1. Introduction

The digital transformation of trade and work has been changing the look of supply chains, with deep effects on strength and green practices. Moreover, disease outbreaks and world political events have shown the need for supply systems that can take in and deal with changes, while new digital tools have been sold as ways of observing situations, working together, and improving. However, the green results of this change are still argued over and depend on where it happens; careful, comparative evidence across economies and time periods is needed [

1,

2,

3].

On the one hand, sustainable supply chain scholarship has long emphasized the integration of environmental and social objectives with operational performance, but empirical generalizations are difficult because technology alters both process design and demand patterns. Likewise, canonical frameworks position sustainability as a strategic supply chain concern, yet the pathways through which digitalization affects emissions intensity remain under-specified at system level. In particular, digital commerce may both substitute and stimulate physical activity across the “last mile,” inventory placement, and returns [

4,

5].

Nonetheless, evidence regarding e-commerce and environmental outcomes is mixed. Studies of online grocery and non-food retailing indicate that home delivery can reduce carbon footprints if drops are dense and fully replace trips made by private cars, but this advantage can be offset by failed deliveries, high return rates, or long delivery radii. Comparative life-cycle assessments increasingly indicate configuration as the defining factor, rather than the channel itself [

6,

7,

8].

Furthermore, digitalization is not just about front-end transactions. Hence, back-end digitalization through data-driven planning, IoT sensing, and AI forecasting reduces the need for safety stocks to smooth flows and compress lead times. Similarly, it potentially reduces energy per unit of output, as discussed in operations and logistics reviews, because analytics changes the economics of consolidation and routing, while provenance has been explored in the blockchain for waste reduction in the green supply chain [

2,

9,

10,

11].

Nevertheless, rebound mechanisms do remain: efficiency gains may lower effective prices, increase demand, and therefore offset environmental savings. These “backfire” channels are well-documented within the energy economics literature, suggesting that in some contexts increased digital uptake can actually increase both activity and transport volumes even though process energy per task has decreased [

12,

13,

14].

Moreover, macro-level studies relating digitalization to emissions outcomes have resulted in suggestive but heterogeneous results across countries and periods. In panel analyses, it has been found that digital development and the diffusion of ICT correlate with lower carbon intensity via structural change and efficiency intensity, mostly where complementary capabilities and institutions exist; in some stages of development, however, results are found to be weak or inverted [

15,

16,

17]. For supply chains, this heterogeneity plausibly reflects the interaction between digital maturity and the configuration of commercial “touchpoints.” Where e-commerce ecosystems, fulfillment density, and reverse-logistics design are advanced, digitalization may lower emissions intensity; where returns are frequent, delivery density is low, or packaging is excessive, intensity can rise. Recent assessments of B2C logistics and e-grocery echo this conditionality [

7,

18].

A second strand associates clean-energy transitions with firm- and sector-level carbon intensity. Higher shares of renewables and take-up of related technologies are on average associated with lower emissions, setting the scene against which digital effects unfold. This hints at a possible complementarity between digital capacity and the energy mix in determining the path of intensities [

19,

20].

From a methodological point of view, a panel is constructed for European economies and shows how digitalization relates to the greenhouse-gas emissions intensity of economic activity, with a particular focus on the e-commerce complementarity channel. The intensity is operationalized by taking the logarithm of emissions per unit of output, while digitalization is measured through principal-component indexing electronic information flows and online participation infrastructure and use. This indicator, measuring downstream commercial digital maturity in e-commerce for European countries, reflects potential last-mile reconfiguration effects that have been indicated previously in the literature.

We run two-way fixed effects with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are robust to heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence in macro-panels. Series are screened under Im–Pesaran–Shin and Hadri panel unit-root tests, and cross-sectional dependence diagnostics have been checked. In the presence of dynamic persistence and potential endogeneity problems, Arellano–Bond difference GMM is estimated as a robustness check with the most conservative instrument sets.

We consider ourselves motivated by two reasons. First, while the previous literature has treated digitalization and channel configuration separately, we explicitly model their interaction to see whether the effect of digitalization on emission intensity varies with the maturity of e-commerce. Second, we benchmark the main results to alternative dependent variables, emissions per capita and energy intensity, and to pandemic-era heterogeneity with regard to structural shocks that were imparted on shopping patterns and logistics.

One key finding claims that higher digitalization is associated with higher emissions intensity where e-commerce development is strong, most likely due to process improvements that outweigh last-mile and return externalities in those contexts. Where e-commerce is weak, the association is modest; overall, environmental gains from digital channels depend on delivery density and reverse-logistics design and can weaken as digitalization deepens. This pattern holds steady across alternative outcomes and dynamic panel identification.

Moreover, this assertion fuses two debates on how firm and network digital capability aggregate to emissions on the macro level by illustrating when clicks complement or substitute bricks from an ecological perspective, hence reconciling evidence dealing with e-commerce through design-contingent effects and updating empirics in this space. It does so based on a multi-country panel combining TWFE with Driscoll–Kraay inference plus GMM robustness.

For policy and managerial practice, this implies that digital investment alone does not yield net positive gains; the availability of cleaner energy mixes, downstream commerce systems enabling dense, reliable delivery, and reverse-logistics working effectively allow net gains to be achieved. This resonates with work indicating that technology strategies interact with the energy structure plus network design to determine the environment outcome.

This study covers an open question: does digitalization at the national level relate to greenhouse gas emissions intensity once channel configuration and the energy mix are factored in? Evidence from twenty-seven European economies from 2014 to 2022 is assembled, measuring digitalization through a principal component index with e-commerce treated as a separate channel feature. The outcome is specified as emissions per unit of output, identification is implemented with two-way fixed effects and Driscoll–Kraay errors, and difference GMM serves as a probe for dynamic bias and endogeneity. There is no finding of an unconditional reduction in intensity associated with digitalization; rather, the association becomes more positive where e-commerce is deeper. A higher renewable energy share comes out as lower intensity and attenuates the digitalization effect. This paper adds numbers to these conditional associations in a multi country setting and translates them into firm-level implications for consolidation, return management, packaging, measurement, and energy sourcing.

2. Literature Review

Digitalization has been redefining the planning and execution of supply chains, with net effects for greenhouse gas emissions intensity dependent on channel design, together with the energy mix. Simultaneously, e-commerce reconfigures last-mile geometry as well as return flows plus packaging, opening up pathways through which digital capability can increase or decrease emissions per unit output. Outcomes are further conditioned by differences in electricity generation as well as the feasibility of fleet electrification across countries. The issue is thus framed around whether the interaction between digitalization’s effects in terms of e-commerce depth, together with the share of renewable energy, happens to be associated with lower emissions intensity.

2.1. Foundations of Sustainable Supply Chain Management and the Digital Capability Lens

Digital technologies are increasingly being embedded across supply networks and reframing how firms coordinate their information, material, and financial flows. Foundational sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) frameworks argue that environmental performance must be co-optimized with cost, service, and resilience rather than being an afterthought [

1]. This literature places emphasis on the salience cross-tier visibility and collaboration for waste and emission reduction while maintaining competitiveness. In addition, it puts emphasis on a shift in focus from firm-level initiatives to system-level outcomes such as the intensity of greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions relative to economic activity. From this vantage point, digitalization is no longer peripheral but rather a structural capability with environmental consequences that are positive as well as negative.

