Blockchain technology can enable non-profit organisations (NPOs) to create a large, diverse, and engaged community of donors and stakeholders in an autonomous and transparent manner. However, uncertainty remains regarding the appropriate use of blockchain technology by conservation NPOs for a variety of reasons (e.g., security, energy consumption, efficiency). We provide a primer of blockchain technology for NPOs that are unfamiliar with the diverse range of use-cases for blockchain technology, such as cryptocurrency. We discuss the myths regarding the energy costs for “mining” cryptocurrency and explore some of the technological advancements that will reduce the carbon footprint of utilising blockchain technology going forward. We also detail case studies of several conservation NPOs who have begun to adopt blockchain technology in their operations. We propose that the increasing use of blockchain technology could generate new revenue streams, enhance operational efficiency, and strengthen stakeholder trust to deliver impactful conservation outcomes and encourage NPOs and policymakers to begin pilot explorations of blockchain applications.

The resources available for the conversation of biodiversity are finite and limited. Efforts to save endangered species from extinction are particularly expensive. A study found that endangered species such as the Sumatran tiger, for example, require at least USD 50 million over a period of 25 years; this is compared to the USD 8 million that has currently been pledged [

1].

In addition, our search of a popular database on grants for environmental conservation, the Terra Viva Grants Directory, found that less than USD 1 million was available for tiger conservation from 25 out of 129 eligible organisations. Even for endangered species, it was difficult for Non-Profit Organisations (NPOs) to find sufficient funding for conservation activities prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic had a devastating impact on the global economy and financial markets [

2], and there was also likely a reduction in the funding available for conservation. With a global recession looming in the post-pandemic era, funding will become even more difficult to secure. As many NPOs compete in the same five major markets for public and institutional funding (i.e., US, UK, Canada, Germany, Australia), as well as second tier markets (in terms of volume of income, such as the Netherlands, Denmark, Switzerland, Italy and Japan), the endowment funds of major foundations in these countries are likely to have been negatively impacted by the economic crisis caused by COVID-19. It is also likely that funding from governments has decreased due to the need to service significant public debt after almost three years of mitigating the impact of the virus. Until other current geo-political concerns such as the Russo-Ukraine war and food security are adequately addressed, funding for conservation issues will continue to take a lower priority.

For NPOs, seeking institutional and corporate sponsorship has also affected their strategic flexibility, especially when funding opportunities in the form of grants are typically used for short-term programs or projects. For many NPOs, dependency on a few core institutional donors means that their continued existence is inextricably linked to externalities beyond their control, such as a change in government or corporate executive management. Hence, there is an urgent need for NPOs to create a large, well-funded set of donors and an engaged community of stakeholders. Given the Herculean task of securing long-term funding for NPOs, blockchain technology can be leveraged to create a larger, diverse, and well-funded donor base with an engaged community of stakeholders. As a globally distributed decentralized database that can record data including financial transactions, images, project data and voting records, blockchain is a technology-enabled service innovation that can assist in securing long-term financing for NPOs.

We describe the positive impact that blockchain technology could have on the generation of new revenue streams for NPOs, discuss myths regarding the high energy consumption of blockchain by comparing it to existing systems, and explore several case studies of social enterprises that are effectively using blockchain technology to fund and resource initiatives combating various societal challenges, including conservation.

1. Building Better with Blockchain

We begin by discussing how blockchain technology enables exchange that is truly global and accessible via cryptocurrencies. As such, by being able to accept cryptocurrencies as donations, NPOs can begin to access a global network of donors. We continue to explore how the use of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) can be used to evidence ownership of works of art that are gifted or exchanged to donors in gratitude for their donations or services to the NPO. These NFTs can then be traded and exchanged on the blockchain network, potentially developing into a profitable economy that deals with products and services from the NPO. Finally, the Decentralized Autonomous Organisation (DAO) can encourage a global network of volunteers and donors to participate more significantly in directing and guiding the activities of the NPO.

1.1. Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies are a digital medium of exchange where transactions are easily performed via a smartphone or other mobile computing device. Receiving donations via cryptocurrency could enable Non-Profit Organisations (NPOs) to reach wealthy and diverse benefactors worldwide. As of 2022, there are 19 cryptocurrency billionaires, and the cryptocurrency economy is worth approximately USD 2 trillion [

