1. Introduction

A very interesting problem in non-equilibrium thermodynamics and in the theory of thermodynamics in general, is to determine the efficiency with which energy is exchanged. In fact, in many biological systems, the transfer of energy is of decisive importance. It is well known that all intracellular processes can be studied as chemical reactions of some kind, and that many of the biochemical reactions in living organisms have been seen to be catalyzed by enzymes; there are some good examples where the energetic properties studied are really relevant [

1].

Considering the classical ideas of thermodynamics when one wants to analyze biological systems, it is typical to take the free energy of the biological system and convert it into work. For instance, to carry out a transport process or a chemical reaction, it is usual for this type of study to focus on analyzing the energetic properties of such systems. Note, however, that the subject is hard to study from the classical perspective of thermodynamics, since the temperature in many biological systems is homogeneous [

2]).

An additional step to analyze the energetic properties of a simple energy converter was given by Curzon and Ahlborn in 1975 [

3], who proposed a model which operates between two heat sources with high and low temperatures,

and

, respectively. They found an expression for the efficiency at maximum power output given by

, a result that in principle is independent of the model parameters and only depends on the temperatures of the heat reservoirs; analogously this is what happens with the efficiency for a reversible Carnot cycle

.

Considering the Curzon and Alhbor article, many authors began to introduce different objective functions, among others, such as the ecological function [

4], the omega function [

5], the efficient power function [

6], etc. All of them trying to obtain efficiency and power values mainly for real power plants, but also heat pumps and refrigerators [

7,

8].

Moreover, it was reported [

9,

10,

11] that thermal engines show some universality regarding the behavior of the efficiency when it works at the maximum power regime [

11], although the analyzed models are different in nature and scale [

12,

13,

14]. Recently, some thermal engines with kinetic [

15,

16,

17] and mesoscopic [

18] descriptions were published as examples of devices which convert non-thermal energy (mainly chemical energy) into useful work. The importance of these models is that the energy production processes seen in the molecular biological level obey similar principles as those observed in the classical thermal engines [

19].

On the other hand, Kedem et al. [

20] published in 1965 the first step of a non-equilibrium theory towards a description of linear converters of energy (which would be called Linear Irreversible Thermodynamics, LIT). Since then, many authors have agreed in considering this theory as a basis for the analysis of non-equilibrium systems, (particularly, in biological systems remarkably close to the equilibrium). One of the relevant questions tackled by Kedem et al. at that time was to answer which was the maximal efficiency of the oxidative phosphorylation in an isolated mitochondrion. Kandem et al. obtained some qualitative predictions confirmed by experimental data.

For biological process, for instance, several authors have studied different optimal regimes like Prigogine [

21] with his minimum entropy production theorem. Odun and Pinkerton [

22] who analyzed the maximum power output regime for various biological systems, Stucki [

2] who introduced some optimal criteria to study the optimum oxidative phosphorylation regime, among others [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] who have studied many biological energy conversion processes by means of the LIT where some optimum performance regimes have been analyzed.

In this context, we have decided to study the thermodynamical properties of an energetic converting biological process, using for this purpose a simple model for an enzymatic reaction that couples one exothermic and one endothermic reaction in the same fashion described by Diaz-Hernandez et al. [

15], but now using the Linear Irreversible Thermodynamics (LIT) for three different operating regimes,;namely, Maximum Power Output (MPO), Maximum Ecological Function (MEF) and Maximum Efficient Power Function (MEPF), respectively.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces a model and the phenomenological flow equations of a remarkably simple system enzymatic reaction coupled with ATP hydrolysis.

Section 3 presents the analysis of the optimal operation regimes in the context of the Linear Irreversible Thermodynamics. Finally,

Section 4 gives some concluding remarks.

2. The Model

Consider a simple enzymatic reaction coupled with ATP hydrolysis which might be written as [

15]:

where

E represents the enzyme,

X is the substrate and

Y is the product. Besides

and

are transient complexes of the enzyme with the substrate and the product respectively,

corresponds with the Adenosine Triphosphate,

is the Adenosine Diphosphate and

represents the inorganic phosphate.

