Abstract

We propose a two-sample testing procedure for high-dimensional time series. To obtain the asymptotic distribution of our -type test statistic under the null hypothesis, we establish high-dimensional central limit theorems (HCLTs) for an -mixing sequence. Specifically, we derive two HCLTs for the maximum of a sum of high-dimensional -mixing random vectors under the assumptions of bounded finite moments and exponential tails, respectively. The proposed HCLT for -mixing sequence under bounded finite moments assumption is novel, and in comparison with existing results, we improve the convergence rate of the HCLT under the exponential tails assumption. To compute the critical value, we employ the blockwise bootstrap method. Importantly, our approach does not require the independence of the two samples, making it applicable for detecting change points in high-dimensional time series. Numerical results emphasize the effectiveness and advantages of our method.

1. Introduction

A fundamental testing problem in multivariate analysis involves assessing the equality of two mean vectors, denoted as and . Since its inception by [1], the Hotelling test has proven to be a valuable tool in multivariate analyses. Subsequently, numerous studies have addressed the testing of , within various contexts and under distinct assumptions. See refs. [2,3], along with their respective references.

Consider two sets of observations, and , where and . These observations are drawn from two populations with means and , respectively. The classical test aims to test the hypotheses:

When and are two independent sequences and independent with each other, a considerable body of literature focuses on testing Hypothesis (1). The -type test statistic corresponding to (1) is of the form , where , and is the weight matrix. A straightforward choice for is the identity matrix [4,5], implying equal weighting for each dimension. Several classical asymptotic theories have been developed based on this selection of . However, this choice disregards the variability in each dimension and the correlations between them, resulting in suboptimal performance, particularly in the presence of heterogeneity or the existence of correlations between dimensions. In recent decades, numerous researchers have investigated various choices for along with the corresponding asymptotic theories. See refs. [6,7]. In addition, some researchers have developed a framework centered on -type test statistics, represented as [8,9,10]. Extreme value theory plays a pivotal role in deriving the asymptotic behaviors of these test statistics.

However, when and are two weakly dependent sequences and are not independent of each other, the above methods may not work well. In this paper, we introduce an -type test statistic for testing under two dependent sequences. Based on , which represents the variance of , we construct a Gaussian maxima, denoted as , to approximate under the null hypothesis. When , can be written as , the maximum of a sum of high-dimensional weakly dependent random vectors, where . Let with ∼ and be a class of Borel subsets in . Define

Paticularly, let consists of all sets of the form : with some . Then we have

Note that is the Kolmogorov distance between and .

When dimension p diverges exponentially with respect to the sample size n, several studies have focused on deriving under a weakly dependent assumption. Based on the coupling method for -mixing sequence, ref. [11] obtained under the -mixing condition, contributing to the understanding of such phenomena. Ref. [12] extended the scope of the investigation to the physical dependence framework introduced by [13]. Considering three distinct types of dependence—namely -mixing, m-dependence, and physical dependence measures—ref. [14] made significant strides. They established nonasymptotic error bounds for Gaussian approximations of sums involving high-dimensional dependent random vectors. Their analysis encompassed various scenarios of , including hyper-rectangles, simple convex sets, and sparsely convex sets. Let be the class of all hyper-rectangles in . Under the -mixing scenario and some mild regularity conditions, [14] showed

hence the Gaussian approximation holds if . In this paper, under some conditions similar to or even weaker than [14], we obtain

which implies the Gaussian approximation holds if . Refer to Remark 1 for more details on the comparison of the convergence rates. By using the Gaussian-to-Gaussian comparison and Nazarov’s inequality for p-dimensional random vectors, we can easily extend our result to . Given that our framework and numerous testing procedures rely on -type test statistics, we thus propose our results under . When p diverges polynomially with respect to n, to the best of our knowledge, there is no existing literature providing the convergence rate of for -mixing sequences under bounded finite moments.

Based on the Gaussian approximation for high-dimensional independent random vectors [15,16], we employ the coupling method for -mixing sequence [17] and “big-and-small” block technique to specify the convergence rate of under various divergence rates of p. For more details, refer to Theorem 1 in Section 3.1 and its corresponding proof in Appendix A. Given that is typically unknown in practice, we develop a data-driven procedure based on blockwise wild bootstrap [18] to determine the critical value for a given significance level . The blockwise wild bootstrap method is widely used in the time series analysis. See [19,20] and references within.

The independence between and is not a necessary assumption in our method. We only require the pair sequence is weakly dependent. Therefore, our method can be applied effectively to detect change points in high-dimensional time series. Further details on this application can be found in Section 4.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the test statistic and the blockwise bootstrap method. The convergence rates of Gaussian approximations for high-dimensional -mixing sequence and the theoretical properties of the proposed test can be found in Section 3. In Section 4, an application to change point detection for high-dimensional time series is presented. The selection method for tuning parameter and a simulation study to investigate the numerical performance of the test are displayed in Section 5. We apply the proposed method to the opening price data from multiple stocks in Section 6. Section 7 provides discussions on the results and outlines our future work. The proofs of the main results in Section 3 are detailed in the Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D.

Notation:

For any positive integer , we write . We use to denote the -norm of the p-dimensional vector . Let and represent the greatest integer less than or equal to x and the smallest integer greater than or equal to x, respectively. For two sequences of positive numbers and , we write or if for some positive constant . Let if and hold simultaneously. Denote . For any matrix , let and be the spectral norm of . Additionally, denote as the smallest eigenvalue of . Let be the indicator function. For any , denote and . Given , we define the function for any . For a real-valued random variable , we define . Throughout the paper, we use to denote two generic finite constants that do not depend on , and may be different in different uses.

