Generalized M-Estimation-Based Framework for Robust Guidance Information Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Development of IMMCSRIF using generalized M-estimation.

- (2)

- Design of an Adaptive Weight Function optimizing L2- norm criterion performance under Gaussian noise.

- (3)

- Verify the theoretical prediction through simulation.

2. Problem Formulation

- (1)

- Strong nonlinearity: is non-differentiable (e.g., Equation (18)).

- (2)

- Non-Gaussian noise: causes biased covariance estimation.

- (3)

- Numerical instability: under model mismatch.

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Maximum Correlation Entropy Cost Function

- (1)

- Positive definiteness: the kernel matrix must be semi-positive definite.

- (2)

- Symmetry: .

- (3)

- Decaying Influence: decreases as the error increases, suppressing the effect of outliers.

3.2. DCS

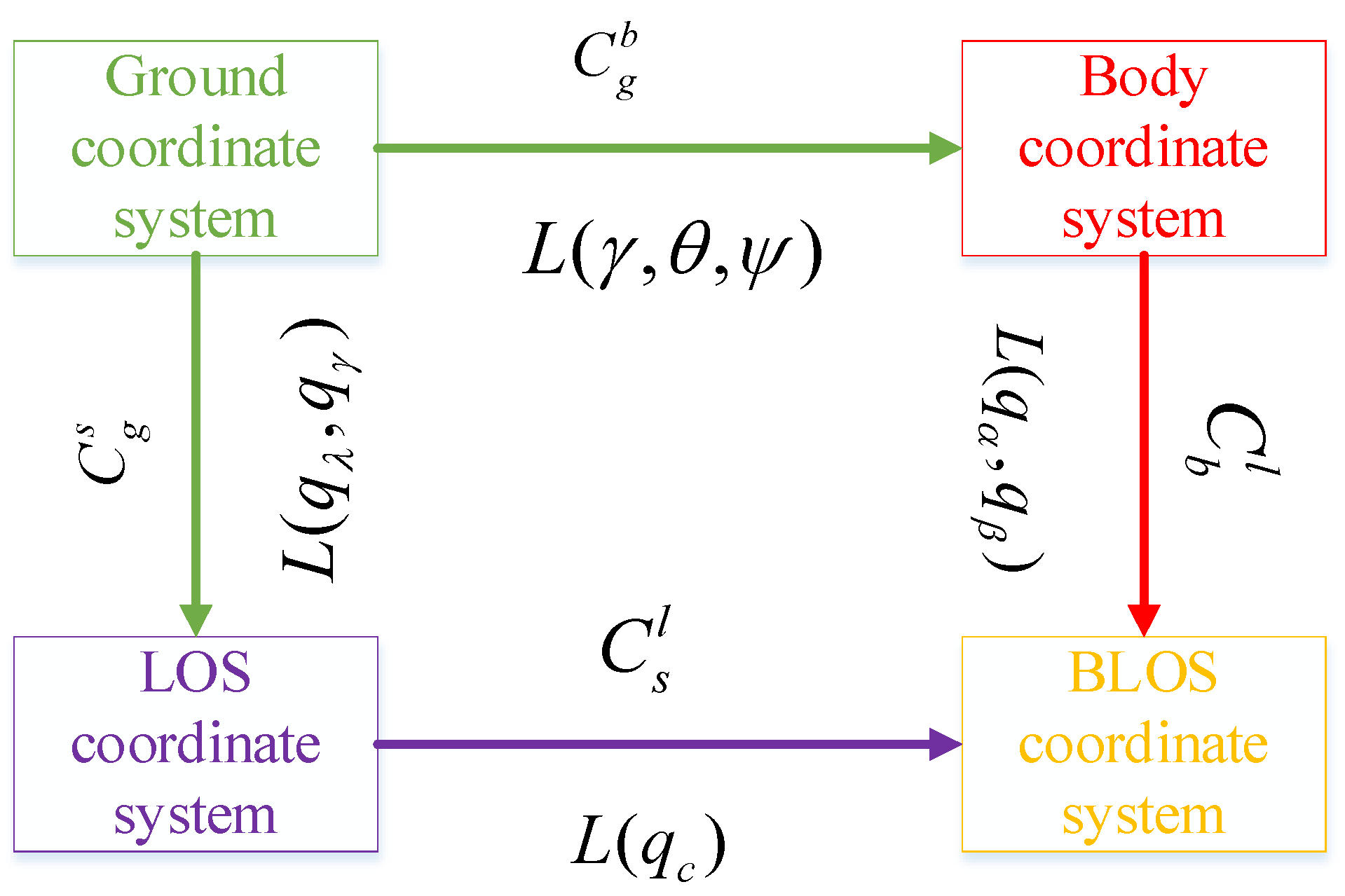

4. Line-of-Sight Angle Rate Decoupling Equation

5. Improved IMMCSRIF

5.1. Development of IMMCSRIF

- (1)

- The one-step predicted value is calculated as follows:where is expressed as the corresponding weight of point set, the expression of which is shown in Algorithm 1.

- (2)

- The square root factor of the covariance matrix of the prediction error is calculated as follows:where denotes the difference between the volume point of the state variable and the predicted value of the estimated state, while is obtained by performing SVD on the system noise covariance matrices .

