1. Introduction

The extensive application of big data technology and the ongoing advancement of e-commerce have enabled firms to effectively collect consumer purchase data and conduct in-depth analyses of consumer purchasing behavior. By leveraging consumer purchase history (e.g., purchase frequency, price sensitivity), retailers can accurately identify the heterogeneous preferences of new and old consumers. This enables them to carry out behavior-based pricing (BBP) [

1,

2] in conjunction with behavior-based quality discrimination (BBQD) [

3]. For instance, Meituan Hotel provides a discount of “20 RMB off the first order” to new users, while Amazon facilitates user conversion by offering exclusive discounts to new consumers. Simultaneously, iQiyi grants high-definition quality privileges to new members, and Amazon Prime as well as Taobao 88 VIP members enjoy priority shipping rights, which help reduce logistics times. It is clear that the strategy of aligning user needs through differentiated pricing or service quality has become a critical tool for firms to enhance revenue and improve user retention [

4,

5,

6].

In particular, in recent years, BBP has been extensively adopted across industries such as telecommunications, insurance, e-commerce, airlines, and hotel reservations. Firms utilize this form of price discrimination to either poach competitors’ consumers or enhance their own profits [

7]. However, since waiting time (e.g., logistics delivery time, food delivery time, and the estimated arrival time for ride-hailing services) is also a crucial factor affecting purchasing decisions for some consumers beyond price, such consumers are categorized as time sensitive. For instance, a related survey report indicates that 87% of online shoppers view delivery speed as an essential factor in shaping their online shopping choices, while 67% are willing to spend more for same-day delivery.

In particular, Shen et al.’s study (2024) [

8] conducted a data analysis of transaction-level data for a single product category on JD.com Mall from 1 to 31 March 2018. These data include 9159 stock unit transactions and 486,928 customer purchase orders. They reveal that committed delivery date criteria play a crucial role in consumer purchase decisions. The data results show that consumers are willing to pay a premium for JD.com resale products and are willing to pay a price premium for a shorter promised delivery time [

8,

9]. Thus, the promised delivery time displayed for a product is a critical factor influencing consumers’ willingness to pay and firm profits. Additionally, a substantial body of research has demonstrated that the connection between delivery speed and sales is evident in various retail settings, such as interior design and furniture [

10,

11], personalized photo products [

12], and clothing [

13]. For example, Zhang and Song (2017) studied the effect of delivery time on furniture sales based on the Chinese market [

14].

Therefore, to meet consumers’ personalized needs and enhance their competitiveness, some firms have gradually adopted the behavior-based delivery time strategy (BBT). For instance, in his 2020 letter to shareholders, Jeff Bezos highlighted that Amazon Prime enables 200 million global users to receive fast and free delivery of millions of eligible online products within two business days. Prime members can opt for free “same-day” or “next-day” logistics services for millions of items. This is because Amazon can automatically assign the nearest warehouse node to frequent Prime members based on historical order data, thereby further reducing the delivery time. Vakulenko et al. (2022) [

15] emphasize that, against the backdrop of growing e-commerce and the increasing number of e-consumers globally, e-retailers and logistics service providers must differentiate and customize their offerings to refine their operations and better satisfy consumer needs. Their study found that distribution differentiation may benefit all market participants. According to the above description, existing technologies enable firms to selectively offer different prices and promised delivery times to consumers, thereby meeting more consumers’ personalized needs while ensuring that goods are delivered within the promised delivery time.

Despite Amazon Prime achieving tremendous economic success and receiving widespread acclaim, few studies have rigorously quantified the economic value, consumer welfare impact, or public policy implications of the various terms in the subscription program. Thus, we demonstrate the necessity of our research from two perspectives. On the one hand, the economic value of the delivery time strategy in Amazon Prime’s terms, changes in consumer welfare, and market competition have yet to be rigorously quantified; on the other hand, existing studies have predominantly analyzed the single-dimensional effects of price or delivery time in isolation, with limited exploration of the dynamic interaction mechanism between the two within the framework of behavioral discrimination. For instance, how do firms influence consumer choice and firm profits when implementing differential pricing and differentiated promised delivery times simultaneously? These theoretical gaps constrain firms’ abilities to operate precisely for time-sensitive consumers.

Actually, dynamic behavioral discrimination strategies are already pretty common. Especially in today’s platform economy, platform firms often use historical purchase records (such as initial consumption frequency and price sensitivity) to build a second-stage differentiation strategy to dynamically adjust the next period’s price and service strategy. For example, the “the longer you wait, the more expensive it gets” phenomenon with DiDi and Uber ride-hailing services, where if the platform detects that you have canceled orders multiple times, it will dynamically adjust the quote to test your willingness to pay. This will spark new forms of competition in terms of consumer data value mining and joint strategies. The dynamic price adjustment of ride-hailing platforms is a typical scenario of adjusting current strategies (the second period) based on historical behavioral data (the first period). However, traditional static theoretical research mechanisms have difficulty effectively responding to the complex heterogeneity of consumer behavior due to their static and homogeneous characteristics [

4]. Therefore, considering that consumers are becoming increasingly strategic, this paper constructs a two-period dynamic game model that is more in line with the increasingly complex business environment.

