Foliations-Webs-Hessian Geometry-Information Geometry-Entropy and Cohomology

Abstract

:Contents

- 1 Introduction 4

- 1.1 The Notation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

- 1.2 Some Explicit Formulas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

- 1.3 The content of the Paper . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

- 3 The Theory of Cohomology of KV Algebroids and Their Modules 11

- 3.2 The Theory of KV Cohomology—Version: the Semi-Simplicial Objects . . . . . . . . . . 14

- 3.2.1 Extension . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

- 3.2.2 Construction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

- 3.2.3 Notation-Definitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

- 3.2.4 The KV Chain Complex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

- 3.2.5 The V-Valued KV Homology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

- 3.2.6 Two Cochain Complexes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

- 3.2.7 Residual Cohomology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

- 3.3 The Theory of KV Cohomology—Version the Anomaly Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

- 3.3.1 The General Challenge CH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

- 3.3.3 The KV Cohomology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

- 3.3.4 The Total Cohomology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

- 3.3.5 The Residual Cohomology, Some Exact Sequences, Related Topics, DTO-HEG-IGE-ENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

- 4 The KV Topology of Locally Flat Manifolds 26

- 5 The Information Geometry, Gauge Homomorphisms and the Differential Topology 35

- 5.1 The Dualistic Relation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

- 5.1.1 Statistcal Reductions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

- 5.1.2 A Uselful Complex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

- 5.1.3 The Homological Nature of Gauge Homomorphisms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

- 5.1.4 The Homological Nature of the Equation FE∇∇* . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

- 5.1.5 Computational Relations. Riemannian Foliations. Symplectic Foliations: Continued . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

- 5.1.6 RiemannianWebs—SymplecticWebs in Statistical Manifolds . . . . . . . . . . . 49

- 5.2 The Hessian Information Geometry, Continued . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

- 5.3 The a-Connetions of Chentsov . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

- 5.4 The Exponential Models and the Hyperbolicity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

- 6 The Similarity Structure and the Hyperbolicity 58

- 7 Some Highlighting Conclusions 59

- 7.1 The Total KV Cohomology and the Differential Topology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

- 7.2 The KV Cohomology and the Geometry of Koszul . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

- 7.3 The KV Cohomology and the Information Geometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

- 7.4 The Differential Topology and the Information Geometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

- 7.5 The KV Cohomology and the Linearization Problem for Webs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

- 8 B. The Theory of StatisticaL Models 61

- 8.1 The Preliminaries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

- 8.3 The Category . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

- 8.3.1 The Objects of . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

- 8.3.2 The Global Probability Density of a Statistical Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

- 8.3.3 The Morphisms of . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

- 8.3.4 Two Alternative Definitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

- 8.3.5 Fisher Information in . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

- 8.4 Exponential Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

- 8.4.1 The Entropy Flow . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

- 8.4.2 The Fisher Information as the Hessian of the Local Entropy Flow . . . . . . . . . 75

- 8.4.3 The Amari-Chentsov Connections in . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

- 8.4.4 The Homological Nature of the Probability Density . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

- 8.4.5 Another Homological Nature of Entropy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

- 9 The Moduli Space of the Statistical Models 78

- 10 The Homological Statistical Models 83

- 11 The Homological Statistical Models and the Geometry of Koszul 88

- 12 Examples 88

- 13 Highlighting Conclusions 91

- 13.1 Criticisms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

- 13.2 Complexity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

- 13.3 KV Homology and Localization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

- 13.4 The Homological Nature of the Information Geometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

- 13.5 Homological Models and Hessian Geometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

- A Appendix A 92

- A.1 The Affinely Flat Geometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

- A.2 The Hessian Geometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

- A.3 The Geometry of Koszul . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

- A.4 The Information Geometry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

- A.5 The Differential Topology of a Riemannian Manifold . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

1. Introduction

1.1. The Notation

- (A.1)

- is a first order differential operator. It is defined in the vector bundle . Its values belong to the vector bundle .

- (A.2)

- and are 2nd order differential operators. They are defined in the vector bundle . Their values belong to the vector bundle . Let X be a section of and let ψ be a section of . The differential operators just mentioned are defined byPart A of this paper is partially devoted to the global analysis of the differential equationThe solutions to are useful for addressing the links between the KV homology, the differential topology and the information geometry.The purpose of a forthcoming paper is the study of the differential equationsIn the Appendix A to this paper we overview the role played by the solutions to in some still open problems.

1.2. Some Explicit Formulas

- (1)

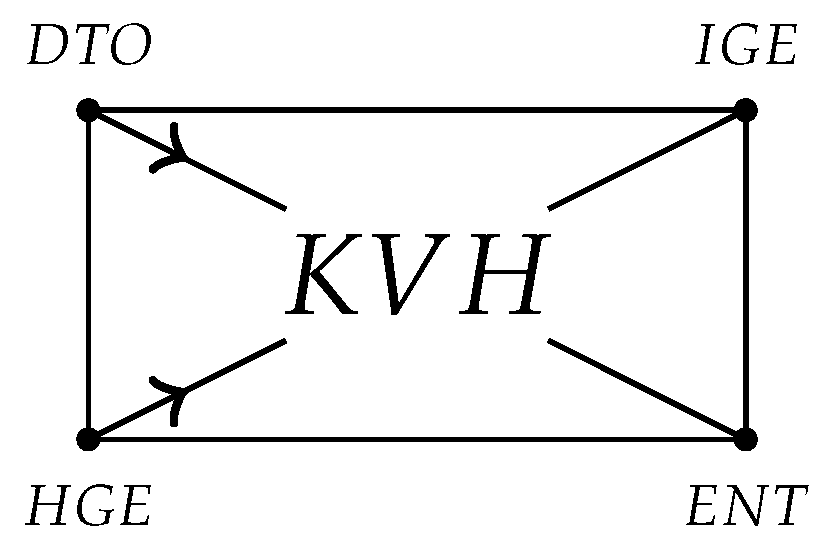

- DTO stands for Differential TOpology. In DTO, FWE stands for Foliations and WEbs.

