1. Introduction

Optimization formulations that involve information-theoretic quantities (e.g., mutual information) have been instrumental in a variety of learning problems found in machine learning. A notable example is the information bottleneck (

) method [

1]. Suppose

Y is a target variable and

X is an observable correlated variable with joint distribution

. The goal of

is to learn a “compact” summary (aka bottleneck)

T of

X that is maximally “informative” for inferring

Y. The bottleneck variable

T is assumed to be generated from

X by applying a random function

F to

X, i.e.,

, in such a way that it is conditionally independent of

Y given

X, that we denote by

The

quantifies this goal by measuring the “compactness” of

T using the mutual information

and, similarly, “informativeness” by

. For a given level of compactness

,

extracts the bottleneck variable

T that solves the constrained optimization problem

where the supremum is taken over all randomized functions

satisfying

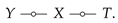

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T.

The optimization problem that underlies the information bottleneck has been studied in the information theory literature as early as the 1970’s—see [

2,

3,

4,

5]—as a technique to prove impossibility results in information theory and also to study the common information between

X and

Y. Wyner and Ziv [

2] explicitly determined the value of

for the special case of binary

X and

Y—a result widely known as Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma [

2,

6]. More than twenty years later, the information bottleneck function was studied by Tishby et al. [

1] and re-formulated in a data analytic context. Here, the random variable

X represents a high-dimensional observation with a corresponding low-dimensional feature

Y.

aims at specifying a compressed description of image which is maximally informative about feature

Y. This framework led to several applications in clustering [

7,

8,

9] and quantization [

10,

11].

A closely-related framework to

is the privacy funnel (

) problem [

12,

13,

14]. In the

framework, a bottleneck variable

T is sought to maximally preserve “information” contained in

X while revealing as little about

Y as possible. This framework aims to capture the inherent trade-off between revealing

X perfectly and leaking a sensitive attribute

Y. For instance, suppose a user wishes to share an image

X for some classification tasks. The image might carry information about attributes, say

Y, that the user might consider as sensitive, even when such information is of limited use for the tasks, e.g., location, or emotion. The

framework seeks to extract a representation of

X from which the original image can be recovered with maximal accuracy while minimizing the privacy leakage with respect to

Y. Using mutual information for both privacy leakage and informativeness, the privacy funnel can be formulated as

where the infumum is taken over all randomized function

and

r is the parameter specifying the level of informativeness. It is evident from the formulations (

2) and (

3) that

and

are closely related. In fact, we shall see later that they correspond to the upper and lower boundaries of a two-dimensional compact convex set. This duality has led to design of greedy algorithms [

12,

15] for estimating

based on the agglomerative information bottleneck [

9] algorithm. A similar formulation has recently been proposed in [

16] as a tool to train a neural network for learning a private representation of data

X; see [

17,

18] for other closely-related formulations. Solving

and

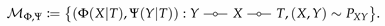

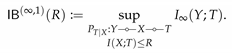

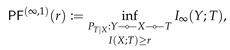

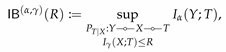

optimization problems analytically is challenging. However, recent machine learning applications, and deep learning algorithms in particular, have reignited the study of both

and

(see Related Work).

In this paper, we first give a cohesive overview of the existing results surrounding the

and the

formulations. We then provide a comprehensive analysis of

and

from an information-theoretic perspective, as well as a survey of several formulations connected to the

and

that have been introduced in the information theory and machine learning literature. Moreover, we overview connections with coding problems such as remote source-coding [

19], testing against independence [

20], and dependence dilution [

21]. Leveraging these connections, we prove a new cardinality bound for the bottleneck variable in

, leading to more tractable optimization problem for

. We then consider a broad family of optimization problems by going beyond mutual information in formulations (

2) and (

3). We propose two candidates for this task: Arimoto’s mutual information [

22] and

f-information [

23]. By replacing

and/or

with either of these measures, we generate a family of optimization problems that we referred to as the bottleneck problems. These problems are shown to better capture the underlying trade-offs intended by

and

(see also the short version [

24]). More specifically, our main contributions are listed next.

Computing

and

are notoriously challenging when

X takes values in a set with infinite cardinality (e.g.,

X is drawn from a continuous probability distribution). We consider three different scenarios to circumvent this difficulty. First, we assume that

X is a Gaussian perturbation of

Y, i.e.,

where

is a noise variable sampled from a Gaussian distribution independent of

Y. Building upon the recent advances in entropy power inequality in [

25], we derive a sharp upper bound for

. As a special case, we consider jointly Gaussian

for which the upper bound becomes tight. This then provides a significantly simpler proof for the fact that in this special case the optimal bottleneck variable

T is also Gaussian than the original proof given in [

26]. In the second scenario, we assume that

Y is a Gaussian perturbation of

X, i.e.,

. This corresponds to a practical setup where the feature

Y might be perfectly obtained from a noisy observation of

X. Relying on the recent results in strong data processing inequality [

27], we obtain an upper bound on

which is tight for small values of

R. In the last scenario, we compute second-order approximation of

under the assumption that

T is obtained by Gaussian perturbation of

X, i.e.,

. Interestingly, the rate of increase of

for small values of

r is shown to be dictated by an asymmetric measure of dependence introduced by Rényi [

28].

We extend the Witsenhausen and Wyner’s approach [

3] for analytically computing

and

. This technique converts solving the optimization problems in

and

to determining the convex and concave envelopes of a certain function, respectively. We apply this technique to binary

X and

Y and derive a closed form expression for

– we call this result Mr. Gerber’s Lemma.

Relying on the connection between

and noisy source coding [

19] (see [

29,

30]), we show that the optimal bottleneck variable

T in optimization problem (

2) takes values in a set

with cardinality

. Compared to the best cardinality bound previously known (i.e.,

), this result leads to a reduction in the search space’s dimension of the optimization problem (

2) from

to

. Moreover, we show that this does not hold for

, indicating a fundamental difference in optimizations problems (

2) and (

3).

Following [

14,

31], we study the deterministic

and

(denoted by

and

) in which

T is assumed to be a deterministic function of

X, i.e.,

for some function

f. By connecting

and

with entropy-constrained scalar quantization problems in information theory [

32], we obtain bounds on them explicitly in terms of

. Applying these bounds to

, we obtain that

is bounded by one from above and by

from below.

By replacing

and/or

in (

2) and (

3) with Arimoto’s mutual information or

f-information, we generate a family of bottleneck problems. We then argue that these new functionals better describe the trade-offs that were intended to be captured by

and

. The main reason is three-fold: First, as illustrated in

Section 2.3, mutual information in

and

are mainly justified when

independent samples

of

are considered. However, Arimoto’s mutual information allows for operational interpretation even in the single-shot regime (i.e., for

). Second,

in

and

is meant to be a proxy for the efficiency of reconstructing

Y given observation

T. However, this can be accurately formalized by probability of correctly guessing

Y given

T (i.e., Bayes risk) or minimum mean-square error (MMSE) in estimating

Y given

T. While

bounds these two measures, we show that they are precisely characterized by Arimoto’s mutual information and

f-information, respectively. Finally, when

is unknown, mutual information is known to be notoriously difficult to estimate. Nevertheless, Arimoto’s mutual information and

f-information are easier to estimate: While mutual information can be estimated with estimation error that scales as

[

33], Diaz et al. [

34] showed that this estimation error for Arimoto’s mutual information and

f-information is

.

We also generalize our computation technique that enables us to analytically compute these bottleneck problems. Similar as before, this technique converts computing bottleneck problems to determining convex and concave envelopes of certain functions. Focusing on binary X and Y, we derive closed form expressions for some of the bottleneck problems.

1.1. Related Work

The

formulation has been extensively applied in representation learning and clustering [

7,

8,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Clustering based on

results in algorithms that cluster data points in terms of the similarity of

. When data points lie in a metric space, usually geometric clustering is preferred where clustering is based upon the geometric (e.g., Euclidean) distance. Strouse and Schwab [

31,

39] proposed the deterministic

(denoted by

) by enforcing that

is a deterministic mapping:

denotes the supremum of

over all functions

satisfying

. This optimization problem is closely related to the problem of scalar quantization in information theory: designing a function

with a pre-determined output alphabet with

f optimizing some objective functions. This objective might be maximizing or minimizing

[

40] or maximizing

for a random variable

Y correlated with

X [

32,

41,

42,

43]. Since

for

, the latter problem provides lower bounds for

(and thus for

). In particular, one can exploit [

44] (Theorem 1) to obtain

provided that

. This result establishes a linear gap between

and

irrespective of

.