According to Abdellaoui and Kemel [

16], consumers exhibit varying degrees of perceptual sensitivity across the two dimensions of price and time. Therefore, when targeting time-sensitive consumers, how firms can simultaneously fulfill consumers’ personalized needs and enhance their shopping experience in both price and time dimensions has garnered significant attention [

17,

18,

19]. To address the current research gap and investigate the unique impact of this information-driven personalized strategy, we primarily focus on the following research questions:

- (1)

When targeting time-sensitive consumers, how can firms make joint decisions on promised delivery time and price across different scenarios (uniform pricing and uniform promised delivery times; differential pricing and uniform promised delivery times; differential pricing and differentiated promised delivery times) when adopting behavior-based pricing and promised delivery time strategies?

- (2)

In a two-period dynamic game, what are the optimal decisions for the firm in each period?

- (3)

How do different promised delivery time strategies impact the firm’s profits in each period?

- (4)

What are the implications of behavior-based pricing and promised delivery time strategies for consumer surplus and social welfare?

In order to tackle these challenges, this paper develops a two-period dynamic game model. We examine the effects of behavior-based pricing (BBP) and behavior-based promised delivery time strategies (BBT) by considering two horizontally differentiated firms that sell products A and B to customers in the market. In the first period, firms opt for uniform pricing (UP) with uniform delivery time (UT) due to the lack of consumer purchase history. Consumers’ options in the first period reflect their inherent preferences, and their purchase history information in the first period is identified and recorded by firms, enabling the firms to segment the market in the subsequent period. In the second period, firms decide whether to segment the market based on the consumer identification data collected in the previous period. If the market is segmented in the second period and firms implement BBP or BBT, they will present distinct prices to new and old consumers, respectively, or provide differentiated promised delivery times. We primarily analyze the following three scenarios by considering the strategic choices of firms: UP and UT (UU); BBP and UT (DU); BBP and BBT (DD). We not only derive the optimal decisions for firms under each scenario but also carry out an in-depth analysis of consumer surplus and social welfare.

We obtain several noteworthy findings. First, while the classic conclusion of BBP is that firms offer high prices to old consumers and low prices to new consumers, the results of BBT are the opposite. That is, firms should offer shorter delivery times to old consumers and longer delivery times to new customers. Second, while BBP intensifies price competition among firms, BBT helps to mitigate competition, but it exacerbates the price differences between new and existing consumers. That is, it further reduces the price for new consumers and raises the price for old consumers. In addition, the differentiated delivery time strategy enables firms to adjust the promised delivery time appropriately, which may alleviate some of the delivery pressure on firms. Finally, we also derive some important conclusions by analyzing changes in firm profits, consumer surplus, and social welfare. The differentiation strategy may reduce firm profits, but it will benefit consumer surplus. In particular, under certain conditions, the joint strategy of BBP and BBT will increase the welfare of the whole society. These findings particularly emphasize the interplay between behavioral discriminatory strategies across different dimensions, enriching our understanding of discriminatory strategies under consumer heterogeneity and time preference from both price and logistics service perspectives, and provide valuable theoretical insights for e-commerce operations and policy design.

This paper has the following main contributions. First, it contributes new knowledge to the emerging problem of behavioral discrimination in the digital economy context. It provides a theoretical explanation for the phenomena of “price differentiation” and “logistics service differentiation”. Our study fills a gap in the literature, which tends to consider the effects of the two individually, neglecting the mechanism of their mutual influence. Second, we construct a two-period dynamic game model considering a joint price and time decision problem, test that both price and logistics services are effective means of implementing discriminatory strategies, and develop a stream of the literature on behavior-based price discrimination. In particular, we demonstrate that firms can strategically target consumers by adjusting prices flexibly and committing to specific delivery times. We test the robustness of our main conclusions through specific extensions. Third, the findings also provide many insights for managers. These insights concern how firms can make optimal decisions when adopting differentiation strategies, such as pricing and logistics services, in dealing with strategic consumers. This approach will help firms retain existing customers and acquire new ones. Finally, in addition to the theoretical contribution, the findings obtained from this study provide valuable recommendations for government regulators in the formulation of relevant public policies, particularly in regulating digital markets and consumer rights.

The rest of the structure of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 3 elaborates on the model construction and game sequence.

Section 4 solves the model and obtains the optimal decisions of firms regarding pricing and promised delivery time under the three scenarios, respectively.

Section 5 examines and analyzes the equilibrium results across the scenarios to draw the main conclusions of this paper and further investigates the impacts of behavior-based pricing and promised delivery time strategies on firm profits, consumer surplus, and social welfare.

