1. Introduction

Influencer marketing using social media influencers (SMIs) who have a large following to promote products and services has grown to be a 33-billion-dollar industry by 2025 [

1], with 54% of marketers reported boosting their spending on influencer marketing [

2]. Whether SMIs disclose their sponsorship properly has been a major concern for researchers and policy-makers alike because consumers have been shown to follow SMIs’ product endorsements as their trusted opinion leaders [

3]. Disclosure is an important transparency principle to reflect the compensation received by the influencer to endorse a product and activate the consumers’ persuasion knowledge of the persuasive intent of the influencer [

4,

5,

6].

Across the world, different countries have different regulations on sponsorship disclosure for SMIs [

7]. However, it is not known whether sponsorship disclosure practices are similar across countries with similar or dissimilar regulations; and how structural factors such as communication styles in contextual culture, legal system as proxy by linguistic cultures, and individual influencer factors such as motivation to create content, journalistic training, demographics, and content genre of influencers affect their disclosure practices. For marketers that want to use SMIs for multinational campaigns, such knowledge is essential to make their SMI partnership successful. Nonetheless, there are very few large-scale cross-national comparative studies of social media influencer brand endorsement and disclosure practices [

3]. Therefore, this global study examines the common factors possibly influencing ethical decision-making among social media influencers worldwide across cultural contexts. Specifically, the study has three main objectives: (1) investigate how structural factors including cultural context shape influencer ethical practices, (2) examine how influencer characteristics such as demographics, follower size, motivations to create content, and journalistic background affect disclosure, and (3) understand what influences ethical practices of influencers, including their attitudes toward problematic digital marketing practices. By examining the sponsorship disclosure beyond a simple binary transparency decision or compliance with government regulations, this study provides a holistic explanation of the diverse forms of sponsorship disclosure with both structural factors and individual factors. It aims to provide guidance for a globally applicable professional code of practices for the influencer marketing industry and regulation development.

In addition, our study hypotheses also test the long-held assumptions by researchers that the financial gain motivation of SMIs causes their tendency to hide the sponsorship, which is perceived to lower their credibility, and whether the information content genre and journalism training of SMIs would make them following journalistic standards and transparency principles.

Past research on influencer ethics focused on whether the influencer discloses sponsorships or not as a simple binary choice only [

8,

9,

10]. However, there are different forms of sponsorship disclosure such as using disclaimers only as simply fulfilling legal requirements or disclosing the sponsorship directly by mentioning about the sponsored product in the content to make sure audiences know the influencer is being compensated for promoting the product. These important differences were not recognized in past studies. In addition, there are other problematic digital marketing practices, such as using bots to boost the number of followers. This study covers these types of ethical problems in influencer marketing in addition to sponsorship disclosure to show an overall global picture of ethical practices of SMIs beyond a simple transparency theory of sponsorship disclosure ethics.

Originally, this study proposes a contextual–motivational global ethical practice framework using a mixed-methods study in explaining these influencers’ attitudes toward problematic digital marketing practices and sponsorship disclosure practices. The results show that influencers across countries have diverse disclosure practices, and cultural and motivational factors cannot account for the differences in practices in the survey results. The in-depth interviews revealed a complex balance between client expectation and influencers’ own aspiration in determining the disclosure practices. It further highlights the necessity of a comprehensive social media influencer sponsorship ethical framework that accommodates cultural diversity as well as fostering transparent and responsible content creation. This approach can facilitate content creators and brands to uphold accountability and consumer trust globally.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Transparency and Sponsorship Disclosure Practice in Influencer Marketing

The literature review aims to synthesize past studies in the following areas: (1) sponsorship disclosure practices and ethical implications, (2) structural factors that influence disclosure practices, and (3) individual characteristics that affect ethical practices and decision-making. Sponsored content is the incorporation of persuasive or brand messaging into media content in return for payment from sponsors [

9]. By incorporating advertising into non-commercial content produced by independent content creators, sponsored content presents ethical questions [

11]. The purpose of sponsorship disclosure is to let viewers know that the content is an advertisement [

12]. By activating an individual’s persuasion knowledge, sponsorship disclosure has been shown to be a successful strategy for making them mindful of the commercial and persuasive character of sponsored media content [

5].

Sponsorship disclosure is a very important practice and principled as an obligation for influencers. According to Wellman et al. [

13], the ethics of authenticity centers majorly on influencers being transparent with their audiences about partnerships that are paid. Authenticity and trust form the foundation of parasocial relationships, which affects the decisions that consumers make. When influencers do not disclose sponsorships, they risk damaging this trust, which will directly affect their credibility. They argue that being true to oneself and to one’s audience are the two main pillars upon which the ethics of authenticity are built.

Borchers and Enke [

14] believe that the followers see sponsored influencer content the same way they see organic content because of influencer industry ethics. Influencers usually use labels like “sponsored,” “advertising,” “collaboration,” or “thanks to [brand]” in their video content to show the audience that they have received sponsorship [

15]. Rozendaal et al. [

16] show that disclosing the sponsor in influencer videos helps audiences better recognize the commercialization of a video, which encourages audiences to process the video with a more critical view. Rozendaal et al. [

16] and Wellman et al. [

13] clearly stipulate that when sponsorships are clearly disclosed, viewers are more likely to recognize the commercial nature of the content, process the message critically as expected, and make informed decisions.

Leban et al. [

17] explores how high-net-worth social media influencers navigate the tension between ethicality and a luxurious lifestyle by endorsing personas that are very specific. Their study further draws on interviews and Instagram content to identify personas such as Ambassador of ‘True’ Luxury ‘Good’ Role Model, where influencers use to demonstrate being ethical while they show luxury consumption of the content. They found that these personas help the influencers to appear more responsible, further giving them the support to retain their legitimacy and to influence the audience perceptions on ethical luxury. It further underlines how important authenticity and transparency is in the relationship between influencers and their audiences.

Ethical considerations are very important in understanding sponsorship disclosure practices and influencer marketing. Bowen [

18] examined four social media cases to highlight both unethical behaviors and best practices in digital engagement. Through applying ethical theory and descriptive ethics to these cases, Bowen proposed fifteen useful guidelines to help public relations professionals navigate social media responsibly. These guidelines also highlight the importance of honesty, transparency, and accountability in digital communication values that openly inform sponsorship that has ethical disclosures and help ensure that influencer practices maintain audience trust in different platforms and cultural contexts.

Sierra et al. [

19] found that perceived ethicality directly impacts customer trust positively and brand affect. The study further highlights the importance of ethical behavior not only at the corporate level but among influencers at an individual level whose brands are tangled to their personal image.

According to Shah et al. [

20], only algorithmic transparency is not sufficient for building user trust. Their study shows that unethical data collection practices significantly decrease users’ comfort, trust, and acceptance of algorithms, even when the algorithms are transparent.

Nonetheless, influencers use different methods to disclose sponsorships. There are four common approaches influencers disclose sponsorships: explicit sponsorship disclosure, concealing disclosure, impartiality disclosure, and no disclosure [

15]. From a marketer’s point of view, the best practice is to have influencers honestly promote products and use fair disclosure. This is because audiences are more likely to believe the influencer’s recommendation is sincere. From the influencer’s perspective, disclosing sponsorship helps increase their credibility. If influencers inform their audience through sponsorship disclosure, it increases the transparency of their content. This transparency can enhance the audiences’ trust in the influencer, as it makes the influencer more attractive.

