Abstract

Virtual influencers are emerging as a powerful tool in strategic communication, yet their effectiveness as brand endorsers remains underexplored. This study aims to develop a consumer-centric scale to assess virtual influencers’ effectiveness in social media marketing campaigns. The research methodology follows a systematic scale-development process. First, an integrated literature review was conducted to establish a conceptual model for evaluating virtual influencers. Second, an initial pool of evaluation items was developed and validated by experts. Third, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with 208 participants was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the preliminary items. Finally, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with 209 participants was performed to finalize the scale. The resulting measurement scale comprises four key dimensions: communication skills, narrative strategies, visual appearance, and human-like movement. By introducing a structured scale-development method grounded in anthropomorphism, this study enhances the assessment of virtual influencers’ effectiveness in digital marketing campaigns.

1. Introduction

Virtual influencers (VIs) are fictional digital characters created using advanced computer graphics and artificial intelligence technology to replicate human influencers on social media [1,2,3]. These digital personas are developed using sophisticated animation and rendering techniques, such as rigging, shape blending, and computer-generated imagery, allowing them to appear as human-like figures capable of conveying nonverbal cues through facial expressions and body language [4,5]. The rapid advancements in interactive and immersive media technologies have positioned VIs as a prominent force in digital marketing, attracting attention for their ability to serve as brand endorsers across the fashion, beauty, and entertainment industries [1,2,3]. Unlike their human counterparts, VIs are not restricted by physical limitations, making them highly flexible for promotional content [2]. This flexibility has led to the widespread adoption of VIs in campaigns by global brands such as Prada, Samsung, and Calvin Klein, exemplified by digital personas like Lil Miquela, whose social media presence rivals that of real-life influencers [6].

Despite their growing popularity, a significant gap remains in the systematic evaluation of VIs in brand endorsement. Much of the existing research relies on frameworks developed for assessing human influencers [7,8,9], often overlooking the distinctive characteristics of VIs—such as their synthetic origin, controlled personas, scripted narratives, and pronounced anthropomorphic features. Anthropomorphism, defined as the attribution of human traits to non-human agents, has been shown to shape consumer attitudes, trust, and behavioral intentions across various digital and robotic contexts. Consequently, applying human-centric evaluation metrics to VIs is inadequate. Several scholars have developed scales to assess consumer perceptions of non-human, virtual entities—such as the Robotic Service Quality Scale [10], the Brand Anthropomorphism Scale [11], and the AI Attitude Scale [12]—but these tools do not directly address the multifaceted nature of VIs.

To date, no studies in VI research have developed and validated a measurement scale for specifically gauging the effectiveness of a VI as a brand endorser. Thus, there remains a critical methodological and theoretical gap in developing a multidimensional scale that captures the distinctiveness of VIs as mediated brand personas. To address this gap, the present study aims to develop and validate a measurement scale for Virtual Influencer Effectiveness (VIE) through a scientific scale-development process. First, preliminary items are generated from adapting the relevant literature. Second, to assess the content validity of each item, the list of items is revised based on feedback provided by a group of experts. Third, an EFA is performed to identify underlying constructs. Last, a CFA is performed to validates the scale through confirming the structure and assessing the convergent and discriminant validity.

As VIs gain prominence in digital content creation—spanning brand endorsements, live commerce, education, and entertainment—a reliable measurement tool is crucial for evaluating their effectiveness. In addition, to contribute to the growing body of VI literature, a comprehensive measure is needed, one that not only examines how consumer perceptions of VIE are formed but also provides practitioners with better guidance for assessing VIE. Grounded in media and communication theory, the findings of the study are expected to offer a generalizable tool that captures the unique attributes of VIs, thereby advancing research on artificial agents, digital identity, and mediated consumer engagement.

2. Literature Reviews

2.1. Virtual Influencers

Research investigating the attributes of human, non-VIs has primarily focused on influencers’ attributes that influence consumer responses. These attributes include expertise and credibility, along with homophily—the perceived similarity between the information provider and recipient [13,14,15]. Additionally, perceived authenticity has been examined, defined as the degree to which consumers perceive the influencer’s messaging as aligned with their genuine beliefs and attitudes [15,16]. Their physical and social attractiveness has also been identified as a significant factor influencing positive consumer responses [17,18].

When evaluating the attributes of VIs, however, it is important to recognize that they possess distinctive characteristics that set them apart from human influencers. While early research on VIs drew upon established frameworks for assessing human influencers—such as expertise, trustworthiness, attractiveness, similarity, and authenticity—these attributes may not fully capture the nuances of VIs [19,20,21,22,23,24]. As artificially created entities, VIs are shaped by their synthetic design, programmed behaviors, and scripted narratvies, which influence how consumers perceive them [25,26,27,28]. Consequently, evaluations of VIs are not limited to human-centric traits but also involve dimensions specific to anthropomorphized digital agents. These include perceived human-likeness, the extent to which a VI visually or behaviorally resembles a human [19,20,21,22]; perceived humanity, which captures the warmth, emotional expressivness, or human-like qualities and cues attributed to the VI [29,30,31,32]; and perceived identity, which refers to the coherent, scripted persona that gives the VI a distinct and recognizable character [33].

Building on the above discussion, this study reviews anthropomorphism literature across domains and applies key components to conceptualize the unique anthropomorphic attributes of VIs.

2.2. Anthropomorphic Components of Virtual Influencers

Anthropomorphism refers to the attribution of human-like characteristics—including appearance, behavior, and psychological traits—to non-human entities [4]. This cognitive tendency allows individuals to perceive non-human agents as if they possess distinctly human capacities, such as emotion, intentionality, and cognition [4,34,35]. Such attributions are often triggered by design elements that evoke humanness, including the use of names [36,37], language capabilities [38], and physical features like eyes, limbs, and facial structures [39,40]. Central to anthropomorphism is the belief that human-like mental states underlie external cues; thus, when a non-human entity exhibits a human-like face or behavior, observers often infer the presence of internal states such as thought or emotion [35,40].