The connection between quantization and

further allows us to obtain multiplicative bounds. For instance, if

and

, where

is independent of

Y, then it is well-known in information theory literature that

for all non-constant

(see, e.g., [

45] (Section 2.11)), thus

for

. We further explore this connection to provide multiplicative bounds on

in

Section 2.5.

The study of

has recently gained increasing traction in the context of deep learning. By taking

T to be the activity of the hidden layer(s), Tishby and Zaslavsky [

46] (see also [

47]) argued that neural network classifiers trained with cross-entropy loss and stochastic gradient descent (SGD) inherently aims at solving the

optimization problems. In fact, it is claimed that the graph of the function

(the so-called the information plane) characterizes the learning dynamic of different layers in the network: shallow layers correspond to maximizing

while deep layers’ objective is minimizing

. While the generality of this claim was refuted empirically in [

48] and theoretically in [

49,

50], it inspired significant follow-up studies. These include (i) modifying neural network training in order to solve the

optimization problem [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]; (ii) creating connections between

and generalization error [

56], robustness [

51], and detection of out-of-distribution data [

57]; and (iii) using

to understand specific characteristic of neural networks [

55,

58,

59,

60].

In both

and

, mutual information poses some limitations. For instance, it may become infinity in deterministic neural networks [

48,

49,

50] and also may not lead to proper privacy guarantee [

61]. As suggested in [

55,

62], one way to address this issue is to replace mutual information with other statistical measures. In the privacy literature, several measures with strong privacy guarantee have been proposed including Rényi maximal correlation [

21,

63,

64], probability of correctly recovering [

65,

66], minimum mean-squared estimation error (MMSE) [

67,

68],

-information [

69] (a special case of

f-information to be described in

Section 3), Arimoto’s and Sibson’s mutual information [

61,

70]—to be discussed in

Section 3, maximal leakage [

71], and local differential privacy [

72]. All these measures ensure interpretable privacy guarantees. For instance, it is shown in [

67,

68] that if

-information between

Y and

T is sufficiently small, then no functions of

Y can be efficiently reconstructed given

T; thus providing an interpretable privacy guarantee.

Another limitation of mutual information is related to its estimation difficulty. It is known that mutual information can be estimated from

n samples with the estimation error that scales as

[

33]. However, as shown by Diaz et al. [

34], the estimation error for most of the above measures scales as

. Furthermore, the recently popular variational estimators for mutual information, typically implemented via deep learning methods [

73,

74,

75], presents some fundamental limitations [

76]: the variance of the estimator might grow exponentially with the ground truth mutual information and also the estimator might not satisfy basic properties of mutual information such as data processing inequality or additivity. McAllester and Stratos [

77] showed that some of these limitations are inherent to a large family of mutual information estimators.

1.2. Notation

We use capital letters, e.g.,

X, for random variables and calligraphic letters for their alphabets, e.g.,

. If

X is distributed according to probability mass function (pmf)

, we write

. Given two random variables

X and

Y, we write

and

as the joint distribution and the conditional distribution of

Y given

X. We also interchangeably refer to

as a channel from

X to

Y. We use

to denote both entropy and differential entropy of

X, i.e., we have

if

X is a discrete random variable taking values in

with probability mass function (pmf)

and

where

X is an absolutely continuous random variable with probability density function (pdf)

. If

X is a binary random variable with

, we write

. In this case, its entropy is called binary entropy function and denoted by

. We use superscript

to describe a standard Gaussian random variable, i.e.,

. Given two random variables

X and

Y, their (Shannon’s) mutual information is denoted by

. We let

denote the set of all probability distributions on the set

. Given an arbitrary

and a channel

, we let

denote the resulting output distribution on

. For any

, we use

to denote

and for any integer

,

.

Throughout the paper, we assume a pair of (discrete or continuous) random variables are given with a fixed joint distribution , marginals and , and conditional distribution . We then use to denote an arbitrary distribution with .

2. Information Bottleneck and Privacy Funnel: Definitions and Functional Properties

In this section, we review the information bottleneck and its closely related functional, the privacy funnel. We then prove some analytical properties of these two functionals and develop a convex analytic approach which enables us to compute closed-form expressions for both these two functionals in some simple cases.

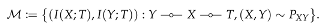

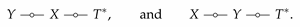

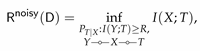

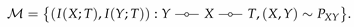

To precisely quantify the trade-off between these two conflicting goals, the

optimization problem (

2) was proposed [

1]. Since any randomized function

can be equivalently characterized by a conditional distribution, the optimization problem (

2) can be instead expressed as

where

R and

denote the level of desired compression and informativeness, respectively. We use

and

to denote

and

, respectively, when the joint distribution is clear from the context. Notice that if

, then

.

Now consider the setup where data

X is required to be disclosed while maintaining the privacy of a sensitive attribute, represented by

Y. This goal was formulated by

in (

3). As before, replacing randomized function

with conditional distribution

, we can equivalently express (

3) as

where

and

r denote the level of desired privacy and informativeness, respectively. The case

is particularly interesting in practice and specifies perfect privacy, see e.g., [

13,

78]. As before, we write

and

for

and

when

is clear from the context.

The following properties of

and

follow directly from their definitions. The proof of this result (and any other results in this section) is given in

Appendix A.

Theorem 1. For a given , the mappings and have the following properties:

.

for any and for .

for any and for any .

is continuous, strictly increasing, and concave on the range .

is continuous, strictly increasing, and convex on the range .

If for all and , then both and are continuously differentiable over .

is non-increasing and is non-decreasing.

According to this theorem, we can always restrict both

R and

r in (

4) and (

5), respectively, to

as

for all

.

