Abstract

This study investigates how consumers’ information-seeking motivation and perceptions of cross-media campaigns influence their attitudes toward innovative products. Drawing from the perspective of interactive marketing, it highlights the role of consumer–brand interaction in shaping product evaluation and acceptance. The findings indicate that when consumers perceive a product as highly innovative, they tend to experience both curiosity and uncertainty. This activates their need for information-seeking, which subsequently increases their engagement with cross-media campaigns designed with interactive marketing elements. Through this process, consumers develop more favorable attitudes toward the product. The results also reveal a significant dual mediation effect between perceived innovativeness and product attitude, mediated by the need for information-seeking and perception of cross-media campaigns. Although each path may not independently reach significance, the combined sequential mechanism—where consumers actively explore and interact with brand content—plays a critical role in shaping product attitudes.

1. Introduction

Recently, several companies have accelerated the development of new products based on innovation, such as by adding innovative features to products or developing products in categories that have never been introduced. The market is already home to numerous competing products; therefore, innovation is often chosen to differentiate new products. Innovative products, including differentiation, have extended beyond traditional categories such as automobiles and electronics to beauty products and daily necessities [1]. Consequently, consumers are now frequently exposed to information about these innovative products through various forms of media. While product innovation can be a point of differentiation, persuading consumers to purchase an innovative product they have never used before is a different issue [2]. Most consumers who lack prior information regarding these innovative products find it difficult to evaluate their performance [3] and may also be concerned about incurring higher learning costs [4]. In other words, while innovative products may offer interesting and beneficial features not previously available, they also carry perceived risks, resulting in a mix of positive and negative attributes [5].

Contrastingly, products that consumers consistently prefer require less cognitive effort for in-depth evaluation, and they are less sensitive to the evaluation context [6]. This is because prior knowledge regarding these products has already been formed, eliminating the need for complex alternative evaluations and external searches. Consequently, an important question arises: can consumers feel as secure about innovative products as they do about their long-standing favorites? Widely accepted innovative products, such as Dyson’s Supersonic Airwrap and Apple’s Smart Watch, emphasize this possibility. For instance, Apple’s Smart Watch has maintained a strong market presence since its initial launch in 2015, achieving sustained success through iterative enhancements and the integration of advanced features, culminating in the release of the Series 10 in 2024. Similarly, Dyson’s Airwrap, introduced as a subsequent innovation following the launch of Supersonic, has garnered positive consumer reception, further strengthening the brand’s reputation for pioneering hair styling technology. The brand’s success is partially owing to the stable perception linked to well-established brand images, fostering a solid trust in its continuous innovation. These cases provide significant insights into how innovative products can achieve and sustain market success. Initially unfamiliar to consumers, these products may also present perceived risks. However, they share a common innovative differentiation that attracts consumer curiosity and attention, utilizing extensive cross-media campaigns based on interactive marketing to help consumers continuously discover differentiated products. This exposes consumers to the unique design of the Supersonic and its hair styling methods, thereby encouraging them to seek more information and feel a sense of familiarity with the product. The need to seek information can lead consumers to actively search for information or pay attention when exposed to it [7]. Ultimately, customers can find information such as product reviews or better ways to use these products. Therefore, this process of acquiring information plays a role in alleviating consumers’ anxiety about innovative products and emphasizes the importance of cross-media campaigns—a marketing strategy that enables diverse interactions with consumers [1]. Consumers with high innovativeness are characterized by a tendency to place a higher value on innovative differentiation than on price, yielding a lower sensitivity to price compared to consumers with low innovativeness [8,9]. This characteristic explains the willingness of early adopters, who are ready to pay a high price for valued innovations. Despite the high cost of innovative products from brands such as Apple and Dyson, they continue to receive considerable attention from many consumers, largely because of the diverse reviews from these early adopters. In the case of innovative products, real user reviews are crucial, and constitute essential content that must be exposed to consumers during their information search.

With innovative products being developed in various categories, reducing symbolic, functional, and emotional uncertainty about these products is a critical issue to be explored in the development and diffusion process of new products [10]. According to Park, Jaworski, and MacInnis [11], functional uncertainty can be mitigated through marketing strategies that emphasize product quality and performance. This includes objectively demonstrating the performance of new products through methods such as product testing and expert reviews. In the case of Dyson, when launching the Supersonic Hair Dryer, the company systematically utilized online and offline promotional strategies to enhance brand awareness and facilitate a successful market introduction. To objectively verify the product’s performance, Dyson held a large-scale product unveiling event in Tokyo, where founder James Dyson personally introduced Supersonic’s innovative technology and design [12]. This event not only garnered significant attention, but also helped to validate the product’s performance through reviews by high-tech reviewers beyond just beauty influencers, reinforcing consumer trust in the product’s capabilities (e.g., South Korea’s million-subscriber YouTuber Guigom). Meanwhile, regarding symbolic uncertainty, this study highlights branding strategies that enable consumers to attain a specific social status through the brand. Examples include the release of limited-edition products or the establishment of exclusive distribution channels. In Dyson’s case, although the brand is available through various sales channels, it has strategically positioned itself as a “luxury hair dryer purchased in department stores”, reinforcing its premium branding strategy [13]. As a result, consumers continue to perceive Dyson as a premium haircare brand. Additionally, emotional (experiential) uncertainty can be alleviated through strategies that allow consumers to experience the product firsthand and increase their satisfaction. Representative examples include experiential marketing and the formation of communities where consumers share their product experiences. In practice, Dyson has implemented experiential marketing strategies since its initial launch and continues to do so by establishing experience zones in premium department stores and flagship stores, allowing consumers to try the product firsthand and experience its differentiated performance. Dyson continues to provide detailed product information through its official website, while also incorporating features that allow consumers to share their reviews and experiences. This strategy enables potential buyers to more easily access objective consumer feedback. Through firsthand experiences or user reviews, consumers can reduce emotional uncertainty. Furthermore, Dyson has built an integrated social media marketing strategy, actively utilizing Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. Specifically, Dyson has collaborated with beauty influencers to provide credible reviews and user-generated content (UGC), enhancing consumer interaction and trust-building. On YouTube, Dyson has produced advertising content explaining product features and usage methods, improving consumer understanding. Additionally, Dyson has employed product placement (PPL) strategies in TV programs, featuring celebrities naturally using the product, thereby maximizing brand awareness and consumer preference. With its trustworthy innovation in the hair device market, Dyson’s success with Supersonic laid a strong foundation for the subsequent launch of Airwrap and other innovative products, maintaining a solid bond with consumers.