- (1)

- The predictive information vector is calculated as follows:

- (2)

- The square root factor of the covariance matrix of the prediction error is calculated as follows:

| Algorithm 1: Summary of the IMMCSRIF algorithm |

| 1. Determine the initial filtering parameters |

| , . , |

| 2. Prediction |

are

|

| 3. Update |

For the j-th iteration:

end |

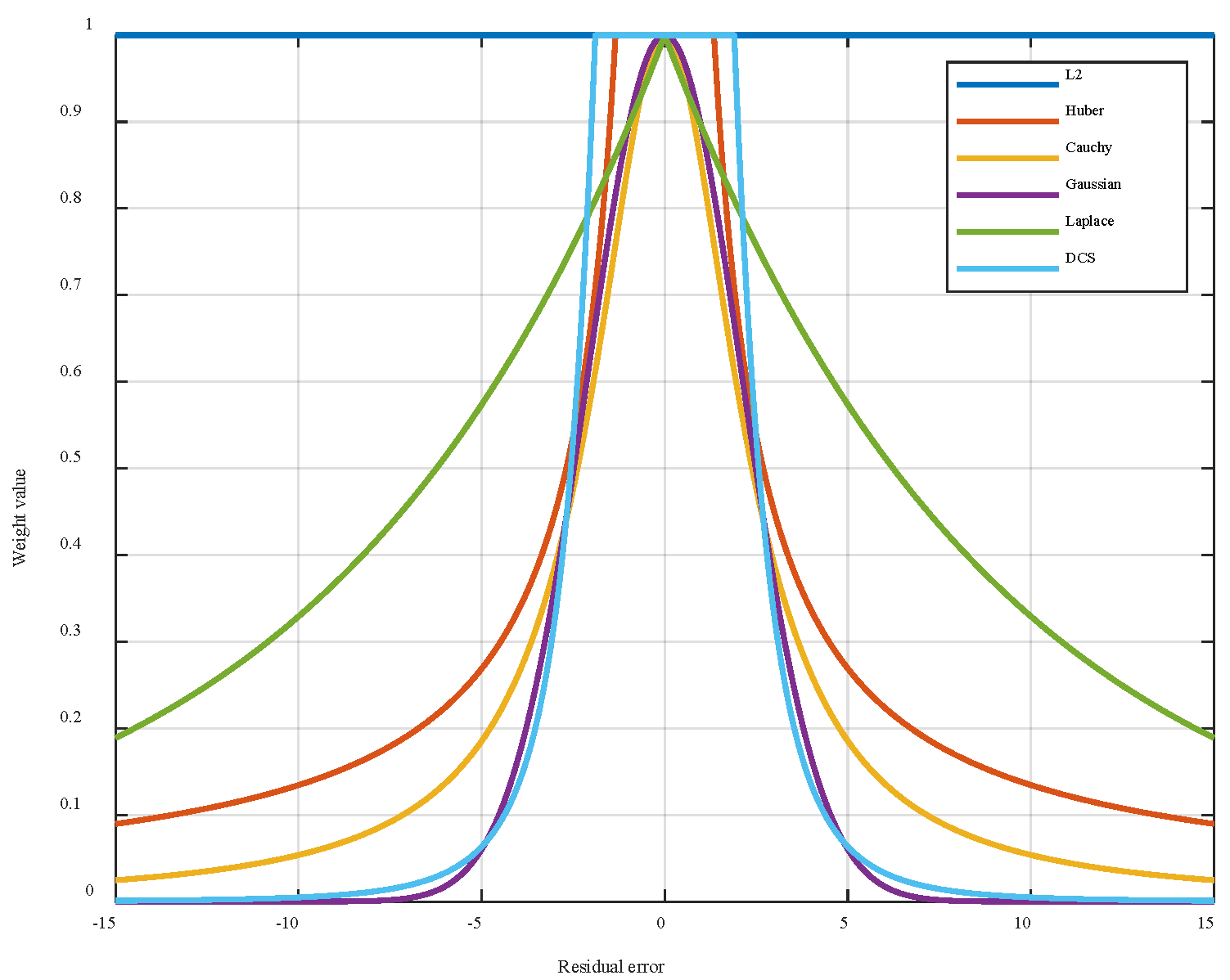

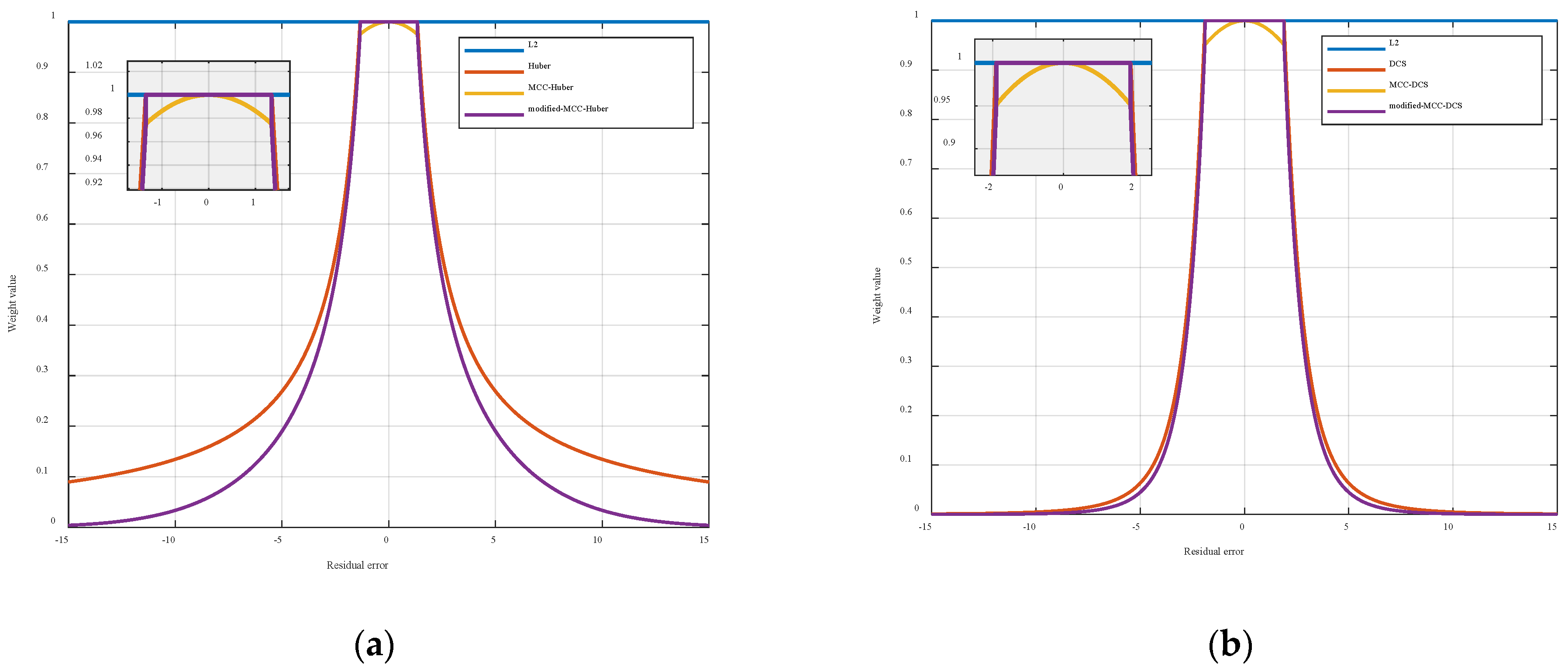

5.2. Improved Robust Kernel Function

6. Simulation and Analysis

- denotes ARMSE achieved by the filtering algorithm exhibiting the highest estimation accuracy.

- denotes the ARMSE of the specific filtering algorithm under evaluation.