- (2)

- HGE stands for Hessian GEometry. Its sources are the geometry of bounded domains, the topology of bounded domains, the analysis in bounded domains. Among the notable references are [1,2,3]. Hessian geometry has significant impacts on thermodynamics, see [4,5], About the impacts on other related topics the readers are referred to [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

- (3)

- IGE stands for Information GEometry. That is the geometry of statistical models. More generally its concern is the differential geometry of statistical manifolds. The range of the information geometry is large [13]. Currently, the interest in information geometry is increasing. This comes from the links with many major research domains [14,15,16]. We address some significant aspects of those links. Non-specialist readers are referred to some fundamental references such as [17,18]. See also [4,19,20,21,22,23]. The information geometry also provides a unifying approach to many problems in differential geometry, see [21,24,25]. The information geometry has a large scope of applications, e.g., physics, chemistry, biology and finance.

- (4)

- ENT stands for ENTropy. The notion of entropy appears in many mathematical topics, in Physics, in thermodynamics and in mechanics. Recent interest in the entropy function arises from its topological nature [14]. In Part B we introduce the entropy flow of a pair of vector fields. The Fisher information is then defined as the Hessian of the entropy flow.

- (5)

- KVH stands for KV Homology. The theory of KV homology was developed in [9]. The motivation was the conjecture of M. Gerstenhaber in the category of locally flat manifolds. In this paper we emphasize other notable roles played by the theory of KV homology. It is also useful for discussing a problem raised by John Milnor in [26].

1.3. The content of the Paper

2. Algebroids, Moduls of Algebroids, Anomaly Functions

2.1. The Algebroids and Modules

2.2. Anomaly Functions of Algebroids and of Modules

- (1)

- The associator anomaly function of is defined by

- (2)

- The Koszul-Vinberg anomaly function of is defined by

- (3)

- The Jacobi anomaly functions of are defined by

- (1)

- The associator anomaly function of a left module is defined as

- (2)

- The KV anomaly functions of a two sided module are defined as

- (1)

- The Leibniz anomaly function of an anchored algebroid is defined by

- (2)

- The Leibniz anomaly function of the -module is defined by

3. The Theory of Cohomology of KV Algebroids and Their Modules

3.1. The Theory of KV Cohomology—Version the Brute Formula of the Coboundary Operator

3.1.1. The Cochain Complex .

3.1.2. The Total Cochain Complex

- (1):

- (2):

3.2. The Theory of KV Cohomology—Version: the Semi-Simplicial Objects

3.2.1. Extension

3.2.2. Construction

3.2.3. Notation-Definitions

3.2.4. The KV Chain Complex

3.2.5. The V-Valued KV Homology

3.2.6. Two Cochain Complexes

3.2.7. Residual Cohomology

- (1)

- The vector subspace of residual KV cocycles of degree q is denoted by .

- (2)

- The vector subspace of residual coboundaries of degree q is defined by The residual KV cohomology space of degree q is the quotient vector space.

- (3)

- (4)

- By replacing the KV complex by the total KV complex one defines the vector space of residual total cocycles and the space of residual total coboundaries . Therefore we get the residual total KV cohomology space

- :

- We replace the KV by . Then we obtain the exact sequences

- :

- The KV cohomology difers from the total cohomology. Loosely speaking their intersecttion is the equivariant cohomology their difference is the residual cohomology. The domain of their efficiency are different as well. Here are two illustrations.

3.3. The Theory of KV Cohomology—Version the Anomaly Functions

3.3.1. The General Challenge

- (1)

- V is an (abstract) two sided module of an (abstract) algebra .

- (2)

- and are fixed anomaly functions of and of V respectively.

- (3)

- stands for the -graded vector space

3.3.2. Challenge for KV Algebras

3.3.3. The KV Cohomology

3.3.4. The Total Cohomology

3.3.5. The Residual Cohomology, Some Exact Sequences, Related Topics, DTO-HEG-IGE-ENT

4. The KV Topology of Locally Flat Manifolds

4.1. The Total Cohomology and Riemannian Foliations

- (1.1)

- (1.2)

- A symplectic foliation is a ( de Rham) closed differential 2-form ω which satisfies

- (2.1)

- ,

- (2.2)

- .

4.2. The General Linearization Problem of Webs

4.3. The Total KV Cohomology and the Differential Topology Continued

- (1)

- is transversally Riemannian if there exists a such that

- (2)

- is transversally symplectic if there exists a (de Rham) closed differential 2-form ω such that

- (1)

- Suppose thatTherefore, is a D-geodesic Riemannian foliation.

- (2)

- Suppose thatThen is a Riemannian manifold the Levi-Civita connection of which is D. Therefore, the proposition holds. ☐

4.4. The KV Cohomology and Differential Topology Continued

4.4.1. Kernels of 2-Cocycles and Foliations

- (1)

- The left kernel of every KV 2-cocycle is closed under the Poisson bracket of vector fields.

- (2)

- The right kernel of every KV 2-cocycle is a KV subalgebra of the KV algebra .

- (1)

- The arrowmaps the set of analytic 2-cocycles in the category of analytic stratified foliations M,

- (2)

- The arrowmaps the set of analytic 2-cocycles in the category of stratified locally flat foliations,

- (3)

- If a 2-cocycle g is a symmetric form then is a stratified locally flat transversally Riemannian foliation.

5. The Information Geometry, Gauge Homomorphisms and the Differential Topology

- (i)

- The first is the existence problem for Riemannian foliations.

- (ii)

- The second is the linearization of webs.