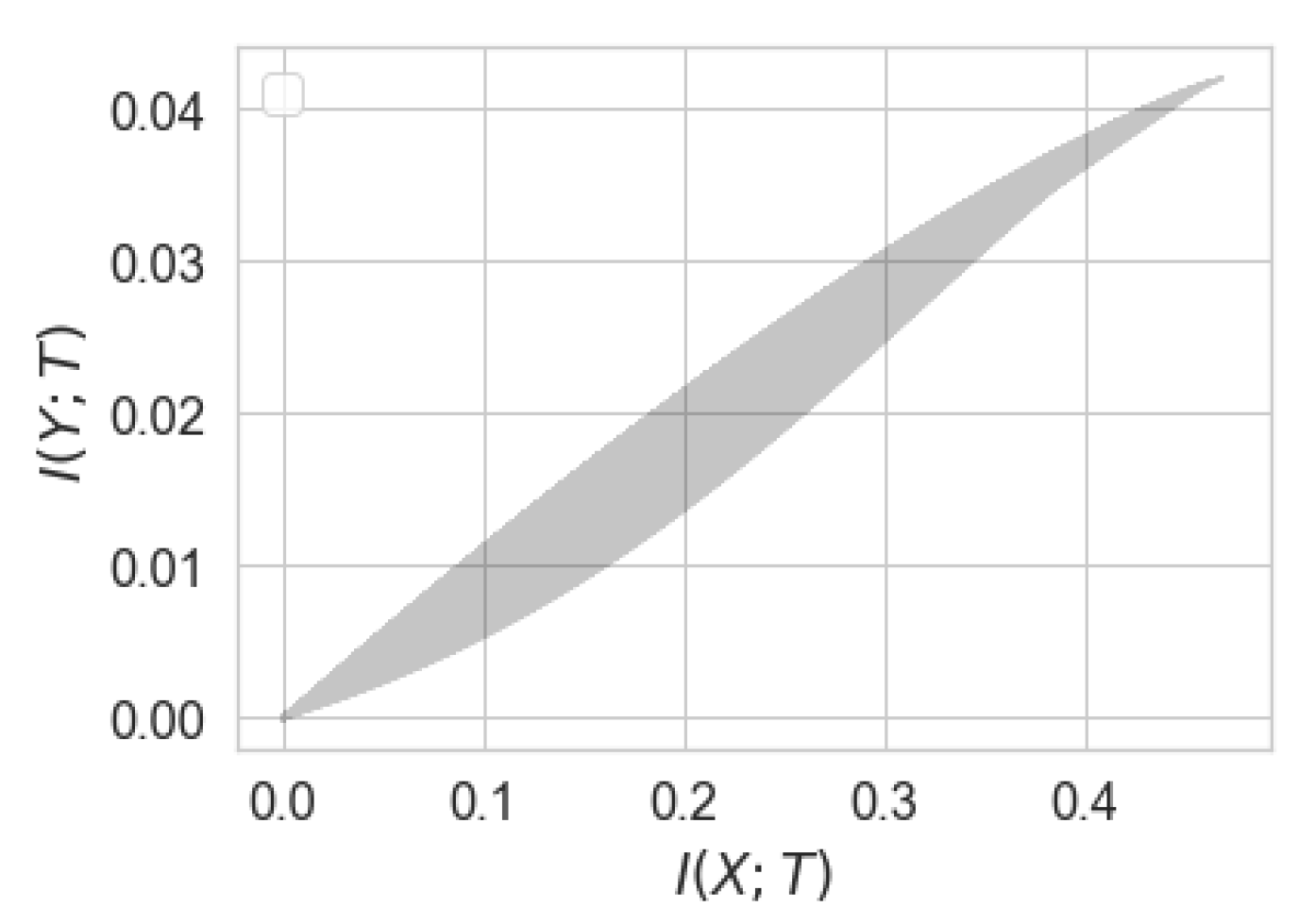

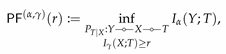

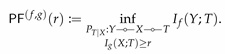

Define

as

It can be directly verified that

is convex. According to this theorem,

and

correspond to the upper and lower boundary of

, respectively. The convexity of

then implies the concavity and convexity of

and

.

Figure 1 illustrates the set

for the simple case of binary

X and

Y.

While both

and

, their behavior in the neighborhood around zero might be completely different. As illustrated in

Figure 1,

for all

, whereas

for

for some

. When such

exists, we say perfect privacy occurs: there exists a variable

T satisfying

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T such that

while

; making

T a representation of

X having perfect privacy (i.e., no information leakage about

Y). A necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of such

T is given in [

21] (Lemma 10) and [

13] (Theorem 3), described next.

Theorem 2 (Perfect privacy). Let be given and be the set of vectors . Then there exists such that for if and only if vectors in are linearly independent.

In light of this theorem, we obtain that perfect privacy occurs if

. It also follows from the theorem that for binary

X, perfect privacy cannot occur (see

Figure 1a).

Theorem 1 enables us to derive a simple bounds for and . Specifically, the facts that is non-decreasing and is non-increasing immediately result in the the following linear bounds.

Theorem 3 (Linear lower bound)

. For , we have In light of this theorem, if

, then

, implying

for a deterministic function

g. Conversely, if

then

because for all

T forming the Markov relation

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() g

g(

Y)

![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T, we have

. On the other hand, we have

if and only if there exists a variable

satisfying

and thus the following double Markov relations

It can be verified (see [

79] (Problem 16.25)) that this double Markov condition is equivalent to the existence of a pair of functions

f and

g such that

and (

X,Y)

![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() f

f(

X)

![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]()

. One special case of this setting, namely where

g is an identity function, has been recently studied in details in [

53] and will be reviewed in

Section 2.5. Theorem 3 also enables us to characterize the “worst” joint distribution

with respect to

and

. As demonstrated in the following lemma, if

is an erasure channel then

.

Lemma 1. Let be such that , , and for some . Then Let be such that , , and for some . Then

The bounds in Theorem 3 hold for all r and R in the interval . We can, however, improve them when r and R are sufficiently small. Let and denote the slope of and at zero, i.e., and .

Theorem 4. Given , we have This theorem provides the exact values of

and

and also simple bounds for them. While the exact expressions for

and

are usually difficult to compute, a simple plug-in estimator is proposed in [

80] for

. This estimator can be readily adapted to estimate

. Theorem 4 reveals a profound connection between

and the strong data processing inequality (SDPI) [

81]. More precisely, thanks to the pioneering work of Anantharam et al. [

82], it is known that the supremum of

over all

is equal the supremum of

over all

satisfying

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T and hence

specifies the strengthening of the data processing inequality of mutual information. This connection may open a new avenue for new theoretical results for

, especially when

X or

Y are continuous random variables. In particular, the recent non-multiplicative SDPI results [

27,

83] seem insightful for this purpose.

In many practical cases, we might have

n i.i.d. samples

of

. We now study how

behaves in

n. Let

and

. Due to the i.i.d. assumption, we have

. This can also be described by independently feeding

,

, to channel

producing

. The following theorem, demonstrated first in [

3] (Theorem 2.4), gives a formula for

in terms of

n.

This theorem demonstrates that an optimal channel

for i.i.d. samples

is obtained by the Kronecker product of an optimal channel

for

. This, however, may not hold in general for

, that is, we might have

, see [

13] (Proposition 1) for an example.

2.1. Gaussian and

In this section, we turn our attention to a special, yet important, case where

, where

and

is independent of

Y. This setting subsumes the popular case of jointly Gaussian

whose information bottleneck functional was computed in [

84] for the vector case (i.e.,

are jointly Gaussian random vectors).

Lemma 2. Let be n i.i.d. copies of and where are i.i.d samples of independent of Y. Then, we have It is worth noting that this result was concurrently proved in [

85]. The main technical tool in the proof of this lemma is a strong version of the entropy power inequality [

25] (Theorem 2) which holds even if

,

, and

are random vectors (as opposed to scalar). Thus, one can readily generalize Lemma 2 to the vector case. Note that the upper bound established in this lemma holds without any assumptions on

. This upper bound provides a significantly simpler proof for the well-known fact that for the jointly Gaussian

, the optimal channel

is Gaussian. This result was first proved in [

26] and used in [

84] to compute an expression of

for the Gaussian case.

Corollary 1. If are jointly Gaussian with correlation coefficient ρ, then we haveMoreover, the optimal channel is given by for where is the variance of Y. In Lemma 2, we assumed that

X is a Gaussian perturbation of

Y. However, in some practical scenarios, we might have

Y as a Gaussian perturbation of

X. For instance, let

X represent an image and

Y be a feature of the image that can be perfectly obtained from a noisy observation of

X. Then, the goal is to compress the image with a given compression rate while retaining maximal information about the feature. The following lemma, which is an immediate consequence of [

27] (Theorem 1), gives an upper bound for

in this case.

