Abstract

In today’s competitive environment of online service industries, particularly e-commerce, meeting consumer expectations is essential for service providers to ensure service quality. However, service failures are unavoidable, leading to unfavorable consequences for businesses. Understanding the mechanisms for customer recovery after negative service experiences is crucial. Using cognitive–emotional personality systems theory and benign violation theory, this study constructed a theoretical model. A total of 351 samples were collected through a situational simulation experiment for a linear regression analysis. A self-mocking response strategy positively influenced brand trust through perceived brand authenticity regarding the dimensions of credibility, integrity, and symbolism. Simultaneously, brand trust was identified as a key driver of post-recovery satisfaction. This study proposes a chain mediation model, which incorporates perceived authenticity and brand trust, to fully comprehend the mechanisms underlying consumers’ satisfaction after service recovery. Our findings provide empirical evidence for the effects of self-mockery on post-recovery satisfaction, as well as suggestions for marketers seeking efficient means to meet consumers’ emotional and cognitive demands during service recovery situations.

1. Introduction

In the current competitive environment of online service industries, particularly e-commerce, consumers increasingly demand high-quality service experiences and evaluate service performance more critically [1,2]. The advent of online markets has made consumers more informed and raised their expectations regarding products and services [3]. Nevertheless, service failures are inevitable, often leading to consumer dissatisfaction, negative word-of-mouth communication, and even brand boycotts [4,5], and to mitigate these adverse outcomes, effective service recovery strategies are essential [1].

With the rise of social media, consumer responses to service recovery efforts are shaped not only by rational evaluations but also by emotional and psychological interpretations [6,7,8,9]. Psychological marketing has thus gained traction, emphasizing the importance of emotional and cognitive mechanisms in influencing consumer behavior [10]. According to the cognitive–affective system theory [11], individuals’ reactions to external stimuli are shaped by interconnected cognitive and affective units, making it essential to consider both when designing recovery strategies. In this context, perceived authenticity and brand trust serve as key psychological constructs that mediate consumers’ responses to brand actions.

While traditional service recovery efforts often rely on rational, apologetic strategies [12], these approaches may fall short in highly emotional and socially visible settings like social media [13]. An emerging alternative is the use of humor-based communication, particularly self-mocking responses. Rooted in benign violation theory, self-mockery allows firms to humorously acknowledge service flaws, thereby diffusing tension and reshaping consumer perceptions [14]. Notably, brands such as Volkswagen and Starbucks have successfully leveraged self-mockery to reframe service issues, enhance emotional connection, and rebuild trust.

Although anecdotal evidence and conceptual discussions suggest the potential of self-mocking strategies in service recovery, empirical research on this topic remains limited. Specifically, few studies have examined the underlying cognitive–affective mechanisms through which self-mocking influences post-recovery outcomes. To address this gap, the present study investigates how self-mocking communication influences consumer satisfaction through perceived brand authenticity and brand trust, drawing on cognitive–affective system theory.

Specifically, this study explores three questions: (1) How does perceived brand authenticity mediate the relationship between self-mocking and brand trust? (2) How does brand trust mediate the relationship between self-mocking and post-recovery satisfaction? (3) Do authenticity and trust jointly play a chain-mediating role in this process? This research contributes to the growing body of literature on self-mocking strategies in service recovery by offering empirical evidence through a cognitive–affective lens. The remainder of this manuscript proceeds as follows: we review the theoretical background and develop hypotheses, describe the experimental design and methodology, present the results, and conclude with a discussion of theoretical and practical implications.

2. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Service Failure and Psychological Recovery

Given the prevalence and severe consequences of service failures, identifying cost-efficient and easy-to-implement methods for restoring consumer satisfaction is crucial [1]. Previous studies on service recovery have categorized recovery into two types: the first is psychological recovery, which involves efforts to provide social or psychological amends to consumers [4], and the second is tangible recovery, which involves material compensation [3]. Regardless of a service provider’s overall response strategy, engaging in some form of initial psychological recovery is necessary, involving verbally acknowledging the faults and providing consumers with social and psychological compensation [15]. Psychological recovery thus constitutes an essential and primary component of a company’s recovery efforts.

In the event of service failure, consumers in a shared relationship tend to associate their interests with the company, displaying a stronger willingness to maintain the relationship and a protective inclination toward the company [16]. Consequently, their perception of conflict is low. When companies actively acknowledge their shortcomings and faults, their brand trust is enhanced, which helps restore consumer satisfaction [17]. The self-mocking response strategy is an art form rooted in self-critical commentary delivered humorously, whereby companies display vulnerability to consumers [18]. Through self-mocking to “show weakness,” companies can strengthen consumers’ protective motivation and enhance their “benign perception.” In situations of service failure, the root cause of consumer complaints is unmet expectations and compensation disparities, which escalate conflict perception. The main intents of such complaints are psychological balance or compensatory benefits [19]. In this context, a company’s self-mocking behavior signals acknowledgment of its shortcomings, serving as a psychological compensation for consumers. Furthermore, humorous expressions serve as another form of emotional compensation by eliciting laughter [20]. We thus propose that utilizing the self-mocking strategy might be effective for a company in placating aggrieved consumers in the event of service failure.

