Abstract

Online travel agencies (OTAs) function as e-commerce platforms that facilitate transactions between accommodation providers and consumers, enabling users to efficiently search for, compare, and book travel and lodging services. As the number of OTAs continues to grow, delivering superior service quality has become essential for increasing customer repurchase intentions. Despite its significance, existing research has primarily focused on factors such as website quality, pricing strategies, brand image, and perceived value as determinants of repurchase intention. However, relatively little attention has been paid to the alignment between online information disclosure and customers’ actual offline experiences. To address this gap, the present study introduces the concept of the information disclosure gap and examines its effects on search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust, as well as the subsequent influence of these variables on repurchase intention. A questionnaire-based survey method was conducted with individuals in Taiwan who had prior experience using OTAs, yielding 365 valid responses. This study offers practical insights and recommendations for both OTAs and accommodation providers aimed at reducing the information disclosure gap and strengthening customer repurchase intention.

1. Introduction

With the easing of the COVID-19 pandemic and the reopening of international borders, the global tourism market has experienced a strong rebound, resulting in a surge in outbound travel. According to statistics from the Tourism Bureau of the Ministry of Transportation and Communications in Taiwan, the number of outbound travelers from January to November 2023 reached approximately 10.74 million. Notably, for six consecutive months—from June to November—monthly outbound travelers exceeded one million. In parallel with this resurgence in tourism, technological advancements and evolving consumer behaviors have led an increasing number of Taiwanese travelers to use the internet to search for and arrange travel and accommodation services [1]. Consequently, travel and accommodation providers in Taiwan are investing more resources into website development and partnerships with online travel agencies (OTAs) to enhance visibility, reputations, and sales performance.

However, the rapid expansion of the online booking market has also been accompanied by a rise in customer disputes, contributing to increased uncertainty and skepticism toward online travel platforms. For example, Taiwan’s United Daily News [2] reported a case in which a customer booked a 15-ping double room for TWD 4280 through an OTA, only to find upon arrival that the actual room was only about 6 pings and the advertised king-size bed was, in fact, a standard double bed. In response to the complaint, the accommodation provider explained that the listed room size included shared common areas deemed accessible to guests, while the discrepancy in bed size stemmed from differing interpretations of what constitutes a “king-size” bed. Similar inconsistencies have been reported in other cases, such as notable disparities between the online images of hotel environments and their actual physical conditions, or between the advertised and actual meals provided. These discrepancies are not isolated incidents; rather, they reflect recurring patterns in consumer complaints, online reviews, and media reports, suggesting that the issue is systemic rather than merely anecdotal. These problems primarily arise from the inherent limitations of online platforms, where customers typically rely on photos and textual descriptions—covering room conditions, facilities, services, meals, and user reviews—without the ability to engage in real-time interactions as they could in physical hotel settings. As a result, when customers redeem the accommodation service offline, their actual experiences may diverge from their original expectations [3]. To reduce such uncertainty, customers tend to seek comprehensive and reliable accommodation information before booking in order to enhance confidence in their decisions. Therefore, the completeness and accuracy of the accommodation information disclosed by OTAs not only influence customers’ actual experiences but also affect their perceptions of the accommodation and their willingness to reuse the OTA platform in the future.

Although research on OTAs has grown in recent years, most existing studies have primarily focused on antecedent variables such as website quality [4,5], pricing strategies [6], brand image [1], and perceived value [7,8] to investigate their effects on customer repurchase intention. However, relatively little attention has been given to integrating the online information disclosed by OTAs with customers’ actual offline accommodation experiences in order to understand the factors influencing customer repurchase intention. To address this gap, this study introduces the concept of an information disclosure gap, defined as the discrepancy between customers’ perceptions based on the information disclosed on OTA websites and their actual lodging experiences. This research examines the effects of the information disclosure gap on search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust, and further explores how these variables influence customer repurchase intention. Finally, the study provides practical recommendations for OTAs and accommodation providers to reduce the information disclosure gap and enhance customer repurchase intention.

2. Conceptual Development and Hypotheses

2.1. Information Disclosure Gap

Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECT) posits that consumers develop initial expectations about a product or service prior to purchase. After consumption, they form perceptions based on actual performance and compare these with their prior expectations to determine the degree of confirmation. This comparison results in one of three outcomes: positive disconfirmation (perceived performance exceeds expectations), confirmation (performance meets expectations), or negative disconfirmation (performance falls short of expectations) [9].

Hurme [10] observed that when purchasing unfamiliar or high-value products in online settings, consumers often seek additional information and recommendations to support their decision-making. Information disclosure on shopping websites aims to increase market transparency and reduce decision errors arising from information asymmetry. In their study on group-buying websites, Tseng and Lee [11] defined information disclosure as the comprehensive set of information presented on such platforms. Similarly, online travel agencies (OTAs) act as intermediaries that enable users to efficiently search for, compare, and book accommodation services [12]. Before booking, consumers typically evaluate the accommodation information disclosed on these platforms and form corresponding expectations. Following the stay, they compare their actual lodging experience with these expectations. When a discrepancy arises between the expected and actual experience, an information disclosure gap occurs.