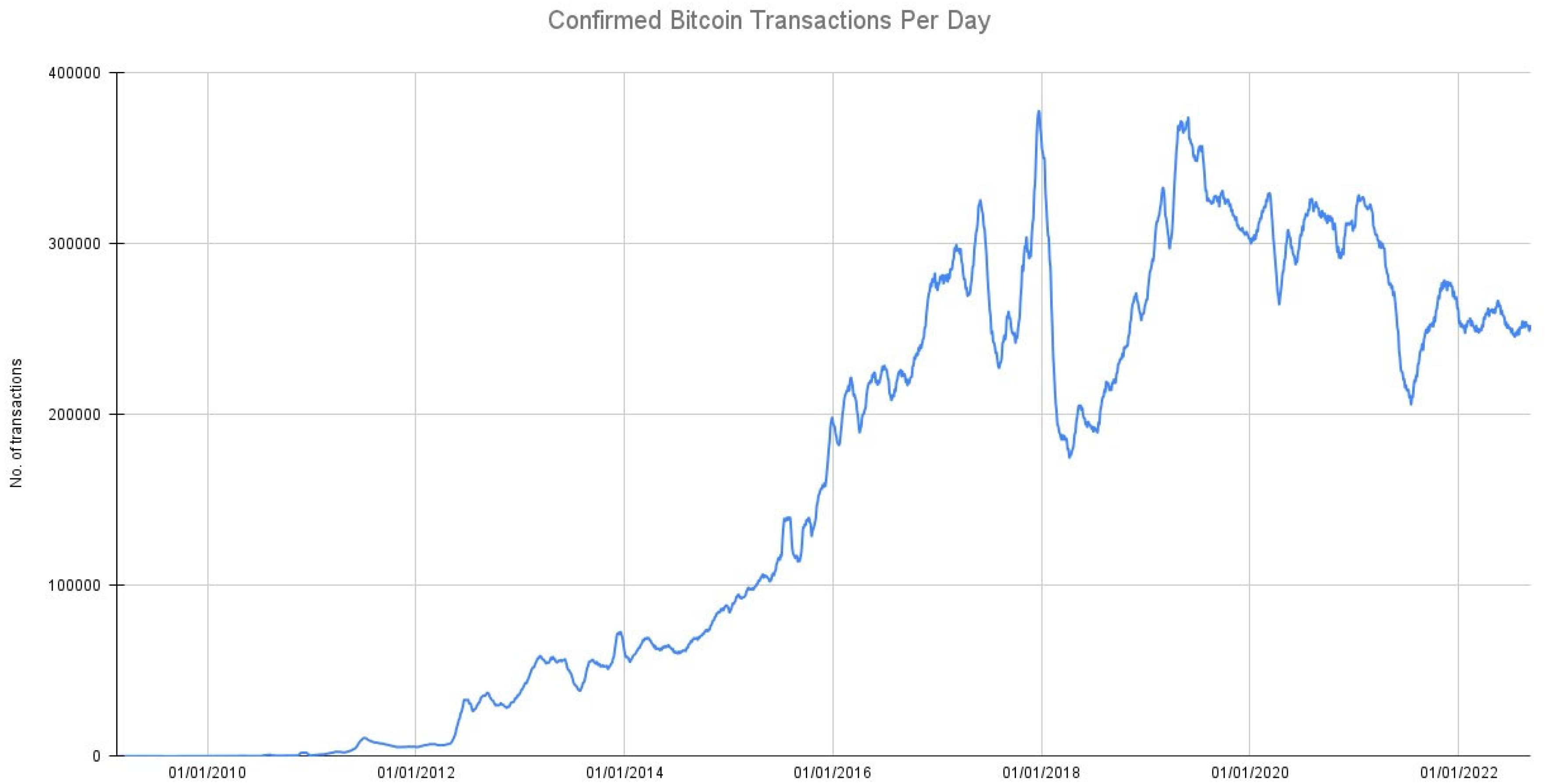

3]. Although there are many cryptocurrencies available, the daily number of Bitcoin transactions, as shown in

Figure 1, indicates the growth and acceptance of using cryptocurrency as a payment system (See the latest transaction data from Blockchain.com (

https://www.blockchain.com/charts/n-transactions (accessed on 30 June 2024))).

According to a joint Spectrem Group and CNBC survey, up to 83% of millennial millionaires own cryptocurrencies, with almost half planning to invest in more crypto assets in 2022. In contrast, only 4% of baby boomer millionaires own cryptocurrency and more than three-quarters of Gen X millionaires do not own any crypto assets. As a result, the early adopters of cryptocurrency are those of a younger generation who have observed and experienced rapid wealth creation and asset growth [

4]. This is an important observation, as millennials are deeply concerned with issues related to environmental sustainability and a strong desire to drive societal change [

5]. Therefore, wealthy millennials are more likely to donate to NPOs that are actively making progress in achieving goals that align with their personal moral values.

In June 2021, the UK Financial Conduct Authority found that 78% of adults are aware of cryptocurrencies, which is up from 73% in 2020. It is estimated that around 2.3 million adults now own crypto-assets, which is up from around 1.9 million in 2020. The number of UK consumers who believe that cryptocurrencies are a risky gamble is declining, and more consumers consider cryptocurrencies to be a complement to mainstream investments. Regardless of the volatility of cryptocurrency prices, respondents to a UK survey stated that they “know that they will make money at some point” with their cryptocurrencies [

6], thereby reflecting their confidence in the growth and value of crypto-assets. Therefore, there is greater acceptance and ownership of cryptocurrencies in the UK; therefore, it seems that the continued success of NPOs would benefit from their receipt of cryptocurrencies on their gifting platforms.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) acknowledges that “crypto-assets are potentially changing the international monetary and financial system in profound ways”. Evidently, it is acknowledged internationally that cryptocurrencies or digital assets are gaining mainstream acceptance as of 2022. The principal challenge for cryptocurrencies is no longer that they are an unknown and risky asset, but that a coordinated international regulatory response is required to protect vulnerable customers and ensure financial stability [

7]. The financial regulators of various governments are designing appropriate guidelines and frameworks for cryptocurrency use; therefore, NPOs can feel secure that in allowing cryptocurrency donations to be made, they remain on the right side of the law.

Interest in these cryptocurrencies may span a wide variety of societal challenges globally. Given the ease that one can transfer cryptocurrency from one wallet to another, one can easily imagine an example of a cryptocurrency millionaire in Finland directly supporting a small NPO based in Cairns, dedicated to protecting the Great Barrier Reef; this would prevent the donor having to go through the onerous effort of showing financial support via performing transfers through a financial intermediary or an umbrella organisation to distribute funds via a grant system. Cryptocurrency simply expedites the process of well-meaning, wealthy donors giving to NPOs that are in need of such financial support.