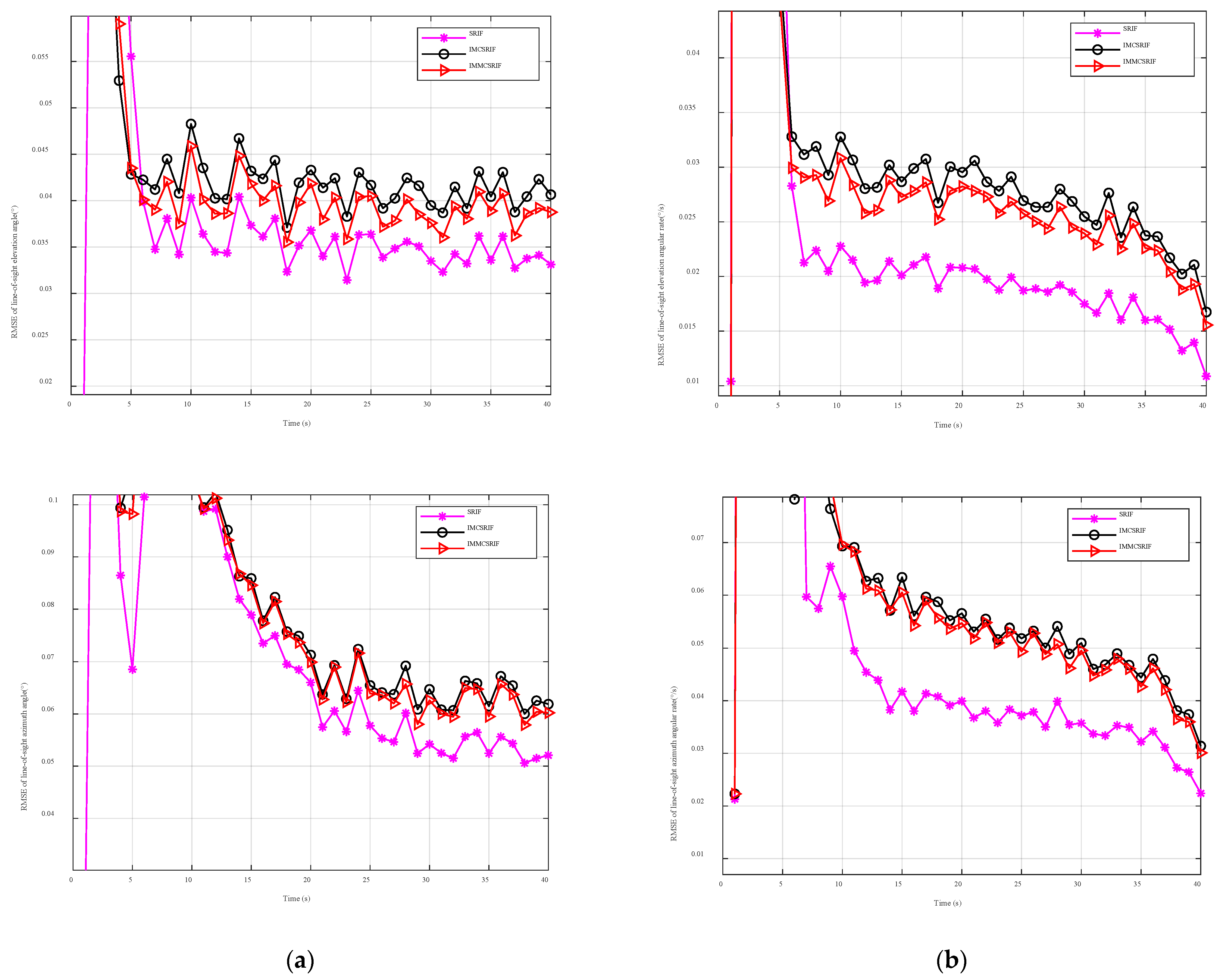

6.1. Comparative Study Under Gaussian Observation Noise

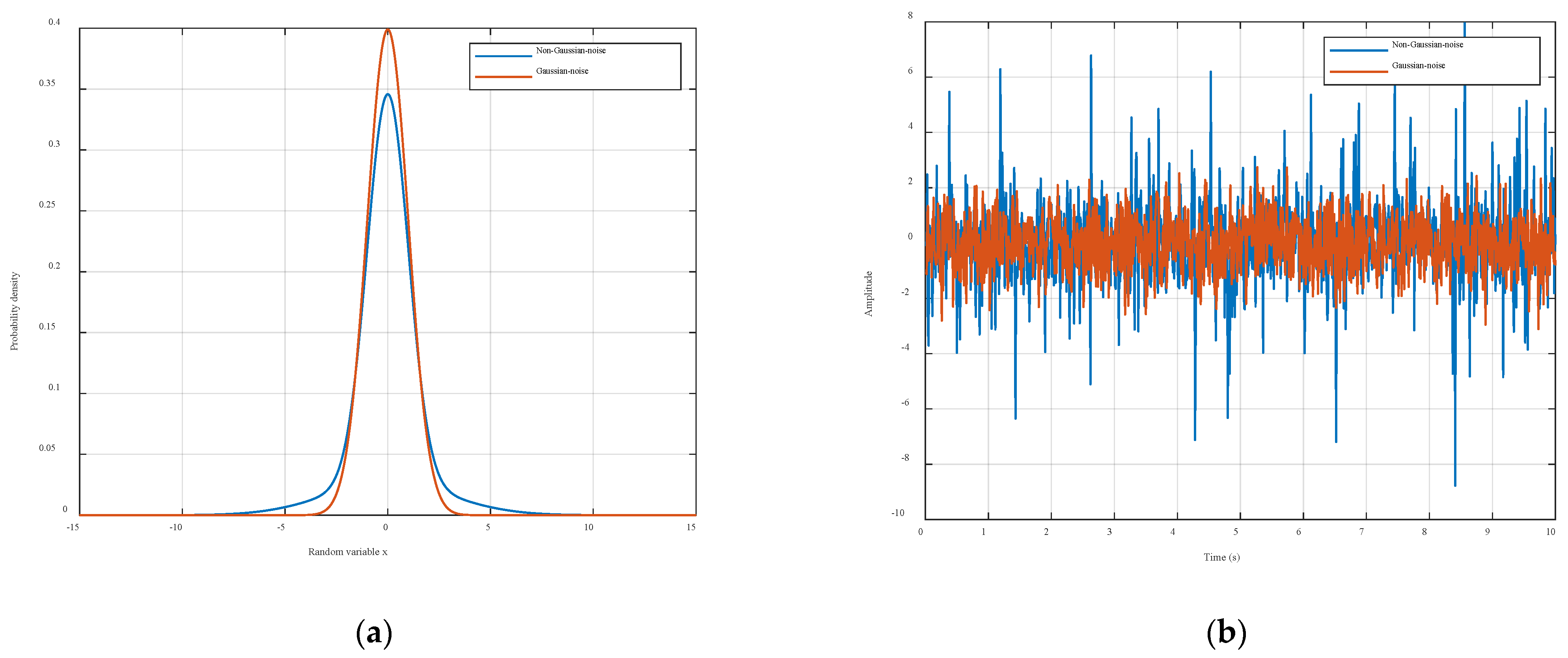

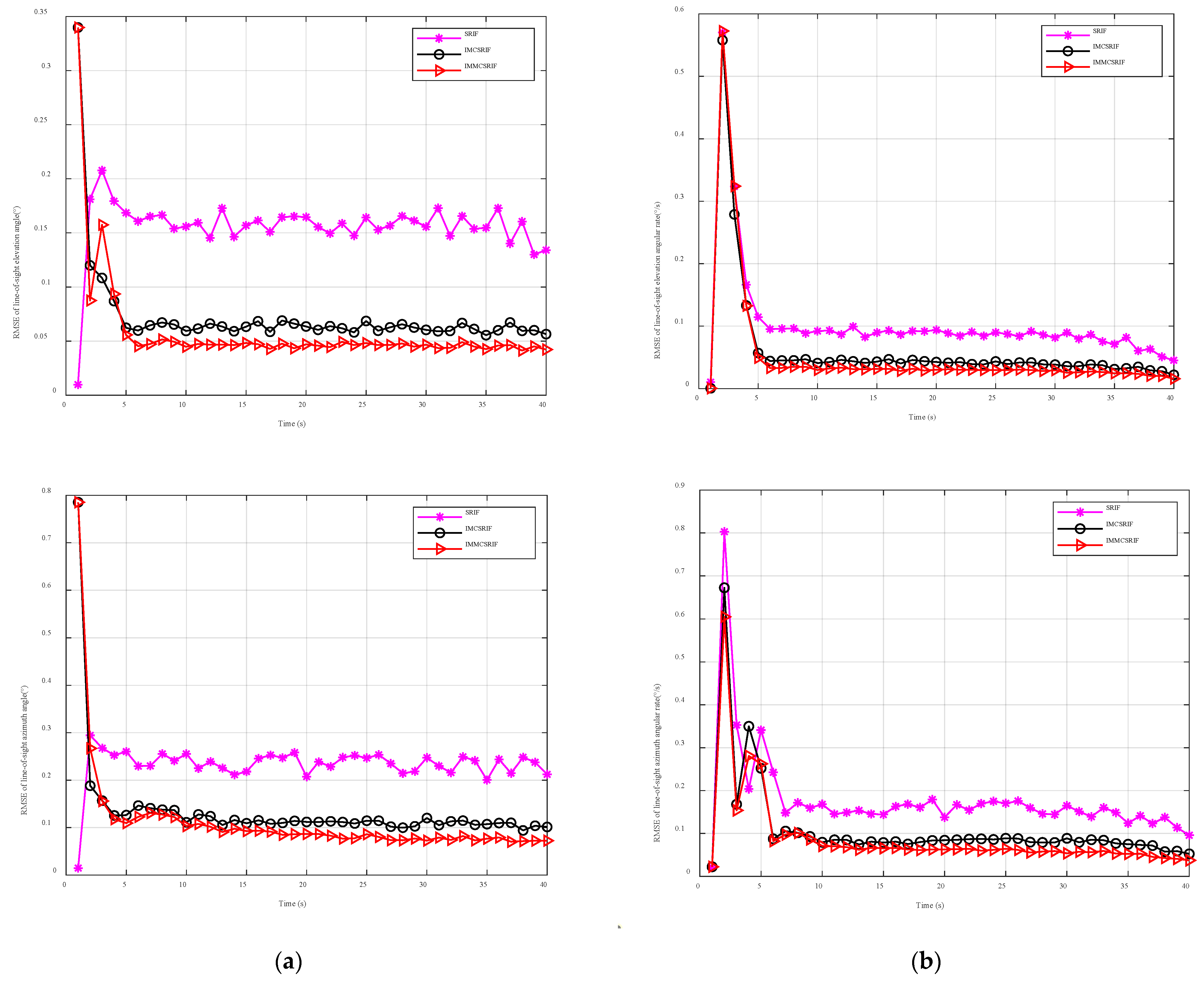

6.2. Comparative Study Under Non-Gaussian Observation Noise

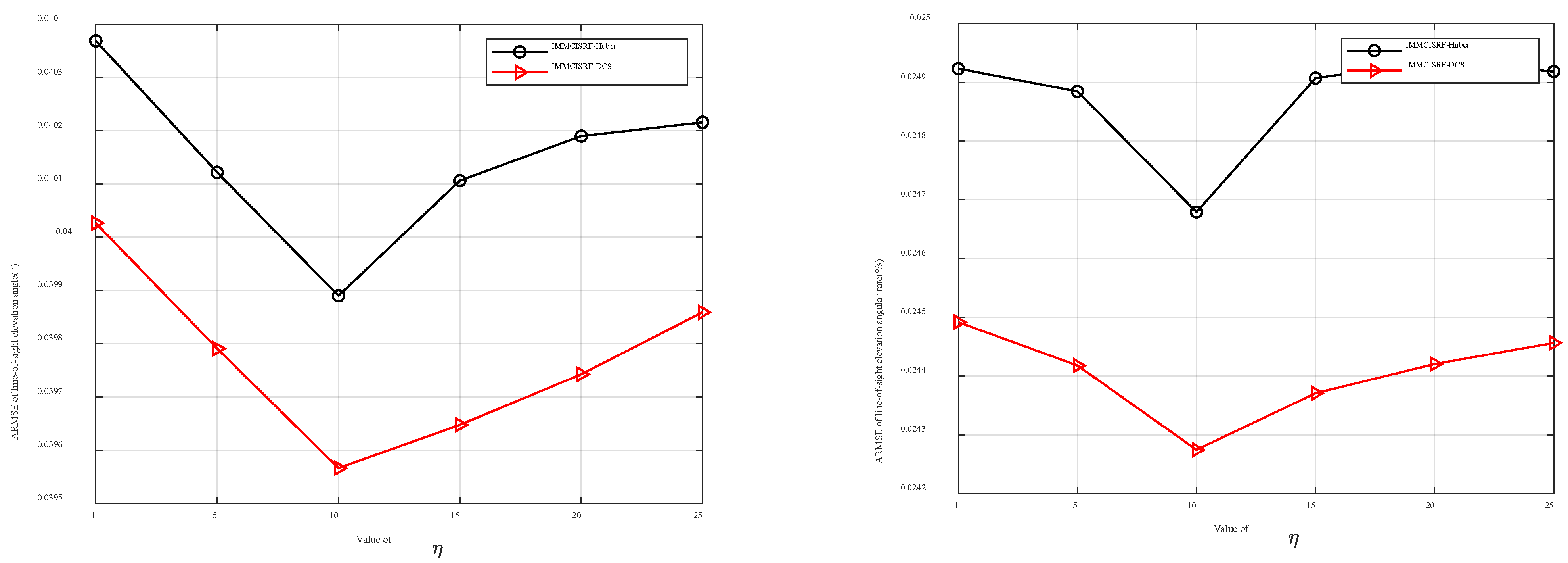

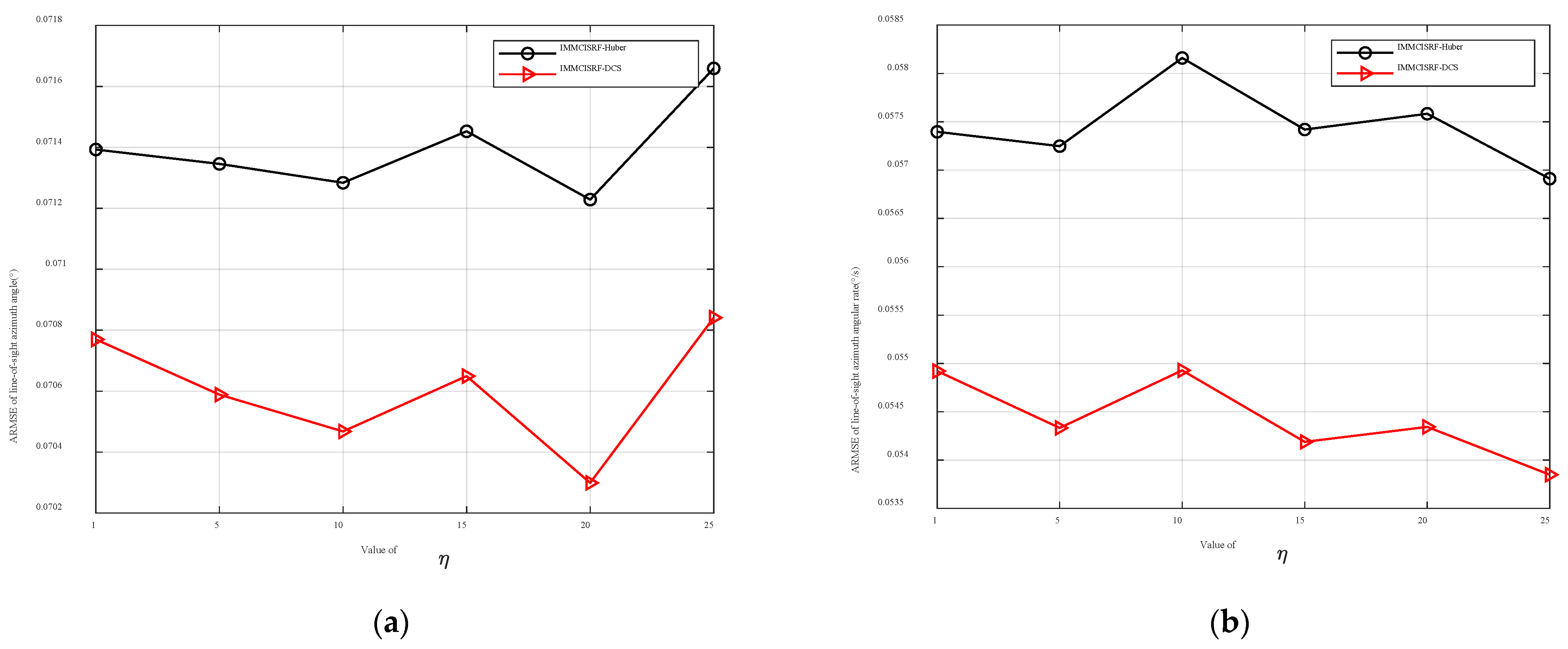

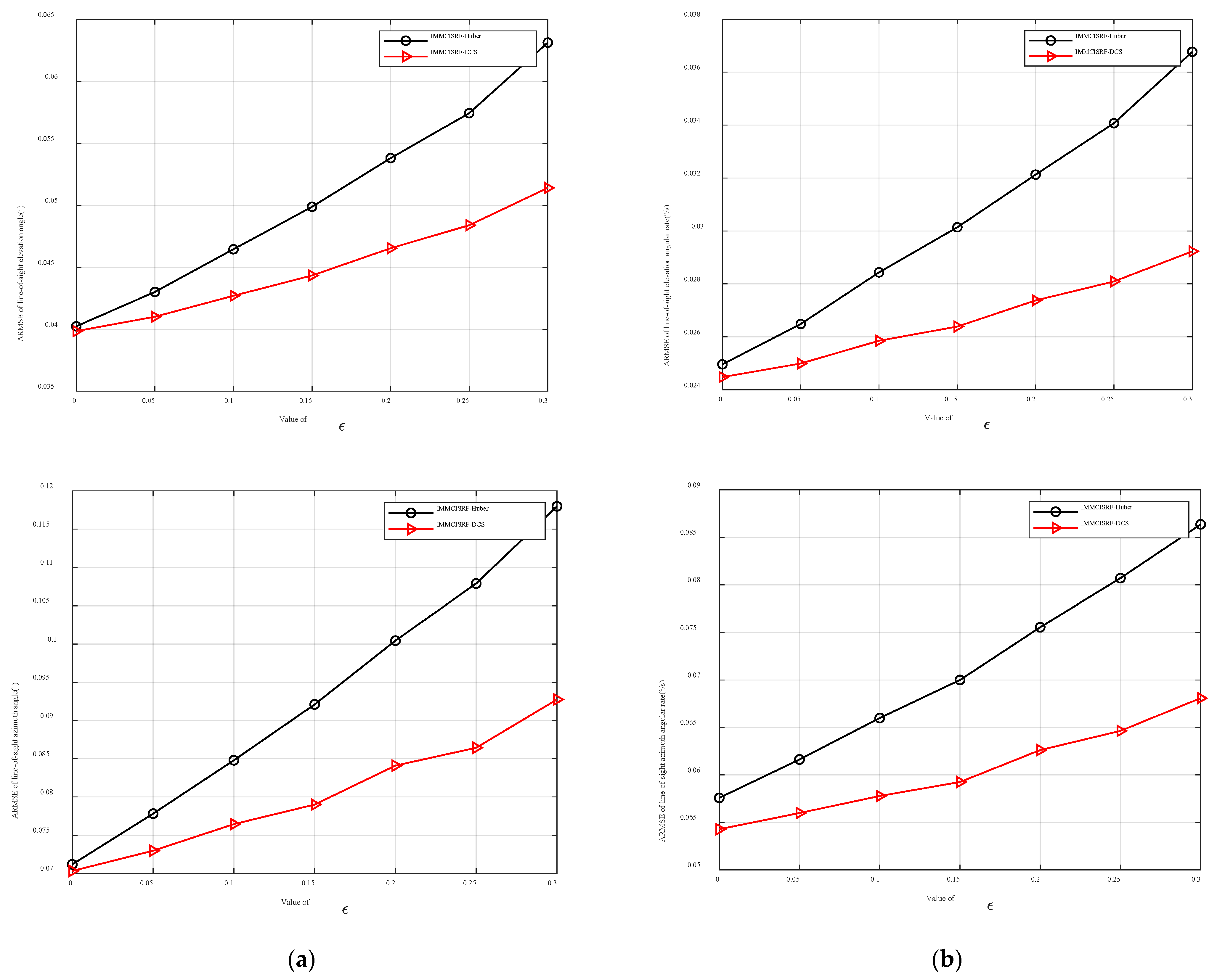

6.3. Kernel Comparison

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARMSE | Average root mean squared error |

| DCS | Dynamic covariance scaling |

| EKF | Extended Kalman filter |

| GML | Generalized maximum likelihood estimation |

| IMCIF | Iterative maximum correlation entropy information filter |

| IMMCSRIF | Iterative maximum correlation entropy square root information filter based on a generalized M estimation |

| IRLS | Iteratively reweighted least squares |

| ITL | Information theory learning |

