1. Introduction

In the era of digital economy, computing power has emerged alongside data and algorithms as a fundamental factor driving economic growth and qualitative productivity improvements [

1]. The deep integration of digital and real economies serves as the core engine for high-quality economic development [

2]. Computing power, acting as the “engine” of the digital age, has become a strategic resource underpinning the new wave of scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation. To solidify this digital foundation, China has initiated the monumental “East Data, West Computing” project, aiming to build an integrated national computing network. This initiative is not only a crucial step in driving digital transformation and building an innovation-oriented nation but also pivotal for China to secure a proactive position in the future global competitive landscape. Strengthening the computing power base is essential to provide sustained momentum for the digital-real economy integration, ultimately empowering the real economy to achieve qualitative enhancement and reasonable quantitative growth.

However, while macro-level policies and infrastructure advancements are vigorously promoted, a critical micro-level mechanism remains inadequately addressed: our systematic understanding of how firms can acquire and effectively utilize computing power as a strategic resource to achieve qualitative changes in productivity at the micro level is still lacking. Existing literature often treats computing power as a homogeneous public infrastructure [

3], overlooking its nature as a heterogeneous digital strategic resource for firms and the complex intermediate mechanisms through which it is translated into competitive advantage [

4].

The core of this transformation process lies in how computing power resources empower a firm’s dynamic capabilities—the higher-order organizational abilities to sense market changes, seize innovation opportunities, and reconfigure resource bases [

5,

6]. Particularly in e-commerce and digital business environments characterized by rapidly evolving competitive landscapes, dynamic capabilities are fundamental for firms to maintain agility and innovativeness [

7]. Consequently, a key research question emerges: Does and how does the acquisition of computing power resources (e.g., obtaining an Internet Data Center (IDC) license) drive the leap in new quality productivity by reshaping a firm’s dynamic capabilities? Unraveling this “black box” holds significant theoretical value and provides critical guidance for firms making digital investment decisions.