Anthropomorphism has been examined across various types of non-human digital entities, including AI conversational agents [41], virtual assistants [42,43], and service robots [44,45]. Recent studies have highlighted the ways in which anthropomorphic features influence user perceptions and engagement. For instance, Calahorra-Candao et al. (2024) found that anthropomorphic voice attributes in virtual assistants enhanced users’ perceived safety, which in turn increased their satisfaction with the online shopping experience [46]. Xie et al. (2023) identified four anthropomorphic cues in smart home AI assistants—visual, identity, emotional, and auditory—and concluded that emotional and auditory cues had the most significant impact on user satisfaction [47]. Similarly, David-Ignatief et al. (2024) and Klein and Martinez (2023) distinguished between physical anthropomorphism (e.g., human-like appearance) and non-physical anthropomorphism (e.g., perceived autonomy), both of which positively influenced users’ perceptions of likeability and credibility in chatbot interactions [48,49]. Building on this, Baltaci et al. (2024) proposed a framework for conceptualizing anthropomorphism in service robots: physical, functional, and internal. Physical anthropomorphism refers to human-like visual features such as facial structure and body form; functional anthropomorphism encompasses human-like behaviors, including verbal communication and emotional expression; and internal anthropomorphism involves the attribution of mental states, such as intentions, consciousness, and emotions [50]. These dimensions collectively inform how users perceive, interact with, and form relationships with artificial agents.

Taken together, these findings underscore the critical role of anthropomorphic attributes in shaping consumer experiences with digital agents. As VIs increasingly serve communicative and representational roles in branding and marketing, examining how anthropomorphic features shape consumer perception is essential for understanding their effectiveness and strategic value.

The significance of anthropomorphism—imparting human-like qualities to non-human entities—is widely recognized in VI research [51]. VIs, which range from cartoonish avatars to hyper-realistic human representations, incorporate various human-like traits. These traits may pertain to physical appearance (e.g., Miquela depicted as a young girl), behavior (e.g., Miquela dancing), or social interaction (e.g., Miquela engaging the audience through real-world dialogue). Beyond mimicking human appearance and body expression, VIs replicate real influencers’ social interactions [52]. As such, they frequently present themselves as authentically human, with a personality and backstory, expressing real emotions and developing intimate relationships with their audiences [33].

Recent studies have examined how the physical appearance of VIs shapes consumer responses. Pan et al. (2024) investigated varying levels of anthropomorphic realism and found that both cartoon-like and hyper-realistic VIs increased consumers’ purchase intentions [53]. In contrast, VIs with medium-realistic features reduced purchase intentions, suggesting the influence of the uncanny valley effect. Zourrig et al. (2025) explored the role of visual appearance in conjunction with perceived traits such as animism and warmth, demonstrating that these factors jointly enhance a VI’s social presence, which subsequently boosts purchase intentions [27]. Wang and Zhang (2025) introduced the concept of a “product dependent”, emphasizing that the alignment between a VI’s physical attributes, endorsement style, and the nature of the product significantly enhances its persuasive effectiveness [54]. In the context of anthropomorphism, a product dependent refers to specific design elements or functionalities of a product that trigger human-like perceptions based on the product’s intended use or category.

The functional aspects of anthropomorphism in VIs have been the focus of growing scholarly attention. Liu and Wang (2024) and Vo et al. (2025) noted that VIs perceived as highly human—particularly traits like trustworthiness and autonomy—significantly strengthen their parasocial relationships with consumers, ultimately enhancing brand loyalty [55,56]. Davlembayeva et al. (2025) identified key functional attributes such as warmth, interactivity, competence, empathy, uniqueness, fairness, and credibility as critical drivers of consumer engagement with VIs and endorsed brands [57]. In the context of social commerce, Wang et al. (2025) demonstrated that the emotionally arousing language used by VIs—designed to evoke excitement and emotional stimulation—positively influences consumers’ purchase intentions [58]. Similarly, Deng et al. (2025) reported that human-like sensory cues, particularly auditory signals, heighten emotional arousal and foster parasocial interactions [59]. Drawing on emotional contagion theory, Jiang et al. (2025) found that non-verbal cues such as smiling significantly influence affective and cognitive empathy toward VIs [60]. Sattar et al. (2025) emphasized that human-like personality traits—such as shyness or confidence—can enhance social media engagement and contribute to consumers’ psychological well-being [61].

While the existing literature offers valuable insights into specific anthropomorphic attributes, it often lacks a systematic categorization of anthropomorphic features in the context of VIs. Most studies tend to examine isolated physical or functional traits without situating them within an integrated conceptual framework. Thus, establishing a structured typology of anthropomorphism is crucial for enhancing theoretical clarity and informing future empirical investigations.

Anthropomorphic Forms of VIs

The anthropomorphism of VIs is reviewed as a superordinate construct consisting of several distinct yet related substantive components. Anthropomorphism is composed of these subcomponents. Previous studies have divided the subcomponents of anthropomorphism into distinct forms of anthropomorphism and empirically analyzed how the morphological elements of anthropomorphism are applied to digital objects and what effects the applied forms of anthropomorphism elicit.

Anthropomorphic forms are categorized into structural, gestural, aspects of character, and aware anthropomorphism [62]. Structural anthropomorphic forms mimic the structure and operation of the human body. Gestural anthropomorphic form mimics human communication and behavior through motions or poses that convey meaning, intention, or instruction [62]. While structural anthropomorphism refers to the resemblance of the human body and its components, gestural anthropomorphism draws from knowledge of human non-verbal communication and reflects the expressiveness of the human body [62]. A structural and gestural anthropomorphic form enhances audiences’ perception of physical realism by referencing the visual and physical similarity of digital entities to real individuals (e.g., human facial features and body movements). However, when such entities surpass the accepted norm due to unrealistic or uncommon traits (e.g., disproportionate facial features, unnatural body movements, lip-sync errors, or static eyes), they can evoke feelings of discomfort, unease, disgust, or even fear, a phenomenon known as the uncanny valley [63].

The third type of anthropomorphic form is the anthropomorphic form of character, which refers to the degree of resemblance to unique characteristics that only humans can possess, such as qualities, social roles, habits, or functions [62]. It draws on societal conventions and contexts, reflecting the practices and behaviors individuals engage in [64,65]. An example of the character-based anthropomorphic form is a way of representing human-likeness that symbolizes its characteristics such as masculinity, hospitality, professionalism, and so on. For instance, the KFC mascot, Colonel Sanders, dressed in a classic white suit and black bowtie, represents traits such as southern hospitality and tradition. Similarly, the Michelin Man, described as stacked tires with a confident facial expression, embodies qualities such as durability and reliability. These characteristics can be conveyed through attire, gestures, and expressions, all of which reflect interpretations that are often culturally constructed and derived from societal conventions.

The fourth category of anthropomorphic form is aware anthropomorphism. It is defined by its emulation of the human capacity for thought, intentionality, and inquiry [62]. Evidence of this form is seen in characters that suggest they possess a knowledge of the self in relation to others, the ability to construct or manipulate abstract ideas, or the ability to actively engage with others. The aware anthropomorphic form is commonly observed in AI conversational agents, where AI systems are designed to mimic human intellectual behavior. These systems are programmed with abilities such as input recognition and processing, knowledge retrieval, learning and improvement, error handling, and user interaction, all while simulating natural communication with users. Previous research that developed scales to assess how individuals tend to anthropomorphize non-human agents focuses on measuring the degree to which people attribute human-like qualities, such as consciousness, intentions, free will, and the ability to experience emotions, to non-human entities [66]. The items in the scales reflect the attribution of aware anthropomorphism, capturing how individuals perceive these agents as having a “mind of their own” or human-like experiences and emotions.