2. Methodology

2.1. Test Statistic and Its Gaussian Analog

Consider two weakly stationary time series and with and . Let and . The primary focus is on testing equality of mean vectors of the two populations:

Given the observations and , the estimations of and are, respectively, and . In this paper, we assume . It is natural to consider the -type test statistic . Write . Define two new sequences and with

For each , let

Then, can be rewritten as

We reject the null hypothesis if , where represents the critical value at the significance level . Determining involves deriving the distribution of under . However, due to the divergence of p in a high-dimensional scenario, obtaining the distribution of is challenging. To address this challenge, we employ the Gaussian approximation theorem [15,16]. We seek a Gaussian analog, denoted as , satisfying the property that the Kolmogorov distance between and converges to zero under . Then, we can replace by . Define a p-dimensional Gaussian vector

We then define the Gaussian analogue of as

Proposition 1 below demonstrates that the null distribution of can be effectively approximated by the distribution of .

2.2. Blockwise Bootstrap

Note that the long-run covariance matrix specified in (3) is typically unknown. As a result, determining through the distribution of becomes challenging. To address this challenge, we introduce a parametric bootstrap estimator for using the blockwise bootstrap method [18].

For some positive constant , let and be the size of each block and the number of blocks, respectively. Denote for and . Let be the sequence of i.i.d. standard normal random variables and , where if . Define the bootstrap estimator of as

where . Based on this estimator, we define the estimated critical value as

where . Then, we reject the null hypothesis if . The procedure for selecting the parameter (or block size S) is detailed in Section 5.1. In practice, we obtain through the following bootstrap procedure: Generate K independent sequences , with each generated as . For each , calculate with . Then, is the -th largest value among . Here, K is the number of bootstrap replications.

3. Theoretical Results

We employ the concept of ‘-mixing’ to characterize the serial dependence of , with the -mixing coefficient at lag defined as

where and are the -fields generated by and , respectively. We call the sequence is -mixing if as .

3.1. Gaussian Approximation for High-Dimensional -Mixing Sequence

To show that the Kolmogorov distance between and converges to zero under various divergence rates of p, we need the following central limit theorems for high-dimensional -mixing sequence.

Theorem 1.

Let be an α-mixing sequence of p-dimensional centered random vectors and denote the α-mixing coefficients of , defined in the same manner as (5). Write and with . Define

- (i)

- If , and for some , and constants , we haveprovided that , where .

- (ii)

- If , and for some , , and constants , we haveprovided that and .

Remark 1.

In scenarios where the dimension p diverges polynomially with respect to n, Theorem 1(i) represents a novel contribution to the existing literature. Moreover, if (i.e., for some constant ), we have , and thus if . Compared with Theorem 1 in [14], which provides a Gaussian approximation result when p diverges exponentially with respect to n, Theorem 1(ii) has three improvements. Firstly, all conditions of Theorem 1(ii) are equivalent to those in Theorem 1 of [14], with the exception that we permit , thereby offering a weaker assumption that is more broadly applicable. Secondly, the convergence rate dependent on n via in Theorem 1(ii) outperforms the rate of demonstrated in Theorem 1 of [14]. Note that the convergence rate in Theorem 1 of [14] can be rewritten as

To ensure , in our result, it is necessary to allow when and when , respectively. Comparatively, the basic requirements under Theorem 1 of [14] are when and when , respectively. Due to when , our result permits a larger or equal divergence rate of p compared with Theorem 1 in [14].

3.2. Theoretical Properties

In order to derive the theoretical properties of , the following regular assumptions are needed.

Assumption 1.

- (i)

- For some , there exists a constant s.t. .

- (ii)

- There exists a constant s.t. for some .

- (iii)

- There exists a constant s.t. .

Assumption 2.

- (i)

- There exists a constant s.t. .

- (ii)

- There exist two constants s.t. .

- (iii)

- There exists a constant s.t. .

Remark 2.

The two mild Assumptions, 1 and 2, delineate the necessary assumptions for to facilitate the development of Gaussian approximation theories for the dimension p divergence, characterized by polynomial and exponential rates relative to the sample size n, respectively. Assumptions 1(i) and 1(ii) are common assumptions in multivariate time series analysis. Due to , if and , then Assumption 1(i) holds, as verified by the triangle inequality. Additionally, Assumption 1(iii) necessitates the strong nondegeneracy of , a requirement commonly assumed in Gaussian approximation theories (see refs. [21,22], among others). Note that Assumption 2(iii) is implied by Assumption 1(iii). The latter assumption only necessitates the nondegeneracy of . We can modify Assumption 2(i) to for any , a standard assumption in the literature on ultra-high-dimensional data analysis. This assumption ensures subexponential upper bounds for the tail probabilities of the statistics in question when , as discussed in [23,24]. The requirement of sub-Gaussian properties in Assumption 2(i) is made for the sake of simplicity. If and share the same tail probability, Assumption 2(i) is satisfied automatically. Assumption 2(ii) necessitates that the α-mixing coefficients decay at an exponential rate.

Write . Define two cases with respect to the distinct divergence rates of p as

- Case1: and satisfy Assumption 1, and the dimension p satisfies and ;

- Case2: and satisfy Assumption 2, and the dimension p satisfies and .