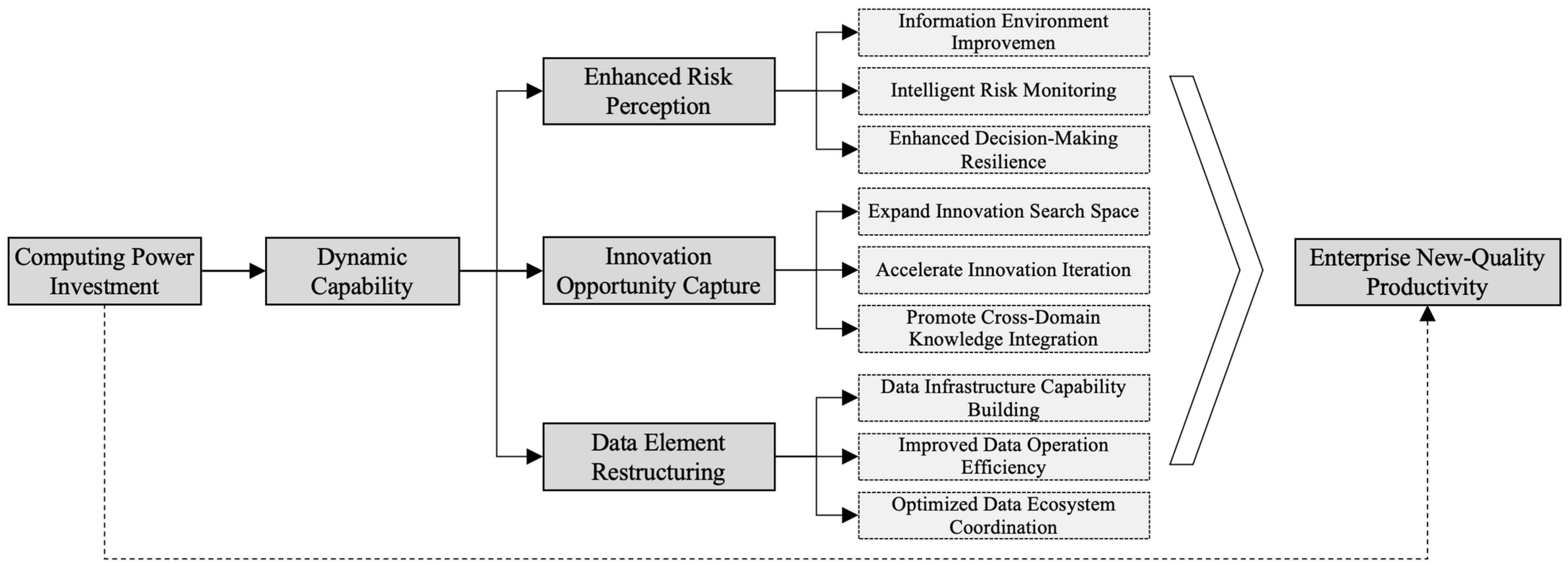

Based on this, our study utilizes a sample of China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share listed manufacturing firms from 2011 to 2022. For the first time, we employ hand-collected firm-level IDC license data, treating a firm’s acquisition of an IDC license as a critical injection of “digital strategic resource,” to empirically examine its impact on new quality productivity. Our findings indicate that computing power investment significantly enhances firm-level new quality productivity. Mechanism analysis reveals that this process operates primarily through three pathways: First, enhanced risk perception, whereby computing power improves the firm’s adaptability to uncertain environments by improving the information environment, enabling intelligent risk monitoring, and enhancing decision-making resilience. Second, innovation opportunity seizure, whereby computing power reshapes the firm’s R&D paradigm by expanding innovation search space, accelerating innovation iteration, and facilitating cross-domain knowledge integration. Third, data factor reconfiguration, whereby computing power activates data as a core production factor by building data foundation capabilities, improving data operational efficiency, and optimizing data ecosystem synergy.

Further research reveals the boundary conditions of the computing power empowerment effect. Top management’s digital perception capability and intense market competition significantly strengthen the effect of computing power investment. Simultaneously, this effect is more pronounced in high-tech industries, firms with high organizational absorption capacity, and regions with superior eastern digital endowment, reflecting the “technology-organization-environment” fit. An expansive analysis also discovers that while computing power enhances labor productivity, it may also trigger strategic information hiding behavior by firms seeking to protect core algorithmic competitive advantages. This provides a fresh perspective for understanding the complex consequences of digital transformation.

The marginal contributions of this study are threefold: First, it micro-levels the concept of computing power from macro-infrastructure to a contestable strategic digital resource for firms, enriching the digital resource-based view. Second, it systematically unveils the intermediate mechanism through which computing power drives new quality productivity from the three dimensions of dynamic capability theory—sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring—thereby opening the “black box” of the “resource-capability-performance” relationship. Third, it identifies the unintended impact of computing power investment on the capital market information environment while empowering the real economy, providing important insights for a comprehensive assessment of the economic consequences of digitalization. The conclusions of this research hold significant reference value for firms and policymakers striving to achieve high-quality development through “digital empowerment.”

2. Materials

2.1. The Evolution of Computing Power Investment

China’s computing power infrastructure is undergoing rapid expansion and institutional restructuring. As of June 2025, the number of standard racks in operational data centers nationwide exceeded 10.85 million, placing China second globally in overall computing power. Within this, intelligent computing power reached 788 EFLOPS (FP16), supported by more than 35,000 high-quality datasets.

At present, China’s computing power market exhibits a coexistence of “surplus” and “shortage.” On the one hand, the intensive commissioning of large-scale infrastructure has significantly intensified competition, driving a continuous decline in computing power prices. Since the first half of 2025, the monthly rental cost of high-end GPUs (such as the H100) has fallen below ¥50,000, and computing power has become increasingly homogeneous and widely accessible. On the other hand, the rapid iteration of artificial intelligence applications has sharply increased demand for high-quality computing resources. For example, training GPT-4, with 1.8 trillion parameters, requires approximately 68 times the computing power of its predecessor and about 25,000 NVIDIA A100 GPUs running continuously for 90–100 days. As a result, high-performance, scalable, and reliable intelligent computing power has emerged as a new strategic scarce resource.

