Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

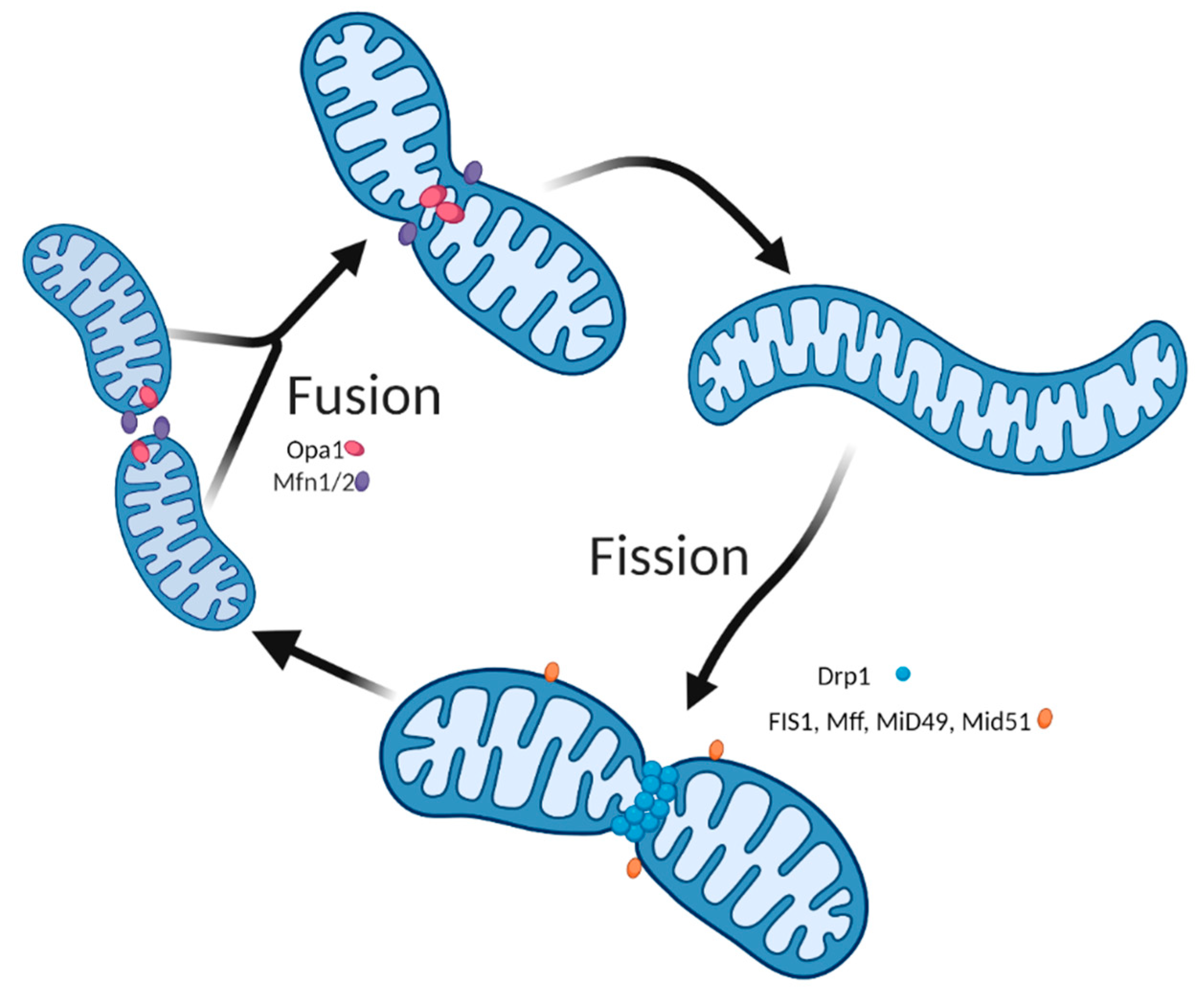

2. The Importance of Mitochondria Dynamics for Skeletal Muscle Health

3. Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Skeletal Muscle Aging Process: Current State of Knowledge and Considerations for Future Research