However, different countries and platforms may have specific disclosure requirements. Hence, by carrying out a global study comparing the sponsorship disclosure practices, we can examine how structural and individual factors can influence sponsorship disclosure practices.

2.2. Structural Factors Influencing Sponsorship Disclosure Practices

This global study of content creators first investigates if there are structural factors that affect the disclosure practices.

2.2.1. Cultural Context Theory

Edward Hall proposed the cultural context theory to explain how cultures communicate differently by differentiating cultures into high and low contexts [

21]. High-context cultures are characterized by implicit communication and meaning of messages embedded within the context, nonverbal cues, and an overall shared cultural understanding. A high-context (HC) communication or message is one in which “most of the information is either in the physical context or internalized in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message” [

21]. Moreover, people in this culture rely on more indirect communication.

Within low-context cultures, information is conveyed through verbal language and emphasizes direct and explicit communication. A low-context (LC) communication is just the opposite of high-context, i.e., “the mass of the information is vested in the explicit code” [

21]. Low-context cultures communicate with more straightforward rather than implied meanings. Additionally, low-context cultures rely less on nonverbal signals and more on direct messages. Within low-context cultures, information is conveyed through verbal language and emphasizes direct and explicit communication. Countries that are categorized as high-context include Asian, Middle Eastern, and some Southern European cultures. For the defined variables of this study, this includes the following languages: Chinese, Russian, and Arabic.

Countries that are classified as low-context include Northern European, North American, and Germanic cultures. For the defined variables of the study, this includes the following languages: English, French, German, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Influencers in high-context cultures should be more likely to use more implicit disclosure techniques, which aligns with their broader communication styles. This cultural influence can lead to variation in how influencers from different regions interpret and apply disclosure. Hence, this study poses the following question:

At the same time, Hall’s [

21] high–low-context distinction has been critiqued for essentializing cultures and treating communication styles as fixed properties of national groups rather than historically contingent practices [

22]. To avoid mixing communication style with institutional context, in this study we treat “culture” in two analytically distinct ways: culture as a set of interactional norms (e.g., expectations of directness) and culture as a regulatory and market environment that structures what kinds of disclosure are incentivized.

In addition, in his theory of the sociology of nations, Pickel [

23] purports that national cultures are intimately tied to natural languages, and that “the acquisition of a national culture occurs as part and parcel of the acquisition of a natural language.” If sponsorship disclosure is closely related to cultures and the language is a proxy of a national culture, influencers in countries of different languages will show differences in sponsorship disclosure practices with different regulatory tradition and market environment. Hence, we ask the following question:

2.2.2. Economic Development of the Country of the Influencer

As digital platforms expand worldwide, content creation has become a powerful force in both the Global North and Global South, shaping public opinion and consumer behavior. The Global North and Global South are terms used to describe the differences in wealth and power between countries. The United Nations often uses the Global North–Global South system in a similar way to the more- and less-developed countries system. The Global North includes the United States, Canada, Europe, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel. The Global South includes Latin America, Africa, the Middle East (except Israel), and most of Asia and Oceania. This system mainly separates richer and poorer countries based on history. It does not follow the actual north–south division of the world [

24]. Apart from economic development differences, the legal infrastructure in Global South is not strong or unclear so the rules may be unclear to creators there to do disclosure and realize problematic digital marketing practices.

Ortova, Hejlova, and Weiss [

25] highlight how regional disparities in legal frameworks directly contribute to differences in influencer marketing. Unclear advertising regulations frequently result in inconsistent disclosure practices in the Global South such as the Czech Republic. Influencers in these regions may lack the awareness, training, or support by institutions necessary to apply ethical standards constantly, even when their audiences expect transparency. This legal setting can affect not only how sponsorships are disclosed but also how influencers perceive their ethical responsibilities, especially as their influence over public opinion grows.

Followers trust influencers’ opinions even when they know a post is sponsored. They expect influencers to be honest and independent, even when working with brands. Because of this trust, influencers may not feel the need to treat sponsored content differently from regular content. The Global North typically is characterized by good infrastructure and established legal systems, especially in business ethics, while the Global South has poorer infrastructure and less comprehensive business laws and corporate social responsibility standards [

26]. This raises important questions about the ethical responsibilities of content creators in both the Global North and Global South, especially as their influence grows and the lines between genuine content and paid promotions become increasingly blurred while laws have not kept up to the latest development in influencer marketing. To explore the comparative global ethical practices, we proposed the following research question based on the economic development status of the influencer’s country:

2.3. Individual Attributes of Influencers

We also examine the key creator individual attribute factors that may influence creators’ ethical practices.

2.3.1. Influencer Demographics

Influencer attributes, such as gender, age, education, and experience in content creation, may affect the attitudes toward disclosure and problematic digital marketing practices. The past literature on influencers shows these different demographic factors influence their behaviors. Hudders and Jans [

27] investigated how influencers’ gender influences the persuasiveness of sponsored content. They found there is no significant effect of the influencers’ gender for participants, but female participants engage more with female influencers due to greater perceived similarity and parasocial interaction, which positively affect brand attitude and engagement, but male participants are not influenced by gender of the followers. In addition, Al-Shehri’s mixed-methods study examines the impact of social influencers’ gender and age on consumer purchasing decisions [

28]. The results showed that consumers tend to prefer social influencers of the same gender, with women preferring female social influencers and men preferring male social influencers. However, the age of the social influencers has little impact on consumer purchasing decisions.

There is no published research to the best of our knowledge on whether influencers’ educational background and experience in content creation is related to how they disclose sponsorship in their posts. Hence, in this study, we ask the following question:

RQ3: What influencer attributes (age, gender, education, experience in content creation) affect sponsorship disclosure practices and attitudes toward problematic digital marketing practices?

2.3.2. The Follower Size of Influencers

Influencers are commonly categorized based on the number of followers in the industry, which is vital in establishing their impact, engagement rates, how credible they are, and their marketing potential. According to Campbell and Farrell [

29], nano-influencers are at the start of their careers and have a followership of 1 K to 10 K people. They are less expensive, and their audiences mostly include friends, family, and acquaintances, making them more engaging compared to other types of influencers. They are seen as authentic and trustworthy as evident by their close connections with their followers. Micro-influencers have 10 k to 100 k followers and are seen as rising stars. They are more accessible to organizations and brands and are used for targeted marketing and credibility [

30]. Macro-influencers are domain influencers with 100 k to 1 million followers but are yet to achieve celebrity status. These influencers have lower engagement rates than nano- and micro-influencers; however, they provide greater exposure. Mega-influencers are influencers with over one million followers. They are high profile celebrities and can be athletes and public figures, they work with big brands and a multinational campaign [

31]. Due to their vast number of followers, they have low engagement with their audiences.

Micro-influencers have higher perceived authenticity than macro-influencers and studies show that micro-influencers maintain a closer relationship with their audiences, leading to more engagement, connection, and trust than macro-influencers [

29]. With this dynamic, they may end up upholding high ethical standards, including clear disclosure of contents that are sponsored and are also responsible for communication of any information shared with their target audience.

Macro-influencers and celebrity influencers have greater commercial pressures, causing ethical compromises [

29]. Martínez-López et al. [

32] found that larger influencers may engage in misleading advertising, fail to disclose sponsorship, and have less accountability due to the nature of dispersed followers they have. However, influencers who have many followers rely on their reputation to build trust and may prefer to look authentic and honest to their followers. Hence, it is important to know if the follower size of the influencer can be an individual factor that affects their disclosure practices.