In response, competitors such as Shark FlexStyle aggressively marketed their products using slogans such as “Why pay $600 when you can get the same styling for half the price?” However, once a strong customer–brand bond is established, it is not easily dismantled. Wang [14] did not consider this phenomenon in isolation, but argued that innovative products are powerful tools for driving interactive marketing. This is because innovative products enhance direct interactions between customers and companies or brands. Consumers who have experienced these products voluntarily share their experiences, further strengthening the customer–brand relationship. Thus, Dyson, which maintains a strong bond with consumers based on interactive marketing, continues to lead in the hair device category in brand recognition and purchase intention [15]. Although competitors also claimed to offer similar innovative technology and adopted Dyson’s marketing strategies, they did not pursue their own unique innovation. Instead, their campaigns focused solely on “getting Dyson’s benefits at a lower price”, which ironically reinforced the consumer perception that Dyson is the original innovator in hair devices. This case highlights that when marketing an innovative product, a strategic approach tailored to the innovation itself is crucial for success.

Most existing studies concerning the adoption of new products have focused on individual innovation tendencies, resistance to innovation, and the innovativeness of the product itself (e.g., type and degree of innovation), often basing their research on the receptiveness of the target audience to the product. However, focusing on the consumer acceptance process is essential in order to successfully establish innovative products in the market by using them as a differentiation point. This study employs real-life examples of innovative product launches to examine how positive attitudes toward innovative products are formed. Furthermore, these attitudes can be enhanced through interactive marketing, which fosters customer–brand relationships. This bidirectional communication approach is a crucial element of modern marketing, particularly for digital platform-based campaigns [16]. It is particularly important in products such as innovative goods, which require a bond with consumers. Consequently, this study examines the impact of consumers’ information-seeking behavior on the acceptance of cross-media campaigns based on interactive marketing, and how this process contributes to the formation of attitudes toward innovative products.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Perceived Innovation of New Products

Perceived innovation is the creation and acceptance of new ideas, processes, products, or services perceived as new by firms or customers [10]. This innovation can be either incremental or radical [17]. Radical innovation is characterized by technological discontinuity (e.g., moving directly from gasoline to electric cars) or market discontinuity (creating an entirely new market with innovative technology). Contrastingly, incremental innovation involves enhancing or renewing existing product features or technologies without disruption. Regardless of whether it is radical or incremental, innovation influences consumers’ need for information-seeking [10]. Consumer reactions may vary depending on whether the innovation is radical or incremental; however, in both cases, the need for information-seeking is an important driver for increased search behavior [18]. In other words, just the perception of innovativeness can enhance the need for information-seeking. Lee and Min [1] stated that innovative products stimulate curiosity, thereby boosting the need for information-seeking, while Mitchell and Harris [19] also confirmed that high perceived innovativeness increases the need for information-seeking to reduce learning costs.

Thus, it is relatively easy for companies to stimulate consumers’ curiosity and information-seeking needs simply through the innovativeness of the product, leading to the development of products with either radical or incremental innovation. However, there are other risks involved. Innovativeness in new products can evoke positive and negative emotions among consumers. Kyriakopoulos [20] argued that innovative products, being unproven, possess inherent risks and uncertainties, and these perceived risks can negatively impact acceptance and decision-making, leading consumers to increase their information-seeking behavior to reduce perceived risks. Similarly, Manning et al. [4] noted that the perceived risk associated with innovative products, while offering novelty and freshness, also brings risk and anxiety, leading consumers to seek more information in the context of evaluating and purchasing these products to reduce psychological risk and anxiety.

When consumers perceive a high level of innovativeness in a product, they are motivated to actively seek information about it or pay heightened attention when exposed to it, activating their desire to seek information [7]. Underlying this is a psychological state driven by curiosity and a desire to reduce the lack of trust and uncertainty associated with the product.

Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1.

New products with high (vs. low) innovativeness increase consumers’ need for information-seeking.

2.2. Consumer Information Search and Need for Information-Seeking

Consumer information search refers to the process by which consumers seek, gather, and assess information about products or services prior to making a purchase decision [21]. This process is crucial in preventing erroneous purchasing decisions and aiding consumers in making optimal choices [22]. According to various studies, information search is typically divided into two types: internal and external searches [23]. Internal search utilizes information stored within an individual’s memory, whereas external search involves seeking new information through the Internet, store visits, and conversations with others [24]. This information search process can significantly impact consumer satisfaction and loyalty [25], particularly for innovative products with high levels of uncertainty, where it profoundly influences purchase decisions.

Innovative new products, characterized by mysterious and novel attributes, inherently involve technological uncertainty [26]. These attributes may lead consumers to experience not only symbolic and functional uncertainty, but also emotional uncertainty. Therefore, effectively reducing such uncertainties has emerged as a critical issue, and differentiated marketing communication strategies that mitigate these uncertainties are important [10]. As mentioned in the introduction, such differentiated marketing communication strategies are more effective when they are perceived by consumers through the lens of cross-media campaigns. Cross-media campaigns are strategies that deliver consistent messages across various platforms, and are based on differentiated marketing communication strategies that enable consumers to recognize and remember the product as distinct from competitors [27]. This makes them complementary to each other.

As consumers evaluate innovative new products based on their existing knowledge, in the absence of relevant schemas for new products or services, they inevitably pay close attention to the company’s advertisements, promotional activities, influencer reviews, and customer testimonials. Such information can lead consumers to engage in additional information-seeking activities. Therefore, innovative products communicate with consumers not only through advertising, but also via other communication tools, such as packaging, that symbolize the product’s identity. As exemplified by the packaging of Dyson and Apple, the design is aligned with the innovation and brand identity, intuitively conveying the product’s functionality and usability without needing a manual, thereby enhancing the unboxing experience to a premium level that reflects the product’s innovation and brand value. Furthermore, Apple’s use of minimalism and simplicity and Dyson’s emphasis on technological innovation and a premium image through their packaging also serve to reinforce brand identity. In conclusion, their packaging strategies are not only about wrapping, but are also crucial in directly communicating the product’s innovation and brand identity. Consumers use this information as cues to perceive the benefits of the product [5]. Additionally, when exposed to such information, consumers tend to interpret the product as delivering positive benefits, even without conducting an in-depth analysis [28]. In summary, cross-media campaigns across various platforms that make the differentiated communication of innovative products perceptible to consumers serve as crucial cues that stimulate consumers’ information-seeking behavior regarding the product.