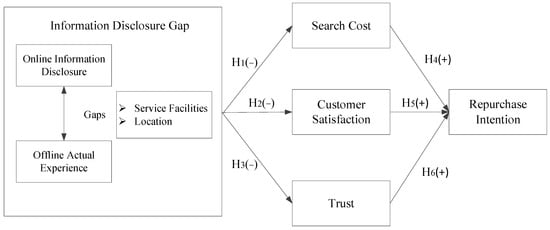

Grounded in ECT, this study conceptualizes the information disclosure gap as the divergence between customers’ expectations—shaped by information disclosed on OTA websites—and their actual offline accommodation experiences. The primary objective of this research is to investigate factors influencing customer repurchase intention in the context of OTAs. Specifically, it examines the effects of the information disclosure gap on search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust, and further explores how these variables affect repurchase intention. The proposed research model is presented in Figure 1, with key constructs and hypotheses elaborated in the following sections.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized research model. Source(s): created by the author.

2.2. Search Cost

Liang and Huang [13] described search cost as the perceived costs incurred during the process of gathering product- or process-related information. Lynch and Ariely [14] further defined search cost as the expenses consumers face when intending to purchase a specific product or service and needing to search for and compare information related to its price and quality. Wilson [15] emphasized that such costs are incurred regardless of whether a purchase is ultimately made, as they arise from the need to identify product and pricing information. Similarly, Teo and Yu [16] argued that consumers typically engage in information searches and continuous observation prior to a transaction in order to secure the best possible deal. They highlighted that search costs encompass the time and effort involved in collecting relevant product or service information and comparing features and prices across various online platforms. In summary, search cost refers to the perceived effort and resources—such as time, cognitive effort, and attention—expended by consumers when acquiring information about products or services before making a purchase decision [11]. Based on this reasoning, this study posits that if OTAs can provide sufficient and accurate information to meet consumer expectations, the associated information disclosure gap can be minimized, thereby reducing the additional effort and resources consumers must expend in searching for accommodation-related information. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1:

The information disclosure gap negatively affects search cost.

2.3. Customer Satisfaction

Satisfaction refers to the extent to which customers’ expectations regarding the performance of a product or service align with their actual experiences, forming an overall post-purchase evaluation [17,18,19]. In the context of e-commerce, DeLone and McLean [20] defined user satisfaction as a comprehensive evaluation of the entire website experience—including purchasing, payment, delivery, and information retrieval—after interacting with the platform. Camacho et al. [21] further described satisfaction as an emotional construct through which consumers assess how well a product or service fulfills their needs, incorporating subjective feelings shaped by their experiences. In the domain of online travel services, Mills and Morrison [22] emphasized that the perceived quality of products and services displayed by OTAs significantly influences customers’ online experiences and, consequently, their satisfaction. Similarly, Chung-Hoon and Young-Gul [23] highlighted that online consumers must make purchasing decisions based solely on the information presented on OTA platforms. When this information is perceived as accurate and beneficial, it fosters greater satisfaction with the platform, which in turn strengthens customer loyalty. Accordingly, when there is a discrepancy between the information disclosed on OTAs and the actual service experience—i.e., an information disclosure gap—customers may feel disappointed or misled, reducing their satisfaction with the OTA platform. Based on this rationale, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

The information disclosure gap negatively affects customer satisfaction.

2.4. Trust

Gambetta [24] argued that trust allows individuals or enterprises to place confidence in a partner, rooted in the belief that the other party will adhere to social or business norms [25]. Chakraborty et al. [26] described perceived trust as an individual’s subjective confidence in the reliability, honesty, and dependability of another party within a specific context. Trust is often built upon previous interactions that foster expectations about future behavior [27]. However, when outcomes deviate from expectations, it can lead to dissatisfaction and a deterioration of trust [28]. In addition, Mofokeng [29] noted that customer trust in online shopping is influenced by perceived ease of use, which reflects the extent to which a system reduces users’ mental and physical effort. Systems that offer intuitive and user-friendly interfaces contribute to greater trust by simplifying the decision-making process. Accordingly, trust plays a crucial role in facilitating business transactions by enabling individuals or organizations to confidently engage with others. In the context of OTAs, when there is a discrepancy between the information presented on the platform and the actual offline accommodation experience—i.e., an information disclosure gap—customers may feel deceived or disappointed, thereby undermining their trust in the OTA platform. Based on this reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3:

The information disclosure gap negatively affects trust.