Against this backdrop, the institutional role of the Internet Data Center (IDC) license has shifted from a mere permit for data center construction and operation to a critical access threshold for enterprises to legally obtain and operate large-scale intelligent computing resources. Acquiring an IDC license no longer simply denotes regulatory compliance; it signifies a firm’s capability to embed itself in the core network of national digital infrastructure and to secure key digital production factors. Accordingly, treating the acquisition of an IDC license as a discrete moment of digital strategic resource injection provides an almost ideal quasi-experimental setting for identifying how computing power investment reshapes corporate capabilities and fosters new, quality productive forces.

2.2. Direct Impact of Computing Power Investment on New Quality Productivity

Building on the view of computing power as a strategic digital resource, new quality productivity (NQP) can be understood as productivity gains that arise not from simply increasing input quantities, but from the qualitative upgrading of production factors and the reorganization of production processes enabled by digital technologies [

4]. As an advanced productive force driven by technological innovation, NQP thus reflects deeper restructuring and efficiency release at both the factor and organizational levels.

From the perspective of the resource-based view, firms gain a competitive advantage by acquiring scarce and strategic resources [

8]. Recent research in digital economics extends this argument by showing that digital technologies—especially data, algorithms, and computing power—do not merely enter existing production functions as additional inputs, but reshape the structure and complementarities of the production function itself [

9]. In this sense, computing power emerges as a new type of intangible production factor: it raises the marginal productivity of traditional inputs such as labor and capital, and facilitates the upgrading of the production function toward a more computation-intensive form [

10].

This transformation is consistent with the general-purpose technology (GPT) nature of computing power. Analogous to the historical diffusion of electricity or information technology, computing power is characterized by wide applicability, continuous performance improvement, and strong complementarities with other technologies and organizational practices [

11]. By enabling large-scale data processing, complex algorithmic optimization, and rapid simulation-based experimentation, computing power expands firms’ feasible production sets and unlocks new combinations of labor, capital, and data. Investments in intelligent computing centers, therefore, do not simply scale up computational capacity; they shift firms toward a computation-augmented production function, laying the micro-foundation for quality-oriented productivity gains.

Within this theoretical logic, computing power is precisely the type of strategic digital resource that activates NQP. It improves information-processing efficiency [

12], accelerates knowledge creation and recombination, supports data-driven intra- and inter-firm coordination, and enables firms to internalize the benefits of embedding digital factors into core business processes. In other words, computing power transforms how firms sense, process, and act upon information, rather than merely “speeding up” existing routines.

Moreover, the productivity-enhancing effects of computing power depend critically on firms’ capability to convert technological potential into actual performance [

13]. This aligns with the dynamic capability framework, which emphasizes sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring as key higher-order processes that allow organizations to respond to and shape technological change. Computing power strengthens these dynamic capabilities by: enhancing sensing through real-time integration of heterogeneous information sources; enabling more efficient opportunity seizing through faster innovation iteration and experimentation; and supporting reconfiguration through data-driven value-chain optimization and organizational redesign.

Taken together, computing power investment simultaneously triggers production function upgrading at the factor level and capability upgrading at the organizational level, making it a structural driver of NQP rather than a simple cost input.

H1. Computing power investment enhances the enterprise’s new quality productivity.