4. The Role of Autophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging

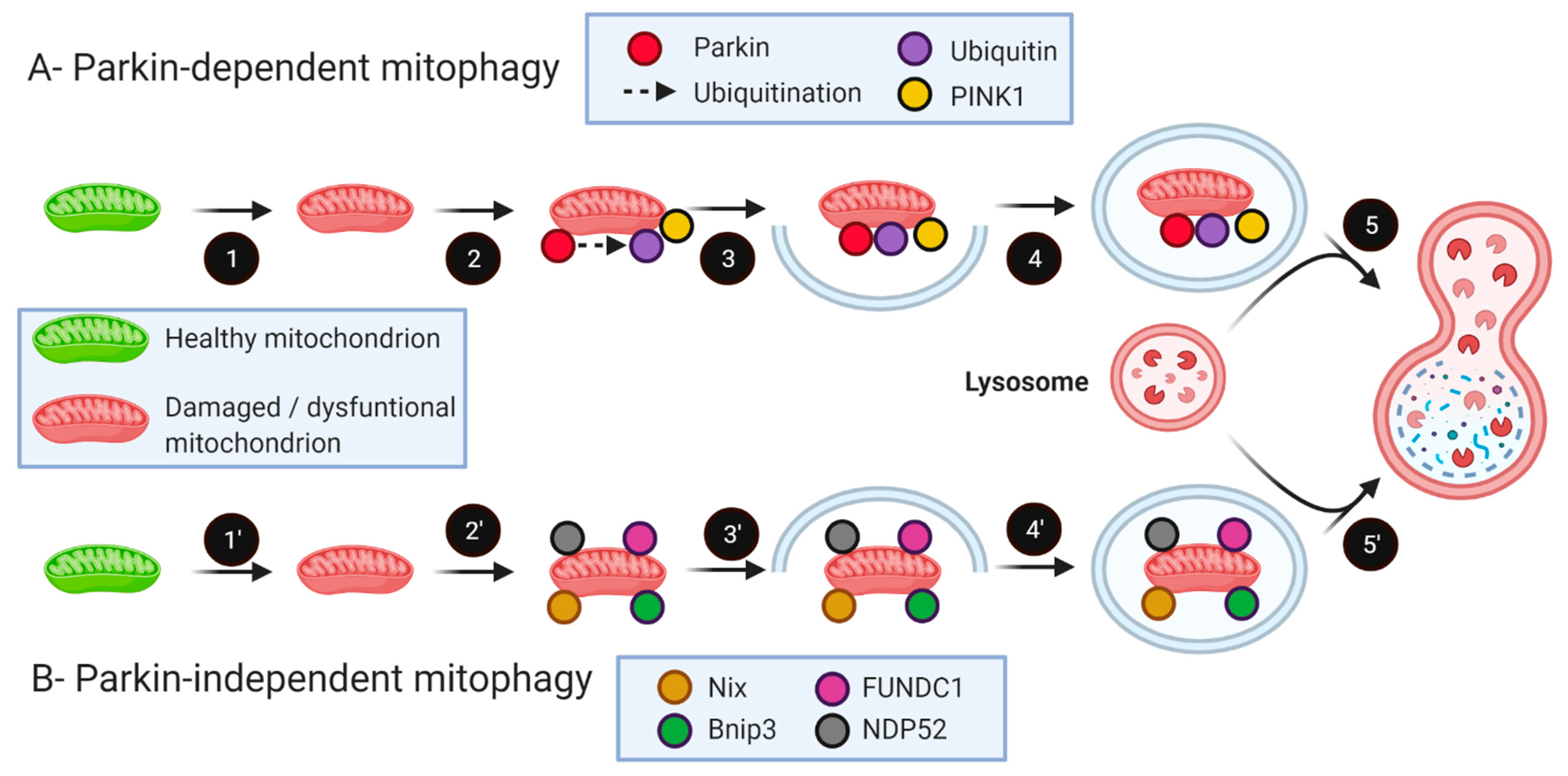

5. The Role of Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging

6. Enhancing Mitophagy to Counteract Sarcopenia: Potential Applicability and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sartori, R.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: Implications in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Chen, T.; Cai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Fan, L.; Wu, C. Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Oldest Old Is Associated with Disability and Poor Physical Function. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.; Cyrino, E.S.; Antunes, M.; Santos, D.A.; Sardinha, L.B. Sarcopenia and physical independence in older adults: The independent and synergic role of muscle mass and muscle function. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlen, B.M.; Mekkodathil, A.; Al-Thani, H.; El-Menyar, A. Impact of sarcopenia in trauma and surgical patient population: A literature review. Asian J. Surg. 2020, 43, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Tao, W.; Dou, Q.; Yang, Y. Sarcopenia as a predictor of hospitalization among older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrano, D.L.; Landi, F.; Volpato, S.; Corsonello, A.; Meloni, E.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Association of sarcopenia with short- and long-term mortality in older adults admitted to acute care wards: Results from the CRIME study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Morley, J.E.; von Haehling, S. Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 512–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, L.; Degens, H.; Li, M.; Salviati, L.; Lee, Y.I.; Thompson, W.; Kirkland, J.L.; Sandri, M. Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 427–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouspillou, G.; Sgarioto, N.; Kapchinsky, S.; Purves-Smith, F.; Norris, B.; Pion, C.H.; Barbat-Artigas, S.; Lemieux, F.; Taivassalo, T.; Morais, J.A.; et al. Increased sensitivity to mitochondrial permeability transition and myonuclear translocation of endonuclease G in atrophied muscle of physically active older humans. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouspillou, G.; Bourdel-Marchasson, I.; Rouland, R.; Calmettes, G.; Franconi, J.-M.; Deschodt-Arsac, V.; Diolez, P. Alteration of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in aged skeletal muscle involves modification of adenine nucleotide translocator. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2010, 1797, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trounce, I.; Byrne, E.; Marzuki, S. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory chain function: Possible factor in ageing. Lancet 1989, 1, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, A.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Apoptosis in skeletal muscle with aging. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002, 282, R519–R527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabi, B.; Ljubicic, V.; Menzies, K.J.; Huang, J.H.; Saleem, A.; Hood, D.A. Mitochondrial function and apoptotic susceptibility in aging skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, K.R.; Bigelow, M.L.; Kahl, J.; Singh, R.; Coenen-Schimke, J.; Raghavakaimal, S.; Nair, K.S. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5618–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Fang, H.; Groom, L.; Cheng, A.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Han, P.; Zheng, M.; et al. Superoxide flashes in single mitochondria. Cell 2008, 134, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, S.L.; Gagnon, B.J.; Senf, S.M.; Hain, B.A.; Judge, A.R. Ros-mediated activation of NF-kappaB and Foxo during muscle disuse. Muscle Nerve 2010, 41, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M.; Sandri, C.; Gilbert, A.; Skurk, C.; Calabria, E.; Picard, A.; Walsh, K.; Schiaffino, S.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 2004, 117, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Lezza, A.M.S.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Pesce, V.; Calvani, R.; Bossola, M.; Manes-Gravina, E.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. Circulating Mitochondrial DNA at the Crossroads of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Inflammation During Aging and Muscle Wasting Disorders. Rejuvenation Res. 2018, 21, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, W. Mitochondrial dysfunction/NLRP3 inflammasome axis contributes to angiotensin II-induced skeletal muscle wasting via PPAR-gamma. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 2020, 100, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Zhang, L.; Mitch, W.E.; LeDoux, J.M.; Hu, J.; Du, J. Caspase-3 cleaves specific 19 S proteasome subunits in skeletal muscle stimulating proteasome activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 21249–21257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggan, A.R.; Spina, R.J.; King, D.S.; Rogers, M.A.; Brown, M.; Nemeth, P.M.; Holloszy, J.O. Skeletal muscle adaptations to endurance training in 60- to 70-yr-old men and women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992, 72, 1780–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Kwak, H.B.; Lawler, J.M. Exercise training attenuates age-induced changes in apoptotic signaling in rat skeletal muscle. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean-Pelletier, F.; Pion, C.H.; Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Sgarioto, N.; Zovilé, I.; Barbat-Artigas, S.; Reynaud, O.; Alkaterji, F.; Lemieux, F.C.; Grenon, A. The impact of ageing, physical activity, and pre-frailty on skeletal muscle phenotype, mitochondrial content, and intramyocellular lipids in men. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Montoya, I.; Correa-Pérez, A.; Abraha, I.; Soiza, R.L.; Cherubini, A.; O’Mahony, D.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J. Nonpharmacological interventions to treat physical frailty and sarcopenia in older patients: A systematic overview—The SENATOR Project ONTOP Series. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.J.; Betik, A.C.; Krause, D.J.; Hepple, R.T. No decline in skeletal muscle oxidative capacity with aging in long-term calorically restricted rats: Effects are independent of mitochondrial DNA integrity. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayhew, M.; Renganathan, M.; Delbono, O. Effectiveness of caloric restriction in preventing age-related changes in rat skeletal muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 251, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepple, R.T.; Baker, D.J.; McConkey, M.; Murynka, T.; Norris, R. Caloric restriction protects mitochondrial function with aging in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Rejuvenation Res. 2006, 9, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouspillou, G.; Hepple, R.T. Facts and controversies in our understanding of how caloric restriction impacts the mitochondrion. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, T.; Yamasaki, Y. Ultra-High-resolution scanning electron microscopy of mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticulum arrangement in human red, white, and intermediate muscle fibers. Anat. Rec. 1997, 248, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C. Fusion and fission: Interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012, 46, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, D.F.; Norris, K.L.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilokani, L.; Nagashima, S.; Paupe, V.; Prudent, J. Mitochondrial dynamics: Overview of molecular mechanisms. Essays Biochem. 2018, 62, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Vermulst, M.; Wang, Y.E.; Chomyn, A.; Prolla, T.A.; McCaffery, J.M.; Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial fusion is required for mtDNA stability in skeletal muscle and tolerance of mtDNA mutations. Cell 2010, 141, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, D.; Sorianello, E.; Segales, J.; Irazoki, A.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Sala, D.; Planet, E.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Munoz, J.P.; Sanchez-Feutrie, M.; et al. Mfn2 deficiency links age-related sarcopenia and impaired autophagy to activation of an adaptive mitophagy pathway. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 1677–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, M.B.; Bush, Z.; McGinnis, G.R.; Rowe, G.C. Adult skeletal muscle deletion of Mitofusin 1 and 2 impedes exercise performance and training capacity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezze, C.; Romanello, V.; Desbats, M.A.; Fadini, G.P.; Albiero, M.; Favaro, G.; Ciciliot, S.; Soriano, M.E.; Morbidoni, V.; Cerqua, C.; et al. Age-Associated Loss of OPA1 in Muscle Impacts Muscle Mass, Metabolic Homeostasis, Systemic Inflammation, and Epithelial Senescence. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1374–1389.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.O.; Tadinada, S.M.; Zasadny, F.M.; Oliveira, K.J.; Pires, K.M.P.; Olvera, A.; Jeffers, J.; Souvenir, R.; Mcglauflin, R.; Seei, A.; et al. OPA1 deficiency promotes secretion of FGF21 from muscle that prevents obesity and insulin resistance. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2126–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nuevo, A.; Díaz-Ramos, A.; Noguera, E.; Díaz-Sáez, F.; Duran, X.; Muñoz, J.P.; Romero, M.; Plana, N.; Sebastián, D.; Tezze, C.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA and TLR9 drive muscle inflammation upon Opa1 deficiency. EMBO J. 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvier, T.; De Palma, C.; Rigamonti, E.; Scagliola, A.; Incerti, E.; Mazelin, L.; Thomas, J.L.; D’Antonio, M.; Politi, L.; Schaeffer, L.; et al. Muscle-specific Drp1 overexpression impairs skeletal muscle growth via translational attenuation. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovarelli, M.; Zecchini, S.; Martini, E.; Garrè, M.; Barozzi, S.; Ripolone, M.; Napoli, L.; Coazzoli, M.; Vantaggiato, C.; Roux-Biejat, P.; et al. Drp1 overexpression induces desmin disassembling and drives kinesin-1 activation promoting mitochondrial trafficking in skeletal muscle. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 2383–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello, V.; Guadagnin, E.; Gomes, L.; Roder, I.; Sandri, C.; Petersen, Y.; Milan, G.; Masiero, E.; Del Piccolo, P.; Foretz, M.; et al. Mitochondrial fission and remodelling contributes to muscle atrophy. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, G.; Romanello, V.; Varanita, T.; Andrea Desbats, M.; Morbidoni, V.; Tezze, C.; Albiero, M.; Canato, M.; Gherardi, G.; De Stefani, D.; et al. DRP1-mediated mitochondrial shape controls calcium homeostasis and muscle mass. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulac, M.; Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Reynaud, O.; Ayoub, M.B.; Guerin, A.; Finkelchtein, M.; Hussain, S.N.; Gouspillou, G. Drp1 knockdown induces severe muscle atrophy and remodelling, mitochondrial dysfunction, autophagy impairment and denervation. J. Physiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avellaneda, J.; Rodier, C.; Daian, F.; Brouilly, N.; Rival, T.; Luis, N.M.; Schnorrer, F. Myofibril and mitochondria morphogenesis are coordinated by a mechanical feedback mechanism in muscle. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.T.; Chen, P.L.; Su, M.P.; Li, J.C.; Chang, Y.W.; Liu, R.W.; Juan, H.F.; Yang, J.M.; Chan, S.P.; Tsai, Y.C.; et al. Loss of Fis1 impairs proteostasis during skeletal muscle aging in Drosophila. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.M.; Adhihetty, P.J.; Wawrzyniak, N.R.; Wohlgemuth, S.E.; Picca, A.; Kujoth, G.C.; Prolla, T.A.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Dysregulation of mitochondrial quality control processes contribute to sarcopenia in a mouse model of premature aging. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M.F.; Vainshtein, A.; Iqbal, S.; Ostojic, O.; Hood, D.A. Adaptive plasticity of autophagic proteins to denervation in aging skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C422–C430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, K.; Ohlendieck, K. Proteomic DIGE analysis of the mitochondria-enriched fraction from aged rat skeletal muscle. Proteomics 2009, 9, 5509–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Ostojic, O.; Singh, K.; Joseph, A.M.; Hood, D.A. Expression of mitochondrial fission and fusion regulatory proteins in skeletal muscle during chronic use and disuse. Muscle Nerve 2013, 48, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faitg, J.; Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Reynaud, O.; Ferland, G.; Gaudreau, P.; Gouspillou, G. Effects of Aging and Caloric Restriction on Fiber Type Composition, Mitochondrial Morphology and Dynamics in Rat Oxidative and Glycolytic Muscles. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltai, E.; Hart, N.; Taylor, A.W.; Goto, S.; Ngo, J.K.; Davies, K.J.; Radak, Z. Age-Associated declines in mitochondrial biogenesis and protein quality control factors are minimized by exercise training. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2012, 303, R127–R134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Picard, M.; St-Jean Pelletier, F.; Sgarioto, N.; Auger, M.J.; Vallee, J.; Robitaille, R.; St-Pierre, D.H.; Gouspillou, G. Mitochondrial morphology is altered in atrophied skeletal muscle of aged mice. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 17923–17937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, D.; Vasso, M.; De Palma, S.; Fania, C.; Torretta, E.; Cammarata, F.P.; Magnaghi, V.; Procacci, P.; Gelfi, C. Specific protein changes contribute to the differential muscle mass loss during ageing. Proteomics 2016, 16, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, D.; Kang, C.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Vina, J.; Ji, L.L. Intensified mitophagy in skeletal muscle with aging is downregulated by PGC-1alpha overexpression in vivo. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 130, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zou, X.; Feng, Z.; Luo, C.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Chang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Long, J.; et al. Evidence for association of mitochondrial metabolism alteration with lipid accumulation in aging rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 56, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopka, A.R.; Suer, M.K.; Wolff, C.A.; Harber, M.P. Markers of Human Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Quality Control: Effects of Age and Aerobic Exercise Training. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2013, 69, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, E.; Schwalm, C.; Naslain, D.; Nielens, H.; Francaux, M.; Deldicque, L. Regular Endurance Exercise Promotes Fission, Mitophagy, and Oxidative Phosphorylation in Human Skeletal Muscle Independently of Age. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distefano, G.; Standley, R.A.; Dubé, J.J.; Carnero, E.A.; Ritov, V.B.; Stefanovic-Racic, M.; Toledo, F.G.; Piva, S.R.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Coen, P.M. Chronological Age Does not Influence Ex-vivo Mitochondrial Respiration and Quality Control in Skeletal Muscle. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.M.; Adhihetty, P.J.; Buford, T.W.; Wohlgemuth, S.E.; Lees, H.A.; Nguyen, L.M.; Aranda, J.M.; Sandesara, B.D.; Pahor, M.; Manini, T.M.; et al. The impact of aging on mitochondrial function and biogenesis pathways in skeletal muscle of sedentary high- and low-functioning elderly individuals. Aging Cell 2012, 11, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.D.; Devries, M.C.; Safdar, A.; Hamadeh, M.J.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. The effect of aging on human skeletal muscle mitochondrial and intramyocellular lipid ultrastructure. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2010, 65, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckelsma, V.L.; Levinger, I.; McKenna, M.J.; Formosa, L.E.; Ryan, M.T.; Petersen, A.C.; Anderson, M.J.; Murphy, R.M. Preservation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial content in older adults: Relationship between mitochondria, fibre type and high-intensity exercise training. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3345–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.H.; McCaffery, J.M.; Chan, D.C. Mouse lines with photo-activatable mitochondria to study mitochondrial dynamics. Genesis 2012, 50, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, C.G.; Lally, J.; Holloway, G.P.; Heigenhauser, G.J.; Bonen, A.; Spriet, L.L. Repeated transient mRNA bursts precede increases in transcriptional and mitochondrial proteins during training in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 4795–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, C.; Oliveira, R.S.F.; Little, J.P.; Renner, K.; Bishop, D.J. Training intensity modulates changes in PGC-1α and p53 protein content and mitochondrial respiration, but not markers of mitochondrial content in human skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinild Lundby, A.K.; Jacobs, R.A.; Gehrig, S.; de Leur, J.; Hauser, M.; Bonne, T.C.; Flück, D.; Dandanell, S.; Kirk, N.; Kaech, A.; et al. Exercise training increases skeletal muscle mitochondrial volume density by enlargement of existing mitochondria and not de novo biogenesis. Acta Physiol. 2018, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Varuzhanyan, G.; Pham, A.H.; Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial Dynamics Is a Distinguishing Feature of Skeletal Muscle Fiber Types and Regulates Organellar Compartmentalization. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, R.; Larsen, S.; Dohlmann, T.L.; Qvortrup, K.; Helge, J.W.; Dela, F.; Prats, C. Three-Dimensional reconstruction of the human skeletal muscle mitochondrial network as a tool to assess mitochondrial content and structural organization. Acta Physiol. 2015, 213, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, J.S.V.; Herbst, E.A.F.; Matravadia, S.; Maher, A.C.; Perry, C.G.R.; Ventura-Clapier, R.; Holloway, G.P. Over-Expressing Mitofusin-2 in Healthy Mature Mammalian Skeletal Muscle Does Not Alter Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Oliveira, M.P.; Khamoui, A.V.; Aparicio, R.; Rera, M.; Rossiter, H.B.; Walker, D.W. Promoting Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in midlife prolongs healthy lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twig, G.; Elorza, A.; Molina, A.J.; Mohamed, H.; Wikstrom, J.D.; Walzer, G.; Stiles, L.; Haigh, S.E.; Katz, S.; Las, G.; et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulac, M.; Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Cefis, M.; Ayoub, M.B.; Reynaud, O.; Shams, A.; Moamer, A.; Nery Ferreira, M.F.; Hussain, S.N.; Gouspillou, G. Regulation of muscle and mitochondrial health by the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 in aged mice. J. Physiol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Mizushima, N.; Virgin, H.W. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 2011, 469, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorimitsu, T.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy: Molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12 (Suppl. 2), 1542–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.D.; White, E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science 2010, 330, 1344–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008, 132, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. Eaten alive: A history of macroautophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukada, M.; Ohsumi, Y. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993, 333, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.R.; Chan, E.Y.; Hu, X.W.; Kochl, R.; Crawshaw, S.G.; High, S.; Hailey, D.W.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Tooze, S.A. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 3888–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Carson, A.R.; Caniggia, I.; Umebayashi, K.; Yoshimori, T.; Nakabayashi, K.; Scherer, S.W. Endothelial nitric-oxide synthase antisense (NOS3AS) gene encodes an autophagy-related protein (APG9-like2) highly expressed in trophoblast. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18283–18290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsi, A.; Razi, M.; Dooley, H.C.; Robinson, D.; Weston, A.E.; Collinson, L.M.; Tooze, S.A. Dynamic and transient interactions of Atg9 with autophagosomes, but not membrane integration, are required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, N.; Noda, T.; Yoshimori, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishii, T.; George, M.D.; Klionsky, D.J.; Ohsumi, M.; Ohsumi, Y. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature 1998, 395, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Sugita, H.; Yoshimori, T.; Ohsumi, Y. A new protein conjugation system in human. The counterpart of the yeast Apg12p conjugation system essential for autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 33889–33892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Noda, T.; Ohsumi, Y. Apg16p is required for the function of the Apg12p-Apg5p conjugate in the yeast autophagy pathway. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 3888–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Kuma, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Matsubae, M.; Takao, T.; Natsume, T.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12-Apg5 conjugate. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, I.; Mizushima, N.; Kiyooka, M.; Ohsumi, M.; Ueno, T.; Ohsumi, Y.; Kominami, E. Apg7p/Cvt2p: A novel protein-activating enzyme essential for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, T.; Mizushima, N.; Ogawa, Y.; Matsuura, A.; Noda, T.; Ohsumi, Y. Apg10p, a novel protein-conjugating enzyme essential for autophagy in yeast. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 5234–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuma, A.; Mizushima, N.; Ishihara, N.; Ohsumi, Y. Formation of the approximately 350-kDa Apg12-Apg5.Apg16 multimeric complex, mediated by Apg16 oligomerization, is essential for autophagy in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 18619–18625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeya, Y.; Mizushima, N.; Ueno, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Kirisako, T.; Noda, T.; Kominami, E.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5720–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeya, Y.; Mizushima, N.; Yamamoto, A.; Oshitani-Okamoto, S.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form-II formation. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 2805–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, H.C.; Razi, M.; Polson, H.E.; Girardin, S.E.; Wilson, M.I.; Tooze, S.A. WIPI2 links LC3 conjugation with PI3P, autophagosome formation, and pathogen clearance by recruiting Atg12-5-16L1. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abdel-Aziz, A.K.; Abdelfatah, S.; Abdellatif, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abel, S.; Abeliovich, H.; Abildgaard, M.H.; Abudu, Y.P.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition). Autophagy 2021, 1–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofarrahi, M.; Guo, Y.; Haspel, J.A.; Choi, A.M.; Davis, E.C.; Gouspillou, G.; Hepple, R.T.; Godin, R.; Burelle, Y.; Hussain, S.N. Autophagic flux and oxidative capacity of skeletal muscles during acute starvation. Autophagy 2013, 9, 1604–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, J.-S.; Varadhachary, A.S.; Miller, S.E.; Weihl, C.C. Quantitation of “autophagic flux” in mature skeletal muscle. Autophagy 2010, 6, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanello, V.; Scalabrin, M.; Albiero, M.; Blaauw, B.; Scorrano, L.; Sandri, M. Inhibition of the Fission Machinery Mitigates OPA1 Impairment in Adult Skeletal Muscles. Cells 2019, 8, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.D.; Yan, X.L.; Fan, S.D.; Chen, X.Y.; Yan, J.Y.; Dong, Q.T.; Chen, W.Z.; Liu, N.X.; Chen, X.L.; Yu, Z. Nrf2 deficiency promotes the increasing trend of autophagy during aging in skeletal muscle: A potential mechanism for the development of sarcopenia. Aging 2020, 12, 5977–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oost, L.J.; Kustermann, M.; Armani, A.; Blaauw, B.; Romanello, V. Fibroblast growth factor 21 controls mitophagy and muscle mass. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, C.; Morisi, F.; Cheli, S.; Pambianco, S.; Cappello, V.; Vezzoli, M.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Moggio, M.; Ripolone, M.; Francolini, M.; et al. Autophagy as a new therapeutic target in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N. Methods for monitoring autophagy using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 452, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulis, M.; Vindis, C. Methods for Measuring Autophagy in Mice. Cells 2017, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, W.; Roth, L.; De Meyer, G.R.Y. Standard Immunohistochemical Assays to Assess Autophagy in Mammalian Tissue. Cells 2017, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schworer, C.M.; Mortimore, G.E. Glucagon-induced autophagy and proteolysis in rat liver: Mediation by selective deprivation of intracellular amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 3169–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnio, S.; LoVerso, F.; Baraibar, M.A.; Longa, E.; Khan, M.M.; Maffei, M.; Reischl, M.; Canepari, M.; Loefler, S.; Kern, H.; et al. Autophagy impairment in muscle induces neuromuscular junction degeneration and precocious aging. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.F.; Sebti, S.; Wei, Y.; Zou, Z.; Shi, M.; McMillan, K.L.; He, C.; Ting, T.; Liu, Y.; Chiang, W.C.; et al. Disruption of the beclin 1-BCL2 autophagy regulatory complex promotes longevity in mice. Nature 2018, 558, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, F.; Zimmermann, A.; Maiuri, M.C.; Kroemer, G. Essential role for autophagy in life span extension. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez, A.; Talloczy, Z.; Seaman, M.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Hall, D.H.; Levine, B. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science 2003, 301, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masiero, E.; Agatea, L.; Mammucari, C.; Blaauw, B.; Loro, E.; Komatsu, M.; Metzger, D.; Reggiani, C.; Schiaffino, S.; Sandri, M. Autophagy is required to maintain muscle mass. Cell Metab. 2009, 10, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.A.; Zare, H.; Puertollano, R.; Raben, N. Atg5(flox)-Derived Autophagy-Deficient Model of Pompe Disease: Does It Tell the Whole Story? Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2017, 7, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.J.; Quijano, C.; Chen, E.; Liu, H.; Cao, L.; Fergusson, M.M.; Rovira, I., II; Gutkind, S.; Daniels, M.P.; Komatsu, M.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress mediate the physiological impairment induced by the disruption of autophagy. Aging 2009, 1, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.J.; Guissart, C.; Olahova, M.; Sasorith, S.; Piron-Prunier, F.; Suomi, F.; Zhang, D.; Martinez-Lopez, N.; Leboucq, N.; Bahr, A.; et al. Developmental Consequences of Defective ATG7-Mediated Autophagy in Humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2406–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Ito, Y.; Aizawa, M.; Aoi, W.; Yamaguchi, A. p62/SQSTM1 but not LC3 is accumulated in sarcopenic muscle of mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hütter, E.; Skovbro, M.; Lener, B.; Prats, C.; Rabøl, R.; Dela, F.; Jansen-Dürr, P. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment can be separated from lipofuscin accumulation in aged human skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, V.; Rolland, E.; Thornell, L.-E.; Mouly, V.; Butler-Browne, G. Distribution of satellite cells in the human vastus lateralis muscle during aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2002, 37, 1513–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, M.L.; Sigmond, T.; Borsos, E.; Barna, J.; Erdelyi, P.; Takacs-Vellai, K.; Orosz, L.; Kovacs, A.L.; Csikos, G.; Sass, M.; et al. Longevity pathways converge on autophagy genes to regulate life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Autophagy 2008, 4, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio, R.; Rana, A.; Walker, D.W. Upregulation of the Autophagy Adaptor p62/SQSTM1 Prolongs Health and Lifespan in Middle-Aged Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1029–1040.