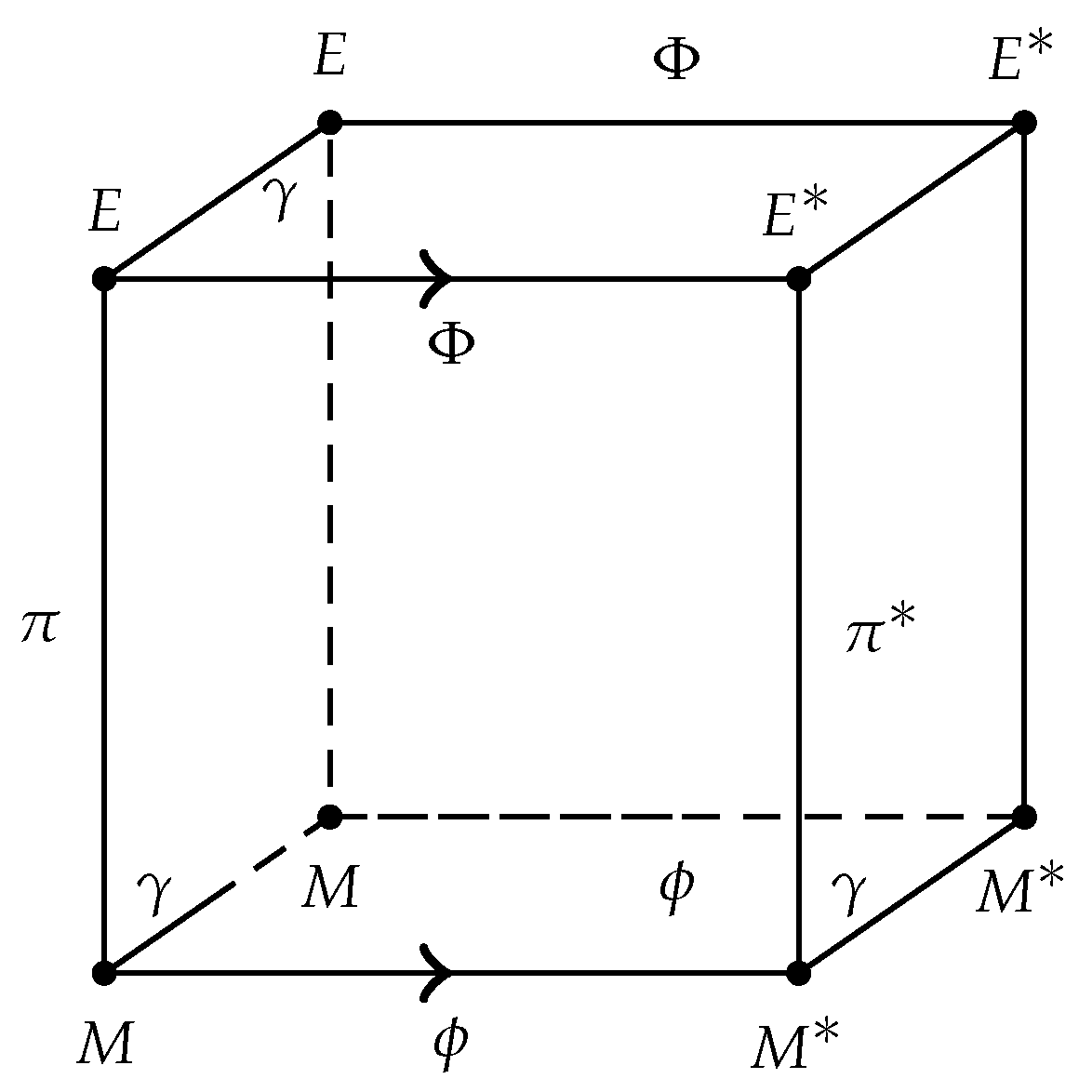

5.1. The Dualistic Relation

- (1)

- A dual pair is called a flat pair if the connection D is flat, viz

- (2)

- A flat pair is called a dually flat pair if both and are locally flat manifolds.

- (1)

- Both D and are torsion free.

- (2)

- D is torsion free and A is symmetric, viz

- (3)

- is torsion free and the metric tensor g a is KV cocycle of the KV algebra of the locally flat manifold .

- (4)

- The flat pair is a dually flat pair.

- (1)

- is a dually flat pair.

- (2)

- (1)

- .

- (2)

- is a dually flat pair.

- (1)

- (2)

- .

- (1)

- (2)

- (1)

- ,

- (2)