2.5. Repurchase Intention

Behavioral intention refers to an individual’s subjective probability or likelihood of performing a particular behavior, representing one’s personal judgment about the potential for future action [30,31]. Within this framework, purchase intention is defined as the consumer’s likelihood or inclination to buy a specific product, serving as a critical predictor of actual purchasing behavior [32]. Extending this concept, repurchase intention denotes the consumer’s subjective tendency or willingness to purchase a product or service again. Chuah et al. [33] emphasized that repurchase intention not only signals the possibility of repeated transactions but also serves as a behavioral expression of customer loyalty.

Liang and Huang [13] argued that search cost significantly influences purchase intention, with lower search costs contributing to stronger intentions to buy. Similarly, Shao et al. [34] noted that customers search for product-related information based on prior experiences before evaluating alternatives and making purchasing decisions. Tseng and Lee [11] further demonstrated that when group-buying websites help reduce consumer search costs, customers exhibit higher purchase intentions. Therefore, this study posits that when OTAs effectively reduce search costs by providing comprehensive and accessible information, consumers are more likely to engage in repeat purchases. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H4:

A reduction in search cost positively affects repurchase intention.

Many previous studies have confirmed that customer satisfaction has a strong positive impact on repurchase intention. For instance, Liang et al. [35] found that travelers’ satisfaction with Airbnb significantly influences their intention to book accommodations on the platform again. Similarly, Padma and Ahn [36], in their study on factors influencing customer satisfaction with luxury hotels, concluded that when customers are satisfied with the service quality, they are more likely to return and recommend the service to others. Conversely, if a luxury hotel fails to deliver high-quality service, customers are less likely to revisit and may spread negative feedback through online travel platforms. Wei et al. [37] further emphasized that satisfaction with online travel agencies (OTAs) serves as a key driver in shaping customer expectations and repurchase intentions. Therefore, customer satisfaction can be considered one of the most reliable predictors of repurchase behavior [38]. Building on this body of literature, the present study posits that higher levels of satisfaction with OTAs are likely to enhance customers’ repurchase intentions. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5:

Customer satisfaction positively affects repurchase intention.

Reichheld and Schefter [39] emphasized that trust is a critical prerequisite for consumers to participate in group-buying activities, while Gefen et al. [40] found that trust has a direct and positive influence on consumers’ purchase decisions in online retail environments. Similarly, Keh and Xie [41] highlighted that trust is often built upon long-term relationships between consumers and online businesses. Since higher levels of trust can significantly reduce the perceived risk associated with online shopping, trust becomes a key determinant in the success of such transactions [39]. Palvia [42] also noted that trust plays a foundational role in fostering long-term business relationships by mitigating consumer uncertainty and increasing their willingness to use a website. In other words, continuous interactions between buyers and sellers can facilitate the exchange of knowledge, reduce uncertainty, and ultimately enhance purchase intentions. Based on this rationale, this study posits that customer trust in an OTA positively contributes to their intention to make repeat purchases. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H6:

Trust positively affects repurchase intention.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling

Although online travel agencies (OTAs) such as Agoda, Booking.com, and Expedia offer a wide range of travel-related services—including accommodation reservations, flight bookings, and car rentals—this study specifically focuses on the accommodation booking services provided through these platforms. Accordingly, the target population comprises individuals with prior experience in booking accommodations via OTAs. To ensure the quality and relevance of the data collected, purposive sampling (a non-probability sampling method) was employed. The questionnaire was administered via the online survey platform SurveyCake, and the survey link was distributed via popular social media platforms (e.g., LINE and Facebook) to reach individuals with prior experience using online travel agencies (OTAs). Data collection began on 7 February 2025 and lasted for ten days. To verify respondent eligibility, the first question of the survey explicitly asked whether the participant had ever used OTAs to book accommodation services (e.g., Booking.com, Agoda, Expedia, etc.). This was a required question, and only those who provided a valid response could proceed with the rest of the survey. Furthermore, all subsequent items in the questionnaire were set as mandatory, preventing incomplete submissions. As a result, all 365 responses were complete and deemed valid, and no responses had to be excluded. Since purposive sampling was used, no sampling error was calculated. However, the screening question and mandatory input design helped ensure the reliability and consistency of the collected data. Among the respondents, 52.3% were female, indicating a slightly higher female participation rate. The most represented age group was 30 to 39 years (48.5%), followed by those aged 40 to 49 years (28.4%), suggesting that middle-aged adults constitute the primary user demographic for OTA accommodation services. In terms of educational background, 68.0% of participants held a college degree, followed by 14.2% who had completed junior college. Additionally, 51.5% of respondents were married. Subsequent statistical analyses were performed on the collected data to test the proposed hypotheses and fulfill the research objectives.

