Abstract

With the rise of live-streaming services on e-commerce platforms, AI-powered virtual idols have demonstrated tremendous application potential and thus possess high commercial value. From the perspective of psychological distance, this study adopts the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) theoretical framework to construct a research model of “AI-powered virtual idols–psychological distance–impulsive buying intention”. The model aims to explore how AI-powered virtual idols promote digital natives’ impulsive buying intention in the context of e-commerce live streaming. Furthermore, this study examines the moderating effect of technology readiness on the relationship between AI-powered virtual idols and psychological distance. The findings reveal that the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols—including interactivity, anthropomorphism, homogeneity, and reputation—enhances digital natives’ impulsive buying intention by reducing psychological distance. For digital natives with lower technology readiness, the effect of AI-powered virtual idols in narrowing psychological distance is more pronounced. These findings enrich AI-driven consumer behavior models from a theoretical perspective and offer theoretical support and practical insights for developing AI-empowered digital marketing strategies tailored to the psychological traits and technological adaptability of digital natives.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI), AI-powered virtual idols have emerged as important marketing agents and tools in virtual consumption environments, playing an increasingly prominent role. In particular, the rise of live streaming on e-commerce platforms has highlighted the immense application potential and commercial value of AI-powered virtual idols. Leveraging cutting-edge technologies such as machine learning, natural language processing, and motion capture, AI-powered virtual idols can engage in real-time interactions with platform users through high levels of anthropomorphism and interactivity. These capabilities enable them to detect consumers’ shopping preferences and recommend suitable products accordingly. Advances in AI technology have not only significantly enhanced the expressiveness of virtual idols but also laid the foundation for their commercialization, allowing them to evolve from traditional anime-style characters into innovative marketing tools that combine entertainment and utility.

Compared with human streamers, AI-powered virtual idols offer several advantages, such as 24/7 availability, reduced need for supervision, and controllable content. Moreover, due to their ambiguous status on the “human–nonhuman” spectrum, they can evoke users’ curiosity and emotional resonance, effectively stimulating purchase intentions [1]. Globally, the industrial development of AI-powered virtual idols is accelerating. For example, the American social media influencer “Lil Miquela” has captured the attention of a large number of young users through her hyper-realistic appearance and everyday social interactions. In China, the virtual idol “Luo Tianyi” frequently appears in live streaming and large-scale entertainment events, showcasing remarkable adaptability and influence across diverse media environments [2]. These iconic cases suggest that AI-powered virtual idols are becoming one of the key channels through which e-commerce brands connect with younger consumers and boost transaction volumes.

As a novel technological force, AI-powered virtual idols are more easily accepted and exert a stronger marketing influence among Generation Z and younger digital natives. Digital natives are individuals who have grown up in digital environments and generally possess high levels of information sensitivity and technological adaptability. In their consumption processes, they are more inclined to make decisions based on social interactions and immersive experiences [3,4]. Chen et al. (2024) [5] found that compared with traditional advertising, digital natives are more likely to form para-social relationships with AI-powered virtual idols. Furthermore, the high-frequency interactivity, anthropomorphic expressions, and identity congruence of AI-powered virtual idols can significantly enhance users’ emotional attachment and social identification, thereby increasing user stickiness and the intention for continued consumption among digital natives [6,7].

However, despite prior research indicating that AI-powered virtual idols can significantly improve user purchase intention, their underlying impact mechanisms remain underexplored. First, few studies have investigated how such mechanisms function specifically within live streaming contexts—namely, how and whether AI-powered virtual idols influence consumer behavior during live streaming on e-commerce platforms. Second, the existing literature has yet to examine the mechanism by which AI-powered virtual idols affect consumers’ impulse purchase intention. In response to these gaps, this study adopts a psychological distance perspective and employs the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) theoretical framework to develop a research model of “AI-powered virtual idol–psychological distance–impulse purchase intention.” Additionally, this study incorporates the concept of technology readiness to examine its moderating role in the effect of AI-powered virtual idols on psychological distance. The findings of this research aim to enrich and extend the understanding of consumer behavior among digital natives in the context of AI, while offering theoretical guidance and practical insights for brand managers seeking to leverage AI technologies in digital marketing strategies.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. AI-Powered Virtual Idols and Digital Natives’ Impulse Purchase Intention

As AI-powered digital characters, virtual idols integrate anthropomorphic appearances, graphic and animation effects, and natural language processing algorithms to offer realistic visual representation and continuous human–machine interaction [8,9,10]. On e-commerce platforms, AI-powered virtual idols are capable of engaging in human-like communication and interaction with users, thereby enhancing emotional bonds during the shopping process and increasing user affection toward the brand, which subsequently elevates their purchase intention [11]. In this context, the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols serves as the foundation and determinant of whether and to what extent these enhancement mechanisms can be realized. Specifically, four key dimensions are involved: interactivity [12], anthropomorphism [1], homogeneity [13], and reputation [14].

Interactivity refers to a medium’s characteristic that enables users to perceive and engage in a two-way information exchange, creating experiences akin to real interpersonal interactions [15]. Based on social influence theory, Akhtar et al. (2024) [16] found that the interactivity of virtual influencers significantly enhances consumers’ online engagement through both normative and informational pathways. Yu et al. (2023) [8] confirmed that interactivity plays a critical role in establishing emotional bonds with consumers and influencing their purchasing decisions. Du et al. (2025) [17] constructed a dual-mediation model and found that the interactivity of virtual idols enhances consumers’ sense of immersion, thus promoting purchase intentions.