Anthropomorphism involves attributing human-like qualities—such as consciousness and secondary emotions like shame or joy—to non-human entities [67]. While AI conversational agents do not experience emotions as humans do, virtual humans, including VIs, are designed to simulate emotional responses. This capability enhances user interaction, creating a more immersive and engaging experience. A key factor in VIs’ appeal is their ability to form emotional connections with users through humanized interaction and communication, addressing real-world emotional concerns [30,32,60].

Beyond anthropomorphism, storytelling plays a crucial role in strengthening engagement, relatability, and audience connection. A well-crafted narrative fosters parasocial relationships, making VIs feel more authentic and emotionally compelling to their followers [32]. Recognizing this, this study introduces the content factor as a key determinant of VIs’ likability, emphasizing the role of narratives—the unique storytelling elements that define each VI and shape their connection with audiences.

2.3. Narratives as Strategies of Anthropomorphism

A key aspect of Vis’ appeal is their ability to connect with consumers through a humanized emotional interaction [68]. To highlight these emotional connections, marketers craft narratives that showcase VIs’ unique identities and personalities. These personas are carefully developed through digital storytelling, designed to resonate with consumers [69,70,71]. Additionally, followers form parasocial relationships with VIs by engaging with the narratives they create. Like human influencers, VIs share everyday experiences, pose questions, and respond to comments, fostering a sense of connection with their audience. This strategic self-presentation strengthens the perception that VIs possess human-like abilities to think, plan, and act—traits traditionally associated with human agency [72,73]. Collectively, these strategies enable VIs to replicate the social and emotional dynamics of human influencers, thereby amplifying their overall impact.

The cultural and economic power of VIs is built through the communication strategies they employ and the dialogic relationships they manage with their communities [74]. Their messages can be strategically crafted to convey autobiographical narratives [33]. Lil Miquela is an example of how digital media strategies can be expertly leveraged to build a unique identity through an online community [75]. Her identity is crafted to represent postmillennial groups, portrayed as a “forever 19” multiracial, American female avatar of Brazilian descent living in LA. Her creators, Brud, have positioned her as both a fashion and music icon through collaborations with celebrities and luxury brands. Additionally, they have portrayed her as a social justice advocate, supporting causes such as youth justice, voter engagement, climate action, and the promotion of indie brands [76].

Narrative Strategies of VIs as Brand Ambassadors

Lil Miquela seamlessly integrates brand endorsements into her Instagram posts, presenting them as natural extensions of her digital life. By incorporating product placements into her daily experiences, she makes promotions feel organic, as seen in her collaborations with Prada and Samsung. She also emphasizes self-expression and diversity, reinforcing brands’ efforts to break stereotypes. In her partnership with Patagonia, for example, she highlights sustainability and climate awareness, advocating for responsible consumerism [75,76]. Similarly, Rozy, a virtual brand ambassador for the Shinhan Financial Group in South Korea, has gained public attention for her active involvement in eco-friendly initiatives and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) activities. Recognizing her influence, the Shinhan Financial Group appointed Rozy as its ESG ambassador to effectively communicate the company’s societal values, leveraging her distinctive appeal and engaging content to reach a broader audience.

As demonstrated by Lil Miquela and Rozy, the strategically crafted identities of VIs can be understood through the concepts of identity peddling and discordant storytelling [33]. Identity peddling refers to a strategy where influencers leverage the intrigue surrounding their identities by blending distinctive and engaging storytelling [33]. For example, Shudu Gram, the world’s first digital supermodel, represents a life of luxury, exclusivity, and style—values that align seamlessly with high-end fashion houses. By presenting this carefully curated persona, Shudu elevates the brands she endorses, appealing to audiences who aspire to sophistication and beauty [76]. Identity peddling is effective when the influencer’s identity mirrors the values and interests of the target audience. VIs, as brand endorsers, reflect consumer interests by embodying traits like individualism, social justice, or tech-savvy lifestyles. This alignment makes the endorsed brands feel more in tune with the audience’s worldview, fostering a deeper connection between the brand and the consumer.

On the other hand, discordant storytelling involves blending real and fictional narratives to create a sense of authenticity, despite the character’s artificial nature. This technique blurs the lines between reality and fiction, turning virtual identities into commodities that evoke emotions, increase visibility, and generate profit [33]. A prime example of this is Lil Miquela, who used discordant storytelling to create tension between her digital persona and the real world [76]. In 2018, she became embroiled in a feud with Bermuda, another VI. The conflict, which unfolded through Instagram posts, combined elements of real-world drama with artificial narratives, making it difficult for the audience to discern whether the rivalry was scripted or real [76]. While the storyline was fictional, it mirrored real-world emotions such as jealousy, betrayal, and competition. This discordance created a buzz around both characters, making them relatable despite their digital origins, demonstrating how virtual identities can evoke strong emotional responses, increase visibility, and drive engagement.

Consumers are inclined to follow influencers who align with their emotional and hedonic preferences, resulting in a mutually beneficial relationship for both parties [68]. This inclination is fueled by the perception that the preferred VIs are credible, honest, and trustworthy sources of information [68,77]. From a psychological standpoint, influencers satisfy consumers’ psychological needs for enjoyment, escapism, and emotional fulfillment [70]. Such emotional connections often lead consumers to actively engage with influencers through behaviors such as liking, sharing, and commenting. Furthermore, the narrative strategies used by VIs enhance brand endorsements by creating compelling, relatable stories that resonate deeply with consumers, making the product feel more personal and relevant to their lives.

Table 1 summarizes prior research on VIs in the context of digital marketing on social media, highlighting key dimensions and subcomponents relevant to their evaluation. Building on the reviewed literature, this study seeks to conceptualize consumer-centric dimensions of VIs as brand endorsers and to develop a reliable and valid measurement scale grounded in psychological assessment standards. To address this, the present study proposes a research question to specifically evaluate a virtual influencer’s effectiveness as a brand endorser.

Table 1.

Dimensions and attributes of VIs suggested in the literature.

Research Question: What is an appropriate measurement scale for evaluating the effectiveness of virtual influencers as brand endorsers?

