Abstract

Short video applications have gained increasing prominence as pivotal channels for information acquisition and knowledge dissemination, capturing the attention of scholars. Despite the increasing interest in this area, a general investigation of the factors that facilitate users’ information adoption on TikTok remains insufficient. We combine the flow experience and information adoption theory to construct a novel theoretical model for investigating the antecedents of information adoption intentions within the realm of short video applications. A total of 386 data were collected from TikTok’s users and analyzed using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. The analysis of the data revealed that technology affordance (i.e., accuracy, serendipity, and perceived ease of use) and information quality influence users’ information adoption intentions via flow experience. Users’ interest-type epistemic curiosity can moderate the effect of serendipity on information adoption intentions. This study investigates the interactive effects of individuals, technology, and information on flow and information adoption intentions, offering implications for platform administrators, content creators, and government agencies to understand users’ information adoption.

1. Introduction

Since its inception, TikTok, as a video-sharing platform, has rapidly increased in popularity among younger users, positioning itself among the foremost social media applications globally [1,2]. TikTok, characterized by its unique video creation and sharing functionalities, has a rich presentation of information (text, images, video, etc.) and employs an algorithm-driven recommendation system to provide users with the information they need. The acquisition of information is a crucial motivation for users of TikTok [3,4,5]. Due to its unique content delivery and discovery mechanisms, users’ information behaviors on TikTok differ significantly from those on traditional social media, as reflected in their information adoption, including browsing, liking, forwarding, downloading, and commenting on information. However, limited scholarly attention has been paid to how users adopt information on TikTok.

First, existing research on information adoption mainly focuses on the users’ behavior in utilitarian contexts such as online health communities, Q&A forums, and e-commerce platforms [6,7,8,9]. Relatively few studies have examined information adoption behaviors on TikTok. To the best of our knowledge, the limited body of TikTok research concentrates on domains such as political discourse [10] and health communications [11], neglecting general patterns of information adoption on hedonic short video applications. However, users exposed to hedonic content—typically humorous, entertaining, and novel in nature—are likely to exhibit information adoption behaviors that differ significantly from those in more serious, utilitarian settings. For example, rather than relying on deliberate evaluation and systematic processing, users may be more influenced by emotional resonance, visual appeal, and momentary enjoyment when deciding to browse, like, share, or comment on content [12]. This highlights the need for further investigation into how users adopt hedonic information on platforms like TikTok. Second, previous research mainly employed frameworks such as the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) [13] and the information adoption model (IAM) to understand information adoption, emphasizing rational cognitive processes and utilitarian motivations (such as travel [14], electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) [15,16], and health-related motives [17,18]). These studies offer limited explanatory power for understanding information adoption on hedonic platforms, where user engagement is often driven by immersive and experiential factors. TikTok’s unique recommendation algorithms [19] further amplify pleasure-driven engagement through emotional arousal and continuous entertainment [12,20], necessitating theoretical models that account for such dynamics. To address these gaps, this study examines users’ information adoption on TikTok and introduces flow experience—a state of deep engagement and enjoyment—as a key psychological mechanism underlying this process. By doing so, it offers a novel, affect-driven perspective tailored to the unique context of hedonic short video platforms.

Specifically, on TikTok, users frequently report a distorted perception of time, often describing the experience as “five minutes on TikTok, one hour on Earth”. Csikszentmihalyi [21] conceptualized this phenomenon as a flow experience, a state of deep immersion and intrinsic enjoyment during an activity. While previous research has extensively examined flow in contexts such as video games [22], e-shopping [23], virtual reality technologies [24], and e-learning [24,25], the flow experience on short video platforms exhibits distinctive characteristics that warrant investigation. Unlike other digital environments, short video platforms utilize unique technological features to enhance flow: (1) vertical video formats and immersive interfaces heighten users’ sense of presence and engagement [2]; (2) algorithmic recommendations provide a continuous stream of personalized content, while diversified discovery mechanisms introduce serendipity and surprise [1]; and (3) rapid and convenient information access facilitates an optimal balance between challenge and skill, promoting sustained engagement over time [26]. However, empirical findings on flow in the context of short video platforms remain inconsistent. For example, while Yang et al. highlight the flow’s positive effects on enjoyment and satisfaction [19], Cheng et al. indicate its potential drawbacks, such as anxiety, impaired reflection, or reduced information retention [27]. Similarly, Oh and Sundar found that flow states might impair users’ reflection and absorption of information [28], whereas Occa’s research suggested that high-level flow can actually enhance information elaboration due to platform-specific characteristics [29]. These mixed findings highlight the context-dependent nature of flow and the necessity of developing theoretical models that account for platform-specific affordances. Furthermore, Shi et al. suggested that users’ flow experience was closely related to pleasure and satisfaction [30], which, in turn, shapes behavioral outcomes, such as users’ information adoption on short video applications. Taken together, these insights suggest that flow may serve as a key affective mechanism for understanding information adoption on hedonic short video platforms. Thus, this study incorporates the flow experience as a critical psychological mechanism that drives users’ intentions to adopt information on short video platforms. Accordingly, we propose the following research question:

RQ1. How does users’ flow experience influence their information adoption intentions on short video applications?

User attitudes and behaviors are shaped not only by external environmental stimuli but also by internal individual factors, such as personality traits, emotional states, and cognitive styles [31], which can result in varied experiences and behavioral outcomes [6]. In the context of short video applications, the digital environment, shaped by platform technologies such as algorithmic recommendation systems and immersive interfaces, enables personalized interaction, thereby enhancing user engagement [19]. High-quality, rich, and diverse content further amplifies users’ enjoyment and emotional involvement [12,32]. However, even when exposed to the same environment and content, users with different individual characteristics may experience and respond to information in markedly different ways [1]. Existing research on flow within short video applications has mainly focused on technological and social features, neglecting the complex interactions between information characteristics, user traits, and technology affordances [33,34]. To address this gap, this study adopts the “person–artifact–task” (PAT) model as a guiding theoretical framework for understanding information adoption. The PAT model, proposed by Finneran and Zhang [31], posits that the antecedents of flow experience can be characterized by three categories: person, artifact, and task, which interact with each other to shape users’ flow experience and subsequent behaviors. Guided by the PAT model, this study investigates how individual traits (person), technological features (artifact), and information-related activities (task) jointly shape users’ flow experiences and their information adoption intentions on short video applications. By doing so, we aim to provide a more integrated understanding of the psychological and contextual mechanisms underlying information adoption in hedonic digital environments.

Specifically, in the person category, we focus on individual curiosity, especially epistemic curiosity, a crucial trait that motivates individuals to seek knowledge and information. Epistemic curiosity, examined as the intrinsic motivation for acquiring knowledge or information, empowers individuals with energy and fosters high levels of involvement and enthusiasm in the pursuit of information [35]. While the existing literature indicates that curiosity is a pivotal aspect of flow experience, the specific impact of epistemic curiosity—intrinsically tied to knowledge acquisition—on flow experience remains insufficiently elucidated [36]. For the artifact category, we choose technology affordance, which refers to the potential possibilities that a platform’s technology offers to particular user groups in order to accomplish specific goals [37]. Users tend to perceive an enhanced sense of control when their goals can be achieved within the platform, leading to increased focus and inducing a state of flow experience [26]. However, it remains unclear whether this effect is modulated by other factors. And for the task category, our focus is on information quality, defined as users’ perceptions and evaluations of the available video content quality on platforms. The primary task for users of short video applications is to browse and access information. Users tend to comprehend information more effectively when presented with high-quality content, thus enhancing their engagement and flow experience. Building upon these considerations, the second and third research questions were formulated in our study:

RQ2. Do technology affordance, epistemic curiosity, and information quality affect users’ flow experience and information adoption intentions on short video applications?

RQ3. Do users’ epistemic curiosity and information quality moderate the impact pathway from technology affordance to flow experience?

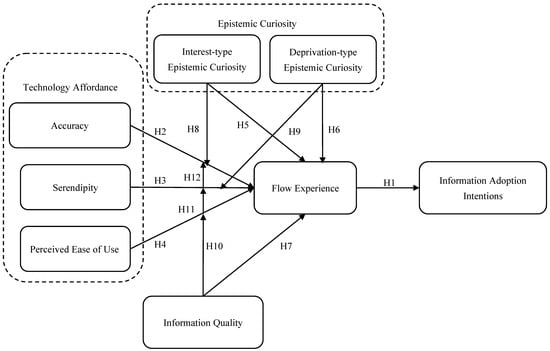

This study proposes an integrated model based on the PAT framework and flow theory (see Figure 1), offering several key theoretical contributions. Firstly, our study extends prior research on information adoption by shifting the focus to entertainment-oriented short video platforms. It highlights the flow experience as a central psychological mechanism, driving users’ information adoption in hedonic contexts—an area that has received relatively limited scholarly attention compared to more utilitarian information environments. Secondly, this research employs the PAT model to clarify the interplay among technology affordance, epistemic curiosity, and information quality in influencing flow experience and subsequent information adoption intentions on short video applications. By examining the antecedents and outcomes of the flow experience, this study broadens the field of research on flow experience. Thirdly, this study introduces users’ epistemic curiosity into the fields of information adoption and flow experience on TikTok. By differentiating the effects of interest-type and deprivation-type epistemic curiosity, it offers a more nuanced understanding of how different curiosity types shape user behavior on hedonic platforms, thereby contributing to a more refined and differentiated theory of epistemic curiosity.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Information Adoption on Short Video Applications

Information adoption is a process during which individuals analyze, evaluate, select, accept, and apply information, reflecting users’ recognition and positive feedback of information [38]. The development of information and communication technology has led to the emergence of online networks as important sources of information, prompting extensive studies on users’ information adoption. While existing research has identified multidimensional drivers through different theoretical frameworks, including platform environments [39,40], social factors [41,42], utilitarian factors [41], individual characteristics [43,44,45], and information itself [42,46,47], several critical limitations emerge when applied to short video contexts.

Firstly, although scholarly attention has shifted to the adoption mechanisms of short video applications, research on short video applications is still in its infancy compared with other applications (such as Zhihu and Weibo). For instance, Wang et al. examined how recommendation algorithms influence self-health management behaviors [48], and Zhang et al. applied dual process theories to explore emotional engagement in governmental videos [49]. Similarly, Wei et al. utilized fsQCA to analyze the combined effects of motivation, capability, and informational factors on health adoption behaviors [50]. However, these fragmented approaches overlooked broader information adoption across the entire platform. Secondly, existing studies on the mechanisms affecting users’ information adoption mainly emphasize utilitarian-based motivations, often overlooking the emotional engagement and hedonic motivations central to short video consumption. This limits the applicability of such findings to entertainment-oriented platforms, such as TikTok, in this study [51]. Although information quality remains a critical factor influencing users’ information adoption [50], other elements—such as the technology affordance of recommendation algorithms and users’ curiosity—also contribute to immersive experiences that influence behavior through flow states [11,35]. Yet, the synergistic effects of these factors on flow and subsequent information adoption remain underexplored.

To address these gaps, this study integrates flow theory and information adoption theory to examine the mediating role of flow experience in the information adoption process. By investigating the joint effects of technology affordance, information characteristics, and users’ curiosity, this research aims to uncover the psychological mechanisms underlying information adoption on short video applications and the pivotal role of emotional engagement.

2.2. Flow on Short Video Applications

The notion of the flow experience, introduced by Csikszentmihalyi, refers to the overall feeling a user has when fully engaged in an action [21]. When a user attains a state of flow, they lose potential control over the environment, becoming completely absorbed in a specific activity [21]. Within this state, users are more inclined to generate positive subjective evaluations, thereby enhancing their attitudes toward platforms and information [19]. The computer-mediated environment facilitates the generation of the flow experience, prompting a substantial amount of research dedicated to investigating user experiences within the realm of the internet.

Finneran and Zhang presented the “PAT” model as a framework to explain this phenomenon. This model includes three continuous stages: firstly, examining the determinants of the flow experience, including the individual (person), the technology or system employed (artifact), and the activity being performed (task), emphasizing their interrelated and joint impact on the flow [52]; secondly, generating the actual experience of flow, characterized by concentration, diminished self-awareness, a sense of time distortion, curiosity, and enjoyment; and finally, exploring the outcomes associated with the flow experience [52].

Drawing upon this model, numerous studies have investigated the antecedents and outcomes of flow in online contexts. For instance, platform technology, such as perceived ease of use [1,26], personalization [26], serendipity [19,34], and vividness [19,53], has been shown to facilitate flow by improving user interaction and gratification. Users’ personality characteristics [23,31], such as involvement [31], privacy concerns [54], and diverse curiosity [35], also influenced the likelihood of entering a flow state. Task-related factors, including content rivalry [31] or information quality [30], further shaped the immersive potential of an activity. However, most studies focused on isolated aspects, with minimal attention to their interactions. Meanwhile, for the research of outcomes, previous studies have indicated that the flow experience influences users’ cognition (e.g., health improvement, the perceived usefulness of information, and the utilitarian and hedonic values) [26,55], attitude (e.g., satisfaction, loyalty) [31,56], and behavioral intention (such as impulse buying, stickiness, and continued usage behavior) [19,32,34,55,56]. Yet, findings remain inconsistent: some studies associate flow with positive outcomes like continuous usage [19], while other pieces of literature proposing that the flow experience has the potential to impact user behaviors negatively [27,57].

Within the realm of short video applications, the separate effects of algorithmic perception and recommendation information characteristics are important antecedents of the flow experience [1,19]. Cui et al. proposed an integrated model to examine the impact of social factors (perceived expertise, similarity, and familiarity) and systemic factors (personalization, serendipity, and visual appeal) on flow experience and their subsequent effects on impulsive buying [34]. Other research has investigated addiction behavior [58,59], discontinuance behavior [60], and information behavior [30,61] on short video applications. However, the relationship between flow and information adoption remains underexplored.

Therefore, we propose elucidating the concept of flow experience on short video applications and the effect on users’ intentions to adopt information. Furthermore, utilizing the PAT model, this study investigates the joint impact of users’ personality characteristics, platform technology affordance, and information quality on their flow experience and information adoption behaviors.

2.3. Epistemic Curiosity on Short Video Applications

Epistemic curiosity, defined as the intrinsic motivation to seek and acquire knowledge [62,63], constitutes a fundamental human drive that propels individuals to resolve informational deficiencies and construct new understandings [64,65]. It serves as a fundamental aspect of human behavior that drives exploration, learning, creativity, and adaptation [66]. Litman created a conceptual model to distinguish the different types of curiosity, involving both deprivation-type epistemic curiosity and interest-type epistemic curiosity [67]. The deprivation-type epistemic curiosity is associated with perceived knowledge deficits and motivates information-seeking to alleviate discomfort associated with uncertainty [68]. This form is characterized by aversive emotional states (e.g., anxiety, frustration) that force individuals to mitigate cognitive dissonance. Interest-type epistemic curiosity is associated with the inherent pleasure derived from intellectual engagement and novel learning. This dimension manifests as positive affect (e.g., enjoyment, fascination) that reinforces exploratory behaviors through intrinsic reward mechanisms [69]. The dualistic model clarifies that while deprivation-type epistemic curiosity responds to informational needs, interest-type epistemic curiosity is actively sustained by the hedonic value of knowledge acquisition [22]. These contrasting motivational bases produce divergent behavioral and emotional outcomes [65].

Epistemic curiosity has been a focal point in different research areas, such as learning [70,71,72], working [73,74], gaming [22], information acquisition [65,75], knowledge seeking [35,76], and e-commerce reviews [64]. While prior literature has established that user personality traits are the crucial antecedents to the flow experience [52], the intrinsic motivation embodied by epistemic curiosity, a key driver for users in seeking information and knowledge, remains a critical personality trait. Epistemic curiosity, motivating knowledge acquisition, not only stimulates users’ interest in exploring information but also provides them with a sense of positive emotion, such as surprise and pleasure [68,71]. The diverse curiosity positively affects the flow experience and attitudes on social media [35,77]. Furthermore, previous research showed that curiosity was a significant factor in moderating the relationship between the stimuli and users’ psychological state and behavioral intentions [22,65]. Scholarly investigation into how epistemic curiosity impacts the flow experience, particularly within the realm of short video applications, is still limited. Thus, we posit that users’ epistemic curiosity is a pivotal antecedent in shaping flow experience and systematically examine its effect on the flow state and the moderation role in the relationship between the technological characteristics of the flow state.

2.4. Effect of Flow Experience on Information Adoption Intention

Flow experience significantly shapes users’ psychological processes, influencing their attitudes, emotions, and perceptions and contributing to alterations in users’ behavioral tendencies [19,55,56]. It has heightened satisfaction with social networks [60], increased continuous use intention [19], and has also been linked to phenomena such as social media addiction [57] and a greater willingness to consume [78]. When entering the flow experience, users undergo complete engagement, resulting in high enjoyment. This flow experience not only indirectly influences decisions by reducing other internal perceptions that influence individual responses but also directly shapes user decisions [79]. Meanwhile, experiencing a state of flow while receiving information has the potential to increase both the hedonic and utilitarian values attributed to the information [55].

Information adoption refers to the process wherein an individual systematically analyzes, assesses, selects, accepts, and employs information, reflecting a form of recognition and positive feedback to the information [38]. The information adoption intentions are shaped by various factors, including the information quality and the source credibility. Additionally, positive emotional responses, such as user trust and satisfaction, significantly enhance the user’s information adoption intentions [80]. The self-perception theory posited by Bem proposes that the subject tends to rationalize the behavior and mitigate cognitive dissonance, characterized by conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors [81]. When users experience a state of flow that creates pleasure and satisfaction while using a platform, their cognitive dissonance decreases, which amplifies the perceived value and usefulness of the information [55,82]. Consequently, we assume that users’ satisfaction and fulfillment significantly elevate when entering flow on short video applications. This heightened emotional state results in a more positive assessment of the information, thereby increasing the user’s information adoption intentions. We formulate the following hypothesis:

H1:

The flow experience of users will influence the information adoption intentions positively.

2.5. Effect of Technology Affordance on Flow Experience

The term “affordance”, originally introduced by Gibson, is defined as “what an object offers to someone or something” [83]. Within the realm of ecopsychology, it refers to the possibilities for action that the environment facilitates. Over time, this concept has gained significant traction across multiple disciplines, including psychology, media, communication [84], and information systems [85]. Building on this foundation, Markus introduced the notion of technology affordance within the information technology (IT) domain, which explains how technology can be used by specific user groups for the achievement of specific goals [37]. Despite its widespread application, there remains a lack of standardized classification methods in the existing literature.

Karahanna summarized previous research on social media affordances and proposed that different social media platforms offered distinct affordances to users due to their unique characteristics [85]. Given the technological diversity across digital platforms, the realization of technological efficacy must account for goal-oriented agents [86]. Specifically, Zhao and Wagner proposed that affordances should be analyzed from two dimensions: the capabilities and limitations of technology (i.e., understanding the probabilities they offer) and the needs of prospective users [1]. In the context of short video applications, distinctive technological features such as personalized recommendation services, full-screen autoplay formats, and short video content output are central to user engagement [2]. Users’ goals on these platforms typically involve consuming interesting content and acquiring relevant information [5]. Thus, our investigation into technology affordances should focus on the technology characteristics that facilitate content browsing, particularly recommendation algorithms and their methods of information presentation. There are two key elements of recommendation systems, i.e., accuracy and serendipity [87] that play crucial roles in shaping users’ experiences. Moreover, the TikTok application stands out for its exceptional user-friendly design; it initiates the playback of recommended videos automatically as users browse, eliminating the need for them to make choices based on extensive home page recommendations. Users can effortlessly browse between videos through a straightforward up-and-down scrolling mechanism. The cardinal principle in designing effective technological products is to minimize cognitive load—“don’t make me think”—ensuring users can effortlessly and intuitively accomplish tasks [2]. Hence, the simplicity of operation processes is an important reason for the success of TikTok. Therefore, the perceived ease of use constitutes a significant dimension of technology affordances, which refers to the extent to which users believe that employing a specific system would be effortless [88].

Accuracy refers to the degree to which recommended content is accurately aligned with users’ preferences [89]. The penetration of the internet has undoubtedly increased users’ information acquisition capabilities; however, it has generated an information explosion at the same time, often resulting in the fragmentation of information and diversion of attention. In the competitive landscape of internet products, capturing users’ attention has become a key strategy. To achieve this, it is important to provide content that corresponds with their preferences, as users have limited attention. Consequently, the more accurate the recommended information is, the more users’ attention focuses on the recommended information [90]. The concentration of attention constitutes a pivotal dimension of the flow experience. When users are more focused, they tend to enjoy the flow experience. Moreover, the pleasure derived from browsing preferred video content constitutes a pivotal aspect of the flow experience, as it not only fosters user satisfaction but also promotes the attainment of a flow state. Consequently, this research posits the following hypothesis:

H2:

Accuracy will influence users’ flow experience positively.

Serendipity is used to describe the degree to which a user deems a suggested video as surpassing their expectations and evoking a sensation of surprise [23]. The serendipitous content they receive could include novel concepts that they have not previously encountered, thereby stimulating their imagination, sense of wonder, and creative faculties at the same time. It captures their attention and brings a sense of timelessness, thereby fostering a state of flow [1]. Furthermore, the value of recommended information depends on its alignment with the user’s preferences. If the information is novel but fails to match the user’s preferences, it becomes less useful, making it challenging to create a sense of surprise and a pleasurable experience [23]. However, serendipity is distinct from mere novelty, as it specifically denotes the encounter with valuable and unexpected information during the search for information. The emphasis lies on the information’s inherent worth and its capacity to create surprise in users. On TikTok, users passively view content recommended by the platform, unaware of the forthcoming video [1]. When users view valuable content serendipitously, this experience will create a sense of surprise, arouse their curiosity, and foster their flow experience. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

H3:

Serendipity will influence users’ flow experience positively.

Empirical evidence from prior studies corroborated that users prefer platforms that are straightforward and intuitive to navigate. In instances where the platform operation is uncomplicated, users can direct their attention to the content itself, thereby reducing cognitive load and averting potential anxiety and frustration arising from excessive operational complexity. As suggested by Csikszentmihalyi, the balance between user skills and platform challenges, coupled with a sense of control, constitutes critical elements of the flow experience [21]. Conversely, when a platform proves challenging to use, users may experience difficulties in achieving a satisfactory alignment between their proficiency level and the platform’s complexity, leading to a diminished sense of control and impeding the attainment of a state of flow. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4:

Perceived ease of use will influence users’ flow experience positively.

2.6. Effect of Users’ Epistemic Curiosity on Flow Experience

Litman connected epistemic curiosity with an individual’s motivation, positing the interest-type epistemic curiosity as an intrinsic motivation (a task done for the joy or inherent interest in doing it) and the deprivation-type epistemic curiosity as an extrinsic motivation (a task done to achieve a separable outcome) [91]. Interest-type epistemic curiosity is largely consistent with pure, intrinsic motivation. Meanwhile, deprivation-type epistemic curiosity, with its reduction of unpleasant states of uncertainty, relates more to internalized extrinsic motivation, that is, extrinsic rewards that individuals internalize, perceiving them as an inherent aspect of the task. The diversity and heterogeneity of recommended content on the platform can encourage the interest and motivation of various users to explore video content [87]. Empirical evidence from prior research indicates that individuals with distinct personality traits go through diverse experiences in their information-seeking endeavors and enter different levels of flow experience. The pursuit of new knowledge not only heightens user interest and pleasure but also enriches their flow experience [23]. According to the self-determination theory, intrinsic motivation—the interest-type epistemic curiosity—will emerge as a fundamental factor driving human behavior and flow experience [35]. Secondly, elevated levels of interest-type epistemic curiosity have been shown to enhance user attention by activating pertinent brain areas [92]. Users with high interest-type epistemic curiosity become more engaged and focused when browsing videos. Additionally, individuals with high interest-type epistemic curiosity exhibit a broader range of interest preferences. The information suggested by the application is more likely to fit with user preferences and gives rise to feelings of surprise and pleasure, resulting in a heightened flow experience. Hence, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5:

The interest-type epistemic curiosity of users on short video applications will influence the flow experience positively.

Agarwal and Karahanna observed that the informational needs of seekers varied in type and composition based on their curiosity characteristics [93]. Specifically, deprivation-type epistemic curiosity entails a strong demand for information, propelling users to actively seek specific, objectively correct, and task-relevant information from the platform to moderate uncertainty [67]. According to the description of organismic integration theory, deprivation-type epistemic curiosity can be considered an identified motivation. It refers to behavior based on individual values and meaningful goals that are performed freely and autonomously [44]. This internalized motivation will drive users to a sense of immersion, bring the user into the content [70], and influence users’ psychological state and usage intentions [36]. Secondly, users characterized by pronounced deprivation curiosity are guided by the desire for information, and when utilizing the platform to acquire new knowledge, deprivation-type epistemic curiosity intensifies their thirst for information, fostering increased attentiveness, a clear target, and a heightened likelihood of entering into a flow experience [94]. Moreover, the acquisition of new information not only mitigates negative emotions associated with the uncertainty of pronounced deprivation-type epistemic curiosity users but also facilitates the learning of novel thoughts and bridges information gaps [65]. This reduction in uncertainty, coupled with the ensuing satisfaction, contributes to an enhanced flow experience. Consequently, we posit the following hypothesis:

H6:

The deprivation-type epistemic curiosity of users on short video applications will influence the flow experience positively.

2.7. Effect of Information Quality on Flow Experience

Short videos constitute the major content generated and disseminated on TikTok [95]. Accordingly, information quality in this context is defined as users’ perception and assessment of short video quality on TikTok [58]. Previous investigations have established a connection between high-quality information within a system and users’ perceived usefulness, satisfaction levels, and engagement intention with the platform [42]. If the information recommended by short video applications attains a high quality, users actively utilize the application for information acquisition. This can lead to an enjoyable absorption state that promotes a flow experience [23]. The format of a short video is very concise, only seconds to a few minutes [12]. Compared with long videos, they are more attractive because they fit the fast pace of life and users’ fragmented time [2]. Thus, users find it easier to concentrate on the short videos [58]. Furthermore, video presentations have a stronger sense of immersion, causing users’ flow experience. Users are more likely to direct their attention to the video content itself, concentrate on browsing information, and may lose track of time, particularly when the quality of information recommended by TikTok is exceptionally high [33]. In contrast, low-quality information exerts detrimental effects on users’ flow experience. This arises because users must expend additional time and mental resources to evaluate information quality, which imposes significant challenges on their cognitive capacities [96]. When such challenges exceed the balance point of users’ cognitive abilities, individuals are prone to disengage from the flow state. Hence, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H7:

The information quality of short videos on short video applications will influence the flow experience positively.

2.8. Moderating Role of Users’ Epistemic Curiosity

Individual characteristics are frequently utilized as moderating variables capable of systematically modifying and predicting the form and/or strength of relationships between variables [97]. Individuals characterized by interest-type epistemic curiosity primarily direct their focus toward acquiring knowledge and information in unexplored domains, thereby engendering pleasurable emotional responses [65]. Users with heightened interest-type epistemic curiosity exhibit a preference for browsing and discovering new information, gaining enjoyment and pleasure from the process of acquiring information and learning new knowledge. Their interest lies less in learning knowledge and information they are already familiar with, embodying the characteristic of an “information busybody” [98]. When users engage with short video applications to delve into information of interest, the unexpected encounter with serendipitous information intensifies the sense of pleasure and enjoyment, consequently enhancing the overall quality of the flow experience. Consequently, users displaying interest-type epistemic curiosity tend to be attracted by a more expansive scope of recommendations and a heightened level of recommendation serendipity. This heightened appeal leads to an augmented sense of pleasure and surprise. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H8:

Interest-type epistemic curiosity will enhance the effect of serendipity on the flow experience.

Deprivation-type epistemic curiosity is characterized by a persistent desire to seek information and a heightened concern over potential negative outcomes. Users experiencing this type of curiosity are driven by the uncertainty of unavailable information, creating a strong urge to resolve these gaps. Upon obtaining the desired information, they experience a sense of relief and pleasure as the uncertainty is alleviated. For these users, acquiring new information that aligns with their existing interests is particularly beneficial, as it not only reduces negative emotions related to uncertainty but also generates satisfaction and positive emotions [65]. These individuals focus on acquiring missing pieces of knowledge, often building a more focused knowledge network, like “information hunters” [76]. When browsing, they are more likely to engage with information that is closely related to their existing knowledge base, which heightens their engagement [98]. The acquisition of such information elicits positive emotional responses, which are intrinsically tied to the cognitive relief that comes from resolving knowledge gaps [71]. For users with deprivation-type epistemic curiosity, TikTok’s recommendation system plays a crucial role. Accurate recommendations reduce uncertainty and amplify the enjoyment derived from browsing content that aligns with their interests. This alignment not only facilitates information satisfaction but also enhances the user experience [55]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H9:

Deprivation-type epistemic curiosity will enhance the effect of accuracy on the flow experience.

2.9. Moderating Role of Information Quality

High-quality video content stands out as a critical factor in the widespread appeal of short video applications and positively affects users’ pleasure [30]. In comparison to low-quality videos, high-quality video content is more adept at capturing users’ attention and inducing a flow experience [33]. Consequently, it is reliable that the efficacy of technology may be compromised by information quality [58]. High-quality information directs users’ attention primarily toward content rather than technical aspects. Exposure to high-quality information significantly enhances user engagement and satisfaction [99]. Even if the recommended information fails to match the user’s preferences or arouse surprise, users still demonstrate a greater propensity to view videos and develop immersive experiences [33]. During this process, users exhibit an inclination to watch each high-quality video with reduced demands on platform operational convenience. Conversely, when platforms recommend low-quality videos, users must allocate more cognitive resources to assess information value [96]. At this moment, recommendation accuracy and serendipitous discoveries assist users in evaluating information value, thereby reducing cognitive load and enhancing satisfaction and immersion [2]. Furthermore, when the platform recommends a lower-quality video, the user is more likely to abandon the video, requiring a higher frequency of operations [1]. The perceived ease of use emerges as a significant determinant in shaping the user’s flow experience now. Thus, this study suggests the following hypotheses:

H10:

Information quality will weaken the impact of accuracy on the flow experience.

H11:

Information quality will weaken the impact of serendipity on the flow experience.

H12:

Information quality will weaken the impact of perceived ease of use on the flow experience.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Item Selection

To ensure the reliability of the questionnaire employed in this study, we carefully selected and employed rigorously validated scales [21,23,62,87,100,101,102] and adapted them to the unique specifics of our research context. Specifically, our investigation utilized the Likert seven-level scale as the primary measurement tool, ranging from “completely disagree” (1) to “completely agree” (7). Given that all participants in this study were native Chinese speakers, all items were translated into Chinese using a bidirectional translation method, ensuring linguistic accuracy and cultural appropriateness for data collection. Before the actual research, we invited 60 users on TikTok to make a preliminary survey and modified the wording based on the preliminary survey results, relevant research findings, and feedback from participants. All scale items and their corresponding references are listed in Appendix A.

3.2. Data Collection and Procedures

This research focused exclusively on TikTok in the Chinese context and limited its participants to China. Data collection was facilitated through the Credamo platform (https://www.credamo.com/#/, accessed on 15 October 2023), a dedicated and professional website for survey administration in China. For participant selection, we employed a convenience sampling method and mainly chose those who were willing to participate in the research, relying on the practicality and pragmatism of previous literature [19,103,104]. The questionnaire was created through the Credamo platform and generated as a hyperlink, which was subsequently distributed across various online communication channels. Participants were randomly recruited from over 15 provinces in China, all of whom had utilized TikTok previously. The survey process garnered online consent from participants and met the ethical requirements. Participants were explicitly informed of the voluntary and anonymous conditions, with guarantees that the collected data would be exclusively utilized for academics. Each participant received a reward after completing the questionnaire. To enhance data truth, we implemented an IP address restriction, limiting participants to a single questionnaire submission. At the outset of the questionnaire, the participants were required to respond to a predefined question: “Have you ever used TikTok?” Only those answering “yes” were eligible to proceed with the survey. Additionally, three screening questions were embedded in the questionnaire. Incorrect responses to these questions rendered the respective questionnaires invalid.

The survey continued for three weeks, resulting in the collection of 420 questionnaires. Rigorous screening measures were applied to the sample data, excluding questionnaires with excessively short response times, incorrect answers to validation questions, and those exhibiting obvious homogeneity in the responses. Finally, 386 valid samples were retained, with an effective recovery rate of 91.90%. Among the 386 samples, 189 users were male (48.96%), and 197 were female (51.04%). The participants mainly fell within the 21 to 40 years age bracket (77.20%). Additionally, 59.1% of users hold a bachelor’s degree, and 30.1% hold a master’s degree or higher. The participants were drawn from various regions of China, including the north (22.02%), east (34.2%), south (15.03%), northeast (6.48%), northwest (4.15%), southwest (9.33%), as well as the central (8.81%) regions of China. To assess the representativeness of our sample, we conducted a thorough comparison of participant characteristics with demographic data on the TikTok users’ survey report of Appgrowing and Disai. This survey report indicated that the proportion of male and female users was largely balanced [105], and the age distribution of users was predominantly concentrated between the ages of 25 and below (32.99%) as well as 26–35 (32.07%), which was similar to our samples [106]. The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in their distribution. Consequently, we believe that our sample exhibits a degree of representativeness. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the demographic characteristics of the validated sample.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the respondents.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

Initially, we employed Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) as reliability indicators for the questionnaire. The construct reliability and validity required Cronbach’s α and CR values to meet satisfactory criteria, which must exceed 0.7 [107,108]. As illustrated in Table 2, Cronbach’s α coefficients were between 0.751 and 0.913, surpassing the reference value of 0.7, affirming robust reliability across dimensions. Furthermore, the CR values consistently exceed 0.8, underscoring the high overall reliability of the questionnaire. Concurrently, this study measured convergent validity using the average variance extracted (AVE), which should be greater than 0.5 [109]. As illustrated in Table 2, all latent variables exhibit AVE values surpassing 0.6, indicating robust convergent validity. The discriminant validity was checked by the criteria fixed by Fornell and Larcker [108]. As shown in Table 3, the correlation coefficients between latent variables consistently fall below the square root of the AVE. Thus, the scale’s discriminant validity is generally satisfactory.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity analysis of items.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity of variables.

4.2. Testing the Measurement Model

To assess the justifiability and validity of our proposed model, we employed AMOS 27.0 software for model fitting. The threshold values of the model fit index are based on Hu and Bentler’s recommendations and evaluated by the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) [110]. The CFI and TLI are important, and their values need to be closer to 1. The outcomes, as shown in Table 4, indicate a high level of model fit, proving the overall robustness and satisfaction of our model. Subsequently, we conducted Harman’s one-way method to test common method bias. The results prove that the initial factor, without rotation, explains merely 44.54% of the overall variance, not reaching the recommended threshold of 50% [111]. This outcome affirms the absence of substantial common method bias in our study. Furthermore, Table 5 presents the results of a thorough examination of multiple collinear problems within the model. The VIF values for all variables fell within the acceptable threshold of less than 5.0, corroborating the absence of multicollinearity concerns [112].

Table 4.

Fitting test of the model.

Table 5.

Results of VIF test.

4.3. Structural Model

4.3.1. Direct Effect Analysis

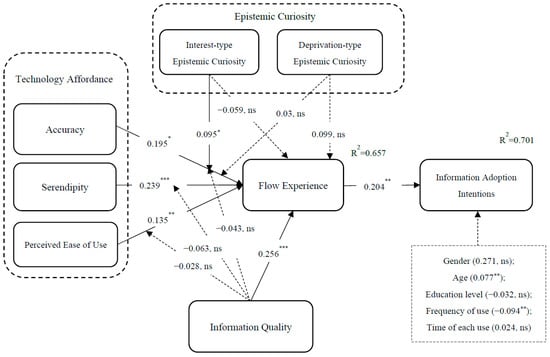

Our investigation employed SmartPLS 3.0 to examine the primary effects posited by the research hypotheses. The outcomes, illustrated in Figure 2 and Table 6, indicate that accuracy (β = 0.194, p < 0.05), serendipity (β = 0.239, p < 0.001), perceived ease of use (β = 0.135, p < 0.01), and information quality (β = 0.256, p < 0.001) exerted positive influences on the flow experience. Hypotheses H1–H4 gained empirical support. However, neither deprivation-type epistemic curiosity (β = 0.099, p = 0.146) nor interest-type epistemic curiosity (β = −0.059, p = 0.294) manifested a direct impact on the flow experience. Ultimately, our study established that flow experience (β = 0.204, p < 0.001) significantly contributes to information adoption intentions. Hypothesis H7 garnered support. Moreover, the model exhibited substantial explanatory power, capturing 65.7% of the variance for the flow experience and 70.1% for information adoption intentions.

Figure 2.

Structural model testing. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Table 6.

Hypothesis-testing results.

4.3.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

To further elucidate the impact of the three determinants associated with the flow experience on users’ information adoption intentions, we conducted a post hoc analysis employing a multi-group mediation test. The analysis and mediation effect assessments were executed using bootstrapping procedures (5000 samples) in SmartPLS. The utilization of confidence interval bounds is intended to check whether the indirect effects are statistically significant based on the criteria proposed by Preacher and Hayes [113]. The study’s results, detailed in Table 7, affirm the significant mediation effect. Specifically, the influence of accuracy (95% CI [0.009, 0.083]), serendipity (95% CI [0.015, 0.095]), and information quality (95% CI [0.017, 0.092]) on users’ information adoption intentions is indirectly mediated by the flow experience. And flow experience mediates the effect path from perceived ease of use (95% CI [0.006, 0.060]) to information adoption intentions completely. However, the effects of deprivation-type epistemic curiosity (95% CI [−0.007, 0.054]) and interest-type epistemic curiosity (95% CI [−0.04, 0.01]) are not statistically significant. This observation underscores the mediating function of the flow experience within the proposed model.

Table 7.

Results of mediation analysis.

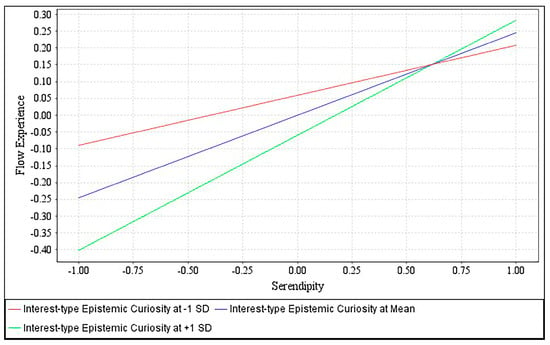

4.3.3. Moderating Effect Analysis

To examine the moderation effect within the model, this study employed SmartPLS to assess the moderating impact of epistemic curiosity and information quality. The detailed results are presented in Table 6 and Figure 2 and Figure 3, indicating that interest-type epistemic curiosity (β = 0.095, p < 0.05) amplified the impact of serendipity on the flow experience, supporting hypothesis H8. However, the result did not confirm the moderating role of deprivation-type epistemic curiosity (β = 0.030, p = 0.665) on “accuracy–flow experience”, and hypothesis H9 is not supported. Moreover, it is illustrated that information quality (βAcc = −0.043, p = 0.529; βSer = −0.063, p = 0.248; βPEU = −0.028, p = 0.477) did not moderate the effects of technology affordance on flow experience, and hypotheses H10–H12 are not supported.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of interest-type epistemic curiosity on “serendipity-flow experience”.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

We investigate the determinants shaping users’ information adoption intentions on short video applications that are exemplified by TikTok. Drawing upon Finnaman’s PAT model, we introduced and empirically tested our model for users’ information adoption intentions within the unique context of short video applications. The empirical evidence supports part of our proposed hypotheses (H1–H4, H7, H8), with only hypotheses H5, H6, and H9–H12 lacking empirical support. To summarize, the primary findings are as follows:

First, the findings indicate that flow experience is a key predictor driving users toward information adoption intentions. This aligns with prior research, consistently highlighting the positive influence of the flow experience [55,82]. Our study supports that users’ heightened focus on the information cultivates pleasure and positivity, enhancing information evaluation and fostering information adoption when they experience a state of flow.

Second, our findings support the profound impact of technology affordance on user flow experience within short video applications. Specifically, algorithm-driven personalized recommendations in short video applications enhance the perceived alignment of information with users’ preferences (high accuracy), fostering a positive flow experience for users characterized by heightened focus, enjoyment, and a sense of control. The introduction of unexpected recommendations (serendipity) on the platform attracts users’ attention and immerses them in video browsing. Furthermore, a full-screen auto-play feature for recommended videos, minimizing operational complexity (perceived ease of use), allows users to concentrate their attention on the video content and elevates their overall immersion.

Third, our findings affirm that information quality plays a pivotal role in shaping users’ flow experience within short video applications. Additionally, we attempted to indicate the moderation effect of information quality on the “technology affordance-flow experience”. However, our results contradict this. The possible explanations for this result are as follows: Although short video applications are increasingly used for information acquisition, users predominantly engage with them for hedonic purposes due to the platforms’ strong entertainment orientation [20]. Consequently, users tend to perceive these platforms more as sources of leisure than as serious information channels, which often leads to lower expectations regarding information quality. This hedonic usage may diminish the perceived importance of high-quality content, shifting user attention toward technological features that reduce cognitive effort or elicit positive emotional responses.

Fourth, users’ interest-type epistemic curiosity does not influence their flow experience directly but instead moderates the relationship between serendipity and flow. This result can be explained in two ways. Firstly, interest-type epistemic curiosity is characterized by a broad and sustained motivation to explore novel, interesting, or personally relevant content rather than fostering deep engagement with specific material. Compared with state curiosity, it is a relatively mild and persistent trait that drives users to continuously browse content without necessarily inducing intense cognitive or emotional absorption [67]. Secondly, as a moderator, interest-type epistemic curiosity can increase users’ sensitivity to and acceptance of unexpected discoveries. For users with interest-type epistemic curiosity traits, the emotional enjoyment and cognitive engagement brought by serendipity are significantly amplified. Serendipity is more likely to satisfy users’ curiosity, arouse users’ surprise, and bring pleasure and concentration, thereby enhancing their flow experience.

However, deprivation-type epistemic curiosity does not significantly influence flow experience or information adoption intentions, nor does it moderate the relationship between information accuracy and flow. This can also be interpreted from two perspectives. Firstly, users are more inclined to view hedonistic information on short video applications. Pleasure and enjoyment are prioritized by users on these platforms [20]. Nevertheless, deprivation-type epistemic curiosity is driven by a need to resolve knowledge gaps, an aversive avoidance motivation associated more with tension than pleasure [114]. This form of curiosity frequently involves systematic information-seeking behaviors [67], which are easily disrupted by algorithmic recommendations, limiting the continuity required for flow. Meanwhile, the fragmented and fast-paced nature of short video consumption makes it difficult for users to sustain the focus and deep immersion necessary for flow, especially when their curiosity demands in-depth exploration across multiple videos. Secondly, the emotional profile of deprivation-type epistemic curiosity is tension, anxiety, or discomfort, which conflicts with the positive affective and immersive states essential to flow [69]. Such negative emotions and cognitive strain may interfere with users’ emotional enjoyment and immersion during the exploration process, thereby reducing the generation of a flow experience. Meanwhile, recommendation algorithms on short video applications predominantly prioritize entertainment value and user preference history over epistemic need, aiming to provide content that users “want to watch” rather than “need to watch”. When users are driven by problem-solving goals, even highly personalized recommendations may fail to meet their expectations, leading to dissatisfaction or disengagement. Therefore, whether the user’s deprivation-type epistemic curiosity is strong or not will not influence the user’s flow experience and information behavior on TikTok.

Finally, a post hoc analysis revealed that flow experience acts as a complete mediator in the relationship between perceived ease of use and information adoption intentions. This finding indicates that the perceived ease of use affects the information adoption intentions solely by influencing the user’s flow experience. Moreover, accuracy, serendipity, and information quality influence users’ information adoption intentions by shaping their flow experience. The flow experience serves as a partial mediator in these relationships. The accuracy, serendipity, and information quality may influence users’ information adoption intentions through mediating factors other than the flow experience, which needs to be further explored. The integration of moderating and mediating effects reveals that users driven by interest-type epistemic curiosity experience heightened immersion when encountering serendipitous content. This curiosity amplifies the effectiveness of recommendation systems in fostering information adoption and deep engagement. By integrating these effects, this study elucidates how technology affordances (i.e., serendipity) interact with user traits (i.e., interest-type epistemic curiosity) to shape user experiences and information adoption intentions. Specifically, while serendipity indirectly promotes information adoption through flow experience, its effectiveness is contingent upon users’ curiosity-driven tendencies. This dual-layered model offers a nuanced perspective that accounts for both contextual and individual-level factors, advancing our understanding of user behavior on short video platforms. The findings suggest that the effectiveness of recommendation systems in promoting deep engagement and information adoption is contingent not only on content delivery mechanisms but also on users’ underlying cognitive motivations.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

Firstly, we integrate the flow experience and information adoption intentions theory to construct a theoretical model of users’ information adoption intentions on short video applications grounded in the PAT framework. Through empirical analysis, we reveal the mediating role of the flow experience, explaining a crucial relationship between users’ flow experience and information adoption intentions within short video applications. Prior research on users’ information adoption intentions mainly draws from the information adoption model [16,115], examining the effects of information and source characteristics from the cognitive path. While prior research has examined the adoption mechanisms of utilitarian information on such platforms, it has largely overlooked the significance of emotional fulfillment, which is critical for users on hedonic platforms. This study complements prior research that is largely centered on rational evaluations of utilitarian information by highlighting the role of flow experience in shaping user behavior on hedonic platforms.

Secondly, this study enhances the flow experience literature by exploring platform technology, information quality, and user personality traits as determinants. Prior research has focused on algorithmic and recommendation perspectives [19], overlooking the role played by personality traits and information characteristics. There has been no empirical investigation into the interactive effects of all three categories of factors proposed by the PAT theory. This study bridges these gaps and examines the direct and interactive impact of technology perception, personality traits, and information quality on flow experience. This study enhances the existing literature concerning flow experience and the PAT model.

Thirdly, this study offers novel insights into users’ epistemic curiosity, a factor insufficiently explored regarding information adoption intentions and flow experience [64]. By examining both the direct effects and the moderating role, this study clarifies how different types of epistemic curiosity interact with technology affordances. Specifically, interest-type epistemic curiosity, characterized by a sustained motivation to explore novel or personally relevant content, does not directly induce flow but significantly enhances the immersive and pleasurable effects of serendipitous content. This highlights its central role in shaping positive user experiences on hedonic platforms, extending its application beyond utilitarian domains, such as education and work, to entertainment-driven contexts. In contrast, deprivation-type epistemic curiosity, driven by a need to resolve information gaps, shows no significant influence on flow experience or information adoption intentions. This may be attributed to its aversive and problem-solving orientation, which is less compatible with the fragmented, entertainment-oriented nature of short video environments. Moreover, algorithmic content delivery often interrupts goal-directed exploration, further diminishing its relevance in promoting immersive experiences. These findings refine our understanding of how distinct curiosity types function across different platform contexts and contribute to a more differentiated theoretical framework.

Finally, this study offers a novel perspective on the determinants of users’ information behavior on short video applications, addressing gaps in previous research that focused predominantly on utilitarian information [10,14]. By integrating flow experience theory and the PAT model, this study reveals how epistemic curiosity, technology affordances, and information quality jointly influence users’ information adoption intentions. Furthermore, although prior research on utilitarian information, such as crowdfunding platforms and [116] Generative AI in education [117], has demonstrated that information quality significantly moderates the influence of various factors on users’ psychological and behavioral responses, this pattern appears less applicable to short video platforms. The comparatively low sensitivity to information quality and greater emphasis on emotional value in hedonic environments like TikTok reveal a distinct adoption logic, enriching the Hedonic-Motivation System Adoption Model (HMSAM) and offering deeper insight into user information behavior across entertainment-oriented platforms.

5.3. Practical Implications

Our research yields several managerial and content production implications:

First, for managers of short video applications, a pivotal focus should be placed on improving the quality of recommendation algorithms. Our findings highlight the importance of maintaining a dynamic equilibrium between recommendation accuracy and serendipity. While it is essential to meet users’ interest-based needs through precise personalization, platforms should also stimulate exploratory behaviors by incorporating controlled randomness, such as periodically introducing novel, diverse, or low-frequency content categories that align with broader user interests. This is particularly effective for users with high interest-type epistemic curiosity, as such users are more likely to experience immersive flow states and adopt new information when encountering unexpected yet relevant content. To further enhance algorithm performance, platforms can leverage behavioral signals (e.g., skipping behavior, exploratory viewing patterns) to identify users with curiosity-driven tendencies and dynamically adapt content delivery to match their psychological profiles. For new users, however, delivering accurate and relevant information may be more critical in establishing trust and encouraging continued use.

In addition to content delivery, platforms should optimize the interface design by streamlining operations, reducing cognitive load, and providing timely system feedback. These improvements enhance users’ sense of control and promote flow experiences. Furthermore, platforms should actively monitor content quality, reduce the exposure of low-value or misleading information, and promote high-quality content through refined tagging systems and personalized recommendation mechanisms.

Second, for content creators, this study confirms that information quality and not just entertainment value is a central driver of both flow experience and information adoption intention. Creators should prioritize meaningful, well-structured content that engages users cognitively and emotionally. While the direct impact of deprivation-type epistemic curiosity on flow is not substantial, efforts can be made to stimulate users’ sustained attention through suspenseful design (e.g., serialized content, previews of puzzles to be solved), which can be converted into long-term engagement dynamics.

Additionally, platform managers and content producers should be aware that while an increasing number of users access information through short video applications, the majority still consider it to be an entertainment platform rather than an important tool for acquiring knowledge and understanding news and other information. Therefore, platform managers and content producers should be committed to promoting the development of knowledge and professional news on TikTok. They should provide platform users with higher-quality, authoritative, and credible information. This will transform short video applications from being solely entertaining social platforms to spaces that offer both entertainment and professional content.

5.4. Social Implications

Firstly, the findings of this study indicate that the accuracy and serendipity of the platform’s recommendations significantly influence the user’s flow experience. This finding underscores the necessity of achieving a balance between exploratory and accurate algorithm designs. Algorithmic systems should be developed not only for maximizing engagement but also with well-being and digital responsibility in mind. It is suggested that managers may prudently adjust recommendation accuracy by adopting “efficient and humanized” algorithmic frameworks, thereby effectively alleviating the information cocoon effect while fostering diversified knowledge dissemination.

Secondly, while flow is generally associated with positive outcomes, such as deep engagement and increased information adoption, it can also lead to unintended consequences, such as excessive screen time, compulsive usage patterns, and reduced self-regulation [58]. The immersive nature of short video environments, coupled with personalized and serendipitous recommendations, may exacerbate users’ tendency to lose track of time and over-consume content. This is particularly concerning for younger users or those with lower self-control, for whom flow-induced engagement could shift from beneficial absorption to problematic overuse. Platform managers should recognize this dual nature of flow and implement protective design features, such as screen time reminders, usage dashboards, and customizable content limits, to help users maintain healthy digital habits.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study, grounded in the theory of flow experience, proposes an integrated model to explore users’ information adoption intentions on short video applications. However, several limitations exist, deserving further investigation. First, this study examined the direct impact of flow experience on information adoption intentions, neglecting the underlying mechanisms of the flow experience’s influence. Future research should investigate how and when a flow experience impacts information adoption intentions, enriching the understanding of the effect of the flow experience. Second, we only collected data from Chinese users to test the theoretical model; however, economic and cultural factors may influence users’ information adoption intentions. Future research could invite users from various economic and cultural backgrounds to participate in the research, examine the research models in other countries and short video applications, and enhance the understanding of the dynamics influencing users’ information adoption intentions in a global context.

6. Conclusions

This study explored the determinants of users’ information adoption intentions on short video platforms through the lens of the PAT model. The results highlight flow experience as a key mechanism mediating the effects of technology affordances, such as recommendation accuracy, serendipity, and ease of use, on users’ adoption intentions. Information quality also enhances flow but does not moderate the impact of technology, likely due to the platform’s entertainment orientation. This study further distinguishes the roles of two types of epistemic curiosity: interest-type epistemic curiosity amplifies the positive effects of serendipity on flow experience, whereas deprivation-type epistemic curiosity shows no significant impact. This highlights the importance of aligning platform design with users’ emotional and exploratory tendencies rather than problem-solving motivations. Theoretically, this research extends the flow and information adoption literature by integrating emotional and cognitive dimensions within a unified PAT-based model, addressing prior gaps in hedonic platform contexts. It also contributes to a more nuanced understanding of epistemic curiosity in digital environments, offering a differentiated view of how personality traits interact with algorithmic features. This study offers theoretical support and management insights for the operational and content production aspects of short video platforms, which can be used to enhance the user’s experience through the optimization of algorithms and video content.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.Z. and Y.Y. (Yang Yang); software, Y.Y. (Yang Yang) and Y.Y. (Yiwei Yuan); validation, Y.Y. (Yang Yang), Y.Y. (Yiwei Yuan), and S.Z.; investigation, Y.Y. (Yang Yang); data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z. and Y.Y. (Yang Yang); writing—review and editing, S.Z. and Y.Y. (Yiwei Yuan); visualization, Y.Y. (Yang Yang); supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement items.

Table A1.

Measurement items.

| Constructs | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 1.1 On TikTok, each of the recommended videos is relevant | [87] |

| 1.2 On TikTok, the videos recommended to me match my preferences | ||

| 1.3 On TikTok, the recommended videos are suitable for me | ||

| Serendipity | 2.1 There is a lot of valuable content, more than what I want to know when I use TikTok | [23] |

| 2.2 I often find interesting and surprising content in TikTok videos | ||

| 2.3 I am often surprised by the TikTok recommended videos that I never found, and they are interesting and helpful to me | ||

| 2.4 I can often see unexpected content in the TikTok videos that I am interested in or are helpful to me, and I have a feeling of surprise | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use | 3.1 TikTok allows me to find my favorite videos quickly. | [100] |

| 3.2 TikTok makes it more convenient for me to watch videos. | ||

| 3.3 TikTok allows me to watch videos anytime and anywhere | ||

| Deprivation-type Epistemic Curiosity | 4.1 I frequently seek out opportunities to challenge myself and grow as a person. | [62] |

| 4.2 I am always looking for experiences that challenge how I think about myself and the world. | ||

| 4.3 I view challenging situations as an opportunity to grow and learn. | ||

| 4.4 I am at my best when doing something complex or challenging | ||

| 4.5 I actively seek as much information as I can in new situations | ||

| Interest-type Epistemic Curiosity | 5.1 I am the kind of person who embraces unfamiliar people, events, and places. | [62] |

| 5.2 I prefer excitingly unpredictable jobs. | ||

| 5.3 I like to do things that are a little frightening. | ||

| 5.4 Everywhere I go; I am out looking for new things or experiences. | ||

| 5.5 I am the type of person who really enjoys the uncertainty of everyday life | ||

| Flow Experience | 6.1 Browsing and watching TikTok videos would be a very enjoyable experience for me. | [21] |

| 6.2 Browsing and watching TikTok videos will make me enjoy the process. | ||

| 6.3 Browsing and watching TikTok videos makes me feel like time flies. | ||

| 6.4 Browsing and watching TikTok videos will keep me engaged. | ||

| Information Quality | 7.1 The quality of the short videos available on TikTok is satisfactory. | [101] |

| 7.2 TikTok offers a diverse selection of short video content. | ||

| 7.3 The short videos on TikTok are interesting. | ||

| Information Adoption Intention | 8.1 After watching the recommended short videos on TikTok, I am open to accepting the points of view expressed in them. | [102] |

| 8.2 I am willing to share or retweet videos recommended to me by TikTok. | ||

| 8.3 I am willing to add this video to my favorites after watching it on TikTok | ||

| 8.4 I am willing to watch other TikTok-recommended videos. |

References

- Zhao, H.; Wagner, C. How TikTok Leads Users to Flow Experience: Investigating the Effects of Technology Affordances with User Experience Level and Video Length as Moderators. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 820–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Analysis on the “Douyin (Tiktok) Mania” Phenomenon Based on Recommendation Algorithms. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 235, 03029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falgoust, G.; Winterlind, E.; Moon, P.; Parker, A.; Zinzow, H.; Chalil Madathil, K. Applying the Uses and Gratifications Theory to Identify Motivational Factors behind Young Adult’s Participation in Viral Social Media Challenges on TikTok. Hum. Factors Healthc. 2022, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.S.; Leung, L. Factors Influencing TikTok Engagement Behaviors in China: An Examination of Gratifications Sought, Narcissism, and the Big Five Personality Traits. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Koo, C.; Kim, J.K. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation for Using a Booth Recommender System Service on Exhibition Attendees’ Unplanned Visit Behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, Z. Information Adoption Behavior in Online Healthcare Communities from the Perspective of Personality Traits. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 973522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, M. Online Information Adoption about Public Infrastructure Projects in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Dewani, P.P.; Behl, A.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Understanding the Impact of eWOM Communication through the Lens of Information Adoption Model: A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Ai, S.; Li, N.; Du, R.; Fan, W. The Influence of Social Q&A Systems on Consumers’ Purchase Intention: An Empirical Study Based on Taobao’s “Ask Everyone”. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 36, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Ji, X.; Wang, F. Zhengwu duanshipin neirong yulehua dui yonghu xinxi caina xiaoguo de yingxiang yanjiu [Research on the Entertainment Characteristics of Government Short Videos and Their Influences on Users Information Adoption]. Xiandai Qingbao 2023, 43, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhao, Y.C.; Yao, X.; Ba, Z.; Zhu, Q. Serious Information in Hedonic Social Applications: Affordances, Self-Determination and Health Information Adoption in TikTok. J. Doc. 2021, 78, 890–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, Y. Like, Comment, and Share on TikTok: Exploring the Effect of Sentiment and Second-Person View on the User Engagement with TikTok News Videos. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2024, 42, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.W.; Siegal, W.S. Informational Influence in Organizations: An Integrated Approach to Knowledge Adoption. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapanainen, T.; Dao, T.K.; Nguyen, T.T.H. Impacts of Online Word-of-Mouth and Personalities on Intention to Choose a Destination. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 116, 106656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Prakash, G.; Gupta, B.; Cappiello, G. How E-WOM Influences Consumers’ Purchase Intention towards Private Label Brands on e-Commerce Platforms: Investigation through IAM (Information Adoption Model) and ELM (Elaboration Likelihood Model) Models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 187, 122199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Acikgoz, F.; Du, H. Electronic Word-of-Mouth from Video Bloggers: The Role of Content Quality and Source Homophily across Hedonic and Utilitarian Products. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Yi, M.; Hu, M. What Facilitates Users’ Compliance Willingness to Health Information in Online Health Communities: A Subjective Norms Perspective. Online Inf. Rev. 2024, 48, 1252–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]