2.3.3. Influencer Motivations

Moral Utility Theory uses expected utility maximization to explain unethical decision-making [

33]. It implies that unethical behavior occurs when expected benefits surpass those of moral activity, frequently because of quicker ways to achieve objectives. The theory, which has its roots in the subjective expected utility (SEU) principle, argues that people make decisions based on what will maximize their own monetary value or satisfaction. As utility value is derived from the influencer’s content creation motivation, their money-making motivation and reliance on the income from sponsored content should influence their content and sponsorship disclosure; we have the following hypotheses:

H1a. Those influencers with digital content creation as their primary source of income are less likely to disclose their sponsorship than those whose content creation is not their primary source of income.

H1b. Those influencers whose primary reason for creating content is to make money are less likely to disclose their sponsorship than those whose primary reason for content creation is not to make money.

2.3.4. The Content Genre of Influencers

Social media influencers may struggle with the transparency paradoxes of disclosure [

34]. Research has found that consumers expect SMIs to be honest about their brand sponsorships in their posts [

35], and honest sponsorship disclosure enhances the perceived credibility of the influencer if the recommendation is genuine [

36]. Contrarily, others argue that disclosure of a commercial sponsorship reduces the perceived authenticity of the influencer because they are expected to inspire their followers instead of sharing content with a material interest [

30]. However, there seems to be a gap in examining how an influencer’s content genre, such as entertainment versus information-based content, influences their sponsorship disclosure behaviors.

Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) has been used to study users’ motivation to consume different types of SMI content [

37]. Entertainment content such as music, humor, and comics is seen as less serious [

36]. Hence, influencers of entertainment content might be concerned that explicitly disclosing brand sponsorship will diminish their authenticity and goodwill toward their followers [

38]. As a result, to maintain authenticity, influencers embed endorsements into personal stories and present experiences naturally almost like without sponsorship [

30,

39]. On the other hand, informational genre influencers are expected to uphold truthfulness. Sponsorship disclosure is part of their ethical responsibility ensuring credibility [

40]. Therefore, we propose the following:

H2. Influencers in entertainment content genres are (a) less likely to disclose sponsorship and (b) more accepting of problematic digital marketing practices than influencers in information content genres.

2.3.5. Journalism Training/Background

Prior research comparing influencers who lack formal training and journalists found journalists are more likely to uphold higher ethical standards [

13]. There are several ethical codes that journalists adhere to, including those outlined by the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) and UNESCO’s principles on media ethics, which include avoiding conflicts of interest and disclosing sponsorships. The ethical decision-making process for influencers, however, is fluid and context-dependent because they operate in a space with fewer regulatory oversights. Navarro et al. [

41] highlight that PR professionals often face challenges in working with influencers because they follow varying ethical standards rather than a strict code of conduct.

Studies on sponsorship disclosure highlight these differences. Boerman [

9] found that influencers often struggle with transparency in sponsored content, as their financial incentives can conflict with disclosure. Influencers with journalism backgrounds, however, are more likely to recognize disclosure as an ethical obligation rather than just being legally required [

4]. With the past literature explaining how journalists differ from influencers in ethical standards, we expect influencers with journalism backgrounds should more likely be disclosing their sponsorship to build credibility and oppose problematic digital marketing practices:

H3. Social media influencers with a journalism background are more likely to (a) disclose their sponsorship and (b) less likely to support problematic digital marketing practices than influencers without a journalism background.

3. Research Methods

Using an explanatory sequential mixed-methods approach [

42], the researchers conducted a global eight-language online survey of 500 social media influencers ranging from nano-influencers with 1000–10,000 followers, to mega-influencers with more than one million followers and in-depth interviews of 20 influencers. The research examines how social media influencers deal with ethical dilemmas like balancing authenticity with sponsorship commitment and support of problematic digital marketing practices.

The country selection of this anonymous global survey of social media influencers was based on language and economic development (Global South and Global North) [

24] to be as inclusive as possible for all major cultures in the world. As English is the most common second language with the widest reach, English-speaking countries were allocated a larger sample size. The questionnaire was first developed in English and then was translated into seven other major languages (Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish) by professional translators and checked by native communication scholars of each language. A quota sample for each language region was used to represent the content creation in the world with the following breakdown: 100 influencers in the English-speaking Global North including the US, UK, Canada, Singapore, Australia, and Ireland; 50 influencers in the English-Speaking Global South including India, South Africa, Nigeria, the Pacific islands, and Southeast Asian countries; 50 influencers in French-speaking countries including France and French-speaking African countries and Pacific islands; 50 influencers in Spain and Spanish-speaking Latin America; 50 influencers in Portugal and Portuguese-speaking Brazil; 50 influencers in German-speaking countries—Germany, Switzerland, Austria; 50 influencers in Russia and Russian-speaking East European countries; 50 influencers in China and Chinese special administrative territories; and 50 influencers in Arabic-speaking Middle East and North African (MENA) region.

The cross-national online survey company, Qualtrics, was employed to survey their worldwide panel. The participants must be content creators who have 1000 or more followers and create public content on social media on a regular basis. Those who were eligible for the study received compensation from Qualtrics based on its standard compensation scheme. To ensure equal gender participation, a 50/50 quota has been set for the Qualtrics survey. The survey data collected shows that 52.4% of the influencers in this study came from the Global South countries. The online survey was totally anonymous. Participants came from 44 countries across six continents (See

Appendix A for detailed country breakdown). In addition to the Qualtrics panel which contains no user contact information, another 217 influencers were recruited as survey participants from journalist associations, UNESCO social media posts, as well as the researchers’ own network. A total of 66 of these survey participants expressed interest in participating in the follow-up interviews and provided valid contact information. Balancing equal proportion of males and females, size of followers, and Global North and Global South, 20 were selected to participate in the interviews to explain their ethical dilemma experiences and challenges encountered as influencers.

Participants were invited by the 15 trained interviewers who had been certified for Human Subjects research in one of the five languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, Portuguese, and Spanish). The interviews were conducted on Zoom in the interviewee’s preferred language during September and October 2024. The interviews lasted 30 min to 75 min. Participants received the interview questions in advance, before giving consent to the interview. They signed a written consent form or indicated their oral consent during the recorded interview. The interviews were subsequently transcribed and translated into English if they were not conducted in English. The interview guide was developed by the research team and consisted of 25 open-ended questions and was translated into the five other language versions by professional translators. All interviewers read the survey responses of the participant prior to the interview to understand their background and merged the information in the interview transcript. Participants received a $50 Amazon gift card or equivalent wire transfer after completion of interview. All interviewees except one preferred to use their real names in our research report.

All interview transcriptions were then analyzed using a thematic analysis approach to focus on the reasoning behind disclosure method choice and disclosure practices. The process allowed the researchers to identify cross-cutting themes and to link individual narratives to quantitative patterns in the survey data to ensure the rigor of the qualitative component.

3.1. Survey Measures

3.1.1. Sponsorship Disclosure

In contrast to past sponsorship literature that concerned whether the influencer disclose the sponsorship or not, we focus on the type of disclosure they used and allowed respondents to choose more than one type of disclosure: (1) clearly disclose such collaborations to your audience in the content, (2) use disclaimer labels such as “sponsored content” or “brand partnership,” (3) I only do sponsored content or partnership for brand that I used as a consumer and tell the audience as such, (4) create the content as if it is not sponsored content to the audience with no disclosure of sponsorship. To ensure valid answers, only those who had created sponsored content were asked this question.