Meanwhile, innovativeness can arouse curiosity and the perception of higher learning costs and potential risks compared to existing products [5], thus increasing the need for information-seeking to alleviate curiosity and anxiety. Curiosity represents expressing additional interest in a product, paying attention to what is being said about the product in one’s surroundings, and striving to find more diverse product information [29]. The perception of potential risks manifests in similar consumer behavior. Particularly in the case of innovative new products, consumers may consider potential risks related to functional, financial, and psychological losses. Functional risk arises owing to concerns regarding the validity of new technologies [30] or the possibility that the product may not perform as expected [31]. Financial risk is also a key concern, as most innovative products tend to be priced higher than existing market alternatives, leading to the potential for economic loss after purchase [32] or depreciation in product value if the innovation fails in the market [33]. Finally, psychological risk may emerge from the perception that using an innovative product requires a high learning cost [34], which can lead to anxiety or concern that the product may not provide the expected satisfaction [30]. Thus, both factors, inherent in innovative products, ultimately elevate the need to seek information, leading to active information searching and voluntary attention to a company’s marketing efforts.

In summary, new products with high perceived innovativeness can arouse consumer curiosity or perceived risk, generating a high need for information-seeking. Consequently, consumers voluntarily pay attention to different marketing content from companies or engage in active information-seeking.

Innovative new products, unlike existing ones, are often characterized by untested uncertainty in the market. Technological uncertainty, in this context, refers to concerns such as whether the innovative features of a product will perform as expected by consumers, whether it can deliver a complete and reliable service, and whether unintended adverse effects may arise from its use [20]. Consequently, consumers may perceive both positive benefits and potential drawbacks associated with innovative products. These drawbacks include the high learning costs stemming from innovation [5] and the dilemma of weighing up the desirability and undesirability of adopting the product [35,36].

Moreover, innovative products often demand usage methods that deviate significantly from conventional products, requiring consumers to render their previous tools or behaviors obsolete. This process of obsolescence can elicit negative outcomes for consumers, such as perceived risks, anxiety, and discomfort [37,38]. Such experiences can trigger perceived risk—consumers’ perception of uncertainty regarding unproven products—and this risk perception may exert a negative influence on decision-making during the adoption of innovative products [19,39]. Therefore, consumers actively seek more information prior to purchase to mitigate perceived risks [4].

The following question then arises: can such information-seeking behavior effectively reduce consumers’ perceived risks and positively influence their attitudes toward adopting new products? According to Hoeffler [17], when consumers do not fully comprehend a product, their cognitive processing may be adversely affected. For innovative products, where uncertainty and ambiguity are substantial, it becomes crucial for consumers to be exposed to sufficient information that enables knowledge acquisition. Such exposure may occur through corporate advertising campaigns, self-directed information searches, product knowledge acquisition, or consumer reviews.

Rogers [40] supports this perspective, arguing that, in the innovation adoption process, consumers must resolve uncertainties associated with replacing existing products with new ones, which necessitates significant amounts of information. Thus, the decision to adopt new technology begins with the knowledge phase. Only when this phase is adequately addressed can the adoption process advance to subsequent stages. At this stage, individuals become aware of the existence of the new technology, gain an understanding of how it operates, and acquire the necessary knowledge to facilitate adoption. In other words, individuals seek to acquire relevant knowledge to resolve uncertainty, leading them to engage in information-seeking behavior. This need for information-seeking not only motivates individuals to search for product-related information and voluntarily pay attention to various marketing content provided by companies, but also places them in a heightened state of attention. Goal-directed search behavior is based on the need to seek specific information [41]. This increased need for information can make consumers pay heightened attention to the product or service. Consumers exhibit high attention when encountering related information, owing to an elevated need to collect information [7]. Thus, because of the increased need for information-seeking, it becomes possible for consumers to voluntarily pay attention to various kinds of corporate content, including advertisements for specific products or services. Almeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil [42] illustrate how customers’ growing information-seeking desires lead them to acquire knowledge through various platforms and channels, thereby stimulating conversations between businesses and customers, and potentially fostering long-term trust connections. Thus, when information-seeking is needed, people may voluntarily pay attention to cross-media campaigns, including company advertisements [7]. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2.

A higher (vs. lower) need for information-seeking leads to increased exposure to cross-media campaigns.

2.3. Interactive Marketing

Interactive marketing is defined as a marketing process that creates value through interactions between businesses and consumers, distinguishing it from traditional one-way marketing approaches such as television, radio, and printed advertisements [43,44]. While the effectiveness of traditional media-centered marketing has gradually declined, interactive marketing—facilitated by digital and mobile innovations—enables more personalized marketing strategies, and has transformed consumer–brand relationships [45]. Consumers are no longer passive recipients of information; rather, they actively generate content about brands across various platforms, share their personal experiences, and play an increasingly participatory role in the marketing ecosystem.

According to Wang [45], the expansion of interactive marketing is driven by four factors: technology advancement, platform revolution, participatory culture and fandom communities, and the proliferation of social media. In this evolving landscape, interactive marketing has been studied extensively across various contexts, including the application of AR/VR/AI technologies [46,47], TikTok hashtag challenges [48], the impact of Instagram influencers’ follower counts [49], and brand engagement through live streaming [50]. These studies highlight the increasing significance of diverse platforms in fostering consumer engagement with brands.

The strategic application of interactive marketing is crucial for the market success of innovative products. Moore [51], building on Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory, introduced the concept of chasm, which represents the gap between the early market (comprising early adopters) and the mainstream market. The early majority, characterized by a pragmatic approach and a strong tendency to minimize risk, often hesitate to adopt high-uncertainty products, unless there are successful cases from early adopters to mitigate their concerns. Conversely, early adopters, often referred to as visionaries, are willing to embrace innovation to gain a competitive edge in the market. They not only accept the risks associated with new technologies, but also serve as opinion leaders who influence broader consumer segments.

For an innovative product to successfully penetrate the mainstream market, it is essential to establish an environment where early adopters actively promote the product’s advantages across multiple platforms and engage in interactions that facilitate acceptance among the early majority. These early adopters act as brand ambassadors, contributing to a smoother transition across the chasm by legitimizing the product’s value and reducing perceived risk among risk-averse consumers. Consumers generally tend to establish greater trust in UGC than in corporate-produced content, owing to its perceived authenticity and impartiality. This trust is particularly crucial in shaping consumer attitudes toward innovative new products that lack information and therefore have lower credibility. Content from individuals in similar positions—unlike enterprises that possess more information and intent—naturally fosters corporate–customer relationships. Furthermore, this interaction facilitates access to a broader reach through dynamic social networks, significantly enhancing the effectiveness of marketing efforts [52]. Guo et al. [53] suggest that consumers engage in webrooming and showrooming when purchasing high-risk products. Webrooming involves researching a product online before making a final purchase offline, while showrooming involves inspecting a product in a physical store before completing the purchase online. For beauty products categorized as high-risk experience goods, both webrooming and showrooming behaviors occur. Therefore, it is essential to encourage single-channel customers to explore alternative channels, reorganize offline-centric services that provide experiential opportunities, and proactively offer price, function, and related information through online channels.