Anthropomorphism, as a psychological attribution process, refers to individuals projecting human characteristics or intentions onto non-human entities based on their cognitive schemas, thereby endowing these entities with human-like traits and meanings [18]. Liu and Wang (2025) [1] demonstrated that the degree of anthropomorphism of virtual streamers influences users’ engagement and purchasing decisions through perceptions of real-world and identity threats. Chen et al. (2024) [5] argued that highly anthropomorphic AI personas reduce psychological distance with consumers, thereby enhancing their willingness for continuous consumption. However, Li and Huang (2024) [19] cautioned that excessive anthropomorphism may trigger the “uncanny valley effect”, diminishing user participation [6].

Homogeneity refers to groups within social networks who share similar interests, backgrounds, beliefs, or traits, and are thus more likely to connect and interact [20]. Du et al. (2025) [17] found that homogeneity fosters psychological closeness between consumers and virtual idols, which increases purchase intention. In the fashion industry, Toyib and Paramita (2024) [13] observed that the homogeneity of AI-powered virtual idols enhances consumers’ acceptance of the products they endorse.

Reputation denotes the degree to which an individual is publicly recognized and widely acknowledged within sociocultural contexts. Reputation is not only reflected in fame and visibility, but also in the transmission of cultural meanings (e.g., via celebrity endorsement), which shapes and influences consumer perceptions and attitudes toward products and brands [21]. Huang et al. (2023) [22], in a study on TikTok, compared Chinese Gen Z fans’ preferences for human versus AI virtual idols, finding that higher reputation among AI-powered virtual idols led to stronger user loyalty, emotional bonding, and ultimately, increased purchase preferences and intentions.

To provide a clear overview of the existing research, Table 1 summarizes the representative literature, including key topics and the associated variables or conceptual models.

Table 1.

Summary table of key parameters in the literature.

Compared to other user groups, digital natives—a new generation of consumers who have grown up in a digital environment—exhibit high technological adaptability and social interaction tendencies [23]. They are accustomed to acquiring product information through emerging shopping channels such as social media, e-commerce platforms, and live streaming, and prefer digital consumption behaviors including mobile payments and virtual try-on technologies [3]. Furthermore, digital natives show strong preferences for interactivity and homogeneity in their consumption experiences, with their decisions more easily influenced by emotional connection and social identity [24,25]. In particular, under a live-streaming context, they tend to make purchase decisions through highly interactive and psychologically proximate new media, reflecting their high adaptability to digital technology and immersive experiences.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

In an e-commerce live-streaming context, the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols has a significantly positive effect on the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives.

2.2. The Mediating Mechanism of Psychological Distance

Psychological distance refers to individuals’ subjective perception of a specific object at emotional, cognitive, or experiential levels. Its primary dimensions include spatial, social, temporal, and hypothetical distance [26]. Prior studies have shown that AI-powered virtual idols in an e-commerce live-streaming context can effectively shorten the psychological distance between consumers and digital personas by enhancing social presence and emotional connection through interactivity, anthropomorphism, homogeneity, and reputation [27,28]. Regarding interactivity and anthropomorphism, Sun et al. (2024) [11] found that highly interactive and human-like AI virtual agents significantly enhance users’ social presence and reduce feelings of psychological alienation. Lv et al. (2022) [29] further revealed a negative relationship between the interactivity of AI virtual streamers and viewers’ perceived psychological distance. Through a series of four experiments, Franke and Groeppel-Klein (2024) [30] demonstrated that virtual idols with high levels of human-likeness are perceived as more credible, thereby significantly reducing psychological distance. Similarly, Liu et al. (2024) [31] indicated that increasing the degree of anthropomorphism enhances users’ sense of trust and identification, which in turn decreases the psychological distance between users and virtual influencers. In terms of homogeneity, Ashrafi et al. (2024) [32] found that virtual characters that closely resemble users in appearance are more likely to evoke emotional resonance and engagement motivation, thereby narrowing psychological distance. Mehrotra et al. (2021) [33] emphasized that when users perceive shared values with AI agents, their trust and acceptance of the virtual entities increase significantly, which further reduces psychological distance. Additionally, brand reputation and perceived sincerity have also been confirmed as effective factors in decreasing the psychological distance between users and brands [27]. Furthermore, digital natives are particularly sensitive to psychological distance in emerging digital consumption contexts such as live streaming. Their decision-making processes are more susceptible to changes in perceived distance. Prior studies have revealed that psychological distance between consumers and reviewers negatively impacts information acceptance and purchase decision-making [34]. Sun et al. (2024) [35] observed that a shorter psychological distance leads to higher customer engagement and stronger purchase intention. Based on affordance theory, Wang et al. (2024) [36] argued that enhancing users’ sense of participation and immersion can reduce psychological distance and thus boost purchasing willingness. Tang and Hu (2017) [37] further pointed out that greater psychological distance amplifies consumers’ perceptions of uncertainty and risk, prompting more cautious decision-making, whereas closer psychological distance fosters trust and facilitates purchase behavior. Based on the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) theoretical framework, Ling and Zheng (2024) [38] explored the relationship between psychological distance and purchase intention in the context of live streaming, and found that as time pressure increases, the impact of psychological distance on purchase intention becomes more pronounced. From the perspective of social commerce, Yang (2022) [39] found that a shorter psychological distance can increase perceived value and reduce the cognitive load, thereby enhancing purchase intention. In addition, Cui et al. (2020) [40] demonstrated that reducing perceived psychological distance strengthens consumers’ trust and commitment to cross-border mobile commerce (CBMC) platforms, which in turn increases both usage intention and purchase frequency. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2.

In an e-commerce live-streaming context, psychological distance mediates the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and digital natives’ impulse purchase intention.

H2a.