Considering the first part of Equation (

1), it is possible to obtain the respective reaction velocity, which, according to the mass action law, is given by:

Now, using Arrhenius law, which establishes that,

where,

and

are the frequency factors,

and

are the activation reaction energies usually expressed in

and

R is the gas constant (expressed in

). Now, from

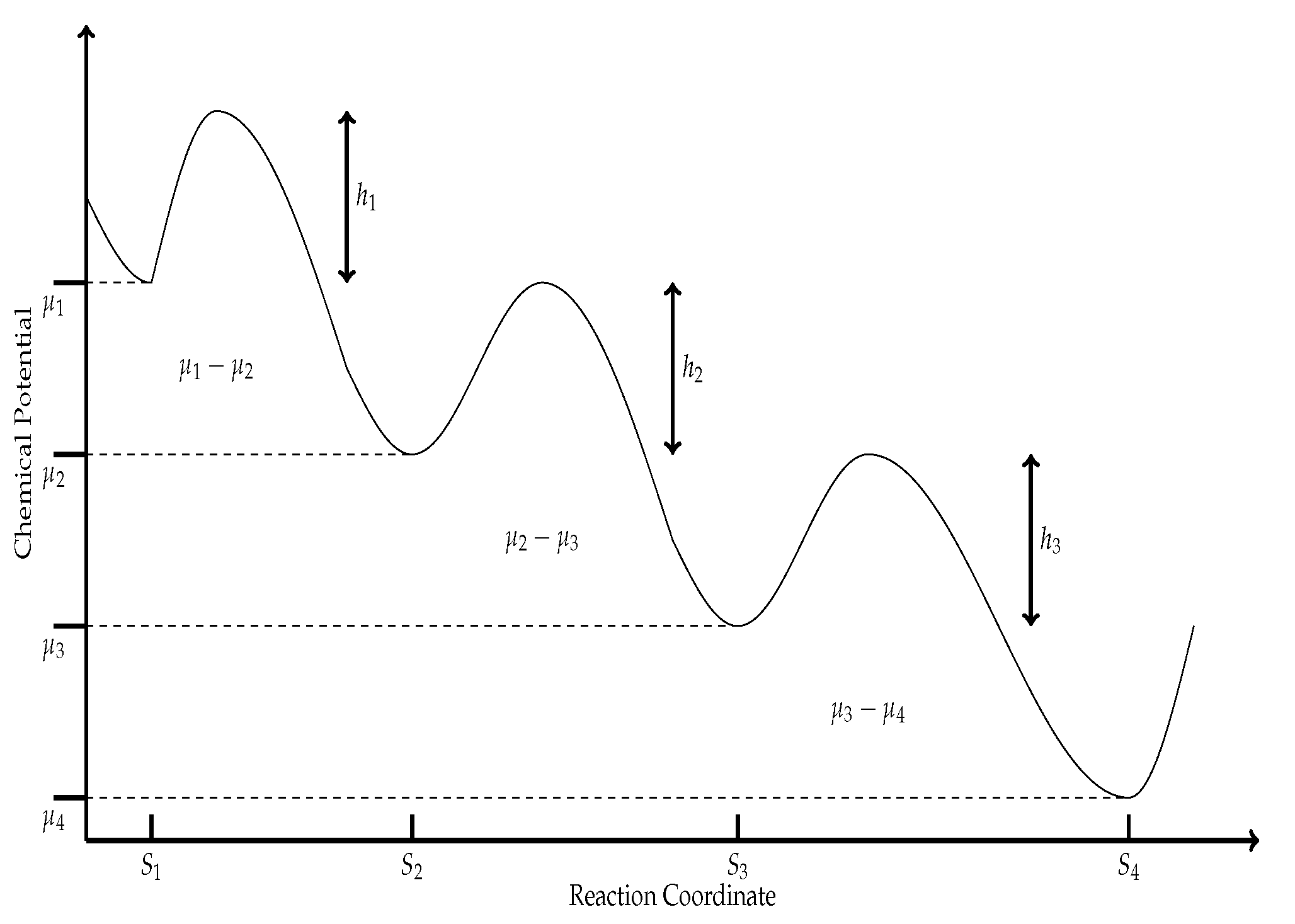

Figure 1, it is clear that both activation energies can be expressed as:

where

(

) is the corresponding chemical potential to the

ith state along with the reaction sequence, and

(

) is the minimum energy required for a collision between molecules to result in a chemical reaction, see

Figure 1.

Hence, using Equations (3) and (4) and substituting them into Equation (

2), we obtain the net velocities for the three reactions in (1) as:

where

and

is defined in terms of the molar concentrations and the frequency factors [

29]. Then, after some algebra, the above equation can be written as,

where

(with

) and

is defined as before.