| MCC | Maximum correlation entropy criteria |

| MCC-DCS | Maximum correntropy criterion with dynamic covariance scaling |

| MCC-Huber | Maximum correntropy criterion with Huber |

| MEE | Minimum error entropy |

| MMCKF | Maximum correlation entropy Kalman filter based on a generalized M estimation |

| MMCSRIF | Maximum correlation entropy square root information filter based on a generalized M estimation |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| SRIF | Square root information filter |

| SVD | Singular value decomposition |

| UKF | Unscented Kalman filter |

References

- Borg, S. Below the radar. Examining a small state’s usage of tactical unmanned aerial vehicles. Def. Stud. 2020, 20, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhury, A.; Sadhu, S.; Ghoshal, T.K. Alternative scheme for guidance signal filtering in a strapdown seeker. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 238, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ryoo, C.K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J. Guidance and control for missiles with a strapdown seeker. In Proceedings of the 2011 11th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, Goyang, Republic of Korea, 26–29 October 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 969–972. [Google Scholar]

- Maley, J.M. Line of sight rate estimation for guided projectiles with strapdown seekers. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 5–9 January 2015; p. 0344. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Chu, H.; Zhang, B.; Jia, H.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Line-of-sight rate estimation based on UKF for strapdown seeker. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 185149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Shan, J.; Liu, Y. Adaptive unscented Kalman filter based line of sight rate for strapdown seeker. In Proceedings of the 2018 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Xi’an, China, 30 November–2 December 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 886–891. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J. Cauchy-based Robust Kalman Filter applied in Guidance Information Estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Guidance, Navigation and Control, Changsha, China, 9–11 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Boncelet, C.G.; Dickinson, B.W. An approach to robust Kalman filtering. In Proceedings of the 22nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Antonio, TX, USA, 14–16 December 1983; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 304–305. [Google Scholar]