2.2. Self-Mocking and Perceived Brand Authenticity

Amidst a rapidly evolving marketplace, characterized by sharp behavioral changes and frequent social media usage by consumers, brand authenticity has transitioned from being a crucial attribute to an essential asset for brands [21]. The concept of authenticity originates from sociology but has gained extensive application in other research fields such as leisure and tourism. Although this concept has been widely acknowledged in scholarly work, varying contexts and research purposes have hindered its understanding, and the concept remains to be unified [22].

Scholars have identified three forms of brand authenticity: objective, constructive, and existential [23]. As per the philosophical theory of objectivism, brand authenticity encompasses objective attributes of brand knowledge, which are presented through practice and substantiated by facts during a brand’s development. This perspective emphasizes the objectivity of authenticity, asserting that this attribute is inherent and characteristic of objective entities and that it exists from the inception of these entities [24].

Constructivists, on the other hand, view brand authenticity as a product of consumers’ subjective construction of a brand, rather than an objective phenomenon [23]. This perspective assumes brand authenticity as a perception shaped by social culture, norms, beliefs, and values. In other words, authenticity is not solely inherent to the brand but also determined by consumers’ perception of the brand [24]. Brand authenticity is therefore contingent on consumers’ subjective evaluations, rather than the brand’s objective attributes. Existentialism offers yet another perspective, viewing brand authenticity as an attribute that resonates and aligns between the brand’s self and the consumer’s real self, due self, and ideal self during the consumption experience. This form of brand authenticity supports the expression of consumers’ potential values [23].

In response to service failure, regardless of the strategy employed by the merchant, perceiving the merchant’s seriousness and sincerity is imperative for consumers to evaluate the effectiveness of its crisis response strategy [25]. Brand sincerity is associated with attributes such as honesty, consideration, sincerity, and care [26]. In the self-mocking crisis response strategy, a company humorously acknowledges its shortcomings, thereby using humor to navigate the challenge [27]. The essence of this strategy lies in its ability to signal the company’s “weakness,” thus demonstrating its humility and sincerity [18]. This approach allows consumers to perceive the brand’s stance and actively safeguards their interests [28]. This aligns with the “credibility” dimension of perceived authenticity, as self-mocking reflects transparency, honesty, and the brand’s ability to acknowledge its faults, reinforcing the perception of the brand’s sincerity and trustworthiness.

Morhart et al. (2015) asserted that the “credibility” of perceived authenticity reflects a brand’s transparency and honesty toward consumers, as well as its willingness and ability to fulfill its claims [23]. Based on this understanding, this study considers that, in the context of service failure, the characteristics of the self-mocking response strategy embody the “credibility” dimension of perceived authenticity and represent the objectivists’ view of authenticity. Self-mocking thus enhances the credibility of the brand by making it transparent and accountable to consumers, which strengthens the trust consumers place in the brand.

Various studies have emphasized the importance of a brand’s proactive acknowledgment of its shortcomings in significantly boosting consumers’ perception of corporate morality and positively influencing their attitude toward the brand [18,29]. This directly corresponds to the “integrity” dimension of perceived authenticity, as self-mocking communicates the brand’s moral values and consistency in behavior. The self-mocking response strategy involves employing humor to convey apologies to consumers. This approach helps in bridging the gap with consumers and exhibits anthropomorphic characteristics that facilitate the consumer–brand association [25]. Brands associated with human characteristics provide vivid self-referential cues that help consumers test, refine, and construct their self-identity. Through this anthropomorphic humor, self-mocking allows consumers to perceive the brand as honest and consistent, which enhances the perception of the brand’s integrity. The “symbolism” of perceived authenticity, in the context of self-mocking, is defined as the potential of these humorous responses to facilitate consumers’ construction of their unique self-identity. Brands that adopt self-mocking strategies can be seen as expressing symbolic meanings that allow consumers to align the brand with their own values and self-concept [23]. Self-mocking, through its humorous and humanized nature, helps consumers associate the brand with a deeper personal connection, facilitating the brand’s symbolic role in the consumer’s self-concept.

In summary, this study establishes credibility, integrity, and symbolism as the three dimensions of perceived authenticity. The literature suggests that a brand’s perceived authenticity enhances consumers’ trust in the brand [6]. This study further posits that the self-mocking crisis response strategy influences these three dimensions of perceived authenticity, thereby enhancing the overall brand trust and its symbolic connection with consumers. In other words, when consumers perceive a brand as authentic, they consider it a friend in their lives, gradually increasing their trust toward the brand.