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demontis, F.; Perrimon, N. FOXO/4E-BP signaling in Drosophila muscles regulates organism-wide proteostasis during aging. Cell 2010, 143, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammucari, C.; Milan, G.; Romanello, V.; Masiero, E.; Rudolf, R.; Del Piccolo, P.; Burden, S.J.; Di Lisi, R.; Sandri, C.; Zhao, J.; et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Brault, J.J.; Schild, A.; Cao, P.; Sandri, M.; Schiaffino, S.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, G.; Romanello, V.; Pescatore, F.; Armani, A.; Paik, J.-H.; Frasson, L.; Seydel, A.; Zhao, J.; Abraham, R.; Goldberg, A.L.; et al. Regulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin–proteasome system by the FoxO transcriptional network during muscle atrophy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, J.O.; Yoo, S.M.; Ahn, H.H.; Nah, J.; Hong, S.H.; Kam, T.I.; Jung, S.; Jung, Y.K. Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Prat, L.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Perdiguero, E.; Ortet, L.; Rodriguez-Ubreva, J.; Rebollo, E.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Gutarra, S.; Ballestar, E.; Serrano, A.L.; et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature 2016, 529, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, D.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Youle, R.J. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 183, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, D.P.; Jin, S.M.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Gautier, C.A.; Shen, J.; Cookson, M.R.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, L.A.; Lazarou, M.; Fogel, A.I.; Li, Y.; Yamano, K.; Sarraf, S.A.; Banerjee, S.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 205, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Bauza, C.; Zhou, C.; Huang, Y.; Cui, M.; de Vries, R.L.; Kim, J.; May, J.; Tocilescu, M.A.; Liu, W.; Ko, H.S.; et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, N.; Sato, S.; Shiba, K.; Okatsu, K.; Saisho, K.; Gautier, C.A.; Sou, Y.-S.; Saiki, S.; Kawajiri, S.; Sato, F. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glauser, L.; Sonnay, S.; Stafa, K.; Moore, D.J. Parkin promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of the mitochondrial fusion factor mitofusin 1. J. Neurochem. 2011, 118, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, A.C.; Thomas, R.E.; Yu, S.; Vincow, E.S.; Pallanck, L. The mitochondrial fusion-promoting factor mitofusin is a substrate of the PINK1/parkin pathway. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziviani, E.; Tao, R.N.; Whitworth, A.J. Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5018–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Dorn, G.W., II. PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science 2013, 340, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, S.; Holmström, K.M.; Skujat, D.; Fiesel, F.C.; Rothfuss, O.C.; Kahle, P.J.; Springer, W. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sawada, T.; Lee, S.; Yu, W.; Silverio, G.; Alapatt, P.; Millan, I.; Shen, A.; Saxton, W.; Kanao, T.; et al. Parkinson’s disease-associated kinase PINK1 regulates Miro protein level and axonal transport of mitochondria. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deas, E.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Gandhi, S.; Desmond, H.; Kjaer, S.; Loh, S.H.; Renton, A.E.; Harvey, R.J.; Whitworth, A.J.; Martins, L.M. PINK1 cleavage at position A103 by the mitochondrial protease PARL. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, A.W.; Grenier, K.; Aguileta, M.A.; Muise, S.; Farazifard, R.; Haque, M.E.; McBride, H.M.; Park, D.S.; Fon, E.A. Mitochondrial processing peptidase regulates PINK1 processing, import and Parkin recruitment. EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.M.; Lazarou, M.; Wang, C.; Kane, L.A.; Narendra, D.P.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubli, D.A.; Cortez, M.Q.; Moyzis, A.G.; Najor, R.H.; Lee, Y.; Gustafsson, A.B. PINK1 Is Dispensable for Mitochondrial Recruitment of Parkin and Activation of Mitophagy in Cardiac Myocytes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ney, P.A. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellot, G.; Garcia-Medina, R.; Gounon, P.; Chiche, J.; Roux, D.; Pouysségur, J.; Mazure, N.M. Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy Is Mediated through Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via Their BH3 Domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 2570–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.A.; Quinsay, M.N.; Orogo, A.M.; Giang, K.; Rikka, S.; Gustafsson, A.B. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interacts with Bnip3 protein to selectively remove endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria via autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 19094–19104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikka, S.; Quinsay, M.N.; Thomas, R.L.; Kubli, D.A.; Zhang, X.; Murphy, A.N.; Gustafsson, A.B. Bnip3 impairs mitochondrial bioenergetics and stimulates mitochondrial turnover. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, I.; Kirkin, V.; McEwan, D.G.; Zhang, J.; Wild, P.; Rozenknop, A.; Rogov, V.; Lohr, F.; Popovic, D.; Occhipinti, A.; et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.C.; Holzbaur, E.L. Optineurin is an autophagy receptor for damaged mitochondria in parkin-mediated mitophagy that is disrupted by an ALS-linked mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4439–E4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.M.; Ordureau, A.; Paulo, J.A.; Rinehart, J.; Harper, J.W. The PINK1-PARKIN Mitochondrial Ubiquitylation Pathway Drives a Program of OPTN/NDP52 Recruitment and TBK1 Activation to Promote Mitophagy. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, T.; Xu, Z.; Liu, L.; Guo, Q.; Wu, H.; Liang, X.; Zhou, D.; Xiao, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Mitophagy Directs Muscle-Adipose Crosstalk to Alleviate Dietary Obesity. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1357–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.T.; Ji, J.; Dagda, R.K.; Jiang, J.F.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Kapralov, A.A.; Tyurin, V.A.; Yanamala, N.; Shrivastava, I.H.; Mohammadyani, D.; et al. Cardiolipin externalization to the outer mitochondrial membrane acts as an elimination signal for mitophagy in neuronal cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goljanek-Whysall, K.; Soriano-Arroquia, A.; McCormick, R.; Chinda, C.; McDonagh, B. miR-181a regulates p62/SQSTM1, parkin, and protein DJ-1 promoting mitochondrial dynamics in skeletal muscle aging. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, H.N.; Kim, Y.; Erlich, A.T.; Zarrin-Khat, D.; Hood, D.A. Autophagy and mitophagy flux in young and aged skeletal muscle following chronic contractile activity. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 3567–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.W.; Erlich, A.T.; Crilly, M.J.; Hood, D.A. Parkin is required for exercise-induced mitophagy in muscle: Impact of aging. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 315, E404–E415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, C.A.; Ferry, A.L.; Gamboa, J.L.; Andrade, F.H.; Dupont-Versteegden, E.E. Age-Related changes of cell death pathways in rat extraocular muscle. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, M.; Brown, A.; Merrell, E.; DiSanto-Rose, M.; Rathmacher, J.A.; Reynolds, T.H.T. PKB signaling and atrogene expression in skeletal muscle of aged mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, M.J.; Addison, O.; Brunker, L.; Hopkins, P.N.; McClain, D.A.; LaStayo, P.C.; Marcus, R.L. Downregulation of E3 ubiquitin ligases and mitophagy-related genes in skeletal muscle of physically inactive, frail older women: A cross-sectional comparison. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russ, D.W.; Wills, A.M.; Boyd, I.M.; Krause, J. Weakness, SR function and stress in gastrocnemius muscles of aged male rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 50, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Reynaud, O.; Hussain, S.N.; Gouspillou, G. Parkin overexpression protects from ageing-related loss of muscle mass and strength. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 1975–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.W.; Erlich, A.T.; Hood, D.A. Role of Parkin and endurance training on mitochondrial turnover in skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle 2018, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouspillou, G.; Godin, R.; Piquereau, J.; Picard, M.; Mofarrahi, M.; Mathew, J.; Purves-Smith, F.M.; Sgarioto, N.; Hepple, R.T.; Burelle, Y.; et al. Protective role of Parkin in skeletal muscle contractile and mitochondrial function. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 2565–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peker, N.; Donipadi, V.; Sharma, M.; McFarlane, C.; Kambadur, R. Loss of Parkin impairs mitochondrial function and leads to muscle atrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2018, 315, C164–C185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Rera, M.; Walker, D.W. Parkin overexpression during aging reduces proteotoxicity, alters mitochondrial dynamics, and extends lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8638–8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C.; Whitworth, A.J.; Kuo, I.; Andrews, L.A.; Feany, M.B.; Pallanck, L.J. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4078–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesah, Y.; Pham, T.; Burgess, H.; Middlebrooks, B.; Verstreken, P.; Zhou, Y.; Harding, M.; Bellen, H.; Mardon, G. Drosophila parkin mutants have decreased mass and cell size and increased sensitivity to oxygen radical stress. Development 2004, 131, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc-Gaudet, J.P.; Mayaki, D.; Reynaud, O.; Broering, F.E.; Chaffer, T.J.; Hussain, S.N.A.; Gouspillou, G. Parkin Overexpression Attenuates Sepsis-Induced Muscle Wasting. Cells 2020, 9, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, D.; Mouchiroud, L.; Andreux, P.A.; Katsyuba, E.; Moullan, N.; Nicolet-Dit-Felix, A.A.; Williams, E.G.; Jha, P.; Lo Sasso, G.; Huzard, D.; et al. Urolithin A induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreux, P.A.; Blanco-Bose, W.; Ryu, D.; Burdet, F.; Ibberson, M.; Aebischer, P.; Auwerx, J.; Singh, A.; Rinsch, C. The mitophagy activator urolithin A is safe and induces a molecular signature of improved mitochondrial and cellular health in humans. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyle, M.C.; Ebert, S.M.; Cook, D.P.; Kunkel, S.D.; Fox, D.K.; Bongers, K.S.; Bullard, S.A.; Dierdorff, J.M.; Adams, C.M. Systems-based discovery of tomatidine as a natural small molecule inhibitor of skeletal muscle atrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 14913–14924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Waltz, T.B.; Kassahun, H.; Lu, Q.; Kerr, J.S.; Morevati, M.; Fivenson, E.M.; Wollman, B.N.; Marosi, K.; Wilson, M.A.; et al. Tomatidine enhances lifespan and healthspan in C. elegans through mitophagy induction via the SKN-1/Nrf2 pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mitrovsky, G.; Vasanthi, H.R.; Das, D.K. Antiaging properties of a grape-derived antioxidant are regulated by mitochondrial balance of fusion and fission leading to mitophagy triggered by a signaling network of Sirt1-Sirt3-Foxo3-PINK1-PARKIN. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 345105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba-Fukushima, K.; Inoshita, T.; Sano, O.; Iwata, H.; Ishikawa, K.-I.; Okano, H.; Akamatsu, W.; Imai, Y.; Hattori, N. A Cell-Based High-Throughput Screening Identified Two Compounds that Enhance PINK1-Parkin Signaling. iScience 2020, 23, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartee, G.D.; Hepple, R.T.; Bamman, M.M.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise Promotes Healthy Aging of Skeletal Muscle. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laker, R.C.; Drake, J.C.; Wilson, R.J.; Lira, V.A.; Lewellen, B.M.; Ryall, K.A.; Fisher, C.C.; Zhang, M.; Saucerman, J.J.; Goodyear, L.J.; et al. Ampk phosphorylation of Ulk1 is required for targeting of mitochondria to lysosomes in exercise-induced mitophagy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, N.; Gunnarsson, T.P.; Bangsbo, J.; Pilegaard, H. Exercise and exercise training-induced increase in autophagy markers in human skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabani, S.; Bagherniya, M.; Askari, G.; Read, M.I.; Sahebkar, A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on mitophagy induction: A literature review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Panda, S. Fasting, Circadian Rhythms, and Time-Restricted Feeding in Healthy Lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P.; Longo, V.D.; Harvie, M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinsley, G.M.; Paoli, A. Time-Restricted eating and age-related muscle loss. Aging 2019, 11, 8741–8742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.A.; Aguirre, N.W.; Marcotte, G.R.; Marshall, A.G.; Baehr, L.M.; Hughes, D.C.; Hamilton, K.L.; Roberts, M.N.; Lopez-Dominguez, J.A.; Miller, B.F.; et al. The ketogenic diet preserves skeletal muscle with aging in mice. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Hagopian, K.; Lopez-Dominguez, J.A.; Kim, K.; Jasoliya, M.; Roberts, M.N.; Cortopassi, G.A.; Showalter, M.R.; Roberts, B.S.; Gonzalez-Reyes, J.A.; et al. A ketogenic diet impacts markers of mitochondrial mass in a tissue specific manner in aged mice. Aging 2021, 13, 7914–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai, P.N.; Seidlmayer, L.K.; Miller, C.; Ferrero, M.; Dorn, G.W., II; Schaefer, S.; Bers, D.M.; Dedkova, E.N. Mitochondrial Quality Control in Aging and Heart Failure: Influence of Ketone Bodies and Mitofusin-Stabilizing Peptides. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.A.; Walton, C.M.; Carr, S.T.; Andrus, J.L.; Cheung, E.C.K.; Duplisea, M.J.; Wilson, E.K.; Draney, C.; Lathen, D.R.; Kenner, K.B.; et al. beta-Hydroxybutyrate Elicits Favorable Mitochondrial Changes in Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Mota, A.; Vansant, H.; Evans, R.D.; Clarke, K. Safety and tolerability of sustained exogenous ketosis using ketone monoester drinks for 28 days in healthy adults. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. RTP 2019, 109, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Sex | Tissue | Model | Main Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Male & female (combined) | QUAD | Youths/Middle-aged 3–6 vs. 8–15 months old | Mfn1 & Mfn2: ↑ Opa1 & Drp1: NS Fis1: ↓ | [46] |