Consequently, owing to the high levels of uncertainty and perceived risk associated with innovative products, consumers tend to adopt a cautious approach in their purchasing decisions. Therefore, a cross-media campaign strategy that effectively integrates online and offline channels is essential to reducing perceived risk and enhancing consumer confidence. A cross-media campaign strategy that unifies online and offline touchpoints ensures a consistent brand experience across all consumer interactions, regardless of the purchasing channel. By minimizing barriers to purchase and maintaining uniform messaging across platforms, companies can build consumer trust and improve the market adoption of innovative products. Consumer interaction is an essential component within this process. Recent research on interactive marketing in previously unexplored product or service categories demonstrates significant effects. For instance, Sun et al. [54] found that interactions in travel live-streaming, facilitated by real-time sensory imagery, can positively influence consumers’ intention to visit a location. Similarly, Lee and Ma [55] indicated that on an O2O platform related to vehicle diagnosis and repair, interactive marketing substantially influences visitation decisions. They highlighted that efficient information delivery during the diagnostic phase is critical for facilitating transactions. Additionally, Shen et al. [56] revealed that meme marketing, a vital interactive marketing tool, effectively improves consumer attitudes, particularly when brand memes align closely with brand values and concepts. However, research by Zhang et al. [57] on ridesharing services presents a nuanced perspective: social interaction effects may not universally enhance consumer engagement. While interaction channels such as reviews and online communities may be effective depending on product characteristics, interpersonal interactions focused on emotional bonding or relationship building may not always yield positive responses. This study examined the effectiveness of a cross-media campaign based on interactive marketing, particularly targeting innovative beauty products. In previous research, webrooming and showrooming were identified as significant factors. Accordingly, this campaign integrated both online and offline channels (omnichannel marketing), facilitating showrooming and webrooming behaviors. Additionally, various UGC was actively exposed to consumers through digital media. Traditional media channels, such as PPL on television, were also utilized. Beyond employing traditional media, this study established an interactive environment where users can share content within digital channels, fostering interactions between brands and consumers. Consequently, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3.

Higher (vs. lower) consumer exposure to cross-media campaigns based on interactive marketing will lead to the formation of a more positive attitude toward the product.

2.4. Cross-Media Campaigns

A cross-media campaign is one of the most representative strategies within multi-platform approaches. It represents a strategic approach to marketing communication, integrating multiple media channels to deliver a consistent message and engage consumers across various touchpoints [58]. By leveraging the unique strengths of each platform—such as television, radio, print media, digital platforms, and social media (see Table 1)—this approach aims to enhance brand visibility, drive consumer engagement, and maximize the effectiveness of marketing campaigns [59].

Table 1.

Overview of cross-media marketing channels.

By combining various media types, cross-media campaigns provide consumers with a unified experience, while emphasizing the maintenance of brand consistency across all channels. Such consistency builds consumer trust, strengthens brand identity, and enhances brand memorability [60]. By leveraging the unique strengths of each platform, this approach enhances brand visibility, facilitates consumer interaction, and maximizes the impact of marketing campaigns [61]. A previous study showed that consumers exposed to advertisements through a combination of media, such as television, Internet, mobile, and apps, had a higher willingness to accept single-medium or single-platform advertisements, with the group exposed to cross-media advertisements exhibiting higher levels of attention, message trust, positive thinking, and attitudes [62]. Previous studies demonstrating the advertising effects of cross-media campaigns [61,62,63] have validated the synergistic impacts of this marketing, focusing on its ability to enhance positive consumer attitudes, and showing enhanced ad and product attitudes and repurchase rates among consumer groups exposed to this type of marketing compared to others. Thus, higher awareness of cross-media campaigns contributes to the formation of positive attitudes, such as intention to share and brand familiarity, while also influencing positive attitudes toward the product by familiarizing consumers with the product’s trustworthiness, functionality, and convenience [64]. Jessen and Graakjær [65] demonstrated that cross-media campaigns utilizing online connection methods, such as website URLs or QR codes, within nationwide TV advertisements were more effective when consumers engaged with online content beyond the initial TV exposure. The study found that extending the advertising experience from TV to online platforms allowed consumers to acquire more information, thereby enhancing the campaign’s effectiveness. However, for this approach to be truly effective, maintaining a consistent brand message across different platforms was deemed essential. In other words, for a cross-media campaign to achieve its full potential, the communication strategy—including the messaging and the overall design—must be integrated across TV advertisements and websites.

Moreover, cross-media campaigns have a broader reach than traditional media advertising, and offer consumers opportunities for interactive communication through advertising media. This approach not only facilitates passive information processing, but also promotes active experiences and information acquisition. Specifically, traditional advertising channels (e.g., television, radio, and newspapers) are still recognized as effective tools for enhancing brand awareness and attracting customers [58]. Furthermore, they contribute to both online and offline sales growth, demonstrating a high return on investment (ROI) [66].

However, online banner advertisements and social media ads have a relatively limited impact [67]. These findings suggest that online display and social media advertising may only be effective at specific stages of the consumer purchasing process. To maximize their effectiveness, a refined targeting strategy is essential. In this regard, research increasingly highlights that cross-media campaigns are more likely to yield superior marketing performance than single-platform strategies, such as traditional media advertising or online advertising alone. According to Chang and Thorson [63], multimedia advertising is more effective in enhancing consumer attention, message credibility, and cognitive engagement than repeated exposure through a single medium. Furthermore, Voorveld et al. [68] found that repeated exposure to advertisements across multiple media channels reinforces advertising effectiveness and enhances brand credibility. Therefore, cross-media campaign strategies that leverage multiple media platforms stimulate consumer cognitive responses, strengthen brand trust, and ultimately maximize return on advertising investment (ROI), making them a more effective approach than single-channel advertising.

In summary, it can be observed that cross-media campaigns enhance consumer attention and trust toward products or services, as well as improving brand visibility and forming positive attitudes. Additionally, an underlying need for information-seeking about innovative products activates this process, leading to increased attention to cross-media campaigns and greater information absorption, which can, in turn, foster positive attitudes toward innovative products.

Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

Products with high (vs. low) levels of innovativeness increase exposure to cross-media campaigns through a heightened need for information-seeking, leading to a more positive attitude toward the product.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Model

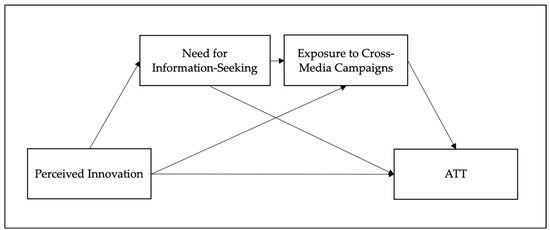

This study investigated the mediating effects of cross-media campaign perceptions and information needs on the influence of perceived innovativeness on customer responses, using data from previous studies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.2. Research Method

3.2.1. Respondent Characteristics and Research Design

The target market for this study was Cellapy, a cosmetics distribution brand that has launched an innovative product, the AGI Ampoule V Cushion. For this study, a survey was conducted among the AGI Ampoule V Cushion purchasers, which was released and sold by Cellapy. The product was released in South Korea, and was priced at approximately 70,000 KRW for the full package. It was primarily distributed through major online shopping malls (e.g., department store malls and H&B store malls), as well as offline stores (e.g., department stores and H&B stores) and home shopping channels across South Korea.