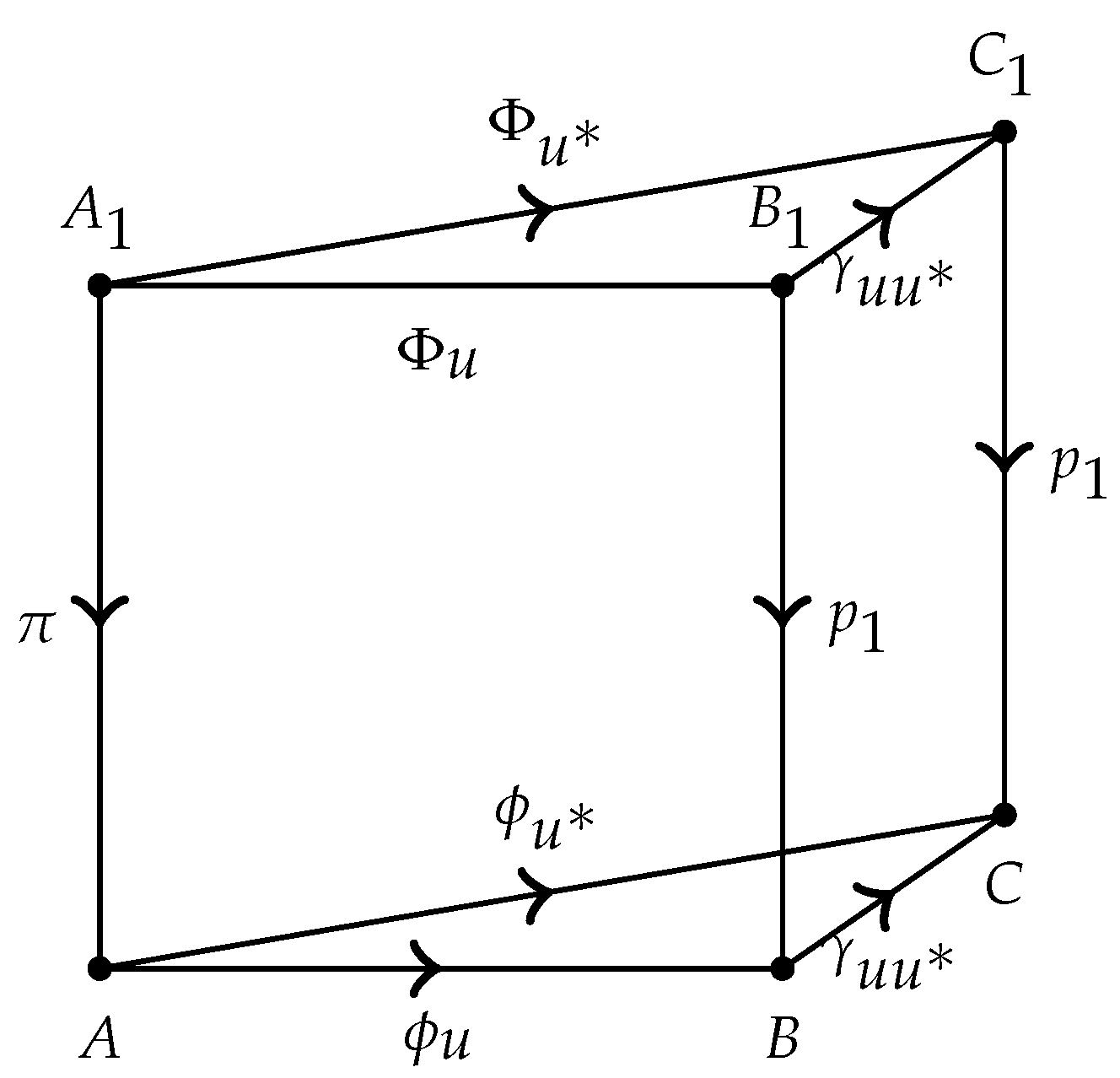

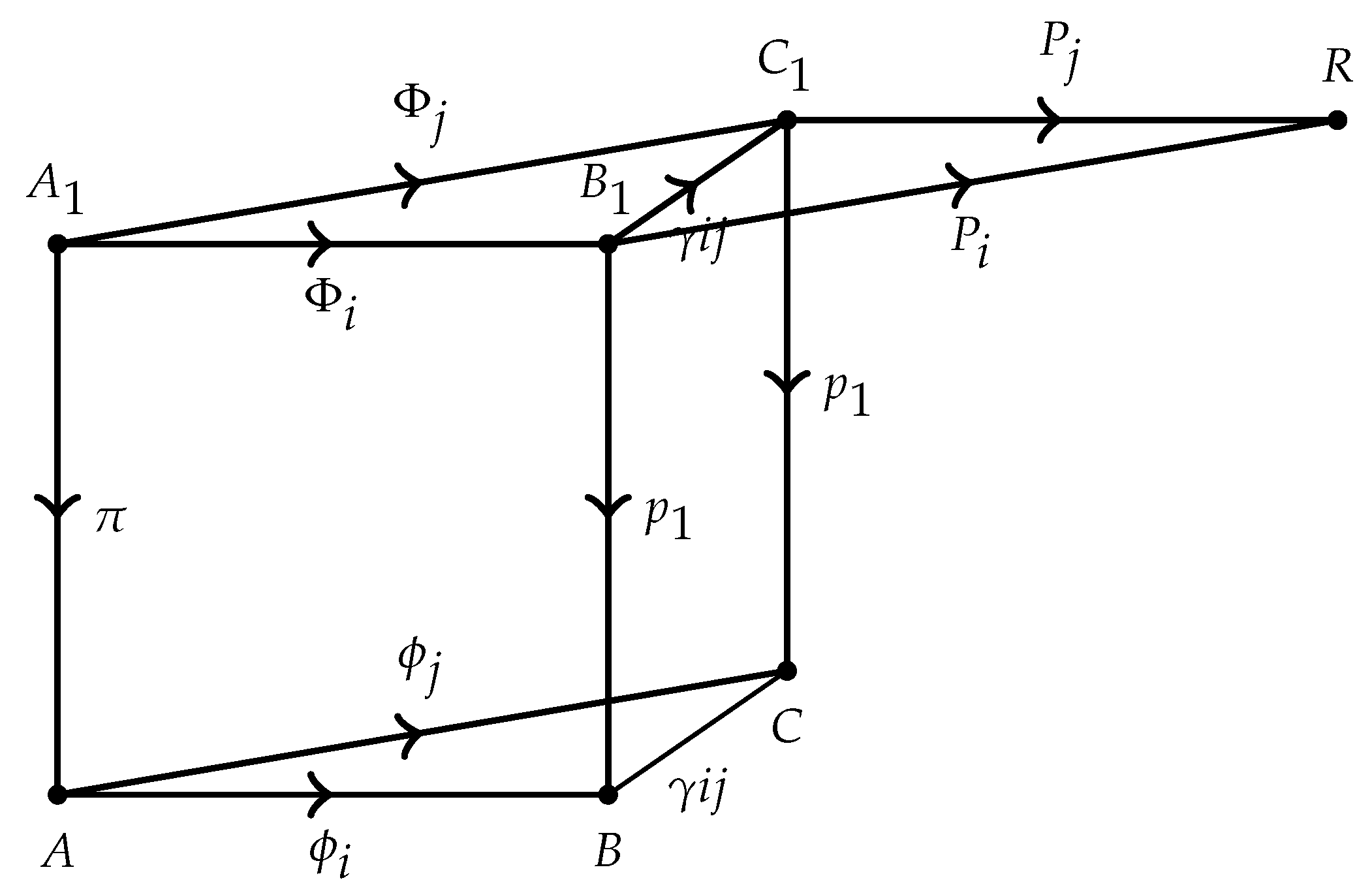

5.1.1. Statistcal Reductions

5.1.2. A Uselful Complex

5.1.3. The Homological Nature of Gauge Homomorphisms

- (1)

- (2)

5.1.4. The Homological Nature of the Equation

- (1)

- is an exact (1,2)-cocyle,

- (2)

- .

5.1.5. Computational Relations. Riemannian Foliations. Symplectic Foliations: Continued

- (a)

- A ∇-geodesic symplectic foliation might carry richer structures such as Kahlerian structures.

- (b)

- Suppose that the manifold M is compact and suppose that is a positive Riemannian foliation, viz

- (c)

- In the principal bundle of first order linear frames of M the analog of a Koszul connection ∇ is a principal connection 1-form ω whose curvature form is denoted by Ω. The curvature form is involved in constructing characteristic classes of M, (the formalism of Chern-Weill.)

- (1)

- The g-symmetric part of ψ, is defined by

- (2)

- The g-skew symmetric part of ψ, is defined by

- (1)

- The g-symmetric part is an element whose rank is constant.

- (2)

- We have the g-orthogonal decomposition

- (3)

- If both ∇ and are torsion free then and are completely integrable.

5.1.6. Riemannian Webs—Symplectic Webs in Statistical Manifolds

- (a)

- (b)

5.2. The Hessian Information Geometry, Continued

5.3. The α-Connetions of Chentsov

- (1)

- the functionis smooth.

- (2)

- the tripleis a probability space.

- (3)

- with there exists such that(with the requirement (3) is called identifiable.)