Section 6 extends the main model, relaxes several key assumptions, and tests the robustness of the model.

Section 7 reviews and summarizes the entire paper and explores future research.

2. Literature Review

The main topics related to our research encompass both BBP and joint decision-making on pricing and delivery time.

The first stream of the literature focuses on BBP. Many domestic and foreign scholars have examined it from multiple perspectives and directions. Villas-Boas (2004) and Tirole (2000) arrived at the classic conclusion that, in a horizontally symmetric duopoly market, BBP intensifies market price competition, thereby reducing firm profits [

20,

21]. Esteves and Reggiani (2014) found that, in a market context with variable demand elasticity, BBP reduces firm profits while increasing consumer surplus compared to uniform pricing [

22]. Chen et al. (2021) analyzed social welfare under differential pricing versus uniform pricing for symmetric costs and homogeneous products and found that differential pricing is more likely to enhance consumer surplus [

6]. As consumers become more strategic, some literature has extended the analysis of BBP by considering consumers’ fairness concerns [

23,

24]. In addition, BBP research is closely related to service-level decision-making [

25,

26], information disclosure [

27,

28], quality differentiation [

29,

30], and product innovation [

31]. Among them, Li et al. (2025) [

29] investigated the unique effects of BBP in an asymmetric environment in the experience goods market. Jing (2016) [

30] proposed shifting price competition under BBP by selling quality-differentiated products, and his research focused on the impact of BBP on product quality differentiation. Li (2021) extended a typical two-period dynamic game model of BBP by investigating how firms differentiate service quality based on consumers’ purchase history, revealing the link between product quality differentiation and price differentiation [

3]. This paper differs from the above studies in that it integrates promised delivery time into the two-period dynamic game model and examines the two-period dynamic game under the dual dimensions of price and time.

The second stream of the literature focuses on joint decision-making regarding pricing and delivery time. This literature stream encompasses two critical dimensions: pricing and delivery time. Drawing from the first stream of the literature, the influence of price on consumer purchasing decisions is self-evident. Indeed, time-sensitive consumers represent the most prevalent type of consumers encountered in the retail market. Goebel et al. (2012) identified and explored the potential of time-based delivery, a novel service that enhances convenience at the intersection of retailers and consumers [

32]. Some researchers have investigated and analyzed retailers’ delivery service strategies, with particular emphasis on delivery time [

9,

33,

34]. Among them, Wang et al. examined the combined competition between promised delivery time and demand and analyzed the strategic entry of trunk airlines into the regional transportation service market and its impact on existing regional airlines [

33]. In the study by Cui et al. (2024), the disclosure strategy of delivery speed not only influences timely consumer demand but also affects purchase decisions related to future consumer demand [

12]. By reviewing the existing literature, we observe that most studies have disconnected the relationship between price and time, analyzing their individual effects separately.

Some researchers have addressed this limitation by initiating studies that consider both price and time dimensions. Next, we will review this literature. In the field of queuing economics, Yang et al. (2014) initially incorporated time-based competition into their analysis [

35]. Furthermore, Yang et al. (2018) extended their research by analyzing how the reference effect influences service systems, taking into account customers’ loss aversion to both product price and waiting time [

36]. In particular, we reviewed the literature on the interaction between price and delivery time, revealing that some scholars have investigated the trade-offs faced by time-sensitive consumers in both delivery time and price dimensions [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Among them, Amorim et al. (2024) examined consumers’ preferences for three logistics service attributes: speed, accuracy, and timeliness. Their findings indicate that consumers view speed as an essential attribute of delivery services while also regarding accuracy and timeliness as key factors influencing their purchase intentions [

40]. In particular, Leng et al. (2024) examined how the disclosure of product delivery information influences consumer behavior, when customers are sensitive to price, delivery reliability, and promised delivery time [

18]. Wen et al. (2022) revealed that firms should offer consumers higher product quality and faster delivery times in markets where consumers are sensitive to product quality or delivery time [

41]. A review of the existing literature indicates that in recent years, an increasing number of scholars have focused on consumer time sensitivity, no longer restricting their research to single pricing studies. However, in the context of product delivery time, most studies have overlooked the connection between retail price and delivery time, and our work addresses this gap.

With the growth of e-commerce retailing, e-commerce companies can develop marketing strategies with a deeper understanding of customer behavior by tracking the purchasing habits of potential customers and the purchasing history of existing customers. This plays a crucial role in attracting new customers and retaining existing ones [

42]. Therefore, in this paper, we specifically investigate the impact of price and delivery service strategies. In fact, consumer preferences and sensitivities to service attributes may differ significantly [

43,

44], and some customers might not place a high priority on speed or accuracy because of other factors (e.g., scheduling flexibility or constraints, retail price discounts). By detecting changes in customer preferences and encouraging some customers to opt for flexible delivery times, firms may be able to alleviate delivery affordability while preserving consumer satisfaction. Achieving this balance could offer valuable contributions to both the theoretical understanding and practical applications in retail distribution marketing [

45]. Therefore, this paper explores the connection between product delivery time and selling price from the two perspectives of behavior-based pricing and promised delivery time, providing new insights into achieving such a balance.