Each type of disclosure reflects different values: reminding the audience the product is sponsored in the content is one of the most direct ways of disclosure and the audience should notice the sponsorship. Putting a disclaimer that the product is sponsored but not in the post is more about compliance to the standards or regulations. Audiences who did not read text below the post carefully may overlook the disclaimer and not know that it is sponsored content. Telling the audiences they use the products themselves can show authenticity in selecting the sponsored products and make the endorsement genuine. Pretending the content is not sponsored shows that the influencer does not want the audience to know the content is sponsored.

3.1.2. Problematic Digital Marketing Practices

This study examines five problematic digital marketing practices that artificially increase traffic flow of the content [

43]: (1) IP cloaking: showing different content to search engine than what is shown to users, (2) user agent clocking: serving different content to different browsers, (3) referrer cloaking: leading visitors into thinking that they are visiting a legitimate site when in fact they are being redirected to a different website, (4) using bots to increase numbers of followers and views. We asked respondents on a 5-point rating scale how much they support or oppose these practices, from strongly support (1) to strongly oppose (5). The higher the value, the more opposition to the practices. All influencer respondents answered this question.

3.2. Structural Factors

3.2.1. Linguistic Culture

The eight languages we used in the survey served as the designation of linguistic culture: Arabic, Chinese, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish, and Russian.

3.2.2. Cultural Context

We used Hall’s [

21] designation of high- and low-context culture. All European countries, North American, and Australasia countries were designated as low-context cultures. Chinese, Arabic, and Russian-speaking countries were coded as high-context cultures.

3.2.3. Economic Development

Global South and Global North countries are defined based on UNESCO’s Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World’s designation [

44]. All South American, African, China, Southeastern Asian, and South Asian countries, including BRICS, were classified as Global South.

3.3. Individual Factors

3.3.1. Demographics

Age and education were measured in standard intervals. Gender was measured as male, female, or self-described. Years of content creation experience was measured in intervals of (1) less than one year, (2) 1–3 years, (3) more than 3 years but less than 10 years to (4) more than 10 years.

3.3.2. Follower Size

Four intervals from 1 to 10 K (nano-influencers), 10 K–100 K (micro-influencers), 100 K to 1 million (meso-influencers), more than 1 million (mega-influencers) were used.

3.3.3. Motivation to Create Content

We asked the participants whether content creation is the primary source of income and their primary motivation in creating their public content: one of choices was making money. Those who selected making money as the primary motivation would count as money-making (financial gain) motivation. Those who did not choose making money as their primary motivation were counted as having non-money-making motivation.

3.3.4. Content Genre

A total of 11 types of content and an additional “other” multiple response categories were provided to respondents to allow for creators creating more than one kind of content: sports and fitness, gaming, comedy, beauty, fashion/life-style, parenting, animal and nature, photography, travel and food, shopping/product reviews, current affairs/politics and economy. These content genres are the most used in influencer marketing according to the Influencer Marketing Hub [

45]. To facilitate the analysis, we grouped the influencer genre into entertainment (sports and fitness, gaming, comedy, beauty, fashion/life-style, parenting, animal and nature, photography, travel and food), information (shopping/product reviews, current affairs/politics and economy), and mixed (those that create both types of content).

3.3.5. Journalistic Background

Journalistic background includes either professional journalist experience or having journalism training/education. Respondents were asked if they have a journalism background or not with a yes/no answer.

3.4. Interview Questions

In the interview protocol, we have the following three sets of questions related to influencers’ sponsorship disclosure practices and ethical dilemmas:

“Do you think digital content creators should follow an ethical code? If so, what principles should be included? How about disclosure of sponsorship? Do you think it will lower your credibility or effectiveness of the sponsorship?”

“How can digital content creators have more accountability of their content to build trust of the audience?”

“Can you tell us any ethical dilemmas that you encountered as a content creator? How did you make the decisions and feel good about it? If none, how about a hypothetical scenario such as the sponsor/news organization for journalist asks the content creator to write/show negative things about a competitor or review positively about a product of the sponsor without disclosing it to the audience?”

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Influencer Respondents

Among the 500 creators we surveyed using the Qualtrics panel, 52.8% are 18–35 years old, 68% of them are nano-influencers (1 K to 10 K followers), and slightly more than half (52.2%) are from the Global South. More than one-third (35.2%) reported encountering ethical dilemmas during content creation. Slightly above half of them (52.6%) reported creating sponsored content/endorsing products. Those who create sponsored content are twice (47.9%) more likely to encounter ethical dilemmas than those who do not (21%). Less than one-third of them (31.4%) reported content creation as their primary source of income.

It should be noted that in cross-tabulations we only presented the row percentage (percentage in group category) to identify the likelihood of occurrence of the specific disclosure practice for comparison, so the table percentages in the cells do not add up to 100%.

4.2. Influence of Cultural Context on Sponsorship Disclosure Practices

First, we examined if high and low context cultures affect the disclosure practice of creators. We found no significant difference between creators of high- and low-context cultures across the four types of disclosure practices. We then examined whether there are any significant differences between the linguistic cultures in the sponsorship disclosure practices. We found there are statistically significant differences among creators of different linguistic cultures (See

Table 1). French-speaking creators (71%) are the most likely to directly disclose the brand collaboration to their audiences in the posts/videos, while the Chinese creators are the least likely to clearly disclose such brand collaboration in the content (24.1%), (χ

2= 18.86, df = 7,

p = 0.009). But, in terms of ritualistic, law-conforming disclosure using disclaimer labels such as “sponsored content” or “brand partnership,” posted under the post, Chinese content creators (72.4%) are the most likely to use this form of disclosure, while Russian content creators are least likely to use such form of disclosure (41.9%) (χ

2 = 15.726, df = 7,

p = 0.028). However, there are no significant differences between linguistic cultures in performing sponsored content that the creator actually used as a consumer and tell the audience as such (χ

2 = 6.682, df = 7,

p = 0.463) and create the content as if it is not sponsored content with no disclosure of sponsorship (χ

2 = 6.471, df = 7,

p = 0.486).

4.3. Economic Development and Ethical Practices

Although Global North creators are slightly more likely to disclose sponsorship and are more likely to hide the sponsorship than Global South creators, there is no statistically significant difference between creators’ sponsorship disclosure practice by economic development. However, in terms of problematic digital marketing practices, Global North creators show stronger opposition to the referrer cloaking practices of misleading and directing users to another site than Global South creators (MGN = 3.29, MGS = 3.03, t = −2.045, p < 0.05). For other problematic digital marketing practices, they are ambivalent to IP cloaking and user agent clocking. Both Global South and Global North creators are neutral to somewhat opposing using bots to increase the number of followers and views.

4.4. Demographic Attributes of Creators and Ethical Practices

Across the four demographic attributes of creator, age, gender, education level, and experience in creating content, we found no significant differences in their sponsorship disclosure practices and attitudes toward problematic digital marketing.