Additionally, according to cognitive–affective system theory (CAST), self-mocking response content can activate consumers’ cognitive–affective units (CAUs), thereby eliciting a series of psychological and behavioral responses. As an external stimulus, self-deprecating response content reflects cognitive characteristics through perceived authenticity and affective characteristics through brand trust. In cognitive processing, perceived brand authenticity refers to consumers’ judgment and evaluation of whether a brand’s actions and expressions are genuine and credible. This process typically involves rational cognitive activities such as information gathering, analysis, and comparison, which are closely tied to the cognitive system functions (e.g., logical reasoning and critical thinking) [11]. Perceived brand authenticity is therefore primarily rooted in cognitive system operations and represents a cognitive response. In affective processing, brand trust refers to consumers’ emotional expectation and confidence in a brand’s reliability and integrity, such as the belief that the brand is sincere, dependable, and consistent in its behavior [30]. Prior studies have shown that individuals often rely on intuitive, affective, and rapid processing when forming trust in brands [31]. Brand trust thus depends more on affective system functions and reflects an affective response. As such, consumers stimulated by self-mocking response content may generate perceived brand authenticity (cognition) and brand trust (affection). The following hypotheses are therefore proposed:

H1a:

Self-mocking is positively related to the credibility of perceived brand authenticity.

H1b:

Self-mocking is positively related to the integrity of perceived brand authenticity.

H1c:

Self-mocking is positively related to the symbolism of perceived brand authenticity.

H2a:

Self-mocking positively affects brand trust by enhancing the credibility dimension of perceived brand authenticity.

H2b:

Self-mocking positively affects brand trust by enhancing the integrity dimension of perceived brand authenticity.

H2c:

Self-mocking positively affects brand trust by enhancing the symbolism dimension of perceived brand authenticity.

2.3. Perceived Brand Authenticity, Brand Trust, and Post-Recovery Satisfaction

Studies have established that perceived authenticity determines both brand attitude and brand loyalty [32]. Additionally, authenticity and fulfilling the need for authenticity directly and favorably affect consumer satisfaction [33], trust [34], and word-of-mouth communication [35]. Furthermore, they significantly influence the quality of the consumer–brand relationship [36], perceived value [37], emotional attachment [38], and affinity [39]. Studies have also underscored the positive impact of a robust bond and the quality of consumer–brand relationships on consumers’ propensity to forgive brand mistakes. This phenomenon is attributed to a strong emotional connection fostered by brand authenticity [40]. Post-recovery satisfaction pertains to the customers’ overall perception of service remedies implemented by an organization following an incidence of service failure [41]. It involves comparing customers’ expectations during the service recovery process with their actual perception of the recovery efforts to gauge whether those expectations have been met [42]. Andreassen (2000) opined that customers’ satisfaction with service recovery reflects their psychological adjustments in response to the recovery efforts following service failure [43]. When confronted with service failure, if a brand meets the customers’ expectations and engenders a genuine perception of resolution, the brand is considered to hold inherent value in the customers’ psychological assessment [44].

Previous studies have reported perceived authenticity as a moderator between service recovery and customer recovery satisfaction [45,46]. From the credibility dimension of perceived brand authenticity, consumers tend to trust brands that are willing to admit mistakes and communicate with honesty. This “credible sense of authenticity” serves as a critical foundation for rebuilding consumer trust. Integrity emphasizes whether the brand adheres to sound values and ethical conduct [47]. During the service recovery process, a brand’s willingness to take responsibility—without deflection or concealment—is key to rebuilding consumer trust. Integrity not only strengthens the psychological perception of brand reliability but also signals the brand’s moral stance in times of crisis, aligning with consumers’ expectations of ethical brands. This value-based trust fosters more favorable evaluations of recovery efforts, thereby improving post-recovery satisfaction. Regarding the symbolism dimension, consumers’ perceptions of authenticity are not solely derived from tangible brand behavior but also from the cultural meanings and values the brand conveys. If service recovery is delivered in a manner that reflects the brand’s personality, it can evoke emotional resonance and foster affective attachment [48]. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H3a:

The credibility dimension of perceived brand authenticity positively influences post-recovery satisfaction through brand trust.

H3b:

The integrity dimension of perceived brand authenticity positively influences post-recovery satisfaction through brand trust.

H3c:

The symbolism dimension of perceived brand authenticity positively influences post-recovery satisfaction through brand trust.

2.4. Chain-Mediating Effect of Self-Mocking Strategies on Post-Recovery Satisfaction

Adopting a self-mocking strategy, wherein individuals humorously admit their shortcomings, evokes positive emotions and enhances brand attitude [25]. According to the cognitive–affective system theory of personality, self-mocking strategies potentially trigger a positive cognitive and emotional response in consumers, thereby enhancing their post-recovery satisfaction. Specifically, a self-mocking strategy increases post-recovery satisfaction by fostering the perceived brand authenticity and brand trust, which are crucial determinants of post-recovery satisfaction [45]. Specifically, self-mocking conveys openness and reduces defensiveness, which enhances perceptions of credibility, thereby fostering trust. It also signals accountability in a non-defensive, humanized manner, reinforcing the brand’s ethical stance and encouraging consumers to view the brand as acting in good faith. Additionally, by incorporating humor that resonates culturally and emotionally, self-mocking renders the brand more relatable and human-like, reinforcing symbolic authenticity and deepening emotional bonds that further build trust. Accordingly, we hypothesize that self-mocking strategies positively influence post-recovery satisfaction in the case of service failure through their effects on the perceived brand authenticity and brand trust.

H4a:

The credibility dimension of perceived brand authenticity and brand trust plays a chain-mediating role in the positive effect of self-mocking on post-recovery satisfaction.