Note that mandates the maximum difference between the two sample sizes. Proposition 1 below demonstrates that, under the aforementioned cases and , the Kolmogorov distance between and converges to zero as the sample size approaches infinity. Proposition 1 can be directly derived from Theorem 1. Note that, in the scenario where the dimension p diverges in a polynomial rate with respect to n, obtaining Proposition 1 requires only and , an assumption weaker than Assumption 1. The more stringent restrictions and in Assumption 1 are imposed to establish the results presented in Theorems 2 and 3.

Proposition 1.

In either Case1 or Case2, it holds under the null hypothesis that

According to Proposition 1, the critical value can be substituted with . However, in practical scenarios, the long-run covariance defined in (3) is typically unknown. This implies that obtaining directly from the distribution of is not feasible. We introduce a bootstrap method for obtaining the estimator defined in (4). In situations where the dimension p diverges at a polynomial rate relative to the sample size n, we require an additional Assumption 3 to ensure that serves as a reliable estimator for . Assumption 3 places restrictions on the cumulant function, a commonly assumed criterion in time series analysis. Refer to [25,26] for examples of such assumptions in the literature.

Assumption 3.

For each , define , where and . There exists a constant s.t.

Similar to Case1 and Case2, we consider two cases corresponding to different divergence rates of the dimension p, as outlined below:

- Case3: and satisfy Assumptions 1 and 3.

- Case4: and satisfy Assumption 2.

Theorem 2.

In either Case3 with and , or Case4 with and , it holds under that . Moreover, it holds under that

Theorem 3.

In either Case3 with or Case4 with , if , it holds that

Remark 3.

The different requirements for the divergence rates of p follow from the fact that we do not rely on the Gaussian approximation and comparison results under certain alternative hypotheses. By Theorem 2 and Theorem 3, the optimal selections for ϑ are and in Case3 and Case4, respectively. This implies that holds with in Case3 and in Case4. Under certain alternative hypotheses, holds with in Case3 and in Case4.

4. Application: Change Point Detection

In this section, we elaborate that our two-sample testing procedure can be regarded as a novel method for detecting change points for high-dimensional time series. To illustrate, we provide a notation for the detection of a single change point, with the understanding that it can be easily extended to the multiple change points case.

Consider a p-dimensional time series . Let . Consider the following hypothesis testing problem:

Here, is the unknown change point. Let w be a positive integer such that . We define , and . Then for each , define and . Thus,

Assume , which represents the sparse signals case. Define and with two well-defined thresholds . Due to the symmetry of and , it holds under that

The sample estimators of , and are, respectively, , and . Based on the method proposed in Section 2, with , we define the following two test statistics:

Given a significance level , we choose and , where and are, respectively, the -quantiles of the distributions of and . The estimated critical values and can be obtained by (4). Thus, and . Hence, the estimator of is given by

We utilize as an illustrative example to elucidate the applicability of our proposed method. Let w be an even integer. For any , we have , where the sequence possesses the same weakly dependence properties and similar moment/tail conditions as . For , let be defined as when and when . Additionally, define as when and when . Then, can be expressed as , and shares the same weakly dependence properties and similar moment/tail conditions as . Hence, our method can be applied to change point detection.

The selections of w and are crucial in this method. We will elaborate on the specific choices for them in future works.

5. Simulation Study

5.1. Tuning Parameter Selection

Given the observations and , we use the minimum volatility (MV) method proposed in [27] to select the block size S.

When the data are independent, by the multiplier bootstrap method described in [28], we set (thus ). In this case,

proves to be a reliable estimator of introduced in Section 3. When the data are weakly dependent (and thus nearly independent), we expect a small value for S and a large value for B. Therefore, we recommend exploring a narrow range of S, such as , where m is a moderate integer. In our theoretical proof, the quality of the bootstrap approximation depends on how well the approximates the covariance . The idea behind the MV method is that the conditional covariance should exhibit stable behavior as a function of S within an appropriate range. For more comprehensive discussions on the MV method and its applications in time series analysis, we refer readers to [27,29]. For a moderately sized integer m, let be a sequence of equally spaced candidate block sizes, and , . For each , let

where and . Then for each , we compute

where is the standard deviation. Then, we select the block size with .

5.2. Simulation Settings

We present the results of a simulation study aimed at evaluating the performance of tests based on , as defined in (2), in finite samples. To assess the finite-sample properties of the proposed test, we employed the following fundamental generating processes: , where is the loading matrix, is a constant function, the parameter a belongs to the set , representing the distance between the null and alternative hypotheses. Additionally, with , where and . Construct such that for , where and for each and . Then and represent the sparse and dense signal cases, respectively. We consider three different loading matrices for as follows:

- (M1).

- Let s.t. , then let .

- (M2).

- Let s.t. , for and otherwise.

- (M3).

- Let , , where , for with , and otherwise. Let .

We assess the finite sample performance of our proposed test (denoted by ) in comparison with tests introduced by [5] (denoted by ), [4] (denoted by ), [6] (denoted by ), and [8] (denoted by ). All tests in our simulations are conducted at the significance level with 1000 Monte Carlo replications, and the number of bootstrap replications is set to 1000. We consider dimensions and sample size pairs .

5.3. Simulation Results

For the testing of the null hypothesis, consider independent generations of and , following the same process as , with identical values for and . The choice of here is made for the sake of simplicity. We exclusively present the simulation results for (M1) in the main body of the paper. The results obtained for (M2) and (M3) are analogous to those of (M1) and are detailed in the Appendix E.