3. Methods

3.1. Scale Development Procedure

The present study followed the step-by-step procedure suggested by Gerbing and Anderson (1988) and Netemeyer et al. (2003) to develop a measure of the VIE scale in brand endorsement [79,80]. To accomplish these objectives, this study is structured around the following four steps: (1) generating preliminary items based on a review of the literature and expert interviews; (2) conducting an EFA to identify the underlying factor structure of a set of observed variables; (3) conducting a CFA to evaluate the validity and reliability of the measurement model, testing a hypothesized model derived from theory or previous EFA results, and assessing the model fit using statistical indices [81]; and last, (4) conducting a second-order CFA to test whether the first-order constructs are theoretically related and can be explained by an overarching, more abstract construct.

While second-order CFA has been widely used in marketing communication research to model abstract constructs, its application in the domain of VI research remains limited. Previous work developed a scale to measure the perceived authenticity of social media influencers, focusing on human—not virtual—entities [7]. Other related efforts offered valuable frameworks in adjacent areas but do not directly examine VIs using hierarchical modeling approaches [10,11,12]. Thus, this study addresses an important gap by applying a second-order CFA to a virtual influencer context, contributing both methodologically and substantively to the literature.

3.2. Step 1: Generating Preliminary Items for Evaluating VIs as Brand Endorsers

3.2.1. Preliminary Itemization

For the preliminary research on developing an evaluation scale for VIE, email interviews with experts were conducted over a three-week period in June 2024. After compiling a list of experts with extensive practical or research experience in relevant fields, the selection included two researchers specializing in advertising and public relations on social media; two researchers specializing in AI, digital entities, and digital communication; and two practitioners with experience in digital content creation. The interview questions included the following: “How would you define a virtual influencer, if at all?”, “If you have come across a campaign featuring a virtual influencer, what was the topic or content of the campaign?”, and “What characteristics or attributes should a virtual influencer have to be effective as a brand endorser?” After responding to open-ended questions, interviewees were asked to list the key attributes that VIs should possess as brand endorsers. They were also encouraged to provide additional explanations for their selections when necessary. The attributes summarized in Table 2 were derived from these expert interviews. Based on their feedback, redundant or repetitive items were removed, and certain attributes were clarified or expanded for greater precision.

Table 2.

Dimensions and attributes of VIs suggested in the expert interviews.

3.2.2. Sample and Data Collection

Based on the findings from expert interviews and an extensive review of the literature, the measurement items were revised—ambiguous expressions were clarified, redundant items were removed, and new items were added as suggested. As a result, the initial pool of 51 items was finalized as the preliminary set. These procedures helped ensure the content validity of the scale.

After the preliminary items were set, an online survey was conducted by Embrain, a research company within the Micromill Group specializing in online panels for marketing and public research. The data were collected during the first week of November 2024, based on the population ratio by age in the Seoul metropolitan area, Korea. Before the survey, participants were given the following definition of virtual humans: digital human forms created using artificial intelligence and computer graphics technology, possessing identities like real humans and acting as influencers on social media. They were then asked whether they had encountered VIs at least once on any social media platform.

Participants who reported having encountered VIs at least once on any social media platform took part in the survey. A total of 423 subjects aged between 18 and 65 years completed the online survey. Multivariate extremes were identified in the 423 cases using the concept of Mahalanobis distance, and six cases with values above the baseline (χ2 = 297.83 [df = 54], p < 0.001) were discarded to ensure stability for further analyses. The statistical analyses were thus conducted on a total of 417 cases.

To help participants recall VIs more easily during the online survey, researchers selected Lu do Magalu, Lil Miquela, Barbie, Imma, Shudu, and Rozy, as these VIs frequently appeared in Google News search results for the keyword virtual influencer. From this group, Lil Miquela, Imma, Rozy, and Shudu were further selected based on their number of Instagram followers and human-like appearance. The researchers then introduced the VIs and their names to the participants in a randomized order before commencing the online survey. Participants were asked to recall a similar type of VI or select an example from the provided list. They then responded to statements assessing their thoughts and feelings about the chosen VI. All responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Table 3 presents the respondents’ demographic information.

Table 3.

Demographic information of the respondents (N = 417).

4. Results

4.1. Step 2: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) for Construct Identification

4.1.1. Initial Item Reduction

The data from the 417 samples were randomly divided into two parts [61,62]. To determine an adequate sample size for the EFA, the study adhered to established guidelines that emphasize both absolute sample sizes and item-to-response ratios [81,82]. Hair et al. (2010) recommend a minimum of 200 participants for a reliable factor analysis [81], while Rummel (1988) suggests an item-to-response ratio of at least 1:4 [82]. Mundfrom et al. (2005) further support ratios ranging from 1:3 to 1:20, depending on communalities and factor loadings [83]. Given that the scale under development included 51 items, a minimum sample of 200 respondents was necessary to meet even the item-to-response ratio (1:4).

The EFA was conducted using SPSS 29.0 with a sample of 208 participants—an appropriate size that satisfies both absolute and ratio-based criteria, thereby ensuring a stable and interpretable factor extraction. The KMO measure was 0.96, Bartlett’s sphericity test was 8393.48 (df = 1275), and the significance level was 0.000, confirming the existence of common factors for factor analysis. The correlation matrix table analysis showed that the correlation between the items was not higher than 0.8, so there was no multicollinearity problem.

A total of 51 items were subjected to principal axis factoring with varimax rotation. Four factors were extracted based on the criterion of eigenvalues greater than 1.00. Items with factor loadings below 0.50 were eliminated, as low loadings suggest a weak association with the corresponding factor and indicate that the item may not align well with any underlying construct. For instance, items such as “fun”, “refinement”, and “familiarity” demonstrated low factor loadings in the first latent construct and were therefore excluded. Additionally, items that cross-loaded—those with loadings greater than 0.40 on two or more factors—were also removed, as such an ambiguity makes it difficult to determine which latent construct they best represent. Examples include “liveliness” and “vividness”, which showed substantial loadings on multiple factors. Following this refinement process, four factors comprising 26 items were retained, collectively accounting for 62.23% of the total variance. Factor loadings for the retained items ranged from 0.51 to 0.76.