In an e-commerce live-streaming context, the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols has a significantly negative effect on psychological distance (i.e., higher intelligence leads to shorter psychological distance).

H2b.

In an e-commerce live-streaming context, psychological distance has a significantly negative effect on digital natives’ impulse purchase intention (i.e., the shorter the psychological distance, the stronger the impulse purchase intention).

2.3. The Moderating Role of Technology Readiness

Technology readiness refers to users’ psychological inclination to accept and confidently use emerging technologies, and it is regarded as a key antecedent for predicting individuals’ technology adoption behaviors [41]. It not only influences users’ overall attitude toward technological acceptance but also significantly moderates their cognitive and behavioral responses to technological features [42]. Lowry et al. (2012) [43] found that technology readiness, as an individual trait, can moderate psychological variables such as perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, thereby affecting users’ perceived psychological distance [44].

In the interaction between users and AI virtual idols, users with high technology readiness typically demonstrate greater adaptability and comprehension, hold more positive attitudes toward new technologies [45], and exhibit a higher level of trust [46,47]. These users are more capable of actively perceiving and accepting the interactivity and convenience brought by AI virtual idols, thus effectively reducing the psychological distance between users and virtual idols [48,49]. In contrast, users with low technology readiness may lack confidence or experience a higher cognitive load, which can lead to skepticism toward AI virtual idols. This, in turn, may result in psychological resistance, expressed through suspicious attitudes and emotional tension [50], thereby diminishing the effectiveness of AI virtual idols in narrowing psychological distance [51]. Moreover, Qin et al. (2025) [52] further revealed that a human-like appearance design of AI agents tends to have a more positive impact on users with higher levels of technology readiness, enhancing their perceived trust and attractiveness toward AI virtual idols. Similarly, Doorn et al. (2017) [53] suggested that technology-ready users are more likely to perceive the “warmth” of service robots, forming emotional connections and anthropomorphic perceptions. Such tendencies may also emerge in interactions with AI virtual idols, making it easier for users to accept their social and emotional attributes, thereby reducing psychological distance and enhancing intimacy and immersion during interactions [54].

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

In an e-commerce live-streaming context, technology readiness moderates the relationship between the perceived intelligence of AI virtual idols and psychological distance.

2.4. Research Model

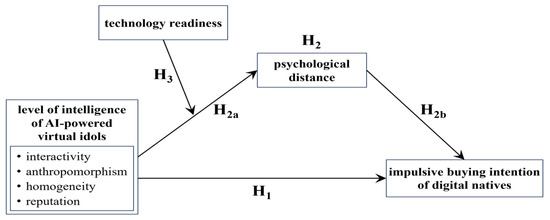

Based on the aforementioned analysis, this study proposes the following research model, as illustrated in Figure 1. The subsequent sections will empirically test this model using large-sample data collected through a structured questionnaire, analyzed with SPSS 26.0 statistical software.

Figure 1.

Research model of this study.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

This study employed a questionnaire survey to collect sample data from “digital natives” in mainland China between September 2024 and March 2025. Based on existing validated questionnaires from previous research, the original items were appropriately revised to align with the objectives of this study. To minimize measurement bias during the revision process, the core structure and measurement dimensions were retained, with only key concepts and terminology adjusted (as shown in Table A1).

A total of 1850 questionnaires were distributed via major e-commerce platforms such as Xiaohongshu, Douyin, Taobao, and Pinduoduo, resulting in 1323 responses, yielding a response rate of 71.51%.

Following the effective questionnaire screening criteria proposed by Lin et al. (2021) [55], the study adopted the following mechanisms:

- (1)

- Based on the estimated completion time of 5–10 min, responses completed in under 3 min were excluded as careless answers;

- (2)

- Questionnaires showing patterned responses (e.g., all responses marked as “1” or “5”) or containing extreme values were removed;

- (3)

- IP addresses recorded via the WJX platform were checked to eliminate duplicate submissions from the same IP;

- (4)

- A screening question was used to identify respondents, and those who were not digital natives or lacked a basic knowledge of concepts such as AI-powered virtual idols were excluded.

Ultimately, 741 valid responses were retained for data analysis, resulting in an effective response rate of 56.01%.

3.2. Variable Measurement

All variables in this study were measured using a five-point Likert scale. Control variables included gender, educational level, monthly disposable consumption amount, and monthly frequency of live shopping participation. Gender was categorized as male and female. Education level was classified into four levels: high school or below, associate degree, bachelor’ s degree, and master’s degree or above. Monthly disposable consumption amount was divided into four brackets: less than RMB 1000; RMB 1000–5000; RMB 5000–10,000; and more than RMB 10,000. Monthly frequency of live shopping participation was measured in four categories: 0 times, 1–3 times, 4–6 times, and 7 times or more. Descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the sample (N = 741).

3.3. Hypothesis and Empirical Testing Significance Summary

To provide a clear overview of the results from the hypothesis testing, Table 3 summarizes the statistical significance and conclusions for each proposed hypothesis. The table includes test values, significance levels, and whether the data support the respective hypotheses.

Table 3.

Hypothesis and empirical testing significance summary.

4. Empirical Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.1.1. Reliability Analysis

This study employed SPSS 26.0 to conduct a reliability analysis on the constructs of AI virtual idols’ intelligence level, psychological distance, technology readiness, and digital natives’ impulse purchase intention. Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and Corrected Item–Total Correlation (CITC). Specifically, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for 22 questionnaire items, as shown in Table 4. All item–total correlations exceeded 0.5, and the coefficients remained stable even if individual items were deleted, indicating that the item design was appropriate. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.7, demonstrating good overall reliability of the scales. The stability of the measurement instruments and the reliability of the data were thus confirmed, supporting the robustness of the study’s findings.