H4b:

The integrity dimension of perceived brand authenticity and brand trust plays a chain-mediating role in the positive effect of self-mocking on post-recovery satisfaction.

H4c:

The symbolism dimension of perceived brand authenticity and brand trust plays a chain-mediating role in the positive effect of self-mocking on post-recovery satisfaction.

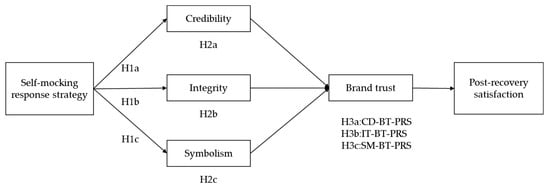

To summarize, we construct a theoretical model, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

In this study, a scenario-based survey was designed to elicit psychological and behavioral responses among respondents. First, the participants were instructed to read a brief scenario concerning their interaction with a fictional business entity, which was devised to minimize extraneous influences. The following scenario was presented to the participants: “You recently sought to purchase a set of sports equipment online for urgent use. After conducting thorough comparisons, you opted for a well-regarded brand. However, upon placing the order, you experienced delays in delivery by the seller, significantly surpassing the platform’s estimated waiting time of 3 days. This delay hindered your immediate usage of the equipment. Despite the equipment’s perceived quality, you harbored dissatisfaction and subsequently lodged a formal complaint.”

In response to the complaint, the merchant issued the following reply:

“Begging for your forgiveness, sob! We always thought we were the “Flash” of the delivery world, but this time we turned into the “Turtle,” making you wait so patiently. It looks like we need to give our delivery team a pair of wings! In the future, we will keep a close eye on it, and if there are any more slip-ups, please feel free to urge us on, don’t hold back. Thank you for your support. We will definitely speed up the delivery process, ensuring that your beloved items are delivered to you as soon as possible.”

This humorous self-mocking response was adapted from the style of expression examined in Xu et al. (2017), a Chinese-language study that analyzed the use of humor in corporate apologies. The target population of this study was general Chinese consumers with experience in online shopping [49]. To ensure the relevance of responses, a screening question was used at the beginning of the survey to confirm participants’ prior online shopping experience. Only those who responded affirmatively were allowed to proceed.

The questionnaire was distributed online via WeChat Groups and WeChat Moments from 15 November 2023 to 13 December 2023. These platforms were selected for their high user penetration, strong relevance to the research context, and efficient outreach capability. Specifically, WeChat is the most widely used social and communication app in China, with over one billion active users—many of whom are frequent e-commerce users. Given the study’s focus on service recovery in online shopping contexts, WeChat users closely match the target demographic of digital-savvy Chinese consumers familiar with delivery services and complaint processes. Distributing the survey via WeChat enabled rapid, voluntary, and demographically diverse participation, thereby enhancing ecological validity by simulating a realistic interaction environment. No monetary incentives were offered; participation was solicited by emphasizing the academic purpose of the study and assuring confidentiality. A total of more than 390 responses were collected. After data cleaning and screening for completeness and consistency, 351 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis. The final sample comprised 209 female participants and 142 male participants.

Most respondents belonged to the age bracket of 18–40 years, aligning with the observation that individuals belonging to the post-1980s and post-1990s generations more frequently opt for online shopping, accounting for 93% of the total responses. Regarding educational background, 24.5% of respondents had a high school education or below, 70.9% had a university degree, and 4.6% held a master’s degree or above. Regarding occupation, 26.2% were employed in public services, 29.9% in production-related positions, and 31.3% in business-related roles, while 12.5% were unemployed, including students, retirees, and homemakers. For monthly income, 11.4% of participants reported earning less than 3000 Chinese Yuan Renminbi (RMB), 21.7% earned between RMB 3000 and 5000, 27.6% between RMB 5000 and 7000, and 25.6% between RMB 7000 and 10,000, while 13.7% reported monthly earnings above RMB 10,000. Overall, the sample demonstrated relatively high educational attainment, stable economic backgrounds, and frequent and proficient engagement with online shopping environments, indicating strong digital competence.

3.2. Scales

Self-mocking was measured using the following four semantic differentials following Bieg et al. (2017): “The brand makes fun of itself with humor”; “The brand tells embarrassing stories about itself with a sense of humor”; “The brand makes fun of itself when it makes mistakes with humor”; and “The brand laughs about itself in a humorous way” [50]. We used the original items without modification. The three dimensions of perceived authenticity, namely credibility, integrity, and symbolism, were selected by referring to the study by Morhart et al. (2015) [23]. Specifically, credibility refers to the extent to which the brand is perceived as honest, trustworthy, and consistent (e.g., “a brand that will not betray you”; “a brand that accomplishes its value promise”; “an honest brand”). Integrity reflects the brand’s alignment with moral principles and concern for consumers (e.g., “a brand that gives back to its consumers”; “a brand with moral principles”; “a brand true to a set of moral values”; “a brand that cares about its consumers”). Symbolism captures the extent to which the brand helps consumers connect with their identity and values (e.g., “a brand that adds meaning to people’s lives”; “a brand that reflects important values people care about”; “a brand that connects people with their real selves”; “a brand that connects people with what is really important”). All items were adopted directly from the original study. The participants’ brand trust was measured using three items [50], namely “I trust brand X”; “I feel comfortable depending on brand X”; and “I rely on brand X to deliver on its brand promise in the future.” Finally, post-recovery satisfaction was measured using three items [51]: “I am satisfied with the way the staff dealt with and resolved my problem”; “In general, the staff provided a satisfactory solution to this particular problem”; and “I am happy with the way the staff solved my problem.”