- Karlgaard, C.D.; Schaub, H. Comparison of several nonlinear filters for a benchmark tracking problem. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference and Exhibit, Keystone, CO, USA, 21–24 August 2006; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2006; p. 6243. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cui, N.; Guo, J. Huber-based unscented filtering and its application to vision-based relative navigation. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2010, 4, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Hu, B.; Chang, G.; Li, A. Huber-based novel robust unscented Kalman filter. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2012, 6, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlgaard, C.D. Nonlinear regression Huber-Kalman filtering and fixed interval smoothing. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2015, 38, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hawary, F.; Jing, Y. Robust regression-based EKF for tracking underwater targets. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 1995, 20, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlgaard, C.D.; Schaub, H. Huber-based divided difference filtering. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2007, 30, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamennoni, G.; Nieto, J.I.; Nebot, E.M. Approximate inference in statespace models with heavy-tailed noise. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2012, 60, 5024–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Chambers, J. Robust student’s t based nonlinear filter and smoother. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2016, 52, 2586–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Robust student’s t-based stochastic cubature filter for non-linear systems with heavy-tailed process and measurement noises. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 7964–7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, Z.; Chambers, J.A. A novel robust student’s t-based Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 53, 1545–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Chang, L.; Zha, F. New look at the student’s t-based Kalman filter from maximum a posterior perspective. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2018, 12, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Asymptotic form of the Kullback-Leibler divergence for multivariate asymmetric heavy-tailed distributions. Phys. A 2014, 395, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Xu, B.; Wu, Z.; Honeine, P. Maximum correntropy unscented filter. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2017, 48, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y. Maximum correntropy unscented Kalman and information filters for non-Gaussian measurement noise. J. Frankl. Inst. 2017, 354, 8659–8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Iterated maximum correntropy unscented Kalman filters for non-Gaussian systems. Signal Process. 2019, 163, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Peng, B. Robust adaptive filtering based on M-estimation-based minimum error entropy criterion. Inf. Sci. 2024, 658, 120026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Valle, R.B.; Contreras-Reyes, J.E.; Genton, M.G. Shannon Entropy and Mutual Information for Multivariate Skew-Elliptical Distributions. Scand. J. Stat. 2013, 40, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Reyes, J.E.; Idrovo-Aguirre, B.J. Backcasting and forecasting time series using detrended cross-correlation analysis. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2020, 560, 125109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Fisher information and uncertainty principle for skew-gaussian random variables. Fluct. Noise Lett. 2021, 20, 2150039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Jensen-autocorrelation function for weakly stationary processes and applications. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2024, 470, 134424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Chen, S.; Xie, M.; Liu, C.; Zheng, L. Training multi-source domain adaptation network by mutual information estimation and minimization. Neural Netw. 2024, 171, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazmi, O.; Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Belief inaccuracy information measures and their extensions. Fluct. Noise Lett. 2024, 23, 2450041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Principe, J.C. Maximum correntropy Kalmal filter. Automatica 2017, 76, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, S.H.; Quaez, U.J.; Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Rényi entropy for multivariate controlled autoregressive moving average systems. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2025, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünderhauf, N.; Protzel, P. Switchable Constraints for Robust Pose Graph SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1879–1884. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, P.; Tipaldi, G.D.; Spinello, L.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Robust Map Optimization Using Dynamic Covariance Scaling. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Karlsruhe, Germany, 6–10 May 2013; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, P. Robust Graph-Based Localization and Mapping. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Freiburg, Breisgau, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, T.; Bruyninckx, H.; De Schuller, J. Comment on ‘A New Method for the Nonlinear Transformation of means and Covariances in Filters and Estimators’. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2002, 47, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tan, P.; Liu, W.; Cui, N. Robust recursive sigma point Kalman filtering for Huber-based generalized M-estimation. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 38, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Cui, N. Optimization-based iterative and robust strategy for spacecraft relative navigation in elliptical orbit. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 108138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.J. Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter. Ann. Math. Stat. 1964, 35, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravkin, A.Y.; Bell, B.M.; Burke, J.V.; Pillonetto, G. An L1-Laplace Robust Kalman Smoother. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2011, 56, 2898–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, K. Unified Form for the Robust Gaussian Information Filtering Based on M-Estimate. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2017, 24, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Shen, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, S. Robust Cauchy kernel conjugate gradient algorithm for non-Gaussian noises. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2021, 28, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cui, N.; Mu, R. Dynamic-covariance-scaling-based robust sigma-point information filtering. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2021, 44, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Rényi entropy and complexity measure for skew-gaussian distributions and related families. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2015, 433, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Li, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, W.; Guo, L. Composite disturbances nonlinear filtering for simultaneous state and unknown input estimation under non-gaussian noises. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Kernel Function | MCC-Kernel Function | Improved MCC-Kernel Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huber | , | , | , |

| DCS | , |

| Parameter | Corresponding Value |

|---|---|

| Initial missile position | (0 km, 0 km, 0 km) |

| Initial target position | (10 km, 5 km, 10 km) |

| Initial missile velocity | (0.6 km/s, 0, 0) |

| Initial target velocity | (0.364 km/s, 0, 0.21 km/s) |

| Discrete sampling period | 100 ms |

| Parameter | Corresponding Value |

|---|---|

| Initial covariance matrix of filters | |

| Covariance matrix of process noise | |

| Covariance matrix of observation noise | |

| Initial state vector | |

| Perturbing parameter in the case of non-Gaussian noise | 0.2 |

| Algorithms | Gaussian Noise | Non-Gaussian Noise (η) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRIF | 0.0339 | 0.0170 | 0.0619 | 0.0343 | 0.1522 | 0.0764 | 0.2334 | 0.1434 |

| IMCSRIF | 0.0402 | 0.0248 | 0.0699 | 0.0485 | 0.0605 | 0.0361 | 0.1082 | 0.0737 |

| IMMCSRIF | 0.0382 | 0.0232 | 0.0686 | 0.0470 | 0.0455 | 0.0265 | 0.0821 | 0.0554 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Tan, P. Generalized M-Estimation-Based Framework for Robust Guidance Information Extraction. Entropy 2025, 27, 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121217

Ren J, Zhang X, Li S, Tan P. Generalized M-Estimation-Based Framework for Robust Guidance Information Extraction. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121217

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Jiawei, Xiaoyu Zhang, Shoupeng Li, and Panlong Tan. 2025. "Generalized M-Estimation-Based Framework for Robust Guidance Information Extraction" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121217

APA StyleRen, J., Zhang, X., Li, S., & Tan, P. (2025). Generalized M-Estimation-Based Framework for Robust Guidance Information Extraction. Entropy, 27(12), 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121217