4.1.2. Construct Identification

Table 4 reports the result of the EFA. Factor 1, with an eigenvalue of 9.42, consisted of 10 items accounting for 18.48% of the total variance. These items assessed whether respondents perceived VIs as trustworthy, authentic, empathetic, friendly, logical, emotionally aware, capable of independent speech, engaging in direct conversation, and speaking in an emotional, warm tone. As these attributes reflect qualities valued in VI communication, this factor was named communication skills. Factor 2, with an eigenvalue of 8.89, comprised six items accounting for 17.43% of the total variance. These items measured the extent to which respondents felt that VI narratives aligned with cultural trends, revealed the VI’s identity, were scalable, transcended reality, reflected the interests of the current generation, and matched consumer preferences. This factor was named narrative strategies. Factor 3, with an eigenvalue of 7.88, included five items accounting for 15.44% of the total variance. These items assessed whether respondents perceived a VI’s appearance as mysterious, celebrity-like, attractive, distinctive, and contemporary. This factor was named visual appearance. The final factor, human-like movement, had an eigenvalue of 5.55 and accounted for 10.88% of the total variance. It measured respondents’ perceptions of the VI’s natural voice and tone, expressive facial and body movements, realism, and synchronized lip movements with speech.

Table 4.

Results of exploratory factor analysis.

4.2. Step 3: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for Scale Validation

4.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

For the CFA, a power analysis was conducted using G*Power to ensure adequate statistical power. Based on parameters of f2 = 0.15 (medium effect size), α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and 26 predictors, the required sample size was calculated to be 175. The rest of the sample (N = 209) for the CFA exceeds this threshold, indicating adequate power for detecting model fit and parameter estimates. Using Amos 30, a CFA was conducted with the rest of the sample (N = 209) to confirm the fit and validity of the four factors consisting of 26 items. First, a chi-squared test was performed to assess model fit. The result was statistically significant (χ2 = 532.97, df = 292, p < 0.001), with threshold values based on Hu and Bentler (1999)’s [63] recommendation. Similar to the EFA results, the four-factor model indicates a good model fit, with Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) values of 0.94, a comparative fit index (CFI) value of 0.94, normed fit index (NFI) value of 0.91, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value of 0.04, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value of 0.05. The analysis showed that all the model fit indexes were found to be in the acceptable range, so further analysis could be conducted.

4.2.2. Construct Validity

Based on the results of the CFA, we also assessed the reliability and validity of the measurement scale. The convergent validity was examined by checking both the composite reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted (AVE) of all measurements. Following convergent validity, the study examined items’ reliability for each latent factor. Cronbach’s α results indicated that the reliability of the measurement items for each factor was acceptable, ranging between 0.84 and 0.94 (standard α ≥ 0.70). To further examine the reliability and validity of the latent variables, the CR and the AVE were calculated and compared to criterion scores. As shown in Table 5, the CR values ranged from 0.85 to 0.94, and the AVE values ranged from 0.53 to 0.61, meeting the criterion that the CR values should be greater than 0.70 and the AVE values should be higher than 0.50 [61]. All factor loadings ranged from 0.65 to 0.82 and were all statistically significant.

Table 5.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

4.2.3. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity refers to how distinct a latent variable is from other latent variables. Discriminant validity helps to check how the constructs are empirically different from one another. For the discriminant validity of the constructs, the positive square root of the AVE for each of the latent variables should be higher than the highest correlation coefficient with any other latent variable [84]. As shown in Table 6, the AVE values were greater than the squared correlation coefficients between the respective variables and all other components, indicating that the measurement scale for the VI evaluation scale developed in this study has sufficient discriminant validity.

Table 6.

Discriminant validity test.

4.3. Step 4: Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the VIE Scale

To validate the structure of the VIE scale, this study employed a second-order CFA. A second-order hierarchical model is appropriate as the overarching construct—VIE—is conceptualized as comprising four interrelated first-order dimensions: communication skills, narrative strategies, visual appearance, and human-like movement. This modeling approach is commonly used in scale development when a higher-order latent construct is theorized to underlie multiple correlated subdimensions [85]. The second-order CFA also allows for the assessment of both the individual contributions of each dimension and their collective representation of a broader construct [85]. In addition, it supports the construct’s validity by revealing the extent to which the second-order factor explains the variance in the first-order factors. This hierarchical structure provides a more parsimonious and theoretically coherent representation of the construct, which is advantageous for interpretation and further model testing in future research.

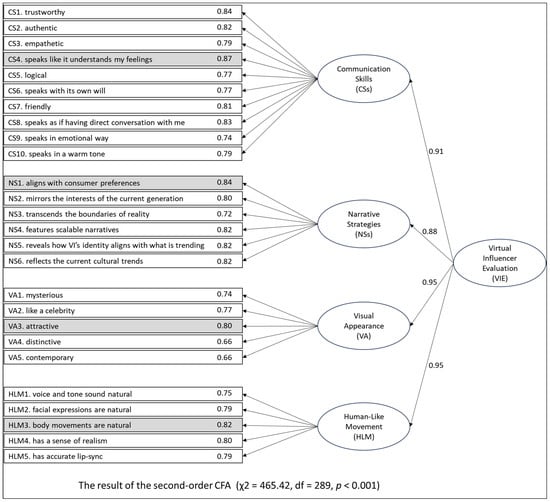

Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To develop a unidimensional scale, a second-order CFA (n = 209) was to conducted to draw a higher level of latent variable that conceptually included other lower levels of latent variables. The result of the second-order CFA indicated the goodness of fit (χ2 = 465.42, df = 289, p < 0.001), with a TLI of 0.95, CFI value of 0.96, NFI value of 0.90, SRMR value of 0.04, and RMSEA value of 0.05, indicating that all model fit indices fell within the acceptable range.

Following the execution of the model, the results also allowed for the selection of measurement items with the highest factor loadings for each first-order latent variable [85]. This made it possible for us to develop a four-item scale (α = 0.85), entitled the VIE scale (see Figure 1). The VIE scale developed and validated in this study consists of 26 items, including 10 items on communication skills, 6 items on narrative strategies, 5 items on visual appearance, and 5 items on human-like movement.

Figure 1.

The second-order model of the factor structure of virtual influencer evaluation.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion of the Results

This study aims to develop and validate a scale evaluating VIs as brand endorsers. A conceptual evaluation model was created through an integrative literature review and a pool of preliminary measurement items. These items were reviewed and refined via in-depth email interviews with six experts, resulting in 51 preliminary items. To assess validity and reliability, an online survey was conducted among Korean respondents (ages 18–64) who had encountered virtual influencers on social media. An EFA, based on 208 responses, determined the factor structure and item composition. A CFA, using 209 responses, confirmed the measurement model’s reliability and validity.

The VIE scale consists of four key components: communication skills, narrative strategies, visual appearance, and human-like movement. Communication skills determine how effectively VIs engage with their followers, encompassing attributes such as trustworthiness, empathy, thoughtfulness, logic, and independence in communication. While attributes such as logic and empathy are often seen as incompatible, users perceive VIs as conscious entities, fostering an emotional exchange through structured and responsive dialogue. Narrative strategies involve carefully planned storytelling that captivates audiences through personal experiences and episodic content. The results suggest that the effectiveness of VIs’ narratives is evaluated based on their ability to reflect cultural trends and consumer preferences, using scalable storytelling that resonates with the present generation, while transcending reality. Although communication skills and narrative strategies both involve interactive engagement, they function at different levels. Communication skills describe the influencer’s interpersonal effectiveness during interaction, such as responsiveness, emotional tone and manner, and conversational fluency, while narrative strategies refer to broader storytelling techniques used to build coherence and a persona over time.