3.2. Measures Instruments

All questionnaire items were originally written in Chinese using straightforward language to ensure participant comprehension. A panel of academic scholars and industry experts reviewed the draft instrument, resulting in minor revisions to improve clarity. A seven-point Likert scale was employed for all constructs—ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (neutral) to 7 (strongly agree)—to assess participants’ level of agreement. The final questionnaire items and corresponding references are presented in Table 1. Each construct was operationalized based on prior studies and validated through a pilot test.

The measurement items in the questionnaire were developed based on an extensive review of the relevant literature. First, this study defines the information disclosure gap as the discrepancy perceived by customers when their expectations regarding the information disclosed by OTAs exceed their actual offline experiences [43,44]. As prior research has yet to establish a standardized scale for measuring the information disclosure gap on online travel agency (OTA) platforms, this study aimed to develop such a scale. The measurement items for the information disclosure gap were adapted from the frameworks proposed by Wang, Du, Chiu and Li [9] and Tseng and Lee [11], tailored to reflect the context of OTA accommodation booking services. Second, customer satisfaction is defined as the customer’s overall assessment of how well the services provided by OTAs meet their expectations [45]. The corresponding questionnaire items were developed based on Camacho, Hassanein and Head [21] and Chatzoglou et al. [46]. This study defines search cost as the minimization of time and effort required to retrieve information regarding product content, pricing, and the purchasing process [16]. Measurement items for this construct were adapted from Tseng and Lee [11]. Trust is conceptualized as the degree to which consumers believe in the accuracy and reliability of the information provided by OTA platforms and perceive that the platforms act in the consumers’ best interests [47]. The measurement of trust draws upon the scale developed by Doney and Cannon [48] and Tseng and Lee [11]. Finally, repurchase intention refers to the likelihood or subjective inclination of customers to return to OTAs for future accommodation bookings [30,31]. Questionnaire items for this construct were adapted from Chatzoglou, Chatzoudes, Savvidou, Fotiadis and Delias [46] and Hsu et al. [49].

Table 1.

The questionnaire items and related references.

Table 1.

The questionnaire items and related references.

| Research Variables | Items |

|---|---|

| Ahmad and Zhang [44]; Wang, Du, Chiu and Li [9]; Tseng and Lee [11] | |

| Information disclosure gap |

|

| Camacho, Hassanein and Head [21]; Chatzoglou, Chatzoudes, Savvidou, Fotiadis and Delias [46]; Oliver [45] | |

| Customer satisfaction |

|

| Teo and Yu [16]; Tseng and Lee [11] | |

| Search cost |

|

| Doney and Cannon [48]; Singh and Sirdeshmukh [47]; Tseng and Lee [11] | |

| Trust |

|

| Fishbein and Ajzen [30]; Chatzoglou, Chatzoudes, Savvidou, Fotiadis and Delias [46]; Hsu, Chang, Chu and Lee [49]; Schiffman and Kanuk [31] | |

| Repurchase intention |

|

Source(s): created by the authors.

3.3. Common Method Bias (CMB)

To address the issue of common method variance (CMV), the questionnaire was subjected to expert and scholarly review and pilot testing prior to official distribution. This process ensured that the wording and conceptual clarity of each measurement item were appropriate and free from ambiguity. Furthermore, prior to administering the questionnaire, respondents were explicitly informed that there were no right or wrong answers and were encouraged to respond honestly based on their actual experiences, in order to minimize potential bias stemming from social desirability or consistency motifs [50]. In addition, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to statistically assess the presence of CMV. The unrotated exploratory factor analysis revealed that the first factor accounted for 48.5% of the total variance, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 50% [51]. This indicates that no single factor dominated the variance, suggesting that common method variance does not pose a serious threat to the validity of the study’s findings.

3.4. Data Analysis Procedure

This study adopted a multi-method analytical approach. Initially, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring and varimax rotation was conducted to identify the underlying dimensions of five constructs: information disclosure gap, customer satisfaction, trust, search cost, and repurchase intention. Sampling adequacy was confirmed by a KMO value of 0.80 and a significant result in Bartlett’s test (p < 0.001). Items with factor loadings below 0.70 or with cross-loadings greater than 0.30 were excluded from further analysis. Subsequently, factors were named according to the thematic relevance of the items grouped under each factor [52]. Based on EFA results, the information disclosure gap was empirically categorized into two sub-dimensions: service facility gap and location gap. For customer satisfaction and repurchase intention, items CS3 and RI1 were removed due to insufficient discriminant validity, indicated by factor loading differences less than 0.30 between primary and secondary constructs. All items under search cost and trust met the statistical criteria and were retained.