1.2. Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs)

The trade of NFTs, digital artwork that is stored on a blockchain, can be used to create a sustainable on-going income for NPOs. An NFT is best perceived as a digital version of “baseball trading cards”. Buyers of NFTs are often motivated by using NFTs as a symbol of their loyalty and support for a specific community or artist; this is conveyed by the rarity of a certain NFT and the possibility of the NFT being sold for a much higher price in the future. The value of the global NFT market is approximately USD 20 billion as of 2022. The size of the market is anticipated to continue growing at a compounded annual growth rate of 34%, reaching USD 212 billion in 2030 [

8].

Artists can donate their electronic works of art to a social enterprise that will “mint” (Create a proof-of-ownership record of a digital artwork on the blockchain) these art works to be sold to fund the social enterprises’ initiatives. An ongoing income can be generated, and all subsequent sales of the NFTs can be contributed back to the social enterprise’s cryptocurrency wallet. This is a device or program that stores a user’s cryptocurrency keys and allows you to access your cryptocurrency assets, similar to a bank account. Cryptocurrency wallets have a private and public key. A public key is the wallet’s address, which is similar to a bank account number. A private key is used to sign all outgoing financial transactions from the wallet and is similar to a bank account’s password. Due to the transparent nature of blockchain, the provenance, traceability, and accountability of these NFT sales are easily proven. Thus, blockchain addresses the operational challenges present in the physical art dealer market, where one has to prove the authenticity and provenance of each artwork that is sold, and where the original art dealer or artist is unable to profit from subsequent sales of the artworks in an efficient and transparent manner.

Not all donors are wealthy and are able to contribute to the NPOs directly via financial means. By using NFTs, well-meaning donors can contribute to the NPO by using their creative skill to create artworks that can be treated as an in-kind donation to the organisation. All the NPO has to do is focus on marketing the digital artworks and promoting their use to support different initiatives and projects, as all other administrative work regarding the management and selling of the artwork is taken care of by the blockchain.

1.3. Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs)

A DAO is a community-led entity with no central authority. It is an organization that is constructed by rules encoded in a computer program (i.e., smart contracts) in a transparent manner (i.e., auditable) and is a member-owned community without centralized leadership. Smart contracts lay foundational rules for the organisation, execute agreed-upon decisions, and present proposals and votes that can be publicly audited. A DAO’s treasury allocations, financial transaction records and program rules are all maintained on a blockchain, thus making it a transparent organisation.

Members of a DAO community can create project proposals to address social challenges within the remit of the social enterprise. Community members can then vote on each proposal. Proposals that achieve a predefined number of votes (i.e., more than 70% of community members voting positively) will then automatically receive the funding from the DAO community’s treasury to support it. While most social enterprises are guided by an executive committee and a board of directors, DAOs enable a new type of social enterprise to be communally governed. In this manner, it is possible to create a community of engaged stakeholders and donors who feel that their voices are heard, as their votes have a direct impact on the future of the organisation in a transparent manner.

2. The Energy Conundrum

A major concern in conservation circles is the high volume of energy consumed during cryptocurrency mining and the negative impact of this on the environment. The decentralised structure of cryptocurrency and blockchain means that they have a significant environmental footprint, as many computers race to solve a complex mathematical puzzle to verify blocks of transactions (i.e., mining) to be added to the blockchain. The fastest computer that certifies the transaction receives a small “mining reward” in the form of a Bitcoin honorarium, while all other machines that were unsuccessful in solving the problem will ignore the results from all calculations made after losing the race, thereby creating wasting energy and having a negative environmental impact.

NFTs that are minted using the Proof-of-Work (POW) operating method require high volumes of energy. A single NFT transaction on the Ethereum platform emits 150 kg of CO

2, equivalent to 332,056 Visa transactions [

9]. The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance estimated that Bitcoin’s power consumption rose from an annual rate of 6.6 terawatt-hours from 2017 to 138 terawatt-hours in early 2022. As for its carbon footprint, Digiconomist found that the total emissions produced by Bitcoin mining annually are 114 million tons of carbon dioxide, comparable to those of Belgium [

10]

2.1. Why Does Mining Consume So Much Energy?

Cryptocurrency mining is a colloquial term used for a process used in blockchain technology to validate and verify new blocks of data that are added to the existing blockchain. Popular blockchain technologies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum use POW in the validation and verification of new blocks. However, advancements in blockchain technology have led to alternative approaches that are not quite as energy intensive, and it is a common myth that POW requires copious amounts of energy in its implementation.

In the early days of Bitcoin, laptops and desktop computers could be used to mine cryptocurrency, and it is only in the last few years that Bitcoin mining is now performed in commercial warehouses with hundreds or thousands of specialised computing equipment [

11]. The reality is that POW only requires copious amounts of energy if the cryptocurrency becomes very popular due the large volume of transactions performed.

When the anonymous creator of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto, wrote his whitepaper, it was unclear how a digital currency would have economic value. In other words, if one creates the technological framework to create a digital currency, how do we encourage people to use it as a medium of exchange or how does it have value? Simply said, anyone can print out his or her own currency on a printer and start distributing it and encouraging its use as a form of payment, but how would you encourage its adoption and ascribe economic value to these printed pieces of paper? In fact, Bitcoin is not the first digital currency, but only the first successful one. Digital currencies predating Bitcoin include smartcards electronic cash, DigiCash, B-Money, Hashcash and BitGold [

12].