4.5. Follower Size and Ethical Practices

Due to the much higher number of nano-influencers with less than 10 K followers and very low number of macro- and mega-influencers in the sample, we combined the creators with 10 K or more followers as one group instead of separating the micro-, macro-, and mega-influencers for statistical analyses. Our survey of creators shows that creators with larger follower size are significantly more likely to disclose brand collaborations and use disclaimer labels than creators with smaller follower size. As shown in

Table 2, those with 10 K or more followers (36.3%) are two times more likely to clearly disclose their brand collaborations to their audience than those with less than 10 K followers (18.3%). (χ

2 = 18.625, df = 1,

p < 0.001). Almost 40% of the creators with 10 K or more followers will use disclaimer labels for sponsorship, but only slightly more than a quarter (27%) of creators with less than 10 k followers will use disclaimer labels and the difference is significant (χ

2 = 6.607, df = 1,

p < 0.01). Performing sponsored content for only brands they use are less common among the creators (less than 20% for both creators with less than 10 K or more than 10 K followers) and, even rarer (less than 10%), do they totally not disclose any sponsorship and pretend they are unsponsored content.

4.6. Influencers’ Content Creation Motivation and Disclosure Practice

Based on motivation theory, we hypothesized H1a that those influencers with digital content creation as their primary source of income are less likely to disclose sponsorship than those whose content creation is not their primary source of income. However, our survey data show that sponsorship disclosure is not related to whether digital content creation is the primary income of the influencers. Thus, H1a is rejected.

Yet, our H1b, which posited that those influencers whose primary reason for creating content is to make money are less likely to disclose sponsorship than those whose content creation primary motivation is not making money, is partially supported. Those whose primary motivation to create content is not making money are almost two times (34.1%) more likely to report selecting only brands that they actually use and tell audiences as such than those whose primary motivation to create content is to make money (18.1%) (χ

2 = 6.518, df = 1,

p = 0.011). However, this money-making motivation in creating content does not affect the sponsorship disclosure of mentioning directly in the post or using a disclaimer. See

Table 3. Hence, this hypothesis is partially supported in one disclosure practice, but not the other three disclosure types.

4.7. Impact of Content Genre on Ethical Practices

H2 posited that influencers in entertainment content genres are (a) less open to sponsorship disclosure and (b) more supportive of problematic digital marketing practices than influencers in information content genres including product reviews. Based on the results, we rejected our hypothesis. There are statistically significant differences between influencers in the entertainment content genres and information or mixed content genres. But contrary to our expectation, entertainment content genre influencers, in fact, are more likely to directly disclose sponsorship than their information content genre counterparts. Relatively speaking, mixed genre influencers (31.3%) are most likely to disclose their sponsorship directly in their content (χ

2 = 7.344, df = 2,

p = 0.025). But, for the other disclosure practices, there are no statistically significant differences, although the pattern persists that mixed genre influencers are more likely to disclose brand sponsorship to their audiences. See

Table 4.

In terms of support of problematic digital marketing practices, there are no significant differences between entertainment and information content genre influencers. There is slightly higher opposition to the use of bots to boost the number of views and followers by information content genre than entertainment content genres influencers, but the difference is only marginally significant (Minfo = 3.62, Mentertain = 3.22, t = 1.81, p = 0.07).

4.8. Impact of Journalistic Background on Ethical Practices

Our H3a hypothesized social media influencers with a journalism background are more likely to disclose sponsorship than those without a journalism background. But the data did not support it. On the contrary, those without a journalism background are slightly more likely to disclose it directly on the post, 49.2%, than those with a journalism background (37%) (χ

2 = 3.168, df = 1,

p = 0.075), although the difference is marginally significant. Yet, those with a journalism background are more likely to use disclaimer labels to conform with legal requirements, although there is no statistical significance in the difference. There is no difference selecting products they actually use or not for influencers with and without a journalism background. See

Table 5.

Our H3b expected that creators with journalism backgrounds are more likely to oppose problematic digital marketing practices. But, the results did not show significant differences between the two groups on cloaking practices. Even the use of bots is slightly more supported by social media influencers with a journalism background (M = 3.04) rather than those without a journalism background (M = 3.37) (t = 2.246, df = 1, p = 0.025). The hypothesis is rejected.

5. Interview Results

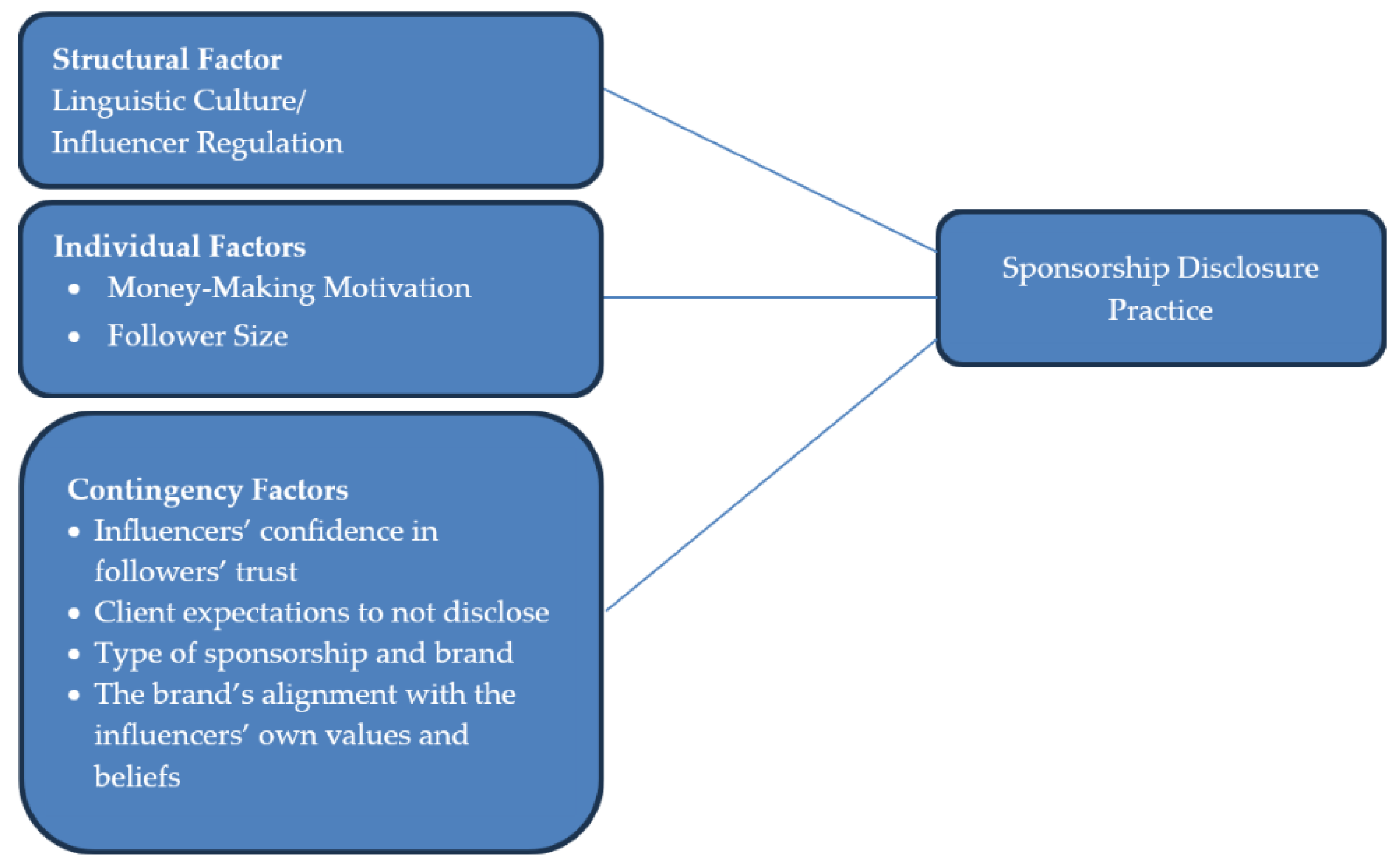

To understand why most of the structural factors and individual factors we postulated are not correlated with their disclosure practices, we asked the 20 interviewees in the in-depth interviews what they considered in making those disclosure practice decisions. The results are revealing, and we identified four themes: (1) alignment with the influencers’ own values and beliefs, (2) the confidence influencers have about their followers’ trust in them, (3) the type of brand that they sponsored, and (4) the client’s expectation of disclosure influenced their sponsorship disclosure choices. We can call these contingency factors that ultimately affect the influencer’s decision on how to disclose their brand sponsorship. All influencers included in these interview quotes preferred to disclose their own names and hence their real names were used in the results.

