Consumer Evaluation of Virtual vs. Human Influencers via Source Credibility, Perceived Social Similarity, and Consumption Motivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influencer Attributes and Purchase Intention

2.2. Follower–Influencer Identification and Perceived Social Similarity

2.3. Hedonic vs. Utilitarian Consumption Motivation

2.4. Brand Familiarity, Prior Brand Attitude, and Influencer Attributes

2.5. Influencer Type and Gender–Product Matchup

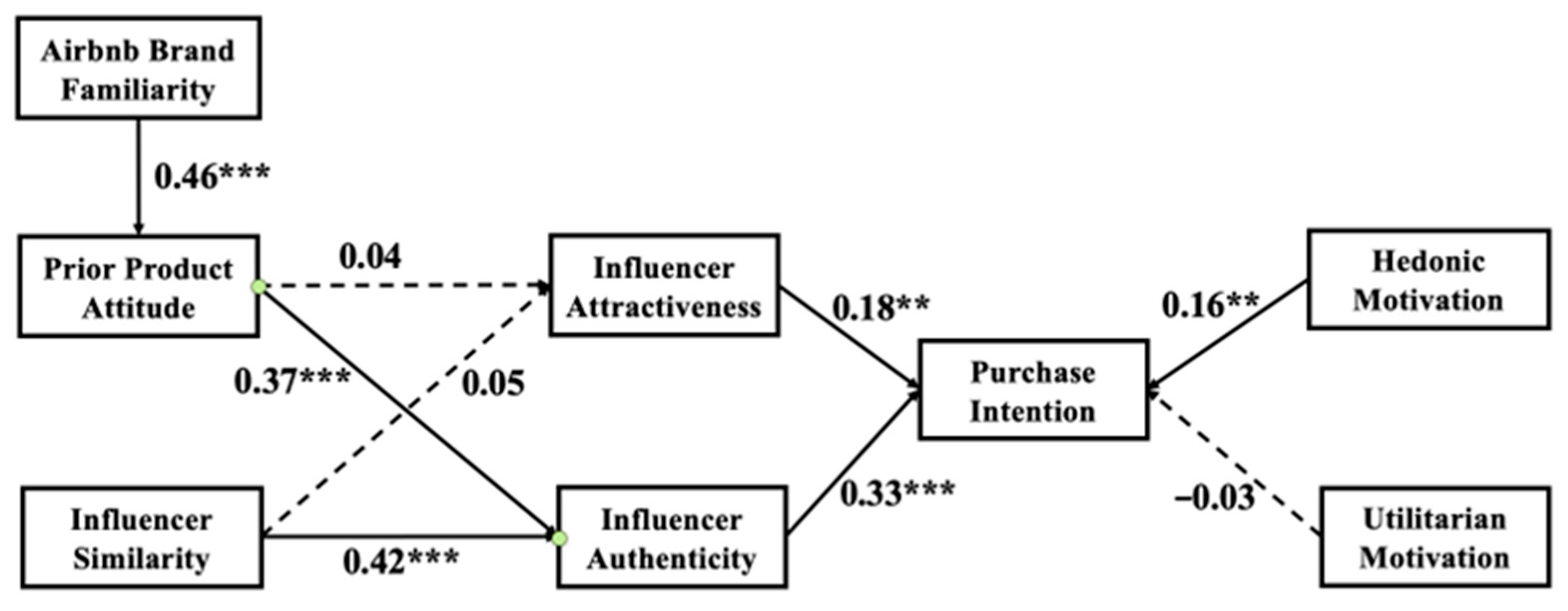

2.6. Proposed Conceptual Model

3. Method

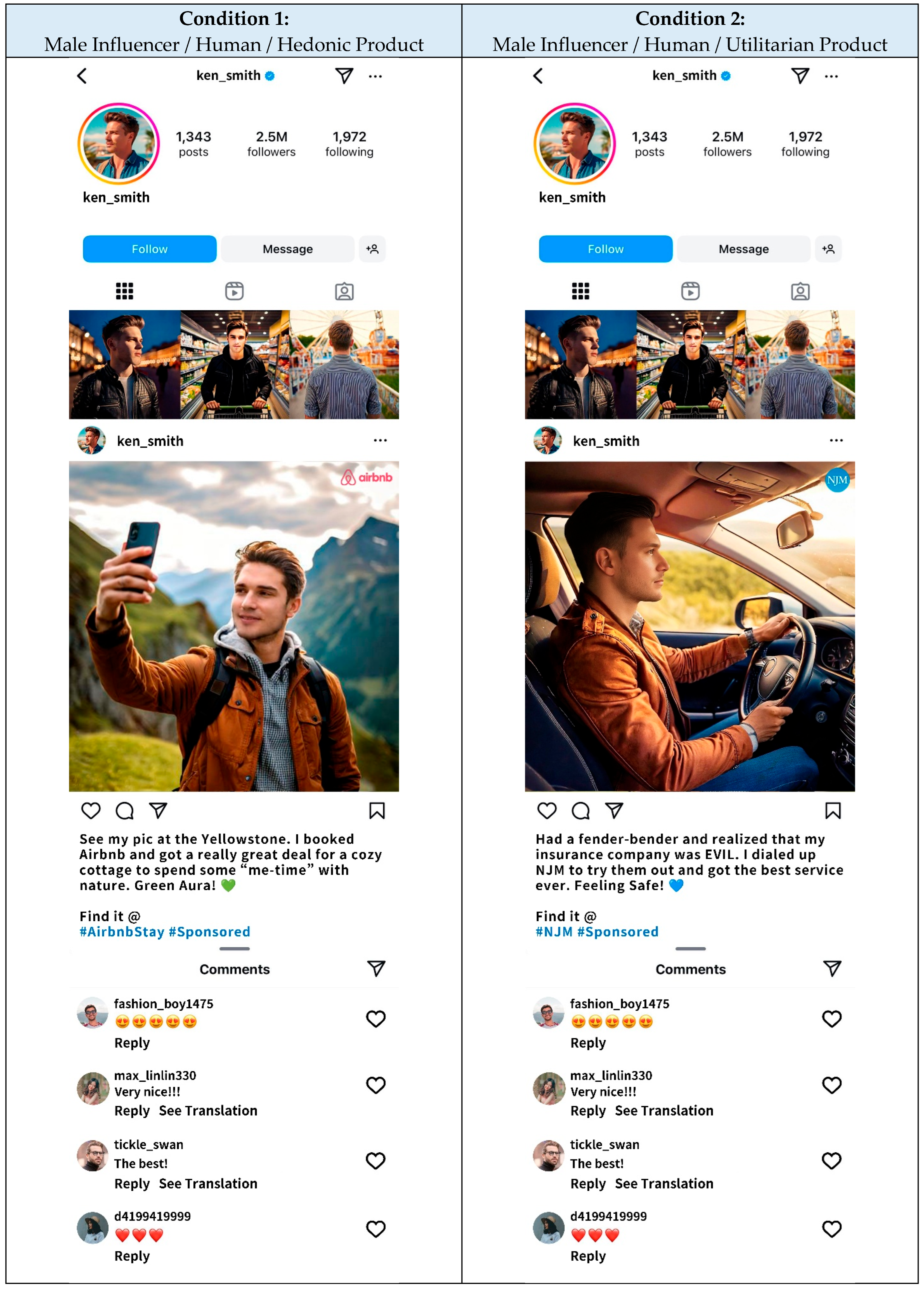

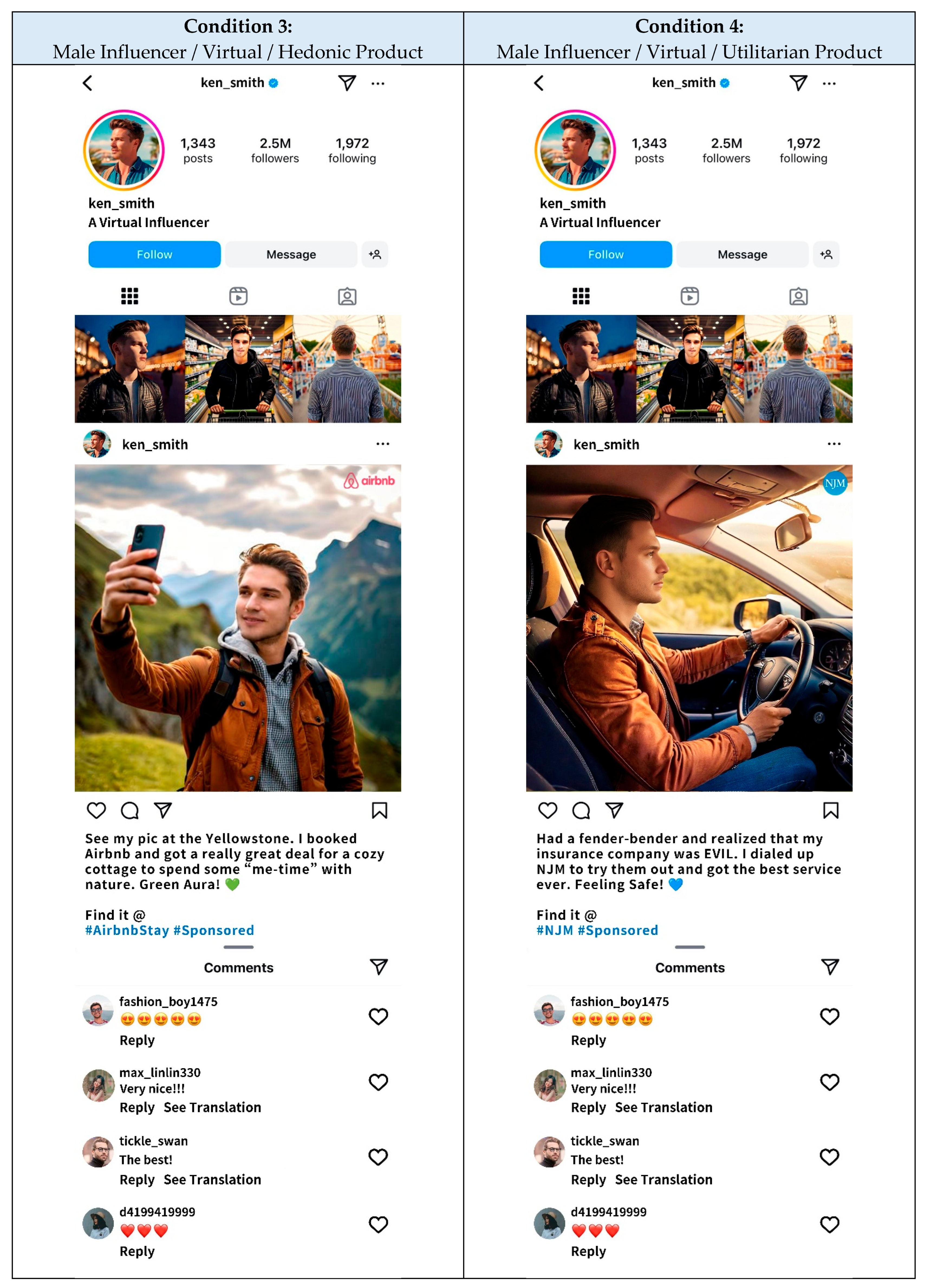

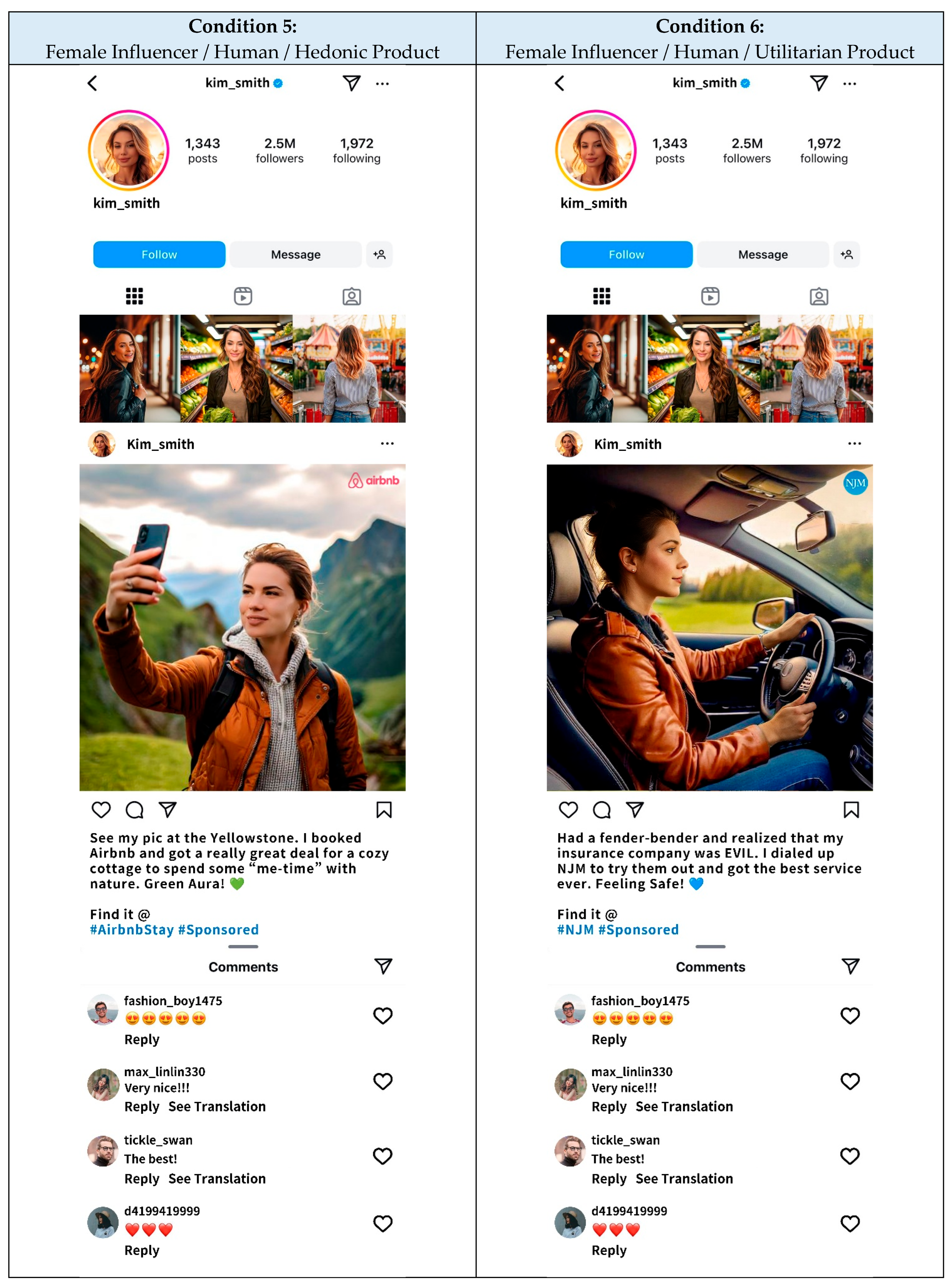

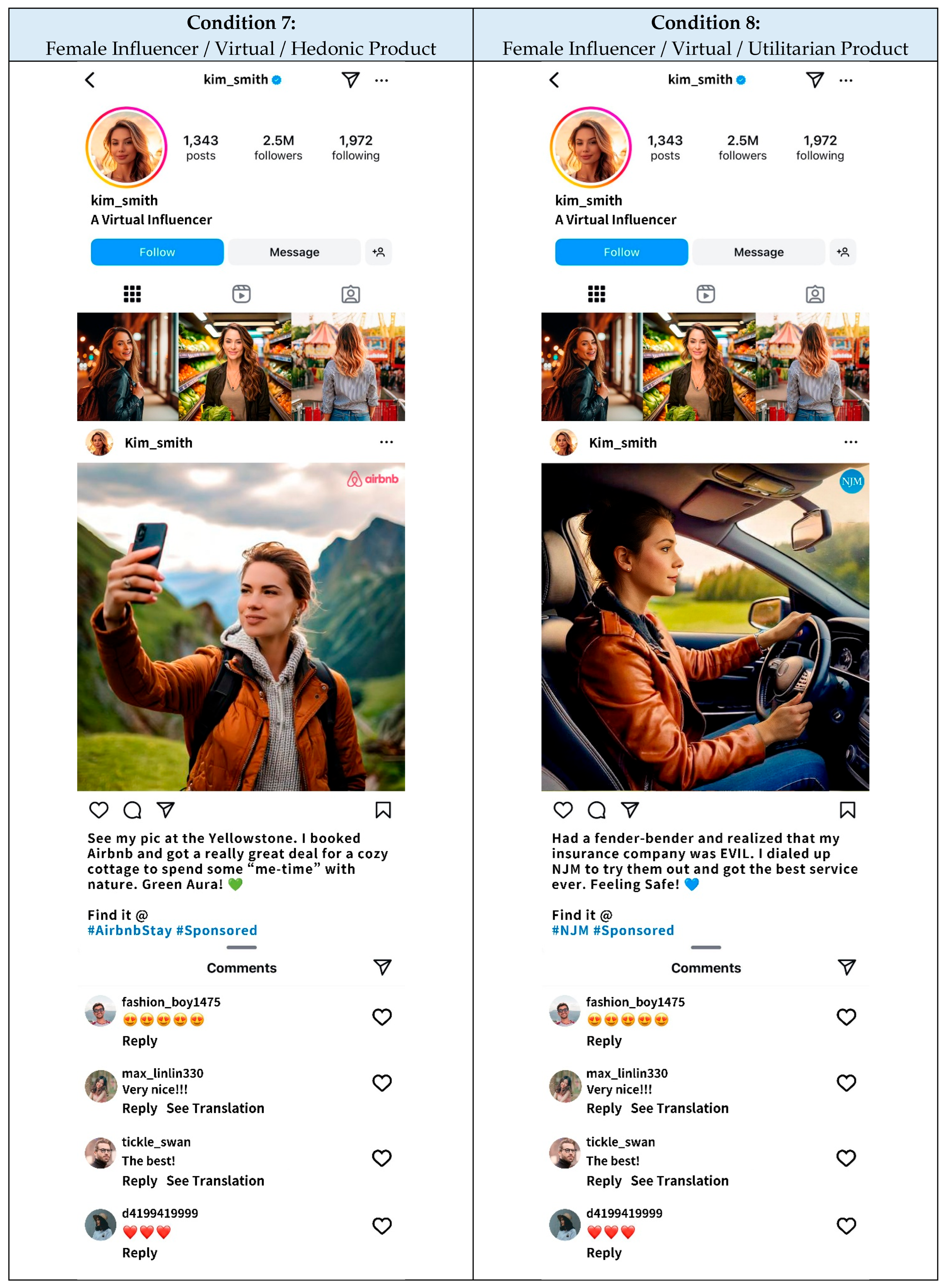

3.1. Stimulus

3.2. Manipulation Checks

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Measures

4. Result

Testing Results for Hypotheses and Research Questions

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Study Conditions

References

- Abidin, C. Communicative Intimacies: Influencers and Perceived Interconnectedness. Ada J. Gend. New Media Technol. 2015, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influencer Marketing Hub Influencer Marketing Benchmark Report 2025. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- KOLR. How to Capture the Attention of Gen Z Through Influencer Marketing: 4 Essential Factors. 2023. Available online: https://www.kolr.ai/en/trends/how-to-approach-influencer-marketing-for-gen-z-4-key-points-to-capture-the-attention-of-gen-z/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Hwang, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Srinivasan, K. Should Your Brand Hire a Virtual Influencer? Available online: https://hbr.org/2024/05/should-your-brand-hire-a-virtual-influencer (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Lou, C.; Kiew, S.T.J.; Chen, T.; Lee, T.Y.M.; Ong, J.E.C.; Phua, Z. Authentically Fake? How Consumers Respond to the Influence of Virtual Influencers. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lei, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, H. Can You Sense without Being Human? Comparing Virtual and Human Influencers Endorsement Effectiveness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lee, Y.-H. Virtually Authentic: Examining the Match-up Hypothesis between Human vs Virtual Influencers and Product Types. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 33, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A.; Müller, K. Consumers’ Responses to Virtual Influencers as Advertising Endorsers: Novel and Effective or Uncanny and Deceiving? J. Advert. 2023, 52, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M. Human versus Virtual Influences, a Comparative Study. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 173, 114493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K. Close Encounters of the AI Kind: Use of AI Influencers as Brand Endorsers. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Zhou, M. Don’t Like Them but Take What They Said: The Effectiveness of Virtual Influencers in Public Service Announcements. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2269–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Y.A.; Muqaddam, A.; Liang, Y. The Role of Flow in Dissemination of Recommendations for Hedonic Products in User-Generated Review Websites. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lin, C.A. The Effects of Product Type, Product Involvement and Technology Fluidity on Flow and Newsfeed Advertising. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2023, 67, 714–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Han, J.Y.; Seo, Y. Effects of Facebook Comments on Attitude Toward Vaccines: The Roles of Perceived Distributions of Public Opinion and Perceived Vaccine Efficacy. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Baek, T.H. Are Virtual Influencers Friends or Foes? Uncovering the Perceived Creepiness and Authenticity of Virtual Influencers in Social Media Marketing in the United States. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 5042–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, A.; Han, J.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y. “I Felt a Little Crazy Following a ‘Doll’”: Investigating Real Influence of Virtual Influencers on Their Followers. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A.; Crowe, J.; Pierre, L.; Lee, Y. Effects of Parasocial Interaction with an Instafamous Influencer on Brand Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. J. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 10, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The Influence of Source Credibility on Communication Effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986; Volume 19, pp. 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.-H.; Chen, C.-F. How Do Influencers’ Characteristics Affect Followers’ Stickiness and Well-Being in the Social Media Context? J. Serv. Mark. 2023, 37, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Teven, J.J. Goodwill: A Reexamination of the Construct and Its Measurement. Commun. Monogr. 1999, 66, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.-W.C.; Kim, Y.-K. The Mechanism by Which Social Media Influencers Persuade Consumers: The Role of Consumers’ Desire to Mimic. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Lou, C. How Social Media Influencers Foster Relationships with Followers: The Roles of Source Credibility and Fairness in Parasocial Relationship and Product Interest. J. Interact. Advert. 