A major strand puts forth data analytics, sensors, and platforms as levers for better planning and execution. Reviews in logistics and operations show how predictive analytics and big data change inventory policies, routing, and capacity deployment in ways that can not only compress lead times but improve asset utilization [

2,

9]. In principle, tightening process control reduces uncertainty, fully allowing emissions to be embedded in adjustments to transport, warehousing and production. However, scholars note the organizational and behavioral frictions—emissions skills, governance, and incentive alignments—that come to bear on the actual environmental benefits. Digitalization thus makes a net difference rather than having an effect.

E-commerce adds a new, unique channel in the way digitalization impacts the environment. Early empirical results indicated that consolidated home deliveries could well surpass the scattered private shopping trips made by individuals to retail stores in terms of transport emissions, delivery density and failure rates notwithstanding [

1,

6]. Later studies extended the perspective further to include fast-moving consumer goods as well as non-food retail and brought to light basket composition, return rates, and network configuration as specific determinants [

7]. Thus, e-commerce may lower or raise the intensity of emissions, depending on how last-mile logistics and reverse flows are organized.

Recent comparative assessments underscore this conditionality. Using product-level and channel-level footprints, researchers note that delivery success rates, time-window guarantees, and the prevalence of free returns shift the balance between efficiency gains and rebound effects [

8]. Behavioral transport literature further underscores the fact that online shopping has not perfectly substituted store visits; trip chaining as well as browsing still generate travel externalities [

21]. Such insights caution against interpreting “digital commerce” as a homogeneous phenomenon but rather inspire analyses that differentiate general digital capability from specific e-commerce penetration as potentially interacting determinants of environmental performance.

B2C logistics reviews offer design levers that influence environmental outcomes. For example, parcel lockers and pick up points increase drop density, dynamic routing plus demand shape peak smoothing, and micro-fulfillment may reduce stem distance [

22,

23]. The intervention of each of these levers changes the geometry or propensity for failed deliveries and returns on the last mile. Greener results are an outcome of matched digital demand aggregation with high delivery density, reliable consumer presence, and effective reverse logistics. In their absence; however, digital maximum convenience to can increase rather than decrease environmental burdens.

Beyond retail logistics, digitalization starts from upstream all the way through sensing, tracking, and provenance. Work on blockchain and traceability assert that reduced information asymmetries can reduce waste and enable greener sourcing—thus causing higher energy footprints of certain consensus mechanisms, as well as integration challenges, and in turn tempering expectations [

10]. Empirical adoption studies indicate that benefits depend on ecosystem readiness and governance across multi-actor networks. This is precisely the reason why cross-country evidence, where institutional and infrastructural conditions vary, is informative in learning about average environmental associations with digital uptake.

2.2. Macro Evidence, Trade Exposure, and Accounting Perspectives on Emissions Intensity

Macro-level research on the “digital economy” and emissions offers rather suggestive, heterogeneous findings. While panel studies most often find that internet use or digital development at higher levels correlates with lower carbon intensity via efficiency and structural change, effect sizes and even signs vary by income level, industrial mix, and policy regime [

15,

17]. Complementary time-series evidence indicates that digital activity can initially raise electricity demand before decarbonized power and efficiency improvements moderate the footprint [

24]. The literature thus anticipates context-dependent links between digitalization and emissions intensity.

A view is also offered by the trade-environment scholarship. Classic scale, composition, and technique effects analysis presents the fact that openness can work towards increasing or reducing emissions based on how production and technology are rearranged through trade [

25,

26]. For highly interlinked supply networks this may condition the environmental effect of digitalization via merchandise trade intensity through changes in both specialization patterns and volumes of transport. This insight motivates designs which account for trade exposure when relating digital indicators to emissions intensity, so that technology effects are not conflated with shifting production geography.

Further, consumption-based carbon accounting complicates attribution by assigning it to final demand rather than the place of production. Studies show that with increasing globalization, cross-boundary transfers of embodied emissions have increased when measured against the observed territorial intensities [

27,

28]. Though most policy dashboards continue to watch over the territorial metrics, this literature urges analysts to adjust their interpretation of intensity movements for trade and structural factors. It also implies that digitalization’s measured association with territorial intensity might actually mask redistributive effects across borders.

2.3. Operational Mechanisms, Energy Context, and Governance: Toward an Integrative Synthesis

In practice, scholars have cataloged how analytics-enabled planning reduces safety stocks, expedites, and bullwhips—all potential emissions co-benefits—through smoother flows and fewer emergency shipments [

2,

9]. Reviews of the Internet-of-Things emphasize sensing and real-time control for energy management and asset health as incremental efficiency gains that when aggregated at a network scale can be substantial [

29]. But it is to these very contributions that the emphasis should be placed on capability thresholds—data quality, interoperability, and analytics talent—below which digital investments might not translate into measurable environmental improvement.

Additionally, returns play a very sensitive role in the e-commerce–environment nexus. Some empirical pieces of evidence note high return rates for apparel and some durable categories, presenting significant transport and repackaging impacts [

7,

8]. Design responses comprise virtual try-on, size guidance, restocking fees, and consolidated return channels that may materially change the emissions calculus. The literature pragmatically converges on this very fact: digital channels’ environmental gains are hinged less on “online versus offline” than on how that channel is engineered and governed.

A related debate concerns the rebound, mainly because better logistics and process efficiency can cut per-unit emissions but drive more orders, shorter delivery windows, and more convenience-driven consumption [

30]. This matches evidence from energy-economics studies that efficiency can in some cases increase demand under certain elasticities. For digital commerce, the salience of convenience means that demand responses may not be trivial, particularly when delivery is subsidized and returns are free. As a result, most authors who support digital operational excellence also support the parallel pursuit of such demand-side and policy measures that would serve to moderate the rebound.

Energy-system context features increasingly in supply chain sustainability discourse. As electricity generation decarbonizes, the emissions consequences of data centers, electrified fleets, and automated fulfillment shift [

15,

24]. In cleaner grids, the same quantum of digital activity is associated with a smaller footprint; conversely, in carbon-intensive mixes, digital processes may embody higher emissions despite efficiency gains. This suggests a complementarity between digitalization and renewables penetration that shapes the net effect on supply chain emissions intensity.

Empirical reviews of last-mile models show threshold effects. Locker networks and pick-up points need a critical mass before they start yielding any environmental gains, otherwise, in sparse deployments they may actually add detours and idle time to the system [

23,

24]. Micro-fulfillment and urban consolidation centers have indicated promise where there is both demand density and incentives aligned through road pricing. These threshold dynamics reflect wider patterns in digital transformations: benefits accrue when capability, infrastructure, and behaviors co-evolve rather than from the mere adoption of technology.

Another strand foregrounds governance and collaboration. SSCM frameworks emphasize that environmental performance is reliant on cross-firm alignment, supplier development, and credible monitoring [

31,

32]. Digital tools reduce coordination costs and increase transparency but also bring to the fore power asymmetries and data-sharing frictions. The environmental dividend thus depends on the way digital strategies are embedded in governance architectures that distribute incentives and responsibility all across the chain.