In summary, in conjunction with the relevant background and the aforementioned related literature, it is evident that an increasing number of scholars have focused on the individual effects of product price and promised delivery time in various scenarios. Therefore, there are three primary distinctions between our study and the literature mentioned above:

- (1)

We explicitly include market segments shaped by consumer behavior in our analysis, aiming to reveal the fundamental difference between price and logistics services under a behavior-based discrimination strategy;

- (2)

This study incorporates promised delivery time into a canonical two-period dynamic game model of BBP, extending the single-dimensional pricing decision to a two-dimensional decision involving both price and delivery time;

- (3)

In particular, we emphasize the interplay between price differentiation and delivery time differentiation strategies. Building on this, the study focuses on time-sensitive consumers as the research subject, aiming to examine the impact of behavior-based pricing and promised delivery time strategies adopted by firms, under the time-sensitive characteristics of consumers, on product prices, promised delivery times, firm profits, consumer surplus, and social welfare.

5. Equilibrium Results Analysis

This section first compares the firm’s optimal price and promised delivery time in both periods under the above three cases, then compares equilibrium profits, and finally analyzes changes in consumer surplus and social welfare. Referring to previous research [

7,

25], considering that firms A and B are symmetric in the duopoly market in this paper, we explain the equilibrium results from the perspective of firm A. In

Section 6.1, we analyze the asymmetric case to enrich our study. The proofs are presented in the

Appendix B.1.

Proposition 1. The relationship between equilibrium prices in each case:

- (1)

, , .

- (2)

, .

Proposition 1 (1) reveals that in both DD and DU cases, firms offer their products to both new and old consumers for less than a uniform price in the second period. Furthermore, in order to maximize the total profit in the two periods, firms provide product prices in the first period that are lower than the uniform price under uniform pricing. This indicates that when firms adopt BBP, they increase the price of products in the first period and decrease the price in the second period, with different changes in prices between the first and second periods. Meanwhile, indicates that the inclusion of the promised delivery time can appropriately curb first-period price increases and mitigate the intensified product price competition due to the adoption of BBP.

Proposition 1 (2) explicitly analyzes the optimal price that firms provide to both new and existing consumers when adopting BBP. The study finds that, regardless of whether the impact of promised delivery time is considered, under both the DD and DU cases, the prices provided by firms to new consumers are consistently lower than those provided to old consumers, which means that the BBP strategy is essentially a form of “price discrimination”. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of previous BBP studies.

Table 2 shows the relationship between the optimal product pricing for firms in the first and second periods and

: in the DD case, the price provided by firms to new consumers decreases as

increases. However,

,

, and

do not change with

, and in the DD case, the price offered by firms to old consumers increases as

increases.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 present more intuitively the impact of

on the equilibrium price in different cases. It is easy to see from

Figure 3 that when differential pricing exists, regardless of whether the promised delivery time is uniformly provided or not, the price difference provided by firms to new consumers in both DD and DU cases is not significant, nor is the price difference provided to old consumers. Moreover, unlike the monotonically decreasing change in first-period prices, when firms employ both BBP and BBT, the price offered by firms to old consumers increases slowly with

. However, the opposite is true for the price offered to new consumers. The price provided to new consumers becomes increasingly lower, and the price provided to old consumers becomes increasingly higher, and this difference becomes more pronounced. This indicates that the adoption of BBT by firms exacerbates price differentials in BBP, and the nature that

and

do not change with

also reveals this conclusion. We explain that when firms adopt BBP and UT, the prices provided to new and old consumers do not change with

, and the addition of BBT causes these prices to change and leads to an increasing difference.

Proposition 2. The relationship of promised delivery times in each case:

.

Corollary 2. , , .

Proposition 2 reveals that regardless of whether BBP is adopted, for firms, adopting UT is a better choice; that is, . Moreover, through comparative analysis, it can be found that there is an interesting phenomenon in the promised delivery times provided by firms to new and old consumers in each case. First, when firms adopt both BBP and BBT, firms provide a longer promised delivery time to new consumers and a shorter promised delivery time to old consumers. That is, the equilibrium results of the model show that the committed delivery period of old consumers should be smaller than that of new consumers, i.e., . This conclusion is exactly the opposite of the analysis of Proposition 1 regarding the optimal price. In a dynamic competitive environment, firms implementing differentiation strategies should pursue a dynamic balance of intertemporal discrimination, that is, balancing the acquisition of new customers with the retention of old customers.