Table 4.

Reliability test of scale items (N = 741).

4.1.2. Validity Analysis

The design of the scale items in this study strictly adheres to the standards for developing scientific measurement instruments. Based on a systematic review of authoritative studies from both domestic and international sources, empirically validated scales were selected and subsequently localized and adapted to ensure item accuracy and contextual relevance, thereby establishing strong content validity.

For construct validity, factor extraction and analysis were conducted using the maximum likelihood method with varimax rotation. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values calculated via SPSS 26.0 all exceeded the conventional threshold of 0.6, indicating a strong correlation among variables. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), rejecting the null hypothesis of variable independence. These results confirm the suitability of the data for factor analysis.

The factor analysis further revealed that all item factor loadings exceeded the minimum standard of 0.5, suggesting that the scale effectively captures the core attributes of the theoretical constructs. The measurement results align with theoretical expectations. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Validity assessment of scale items (N = 741).

4.2. Correlation Analysis

This study employed an equal-weighting method to integrate the four characteristics of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols in an e-commerce live-streaming context—interactivity, anthropomorphism, homogeneity, and reputation—into a composite variable that reflects their overall influence. Specifically, each feature was assigned an equal weight of 25%, and all variables were standardized using Z-score normalization to ensure consistency of scale. By constructing the composite variable with equal weights, the overall level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols can be objectively represented in the absence of a clear theoretical priority among the dimensions.

A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and the impulse buying intention of digital natives in an e-commerce live-streaming context. As shown in Table 6, psychological distance exhibited a significant negative correlation with the impulse buying intention of digital natives (r = −0.713), while the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols showed a significant positive correlation with the impulse buying intention of digital natives (r = 0.794). These results support the theoretical assumptions regarding the relationships among the key variables and lay the foundation for subsequent hypothesis testing.

Table 6.

Correlations among variables (N = 741).

4.3. Regression Analysis

4.3.1. The Impact of the Level of Intelligence of AI-Powered Virtual Idols on Digital Natives’ Impulse Purchase Intention

This study employs a linear regression analysis to quantitatively describe the relationships among variables. Digital natives’ impulse purchase intention was set as the dependent variable, and the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols was set as the independent variable. The regression model results are presented in Table 5. The Durbin–Watson (D–W) value is 1.932, close to 2, indicating no autocorrelation in the model. Additionally, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) are all below 2, suggesting no multicollinearity issues among the variables, allowing for further analysis.

As shown in Table 7, the regression coefficient of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols on digital natives’ impulse purchase intention is 0.685 and is statistically significant (p < 0.001). The coefficient of determination R2= 0.632 indicates a strong explanatory power of the model. The adjusted R2 = 0.629 shows that the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols explains 62.9% of the variance in digital natives’ impulse purchase intention. The F-value is 252.335 (p < 0.001), also statistically significant. These results demonstrate a positive correlation between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and digital natives’ impulse purchase intention, supporting Hypothesis H1. Specifically, in an e-commerce live-streaming context, the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols has a significant positive effect on the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives.

Table 7.

The effect of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols on the impulse purchase intention of digital natives.

Control variables such as gender, education level, disposable consumption amount, and frequency of live shopping did not reach statistical significance. This finding suggests that digital natives’ impulse purchase decisions depend more on the experiential process with AI-powered virtual idols in an e-commerce live-streaming context than on traditional demographic characteristics. The inclusion of control variables helps to rule out alternative explanations and enhances the robustness of the statistical tests.

4.3.2. Analysis of the Effect of the Level of Intelligence of AI-Powered Virtual Idols on Psychological Distance

This study employed a linear regression analysis with the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols as the independent variable and psychological distance as the dependent variable. As shown in Table 8, the Durbin–Watson (D–W) statistic is 1.913, which is close to 2, indicating that there is no autocorrelation in the regression model. The variance inflation factors (VIF) for all predictors are below 2, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a concern in this analysis.

Table 8.

Effect of the level of intelligence of AI-Powered virtual idols on psychological distance.

The regression coefficient of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols on psychological distance is −0.682 and is statistically significant (p < 0.001). The model yields an R2 of 0.638, indicating a high explanatory power. The adjusted R-squared is 0.635, which means that 63.5% of the variance in psychological distance can be explained by the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols. The F-statistic is 258.958 (p < 0.001), demonstrating the overall significance of the model.

Control variables such as gender and education level do not show statistically significant effects, suggesting that the reduction in psychological distance primarily depends on the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols rather than users’ demographic characteristics. These findings confirm that the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols has a significant negative effect on psychological distance, supporting Hypothesis H2a. In other words, in an e-commerce live-streaming context, the higher the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols, the shorter the perceived psychological distance.

4.3.3. The Effect of Psychological Distance on the Impulsive Purchase Intention of Digital Natives

This study conducted a linear regression analysis with psychological distance as the independent variable and the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives as the dependent variable. As shown in Table 9, the regression coefficient of psychological distance on impulsive purchase intention was −0.707 (p < 0.001), and the result was statistically significant. The adjusted R2 of the model was 0.507, which is slightly lower than that of the direct effect model but still demonstrates strong explanatory power. The model’s F-value was 153.501 (p < 0.001), also indicating statistical significance. These results suggest that psychological distance has a significantly negative effect on the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives, supporting Hypothesis H2b. In other words, in an e-commerce live-streaming context, the shorter the psychological distance perceived by digital natives, the stronger their impulsive purchase intention.

Table 9.

The effect of psychological distance on the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives.