Following the EFA, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were employed to validate the measurement model and test the hypothesized relationships within the conceptual framework. For the structural analysis, this study utilized Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM estimates model parameters by minimizing the residual variance of the endogenous (dependent) variables, thereby enhancing the model’s predictive capabilities. The structural model evaluates the hypothesized relationships among latent constructs, whereas the measurement model assesses the relationships between observed indicators and their respective latent variables. Compared to traditional covariance-based SEM, PLS-SEM is more flexible with respect to distributional assumptions, measurement scale types, and sample size requirements [53,54]. Given the exploratory nature of this research, particularly in developing and testing a novel model incorporating the constructs of information disclosure gap, customer satisfaction, trust, search cost, and repurchase intention, PLS-SEM was considered the most appropriate analytical technique. All analyses were performed using SmartPLS 4.0 software.

4. Results

4.1. The Measurement Model

A null model was initially specified for the first-order latent variables, with no structural paths included to establish a baseline for measurement assessment. As the constructs in this study were conceptualized as reflective in nature—wherein the observed items are assumed to be manifestations of their underlying latent variables—the evaluation focused on assessing internal consistency and validity through commonly accepted psychometric criteria. To evaluate the reliability of the constructs, Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated. As presented in Table 2, all CA and CR values exceeded the threshold of 0.800, indicating high internal consistency [55]. Additionally, the AVE values for all constructs surpassed the recommended cut-off value of 0.500, demonstrating satisfactory convergent validity [54].

Table 2.

Psychometric properties in the null model for first-order constructs (n = 365).

Furthermore, Table 3 shows that the square roots of the AVE for each construct were greater than the inter-construct correlations, thereby showing good discriminant validity [56]. Additional evidence of discriminant validity was obtained through an analysis of cross-loadings, which revealed that each item loaded more strongly on its corresponding construct than on any other [53,54]. Overall, as evidenced in Table 2 and Table 3, the measurement model exhibited strong internal consistency reliability, indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, confirming the robustness of the measurement instruments employed in this study [57].

Table 3.

Mean, S.D., and intercorrelations of the latent variables for first-order constructs.

Table 4 reports the CA, CR, and AVE for the second-order constructs—service facility gap and location gap—within the information disclosure gap model. The results indicate that both CA and CR values exceed 0.961, and AVE values are above 0.70, thereby providing strong evidence of the reliability and convergent validity of the measurement model. Furthermore, the factor loadings of the first-order latent construct (information disclosure gap) onto the second-order factors are all above 0.80, and all loadings are statistically significant at α = 0.01, thus confirming the robustness and validity of the second-order model structure.

Table 4.

Assessing the second-order model of the information disclosure gap.

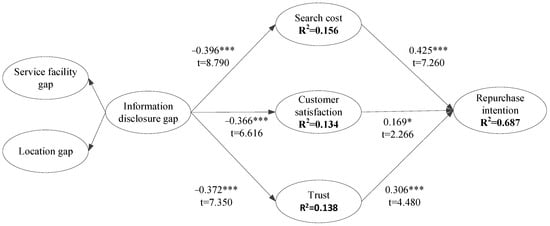

4.2. Structural Model

The structural model was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships among the dependent and independent latent constructs. To assess the significance of the path coefficients, a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples based on the original dataset of 365 respondents was conducted. The resulting structural model is depicted in Figure 2. The coefficient of determination (R2) indicates the proportion of variance in the endogenous constructs explained by the exogenous variables. The model reveals a substantial R2 value of 0.687 for repurchase intention, while the R2 values for search cost (0.156), customer satisfaction (0.134), and trust (0.138) indicate relatively weak explanatory power, which remains acceptable for exploratory research [54]. The results demonstrate that the information disclosure gap has a significant negative effect on search cost (H1: β = −0.396, p < 0.001), customer satisfaction (H2: β = −0.366, p < 0.001), and trust (H3: β = −0.372, p < 0.001). Furthermore, search cost (H4: β = 0.425, p < 0.001), customer satisfaction (H5: β = 0.169, p < 0.05), and trust (H6: β = 0.306, p < 0.001) each exhibit a significant positive influence on repurchase intention. Collectively, these findings provide empirical support for all proposed hypotheses.

Figure 2.