In putting these streams together, the literature points to two broad regularities: first, digitalization can lower emissions intensity via planning, visibility, and process redesign; second, the net effect hinges on channel configuration, consumer behavior, and the energy mix. E-commerce magnifies both the opportunities and the risks by reshaping last-mile and reverse logistics, while renewables penetration alters the carbon content of digital operations. This synthesis motivates analyses that treat digital capability and e-commerce not as substitutes but as interacting features of contemporary supply chains.

There is significant evidence at the level of cases and countries, but comparative multi-economy studies distinguishing general digitalization from a specific e-commerce channel in their interpretation about movements in GHG emissions intensity are missing. Many exercises use a proxy of “digital progress” with single indicators or assume online retailing to be uniformly good or bad, thus not indicating how returns, delivery density, and consumer promises actually shape outcomes [

1,

7,

8]. Filling this gap needs designs that explicitly specify an interaction between broad digital capability and e-commerce penetration to reveal whether and where digital depth weakens or strengthens environmental benefits. The second gap is on complementarity conditions, particularly the energy mix powering digital infrastructure and logistics. In the literature, macro studies connect the digital economy to carbon outcomes and energy policy work traces decarbonization pathways, but contributions that quantify how renewables penetration conditions the association between digitalization and supply chain emissions intensity across countries are relatively few. Filling this gap helps to specify under what conditions digital strategies are likely to generate real emissions improvements and when they are more likely to cause displacement or rebound, thus affecting both managerial choices and public policy concerning sustainable commerce.

Digitalization has been associated with planning, inventory, and routing gaining efficiency, but the net relation to emissions intensity rests on demand responses and channel setup. Last-mile geometry is redefined by the e-commerce channel, increasing delivery frequency and able to amplify reverse flows if return rates are high, hence the environmental effect depends on delivery density and promises, as well as packaging practices. In such a setup, the marginal effect of greater digital capability would most probably be more positive where there is deeper penetration of e-commerce, since process efficiencies can occur with even higher transport activity and handling. The energy system further conditions results, since a higher renewable share reduces the carbon content of data centers, electrified fleets, and automated fulfillment, thereby weakening digitalization–intensity associations. From all the previous work, it can be said that the main effect of digitalization is ambiguous; it is context-dependent for the e-commerce channel and energy mix has a moderating role. These insights had inspired an empirical design that estimates the interaction between digitalization and e-commerce, which further inspired an empirical design that examines heterogeneity with respect to the renewable share.

3. Materials and Methods

This study sought to establish whether country-level digitalization has any relationship with the greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions intensity of economic activity in European economies, and under what conditions. The analysis was structured at the front end with a promise of clarity in measurement and discipline in identification, making sure not to hide associational interpretation. Annual data were therefore collected from official statistical sources beginning in 2010 up to 2023; the principal estimation window chosen was 2014–2022 to maximize indicator comparability, while the longer window would help check robustness. An unbalanced panel was retained to avoid ad hoc imputations given heterogeneous coverage across countries and years. Panel safe lags were constructed within countries, and extreme values in merchandise trade were mildly winsorized at the first and ninety ninth percentiles to limit leverage while preserving rank information. Data were extracted from Eurostat’s database and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, and data preparation and estimation were implemented in RStudio version (2024.12.1+563).

Research question (RQ): Does country-level digitalization associate with lower emissions intensity of economic activity, and is this association stronger where e-commerce development is higher and the energy system is cleaner?

Hypotheses tested:

H1. Higher digitalization is associated with a decrease in emissions intensity.

H2. The association between digitalization and emissions intensity is more negative at higher levels of e-commerce development.

H3. The association between digitalization and emissions intensity is more negative where the renewable energy share is higher.

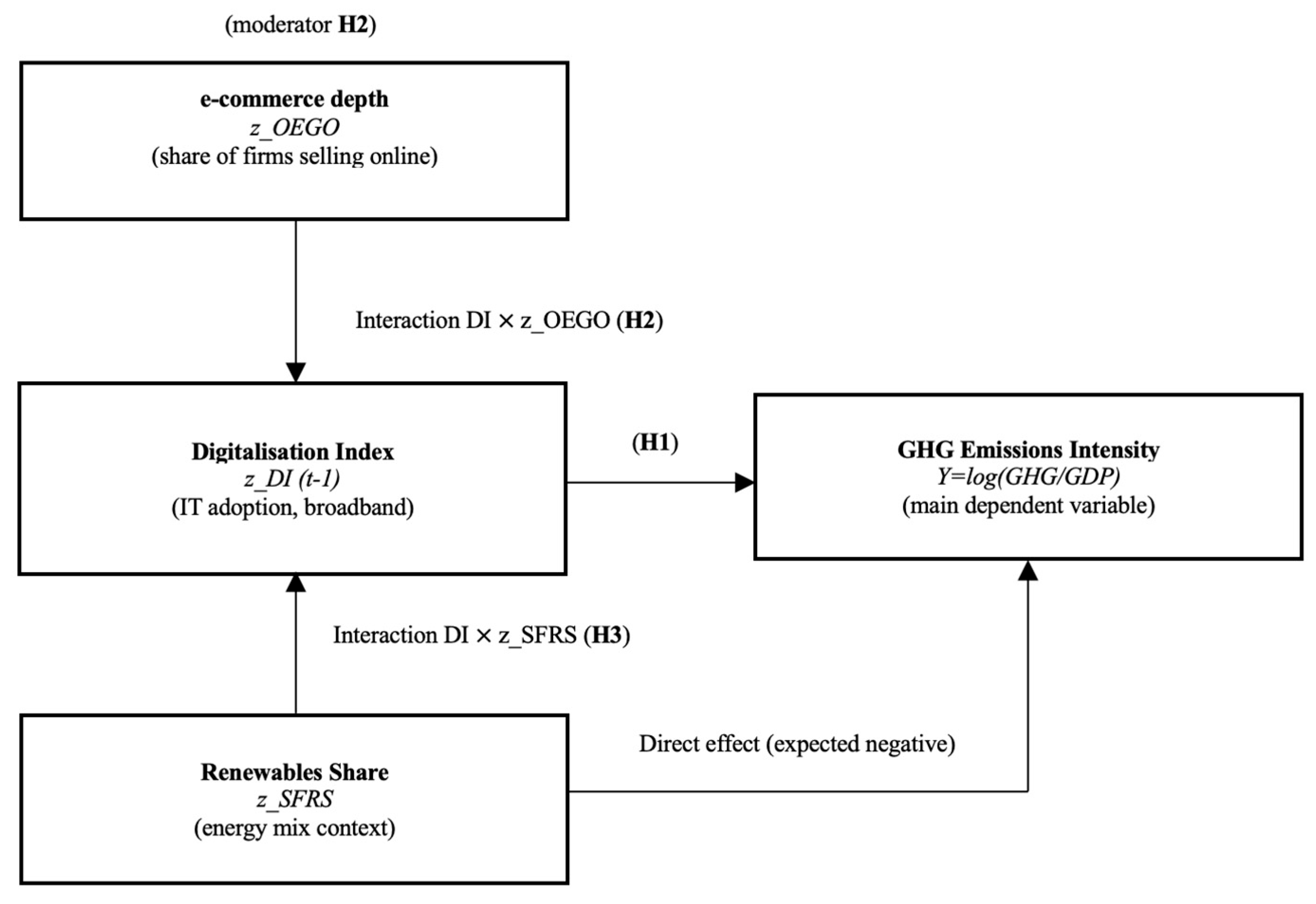

The hypothesized relationships are summarized in the conceptual framework presented in

Figure 1.