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability Assessments

We established the reliability and validity of the measures using SPSS 24. In this study, construct validity was assessed using an exploratory factor analysis [52]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.909, exceeding the threshold of 0.6 recommended by Kaiser (1974) [53]. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the correlations among items were sufficient for factor analysis. The cumulative variance explained was 75.68%, surpassing the minimum 50% standard suggested by Hair et al. (2010) [54]. To assess internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated. The values for self-mocking, credibility, integrity, symbolism, brand trust, and post-recovery satisfaction were 0.896, 0.848, 0.880, 0.878, 0.849, and 0.843, respectively—all exceeding the 0.7 threshold proposed by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) [55]. These results demonstrate strong reliability and support the use of the constructs in further analyses.

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

This study employed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 24 to validate the effectiveness of the measurement model. As shown in Table 1, the model demonstrated a good fit, with the following indices: χ2/df = 1.036 (p < 0.05, df = 174); Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.998; Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.998; Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.998; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.010; and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.026. Additionally, all standardized factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha values, average variance extracted (AVE) values, and composite reliability (CR) values for the constructs exceeded the thresholds recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) [56].

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

Furthermore, we verify discriminant validity by comparing the AVE values of all constructs with the squares of their respective correlation coefficients. As illustrated in Table 2, the AVE values for all constructs on the diagonal were greater than the squares of the correlation coefficients located below them, indicating that discriminant validity is not a concern [56].

Table 2.

Correlation analysis results.

4.3. Mediation Analysis

4.3.1. The Mediating Effect of Perceived Brand Authenticity and Brand Trust

All the statistical analyses, including correlation tests and mediation analyses, were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 to test the proposed hypotheses. To verify Hypothesis 1, credibility, integrity, and symbolism were considered dependent variables; the results are presented in Table 3. As anticipated, perceived self-mocking positively correlated with the perceived brand authenticity in terms of the dimension’s credibility (β = 0.416, p < 0.001), integrity (β = 0.414, p < 0.001), and symbolism (β = 0.409, p < 0.001), supporting H1a, H1b, and H1c.

Table 3.

Hypothesis 1 testing.

To verify the mediating role of perceived brand authenticity, a mediation analysis was performed using PROCESS Model 4, which is particularly useful in studying indirect effects in mediation models. The coefficient for the indirect effect of perceived self-mocking on the brand trust relationship via credibility was 0.117, with a bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) of [0.071, 0.170] at the 95% level. In addition, perceived self-mocking mediated the effect of integrity on the brand trust relationship, with the indirect effect coefficient of 0.119 and a bias-corrected 95% CI of [0.070, 0.173]. Similarly, perceived self-mocking mediated the effect of symbolism on the brand trust relationship, with the indirect effect coefficient of 0.107 and a bias-corrected 95% CI of [0.059, 0.163]. These results indicated that the mediating effects were all significant, thereby supporting H2a, H2b, and H2c.

To test the mediating relationships using PROCESS Model 4, this study considered credibility, integrity, and symbolism as independent variables, and the post-recovery satisfaction as a dependent variable. As shown in Table 4, brand trust mediated the influence of credibility on customers’ post-recovery satisfaction, with the indirect effect value of 0.123 and a 95% CI of [0.078, 0.176], which does not contain 0, indicating that this mediating relationship is significant. The coefficient for the indirect effect of integrity on the post-recovery satisfaction relationship via brand trust was 0.127, with a bias-corrected 95% CI of [0.081, 0.179]. With symbolism as the independent variable, the coefficient for the indirect effect of symbolism on the post-recovery satisfaction relationship via brand trust was 0.120, with a bias-corrected 95% CI of [0.076, 0.170]. Collectively, these results indicated that brand trust mediates the relationship between perceived brand authenticity and post-recovery satisfaction, supporting H3a, H3b, and H3c.

Table 4.

Mediation analysis of the effects of self-mocking brand response on brand trust and post-recovery satisfaction via perceived credibility, integrity, and symbolism.

4.3.2. The Chain Mediation Effects of Perceived Brand Authenticity and Brand Trust

Using Model 6 in the SPSS Macro-Process program, the mediating effects of the perceived brand authenticity and brand trust on the perceived self-mocking and post-recovery satisfaction were analyzed. The corresponding regression analysis results are presented in Table 5. With credibility and brand trust as the mediating variables, the total indirect effect value between the perceived self-mocking and post-recovery satisfaction was 0.181, corresponding to a CI that did not contain 0, indicating that the total indirect effect was significant. In Indirect Effect 3, the indirect effect value for perceived self-mocking–credibility–brand trust–post-recovery satisfaction was 0.026, with a bias-corrected 95% CI of [0.011, 0.044], indicating that Indirect Effect 3 was significant.