2020, 20, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. The Power of Virtual Influencers: Impact on Consumer Behaviour and Attitudes in the Age of AI. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. Societal Perceptions and Acceptance of Virtual Humans: Trust and Ethics across Different Contexts. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.J.; Ahn, S.J. A Systematic Review of Virtual Influencers: Similarities and Differences between Human and Virtual Influencers in Interactive Advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonopoulos, V.; Lee, J.; Mathies, C. Authentic Isn’t Always Best: When Inauthentic Social Media Influencers Induce Positive Consumer Purchase Intention through Inspiration. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Eastin, M.S. Perceived Authenticity of Social Media Influencers: Scale Development and Validation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 822–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Cohen, O.; Segev, S.; Liu, Y. The Effect of Non-Celebrity Influencers’ Perceived Authenticity on Social Media Advertising Outcomes. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KOL Radar Following Influencers Is Like Spending Time with Friends! Master These 4 Key Points of Gen Z Influencer Marketing to Capture Their Purchasing Power. Available online: https://www.bnext.com.tw/article/69924/generation-z-consume-prime (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Liu, R. Why Do Chinese People Consume Video Game Live Streaming on the Platform? An Exploratory Study Connecting Affordance-Based Gratifications, User Identification, and User Engagement. Telemat. Inform. 2024, 86, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-X.; Lee, Y.-C. Straight into Your Heart: The Effect of Live-Streaming E-Commerce on Consumer Engagement. NTU Manag. Rev. 2022, 32, 153–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Kim, J. (Jay) Starring in Your Own Snapchat Advertisement: Influence of Self-Brand Congruity, Self-Referencing and Perceived Humor on Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention of Advertised Brands. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Tajfel, H. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. Psychol. Intergroup Relat. 1986, 5, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. Organ. Identity Read. 1979, 56, 9780203505984-16. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.A.; Xu, X. Effectiveness of Online Consumer Reviews: The Influence of Valence, Reviewer Ethnicity, Social Distance and Source Trustworthiness. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A.; Park, S.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y. Exploring Transcultural Communication via Perceived Social Distance and Intergroup Acceptance toward K-Pop and Asian Culture. Howard J. Commun. 