The outcome was specified as the logarithm of GHG emissions per unit of output, which yields semi-elastic interpretations and stabilizes skew:

with

i indexing countries and

t years. Robustness outcomes were prepared as log(GHG/POP) and, where available, log(energy intensity), to probe sensitivity to the denominator and to proxied energy efficiency.

Digitalization was operationalized as a capability bundle. Two complementary enterprise-level indicators, ICT uptake and broadband-enabled engagement, were standardized (z-scores) and combined via principal components. Writing

, the first principal component was extracted and re-standardized:

Because channel architecture can shape environmental outcomes, an indicator of e-commerce development (, z-score) was included, together with its interaction with digitalization, , to test H2. Controls comprised log(), lagged gross fixed capital formation , and merchandise-trade intensity (winsorized and standardized). Where available, a renewable energy share was added as a control; the interaction with digitalization is examined in sensitivity analysis.

The baseline relation linked emissions intensity to its own lag, digitalization, and interaction, while absorbing time-variant heterogeneity and common shocks through country and year fixed effects:

With

and

denoting country and year effects. Inference was based on covariance-robust standard errors consistent under heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence, following Driscoll and Kraay [

33] using the finite-sample cut-off

. The marginal effect of digitalization was given as follows:

which was evaluated at empirical quantiles of e-commerce and translated into percentage changes via (

.

Screening and diagnostics were conducted in line with macro-panel practice. Persistence properties were probed using panel unit-root tests of Im–Pesaran–Shin and Hadri [

34,

35]. Cross-sectional dependence was assessed using Pesaran-type CD statistics [

36]. Multicollinearity was inspected through variance-inflation factors; functional-form adequacy was checked using Ramsey’s RESET; and heteroskedasticity and residual normality were examined via Breusch–Pagan and Jarque–Bera tests, respectively [

37,

38,

39]. Results were reported with robust uncertainty quantification rather than relying on homoskedastic assumptions.

As a dynamic robustness, a parsimonious difference GMM design was implemented to mitigate small-sample bias associated with lagged dependence. In first differences,

was instrumented with deeper lags in levels, and—when treated as predetermined—short lags of digitalization (and, in sensitivity analysis, of the interaction) were used as additional instruments. Instrument sets were collapsed and lag depth restricted to conserve test power and avoid proliferation; AR(1)/AR(2) tests in differences and Sargan/Hansen over-identification tests were reported for specification scrutiny [

40,

41]. These estimates were intended to corroborate, rather than replace, the fixed-effects results.

Identification is based on two-way fixed effects that absorb time invariant country heterogeneity and year shocks. Standard errors are estimated using the Driscoll–Kraay covariance in order to address issues of heteroskedasticity, serial correlation and cross-sectional dependence which normally arise in macro-panels. The specification includes a lag of the dependent variable and digitalization interacting with e-commerce so that within-country associations can be retrieved, as well as enabling the marginal effect of digitalization to vary with channel depth. All estimates are interpreted as associations. Dynamic bias and potential endogeneity are probed with difference GMM in first differences using collapsed, depth-restricted instruments. The Arellano–Bond AR(1) and AR(2) tests in differences, together with a Sargan test of over-identifying restrictions, are reported, and the instrument count is kept well below the number of groups.

Data and Variables

Table 1 summarizes the dependent variable as emissions intensity measured by log(GHG/GDP), with alternative outcomes used for robustness as log(GHG/POP) and log(energy intensity). The covariate set merges a composite digitalization index, an independent measure of e-commerce penetration, and their interaction in order to capture channel-contingent effects, together with standard macro controls. Variance-stabilizing transformations (logs), unit comparability promoting transformations (z-scores), and transformations that respect panel structure (panel-safe lags) were selected. Extreme trade observations are mildly winsorized to limit leverage.

The digitalization index results from principal components of standardized measures of enterprise IT adoption and fixed broadband subscriptions per capita, oriented and then re-standardized. It compresses general digital capacity into a single score that varies within and across countries for easier interpretation when interacting with the e-commerce measure. The inclusion of e-commerce in both levels and the interaction with digitalization enables differentiation of broad digital capability from the specific commercial channel through which last-mile logistics and returns occur.

The e-commerce indicator z_OEGO is the standardized share of enterprises selling online or receiving orders via electronic networks from EUROSTAT-ICT; this business-side proxy was selected for cross-country comparability in line with channel configuration, while household purchasing or parcel-volume proxies were not adopted owing to their uneven coverage and weaker linkages to firm adoption. Controls are dual. Trade openness (exports plus imports over GDP) from EUROSTAT and WDI is winsorized at the first and ninety ninth percentiles to limit leverage, then standardized, to capture shifts in production geography and transport volumes that might otherwise be conflated with digital effects. Economic scale and income are represented by log GDP per capita from WDI or EUROSTAT; investment dynamics, by gross fixed capital formation, lagged one year (using panel-safe lags). The standardized share of renewables z_SFRS taken from EUROSTAT-ENER as the share of energy from renewable sources in gross final energy consumption brings in the energy system context within which digitalization unfolds. These definitions and transformations deliver a parsimonious yet comprehensive specification that aligns with the identification strategy and with the robustness analyses reported elsewhere in the paper.

4. Results

This sub-section brings out the major empirical patterns revealed by the plots and statistics in support. Results show a positive relationship between digitalization and emission intensity, which becomes stronger with more penetration of e-commerce, whereas there is a rather strong negative relationship for the share of renewables. There is high persistence for the dependent variable and quite a few good baseline models capturing substantial within-variation.