4.3.4. Analysis of the Mediating Role of Psychological Distance

As shown in Table 10, this study employed a Bootstrap mediation test to examine the mediating effect of psychological distance in the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives. The total effect was 0.685 (p < 0.001), with the mediating effect accounting for 22.04% of the total effect. The 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect was [0.093, 0.206], which does not include zero, indicating a significant mediating effect. These results suggest that psychological distance plays a significant partial mediating role in the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives, thus supporting Hypothesis H2.

Table 10.

Test of the mediating role of psychological distance.

4.3.5. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Technology Readiness

This study employs a hierarchical linear regression model to test the moderating role of technology readiness in the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and psychological distance. Before calculating the interaction term, both the independent variable and the moderator are mean-centered. Then, the two centered variables are multiplied to obtain the interaction term. This procedure aims to eliminate multicollinearity issues between the interaction term and the control and independent variables.

The test of the moderating effect involves four steps: First, psychological distance is taken as the dependent variable, and control variables (gender, education level, monthly disposable consumption amount, and monthly frequency of live shopping participation) are entered in Step 1, yielding Model M1. Second, the independent variable (the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols) is entered in Step 2, yielding Model M2. Third, the moderator (technology readiness) is added in Step 3, yielding Model M3. Finally, based on Model M3, the interaction term between the mean-centered level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and technology readiness is added, yielding Model M4.

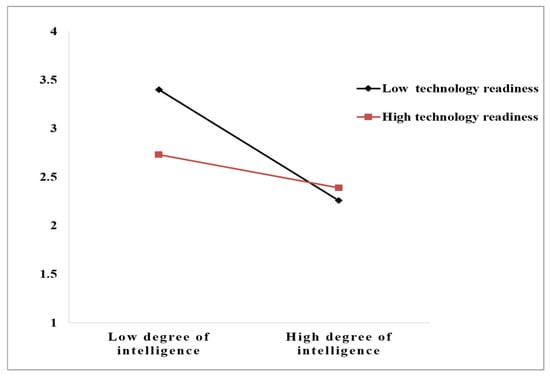

As shown in Table 11, the test results of regression model M4 indicate that after adding the interaction term, the explanatory power of the model improved (ΔR2 = 0.018, p < 0.001). This suggests that technology readiness has a moderating effect between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and psychological distance (β = 0.200, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H3. The positive coefficient of the interaction term indicates that an increase in technology readiness significantly weakens the impact of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols on psychological distance. In other words, the higher the technology readiness, the weaker the effect of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols in reducing psychological distance. To more intuitively illustrate the moderating effect of technology readiness between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and psychological distance, this study plotted the moderation effect diagram (Figure 2).

Table 11.

Test of the moderating effect of technology readiness.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the moderating effect of technology readiness.

According to Figure 2, technology readiness has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and psychological distance. Under low technology readiness conditions, the negative slope of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols on psychological distance is steeper, indicating that as the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols increases, the effect of shortening psychological distance is enhanced. Under high technology readiness conditions, the slope is flatter, indicating that as the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols increases, the effect of shortening psychological distance weakens. Therefore, hypothesis H3 is supported.

5. Conclusions, Implications, and Future Directions

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the perspective of psychological distance and utilizing the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) theoretical framework, this study constructs a research model of “AI-powered virtual idol–psychological distance–impulsive purchase intention” to investigate how AI-powered virtual idols promote the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives in an e-commerce live-streaming context. Through a large-sample empirical test, this study confirms that psychological distance plays a significant mediating role between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives, while technology readiness significantly moderates the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and psychological distance.

Specifically, the research findings include the following three aspects: (1) In an e-commerce live-streaming context, the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols has a significant positive impact on the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives. Specifically, the interactivity of AI-powered virtual idols effectively enhances users’ sense of engagement and trust, thereby driving the formation of impulsive purchase intention. Anthropomorphism helps evoke consumers’ emotional resonance and a sense of intimacy, improving their psychological acceptance. Homogeneity strengthens users’ identification and sense of belonging, thus fostering impulsive purchase motivation. Reputation reinforces consumers’ brand trust and sense of security while reducing their perceived risks. (2) Psychological distance partially mediates the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives. In an e-commerce live-streaming context, the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols indirectly enhances users’ impulsive purchase intention by reducing the psychological distance between users and the brand. This further validates that the shortening of psychological distance is an important psychological mechanism in technology-driven marketing strategies. (3) Technology readiness moderates the effect of the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols on psychological distance. In an e-commerce live- streaming context, users with lower technology readiness are more sensitive to the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols. This indicates that the lower the technology readiness, the stronger the effect of AI-powered virtual idols’ intelligence level in reducing psychological distance. Conversely, higher technology readiness weakens this effect. This finding provides theoretical support for differentiated marketing strategies targeting diverse user groups.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study offers marginal theoretical contributions in the following three aspects:

First, from the perspective of psychological distance, this paper constructs a research framework of “AI-powered virtual idols–psychological distance–impulse purchase intention” based on the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) theoretical model. By introducing psychological theory into the interdisciplinary study of AI-powered virtual idols and consumer behavior, this research advances beyond previous approaches that focused mainly on the technology itself or marketing outcomes. Instead, it emphasizes how the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols influences consumer behavior through psychological mechanisms, thereby deepening our understanding of the psychological logic underlying AI-driven marketing strategies. Particularly in a live-streaming e-commerce context, the S–O–R model provides theoretical support for explaining how the intelligence level of AI-powered virtual idols (stimulus) triggers users’ (organism) psychological responses, which in turn affect their impulse purchase intention (response).

Second, this study identifies and empirically tests the mediating role of psychological distance in the relationship between the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols and digital natives’ impulse purchase intention, thereby extending the application boundary of psychological distance theory in digital consumption contexts. The findings reveal that AI-powered virtual idols can effectively reduce psychological distance between users and brands by enhancing features such as interactivity, anthropomorphism, homogeneity, and reputation, thereby increasing impulse purchase intention. This not only enriches the understanding of the concept of psychological distance but also reveals its dynamic adaptability in digital environments. Especially in AI-enabled marketing contexts, changes in psychological distance serve as a key mechanism through which digital technologies translate into consumer purchase motivation, offering a new theoretical lens for integrating technology acceptance and consumer psychology research.

Finally, this study introduces technology readiness as a moderating variable, uncovering the significant influence of individual technological traits on the regulatory pathway of psychological distance during AI technology adoption. It further clarifies the mechanism and boundary conditions through which AI-powered virtual idols influence consumer behavior. The results show that for users with higher technology readiness, the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols has a more significant effect in shortening psychological distance, whereas this effect is relatively weaker for users with lower technology readiness. This finding not only addresses the current neglect of user heterogeneity in existing technology acceptance models but also provides a theoretical basis for designing differentiated AI marketing strategies. Moreover, by integrating users’ technological traits into the analytical framework of technology acceptance and psychological mechanisms, this study offers stronger theoretical support for the optimization of personalized marketing strategies and user segmentation.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study offers important practical implications, which are reflected in the following three aspects:

- (1)

- Brand operators on e-commerce platforms should continuously enhance the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols to optimize users’ shopping experience and thereby increase the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives. For instance, enterprises should strengthen collaborations with third-party AI technology development teams and regularly upgrade the intelligence level of AI-powered virtual idols. First, by incorporating advanced natural language processing algorithms, AI-powered virtual idols can gain deeper insights into the needs of digital natives and deliver personalized product recommendations and service feedback with greater precision. Second, by utilizing deep learning and computer vision technologies, companies can iteratively improve the facial expressions, vocal tone, and body movements of virtual idols, thereby enhancing their expressiveness and realism. This, in turn, increases the accuracy of emotional interaction during live streaming, ultimately improving the user’s shopping experience.

- (2)

- AI-powered virtual idols’ virtual settings and interactive interfaces should be continuously optimized to reduce users’ psychological distance. By leveraging algorithms to accurately capture and interpret user preferences and market trends, platforms can optimize the live-streaming interface and create immersive interactive scenes with a stronger sense of presence. Incorporating VR and AR technologies, features such as virtual try-on, product previews, and spatial demonstrations can be developed to allow users to intuitively perceive product characteristics and usage effects. These enhancements effectively reduce psychological distance, boost real-time purchase confidence, and increase buying intention.

- (3)

- Target user groups should be precisely segmented, with a specific focus on understanding the needs of users with lower levels of technology readiness (rather than those with higher readiness). Enterprises should conduct data mining and market research to accurately identify and respond to the needs of low-tech-readiness users, thereby improving overall marketing efficiency. Platforms should simplify the operational complexity of user interfaces and improve usability to help users with lower technology readiness gradually adapt to and trust new shopping formats. Enhancing their willingness to participate and interest in using the platform can unlock significant latent consumption potential.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study preliminarily reveals the underlying mechanism by which the level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols influences the impulsive purchase intention of digital natives in an e-commerce live-streaming context, it still has certain research limitations despite the alignment between its research design—including methodological choices, scale item construction, and sample data collection—and the study’s overarching theme. First, the user sample is primarily focused on digital natives in China, thus the generalizability of the findings across generational and cross-cultural contexts requires further investigation. Second, while cross-sectional data effectively examine the correlations among variables, it is limited in capturing the dynamic mechanisms and evolutionary patterns under changing scenarios. Third, this study considers only a single moderating variable—technology readiness—without fully incorporating other contextual factors such as product attributes and cultural backgrounds, which may significantly influence the proposed research model. Last, while the S–O–R model effectively reveals the mechanism by which the intelligence level of AI-powered virtual idols influences impulsive buying intention, its limitation lies in overlooking individual differences and contextual complexities—such as cultural background and technology readiness—that moderate psychological distance and consumer responses, making it difficult to fully capture the dynamic psychological reactions of digital natives.

For future research, the sample could be expanded to include digital natives across countries, generations, and socio-cultural dimensions. First, future studies should integrate longitudinal tracking designs with cross-cultural comparative approaches to (1) deepen the dynamic analysis of behavioral changes among digital natives, (2) explore the effects of varying interaction modes in digital live streaming and differences in product types, and (3) construct a cross-dimensional analytical framework that encompasses the interplay among technology, individual, and contextual factors. Second, future research should pay close attention to the potential cognitive and ethical risks, moral dilemmas, and suppressive effects on consumer decision-making that may arise from the excessive intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols. This would contribute to a more balanced development of both theoretical critique and practical guidance. Finally, from a methodological perspective, future studies may incorporate interdisciplinary and emerging technologies—such as neural experiments and affective computing—to overcome the inherent limitations of traditional survey-based data collection. By decoding users’ implicit cognitive mechanisms through multimodal approaches, these efforts could offer a more mature and systematized theoretical foundation for optimizing human–machine–product synergy in commercial practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and W.L.; methodology, H.L. and T.M.; data curation, H.L. and T.M.; investigation, T.M.; formal analysis, H.L. and T.M.; writing—original draft, H.L., W.L. and T.M.; writing—review and editing, H.L., W.L. and T.M.; visualization, T.M. and W.L.; supervision, H.L.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 24AGL016).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their reviews and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Scale items design of the survey questionnaire.

Table A1.

Scale items design of the survey questionnaire.

| Variables | Code | Item | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The level of intelligence of AI-powered virtual idols in E-commerce Live-streaming context | interactivity | A1 | In live streaming, the AI-powered virtual idol can respond promptly to my comments or questions. | Liu et al. [31] |

| A2 | In live streaming, the AI-powered virtual idol initiates interactions by actively introducing topics. | |||

| A3 | The live-streaming content presented by the AI-powered virtual idol is dynamically adjusted based on my feedback. | |||

| anthropomorphism | B1 | The appearance design of AI-powered virtual idols is realistic and close to that of real humans. | Golossenko et al. [56] | |

| B2 | AI-powered virtual idols adjust their expressions and emotions according to product characteristics. | |||

| B3 | AI-powered virtual idols have fixed catchphrases or signature gestures similar to real streamers. | |||

| homogeneity | C1 | In live streaming, the interests and hobbies of AI-powered virtual idols are similar to mine. | Ladhari et al. [57] | |

| C2 | In live streaming, the language style of AI-powered virtual idols matches my communication habits. | |||

| C3 | In live streaming, the cultural elements displayed by AI-powered virtual idols make me feel familiar and close. | |||

| reputation | D1 | I often see product recommendations from certain AI-powered virtual idols on e-commerce platforms. | Friedman et al. [58] | |

| D2 | The number of fans of a certain AI-powered virtual idol makes me feel that it is worth paying attention to. | |||

| D3 | A certain AI-powered virtual idol has a high frequency of media exposure (e.g., advertisements, variety shows). | |||

| psychological distance | E1 | The live streaming by a certain AI-powered virtual idol shortens the psychological distance between me and the product. | Trope and Liberman. [26] | |

| E2 | The live streaming of a certain AI-powered virtual idol deepens my emotional attachment to the product. | |||

| E3 | The live streaming by a certain AI-powered virtual idol reduces my unfamiliarity with the brand. | |||

| technology readiness | F1 | I believe AI-powered virtual idol live streaming can make shopping more convenient and improve shopping quality. | Parasuraman [41] | |

| F2 | I like to follow AI technology developments and tend to watch live streaming hosted by AI-powered virtual idols. | |||

| F3 | I worry that technical failures of AI-powered virtual idols might affect our shopping experience. | |||

| F4 | I like to follow AI technology developments and tend to watch live streaming hosted by AI-powered virtual idols. | |||

| Impulsive purchase intention of digital natives | G1 | During interactions, I am willing to make impulsive purchases of products recommended by AI-powered virtual idols. | Spears et al. [59] | |

| G2 | When AI-powered virtual idols recommend products to me, I am willing to temporarily consider whether the products are useful. | |||

| G3 | When AI-powered virtual idols recommend good products to me, I will recommend these products to my friends. | |||

Remark3: In this study, the measurement items for psychological distance were reverse-coded (i.e., 5 points converted to 1 point, 4 points to 2 points, and so forth), so that higher scores indicate greater psychological distance, while lower scores indicate closer psychological distance.

References

- Liu, F.; Wang, R. Fostering parasocial relationships with virtual influencers in the uncanny valley: Anthropomorphism, autonomy, and a multigroup comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 186, 115024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Virtual presence, real connections: Exploring the role of parasocial relationships in virtual idol fan community participation. Glob. Media China 2023, 8, 20594364231222976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertala, P.; López Pernas, S.; Vartiainen, H.; Saqr, M.; Tedre, M. Digital natives in the scientific literature: A topic modeling approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 152, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruthaya, A.; Nguyen, T.T.; Lokuge, S. The application of digital technology and the learning characteristics of Generation Z in higher education. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.05991. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Shao, B.; Yang, X.; Kang, W.; Fan, W. Avatars in live streaming commerce: The influence of anthropomorphism on consumers’ willingness to accept virtual live streamers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 156, 108216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Y. More realistic, more better? How anthropomorphic images of virtual influencers impact the purchase intentions of consumers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Tong, X. The effect of e-commerce virtual live streamer socialness on consumers’ experiential value: An empirical study based on Chinese e-commerce live streaming studios. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Kwong, S.C.M.; Bannasilp, A. Virtual idol marketing: Benefits, risks, and an integrated framework of the emerging marketing field. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.S.; Wang, J.Q.; Tu, S.H.; Liao, K.T.; Lin, C.L. Detecting latent topics and trends in IoT and e-commerce using BERTopic modeling. Internet Things 2025, 32, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Niu, W.; Lin, C.-L.; Fu, S.; Liao, K.-T.; Zhang, W. Loss of control: AI-based decision-making induces negative company evaluation. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Tang, Y. Avatar effect of AI-enabled virtual streamers on consumer purchase intention in e-commerce livestreaming. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 2999–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Shen, C.; Xiao, R. Entertainers between real and virtual—Investigating viewer interaction, engagement, and relationships with avatarized virtual livestreamers. Proc. ACM Int. Conf. Interact. Media Exp. 2025, 2025, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Toyib, J.S.; Paramita, W. An authentic human-like figure: The success keys of AI fashion influencer. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2380019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.Q.; Qu, H.J.; Li, P. The influence of virtual idol characteristics on consumers’ clothing purchase intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiousis, S. Interactivity: A concept explication. New Media Soc. 2002, 4, 355–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Hameed, Z.; Islam, T.; Pant, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Rather, R.A.; Kuzior, A. Avatars of influence: Understanding how virtual influencers trigger consumer engagement on online booking platforms. J. Retail Cons. Serv. 2024, 78, 103742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Xu, W.; Piao, Y.; Liu, Z. How collectivism and virtual idol characteristics influence purchase intentions: A dual mediation model of parasocial interaction and flow experience. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, F. The impact of virtual streamer anthropomorphism on consumer purchase intention: Cognitive trust as a mediator. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, K.Z.; Srivastava, G.; Mago, V. The homophily principle in social network analysis. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, G. Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Lin, Y.; Lou, X. Exploring purchase preferences of Chinese Gen Z fans for human and virtual idols on TikTok. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2023, 19, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.T. Mobile advertising to Digital Natives: Preferences on content, style, personalization, and functionality. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agárdi, I.; Alt, M.A. Do digital natives use mobile payment differently than digital immigrants? A comparative study between generation X and Z. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 24, 1463–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.G.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Komarova Loureiro, Y.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Shi, B. More proximal, more willing to purchase: The mechanism for variability in consumers’ purchase intention toward sincere vs. exciting brands. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Lee, J. The impact of online reviews on consumers’ purchase intentions: Examining the social influence of online reviews, group similarity, and self-construal. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1060–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Cao, C.; Xu, Q.; Ni, L.; Shao, X.; Shi, Y. How live streaming interactions and their visual stimuli affect users’ sustained engagement behaviour—A comparative experiment using live and virtual live streaming. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A. The role of psychological distance and construal level in explaining the effectiveness of human-like vs. cartoon-like virtual influencers. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 185, 114916. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, L. The effectiveness of virtual vs. human influencers in digital marketing: Based on perceived psychological distance and credibility. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 13–15 December 2024; Volume 46. [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi, N.; Neuhaus, V.; Vona, F.; Peperkorn, N.L.; Shiban, Y.; Voigt-Antons, J.N. Effect of external characteristics of a virtual human being during the use of a computer-assisted therapy tool. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Washington DC, USA, 29 June–4 July 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra, S.; Jonker, C.M.; Tielman, M.L. More similar values, more trust?—The effect of value similarity on trust in human-agent interaction. In Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, Virtual, 19–21 May 2021; Volume 2021, pp. 777–783. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleta, J.P.; Aasheim, C. Construal of social relationships in online consumer reviews. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2023, 63, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M. How technical features of virtual live shopping platforms affect purchase intention: Based on the theory of interactive media effects. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 180, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Yan, X.; Li, R. How to enhance consumers’ purchase intention in live commerce? An affordance perspective and the moderating role of age. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 67, 101438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Hu, P. Research on consumers’ online purchase decision based on psychological distance. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Education, Management, Arts, Economics and Social Science (ICEMAESS 2017), Sanya, China, 11–12 November 2017; pp. 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, S.; Zheng, C.; Cho, D.; Kim, Y.; Dong, Q. The impact of interpersonal interaction on purchase intention in livestreaming e-commerce: A moderated mediation model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Consumers’ purchase intentions in social commerce: The role of social psychological distance, perceived value, and perceived cognitive effort. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Mou, J.; Cohen, J.; Liu, Y.; Kurcz, K. Understanding consumer intentions toward cross-border m-commerce usage: A psychological distance and commitment-trust perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 39, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. Technology readiness index (TRI)—A multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 2, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Colby, C.L. An updated and streamlined technology readiness index: TRI 2.0. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.B.; Gaskin, J.; Twyman, N.; Hammer, B.; Roberts, T. Taking ‘fun and games’ seriously: Proposing the hedonic-motivation system adoption model (HMSAM). J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 14, 617–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Guo, C. Cross-level interaction mechanism for high growth among digital start–ups: An fsQCA analysis. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, A.; Sohaib, O. Technology readiness and cryptocurrency adoption: PLS-SEM and deep learning neural network analysis. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 21388–21394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Mouakket, S.; Sun, Y. Factors affecting customer readiness to trust chatbots in an online shopping context. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2024, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Mouakket, S.; Sun, Y. The role of chatbots’ human-like characteristics in online shopping. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 61, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Jin, C.; Wang, J. How an industrial internet platform empowers the digital transformation of SMEs: Theoretical mechanism and business model. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 27, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Li, M.; Qiu, H. Do customers exhibit engagement behaviors in AI environments? The role of psychological benefits and technology readiness. Tour. Manag. 2023, 97, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; So, K.K.F.; Sparks, B.A. Technology readiness and customer satisfaction with travel technologies: A cross-country investigation. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.S.C.; Hsieh, P.L. The influence of technology readiness on satisfaction and behavioral intentions toward self-service technologies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 1597–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Qiu, S. Trust in service robot: The role of appearance anthropomorphism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 28, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Mende, M.; Noble, S.M.; Hulland, J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Grewal, D.; Petersen, J.A. Domo arigato Mr. Roboto: Emergence of automated social presence in organizational frontlines and customers’ service experiences. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, H.; Sun, G.; Tao, J.; Lu, C.; Guo, C. Speculative culture and corporate high-quality development in China: Mediating effect of corporate innovation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Liu, J.Y.; Li, C.H.; Su, Y.S.; Zhou, J. The impact of switching intention of teachers’ online teaching in the COVID-19 era: The perspective of push-pull-mooring. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2025, 26, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golossenko, A.; Pillai, K.G.; Aroean, L. Seeing brands as humans: Development and validation of a brand anthropomorphism scale. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Massa, E.; Skandrani, H. YouTube vloggers’ popularity and influence: The roles of homophily, emotional attachment, and expertise. J. Retail Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102027. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, H.H.; Santeramo, M.J.; Traina, A. Correlates of trustworthiness for celebrities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1978, 6, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, N.; Singh, S.N. Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2004, 26, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).