The product is an airless compact foundation with a vibrating function in the puff that applies the liquid foundation—a feature never released before in any product. When fingers are inserted into the puff to apply the liquid, it automatically generates micro-vibrations, allowing the foundation to adhere to and set on the skin without manual patting—a design innovation for the product.

As a color cosmetic product, its primary users are women, and all 157 participants in the survey were female consumers, with an average age of 40–63 years (SD = 7.96). The survey was designed to compare groups with high and low perceptions of the innovativeness of the AGI Ampoule V Cushion. The dependent variable was the product attitude toward the AGI Ampoule V Cushion, with the first mediator being the need for information-seeking about the product, and the second mediator being the frequency of exposure to cross-media campaigns related to the AGI Ampoule V Cushion.

3.2.2. Research Procedures

All respondents first measured the independent variable, namely, the perceived innovativeness of the product. They responded to four items (α = 0.95), developed by Sethi et al. [69] (pp. 73–85), on a 7-point semantic differential scale (e.g., 1 = Predictable vs. 7 = Novel, 1 = Commonplace vs. 7 = Original, 1 = Useful vs. 7 = Useless*, 1 = Appropriate vs. 7 = Inappropriate*). Subsequently, respondents answered questions about the mediators. For the first mediator, the need for information-seeking, they responded to six items (1 = Not at all vs. 7 = Very much so) on a 7-point Likert scale, developed by Lee et al. [70] to measure information-seeking motivation (e.g., When I saw the product, I tried to find more information about it; I want to get more information about the product; If the product is mentioned in conversations with others, I will pay attention to get more information; If I go to an H&B (Olive Young) or other cosmetic stores, I am willing to check information with the salesperson or try it myself). Subsequently, they answered questions regarding the second mediator, their exposure to cross-media campaigns. As Cellapy used six cross-media campaign materials during the product’s promotion period, respondents were shown all six cross-media campaigns and instructed to indicate whether they had been exposed to each campaign. The marketing content utilized in the cross-media campaign included PPL within TV shows, home shopping broadcasts, YouTube advertisements, influencer reviews on Instagram, promotional messages sent via mobile, and promotions in the official online and offline stores (see Table 2). These can be distinguished into two traditional media platforms (i.e., PPL broadcast on TV, home shopping), three digital media platforms (i.e., YouTube advertisements, promotional messages sent via mobile, and promotions in the official online and offline stores), and one emerging media platform (i.e., influencer reviews on Instagram). Furthermore, the frequency of exposure to the campaign was measured based on the consumers’ self-reported awareness of their exposure to the campaign. Accordingly, the survey was designed to ensure that participants could view the campaign content in its original form, as disseminated by the brand, during the survey process.

Table 2.

The marketing content utilized in the cross-media campaign.

Finally, they answered questions about the dependent variable, namely, product attitudes. First, they responded to three items (α = 0.98, 1 = Not at all vs. 7 = Very much so) used by Kim and Song [71] to measure attitude (e.g., I have a positive attitude toward this product; I am favorable toward this product; I like this product).

Additionally, to prevent response bias when constructing the items, the perceived innovativeness was measured using two reverse-coded items (indicated by an asterisk).

4. Results

4.1. Impact of Perceived Innovativeness on Product Attitude

The PROCESS macro by Hayes [72] was used to perform bootstrapping. The verification of mediation effects has long relied on the regression-based approach proposed by Baron and Kenny [73] and the Sobel Test developed by Sobel [74]. However, these methods have been consistently criticized for their limitations in assessing the statistical significance of mediation effects. For example, Baron and Kenny’s stepwise regression approach requires an indirect inference of mediation effects, rather than a direct estimation, while the Sobel Test assumes normality, making it less reliable when applied to small sample sizes.

To address these limitations, the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes [72] has gained widespread use in recent research. The PROCESS macro leverages the bootstrapping technique to directly estimate confidence intervals for mediation effects, and is recognized as a robust analytical tool capable of simultaneously testing both mediation and moderation effects. Unlike traditional methods, PROCESS requires only minimal input and eliminates the need for complex procedures, making it particularly useful for conducting multiple mediation and moderation analyses.

In this study, Model 6 of the PROCESS macro was applied, as it is well suited for analyzing multiple mediation effects involving two mediators. The selection of Model 6 was based on the study’s assumption of a sequential causal structure, where the first mediator influences the second mediator, which, in turn, affects the final dependent variable. This model allows for an analysis of the serial mediation effect, which explains how the first mediator transmits its impact on the dependent variable through the second mediator. Compared to single mediation models, Model 6 provides a more sophisticated explanation of the relationships among variables.

Furthermore, the application of bootstrapping is crucial in overcoming the limitations of Baron and Kenny’s approach and the Sobel Test. Bootstrapping generates confidence intervals by repeatedly resampling the data, eliminating the need for normality assumptions and ensuring more stable mediation effect verification, even with small sample sizes. This technique provides stronger statistical evidence regarding the significance of mediation effects.

Therefore, this study employed the PROCESS macro to enhance the accuracy and reliability of mediation analysis, addressing the shortcomings of traditional mediation effect testing methods and ensuring more robust analytical outcomes.

The independent variable was perceived innovativeness (High vs. Low), the dependent variable was attitude, and the mediators were the need for information-seeking and exposure to the cross-media campaign, with 157 responses analyzed. For bootstrapping, 10,000 resamples were drawn, and the results analyzed with a 95% confidence interval (CI) showed that perceived innovativeness positively impacted product attitude (β = 0.75, SE = 0.06, t = 11.47, p < 0.001; LLCI = 0.63, ULCI = 0.88), indicating that perceived innovativeness can lead consumers to form a positive product attitude(See Table 3).

Table 3.

The mediating effects of the need for information-seeking and the perception level of the cross-media campaign on the relationship between perceived innovativeness and product attitude.