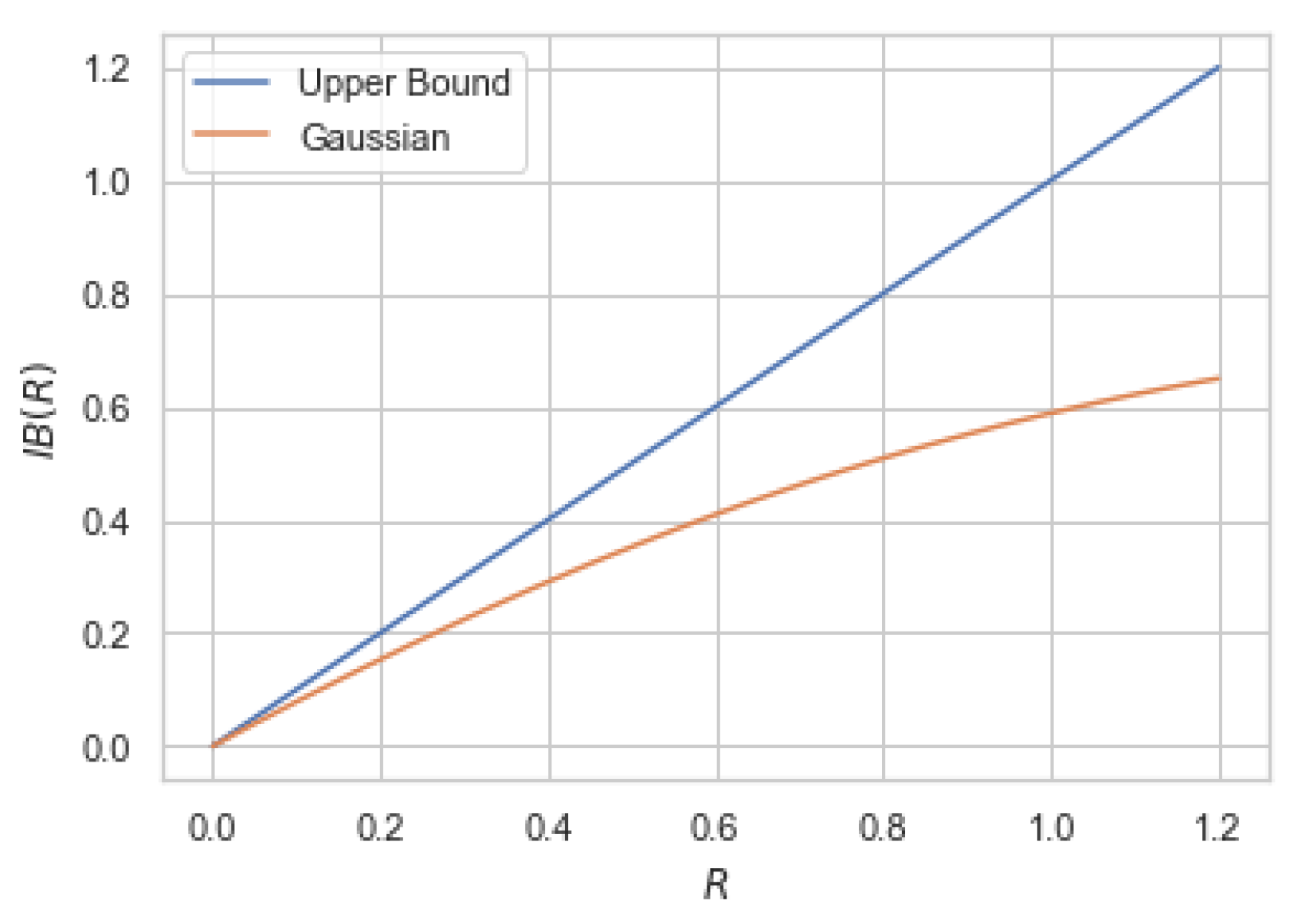

Lemma 3. Let be n i.i.d. copies of a random variable X satisfying and be the result of passing , , through a Gaussian channel , where and is independent of X. Then, we havewhere is the Gaussian complimentary CDF and for is the binary entropy function. Moreover, we have Note that that Lemma 3 holds for any arbitrary

X (provided that

) and hence (

9) bounds information bottleneck functionals for a wide family of

. However, the bound is loose in general for large values of

R. For instance, if

are jointly Gaussian (implying

for some

), then the right-hand side of (

9) does not reduce to (

8). To show this, we numerically compute the upper bound (

9) and compare it with the Gaussian information bottleneck (

8) in

Figure 2.

The privacy funnel functional is much less studied even for the simple case of jointly Gaussian. Solving the optimization in

over

without any assumptions is a difficult challenge. A natural assumption to make is that

is Gaussian for each

. This leads to the following variant of

where

and

is independent of

X. This formulation is tractable and can be computed in closed form for jointly Gaussian

as described in the following example.

Example 1. Let X and Y be jointly Gaussian with correlation coefficient ρ. First note that since mutual information is invariant to scaling, we may assume without loss of generality that both X and Y are zero mean and unit variance and hence we can write where is independent of Y. Consequently, we haveandIn order to ensure , we must have . Plugging this choice of σ into (13), we obtain This example indicates that for jointly Gaussian

, we have

if and only if

(thus perfect privacy does not occur) and the constraint

is satisfied by a unique

. These two properties in fact hold for all continuous variables

X and

Y with finite second moments as demonstrated in Lemma A1 in

Appendix A. We use these properties to derive a second-order approximation of

when

r is sufficiently small. For the following theorem, we use

to denote the variance of the random variable

U and

. We use

for short.

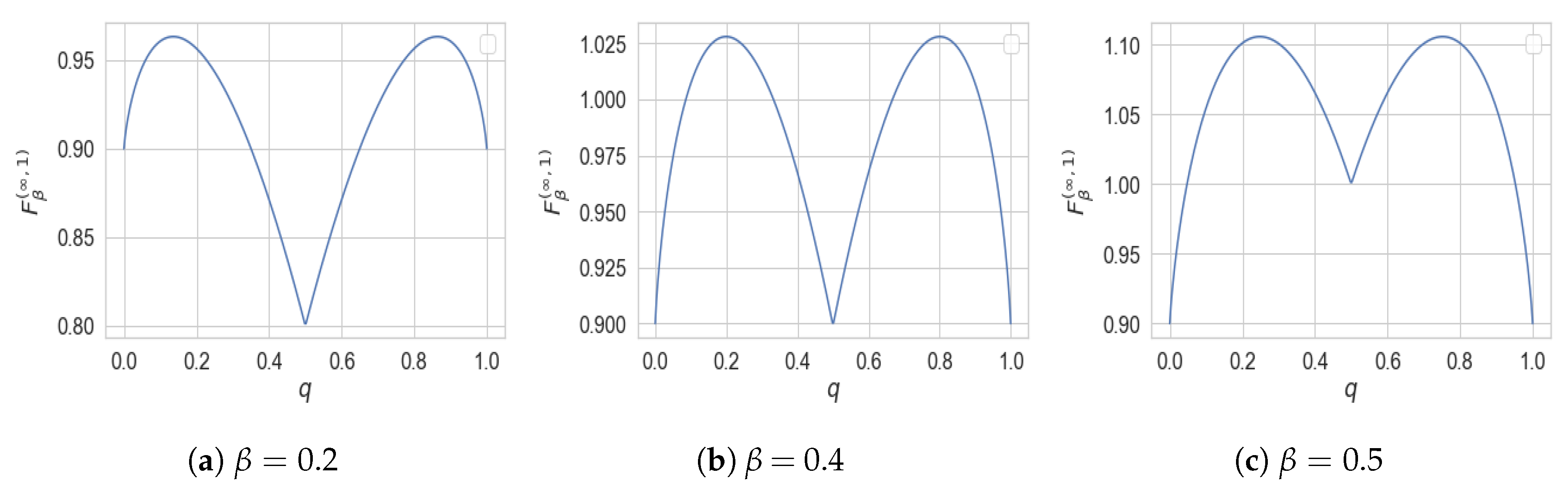

Theorem 6. For any pair of continuous random variables with finite second moments, we have as where and It is worth mentioning that the quantity

was first defined by Rényi [

28] as an asymmetric measure of correlation between

X and

Y. In fact, it can be shown that

where supremum is taken over all measurable functions

f and

denotes the correlation coefficient. As a simple illustration of Theorem 6, consider jointly Gaussian

X and

Y with correlation coefficient

for which

was computed in Example 1. In this case, it can be easily verified that

and

. Hence, for jointly Gaussian

with correlation coefficient

and unit variance, we have

. In

Figure 3, we compare the approximation given in Theorem 6 for this particular case.

2.2. Evaluation of and

The constrained optimization problems in the definitions of

and

are usually challenging to solve numerically due to the non-linearity in the constraints. In practice, however, both

and

are often approximated by their corresponding Lagrangian optimizations

and

where

is the Lagrangian multiplier that controls the tradeoff between compression and informativeness in for

and the privacy and informativeness in

. Notice that for the computation of

, we can assume, without loss of generality, that

since otherwise the maximizer of (

15) is trivial. It is worth noting that

and

in fact correspond to lines of slope

supporting

from above and below, thereby providing a new representation of

.

Let

be a pair of random variables with

for some

and

is the output of

when the input is

(i.e.,

). Define

This function, in general, is neither convex nor concave in

. For instance,

is concave and

is convex in

. The lower convex envelope of

is defined as the largest convex function smaller than

. Similarly, the upper concave envelope of

is defined as the smallest concave function larger than

. Let

and

denote the lower convex and upper concave envelopes of

, respectively. If

is convex at

, that is

, then

remains convex at

for all

because

where the last equality follows from the fact that

is convex. Hence, at

we have

Analogously, if

is concave at

, that is

, then

remains concave at

for all

.

Notice that, according to (

15) and (

16), we can write

and

In light of the above arguments, we can write

for all

where

is the smallest

such that

touches

. Similarly,

for all

where

is the largest

such that

touches

. In the following theorem, we show that

and

are given by the values of

and

, respectively, given in Theorem 4. A similar formulae

and

were given in [

86].