- (4)

- The differentiation commutes with the integration The Fisher information of a model is the symmetric bi-linear form g which is defined byHere stands for the differentiation with respect to the argument .

- (5)

- The Fisher information is positive definite.

- (i)

- is called a singular section if each is non inversible.

- (ii)

- is called a simple section if each is simple.

- (1)

- If , then both and coincide with the Levi-Civita connection of B. This implies , this contradicts our choice of α.

- (2)

- If then and are geodesic for both and . Thus the pair defines a g-orthogonal 2-web.

5.4. The Exponential Models and the Hyperbolicity

- (1)

- There exists such that

- (2)

- The model is an exponential model.

- (i)

- It must be noticed that the demonstration above is independent of the rank of the Fisher information g. Therefore, the theorem holds in singular statistical models.

- (ii)

- In regular statistical models the theorem above leads to the notion of e-m-flatness as in [18].

- (iii)

- When the Fisher information g is semi-definite the dualistic relation is meaningless. However data may be regarded as data depending on the transversal structure of the distribution .

- (iv)

- In the analytic category the Fisher information is a Riemannian foliation. Therefore, both the information geometry and the topology of information are transversal concepts. This may be called the transversal geometry and the transversal topology of Fisher-Riemannian foliations.

- (v)

- The theorem above does not solve the question as how far from being an exponential family is a given model. It only tells us that exponential families are objects of the Hessian geometry.

6. The Similarity Structure and the Hyperbolicity

- (1)

- The locally flat manifold is hyperbolic,

- (2)

- the locally flat manifold admits a global similarity vector field .

- (1)

- The gauge structure is called a similarity structure if ∇ admits a global similarity vector field .

- (2)

- A dual pair is a similarity dual pair if either or is a similarity structure.

7. Some Highlighting Conclusions

7.1. The Total KV Cohomology and the Differential Topology

7.2. The KV Cohomology and the Geometry of Koszul

7.3. The KV Cohomology and the Information Geometry

7.4. The Differential Topology and the Information Geometry

7.5. The KV Cohomology and the Linearization Problem for Webs

- (i)

- Elements of are LINEARIZABLE symplectic k-webs.

- (ii)

- Elements of are LINEARIZABLE Riemannian k-webs.

8. B. The Theory of StatisticaL Models

- (1)

- The manifold Θ is an open subset of the m-dimensional Euclidean space .

- (2)

- P is a positive real valued functionsubject to the requirements which follow.

- (3)

- The function is differentiable with respect to .

- (4)

- For every fixed one setthen the tripleis a probability space, vizFurthermore the operation of differentiationcommutes with the operation of integration .

- (5)

- is identifiable, viz forif and only if

- (6)

- The Fisher informationis positive definite.

- (i)

- is smooth,

- (ii)

- ,

- (iii)

- the commutes with ,

- (iv)

- ,

- (v)

- if then if and only if ,

- (vi)

- (1)

- If there exists such that

- (2)

- (3)

8.1. The Preliminaries

- (1)

- for every vector field X the real number is non negative, furthermore such that

- (2)

- for every , the random KV cochainwithis a random cocycle of the KV complex .

8.2. The Category

8.2.1. The Objects of

- (1)

- M is a connected m-dimensional smooth manifold. The mapis a locally trivial fiber bundle whose fibers are isomorphic to the set Ξ.

- (2)

- The pair is an m-dimensional locally flat manifold.

- (3)

- There is a group actionThat action is subject to the compatibility requirement

- (4)

- Every point has an open neighborhood U which is the domain of a local fiber chartThe local charts are subject to the following compatibility relation

- is an affine local chart of the locally flat manifold

- (5)

- We setLet and be two local charts withthen there exists a unique such that

8.2.2. The Morphisms of

8.3. The Category

8.3.1. The Objects of

8.3.2. The Global Probability Density of a Statistical Model

- (i)

- We take into account the global probability density p. Then an object of the category is denoted by

- (ii)

- The function p is Γ-equivariant. THIS IS THE GEOMETRY in the sense of Erlangen program.

- (iii)

- We have not used any argument depending the dimension of manifolds.