PLS structural model. Note(s): * denotes path coefficients significant at the p < 0.05 level; *** denotes path coefficients significant at the p < 0.001 level.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the relationships among the information disclosure gap, search cost, customer satisfaction, trust, and repurchase intention in the context of OTAs. Specifically, it examined the effects of the information disclosure gap on search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust. In addition, it explored how these three factors—search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust—affect repurchase intention in the OTA context. Theoretical contributions and practical implications of the findings are presented and discussed in the subsequent sections.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, this study applies information disclosure theory and introduces the concept of an information disclosure gap in the context of OTAs, referring to the discrepancy between customers’ expectations formed from accommodation information presented on OTA websites and their actual perceptions after experiencing the accommodation. Given that previous research has not established a specific scale to measure information disclosure gap on OTAs, one of this study’s key contributions is the development of such a measurement scale. Based on the EFA results, the information disclosure gap was empirically categorized into two distinct sub-dimensions: service facility gap and location gap. Moreover, this study examines the effects of the information disclosure gap on search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust, as well as the subsequent effects of these factors on repurchase intention. The results show that all path coefficients in the hypothesized model are statistically significant and substantial. The variance explained for each factor suggests that, collectively, these predictors offer meaningful insights into how the information disclosure gap in OTAs influences customers’ repurchase intentions through variables such as search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust. These findings imply that when OTAs provide comprehensive, accessible, and accurate information—particularly regarding service facility and location details—they can effectively reduce consumers’ search costs and, in turn, enhance customer satisfaction and trust. In the online shopping environment, customers demand more abundant and detailed information than ever before. Therefore, e-commerce operators should proactively disclose clear, reliable, and up-to-date information, rather than leveraging information asymmetry to their advantage, which could mislead consumers and result in suboptimal decision-making [11]. Based on these insights, this study recommends that OTAs improve the transparency of key service information, especially regarding accommodation service facility and location, and regularly update the disclosed content. Doing so can help minimize the information disclosure gap, reduce uncertainty, and ultimately increase customers’ repurchase intentions.

Second, by integrating the information disclosure gap into the customer behavior framework, this study highlights how mitigating this gap can reduce customer uncertainty. This approach enriches the application of customer behavior theory in e-commerce and tourism contexts while also contributing to the broader literature on information asymmetry. Furthermore, this research adopts a cross-disciplinary perspective by integrating insights from information management, marketing psychology, and tourism management. This interdisciplinary model offers a comprehensive framework for understanding customer experience and serves as a foundation for future discussions on topics such as the online–offline experiential gap.

Finally, the conceptual framework proposed in this study—information disclosure gap → search cost, satisfaction, trust → repurchase intention—provides a theoretical basis for future quantitative or cross-cultural comparative research. It also offers valuable directions for extending theories related to service quality in OTAs and other digital platforms.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study introduces the concept of the information disclosure gap to examine the discrepancy between customers’ online expectations and their actual accommodation experiences. The findings offer valuable practical insights for OTA platforms and service providers, particularly in optimizing the design and presentation of disclosed information—such as accommodation services, facilities, location, room features, meals, and customer reviews. By aligning online content more closely with the actual experience, platforms can help reduce customers’ search costs, enhance decision-making efficiency, and establish differentiated competitive advantages. Therefore, the results of this study hold significant practical value for improving both user experience and platform competitiveness.

As the hypothesized antecedents of search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust, the information disclosure gap has a very significant effect on search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust, and it has comparable path coefficients with regard to search cost (β = −0.369), customer satisfaction (β = −0.366), and trust (β = −0.372). This result implies that the information disclosure gap is almost equally important for the formation of search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust. This suggests that when OTAs create overly high expectations through the presentation of accommodation information, a significant information disclosure gap may arise if the actual experience does not match these expectations. As this gap widens, customer satisfaction and trust in the OTA platform are likely to diminish, and customers may exert more effort in searching for and comparing accommodation options in future bookings. While embellishing or idealizing accommodation details may increase short-term purchase motivation and boost sales, it also carries the risk of disappointing customers if the actual experience falls short. In such cases, customers may choose not to return. As noted by Harun et al. [58], online consumers can easily abandon a transaction and sever their relationship with an OTA with just one click—highlighting the fragile nature of trust and loyalty in digital environments. Therefore, in terms of practical operational strategies, this study suggests that OTA platform operators should enhance the clarity and completeness of accommodation-related information on their websites. Specifically, regarding service facilities, OTAs should explicitly disclose whether the property offers 24 h front desk service, complimentary luggage storage, daily housekeeping, and additional customized services such as extra beds or pillow replacements to meet diverse customer needs. Furthermore, the availability of free and high-speed Wi-Fi, as well as access to shared amenities such as gyms, swimming pools, and parking (whether free or paid), should be clearly indicated. For each of these facilities, the website should provide detailed information about operating hours, usage fees, reservation requirements, and payment methods. It is also important to specify whether the accommodation includes elevators or barrier-free facilities to accommodate guests with mobility challenges or those carrying large luggage. In addition, the website should clearly list in-room amenities, such as desks, bathtubs, hair dryers, power adapters, or HDMI cables. Regarding the location, OTAs should state the approximate distance between the accommodation and key destinations such as tourist attractions, commercial areas, and subway or bus stations. It is also helpful to provide information about the availability of nearby amenities, including convenience stores, restaurants, and supermarkets, as well as whether the hotel offers airport pick-up services. When platforms provide such information, consumers are able to make informed decisions with less time and effort, thereby reducing search costs and enhancing both satisfaction and trust. Ultimately, this leads to a greater likelihood of repeat purchases [59,60].