Across these themes, power asymmetries between clients and influencers emerged as a common thread where creators frequently described themselves as needing to accommodate brand expectations and terms, even when these clashed with their preferred disclosure practices.

For example, Mia Davila Romero from Peru, with 2300 followers on Instagram, said, “If it’s not aligned with the theme or value I follow, I wouldn’t promote it.” Sabeha Almas (Burka Journalist), with 31 K followers on Facebook, emphasizes that influencers taking sponsorship from products not good for audiences must disclose the sponsorship: “People get sponsorships for things which are not good for the audiences…at least let people know that you are taking money for this thing. I think. If you are afraid of things like these you should not take such sponsorships which are not good for people, always go for those things which are in the long term good for you and your audience.”

Ojo Omotayo, a male influencer in Ireland with 19 K followers, said the type of sponsorship and brand is important for his disclosure decision: “As for disclosing sponsorship in my videos, it depends on the type of sponsorship and the brand behind it. I don’t think it would necessarily lower my credibility or effectiveness, but again, it depends on the brand involved.” There are also influencers that do not worry that sponsorship disclosure will lower the effectiveness of endorsement, showing their confidence in themselves, such as Marvin Balasabas from the Philippines, with 71.4 K followers: “There is nothing wrong with disclosure. I’m okay with disclosing if it’s a paid partnership with the brand. I don’t think it will lower the effectiveness of the post while mentioning the brand’s name.”

There are also situations where the influencers themselves do not mind sponsorship disclosure, but their clients do not want the disclosure, such as Zhang, Zhaoyuan in China, with one million followers: “It’s simply that the client doesn’t want people to have that impression. The client just doesn’t want the audience to think the content was only created because money was involved. I never mind people knowing it’s an ad, because my principle for accepting endorsements is that the product must be worth promoting in the first place.”

Some influencers also believe whether the sponsorship is explicitly disclosed will not affect the perception of consumers as they believe consumers were assumed to be able to tell the sponsorship themselves such as Ma, Chenze, an automotive influencer on the Weibo platform in China, with 200 K followers, “I don’t think whether I say it’s an ad (sponsored) or not really affects anything. It’s just about breaking that unspoken understanding. In my opinion, saying it’s an ad (sponsored) doesn’t really have an impact. I think this is more of a cultural issue, tied to the subtlety of Chinese people. We’re often reluctant to directly say or describe certain things, similar to how certain topics are avoided at weddings—it’s that kind of feeling…everyone already knows it’s an ad anyway. It might feel awkward to say it outright.”

These examples also corroborated our quantitative survey findings that Chinese influencers are the least likely to disclose sponsorships directly in the post.

Together, the interviews indicate that disclosure is mostly negotiated within unequal relationships in which brands and agencies retain greater leverage over how transparent collaborations are framed.

Figure 1 summarizes our findings regarding the factors that influence sponsorship disclosure practice of social media influencers.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The study aimed to create a deeper understanding of factors influencing social media influencers’ ethical practices and decision-making, specifically, looking into sponsorship disclosure and problematic digital marketing strategies. The diverse use of more than one sponsorship disclosure form in our study shows that many influencers see disclosure as essential in maintaining their content creation careers with endorsement/sponsored content [

13]. However, different from previous studies that only examine whether influencers disclose or undisclosed the sponsorship [

8,

12], we demonstrated that some influencers choose more than one way to disclose the sponsorship. Sponsorship disclosure has become the norm for creators as very few of our anonymous survey respondents did not disclose sponsorship in any form and pretend it is not sponsored. Yet, the fact that only about half admitted they have ethical dilemmas means another half did not think there are any ethical issues they encountered. It remains unclear whether this reflects a lack of awareness or sensitivity, or the presence of effective coping strategies, and warrants further study.

The large differences we observe across linguistic groups in direct sponsorship disclosure appear to be driven less by deep-seated communication styles and more by differences in regulatory and market environments. The lack of association between Hall’s [

21] high–low-context classification and disclosure behavior reinforces critiques that treat high–low context as an essentializing cultural shorthand and cautions against equating “culture” with communication style alone. In our data, linguistic groupings often map onto shared legal frameworks (with colonial legacy) and platform governance regimes, which more plausibly account for the divergence between, for example, French and Chinese-speaking creators. While almost three-quarters of French-speaking creators chose to directly disclose their brand sponsorship in the content, not using disclaimers, three quarters of Chinese-speaking creators chose using only disclaimers and the English-speaking creators are a close-second in disclaimer use. The market regulation and the maturity of influencer marketing industry in those linguistic markets rather than the cultural context and communication style shape the disclosure practices. This is similar to a recent four-country comparison of influencer sponsorship disclosure on Instagram which also found influencer marketing regulations and market maturity the strongest determinants of sponsorship disclosure practices [

46]. In our study, France has strict restrictions of influencers with requirements on explicit disclosure of sponsorships in the content [

47], and hence, French-speaking participants are most likely to disclose their sponsorship in the content explicitly. As the influencer industry is large and well developed there, and China has no such explicit disclosure requirements but only advertising disclaimer in its advertising laws [

7], influencers are least likely to mention the sponsorship explicitly in the content. Instead, they use disclaimer the most to fulfill legal disclosure requirement. However, our qualitative interviews also reveal another reason why the Chinese influencers do not disclose sponsorship in the content directly is the client’s expectations and the perceived awkwardness to talk about being sponsored. Indeed, our study found using disclaimers, not direct disclosure in content, is the most common way of sponsorship disclosure because most markets do not have the legal requirement of strict direct disclosure in the content.

Nonetheless, the primary motivation to create content as financial gain and follower size are found to affect influencers’ sponsorship disclosure practice. Those influencers whose primary motivation to create content not for financial gain are more likely to choose only brands that they use and emphasize the authenticity of their endorsement. For influencers who do not see themselves creating content for financial gain, their perceived authenticity and integrity of endorsing products they use will increase their credibility and trust from the followers. Creators with large follower size are more likely to disclose the sponsorship directly in the content or as disclaimers than those who have a smaller follower size. They see the need to be transparent and disclose that they have been sponsored to win the trust of followers and follow regulations, as prior studies found [

17,

36].

The most surprising result is that journalism background does not affect sponsorship disclosure practices and attitudes toward problematic marketing. Journalism training involves professionalism, proper attribution, and transparency. When it comes to sponsorship disclosure and problematic digital marketing practices, these principles no longer seem to apply, and it is up to individual situation/contingency factors that determine the influencer’s disclosure and attitude toward problematic digital marketing practices. The influencer’s needs to adapt to platform algorithms override the journalistic transparency ethical standards.