Therefore, by using Equation (

6) we can obtain the respective velocities of each reaction as;

Now, considering for simplicity that

and defining

(later we will see that

is going to be related to the coupling coefficient

q), as Diaz-Hernandez et. al. [

15] did in their model using a different approach, we can re-write Equations (7) as;

Since for reactions near equilibrium, the affinity is small, making a Taylor expansion around zero is justified. Keeping this in mind, it is possible to transform Equation (

8) into;

where we just keep the linear terms in the expansion.

From classical non-equilibrium studies, we can, under suitable conditions, define macroscopic variables locally, as gradients and flux densities. Such variables are called “thermodynamic forces” which drives flux densities often called “fluxes”. Following the Onsager formalism [

30] we can establish a relation between such forces and fluxes near the steady thermodynamically non-equilibrium regime naming them phenomenological relations [

26], given by

where,

are the phenomenological coefficients usually depending on the intensive variables which describes the coupling between two irreversible process

and

, and

are the respective thermodynamic forces. It is worthwhile to mention that in 1931 Onsager [

30] demonstrated that for a system of flows and forces based on an appropriate dissipation function, the matrix of coefficients is symmetrical so that the phenomenological coefficients have the following symmetry relation

, which affords a considerable reduction in the number of coefficients measured.

Then, taking the above into account, it is possible for our system, to establish two thermodynamic flows

and

for which, we may write the following phenomenological equations;

where, we are assuming that

.

In the classical equations of chemical kinetics, which are known to describe a chemical process quite precisely, the reaction rates are proportional to the concentrations. On the other hand, phenomenological equations require that the reaction velocity are proportional to the thermodynamic force, which in this case is the Affinity, which is in turn proportional to logarithms of concentration. To remove this inconsistency, we must consider this phenomenological description in the neighborhood of equilibrium when the rate of chemical change is sufficiently slow [

31].

According to earlier considerations, if we consider that the driving force for the reaction is the affinity, then close to equilibrium, the chemical flow

should be proportional to the force:

where

are the phenomenological coefficients and

is the Affinity. Therefore, assuming that for our chemical reactions the phenomenological relation between fluxes and forces is,

where

(

) are the net velocities defined in Equation (

9). Then, from Equation (

13) and substituting Equation (

9) in it, we can write;

which can be rewritten as:

It is worthwhile to analyze Equation (

15). From the scheme in

Figure 1, we observe that it corresponds to three sequential equations, all three reactions can be lumped into a single global reaction with free energy change for this reaction as

. Of the three reactions represented in

Figure 1, only in the second one, the consumed energy is used for an interesting purpose; the conversion of the substrate

X into the product

Y, and the free energy for this reaction is

. So one possible physical meaning of

is some dissipation-like energy. Then, we can later propose a linear flux–force relation for the enzymatic reaction model as,

where in the context of linear irreversible thermodynamics we can identify

,

,

, and

, where the parameter

was previously introduced in Equation (

7).

We should note that is related to the minimum energy required for a collision between molecules. Thus, this energy could be different for the different stages in the enzymatic reaction causing the phenomenological coefficients to be different, then the degree of coupling q is also different in each stage influencing the thermodynamic properties of the system (for instance, the power output or the entropy production). Considering the latter, we assume that the simplest case is one in which the coefficients are proportional to each other.

Following the concepts of classical thermodynamics, the efficiency function can be defined as [

24],

From Equation (

16), it is possible to substitute

and

into Equation (

17), which yields,

where,

is the stoichiometric coefficient,

is the phenomenological stoichiometry [

2] and

is the degree of coupling.