2.3. The Mechanism Through Which Computing Power Investment Affects Enterprise New Quality Productivity

The underlying mechanism through which computing power investment enhances enterprise new quality productivity can be systematically interpreted through the lens of dynamic capability theory. Dynamic capabilities refer to a firm’s ability to sense opportunities and threats, seize opportunities, and reconfigure resources and competencies. This theory posits that firms integrate, build, and reorganize internal and external resources through three core processes—sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring—to adapt to rapidly changing environments [

5]. In the context of the digital economy, computing power investment reshapes firms’ information-processing architectures and decision-making processes, thereby upgrading these three dimensions of dynamic capabilities. Accordingly, the mechanism can be analytically decomposed into the following three aspects (

Figure 1).

2.3.1. Sensing Mechanism: From Information Processing to Opportunity and Risk Insight

In dynamic competitive environments where uncertainty and complexity have become the norm, enterprises face compounded and concealed risks. Traditional risk management models relying on historical experience and reactive responses struggle to address new risks arising from rapidly changing market conditions and technological iterations. According to dynamic capability theory, sensing capability forms the foundation for identifying opportunities and threats, with computing power serving as a crucial enabler for enhancing this capability.

Computing power investment transforms risk perception from passive response into proactive identification and mitigation of potential threats by empowering information processing and intelligent analysis. First, it significantly improves the corporate information environment. Robust computing support enables firms to establish comprehensive data collection, processing, and disclosure systems, integrating internal and external information in (near) real time and breaking down information silos. This enhances operational transparency and performance predictability, laying the informational foundation for risk identification [

14]. Second, computing power enables intelligent risk monitoring. Through big data analytics and machine learning technologies, enterprises can construct dynamic risk monitoring systems that utilize pattern recognition and anomaly detection to achieve real-time surveillance and early warning of multidimensional risks—including market, technological, and compliance risks—thus shifting risk management from post hoc remediation to ex ante prevention. Finally, computing power empowers scenario analysis, stress testing, and simulation modeling, allowing enterprises to simulate extreme conditions in virtual environments and evaluate risk-return tradeoffs across different strategic options. This supports more robust and flexible strategic choices and enhances organizational adaptability and resilience in uncertain environments [

15]. Thus, by improving the information environment, strengthening intelligent risk monitoring, and supporting resilient decision-making, computing power investment not only enhances firms’ ability to accurately sense and assess risks but also enables them to maintain strategic focus while flexibly adapting to uncertainty, thereby safeguarding the stable development of new quality productivity.

H2. Computing power investment enhances enterprise risk perception capability through improved information environments, intelligent risk monitoring, and enhanced decision-making resilience, thereby driving the improvement of new quality productivity.

2.3.2. Seizing Mechanism: Reshaping Innovation Paradigms

Innovation serves as the core driver of new quality productivity, with computing power fundamentally reshaping corporate R&D paradigms and innovation models. From a dynamic capability’s perspective, innovation opportunity seizing refers to an organization’s critical capacity to transform identified opportunities into tangible innovation outcomes [

16]. However, traditional innovation models face significant constraints, including limited search scope, prohibitive trial-and-error costs, and knowledge integration barriers, which collectively inhibit substantial improvement in innovation capabilities. Computing power investment provides key technological support for overcoming these constraints and upgrading innovation opportunity-seizing capabilities.

The enabling effect of computing power on innovation opportunity seizing operates through three distinct dimensions. First, in the innovation search dimension, substantial computing capacity allows firms to process and analyze massive volumes of technological information and market data. Through machine learning and pattern recognition technologies, organizations can identify latent innovation opportunities, thereby expanding innovation search from localized exploration to global optimization. For example, firms can conduct comprehensive optimization based on large-scale datasets such as patent databases, scientific publications, and user behavior data, significantly broadening the scope and depth of innovation search.

Second, in the innovation experimentation dimension, computing power enables technologies such as digital twins and simulation modeling, allowing firms to conduct large-scale innovation trials in virtual environments. These technologies substantially reduce experimentation costs while accelerating innovation iteration cycles [

17]. This computational advantage not only enables firms to address previously intractable complex system problems, thereby advancing the technological frontier of innovation, but more importantly, enhances the output efficiency per unit of R&D investment through accelerated iteration processes.