The genius in the creation of Bitcoin was the use of POW in the validation and verification of new blocks of transaction data added to the existing blockchain to embed economic value in the digital currency [

13]. POW requires the miners on the Bitcoin decentralised network to embark on a race to validate a block of data as fast as possible. This validation requires the computation to solve a complex mathematical puzzle. Solving this complex mathematical puzzle requires computing resources and electrical energy, and therefore miners commit economically valuable resources to creating new blocks in the blockchain. Miners who committed economic resources to participating in the race and won by solving the complex mathematical equation would be given a “mining reward”, which consisted of being given more Bitcoins. In short, the application of POW ensured that Bitcoin had an economic value that would, at minimum, be associated with the economic value of the resources required to perform the computations required to add a new block to the blockchain.

Satoshi Nakamoto hard-coded a requirement in Bitcoin’s software architecture that ensured that, on average, new blocks could be added to the Bitcoin blockchain every 10 min over a two-week period (i.e., blocktime). If new blocks were added to the blockchain faster (slower) than 10 min on average, the complexity of the mathematical puzzle would be increased (decreased). As Bitcoin became more popular and its price increased, more and more miners decided that it was profitable to mine Bitcoin. With more computers participating in the POW race, this led to blocks being added to the blockchain in less than 10 min, thus leading to an increase in the complexity of the mathematical puzzle, which led to greater energy consumption.

In short, the POW mining process consumes so much energy only because Bitcoin has become a globally popular digital currency. As the price of Bitcoin increases, it becomes economically valuable for individuals and companies to invest millions of dollars into specialised computing hardware to partake in the mining process. However, if the price of Bitcoin decreases and it becomes less popular, then there will be fewer miners and the time required to add a new block to the blockchain will decrease, leading to a reduction in the complexity of the mathematical puzzle to be solved. As can be seen from

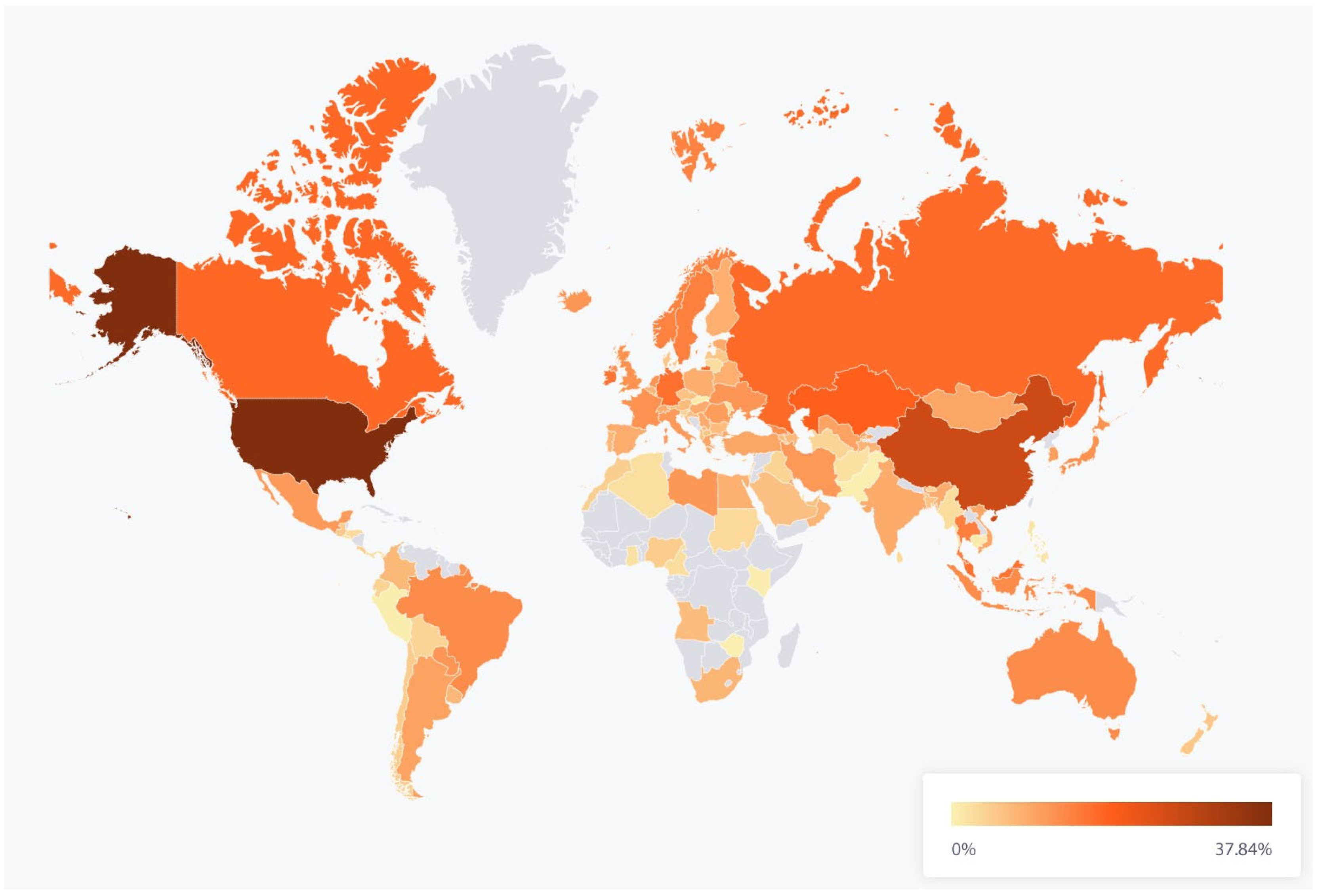

Figure 2, Bitcoin mining operations have a global presence, and the largest Bitcoin miners are currently in the US and China, as denoted by the monthly hashrate (The mining hash rate is indicative of the amount of hashing (computing) power in the network. The higher it is, the more secure the blockchain network is. The US is estimated to have the highest hash rate per month, at approximately 38%. A more detailed visualisation of the Bitcoin mining map can be accessed via the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (

https://ccaf.io/cbeci/mining map (accessed on 30 June 2024))).