Table 5.

Mediation analysis of perceived brand authenticity and brand trust.

When integrity and brand trust were considered the mediating variables, the value for the total indirect effect of perceived self-mocking on post-recovery satisfaction was 0.189, corresponding to a CI that did not contain 0, indicating that the total indirect effect was significant. In Indirect Effect 3, the value for the indirect effect of perceived self-mocking–integrity–brand trust–post-recovery satisfaction was 0.027, with a bias-corrected 95% CI of [0.012, 0.046]; this indicated that Indirect Effect 3 was significant. With symbolism and brand trust as the mediating variables, the value for the total indirect effect of the perceived self-mocking on post-recovery satisfaction was 0.189, corresponding to a CI that did not contain 0, which indicated that the total indirect effect was significant. In Indirect Effect 3, the indirect effect value for perceived self-mocking–symbolism–brand trust–post-recovery satisfaction was 0.024, with a bias-corrected 95% CI of [0.011, 0.042], indicating that Indirect Effect 3 was significant. These results indicated that self-mocking affects brand trust and the post-recovery satisfaction of consumers through the perceived brand authenticity in terms of credibility, integrity, and symbolism. H4a, H4b, and H4c are therefore supported.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This study tested a comprehensive set of hypotheses H1a–H4c to explore the underlying mechanisms of how self-mocking brand responses affect post-recovery satisfaction. The empirical results provide full support for all proposed hypotheses. Specifically, self-mocking responses were found to significantly enhance all three dimensions of perceived brand authenticity—credibility, integrity, and symbolism, which, in turn, positively influenced brand trust. Moreover, each dimension of perceived brand authenticity and brand trust played a significant mediating and chain-mediating role in the relationship between self-mocking and post-recovery satisfaction. These findings validate the proposed theoretical model and confirm the dual cognitive–affective pathways outlined by the cognitive–affective system theory (CAST).

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study presents the following important theoretical contributions. First, it examines the role of brands’ self-mocking responses in service failure management. Service recovery has been a topic of interest in the field of service marketing, and in case of service failures, firms employ different response strategies, such as admitting mistakes, apologizing, denying, and appreciating [1,57,58]. However, only a few studies to date have examined the effect of brand self-mocking, an emerging response style, on consumers’ post-recovery satisfaction. A self-mocking response effectively captures the psychology of modern consumers, thereby enhancing a brand’s perceived authenticity and fostering consumer trust in the brand. Consequently, it is more likely to gain recognition among consumers. This study’s second contribution lies in providing a highly comprehensive psychological perspective. Individuals’ thoughts and emotions are often intertwined, influencing their behavior and decision-making. By acknowledging both cognitive and affective dimensions, this study contributes to refining or developing theories that clearly explain the intricacies of the psychological phenomena under investigation. The third theoretical contribution of this study is the finding that self-mocking exerts a mediating effect on brand trust via brand authenticity. Pertinent studies in the literature on brand authenticity have established brand trust as an outcome [34]; however, the link between brand authenticity and brand trust in the context of self-mocking remains underexplored. This study addresses this gap by providing a more profound scholarly comprehension of the mechanisms and impacts of self-mocking response strategies. Grounded in cognitive–affective personality systems theory, this study constructed an overall logic between all research variables, comprehensively revealing the mechanism through which self-mocking influences the post-recovery satisfaction. Finally, this study extends the application scope of the cognitive–affective system theory of personality to the field of marketing.

5.2. Marketing Implications

Apart from theoretical implications, our research offers actionable marketing implications for managers, particularly in the context of online service environments where service failures can quickly escalate due to real-time public exposure. In the digital era, brands no longer maintain one-way communication; instead, they engage in dynamic two-way interactions with consumers via social media, e-commerce platforms, and online communities. This intensifies both the risks and opportunities of service recovery. On the one hand, these changes pose challenges for brands’ response strategies after service failure. On the other hand, they facilitate the evolution and development of new response strategies by providing more opportunities.

This study verifies the feasibility of self-mocking response strategies in restoring consumer satisfaction. Based on the findings, this study proposes that, after grasping the characteristics of consumer psychology and communication in the Internet environment, enterprises should adopt the self-mocking strategy in response to service failure in a timely manner to restore consumers’ post-recovery satisfaction. To implement this, firms can establish rapid-response social media protocols, develop pre-approved humorous language banks, and empower front-line staff to flexibly adopt playful tones that acknowledge responsibility while easing tension.

Second, enhancing brand authenticity should remain a strategic priority. Staying true to the brand’s values, empowering employees, and ensuring honesty and transparency can boost consumers’ perceived brand authenticity, eventually enhancing their willingness to forgive a brand in the case of wrongdoing, and improving transparency through honest dialogs that build trust. Focusing on the consumers’ emotional needs by delivering personalized and empathetic responses after service failure. Finally, fostering an emotional connection with consumers during this process can be conducive to rebuilding trust, enhancing brand loyalty, and turning a negative experience into a positive one.