Third, in the knowledge integration dimension, computing power relaxes traditional computational bottlenecks in knowledge processing. Organizations can leverage artificial intelligence technologies to construct knowledge graphs and achieve deep integration of cross-disciplinary knowledge, consequently generating combinatorial innovations and disruptive breakthroughs [

18]. Existing evidence suggests that computing power investment thus transforms innovation from experience-dependent models to new paradigms centered on data-driven analysis and intelligent computing [

19]. This multi-level capability enhancement signifies a fundamental transition in corporate innovation paradigms—from traditional experience-based approaches to innovation driven by data analytics and computational intelligence—thereby establishing a solid foundation for developing new quality productivity.

H3. Computing power investment enhances firms’ innovation opportunity seizing capability by expanding innovation search scope, accelerating innovation iteration, and promoting cross-domain knowledge integration, thereby driving substantial improvement in new quality productivity.

2.3.3. Reconfiguration Mechanism: Unleashing Data Factor Value and Reshaping the Value Chain

In the digital economy era, data has become a key production factor, whose massive value realization requires substantial technical support. The core value of computing power investment lies in its ability to transform data from a cost burden into a value source. When enterprises possess sufficient computing resources, previously isolated data silos across business segments can be interconnected, fragmented information can be integrated, and static historical records can be dynamically analyzed, thereby achieving systematic reconfiguration of data factors.

Computing power investment enables intelligent reconfiguration of the enterprise value chain by activating data factors. First, computing power investment facilitates the construction of fundamental data capabilities. By deploying key technologies such as big data analytics and cloud computing, enterprises can elevate their data factor utilization levels, transforming dormant data resources into new production factors. This supports digital transformation and helps convert massive unstructured data into analyzable and utilizable digital assets, laying a solid foundation for data value realization [

20].

Second, computing power investment enhances data-driven operational efficiency. Through in-depth mining of data assets, computing power supports enterprises in achieving the intelligent transformation of entire processes. From simulation in R&D design and flexible scheduling in production manufacturing to precise positioning in marketing, data insights permeate all value chain segments. This drives the transition from experience-based decision-making to data-driven decision-making, significantly reducing operational costs and improving resource utilization efficiency [

21,

22].

Furthermore, computing power investment optimizes data ecosystem collaboration. Enhanced information processing and transmission capabilities through computing power improve information transparency via data sharing. This reduces information asymmetry between enterprises and their upstream and downstream partners, investors, and other stakeholders, optimizing resource allocation efficiency both within and outside the enterprise and lowering transaction costs and financing constraints [

22,

23].

Through these three dimensions of data factor reconfiguration, enterprises not only achieve internal operational efficiency improvements but, more importantly, gain new data-based competitive advantages and develop novel production modes adapted to the digital economy era [

24]. Because the ultimate manifestation of dynamic capabilities is the reconfiguration of the resource base, computing power enables enterprises to reintegrate resources around data and to form entirely new competitive advantages in production modes.

H4. Computing power investment achieves data factor reconfiguration through building data foundation capabilities, enhancing data operation efficiency, and optimizing data ecosystem collaboration, thereby driving the improvement of enterprise new quality productivity.

7. Conclusions and Implications

7.1. Main Research Findings

Based on data from China’s A-share manufacturing listed companies from 2011 to 2022, this study treats the establishment of intelligent computing centers (proxied by firms’ acquisition of IDC licenses) as a quasi-natural experiment. Employing a staggered difference-in-differences model combined with causal inference strategies including propensity score matching, DID, instrumental variable approach, and double machine learning, we empirically examine the impact of computing power investment on corporate new quality productivity.