However, in reality, the individual needs of new and old consumers often have differentiation. New consumers lack brand loyalty and are more concerned about product prices. Long delivery times can be used as a hidden discount (e.g., sacrificing time in exchange for a first-order discount), which can lower the threshold for their initial purchase. At the same time, firms can attract new customers at a low cost by diluting the cost of delayed fulfillment. Old consumers have formed usage inertia or switching costs, and shortening their delivery times (such as express delivery for members) is essentially a service bundle lock-in, while the firm’s marginal logistics investment costs decrease with data accumulation (such as historical order optimization route planning). Therefore, considering consumers’ fairness perception, this strategy may avoid fairness issues arising from direct horizontal price comparisons between new and old groups, thereby achieving a balance in behavioral discrimination.

Second, firms offer longer promised delivery times to both new and existing consumers than they would in the case of uniform promised delivery times. This suggests that BBT allows firms to lengthen promised delivery times appropriately; that is, BBT keeps firms from unilaterally promising shorter and shorter promised delivery times to consumers. Finally,

Figure 4 shows more intuitively that the promised delivery time decreases as

increases, and as

increases, the difference in promised delivery times between new and old consumers becomes larger and larger, and the “discrimination” becomes more and more pronounced.

The results of Propositions 1 and 2 imply that firm managers should adopt different strategies for new and old consumers on both the pricing and promised delivery time dimensions when facing time-sensitive consumers. Firms should provide lower prices and longer promised delivery times to new consumers, and higher prices and shorter promised delivery times to old consumers. Next, the relationships between firm profits in each period under the three different scenarios are given, and the results are as follows.