This study examined how self-mocking response strategies influence consumers’ post-recovery satisfaction, drawing on cognitive–affective system theory (CAST). The results provide empirical support for the self-mocking response strategy positively influences consumers’ perceived brand authenticity. This implies that the higher the consumers’ perception of self-mocking, the higher their perceived brand authenticity. The use of self-mocking response strategies displays sincerity and humility and involves anthropomorphic expression, contributing to enhancing consumers’ perceived brand authenticity. These findings are in line with previous research indicating that humor and anthropomorphic expressions help humanize brands and enhance perceived authenticity [59]. This supports the view that self-mocking can serve as an effective non-traditional strategy for shaping brand perception in a crowded digital landscape.

In addition, perceived brand authenticity significantly enhances brand trust. This finding echoes prior studies demonstrating that authenticity is a foundational element in building consumer trust [30,31]. Trust formation is an affective process grounded in consumers’ emotional judgment of brand integrity, dependability, and goodwill. This highlights the importance of perceived authenticity not only as a brand value but also as a driver of deeper relational outcomes.

Third, the results show that brand trust positively influences consumers’ post-recovery satisfaction, a finding consistent with the existing literature [36] and that emphasizes the buffering role of trust in crisis and service recovery situations. Consumers are more likely to accept service failures and feel satisfied with recovery efforts when they have confidence in the brand’s intentions and reliability.

Finally, perceived brand authenticity and brand trust play significant mediating and chain-mediating roles in the relationship between self-mocking responses and post-recovery satisfaction. This confirms that consumers’ reactions to humorous recovery communication are processed through dual cognitive (authenticity) and affective (trust) pathways, as predicted by CAST. This dual-pathway mechanism advances our understanding of how brands can influence consumer behavior during challenging moments by balancing rational evaluation with emotional resonance.

5.3. Limitations

Acknowledging the limitations of this study is also crucial. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data and the use of a fictional business entity in the situational simulation, this study faces challenges in deriving clear causal relationships among variables and fully capturing the experience-based development of brand trust and perceived authenticity. Future research could adopt longitudinal tracking designs to explore how consumers’ cognition, emotions, and behaviors evolve over time following exposure to self-mocking response strategies, and use real brands to enhance ecological validity, and critically, the study lacks a control group condition (e.g., a brand response using a neutral or non-humorous tone), which limits the ability to clearly attribute observed effects to the self-mocking strategy itself. Future experimental research should incorporate between-group designs with appropriate control conditions to more rigorously establish causality and isolate the unique effects of self-mocking versus other recovery strategies.

Furthermore, owing to resource constraints, this study included only Chinese consumers, which precludes the exploration of whether consumers’ brand perceptions vary with differences in social and cultural backgrounds. As identified by Hofstede (1983), Western culture emphasizes individualism, and its social relation interpretations differ from those of Asian cultures that value collectivism and social harmony [60]. Understanding the role of cultural differences in consumers’ willingness to trust brands employing self-mocking response strategies is therefore crucial. Future research should expand the sample size and range to compare differences in the perception of consumers from diverse cultural contexts. Moreover, this study examines the influence mechanism of self-mocking response strategies on post-recovery satisfaction from the psychological perspective and verifies the mediating role of brand perceived authenticity and brand trust. However, the impact mechanism involves multi-level, multi-factor dynamics. Future studies could thus explore other mediating variables at levels not covered in this study, such as psychological safety [61].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., J.H. and Q.P.; methodology, Y.Z. and Q.P.; software, Y.Z. and Q.P.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; resources, Q.P.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z., and J.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and Q.P.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (25BNHZ035YB).