8.3.3. The Morphisms of

8.3.4. Two Alternative Definitions

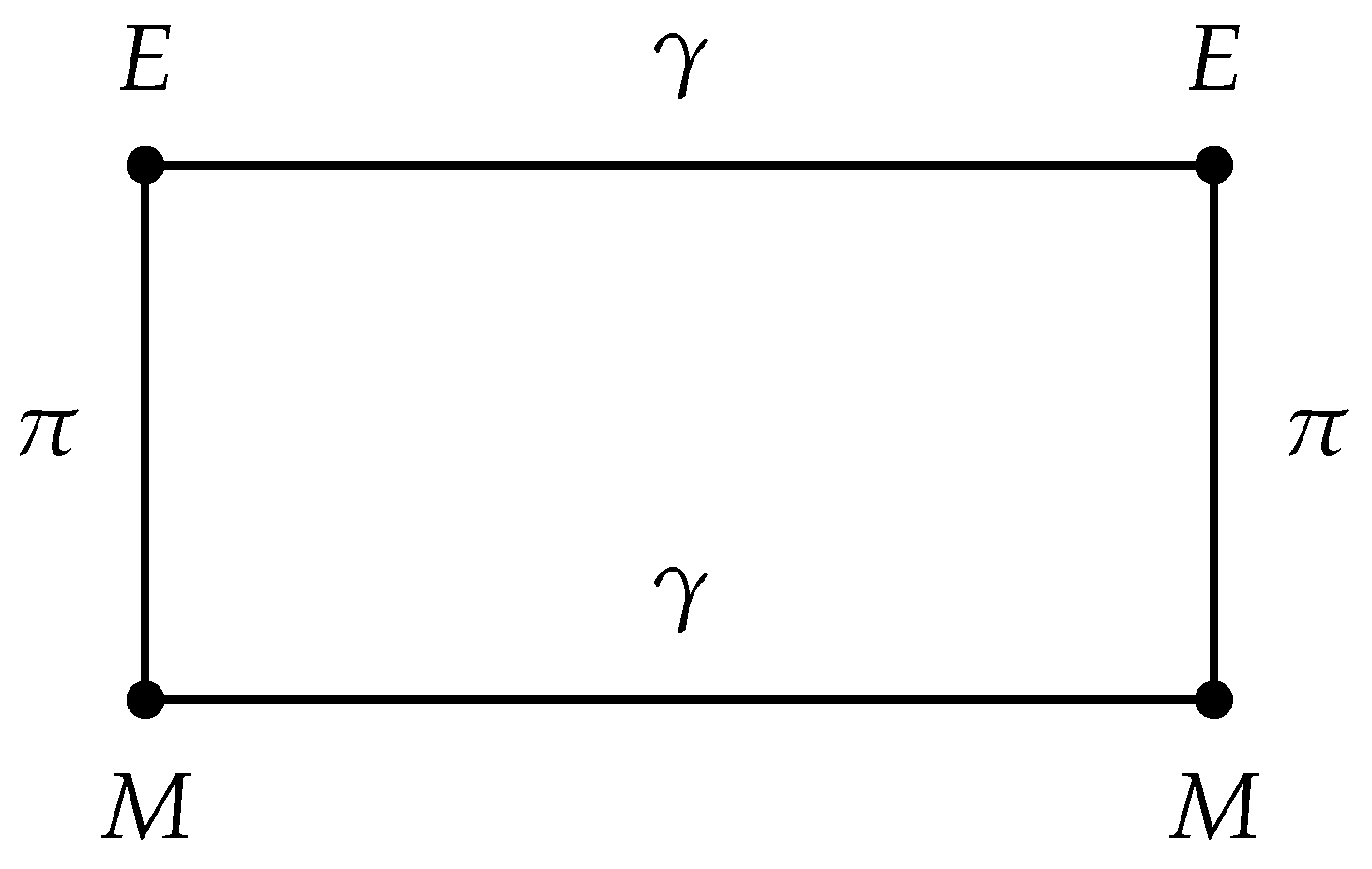

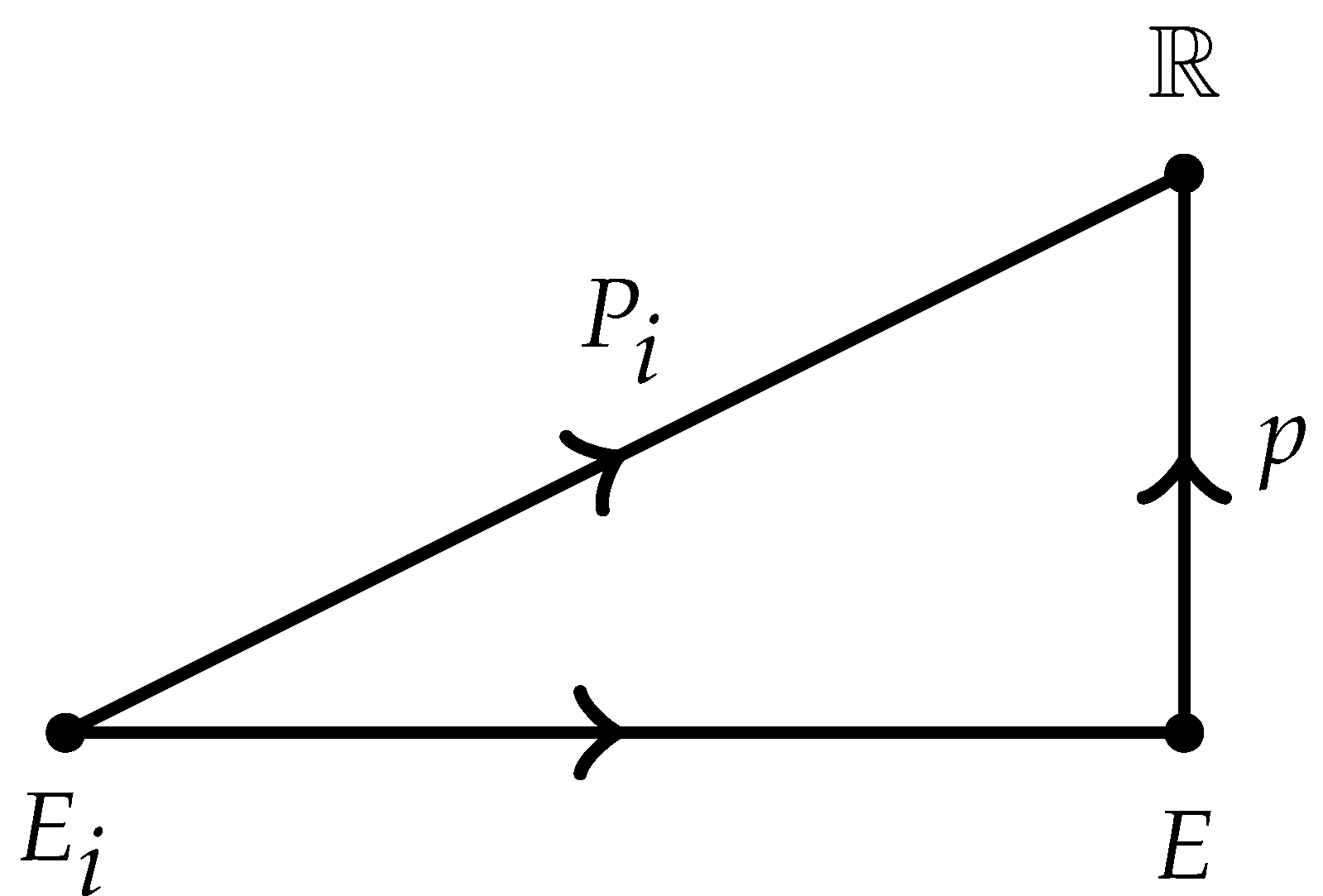

- (1)

- A statistical model is a locally trivial fiber bundle over a locally flat manifoldThe fibers of π are probability spaces.

- (2)

- The functoris called a -fibration.

8.3.5. Fisher Information in

- (1)

- g is positive semi-definite,

- (2)

- g is an invariant of the Γ-geometry in .

8.4. Exponential Models

- (1)

- The base manifold M supports a locally flat structure and a real valued function .

- (2)

- The total space supports a real valued random function a.