4.2. Effect of Perceived Innovativeness on Information-Seeking and Cross-Media Campaign and Impact on Product Attitude

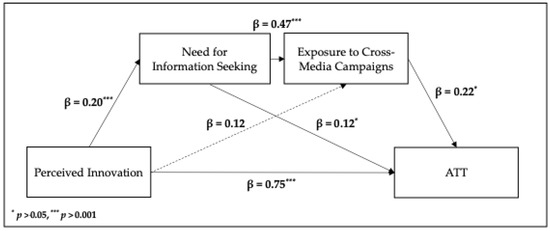

To analyze the effect of perceived innovativeness on information-seeking and the cross-media campaign, Hayes’ [72] PROCESS Macro Model No. 6 was used for bootstrapping, with perceived innovativeness as the independent variable, product attitude as the dependent variable, and the perception of information-seeking and cross-media campaign as the mediators. The results showed that perceived innovativeness positively influenced the need for information-seeking (β = 0.20, SE = 0.05, t = 3.73, p < 0.001; LLCI = 0.09, ULCI = 0.30), and the need for information-seeking significantly affected exposure to the cross-media campaign (β = 0.47, SE = 0.13, t = 3.57, p < 0.001; LLCI = 0.21, ULCI = 0.74). Additionally, the perception of the cross-media campaign positively impacted product attitude (β = 0.22, SE = 0.09, t = 2.33, p < 0.05; LLCI = 0.03, ULCI = 0.41; see Figure 2.). However, the impact of perceived innovativeness on the level of perception of the cross-media campaign and the effect of information-seeking on product attitude were not significant (p > 1).

Figure 2.

Mediating effects of need for information-seeking and exposure to cross-media campaign on impact of perceived innovation on ATT (Attitude).

Finally, in the formation of product attitude by perceived innovativeness, the dual mediating effect of the need for information-seeking and the perception of the cross-media campaign was significant (β = 0.01, SE = 0.00; BootLLCI = 0.00, BootULCI = 0.02; See Table 4). This finding demonstrates the importance of the process whereby “an increased need for information-seeking leads to the perception of cross-media campaign”, even though the pathways [Perceived Innovativeness—Need for Information-Seeking—Product Attitude] and [Perceived Innovativeness—Cross-media campaign—Product Attitude] were not individually significant.

Table 4.

Comparison results of indirect effect on DV (Dependent Variable).

4.3. Discussion

The results show that consumers form positive attitudes toward innovative products, and this is supported by the information-seeking process that leads to the perception of cross-media campaigns. In essence, consumers’ heightened information-seeking attention state leads them to focus more on a company’s cross-media campaign.

Innovative products arouse curiosity and high anxiety in consumers. This ambivalent emotion is caused by a lack of prior information regarding the product, and to alleviate it, the need to seek information is activated. As a result, consumers become more inclined to seek information and actively pay more attention to the product. Thus, consumers are set to voluntarily pay attention, being in a state of high alertness for the various kinds of content they are exposed to by the company. The knowledge gained through this process helps consumers to have reduced anxiety and perceive the benefits of the innovative product, thus allowing them to form a positive attitude.

Notably, in this process, the need for information-seeking and cross-media campaigns do not act individually as mediators. It is necessary for information-seeking to be activated to perceive more of the cross-media campaign, which leads to a positive attitude.

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study examines how consumers’ need for information-seeking drives their acceptance of interactive cross-media campaigns, and its influences on their attitudes toward innovative products. The theoretical implications of this research are as follows:

First, this study reveals that consumers do not accept interactive cross-media campaigns unless their need for information-seeking is activated. Thus, when consumers encounter an innovative product, they actively engage with strategically placed campaign content across various media platforms only if the product’s innovativeness intrinsically motivates them to seek more information. Unlike previous research, which primarily focused on individual characteristics, such as personal innovativeness, perceived risk, and novelty seeking, in innovation adoption [4,75,76], this study empirically demonstrates a behavior-based mechanism whereby psychological motivation, triggered by product innovativeness, facilitates interactions with brands. This need for exploration stimulates consumer–brand interaction, subsequently leading to positive attitudes.

Second, for this mechanism to function effectively, consumers must perceive the product itself as innovative. Cognitive comparisons between the uncertainty associated with innovativeness and the expected benefits trigger consumers’ need for information-seeking. Prior research indicates that innovative products typically pose psychological, functional, and economic risks to consumers [19], prompting them to engage in external information to mitigate these risks [24]. This study establishes a sequential mediating mechanism whereby risk-avoidance search behaviors lead to the voluntary acceptance of cross-media campaigns through information-seeking states, ultimately resulting in positive attitudes toward the product. This finding suggests that information-seeking is not merely a cognitive reaction, but a critical antecedent factor in attitude formation.

Third, this study aligns with Petty and Cacioppo’s [77] elaboration likelihood model, extending persuasion theories by demonstrating that information-seeking enables persuasion through the central route. Consumers with a high need for information-seeking process brand messages more deeply, making judgments based on logical reasoning, which positively impacts attitude persistence and resistance.

Fourth, this study theoretically examines how trust in UGC influences the effectiveness of cross-media campaigns. Prior studies indicate that consumers trust informal, non-commercial information sources, such as consumer reviews and influencer content, more than official brand-created content [78,79]. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced for innovative products characterized by high uncertainty and learning demands. The findings suggest that integrating UGC into cross-media campaigns strengthens the acceptance path driven by information-seeking needs. This provides a theoretical link explaining the mechanisms for enhancing credibility in interactive campaigns.

Finally, while previous studies on cross-media campaigns have emphasized repeated exposure and consistency across media platforms [63,80], this study empirically demonstrates how consumer acceptance is induced specifically within inherently interactive, engagement-based campaign structures. It provides theoretical grounds for redefining cross-media strategies not merely as simple media mixes, but as persuasion strategies grounded in psychological information-seeking states and interactive consumer–brand engagement, rather than one-directional content distribution.

5.2. Managerial Implications

This study has practical significance, as it considers external factors, such as cross-media campaigns that enhance firm–consumer relationships, and internal emotional and cognitive factors, particularly consumers’ need for information-seeking, within the positive adoption mechanism of innovative products. This approach empirically identifies key elements necessary for effective innovative product marketing campaigns, offering the following implications.

First, companies must stimulate consumers’ information-seeking needs when launching innovative products. These products inherently involve novelty and uncertainty, potentially creating psychological burdens (perceived risks) for consumers [17,19]. Consumers voluntarily engage in information-seeking behavior to reduce anxiety [24]. Clearly presenting a product’s utility and differentiation activates curiosity and information-seeking behavior. Thus, firms should move beyond merely explaining technical characteristics and employ narrative content, comparative explanations, and experience-centric messaging to stimulate exploration motivation.

Second, interactive cross-media strategies are more effective than mere repetitive exposure. Previous studies have suggested that repeated multimedia advertising exposure increases message acceptance and credibility [63,80]. However, this study demonstrates the superior effectiveness of interactive cross-media campaigns in shaping consumer attitudes. Consumers show deeper cognitive engagement when interacting directly or experiencing content [77]. Therefore, companies should design cross-platform interactions, such as PPL, live broadcasts, review reposting, and hashtag campaigns, ensuring consistent and connected messaging across platforms [80,81].