Table 1 presents the performance of various methods in controlling Type I errors based on (M1). As the dimension p or sample size increases, the results of all methods exhibit small changes, except BS’s. When equals 0, indicating samples are generated from independent Gaussian distributions, both Yang’s method and BS’s method effectively control Type I errors at around , while the control achieved by the other three methods is less optimal. It is noteworthy that, with an increase in , the data generated by the AR(1) model significantly influence the other methods. In contrast, Yang’s method demonstrates superior and more stable results with increasing . These comparative effects are also observable in the results based on (M2) and (M3) in the Appendix E. For this reason, we exclusively compare the empirical power results by different methods with .

Table 1.

The Type error rates, expressed as percentages, were calculated by independently generated sequences and based on (M1). The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

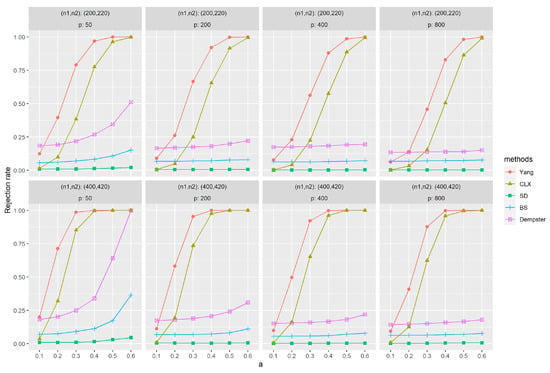

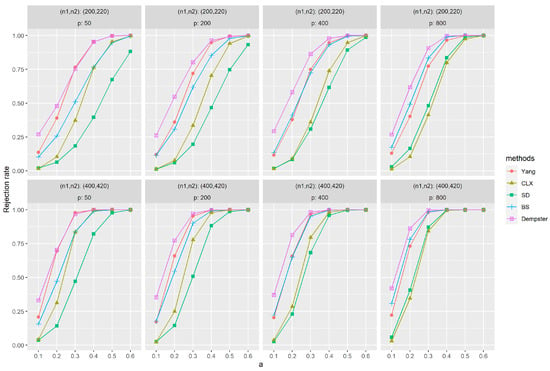

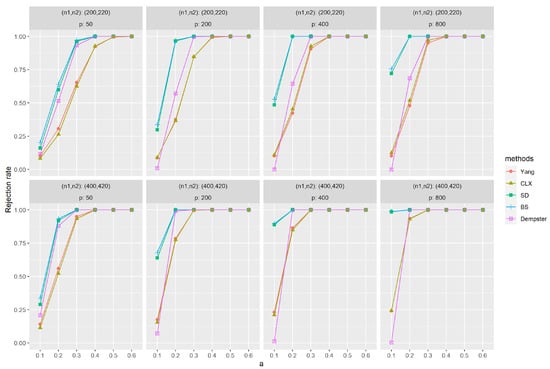

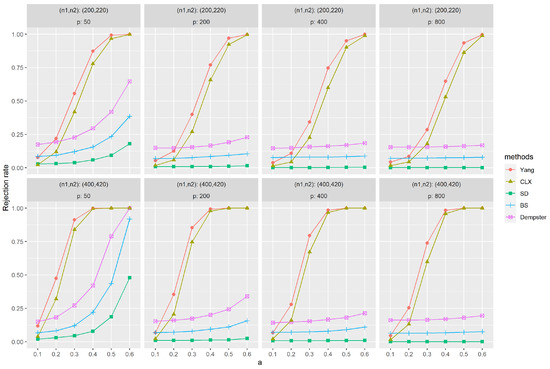

Figure 1 and Figure 2 depict the empirical power results of various methods for sparse and dense signals based on (M1). Similarly, as the dimension p increases, the results of all methods show little variation, except Dempster’s. However, with an increase in sample size , most methods exhibit improvement in their results. In Figure 1, it is evident that Yang’s method outperforms others significantly when the signal is sparse. Methods like SD, BS, and Dempster rely on the -norm of the data, aggregating signals across all dimensions for testing. This makes them less effective when the signal is sparse, i.e., anomalies appear in only a few dimensions. CLX’s approach, akin to Yang’s, tests whether the largest signal is abnormal. Consequently, CLX performs better than the other three methods in scenarios with sparse signals but still falls short of Yang’s method. On the contrary, when the signal is dense, Figure 2 shows that all methods yield favorable results, with Dempster’s method proving to be the most effective. Yang’s method performs at a relatively high level among these methods. In contrast, the CLX’s method, which performs well in sparse signals, exhibits a relatively lower level of performance in dense signals. In conclusion, the proposed method exhibits the most stable performance across all methods and performs exceptionally well on sparse data.

Figure 1.

The empirical powers with sparse signals were evaluated by independently generated sequences based on (M1), and , and based on (M1), and . The parameter a represents the distance between the null and alternative hypotheses. The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

Figure 2.

The empirical powers with dense signals were evaluated by independently generated sequences based on (M1), and , and based on (M1), and . The parameter a represents the distance between the null and alternative hypotheses. The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

6. Real Data Analysis

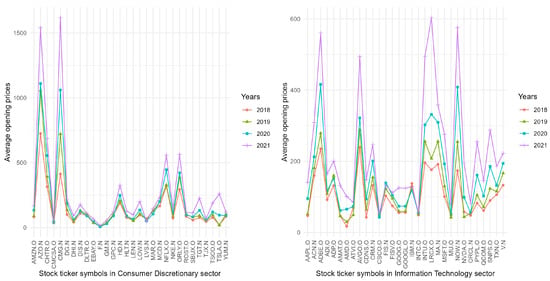

In this section, we apply the proposed method to a dataset comprised of stock data obtained from Bloomberg’s public database. This dataset includes daily opening prices from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2021 for 30 companies in the Consumer Discretionary Sector (CDS) and 31 companies in the Information Technology Sector (ITS), all listed in the S&P 500. The sample sizes for the years 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 are 251, 250, 253, and 252, respectively. The findings are presented in Table 2. Regarding the data for the Consumer Discretionary (CD) and Information Technology (IT) sectors, all p-values from the tests between two consecutive years are 0. This suggests a significant variation in the average annual opening prices across different years for both CDs and ITs.