| Rats (Fischer 344 Brown Norway) | Male | EDL | Youths/Aged 5 vs. 35 months old | Mfn2, Fis1 & Opa1: ↑ Drp1: NS | [47] |

| Rats (Wistar) | Not specified | GAS | Youths/Aged 3 vs. 26 months old | Fis1: ↑ | [48] |

| Rats (Fischer 344 Brown Norway) | Male | TA | Youths/Aged 5 vs. 35 months old | Fis1 & Drp1;:↑ Mfn2: ↓ Opa1: NS | [49] |

| Rats (Sprague–Dawley) | Male | GAS & SOL | Youths/Aged 9 vs. 22 months old | Drp1 (SOL & GAS):↑ Mfn2 & Fis1 (GAS): ↑ | [50] |

| Rats (Wistar) | Male | GAS | Youths/Aged 3 vs. 26 months old | Fis1 & Mfn1: ↑ | [51] |

| Mice | Male | GAS | Youths/Aged 2–3 vs. 22–24 months old | Mfn2/Drp1 ratio:↑ Opa1, Drp1, Mfn1 & Mfn2: NS | [52] |

| Rats (Sprague-Dawley) | Male | GAS & TRI | Youths/Aged 3 vs. 22 months old | Opa1 & Mfn1 (GAS & TRI): ↑ Fis1 (GAS): ↓ Fis1 (TRI): ↑ | [53] |

| Mice | Not specified | TA | Youths/Aged 6 vs. 18 months old | OPA1: ↓ | [36] |

| Mice | Not specified | GAS | Youths/Aged 6 vs. 22 months old | Mfn1, Mfn2, Opa1 & Fis1: ↓ Drp1: NS | [34] |

| Mice (C57BL/6J) | Female | TA | Youths/Aged 2 vs. 24 months old | Fis1 & Mfn2: ↑ Drp1 & Opa1: NS | [54] |

| Rats (Sprague-Dawley) | Male | Muscles | Youths/Aged 5 vs. 25 months old | Drp1: ↑ Opa1: NS Mfn2 & Fis1: ↓ | [55] |

| Humans | Male | VL | Younger men (20 ± 1 y) vs. older men (74 ± 3 y) | Mfn1, Mfn2 & Fis1: NS | [56] |

| Humans | Male | VL | Younger men (22 ± 1 y) vs. older men (67 ± 2 y) | Opa1, Mfn2, Fis1: NS | [57] |

| Humans | Male & female (combined) | VL | Younger (24 ± 3 y) vs. older adults (78 ± 5 y) | Opa1, Mfn2, Fis1 & Drp1: NS | [58] |

| Humans | Male & female (combined) | VL | Younger (23 ± 1 y) vs. older adults (75 ± 1 y) | Mfn2, Fis1, Drp1: NS Opa1: ↓ | [59] |

| Humans | Male & female (combined) | VL | Younger (≈23 y) vs. older adults (≈70 y) | Mfn2: ↓ Drp1: trend for ↓ | [60] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leduc-Gaudet, J.-P.; Hussain, S.N.A.; Barreiro, E.; Gouspillou, G. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158179

Leduc-Gaudet J-P, Hussain SNA, Barreiro E, Gouspillou G. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(15):8179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158179

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeduc-Gaudet, Jean-Philippe, Sabah N. A. Hussain, Esther Barreiro, and Gilles Gouspillou. 2021. "Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 15: 8179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158179

APA StyleLeduc-Gaudet, J.-P., Hussain, S. N. A., Barreiro, E., & Gouspillou, G. (2021). Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(15), 8179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158179