Third, leveraging credible source-based content, such as UGC, influencer posts, and consumer reviews, is essential. Consumers trust informal and non-commercial sources of information more than official brand-created content [78,79], particularly when products are perceived as risky or lack sufficient information. Therefore, companies should design content ecosystems that encourage diverse sources to circulate on consumer-driven channels, such as social media, YouTube, and online communities. This trust-based dissemination structure enhances brand credibility and reduces psychological barriers to accepting innovative products.

Fourth, establishing an omnichannel experiential environment to increase consumer involvement with innovative products is crucial. According to Zaichkowsky’s [82] involvement theory, higher consumer involvement enhances information engagement, thereby strengthening information-seeking and acceptance behaviors. Companies should implement omnichannel strategies that integrate online and offline channels, traditional media, and digital platforms. For instance, product exposure in physical stores, followed by repeated encounters through TV ads or social media, reduces consumers’ cognitive load, diminishes perceived risks, and fosters positive product attitudes.

Fifth, traditional media channels must be reconfigured interactively. Although traditional media, such as TV, home shopping, and PPL, remain effective for brand awareness, they should be adapted for social media, YouTube, and community-based sharing. The effectiveness of cross-media campaigns lies in leveraging interactive channel combinations, rather than single-channel exposure. Therefore, firms should enhance traditional channels’ functionality by incorporating interactive elements.

Overall, this research emphasizes the need for integrated consideration of psychological and strategic processes—from stimulating information-seeking motivations and designing interaction-based channels, to structuring information dissemination and forming consumer attitudes—when developing innovative product marketing strategies. This comprehensive approach extends beyond short-term advertising effects to encompass psychological acceptance pathways and long-term brand relationship formation, offering valuable practical insights.

5.3. Limitations and Future Direction of Research

This study provides several theoretical and practical contributions; however, it also has limitations, suggesting avenues for future research.

First, the study is limited by its sample composition and generalizability. It primarily examined middle-aged female consumers who had purchased innovative products. While this choice has practical significance and demonstrates real purchase behaviors, it limits the analysis of differences across consumer groups, such as those without purchasing experience, male consumers, or younger generations. Previous research indicates that demographic factors such as age, gender, innovativeness, and technological familiarity can influence acceptance behaviors toward innovative products [4,83]. Future studies should incorporate diverse demographic variables to comparatively analyze differences in attitudes and information-seeking behaviors related to innovative product acceptance.

Second, the categorization of campaign information sources was insufficiently addressed. This study measured consumer responses based on exposure to and awareness of cross-media campaigns without fully distinguishing the influence of different source types. Prior research has demonstrated that official brand-generated content and informal consumer- or influencer-created content (UGC, eWOM) have varying effects on consumer trust, message acceptance, and attitudes [78,79]. Future studies should analyze how information-seeking paths and attitude shifts vary across different information sources, such as brand-generated content, consumer reviews, and expert evaluations, to refine theoretical models.

Third, cultural and regional contexts were not considered. The study was conducted within the Korean consumer market, potentially restricting the findings to specific cultural and media contexts. Information-seeking behaviors and cross-media acceptance can vary significantly across different cultural contexts [42]. For example, individualistic cultures may prioritize autonomous information-seeking, whereas collectivistic cultures may depend on the others’ opinions or expert evaluations. Thus, future research should conduct comparative studies across diverse countries and cultural backgrounds to examine the global applicability and cultural moderating effects of cross-media campaigns.

Fourth, this study insufficiently addressed new media technologies, focusing on traditional digital channels (TV, YouTube, and social media), while current marketing environments rapidly integrate interactive technologies, such as augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), metaverse platforms, and AI recommendation algorithms [84]. These technologies provide deeper immersive experiences and personalized information delivery, substantially influencing consumer attitudes and information-seeking patterns. Consequently, future research should comprehensively examine exploration needs and brand acceptance mechanisms within next-generation media contexts, including AR/VR-based campaigns, chatbot interactions, and metaverse branding.

Addressing these limitations in future research could provide a more nuanced understanding of how the interaction between information-seeking behaviors and cross-media campaigns impacts innovative product acceptance across diverse consumer segments and media environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H. and S.L.; data curation, S.L.; formal analysis, H.H. and S.L.; methodology, H.H.; resources, S.L.; validation, S.L.; visualization, H.H.; writing—original draft, H.H. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, H.H. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Dankook University Institutional Review Board (DKU 2024-04-007-001). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines and regulations. The objectives and process of the research were explained to the participants, who were assured of the confidentiality of the information. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected and analyzed during the study are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, S.; Min, D. Effects of difference age and information searching level on attitudes toward innovative product. Asia Mark. J. 2023, 25, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy, T.J.; Trudel, R. Looks interesting, but what does it do? Evaluation of incongruent product form depends on positioning. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, C.P.; Lehmann, D.R.; Markman, A.B. Entrenched knowledge structures and consumer response to new products. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, K.C.; Bearden, W.O.; Madden, T.J. Consumer innovativeness and the adoption process. J. Consum. Psychol. 1995, 4, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Hoyer, W.D. The effect of novel attributes on product evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chu, W. The effects of innovation newness on consumers’ purchase intention: Focusing on the mediating role of familiarity and perceived risk and the moderating role of attributes vs. benefits appeal. Korean J. Mark. 2020, 35, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Ahn, K.H.; Ha, Y.W. Consumer Behavior; Bupmunsa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Newell, S.J. Innovativeness and price sensitivity: Managerial, theoretical and methodological issues. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 1997, 6, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, E.; Goldsmith, R.E. Some antecedents of price sensitivity. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Calantone, R.A. critical look at technological innovation typology and innovativeness terminology: A literature review. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2002, 19, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Jaworski, B.J.; MacInnis, D.J. Strategic brand concept-image management. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, E. Dyson Wants to Create a Hair Dryer Revolution. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/28/fashion/dyson-hair-dryer.html (accessed on 27 April 2016).