Table 2.

The p-values for testing the equality of average annual opening prices across two consecutive years in the Consumer Discretionary Sector and Information Technology Sector, respectively.

For data visualization, Figure 3 displays the average annual opening prices of 30 companies in the CDS (left subgragh) and 31 companies in the ITS (right subgragh) in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021. The two subgraghs both exhibit a pattern of annual growth in the opening prices of nearly every stock. These results are well in line with the conclusion of Table 2.

Figure 3.

The average annual opening prices of 30 Consumer Discretionary corporations and 31 Information Technology corporations in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021.

7. Discussion

In this paper, we propose a two-sample test for high-dimensional time series based on blockwise bootstrap. Our -type test statistic is designed to detect the largest abnormal signal among dimensions. Unlike some frameworks, we do not necessarily require independence within each observation or between the two sets of observations. Instead, we rely on the weak dependence property of the pair sequence to ensure the asymptotic properties of our proposed method. We derive two Gaussian approximation results for two cases in which the dimension p diverges, one at a polynomial rate relative to the sample size n and the other at an exponential rate relative to the sample size n. In the bootstrap procedure, the block size serves as the tuning parameter, and we employ the minimum volatility method, as proposed by [27], for block size selection.

Our test statistic is designed to pinpoint the maximum value among dimensions, facilitating the detection of significant differences in certain dimensions. In cases where differences in each dimension are minimal, it is more appropriate to consider the -type test statistic rather than the -type one. Consequently, in the absence of prior information, the utilization of test statistics that combine both types proves advantageous. However, deriving theoretical results from such a combined approach is a significant challenge. As discussed in Section 4, our two-sample testing procedure can be applied to change point detection in high-dimensional time series. The choices of w, the size of each subsample mean, and the significance level play crucial roles in this change point detection procedure. We leave these considerations for future research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 1

Appendix A.1. Proof of Theorem 1(i)

Proof.

We first show that, for any with some ,

If , due to , Equation (1.12b) (Davydov’s inequality) of [30] yields

for any . For and , Theorem 6.3 of [30] yields

where are two constants depending only on q, , and . By (A2), it holds that . Due to , we have . By the denifition of , we know that . Thus

where the last inequality follows from . Hence, we have

for any . By combining above results, we complete the proof of (A1).

Now, we begin to prove Theorem 1(i). Define

Let and . Then, we have and . Then, to obtain Theorem 1(i), without loss of generality, it suffices to specify the convergence rate of .

For some constant , let and be the number of blocks and the size of each block, respectively. For simplicity, we assume and . We first decompose the sequence into blocks: for . Let be two non-negative integers such that . We then decompose each to a “large” block with length and a “small” block with length : and . Let . For each and some , define with and with . For each , by Theorem 2 of [17], there exists an independent sequence such that has the same distribution as and

Due to , we have for any , which implies

Define with and

For any , triangle inequality implies

for any , then . Likewise, . Due to , Lemma A.1 of [31] yields

for any . Thus, we can conclude that

Define . By triangle inequality,

By (A1), we have . Thus , and

Similar to (A2), we have for any , and

where the last inequality follows from . Thus, and

Due to having the same distribution as and , by (A3), we have for . Thus, following the same arguments as in the proof of (A7), it holds that

Thus, and

Together with (A8), we have

Let . It holds by (A5) and Markov inequality that

Define and , where . Note that

In this sequel, we specify the convergence rates of , , and , respectively. Note that the -th element of is . Due to having the same distribution as and for any and , it holds by (A3) that

for any and . Thus, we can conclude that . The -th element of is . Note that . Due to , it holds by (A6) that

for any and . Thus, we can conclude that . The -th element of is , and

Similar to the proof of (A2), we have

Similarly, we can also obtain

Thus,

Analogously to the proof of (A2), if , due to ,

Then,

The same result still holds for . Thus, we can conclude that

Then, by (A11), it holds that

for any . Thus, . By (A10), we can conclude that

Let be a sequence of an independent Gaussian vector such that for each , where . By Theorem 1.1 of [15], Cauchy–Schwarz inequality and Jensen’s inequality,

where . Note that

Due to , we have as long as . Thus, if , we have . Since , (A1) yields for any and , which implies

provided that . By Proposition 2.1 of [16], we have

Then, by (A4), (A12), and (A13), we have

provided that . Together with (A9),

provided that . Select , , and . Then, if , we have

Hence, we complete the proof of Theorem 1(i). □

Appendix A.2. Proof of Theorem 1(ii)

Proof.