Kim et al. [

80] have recently proposed an efficient algorithm to estimate

from samples of

involving a simple optimization problem. This algorithm can be readily adapted for estimating

. Proposition 1 implies that in optimizing the Lagrangians (

17) and (

18), we can restrict the Lagrange multiplier

, that is

and

Remark 1. As demonstrated by Kolchinsky et al. [53], the boundary points 0 and are required for the computation of . In fact, when Y is a deterministic function of X, then only

and are required to compute the and other values of β are vacuous. The same argument can also be used to justify the inclusion of in computing . Note also that since becomes convex for , computing becomes trivial for such values of β. Remark 2. Observe that the lower convex envelope of any function f can be obtained by taking Legendre-Fenchel transformation (aka. convex conjugate) twice. Hence, one can use the existing linear-time algorithms for approximating Legendre-Fenchel transformation (e.g., [87,88]) for approximating . Once

and

are computed, we can derive

and

via standard results in optimization (see [

3] (Section IV) for more details):

and

Following the convex analysis approach outlined by Witsenhausen and Wyner [

3],

and

can be directly computed from

and

by observing the following. Suppose for some

,

(resp.

) at

is obtained by a convex combination of points

,

for some

in

, integer

, and weights

(with

). Then

, and

with properties

and

attains the minimum (resp. maximum) of

. Hence,

is a point on the upper (resp. lower) boundary of

; implying that

for

(resp.

for

). If for some

,

at

coincides with

, then this corresponds to

. The same holds for

. Thus, all the information about the functional

(resp.

) is contained in the subset of the domain of

(resp.

) over which it differs from

. We will revisit and generalize this approach later in

Section 3.

We can now instantiate this for the binary symmetric case. Suppose

X and

Y are binary variables and

is binary symmetric channel with crossover probability

, denoted by

and defined as

for some

. To describe the result in a compact fashion, we introduce the following notation: we let

denote the binary entropy function, i.e.,

. Since this function is strictly increasing

, its inverse exists and is denoted by

. Moreover,

for

.

Lemma 4 (Mr. and Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma)

. For for and for , we haveandwhere , , and . The result in (

24) was proved by Wyner and Ziv [

2] and is widely known as Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma in information theory. Due to the similarity, we refer to (

25) as Mr. Gerber’s Lemma. As described above, to prove (

24) and (

25) it suffices to derive the convex and concave envelopes of the mapping

given by

where

is the output distribution of

when the input distribution is

for some

. It can be verified that

. This function is depicted in

Figure 4 depending of the values of

.

2.3. Operational Meaning of and

In this section, we illustrate several information-theoretic settings which shed light on the operational interpretation of both

and

. The operational interpretation of

has recently been extensively studied in information-theoretic settings in [

29,

30]. In particular, it was shown that

specifies the rate-distortion region of noisy source coding problem [

19,

89] under the logarithmic loss as the distortion measure and also the rate region of the lossless source coding with side information at the decoder [

90]. Here, we state the former setting (as it will be useful for our subsequent analysis of cardinality bound) and also provide a new information-theoretic setting in which

appears as the solution. Then, we describe another setting, the so-called dependence dilution, whose achievable rate region has an extreme point specified by

. This in fact delineate an important difference between

and

: while

describes the entire rate-region of an information-theoretic setup,

specifies only a corner point of a rate region. Other information-theoretic settings related to

and

include CEO problem [

91] and source coding for the Gray-Wyner network [

92].

2.3.1. Noisy Source Coding

Suppose Alice has access only to a noisy version

X of a source of interest

Y. She wishes to transmit a rate-constrained description from her observation (i.e.,

X) to Bob such that he can recover

Y with small average distortion. More precisely, let

be

n i.i.d. samples of

. Alice encodes her observation

through an encoder

and sends

to Bob. Upon receiving

, Bob reconstructs a “soft” estimate of

via a decoder

where

. That is, the reproduction sequence

consists of

n probability measures on

. For any source and reproduction sequences

and

, respectively, the distortion is defined as

where

We say that a pair of rate-distortion

is achievable if there exists a pair

of encoder and decoder such that

The noisy rate-distortion function

for a given

, is defined as the minimum rate

such that

is an achievable rate-distortion pair. This problem arises naturally in many data analytic problems. Some examples include feature selection of a high-dimensional dataset, clustering, and matrix completion. This problem was first studied by Dobrushin and Tsybakov [

19], who showed that

is analogous to the classical rate-distortion function

It can be easily verified that

and hence (after relabeling

as

T)

where

, which is equal to

defined in (

4). For more details in connection between noisy source coding and

, the reader is referred to [

29,

30,

91,

93]. Notice that one can study an essentially identical problem where the distortion constraint (

28) is replaced by

This problem is addressed in [

94] for discrete alphabets

and

and extended recently in [

95] for any general alphabets.

2.3.2. Test against Independence with Communication Constraint

As mentioned earlier, the connection between

and noisy source coding, described above, was known and studied in [

29,

30]. Here, we provide a new information-theoretic setting which provides yet another operational meaning for

. Given

n i.i.d. samples

from joint distribution

Q, we wish to test whether

are independent of

, that is,

Q is a product distribution. This task is formulated by the following hypothesis test:

for a given joint distribution

with marginals

and

. Ahlswede and Csiszár [

20] investigated this problem under a communication constraint: While

Y observations (i.e.,

) are available, the

X observations need to be compressed at rate

R, that is, instead of

, only

is present where

satisfies

For the type I error probability not exceeding a fixed

, Ahlswede and Csiszár [

20] derived the smallest possible type 2 error probability, defined as

The following gives the asymptotic expression of

for every

. For the proof, refer to [

20] (Theorem 3).

Theorem 7 ([

20])

. For every and , we have In light of this theorem,

specifies the exponential rate at which the type II error probability of the hypothesis test (

31) decays as the number of samples increases.

2.3.3. Dependence Dilution

Inspired by the problems of information amplification [

96] and state masking [

97], Asoodeh et al. [

21] proposed the dependence dilution setup as follows. Consider a source sequences

of

n i.i.d. copies of

. Alice observes the source

and wishes to encode it via the encoder

for some

. The goal is to ensure that any user observing

can construct a list, of fixed size, of sequences in

that contains likely candidates of the actual sequence

while revealing negligible information about a correlated source

. To formulate this goal, consider the decoder

where

denotes the power set of

. A

dependence dilution triple is said to be achievable if, for any

, there exists a pair of encoder and decoder

such that for sufficiently large

n

having fixed size

where

and simultaneously

Notice that without side information

J, the decoder can only construct a list of size

which contains

with probability close to one. However, after

J is observed and the list

is formed, the decoder’s list size can be reduced to

and thus reducing the uncertainty about

by

. This observation can be formalized to show (see [

96] for details) that the constraint (

32) is equivalent to

which lower bounds the amount of information

J carries about

. Built on this equivalent formulation, Asoodeh et al. [

21] (Corollary 15) derived a necessary condition for the achievable dependence dilution triple.

Theorem 8 ([

21])

. Any achievable dependence dilution triple satisfiesfor some auxiliary random variable T satisfying Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T and taking values.

T and taking values. According to this theorem, specifies the best privacy performance of the dependence dilution setup for the maximum amplification rate . While this informs the operational interpretation of , Theorem 8 only provides an outer bound for the set of achievable dependence dilution triple . It is, however, not clear that characterizes the rate region of an information-theoretic setup.

The fact that fully characterizes the rate-region of an source coding setup has an important consequence: the cardinality of the auxiliary random variable T in can be improved to instead of .

2.4. Cardinality Bound

Recall that in the definition of

in (

4), no assumption was imposed on the auxiliary random variable

T. A straightforward application of Carathéodory-Fenchel-Eggleston theorem (see e.g., [

98] (Section III) or [

79] (Lemma 15.4)) reveals that

is attained for

T taking values in a set

with cardinality

. Here, we improve this bound and show

is sufficient.

Theorem 9. For any joint distribution and , information bottleneck is achieved by T taking at most values.

The proof of this theorem hinges on the operational characterization of

as the lower boundary of the rate-distortion region of noisy source coding problem discussed in

Section 2.3. Specifically, we first show that the extreme points of this region is achieved by

T taking

values. We then make use of a property of the noisy source coding problem (namely, time-sharing) to argue that all points of this region (including the boundary points) can be attained by such

T. It must be mentioned that this result was already claimed by Harremoës and Tishby in [

99] without proof.