2.2. Do Digital Currencies Consume More Economic Resources than Fiat Currencies?

Research by ARK Investment Management found that the Bitcoin ecosystem consumes less than 10% of the energy required by the traditional banking system. While it is true that the existing banking system serves far more people, cryptocurrency is still maturing; indeed, like any industry, the early infrastructure stage of any burgeoning technology is particularly intensive [

14].

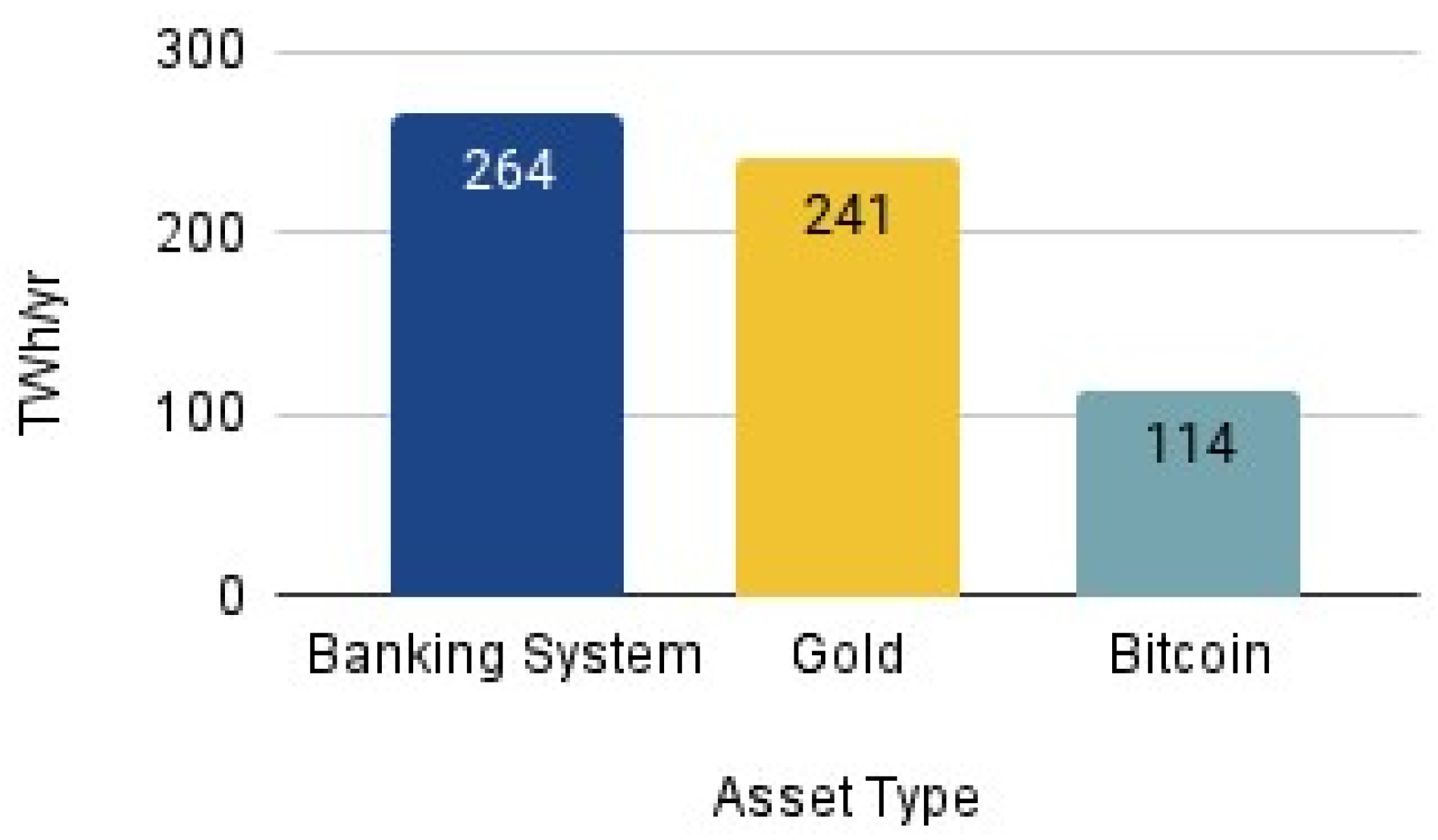

In

Figure 3, it is clear that Galaxy Digital, a digital asset and blockchain advisory firm, compares the Bitcoin network’s energy consumption with that of the banking system and the gold industry, since the largest cryptocurrency is often compared with the two. The report found that banking and gold consume around 263.72 terawatt-hour (TWh) per year and 240.61 TWh per year, respectively, while Bitcoin consumes much less energy, at 113.89 TWh per year [

15]. This includes the energy required for miner demand, miner power consumption, pool and node power consumption.