Define , , and in the same manner as in the proof of Theorem 1(i) with , , and , where . Let

Analogously to (A5), due to , we have

for some , where with specified in the same manner as in the proof of Theorem 1(i), and

Define . By triangle inequality,

Note that for any . Let . By Theorem 1 of [32] and Bonferroni inequality, we have

for any . Similarly, by Theorem 1 of [32] again, for any ,

Then, if ,

Thus, for any and ,

Select for some sufficiently large constant . Thus, for any ,

provided that . Then, by (A15), we can conclude that for any ,

provided that . Similar to (A3), we have

Select for some sufficiently large constant . By (A18) and triangle inequality,

for any . Thus, by (A17), for any ,

provided that . Let for some sufficient large constant . It holds by (A14) that

provided that . Define and , where . Note that

In this sequel, we will specify the convergence rates of , and , respectively. Note that the -th element of is . Due to has the same distribution as and for any and , it holds by (A18) that

for any and . Thus, we can conclude that . The -th element of is . Due to , then it holds by (A16) that

for any and provided that . Thus, we can conclude that provided that . The -th element of is , and

Note that for any constant integer . Equation (1.12b) of [30] yields

Similarly, we can also obtain

Thus,

By Equation (1.12b) of [30], if ,

Thus,

Same result holds for . Thus we can conclude that

Note that the above upper bounds do not depend on . Then by (A22), it holds that . By (A21), we can conclude that

provided that . Let be a sequence of independent Gaussian vector such that for any , where . Due to , we know that provided that and . Due to , it holds that for any and , where the last inequality follows from and the similar arguments as in the proof of (A23). By Theorem 2.1 of [16], we have

provided that and . By Proposition 2.1 of [16] and (A24), we have

By (A20), (A25) and (A26), due to , we have

provided that and . Select . Then , and

provided that and . Thus we complete the proof of Theorem 1(ii). □

Appendix B. Proof of Proposition 1

Proof.

Define

where . Under , we know that . Recall and . Without loss of generality, we assume . By triangle inequality, for any ,

Thus . Write , where diverges at a sufficiently slow rate. Thus, we have

Analogously, we can also obtain that . Thus,

In Case1, by Assumption 1(iii), we have . Then by Lemma A.1 of [31], due to , we have . By Assumption 1(i), we have . Note that . Then by Assumption 1 and Theorem 1(i), due to , we have provided that . Thus, if ,

Similarly, in Case2, by Assumption 2 and Theorem 1(ii) with , we have and provided that . Thus, if ,

We complete the proof of Proposition 1. □

Appendix C. Proof of Theorem 2

Appendix C.1. Proof of Theorem 2 under Case3

Proof.

By Proposition 1 under Case1, it suffices to show

Recall with and , where . Let

By Proposition 2.1 of [16], we have

where

Let . Then, for any , triangle inequality yields

In this sequel, we will specify the upper bounds of , and , respectively. Without loss of generality, we assume with and . By Assumption 1(i), it holds that for some . Then, due to , (A1) yields

By triangle inequality,

By Assumption 3, , which implies

For any and , due to , Equation (1.12b) of [30] yields

Similarly, we also have

Thus,

Analogously, we also have . Combining this with (A29)–(A31), due to ,

Then it holds that

Similar to (A1), we have . Thus, we know that

Note that

For , due to , Equation (1.12b) of [30] yields

Thus,

Similarly, we can also obtain , which implies . Then by (A32) and (A33), it holds that

Then, by Markov’s inequality,

By (A28), due to , it holds that

provided that .

Recall . For any , let and be two constants which satisfy and , respectively. We claim that for any , it holds that as . Otherwise, if , by (A35), we have

which is a contradiction with probability approaching one as . Analogously, if , by (A35), we have

which is also a contradiction with probability approaching one as .

For any , define the event . Then as . On the one hand, by Proposition 1,

which implies that . On the other hand, by Proposition 1,

which implies that . Since does not depend on , by letting , we have . Thus we complete the proof of Theorem 2 under Case3. □

Appendix C.2. Proof of Theorem 2 under Case4

Proof.

By Proposition 1 under Case2 and the arguments in Appendix C.1, it suffices to show

where

with , and specified in Appendix C.1. In this sequel, we will specify the upper bounds of , and , respectively.

Without loss of generality, we assume with and for some . Let . For with some sufficiently large constant , denote and . Then for some , it holds by Bonferroni inequality that

for all . Note that

By Assumptions 2(i)–(ii) and Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, . By Assumptions 2(i)–(ii) again and Theorem 1 of [32], we know that

for any . Thus, for any , we have

Due to , we can show that

Selecting for some sufficiently large constant , and , it holds by Markov’s inequality that

provided that . Due to , by Theorem 1 of [33],

for any . Thus, we can conclude that

provided that . By Bonferroni inequality and Theorem 1 of [32], we know that

for any . Then, we can conclude that provided that . Finally, Equation (1.12b) of [30] yields

which implies . Thus,

provided that . It holds that

provided that . The proof of the second result of Theorem 2 under Case4 is the same as in the proof of the second result of Theorem 2 under Case3. Thus, we complete the proof of Theorem 2. □

Appendix D. Proof of Theorem 3

Proof.

Let in Case3 and in Case4, where diverges at a sufficiently slow rate. Then provided that in Case3 and in Case4. Define an event

where and are specified in (A27) and (3), respectively. By (A34) and (A36) in Appendix C, we have

holds under Case3 and Case4 with . By Assumption 1(iii) and Assumption 2(iii), we know that holds under Case3 and Case4. Therefore,

Then it holds that under Case3 and Case4. Let . Restricted on , there exists a constant such that

By Borell inequality for Gaussian process,

for any . Let . Restricted on , we have

which implies

Since , then with probability approaching one. Hence, with probability approaching one. Similar to the proof of (A1), we know that under Case3 and Case4. By the definition of , it holds with probability approaching one that

under Case3 with and Case4 with . Let , and , then

Similar to the proof of (A1), we know that

under Case3 and Case4. If , we can conclude that as for some constant . Due to under Case3 and Case4, we have that Theorem 3 holds under Case3 and Case4. □

Appendix E. Additional Simulation Results

Table A1.