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to institutional guidelines and national laws and regulations, ethical approval was not required as there was no unethical conduct in this study. We only conducted a questionnaire, and as this study did not involve human clinical trials or animal experiments, no further approval from the ethics committee was required.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the “Declaration of Helsinki.” Respondents were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. All participation is voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- You, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Deng, X. When and why saying “thank you” is better than saying “sorry” in redressing service failures: The role of self-esteem. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xu, S.; Li, S.; Pang, Q. Research on Influence Mechanism of Consumer Satisfaction Evaluation Behavior Based on Grounded Theory in Social E-Commerce. Systems 2024, 12, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Seock, Y.-K. Effect of service recovery on customers’ perceived justice, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth intentions on online shopping websites. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, K.; Li, M.; Dong, B. Service quality: The impact of frequency, timing, proximity, and sequence of failures and delights. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Liang, Z.; Du, Y.; Huang, E.; Zou, Y. When Brands Push Us Away: How Brand Rejection Enhances In-Group Brand Preference. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 3123–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Diaz, R.; Cavazos-Arroyo, J. Experiential purchases and feeling autonomous: Their implications for gratitude and ease of justification. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1033630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yuen, K.F.; Fang, M. When the winds of change blow: An empirical investigation of ChatGPT’s usage behaviour. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S.; Ling, C.-J.; Lee, D.-R.; Chen, C.-W. How personality traits affect customer empathy expression of social media ads and purchasing intention: A psychological perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Pang, Q.; Kim, W.; Yao, J.; Fang, M. Consumer participation in reusable resource allocation schemes: A theoretical conceptualization and empirical examination of Korean consumers. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 189, 106747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, W.T. Information and compassion in crisis responses: A test of their effects. J. Public Relat. Res. 1999, 11, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Song, S. An empirical investigation of electronic word-of-mouth: Informational motive and corporate response strategy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, A.P.; Warren, C.; Kan, C. Humorous complaining. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1153–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Marketing as exchange. J. Mark. 1975, 39, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, R.; Burnkrant, R.E.; Unnava, H.R. Consumer response to negative publicity: The moderating role of commitment. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, L.T. Trust: The connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O. Is self-mockery in advertising copywriting an efficient strategy to build brand closeness and purchase intention? J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.L. Research perspectives on consumer complaining behavior. Theor. Dev. Mark. 1980, 2, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kobel, S.; Groeppel-Klein, A. No laughing matter, or a secret weapon? Exploring the effect of humor in service failure situations. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, C.L.; Donthu, N.; Yoo, B. Brand authenticity: Literature review, comprehensive definition, and an amalgamated scale. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2023, 31, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kaushik, A.K. Engaging customers through brand authenticity perceptions: The moderating role of self-congruence. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F.; Malär, L.; Guèvremont, A.; Girardin, F.; Grohmann, B. Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, J.; Dickinson, S.J.; Beverland, M.B.; Farrelly, F. Measuring consumer-based brand authenticity. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, B. Exploring the moderators and causal process of trust transfer in online-to-offline commerce. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Peng, Z.; Ma, X. Exploring the effects of self-mockery to improve task-oriented chatbot’s social intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Virtual Event, 13–17 June 2022; pp. 1315–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, G.R.; Park, J.-E. Salesperson adaptive selling behavior and customer orientation: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Laroche, M.; Richard, M.-O.; Cui, X. More than a mere cup of coffee: When perceived luxuriousness triggers Chinese customers’ perceptions of quality and self-congruity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Munuera-Alemán, J.L. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Kang, J.; Hyun, S.S.; Fu, X.X. The impact of brand authenticity on building brand love: An investigation of impression in memory and lifestyle-congruence. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, V.; Gulertekin Genc, S. The effect of perceived authenticity in cultural heritage sites on tourist satisfaction: The moderating role of aesthetic experience. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Guo, R. The effect of a green brand story on perceived brand authenticity and brand trust: The role of narrative rhetoric. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Understanding repurchase intention of Airbnb consumers: Perceived authenticity, electronic word-of-mouth, and price sensitivity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Prado, P.H.M.; Korelo, J.C.; Frizzo, F. The effect of brand authenticity on consumer–brand relationships. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Wang, W.-C. Effects of authenticity perception, hedonics, and perceived value on ceramic souvenir-repurchasing intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, C.M.; Pounders, K.R. Transforming celebrities through social media: The role of authenticity and emotional attachment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Brandão, A.; Billore, S.; Oda, T. The mediating role of perceived brand authenticity between brand experience and brand love: A cross-cultural perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2024, 31, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.; Vardarsuyu, M.; Oghazi, P. Examining the relationships between brand authenticity, perceived value, and brand forgiveness: The role of cross-cultural happiness. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 114154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-F.; Wu, C.-M. Satisfaction and post-purchase intentions with service recovery of online shopping websites: Perspectives on perceived justice and emotions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wan, Y.H.; Su, X. Identifying individual expectations in service recovery through natural language processing and machine learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 131, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin Andreassen, T. Antecedents to satisfaction with service recovery. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B.R.; Kim, S.-E. Effect of brand experiences on brand loyalty mediated by brand love: The moderated mediation role of brand trust. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2412–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.C.; Lu, T.E.; Peng, M.Y. Service failure recovery on customer recovery satisfaction for airline industry: The moderator of brand authenticity and perceived authenticity. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 42, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.D. Service failure recovery on customer recovery satisfaction and attitude loyalty for airline industry: The moderating effect of brand authenticity. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2296145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, B.H. Integrity or compliance based ethics: Which is better for today’s business? Open J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 5, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Johnson, L.W.; McDonald, R. Celebrity endorsements, self-brand connection and relationship quality. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, N. Brand Self-deprecating Humor Response Strategy after Brand Misconduct. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 36, 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- Bieg, S.; Grassinger, R.; Dresel, M. Humor as a magic bullet? Associations of different teacher humor types with student emotions. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2017, 56, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.S.; Chien, C.S.; Pant, A.; Lee, M. The challenges of long-distance relationships: The effects of psychological distance between service provider and consumer on the efforts to recover from service failure. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. Assessing construct validity: The utility of factor analysis. J. Educ. Stat. 2007, 15, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: London, UK, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model.-A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchait, P.; Paşamehmetoğlu, A.; Dawson, M. Perceived supervisor and co-worker support for error management: Impact on perceived psychological safety and service recovery performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Mattila, A.S. Consumer responses to compensation, speed of recovery and apology after a service failure. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004, 15, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambier, F.; Poncin, I. Inferring brand integrity from marketing communications: The effects of brand transparency signals in a consumer empowerment context. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1983, 14, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Fang, M.; Wang, L.; Mi, K.; Su, M. Increasing couriers’ job satisfaction through social-sustainability practices: Perceived fairness and psychological-safety perspectives. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).