Tools such as the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index maintain a running estimate of Bitcoin’s energy consumption in real time. This development makes the energy consumption of Bitcoin mining more transparent, unlike the complex monitoring and assessment of energy usage in the gold and conventional financial system. The banking industry does not directly report electricity consumption data and the retail and commercial banking system requires multiple settlement layers; meanwhile, Bitcoin offers final settlement. In addition to Galaxy Digital’s calculations of the power used by banking data centres, bank branches, ATMs and card network data centres, it has been found that the use of physical paper and/or metals (e.g., for printing fiat currency, receipts, statements, legal documents and such), plastic for creating and renewing credit/debit cards, and fiat currencies in cycles of 2 or more years would consume much more energy, emit more CO

2 than cryptocurrencies, and certainly cause more damage to the environment. In order to calculate the energy consumption of the gold industry, Galaxy Digital Mining performed estimates of the industry’s total greenhouse gases emissions provided in the World’s Gold Council’s report entitled “Gold and climate change: Current and future impacts”. As estimated in the study, the gold industry utilizes roughly 126.72 TWh per year more than Bitcoin. Galaxy Digital also noted that “…estimates may exclude key sources of energy use and emissions that are second order effects of the gold industry like the energy and carbon intensity of the tires used in gold mines” [

16].

The significant electrical energy demands of gold mining are supplied by the grid, which comprises energy mostly generated by burning fossil fuel and coal. In 2020, the World Gold Council proposed that the emissions of the gold sector should be reduced by 80% by 2050 in order to align with the two degrees Celsius reduction temperature scenario outlined in the Paris Agreement. An analysis by Simone Brunozzi, Operating Partner at the technology investment firm Cota Capital, suggests that gold-mining is 50 times more expensive than mining bitcoins and running the bitcoin network. Producing the gold used in a wedding band alone generates 20 tons of waste. The DigitalMint Chief Operating Officer, Don Wyper, points out that the gold-mining industry—which produces between 2500 and 3000 tons of new gold every year—consumes 475 million gigajoules of electricity, which is equal to around 131.9 TWh. It is much more difficult to scrutinize the energy output of the banking system, which encompasses brick-and-mortar branches, printing facilities, computer servers, ATMs, and transportation, though one analysis has estimated that this figure is 140 TWh [

17].

2.3. How Cryptocurrency Mining Is Already Using Less Energy

Beyond this debate, miners are lowering their energy usage and carbon footprint while staying true to their promise of eliminating middlemen such as banks and governments.

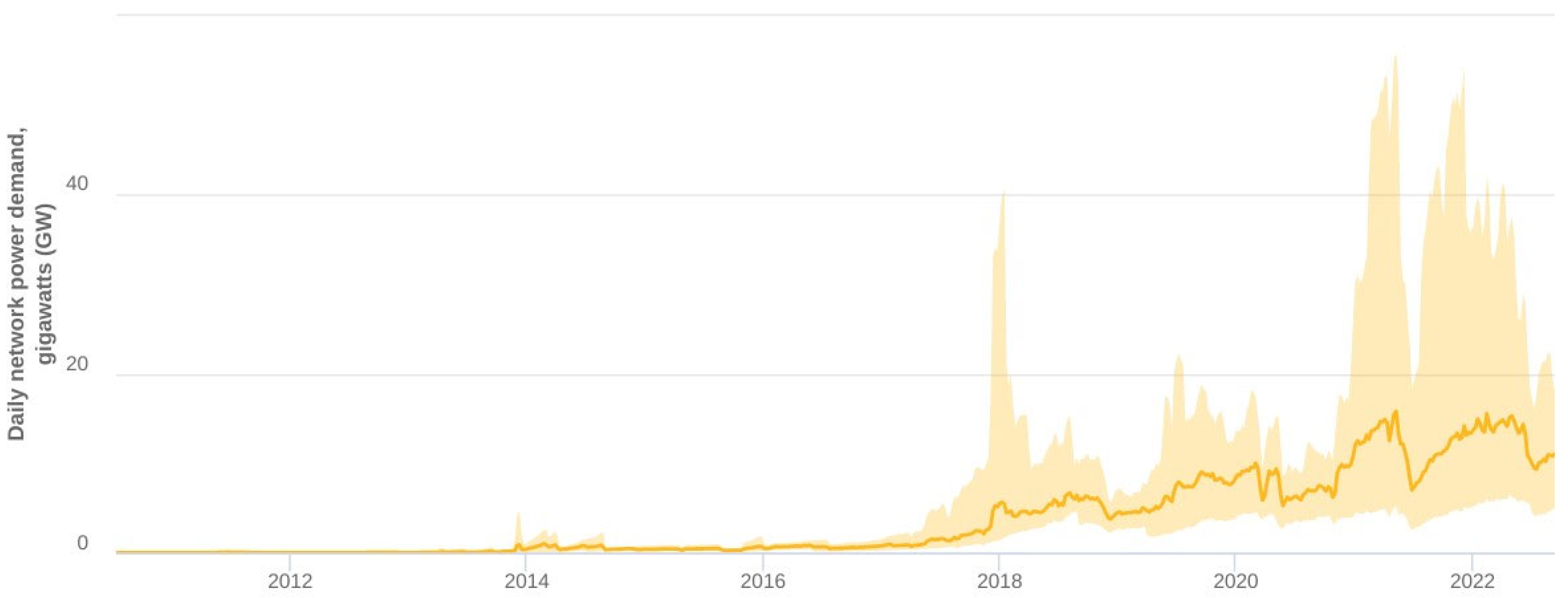

Figure 4 shows the estimated network power used by the Bitcoin network daily, as well as the theoretical upper and lower bounds (For the latest data, see the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (

https://ccaf.io/cbeci/index (accessed on 30 June 2024))). It is clear that the power demand of Bitcoin is not continuing to increase, and has most likely reached its peak. With several energy-saving initiatives being proposed for blockchain technology, it is highly likely that the power demand for cryptocurrencies will decrease going forward. We discuss technological innovations such as the growing popularity of the Proof-of-Stake system and global initiatives such as the Crypto Climate Accord, which show that reducing the energy consumed by blockchain technologies is crucial.