As hypothesized antecedents of repurchase intention, search cost, customer satisfaction, and trust all have very significant effects on repurchase intention, and as shown by their path coefficients, search cost (β = 0.425) is more influential than trust (β = 0.306) and customer satisfaction (β = 0.169). This study finds that reducing the search cost contributes significantly to repurchase intention. This result has implications that greater reductions in search cost contribute to the formation of more favorable repurchase intention [13]. This means that improving information flows and proactively providing consumers with more information related to a purchase will help reduce search cost, and eventually increase repurchase intention. Therefore, this study suggests that OTAs should not only provide a stable online platform, but also provide a customized search function in order to meet consumers’ personal preferences, so that they can quickly find information regarding the service, facilities, location, meal, rooms, and reviews they are looking for, thus decreasing search cost and increasing repurchase intention. Moreover, this study finds that trust and customer satisfaction contribute significantly to repurchase intention [39,61]. This implies that higher levels of trust and customer satisfaction with an OTA contribute significantly to the formation of stronger repurchase intentions. Therefore, OTAs should prioritize consumer interests to build trust and enhance customer satisfaction, which, in turn, can lead to increased customer repurchase behavior [40,42].

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the significant findings of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged, pointing to opportunities for future research to enhance the generalizability and robustness of the results. First, this study was conducted within the cultural and market context of Taiwan, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other regions. Given that consumer behavior is deeply influenced by cultural norms and digital maturity, it is important to recognize that perceptions of information disclosure gaps may vary across societies. Future studies are encouraged to conduct cross-national or cross-cultural investigations, particularly in markets with different consumer orientations (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism), to examine the cultural contingencies that may affect how consumers interpret and respond to information discrepancies on OTA platforms. Second, the modes and degree of information disclosure may vary significantly across different OTA platforms. Comparative analyses across multiple platforms could provide a more nuanced understanding of how various disclosure practices shape user perceptions and behavioral intentions. Third, while the R2 values for the mediating variables—search cost (R2 = 0.156), customer satisfaction (R2 = 0.134), and trust (R2 = 0.138)—are modest, they remain within acceptable thresholds for exploratory research in behavioral and social science domains [54]. These values suggest that although the information disclosure gap has a statistically significant influence, other variables not included in the current model may also play important roles and should be explored in future studies. Finally, this study employed a cross-sectional survey design, which limits the ability to capture the dynamic nature of customer experiences over time. Longitudinal studies are recommended to observe how customer perceptions evolve in response to ongoing interactions with OTA platforms and actual lodging outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-M.T.; methodology, S.-M.T.; software, S.-M.T.; validation, S.-M.T.; formal analysis, S.-M.T.; investigation, S.-M.T.; resources, S.-M.T.; data curation, S.-M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-M.T.; writing—review and editing, N.H.; visualization, S.-M.T.; supervision, S.-M.T.; project administration, S.-M.T.; funding acquisition, S.-M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the following academic institution’s ethics policy, the National Taiwan University Hospital Institutional Review Board indicates that: “Anonymous surveys that do not collect identifiable personal information and involve minimal risk may be exempt from ethics review.”

Informed Consent Statement

Regarding the Informed Consent Statement, because the survey was anonymous and completed voluntarily, no signed consent was obtained in order to preserve anonymity and avoid discouraging participation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ray, A.; Bala, P.K.; Rana, N.P. Exploring the drivers of customers’ brand attitudes of online travel agency services: A text-mining based approach. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News, U.D. He booked a room online but got only 7 ping for NT$4,280—Owner claims it includes public space. UDN News 2023.