The Type error rates, expressed as percentages, were calculated by independently generated sequences and based on (M2). The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

Table A1.

The Type error rates, expressed as percentages, were calculated by independently generated sequences and based on (M2). The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

| () | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (200,220) | 0 | 50 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 6.4 | 4.5 | 3 |

| 200 | 3.3 | 0 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 3.4 | ||

| 400 | 3.7 | 0 | 5 | 4.4 | 4.1 | ||

| 800 | 3.3 | 0 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 4.2 | ||

| 0.1 | 50 | 6.2 | 12.4 | 23.4 | 18.4 | 9.8 | |

| 200 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 43.2 | 39.5 | 12.9 | ||

| 400 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 63 | 59.7 | 14.7 | ||

| 800 | 5.3 | 0 | 88.7 | 87.3 | 19.4 | ||

| 0.2 | 50 | 8.1 | 35.6 | 51.3 | 44.3 | 21.9 | |

| 200 | 7.7 | 23.5 | 87.2 | 85.5 | 37.9 | ||

| 400 | 9.2 | 16.9 | 98.5 | 98.3 | 43 | ||

| 800 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 100 | 100 | 54.5 | ||

| (400,420) | 0 | 50 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| 200 | 3.5 | 0 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 3.2 | ||

| 400 | 5 | 0 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 4.4 | ||

| 800 | 4.3 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 4.5 | ||

| 0.1 | 50 | 6.9 | 12.2 | 21.7 | 17 | 9.3 | |

| 200 | 4.9 | 1.9 | 41.7 | 39 | 11.1 | ||

| 400 | 7.8 | 0.1 | 63.6 | 61.4 | 17.7 | ||

| 800 | 7.3 | 0 | 87.9 | 86.7 | 18.3 | ||

| 0.2 | 50 | 8.6 | 33.7 | 46.9 | 40.7 | 20.6 | |

| 200 | 7.7 | 23.7 | 86.3 | 84.7 | 31 | ||

| 400 | 9.4 | 17.1 | 99.2 | 99 | 43.6 | ||

| 800 | 9 | 9.5 | 100 | 100 | 53.2 |

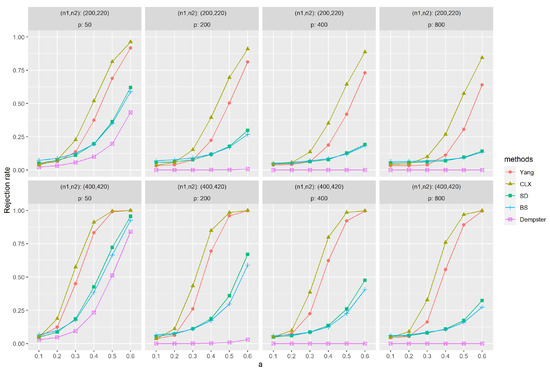

Figure A1.

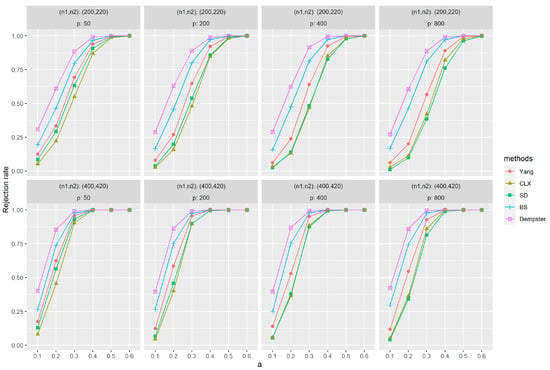

The empirical powers with sparse signals were evaluated by independently generated sequences based on (M2), and , and based on (M2), and . The parameter a represents the distance between the null and alternative hypotheses. The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

Figure A2.

The empirical powers with dense signals were evaluated by independently generated sequences based on (M2), and , and based on (M2), and . The parameter a represents the distance between the null and alternative hypotheses. The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

Table A2.

The Type error rates, expressed as percentages, were calculated by independently generated sequences and based on (M3). The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

Table A2.

The Type error rates, expressed as percentages, were calculated by independently generated sequences and based on (M3). The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

| () | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (200,220) | 0 | 50 | 5.7 | 16.8 | 7.7 | 3 | 1.6 |

| 200 | 4.3 | 14.9 | 6.9 | 0.9 | 1.6 | ||

| 400 | 3.5 | 14.7 | 7.7 | 0.2 | 1.2 | ||

| 800 | 4.2 | 15.4 | 6.9 | 0.2 | 1.7 | ||

| 0.1 | 50 | 7.9 | 25.2 | 13.7 | 5.5 | 5.4 | |

| 200 | 6.2 | 23 | 12 | 2.7 | 5 | ||

| 400 | 5.5 | 23.3 | 12.5 | 1.2 | 4.2 | ||

| 800 | 6.9 | 24 | 12.9 | 0.7 | 5.5 | ||

| 0.2 | 50 | 8.6 | 33.8 | 21 | 10.7 | 12.8 | |

| 200 | 7.5 | 32.5 | 19.7 | 5.8 | 13.9 | ||

| 400 | 6.9 | 30.4 | 20.2 | 4.4 | 15 | ||

| 800 | 9.3 | 32.3 | 20.7 | 1.7 | 18.4 | ||

| (400,420) | 0 | 50 | 5.4 | 13.9 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| 200 | 5.1 | 15.5 | 6.4 | 1 | 1.1 | ||