Our findings suggest that, within platformized visibility economies, market incentives and platform metrics may override traditional professional norms, rendering journalism training less salient than the immediate pressures of maintaining audience attention and brand relationships. In other words, structural conditions tied to platform governance appear to narrow the space in which formal ethical training can meaningfully shape day-to-day disclosure decisions.

The in-depth interviews helped us to identify more important considerations for the creators to disclose their sponsorship, which is either on a case-by-case basis such as client expectation and the type of brand or can be specific to the values and beliefs of the creators. If they choose only brands that align with their values, then they are proud to disclose such sponsorship/brand collaboration as it can reflect the authenticity of the endorsement and may strengthen trust of the followers. If creators are confident in themselves, they will not worry that their disclosure of sponsorship will make people trust them less and their followers will support the creators and buy the brand they endorsed. Hence, except the disclaimer practice, which is more a legal or platform compliance, all other sponsorship disclosure practice is more the creators’ choice and a balance between client expectation and creators’ judgment.

The most surprising result to us is that motivation for creating content does not affect ethical practice as much as commonly believed [

48,

49]. Whether creating content for financial gain or as a primary source of income is not related to disclosure and attitude toward problematic digital marketing. Financial gain motivation only makes the influencer less selective of the brands they will endorse, but not less likely to disclose sponsorship. The results reflect how sponsorship is disclosed is based on a delicate negotiation between transparency and accountability to the public [

6], the authenticity principle [

13] of being true to themselves and trustworthy to their followers. We found most influencers report disclosing their sponsorship in different forms in this global study and non-disclosure is very rare. Those who do not focus on financial gain only are more likely to recommend products that they personally use or they genuinely believe will be good for the consumers. Hence, sponsorship disclosure practice is a fine balancing act for influencers to provide useful product information to consumers while protecting their personal brand reputation, accommodating clients’ expectation and in compliance with the market regulations.

Furthermore, we found that content creators are, in general, quite ambivalent on the problematic digital marketing practices. While using bots to boost followers and viewers is more likely to be opposed, the feeling is not that strong as it is rated on average 3.2 out of 5. For other problematic digital marketing practices, not only are there no differences among the different types of content creators, they are more on the side of support to neutral (2.4–3.6). Boosting traffic as a common problematic digital marketing practice can be seen as beneficial to the creators in gaining more followers and so they do not care so much about the misleading information and redirection that these practices made. Hence, beyond individual-level ethics, we should understand influencer work is also shaped by platformized creative labor and the attention economy. Our result is also consistent with accounts of platformized creative labor, in which creators perceive visibility and growth as prerequisites for economic survival [

46,

50]. Algorithms that reward visibility, engagement, and growth put continual pressure on creators to optimize reach, which can make traffic-boosting tactics or minimally compliant disclosure appear as pragmatic, survival-oriented choices rather than deliberate ethical violations.

These structural dynamics help explain why some influencers express ambivalence toward practices such as bots or cloaking while simultaneously acknowledging their ethical ambiguity. In addition, the market maturity and regulatory regimes, platform norms may better explain the ethical practice patterns observed than the general communication style context and demographics of the influencers.

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Study

Although this study is one of the few large-scale studies of influencers and probably the only one that covers so many countries and language regions, there are limitations in drawing conclusions. As it is costly and difficult to recruit qualified influencers to respond to the survey, the final sample size of 500 is small in light of the large numbers of influencers worldwide. In addition, our sample is heavily skewed toward nano-influencers, reflecting the current creator economy where smaller accounts outnumber high-reach creators. To enable meaningful statistical comparison, we combined micro-, macro-, and mega-influencers into a single 10 k+ category. While necessary given the distribution, this choice also collapses heterogeneity among larger creators and means that results for this group should be interpreted with caution. Future research using larger samples of high-reach influencers and more detailed descriptors of industry sector, platform type, and regulatory context would allow for more fine-grained comparisons. The various contingency factors used in disclosure practices means that the ethical principles behind them are unclear and in need of formulation. Despite these limitations, the study offers a big global picture of the prevalence of sponsorship among influencers and their ethical practices. It shows more similarities than differences in influencers worldwide. It is recommended that a development of sponsorship disclosure best practices, either by professional associations or platforms’ code of ethics, can provide a framework for influencers to follow rather than by the individual’s judgment. This will also help them manage client’s expectations to maximize success of the endorsement. To facilitate influencers in assessing the impact of their disclosure choice, future studies can use experiments to examine the effect of different disclosure practices on audiences’ perception of authenticity, credibility of the creator, and their likelihood to purchase the endorsed brand.

Despite these limitations, this study shows the complexity of making sponsorship disclosure decisions as ethical practice for influencers worldwide. It is not just culture and influencers’ own attributes, but other contingency factors and regulations that are at play in determining their decisions of how to disclose the sponsorship, not simply whether to disclose or not. It indicates the need for a coherent ethical theory-based framework that incorporates contingency considerations to help influencers find the best way to disclose their brand partnership. The framework should include a consumer welfare analysis of sponsorship disclosure type based on empirical evidence (utilitarianism), alignment of the influencer’s values with the endorsed product/service and the morality and integrity of endorsing something the influencer does not use (virtue ethics), and stakeholder and corporate social responsibility theories for the clients in the disclosure avoidance. The framework should help boost influencers’ authenticity and trustworthiness based on a transparency principle while providing useful product or service recommendations for audiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H.; methodology, L.H.; validation, L.H., and Y.Y.; analysis, H.L.A., K.Z., A.B., and Y.Y.; investigation, M.A., H.L.A., L.H., K.Z., A.B., O.B., M.L., and Y.Y.; resources, L.H. and M.A.; data curation, H.L.A., L.H., K.Z., A.B., and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.A., L.H., K.Z., A.B., and M.L.; writing—review and editing, L.H. and M.A.; supervision, L.H.; funding acquisition, M.A., O.B., and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was commissioned by UNESCO as a contribution to the report, ‘Behind the Screens: insights from digital content creators; understanding their intentions, practices and challenges’. ©UNESCO 2024. The APC was funded by King Abdulaziz University Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bowling Green State University (protocol code 2221820-3, approval date 4 August 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all interview participants prior to data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Due to privacy and confidentiality agreements with participants, the full dataset cannot be publicly released.

Acknowledgments

This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO). The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication, which do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of UNESCO. The authors also acknowledge with thanks the support provided by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University for financial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of countries and number of participants in each country in the study.

Table A1.