Visual appearance refers to the overall aesthetic design of VIs, including facial features, body proportions, clothing, and hairstyles. This study highlights that while attractiveness is important, audiences value uniqueness and distinctiveness, seeing VIs as mysterious, celebrity-like, and contemporary figures. Finally, human-like movement focuses on natural and fluid motions that replicate real human behaviors, such as facial expressions, body gestures, and micro-movements. Attributes like a natural voice, accurate lip-syncing, and expressive motions play a crucial role in preventing the uncanny valley effect, where an almost-human figure evokes unease due to subtle inconsistencies in movement and facial expressions [6,86].

5.2. Theoretical Implication

The higher-order scale for VIE was developed and validated based on theoretical grounds that reconcile existing perspectives on anthropomorphism. The VIE scale developed in this study is significant because its components align with the four forms of anthropomorphism identified by Disalvo et al. (2005): structural, gestural, character, and aware anthropomorphism [62].

Attributes mentioned in communication skills are interpreted within the context of the anthropomorphic form of character. The display of traits or behaviors that define and describe VIs serves as evidence of the anthropomorphic form of character [4]. For example, a VI’s way of communicating—whether through friendly and informal language, professional and informative speech, or emotional and empathetic engagement—demonstrates specific traits (e.g., warmth, authority, humor).

The third component, narrative strategies, is noteworthy in this study, as a virtual human’s ability to construct narratives represents a more advanced level of anthropomorphism beyond merely having a physical human form [68]. Among the four forms of anthropomorphism, narrative strategies would fall under the aware form of anthropomorphism. Aware anthropomorphism reflects VIs’ ability to demonstrate human-like thought, intentionality, and social awareness [62]. Unlike character anthropomorphism, which highlights individuality, aware anthropomorphism emphasizes shared human experiences and interactions. VIs that express self-awareness, engage in meaningful discussions, or respond thoughtfully to societal issues exemplify this form [67]. For instance, Lil Miquela advocating for social causes, reflecting on personal growth, or addressing followers with empathy and understanding showcases aware anthropomorphism.

Attributes mentioned in the visual appearance and human-like movement component aligned with the concepts behind the structural and gestural forms of anthropomorphism [62]. Structural anthropomorphism refers to a human-like appearance, including realistic facial features, body proportions, and expressions. Gestural anthropomorphism replicates human communication through body language, emphasizing natural human behaviors. Structural and gestural forms of anthropomorphism that imitate human actions and appearance to convey meaning, intention, or instructions enhance the perception of realism in digital entities by making them appear more visually and physically lifelike.

The scale developed in this study is primarily tailored for evaluating hyper-realistic, humanoid VIs that closely resemble human appearance and behavior. However, certain dimensions—particularly communication skills and narrative strategies—may also be applicable to VIs with more stylized, anime-inspired, or minimalist forms. These elements of effectiveness transcend visual realism and focus on how VIs engage audiences and convey brand messages. Nonetheless, the applicability of dimensions related to visual appearance and human-like movement may be limited in such cases. Future studies could explore scale adaptations to better capture the distinct features of non-humanoid VIs.

5.3. Practical Contribution

The findings of this study offer actionable insights for brands seeking to integrate VIs into their marketing strategies. The VIE scale developed herein provides a valuable diagnostic tool, enabling practitioners to evaluate how effectively a VI aligns with a brand’s identity and engages with target audiences. By assessing a VI’s performance across key dimensions—communication skills, narrative strategies, visual appearance, and human-like movement—brands can determine whether a VI serves as a strategically appropriate brand ambassador.

In terms of communication skills, brands in the beauty sector may benefit from VIs who are perceived as trustworthy and authentic, fostering emotional resonance through relatable storytelling. E-commerce platforms like Amazon could enhance the online shopping experience by deploying assistant VIs with conversational features—delivering real-time recommendations in human-like tones to personalize customer interactions.

Narrative strategies offer cross-industry opportunities. Music entertainment and sports brands might deploy VIs who reflect generational interests and cultural trends. For instance, Spotify could introduce a VI as a music curator tailored for Gen Z, while Nike might utilize one to tell athlete stories that reinforce motivational themes. Brands like Red Bull could further leverage narrative capabilities by placing VIs in imaginative, high-adrenaline scenarios—such as extreme sports settings—offering immersive branded experiences that transcend conventional advertising.

When it comes to visual appearance, this study highlights that audiences are particularly drawn to VIs with unconventional designs or strong thematic identities. Fashion brands can capitalize on this by aligning VI aesthetics with their desired brand image. Luxury labels might develop VIs with high-glamour, celebrity-like features to convey exclusivity, while streetwear brands such as Supreme or Stüssy could adopt stylized, urban–futuristic designs that speak to youth subcultures. A distinctive visual identity not only captures attention but also supports storytelling and character development, reinforcing a VI’s role as a compelling digital figure.

Human-like movement, including realistic gestures and facial expressions, holds potential for enhancing engagement in technology and education sectors. Lifelike VIs can enrich virtual collaboration platforms or digital learning environments by making them more immersive and emotionally engaging.

Beyond these dimensions, this study underscores the need for continuous innovation. Managing agencies must remain attuned to emerging cultural trends, industry developments, and social issues to ensure VIs remain relevant. By anticipating future directions—such as evolving fashion trends or shifts in generational values—agencies can position VIs as trendsetters rather than followers. Moreover, VIs should possess adaptable storytelling frameworks for multi-platform deployment, as exemplified by Seraphine from League of Legends, whose narrative as a rising artist blurred the line between fiction and reality, sparking consumer intrigue.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers valuable insights, it has several limitations that future research can address. First, while the sample size for this study satisfies recommended thresholds for both EFA and CFA, larger samples would further enhance the generalizability and precision of the findings. Future studies could build on this by employing more diverse and larger sample sizes to validate the VIE scale across different populations and cultural contexts.

Second, this study focuses on four key dimensions—communication skills, narrative strategies, visual appearance, and human-like movement. However, anthropomorphism encompasses broader psychological and cognitive aspects, such as perceived intelligence, emotional depth, and concerns related to authenticity. Future research could incorporate these dimensions using theoretical frameworks like Epley et al.’s (2007) three-factor theory, which accounts for the cognitive, motivational, and social determinants of anthropomorphism [17].

Third, individual differences in audience characteristics—such as technological literacy or social connectedness—were not examined. For instance, individuals with a lower technological familiarity may evaluate VIs differently, and socially isolated users may form stronger parasocial relationships. These factors could influence perceptions and should be explored in future studies.

Fourth, cultural context presents an important but underexamined factor. While the selected VIs (Lil Miquela, Imma, Rozy, and Shudu) were chosen for their frequent appearance in Korean media to ensure familiarity, they originate from different cultural backgrounds. This raises the possibility that cultural incongruence may have influenced participants’ perceptions of attributes like authenticity, communication style, or visual appeal. Future studies should investigate how cultural familiarity and values (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism) affect audience engagement with VIs.

Lastly, this study does not account for the evolving capabilities of AI-driven VIs, such as self-learning and real-time interactivity, which could further enhance perceptions of human-likeness. Future research should explore these technological advancements to provide a more comprehensive understanding of anthropomorphism in VIs. Additionally, the ethical implications of using VIs as brand endorsers warrant further investigation as well. Research into how transparency in VI creation and authorship impacts consumer trust and engagement could offer valuable insights into the ethical boundaries of virtual endorsement.

With the increasing realism of VIs, it is essential to examine their role in marketing campaigns that blur the line between virtual and real personas. This research will be crucial for developing ethical guidelines and best practices for brands using VIs, ensuring their effectiveness while minimizing harm to consumers.

Funding

This work was supported by Kyonggi University Research Grant 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approvals were not required for this study, in accordance with the Personal Information Protection Act, Article 23 (study does not collect or record sensitive information and is not likely to significantly infringe on the privacy of the data subject, including information on ideology and belief, union or political party membership or withdrawal, political opinion, health, and/or sexual orientation).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dabiran, E.; Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Grant, G. Virtually human: Anthropomorphism in virtual influencer marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Ki, C.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y. Virtual influencer marketing: Evaluating the influence of virtual influencers’ form realism and behavioral realism on consumer ambivalence and marketing performance. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 176, 114611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungruangjit, W.; Mongkol, K.; Piriyakul, I.; Charoenpornpanichkul, K. The power of human-like virtual-influencer-generated content: Impact on consumers’ willingness to follow and purchase intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 16, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, S.E. Anthropomorphism: A definition and a theory. In Anthropomorphism, Anecdotes, and Animals; Mitchell, R.W., Thompson, N.S., Miles, H.L., Eds.; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Lee, Y.H. Unveiling Behind-The-Scenes Human Interventions and Examining Source Orientation in Virtual Influencer Endorsements. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Media Experiences, Aveiro, Portugal, 22 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Quan, W. Eeriness unveiled: A natural language processing investigation of co-presented human and virtual influencers on Instagram. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 21966–21980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Eastin, M.S. Perceived authenticity of social media influencers: Scale development and validation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 822–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Chan, K.J.; Lin, J.S. When social media influencers endorse brands: The effect of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. Intl. J. Adver. 2020, 39, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Nguyen, M. Robotic service quality—Scale development and validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golossenko, A.; Pillai, K.G.; Aroean, L. Seeing brands as humans: Development and validation of a brand anthropomorphism scale. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S. Development and validation of the AI attitude scale (AIAS-4): A brief measure of general attitude toward artificial intelligence. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1191628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, L.; Bansal, R.; Pruthi, N.; Khaskheli, M.B. Impact of Social Media Influencers on Customer Engagement and Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Balabanis, G. Meta-analysis of social media influencer impact: Key antecedents and theoretical foundations. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 41, 394–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J. Authenticity model of (mass-oriented) computer-mediated communication: Conceptual explorations and testable propositions. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2022, 25, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. The effects of sponsorship disclosures, advertising knowledge, and message involvement in sponsored influencer posts. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 1502–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Hao, Z.; Li, X. The influence of streamers’ physical attractiveness on consumer responses. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1297369. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F. Understanding the role of technology attractiveness in promoting social commerce engagement: Moderating effect of personal interest. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.; Breves, P.L.; Anders, N. Parasocial interactions with real and virtual influencers: The role of perceived similarity and human-likeness. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 3433–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. Virtual influencers’ attractiveness effect on purchase intention: A moderated mediation model of the Product: Endorser fit with the brand. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 143, 107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, J. How humanlike is enough? Uncover the underlying mechanism of virtual influencer endorsement. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Humans 2024, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Sung, Y. The interplay between human likeness and agency on virtual influencer credibility. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2023, 26, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Kim, H.K. Fancying the new rich and famous? Explicating the roles of influencer content, credibility, and parental mediation in adolescents’ parasocial relationship, materialism, and purchase intentions. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, C.; Kiew, S.T.J.; Chen, T.; Lee, T.Y.M.; Ong, J.E.C.; Phua, Z. Authentically fake? How consumers respond to the influence of virtual influencers. J. Advert. 2022, 52, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A.; Muller, K. Consumers’ responses to virtual influencers as advertising endorsers: Novel and effective or uncanny and deceiving? J. Advert. 2023, 52, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Yan, X.; Jiang, Y. Making sense? The sensory-specific nature of virtual influencer effectiveness. J. Mark. 2024, 88, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zourrig, H.; Park, J.; Becheur, I. How does humanoid virtual influencers’ appearance convey social presence? The underlying process and path to purchase intention. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2025, 49, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kim, D.; E, Z.; Shoenberger, H. The next hype in social media advertising: Examining virtual influencers’ brand endorsement effectiveness. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1089051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; van Doorn, J.; Eggers, F.; Wieringa, J.E. The effect of required warmth on consumer acceptance of artificial intelligence in service: The moderating role of AI-human collaboration. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ham, J.; Eastin, M.S. Social media users’ affective, attitudinal, and behavioral responses to virtual human emotions. Telemat. Inf. 2024, 87, 102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zheng, J.; Luo, S. Green power of virtual influencer: The role of virtual influencer image, emotional appeal, and product involvement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Dickinger, A.; Kam Fung So, K.; Egger, R. Artificial intelligence-generated virtual influencer: Examining the effects of emotional display on user engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, E.; Lovegrove, R. Discordant storytelling, ‘Honest Fakery’, identity peddling: How uncanny CGI characters are jamming public relations and influencer practices. Public Relat. Inq. 2021, 10, 265–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y. Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 56, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morewedge, C.K.; Preston, J.; Wegner, D.M. Timescale bias in the attribution of mind. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskine, K.J.; Locander, W.H. A name you can trust? Personification effects are influenced by beliefs about company values. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Heafner, J.; Epley, N. The mind in the machine: Anthropomorphism increases trust in an autonomous vehicle. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 52, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J.; Folkes, V.S. Humanizing brands: When brands seem to be like me, part of me, and in a relationship with me. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Wang, C.; Wunderlich, N.V.; Brock, C. Understanding anthropomorphism in service provision: A meta-analysis of physical robots, chatbots, and other AI. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 632–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.; Zhao, X.; Ullman, D.; Malle, B.F. What is Human-Like? In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Chicago, IL, USA, 5 March 2018.