2024, 35, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A.; Pierre, L. The Role of Social Identity and Spokesperson in Influencing Consumer Involvement, Information Seeking, and Purchase Intention. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2023, 44, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Wang, R.; Chan-Olmsted, S. Factors Affecting YouTube Influencer Marketing Credibility: A Heuristic-Systematic Model. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2018, 15, 188–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. How Does a Celebrity Make Fans Happy? Interaction between Celebrities and Fans in the Social Media Context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillon, B.J.; Mueller, S.M.; Kowalczyk, C.M.; Jones, D.N. Understanding the Relationships between Social Media Influencers and Their Followers: The Moderating Role of Closeness. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Consumer Attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic Consumption: Emerging Concepts, Methods and Propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Aniceto, I.; Bairrada, C.M.; Silva, P. Personal Values and Impulse Buying: The Mediating Role of Hedonic Shopping Motivations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, C.; Adıgüzel, F. Shopping Enjoyment to the Extreme: Hedonic Shopping Motivations and Compulsive Buying in Developed and Emerging Markets. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, A.A.; Chakraborty, S. Adoption, Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment of over-the-Top Platforms: An Integrated Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to Charity as Purchase Incentives: How Well They Work May Depend on What You Are Trying to Sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Sustainable Apparel Consumption: Personal Norms, CSR Expectations, and Hedonic vs. Utilitarian Shopping Value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Filieri, R.; Acikgoz, F.; Zollo, L.; Rialti, R. The Effect of Utilitarian and Hedonic Motivations on Mobile Shopping Outcomes. A cross-cultural analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahnila, S.; Warsta, J. Online Shopping Viewed from a Habit and Value Perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2010, 29, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, R.U.; Hou, F.; Ahmad, W. Understanding Continuance Intention to Use Social Media in China: The Roles of Personality Drivers, Hedonic Value, and Utilitarian Value. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha-Ortiz, J.A.; Feliberty-Lugo, V.; Santos-Corrada, M.; Lopez, E.; Dones, V. Hedonic and Utilitarian Gratifications to the Use of TikTok by Generation Z and the Parasocial Relationships with Influencers as a Mediating Force to Purchase Intention. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-H.; Chen, C.-F.; Tai, Y.-W. Exploring the Roles of Vlogger Characteristics and Video Attributes on Followers’ Value Perceptions and Behavioral Intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, J.M.; Xiong, V.Y.; Septianto, F.; Seo, Y. David and Goliath: When and Why Micro-Influencers Are More Persuasive Than Mega-Influencers. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, H. User Acceptance of Hedonic Information Systems. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Hsu, P.-Y.; Chen, J.; Shiau, W.-L.; Xu, N. Utilitarian and/or Hedonic Shopping—Consumer Motivation to Purchase in Smart Stores. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.J.; Allen, C.T. Competitive Interference Effects in Consumer Memory for Advertising: The Role of Brand Familiarity. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Kim, C.; Zhou, L. Brand Familiarity and Confidence as Determinants of Purchase Intention: An Empirical Test in a Multiple Brand Context. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 37, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, E.S.; Jung, W.S. Brand Familiarity as a Moderating Factor in the Ad and Brand Attitude Relationship and Advertising Appeals. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira, W.J.; Santiago, J.K.; Santini, F.d.O.; Pinto, D.C. Impact of Brand Familiarity on Attitude Formation: Insights and Generalizations from a Meta-Analysis. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Basu, K. Humor in Advertising: The Moderating Role of Prior Brand Evaluation. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-Y.; Lin, C.A. Predicting the Effects of eWOM and Online Brand Messaging: Source Trust, Bandwagon Effect and Innovation Adoption Factors. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.; Le, H.T.P.M.; Choi, D. Understanding the Role of Anticipated Loss and Gain during Consumer Competition: The Moderation of Purchase Importance and Prior Brand Attitude. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2022, 50, 1302–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; He, W.; Guo, X.; Hou, C. Influencing Mechanism of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Circular Products: A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 27, 1771–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esade Business & Law School AI and Influencer Marketing: How Businesses Can Navigate the Future. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/esade/2024/10/30/ai-and-influencer-marketing-how-businesses-can-navigate-the-future/ (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Koles, B.; Audrezet, A.; Moulard, J.G.; Ameen, N.; McKenna, B. The Authentic Virtual Influencer: Authenticity Manifestations in the Metaverse. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Wang, Z. The Ethics of Virtuality: Navigating the Complexities of Human-like Virtual Influencers in the Social Media Marketing Realm. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, 1205610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenyan, J.; Mirowska, A. Almost Human? A Comparative Case Study on the Social Media Presence of Virtual Influencers. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 155, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; MacDorman, K.F.; Kageki, N. The Uncanny Valley. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Yuan, C.W. I’m Not a Puppet, I’m a Real Boy! Gender Presentations by Virtual Influencers and How They Are Received. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 149, 107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, D.L.; Phillips, J. Product Gender Perceptions and Antecedents of Product Gender Congruence. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavior Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E.; Kleka, P.; Lew, R. Using Power Analysis to Estimate Appropriate Sample Size. Trends Sport Sci. 2014, 4, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS: Introducing Statistical Method; Sage Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.W.; Scheinbaum, A.C. Enhancing Brand Credibility Via Celebrity Endorsement: Trustworthiness Trumps Attractiveness and Expertise. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. Ad-Induced Affect: The Effects of Forewarning, Affect Intensity, and Prior Brand Attitude. J. Mark. Commun. 2010, 16, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 87. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer Endorsements in Advertising: The Role of Identification, Credibility, and Product-Endorser Fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F. Effective Influencer Marketing: A Social Identity Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Renk, U.; Mishra, A. Exploring the Impact of Employees’ Self-Concept, Brand Identification and Brand Pride on Brand Citizenship Behaviors. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, C.-V.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A.K. Generation Z Consumers’ Expectations of Interactions in Smart Retailing: A Future Agenda. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zniva, R.; Weitzl, W.J.; Lindmoser, C. Be Constantly Different! How to Manage Influencer Authenticity. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 1485–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainolfi, G.; Lo Presti, L.; Marino, V.; Filieri, R. “YOU POST, I TRAVEL.” Bloggers’ Credibility, Digital Engagement, and Travelers’ Behavioral Intention: The Mediating Role of Hedonic and Utilitarian Motivations. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascot Madness. Available online: https://www.mindfulmarketing.org/mindful-matters-blog/7758067 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Chung, M.; Kim, N.; Jones-Jang, S.M.; Choi, J.; Lee, S. I See a Double-Edged Sword: How Self-Other Perceptual Gaps Predict Public Attitudes toward ChatGPT Regulations and Literacy Interventions. New Media Soc. 2025, 14614448241313180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.; Bae, G. Forever Young, Beautiful and Scandal-Free: The Rise of South Korea’s Virtual Influencers. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/style/article/south-korea-virtual-influencers-beauty-social-media-intl-hnk-dst (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Häberle, E. Virtual Influencer—How AI Is Changing Marketing. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/virtual-influencer-how-ai-is-changing-marketing/video-71474779 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Klein, M. The Problematic Fakery of Lil Miquela Explained—An Exploration of Virtual Influencers and Realness. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/mattklein/2020/11/17/the-problematic-fakery-of-lil-miquela-explained-an-exploration-of-virtual-influencers-and-realness/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Ju, N.; Kim, T.; Im, H. Fake Human but Real Influencer: The Interplay of Authenticity and Humanlikeness in Virtual Influencer Communication? Fash. Text. 2024, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influencer Marketing Hub. AI, Digital Clones, and Virtual Influencers: The New Face of Fashion Marketing. 2025. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/ai-digital-clones-and-virtual-influencers-the-new-face-of-fashion-marketing/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Bloom, D. Want Gen Z to Watch Your Movie? Go Short to Get Them to Go Long. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/dbloom/2023/10/31/want-gen-z-to-watch-your-movie-go-short-to-get-them-to-go-long/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Muliadi, B. What the Rise of TikTok Says About Generation Z. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2020/07/07/what-the-rise-of-tiktok-says-about-generation-z/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Bai, X.; Cheng-Xi Aw, E.; Wei-Han Tan, G.; Ooi, K.-B. Livestreaming as the next Frontier of E-Commerce: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 65, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, M.; Thalmann, J.; Andrea, S. Virtual Influencers: The Impact of Cultural Intelligence on Perceived Credibility. In Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy, Lisbon, Portugal, 25–27 September 2024; p. 122543. [Google Scholar]