2.3.1. Proof of Stake System

Many blockchain frameworks are transitioning from a POW to Proof-of-Stake (POS) system that does not require the performance of energy-intensive calculations to solve complex puzzles to validate a transaction. Validators (Blockchain stakeholders whose role is to validate the authenticity of transactions and records on the blockchain) on a POS framework are obligated to stake—agree to not trade or sell—their cryptotokens associated with the specific blockchain system [

10]. Staking creates an economic incentive for validators to ensure that all transactions on a blockchain are genuine and secure, as if any false or corrupt data appears on the blockchain, the cryptotokens that have been staked become worthless [

18]. Validators stake an amount of cryptotokens in a lottery for the opportunity to verify transactions. The larger the number of cryptotokens being staked, the higher your odds of being selected to validate and verify transactions. The POS method removes the competitive computational element of POW, thereby saving energy.

Ethereum, a popular blockchain system underpinning the Ether cryptotoken and most NFTs, is in the process of being converted from POW to POS. It is anticipated that this will dramatically reduce the energy consumption of Ethereum-based cryptos and blockchains by an estimated 99.5% [

10]. Other methods of validation are also being developed, such as proof of history, proof of elapsed time, proof of burn, and proof of capacity.

2.3.2. The Crypto Climate Accord

Drawing inspiration from the Paris Climate Agreement, many organisations in the blockchain industry have launched initiatives such as the Crypto Climate Accord to advocate for and commit to reducing the blockchain industry’s carbon footprint. Amongst its goals is to promote the use of renewable energy sources such as solar power, wind, and hydro-generated electricity to enhance the efficiency and viability of mining. This would make blockchain’s energy mix less reliant on carbon-based energy. It is currently estimated that POW mining uses 39% renewable energy, but this can be scaled up further [

19].

In the US, publicly traded blockchain mining firms are increasingly focusing on developing in-house Environment, Social, Governance (ESG) initiatives to increase their market share. Cryptocurrency mining firms can choose to purchase carbon credits to help offset the amount of emissions generated or switch to a greener energy source. This emulates the Clean Air Act, which has led many firms to achieve net-zero emissions within a specified time frame [

18].

Other proposed solutions are rerouting profits from selling digital art via NFTs towards investments in renewable energy. Users of blockchain networks can pay an additional fee for transactions on blockchain networks that act as a carbon offset. This is similar to the option offered to frequent flyer travellers, which allows them to offset the flight’s carbon emissions when purchasing airplane tickets.

3. Case Studies

Many environmental conservation organisations are realising that cryptocurrency can complement and even enhance fundraising efforts, as these digital currencies can be exchanged globally from any investor’s armchair. Some Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) who are active in the blockchain sphere include Orang Utan Outreach, Oceanic Society, Wildlife Conservation Network, Wildlife Conservation Society, Save Planet Earth.io, Aquari.io, and Pangea Ocean Cleanup.com. Ref. [

20] explore the benefits of using blockchain technology to promote the Paris Agreement carbon market mechanism and discuss the requirements of an appropriate blockchain platform.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature [

21], a global non-profit, has teamed up with Gaiachain to develop Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) at a large scale via FLRchain, a blockchain-based application. The goal of the FLR chain is to achieve forest landscape restoration on a large scale. The FLR chain allows investors to efficiently send money to landscape committees that then distribute the funding to farmers in exchange for FLR, with their efforts being verified by facilitators. This FLR payment method is based on the Algorand protocol blockchain and facilitates incentive payments between investors (e.g., donors or companies), facilitators (e.g., NGOs) and landscape restorers (e.g., farmers and producers). Investors can track payments to communal basket funds and individual producers or producer organisations in real time [

21].

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), a global non-profit renowned for its work fighting wildlife crime, has joined hands with BitPay to allow donors to make donations in Bitcoin, Ether, and other popular alt coins. Crypto donations to WCS are converted to US Dollars to fund their work in saving endangered wildlife and their habitats. In their model, donors fill in a form, then click on the Bitpay button, which asks donors to connect to a wallet of their choice. Giving is performed in the cryptocurrency of their choice. Their crypto wallet provider will record a transfer via finance@bitpay.com. WCS will then send donors a gift acknowledgement.

Wildcards (

https://wildcards.world/ (accessed on 30 June 2024)) has developed a unique funding model whereby NFT investors pick from a collection of wildcards to support conservation efforts. Investors who purchase an animal NFT will be that animal’s guardian and contribute to the animal’s conservation through donations until someone else outbids them for the card. The beneficiaries of Wildcards include BioS, which conserves Peru’s Pampas cats; the Tsavo Trust, which protects Kenya’s super-tuskers, elephants whose tusks grow so long they touch the ground; and MareCet, which strives to protect marine mammals and their habitats in Malaysia.

Wildcry (

https://www.aspinallfoundation.org/the-aspinall-foundation/wildcry/ (accessed on 30 June 2024)) has a funding model for conservation projects that is based upon the donation of digital artworks focused on landscapes, wildlife and artworks, with conservation-related imagery. For example, clients purchasing NFTs under the “Forest Tree” collection will support a forest conservation programme. The artists receive up to 70% of the money made from the sale of artworks, with 30% going back to the Wildcry conservation network. Such an arrangement fosters a symbiotic relationship between the artist and the Wildcry network, whereby the growing popularity of the conservation programs and artwork will lead to greater sales and turnover for the underlying NFT artworks and greater revenue for both the artists and the conservation programme.