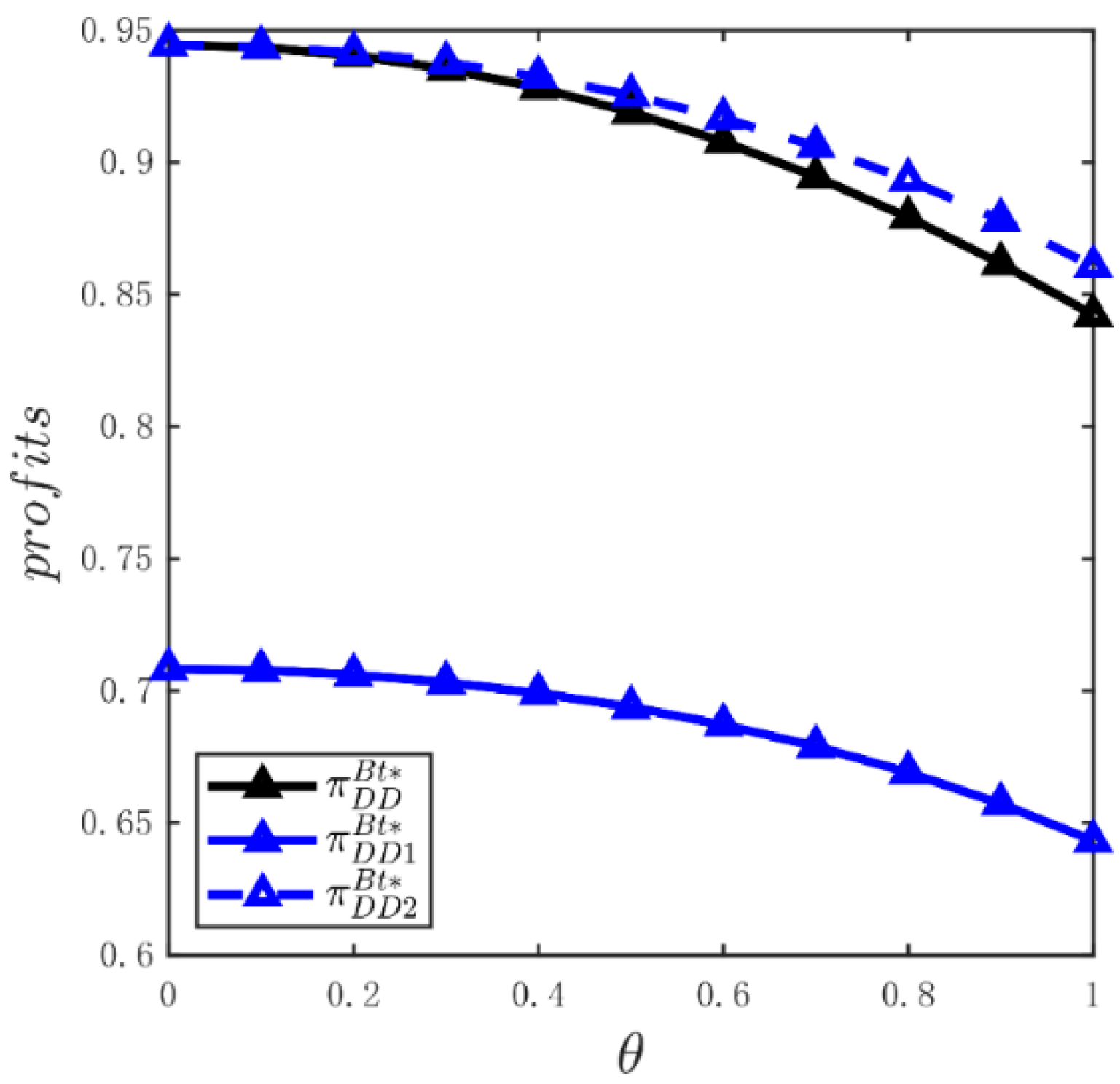

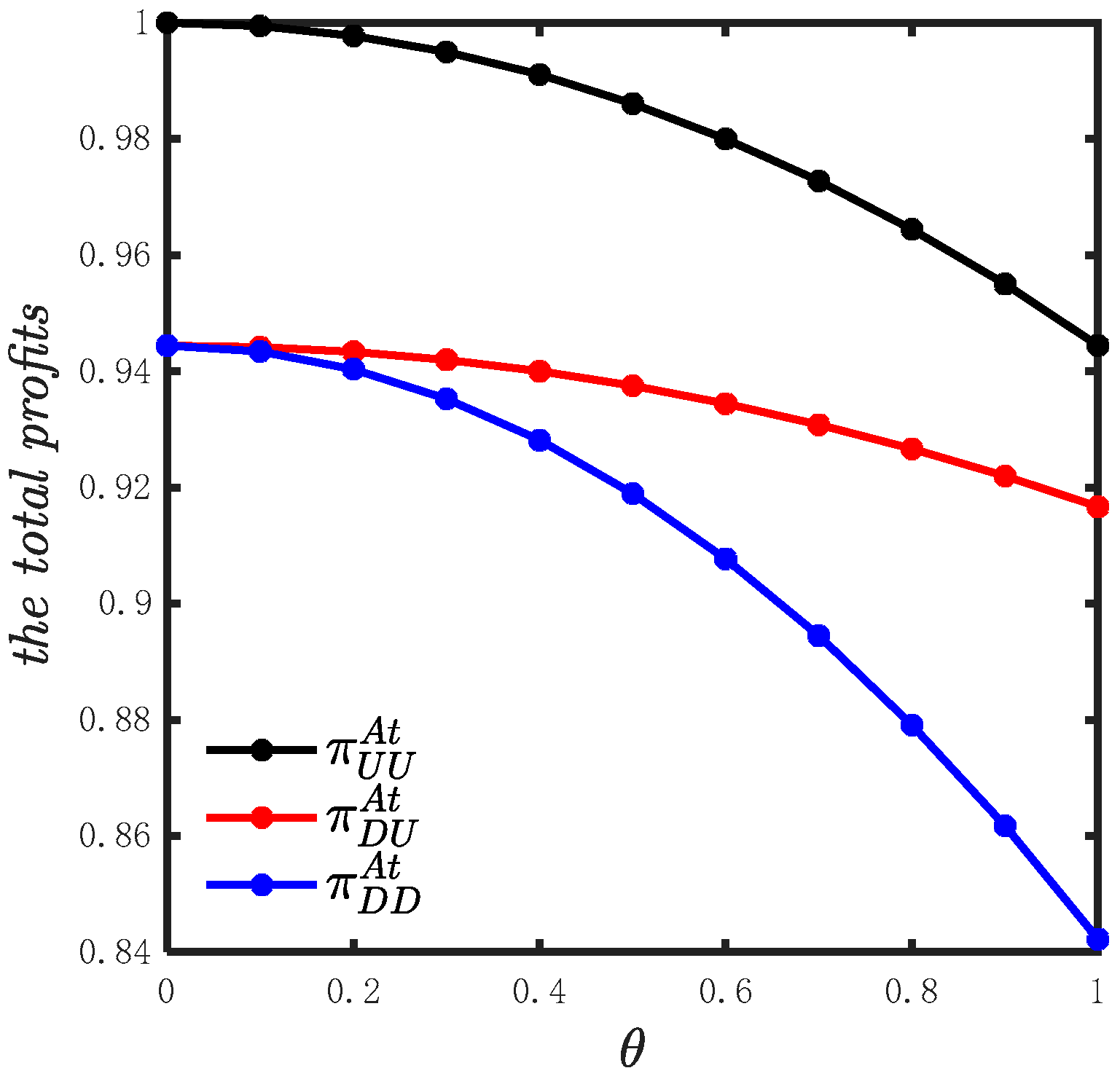

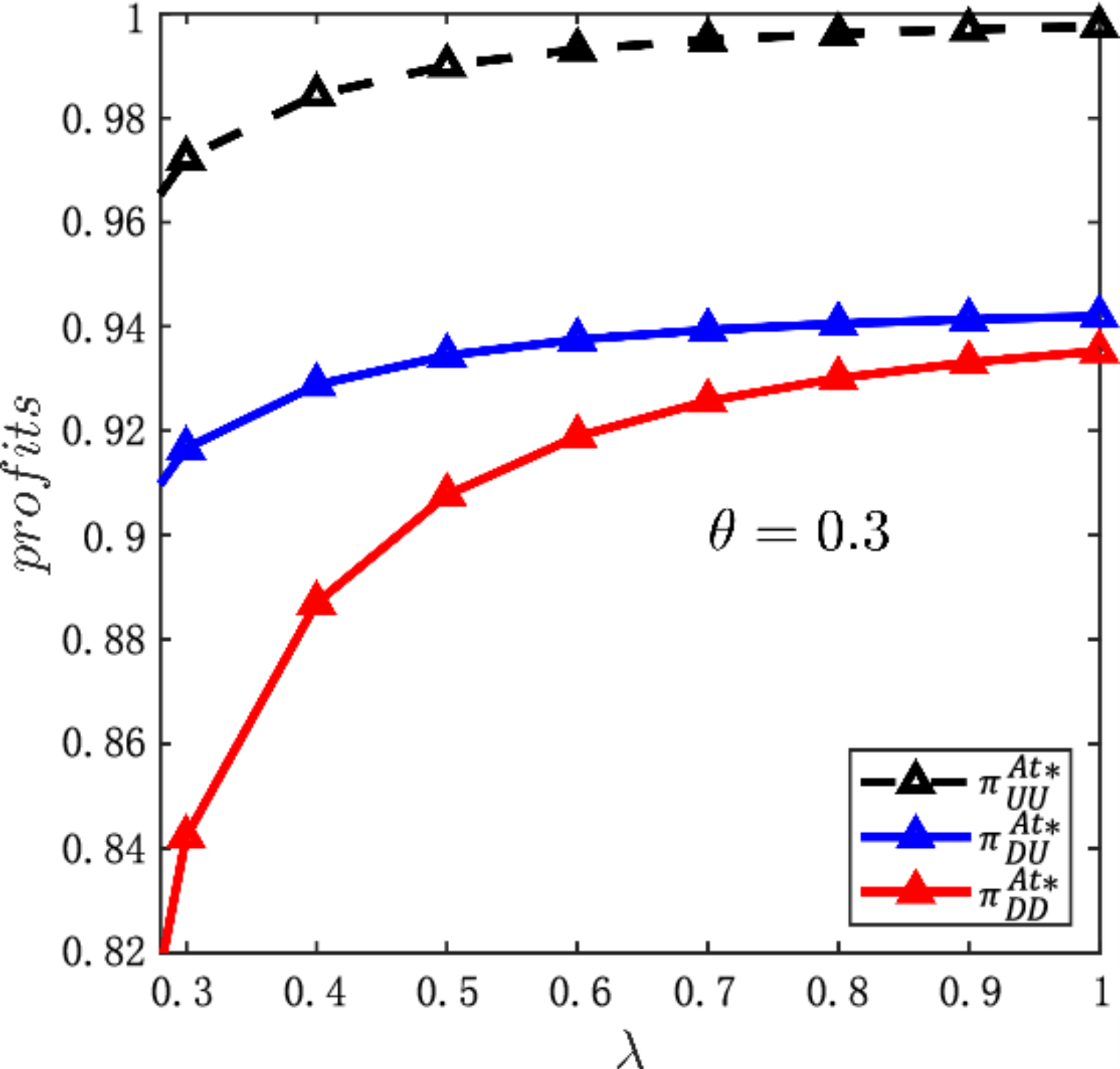

Proposition 3. The relationship between firm profits in each case:

,

,

;

Proposition 3 indicates that compared to case UU, the first-period sales profits of firms increase in both DU and DD; however, the second-period profits and total profits of firms decrease. This phenomenon suggests that the adoption of differentiation strategies by firms results in lower profits. In this paper, the reduction in profit mainly occurs in the second period, as the cost incurred by the firm in the two-period dynamic game model is generated by the decision made in the second period. In our model, joint decision-making on price and promised delivery time produces a synergy effect. Previous studies have found that BBP intensifies price competition in the first period, thereby reducing profits in the first period [

2,

3,

24]. However, our findings differ from previous studies in that BBP increases firms’ profits in the first period. As shown in

Figure 5, profits in the DU and DD scenarios are greater than those in the UU scenario. Our explanation is that previous studies have considered discrimination strategies based on a single price dimension, which causes firms to focus on acquiring new customers and engage in low-price competition. However, the addition of promised delivery times allows firms to balance the acquisition of new customers with the retention of old customers, achieving a dynamic discrimination equilibrium.