Substituting these last expressions in Equation (

18) we obtain,

If we take the special case of complete coupling, i.e.,

(from Equation (

18) we can notice that for

,

) in Equation (

19), it is easy to observe that,

which is highly similar to that obtained by Diaz-Hernandez et. al. [

15] for a similar model using a different approach. Furthermore,

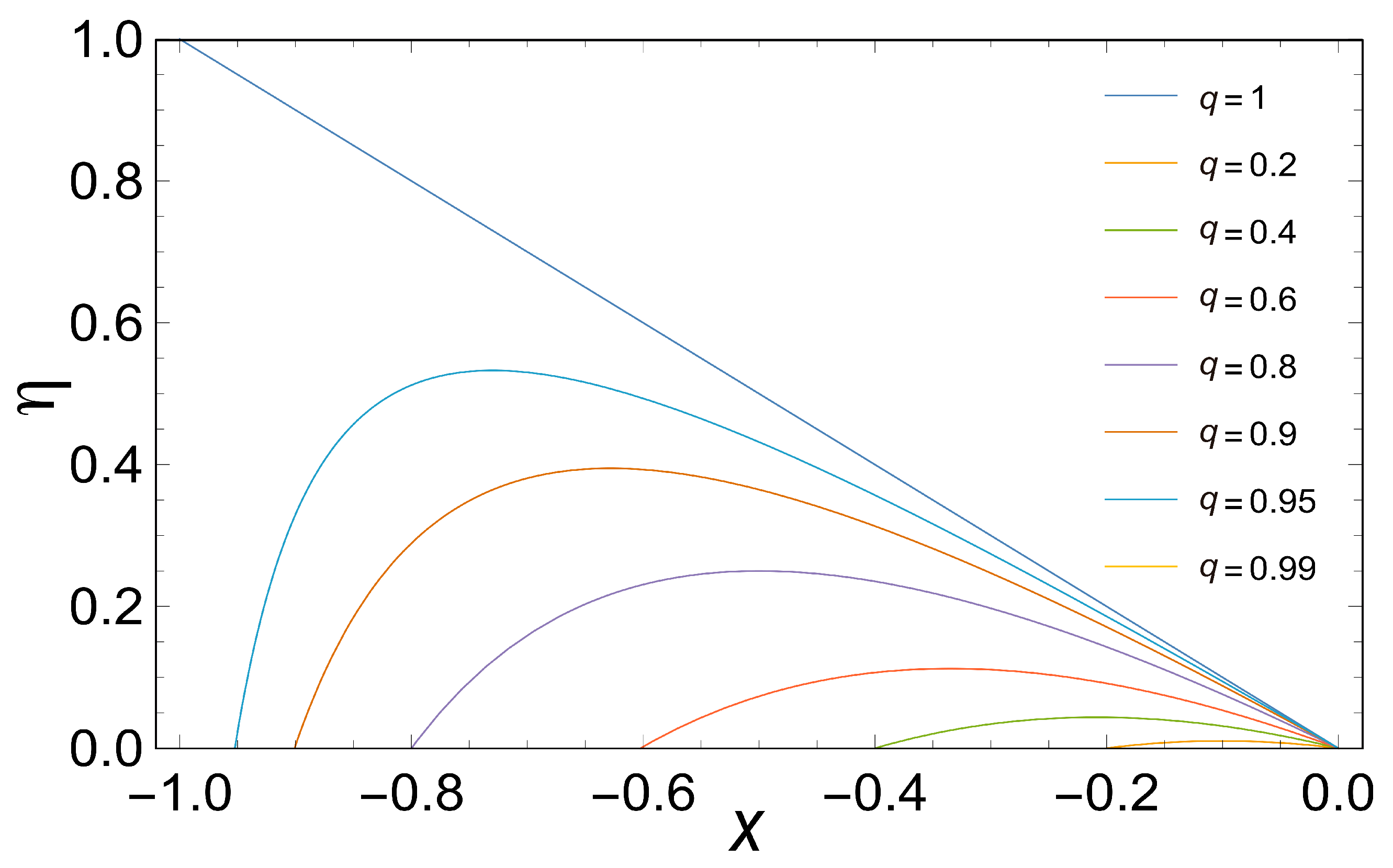

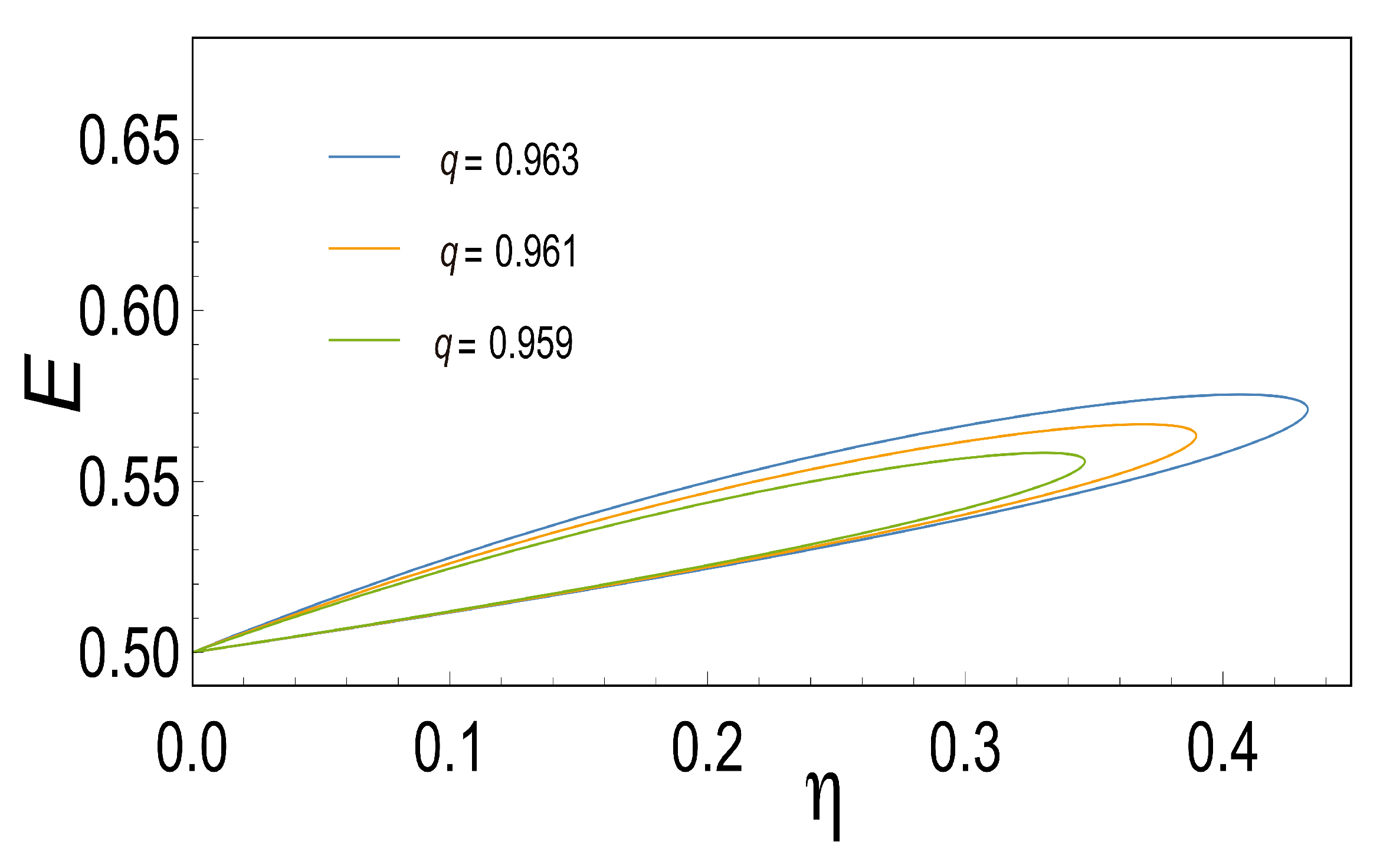

Figure 2 shows the efficiency plotted as a function of the stoichiometric coefficient for various values of

q. Note the fast decay of

with the decreasing of

q.