- (3)

- The triple is subject to the following requirement

- (4)

- (5)

8.4.1. The Entropy Flow

8.4.2. The Fisher Information as the Hessian of the Local Entropy Flow

8.4.3. The Amari-Chentsov Connections in

8.4.4. The Homological Nature of the Probability Density

8.4.5. Another Homological Nature of Entropy

9. The Moduli Space of the Statistical Models

The Hessian Functor

- (1)

- The category whose objects are gauge structures ,

- (2)

- The category whose objects are statistical models for measurable sets,

- (3)

- the category whose objects are manifolds equipped bilinear forms,

- (4)

- the category whose objects are functors

- (1)

- ,

- (2)

- (1)

- Let be the differential of ψ. For the image is defined byfor all vector fields .

- (2)

- It is clear that the datum is an object of the category . Then for vector fields in we calculate (at ) the right hand member of the following equalityDirect calculations yieldThus for all we have

- (i)

- Objects of are quintupletsThey are called statistical models for the measurable set

- (ii)

- Objects of are functorsThey are called -fibrations.

10. The Homological Statistical Models

10.1. The Cohomology Mapping of

10.2. An Interpretation of the Equivariant Class [Q]

10.3. Local Vanishing Theorems in the Category

- (1)

- A random function f has the property if

- (2)

- A random closed differential 1-form θ has the property if every has an open neighbourhood U satisfying the following conditions, support a random function f subject to two requirements:

- f has the property

- (3)

- An exact homological statistical model has property if there exists a random differential 1-form θ satisfying the following conditions

- θ has the property ,

- .

- (1)

- is locally exact.

- (2)

- (i)

- is differentiable with respect to θ,

- (ii)

- satisfies the following inequalities

- (iii)

- satifies the following identity

- (1)

- The category is a subcategory of the category

- (2)

- Ojects of but homological

- (1.1)

- The Information GEometry is the geometry of statistical models.

- (1.2)

- The Information topology is the topology of statistical models.

- (2.1)

- The homological nature of the Information Geometry.

- (2.2)

- What is a statistical model? The answer to the question raised by McCullagh should be: A statistical model is a Global Vanishing Theorem in the theory of homological models.

- (2.3)

- A local statistical model is a Local Vanishing Theorem in the theory of homological models.

11. The Homological Statistical Models and the Geometry of Koszul

- (1)

- The holomogical map leads to the functor of in the category of Hessian structures in

- (2)

- If M is compact then the subcategory of exact Hessian homological Exp-models is sent in the category of hyperbolic structure in in .

12. Examples

Stratified Analytic Riemannian Foliations

- (1)

- (2)

- .

- (a)

- does not depend on the choice of ∇,

- (b)

- is symmetric and positive semi-definite,

- (c)

- If X is a section of then

- (1)

- is a analytic submanifold of M.

- (2)

- defines a regular Riemannian foliation in ,

13. Highlighting Conclusions

13.1. Criticisms

13.2. Complexity

13.3. KV Homology and Localization

13.4. The Homological Nature of the Information Geometry

- (1)

- The Global Vanishing Theorem is the functor

- (2)

- The Local Vanishing Theorem is the functor

13.5. Homological Models and Hessian Geometry

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Affinely Flat Geometry

- (1)

- (2)

- the manifold M admits locally flat structures.

Appendix A.2. The Hessian Geometry

- (1)

- (2)

- the Riemannian manifold admits Hessian structures

- (i)

- is a locally flat manifold.

- (ii)

- every point has an open neighborhood U supporting a system of affine coordinate functions and a local smooth function such that

Appendix A.3. The Geometry of Koszul

- (1)

- (2)

- the KV cohomology space contains a metric class ,

- (3)

- the locally flat manifold admits Hessian structures

Appendix A.4. The Information Geometry

- (1)

- (2)

- is an exponential family.

- (1)

- (2)

Appendix A.5. The Differential Topology of a Riemannian Manifold

- (1)

- admits a geodesic flat Hessian foliation

- (2)

- The leaves of are the orbits of a bi-invariant affine Cartan-Lie group .

- (3)

- The bi-invariant affine Cartan-Lie group is generated by an effective infinitesimal action of a simply connected bi-invariant affine Lie group (

References

- Faraut, J.; Koranyi, A. Analysis on Symmetric Cones; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Koszul, J.-L. Déformation des connexions localement plates. Ann. Inst. Fourier 1968, 18, 103–114. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinberg, E.B. The theory of homogeneous convex cones. Trans. Moscow. Math. Soc. 1963, 12, 303–358. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresco, F. Geometric Theory of Heat from Souriau Lie Groups Thermodynamics and Koszul Geometry: Applications in Information Geometry. Entropy 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M.; Wolak, R. Foliations in affinely flat manifolds: Information Geometric. Science of Information. In Geometric Science of Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Gindikkin, S.G.; Pjateckii, I.I.; Vinerg, E.B. Homogeneous Kahler manifolds. In Geometry of Homogeneous Bounded Domains; Cremonese: Roma, Italy, 1968; pp. 3–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kaup, W. Hyperbolische komplexe Rume. Ann. Inst. Fourier 1968, 18, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszul, J.-L. Variété localement plate et convexité. Osaka J. Math. 1965, 2, 285–290. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M. The Cohomology of Koszul-Vinberg Algebras. Pac. J. Math. 2006, 225, 119–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M. Réductions Kahlériennes dans les groupes de Lie Résolubles et Applications. Osaka J. Math. 2010, 47, 237–283. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Shima, H. Homogeneous hessian manifolds. Ann. Inst. Fourier 1980, 30, 91–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vey, J. Une notion d’hyperbolicité sur les variétés localement plates. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1968, 266, 622–624. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresco, F. Information geometry of covariance matrix: Cartan-Siegel homogeneous bounded domains. Mostov/Berger fibration and Frechet median. In Matrix Information Geometry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 199–255. [Google Scholar]

- Baudot, P.; Bennequin, D. Topology forms of informations. AIP Conf. Proc. 2014, 1641, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gromov, M. In a Search for a Structure, Part I: On Entropy. Available online: www.ihes.fr/gromov/PDF/structure-serch-entropy-july5-2012.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2016).

- Gromov, M. On the structure of entropy. In Proceedings of the 34th International Workshop on Bayesian Inference and Maximum Entropy Methods in Science and Engineering MaxEnt 2014, Amboise, France, 21–26 September 2014.