4.1. Visual Footprint and Identification Checks

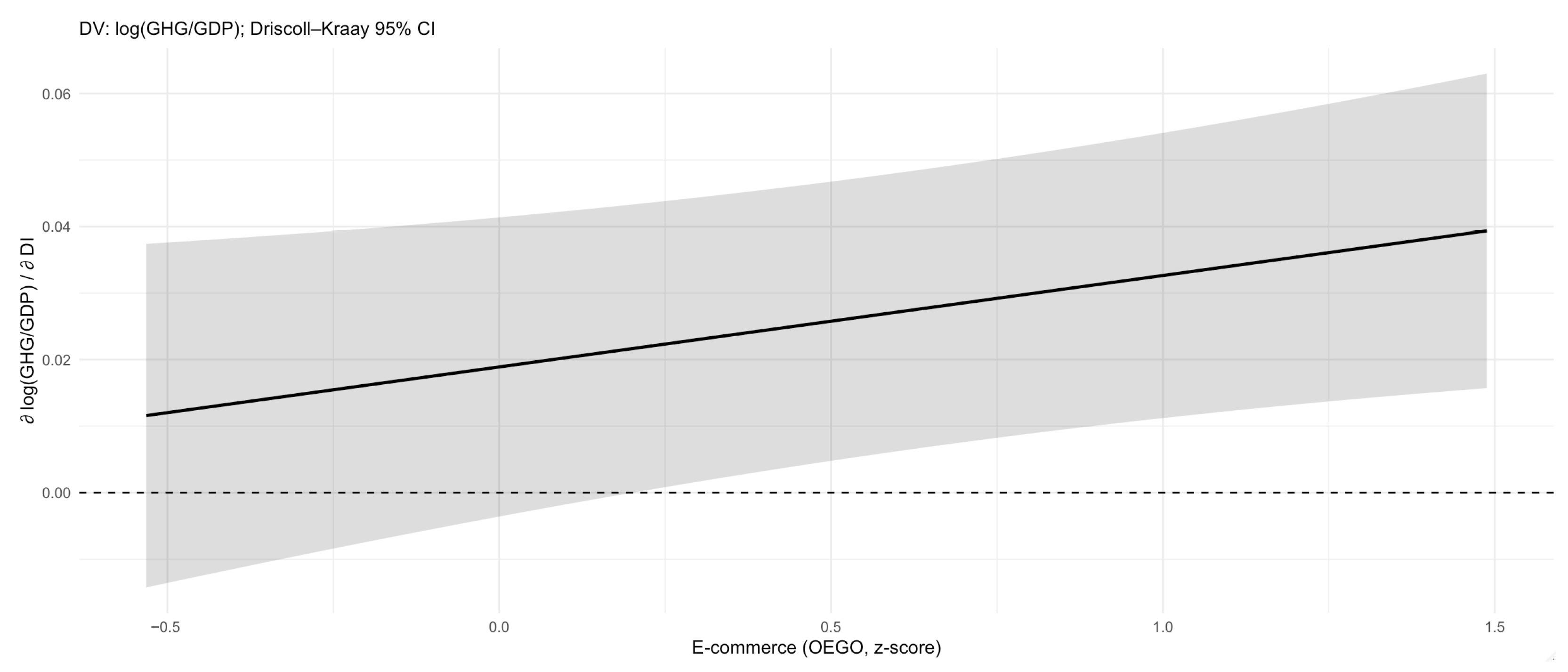

The marginal-effects plot (

Figure 2) displays how the simple slope of digitalization varies across the empirical distribution of e-commerce. The confidence band stays close to zero at low levels of e-commerce and rises through the upper part of the distribution to show a more positive association in more online economies. At representative points, it is estimated at 0.0237 (s.e. 0.0108,

p = 0.0288) at the median of e-commerce and 0.0325 (s.e. 0.0109,

p = 0.0030) at the upper quartile; these translate into semi-elastic changes of about 2.4% and 3.3% in emissions intensity for a one-standard-deviation increase in digitalization.

The form of the band agrees with a path where ordering, storing, and last-step delivery that use digital tools increase faster in places with more online activity. If there are no matching upgrades in the energy sources, this greater flow links to higher emissions for each unit made; when power is cleaner, the same digital ability does not likely increase intensity.

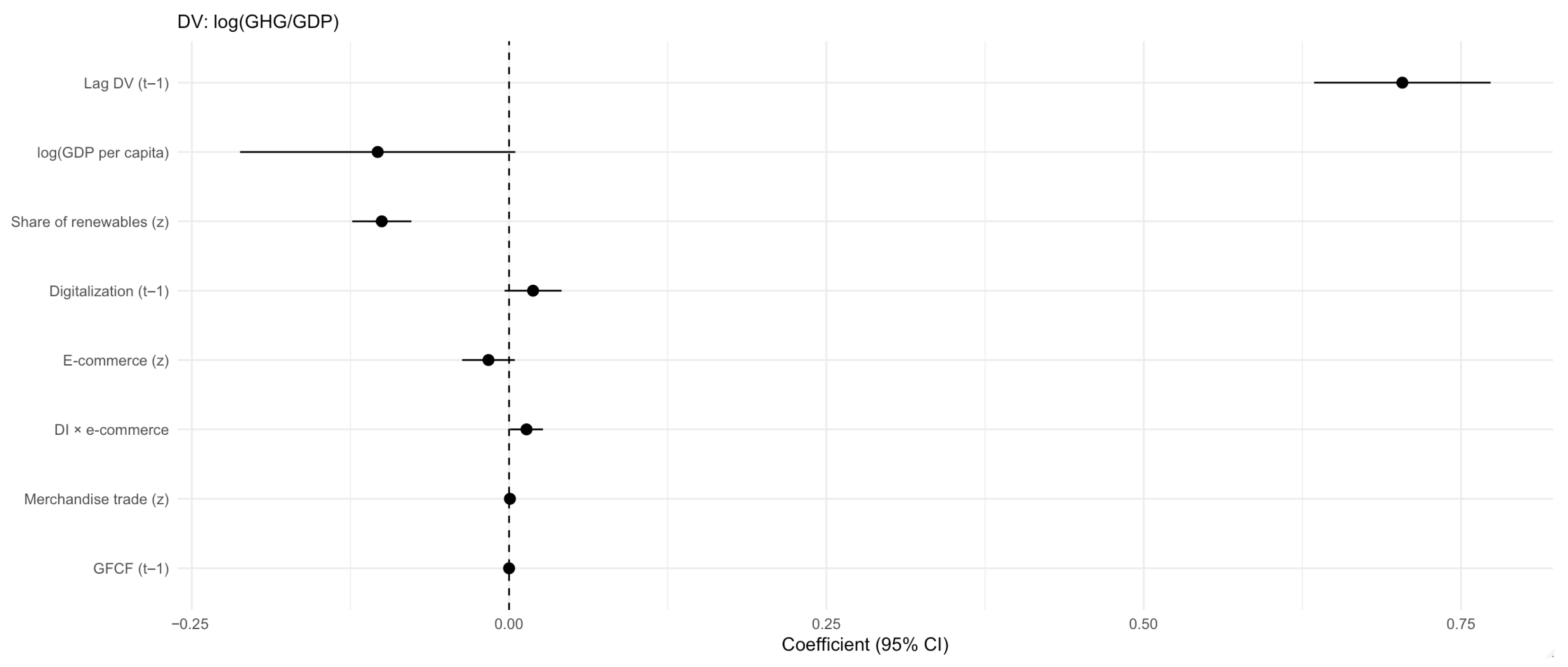

The plot of coefficients (

Figure 3) for the two-way FE model emphasizes three features: First, it shows a large and highly precise estimate for the lagged dependent variable (0.7038,

p < 0.0001)—indicating persistence; secondly, it shows that the interaction between digitalization and e-commerce is positive and statistically significant (0.0138,

p = 0.039), while the lagged digitalization term by itself is only weakly precise (0.0189,

p = 0.101); thirdly, it shows that renewable share is negative and large in magnitude (−0.1003,

p < 0.001)—implying lower emissions per output unit under cleaner electricity systems.

It is not at conventional thresholds that other covariates are significant in the baseline: merchandise trade (0.00068, p = 0.630), main e-commerce term (−0.0162, p = 0.128), lagged gross fixed capital formation (−2.82 × 10−7, p = 0.398), and log GDP per capita (−0.1035, p = 0.063). A joint Wald test for the digitalization block—digitalization and its interaction with e-commerce—rejects the null (χ2 = 11.035; p = 0.004), meaning that as a system, the digital channel is relevant. The model does explain a rather substantial share of within-variation (within R2 = 0.6089).