In order to further explore the unique relationship between BBP and BBT, we compare the profits of each period under DU and DD. We find that when a firm adopts BBP, the addition of BBT has different effects on the firm’s profits in each period. In the first period, compared with firms adopting BBP and UT, firms further adopting BBT will lead to a decrease in profits (i.e., ). In the second period, firms adopting BBP and BBT will slightly alleviate the loss of profits caused by firms adopting differential pricing and uniform promised delivery times (i.e., ). The decline in profits in the first period is understandable, as BBT’s entry further intensifies price competition in the first period, leading to profit losses. Interestingly, unlike the changes in the first period, profits increase in the second period. Considering market competition and consumer perceptions of fairness, this shows that discrimination strategies in different dimensions achieve synergy effects. As shown in Propositions 1 and 2, firms can use two-dimensional differentiation strategies to accurately design “price-time” combination bundles. In particular, in the second phase, designing a combination of “long delivery times and low-price discounts” for new customers not only attracts new customers, but also cushions logistics investment costs by extending delivery times. This may be the main reason for the profit growth in the second phase.

Finally, in terms of the difference in total profits earned by the firms in the three scenarios, the disparity between the total profits of the firms in the UU and DD scenarios increases as

increases. In the UU and DU scenarios, the difference in total firm profits decreases as

increases. This indicates that compared with the adoption of BBP and UT by firms, the further adoption of BBT by firms leads to a further reduction in profits, i.e.,

. In addition, the extent of profit reduction has a tendency to increase as

increases.

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 more intuitively show the impact of

on firm profits in different cases.

Lemma 4. The consumer surplus ,

, and

in the three cases are The overall social welfare

,, and

, are as follows Proposition 4. The relationship between consumer surplus in different cases: .

Corollary 4. , , .

According to the analysis of the profit results, compared with case UU, the total firm profits decrease in both BBP and UT, and BBP and BBT. Generally, when firms use information technology to analyze consumers’ purchase histories and make targeted differential treatments, it is disadvantageous to consumers, and consumer surplus is reduced. The results of this paper differ from subjective intuition, as Proposition 4 suggests that consumer surplus increases under DU and further increases under DD. It is easy to understand that a discriminatory strategy with a single price dimension in situation DU exacerbates competition between firms that engage in price competition, ultimately benefiting consumers. Our results corroborate this; that is, firms’ prices fall in the first period.

However, in case DD, the consumer surplus increases further, which is an exciting finding of the study. This suggests that the addition of BBT has a unique impact. Considering consumers’ perceived fairness in behavior [

23,

24], the differentiated promised delivery time strategy will compensate for the unfairness in pricing experienced by older consumers. Combining Proposition 2 with Proposition 3, in the second period, old consumers face higher prices and shorter promised delivery times, while new customers face lower prices and longer promised delivery times. In fact, the individual needs of both new and existing consumers often differ, and this differentiation strategy enables both groups to satisfy their needs and enjoy a better consumer experience. This explains the growth of consumer surplus; that is, the differentiation strategy constructs an equitable equilibrium in new customer acquisition and old customer retention. Thus, our results suggest that the joint strategy of BBP and BBT is a win–win mechanism for both new and existing consumers, and such results have not been seen before.

Corollary 4 and

Figure 8 reveal changes in consumer surplus, which decreases with increasing

in all three cases, and the differences in consumer surplus among the three cases become larger and larger as

increases.

Proposition 5. The relationship between social welfare in various cases: when , ; when , ; when , .

Corollary 5. , , .

In Proposition 5, starting from the perspective of the welfare of the entire society and considering consumers’ sensitivity to time, social welfare may increase or decrease in both DU and DD compared to case UU. Proposition 5 indicates that social welfare will increase as long as satisfies certain conditions. We argue that this is because consumers prefer the original firm that they like better, and few consumers casually switch firms without a goal in mind. As long as consumers are not less time-sensitive, differentiation strategies can increase social welfare by discouraging such switching by consumers. In particular, in the analysis of consumer surplus, we find that the joint strategy of BBP and BBT is a win–win mechanism for new and old customers. Firms should utilize different dimensions of differentiation strategies to achieve a fair equilibrium in new consumer acquisition and old consumer retention. The time-sensitive group pays a premium in exchange for delivery time compression, and its price loss is offset by high time utility.

However, the price-sensitive group waits in exchange for a lower price, reducing its price expenditure. This double differentiation rule reduces the sense of exploitation and increases the acceptance of dynamic pricing by all types of groups, so that social welfare will be superior to single uniform pricing.

Corollary 5 shows that social welfare decreases with increasing

in all three cases. In addition,

Figure 9 intuitively shows that as

increases, the social welfare in the uniform pricing and uniform promised delivery time case is increasingly different from that in the other two cases (DU and DD). To more intuitively show the changes in the equilibrium results of behavior-based pricing and promised delivery time strategies under various cases, we now set

,

. The equilibrium results obtained in this paper are shown in

Table 4.

Table 4 allows us to understand the impact of BBP and BBT strategies more intuitively. For example, in case DD, we can find that new consumers have lower prices and longer promised delivery times, yet the opposite is true for old consumers. Moreover, the numerical results clearly show that both consumer surplus and social welfare are improved under case DU and case DD. These findings are consistent with the description in our proposition and test the robustness of the results.