In many practical scenarios, feature

X has a large alphabet. Hence, the bound

, albeit optimal, still can make the information bottleneck function computationally intractable over large alphabets. However, label

Y usually has a significantly smaller alphabet. While it is in general impossible to have a cardinality bound for

T in terms of

, one can consider approximating

assuming

T takes

N values. The following result, recently proved by Hirche and Winter [

100], is in this spirit.

Theorem 10 ([

100])

. For any , we havewhere and denotes the information bottleneck functional (4) with the additional constraint that . Recall that, unlike

, the graph of

characterizes the rate region of a Shannon-theoretic coding problem (as illustrated in

Section 2.3), and hence any boundary points can be constructed via time-sharing of extreme points of the rate region. This lack of operational characterization of

translates into a worse cardinality bound than that of

. In fact, for

the cardinality bound

cannot be improved in general. To demonstrate this, we numerically solve the optimization in

assuming that

when both

X and

Y are binary. As illustrated in

Figure 5, this optimization does not lead to a convex function, and hence, cannot be equal to

.

2.5. Deterministic Information Bottleneck

As mentioned earlier,

formalizes an information-theoretic approach to clustering high-dimensional feature

X into cluster labels

T that preserve as much information about the label

Y as possible. The clustering label is assigned by the soft operator

that solves the

formulation (

4) according to the rule:

is likely assigned label

if

is small where

. That is, clustering is assigned based on the similarity of conditional distributions. As in many practical scenarios, a hard clustering operator is preferred, Strouse and Schwab [

31] suggested the following variant of

, termed as deterministic information bottleneck

where the maximization is taken over all deterministic functions

f whose range is a finite set

. Similarly, one can define

One way to ensure that

for a deterministic function

f is to restrict the cardinality of the range of

f: if

then

is necessarily smaller than

R. Using this insight, we derive a lower for

in the following lemma.

Lemma 5. For any given , we haveand Note that both

R and

r are smaller than

and thus the multiplicative factors of

in the lemma are smaller than one. In light of this lemma, we can obtain

and

In most of practical setups,

might be very large, making the above lower bound for

vacuous. In the following lemma, we partially address this issue by deriving a bound independent of

when

Y is binary.

Lemma 6. Let be a joint distribution of arbitrary X and binary for some . Then, for any we havewhere . 3. Family of Bottleneck Problems

In this section, we introduce a family of bottleneck problems by extending

and

to a large family of statistical measures. Similar to

and

, these bottleneck problems are defined in terms of boundaries of a two-dimensional convex set induced by a joint distribution

. Recall that

and

are the upper and lower boundary of the set

defined in (

6) and expressed here again for convenience

Since

is given,

and

are fixed. Thus, in characterizing

it is sufficient to consider only

and

. To generalize

and

, we must therefore generalize

and

.

Given a joint distribution

and two non-negative real-valued functions

and

, we define

and

When

and

, we interchangeably write

for

and

for

.

These definitions provide natural generalizations for Shannon’s entropy and mutual information. Moreover, as we discuss later in

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3, it also can be specialized to represent a large family of popular information-theoretic and statistical measures. Examples include information and estimation theoretic quantities such as Arimoto’s conditional entropy of order

for

, probability of correctly guessing for

, maximal correlation for binary case, and

f-information for

given by

f-divergence. We are able to generate a family of bottleneck problems using different instantiations of

and

in place of mutual information in

and

. As we argue later, these problems better capture the essence of “informativeness” and “privacy”; thus providing analytical and interpretable guarantees similar in spirit to

and

.

Computing these bottleneck problems in general boils down to the following optimization problems

and

Consider the set

Note that if both

and

are continuous (with respect to the total variation distance), then

is compact. Moreover, it can be easily verified that

is convex. Hence, its upper and lower boundaries are well-defined and are characterized by the graphs of

and

, respectively. As mentioned earlier, these functional are instrumental for computing the general bottleneck problem later. Hence, before we delve into the examples of bottleneck problems, we extend the approach given in

Section 2.2 to compute

and

.

3.1. Evaluation of and

Analogous to

Section 2.2, we first introduce the Lagrangians of

and

as

and

where

is the Lagrange multiplier, respectively. Let

be a pair of random variable with

and

is the result of passing

through the channel

. Letting

we obtain that

recalling that

and

are the upper concave and lower convex envelop operators. Once we compute

and

for all

, we can use the standard results in optimizations theory (similar to (

21) and (

22)) to recover

and

. However, we can instead extend the approach Witsenhausen and Wyner [

3] described in

Section 2.2. Suppose for some

,

(resp.

) at

is obtained by a convex combination of points

,

for some

in

, integer

, and weights

(with

). Then

, and

with properties

and

attains the maximum (resp. minimum) of

, implying that

is a point on the upper (resp. lower) boundary of

. Consequently, such

satisfies

for

(resp.

for

). The algorithm to compute

and

is then summarized in the following three steps:

Construct the functional for and and all and .

Compute and evaluated at .

If for distributions in for some , we have or for some satisfying , then then , and give the optimal in and , respectively.

We will apply this approach to analytically compute and (and the corresponding bottleneck problems) for binary cases in the following sections.

3.2. Guessing Bottleneck Problems

Let

be given with marginals

and

and the corresponding channel

. Let also

be an arbitrary distribution on

and

be the output distribution of

when fed with

. Any channel

, together with the Markov structure

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T, generates unique

and

. We need the following basic definition from statistics.

Definition 1. Let U be a discrete and V be an arbitrary random variables supported on and with , respectively. Then the probability of correctly guessing U and the probability of correctly guessing U given V are given byandMoreover, the multiplicative gain of the observation V in guessing U is defined as (the reason for ∞ in the notation becomes clear later) As the names suggest, and characterize the optimal efficiency of guessing U with or without the observation V, respectively. Intuitively, quantifies how useful the observation V is in estimating U: If it is small, then it means it is nearly as hard for an adversary observing V to guess U as it is without V. This observation motivates the use of as a measure of privacy in lieu of in .

It is worth noting that

is not symmetric in general, i.e.,

. Since observing

T can only improve, we have

; thus

. However,

does not necessarily imply independent of

Y and

T; instead, it means

T is useless in estimating

Y. As an example, consider

and

and

with

. Then

and

Thus, if

, then

. This then implies that

whereas

Y and

T are clearly dependent; i.e.,

. While in general

and

are not related, it can be shown that

if

Y is uniform (see [

65] (Proposition 1)). Hence, only with this uniformity assumption,

implies the independence.

Consider

and

. Clearly, we have

. Note that

thus both measures

and

are special cases of the models described in the previous section. In particular, we can define the corresponding

and

. We will see later that

and

correspond to Arimoto’s mutual information of orders 1 and

∞, respectively. Define

This bottleneck functional formulated an interpretable guarantee:

Recall that the functional

aims at extracting maximum information of

X while protecting privacy with respect to

Y. Measuring the privacy in terms of

, this objective can be better formulated by

with the interpretable privacy guarantee:

Notice that the variable

T in the formulations of

and

takes values in a set

of arbitrary cardinality. However, a straightforward application of the Carathéodory-Fenchel-Eggleston theorem (see e.g., [

79] (Lemma 15.4)) reveals that the cardinality of

can be restricted to

without loss of generality. In the following lemma, we prove more basic properties of

and

.

Lemma 7. For any with Y supported on a finite set , we have

.

for any and for .

is strictly increasing and concave on the range .

is strictly increasing, and convex on the range .

The proof follows the same lines as Theorem 1 and hence omitted. Lemma 7 in particular implies that inequalities

and

in the definition of

and

can be replaced by

and

, respectively. It can be verified that

satisfies the data-processing inequality, i.e.,

for the Markov chain

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T. Hence, both

and

must be smaller than

. The properties listed in Lemma 7 enable us to derive a slightly tighter upper bound for

as demonstrated in the following.

Lemma 8. For any with Y supported on a finite set , we haveand The proof of this lemma (and any other results in this section) is given in

Appendix B. This lemma shows that the gap between

and

when

R is sufficiently close to

behaves like

Thus,

approaches

as

at least linearly.

In the following theorem, we apply the technique delineated in

Section 3.1 to derive closed form expressions for

and

for the binary symmetric case, thereby establishing similar results as Mr and Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma.

Theorem 11. For and with , we haveandwhere . As described in

Section 3.1, to compute

and

it suffices to derive the convex and concave envelopes of the mapping

where

and

is the result of passing

through

, i.e.,

. In this case,

and

can be expressed as

This function is depicted in

Figure 6.