- Go, E.; Sundar, S.S. Humanizing chatbots: The effects of visual, identity and conversational cues on humanness perceptions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabed, A.; Javornik, A.; Gregory-Smith, D. AI anthropomorphism and its effect on users’ self-congruence and self–AI integration: A theoretical framework and research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Balakrishnan, J.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Das, R. Do chatbots establish “humanness” in the customer purchase journey? An investigation through explanatory sequential design. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 2244–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Schmitt, B.H.; Thalmann, N.M. Eliza in the uncanny valley: Anthropomorphizing consumer robots increases their perceived warmth but decreases liking. Mark. Lett. 2019, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, M.; Scott, M.L.; van Doorn, J.; Grewal, D.; Shanks, I. Service robots rising: How humanoid robots influence service experiences and elicit compensatory consumer responses. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calahorra-Candao, G.; Hoyos, M.J.M. The effect of anthropomorphism of virtual voice assistants on perceived safety as an antecedent to voice shopping. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 153, 108124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, P.; Liang, C. How does anthropomorphism improve human-AI interaction satisfaction: A dual-path model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-Ignatieff, A.; Buzeta, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Mouelhi, N.B.D. This embodied conversational agent looks very human and as old as I feel! The effect of perceived agent anthropomorphism and consumer-agent age difference on brand attitude. J. Mark. Commun. 2023, 30, 881–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.; Martinez, L.F. The impact of anthropomorphism on customer satisfaction in chatbot commerce: An experimental study in the food sector. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 23, 2789–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, F.; Baser, M.Y.; Celik, M. Attitude toward service robots in tourism and hospitality service setting: The effect of multidimensional anthropomorphism and technology readiness. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K. Close encounters of the AI kind: Use of AI influencers as brand endorsers. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, J.; Li, S.; Looi, J.; Eastin, M.S. Virtual humans as social actors: Investigating user perceptions of virtual humans’ emotional expression on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 155, 108161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Y. More realistic, More Better? How anthropomorphic images of virtual influencers impact the purchase intentions of consumers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 3229–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Product-independent or product-dependent: The impact of virtual influencers’ primed identity on purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 84, 104088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, R. Fostering Parasocial Relationships with Virtual Influencers in the Uncanny Valley: Anthropomorphism, Autonomy, and a Multigroup Comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 186, 115024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.; Tan, G.W.; Pham, N.T.; Truong, T.H.; Ooi, K. Promoting customer engagement and brand loyalty on social media: The role of virtual influencers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2025, 49, e80028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davlembayeva, D.; Chari, S.; Papagiannidis, S. Virtual Influencers in Consumer Behaviour: A Social Influence Theory Perspective. Br. J. Manag. 2024, 36, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Han, Y.; Kandampully, J.; Lu, X. How language arousal affects purchase intentions in online retailing? The role of virtual versus human influencers, language typicality, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 82, 104106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Kang, J.; He, L.; Xu, Y. Endorsing alone or with humans: Investigating the impact of virtual influencers’ presentation formats on endorsement effectiveness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Qin, M.; Deng, D.; Zhou, D. Smile or not smile: The effect of virtual influencers’ emotional expression on brand authenticity, purchase intention and follow intention. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 24, 962–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.A.; Haq, J.U.; Saleem, A.; Ahmad, W. Shyness vs Confidence: The Effect of Virtual Influencer Personalities on Social Media Users’ Well-Being and Addiction. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 42, 1088–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disalvo, C.; Gemperle, F.; Forlizzi, J. Imitating the Human Gorm: Four Kinds of Anthropomorphic Form. In Proceedings of the Future Ground, Design Research Society International Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 29 November 2004; Available online: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~kiesler/anthropomorphism-org/pdf/Imitating.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Ho, C.-C.; MacDorman, K.F. Revisiting the uncanny valley theory: Developing and validating an alternative to the Godspeed indices. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1508–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutuleac, R.; Baima, G.; Rizzo, C.; Bresciani, S. Will virtual influencers overcome the uncanny valley? The moderating role of social cues. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Akalis, S.; Cacioppo, J.T. When we need a human: Motivational determinants of anthropomorphism. Soc. Cogn. 2008, 26, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.; Epley, N. Who see human? The stability and importance of individual differences in anthropomorphism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellén, K.; Sääksjärvi, M. Development of a scale measuring childlike anthropomorphism in products. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.E.; Lee, S.Y. “You are a virtual influencer!”: Understanding the impact of origin disclosure and emotional narratives on parasocial relationship and virtual influencer credibility. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, H.; Kong, Q. An expert with whom i can identify: The role of narratives in influencer marketing. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 21, 972–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, S. Unlocking trust dynamics: An exploration of playfulness, expertise, and consumer behavior in virtual influencer marketing. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.; Wang, W. The virtual new or the real old? The effect of temporal alignment between influencer virtuality and brand heritage narration on consumers’ luxury consumption. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 42, 470–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.; Wegner, D.M. Feeling robots and human zombies: Mind perception and the uncanny valley. Cognition 2012, 125, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, C.; Campbell, C.L.; Plangger, K.; Ferraro, C. Unreal influence: Leveraging AI in influencer marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1721–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, D. The Fascinating World of Instagram’s ‘Virtual’ Celebrities. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20180402-the-fascinating-world-of-instagrams-virtual-celebrities (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Tiffany, K. Lil Miquela and the Virtual Influencer Hype, Explained. Vox. Available online: https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/6/3/18647626/instagram-virtual-influencers-lil-miquela-ai-startups (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Smith, E.R.; Sherrin, S.; Fraune, M.R.; Šabanović, S. Positive emotions, more than anxiety or other negative emotions, predict willingness to interact with robots. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Chuenterawong, P.; Lee, H.; Tian, Y.; Chock, T.M. Human versus virtual influencer: The effect of humanness and interactivity on persuasive CSR messaging. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Sharma, S.; Bearden, W.O. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rummel, R.J. Applied Factor Analysis; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M. The role of structural equation modeling in scale development. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2003, 10, 622–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.J.; Ahn, S.J. A systematic review of virtual influencers: Similarities and differences between human and virtual influencers in interactive advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).