List of countries and number of participants in each country in the study.

| List of Countries | N | % |

|---|

| Algeria | 1 | 0.2% |

| Argentina | 12 | 2.4% |

| Australia | 3 | 0.6% |

| Austria | 18 | 3.6% |

| Bangladesh | 4 | 0.8% |

| Belgium | 7 | 1.4% |

| Brazil | 40 | 8.0% |

| Canada | 24 | 4.8% |

| Chile | 8 | 1.6% |

| China | 40 | 8.0% |

| Colombia | 5 | 1.0% |

| Croatia | 7 | 1.4% |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 8 | 1.6% |

| Egypt | 8 | 1.6% |

| France | 23 | 4.6% |

| Georgia | 1 | 0.2% |

| Germany | 18 | 3.6% |

| Haiti | 5 | 1.0% |

| Hong Kong (S.A.R.) | 10 | 2.0% |

| Hungary | 8 | 1.6% |

| India | 29 | 5.8% |

| Ireland | 19 | 3.8% |

| Jordan | 6 | 1.2% |

| Kazakhstan | 13 | 2.6% |

| Kenya | 3 | 0.6% |

| Kuwait | 5 | 1.0% |

| Kyrgyzstan | 1 | 0.2% |

| Lebanon | 5 | 1.0% |

| Malaysia | 2 | 0.4% |

| Mexico | 8 | 1.6% |

| New Zealand | 12 | 2.4% |

| Nigeria | 3 | 0.6% |

| Oman | 5 | 1.0% |

| Portugal | 10 | 2.0% |

| Qatar | 5 | 1.0% |

| Russian Federation | 1 | 0.2% |

| Saudi Arabia | 9 | 1.8% |

| Singapore | 19 | 3.8% |

| South Africa | 9 | 1.8% |

| Spain | 17 | 3.4% |

| Switzerland | 14 | 2.8% |

| Tajikistan | 1 | 0.2% |

| Ukraine | 18 | 3.6% |

| United Arab Emirates | 6 | 1.2% |

| United Kingdom | 17 | 3.4% |

| United States | 13 | 2.6% |

| Total | 500 | 100.0% |

References

- Influencer Marketing Hub. Influencer Marketing Benchmark Report 2025. 25 April 2025. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- World Federation of Advertisers. More Than Half of Multinational Brands Plan to Boost Influencer Market Spend. 2025. Available online: https://wfanet.org/knowledge/item/2025/03/27/more-than-half-of-multinational-brands-plan-to-boost-influencer-market-spend (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Ha, L.; Yang, Y. Research about persuasive effects of social media influencers as online opinion leaders 1990–2020. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2023, 18, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; Charry, K. Do influencers need to tell audiences they’re getting paid? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/08/do-influencers-need-to-tell-audiences-theyre-getting-paid (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Opree, S.J.; Cartwright, R.F. Brand in focus: Activating persuasion knowledge. Communications 2021, 47, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, D.; Pavković, T. The ethics of influencer marketing: An analysis of transparency and accountability in digital advertising. MAP Soc. Sci. 2025, 6, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisken, A. How Social Media Influencer Marketing Regulation Differs Across the Asia Pacific Region. 12 April 2024. Pinsent Masons. Available online: https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/influencer-marketing-regulation-across-asia-pacific-region. (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Boerman, S.C.; Willemsen, L.M.; Van Der Aa, E.P. “This post is sponsored”: Effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word-of-mouth in the context of Facebook. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 38, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C. The effects of the standardized Instagram disclosure for micro- and meso-influencers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 103, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, A.; Vinzenz, F.; Wirth, W. Promoting sustainability on Instagram. Young Consum. 2022, 23, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jans, S.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. How an advertising disclosure alerts young adolescents to sponsored vlogs. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Boerman, S.C.; Tarrahi, F. A meta-analysis of the effects of disclosing sponsored content. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, M.L.; Stoldt, R.; Tully, M.; Ekdale, B. Ethics of authenticity and sponsored content. J. Media Ethics 2020, 35, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, N.S.; Enke, N. “I’ve never seen a client say: ‘Tell the influencer not to label this as sponsored’”: An exploration into influencer industry ethics. Public Relat. Rev. 2022, 48, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saternus, Z.; Mihale-Wilson, C.; Hinz, O. Influencer marketing on Instagram—Disclosure strategies. Electron. Mark. 2024, 34, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozendaal, E.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; van der Goot, M.J. Children’s perceptions of sponsorship disclosures. In Advances in Advertising Research; Waiguny, M.K.J., Rosengren, S., Eds.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; Volume XI, pp. 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leban, M.; Thomsen, T.U.; von Wallpach, S.; Voyer, B.G. Constructing personas of high-net-worth influencers. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.A. Using classic social media cases to distill ethical guidelines for digital engagement. J. Mass Media Ethics 2013, 28, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, V.; Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Singh, J.J. Ethical image and brand equity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.U.; Rehman, U.; Parmar, B.; Ismail, I. Effects of moral violation on algorithmic transparency. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 193, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E. Beyond Culture; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst, W.B.; Ting-Toomey, S. Culture and Interpersonal Communication; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pickel, A. Nations, national cultures, and natural languages: A contribution to the sociology of nations. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2013, 43, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M. Global North and Global South: Definitions and differences. In Encyclopædia Britannica 2025; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Global-North-and-Global-South (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Ortova, N.; Hejlova, D.; Weiss, D. Creating a code of ethics for influencer marketing. J. Media Ethics 2023, 38, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, G.J. A global comparative analysis of the global survey of business ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudders, L.; De Jans, S. Gender effects in influencer marketing. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 41, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehri, M. Choosing the best social media influencer: The role of gender, age, and product type in influencer Marketing. Int. J. Mark. Strateg. 2021, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Farrell, J.R. More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect trust. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Fernández Giordano, M.; Lopez-Lopez, D. Behind influencer marketing: Key marketing decisions and their effects on followers’ responses. J. Mark Manag. 2020, 36, 579–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Lu, J.G.; Galinsky, A.D. Moral utility theory: Understanding motivations to behave unethically. Res. Organ. Behav. 2018, 38, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steils, N.; Martin, A.; Toti, J.F. Managing the transparency paradox in influencer disclosures. J. Advert. Res. 2022, 62, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.J.; Phua, J.; Lim, J.; Jun, H. Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2017, 17, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, F. Influencer marketing: Motivations of young adults. J. Digit. Soc. Media Mark. 2020, 8, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Ha, L. Why people use TikTok and how purchase intentions are affected. J. Interact. Advert. 2021, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Evans, N.J. The role of a companion banner and sponsorship transparency in recognizing and evaluating article-style native advertising. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 43, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; de Kerviler, G.; Guidry Moulard, J. Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Zhang, S.I. Contested journalistic professionalism in China. J. Stud. 2022, 23, 1962–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.; Moreno, A.; Molleda, J.C.; Khalil, N.; Verhoeven, P. New gatekeepers in PR. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, A. What Is Clocking in Digital Marketing? Salfalta. Available online: https://www.safalta.com/online-digital-marketing/search-engine-optimisation-seo/what-is-clocking-in-digital-marketing-with-its-types-and-examples (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- OWSD. Countries in the Global South by Region and Alphabetical Order; Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World. Available online: https://owsd.net/sites/default/files/OWSD%20138%20Countries%20-%20Global%20South.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Santora, J. 20 Types of Social Media Influencers You Need to Know. Influencer Mark. Hub 2024. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/types-of-influencers/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Bertaglia, T.; Goanta, C.; Spanakis, G.; Iamnitchi, A. Influencer self-disclosure practices on Instagram: A multi-country longitudinal study. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2025, 45, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascolese, B. France’s new influencer laws adopted June 1, 2023. Natl. Law Rev. 2023, 173, 355. Available online: https://natlawreview.com/article/france-s-new-influencer-law-adopted-june-1-2023 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Abidin, C.; Hansen, K.; Hogsnes, M.; Newlands, G.; Nielsen, M.L.; Yung Nielsen, L.; Sihvonen, T. A review of formal and informal regulations in the Nordic influencer industry. Sciendo Nord. J. Media Stud. 2020, 2, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A. When likes go rogue: Advertising standards and the malpractice of unruly social media influencers. J. Media Law 2024, 16, 74–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Aren’t these just young, rich women doing vain things online? Influencer selfies as subversive frivolity. Soc. Media Soc. 2016, 2, 2056305116641342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |