“They Post, I Scroll, I Envy, I Buy”—How Social Media Influencers Shape Materialistic Values and Consumer Behavior Among Young Adults in Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

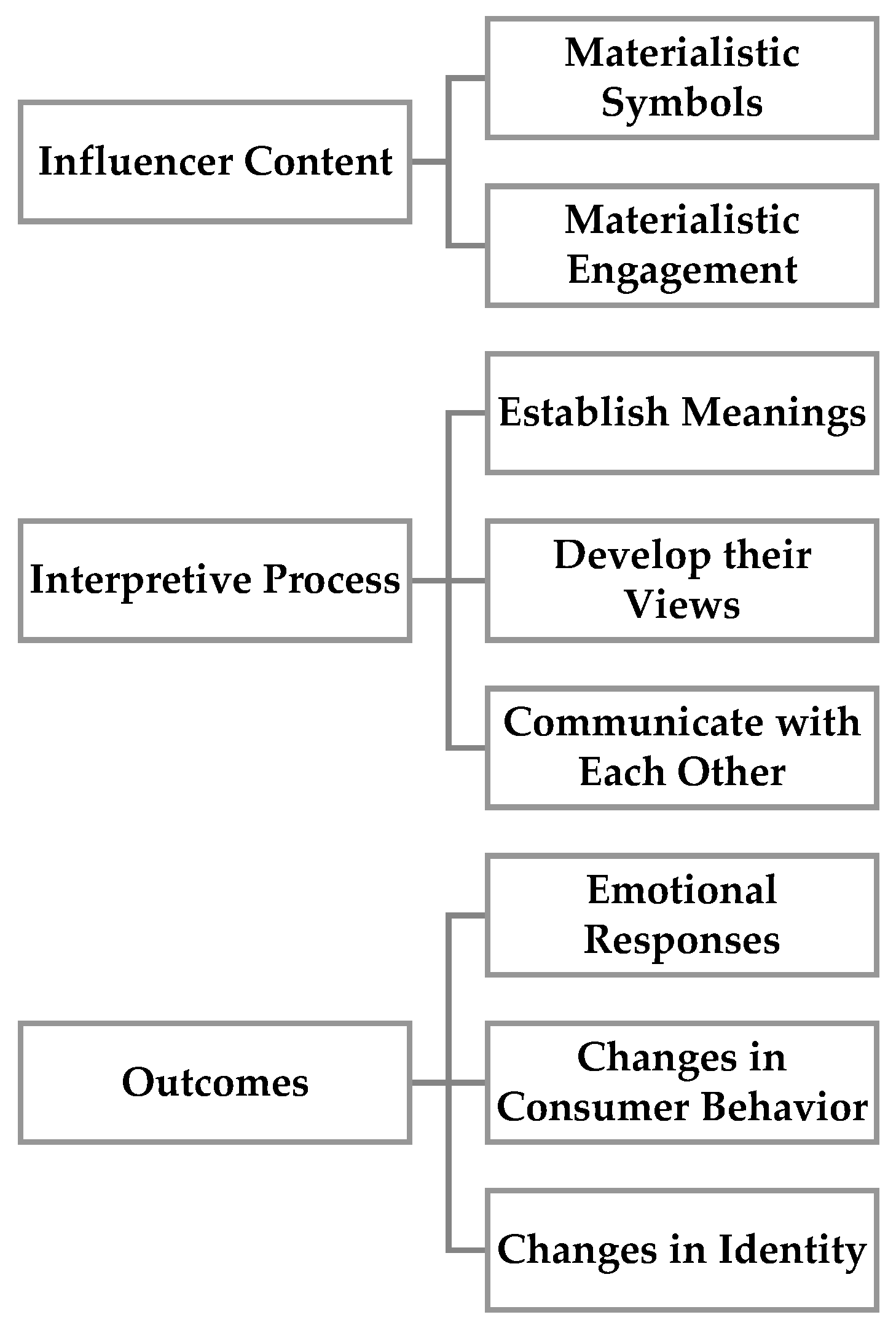

2.1. Theoretical Framework

- Meaning: The significance individuals ascribe to symbols and objects in their social interactions.

- Language: The primary tool through which symbols are communicated and meanings are shared.

- Interpretation: The process of making sense of interactions, which is central to understanding behaviors and relationships.

- What motivates followers to engage with social media influencers who promote materialistic content?

- What emotional effects do materialistic messages from influencers have on their followers?

- How does exposure to influencer-driven materialistic messages shape followers’ consumer behavior?

2.2. Materialism

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Population, Participant Selection, and Recruitment

3.2. Data Collection Process

- “Can you describe why you follow this particular influencer?”

- “How do you feel when you see them post about luxury items or branded products?”

- “Have you ever bought something because they recommended it? What was that experience like?”

- “Do you think their lifestyle influences how you see success or how you define yourself?”

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

- Familiarization—Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim and read multiple times for immersion in the data.

- Initial coding—Two rounds of inductive coding were conducted. Codes were assigned to meaningful segments of the text without imposing pre-set categories. NVivo 12 software was used to assist in managing and organizing data.

- Searching for categories—Similar codes were grouped into broader conceptual categories reflecting patterns in how participants talked about influencers, emotions, materialistic values, and self-perception.

- Theme development—Categories were refined into overarching themes based on recurring meanings and symbolic interpretations across participants. While the final themes corresponded with the research questions, they were not pre-imposed; rather, they reflected how participants themselves described their experiences, in line with the theoretical lens.

- Reviewing themes—Themes were reviewed to ensure they accurately captured the coded data and aligned with the full dataset. Disconfirming data and contrasting views were also considered during theme refinement.

- Defining and naming themes—Final themes were labeled in ways that captured the symbolic and emotional processes discussed by participants.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Participants’ Profile

4.2. Themes and Subthemes

4.2.1. Aspirational Symbolism

“When Liya (lifestyle influencer) posts her luxury hauls, I feel like she’s showing what’s possible when you’ve worked hard and earned your place in the world.”—P11

“He doesn’t just show off his latest cars; they show a story where success and happiness look like.”—P13

“Their possessions symbolize their achievements, which is inspiring in a way.”—P2

“She makes it look like there’s no stress in her life, just endless opportunities to enjoy everything the world has to offer.”—P11

“His life feels like a story where the usual struggles don’t exist, just joy and freedom—who wouldn’t want that?”—P6

“Her content make luxury feel closer, like it’s not just for the ultra-rich but for anyone who dares to dream big enough.”—P12

“Seeing her mix high-end and budget-friendly items makes it seem like living that lifestyle is actually manageable.”—P8

4.2.2. Social Validation

“Seeing him endorse the same workout routine I follow makes me feel like I’m on the right track.”—P1

“I don’t always agree with everything Chaw (Influencer) promotes, but when the choices line up with mine, it feels like a subtle nod of approval for my lifestyle.”—P12

“Sometimes, it’s not even about the product—it’s about seeing someone with a platform making the same choices as me, like using second-hand fashion.”—P15

“It’s funny how when he endorsed that local coffee brand I’ve been drinking for ages, my friends suddenly thought I had great taste!”—P7

“Seeing others talk about buying the same things she promotes makes me feel less guilty for wanting them—it’s like everyone agrees it’s worth it.”—P13

“Even though I can’t afford most of what they promote, seeing so many people desire it makes me feel like I’m not alone in wanting more.”—P3

“There is this vibe (on the group) that buying these products is what everyone should aim for.”—P5

“I can’t help but wonder if I’m failing because I can’t afford those things.”—P2

“Her life makes me think about what success looks like—do I need all that stuff to feel like I’ve made it?”—P14

“The content makes me realize how much I equate possessions with success, and it’s a tough cycle to break.”—P6

4.2.3. Ambivalence in Emotional Responses

“I love seeing all the amazing things they have, but it’s hard not to feel like I’m missing out.”—P10

“It’s great to see what’s possible, but it’s tough when you know you’ll probably never have it.”—P3

“Some days I admire them, and other days it’s hard not to feel a little jealous.”—P2

“It’s crazy how scrolling through their feeds makes luxury seem like it’s no longer a privilege but an expectation.”—P8

“It’s obvious they’re paid to promote these brands, but it still makes you question if your life is lacking because you can’t keep up.”—P4

“It still creates this false sense that everyone can afford it.”—P1

“It pushes me to set bigger goals—if she can have that lifestyle, why can’t I?”—P11

“Over time, I realized it’s all staged, and now I just scroll past without much thought.”—P6

“I watch her content for fun now, like a reality show—I don’t take it seriously or feel pressured by it.”—P3

“I’ve stopped feeling anything when I see his profile—it’s just part of my feed, like ads or memes.”—P1

“It’s entertaining to watch, but I don’t let it shape my thoughts or goals anymore.”—P12

“I’ve learned to enjoy the content without feeling the need to compare—it’s their reality, not mine.”—P15

4.2.4. Envy and Dissatisfaction

“I can’t ignore the envy, but it fuels my desire to work toward my version of success.”—P9

“I see her traveling first-class and wearing designer clothes, and it makes me wonder if I’ll ever get to that point.”—P4

“It also makes me think, ‘If he can do it, why can’t I?’”—P13

“She’s always posting about her lavish lifestyle, and while it’s frustrating to see, it does make me think about how I can improve my own situation.”—P2

“It’s clear his life is in a completely different league, but that doesn’t stop me from wishing I could afford just one of the things he casually shows off.”—P10

“I know it’s not realistic for me to own what they have, but sometimes it feels unfair seeing how easily they seem to have it all.”—P8

“I’d love to shop like them, but my bank account says, ‘Just window-shop, buddy.’”—P1

“Their lifestyle isn’t realistic for me, so I just enjoy the content without taking it too seriously.”—P14

“I treat their posts like a movie—it’s entertaining, but I know it’s not real life.”—P3

“I’ve stopped comparing myself because I realized she has a whole team making them look that good.”—P5

4.2.5. Shifts in Purchasing Decisions

“I saw her post about the bag, and within minutes, I was checking out online—I didn’t even think if I really needed it.”—P6

“I love the rush of getting something they recommend, but the excitement fades so quickly, it’s almost disappointing.”—P7

“It’s that fear of missing out—they make it seem like the product is so exclusive that you can’t wait to buy it.”—P12

“Honestly, I bought the gadget he was raving about, but now it’s just sitting in a drawer—completely unnecessary.”—P11

“I gave in to the pressure and bought that designer perfume she posted, but now I’m stuck wondering if it was worth the price.”—P10

“Her posts made me realize that spending on quality skincare is worth it in the long run—I see it as self-care now.”—P2

“Their posts changed how I shop—I focus on long-term value now, even if it means fewer but better items.”—P9

“He convinced me that a premium coffee machine is an investment in my daily happiness—it’s hard to argue with that logic.”—P15

“I saw her using that face serum and thought, ‘Why not?’”—P12

“I gave the fitness plan she endorsed a shot, hoping for quick results, but it wasn’t as effective as promised.”—P2

“It looked so easy to use in his video, I figured I might as well see if it works for me.”—P6

“Her enthusiasm about the product was contagious—it made me curious enough to try it out.”—P3

4.2.6. Influence on Self-Concept and Identity

“Buying the same brands they use makes me feel like I’m part of the in-crowd, even if it’s just online.”—P1

“Seeing them use it first makes it easier to justify spending on something trendy—it feels like I’m keeping up.”—P11

“Sometimes, it’s less about the product and more about feeling like I’m presenting myself the ‘right’ way.”—P14

“Using these products gives me confidence, like I’m living up to the image I want to have.”—P7

“It’s not just about owning the item—it’s about what it says about me when people see me with it.”—P12

“Their content helps me figure out what feels right for me and what kind of image I want to create.”—P15

“It’s confusing because I used to have my own style, but now I just look to them for what’s ‘in.’”—P12

“I have bought things they (lifestyle influencers) recommended, but later I realize it’s not even me—it’s just what they made me think I needed.”—P10

“Their posts make me want things I wouldn’t have even considered if I hadn’t seen them promote it.”—P3

”I don’t know if my preferences are evolving naturally or if I’m just being influenced by what they post.”—P4

“There are moments when I feel like I’m losing my individuality in trying to keep up with them.”—P8

5. Conclusions

6. Contributions and Implications

7. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Coding Comparison Between First and Second Coders

| Transcript ID | Initial Code (First Coder) | Initial Code (Second Coder) | Resolution Outcome |

| P07 | Viewed influencers as a pathway to success | Influencers seen as role models for success | Grouped into “Trust in Influencer Recommendations” |

| P05 | Purchased skincare impulsively after watching haul video | Made impulsive decision due to product unboxing | Refined as “Erosion of Authentic Self” |

| P11 | Felt frustrated after buying expensive bag | Experienced regret after luxury fashion purchase | Categorized as “Impulse Purchases” |

| P06 | Saw luxury as emotional escape | Linked luxury items with emotional comfort | Grouped into “Trust in Influencer Recommendations” |

| P11 | Used influencer product to feel validated | Sought validation through influencer use | Placed under “Emotional Responses” |

| P07 | Admired influencer lifestyle and wanted to replicate it | Desired lifestyle replication of influencers | Placed under “Emotional Responses” |

| P06 | Said purchase brought only temporary happiness | Realized purchase did not meet emotional need | Included in “Identity Projection” |

| P01 | Regretted overspending on beauty products | Later questioned necessity of beauty items | Grouped into “Trust in Influencer Recommendations” |

| P06 | Felt guilt post-purchase of trendy clothes | Described guilt after fast fashion purchase | Categorized as “Impulse Purchases” |

| P11 | Saw branded items as shortcut to social status | Used expensive items to seek attention | Grouped under “Aspirational Symbolism” |

| P07 | Said influencer content reduced self-worth | Influencer feed lowered self-perception | Assigned to “Social Comparison” |

| P14 | Purchased item for online approval | Bought item for online recognition | Added to “Rationalized Acceptance” |

| P15 | Copied influencer makeup routine to fit in | Followed influencer look to be accepted | Finalized under “Distancing and Self-Regulation” |

| P03 | Noticed change in self-image after content binge | Felt less authentic after influencer binge | Assigned to “Social Comparison” |

| P12 | Said influencers make me feel behind in life | Said content made them feel left out | Included in “Identity Projection” |

| P07 | Felt anxious after browsing luxury travel posts | Felt unease after comparing lives online | Placed under “Emotional Responses” |

| P14 | Used product in hopes of being noticed | Hoped product would raise social status | Assigned to “Social Comparison” |

| P15 | Said I no longer know what I really want | Unsure of personal style after influence | Included in “Identity Projection” |

| P13 | Felt pressure to look rich on social media | Desire to match wealthy image online | Added to “Rationalized Acceptance” |

| P12 | Bought things without need after influencer ad | Responded to ad with unnecessary buy | Assigned to “Social Comparison” |

| P03 | Believed influencer product was life-changing | Thought product would fix self-image | Refined as “Erosion of Authentic Self” |

| P04 | Said everyone owns this, I should too | Purchased under peer pressure | Grouped into “Trust in Influencer Recommendations” |

| P03 | Identified with influencer story, not product | Emotionally related to influencer’s journey | Assigned to “Social Comparison” |

| P13 | Recognized ideal life shown was edited | Aware content was curated, not real | Grouped under “Aspirational Symbolism” |

| P10 | Tried to control spending but failed often | Struggled to stick to budget after content | Finalized under “Distancing and Self-Regulation” |

References

- Lüders, A.; Dinkelberg, A.; Quayle, M. Becoming “Us” in Digital Spaces: How Online Users Creatively and Strategically Exploit Social Media Affordances to Build up Social Identity. Acta Psychol. 2022, 228, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Cho, S.Y.; Jia, X.; Sun, R.; Tsai, W.S. Antecedents and Outcomes of Generation Z Consumers’ Contrastive and Assimilative Upward Comparisons with Social Media Influencers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.C.T.; Lee, Y. “I Want to Be as Trendy as Influencers”—How “Fear of Missing out” Leads to Buying Intention for Products Endorsed by Social Media Influencers. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 16, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffner, C.A.; Bond, B.J. Parasocial Relationships, Social Media, & Well-Being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, L.; Rasiah, R.; Waheed, H.; Pahlevan Sharif, S. Excessive Use of Social Networking Sites and Financial Well-Being among Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Online Compulsive Buying. Young Consum. 2021, 22, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F. Effective Influencer Marketing: A Social Identity Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, K.A.; Wel, C.A.C.; Hamid, S.N.A. Trash Talk: How Malaysian Zero Waste Influencers Shape Sustainable Habits. PaperASIA 2025, 41, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. The Material Values Scale: Measurement Properties and Development of a Short Form. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R.A.; Baker, G.A.; Truluck, C.S. Celebrity Worship, Materialism, Compulsive Buying, and the Empty Self. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarka, P.; Harnish, R.J.; Babaev, J. From Materialism to Hedonistic Shopping Values and Compulsive Buying: A Mediation Model Examining Gender Differences. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 786–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnik-Durose, M.E. Materialism and Well-Being Revisited: The Impact of Personality. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandelaere, M. Materialism and Well-Being: The Role of Consumption. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Does Socioeconomic Status Matter? Materialism and Self-Esteem: Longitudinal Evidence from China. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hawk, S.T.; Opree, S.J.; de Vries, D.A.; Branje, S. “Me”, “We”, and Materialism: Associations between Contingent Self-Worth and Materialistic Values across Cultures. J. Psychol. 2020, 154, 386–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.M.M.I. Personal Values and Consumers’ Ethical Beliefs: The Mediating Roles of Moral Identity and Machiavellianism. J. Macromark. 2020, 40, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić, A.; Uzelac, M.; Previšić, A. The Power of Materialism among Young Adults: Exploring the Effects of Values on Impulsiveness and Responsible Financial Behavior. Young Consum. 2021, 22, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, K.A.; Wel, C.A.; Ab Hamid, S.N. Examining Loyalty of Social Media Influencers—The Effects of Self-Disclosure and Credibility. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2024, 18, 358–379. [Google Scholar]

- Azhar, K.A.; Wel, C.A.C.; Hamid, S.N.A. The Test of Time: A Longitudinal Study of Parasocial Relationships with Social Media Influencers. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2025, 8, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L.J.; Chaplin, L.N.; Lowrey, T.M. Psychological Causes, Correlates, and Consequences of Materialism. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 5, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenze, T. Value Change in the Western World: The Rise of Materialism, Post-Materialism or Both? Int. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 31, 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.C.; Howell, A.J. Psychological Flexibility, Non-Attachment, and Materialism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 202, 111965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leban, M.; Thomsen, T.U.; von Wallpach, S.; Voyer, B.G. Constructing Personas: How High-Net-Worth Social Media Influencers Reconcile Ethicality and Living a Luxury Lifestyle. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, N.F.M.; Iqbal, N.; Shaari, A.H. The Role of False Self-Presentation and Social Comparison in Excessive Social Media Use. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Cheung, M.L.; Soh, P.C.-H.; Teoh, C.W. Social Media Influencer Marketing: The Moderating Role of Materialism. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2021, 34, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Sudarshan, S.; Sussman, K.L.; Bright, L.F.; Eastin, M.S. Why Are Consumers Following Social Media Influencers on Instagram? Exploration of Consumers’ Motives for Following Influencers and the Role of Materialism. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Kim, H.K. Fancying the New Rich and Famous? Explicating the Roles of Influencer Content, Credibility, and Parental Mediation in Adolescents’ Parasocial Relationship, Materialism, and Purchase Intentions. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalol, A.A.; Islam, R.; Humayun, K.S.M. Social Media Usage and Behaviour among Generation Y and Z in Malaysia. Middle East J. Manag. 2021, 8, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Jan, M.T. The Influence of Collectivism on Consumer Responses to Green Behavior. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 6, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.-L.; Brown, S. Social Construction of Identities. In Rethinking College Student Development Theory Using Critical Frameworks; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hannem, S. Symbolic Interactionism, Social Structure, and Social Change: Historical Debates and Contemporary Challenges. In The Routledge International Handbook of Interactionism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. Mead and Blumer: The Convergent Methodological Perspectives of Social Behaviorism and Symbolic Interactionism. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1980, 45, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, S. From Mead to a Structural Symbolic Interactionism and Beyond. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2008, 34, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, A.; Eckhardt, G.M. The Broadening Boundaries of Materialism. Mark. Theory 2021, 21, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L.; Dawson, S. A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.J.C. Materialism. J. Philos. 1963, 60, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, C.N.; Hanan, J.S.; Nail, T. What Is New Materialism? Angelaki 2019, 24, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, Y.; Sung, Y.; Chechelnytska, I. What Makes Materialistic Consumers More Ethical? Self-Benefit vs. Other-Benefit Appeals. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maison, D.; Adamczyk, D. The Relations between Materialism, Consumer Decisions and Advertising Perception. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 176, 2526–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabahang, R.; Aruguete, M.S.; Shim, H.; Koushali, F.G.; Zsila, Á. Desire To Be a Social Media Influencer: Desire for Fame, Materialism, Perceived Deprivation and Preference for Immediate Gratification as Potential Determinants. Media Watch 2022, 13, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deori, M.; Nisha, F.; Verma, N.K.; Verma, M.K. Consumption Patterns of Female Lifestyle Influencers During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Thematic Sentiment Analysis Based on the Comments of Selected YouTube Videos. J. Creat. Commun. 2023, 09732586231168489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To Saturate or Not to Saturate? Questioning Data Saturation as a Useful Concept for Thematic Analysis and Sample-Size Rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coded Name | Age | Gender | Favorite Lifestyle Influencer | Geographic Area | Race | Total Interview Time (Minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 24 | Female | Jessica Chaw | Urban | Chinese | 55 |

| P2 | 21 | Male | Syahmi Sazli | Urban | Malay | 48 |

| P3 | 19 | Female | Liyamaisarah | Suburban | Malay | 62 |

| P4 | 20 | Female | Betty Rahmad | Suburban | Malay | 50 |

| P5 | 19 | Male | Yana Strawberry | Rural | Malay | 40 |

| P6 | 22 | Female | Christinna Kuan | Urban | Chinese | 65 |

| P7 | 25 | Female | Eyna Nan | Suburban | Malay | 47 |

| P8 | 21 | Female | Jane Chuck | Urban | Chinese | 58 |

| P9 | 23 | Male | Danny Luxe | Urban | Indian | 52 |

| P10 | 21 | Female | Qiu Wen | Urban | Chinese | 59 |

| P11 | 20 | Female | Mia Chai | Suburban | Chinese | 45 |

| P12 | 20 | Male | Aedy Ashraf | Urban | Malay | 66 |

| P13 | 24 | Female | Huisun Pang | Urban | Chinese | 54 |

| P14 | 19 | Female | Sara Aspire | Urban | Malay | 57 |

| P15 | 21 | Female | Amy Travelogue | Suburban | Indian | 53 |

| Research Question | Theme | Subtheme | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| What motivates followers to engage with social media influencers who promote materialistic content? | Aspirational Symbolism | Materialism as a Benchmark for Success | Influencers’ luxury possessions are seen as indicators of achievement. |

| Emotional Resonance with Freedom and Abundance | Influencers evoke admiration for a life perceived as unrestricted and fulfilling. | ||

| Perceived Accessibility of Luxury | Influencers make luxury seem attainable, bridging fantasy and reality. | ||

| Social Validation | Validation of Personal Choices | Followers feel validated when influencers endorse relatable products or lifestyles. | |

| Reinforcement of Social Connection | Engagement with influencers helps followers feel part of a social trend. | ||

| Comparison and Self-Reflection | Followers compare themselves to influencers’ idealized standards, influencing self-perception. | ||

| What emotional effects do materialistic messages from influencers have on their followers? | Ambivalence in Emotional Responses | Emotional Polarization | Followers experience conflicting emotions of admiration and envy. |

| Normalization of Materialism | Repeated exposure to luxury makes materialism feel essential yet unattainable. | ||

| Desensitization to Content | Some followers treat content as entertainment with minimal emotional impact. | ||

| Envy and Dissatisfaction | Triggered Aspirations | Feelings of envy motivate followers to work toward personal goals. | |

| Acknowledged Disparity | Recognizing gaps between their lives and influencers’ leads to dissatisfaction. | ||

| Rationalized Acceptance | Followers rationalize influencers’ lifestyles as unattainable and focus on entertainment value. | ||

| How does exposure to influencer-driven materialistic messages shape followers’ consumer behavior? | Shifts in Purchasing Decisions | Impulse Purchases | Followers make spontaneous purchases inspired by influencers. |

| Strategic Investments | Followers view high-value items as aspirational investments. | ||

| Trial and Error with Promoted Products | Followers experiment with influencer-promoted items with varying satisfaction. | ||

| Influence on Self-Concept and Identity | Reinforcement of Social Identity | Followers align with influencer-endorsed brands to project a societal identity. | |

| Identity Through Consumption | Promoted possessions are seen as extensions of personality and self-expression. | ||

| Erosion of Authentic Self | Over-reliance on influencers creates tension between personal and external preferences. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azhar, K.A.; Wel, C.A.C.; Ab Hamid, S.N. “They Post, I Scroll, I Envy, I Buy”—How Social Media Influencers Shape Materialistic Values and Consumer Behavior Among Young Adults in Malaysia. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030172

Azhar KA, Wel CAC, Ab Hamid SN. “They Post, I Scroll, I Envy, I Buy”—How Social Media Influencers Shape Materialistic Values and Consumer Behavior Among Young Adults in Malaysia. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030172

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzhar, Kaukab Abid, Che Aniza Che Wel, and Siti Ngayesah Ab Hamid. 2025. "“They Post, I Scroll, I Envy, I Buy”—How Social Media Influencers Shape Materialistic Values and Consumer Behavior Among Young Adults in Malaysia" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030172

APA StyleAzhar, K. A., Wel, C. A. C., & Ab Hamid, S. N. (2025). “They Post, I Scroll, I Envy, I Buy”—How Social Media Influencers Shape Materialistic Values and Consumer Behavior Among Young Adults in Malaysia. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030172