 | 7.3 ± 2.2 7.5 ± 2.1 7.0 ± 2.3 | 8 8 7 | 0.0419 * |

| Hygiene of processes of food production and distribution | All outlets Food trucks Stands | 13 | 8.5 ± 2.2 8.6 ± 2.1 8.3 ± 2.4 | 9 9 9 | 0.1225 * |

| Personal hygiene of staff | All outlets Food trucks Stands | 22 | 12.4 ± 2.9 12.5 ± 2.8 12.3 ± 3.3 | 13 12 13 | 0.5779 * |

| Overall hygiene rating | All outlets Food trucks Stands | 46 | 28.2 ± 5.7 28.5 ± 5.1 27.6 ± 6.9 | 29 29 29 | 0.0049 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wiatrowski, M.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Trafiałek, J.; Rosiak, E. An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of Polish Street Food Vendors in Selected Food Trucks and Stands. Foods 2021, 10, 2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10112640

Wiatrowski M, Czarniecka-Skubina E, Trafiałek J, Rosiak E. An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of Polish Street Food Vendors in Selected Food Trucks and Stands. Foods. 2021; 10(11):2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10112640

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiatrowski, Michał, Ewa Czarniecka-Skubina, Joanna Trafiałek, and Elżbieta Rosiak. 2021. "An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of Polish Street Food Vendors in Selected Food Trucks and Stands" Foods 10, no. 11: 2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10112640

APA StyleWiatrowski, M., Czarniecka-Skubina, E., Trafiałek, J., & Rosiak, E. (2021). An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of Polish Street Food Vendors in Selected Food Trucks and Stands. Foods, 10(11), 2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10112640