The detailed derivation of convex and concave envelope of

is given in

Appendix B. The proof of this theorem also reveals the following intuitive statements. If

and

, then among all random variables

T satisfying

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T and

, the minimum

is given by

. Notice that, without any information constraint (i.e.,

),

. Perhaps surprisingly, this shows that the mutual information constraint has a linear effect on the privacy of

Y. Similarly, to prove (

51), we show that among all

R-bit representations

T of

X, the best achievable accuracy

is given by

. This can be proved by combining Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma (cf. Lemma 4) and Fano’s inequality as follows. For all

T such that

, the minimum of

is given by

. Since by Fano’s inequality,

, we obtain

which leads to the same result as above. Nevertheless, in

Appendix B we give another proof based on the discussion of

Section 3.1.

3.3. Arimoto Bottleneck Problems

The bottleneck framework proposed in the last section benefited from interpretable guarantees brought forth by the quantity . In this section, we define a parametric family of statistical quantities, the so-called Arimoto’s mutual information, which includes both Shannon’s mutual information and as extreme cases.

Definition 2 ([

22])

. Let and be two random variables supported over finite sets and , respectively. Their Arimoto’s mutual information of order is defined aswhereis the Rényi entropy of order α andis the Arimoto’s conditional entropy of order α. By continuous extension, one can define

for

and

as

and

, respectively. That is,

Arimoto’s mutual information was first introduced by Arimoto [

22] and then later revisited by Liese and Vajda in [

101] and more recently by Verdú in [

102]. More in-depth analysis and properties of

can be found in [

103]. It is shown in [

71] (Lemma 1) that

for

quantifies the minimum loss in recovering

U given

V where the loss is measured in terms of the so-called

-loss. This loss function reduces to logarithmic loss (

27) and

for

and

, respectively. This sheds light on the utility and/or privacy guarantee promised by a constraint on Arimoto’s mutual information. It is now natural to use

for defining a family of bottleneck problems.

Definition 3. Given a pair of random variables over finite sets and and , we define and asand Of course,

and

. It is known that Arimoto’s mutual information satisfies the data-processing inequality [

103] (Corollary 1), i.e.,

for the Markov chain

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T. On the other hand,

. Thus, both

and

equal

for

. Note also that

where

(see (

39)) corresponding to the function

. Consequently,

and

are characterized by the lower and upper boundary of

, defined in (

37), with respect to

and

. Specifically, we have

where

, and

where

and

and

. This paves the way to apply the technique described in

Section 2.2 to compute

and

. Doing so requires the upper concave and lower convex envelope of the mapping

for some

, where

. In the following theorem, we drive these envelopes and give closed form expressions for

and

for a special case where

.

Theorem 12. Let and with . We have for where for and solvesMoreover,where and solves By letting

, this theorem indicates that for

X and

Y connected through

and all variables

T forming

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T, we have

which can be shown to be achieved

generated by the following channel (see

Figure 7)

Note that, by assumption,

, and hence the event

is less likely than

. Therefore, (

61) demonstrates that to ensure correct recoverability of

X with probability at lest

, the most private approach (with respect to

Y) is to obfuscate the higher-likely event

with probability

. As demonstrated in (

61) the optimal privacy guarantee is linear in the utility parameter in the binary symmetric case. This is in fact a special case of the larger result recently proved in [

65] (Theorem 1): the infimum of

over all variables

T such that

is piece-wise linear in

, on equivalently, the mapping

is piece-wise linear.

Computing analytically for every seems to be challenging, however, the following lemma provides bounds for and in terms of and , respectively.

Lemma 9. For any pair of random variables over finite alphabets and , we haveandwhere and . The previous lemma can be directly applied to derive upper and lower bounds for and given and .

3.4. f-Bottleneck Problems

In this section, we describe another instantiation of the general framework introduced in terms of functions and that enjoys interpretable estimation-theoretic guarantee.

Definition 4. Let be a convex function with . Furthermore, let U and V be two real-valued random variables supported over and , respectively. Their f-information is defined bywhere is the f-divergence [104] between distributions and defined as Due to convexity of

f, we have

and hence

f-information is always non-negative. If, furthermore,

f is strictly convex at 1, then equality holds if and only

. Csiszár introduced

f-divergence in [

104] and applied it to several problems in statistics and information theory. More recent developments about the properties of

f-divergence and

f-information can be found in [

23] and the references therein. Any convex function

f with the property

results in an

f-information. Popular examples include

corresponding to Shannon’s mutual information,

corresponding to

T-information [

83], and also

corresponding to

-information [

69] for. It is worth mentioning that if we allow

to be in

in Definition 2 (similar to [

101]), then the resulting Arimoto’s mutual information can be shown to be an

f-information in the binary case for a certain function

f, see [

101] (Theorem 8).

Let

be given with marginals

and

. Consider functions

and

on

and

defined as

Given a conditional distribution

, it is easy to verify that

and

. This in turn implies that

f-information can be utilized in (

40) and (

41) to define general bottleneck: Let

and

be two convex functions satisfying

. Then we define

and

In light of the discussion in

Section 3.1, the optimization problems in

and

can be analytically solved by determining the upper concave and lower convex envelope of the mapping

where

is the Lagrange multiplier and

.

Consider the function

with

. The corresponding

f-divergence is sometimes called Hellinger divergence of order

, see e.g., [

105]. Note that Hellinger divergence of order 2 reduces to

-divergence. Calmon et al. [

68] and Asoodeh et al. [

67] showed that if

for some

, then the minimum mean-squared error (MMSE) of reconstructing any zero-mean unit-variance function of

Y given

T is lower bounded by

, i.e., no function of

Y can be reconstructed with small MMSE given an observation of

T. This result serves a natural justification for

as an operational measure of both privacy and utility in a bottleneck problem.

Unfortunately, our approach described in

Section 3.1 cannot be used to compute

or

in the binary symmetric case. The difficulty lies in the fact that the function

, defined in (

66), for the binary symmetric case is either convex or concave on its entire domain depending on the value of

. Nevertheless, one can consider Hellinger divergence of order

with

and then apply our approach to compute

or

. Since

(see [

106] (Corollary 5.6)), one can justify

as a measure of privacy and utility in a similar way as

.

We end this section by a remark about estimating the measures studied in this section. While we consider information-theoretic regime where the underlying distribution

is known, in practice only samples

are given. Consequently, the de facto guarantees of bottleneck problems might be considerably different from those shown in this work. It is therefore essential to asses the guarantees of bottleneck problems when accessing only samples. To do so, one must derive bounds on the discrepancy between

,

, and

computed on the empirical distribution and the true (unknown) distribution. These bounds can then be used to shed light on the de facto guarantee of the bottleneck problems. Relying on [

34] (Theorem 1), one can obtain that the gaps between the measures

,

, and

computed on empirical distributions and the true one scale as

where

n is the number of samples. This is in contrast with mutual information for which the similar upper bound scales as

as shown in [

33]. Therefore, the above measures appear to be easier to estimate than mutual information.

4. Summary and Concluding Remarks

Following the recent surge in the use of information bottleneck (

) and privacy funnel (

) in developing and analyzing machine learning models, we investigated the functional properties of these two optimization problems. Specifically, we showed that

and

correspond to the upper and lower boundary of a two-dimensional convex set

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T} where

represents the observable data

X and target feature

Y and the auxiliary random variable

T varies over all possible choices satisfying the Markov relation

Y ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() X

X ![Entropy 22 01325 i001 Entropy 22 01325 i001]() T

T. This unifying perspective on

and

allowed us to adapt the classical technique of Witsenhausen and Wyner [

3] devised for computing

to be applicable for

as well. We illustrated this by deriving a closed form expression for

in the binary case—a result reminiscent of the Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma [

2] in information theory literature. We then showed that both

and

are closely related to several information-theoretic coding problems such as noisy random coding, hypothesis testing against independence, and dependence dilution. While these connections were partially known in previous work (see e.g., [

29,

30]), we show that they lead to an improvement on the cardinality of

T for computing

. We then turned our attention to the continuous setting where

X and

Y are continuous random variables. Solving the optimization problems in

and

in this case without any further assumptions seems a difficult challenge in general and leads to theoretical results only when

is jointly Gaussian. Invoking recent results on the entropy power inequality [

25] and strong data processing inequality [

27], we obtained tight bounds on

in two different cases: (1) when

Y is a Gaussian perturbation of

X and (2) when

X is a Gaussian perturbation of

Y. We also utilized the celebrated I-MMSE relationship [

107] to derive a second-order approximation of

when

T is considered to be a Gaussian perturbation of

X.