The findings reveal that: (1) computing power investment significantly enhances new quality productivity, with this conclusion remaining robust across various tests. (2) Mechanism analysis shows that this effect operates through three dynamic capability pathways: enhancing risk perception capability by improving information environments, enabling intelligent risk monitoring, and strengthening decision-making resilience; strengthening innovation opportunity seizure capability by expanding innovation search space, accelerating innovation iteration, and facilitating cross-domain knowledge integration; achieving data element reconstruction by building data infrastructure capabilities, improving data operational efficiency, and optimizing data ecosystem collaboration. (3) Heterogeneity analysis indicates that the promoting effect is more pronounced in firms with strong executive digital cognition, intense market competition, non-heavy pollution industries, high-tech sectors, high absorptive capacity, eastern regions, and superior digital endowments. (4) Extended analysis reveals that computing power investment drives optimal human capital allocation while potentially inducing strategic information concealment behaviors as firms seek to protect competitive advantages.

7.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

For enterprises, computing power investment should be regarded as a strategic initiative to build long-term digital competitive advantage, rather than merely a technical upgrade. Corporate management needs to integrate computing power resources into the strategic planning system, and while acquiring key resources such as IDC licenses, focus on cultivating matching data governance capabilities and organizational change capabilities to achieve synergistic development of computing power resources and dynamic capabilities. Regarding information disclosure, firms should establish differentiated disclosure strategies on a compliant basis, balancing transparent operation with the protection of core digital assets.

For enterprise-level decision-makers, our findings offer several actionable insights. First, computing power investment should be regarded as a core strategic initiative to build long-term digital competitive advantage, not merely a technical IT upgrade. Management must integrate computing power into the firm’s strategic planning system. Specifically, managers must strategically allocate resources, balancing the security and control of private IDC investments against the flexibility and scalability of public cloud services. Second, acquiring hardware is insufficient. Firms must simultaneously invest in workforce digital training and cultivate organizational absorptive capacity. This ensures that employees have the skills to leverage new computing resources for sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring data. Third, while acquiring key resources such as IDC licenses, firms must focus on cultivating matching data governance capabilities and organizational agility to achieve synergistic development. Finally, regarding information disclosure, firms should establish differentiated strategies on a compliant basis, balancing transparent operation with the protection of core digital assets and algorithms, as our extended analysis (

Section 6.2) suggests.

For policymakers, it is essential to further improve the market-oriented allocation mechanism of computing power infrastructure. Measures such as establishing regional computing power trading platforms and reducing computing power usage costs for SMEs can enhance the inclusiveness of national strategies like “East Data, West Computing.” Second, differentiated industrial support policies are needed: high-tech industries should be encouraged to explore cutting-edge computing power applications, while traditional industries should be supported in completing digital transformation to improve their absorption capacity for computing resources. Additionally, regulatory authorities should closely monitor the impact of computing power proliferation on market competition dynamics and promptly improve disclosure standards related to digital assets and algorithmic models, seeking a balance between promoting innovation and maintaining market fairness. Finally, it is recommended that government departments incorporate computing power efficiency indicators into regional digital economy evaluation systems, guide different countries to formulate computing power development strategies aligned with local industrial characteristics and resource endowments, avoid redundant construction and resource mismatch, and promote the formation of a new development pattern for a nationally integrated computing power network. These implications are particularly salient for digital business practitioners, online platforms, and other technology-driven firms, for whom computing power functions as critical infrastructure for real-time analytics, personalized service, and scalable experimentation in electronic commerce.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study, despite its robust findings, has limitations that open avenues for future research. First, our 2011–2022 study period captures short- to medium-term effects; the long-term trajectory of this impact remains an open question for future work to explore, specifically whether productivity gains accelerate (due to AI’s scaling returns), plateau, or diminish. Second, the generalizability of our findings, derived from China’s unique national strategy context, warrants further investigation. While the core mechanism is likely universal, its manifestation in other market economies may differ based on boundary conditions like stricter data regulations (e.g., GDPR) or the dominance of public cloud providers as substitutes. Finally, our proxy (IDC license) measures access to strategic resources, not the intensity or quality (e.g., AI-specific computing) of their use. Future research using more granular data on IT expenditures or AI-specific computing could disentangle these important nuances.