- Salameh, A.A.; Al Mamun, A.; Hayat, N.; Ali, M.H. Modelling the significance of website quality and online reviews to predict the intention and usage of online hotel booking platforms. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, W.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Perng, C. A strategic website evaluation of online travel agencies. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.N.K.; Zhang, E.Y. An investigation of factors affecting customer selection of online hotel booking channels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Shi, P. Pricing strategies of tour operator and online travel agency based on cooperation to achieve O2O model. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.-H.; Wen, M.-J.; Huang, L.-C.; Wu, K.-L. Online hotel booking: The effects of brand image, price, trust and value on purchase intentions. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2015, 20, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Why do people purchase from online travel agencies (OTAs)? A consumption values perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-N.; Du, J.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Li, J. Dynamic effects of customer experience levels on durable product satisfaction: Price and popularity moderation. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 28, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurme, P. Mobile communication and work practices in knowledge-based organizations. Hum. Technol. Interdiscip. J. Hum. ICT Environ. 2005, 1, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-M.; Lee, M.-C. A study on information disclosure, trust, reducing search cost, and online group-buying intention. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2016, 29, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Ha, H.-Y. Longitudinal impact of perceived fairness after service failures: Evidence from online travel agencies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 128, 104177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-P.; Huang, J.-S. An empirical study on consumer acceptance of products in electronic markets: A transaction cost model. Decis. Support Syst. 1998, 24, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.G.; Ariely, D. Wine Online: Search Costs Affect Competition on Price, Quality, and Distribution. Mark. Sci. 2000, 19, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.M. Market frictions: A unified model of search costs and switching costs. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2012, 56, 1070–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Yu, Y. Online buying behavior: A transaction cost economics perspective. Omega 2005, 33, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. A National Customer Satisfaction Barometer: The Swedish Experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, Z.R.; Soror, A.A. Why do you keep doing that? The biasing effects of mental states on IT continued usage intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ma, K.; Bian, X.; Zheng, C.; Devlin, J. Is high recovery more effective than expected recovery in addressing service failure?—A moral judgment perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Measuring e-Commerce Success: Applying the DeLone & McLean Information Systems Success Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004, 9, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, S.; Hassanein, K.; Head, M. Cyberbullying impacts on victims’ satisfaction with information and communication technologies: The role of Perceived Cyberbullying Severity. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Morrison, A. Measuring customer satisfaction with online travel. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Frew, A., Hitz, M., O’Connor, P., Eds.; Springer: Wien, Austria; New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Hoon, P.; Young-Gul, K. The Effect of Information Satisfaction and Relational Benefit on Consumers’ Online Shopping Site Commitments. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. 2006, 4, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, D. Can we trust trust? In Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou, P.A. Consumer Acceptance of Electronic Commerce: Integrating Trust and Risk with the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Kumar Kar, A.; Patre, S.; Gupta, S. Enhancing trust in online grocery shopping through generative AI chatbots. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 180, 114737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D. E-commerce: The role of familiarity and trust. Omega 2000, 28, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A. A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, T.E. Antecedents of trust and customer loyalty in online shopping: The moderating effects of online shopping experience and e-shopping spending. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addsion-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Kanuk, L.L. Consumer Behavior, 9th ed; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, H.W.S.; Sujanto, R.Y.; Sulistiawan, J.; Cheng-Xi Aw, E. What is holding customers back? Assessing the moderating roles of personal and social norms on CSR’S routes to Airbnb repurchase intention in the COVID-19 era. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.Y.; Baker, J.A.; Wagner, J. The effects of appropriateness of service contact personnel dress on customer expectations of service quality and purchase intention: The moderating influences of involvement and gender. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Exploring the relationship between satisfaction, trust and switching intention, repurchase intention in the context of Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma, P.; Ahn, J. Guest satisfaction & dissatisfaction in luxury hotels: An application of big data. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Lian, Y.; Li, L.; Lu, Z.; Lu, Q.; Chen, W.; Dong, H. The impact of negative emotions and relationship quality on consumers’ repurchase intention: An empirical study based on service recovery in China’s online travel agencies. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Lin, H.-N.; Luo, M.M.; Chea, S. Factors influencing online shoppers’ repurchase intentions: The roles of satisfaction and regret. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.; Schefter, P. E-Loyalty: Your Secret Weapon on the Web. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.T.; Xie, Y. Corporate reputation and customer behavioral intentions: The roles of trust, identification and commitment. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palvia, P. The role of trust in e-commerce relational exchange: A unified model. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Zhang, Q. Green purchase intention: Effects of electronic service quality and customer green psychology. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzoglou, P.; Chatzoudes, D.; Savvidou, A.; Fotiadis, T.; Delias, P. Factors affecting repurchase intentions in retail shopping: An empirical study. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Sirdeshmukh, D. Agency and Trust Mechanisms in Consumer Satisfaction and Loyalty Judgments. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Chang, C.-M.; Chu, K.-K.; Lee, Y.-J. Determinants of repurchase intention in online group-buying: The perspectives of DeLone & McLean IS success model and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R.; Rips, L.; Rasinski, K. The Psychology of Survey Response; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Hamilton, J.G. Viability of exploratory factor analysis as a precursor to confirmatory factor analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1996, 3, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Cha, J. Partial least squares. In Advanced Methods of Marketing Research; Bagozzi, R.P., Ed.; Blackwell Publisher: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 52–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 259–358. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural equation modeling in information systems research using Partial Least Squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Harun, A.; Rokonuzzaman, M.; Prybutok, G.; Prybutok, V.R. How to influence consumer mindset: A perspective from service recovery. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 42, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeke, A. Travel web-site design: Information task-fit, service quality and purchase intention. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N.N.; Vo, L.T.; Ngan, N.T.T.; Ghi, T.N. The tendency of consumers to use online travel agencies from the perspective of the valence framework: The role of openness to change and compatibility. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, N.; Adil, M.; Sadiq, M.; Dash, G.; Paul, J. Unraveling customer repurchase intention in OFDL context: An investigation using a hybrid technique of SEM and fsQCA. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).