4. Concluding Remarks

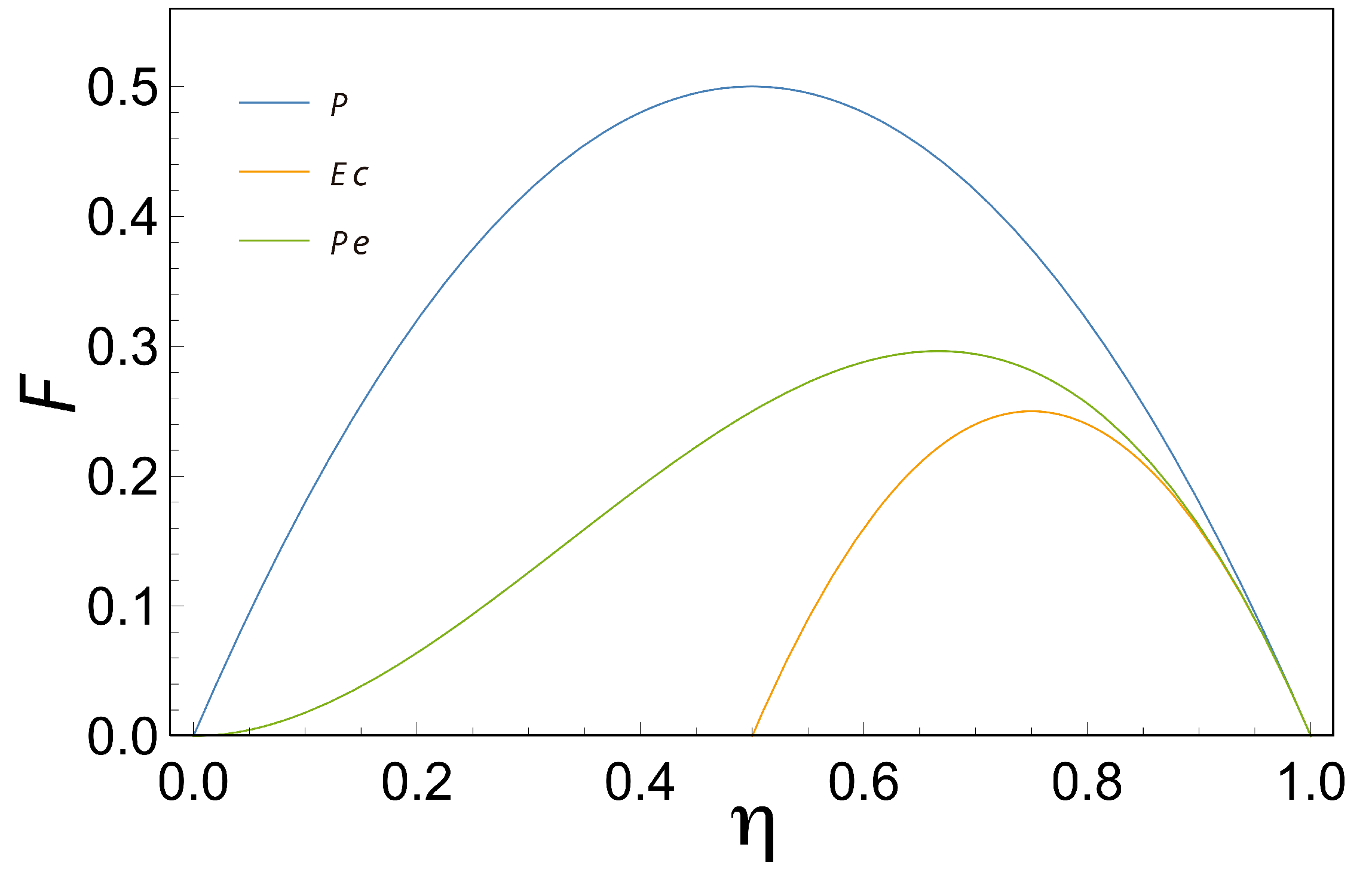

Many of the intra-cellular processes are studied based on some kind of a chemical reaction. In this work, by using a general model for enzymatic reaction that couples an exothermic with an endothermic reactions (and keeping in mind that most of the biochemical reactions in living organisms are catalyzed by enzymes), we analyzed the efficiency with which energy is exchanged between these reactions, but from the point of view of the non- equilibrium thermodynamics. By using the Linear Irreversible Thermodynamics, it is possible to analyze three different regimes of operation, namely, Maximum Power Output (MPO), Maximum Ecological Function (MEF) and Maximum Efficient Power Function (MEPF).

With that in mind, it is possible to obtain similar expressions for the Power Output and the Ecological Function previously reported by Diaz-Hernandez et al. [

15], when the degree of coupling

q is equal to one. It is worth mentioning that the studied model is completely based on well known biochemical facts, and in this work, in the context of the Linear Irreversible Thermodynamics, it is possible to generalize the obtained results, where all the thermodynamic features are determined by the chemical potential gap

, the efficiency

, and the degree of coupling

q. Moreover, using the same formulation it is possible to add another regime named the Maximum Efficient Power Function in terms of the aforementioned parameters (Equation (

31)).

Based on

Figure 2, efficiency is a function of the force ratio

for various values of

q. Note the very rapid fall in

with the decreasing of

q. Again, in the limit

, we obtained results comparable to those obtained by Diaz-Hernandez et al. This limit has particularly important thermodynamic implications, since a perfect coupling implies that the flows are not linearly independent. Considering the above, we obtain the efficiency that maximizes the three characteristic functions (MPO, MEF, MPEF), when