- Jung, C. Dyson Korea Opens ‘Dyson Beauty’ Pop-Up at Hyundai Department Store Pangyo. Monday News. Available online: https://www.wolyo.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=251428 (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Wang, C.L. Interactive marketing is the new normal. In The Palgrave Handbook of Interactive Marketing; Wang, C.L., Ed.; Springer-Nature International Publishing: ED.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzeland, 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Newswire. Global Hair Styling Tools Market to Worth $40.5 Billion by 2028: Hair Straightener Generates over 35% Revenue, Dyson, Revlon, and Philips Are Most Adored Brands. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/12/13/2572737/0/en/global-hair-styling-tools-market-to-worth-40-5-billion-by-2028-hair-straightener-generates-over-35-revenue-dyson-revlon-and-philips-are-most-adored-brands.html (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Xiao, L.; Wang, J.; Wei, X. Effects of relational embeddedness on users’ intention to participate in value co-creation of social e-commerce platforms. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeffler, S. Measuring preferences for really new products. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Chen, J.; Yang, X. The impact of advertising creativity on the hierarchy of effects. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W.; Harris, G. The importance of consumers perceived risk in retail strategy. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 821–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, K. Improvisation in product innovation: The contingent role of market information sources and memory types. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 1051–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, R.T.; Kosnik, T.J. High-tech marketing: Concepts, continuity, and change. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1989, 30, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior, 10th ed.; Thomson/South-Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, M.; Motherbaugh, D.L.; Best, R.J. Consumer Behavior: Building Marketing Strategy, 10th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, S.E.; Smith, S.M. External search effort: An investigation across several product categories. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.B.; Spreng, R.A. A proposed model of external consumer information search. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, N.; Ratchford, B.T. An empirical test of a model of external search for automobiles. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniuk, J.; Sharp, B.; Ehrenberg, A. Evidence concerning the importance of perceived brand differentiation. Asia Mark. J. 2007, 15, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, G.S.; Glazer, R.; Nakamoto, K. Meaningful brands from meaningless differentiation: The dependence on irrelevant attributes. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Swinyard, W.R. Attitude-behavior consistency: The impact of product trial versus advertising. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, M.M.; Chang, M.T.; Moon, K.L.; Liu, W.S. The brand loyalty of sportswear in Hong Kong. J. Text. Appar. Technol. Manag. 2017, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R.A. Consumer behavior as risk taking. In Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World, Proceedings of the 43rd Conference of the American Marketing Association, 15–17 June 1960; Hancock, R.S., Ed.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960; pp. 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund, L.E. Perceived innovation attributes as predictors of innovativeness. J. Consum. Res. 1974, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W.; Davies, F.; Moutinho, L.; Vassos, V. Using neural networks to understand service risk in the holiday product. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 46, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkhan, G.M.; Karande, K.W. Cultural and gender differences in risk-taking behavior among American and Spanish decision makers. J. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 131, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.; Sheth, J.N. Consumer resistance to innovations: The marketing problem and its solutions. J. Consum. Mark. 1989, 6, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Stelliner, W.H. Psychology of Innovation Resistance: The Less Developed Concept (LDC) in Diffusion Research; College of Commerce and Business Administration, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, S.; Eastlick, M.A.; Lotz, S.L.; Warrington, P. An online pre-purchase intentions model: The role of intention to search. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A.; Moreno-Gil, S. New trends in information search and their influence on destination loyalty: Digital destinations and relationship marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deighton, J.; Sorrell, M. The future of interactive marketing. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial—What is an interactive marketing perspective and what are emerging research areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. New frontiers and future directions in interactive marketing: Inaugural editorial. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Trends and prospects of AI, AR & VR in digital marketing. Int. J. New. Med. Stud. 2022, 9, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A. The power of play: Gamified advertising with AR/VR/AI and its impact on consumer engagement. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Toni, M.; Mattia, G. Tik Tok hashtag challenge: A new digital strategy for consumer brand engagement (CBE). In Proceedings of the EMAC Regional Conference, Warsaw, Poland, 22–24 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.A. Crossing the Chasm; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lynette Wang, V. Webrooming or showrooming? The moderating effect of product attributes. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Vertically versus horizontally differentiated information disclosure in travel live streams—The role of sensory imagery. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ma, Z. How do consumers choose offline shops on online platforms? An investigation of interactive consumer decision processing in diagnosis-and-cure markets. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.C.; Lee, C.T.; Lin, W.Y. Meme marketing on social media: The role of informational cues of brand memes in shaping consumers’ brand relationship. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 588–610. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Ma, B. Ride-sharing platforms: The effects of online social interactions on loyalty, mediated by perceived benefits. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.; Gensler, S.; Leeflang, P.S.H. Effects of traditional advertising and social messages on brand-building metrics and customer acquisition. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Online display advertising: Targeting and obtrusiveness. Mark. Sci. 2011, 30, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.A.; Raman, K. Understanding the impact of synergy in multimedia communications. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jayawardhena, C.; Osburg, V.S.; Yoganathan, V.; Cartwright, S. Social sharing of consumption emotion in electronic word of mouth (eWOM): A cross-media perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Ri, S.Y.; Egan, B.D.; Biocca, F.A. The cross-platform synergies of digital video advertising: Implications for cross-media campaigns in television, internet and mobile TV. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Thorson, E. Television and web advertising synergies. J. Advert. 2004, 33, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. Branding over internet and TV advertising. J. Promot. Manag. 2011, 17, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, I.B.; Graakjær, N.J. Cross-media communication in advertising: Exploring multimodal connections between television commercials and websites. Vis. Commun. 2013, 12, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinner, I.M.; van Heerde, H.J.; Neslin, S.A. Driving online and offline sales: The cross-channel effects of traditional, online display, and paid search advertising. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, P.J.; Dagger, T.S. Comparing the relative effectiveness of advertising channels: A case study of a multimedia blitz campaign. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorveld, H.; Smit, E.; Neijens, P. Cross-media advertising: Brand promotion in an age of media convergence. In Media and Convergence Management; Diehl, S., Karmasin, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, R.; Smith, D.C.; Park, C.W. Cross-functional product development teams, creativity, and the innovativeness of new consumer products. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Son, H.; Lee, D.; Kang, H. The influence of e-health literacy, subjective health status, and health information seeking behavior on the internet on health promoting behavior. J. Korean Soc. Wellness 2017, 14, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Song, S. The effect of geographic indication in advertising background pictures on product evaluation: The moderating role of familiarity. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 19, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Chung, N.; Lee, J. Empirical study about relationship between factors influencing Korean user’s intention to use the internet banking service. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2002, 12, 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, C.; Seong, S. Individual characteristics affecting user’s intention to use internet shopping mall. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2004, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 19, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.C.; Kim, Y. Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorveld, H.A.M.; Smit, E.G.; Neijens, P.C.; Bronner, A.E. Consumers’ cross-channel use in online and offline purchases: An analysis of cross-media and cross-channel behaviors between products. J. Advert. Res. 2016, 56, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorveld, H.; Neijens, P.; Smit, E. The interactive authority of brand web sites: A new tool provides new insights. J. Advert. Res. 2010, 50, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of consumer expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimo, S.; Bhandari, A. Algorithms, aesthetics and the changing nature of cultural consumption online. AoIR Sel. Pap. Internet Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).