Members of Wildcry who are particularly interested in a cause can purchase an NFT that is attached to a project such as deforestation, dwindling tiger or elephant populations, or turtles and marine ecosystems; they then invest in each project that they purchase. Owning an NFT will allow them access to a community related to their investment, like-minded individuals or groups that want to achieve a goal set by the community and project; this in itself builds momentum and motivation, enabling a project or cause to achieve success. Furthermore, individual projects can host giveaways, wallet drops, gamification for conservation, events, networking and community voting procedures, and may serve on a dual market system that is accessible to owners of NFTs.

Wildcry also implements a DAO whereby conservation projects are submitted by different conservation teams and a transparent voting system is used to allocate funding from the Wildcry treasury to these specific conservation projects. Purchases of photographs or artwork on Wildcry are determined by community voting. This establishes a firm schedule of sales and which organisation will benefit from the funds raised, when and how often this happens, and the value of each sale. Conservation NGOs or beneficiaries of the fund partnered with Wildcry will put this to good use by working with local communities, enhancing knowledge of conservation science and implementing long-term solutions to environmental challenges. Investors will have peace of mind knowing that the funds raised will go where they are promised.

The DAO voting system is reliant upon the WildCry (WLDC) token, whereby the more tokens you have, the more votes you have. Such a market-based system of voting will engender greater engagement, as those who are highly supportive of the WildCry initiative will naturally be stronger financial supporters of the Wildcry team. By implementing a DAO within Wildcry, the Wildcry community could become an independent community of blockchain and conservation enthusiasts, which will attract digital artists to donate their artworks, conservationists who seek funding for their independent initiatives, and donors with an interest in funding conservation projects in a transparent manner.

Other Blockchain-Based Conservation Organisations

We provide a brief list of several other conservation organisations that recognise the potential of using blockchain technology to increase donor and stakeholder reach, capitalize on sustainable entrepreneurship opportunities, and build more efficient and transparent organisations with the DAO framework.

Saveplanetearth.io (SPE) uses strategic partnerships, academic backing, and a strong budding cryptocurrency community to significantly change the Earth’s landscape through carbon sequestration, in coordination with international aid organizations and the public alike. SPE’s overall goals include developing an enhanced green space (tree cover), improving marine management, lobbying for more meaningful legal controls, and supporting the real costs of climate change.

Aquari.io is an environmental conservation organization powered by cryptocurrency that aims to restore Earth’s bodies of water to a healthy state for all living creatures on Earth. Each transaction is taxed 10% of its total value. The tax is divided: 4% is burned to provide liquidity, 3% is redistributed amongst all Aquari holders, and 3% is sent to a donation wallet to finance the Aquari Non-Profit Organization’s efforts.

Pangea (Pangeaoceancleanup.com) is a Singaporean company that has been operating since 2019. Its mission is to clean the ocean and inspire an ecological movement. To date, Pangea has raised more than USD 500,000 and held 40 beach cleanups in 10 countries. POC is a sustainable circular economy solution that could combat ocean pollution. It stops and recycles trash using river barriers that are tracked and verified through the blockchain. The barriers generate revenue through the creation and sale of plastic offset credits; meanwhile, the trash is made into Pangea’s line of recycled products and sold to manufacturers.

Anji.eco will be a place for investors who prefer to invest in charity-focused tokens. Future token creators will be able to create ANJI-20 tokens with ease, and investors will have peace of mind knowing that the charity funds raised will go where they are promised. SafePanda will be the trading pair for this Decentralised Exchange (DEX), and the first token to be introduced will be Bamboo. Anji is currently in development, with more details to come.

Aquagoat.finance is a next-generation ecological Decentralised Finance (DeFi) token with a purpose: saving our oceans. A portion of every transaction is sent to the AquaGoat “Ocean Blue Fund”, which is used to fund ocean cleaning and marine conservation initiatives. The token currently works with seven NGOs and is growing.

World of Waves is a crypto token built on the Binance Smart Chain. Like most tokens, $WOW has a built-in tax that is initiated with every transaction; this transactional tax is 11% and is broken down in the following way: 3.3% is redistributed back to all holders, 3.3% is sent to the liquidity pool, and 4.4% is sent to the $WOW charity wallet. As the charity wallet grows, funds are extracted monthly for donations that are voted on by the community and are geared towards ocean conservation and the preservation of aquatic wildlife. The $WOW team aims to be the developer team that is most transparent with its investors.

4. Conclusions

Facing the critical need for diverse and sustainable funding mechanisms for biodiversity conservation, particularly in the wake of the pandemic’s economic impacts, blockchain technology presents a compelling and timely opportunity for non-profit organisations (NPOs). Leveraging innovative applications such as cryptocurrencies, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), and Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs), blockchain offers novel pathways to generate revenue, increase operational efficiency, and build trust with a wider, more engaged community of stakeholders. While concerns regarding energy consumption have been raised, technological advancements, including the widespread transition to Proof-of-Stake systems and initiatives like the Crypto Climate Accord, are significantly reducing the environmental footprint of many blockchain applications, making these concerns increasingly addressable. Given this potential for transparency and enhanced engagement, and building on successful pilot efforts already underway by some conservation groups, it is imperative for conservation NPOs to proactively begin practical exploration through pilot projects. This essential step towards harnessing blockchain’s benefits should be supported by policymakers establishing regulatory frameworks that are both encouraging and facilitative of responsible adoption.