- Amari, S.-I. Differential Geometry Methods in Statistics; Lecture Notes in Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, S.-I.; Nagaoka, H. Methods of Information Geometry, Translations of Mathemaical Monographs; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2007; Volume 191. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaudon, M.; Barbaresco, F.; Yan, L. Medians and Means in Riemannian Geometry: Existence, Uniqueness and Computation. In Matrix Information Geometry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 169–197. [Google Scholar]

- Armaudon, M.; Nielsen, F. Meadians and means in Fisher geometry. LMS J. Comput. Math. 2012, 15, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, O.E. Differential geometry and statistics: Some mathematical aspects. Indian J. Math. 1987, 29, 335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.K.; Rice, J.W. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. In Differential Geometry and Statistics; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993; Volume 48. [Google Scholar]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M.; Byande, P.M. KV cohomology in information geometry. In Matrix Information Geometry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, O.E. Information and Exponential Families in Stattistical Theory; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M.; Jamali, M.; Shahid, M.H. Multiply CR warped product Statistical submanifolds of holomorphic statistical space form. In Geometric Science of Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Milnor, J. The fundamental groups of complete affinely flat manifolds. Adv. Math. 1977, 25, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstenhaber, M. On deformations of Rings and Algebras. Ann. Math. 1964, 79, 59–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijenhuis, A. Sur une classe de propriétés communes à quelques types différents d’algèbres. Enseign. Math. 1968, 14, 225–277. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M.; Byande, P.M.; Ngakeu, F.; Wolak, R. KV Cohomology and diffrential geometry of locally flat manifolds. Information geometry. Afr. Diaspora J. Math. 2012, 14, 197–226. [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh, P. What is statistical model? Ann. Stat. 2002, 30, 1225–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudot, P.; Bennequim, D. The homological nature of Entropy. Entropy 2015, 17, 3253–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, G. On the cohomology groups of an associative algebra. Ann. Math. 1945, 46, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, G.; Serre, J.-P. Cohomology of Lie algebras. Ann. Math. 1953, 57, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleary, J. A User’s Guide to Spectral Sequences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eilenberg, S. Cohomology of space with operators group. Trans. Am. Math. Soc 1949, 65, 49–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszul, J.-L. Homologie des complexes de formes différentielles d’ordre supérieur. Ann. Sci. Ecole Norm. Super. 1974, 7, 139–153. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Kass, R.E.; Vos, P.W. Geometrical Foundations of Asymptotic Inference; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moerdijk, I.; Mrcun, J. Introduction to Foliations and Lie Groupoids; Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Molino, P. Riemannian, Foliations; Birkhauser: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, B.L. Foliations with bundle-like metrics. Ann. Math. 1959, 69, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akivis, M.; Goldberg, V.; Lychagin, V. Linearizability of d-webs, on two-dimensional manifolds. Sel. Math. 2004, 10, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifone, J.; Saab, J.; Zoltan, M. On the linearization of 3-webs. Nonlinear Anal. 2001, 47, 2643–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henaut, A. Sur la linéarisation des tissus de C2. Topology 1993, 32, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, H. Connectionson symplectic manifolds and geometric quantization. In Differential Geometry Methods in Maththematical Physics; Lectures Notes 836; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M. Structures localement plates dans certaines variétés symplectiques. Math. Scand. 1995, 76, 61–84. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamber, F.; Tondeur, P.H. De Rham-Hodge Theory for Riemannian foliations. Math. Ann. 1987, 277, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byande, P.M. De Structures Affines à la Géométrie de L’information; Éditions Universitaires Européennes: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2012. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Chentsov, N.N. Statistical Decision Rules and Optimal Inference; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, T.; Handal, J. Connections, Definite Forms and Four-Manifolds; Oxford Mathematcal Monograph, Oxford Science Publications; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin, V.; Sternberg, S. An algebraic model for transitive differential geometry. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1964, 70, 16–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, I.M.; Sternberg, S. The infinte groups and lie and Cartan. J. Anal. Math. Jerus. 1965, 15, 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- Shima, H. The Geometry of Hessian Structures; World Scientific: Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresco, F. Symplectic Structure of Information Geometry: Fisher Information and Euler-Poincare Equation of Souriau Lie Group Thermodynamics; Nielsen, F., Barbaresco, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 529–540. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzoe, H.; Henmi, M. Hessian Structures on Deformed Exponential Families; Nielsen, F., Barbaresco, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8085, pp. 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresco, F. Koszul Information Geometry and Souriau Geometric Temperature/Capacity of Lie Group Thermodynamics. Entropy 2014, 16, 4521–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijenhuis, A.; Richardson, W. Commutative algebra cohomology and deformation of Lie algebras and associative algebras. J. Algebra 1968, 9, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, E.; Barbaresco, F.; Angulo, J. Kernel Density Estimation on Siegel Space Applied to Radar Processing. Entropy 2016, 18, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, E.; Barbaresco, F.; Angulo, J. Probability density estimation on hyperbolic space applied to radar processing. In Geometric Science of Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 753–761. [Google Scholar]

- Eilenberg, S. Homology of spaces with operators group I. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1947, 62, 378–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguiffo Boyom, M.; Wolak, R. Transverse Hessian metrics information geometry. In Proceedings of the 34th International Workshop on Bayesian Inference and Maximum Entropy Methods in Science and Engineering, Amboise, France, 21–26 September 2014.

- Nguiffo Boyom, M.; Wolak, R.A. Transversely Hessian foliations and information geometry. Int. J. Math. 2016, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghib, A. On Gromov theory of rigid transformation groups, a dual approach. Ergod. Theorey Dyn. Syst. 2000, 20, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamber, F.; Tondeur, P.H. Invariant Operators and the Cohomology of Lie Algebra Sheaves; Memoirs of the American Matheamtical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpera, A.; Spencer, D. Lie Equation; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Guts, A.K.; (Omsk State University). Private communication.

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boyom, M.N. Foliations-Webs-Hessian Geometry-Information Geometry-Entropy and Cohomology. Entropy 2016, 18, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18120433

Boyom MN. Foliations-Webs-Hessian Geometry-Information Geometry-Entropy and Cohomology. Entropy. 2016; 18(12):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18120433

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoyom, Michel Nguiffo. 2016. "Foliations-Webs-Hessian Geometry-Information Geometry-Entropy and Cohomology" Entropy 18, no. 12: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18120433

APA StyleBoyom, M. N. (2016). Foliations-Webs-Hessian Geometry-Information Geometry-Entropy and Cohomology. Entropy, 18(12), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18120433