, we observe that

,

and

, as is shown in

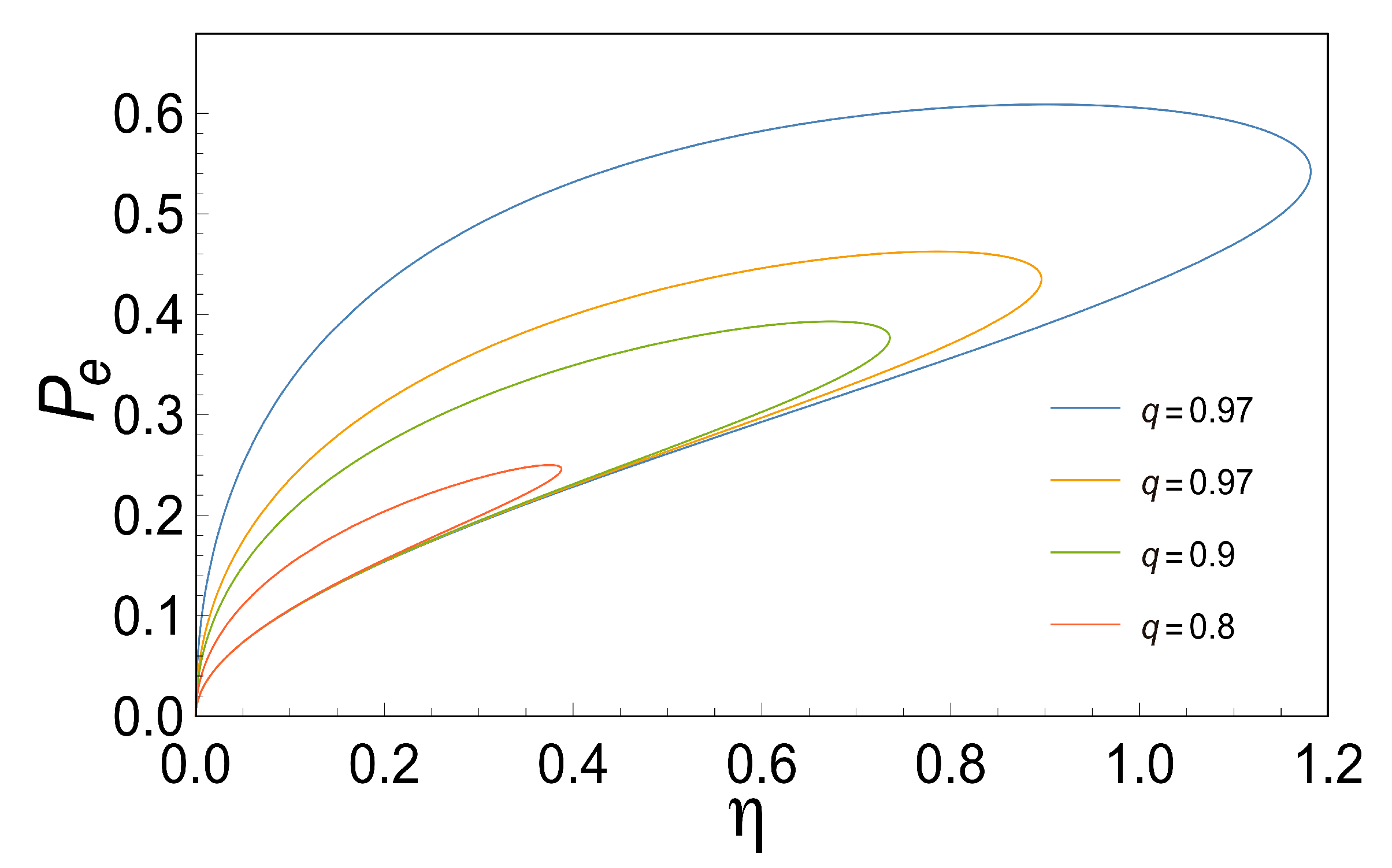

Figure 3.