| 400 | 5.3 | 14.1 | 7.1 | 0.8 | 1.3 | ||

| 800 | 4 | 16.2 | 6.3 | 0.1 | 1.3 | ||

| 0.1 | 50 | 6.9 | 21.3 | 10.7 | 4.7 | 5.4 | |

| 200 | 6.6 | 23.1 | 12.5 | 2.7 | 4.9 | ||

| 400 | 7.3 | 22 | 11.4 | 1.7 | 5.9 | ||

| 800 | 6.2 | 23.8 | 12.7 | 0.6 | 5.4 | ||

| 0.2 | 50 | 8.2 | 31.8 | 18.2 | 8.6 | 11 | |

| 200 | 8.2 | 31 | 19.6 | 5.2 | 13.5 | ||

| 400 | 8.7 | 32.6 | 18.9 | 3.9 | 14.7 | ||

| 800 | 7.4 | 35.2 | 21.3 | 1.8 | 17.3 |

Figure A3.

The empirical powers with sparse signals were evaluated by independently generated sequences based on (M3), and , and based on (M3), and . The parameter a represents the distance between the null and alternative hypotheses. The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

Figure A4.

The empirical powers with dense signals were evaluated by independently generated sequences based on (M3), and , and based on (M3), and . The parameter a represents the distance between the null and alternative hypotheses. The simulations were replicated 1000 times.

References

- Hotelling, H. The generalization of student’s ratio. Ann. Math. Stat. 1931, 2, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Bai, Z. A review of 20 years of naive tests of significance for high-dimensional mean vectors and covariance matrices. Sci. China Math. 2016, 59, 2281–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harrar, S.W.; Kong, X. Recent developments in high-dimensional inference for multivariate data: Parametric, semiparametric and nonparametric approaches. J. Multivar. Anal. 2022, 188, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Saranadasa, H. Effect of high dimension: By an example of a two sample problem. Stat. Sin. 1996, 6, 311–329. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster, A.P. A high dimensional two sample significance test. Ann. Math. Stat. 1958, 29, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.S.; Du, M. A test for the mean vector with fewer observations than the dimension. J. Multivar. Anal. 2008, 99, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, K.B.; Carroll, R.J.; Baladandayuthapani, V.; Lahiri, S.N. A two-sample test for equality of means in high dimension. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2015, 110, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.T.; Liu, W.; Xia, Y. Two-sample test of high dimensional means under dependence. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2014, 76, 349–372. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhou, W.X.; Zhou, W. Simulation-Based Hypothesis Testing of High Dimensional Means Under Covariance Heterogeneity. Biometrics 2017, 73, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Lin, L.; Wei, P.; Pan, W. An adaptive two-sample test for high-dimensional means. Biometrika 2017, 103, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Kato, K. Testing Many Moment Inequalities; Cemmap working paper, No. CWP42/16; Centre for Microdata Methods and Practice (cemmap): London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, W.B. Gaussian approximation for high dimensional time series. Ann. Stat. 2017, 45, 1895–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.B. Nonlinear system theory: Another look at dependence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14150–14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Chen, X.; Wu, M. Central limit theorems for high dimensional dependent data. Bernoulli 2024, 30, 712–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raič, M. A multivariate berry–esseen theorem with explicit constants. Bernoulli 2019, 25, 2824–2853. [Google Scholar]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Kato, K.; Koike, Y. Improved central limit theorem and bootstrap approximations in high dimensions. Ann. Stat. 2022, 50, 2562–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peligrad, M. Some remarks on coupling of dependent random variables. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2002, 60, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künsch, H.R. The jackknife and the bootstrap for general stationary observations. Ann. Stat. 1989, 17, 1217–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.Y. Bootstrap procedures under some non-I.I.D. models. Ann. Stat. 1988, 16, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.B.; Li, T. A global wavelet based bootstrapped test of covariance stationarity. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.14086. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Koike, Y. High-dimensional central limit theorems by Stein’s method. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2021, 31, 1660–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Koike, Y. Nearly optimal central limit theorem and bootstrap approximations in high dimensions. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2023, 33, 2374–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; He, J.; Yang, L.; Yao, Q. Modelling matrix time series via a tensor CP-decomposition. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2023, 85, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Y. High-dimensional central limit theorems for homogeneous sums. J. Theor. Probab. 2023, 36, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörmann, S.; Kokoszka, P. Weakly dependent functional data. Ann. Stat. 2010, 38, 1845–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. White noise testing and model diagnostic checking for functional time series. J. Econ. 2016, 194, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, D.N.; Romano, J.P.; Wolf, M. Subsampling; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Kato, K. Gaussian approximations and multiplier bootstrap for maxima of sums of high-dimensional random vectors. Ann. Stat. 2013, 41, 2786–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation robust structural change detection. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2013, 108, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, E. Inequalities and Limit Theorems for Weakly Dependent Sequences, 3rd Cycle. France. 2013, p. 170. Available online: https://cel.hal.science/cel-00867106v2 (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Kato, K. Central limit theorems and bootstrap in high dimensions. Ann. Probab. 2017, 45, 2309–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlevède, F.; Peligrad, M.; Rio, E. A Bernstein type inequality and moderate deviations for weakly dependent sequences. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 2011, 151, 435–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlevède, F.; Peligrad, M.; Rio, E. Bernstein inequality and moderate deviations under strong mixing conditions. In High Dimensional Probability V: The Luminy Volume; Institute of Mathematical Statistics: Waite Hill, OH, USA, 2009; Volume 5, pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).