The interaction of digitalization with e-commerce is positive and statistically significant (

Table 2), while the estimate for the renewables share is large, negative, and well-identified. At the median it is 0.023701 with a standard error of 0.01084 and a

p-value of 0.02879; at the upper quartile it rises to 0.032465 with a standard error of 0.01092 and a

p-value of only 0.00295—approximately 2.4 percent and 3.3 percent changes in emission intensity for one-standard-deviation increases in digitalization, respectively, at their appropriate places in the distribution of e-commerce among countries. This supports an economically meaningful association between carbon output efficiency and online commercial channels, since quite some within-country variations are being captured by this model, within R

2.

The joint test proves that the digital block is germane as a system (Wald χ2 = 11.035; p = 0.00402), and a leave-one-country-out exercise gives a narrow range for the interaction (minimum 0.003433, median 0.013813, maximum 0.018882), thereby proving that results have not been affected by a single country. Robustness can be justified by diagnostic statistics: heteroskedasticity and non-normal residuals (Breusch–Pagan p = 0.00721; Jarque–Bera p < 0.001), while at conventional levels there is no evidence of panel serial correlation and cross-sectional dependence (Breusch–Godfrey χ2 = 12.532, p = 0.08435; Pesaran CD p = 0.1892). The potency of proof hence suggests higher emissions intensity in more online economies for any increase in digital capability and lower intensity where the electricity mix is cleaner.

4.2. Baseline Fixed-Effects Estimates (TWFE with Driscoll–Kraay)

The two-way effects model helps extract three very basic parameters of interest (

Table 3). The lagged dependent variable is big and very accurately estimated (0.7038,

p < 0.001). This already shows strong persistence of emission intensity within countries; digitalization × e-commerce interaction is positive and significant at 0.0138 with a probability value of 0.039, while the lagged digitalization term itself is only weakly precise at 0.0189 with a probability value standing at 0.101. The renewables share enters negatively and with high precision (−0.1003,

p < 0.001). Other covariates are not precisely estimated at conventional levels. R

2 of 0.6089, and a joint Wald test on the digital block (digitalization and its interaction) rejects the null (χ

2 = 11.035;

p = 0.004), confirming the relevance of the channel as a system.

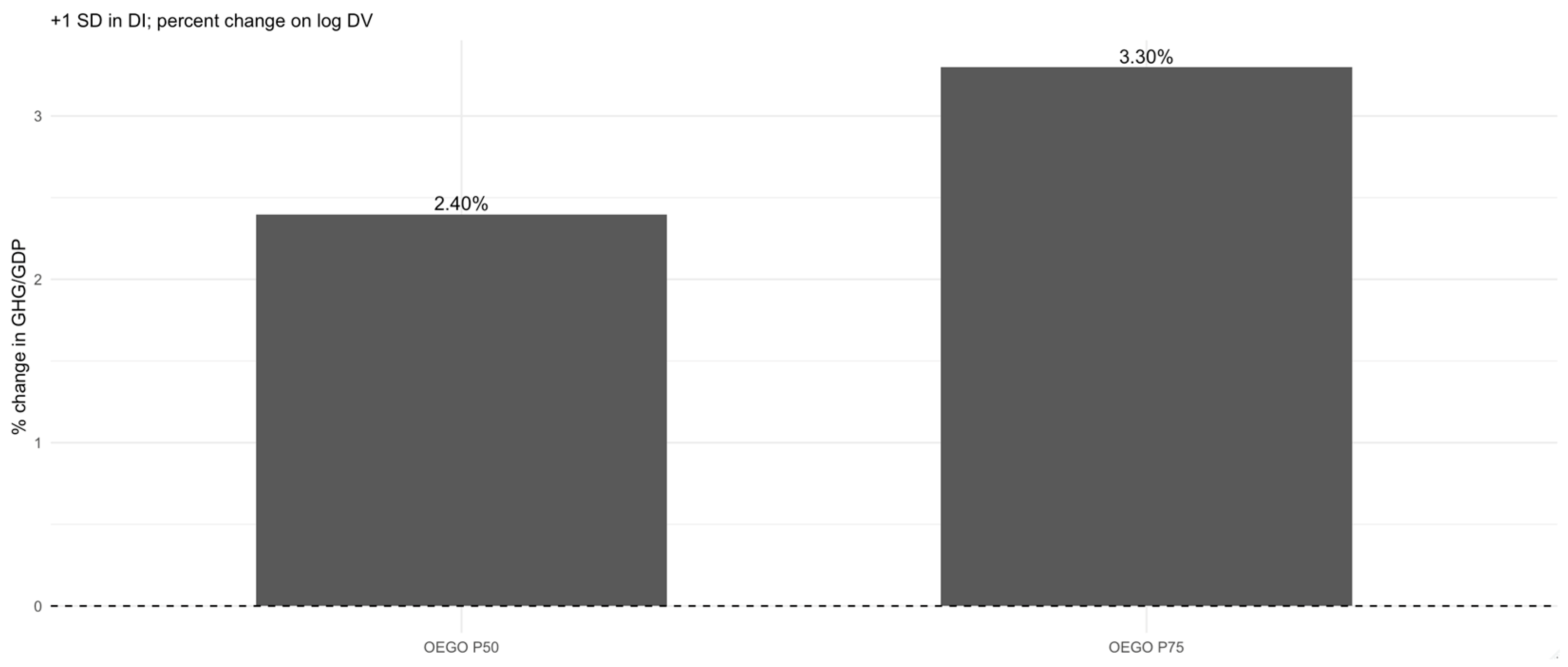

Figure 4 translates the parameterized slope of digitalization into percentage changes in emission intensity at representative points from across the distribution of e-commerce. For a one-standard-deviation change in digitalization, the implied semi-elastic change is about +2.4 percent at the median of e-commerce and +3.3 percent at the upper quartile, with confidence intervals based on Driscoll–Kraay variance–covariance estimation. The relative ordering of the bars shows a very clear gradient from the center to the upper end of the distribution, so that this interaction term can be made sense of economically.

Another look at

Figure 3 dwells on uncertainty: when the upper-quartile bar is well above zero, with intervals around it and the median bar just above zero, this replicates the preciseness of the interaction found. This visual mapping from coefficients to semi-elasticities clarifies how changes in digital capability are related to emissions intensity across different e-commerce contexts, without returning to the visual diagnostics already discussed.

Baseline estimates measure a trend wherein the sensitivity of emissions intensity to digital capability varies with the depth of an online channel, while a higher share of renewables has a positive relation with lower intensity. The large and precise autoregressive term puts on display for all to see the importance of dynamics in emissions behavior at a country level.

Stating the results in effect-size bars brings out the practical dimension across the e-commerce distribution and creates a clear link from parameters to economic interpretation. These features are considered in the next subsection under alternative outcomes, longer windows, country-specific trends, and a parsimonious dynamic GMM design.

4.3. Robustness: Alternative Outcomes, Windows, Country Trends, and Dynamics

The robustness exercises test whether or not the baseline association is sensitive to how the outcome is measured, the time window, the allowance for heterogeneous trends, the choice of covariance estimator, and the dynamic bias.