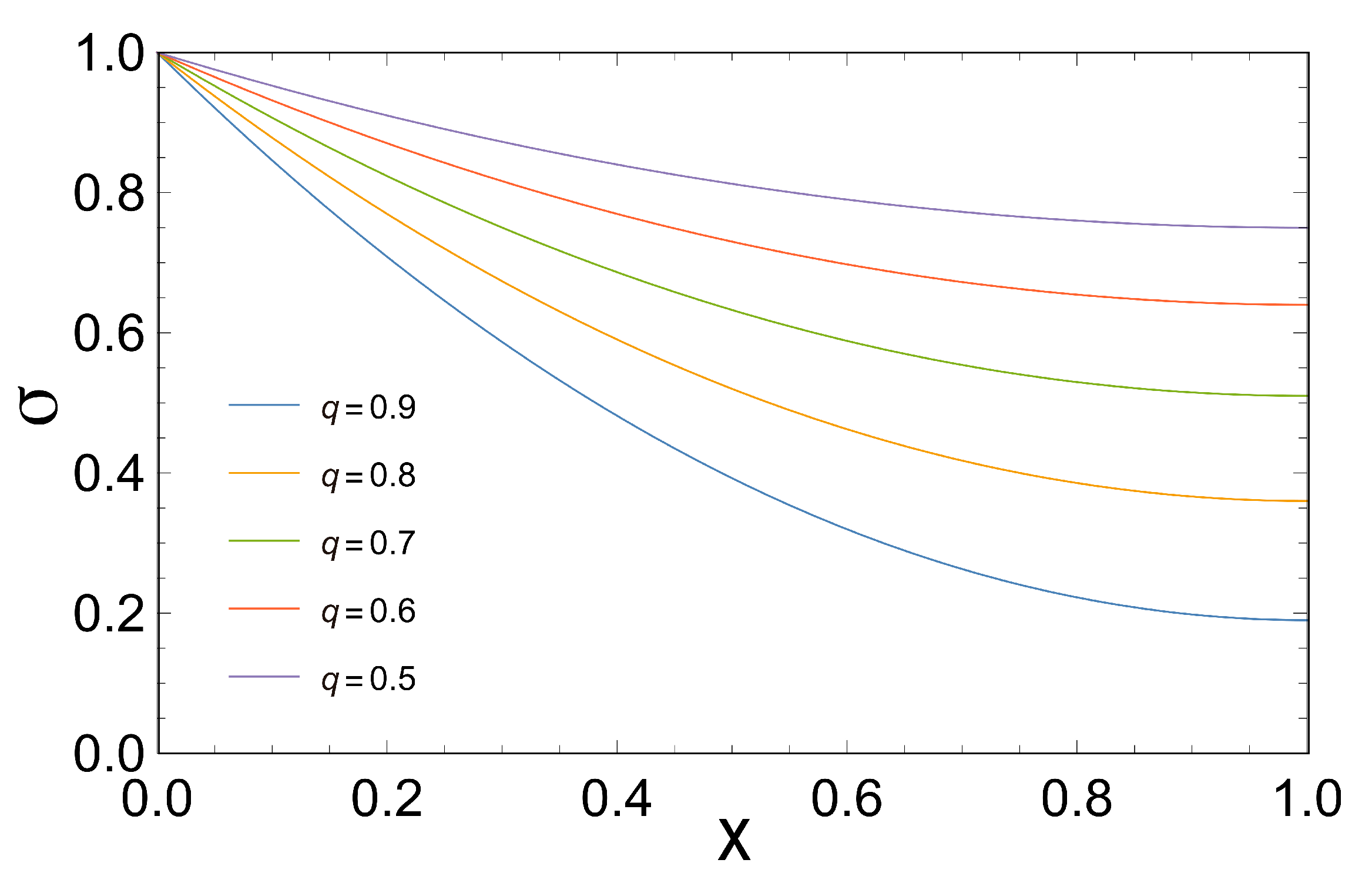

However, in more realistic scenarios the coupling coefficient

q is less than one, for instance Stucki [

2] reported an experimental

for liver mitochondria in male rats. In this case (

), we have obtained the efficiency that maximizes the three characteristic functions and also the series expansions in terms of

q resembling comparable results yielded by other already cited authors.

Since the three characteristic functions (see Equations (24), (28) and (31)) are determined by three parameters (

and

) and a variation of

(this can be achieved assuming a variation of the substrate and the end-product concentrations), the thermodynamic properties could improve because these characteristic functions are proportional to

. The latest could be the reason why some biomolecular machines can achieve high speed without sacrificing efficiency [

36].

Now, from Equations (33), (34) and (35), it is clear that the efficiency that maximizes some of the characteristic functions is related only to

q, so at the end, the thermodynamic properties are related to the degree of coupling providing the basis for comparing different types of coupling in a two-flow system. In other words, the relevant question in many biological situations could be: what is the efficiency with which free energy is exchanged between coupled chemical reactions? (question already made by other authors [

26]). Here, the answer is in some sense clear; it depends only on the coupling coefficient and not on the individual phenomenological coefficients, which can be interpreted within the framework of non-equilibrium thermodynamics.