In the second part of the paper, we argue that the choice of (Shannon’s) mutual information in both

and

does not seem to carry specific operational significance. It does, however, have a desirable practical consequence: it leads to self-consistent equations [

1] that can be solved iteratively (without any guarantee to convergence though). In fact, this property is unique to mutual information among other existing information measures [

99]. Nevertheless, we argued that other information measures might lead to better interpretable guarantee for both

and

. For instance, statistical accuracy in

and privacy leakage in

can be shown to be precisely characterized by probability of correctly guessing (aka Bayes risk) or minimum mean-squared error (MMSE). Following this observation, we introduced a large family of optimization problems, which we call bottleneck problems, by replacing mutual information in

and

with Arimoto’s mutual information [

22] or

f-information [

23]. Invoking results from [

33,

34], we also demonstrated that these information measures are in general easier to estimate from data than mutual information. Similar to

and

, the bottleneck problems were shown to be fully characterized by boundaries of a two-dimensional convex set parameterized by two real-valued non-negative functions

and

. This perspective enabled us to generalize the technique used to compute

and

for evaluating bottleneck problems. Applying this technique to the binary case, we derived closed form expressions for several bottleneck problems.

X

X  T.

T.

X

X  T such that while ; making T a representation of X having perfect privacy (i.e., no information leakage about Y). A necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of such T is given in [21] (Lemma 10) and [13] (Theorem 3), described next.

T such that while ; making T a representation of X having perfect privacy (i.e., no information leakage about Y). A necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of such T is given in [21] (Lemma 10) and [13] (Theorem 3), described next. g(Y)

g(Y)  T, we have . On the other hand, we have if and only if there exists a variable satisfying and thus the following double Markov relations

T, we have . On the other hand, we have if and only if there exists a variable satisfying and thus the following double Markov relations

f(X)

f(X)  . One special case of this setting, namely where g is an identity function, has been recently studied in details in [53] and will be reviewed in Section 2.5. Theorem 3 also enables us to characterize the “worst” joint distribution with respect to and . As demonstrated in the following lemma, if is an erasure channel then .

. One special case of this setting, namely where g is an identity function, has been recently studied in details in [53] and will be reviewed in Section 2.5. Theorem 3 also enables us to characterize the “worst” joint distribution with respect to and . As demonstrated in the following lemma, if is an erasure channel then . X

X  T and hence specifies the strengthening of the data processing inequality of mutual information. This connection may open a new avenue for new theoretical results for , especially when X or Y are continuous random variables. In particular, the recent non-multiplicative SDPI results [27,83] seem insightful for this purpose.

T and hence specifies the strengthening of the data processing inequality of mutual information. This connection may open a new avenue for new theoretical results for , especially when X or Y are continuous random variables. In particular, the recent non-multiplicative SDPI results [27,83] seem insightful for this purpose.

X

X  T and taking values.

T and taking values.

X

X  T, generates unique and . We need the following basic definition from statistics.

T, generates unique and . We need the following basic definition from statistics.

X

X  T. Hence, both and must be smaller than . The properties listed in Lemma 7 enable us to derive a slightly tighter upper bound for as demonstrated in the following.

T. Hence, both and must be smaller than . The properties listed in Lemma 7 enable us to derive a slightly tighter upper bound for as demonstrated in the following. X

X  T and , the minimum is given by . Notice that, without any information constraint (i.e., ), . Perhaps surprisingly, this shows that the mutual information constraint has a linear effect on the privacy of Y. Similarly, to prove (51), we show that among all R-bit representations T of X, the best achievable accuracy is given by . This can be proved by combining Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma (cf. Lemma 4) and Fano’s inequality as follows. For all T such that , the minimum of is given by . Since by Fano’s inequality, , we obtain which leads to the same result as above. Nevertheless, in Appendix B we give another proof based on the discussion of Section 3.1.

T and , the minimum is given by . Notice that, without any information constraint (i.e., ), . Perhaps surprisingly, this shows that the mutual information constraint has a linear effect on the privacy of Y. Similarly, to prove (51), we show that among all R-bit representations T of X, the best achievable accuracy is given by . This can be proved by combining Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma (cf. Lemma 4) and Fano’s inequality as follows. For all T such that , the minimum of is given by . Since by Fano’s inequality, , we obtain which leads to the same result as above. Nevertheless, in Appendix B we give another proof based on the discussion of Section 3.1.

X

X  T. On the other hand, . Thus, both and equal for . Note also that where (see (39)) corresponding to the function . Consequently, and are characterized by the lower and upper boundary of , defined in (37), with respect to and . Specifically, we have

T. On the other hand, . Thus, both and equal for . Note also that where (see (39)) corresponding to the function . Consequently, and are characterized by the lower and upper boundary of , defined in (37), with respect to and . Specifically, we have

X

X  T, we have

T, we have

X

X  T} where represents the observable data X and target feature Y and the auxiliary random variable T varies over all possible choices satisfying the Markov relation Y

T} where represents the observable data X and target feature Y and the auxiliary random variable T varies over all possible choices satisfying the Markov relation Y  X

X  T. This unifying perspective on and allowed us to adapt the classical technique of Witsenhausen and Wyner [3] devised for computing to be applicable for as well. We illustrated this by deriving a closed form expression for in the binary case—a result reminiscent of the Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma [2] in information theory literature. We then showed that both and are closely related to several information-theoretic coding problems such as noisy random coding, hypothesis testing against independence, and dependence dilution. While these connections were partially known in previous work (see e.g., [29,30]), we show that they lead to an improvement on the cardinality of T for computing . We then turned our attention to the continuous setting where X and Y are continuous random variables. Solving the optimization problems in and in this case without any further assumptions seems a difficult challenge in general and leads to theoretical results only when is jointly Gaussian. Invoking recent results on the entropy power inequality [25] and strong data processing inequality [27], we obtained tight bounds on in two different cases: (1) when Y is a Gaussian perturbation of X and (2) when X is a Gaussian perturbation of Y. We also utilized the celebrated I-MMSE relationship [107] to derive a second-order approximation of when T is considered to be a Gaussian perturbation of X.

T. This unifying perspective on and allowed us to adapt the classical technique of Witsenhausen and Wyner [3] devised for computing to be applicable for as well. We illustrated this by deriving a closed form expression for in the binary case—a result reminiscent of the Mrs. Gerber’s Lemma [2] in information theory literature. We then showed that both and are closely related to several information-theoretic coding problems such as noisy random coding, hypothesis testing against independence, and dependence dilution. While these connections were partially known in previous work (see e.g., [29,30]), we show that they lead to an improvement on the cardinality of T for computing . We then turned our attention to the continuous setting where X and Y are continuous random variables. Solving the optimization problems in and in this case without any further assumptions seems a difficult challenge in general and leads to theoretical results only when is jointly Gaussian. Invoking recent results on the entropy power inequality [25] and strong data processing inequality [27], we obtained tight bounds on in two different cases: (1) when Y is a Gaussian perturbation of X and (2) when X is a Gaussian perturbation of Y. We also utilized the celebrated I-MMSE relationship [107] to derive a second-order approximation of when T is considered to be a Gaussian perturbation of X.Y

T, independent of X and T implies independence of Y and T and thus . Similarly for .

X

T.

Xn

Xn  Yn and . We can write

Yn and . We can write

Xk

Xk  Yk for every , we conclude from the above inequality that

Yk for every , we conclude from the above inequality that

Xn

Xn  Yn. Since and , we have This, together with (A3), concludes the proof. □

Yn. Since and , we have This, together with (A3), concludes the proof. □

X

X  T. This, together with Theorem 5, implies the result. □

T. This, together with Theorem 5, implies the result. □ X

X  T. This bound is attained by Gaussian . Specifically, assuming where for and independent of X, it can be easily verified that and . This, together with (A5), implies □

T. This bound is attained by Gaussian . Specifically, assuming where for and independent of X, it can be easily verified that and . This, together with (A5), implies □ X

X  Tσ, it follows that . Thus, two applications of (A6) yields

Tσ, it follows that . Thus, two applications of (A6) yields