Table 3 assembles the coefficient on the digitalization × e-commerce interaction under all these perturbations, alongside those diagnostics most focused on precision and identification. Emphasis is a matter of comparability: all figures are drawn from re-estimations and reported on a common scale.

Two broad features emerge before turning to the detail in

Table 4. First, panel variants that keep the 2014–2022 window and a production-based outcome retain a positive interaction with meaningful magnitudes, while alternative outcome definitions or the extended 2010–2023 window reduce precision. Second, allowances that affect inference rather than central tendency country-specific trends, clustered errors, or dynamic instruments modify standard errors and test statistics in predictable ways without flipping the sign of the interaction. Robustness checks include difference GMM estimates in first differences with collapsed instrument sets and the associated AR and over-identification diagnostics, as summarized in

Table 4.

The upper segment of

Table 3 displays the fixed-effects versions. The baseline coefficient on the interaction amounts to 0.01375 (

p = 0.0391). Precision strengthens with GHG per capita as an outcome and so does magnitude (0.02013;

p = 0.00452). In the window extended to 2010–2023, the point estimate reduces to 0.004997 with imprecise signaling (

p = 0.5428), though its digital block is jointly relevant (Wald χ

2 = 9.287,

p = 0.0257). When energy intensity is used as an outcome, it turns out slightly negative and statistically not different from zero (−0.005827;

p = 0.3194), indicating that this association depends on how intensity is proxied on the energy side.

Allowing for country-specific linear trends reduces precision—β = 0.01652 with p = 0.1175—and pushes the block-wise test closer to the 10% mark (χ2 = 5.040; p = 0.0805). This matches what happens when a lot of slope dummies eat up degrees of freedom. Changing from Driscoll–Kraay to cluster-by-country errors does not move the point estimate (it stays at 0.01375) but makes the interval wider (p = 0.2862), which shows up when inference comes only from cross-sectional clustering.

The pandemic tests offer a helpful standard for extreme surprises. A single-way FE model shows a mean drop in emissions intensity during 2020–2021 (dummy = −0.02833; p = 0.0409). Within the TWFE, the mix DI × COVID is negative and very exact (−0.05098; p ≈ 0.000364), hinting that the digitalization–intensity tie grew weaker in that time, while OEGO × COVID does not matter.

Dynamic tests with difference GMM have reported satisfactory results for the second-order serial-correlation test across designs (for instance, AR(2) p = 0.7291 in the two-step model with DI predetermined). That two-step specification gives a marginally positive interaction (0.07457; p = 0.0730) where instruments are almost valid (Sargan p = 0.0642). Directly instrumenting the interaction tightens the Sargan test (p = 0.0370) and does not add precision (0.01272; p = 0.7376). On balance, these diagnostics support treating the fixed-effects estimates as the primary evidence, with GMM corroborating that the headline patterns are not artifacts of dynamic bias.

5. Discussion

This study poses a question of whether at the country level digitalization has any relation to the greenhouse gas emission intensity of economic activity and under what circumstances this relationship changes its sign or magnitude. The evidence pointed out a conditional association; digital capability does not always go hand in hand with low intensity, it is more likely to be associated with high intensity where online commercial channels are deeper, and less carbon-intensive where the electricity mix includes a larger share of renewables. This is consistent with the findings accumulated so far, which indicate that efficiency is enabled through digital tools while at the same time encouraging rebound and scale effects, on the one hand, and that cleaner power systems move production toward lower carbon per unit of output [

42,

43,

44,

45] on the other. The evidence is of a conditional relationship: digital capability does not associate with lower intensity everywhere; it is more likely to associate with higher intensity where online commercial channels are deeper, and it is less carbon-intensive where the electricity mix includes a larger renewable share. This configuration fits accumulated results that digital tools deliver efficiency while also stimulating rebound and scale effects, and that cleaner power systems push production toward lower carbon per unit of output.

There is no support for an unconditional emissions intensity reducing as digitalization increases, i.e., for H1. The positive moderation by depth of e-commerce indicates that H2 is rejected (we find the opposite sign): as e-commerce deepens, the association between digitalization and intensity becomes more positive. The renewable energy share comes in larger with lower intensity, and this context weakens the positive digital–intensity link, H3, consistent with work linking power-sector decarbonization to macro-level carbon reductions [

7].

In high e-commerce scenarios, the positive relationship between digitalization and emissions intensity can be read through the shape of last-mile logistics and reverse flows. Digital tools reduce search and ordering friction, widen assortment visibility, and support very responsive fulfillment promises; in dense online markets this usually increases order frequency and basket fragmentation. When delivery windows are short, returns are free, and packaging is optimized for speed not volume then logistics networks must build in service quality rather than consolidation, meaning more vehicle kilometers with partial loads and repeat visits to the same neighborhoods. Even though routing, inventory management, and planning of capacity improve on a per-trip basis, total flows of parcels, packaging material, and reverse shipments can increase fast enough to more than offset such gains. In this respect, digitalization becomes less an alternative to physical mobility and more an accelerator of the volume of transport activity in the most carbon-intensive stretches of the chain.

From an economic perspective, the interaction can be understood as a rebound mechanism through the generalized costs of online consumption. Deepening digital capability reduces the fixed and variable costs of running e-commerce platforms, personalization recommendations increase conversion rates, and perceived time and effort for consumers to order drops. In mature e-commerce ecosystems this combination widens both the intensive and extensive margins of demand—more households participating and existing users placing more frequent smaller orders, often packaged with generous delivery and return conditions in the price. A one-standard-deviation increase in digitalization associated with intensity increases of around 2.4 to 3.3 per cent at the median and upper quartile of e-commerce is consistent with these mechanisms: efficiency improvements in planning and execution are present, but in highly digital and online economies, they are more than offset by additional transport and material throughput. Where e-commerce penetration is low, the rebound channels are weak, and digitalization primarily acts through back-end optimization, which helps explain the much more modest association with emissions intensity in those parts of the distribution.

Channel-specific mechanisms determine those results. Net emissions are very strongly influenced by delivery density, load factors, routing, packaging design, and especially return rates, which are the subject of comparative analysis between online and store-based retail; small shifts in these elements can even change the direction of the effect at system level. Digitalization reduces search and transaction costs, hence increasing order frequency and assortment variety, and therefore expanding last-mile movements unless consolidation and reverse-logistics efficiency improve in parallel.

The energy-system context acts as a structural moderator of that relationship. Where electricity is in the process of decarbonizing, sensor-rich coordination, predictive analytics, and platform-enabled orchestration come in absolute emissions savings rather than increases driven by rebound effects. Studies on renewable deployment reveal that increased penetration of renewables decreases the carbon intensity; however, evidence about network electricity consumption and the broader ICT ecosystem highlights the imperative to align digital scaling with low-carbon power [

44,

45,

46].

Practical implications flow for operations and policy. Firms expanding online channels can reduce intensity by raising delivery density with consolidated pick-up points, and avoiding returns which are not preventable by providing more precise fit/size guidance, as well as by redesigning packaging to lower its volume and improve recyclability. Public policy can multiply these effects through accelerating renewable integration and charging infrastructure, as well as by setting urban-logistics standards that favor low-emission fleets and consolidation.