- De Mooij, M.; Hofstede, G. The Hofstede Model: Applications to Global Branding and Advertising Strategy and Research. Int. J. Advert. 2010, 29, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, C.; Baima, G.; Janovská, K.; Bresciani, S. Navigating the Uncertainty Path of Virtual Influencers: Empirical Evidence through a Cultural Lens. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 210, 123896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Trade Commission. Disclosures 101 for Social Media Influencers. 2019. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/disclosures-101-social-media-influencers (accessed on 20 June 2025).

| Airbnb | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Airbnb Attitude | 0.94 | 0.80 | 0.90 | ||||||

| 2. Hedonic | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.09 | 0.91 | |||||

| 3. Utilitarian | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.17 * | 0.26 * | 0.88 | ||||

| 4. Similarity | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 0.20 * | 0.08 | 0.90 | |||

| 5. Authenticity | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.22 * | 0.07 | 0.44 * | 0.86 | ||

| 6. Attractiveness | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.24 * | 0.10 * | 0.38 * | 0.49 * | 0.83 | |

| 7. Purchase | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.10 * | 0.30 * | 0.02 | 0.38 * | 0.49 * | 0.37 * | 0.87 |

| NJM | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. NJM Attitude | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.93 | ||||||

| 2. Hedonic | 0.96 | 0.83 | −0.01 | 0.91 | |||||

| 3. Utilitarian | 0.93 | 0.78 | −0.01 | 0.26 * | 0.88 | ||||

| 4. Similarity | 0.95 | 0.81 | −0.09 | 0.20 * | 0.08 | 0.90 | |||

| 5. Authenticity | 0.94 | 0.75 | −0.16 * | 0.22 * | 0.07 | 0.44 * | 0.86 | ||

| 6. Attractiveness | 0.88 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.23 * | 0.09 | 0.36 * | 0.48 * | 0.80 | |

| 7. Purchase | 0.90 | 0.75 | −0.05 | 0.30 * | 0.02 | 0.38 * | 0.49 * | 0.36 * | 0.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, H.-K.; Lin, C.A. Consumer Evaluation of Virtual vs. Human Influencers via Source Credibility, Perceived Social Similarity, and Consumption Motivation. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030168

Zeng H-K, Lin CA. Consumer Evaluation of Virtual vs. Human Influencers via Source Credibility, Perceived Social Similarity, and Consumption Motivation. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030168

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Huai-Kuan, and Carolyn A. Lin. 2025. "Consumer Evaluation of Virtual vs. Human Influencers via Source Credibility, Perceived Social Similarity, and Consumption Motivation" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030168

APA StyleZeng, H.-K., & Lin, C. A. (2025). Consumer Evaluation of Virtual vs. Human Influencers via Source Credibility, Perceived Social Similarity, and Consumption Motivation. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030168