This conditional view reconciles the mixed results of studies on ICT and environmental outcomes. Studies reporting reduction mostly operate from perspectives involving greener grids or high-density delivery geometries; studies finding increases mostly capture contexts in which demand growth exceeds decarbonization or wherein packaging and returns constitute the footprint. Specifying the moderators—market architecture of commerce and electricity mix—brings theory and empirics into closer alignment. The practical implications for operations and policy are that firms expanding online channels can reduce intensity by raising delivery density, using consolidated pick-up points, preventing avoidable returns by improved fit/size guidance, and redesigning packaging to lower volume and improve recyclability. In addition to magnifying these effects through accelerated renewable integration and charging infrastructure, plus urban-logistics standards favoring low-emission fleets and consolidation, public policy can also play a role.

There are also lessons at system level. Work on viable supply chains emphasizes the joint pursuit of agility, resilience, and sustainability; digital tools enable sensing and rapid reconfiguration, but the environmental pay-off emerges when carbon-intensity metrics are embedded alongside cost and service in decision rules [

47]. Evidence on data-analytics and AI capabilities suggests performance and resilience gains that can be steered toward decarbonization when targeted at low-emission routing, consolidation, and energy-aware scheduling [

48,

49].

5.1. Implications in High E-Commerce Settings

Where there is high advanced digitalization and penetration of e-commerce, channel design could consolidate such that delivery density increases and empty miles are reduced. High footfall nodes may host lockers and pick up and drop off points; delivery windows can be priced to steer demand into aggregable slots; and routing can be updated dynamically to lift load factors—all summarized in

Table 5. The order volume served with fewer kilometers per order and at a higher share of successful drops lowers emissions intensity for this level of digital activity.

The reverse flows and packaging will adjust right away. Unpreventable returns shrink with size and fit aid, virtual try-on, and clearer product details, while all returns can be pooled through planned grouped pickup with refurb triage to stop repacking and forwarding transport. Packaging redesigns toward less bulk and reuse with checked recyclability, as well as traceable supplier goals, means that mass drops per order and handling steps fall too. These operating changes match a cleaner energy base with renewable electric buying for hubs, data homes, and the electrifying of delivery truck groups at their spots.

Implications for measurement and coordination are enabled. Intensity reporting can be shifted from order averages to route and product category granularity, and channel level indicators can be disclosed so that decisions are managed by outcome. Secure sharing of anonymized route and locker usage data with contracted partners can sustain network-level optimization without ever having any need to disclose sensitive information. In combination, these steps translate the estimated associations into firm-level practices that align digital capability with consolidation and a lower carbon energy mix.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

An unbalanced panel was employed, and proxies drawn from public statistical sources were used for digitalization and e-commerce, which introduces the possibility of measurement error and of incomplete coverage of capabilities that shape logistics design and network configuration. The digitalization index was derived from two enterprise indicators through a principal component approach, so dimensions such as data quality, interoperability, and analytics depth may not be fully reflected. The outcome was specified as territorial emissions per unit of output, which does not capture shifts in the location of the footprint that would be visible under consumption-based accounting. Identification was associational, with country and year effects and Driscoll–Kraay inference addressing common features of macro-panels, while time-varying country factors that are not observed may persist. Difference GMM was used to probe dynamic bias and endogeneity with collapsed and restricted instruments, and diagnostic power was necessarily limited. Estimates were produced at country level, which constrains the representation of firm and sector heterogeneity in last-mile geometry, return policies, packaging practices, and energy sourcing.

Further progress would be enabled by micro data that link firm-level digital adoption to order frequency, delivery density, return flows, and metered electricity use, and by quasi-experimental designs that exploit exogenous changes in renewable capacity, urban logistics regulation, congestion pricing, or return policy rules. Richer proxies for e-commerce that distinguish penetration, turnover, product category mix, delivery promises, and reverse logistics intensity would support a more granular decomposition of mechanisms. The integration of consumption-based emissions, the extension beyond Europe, and the analysis of threshold and nonlinear responses across urban forms and grid carbon intensities would allow for stronger causal claims and clearer guidance for channel design and energy strategy.

6. Conclusions

The analysis suggests that digitalization alone fails to uniformly reduce greenhouse gas emissions intensity at the national level. Instead, the relationship is conditional. The relationship between digital capabilities and emissions intensity is more positive in regions with more prevalent e-commerce and more negative in regions with a higher share of renewable energy in the energy system. The significant autoregressive component suggests that national emissions intensity trajectories are persistent, so short-term changes in digital capabilities can offset strong background trends. Taken together, these results address the research question by clarifying under what circumstances digitalization is associated with environmental improvements and when it is likely to increase production.

These patterns have economic explanations. Digitalization expands product variety, reduces search and ordering processes, and redesigns order fulfillment methods; even without high delivery density, efficient reverse logistics, and packaging redesign, increased convenience can increase last-mile activities and material volume. In contrast, a cleaner power mix can reduce the carbon content of data-intensive operations and electrified logistics, so coordination benefits can translate into real intensity reductions. Therefore, the moderate adoption of renewable energy reframes digitalization strategies as a complement to, rather than a substitute for, energy sector decarbonization.

From a business perspective, the findings point to levers that businesses and governments can leverage. On the business side, these levers include focusing on integrating delivery and collection networks, reducing avoidable returns through better tools and information, and redesigning packaging to reduce bulk and increase recyclability. On the policy side, these levers include accelerating the integration of renewable energy and charging infrastructure and adopting urban logistics standards that promote low-emission fleets and integration. The message is clear: when channel design and energy systems evolve together, investments in digitalization will pay off for the environment.

Several limitations restrict the scope of inferences. The panel data are unbalanced by design to avoid imputation. While this maintains data integrity, it may reduce precision in some country/year cells. Some important concepts are replaced by official indicators—for example, enterprise IT employment and fixed broadband subscriptions per capita in the digitalization indicator, as well as standardized indicators for e-commerce and renewable energy—so measurement error cannot be ruled out. Winsorization of goods trade and country-specific scaling decisions are reasonable but may affect the behavior of extreme values. All estimates are based on production-based emissions intensity accounting.

A second set of limitations concerns identification. The two-sided fixed effects in the Driscoll–Kraay inference address many issues with macro-panel data but cannot completely eliminate endogeneity caused by omitted, time-varying country factors or policy expectations. The difference-in-difference generalized moments estimation helps mitigate dynamic biases and provides convergence patterns, but the instrument set is deliberately conservative to avoid data explosion, which may limit explanatory power. The “exact identification” approach used in some specifications also limits tests of over-identification. While such structural changes always complicate attribution analysis, further research is needed on the impact of the pandemic period.

Future research could deepen and refine these mechanisms. Micro-data linking firm-level digital adoption with freight-level logistics, return flows, and metered electricity consumption would provide a clearer decomposition of channel and energy effects. Quasi-experimental designs around exogenous changes (renewable energy capacity expansion, electrification of delivery services, congestion or parking reforms, and adjustments to return policies) would strengthen evidence of causality. Expanding the scope of the study beyond Europe and disaggregating by retail category, neighborhood structure, and grid carbon intensity would reveal where digital scale can reliably reduce emissions intensity. Finally, integrating consumption-based carbon emissions measurements would reveal whether observed regional intensity changes reflect actual efficiencies or cross-border migration.